Edward Winter

See C.N. 7383 below.

An article by G.H. Diggle on pages 277-281 of the July 1934 BCM marked the centenary of the La Bourdonnais v McDonnell matches; it was reprinted in part on pages 69-75 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1951). In Newsflash in June and July 1984 Diggle wrote a further feature on the matches. Given on pages 3-6 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987), the two parts are reproduced below.

June 1984:

‘This month marks the 150th Anniversary of a famous match series which (wrote R.N. Coles) “still bears comparison with that of any later age”, when, in the words of George Walker, “La Bourdonnais came to London with the roses of June” and encountered the great Irishman Alexander McDonnell in 85 games lasting all through the Summer (La B. 46, McD. 26, Drawn 13). These games were unevenly split between six matches, but the conditions of play were very loose – there were no seconds, there was no time-limit, the stakes were “very small” and, amazing to relate, the whole splendid series would never have been preserved for us but for one man. William Greenwood Walker, the aged Secretary of the Westminster Chess Club, was “little of a chessplayer” but a fanatical “fan” of McDonnell’s, and throughout the whole 85 games the old gentleman sat beside the English Champion “with spectacles on nose” eagerly taking down the moves and “scarce daring to breathe lest the conceptions of his hero should miscarry”. George Walker (not a relative) wrote of him: “He died full of years – we would well have spared a better – aye – many a better man.”

The Champions played every day of the week except Sunday, usually from noon till 6 or 7 p.m., but never more than one game at a sitting. Many games were adjourned till next day. Indeed, McDonnell was (except Williams) the slowest player this country ever produced. “I have seen him an hour and a half”, writes George Walker, “and even more, over a single move, and I once timed La Bourdonnais 55 minutes”. But in those spacious days this seems to have impressed rather than repelled the spectators, who (even if themselves not sufficiently advanced to appreciate the quality of the play) felt that “this was indeed chess”, far superior to such weasel encounters of the past as that in 1821 between Lewis and Deschapelles, who played their three games match “before dinner”.

The circumstances, as distinct from the conditions, under which the matches were played strongly favoured McDonnell. He was a very comfortably off bachelor who held the post of Secretary of the West India Committee of Merchants with a salary of £1,200 a year. As his duties were to watch the progress of Bills affecting the West Indies, he had work to do only when the Houses of Parliament were sitting (in fact, the Palace of Westminster was burnt down in the famous 1834 fire, which must have occurred during the match). La Bourdonnais, though of a noble family and heir to an old estate – in the earlier years of his marriage he possessed “un château, cinq domestiques, et deux équipages” – impetuously lost all his money in a building speculation and came down to £60 a year as Secretary of the Paris Chess Club and what he could make as a professional at the Café de la Régence. During the McDonnell matches his boisterous resilience was such that he would follow up a seven-hour struggle by playing for half-a-crown a game against all-comers till long after midnight.

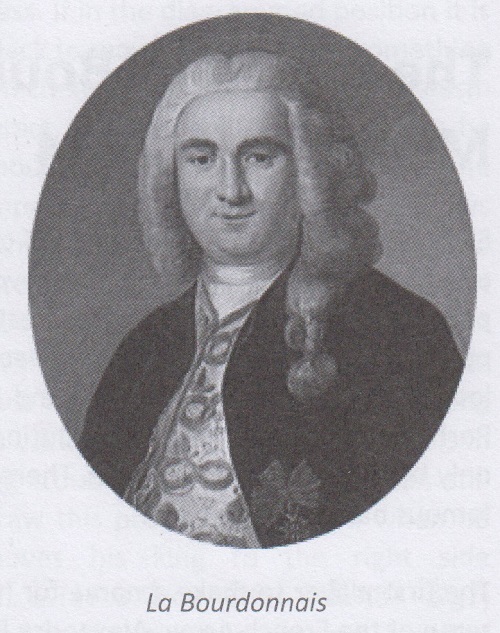

McDonnell only lived a year after the great encounter, being stricken with Bright’s Disease at the age of 37. Later, in Le Palamède, La Bourdonnais wrote handsomely about him as the greatest player he had ever encountered (he did add, as a rather hurried afterthought, except M. Deschapelles, but this was a sop to his touchy old predecessor). No portrait of McDonnell has survived and the only one of La Bourdonnais (the frontispiece of Le Palamède, 1842) was described by Staunton (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volume two, page 159) as a “lithographic enormity”, though Staunton never actually saw either of the two masters.

As many varying opinions on the actual games have been expressed by experts, the BM (having just played through the whole series) hopes next month to report on his “findings”, which will no doubt stagger the Chess World and set everybody right.’

July 1984:

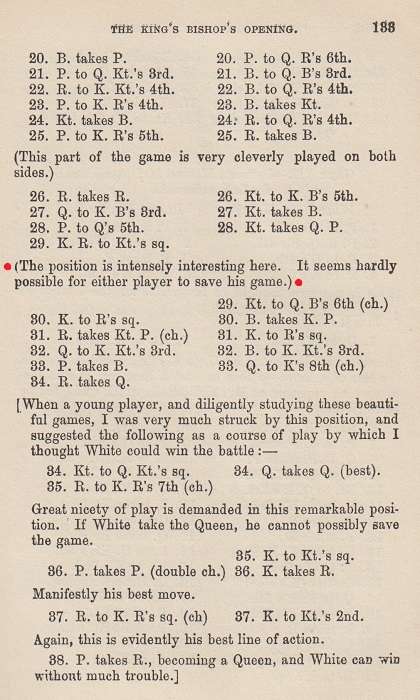

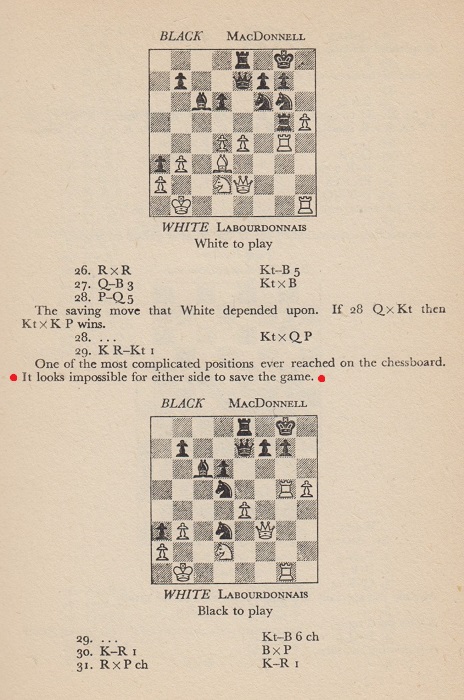

‘To play through the 85 La Bourdonnais-McDonnell games, covering just over 3,500 moves aside, is rather like crossing the Atlantic in stormy weather, or at best choppy seas with deceitful calms. And to annotate them, even for an expert, must be a nightmare. Staunton himself, who did so (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volumes 1-3), really sums up the series in a famous note to Game 21: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.” Such were the complications he encountered that even he, never afraid of deep analysis, was sometimes driven to dodge the “heavy seas” and pick on shallower water where he could say something when there was nothing to be said: “The youngest player will perceive that White would have lost his queen had he imprudently captured the queen’s pawn.”

Both masters were of the same temperament, daring in attack and ingenious in defence. McDonnell in particular could always start something out of nothing. And throughout the six matches both completely ignored the state of the score, playing each game solely to win, and even (there being no time-limit) to win like human computers by seeing every variation. Though in this they never succeeded, in some games, notably the 47th, they came magnificently close to it. During this great struggle, in which the middle-game “revels” begin as early as the ninth move with every piece still on the board, neither player misses anything throughout a colossal mêlée lasting up to the 20th, when the position seems to collapse under its own weight and the two queens and two minor pieces aside perish in the debris. But the survivors on both sides are on their feet again in an instant, and a new phase begins – an enthralling race between two rook-supported clusters of passed pawns, ending in a hair-raising French victory in 53 moves. While croaking “moderns” will condemn this game (“Wot? No logical Theme?” or “Wot? No planned connection between the first half and the second?”), the BM can only growl defiantly, “Let them croak!”

Of the 85 games, the following have been agreed by generations of critics to be “the greats”: games 17, 47, 62 and 78 won by the Frenchman and 5, 21, 30, 50 and 54 won by McDonnell. To these the BM would add 15 and 40 (La B.) and 85 (McD.). The “Immortal 50th” has always been awarded “the Oscar”, but this game was “all McDonnell”, and there are other good candidates in which both masters were on the top of their form. In some one feels the wrong man won; though McDonnell lost 40 (a King’s Gambit in which he gave up two pieces in the first nine moves), he actually harried La Bourdonnais with his inferior force for 22 more moves before he was finally shaken off by the Frenchman’s knife-edge accuracy.

But only 12 “Royal Battles” have been mentioned. What of the 73 “plebeians” remaining? Many are curate’s eggs, excellent up to more than half-way through, then addled by blunders, McDonnell being the worse offender. But others are rated by “H.G.” in A History of Chess as thoroughly bad eggs throughout, and this is difficult to dispute. In his disastrous first match McDonnell, playing White against the Sicilian, repeatedly makes such a crude hash of the opening that his king (with both his rooks and bishops still unmoved) is forced to make a fatuous excursion via KB2 to KR3, where he is speedily run over like a stray cow on a railway line. As for La Bourdonnais, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that before, instead of after, he played the 58th and 83rd games, he had, as was his nightly custom, “sent pint after pint of Burton Ale Beer into the hold”.

The whole series is given in Walker’s “Thousand Games” – the 47th game described above also appears in Staunton’s Laws and Practice of Chess, Greenwell’s Chess Exemplified, R.N. Coles’ Battles-Royal of the Chessboard, and the BCM, July 1934 with notes by Sir Stuart Milner-Barry.’

(7369)

See also De la Bourdonnais versus McDonnell, 1834 by Cary Utterberg (Jefferson, 2005) and our feature article Alexander McDonnell.

There are innumerable books and disks which assert that Labourdonnais lost the following game to McDonnell in their 1834 match: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Nc3 gxf3 6 O-O c6 7 Qxf3 Qf6 8 e5 Qxe5 9 Bxf7+ Kxf7 10 d4 Qxd4+ 11 Be3 Qg7 12 Bxf4 Nf6 13 Ne4 Be7 14 Bg5 Rg8 15 Qh5+ Qg6 16 Nd6+ Ke6 17 Rae1+ Kxd6 18 Bf4 mate.

An ‘historical correction’ from Harry Ruckert of New York was published in the readers’ letters section of the December 1955 Chess Review (page 353):

‘Have you ever wondered why a great master like Labourdonnais let himself be mated in 18 moves in that Muzio Gambit you see so often in chess books and magazines? (e.g. 500 Master Games of Chess, by Tartakower and du Mont, game 220, page 284).

The answer is: he didn’t! L. Elliott Fletcher, author of Gambits Accepted, writes that McDonnell’s opponent in this game was really a semi-anonymous player, given as “R*ll***n”, and not Labourdonnais. Mr Fletcher made this discovery in the British Museum in the course of researches for his forthcoming The Immortal Eighty-five, making available again all the games of these great matches in the 1830s.

It seems there were three authentic Muzios (one the famous 54th game) and, in all, McDonnell played his own variation, still called the “McDonnell Attack”: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Nc3 gxf3 6 Qxf3. But Mr Fletcher thinks he would have played the “almost reckless” 6 O-O only against a weaker player – and at odds of queen rook.

So, if you have a printed score of this game, do the ghost of Labourdonnais a favor and scratch out his name, substituting: “R*ll***n”.’

It appears that the ‘forthcoming’ work The Immortal Eighty-five never came forth, although we possess a copy of the typescript. In any case, the matter of the Muzio Gambit brevity had already been covered by G.H. Diggle five years previously, in a letter published on page 291 of the September 1950 BCM:

‘In Mr Reinfeld’s beautiful Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces there are two brilliant Muzios given as match games won by McDonnell against Labourdonnais. The first is certainly the 54th game of the immortal series; but in the second McDonnell’s real opponent (to whom he gave the odds of queen’s rook) was “Mr R*ll****n” (probably Rolliston), one of the amiable asterisk-ridden amateurs of the 1830s (see George Walker’s Chess Studies, Game No. 202, and Greenwood Walker’s Selection of Games Played by McDonnell, Book I, Game No. 4, also the Appendix, where “J. Rolliston, Esq.” appears on Greenwood’s list of subscribers).

Mr Reinfeld is not to blame – the fault lies on this side of the Atlantic, where over 60 years ago an English author (no longer here to defend his strange conduct) reprinted the game, cast poor Mr Rolliston overboard, substituted Labourdonnais instead, and (most monstrous of all) actually gave McDonnell back his queen’s rook – as though the great master really needed it! The game has passed for a “Labourdonnnais-McDonnell” ever since.’

(2600)

Discussing an 18-move Muzio Gambit game which has incorrectly been labelled a loss by Labourdonnais, C.N. 2600 (see above) quoted from page 291 of the September 1950 BCM G.H. Diggle’s attribution of the mistake to “an English author (no longer here to defend his strange conduct)”. We can add now that on page 139 of the May 1967 BCM Diggle identified him:

‘The “villain” who, as far as I know, first printed the game as a “Labourdonnais v MacDonnell [sic]” was W.J. Greenwell (Chess Exemplified, Leeds, 1890). But it is possible that he may have copied the game in good faith from some earlier writer.’

(2887)

C.N. 3397 gave a picture of Labourdonnais by Sam Loyd (Scientific American Supplement, 6 April 1878, page 1884) and we commented:

‘This is based on the well-known (and only known) picture of the Frenchman, and Loyd wrote, “our portrait is taken from an oil painting made in London a short time before his death”.

This brings to mind Staunton’s remark on page 159 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1842 when welcoming the French magazine Le Palamède:

“We must, however, protest against the insertion of such lugubrious twaddle as ‘The last moments of Labourdonnais’, from – Bell’s Life in London! and the lithographic enormity, from the same classic source we presume, presented as the portrait of that distinguished chessplayer.”’

Loyd’s picture (above, on the right) was also given on pages 286-287 of Chess Facts and Fables, but what is the exact connection between the ‘oil painting’ and the ‘lithographic enormity’? We also wonder how they relate to the slightly different picture of Labourdonnais in Loyd’s ‘photographic chessboard’ (C.N. 3590). That illustration sometimes appeared, again in minuscule form, in headings in the Chess Amateur (e.g. July 1913 issue, page 290):

(5128)

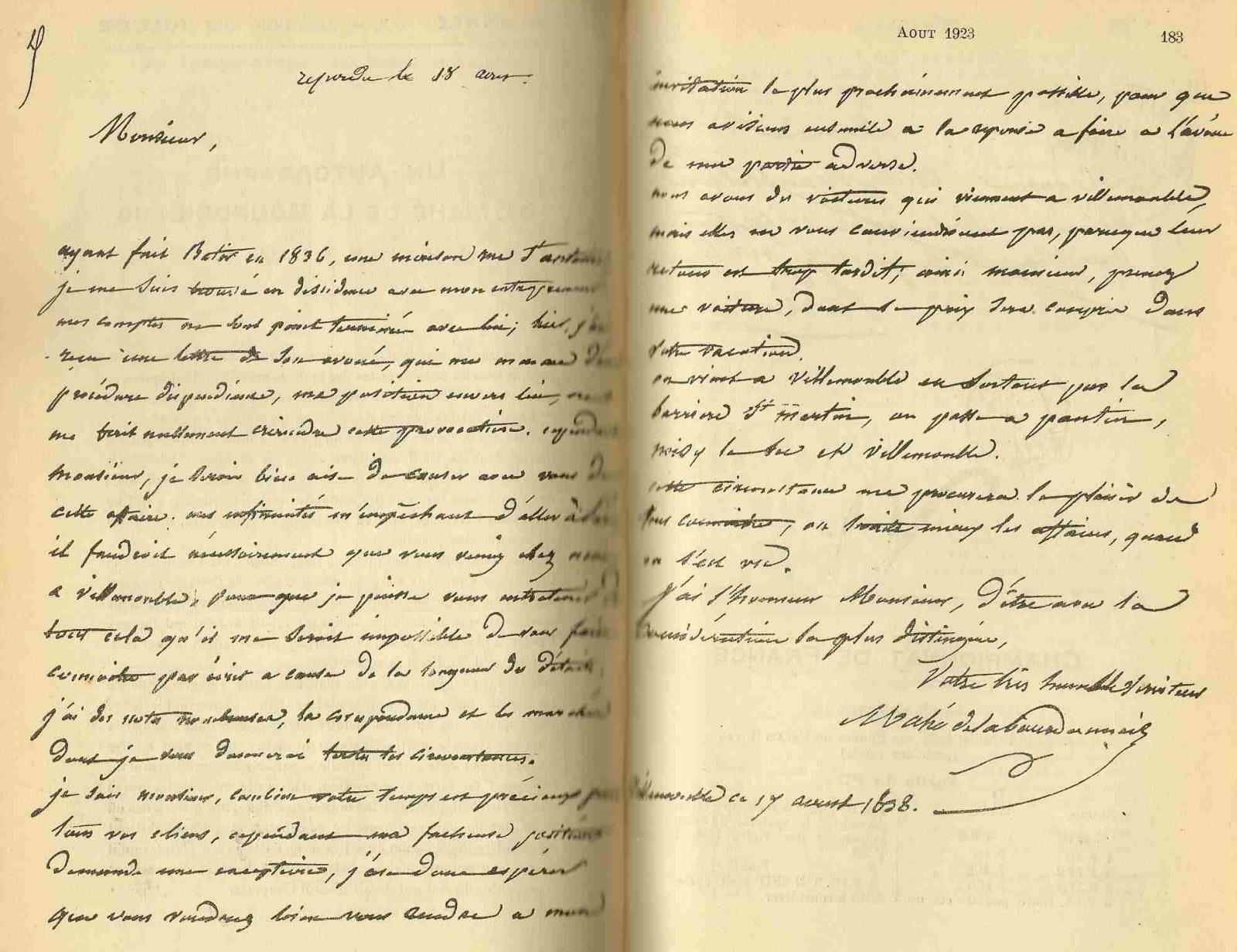

Below is an extract from Worlds of Chess Champions, a booklet issued by the Cleveland Public Library in October 2003:

Note: his place of birth and family background are discussed elsewhere in the present article.

As regards the illustration, it may be recalled that C.N. 3397 (see page 287 of Chess Facts and Fables) quoted the following passage about Labourdonnais by Sam Loyd on page 1884 of the Scientific American Supplement, 6 April 1878:

‘It is not generally known that a plaster cast was taken from his features at the time of his death and was brought to this country, and is at present in the possession of Mr Eugene B. Cook, the distinguished problemist, who prizes it most highly and takes peculiar pride in showing the stray locks of hair and whiskers that still adhere to the plaster.’

(5149)

Further to the comments by Staunton quoted in C.N. 5128 above, it may be added that at the start of its 1842 run, in a note entitled ‘Portrait’, Le Palamède stated that no picture of Labourdonnais had existed and that when the master died Deville took a plaster cast of his head. Marlet then undertook a portrait of Labourdonnais:

‘Il n’existe aucun portrait de Labourdonnais. A sa mort, M. Deville moula sa tête. C’est sur ce plâtre et les souvenirs qu’il en conservait que M. Marlet a osé entreprendre de remplir cette lacune. Nos lecteurs jugeront la ressemblance et sauront apprécier toutes les difficultés qu’un artiste de mérite a eu à surmonter pour faire revivre les traits de Labourdonnais.’

Pages 145-147 of the 15 March 1842 issue of Le Palamède carried an article ‘Phrénologie’ which discussed the characteristics of Labourdonnais’ brain. The opening paragraph reported that copies of the bust were to be found in London chess clubs and other haunts and that the master had been subjected to phrenological scrutiny:

‘Le buste de Labourdonnais que nous possédons dans notre Cercle des Echecs et qui se trouve à Londres dans la plupart des clubs et divans où se jouent les échecs, a été moulé sur lui après sa mort, par M. Deville. La tête, dont le travail est des plus soignés, fut soumise à l’examen de la société phrénologique de Londres. Le docteur Elliotson se chargea de présenter son rapport sur cette intéressante communication ...’

A chronology by Dr John van Wyhe of Cambridge University records that John Elliotson and J. DeVille were founding members of the London Phrenological Society in 1823.

(5176)

Jean-Michel Péchiné (Arbois, France) points out a high-quality photograph of Labourdonnais’ death-mask. [New link.]

(7822)

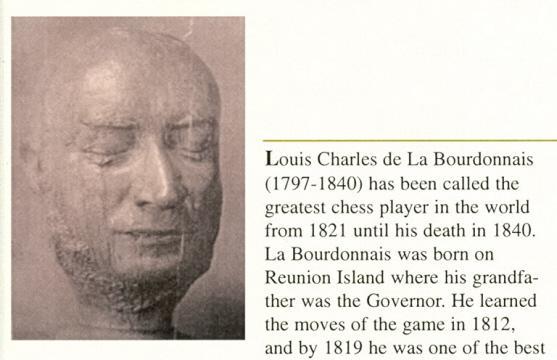

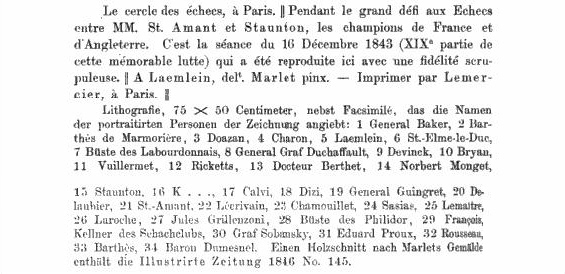

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) raises the subject of the 1843 illustration of Staunton v Saint Amant, which has been widely published (e.g. as a supplement to the November 1911 issue of La Stratégie). Noting that a key was given on pages 325-326 of volume two of Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels by A. van der Linde (Berlin, 1874), our correspondent has added numbers in the reproduction below:

(4259)

The Labourdonnais bust is number 7. For further details, see Pictures of Howard Staunton.

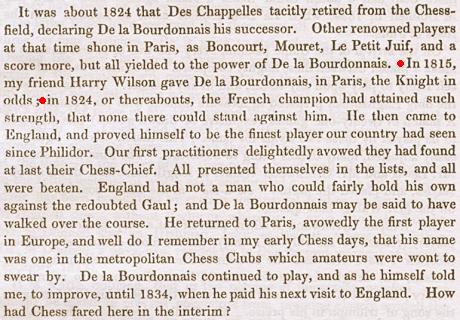

From Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada):

‘On page 112 of his book Chess & Chess-Players (London, 1850) George Walker wrote:

“My friend, Harry Wilson, once gave De la Bourdonnais the knight.”

Page 879 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913) states:

“In 1815, Harry Wilson, who was playing even with Lewis in 1819, had played with De la Bourdonnais, giving him the odds of the knight.”

In that footnote Murray cites Deutsches Wochenschach, 1912, pages 1-7, for a life of Labourdonnais but does not make it clear whether his information about the Frenchman’s play against Wilson is derived from that source. Where does the information come from (Walker’s book does not mention the year), and is anything more known about games between the two players?’

The article, by O. Koch, in Deutsches Wochenschach does not refer to Wilson, but the year 1815 was given by George Walker a few years before the appearance of his book Chess & Chess-Players. In an article dated October 1843 about the McDonnell v Labourdonnais games Walker wrote on page 371 of that year’s Chess Player’s Chronicle:

‘In 1815, my friend Harry Wilson gave De la Bourdonnais, in Paris, the Knight in odds.’

Walker’s account was not disputed by Wilson, whose familiarity with the Chronicle is shown by his writing about other matters on pages 57-58 and 146-150 of the 1844 volume.

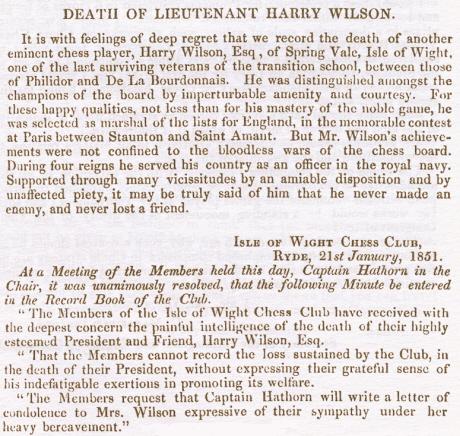

An obituary of Wilson was published on page 57 of the Chronicle in 1851:

...

(6506)

From Rod Edwards:

‘In C.N. 6506 you posted my query about Harry Wilson giving Labourdonnais knight odds in 1815, and you provided some additional information. I have just found a further reference by George Walker, in Le Palamède, 1842, page 320. He claimed not only that Wilson played Labourdonnais at knight odds but also that Wilson won several times. The year was given as 1816.’

The text in question:

‘M. Wilson est un des premiers noms anglais pour les échecs, et l’on peut le dire ici, puisqu’à Paris, en 1816, il gagna plusieurs fois Labourdonnais, en lui donnant le Cavalier. Ainsi changent et passent les gloires de ce monde.’

(6532)

Addition dated 10 December 2024:

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘A reference to the receiving of even greater odds by Labourdonnais from Harry Wilson appears in the following statement, albeit from a distant source:

“La Bourdonnais used to take the rook from Captain Harry Wilson, a player certainly far inferior to Légal.”

This statement appears in a footnote on page 9 of The Life of Philidor: Musician and Chess-player, by George Allen (Philadelphia, 1863). It is part of a discussion which mentions that even Philidor had at one time received odds, from Légal. If one considers that the alleged odds may have been received by Labourdonnais near the start of his chess career, it is perhaps not so surprising. Nevertheless, it is hard to have much confidence in the truth of the assertion quoted above, which is not evidence-based and was published after Wilson’s death in 1850. He was a lieutenant in the Royal Navy and did not achieve the rank of captain.

For a few biographical notes on Wilson, see pages 65-66 of my book Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton. He was born on 26 November 1788, so he could have been close to his peak in 1815 and 1816. However, his games in 1819 which appear in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Volume 1: 1485-1866 by D. Levy and K.J. O’Connell (Oxford, 1981) suggest that he was decidedly inferior to William Lewis at that time.’

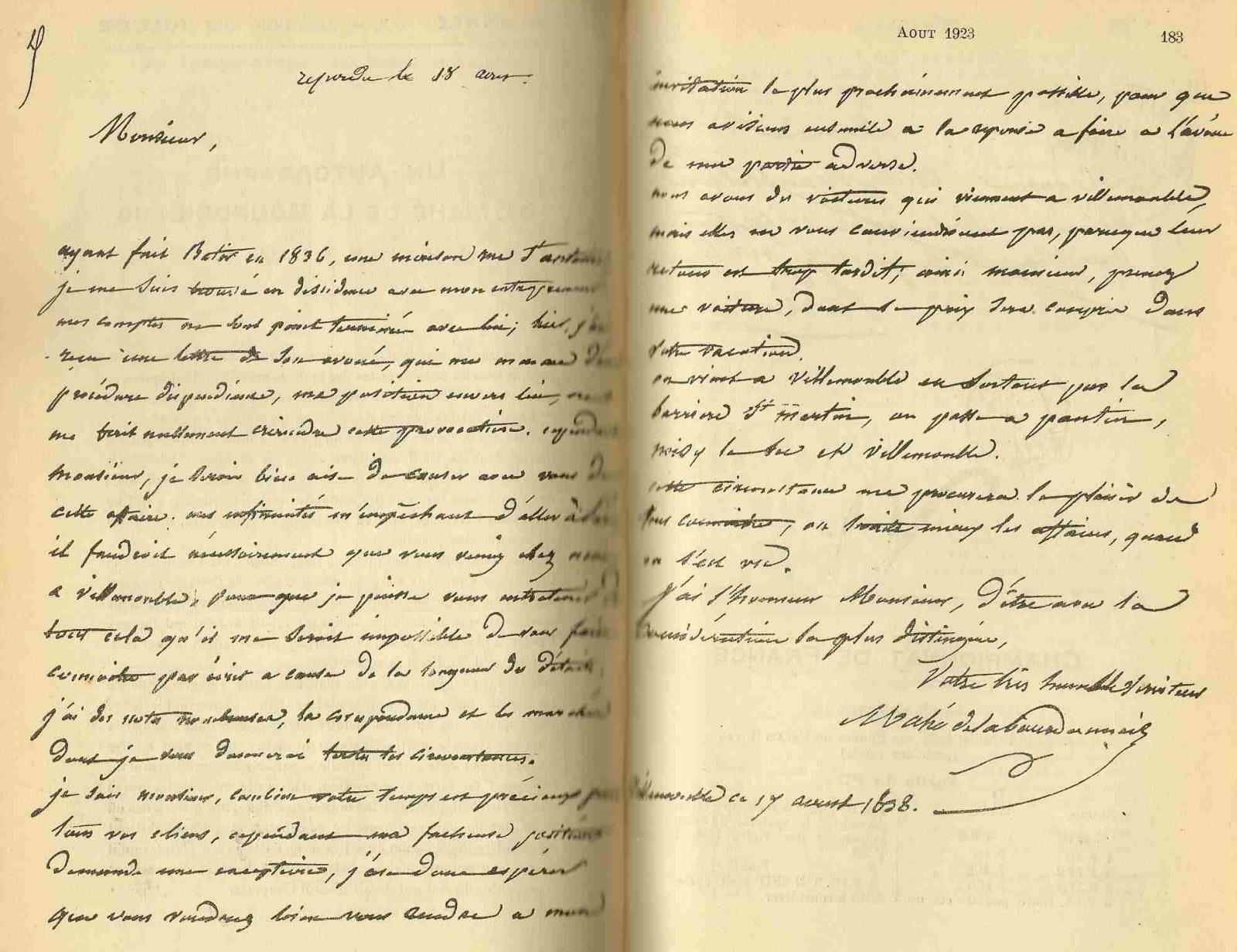

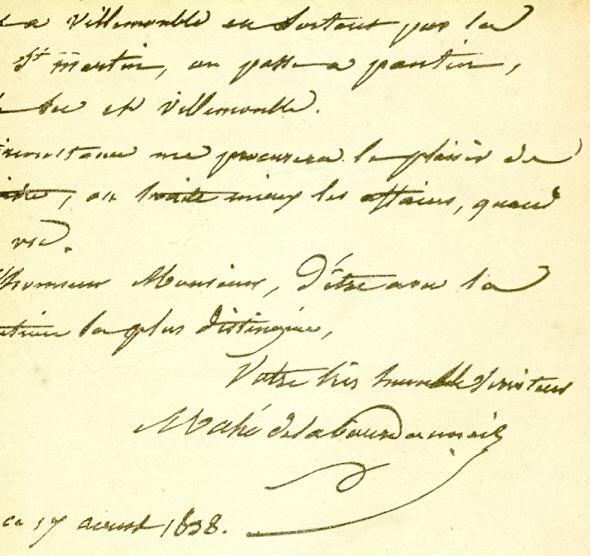

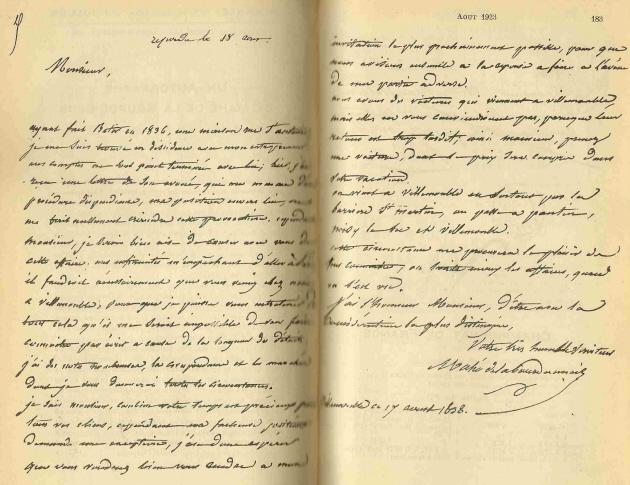

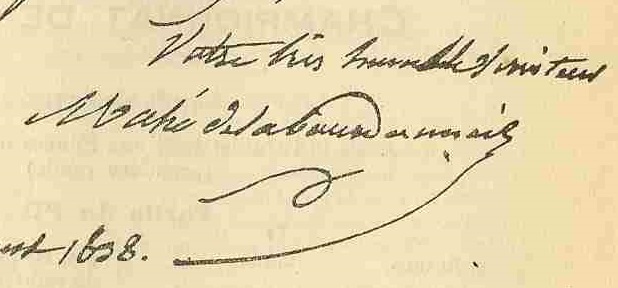

Pages 182-183 of the August 1923 issue of La Stratégie reproduced a letter written by Labourdonnais in 1838.

Unable to scan the full document from our bound volume, we wonder whether a reader could kindly provide a copy for reproduction here.

(7379)

Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France) has supplied a scan of the full letter:

(7383)

Rod Edwards writes:

‘Pages 71-74 of the November 1880 Chess Monthly have an article by Alphonse Delannoy, and page 74 describes an encounter between Labourdonnais and Mouret where the former announced mate in five moves in the final game of a series in which the stakes escalated dramatically. Labourdonnais offered a knight sacrifice, which Mouret accepted. Then Labourdonnais said, in Delannoy’s account: “Well, sir, you have lost the game. You are mated in five moves.”

It is stated that this occurred before Labourdonnais had directly challenged Deschapelles, and therefore presumably before their 1821 contest involving Cochrane as well, but after Mouret had been on a tour as director of the Turk. This places the event around 1820, though possibly a year earlier or later.’

(8367)

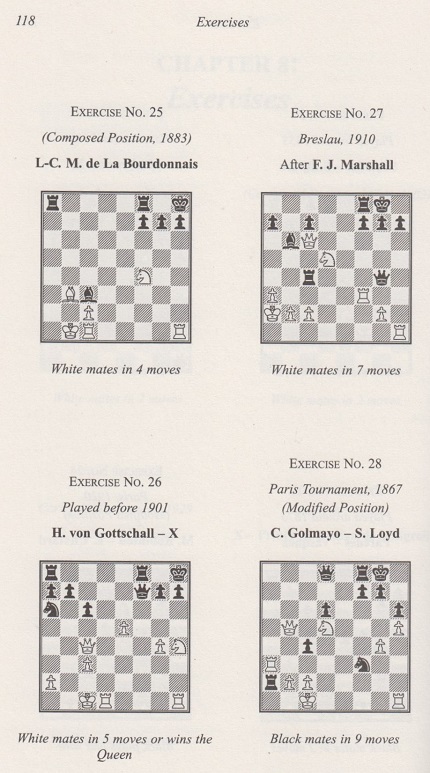

Two algebraic English-language editions of L’art de faire mat by Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn have been published recently, by Russell Enterprises, Inc. (Milford, 2014) and by Batsford (London, 2015). They are entirely different in approach and execution; one is a disaster, the other a missed opportunity.

The back cover of the Russell Enterprises, Inc. tome begins by erroneously stating that Renaud and Kahn wrote their book ‘in the early 1950s’, whereas the original appeared in the 1940s. It also proclaims:

‘In this new 21st-Century Edition, the antiquated English descriptive chess notation has been replaced by modern algebraic notation. Otherwise, it has remained true to its roots.’

The title has been changed (from The Art of the Checkmate to The Art of Checkmate, understandably enough), but ‘it has remained true to its roots’ is another way of saying that no attempt has been made to correct the colossal number of factual and other mistakes which appeared in the French original and/or in the English translation ... by W.J. Taylor ... (New York, 1953).

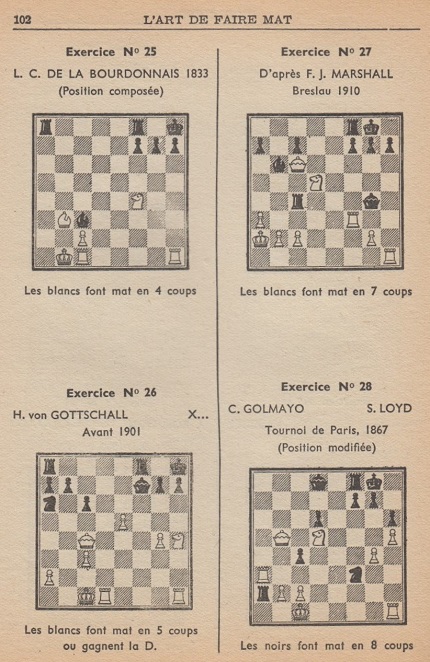

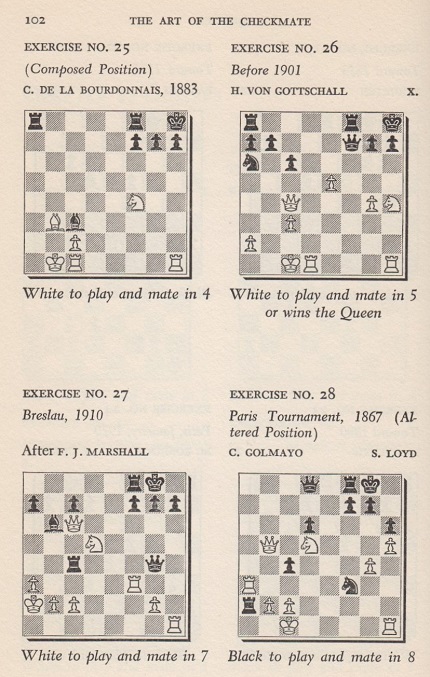

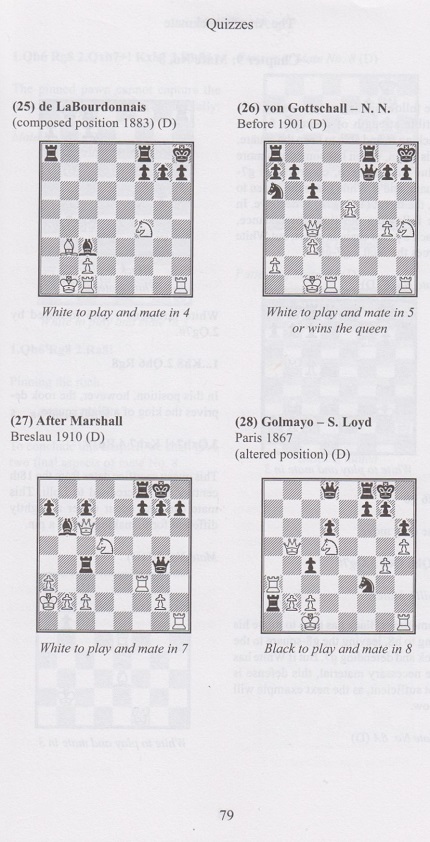

... Although a spot-check shows that the Batsford translation is, of course, vastly superior, insufficient effort has been made to improve the game references. As an example, we take page 102 of the original French edition ... :

1947

1953

2014

2015

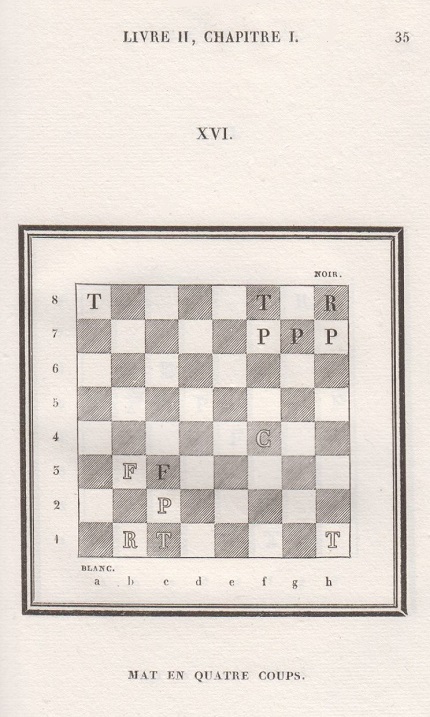

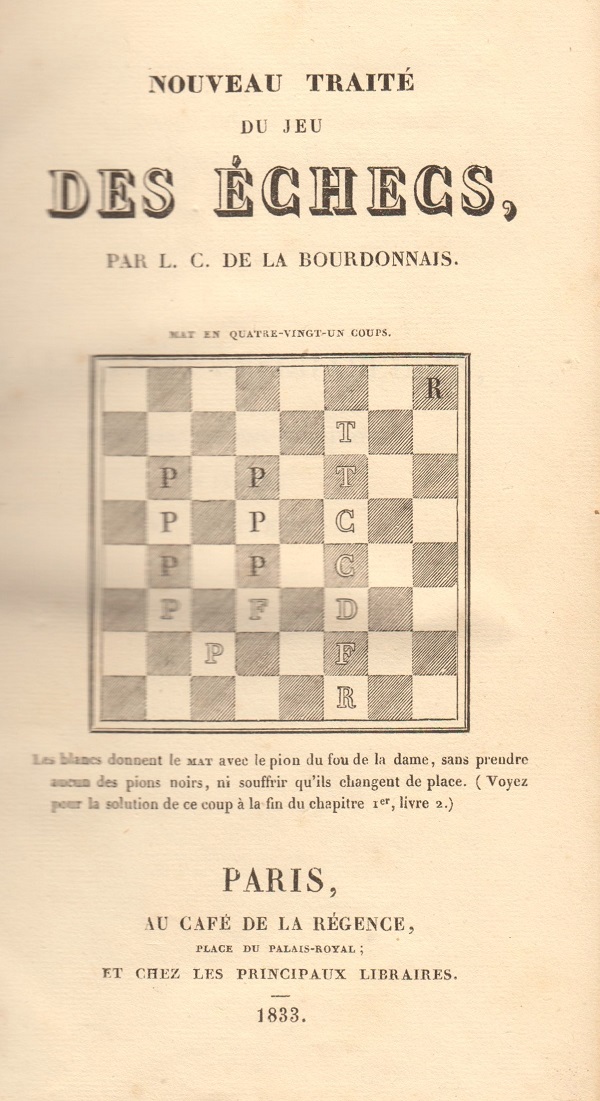

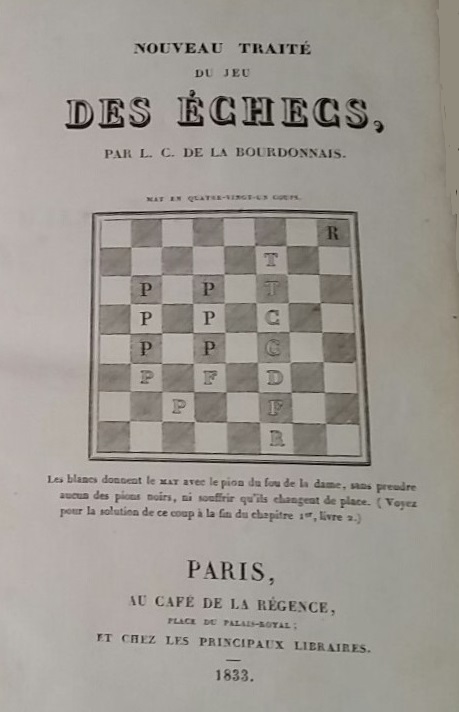

Thus all the English-language editions have ‘1883’ for the Labourdonnais position, even though Renaud and Kahn’s original French text was correct. The position had a page to itself in Labourdonnais’ book Nouveau traité du jeu des échecs (Paris, 1833):

...

(9149)

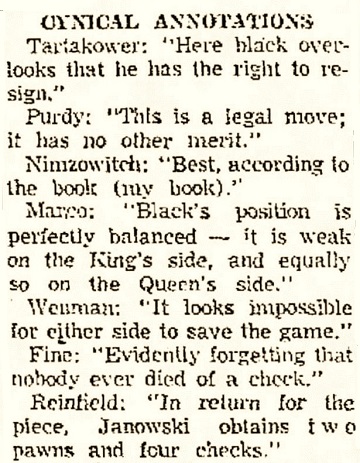

An extract from a column by George Koltanowski on page 10 of the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 20 May 1962:

As ever, factual information about such quotations is sought. The Marco one was discussed in C.N. 5248, and the remark ascribed to Reinfeld should also mention Fine. It appeared on page 141 of the book on Lasker which they co-authored.

It is, though, the Wenman item that deserves particular attention, since it brings to mind a remark widely attributed to Staunton. For example, an article by G.H. Diggle reproduced in C.N. 7369 [see above] stated with regard to writers who annotated the 1834 Labourdonnais v McDonnell games:

‘Staunton himself, who did so (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volumes 1-3), really sums up the series in a famous note to game 21: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

In an article about the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series on pages 277-281 of the July 1934 BCM Diggle wrote:

‘Some of their complications have driven annotators to despair. Staunton himself in one case can do no more than helplessly declare: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

The article was reproduced on pages 69-75 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951).

Presenting game 21 on pages 94-95 of Lessons in Chess Strategy (London, 1968) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘Staunton’s note after White’s 29th move makes an apt comment: “It now seems hardly possible for either player to save the game.”’

However, pages 83-84 of The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974) had the following with regard to a different game (50):

‘Beyond inserting a number of exclamation points it is useless to try to annotate this wildly uninhibited game. Howard Staunton, the famous English player, made the attempt some years later, only to give up with the historic remark: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game!”’

It took us a while to find confirmation of Staunton’s words (in connection with game 21), on page 133 of his posthumous book Chess: Theory and Practice (London, 1876). Below is the relevant page in a late edition (London, 1920, published under the title The Laws and Practice of Chess):

That leaves the question of why Wenman’s name was introduced for a similar remark, and we can give a citation from his book One Hundred and Seventy Five Chess Brilliancies (London, 1947):

That unnumbered page is game 53 in Wenman’s book and is, of course, part of his coverage of the above-mentioned game 21 in the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series.

(10171)

‘Labourdonnais’, ‘De La Bourdonnais’ and many variants exist in chess literature, and Ulvi Bajarani (Baku) asks whether a preferred spelling can be determined.

The present item leaves aside his forenames (Louis Charles Mahé can be found in various combinations) to focus on the surname. First, his signature on an 1838 letter shown in C.N.s 7379 and 7383 [see above]:

Next, his magazine, Le Palamède:

The introduction to the first issue had, on pages 6-7, ‘M. de la Bourdonnais’. An announcement on page 35 was signed ‘DE LA BOURDONNAIS’. Pages 428-429 had ‘M. de La Bourdonnais’ a number of times. Page 15 of the first 1842 volume of Le Palamède referred to ‘M. Mahé de Labourdonnais’, but ‘Labourdonnais’ appeared increasingly in the magazine.

Tolerance of several spellings thus seems advisable, but what about simply ‘Bourdonnais’? At the conclusion of a review of the Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld (Oxford, 1984), G.H. Diggle, the Badmaster, wrote in the December 1984 Newsflash:

‘The BM has left his one “grouse” till last – the eminent German master von der Lasa is always referred to as plain “Lasa”; worse still, the great La Bourdonnais appears throughout as “Bourdonnais”. To a diehard Tory like the BM, this “La-lopping” and cutting down the timber of the aristocracy has a nasty egalitarian look.’

The book review was reproduced on pages 12-13 of volume two of Chess Characters by G.H. Diggle (Geneva, 1987).

From page 202 of “Our Folder” (The Good Companion Chess Problem Club) 1 May 1921:

(4070)

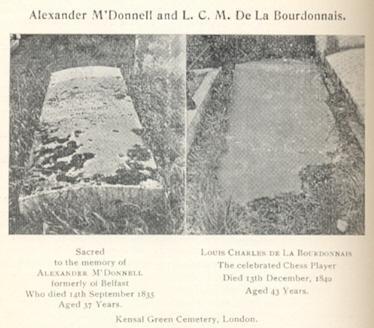

Detailed information about the location of the graves of both McDonnell and Labourdonnais was given by David Hooper on pages 514-515 of the November 1986 BCM.

Ulvi Bajarani asks whether the exact year, let alone the exact day, of Labourdonnais’ birth can be established.

C.N. 4070 reproduced from page 202 of “Our Folder” (The Good Companion Chess Problem Club), 1 May 1921 a photograph of the master’s grave in London with a caption indicating that he died on 13 December 1840, aged 43. However, the obituary of Labourdonnais by Saint-Amant in Le Palamède stated:

‘Labourdonnais qui était né en 1795, l’année même de la mort de Philidor, a été comme lui mourir à Londres, dans un état voisin de la pauvreté.’

The obituary was on pages 15-19 of the first issue of Le Palamède following its resumption, circa December 1841, after more than a year’s absence. An endnote referred to prior publication of the obituary:

‘Cet article avait été publié dans les feuilles quotidiennes en février 1841, deux mois après la mort de Labourdonnais.’

The matter will be pursued in future items with, we hope, readers’ assistance.

(11428)

John Townsend writes:

‘There is an interesting, though not always accurate, article about Labourdonnais the chessplayer in P.J. Levot’s Biographie Bretonne (volume II, Paris, 1857, pages 60-61). A footnote mentions that Louis-François Mahé de la Bourdonnais, the son of the Governor of the Ile de France and Bourbon, had a son Pierre-Marie-Philippe-Charles, who was born on 9 November 1773 and married, on 16 April 1796, Jeanne-Françoise Bunel. This couple is identified as the parents of the famous chessplayer, regarding whose birth the following is stated:

“On a quelques raisons de croire que Louis-Charles, issu de leur mariage, naquit, l’année suivante, à Paris, rue ou impasse Féron, où sa mère avait un hôtel, qu’elle a vendu depuis.”

The next sentence mentions, however, the absence of proof as to his place of birth. Although the passage quoted is rather vague as to the time of the birth, this possible answer has the advantage of associating the birth with a specific marriage, allowing for a suitable interval.

Birth during 1797 would make his age at death 43. That is the age given in the index of deaths of the General Register Office, in the burial register of All Souls General Cemetery, Kensal Green, where he was buried on 17 December 1840, and it is also the age which appeared on the headstone at his grave.

There are two references in Le Palamède to 1795 as his year of birth, but it is not explained how that year was arrived at, or who his parents were.’

(11492)

Addition on 20 November 2024:

From John Townsend:

‘In C.N. 11492 I gave reasons for thinking that Labourdonnais was born in 1797 in Paris. This has been vindicated, since Jean-Olivier Leconte subsequently took that line of research much further on his website on 11 and 13 November 2022.

I believe that he has established that:

a) the parents of Labourdonnais had a hotel in Paris at 4 rue Férou, “rue Féron” (as in Levot, referred to in C.N. 11492) being a typographical error; and that the chessplayer was born in Paris on 25 May 1797;

b) he was the great-grandson, not the grandson, of the Governor. (A family tree is shown in Mr Leconte’s research.)’

In the chapter on the 1834 Labourdonnais v McDonnell encounters, page 14 of Kings of the Chessboard by Paul van der Sterren (Landegem, 2019) mixes up the chess master with his great-grandfather Bertrand-François Mahé de Labourdonnais (1699-1753):

(11443)

From Where Did They Live:

Labourdonnais, L.: 89 rue Richelieu, Paris, France (BCM, March 1887, page 86 – address in 1837).

From Chess Records, concerning the first chess magazine:

Le Palamède, edited by L.C.M. de Labourdonnais and J. Méry, began publication in 1836.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.