Edward Winter

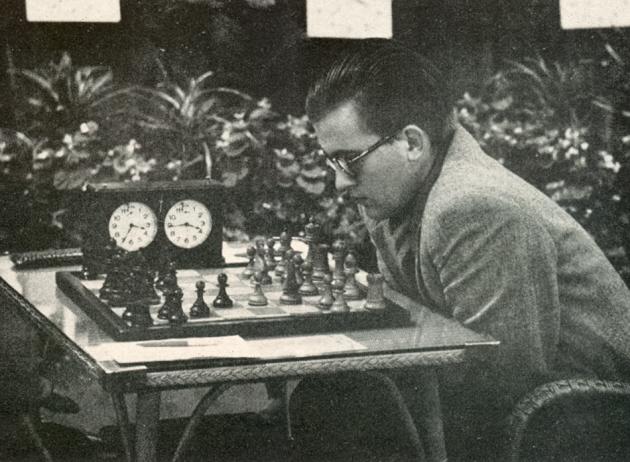

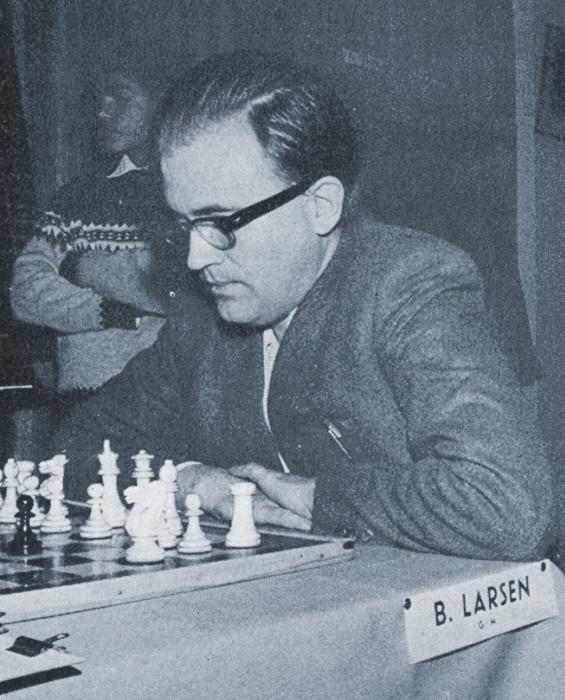

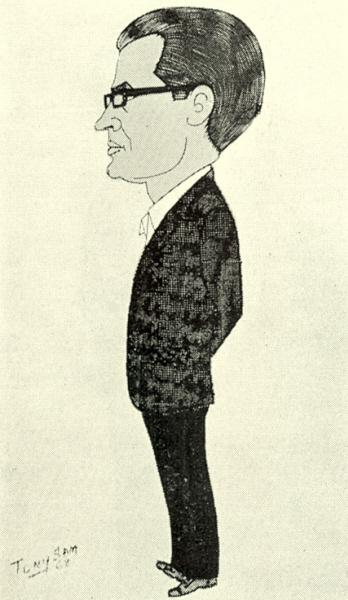

Chess Review, February 1957, page 35

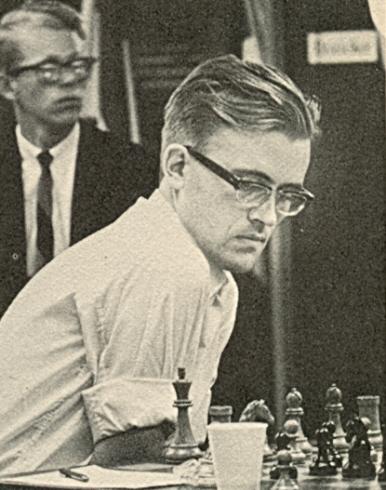

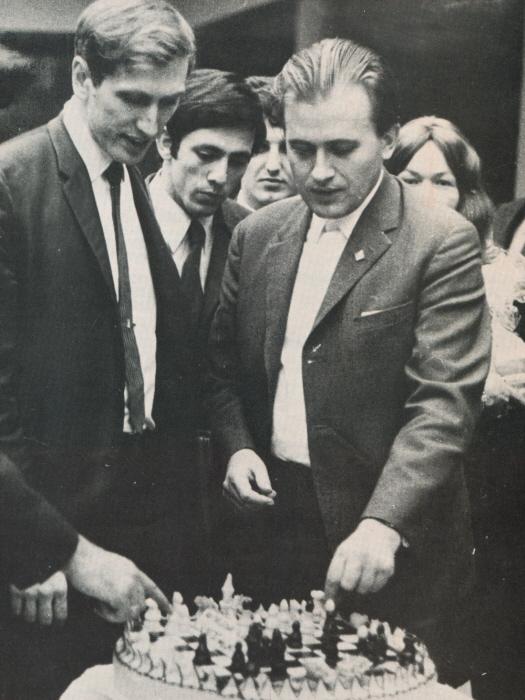

Chess Life, August 1966, front cover

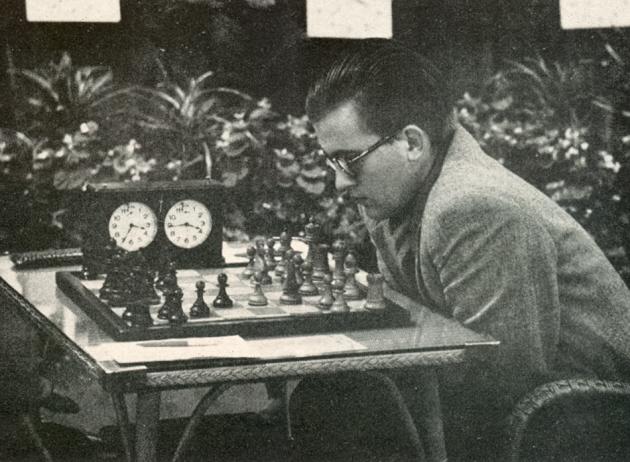

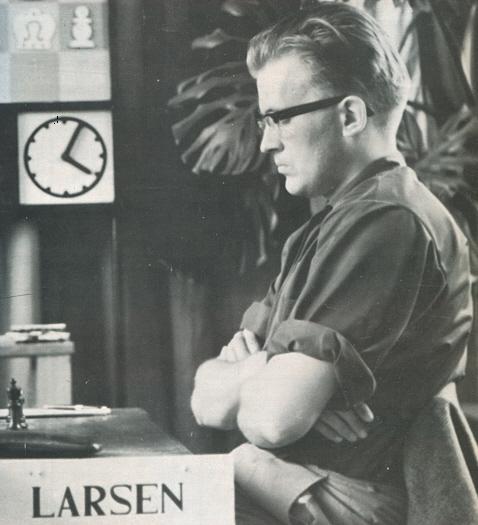

Second Piatigorsky Cup (Los Angeles, 1968), page xv

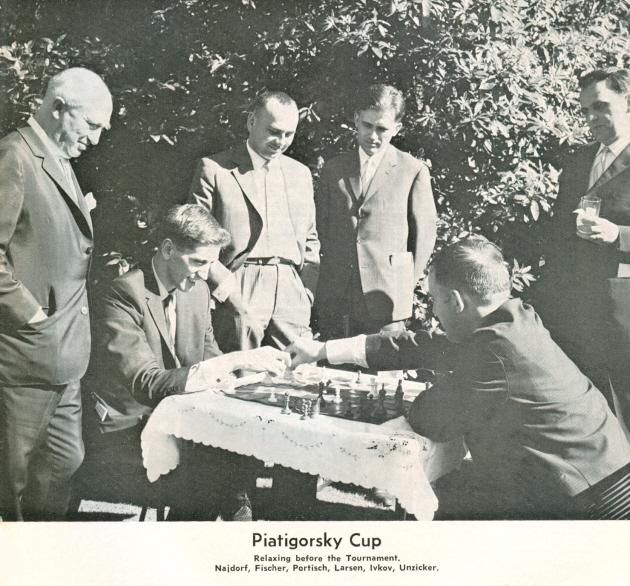

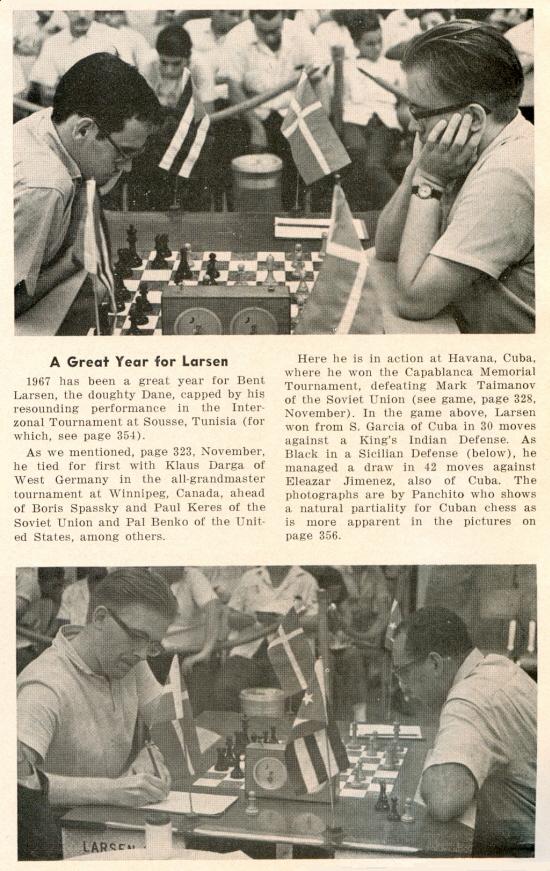

Chess Review, December 1967, page 355

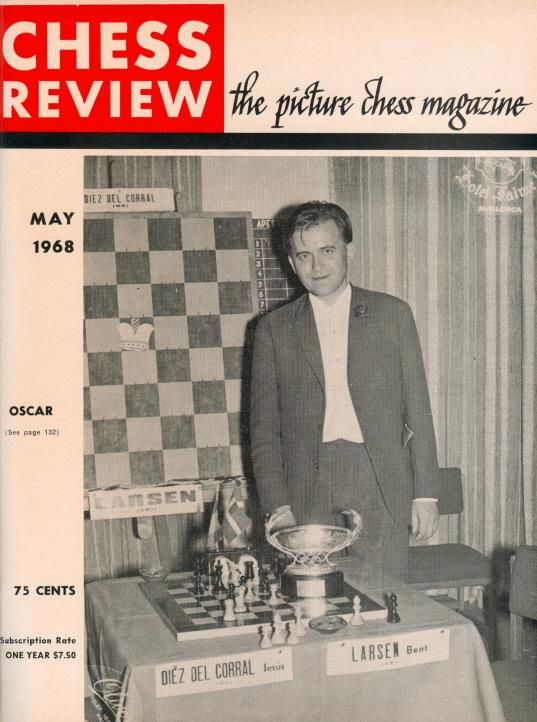

Chess Review, July 1968, page 195

Schweizerische Schachzeitung, November-December 1968, page 227

Palma de Mallorca, 1969 tournament book

Palma de Mallorca, 1969 tournament book

Fischer and Larsen, Chess Life & Review, July 1970, front cover

Chess Life & Review, October 1970, front cover

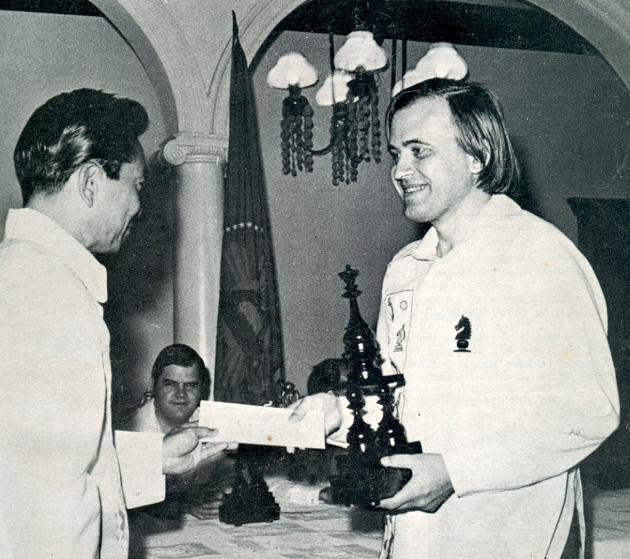

Ferdinand Marcos and Bent Larsen, Chess Life & Review, January 1974, front cover

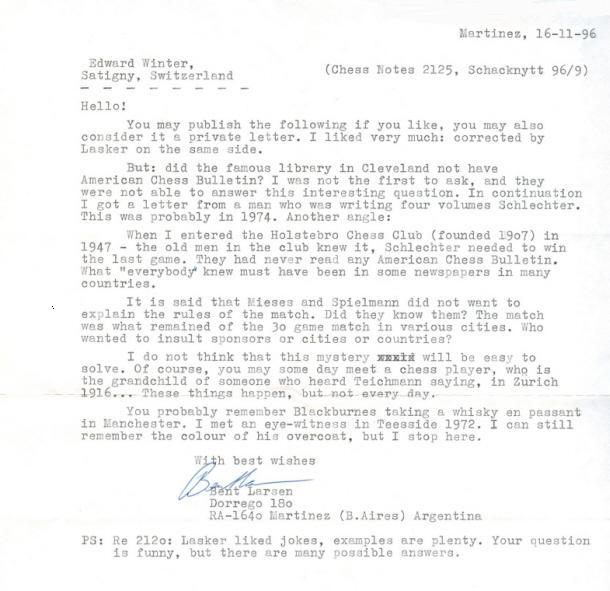

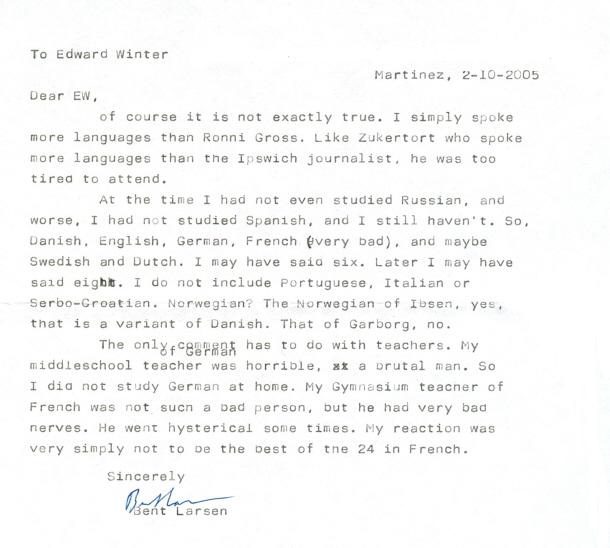

The letter below came in response to an enquiry from us about a published report on how many languages he spoke (see C.N. 4731):

It is sad news indeed that the Oxford University Press does not plan to produce any new chess titles in the foreseeable future with, we understand, the possible exception of future volumes of the Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games. A few are still trickling out, however, since these are works put into production before the fateful decision was taken. Thank goodness that Bent Larsen’s Good Move Guide (Oxford, 1982) was not a casualty. A modest 136-pager, it is lively, jolly and, most important of all, devoid of all the old hackneyed combinative brilliancies that have ruined more than one of its predecessors. The book is excellently translated from the original Danish by Lene Knudsen and Ken Whyld, and the highlight for us is the Find the Plan section (chapter 2) – surely such an instructive approach could be expanded into a whole book.

(108)

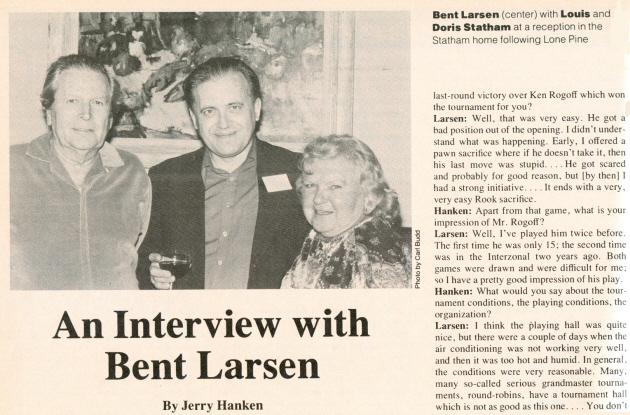

In an interview conducted by Jerry Hanken and published on pages 354-355 of the July 1978 Chess Life & Review Bent Larsen was asked about his first recollections of chess. His reply:

‘Well, I think I remember one of the first games I played against this boy who taught me ... I was six, almost seven, and I remember he taught me the rules and then we played. At the end he had two rooks and I had nothing, and he forced my king out to the edge of the board and mated ... I know which piece of chess news was the first one I saw in the newspapers. That was in ’46 but I’m already 11 at the time. The photo of the dead Alekhine in his cold hotel room, with his overcoat on and half-empty plate and head up ... Very famous photo, and it gave rise to a lot of speculations about how he died and maybe suicide, and so on.’

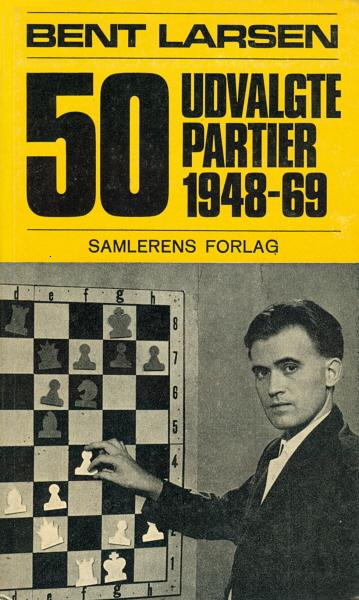

See also page 1 of Larsen’s Selected Games of Chess 1948-69 (London, 1970) and a brief interview in Kingpin.

The interview with Hanken took place at Lone Pine, 1978, and regarding his performance in that tournament Larsen stated: ‘A very good game without any risk was my game against Stean in the penultimate round. That was a very good piece of work.’

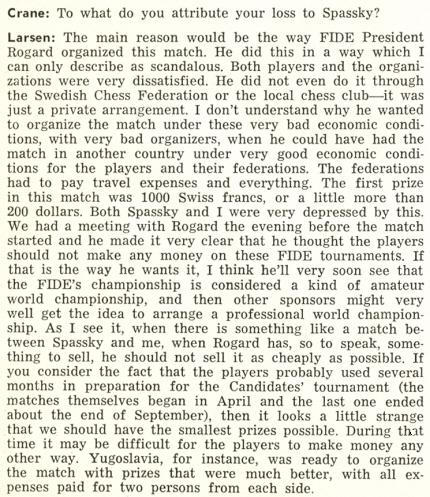

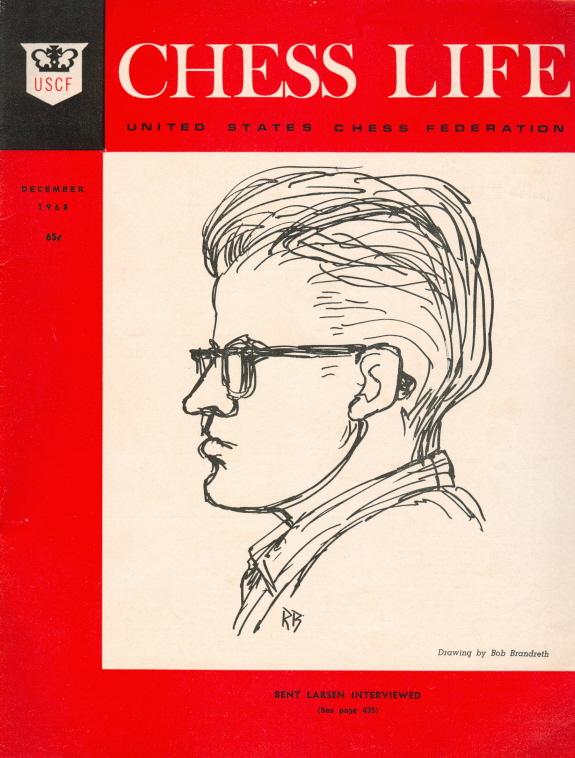

A decade earlier, Chess Life (December 1968, pages 435-438) published interviews with Larsen by Ben Crane and Jude Acers. Larsen was particularly critical of the organization of his Semi-Final Candidates’ match against Spassky in Malmö earlier that year:

Asked about his best game in the last year, Larsen replied: ‘...one of the best games I’ve played was my win against Gligorić in the Capablanca tournament. ... Another one was against Ivkov in Palma de Mallorca.’ As regards the best game of his career to date, he commented:

‘One of the best was against Geller in the Copenhagen tournament of 1960. Another was against Ivkov in Beverwijk, 1964. A third was in the Moscow Olympiad, 1956 against Gligorić. And of course there are the two games I won against Petrosian in the Piatigorsky Cup, and of these two games I rate the long one, without the queen sacrifice, as the better. But both games are very nice. ... if I should mention one, it would probably be either the game against Geller in 1960 or the one with Black against Petrosian in the Piatigorsky Cup.’

Larsen was also asked whether he had ‘any advice to aspiring masters’. His reply:

‘I think most of them study too much opening theory, and they should study more games by masters with annotations by masters.’

Regarding the best world zonal system, Larsen’s proposal was:

‘A panel of experts in FIDE would vote the eight strongest players into a tournament among themselves, preferably a double-round-robin. The selection of the eight would not be difficult at all. ... At present, Fischer, Spassky, Ivkov, Portisch, Petrosian, Korchnoi, Tal and myself. But don’t misunderstand, I greatly admire Botvinnik for remaining one of the world’s leading players.’

Another question was whether Larsen thought that the grandmaster title had been cheapened by the standards which FIDE set:

‘In the last ten years, yes. Many so-called grandmasters are not worthy of the title.’

Some further quotes:

‘I don’t care very much for miniatures. I don’t try to beat my opponents quickly because if they are strong I think I should respect them. It’s too risky to play very sharply to beat them in 20 moves.’

‘Botvinnik has never had very high respect for my play. One of the reasons is that he thinks I play too many different openings, and that I don’t concentrate enough on one or two openings like he did himself when he was younger.’

‘It is certainly true that he [Petrosian] isn’t much of a world champion, but I think it is proper that the title is decided in a long match. I am sure others feel that they are the strongest in the world. I certainly feel this way, so does Fischer, Spassky certainly. But Petrosian is, perhaps, the best match player.’

‘As you know, I always have confidence and I always try to win. I never make deals and I always compete to the end. I have the impression that I am willing to work on theory more than my opponents, particularly in the openings, but in the endgame as well. At Sousse no-one was quite sure if Reshevsky could hold a bad queen and pawn ending. They all found it out later. It is learning from practice, something inactive masters cannot get.’

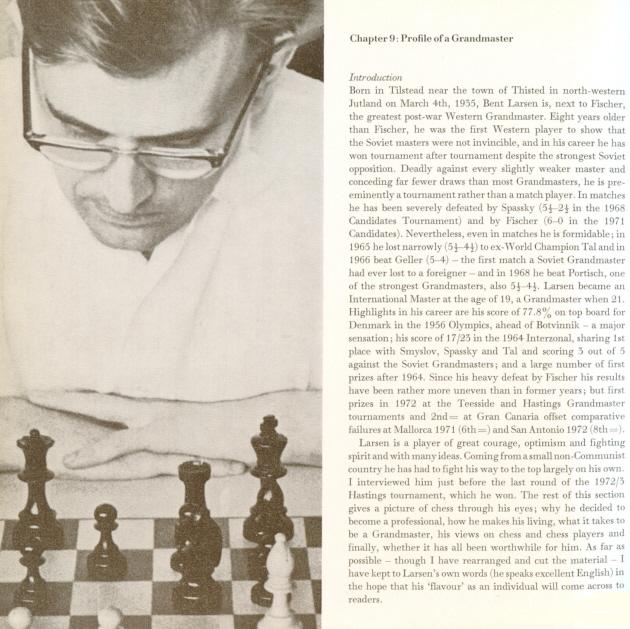

The best and most detailed interview with Larsen that we have seen was presented by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 86-94 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973) under the heading ‘Profile of a Grandmaster’. It took place shortly before the last round of Hastings, 1972-73:

‘I said once that I got a third of my income from tournaments, a third from exhibitions and a third from writing, but that is a very rough average – it varies very much from year to year. I make over £5,000 in a year, less than £10,000.’

Alexander asked whether exhibitions and writing about chess affected his play:

‘Exhibitions do not matter; they have nothing to do with the chess you play in tournaments. But writing is much more dangerous. The worst case was when I wrote my 50 Selected Games. My wife brought the English MS to the post office just the day I left for Puerto Rico. At Puerto Rico, I had original ideas – that was not the trouble – but in some games I suddenly realized that I had played stupidly and my opponent had played stupidly and that this game should never be published – and then I lost all interest and played terribly. I became too much of a perfectionist. I lost many games because of this.’

A further selection of quotes:

‘The main thing is not to be afraid of losing. Why should I be afraid? Although chess is my profession and a very important part of my life, if I lose I know two things: first, it is only a game, and second, by taking the risks I do I will win more than I lose. For some masters losing at chess is almost like dying; for me this is absolutely not so.’

‘... although I am famous for taking risks, I don’t usually take very much of a risk; unlike Tal – who doesn’t care whether his position is good or bad if only it is complicated enough – I don’t like bad positions.’

‘Tal and Korchnoi were probably born with a greater gift for analysis than I was, and I was born with a greater gift than Smyslov or Petrosian; and in positional insight it is the other way round. Korchnoi is fantastic at calculating complex variations, especially when he is hard pressed; but he must analyse because his judgment when he doesn’t calculate is very bad – he has to get through a lot of variations before he knows what’s happening.’

‘Bronstein has influenced me – maybe Keres, but not so much; I like Keres’ book but I do not admire Keres as a chess artist. Keres is not an artist, he is a practical player. As a young player he was practical in a different way; his brilliancies were all rather conventional. I doubt that he has ever tried to be an artist and if he has he gave it up in the Second World War – and also gave up the hope of becoming world champion. I mean the following: Keres said to me once: “Sometimes I sit for 20 minutes and I know that some spectators are thinking that now there is something very deep coming: you know what’s happening? I can’t find any ideas and I am taking a nap – except for snoring and closing my eyes.” A player like Bronstein would never do that; he would be trying all the time.’

‘If there is time enough for both adjournment analysis and sleep, I find seconds only useful as life guards (keeping disturbances away), shoe shiners and errand boys. I would not like to rely on analysis by somebody else.’

‘If I were put back in the early 1920s, it would be easy, very easy, to be world champion. There would be many draws, but in enough of the games I would get opponents into positions they didn’t understand. Most people find this arrogant – but now we know so much more. If we take positions they understand, we are not better; but we know more types of position. It is a matter of selecting the right openings. Of course, the 1920s was a period of breakthrough in ideas; it would be much easier still if you went back to the early 1900s. The first real uncertainty is with Alekhine; he didn’t want to play the new openings – he didn’t like them – but he worked hard at them and he developed. Alekhine was not basically creative – he was a practical player, but he learnt from others. Not Capablanca – he had difficulty with the new openings in his later years.’

‘The Fischer/Spassky match was not a bad match – although these title matches are never good. People forget that because they remember the best games.’

‘In spite of my 6-0 defeat at Denver [against Fischer in 1971], I think that I would have a better chance than Spassky. It is true that I am a better tournament than match player, but I think that I am learning to play matches. At Denver it was very hot and dry, and this climate did not suit me. Yes, I think that I would have a chance in another match with Fischer; I do not think he is technically superior. After all, he is only 3-2 up against me in other games.’

‘I think that it would be very easy to have a world championship and a Candidates’ tournament every second year. One could use Elo ratings for selection, or, better, a committee which used the Elo ratings when there was nothing special against them. Select 16 players – four will be surprised and pleased that they are considered as world championship candidates and nearly all the others will certainly be the right choices; everyone will be satisfied – except the little countries which want a system which will include their players in a world championship. In the Olympiads I did not play this year because I am in principle against individual Elo ratings for games in international team tournaments. It does not hurt me personally, but they should not count because the situation is different in team events; you must play for the team score. But these little countries whose players never go abroad like their players to have a rating – so they love it.’

‘The trouble is that FIDE is a very weak organization. It has no money – and therefore makes no money.’

‘At Hastings about a quarter of all male spectators seem to rattle coins in their pockets – even if they sit in the first row. In Yugoslavia they will applaud if Tal sacrifices his queen – that is different.’

‘In England chess writing is a special thing; English players write when they are 20 – it is too young. It is very bad for their chess. In other countries they do not become writers so early.’

‘Being a professional you are very much your own boss and that is very important for me. If you feel you are playing interesting, creative and original chess then – why ask what you get out of it? No-one asks a painter or a violinist – it is accepted; why ask the chessplayer?’

‘Do I worry about my play when I’m 50? I think about it – but it doesn’t worry me very much. I shall probably be the strongest 50-year-old ever. Yes, that is a typical piece of optimism and it may not come true – that is largely a health problem. But I shall be one of the strongest – and I think that I shall win more tournaments than anyone else has done at 50.’

‘Advice? I would not advise someone whether to become a professional or not – I don’t give people that kind of advice; a man must make up his own mind. But if he had decided to become one, then I would certainly tell him that the most essential thing is to fight – and treat the first five years as training. Don’t accept a draw when Petrosian offers it – and don’t worry if you lose afterwards. It is a worse defeat to accept a draw prematurely than to lose – that they must get used to. Writing? That is a difficult problem, because it will help him to earn a living, but too much is bad for play. But don’t take a premature draw. Never.’

Wanted: original explanations by masters who won tournaments. Larsen accounted for his victory in the 1967 Sousse Interzonal as follows:

‘I won the tournament because nobody tried to win it. Gligorić and Geller were concerned only with qualifying.’

Source: Jaque Mate, 1/1968, page 1.

(1209)

From page 1 of Larsen’s Selected Games of Chess 1948-69 by Bent Larsen (London, 1970):

‘It appeared that my father knew the game, and we sometimes played. When I was 12 I beat him almost every time; then I entered the chess club. At that time I also began to borrow chess books at the public library. I even found a chess book at home – nobody knew how it had got into the house. Probably the former owner had forgotten it. This book had a certain influence on the development of my play. About the King’s Gambit it said that this opening is strong like a storm, nobody can tame it. In the author’s opinion modern chess masters were cowards, because they had not got the guts to play the King’s Gambit. Naturally, I did not like to be a chicken and, until about 1952, the favourite opening of the romantic chess masters was also mine.’

Which book was it?

(4475)

From Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark):

‘The book that influenced the young Bent Larsen’s choice of openings was Kan De spille Skak? by Andreas Nissen (Copenhagen, 1919). A second edition was published in 1923. The full introduction to the King’s Gambit (pages 81-82) reads:

“This important and enormously interesting opening is age-old and comes from Italy. In the language of this country ‘dare il gambetto’ means to put a leg forward. The opening was already referred to in a 1561 work by Ruy López. The King’s Gambit is a gigantic opening and demands a free spirit. It roars like a storm, and only giants can defy it. Nothing shows the impotence of the present day more than the fact that nobody believes himself capable of playing the King’s Gambit any longer. The chess masters shun it like the plague. In the King’s Gambit the chess spirit rises to dizzying heights, where the modern pawn technique apparatus fails like a bad motor.

Morphy valued the King’s Gambit very highly, and it was a fearful weapon in his hands. Adolph [sic] Anderssen immortalized it in his famous game against Kieseritzky – but then Anderssen was not a master whose only concern was points, points and more points, preferably paid for piece by piece by a business-wise tournament committee.”

Nissen was obviously an inveterate romantic and had little good to say about closed openings or the tournament players and praxis of his day. Often he was altogether unable to hide his contempt. About the Caro-Kann he commented on page 100:

“This opening is even worse than the ‘Sicilian Game’ and leaves all the initiative to White. It was introduced into playing practice by the Viennese player Kann, while the German Caro messed about with it, although it cannot be claimed that he improved it ...”

On the same page he wrote of the variation 1 e4 c6 2 c4:

“It cannot be asserted that with the move 2 c4 White obtains anything at all. He indicates with this move that he is as big a coward as Black, who, terrified by the sight of White’s first move e4, tremblingly drags his c-pawn to c6. The opponents match each other well.”

Andreas Nissen (1881-1950) wrote other manuals for beginners and books on the endgame, and he edited the chess column in the newspaper Berlingske Tidende. In his obituary on page 146 of the August 1950 Skakbladet “E.C.” characterized him as follows:

“... with Nissen, the Copenhagen Chess Club has lost one of its old, esteemed members, a gifted and well-informed man, an ardent chess enthusiast, and a splendid attacking player of the old school. He was devoid of ambition in chess, and rather sought in the game the satisfaction of a strong sense of chess aesthetics and need for excitement – circumstances which may explain why, despite his unquestionable chess talent and theoretical knowledge, he never reached the top as a practical player ...”’

(4480)

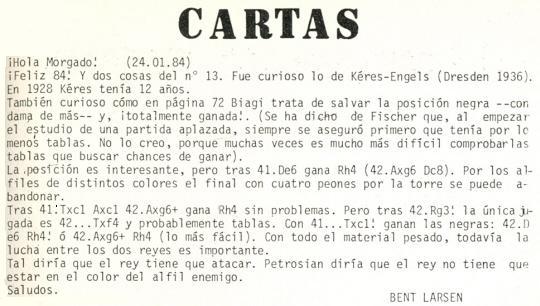

C.N.s 4973 and 5003 discussed the so-called ‘Lilienthal system’ in adjournment analysis: firstly seeking a means of drawing and then looking for a possible win. Now, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) draws attention to a letter from Bent Larsen dated 24 January 1984 and published on page 239 of the February 1984 issue of Ajedrez de Estilo:

Larsen wrote:

‘It has been said of Fischer that when he began to study an adjourned game he would always first ensure that he had at least a draw. I do not believe it, because often it is much more difficult to check for drawing lines than to look for winning chances.’

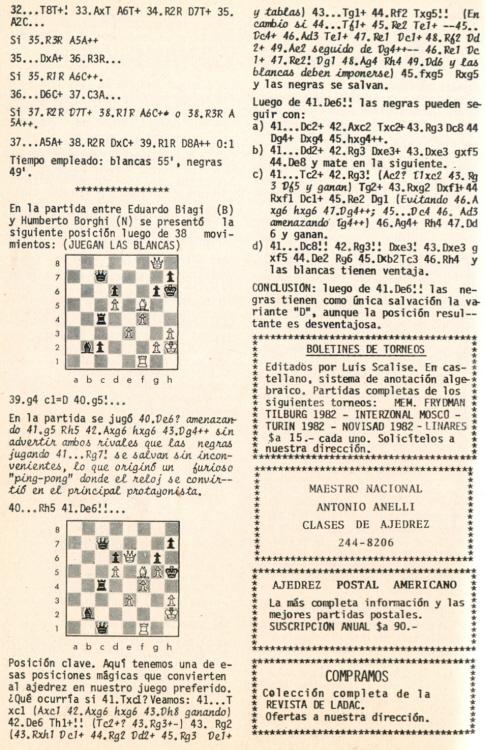

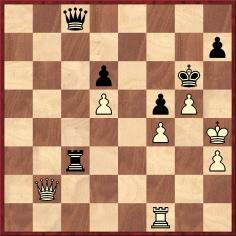

Larsen’s comments about the game between Eduardo Biagi and Humberto Borghi (the conclusion of which had appeared on page 72 of the December 1983 issue of the Argentinian magazine) are also of interest. The game was played in a tournament in Buenos Aires (September 1983) in which the players had one hour for all their moves. Below is the relevant part of the tournament report:

In this position play continued 39 g4 c1(Q)

40 Qe6, threatening 41 g5+ Kh5 42 Bxg6 hxg6 43 Qg4 mate. Neither player noticed that Black can save himself with 41...Kg7. Instead, it was recommended in the magazine, White should have played 40 g5+ Kh5 41 Qe6, after which four variations were given. Of these, it was stated, only (d) would give Black any hope of salvation: 41...Qc8 42 Kg3 Qxe3+ 43 Qxe3 gxf5 44 Qe2+ Kg6 45 Qxb2 Rc3+ 46 Kh4. It was not indicated exactly how the game ended.

In his letter Larsen wrote:

‘The position is interesting, but after 41 Qe6, 41...Kh4 wins (42 Bxg6 Qc8). On account of the bishops of opposite colours, the ending with four pawns for the rook can be resigned.

After 41 Rxc1 Bxc1 42 Bxg6+, 42...Kh4 wins without any problems. But after 42 Kg3! the only move is 42...Rxf4, with a probable draw. With 41...Rxc1! Black wins: 42 Qe6 Kh4! or 42 Bxg6+ Kh4 (the easiest). With all the heavy material, the battle between the two kings is still important.

Tal would say that the king must attack. Petrosian would say that the king must not be on a square of the same colour as the enemy bishop.’

(7075)

C.N. 8350 invited readers to submit the scores of simultaneous games in which they were involved.

From Bent Kølvig (Rødovre, Denmark) comes a game from a clock simultaneous display in which Larsen scored +6 –3 =1:

Bent Kølvig – Bent Larsen

Copenhagen, 6 June 1957 (10 boards)

Benoni Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 e6 4 Nc3 exd5 5 cxd5 d6 6 e4 g6 7 Be2 Bg7 8 Nf3 O-O 9 Nd2 Ne8 10 O-O Nd7 11 f4 Rb8 12 a4 f5 13 exf5 gxf5 14 Nc4 Nb6 15 Ne3 Nf6 16 a5 Na8 17 Bd3 Ng4 18 Nxg4 fxg4 19 Be3 Nc7 20 Qc2 Qh4 21 Ne4 Ne8 22 Rab1 Bf5 23 Nxc5 Bxd3 24 Nxd3 Qh5 25 f5 Rxf5 26 Nf4 Qg5 27 Bxa7 Ra8 28 Ne6 Rxf1+ 29 Rxf1 Qxd5 30 Nxg7 Nxg7 31 Qf2 h5 32 Kh1 Re8 33 Bd4 Qe6 34 b4 Qe7 35 b5 Ne6 36 Qa2 Qd7 37 Qd5 Re7 38 a6 bxa6 39 bxa6 Rf7 40 Qa8+ Nd8 41 Rxf7 Kxf7 42 Qd5+ Qe6 43 Qxe6+ Nxe6 44 Bb6 Resigns.

From page 16 of Wonderboy by Simen Agdestein (Alkmaar, 2004):

‘Magnus impressed in this Gausdal tournament [in 2000] even if he had just been actively playing tournament chess for half a year. The previous autumn Magnus and his father had sat and read Bent Larsen’s “Find the Plan”, one of the many good books written by the old Danish world-beater. The book consists of lots of diagrams that pose the task: Find the plan! Simple and effective.

At Gausdal it was obvious that Magnus knew a bit about the opening. His father had some old chess biographies lying around, and Magnus had “thumbed through” them. His first opening book was “The Complete Dragon” by grandmaster Eduard Gufeld [and Oleg Stetsko], a comprehensive work in English reckoned more for grandmasters than small boys who had just learned how to play.’

In the 2013 edition, this passage (stylistically unimproved) is on page 20.

Page 19 of the Italian translation (Rome, 2006) of Agdestein’s original book suggested clearly that the Larsen book was in English (‘L’autunno precedente insiema [insieme] a suo padre aveva letto il libro di Bent Larsen Find the Plan ...’), but no such book exists. Larsen’s work was published in Danish as volume two in his series of four booklets, Bent Larsens Skak Skole, the title being Find planen (Samlerens Forlag, Copenhagen, 1975):

We also have the Swedish translation, Du måste ha en plan (Stockholm, 1977). The four parts of the Skak Skole series were brought together in an English edition entitled Bent Larsen’s Good Move Guide (Oxford, 1982).

The English book, in turn, was translated into French as Les coups de maître aux échecs (Paris, 1989).

(8935)

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) notes that although only volumes 1-4 of Skak Skole were included in the English and French compilations of Bent Larsen’s booklets, there were further Danish volumes. The series (1975-85) was:

1. Find kombinationen (Find the combination)

2. Find planen (Find the plan)

3. Find mestertrækkene (Find the master moves)

4. Praktiske slutspil (Practical endgames)

5. Solide åbninger (Solid openings)

6. Skarpe åbninger (Sharp openings)

7. Flere mestertræk (Further master moves).

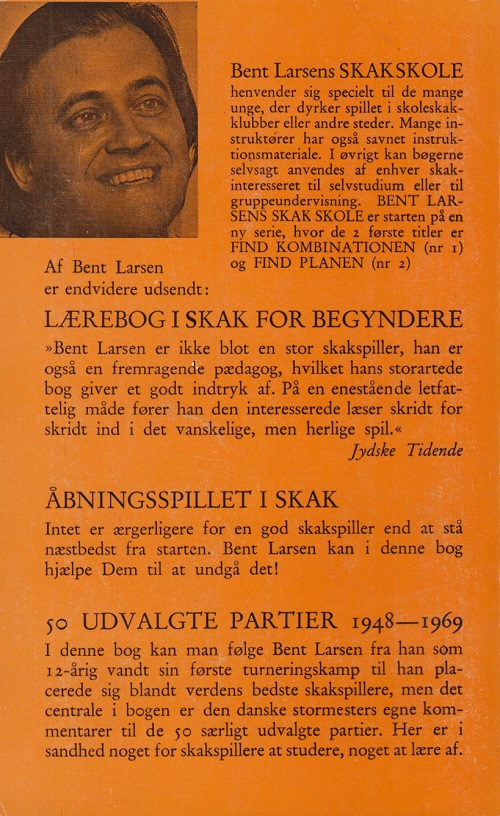

The back cover of the first booklet (Copenhagen, 1975):

Mr Skjoldager adds that volumes 1-6 have been translated into Norwegian.

(8939)

An article by Julio Kaplan (‘Games from Lone Pine’) on pages 364-366 of the July 1977 Chess Life & Review stated on the final page:

‘... as Lasker used to say: “Long analysis, wrong analysis”.’

Chess literature has references by the barrowful to what this or that master ‘used to say’, but responsible writers do not diffuse such material without secure sources. The ‘long/wrong’ saying is commonly attributed to Larsen, e.g. by A. Soltis on page 190 of The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked (Jefferson, 2000) and on page 27 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008). In each case the wording offered was ‘long variation, wrong variation’, and the corroboration offered was zero.

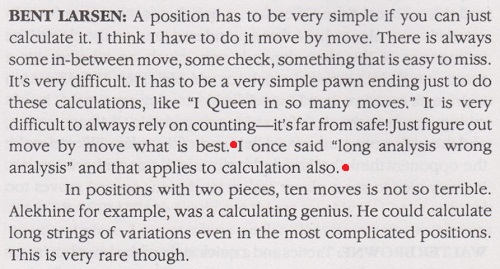

Larsen’s own words are shown below from page 46 of How To Get Better At Chess by L. Evans, J. Silman and B. Roberts (Los Angeles, 1991), in the chapter ‘How Do Top Players See Things So Quickly?’:

(9260)

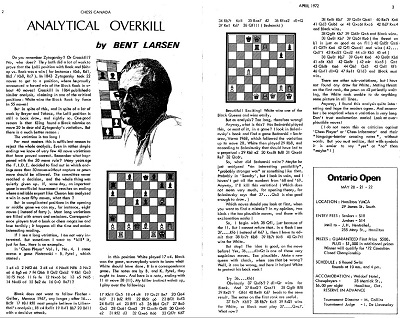

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) recalls an article, ‘Analytical Overkill’, by Bent Larsen on pages 2-3 of the April 1972 issue of Chess Canada:

The article began:

‘Do you remember Zytogorsky? Or Crosskill? No, who does? They both did a lot of work to prove that the Lolli position with rook and bishop vs rook was a win (for instance: Kb6, Rd1, Bb5/Kb8, Rc7). In 1843 Zytogorsky took 22 moves to get to a position where he proudly announced a forced win of the black rook in about 40 moves. Crosskill in 1864 published a similar analysis, claiming in one of the critical positions: White wins the black rook by force in 55 moves.

But in spite of this, and in spite of a lot of work by Breyer and Takács, the Lolli position is still a book draw, and rightly so. One good reason is that Kling found a Black mistake on move 20 in dear old Zytogorsky’s variation. But there is a much better reason:

The variation is too long.’

From later in the article:

‘Most long variations are filled with errors and omissions. Correspondence players trust a book or chess magazine and lose terribly. It happens all the time and makes interesting reading.

If I see a long variation, I am not very interested. But sometimes I want to “kill” it, just for fun.’

After giving an example, Larsen commented:

‘Beautiful! Exciting! ... But as analysis? Too long, therefore wrong!’

The article concluded:

‘And remember: be sceptical when a variation is very long.’

(10086)

See too C.N. 10037.

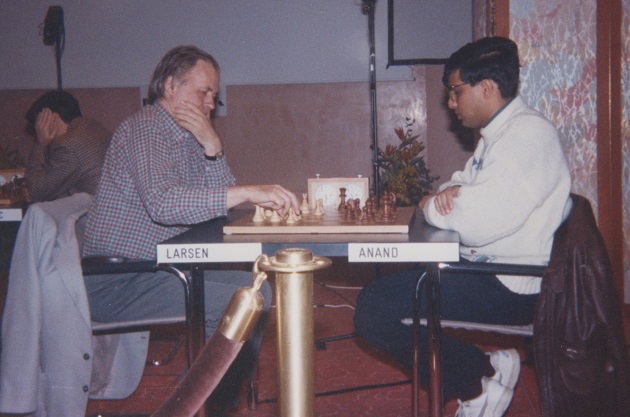

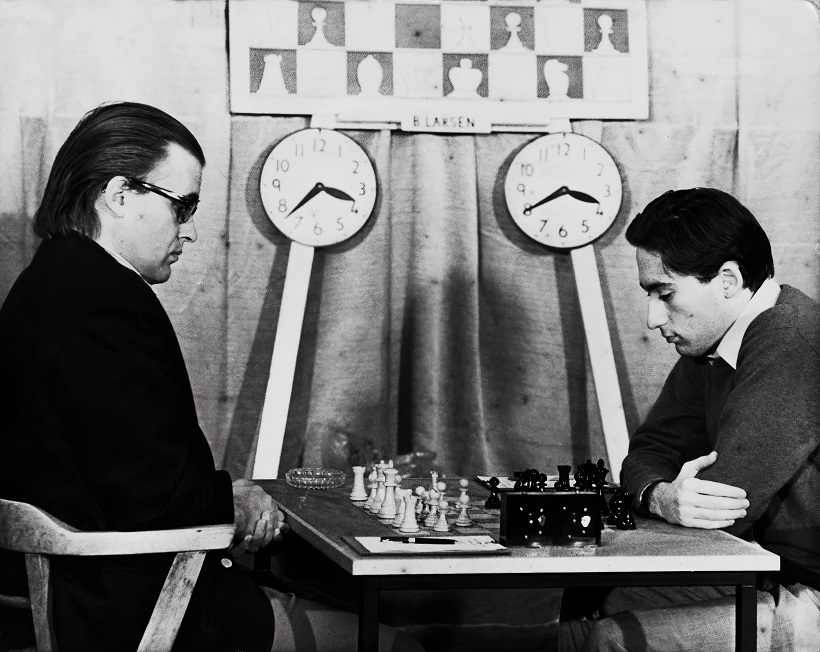

From our collection:

Bent Larsen and Viswanathan Anand, Monaco, 1992

(9997)

Before Cyrus Lakdawala’s Capablanca move by move is returned to the shelf, a passage from page 316 may be noted:

Faulty punctuation apart, a more scrupulous publisher than Everyman Chess would have made Mr Lakdawala either verify the matter or delete the paragraph. Readers deserve better than talk of an article ‘titled something like’ and ‘a quote which went something like’.

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) has kindly found the article, ‘Unlucky Heat Wave’. It was published not in Canadian Chess Chat Magazine but in Chess Canada, and not in 1972 but in August 1971 (pages 17-18).

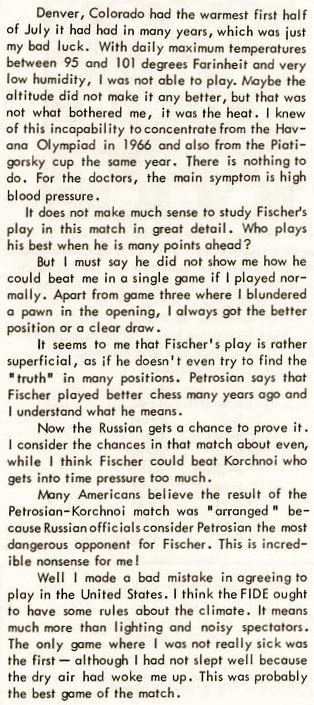

Larsen annotated the first game of his Candidates’ semi-final match against Fischer, and his opening paragraphs did indeed place heavy emphasis on the weather:

(10345)

From Paul H. Fields (Tampa, FL, USA):

‘For McFarland & Company, Inc. I am working on a book about Bent Larsen, and in particular his games with 1 b3 (Larsen’s Opening). Most were played between 1968 and 1975, and I am eager to obtain original photographs of him at these events: Monte Carlo, 1968; Lugano Olympiad, 1968; Palma de Mallorca, 1968; Busum, 1969; San Juan, 1969; Palma de Mallorca, 1969; Lugano, 1970; USSR v The Rest of the World match (Belgrade), 1970; Leiden, 1970; Siegen Olympiad, 1970; Vinkovci, 1970; Interzonal, Palma de Mallorca, 1970; European Team Championship, Aarhus, 1971; Palma de Mallorca, 1971; Teesside, 1972; Las Palmas, 1972; Hastings, 1972-73; Manila, 1975.

Games in which Larsen played 1 b3 in other events, including simultaneous exhibitions, are also sought.

I originally thought that Larsen v Benko in the fourth round of the Monte Carlo tournament on 6 April 1968 was the first time he played 1 b3, but in the database of the Dansk Skak Union I found Larsen v Knudsen in round two of the Copenhagen Championship on 15 February 1960. There are, of course, pre-1968 games by Larsen with 1 Nf3 and 2 b3.

As a sidelight, there is the comment by Krishna Prasad (Delhi Diary in the Outlook news magazine, 2 May 2016) that “Bent Larsen, the former world no. 3 in chess, has revealed that he would never wear a tie while playing because ‘less blood would get to his brain’.” Is it known where Larsen made that remark?

A regular column by Larsen in Kaissiber was titled “Ohne Krawatte”.’

We shall gladly forward to Mr Fields any messages from readers who can assist him.

(10828)

‘I do not especially recommend this opening.’

So wrote Bent Larsen about 1 b3 on page 138 of Chess Life, April 1969, in an article which has an early appearance of the name ‘Baby Orang-Utan’:

(11210)

Claes Løfgren (Fur, Denmark) provides a translation of part of a contribution by Bent Larsen, entitled ‘Thoughts about chess in Buenos Aires, Winter 1990’, to his old grammar school’s jubilee book:

‘“You should not stop while the game is good. It is far too good for that.” Quoted from memory from a book by Knud Lundberg. Lundberg is the closest I have come to having an idol. After a national match there was a dinner with mandatory tie, so he ate elsewhere. Generally, I am not very dependent on other people’s ideas, but at an impressionable age I had the experience of Lundberg strengthening me in my own opinion of these scraps of cloth, whose apparent purpose is to restrict the flow of blood to an important part of the body. But as I have little confidence in violent revolutions, I have yielded at times. A hotel in Reykjavik on a Saturday night. The Munich Opera, a tournament opening in Puerto Rico. Searching my memory thoroughly, I think of an Interzonal in Mallorca during which I was installed in a hotel where I could have no supper without putting on a tie. I put up with that because during a tournament you should not let yourself become excited by such matters, as it would ruin your concentration. I also wear a tie for certain concerts at the Teatro Colón. Perhaps I should take it off during the interval.’

Source: Aalborg Katedralskole 450 år (Aalborg, 1990), pages 146-147.

Our correspondent adds that Knud Lundberg (1920-2002) played football, handball and basketball for the national Danish teams, and later became a sports journalist and author. Mr Løfgren furthermore points out a photograph of Larsen receiving the Icelandic Order of the Falcon in November 2003.

(10835)

A photograph contributed by Olimpiu G. Urcan to our feature article William Hartston:

Hastings, January 1973 (Hulton Archive)

Concerning notation, there is a remark attributed to Bent Larsen to the effect that with a knight on KB1 a player who has castled on the king’s side is safe from a mating attack. What exactly did Larsen say or write?

(12112)

Ronald Young (Bronx, NY, USA) draws attention to Larsen’s notes, in algebraic notation, on his victory as Black over Karpov at Montreal, 1979 on pages 452-453 of Chess Life & Review, August 1979:

Position after 21 Re1-e4

Larsen played 21...Nf8 and wrote on page 453:

‘So that I do not get mated. With a knight on f8 you never get mated.’

(12186)

In his annotations to Karpov v Larsen, Montreal, 1979, the Dane wrote on page 453 of Chess Life & Review, August 1979 (C.N. 12186):

‘The bad bishop is out, but I insist it is still bad. “To play positional chess is to make a statement and then try to prove it”, said Nimzowitsch.’

Not recognizing the remark, we have consulted Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark), who responds:

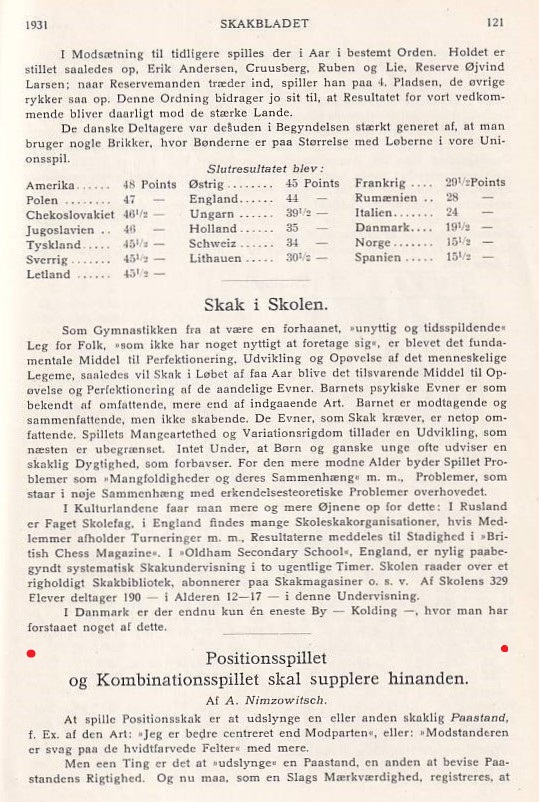

‘Nimzowitsch wrote an article in Skakbladet, August 1931, pages 121-124 under the title “Positionsspillet og Kombinationsspillet skal supplere hinanden”. Later, it found its way into Bjørn Nielsen’s book on Nimzowitsch (pages 433-437).

Bent Larsen’s quote is slightly different from what Nimzowitsch wrote but is essentially the same. My translation:

“Positional play and combinational play must complement each other.

Playing positional chess is to make a claim, such as “I am better in the centre than my opponent” or “the opponent is weak on the white squares”, etc.

But one thing is to make a claim, another is to prove its correctness.”’

The full article is available on the website of the Dansk Skak Union.

(12200)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.