Edward Winter

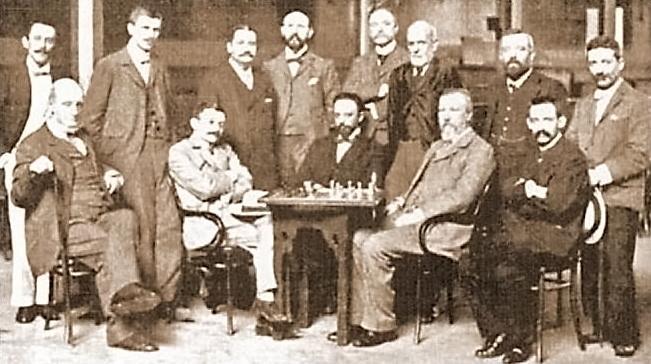

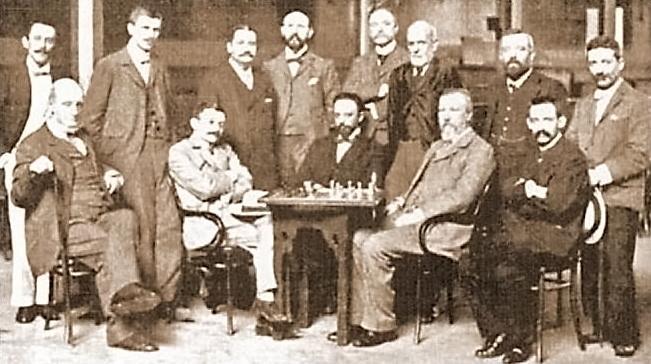

Photograph of some of the

participants, contributed by Pierre Bourget (Quebec, Canada) in

C.N. 5328. Our correspondent has proposed the following key:

Standing (from left to right: D. Janowsky, G. Maróczy, F.J. Lee,

L. Hoffer, J.W. Showalter, S. Tinsley, R. Teichmann and W. Cohn.

Seated: H.E. Bird, E. Lasker, M. Chigorin, J.H. Blackburne and

C. Schlechter.

Absent: J. Mason, H.N. Pillsbury and W. Steinitz.

In C.N. 5868 Joost van Winsen

(Silvolde, the Netherlands) suggested that the player identified

above

as Showalter was J. Walter Russell and that the figure named as

Teichmann was H.W. Trenchard.

The pen-portrait is a form of chess reporting that has fallen into desuetude (as has the word desuetude). Below is an excerpt from a description of London, 1899 on pages 210-213 of La Stratégie, 15 July 1899 (in our translation from the French). The writer is identified only as ‘André de M.’.

‘It would, I think, be difficult to imagine two men more completely dissimilar than Lasker and Janowsky. Nothing disturbs Lasker; his shirt, his clothes are the least of his worries. He is hungry; he goes to the sideboard and returns with a bread roll, which he eats with gusto while continuing his game. His legs are in his way; he puts them over one of the arms of his chair and continues to play, smoking strong cigars; when he reflects deeply he blows the smoke through his moustache with a characteristic grimace.

Janowsky, by contrast, is correctness personified. Seated before his board, he remains almost totally immobile. With a dazzling shirt, Turkish cigarettes, ice-cold lemon-squash, which he sucks through a straw, he is a refined, sensitive player par excellence, a sybaritic player who may lose merely because of a rose-leaf being crumpled.

Pillsbury is a slim young man with lively, intelligent eyes, and a pale, clean-shaven face which has a sad, resigned air, as if chess were an extremely painful task for him.

Maróczy, the young Hungarian master, is as thin as he is tall. He does not smoke; he does not drink; he plays with evident concentration of all his faculties. He has a particular manner of moving his shoulders around and staring at the board with extraordinary intensity. As regards his play, he has a kindly, persuasive way of pressing his opponent which is altogether unusual: he seems to insist that his opponent resign; when the latter is unwilling to be persuaded, the game is generally drawn. Maróczy has many draws in his total, as has Schlechter, who, in play, overhangs the board with the entire upper part of his body, with which he forms a perfect curve. He looks at the board at close range, and seems to be examining its every nook and cranny with the most painstaking attention.

British patriotism warmly welcomed the fact that Lasker’s sole defeat was at the hands of the old English champion Blackburne, who, during the tournament, also defeated Pillsbury twice. Blackburne is the epitome of the phlegmatic old Englishman, and it is clear, when one observes him, that although chess has its charms, there is also much pleasure and, when necessary, solace to be derived from a good pipe and a glass of whisky.

Dressed completely in black, very proper in his frock-coat, the Russian champion Chigorin seems, to the outsider, to be more like a committee member than one of the masters. He makes a habit of rising from his board to cast a critical eye over the other masters’ games, as if those games were of infinitely more interest to him than his own. Like Maróczy, Chigorin is one of the rare exceptions among the players in that he does not smoke.

Showalter has the head and hair of a Goliath. He has a way of putting his elbows on his knees and heavily rocking his powerful body, when he reflects, as if a combination demanded the expenditure of muscular force in equal measure to intellectual force.

Mason, who won ninth prize, played all his games seated the same way, with the same calm, the same stillness and the same disdainful, detached expression with which he looks at the board.

Cohn is a short young [sic] man, whose face takes on a sorrowful expression when his game does not go to his satisfaction. He played very well at the start of the tournament, but unfortunately he was unable to withstand the fatigue.

The admirers of the veteran Steinitz would have liked to see the old champion obtain a better result than the one he achieved. Even so, his lack of success seems not to have disturbed him too much. On his table Steinitz always had a carafe of pure water, from which he drank large glassfuls while smoking his cigar, which, absent-mindedly, he generally set down, still alight, on the green baize covering the table.

Lee was able to take defeat with a smile on his lips, but the same could not be said of the elderly Bird; it was truly painful to see him dragging himself to his board, leaning on a cane and bent double under the weight of years and gout.

Tinsley, for his part, has the great failing of talking and gesticulating during his games, which is far from always being appreciated by his opponents. It is certain that this had a great influence over the defeat he inflicted upon Chigorin on the final day of the tournament, thereby making him lose sixth prize. On another day, playing against Maróczy, Tinsley provoked general amusement, after a winning move from his opponent, by suddenly stretching out his arm over the board and threatening his impassive victor with a closed fist. In his second meeting with Pillsbury, after resigning, Tinsley made a success for himself by feeling obliged to add, “It is well for a young man”.’

The writer was unimpressed by the playing conditions: ‘I think it would have been difficult to find premises more shabby, more grubby and more unhealthy than St Stephen’s Hall.’

The Royal Aquarium, the venue for London, 1899 (Chess Pie, 1922, page 18)

(2637)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides eight sketches published in the Pall Mall Gazette, 14 July 1899:

(5729)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.