Edward Winter

The 1922 international tournament in London was won by Capablanca ahead of Alekhine, Vidmar and Rubinstein. The Cuban’s round-by-round reports in The Times were reproduced on pages 139-151 of our 1989 monograph on the Cuban. See also Capablanca on London, 1922.

The location was the Central Hall, Westminster:

Chess Pie, 1922, page 19

On pages 360-361 of the September 1922 Chess Amateur T.R. Dawson recorded his impressions of a visit to the London Congress. He raises some interesting points about ‘actual play versus problems’:

‘Never having visited a chess congress before, I went with an open mind, prepared for anything I found it. Chess congresses, I soon learned, are not really for chess, but only for chess play. There is, however, a social side of the congress which is pleasantly good – saying “How d’you do?” to folk you have exchanged letters with for years and never previously met is rather exciting.

My day there covered the fifth round of the principal tournament and supplied a variety of incidents more or less worth mentioning. The first hour or so of play was exceedingly dull. Only the most ardent enthusiastic students of the openings can find interest in the solid, stolid, first 15 moves or so of these master games. The three deep serried ranks round the Capablanca board indicated, indeed, that a caissic hero was more attractive than mere openings. During this period I wandered about, a disconsolate lost problemist, seeking distractions. Not being able to pursue my acquaintance with Wahltuch, Watson and Yates beyond nods, during their serious struggles over the board, I was glad to light upon our genial problem editor [C.S. Kipping] and Dr Schumer. The latter gave me some amusing reflections, for referring to my predilection for the humorous and fantastic, Dr Schumer waved his hand towards the players with the comment: “This is serious chess, of course”. I admit the “serious”, but beg to doubt the “of course”. I idly reflected that these masters put in some four or six hours’ strenuous thought over one game – and it is strenuous all right, some of them being obviously tired out by the end of the day. But we problemists think nothing of 20, 40, a hundred strenuous hours over one solitary problem. There are two of my retro problems [which] cost me six years of intermittent work – at a guess, a thousand hours – to complete, and I have a score of others over which I have worked ten years, and they are still baffling me. This, “of course”, is not serious chess, I presume.

The first mild excitement of the day developed over the Marotti-Yates game. The Italian player, apparently somewhat outclassed in this tourney, made a wretched move that lost a pawn and the exchange, and resigned forthwith. The game might have been very interesting otherwise, as it exhibited a definite strategic structure. Yates was meeting a promising attack on his K-side castled king by a vigorous counter-attack on a Q-side castled king and the pieces being so distinctly orientated, a rare race for the first telling blow seemed due.

Somewhen about this time the thickening of the crowd round the Morrison-Euwe board indicated happenings, and the well-known player and problemist, Mr F.F.L. Alexander and myself were perched on chairs at the back of the crush getting occasional glimpses of the board. As no move transpired for ten minutes or more, Alexander and I immersed ourselves in a pocket board and problem lore, oblivious of crowds, game or our own precarious elevation. The absurdity of standing on chairs to do problems, instead of sitting, occurred to me only when running over the day’s events for this paper.’

After quoting a few episodes from the play, Dawson concluded:

‘The other games in the round, which I have not mentioned, were all too dull to excite comment. I came away from my first day at a congress very glad that I was not a professional reporter of such doings.’

(1597)

The picture below appeared opposite page 216 of Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca” by José A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923):

If chess literature is to feature anecdotes, let them at least have a point. One story, set during the London, 1922 tournament, which has some purpose was related by David Hooper in the Capablanca entry of Anne Sunnucks’ Encyclopaedia of Chess:

‘These two rivals [Capablanca and Alekhine] were taken to a variety show by a patron, Mr Ogle, who recalled that Capablanca never took his eyes off the chorus, whilst Alekhine never looked up from his pocket chess set.’

In the first edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess (the Alekhine entry) the patron was named in full as Christopher Ogle, and in at least one other modern outlet he has been described as a ‘chess patron’. That remains to be demonstrated, but our particular interest is in knowing the source of the Ogle/ogling recollection and whether there are further reminiscences from London, 1922.

(3083)

This advertisement is on an inside cover page of the October 1956 BCM. Does any reader have a copy of the Hollings catalogue?

(6960)

From page 384 of the September 1922 Chess Amateur, concerning London, 1922:

‘The International Congress concluded with the prize-giving meeting on Saturday, 19 August, over which Canon Gordon Ross (President of the British Chess Federation) presided, supported by Major Barnett MP, Mr L.P. Rees, Mr R.H. Stevenson and Mr Christopher Ogle.’

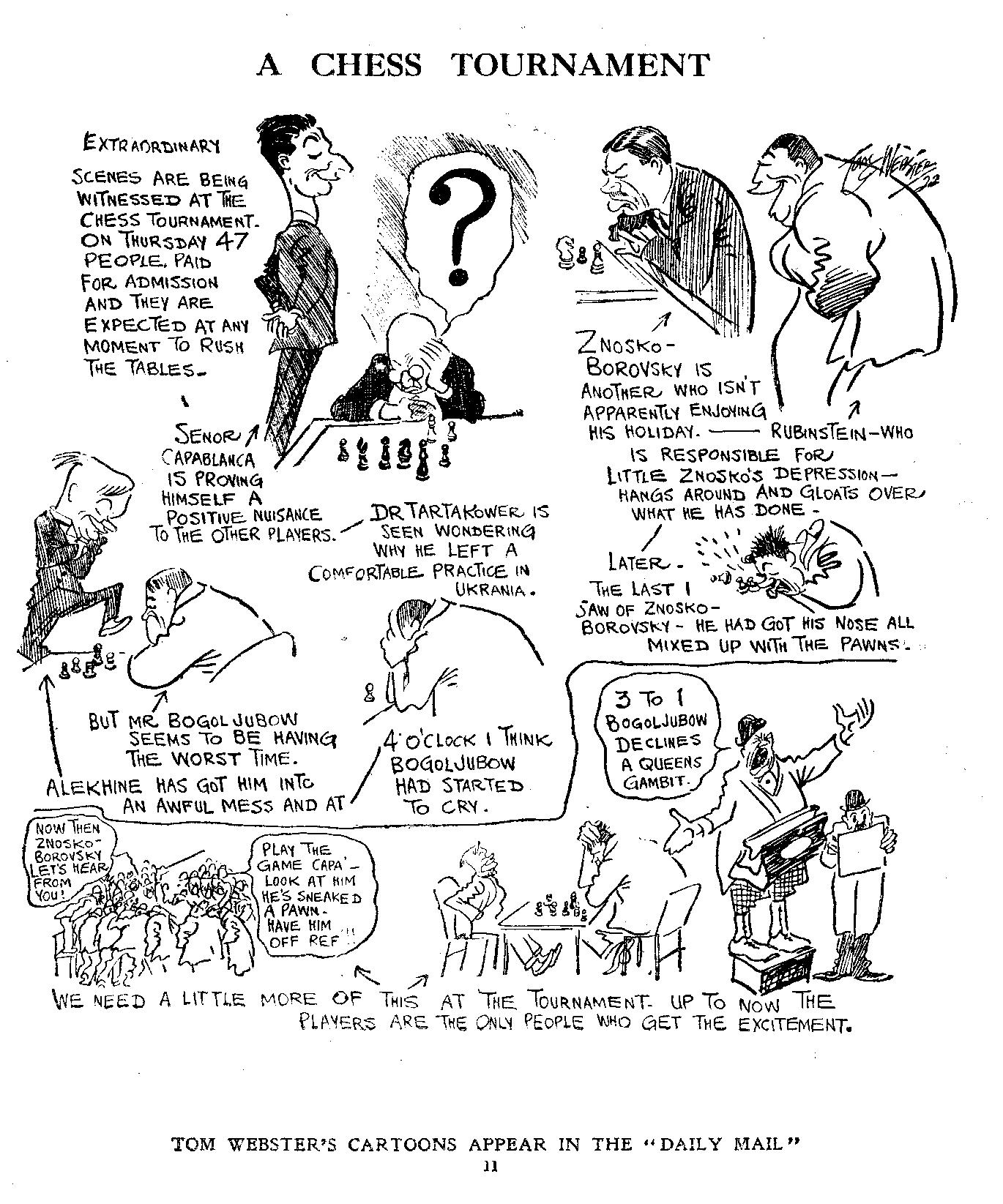

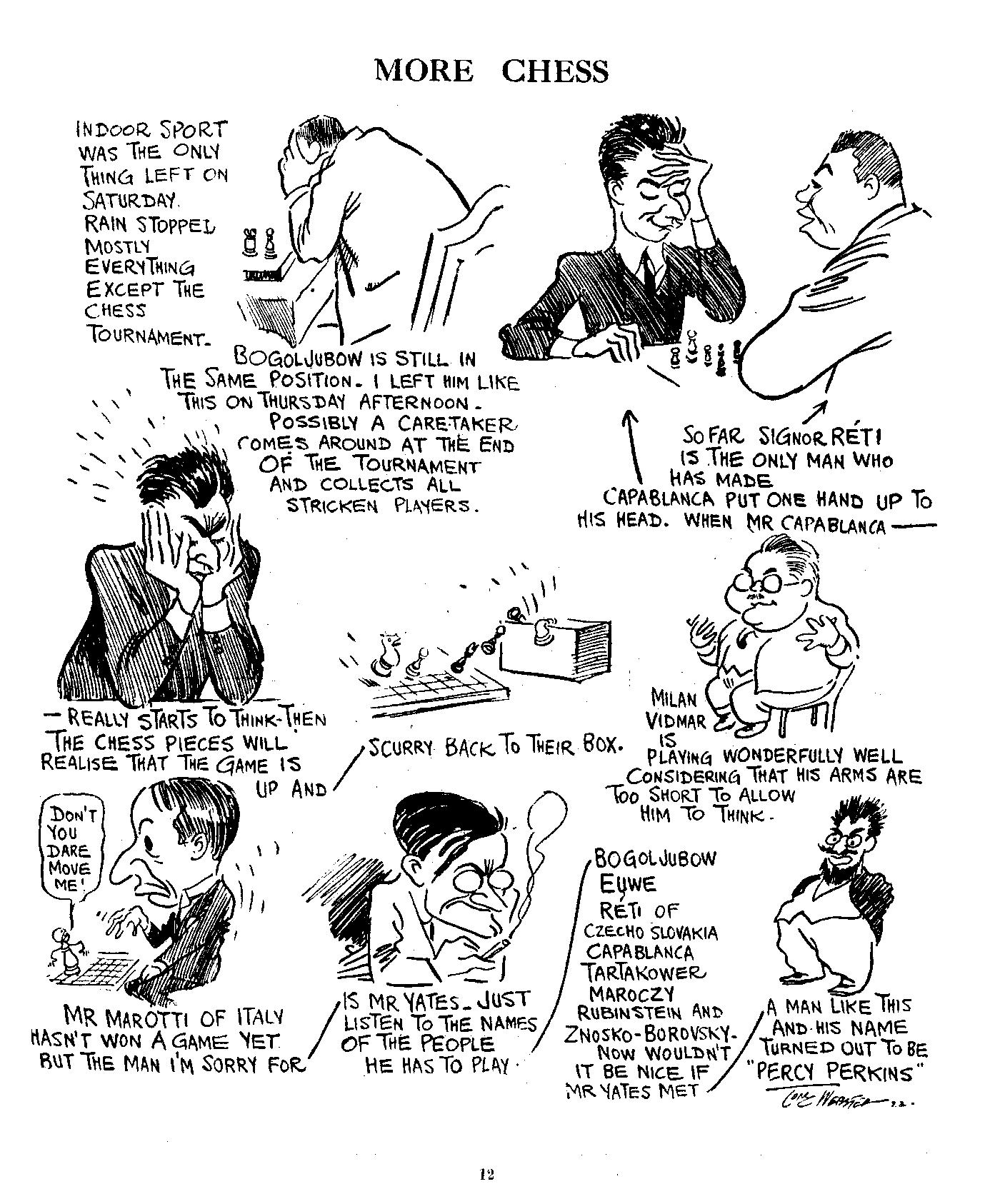

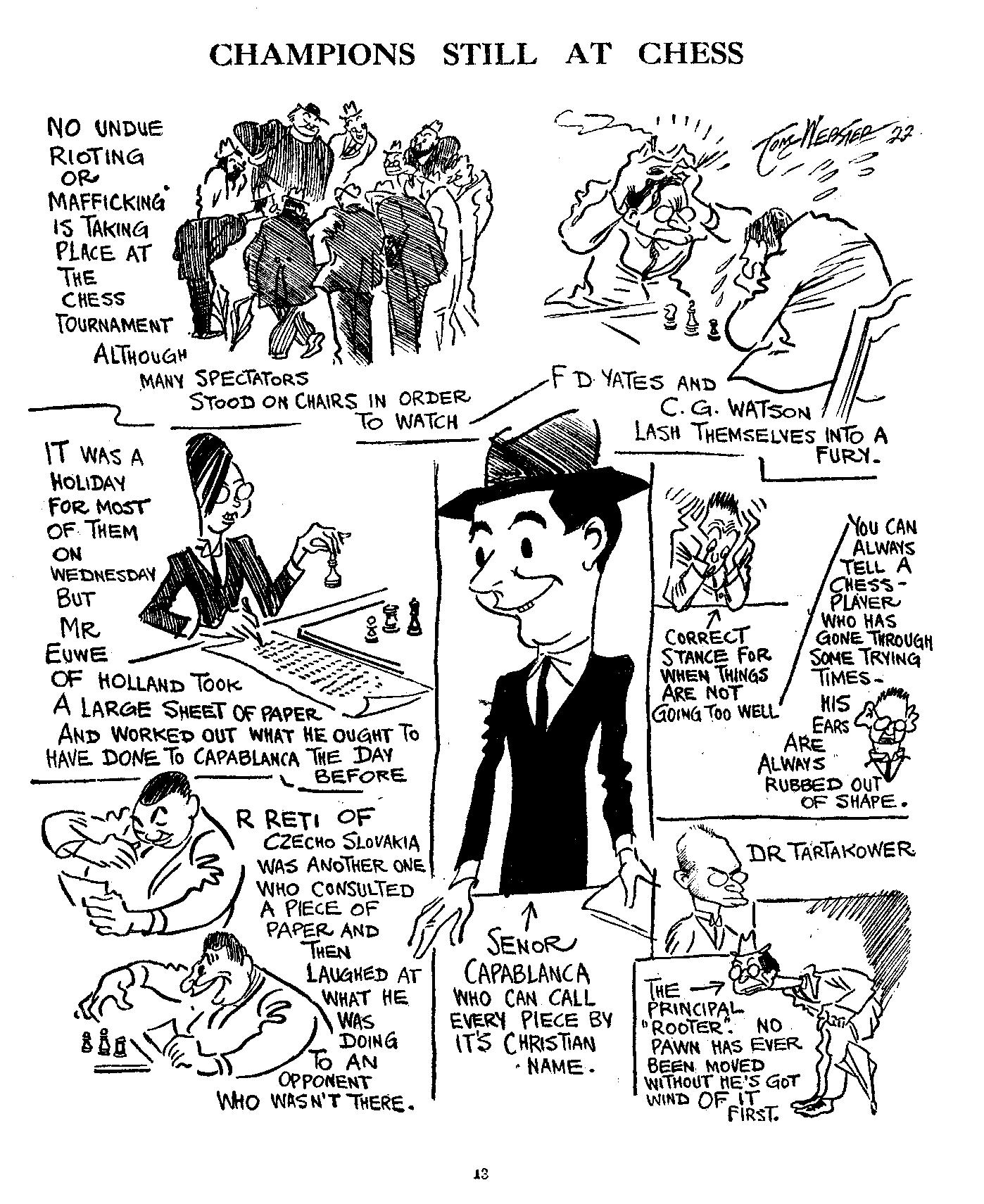

From Eric Fisher (Hull, England) come three cartoons marking the London, 1922 tournament. They were published on pages 11-13 of Tom Webster’s Annual 1923 (London, 1923).

(3938)

Concerning the cartoons from Tom Webster’s Annual 1923 which were shown in C.N. 3938, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides information on their prior appearance in the Daily Mail: 11 August 1922, page 9; 14 August 1922, page 9; 3 August 1922, page 9.

He adds that this detail from the 14 August cartoon was published on page 9 of the Daily Mail, 19 August 1922:

(7372)

It is surprising that Julius du Mont, who knew the Cuban quite well, made so many factual errors in his memoir in Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1947). A list compiled by us was made available in C.N. 3767, and here we revert to a puzzling case concerning Capablanca and Vidmar. As is well known, on page 17 du Mont wrote about Capablanca:

‘I remember his winning a brilliant game from Dr Vidmar in London, 1922, and laughingly patting the loser on the back, saying: “He always give [sic] me a chance of a brilliancy: he is my meat” – this accompanied by such a charming and good-natured smile that everyone, including Dr Vidmar, had the impression that he had bestowed the finest compliment on his opponent. Who else could make such a remark to his adversary and convey the feeling of the utmost friendliness?’

We quoted this on pages 317-318 of our book on Capablanca and commented:

‘The story cannot be correct, as before London, 1922 Capablanca and Vidmar had met only once, drawing in 20 moves.’

(4566)

An extract from Aleksander Kostyev’s From Beginner to Expert in 40 Lessons (page 79):

‘During the London International Tournament of 1922, Grandmaster M. Vidmar adjourned his game against Capablanca in a lost position. The time came to resume the game. Convinced that there was no point in continuing the game, Vidmar awaited his opponent with the intention of resigning. Time passed, but Capablanca didn’t appear – some unforeseen circumstance had detained him. Looking at his clock Vidmar suddenly realized that his opponent’s flag was about to fall. Capablanca was on the point of losing and he, Vidmar, would gain a formal victory. Not hesitating for an instant, the Yugoslav grandmaster rushed up to the board and just had time to resign the game by knocking his king over a moment before the controller would have declared him the winner on time. The British press dubbed Vidmar’s action “the most beautiful move ever played in a chess game”.’

Before the sentimentalists perpetuate the story, it would be interesting to know its source. Certainly it is not mentioned in the Times’ daily report (17 August 1922). Another unfortunate fact: the game was never adjourned.

(986)

Bernard Cafferty (Hastings, England) writes:

‘The story about Capa not turning up, because he thought Vidmar had indicated he was resigning (an error probably due to a misunderstanding in the use of French, according to Vidmar) is told in some detail on pages 134-6 of Vidmar’s Goldene Schachzeiten.’

(1025)

A further example of how fanciful anecdotes appear in different guises. The 8/1968 issue of the Cuban magazine Jaque Mate, page 22, has an entirely transformed version, placed 14 years later than London, 1922:

‘The most elegant move. Nottingham Tournament, Round X, 21 August. Vidmar-Capablanca. After playing his 36th move, Vidmar felt ill and asked for permission to postpone the game. Capablanca agreed. The Cuban, who had a won game, showed Vidmar the move he was going to seal, asking him whether he would play on after seeing it. Vidmar replied in the affirmative, and the Director of the Tournament fixed the day when the game would continue. On the selected date Capablanca did not turn up for play, owing to previously made social engagements. When only a few seconds were left before the regulation time-limit had passed, Vidmar, seeing that Capablanca was not there, turned over his king and resigned. Without doubt an elegant move!’

In C.N. 986 we pointed out that Capablanca-Vidmar, London 1922 was never adjourned. The same applies to Vidmar-Capablanca, Nottingham 1936, which lasted only 30 moves (the time-limit was 36 moves in two hours). The start of the latter game was postponed on account of Vidmar’s indisposition.

(1208)

Bernard Cafferty has sent us a copy of pages 308-309 of Vidmar’s 1951 book, published in Ljubljana, Pol stoletja ob šahovnici, which states that play (at 20 moves per hour) was from 14.00 to 18.00, after which there was an adjournment until 20.00. Mr Cafferty comments:

‘This appears to reinforce Vidmar’s claim that his 1922 London tournament game with Capablanca was adjourned and the latter’s clock set in motion in the evening adjournment session. This is at variance with C.N. 986, reiterated in C.N. 1208. The question is, I suppose, whether Vidmar’s memory was at fault, or whether the correspondent of The Times missed the incident, possibly because it was too late for his deadline, or he did not attend the evening session for adjournments, or he relied on Capablanca’s impression that Vidmar had resigned after sealing his move.’

We can add that The Times of 17 August 1922 (page 9) contains Capablanca’s report on this game and the rest of the day’s play. It also gives a chart of these 13th-round results. Only one game is listed as having been adjourned: Znosko-Borovsky v Atkins (which lasted 85 moves in all). The Times was, however, able to include the result of Wahltuch v Euwe, which went to 54, and this makes it clear that the newspaper used the word ‘adjourned’ only when play was suspended a second time (i.e. at the end of the session that began at 20.00). Consequently, it cannot after all be ruled out that the Capablanca v Vidmar game was broken off between 18.00 and 20.00.

One final discrepancy: Capablanca writes that ‘finally on the 42nd move Dr Vidmar resigned’, but on the same page, The Times’s score of the game states that Black resigned after playing 42...Kf7. Other sources (including Capablanca’s A Primer of Chess, page 229) give no 42nd move by Black, but just 42 Rb8+ Resigns.

(1474)

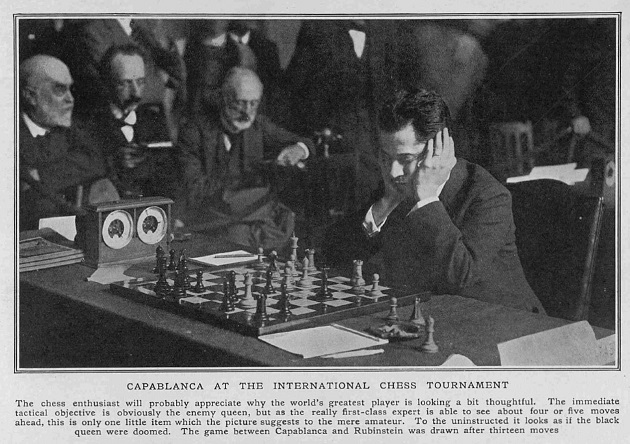

Below is one of many photographs provided by Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) in C.N. 10362, showing Capablanca in play against Vidmar (not Rubinstein):

The Tatler, 23 August 1922, page 285

A common piece of chess ‘wisdom’ is that good moves are pleasing on the eye, but when was this view first expressed? We note that it appeared on page 445 of Tarrasch’s Das Schachspiel (Berlin, 1931), concerning White’s opening play in Alekhine v Yates, London, 1922:

‘Die wirklich guten Züge sind auch fast immer, ich möchte sagen, ästhetisch schön.’

The English edition (page 359 of The Game of Chess) stated:

‘Really good moves are almost always, I might say, aesthetically pleasing.’

(6344)

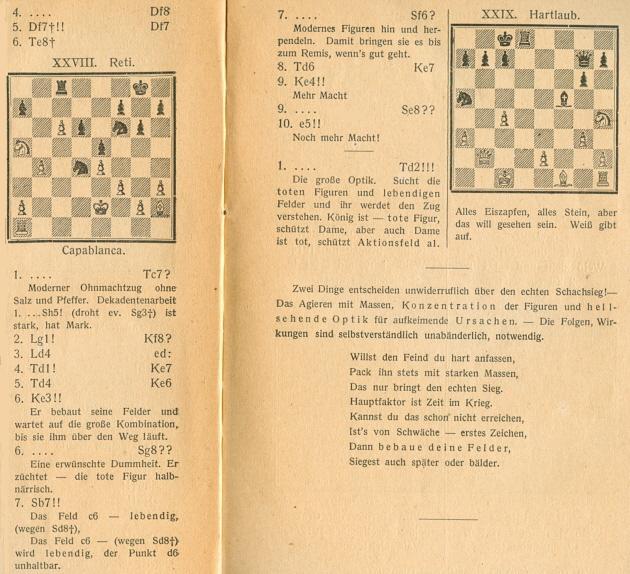

From Hypermodern Chess:

It is not always clear who should be regarded as a hypermodern player. C.N. 653 mentioned the case of Efim Bogoljubow, pointing out that on page 106 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942) Reinfeld described Capablanca v Bogoljubow, London, 1922 as the Cuban’s ‘first encounter with an outstanding Hypermodern master’. However, we added that a random check of tournament books of some of Bogoljubow’s greatest triumphs in the 1920s indicated that his opening play was extremely classical, with barely an Indian Defence, Réti Opening, etc. in sight.

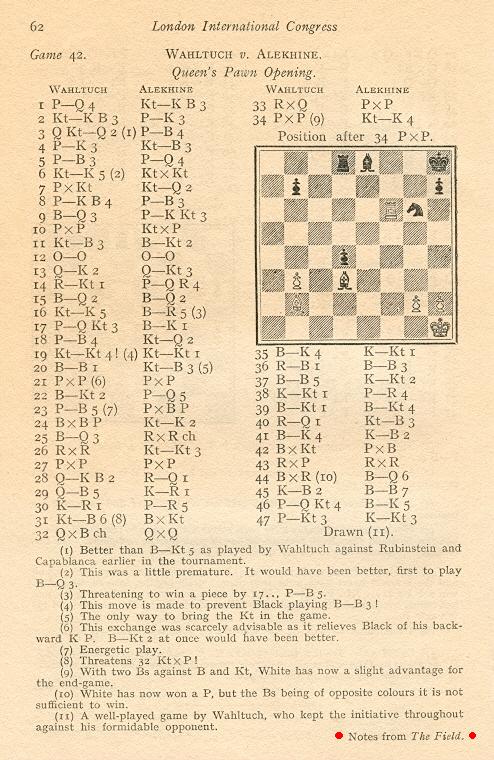

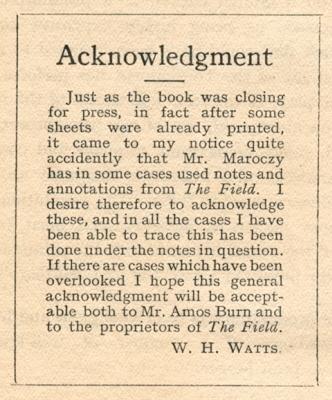

A serious disservice is done to chess history by some ‘modern’ editions of old tournament books. The latest example is London 1922 by G. Maróczy (Milford, 2010), which not only discards the original book’s introductory material but brushes out the editor and publisher, W.H. Watts, and a master, Amos Burn, who annotated at least 18 of the games.

In the original edition, games featuring Burn’s annotations (games 41-44, for example) ended with the specific reference ‘Notes from The Field’:

On page 5 of the original edition Watts gave an explanation indicating that the total number of games annotated by Burn, as opposed to Maróczy, might well be even higher than 18:

(6732)

From Gaffes by Chess Publishers and Authors:

Sometimes a publisher offers variety. International Chess Congress, London 1922 edited by David Regis (Aylesbeare, 2006) had E.R. Tinsley on the front cover, E.H. Tinsley on the title page and (accuracy at last) E.S. Tinsley in the Foreword.

A paragraph about Euwe by Walter Meiden on page 21 of the April 1982 Chess Life:

‘He was modest and unassuming; he tried to look at things from an unbiased point of view. He insisted on including in The Road to Chess Mastery, which had only master vs amateur games, one that he had lost to Capablanca – Game 7. “I played like an amateur in that game”, he said, and he showed in his marvelously clear way just how Capablanca won.’

The game was played at London, 1922.

(6867)

Below is an example of Franz Gutmayer’s output, from pages 20-21 of his book Der fertige Schach-Praktiker (Leipzig, 1923):

In the Capablanca v Réti game (London, 1922) neither player overlooked that the Cuban’s king was in check. It was on e1, and the white rook was on c1, not a1. Black had a pawn on b5.

(7392)

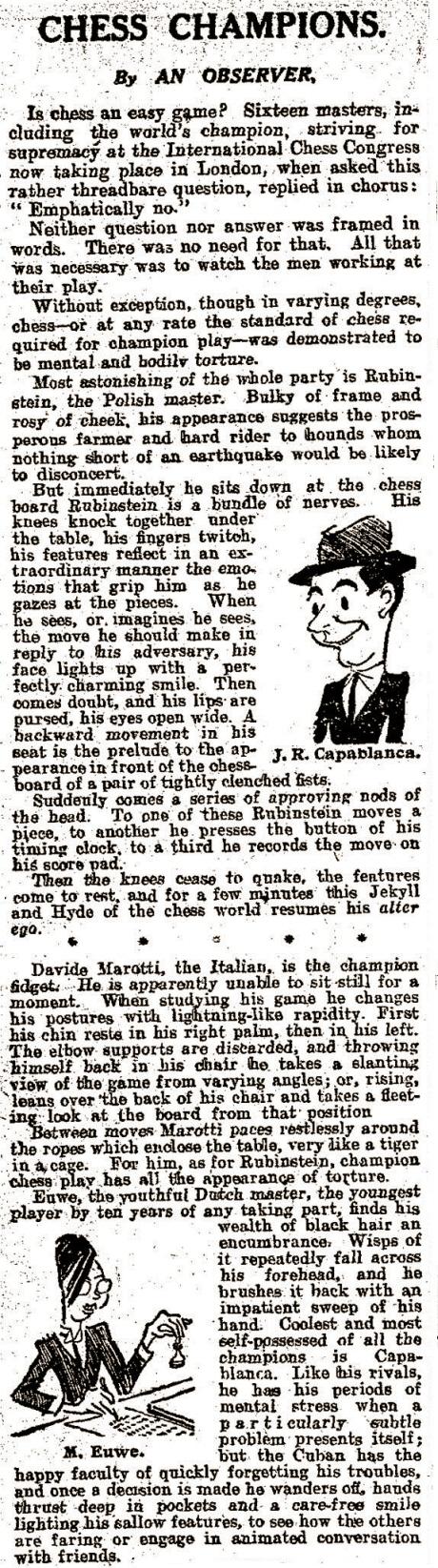

Olimpiu G. Urcan sends the following:

Daily Mail, 7 August 1922, page 6

(8193)

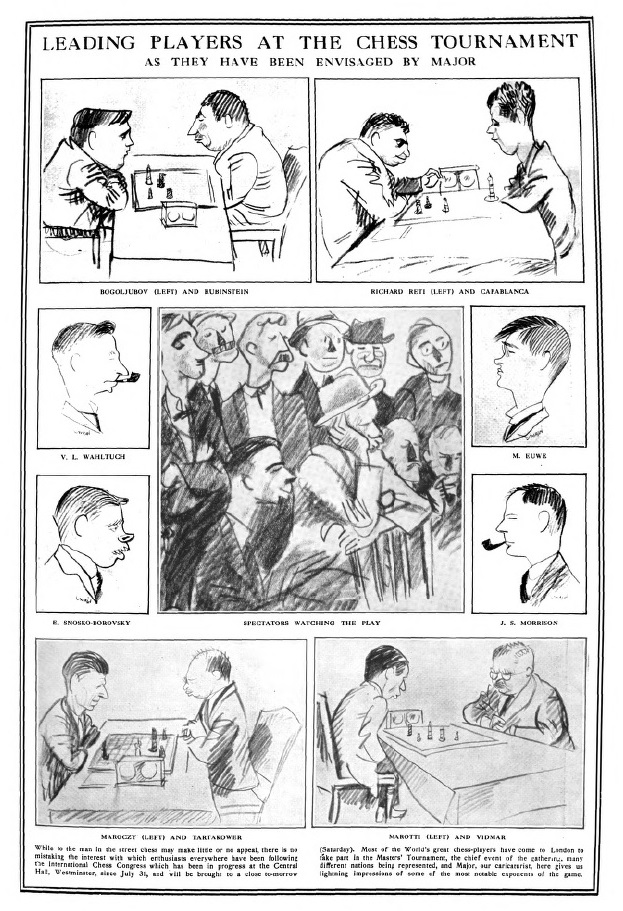

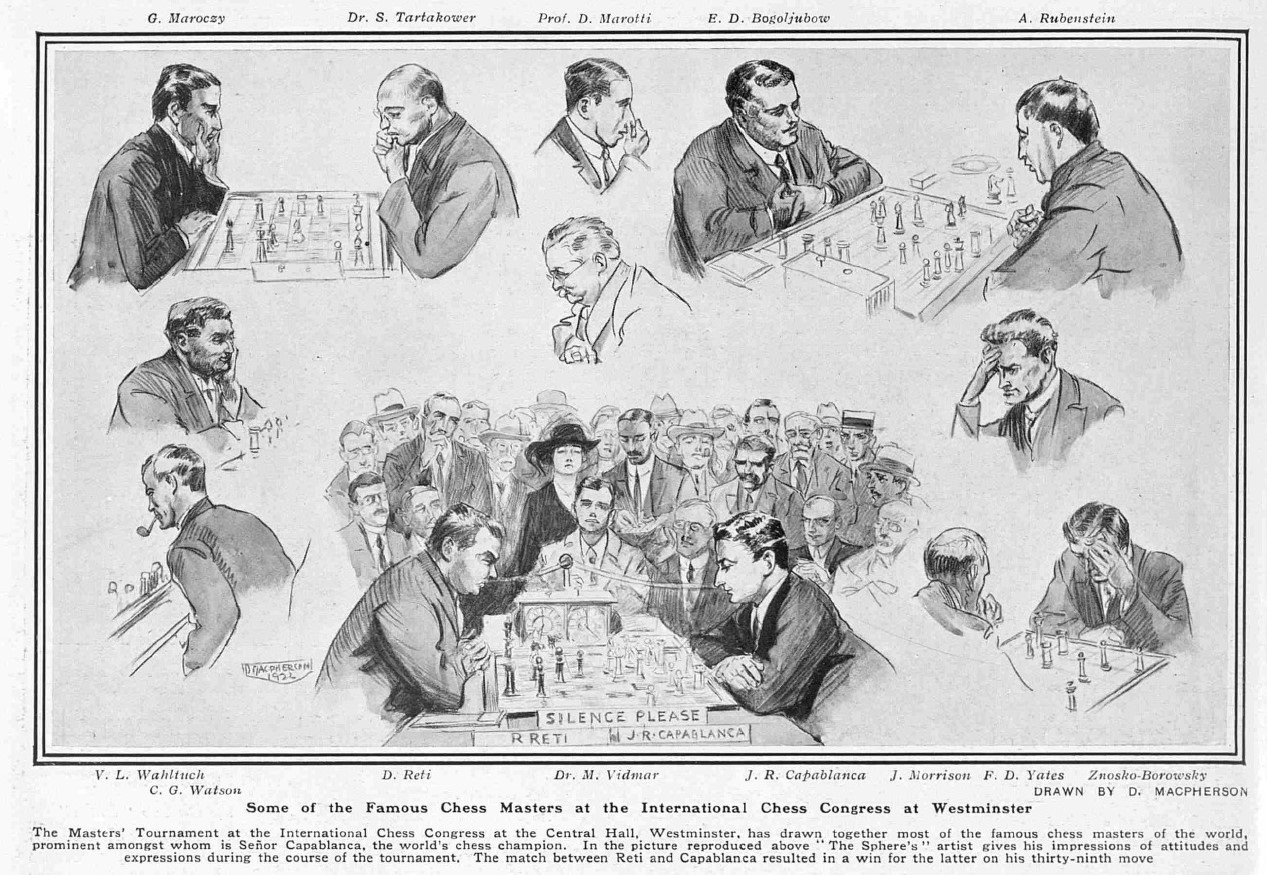

Gerard Killoran provides a set of caricatures on page 261 of The Graphic, 19 August 1922:

(8982)

Ivor Goodman (Stevenage, England) asks about the move order in Tartakower v Atkins, London, 1922. He points out that after 34 Kc2 ...

... databases have the continuation 34...Ra2+ 35 Kc3 Rc8+ 36 Bc6 Rxc6+ 37 Rxc6 Qb4+, whereas 34...Rc8+ 35 Bc6 Rxc6+ 36 Rxc6 Ra2+ 37 Kc3 Qb4+ is given on pages 106-107 of H.E. Atkins Doyen of British Chess Champions by R.N. Coles (London, 1952).

The game was widely published at the time, e.g. in the BCM, Chess Amateur and (with Brian Harley’s notes from page 4 of the Observer, 13 August 1922) American Chess Bulletin. It is in the London, 1922 tournament book by Maróczy with Amos Burn’s annotations from The Field, and it was later anthologized in A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld (London, 1950) and 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952). In all of these publications the move order was 34...Ra2+ 35 Kc3 Rc8+ 36 Bc6 Rxc6+ 37 Rxc6 Qb4+.

Capablanca did not mention the game in his report on the ninth round of the London tournament on page 14 of The Times, 12 August 1922, but the same page had this paragraph ‘by our chess correspondent’:

‘The game between Tartakower and Atkins was the first example of this opening in the tournament, Atkins playing the KtxP variation on his fourth move. The middlegame was even. Tartakower castled on the queen’s side with a view to a king’s-side attack. Mr Atkins countered by an attack on the queen’s side, but again got short of time. However, he seemed to play all the better for it, for with only about 14 minutes to make as many moves he drove Tartakower’s king all over the board by a series of checks, and finally mated him on the 42nd move.’

(9070)

As noted in The Best Chess Games, Tartakower wrote on pages 241-244 of CHESS, 14 March 1939 that his draw against Capablanca at London, 1922 was ‘the most terribly pulse-stirring flight [sic] of my whole chess career’.

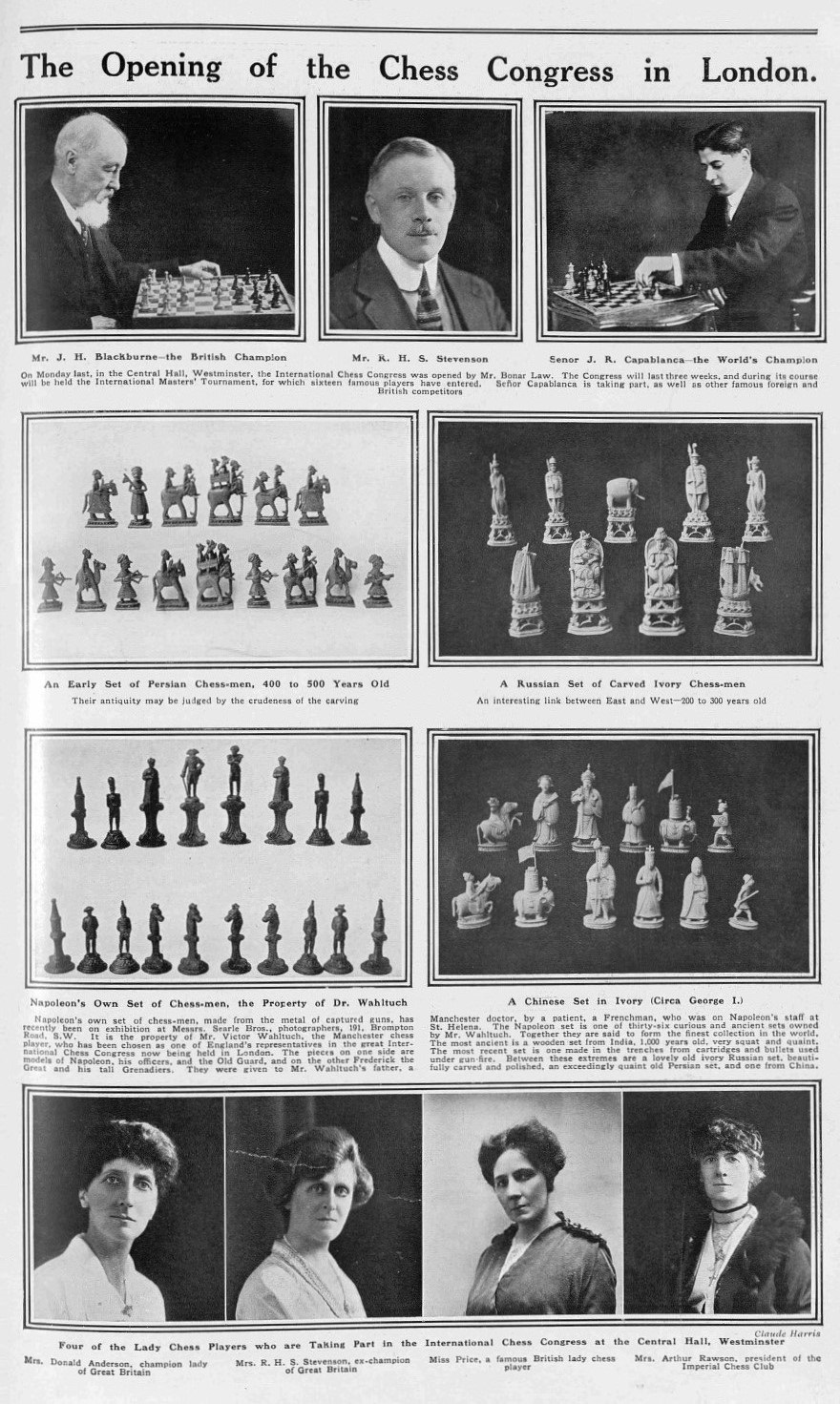

The feature article Chess Pictures in The Sphere includes the following, provided by Olimpiu G. Urcan:

5 August 1922, page 137

19 August 1922, page 186

An article entitled ‘Watson the Unique’ by C.J.S. Purdy in the 1 November 1949 issue of Chess World had the following on pages 252-253 regarding London, 1922:

‘Then Watson went to London. It meant crashing into a field which included Capablanca, Alekhine, Vidmar, Rubinstein, Bogoljubow, Réti, Tartakower, Maróczy, Euwe and Co. It’s our firm belief that Watson, bred in the same environment as any of these, would have become a grandmaster himself – but when one considers that before this event he had competed in only one round-a-day tournament in his life, and in his whole 42 years had barely that number of match games against players of his own strength, his score of 4½ out of 15 in that field emerges as something of a miracle. It included four outright wins, the same number that was achieved by Euwe and Znosko-Borovsky. He scored 1½ out of 2 against Britain’s two greatest players, Yates and Atkins, and defeated Réti. He also made a great fight against Vidmar (winner of third prize below Capablanca and Alekhine) and, under time-pressure, missed a forced win against Maróczy.’

(10093)

From page 9 of the Rockford Morning Star (Rockford, IL, USA), 3 August 1922, in a feature by Archie Ward:

(10887)

Can an authoritative explanation be found, or put together, concerning Emanuel Lasker’s absence from London, 1922?

(11277)

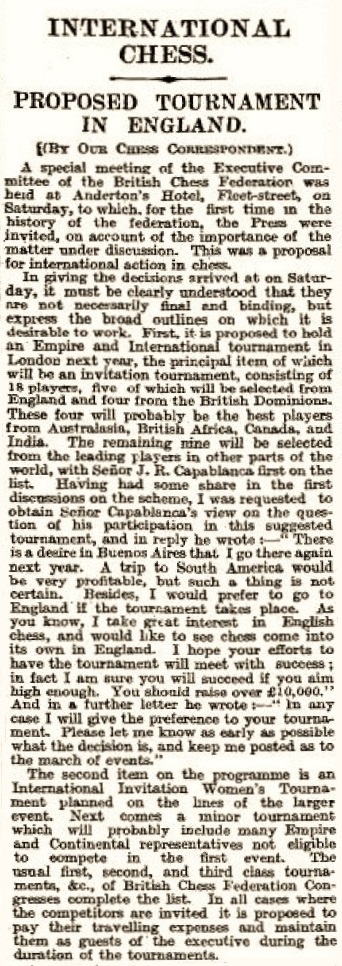

Plans to hold an international tournament in London were reported on page 12 of The Times, 19 September 1921:

A similar account was on page 362 of the October 1921 BCM:

A tentative list of participants was published on page 195 of the Chess Amateur, April 1922:

From page 258 of the June 1922 edition:

Neither V.K. Khadilkar nor B. Kostić participated. Regarding the former, page 14 of The Times, 31 July 1922 reported:

‘Znosko-Borovsky takes the place of the Indian Champion, V. Khadilkar, who found himself unable to make the journey to England.’

The name of J.S. Morrison of Canada was added in a report on page 5 of The Times, 26 June 1922:

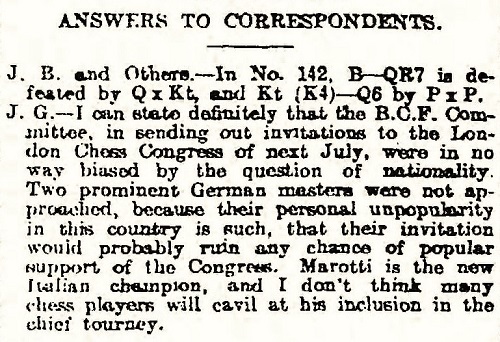

Most British reporters wrote about the tournament as if German chess did not exist, although two BCM issues in 1922 carried reports in the ‘Colonial and Foreign News’ section, under the heading ‘Germany’, about Lasker’s non-participation in London, 1922:

July 1922, page 273:

‘In connection with the proposed quadrangular tournament in Hastings between Capablanca, Lasker, Alekhine and Rubinstein, the Deutsches Wochenschach remarks that in Hastings they appear to be more open-minded than in Chauvinistic London! The DW does not propose to report the London tournament.’

August 1922, page 307:

‘The Deutsches Wochenschach has reconsidered its decision not to report the London Congress, influenced by the fact of the invitation of Dr Lasker to Hastings, which, our contemporary says, shows that the exclusion of German masters from the London Congress is a mistake for which the whole of England must not be held responsible.’

It will be borne in mind that after Lasker wrote a series of nationalistic/patriotic/jingoistic articles about the Great War in the Vossische Zeitung from 16 August to 25 October 1914, he was strongly criticized in England, and especially in the Chess Amateur. See C.N. 3272, reproduced on page 211 of Chess Facts and Fables.

Pages 277-279 of the April-June 1927 Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten reproduced a statement by Lasker from the Essener Zeitung of 21 December 1926. His explanation as to why he would not be participating in New York, 1927 included the following about his absence from London, 1922 (and Hastings, 1922):

Another version of such remarks by Lasker was given on page 195 of our book on Capablanca.

In an endnote on pages 319-320 we quoted from Brian Harley’s column on page 19 of the Observer, 26 March 1922:

On page 8 of the 23 July 1922 edition of the Observer, in a column by Harley entitled ‘Capablanca and his rivals’, there was a rare reference to Lasker by name in connection with London, 1922:

‘In the Masters’ Tourney we have the world champion, Capablanca, most of the other great foreign experts (with Lasker a conspicuous exception) and six representatives of the British Empire.’

Further details are still sought concerning the basis on which invitations to London, 1922 were, or were not, extended, and especially with regard to Lasker and Tarrasch.

(11284)

See too the references to London, 1922 in Lasker Speaks Out (1926) by Richard Forster.

Addition on 16 January 2022:

Olimpiu G. Urcan provides this photograph of Tartakower and Rubinstein, courtesy of the Central News Photographic Archive:

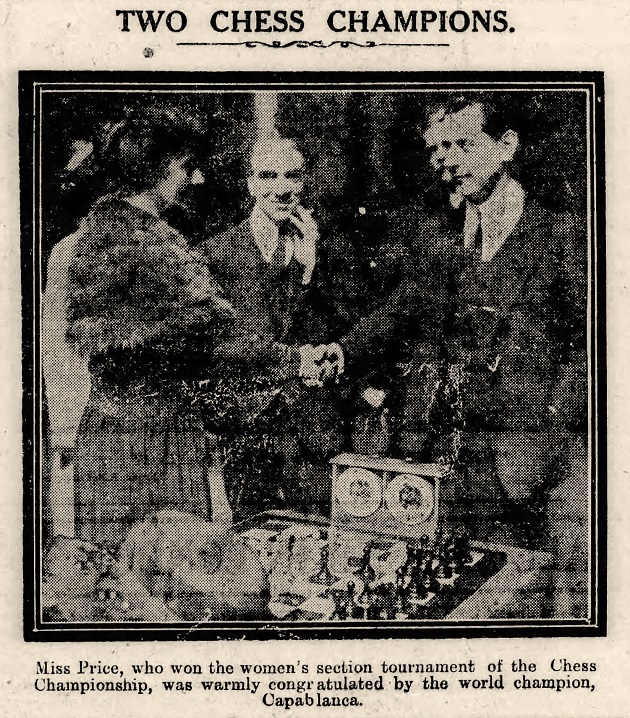

Photographs of Capablanca shows many interesting pictures from Soviet publications for which no good copy has yet been traced. The same frustration arises in numerous other cases, such as the shot below which Olimpiu G. Urcan found on page 3 of the Liverpool Evening Express, 21 August 1922, i.e. shortly after the conclusion of the London Congress:

(11968)

‘The Funny Side of Things’ was the heading of an article by John Brett on page 2 of the Blackpool Times, 22 September 1922, i.e. after the London tournament:

‘The Chess Tournament is over, and a weight has been removed from my mind. I wish to add that I was not one of the masters who took part in that tournament. I am not Tarasov in disguise. My name in private life is not Boguljubov; in fact, I don’t even know how to pronounce it.

But while the tournament was at its height I felt like a hunted man. No criminal ever slunk or slank (I am not very sure how this verb goes) with a greater feeling of slinkiness than did I while Capablanca and the rest of them sat day after day gazing at the boards and the men thereon, playing chess briskly at the rate of about one move every other day.

It was not that in this life one cannot help meeting chess players every day. It was not merely that during the tournament their chess disease rose to fever point, so that in train and cafe it was impossible to escape the heated argument as to whether Euwe might have won on his ninetieth move if he had played pawn to king’s fifth instead of king to pawn’s fifth on his thirtieth move. No: it certainly couldn’t have been that, because now I come to think of it I don’t believe there is such a thing as pawn’s fifth. Why there is not must always be a mystery, I suppose, to one who has never yet mastered the intricacies of the knight’s move, or found out why it should be regarded by chess players as so heinous a crime to call a rook by the apparently very appropriate name of “castle”. After all, the beastly thing looks like a castle, and certainly doesn’t look like a rook.

No: it has not been the continued arguments about this or that move in this or that game which have worried me. They have distressed me, it is true, but that has been because they have served to keep reminding me of the awful fate which I felt was awaiting me. If I had suddenly been told that I was to play Capablanca in the final round I think I would have been resigned to my fate: I could always resign the game. I would have taken on even those players with the Bolshie names providing it was understood from the start that we had met for chess only, and that we were not to play the slightly more easy game of “beaver”.

No: I would not funk being suddenly told that the fate of the British Empire was in the balance and depended upon my joining in the chess tournament. It is true that I do not play the game myself, but at the rate at which it is played in tournaments I think that I would have had time to learn how to play while my opponent was making his opening move; or if I had won the toss I could have given a miss in baulk, or layed my opponent a stymie, or something, while I looked up the rules. After all, a chess board is no bigger than a draughts board, and I have a sneaking suspicion that so long as you watch your chess opponent carefully, and take off one of his men whenever he takes off one of yours, the game is certain to end in a draw.

But what I have been fearing, and now that the tournament is over this awful thought is removed, was that while the tournament was on the Editor might suddenly demand that I write something humorous about chess.’

There is a weary tradition of such articles, the conceit being that a relative nobody with scant knowledge of chess poses as a relative somebody who knows even less. Draughts and bridge contests seem to be spared similar treatment.

The spelling ‘Boguljubov’ in the first paragraph is the newspaper’s. Tarasov, also mentioned there, had nothing to do with London, 1922, but his loss to Capablanca in a 103-board display in Cleveland on 4 February 1922 had been widely published. See C.N. 8623 and Capablanca’s Simultaneous Displays.

A selection of US newspaper references concerning Peter P. Tarasov:

(12162)

Other relevant feature articles:

Morrison v Capablanca, London, 1922

Andrew Bonar Law and Chess

The London Rules

Chess Cartoons by Tom Webster

Latest update: 22 June 2025.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.