Edward Winter

(2011, with updates)

In this game Black’s 33rd move is eye-popping:

Edmund E. Macdonald – Amos Burn

Liverpool, January 1910

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nd7 4 Nc3 Ngf6 5 Bc4 Be7 6 O-O O-O 7 Re1 c6 8 d5 c5 9 Bg5 h6 10 Be3 Kh7 11 h3 Nb6 12 Bd3 Bd7 13 a4 Rc8 14 a5 Na8 15 b3 Nc7 16 Ne2 Nce8 17 c4 Ng8 18 g4 g6 19 Ng3 Ng7 20 Qd2 Rc7 21 Kh2 Qc8 22 Rg1 f5 23 gxf5 gxf5 24 exf5 Nxf5 25 Nh5 Kh8 26 Rxg8+ Rxg8 27 Bxh6 Be8 28 Bg7+ Rxg7 29 Nxg7 Kxg7 30 Rg1+ Bg6 31 Ng5 Nh4 32 Bxg6 Bxg5 33 Bh5

33...Qg4 34 Rxg4 Nf3+ 35 Kg2 Nxd2 36 Rxg5+ Kh6 37 h4 Nxb3 38 Rf5 Nxa5 39 Be2 Kg7 40 h5 Rf7 41 Rg5+ Kh8 42 h6 Rf6 43 Rh5 Rf4 44 Rg5 Nxc4 45 Bd3 Nb2 46 Bc2 c4 47 Rg7 Nd3 48 Bb1 Rxf2+ 49 Kg3 Rb2 50 White resigns.

This brilliancy, which is sometimes even compared favourably with Marshall’s ‘golden move’ 23...Qg3 against Levitzky (or Levitsky or Lewitzky) at Breslau, 1912, is now an integral part of chess history and lore, yet a mere half-a-dozen or so years ago it was unknown even to well-informed chess enthusiasts. How is it possible for an old game to languish for so long and then go from obscurity to fame so quickly and belatedly? We offer a brief chronology.

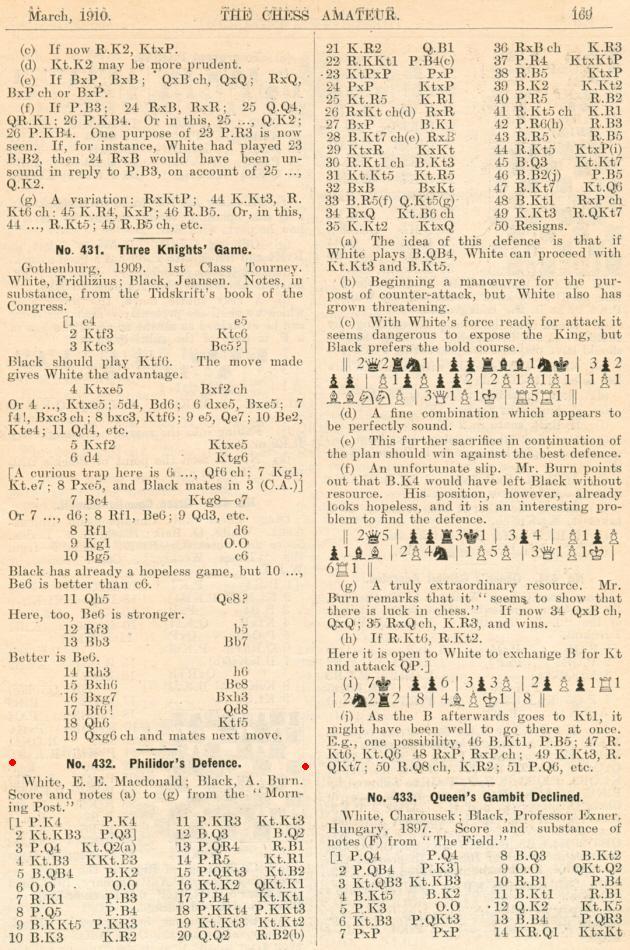

Having appeared in the Morning Post of 17 January 1910, the Macdonald v Burn game was given by the Chess Amateur, March 1910, page 169:

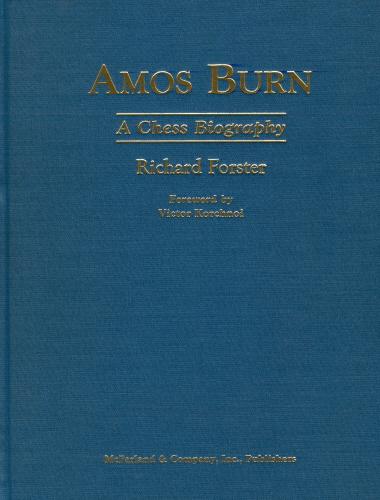

The eulogistic notes were evidently no substitute for eye-catching diagrams, and Burn’s brilliancy lay forgotten for nearly a century. Other periodicals of the time did not take it up (as they would surely have done if the Chess Amateur had given a normal diagram at move 33), and the game was not even in Amos Burn, The Quiet Chessmaster by R.N. Coles (Brighton, 1983). Indeed, we have not seen the game or position published in any book or magazine until Richard Forster included the full score in his monograph on Burn in 2004.

Upon receiving the volume, we wrote a brief item about it in C.N. 3404, as below.

If there is one chess book, above all others, that we would be immensely proud to have written ourselves it is Amos Burn A Chess Biography by Richard Forster (Jefferson, 2004). An impeccable McFarland hardback of 972 pages, it is simply of matchless quality.

For now we give, from a forgotten game on pages 689-691, a position which resulted in a move described by the author as the most extraordinary of Burn’s career and just as exquisite as Marshall’s famous 23...Qg3 against Levitsky in Breslau, 1912:

Black to move

This position arose in an offhand game at the Liverpool Chess Club in January 1910, White being Edmund E. Macdonald. Burn uncorked 33…Qg4.

The game continued 34 Rxg4 Nf3+ 35 Kg2 Nxd2 36 Rxg5+ Kh6 37 h4 Nxb3, and Black won the ending. Forster found the game in the Morning Post of 17 January 1910 and comments: ‘It is surprising that apart from the Chess Amateur no magazine or book ever seems to have reprinted this electrifying combination.’

Our item was written on 14 August 2004. Later that month, Tim Krabbé posted the game in his Open Chess Diary (items 258 and 260), with remarks which included the following:

‘Forster calls Qg4 “the most spectacular move of his [Burn’s] entire career”, but it comes close to being the most spectacular move of any career. In my series “The 110 most fantastic moves ever played”, it certainly belongs in the top ten – in fact it is more amazing and wonderful than Marshall’s comparable Qg3 against Lewitzky, which I put in third place.’

(On a small point of detail, Krabbé used the spelling MacDonald, rather than Macdonald, for unclear reasons.)

Hans Ree gave the position before 33...Qg4 in a review of Amos Burn A Chess Biography on pages 92-95 of the 8/2004 New in Chess. He commented:

‘One spectacular find was a move that will certainly find its place in collections of the most amazing moves ever played.’

And later in the article Ree continued:

‘Burn’s 33...Qg4 is as striking as Marshall’s famous move 23...Qg3 in Levitsky-Marshall, Breslau, 1912. Which one is the most beautiful? Marshall’s move was flashy, but not at all necessary, because there were many moves by which he would win. Burn’s fantastic 33...Qg4 was the only move to prevent an imminent loss, which is a plus, although on the negative side it must be said that it was not a winning move and maybe not even good enough to draw. After 35 Kg3 instead of 35 Kg2 the ending would be clearly better for White, the difference being that if Black plays as in the game, White has the strong move 37 Kh4. Nevertheless 33...Qg4 was a great move that makes for a wonderful picture.’

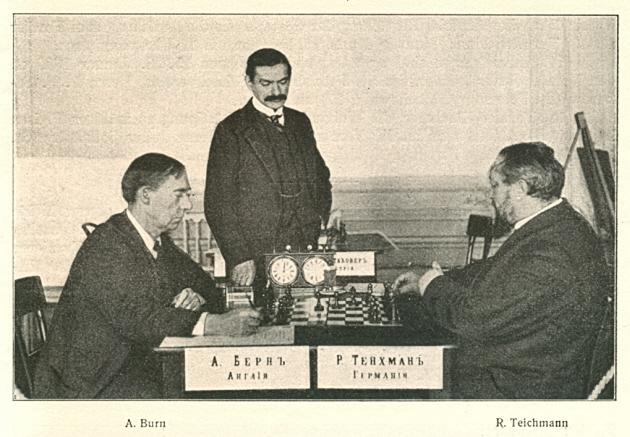

A photograph from page xiii of Der internationale Schachkongress zu St Petersburg 1909 by Emanuel Lasker (Berlin, 1909), i.e. less than a year before the Macdonald v Burn game:

When finalizing the present article we asked Richard Forster about his overall view today regarding the Burn brilliancy. He replied:

‘I have shown the position to a number of friends and masters. It is curious how, even for experienced masters and grandmasters, it can be very difficult to spot 33...Qg4, whereas some others, such as Kramnik, found the move in a couple of seconds. Hans Ree’s 35 Kg3 is a very strong improvement, of course, and I do not think that Black could have saved himself with best play in that case.

So 33...Qg4 may not actually make a difference to the final evaluation of the position; it may simply be the most stubborn defence.’

This article was originally contributed to the ChessBase website, where it appeared on 21 February 2011.

John Nunn examined the game on pages 19-21 of the January 2023 edition of Chess Moves.

See too The Chesswriting Practices of Christian Hesse.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.