Edward Winter

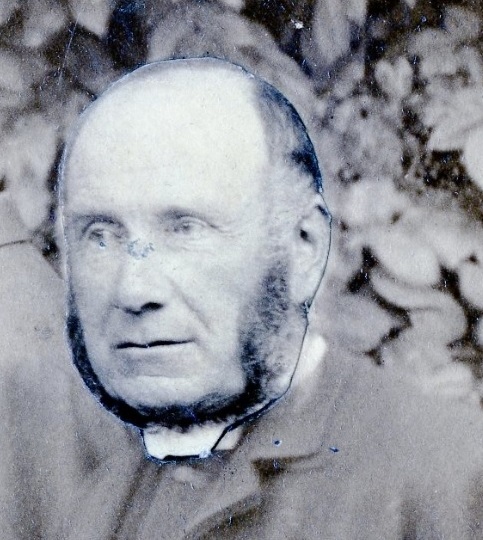

James Mason (1849-1905)

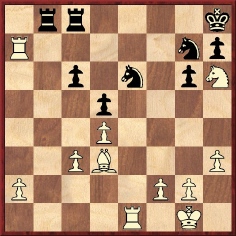

This was the final position of the brilliancy prize game Bird v Mason, New York, 1876, in which White has just played his knight from e5 to g6:

According to page 86 of The Book of Chess Lists by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1984) Mason resigned in view of 50...Kg7 51 Nxe7+ Kxh6 52 Nxc8. What about 52 Rg6 mate?

Page 257 of Chess Explorations noted that the identical oversight had occurred on page 10 of Les Prix de Beauté aux Echecs by F. Le Lionnais (Paris, 1951).

The September 1890 International Chess Magazine, pages 273-274, had a letter from Gunsberg to Steinitz explaining the details of ‘the first chess libel suit on record’. The Vienna paper Volksblatt was found guilty and fined for publishing a ‘libelous paragraph’ about the abortive Chigorin-Gunsberg match. According to Gunsberg, Chigorin suppressed the correct facts of the match negotiations and a false insinuation was taken up by the Austrian journal.

The following issue, pages 299-300, featured information on another chess legal case. Again Gunsberg was involved, although this time as the defendant. Francis Joseph Lee – and this is the only time we have ever seen his forenames in full in a contemporary source – sought leave to commence proceedings for libel against the editor and publisher of the Evening News and Post and its chess columnist, Gunsberg. The latter had allegedly ‘imputed or suggested a corrupt motive to Mr Lee in losing to Mr Mason a game in the Manchester Chess Tournament’. Gunsberg denied that he had imputed or suggested anything of the kind. ‘The learned Judge refused to make an order giving leave to prosecute.’

Steinitz commented:

‘In both cases Mr Gunsberg was successful, and we thoroughly sympathized with him in the first case, but cannot do so in the present instance. Mr Lee’s cause of complaint may not have been so strong as to warrant a legal prosecution, but it is to be regretted that even the slightest hint of professional dishonesty should have been given in a chess column, edited by a professional master, without the accusation being capable of absolute proof.’

From page 227 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 18 October 1890:

‘The unpleasantness so long existing between various of the professionals in the chess world has recently reached a climax hitherto unknown, we think, in the history of the game. Certain remarks of Mr Gunsberg’s, in his column in the Evening News and Post, having given offence to Mr F.J. Lee, that gentleman has sought redress in legal proceedings, and an application was made on Thursday, to the Vacation Judge in Chambers, for leave to commence proceedings for libel, against the editor and publisher of the Evening News, and Mr I. Gunsberg as conductor of its chess column. The learned Judge refused to make an order giving leave to prosecute.’

(1078)

See too Chess in the Courts.

Two of the references given in our article on old opening assessments:

On page 296 of The Art of Chess (London, 1895) James Mason wrote:

‘Fairly tried and found wanting, the Sicilian has now scarcely any standing as a first-class defence.’

In an article on pages 364-365 of the December 1956 Chess Review Bruce Hayden wrote:

‘But imagine my surprise when I asked the great old warrior [Bernstein] who was his favorite among the players of the past. “James Mason”, he replied, “Not because he was the strongest but because he played my two favourite combinations”.’

The item was reprinted on pages 116-120 of Hayden’s book Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings. The two combinations occurred in Mason v Winawer, Vienna, 1882 and Mason v Janowsky, Monte Carlo, 1902. Both games can be found in an article on Mason by Jim Hayes on pages 10-15 of the March 1997 CHESS. On the basis of detailed research in Kilkenny, Ireland, where Mason was born, Mr Hayes attempted to solve one of chess history’s most enduring mysteries: what was James Mason’s real name? Although ‘absolute final proof’ was admitted to be lacking, he expressed the view that there was ‘overwhelming evidence in favour of him being Patrick Dwyer’.

(Chess Café, 1998)

As shown in Chess and the English Language, page 309 of Anne Sunnucks’ The Encyclopaedia of Chess showed a shaky grasp of grammar:

‘Born in Kilkenny in Ireland on 19 November 1849, Mason’s family emigrated to the United States when he was a child ...’

Chess Jottings reproduces C.N. 1821, which reported that page 31 of Chess Trivia by Peter Hotton and Herbert A. Kenny (Boston, 1988) referred to ‘James Mason of Killarney’.

From page 5 of the New York Times, 28 March 1889:

‘Many of the spectators and the managers were disappointed in Mason. He was pitted against D.G. Baird, but when he came into the hall he was laboring under excitement, and it was said that he had been imprudent enough to visit a barroom with some friends. Nevertheless he insisted on playing, but after making eight moves he had to retire, giving up his game to his opponent.’

Page 293 of the New York, 1889 tournament book published the game-score:

David Graham Baird – James Mason

New York, 27 March 1889

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 exd5 4 Nf3 Bf5 5 Bd3 Bxd3 6 Qxd3 Nf6 7 O-O Bd6 8 Re1+ and ‘Game lost by forfeit’.

On page 237 of the August 1890 International Chess Magazine Steinitz described how in the New York tournament Mason ‘forfeited a game “by time” on the eighth move, and on several occasions, to speak in plain language, simply created disgraceful drunken disturbances’.

A further remark by Steinitz:

‘… Mr Mason when he descends from the heights of his obfuscated philosophy into the sober region of fact, has, so to speak, “no leg to stand upon”, which, of course, does not matter much to Mr Mason, who is notoriously rather unfamiliar with that sensation, outside of chess controversy.’

Source: International Chess Magazine, July 1885, page 208.

On page 138 of the May 1890 issue of his periodical Steinitz wrote: ‘Of course, Mr Mason’s manifesto must be taken cum grano whiskey.’ In the September 1885 number (page 265) a tournament reporter recorded being asked by a friend, ‘How is it that Mason has such a good chance of winning the first prize at Hamburg?’ The answer, with a reference to the tournament tail-ender, was, ‘Because he’s keeping Bier a long way off.’

These matters were originally discussed by us in Kingpin.

See also Chess and Alcohol, which includes the following from page 72 of Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938):

‘Blackburne showed how a chessplayer could drink, poor Mason, on the other hand, how one chessplayer would drink.’

Stephen Davies (Kallista, Australia) reports that pen-portraits of the participants in New York, 1889 were published on page 8 of the New York Times, 16 June 1889, under the heading ‘The Chessboard Kings’, with the subtitle ‘Ways and looks of 20 great players’. The extracts transcribed below (which often go awry with the players’ ages) focus on physical descriptions. On Mason:

‘Mason ... is a small man with dark hair and bright blue eyes. He comes from London, where he was left an orphan at a very tender age, and whatever prominence he has attained he owes directly to his own inherent genius. He has quick and clear perception at chess, and has the ability to circumvent an enemy. His only faults are boon companionship and a weakness for strong drink, of much of which he is physically unable to partake. ... He is a great smoker.’

(5710)

Who in the chess world was ‘The Stormy Petrel’?

The obvious answer may be Nimzowitsch, but he was not the first. Page 574 of the March 1882 Brentano’s Chess Monthly reported that Philip Richardson (1841-1920) attended the Café International in New York only ‘on rainy days, owing to the fact that he was a photographer and, consequently, was released from his duties at the camera in stormy weather; the coincidence of storms and his visits soon attracted notice, and he was promptly dubbed “The Stormy Petrel” by Capt. Mackenzie, and this soubriquet has clung to him to this day’.

The magazine then gave a few of Richardson’s games, the first of which was:

Philip Richardson – James Mason

New York, 1873

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 O-O Nf6 7 d4 O-O 8 Nxe5 Nxe5 9 dxe5 Nxe4 10 Qd5 Bxc3 11 Nxc3 Nxc3 12 Qf3 Na4 13 Qg3 Kh8 14 Bg5 Qe8 15 Rfe1 Nb6 16 Bd3 Qe6 17 Qh4 h6

18 Bf6 Kg8 19 Qg3 g6 20 Bxg6 Resigns.

No date was specified, but the game is also on pages 297-298 of the 1873 Chess Player’s Chronicle (where Black was merely ‘Mr M., … another strong player’). Brentano’s Chess Monthly wrote ‘First introduction of Richardson’s Attack in Evans’ Gambit’, but an earlier game, between Leow and Eliason (Deutsche Schachzeitung, March 1856, pages 94-95), had gone the same way until move 13. [As mentioned in a footnote on page 134 of A Chess Omnibus the game was a 42-move win for Leow.]

Richardson v Mason was repeated as far as 15…Nb6 in a well-known miniature won by Max Bier, who played 16 Bf6. Various sources give the date of that game as 1898, even though it had been published by the Deutsche Schachzeitung on page 117 of its April 1879 issue.

(2194)

Page 69 of G.E.H. Bellingham’s book Chess (London, 1908) quoted this remark by James Mason:

‘However bad the position, or strong the attack, in 99 cases out of a hundred, care and patience will find a way out.’

(2406)

From an article by O.C. Müller, on page 439 of the October 1932 BCM:

‘Another chess amateur at [Purssell’s] was a Mr Manley, proprietor of several public-houses in the City and the West End. He generally patronized Pollock and Mason; and becoming acquainted with me also, he asked me one day whether it was right to develop the pieces in the opening of the game! I hesitated to make a reply, but remarked at last that Pollock and Mason, when they said so, must be right, whereupon Mr Manley retorted: “You are wrong, and I will tell you why. As soon as I develop the pieces, Pollock and Mason take them off”.’

(Kingpin, 2000)

Below is an extract from London, 1899 Pen-portraits, from C.N. 2637:

‘Mason, who won ninth prize, played all his games seated the same way, with the same calm, the same stillness and the same disdainful, detached expression with which he looks at the board.’

C.N.s 2679, 2684 and 2690 gave a large number of quotes from Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). One of these, number 32, concerned Mason:

‘As player, he had the unique quality of competently simmering thru six aching hours and scintillating in the seventh. Others resembled him but forgot to scintillate.’

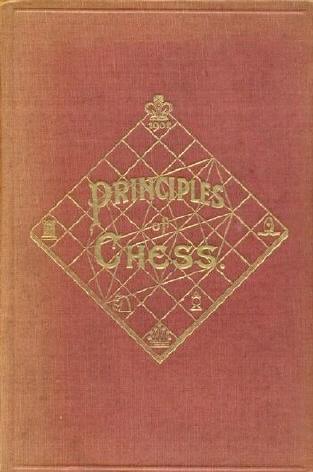

The opening of James Mason’s preface to The Principles of Chess (London, 1894):

‘Harmoniously uniting in itself the curious, the beautiful and the true, chess appears to hold a permanent relation to the innate susceptibilities of intelligence.’

After quoting this on page 73 of his book Portraits and Reflections (London and New York, 1929), Stuart Hodgson commented:

‘The rotund vacuity, the meaningless magnificence of the sentence … have always pleased me. Surely it would be difficult to find another example of nothing said in quite so grand a way.’

(2790)

C.N.s 2983 and 2998 (see pages 46-50 of Chess Facts and Fables) gave 18 forgotten games from Schaakkalender van het Noordelijk Schaakbond 1883 (Assen, 1883), including one played in Rotterdam on 22 October 1881 which, we stated, was between C.E.A. Dupré and James Mason. We are very grateful to Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) for pointing out that, as indicated on page 77 of the Schaakkalender, Black was J.H. Zukertort.

(4866)

Concerning the famous threat/execution remark attributed to Nimzowitsch, we note the following on pages xiv-xv of Chess Openings by James Mason (London, 1897):

‘A threat or menace of exchange, or of occupation of some important point, is often far more effective than its actual execution. For example, in the Ruy López impending BxKt causes the defender much uneasiness. He is, to some extent, obliged to confound the possible with the probable; while yet at the same time in serious doubt as to what may really happen.

Consequently, when you are attacking a piece or pawn that will keep; when you cannot be prevented from occupying some point of vantage, from which your adversary may be anxious to dislodge you; when you can check now or later, with at least equal effect; in these and all such circumstances – be cautious. Do not play a good move too soon. For when you do play it, the worst of it becomes known to your antagonist, who, then free from all doubt or apprehension as to its future happening, is enabled to order his attack or defence accordingly. Therefore reserve it reasonably, thus stretching him on the rack of expectation, while you calmly proceed in development, or otherwise advance the general interests of your position.’

(3257)

In 1900 James Mason published ‘a collection of short and brilliant games’ under the title Social Chess. In all, 131 specimens were provided, and only ten players were represented three times or more: Anderssen, Blackburne, Boden, Buckley, Mackenzie, Mason, Morphy, Platt, Rosenthal and Steinitz. Who, it may be wondered, was Platt?

Mason’s book itself offered some indications, for it included two photographs of ‘Social Chessmen of Many Ages’, and the following text on page ix:

‘The illustrations here presented to the reader represent 47 quaint chess pieces of various ages and from various parts of the world; and they have been specially taken for Social Chess from a private collection – that of Mr Charles Platt of Wetheral, and President of the Chess Club at Carlisle.’

(3504)

For further information about Platt, see the latter part of C.N. 3504.

On page 56 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984) G.H. Diggle wrote:

‘One seldom sees the name of James Mason (1849-1905) now; yet he was not only one of the inner ring of great masters but perhaps the finest chess writer of his time. His three great works were The Art of Chess, Principles of Chess and Social Chess. The introductory chapter of the last-named work has been ranked as one of the great set pieces of chess literature. Mason never wrote a dull sentence or used a redundant word.’

Social Chess ended (on pages 169-170) with ‘a few observations on the study and practice of chess’, and these included:

‘Many people imagine that chess cannot be profitably studied in books, that only “experience teaches”. But books are the body and soul of a vast mass of experience; and the study of book chess may be of the utmost value – to one who reads aright. As a matter of fact, and it is this which brings book study into disrepute, few players are more easily vanquished than those whose “book knowledge” is in advance of their practical experience. To be of real use, book knowledge should be made the player’s knowledge – a matter of general ideas, not of memory in detail, which applies only to the ABC of the game. The question always is “What should I do now? not what was I used to do, or what did so and so do in this or some similar position?” Chess cannot be taught, either by books or men, as one whistles tunes to a parrot.’

(3505)

As a heading to the Preface of Chess Facts and Fables (Jefferson, 2006) we gave the following quote from James Mason’s introduction to Social Chess (London, 1900):

‘Chess has its history, of course, and a long one, too, or rather several histories, each with its little fact and much fable, after the true manner of history in general.’

The earliest citation for Sitzfleisch in the Oxford English Dictionary is dated 1932 (The Lovely Lady by D.H. Lawrence), but Joost van Winsen quotes the following from page 121 of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice by James Mason (London, 1894):

‘A player has been known to refuse to proceed, on the ground that if he did so mate would happen to him forthwith. Another declared that as he could not afford to lose the game, it was incumbent upon him to “sit out” his opponent on that particular occasion. These are extreme cases, no doubt, but that they were possible and actual is unquestionable. In short, Sitzfleisch was the ultima ratio, and often prevailed.’

We happen to be able to quote an even earlier occurrence of the word, on page 113 of the December 1881 Chess Monthly:

‘It is Sitzfleisch that decides a game.’

(4316)

C.N. 4316 gave the full pseudonymous letter from ‘Philidor Jones’.

A cover oddity concerns books by James Mason (The Art of Chess, The Principles of Chess and Social Chess). They had a 7x7 chessboard:

(4651)

Pages 281-284 of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice (London, 1894) are reproduced in Stalemate.

Joost van Winsen submits the following game, which was annotated by Mason on pages 433-434 of the October 1890 BCM:

Siegbert Tarrasch – James Mason

Manchester, 1890

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 d5 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O O-O 8 Re1 Nf6 9 Bf4 Bg4 10 Nbd2 Nh5 11 Be3 Nc6 12 h3 Bxf3 13 Qxf3 g6 14 c3 Qd7 15 Nf1 Nd8 16 Bh6 Ng7 17 Ne3 c6 18 Ng4 Nde6 19 Re2 Qd8 20 Rae1 Bg5 21 Bxg5 Nxg5 22 Qf6 Qxf6 23 Nxf6+ Kh8 24 Re7 N5e6 25 Rxb7 Rab8 26 Rxa7 Rxb2 27 Nd7 Rc8 28 Ne5 Rbb8 29 Nxf7+ Kg8 30 Nh6+ Kh8

31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Nh6+ Kh8 33 Nf7+ Kg8 34 Ne5 Ra8 35 Rxa8 Rxa8 36 Nxc6 Rxa2 37 Ne7+ Kf8 38 Nxd5 Ra3 39 Bc4 h6 40 Nb6 Resigns. Mason: ‘The game was adjourned at this point, pro forma; but Black resigned without resuming, as his position was manifestly hopeless.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘When published in the International Chess Magazine (October 1890, pages 309-310) this game was stated to have lasted 37 moves, whereas its length was 38 moves in Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien (Gouda, 1925), pages 284-288, and 39 moves in the Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1890, pages 338-341. These last two publications had notes by Tarrasch.

The International Chess Magazine gave the following conclusion: 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 Resigns. Tarrasch’s book had 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 h6 38 Nb6 Resigns, whereas the Deutsche Schachzeitung put 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 h6 38 Nb6 Kf7 39 d5 Resigns.

The game, however, was adjourned (jokingly by Mason, according to page 271 of Tarrasch’s book). The time-limit in the Manchester tournament was 20 moves per hour.

To complicate matters further, however, the BCM stated that the game was “a friendly contest, played 28 August, at Manchester”. It should be noted that Tarrasch and Mason met in the tournament on 29 August.’

(4740)

Our earliest known occurrence of the word chessist was the following:

‘The centralisation of the chess resources of this country is a subject that must sooner or later recommend itself to all energetic English chessists as one that deserves to be taken in hand with a view to its realisation.’ City of London Chess Magazine, July 1875, page 163.

Now, though, Joost van Winsen has found the following in James Mason’s column ‘The Chess Board’ on page 284 of The Spirit of the Times, The American Gentleman’s Newspaper, 1 November 1873:

‘Every chessist should consider it a duty, if not a pleasure, to do his utmost to advance the interests of the “king of games”, that peerless amusement in which he has whiled away so many hours in the past, and which he regards as an unfailing source of delights in time to come.’ [Subsequently, an earlier (1868) occurrence of the word ‘chessist’ was found; see Chessy Words.]

Mr van Winsen comments that the whole article, written when Mason was 23, is of interest:

‘An American Chess Congress

It is safe to say the “cause” never presented a more flattering appearance than it does at the present time – nor was the outlook ever so cheering. At first sight it looks as if the period of the “Morphy excitement”, properly so called, might be cited as an exception to this statement; but a little reflection will convince us that it is an apparent exception only. It is true that immense enthusiasm was aroused by Morphy’s really wonderful achievements, but that enthusiasm owed its being to feelings of a national, rather than to those of a Caissan character and derived its support from an affected, rather than a true, perception of the utility of chess itself. Morphy’s victories over the greatest foreign masters were regarded as a national triumph. The popular heart was fired, and chess became the rage from one end of the country to the other. It suddenly became fashionable to play chess, and consequently everybody wanted to play it. Chess columns were started in half the newspapers in the land; chess clubs sprang up like mushrooms – we went to sleep ignorant of the names of the pieces and awoke a nation of chessplayers. Now something analogous to all this would have occurred had Morphy been a bagatelle player, or a skittle player. The sudden and unprecedented, not to say wonderful, interest manifested by people in the game of chess was not created by anything in the game itself – by any popular appreciation of its many and strong claims to be ranked as the chief amusement of civilization – but was solely attributable to the fact that a young American had beaten the “world” at it. The fact is chess was used as a vent for the almost superabundant vanity of the nation. Everybody is aware of the consequences. The reaction came and came with a vengeance – hastened perhaps by the civil war – and for a long period chess with us might nearly be regarded as one of the “lost arts”.

But we are now upon better times. The spirit abroad draws its inspiration from the game itself, as a genuine healthy spirit should. On every side there are evidences of an increasing interest in, and an increasing admiration of, the science and art of chess-play which are creditable to our day and country. We have a chess literature unexcelled, if equalled, by that of any other nation. We have many flourishing chess clubs, many fine players and very many fine problematists. But here we stop, and compared with other countries in which chess flourished to greatest advantage the stoppage is in the highest degree unfavourable to us. We stop in this: We have no organization. We should not indolently content ourselves with the present condition of chess, while a great opportunity to improve it exists on the one hand and a certainty that, if we don’t improve it, it will retrograde, meets our eye on the other. It may not be generally admitted, but it is not the less a fact, that the popularity of chess depends very greatly upon the skill and number of its foremost players. Of course the term popularity is here used restrictively. Chess can never be popular as the race-track, the ball field or the billiard table is popular. There is absolutely nothing in it that appeals to the eye. It is, as it were, a contest of mind against mind – a conflict of ideas. Everyone conversant with chess knows that even the board and men are not essentials to chess-play. Many persons can and do play chess without them. In point of fact they are aids to the memory and nothing more. The moves in a game record but a modicum of the conceptions of the players – the combinations which actually take place on the board being but a small part of those which occur in the mind. All this being so, and, further, the element of chance being absent, it is clear that chess can never be popular in the full sense of that word. But, though chess may not become popular, it may become a subject of interest to the great mass of the thinking community. Though lovers of the game can scarcely hope to see the day when thousands will flock to witness a match between two or more great players, yet they may reasonably look forward to a time when chess will occupy a position in the public mind out of all comparison with its present one. Now, the popularity of chess depending so much upon the number and skill of its exponents, the duty of all having the interests of chess at heart is plain and not to be mistaken. That duty may be expressed in one word, namely, organization. By organization alone can the standard of play be raised, can first-rate players be produced, and the interest of chess be efficiently and vigorously prosecuted. The advantages of organization are so numerous and varied, its benefits are so immediate and abiding, that it is really a mystery why chessplayers, of all people in the world, ignore it so utterly and complacently. Every chessist should consider it a duty, if not a pleasure, to do his utmost to advance the interests of the “king of games”, that peerless amusement in which he has whiled away so many hours in the past, and which he regards as an unfailing source of delights in time to come. But if he does not feel disposed to do his utmost, he should at least do something. For instance, let him perform the not very arduous feat of becoming a member of the chess club existing in his vicinity; or, if no club exists there, let him make a gentle effort to organize one; or, let him try his hand at evangelizing the heathen – enlightening his benighted friends somewhat as to the nature of the game and teaching them how to play it. Every community of consequence should have its chess club, every State its association; and, above all, a national association should be a fact accomplished if we are to improve or even maintain our present position in the ranks of chess-playing nations. In 1876 America will hold up for the admiration of the world her products and manufactures; her inventions and works of art will challenge the admiration of the human race, for her progress in the “useful”, the “beautiful” and the “true”. In less than three years from today the grand results of the labours of humanity, in thought and in action, will be on exhibition in the city of Philadelphia – if chess, one of the most wonderful productions of the human mind fail to have a place in that exhibition, it will be incomplete. And, right here, we may say what we should perhaps have said before. We may say that we received a communication from a gentleman well and favourably known in the “chess world” asking our opinion as to the feasibility and expediency of a national tournament in the United States during the season 1873-74. We – but we shall let him speak for himself.

“To the Chess Editor of the Spirit of the Times

Sir: – If you desire you can publish the fact that I will (though a poor man) contribute without fail fifty dollars (50) towards a National Tournament in 1873 or 1874. I should prefer having it held in Boston or Washington, but will contribute the above amount no matter where it is held. I think if you take the matter in hand and publish the bona fide offers you can get up a grand National Tournament before Spring.

J.A.C. [James A. Congdon]”

We reply to J.A.C. that a general tourney of American players to be held in 1873-74 is not only feasible and expedient, but absolutely necessary, if the International Congress of 1876 is to be a success. There is no time to be lost. Let all chessplayers unite in this thing and we shall see it accomplished. By means of it, an association of American chessplayers may be brought about that will render the failure of the International Congress an impossibility instead of a certainty as it seems to be at the present time. What say our friends in New England? and in Pennsylvania? and in the West? and in the South? We should be pleased to publish the names of all who may wish to contribute toward this undertaking and shall give all communications on the subject our undivided attention.’

(4461)

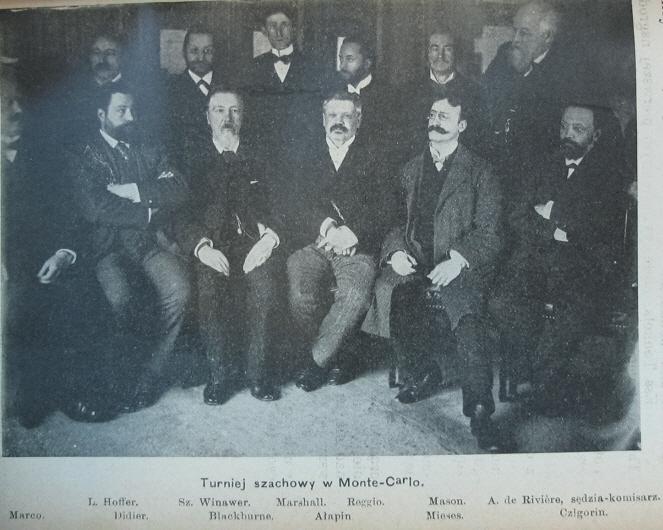

Tomasz Lissowski (Warsaw) submits the above group photograph of Monte Carlo, 1901, published in that year’s Sport, a Polish weekly periodical. He asks whether a copy of better quality can be obtained.

(5305)

From the chess column of Robert John Buckley in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury of 15 April 1905, page 25:

‘A curious and apparently contradictory feature in James Mason’s character was his interminable patience. Racially, Mason was of the most impatient, the most impulsive, the most hot-headed temperament in Western Europe. Mason was a Kelt of the Kelts, a really Irish Irishman, and not in the smallest fragment of his being, one of the Scots-Irish or the Anglo-Irish who dominate Ulster.

And here I may tell the world something which has not before been hinted, either in print or, so far as I know, in any other way.

James Mason’s true name was neither James nor Mason. His real name was confided to me years ago, as it were, sub sigilla confessionis. Later he wrote:

“My father adopted the name of Mason on landing in New Orleans when I was 11, his object being avoidance of the prejudice which obtained against the Irish. Don’t split on me till I’m dead, and even then I would rather you didn’t give the name, it’s so infernally Milesian, and they’d say that all the faults of the race went with it, particularly love of drink and laziness. I have them both myself!”

The real James Mason was unknown and incomprehensible to the huge majority of the people with whom he associated, and their estimate of him, their measuring his bushel by means of their pint-pots, is ludicrous indeed. It may be that in the time to come this column may present a few extracts from Mason’s letters, of which about 400, some of them very long, regular essays, addressed to the writer, are available.

Mason was a great letter-writer, and when addressing people with whom he was in sympathy, was apt to let himself go.

And thus I have strayed from the subject of Frank Marshall to one of the “sceptred heroes who still rule our spirits from their urns”. No matter. The Masonic secret should be interesting. Perhaps Mason had other confidants. Yet he was never one of those who wear their hearts on their sleeves for daws to peck at.

One thing I wish to place on record. In money matters; in straightness; in all things where honour was a factor, I ever found James Mason the very soul of integrity; and in this respect as well as intellectually, immeasurably superior to some of the men who smiled upon him patronizingly, and held him in contempt because of his poverty and the well-known weakness which all his friends deplored.’

James Mason

(6126)

The Buckley passage from the Weekly Mercury was first quoted by us in C.N. 1673, via the New Orleans Times-Democrat.

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks whether, further to C.N. 6126 and our feature article on R.J. Buckley, any new information is available from a reliable source as to whether James Mason’s original name was Patrick Dwyer.

(11893)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In answer to your correspondent’s query in C.N. 11893, it seems fair to say that there is a lack of direct evidence linking Patrick Dwyer to James Mason, and, hence, the case for it is not a strong one.

In addition, a specific (and almost certainly fatal) flaw in the argument may be found in the circumstances of the baptism of “Pat Dwyer”, which was discussed in an article by Jim Hayes, entitled “James Mason 1849-1905”, on the Irish Chess Union website. Mr Hayes commented:

“... the balance of probability being that Patrick Dwyer, son of John Dwyer with mother’s maiden name given as Mary Dwyer, both of Barrack Street, Kilkenny, who was baptized on 20 November 1849, in St John’s parish in the city of Kilkenny, was to become the future James Mason.”

This baptism register can be viewed on-line at Ancestry.com. Two pages further on in the same register (on page 114) is to be found the baptism of a second “Pat Dwyer”, evidently to the same parents, on 9 March 1850. The normal reason for parents reusing a forename is that the first child has died, and there seems no reason to suspect that this is an exception (although it would obviously mean that the first baby of that name had been born at least nine months before 9 March 1850).

That the parents were the same in the two baptismal entries is corroborated by the names of the godparents and the place of residence, both of which are identical. The only slight irregularity, which is of no consequence, is that the parents in the first baptism were recorded as John Dwyer and “Mary D[itt]o”, while in the second entry the mother’s former surname is given, Mary Walsh, as is common practice in Catholic registers, and in keeping with other entries in this one.

As regards the “Pat Dwyer” who was baptized on 9 March 1850, there seems little reason for anyone to suggest that he could have become James Mason. To judge from remarks made by Mr Hayes in his article, it would seem that baptism within a day or two of 19 November 1849 was a key factor in his choice of Patrick Dwyer.’

(11899)

The matter of where Mason was born has also been discussed in a thread at the English Chess Forum. On 5 March 2021 Gerard Killoran posted an interview (from page 2 of the London Middlesex Gazette, 19 August 1893) in which Mason stated:

‘I was born in Ireland in 1849; from thence I went to America, and finally came over to London in 1878.’

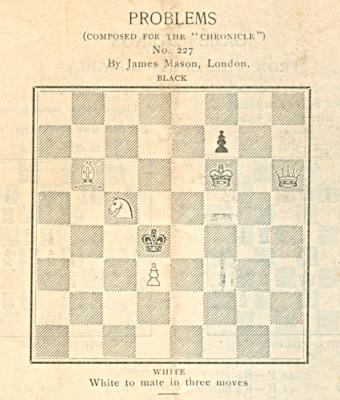

From page 172 of the 9 May 1889 Columbia Chess Chronicle:

The key given on page 218 of the 27 June 1889 issue was 1 Qh3, but there is also 1 Qf4+.

(6645)

‘A player in a fog as to the movements of two or three pieces – what will he do with two-and-thirty?’

Source: The Art of Chess by James Mason (London, 1898), page vii.

From page ix:

‘We should, first of all, be intent upon the end at which we would arrive, if we would best avail ourselves of the means of getting there. Thus, in chess, it is the end we should consider first, so as to more easily master the simple ideas of the game, that we may become readily familiar with them, in order to go on with confidence to their combination or involution. Again, if you do not know what to do with three pieces, what about thirty-two?’

And from page xi:

‘Of all parts of the game, the opening, say, the first dozen moves or so, is ever the least understood, even by the accomplished player, and it is just this part that the neophyte is usually recommended to master at the beginning. A more fatuous gripping of the wrong end of the stick it would be hard to imagine. It is as if the cadet were to devote himself to the mastery of the higher tactics or strategy of a grand army in the field, while yet innocent of company drill, or of the formations and evolutions of a single battalion.’

The second edition of Mason’s book has been quoted. The chapter in question, ‘Method’, is absent from the original edition (London, 1895).

(8749)

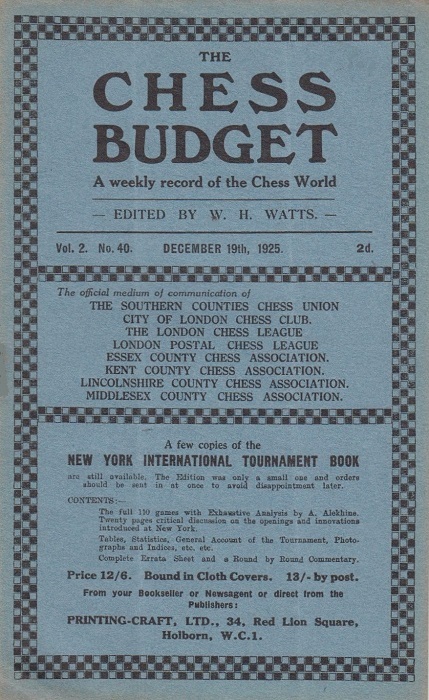

Writing in the Chess Budget (C.N. 9611), W.H. Watts stated that James Mason died on 18 January 1905. No place was mentioned.

Many contradictory versions can be found, the most obviously wrong being what appeared in Harry Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess. In the entries on Mason in both the hardback and paperback editions (1977 and 1981 respectively), 15 January 1909 was given. From some other reference books:

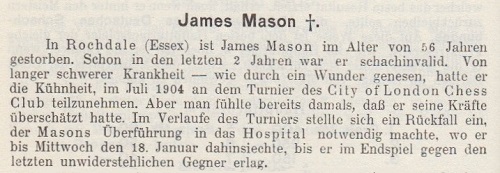

The British newspapers of 1905 that we have seen so far offer little information of substance. As regards chess magazines of the time, a selection is shown below, beginning with page 44 of the Wiener Schachzeitung, February 1905:

Page xi of the 1947 edition of The Art of Chess (revised and edited by F. Reinfeld and S. Bernstein) affirmed that Mason ‘died in Rochdale, England on 18 January 1905’. Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987 and the unpublished 1994 edition) had 15 January 1905 in Rochford, England. Page 141 of James Mason in America by J. van Winsen (Jefferson, 2011) gave 12 January 1905, with a footnote stating that ‘Mason’s death certificate has the date 12 January 1905’.

Further information is sought. The place name ‘Rochford’ (as opposed to Rochdale, Lancashire) is corroborated by a news paragraph on page 468 of the December 1904 BCM:

‘The Rev. Talfourd Major, Rector of Thundersley, Essex, informs us that Mr James Mason is lying dangerously ill in Rochford Infirmary, and it is feared will never be well enough to leave it alive.’

The earliest occurrence of ‘Rochdale’ that we have traced is in the obituary by Hoffer, which had several errors, in The Field, 21 January 1905:

‘With deep regret, which will be shared by chessplayers all over the world, we have to announce the death of James Mason, at Rochdale, Essex, at the age of 56 [sic – 55]. For nearly two years Mason had been an invalid. Recovering almost miraculously from a serious illness, he had the temerity to take part in the tournament at the City of London Chess Club in July, but it was felt that he overtaxed his energies and that this would be his last appearance in important events. He was, we might say, goaded into taking such a serious step by the irksome paragraphs about his illness which were supplied to the sensational press by unscrupulous news hunters. “I just wanted to show them that I am not dead yet”, he told us when asked why he decided to take part in the tournament. So reticent was he about private matters that upon inquiry about these reports he replied: “The pars in the press are right enough. But I cannot even surmise who authorized them. I had a strong epileptiform attack, but it passed, I believe – hope – without inflicting any permanent injury. But it is hard to tell. ‘Snaix is snaix!’ The fact is, I have been seriously ill for the last five years.” After the exertions in the tournament mentioned he had a serious relapse, necessitating his removal to the hospital, where he lingered on till Wednesday [which indicates Wednesday, 18 January], when he lost the endgame against the implacable adversary.’

(9612)

From William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia):

‘James Mason’s entry in the printed indexes of the Principal Probate Registry of England and Wales, which are officially compiled and available on ancestry.co.uk, reads as follows:

“James Mason of Blodwin Cottage, New Thundersley, Essex, died 11 January 1905 at The Infirmary, Rochford, Essex. Effects £151. Administration to Annie Mason, widow.”’

C.N. 9612 quoted Hoffer’s statement in The Field of (Saturday) 21 January 1905 that Mason had died on Wednesday which, we noted, indicated 18 January. However, if Hoffer had in mind the previous Wednesday, his information would match that quoted by Professor Rubinstein.

(9615)

From an article by Fred Reinfeld about Alexander Kevitz on pages 25-26 of the April 1946 Chess Review:

‘He credits much of his early interest and rapid progress to Mason’s Principles of Chess. (Years ago, by the way, the famous Mexican player Carlos Torre told me in almost the same words of his great debt to Mason’s books. Mason was not only a master of clear exposition; he also knew how to kindle the reader’s interest and how to stimulate his curiosity.)’

The same year, Reinfeld brought out a new edition of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice, published by David McKay Company, Philadelphia (and reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., New York in 1960). The entire games section was replaced by 50 games annotated by Reinfeld.

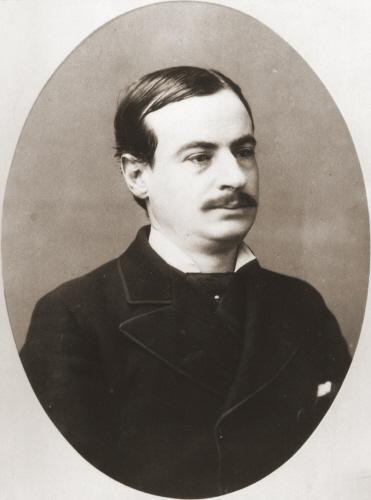

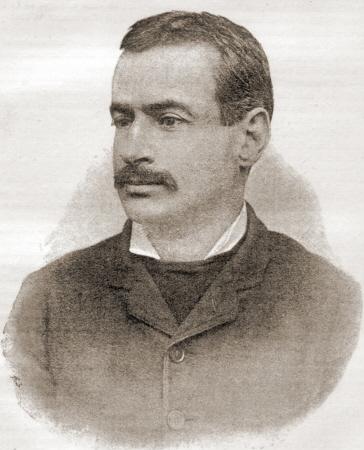

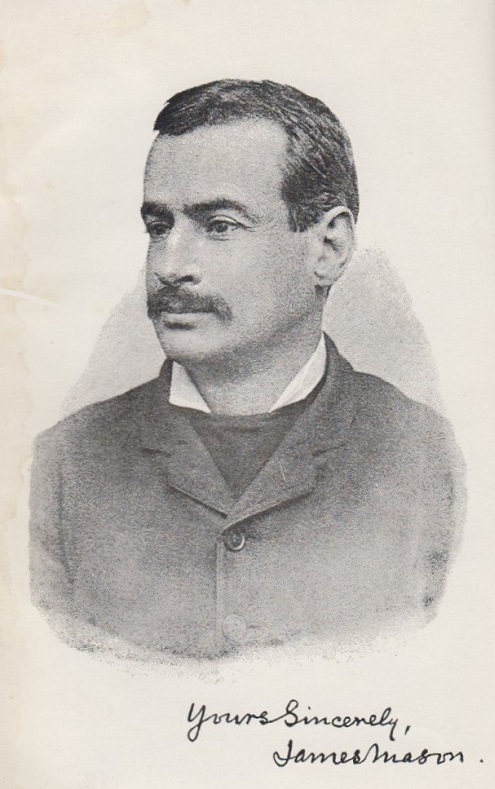

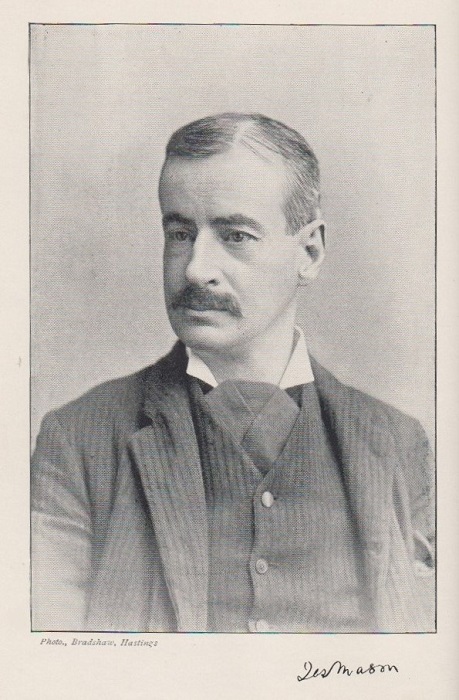

The frontispiece of the original (1894) edition of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice:

(9610)

For another specimen of Mason’s signature see Chess Autographs.

James Mason (Hastings, 1895 tournament book, opposite page 19)

‘For sheer chess genius James Mason was, in my opinion, probably the finest player who has ever lived. This may sound a somewhat tall statement, but it will be more readily accepted by those with a thorough knowledge of chess and chessplayers than by those whose knowledge is more superficial. If ever a player lived before his time, that man was Mason. He was a player most difficult to place definitely into one school. He did not live in a transition period which had it been true might have accounted for his mixed genius. He had not the opportunities of the modern player and yet he had ideas upon opening and development which are in strange accord with those of today. Again, as a contemporary of Steinitz, it is not strange that he should show allegiance to that master’s theories in much of his play, and in his writings. All the same, many of his games show him capable of the deepest combinative play – the grand style – the oft lamented old school of Morphy and Anderssen. A frequently quoted game of his was that against Winawer at Vienna in 1878 [sic – 1882]. It is really a fine game second to none in depth of combination although the material sacrificed may not be so much as in some better known games.’

Source: An article entitled ‘James Mason’ by W.H. Watts on pages 82-83 of the Chess Budget, 19 December 1925.

W.H. Watts added:

‘Not one of the many hundreds of chess books that I have ever had has given me one tenth of the pleasure I got from The Art of Chess. It contains hundreds of positions all from actual play and shows how the winning combinations have been evolved – or having obtained winning positions how best to finish them off. In this way instruction is acquired incidentally and not laboriously. Many of them can be followed by a mere tyro without a board and men from the diagrams themselves. It was a book on an entirely new principle – and it had obviously meant a terrific amount of work – much more than merely reprinting the full score of a number of games and giving a few notes. The Principles of Chess was the finest book for the learner available, and although since his time there has been a great advance in chess text books, no better elementary text book has been produced. The selection of games and the annotations at the end of this book have never been surpassed.

Social Chess, as its name implies, is a less ambitious and less serious book. It contains a collection of short games with bright attacking finishes and examples of clever combinative play.

Mason had a marvellous command of the English language. His introductory chapters to these three books are models of really beautiful English. Clear, concise and to the point, what he writes can be read merely for its style, let alone the subject-matter. Again, his writings show him to have been a man of considerable education.’

The appreciation by Watts then discussed Mason on a more personal level:

‘As a man Mason always struck me as a sardonic misanthrope, a sort of disappointed man. In company with James Platt, of Carlisle, I played him a consultation game. It was a long game for a fee which Mason had already received. As soon as it was over he pushed up the pieces without a word and went off with just a typical glint of a smile – almost contemptuous. Other occasions when I saw him he seemed to have that same smile for opponents and friends alike. At the Hastings and London tournaments and at the City of London tournament – his last appearance and the one at which he did so very badly – I cannot ever remember hearing him speak a single word. All the same, socially, and away from chess, Mason was a bright and entertaining conversationalist, full of interesting anecdotes and reminiscences, and in convivial company he could be a great success – but suddenly he would become mute and nothing would move him.

Although in later years I knew him fairly well, he would never do more than nod – and always wore that queer smile which one can still see in the frontispiece to The Art of Chess.’

It was the same frontispiece as in The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice, which was shown in C.N. 9610.

(9611)

In a letter on page 441 of CHESS, 20 August 1955 P.N. Wallis of Quorn referred to ‘dull and unenterprising chess which is prevalent in this country’, adding:

‘The remedy is quite simple. In the British Championship and similar tournaments let a win count 3 points and a draw one to each player, thus putting a premium on the win.’

On page 454 of the 30 September 1955 issue, R.W. Ives of Leeds responded:

‘Mr Wallis raises an old issue. James Mason in 1895 advocated allowances of 1, 0 and minus a half for a win, a draw and a loss respectively, and this seems to me mathematically more logical than the present system. Certainly it seems now that quite a few halves can be picked up in a congress without much thinking. Why should a pre-arranged draw improve either player’s score? The position should be the same as before they started. A player who has lost has a worse record after the game than when it started. Can your readers work it out?’

A contribution from C.J.S. Purdy of Sydney was published on page 93 of the 10 December 1955 issue:

‘R.W. Ives (CHESS, 30 September) did not realize that James Mason’s proposal to award 1,0 and minus a half for a win, draw and loss respectively is mathematically exactly the same as P.N. Wallis’s proposal to count a draw as worth one third of a win. This is easily seen if you add a half to every player’s score in every game, irrespective of his result (this cannot affect the positions). You then get 1½, ½, 0; or, eliminating fractions, 3, 1, 0, which is Mr Wallis’s system. Less drastic, of course, would be 5, 2, 0. Mathematically, there is no objection whatever to penalizing draws.

The references above to James Mason’s proposal in 1895 concern the extensive correspondence (also involving E.N. Frankenstein and W. Sonneborn) published in the BCM that year and in 1896. However, Mason had made his proposal in a letter (London, 10 December 1892) on pages 40-43 of the January 1893 BCM. On page 42 he wrote:

‘A win should count 1, a draw 0, and a loss minus ½ only, it being in reality no more. It takes two to make a game. What any player loses in losing any particular game is not the whole of that game, but only his own individual half of it, or his chance of winning it. The game counts 1 to the winner; that 1 is made up of twice ½ – his own ½ and his opponent’s ½ – only one of which is, strictly speaking, either won or lost. In fine, the system here proposed is a natural system, and the only one which can be substituted for the present system with advantage to all concerned. It would encourage every player in a tournament to do his best to win, the draw being valueless for scoring purposes.’

(10251)

The above quotes are extracts from C.N. 10251 which directly relate to Mason.

From an unsigned article about London, 1899 on pages 9-10 of the July 1899 American Chess Magazine:

‘Mason has in him a talent for the game that in any other man would have made a champion.’

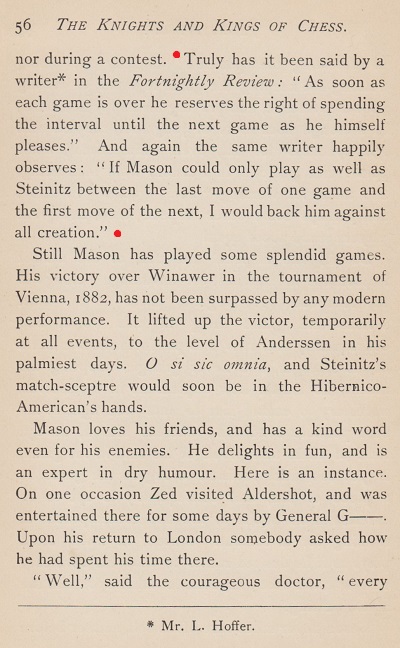

The remark brings to mind page 56 of The Knights and Kings of Chess by G.A. MacDonnell (London, 1894), in the chapter on Mason:

Some passages by later writers:

G.H. Diggle, Newsflash, April 1980; see too page 56 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984);

K. Landsberger on page 239 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion (Jefferson, 1993);

A. Soltis on page 33 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion (Jefferson, 1994).

We note, firstly, that in his obituary of Mason in The Field, 21 January 1905, Hoffer did not claim to have made the remark:

‘It was aptly said of him: “If Mason could only play chess as well as Steinitz between the last move of one game and the first move of the next, I would back him against all creation.” We leave the aphorism as it stands.’

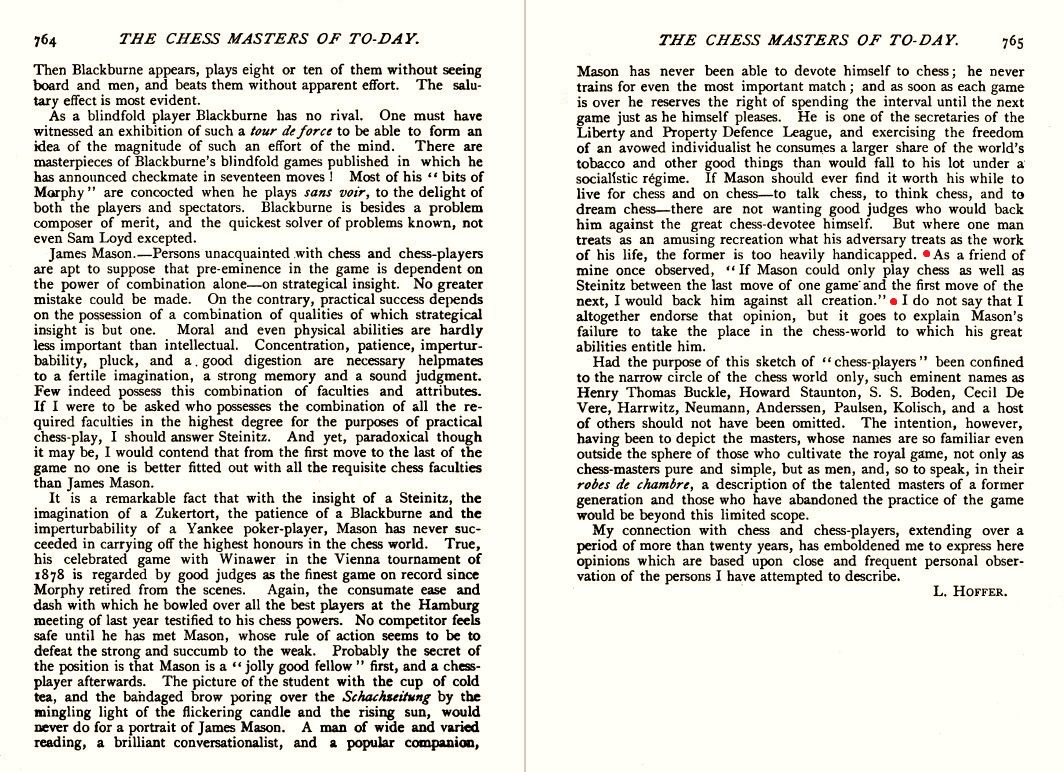

Moreover, on page 765 of the Fortnightly Review, December 1886 Hoffer not only attributed the comment to an unidentified third party but also slightly distanced himself from it:

‘As a friend of mine once observed, “If Mason could only play chess as well as Steinitz between the last move of one game and the first move of the next, I would back him against all creation”. I do not say that I altogether endorse that opinion, but it goes to explain Mason’s failure to take the place in the chess world to which his great abilities entitle him.’

Hoffer quoted that passage in a feature about Mason on page 66 of the Chess Monthly, November 1888.

His 13-page article in the Fortnightly Review proved highly controversial, and we present it in full, together with some of the reaction, in The Chess Masters of To-day by Leopold Hoffer.

(10287)

White to move

As reported on page 386 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, Ossip Bernstein stated that his favourite player was James Mason, ‘not because he was the strongest but because he played my two favourite combinations’. The games were Mason’s victories as White against Winawer (Vienna, 1882) and Janowsky (Monte Carlo, 1902).

C.N. 9611 quoted W.H. Watts’ praise of the Winawer game in an article about Mason on pages 82-83 of the Chess Budget, 19 December 1925. Mason’s own annotations were on pages 210-213 of The Principles of Chess (London, 1894) and were quoted in part by Steinitz on pages 56-57 of the second part of The Modern Chess Instructor (New York, 1895). After 43 Rb7+ in the diagrammed position Steinitz commented: ‘One of the grandest two-move winning strokes on record in master play.’

Steinitz also wrote about the game in The Field, 24 June 1882, page 881:

‘The game between Mason and Winawer belongs, to quote an expression of Herr Falkbeer, to the “finest gems in the jewel box of Caissa”. Though at first it dragged itself along as a slow fight for position, the finish was one of extraordinary beauty. On the 34th move Mason won a pawn and then directed his attack on both wings, while his opponent pressed in the centre. On the 40th move Mason initiated one of the finest and [most] original combinations that has ever been produced in practical play.’

Steinitz called 43 Rb7+ ‘a wonderfully brilliant stroke’.

(10816)

C.N. 10816 referred to two brilliant combinations by James Mason, yet the following may be noted from page 25 of the Chess Weekly, 27 June 1908:

‘... a combination at chess should be adroit and witty, rather than lingering and exact. As a case in point, the play of Paul Morphy, who before all things was a combination player, may very well be contrasted with the siege-like style of James Mason, who rejoiced in the sombre, slow-marching sort of game which, even in the playing over, takes half an hour to pass a given point. Morphy made epigrams on the chess board; Mason expressed himself at considerable length.’

(10849)

Our feature article What is a Chess Combination? includes the following:

‘Combination is defined as two or more moves having a common object, whether offensive or defensive, and it may have place anywhere or everywhere in the game.’

Source: The Art of Chess by James Mason (London, 1898), page xi.

On pages 62-63 of the March 1945 BCM Wahltuch wrote an obituary of Louis Zollner which related an episode involving James Mason:

We have not yet found information about the Newcastle v Manchester match.

(10881)

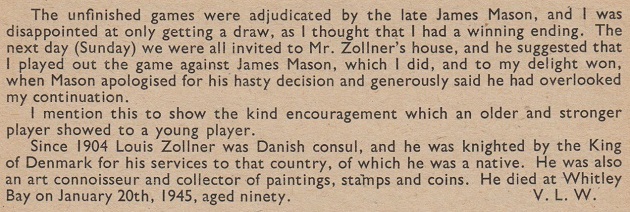

In this well-known picture from page 209 of the Illustrated London News, 29 August 1885 the caption has inverted Thorold and Mason’s names.

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) draws attention to a photographic version at the Herefordshire History website. It is unclear to us what has happened to A.B. Skipworth:

A different group photograph taken during the tournament was auctioned in September 2018 and can currently still be viewed at the Invaluable.com website.

(11316)

From John Townsend:

‘Several sources indicate that James Mason was for some time employed as a newsboy in New York. For example, an article appeared on page 5 of The Sun (New York), on 25 June 1882, entitled “The Newsboy Chess Player”:

“Fifteen years ago or thereabouts a bright-faced youngster “established himself in business”, as he was fond of telling his customers on board the Fulton Ferry boats. His business was selling the morning and evening papers. In time, he had a list of regular customers, who waited till they were on the boat to buy papers of him. The youngster’s name was James Mason. In those days Otis Field, well known to New York billiard players, kept a billiard room in the basement at the northeast corner of Fulton and Nassau streets. On the Nassau side he had tables for chess and draughts. The newsboy had to pass the place four times a day, and, as the windows were open in warm weather, could not fail to see the chess games, with their carved men. One day, while he was watching the pieces with boyish interest, an old gentleman at one of the tables beckoned him down stairs ...”

The chronology in this article may not always be accurate. It can be viewed on the Chess Archaeology website.

To this picture, Stephen Davies, on page 37 of Samuel Lipschütz: A Life in Chess (Jefferson, 2015), adds that, having sold newspapers in the morning, Mason worked in the delivery department of the New York Evening Telegram in the afternoon.

The New York Evening Telegram was established (in 1867 according to Chronicling America) by James Gordon Bennett, the son of J.G. Bennett. The Oxford Companion to Chess (Hooper and Whyld, second edition, 1992, page 250) makes the following comment in connection with Mason:

“Coming to the notice of J. Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald, he was given a job in the newspaper’s offices ...”

Meanwhile, using Chronicling America it is possible to follow newspaper reports of the newsboy’s growing force over the chequered board and his advancing fame. When the New York Herald, 16 January 1869, reported on page 7 about the “Handicap Chess Tournament” at Seider’s Café Europa, Nos. 12 and 14 Division Street, “Captain George Mackenzie being the manager”, James Mason was noted as being “among the most prominent” players.

On page 9 of the New York Herald of 7 May 1870, which looked forward to the approaching Baden-Baden congress, “J. Mason” was identified as someone who could ably represent chess in America. As it turned out, no US players took part.

He was occasionally mentioned in the press in connection with local chess activities, as in a report in the New York Herald of 28 October 1870 (page 8):

“This evening the Nineteenth Ward Chess Club will play their return challenge game with the Downtown Chess Club at the Europa Chess Rooms, 12 and 14 Division Street, at eight P.M. Messrs. Perrin, Mason, Merian, prominent players, also a committee from the Williamsburg Chess Club will be present to witness the contest ...”

Fairly close in time to the above reports was the United States Federal Census of 1870, which can be viewed on-line. The census day was 1 June, and no reason is known not to expect Mason to have been in New York at that time. Only one James Mason entry has been found which is at all consistent with his place of residence, his occupation, and his supposed age. A certain James Mason, aged 22, resident in New York city’s 9th District and 6th Ward, is described as a “vender” [sic]. Vendors were commonly seen on the streets of New York. Newspapers were among the items which could be bought, and, although the merchandise sold by this James Mason is not recorded, the description of “vender” is consistent with what is known of the chessplayer’s work. Residence in New York city is in line with expectation, and the age is also tolerably accurate. In the same household are to be found his father, James Mason, aged 52, a tailor, his mother, Mary Ann Mason, aged 43, tailoress, and his younger sister, Kate Mason, aged 18. The parents were born in Ireland, which also fits the bill, but, interestingly, the birthplace of both children was entered as “US” (United States) and has been overwritten with “NY” (New York). However, it is not yet possible to confirm whether this census entry relates to the chessplayer. The same James Mason has not so far been identified in any other US censuses.

The story of James Mason’s birth in Kilkenny in 1849 has been widely embraced by chess writers, and they may well be right. However, caution is called for. It is difficult either to prove or disprove. There has been no corroboration from a primary source, such as a birth or baptism record, and no information about his early life and background in Kilkenny was ever given beyond a date of birth, even though he is said to have been 11 when he was next mentioned in the United States. His existence during those first years has taken on an almost mythical quality.

Leaving this New York census entry aside, there are other difficulties with attributing Irish birth to Mason. In the English census of 1881, the first after his arrival, the chessplayer’s place of birth was, similarly, entered as “America” (see National Archives, RG 11 590/90, page 14).

In the 1901 census, his place of birth was recorded as “Ireland, American citizen” (National Archives, RG 13 30, page 52). If that were correct, one would assume that he had been naturalized in the US. Searches so far for a naturalization record have proved negative. The only other way he could have been an American citizen was by birth.

P.W. Sergeant was evidently perplexed by Mason. On page 172 of A Century of British Chess he remarked:

“But James Mason was not an American, either by birth or, apparently, even by naturalisation, since in 1901-2 he played for Britain in the cable-matches. He is one of the most enigmatic characters in the history of British chess.”

Sergeant implies that American citizenship would have prevented him from playing for Britain. Yet American citizenship is precisely what he declared to the 1901 census; if it was not true, then it is hard to understand why he said it. Sergeant does not comment here on the extent to which birth in Ireland, as opposed to America, may have assisted his eligibility to represent Britain in international matches. He also made the point that, on his arrival in 1878, Mason was not received as one returning to Britain:

“... and, though he was, in a sense, like Bird, an exile returned, he was not recognised as connected with the British Isles. He was received as Mr Mason, the American master.”

James Mason was well liked and he has emerged with the reputation of an honest person. His alleged plea to Buckley (“Don’t split on me till I’m dead ...”), noted in your feature article Who Was R.J. Buckley?, entails an element of conspiracy, but chessplayers have, generally, sympathized with the circumstances. However, when considered in conjunction with that, the inconsistent information which he gave to censuses gives one cause to question how straightforward he was in the matter of nationality, and whether Irish birth was the truth.

One final point: that Mason was born in “New York city” was affirmed by the editors of the Columbia Chess Club Chronicle (who included S. Lipschütz) in the Editor’s Table on page 31 of the issue dated 23 July 1887:

“The St Paul Pioneer states that an American gentleman, greatly interested in chess, is endeavoring to arrange a match between Blackburne and James Mason, the strong American player, who is by far the finest native player since Paul Morphy’s time. Mason is still a young man. Born in New York city, he began life as a newsboy there. In later years he has pursued a journalistic career in London, where he has resided for nearly ten years.”

Conclusion:

Although it is widely accepted that James Mason was born in Ireland, there is also a significant amount of evidence that he was born in the United States. More information is needed before any firm conclusion can be safely drawn.’

(11908)

Page 58 of Womanhood, 1904 had a list of subscribers to a purse for James Mason and included, inaccurately, ‘John Ellis (inventor of Esperanto)’.

Diagram 10 on the inside front cover of the May 1959 Chess Review begins by quoting James Mason: ‘Every passed pawn is a potential queen.’

On page 130 of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice (London, 1894) Mason did not limit his remark to passed pawns:

‘Every pawn is a potential queen.’

(12070)

Latest update: 19 July 2025.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.