Edward Winter

See C.N. 11377 below.

The present article complements Analytical Diasaccord and Capablanca on Moscow, 1925, as well as pages 127-133 of our 1989 monograph on the Cuban.

***

How many brilliant attacking or defensive manoeuvres are lost to immortality because the game eventually petered out to a draw?

(83)

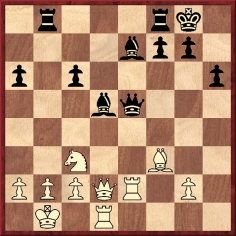

As a possible illustration of the point we gave Levenfish v Capablanca, Moscow, 28 November 1925, as published in Las Aperturas del Peón de Dama by Máximo Borrell (Barcelona, 1974). Borrell drew attention to a most ‘un-Capa-like’ king’s-side defence, and he gave 22...h4 two exclamation marks.

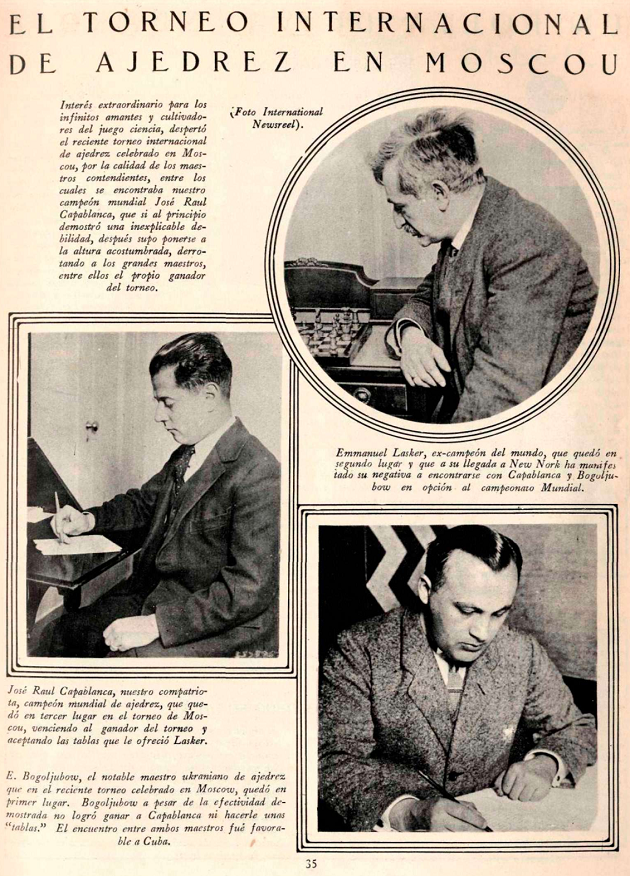

Armando Alonso Lorenzo (Prov. Ciego de Avila, Cuba) sends us a cutting from the Cuban newspaper Juventud Rebelde of 18 June 1987, a report on a forthcoming film about the life of Capablanca. Directed by Manuel Herrera, who was responsible for No hay sábado sin sol, it deals with important periods in his life, particularly the 1925 Moscow tournament. The work was conceived by Eliseo Alberto Diego, who wrote the script with Herrera. Assistance with scenes involving the Soviet Union was given by Dall Orlov. Capablanca is a co-production between the ICAIC in Havana and Gorki Studios in Moscow.

Capablanca is played by César Evora. Three apparently fictitious ladies provide the substantial romantic interest. The director declares: ‘I would define the film as a work of fiction based on actual events which draw it together. It is a key moment in the life of our great chessplayer: he could choose between continuing to base his play on his great talent or adopting a scientific method which would enable him to train and have suitable technique prepared for any occasion. But do not think that we intend to expose the public to repeated play at the board. The conflict is more concentrated on Capablanca’s own personality, with a kind of similarity between chess and life, in which people occupy a position which is comparable to that of pieces on the chessboard.’

Shooting was in three main parts. The first, starting on 23 March and lasting 50 days, was on location in Leningrad. The second began ‘a few weeks ago’ in Havana. The intention was then to return to the USSR to shoot ship scenes on the Black Sea, and also to film in Moscow (at the Metropol Hotel and in the Gorki Studios). The director hoped to start editing at the end of July, with the intention of having the film ready for the Festival of New Latin American Cinema in December.

(1484)

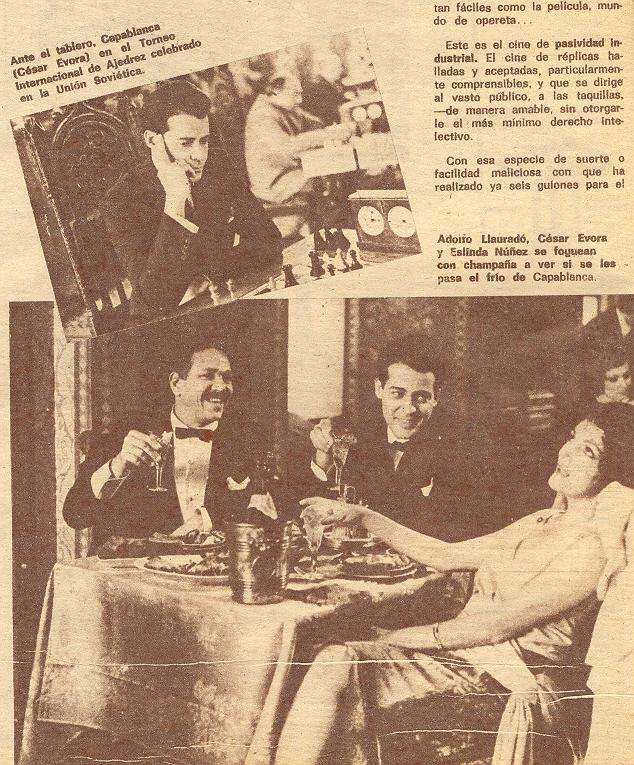

Below are two photographs from the 1987 film Capablanca starring César Evora in the title role, from page 10 of the Cuban magazine Bohemia, 26 February 1988:

(4303)

Below is a photograph reproduced from a full-page article about the film on page 9 of the Cuban newspaper Juventud Rebelde, 6 March 1988:

(11813)

Acknowledging a copy of Juventud Rebelde, 6 March 1988 from Armando Alonso Lorenzo, we noted in C.N. 1727 that the newspaper included much criticism of Manuel Herrera’s film, chiefly for lack of realism and superficiality.

Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) draws attention to a passage on page 5 of a book published by Kalnājs on the Chicago, 1973 tournament:

‘Carlos Torre, a young unknown chessplayer from distant exotic Mexico, was the greatest threat to the leading grandmasters in Moscow’s international tournament of 1925. Here is one example of his play. Because of Moscow’s freezing winter climate, after a short time illness felled Carlos Torre prematurely at the age of 29.’

Since Torre died in 1978 ... it is the Kalnājs book that felled him prematurely.

(2411)

A game from page 236 of the September 1957 BCM:

C. Chaurang (France) – B.J. Moore (England)

International Junior Team Tournament, The Hague, 15 July 1957

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 e6 7 Qd2 a6 8 O-O-O h6 9 Bf4 e5 10 Nxc6 bxc6 11 Bxe5 Bg4 12 Bxf6 Qxf6 13 Be2 Be6 14 f4 Be7 15 Rhe1 O-O 16 Bf3 Rab8 17 e5 dxe5 18 fxe5 Qh4 19 Ne4 Bd5 20 Kb1 Qxh2 21 Re2 Qxe5 22 Nc3

22…Rxb2+ 23 Kxb2 Rb8+ 24 Ka1 Ba3 25 Rxe5 Bb2+ 26 Kb1 Bxc3+ 27 Kc1 Bb2+ 28 Kb1 Bxe5+ 29 Kc1 Bb2+ 30 Kb1 Bc3+ 31 Kc1 Bxd2+ 32 White resigns.

On page 295 of the November 1957 BCM D.J. Morgan quoted W. Ritson Morry’s view in the Chess Supporter that this game surpassed Torre v Lasker, Moscow, 1925, for the following reasons:

‘(a) The pieces which enable the discovered check seesaw to be operated are not on the immediate scene as in the Torre game. (b) Two sacrifices, and not one, are necessary to make the plan work properly. (c) The quiet 24th move by the king’s bishop was not easy to foresee. (d) The operation extends over a much greater area of the board and is accomplished with much greater concealment of intention.’

(2900)

See also The Chess Seesaw.

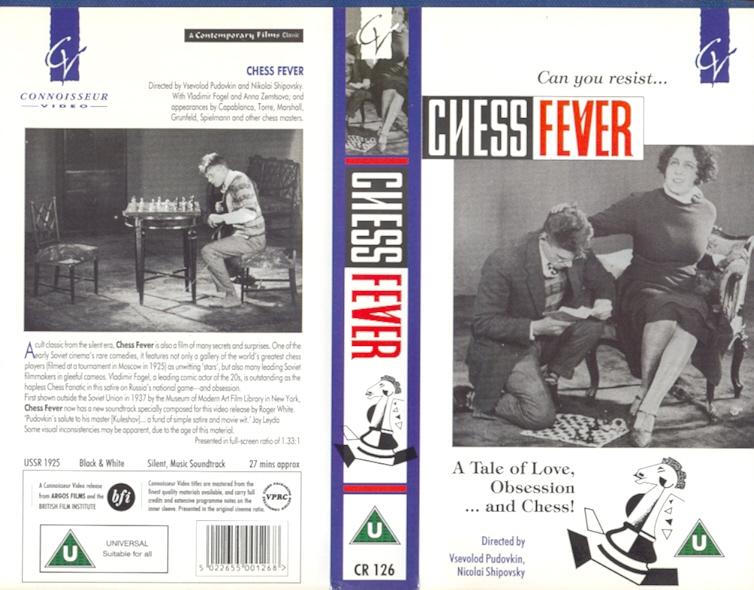

There used to be considerable ignorance about the 1925 Soviet film Chess Fever. ‘Did any reader ever see it?’ was the question posed on page 76 of CHESS, 5 December 1959. The same page contained the remark ‘Capablanca’s voice and figure were, we understand, “dubbed in”’, which Stewart Reuben corrected on page 283 of the 18 June 1960 issue by pointing out that the film was made before the advent of sound. But in what circumstances was the footage of Capablanca included? In the Chess Fever entry on pages 72-74 of Chess in the Movies (Davenport, 2005) Bob Basalla writes:

‘“Capa” was actually given “star” billing to goose audience attendance, even though most of his “acting” is just edited in to make him look like a participant. (The technique of Pudovkin’s mentor, Lev Kuleshov, by which unsuspecting people, in this instance the tournament participants and especially World Champ Capablanca, are filmed documentary or news reel style only to have their “parts” spliced into a different movie, a comedy in this case, defines the Kuleshov method.)’

Does contemporary Soviet literature (chess, cinema or general) offer any clarification of what occurred? Nowadays, Chess Fever is widely available for home viewing.

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) writes:

‘I very much doubt that what was said about inserting Capablanca in Chess Fever could be true. He interacts with the leading actress in the plot of the film, unlike the other masters, who are indeed merely sitting at their boards.’

This interaction is also mentioned in Bob Basalla’s book Chess in the Movies. As regards the other masters, it may be noted that the set of pairings filmed (e.g. Marshall v Torre and Réti v Yates) corresponds to no round of play at Moscow, 1925, and there is much artificial smiling for the camera. Another point is that the cinema entry in The Encyclopedia of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1977 and Harmondsworth, 1981) stated that the director, Pudovkin, utilized ‘such real personages as Capablanca and Lasker as figures in his short film’, whereas Basalla writes (justifiably, from our own viewing), ‘I can’t see where Emanuel Lasker appears at all’.

(3992)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides an extract from pages 174-175 of Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film by Jay Leyda (New York, 1960):

(10931)

Capablanca reported: ‘The tournament [Moscow, 1925] was played at the Hotel Metropole, a very spacious building ... It can comfortably take 1,200 people, yet it was crowded. There were always 1,500 to 2,000 spectators.’ (Interview in Diario de la Marina, 19 January 1926, page 17.)

Page 92 of the February 1926 BCM gave another participant’s estimate: ‘Yates says that there were about 5,000 visitors per day at the congress.’

Who invented the term ‘Capablanca fright’? The earliest occurrence we recall at present is on page 178 of the December 1925 American Chess Bulletin, in a note by C.S. Howell about 12 Qe1 in the Cuban’s win over Bohatirchuk, Moscow, 1925:

‘“Capablanca fright?” White’s queen side now becomes a weak mess.’

The above photograph (Moscow, 1925) comes from page 27 of Shakhmatnaya pravda by S. Tartakower (Leningrad, 1926). As mentioned in the caption, the person standing is N.V. Krylenko.

(4831)

Before proceeding, readers are invited to identify the five people in the above photograph. It was taken during a small tournament in Bladel, the Netherlands in 1969, and the opening 1 d4 f5 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Nh6, played in one of the games, was christened the Bladel Variation. The average age of the participants was nearly 70, and the photograph shows all four of them: M. Euwe is facing K. Opočenský, and in the top right-hand corner are H. Müller and S. Flohr. The Dutch Defence game was a 12-move draw between Flohr and Euwe. Standing next to the Dutchman is the widow of Richard Réti; the tournament commemorated the 40th anniversary of his death. The photograph comes from page 14 of CHESS, September 1969, which reported:

‘As an additional gesture, Réti’s widow has also been invited over from Moscow. She attended every round and watched all the games with great interest.’

Biographical information about her will be appreciated. On page 194 of the July 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung Hans Kmoch remarked that from the Moscow, 1925 tournament Réti brought back not only a ‘beauty prize’ for his game against Romanovsky but also a beautiful young Russian as his wife:

‘... Réti, der aus Moskau nicht nur den Schönheitspreis für seine Partie gegen Romanowski, sondern auch eine schöne junge Russin als Gattin mitgebracht hat, mit der er nun seine Hochzeitsreise unternimmt.’

On page 3 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess (London, 1954) Harry Golombek referred to Kmoch’s comment, and page 129 mentioned again the prize won by Réti for his game against Romanovsky. However, Golombek went astray on page 37 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966) by stating that Réti did not win such a prize in the Moscow, 1925 tournament. Referring to the opening ceremony of the Botvinnik v Tal world championship match in 1960 Golombek wrote:

‘One of the items this time was a prelude for pianoforte dedicated to Tal and Botvinnik. Afterwards I was introduced to the composer who, surprisingly enough, wasn’t a chessplayer. His connexion with the chess world was that his wife was the former Mrs Réti. Despite the passage of some 35 years since the remark was made, on looking at her I realized what was meant when it was said that Réti may not have won a beauty prize over the board at Moscow, 1925, but he had come away with one all the same. For this was the beautiful Russian girl whom he had met and married in Moscow that year.’

Can the name of Mrs Réti’s later husband be established (possibly from a souvenir programme for the opening ceremony of the 1960 match)?

(4912)

Michael Lorenz (Vienna) draws attention to the reference to Réti’s marriage on page 189 of Richard Réti šachový myslitel by Jan Kalendovský (Prague, 1989). Her maiden name was Rogneda Sergeievna Gorodetskaia, and she was the daughter of the Russian poet Sergei Gorodetsky (1884-1967). The couple met during the Moscow, 1925 tournament and married in Moscow on 28 May the following year (Réti’s 37th birthday). A footnote in the Czech book stated that in 1987 she was still alive, in Moscow.

Richard Réti

(4929)

There are two photographs of Réti’s wife on pages 29-33 of the Russian-language work Richard Réti by Anatoly Matsukevich (Moscow, 2005). See too C.N. 5041.

Regarding Bogoljubow v Capablanca, Bad Kissingen, 1928 Irving Chernev wrote on page 238 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960):

‘For Capablanca this victory must have been especially gratifying. It proved once again that Bogoljubow had been deluding himself when he made the statement, “There is nothing more to fear from the Capablanca technique”.’

Where did Bogoljubow make such a statement?

Efim Bogoljubow

(6047)

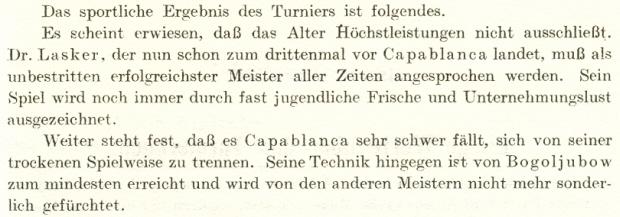

Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA) draws attention to this passage by Bogoljubow on page ix of his book on the Moscow, 1925 tournament:

Our correspondent’s translation:

‘The sporting result of the tournament is as follows. It has been shown that advanced age does not preclude the highest achievements. Dr Lasker, who for the third time finished ahead of Capablanca, must without question be considered the most successful master of all time. His play yet again is enterprising and almost youthfully fresh. Further, it is apparent that Capablanca finds it very difficult to separate himself from his dry style of play. His technique, on the other hand, has been at least equalled by Bogoljubow and is not especially feared by the other masters.’

(6052)

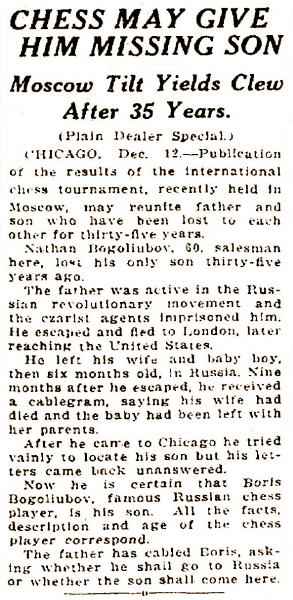

From Olimpiu G. Urcan comes this feature concerning ‘Boris Bogoliubov’ from page 9 of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, 13 December 1925:

(7275)

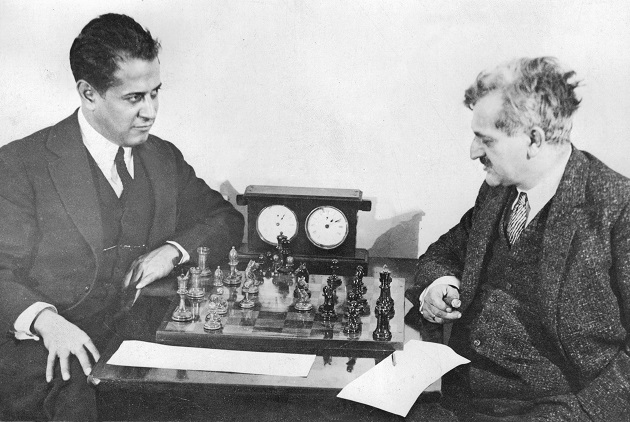

Further to this well-known photograph of Capablanca and Lasker in Moscow in 1925 (see, for instance, page 310 of Chess Facts and Fables), Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes a brief sequence of moving pictures of the two champions (at about 15:40:40). [Addition on 16 November 2012: the material is no longer available at the link indicated.]

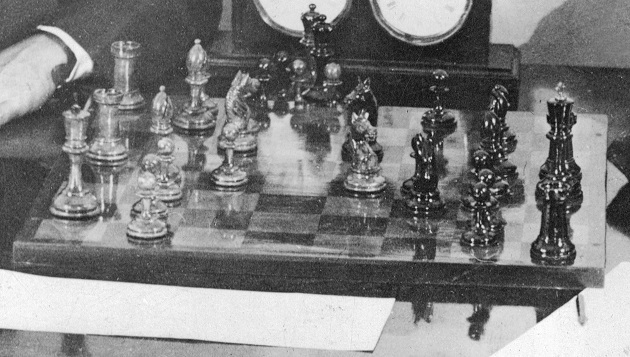

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has provided a fine copy of a well-known photograph (reference: AR_AGN_DDF/Consulta_INV: 259945) from Argentina’s Archivo General de la Nación, courtesy of the Ministerio del Interior, Obras Públicas y Vivienda:

Our correspondent comments that the board position shows a slight variation from their game in the first round of the 1925 Moscow tournament: 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 e3 e6 5 Nf3 Nbd7 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 c5 8 O-O a6 9 dxc5 Nxc5 10 Qxd8+ Kxd8 11 Rd1+ Ke8 12 Be2 Be7 13 b3 Bd7 14 Bb2 Rd8 15 Rd4 Bc6 16 Rxd8+ Kxd8 17 Rd1+ Bd7 (instead of 17...Kc7, as played by Lasker) 18 Ne5:

(10726)

See also A Fake Chess Photograph.

A different photograph from the same occasion is on page 318 of volume two (Berlin, 2020) of that outstanding series Emanuel Lasker edited by Richard Forster, Michael Negele and Raj Tischbierek, with this caption:

‘Capablanca and Lasker in a picture set up during the Moscow, 1925 tournament (one of several versions of the photograph). Their epic encounter in round 14 of the New York, 1924 tournament was not documented by any photographer.’

Page 164 of the co-authors’ third volume (Berlin, 2022) had a full-page, and full-length, photograph:

‘A picture showing the two champions in analysis has been reproduced (and doctored) in dozens if not hundreds of publications. This shot from the magazine Prozhektor offers a slightly different angle and includes many details missing from the better-known versions.’

We are looking for a high-quality version of the seldom-seen Moscow, 1925 group photograph, shown below in a small size for reference:

(12077)

The above comes from page 69 of part three of Max Euwe’s Theorie der Schach-Eröffnungen (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) and has been forwarded by Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy), who asks about Sozin’s exact involvement in the history of the move 11...Nxe5 (after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Nc3 e6 5 e3 Nbd7 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 b5 8 Bd3 a6 9 e4 c5 10 e5 cxd4 11 Nxb5). We note that on page 165 of Championship Chess (London, 1950) Botvinnik referred to 11...Nxe5 as ‘Sozin’s rejoinder to Blumenfeld’s plan (11 KtxKtP)’. Annotating a game against Reshevsky, Botvinnik wrote on page 274 of the September 1955 Chess Review regarding 11...Nxe5:

‘Black’s witty, clever and safe continuation was found by master B. Sozin 30 years ago.

See also page 280 of the September 1955 BCM. On page 139 of the September 1933 Schweizerische Schachzeitung Ernst Grünfeld referred to 11...Nxe5 as ‘le fameux coup indiqué par l’analyste russe Sosin’. An early game in which the move occurred was I. Rabinovich v B. Verlinsky, Moscow, 1925. See pages 157-158 of Bogoljubow’s tournament book. Readers’ assistance with tracing further information about Sozin and 11...Nxe5 will be appreciated.

(7813)

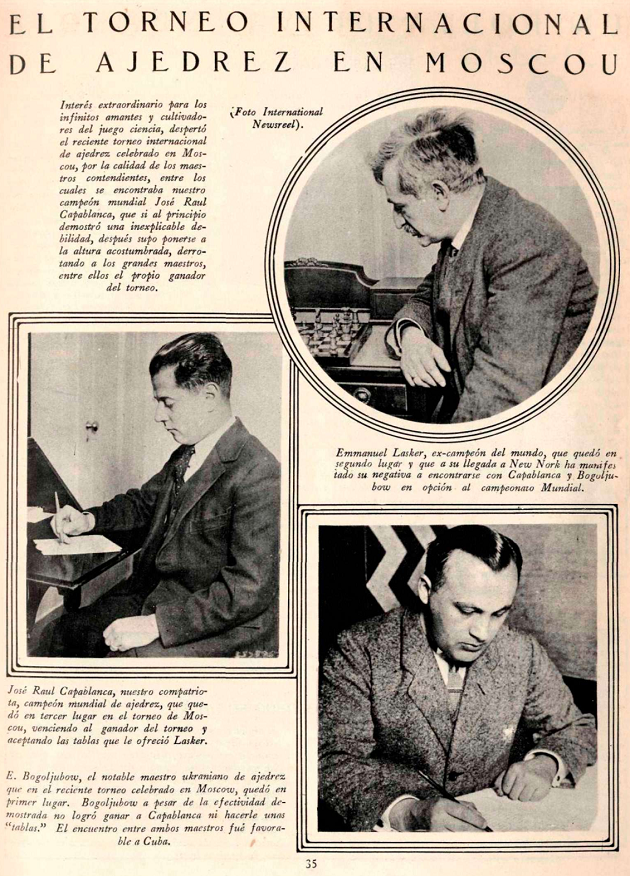

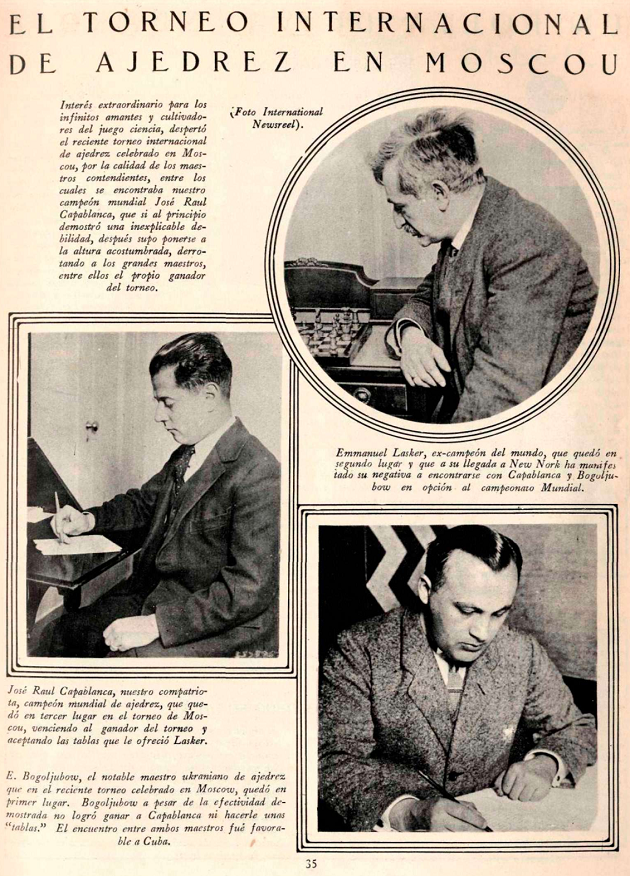

A feature from Social (February 1926, page 35) has been provided by Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba):

(11377)

On pages 185-188 of the April 1926 BCM J. Schumer annotated the game Capablanca v Ilyin-Genevsky, Moscow, 1925 with extracts from Thomas Hood’s poetical works. The material also appeared on pages 13-15 of Schumer’s book Chesslets (London, 1928.)

Olimpiu G. Urcan has provided this picture of Fritz Sämisch and Petr Romanovsky, from the Russ-Photo Archive (a Moscow photograph agency of the 1920s):

It may have been taken during Moscow, 1925, though it is without relevance to their game in the tournament.

(12174)

To the Chess

Notes main page.To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.