Edward Winter

Alexander Alekhine. See C.N. 10842 below.

The following non-exhaustive list of items about chess and music in older chess periodicals intentionally leaves aside the innumerable articles on Philidor.

‘Chess and Music. P.P. Sabouroff, who was once president of the Pan-Russian Chess Federation, and also of the Petrograd Chess Club, has composed a Love Symphony for big orchestra, which was played for the first time on 6 May in the “Concert Classique” at Monte Carlo and proved a great success.

The Scherzo (third part) of the symphony is called “Simultaneous Games of Chess”.’

Peter Petrovich Saburov

(Sabouroff), American Chess Bulletin, November 1911,

page 246

‘... chess has much to recommend it to the notice of practical musicians and composers. For instance, the mental alertness, the rapid decision, the almost instantaneous abandonment of a preconceived plan in order to counter-act an unexpected move on the part of an opponent or to profit by any observed peculiarity in the play of the lat[t]er, would be but familiar procedures or conditions to, let us say, organ recitalists accustomed as they are, or should be, to vary registration, tempo and even style to meet the exigencies or defects of a strange building or unfamiliar instrument.’

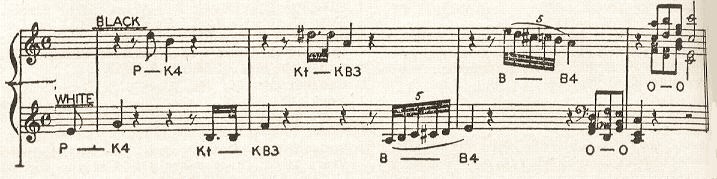

‘From The Road to Music by Nicolas Slonimsky (Dodd, Mead and Company) we find a curious bit of chessiana.

“Also in a humorous vein are such musical pieces as A Chess Game, in which chess moves are imitated by melodic intervals. The pawn moves two spaces, and the melody moves two degrees of the scale. The knight jumps obliquely, as knights do in chess, and the melody moves an augmented fourth up. When the bishop dashes off on a diagonal, the music imitates the move by a rapid scale passage. Play this piece for a chess expert, and the chances are he will name the moves without a slip.”’

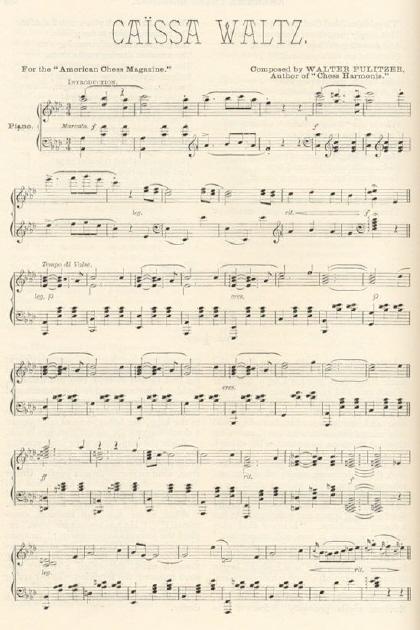

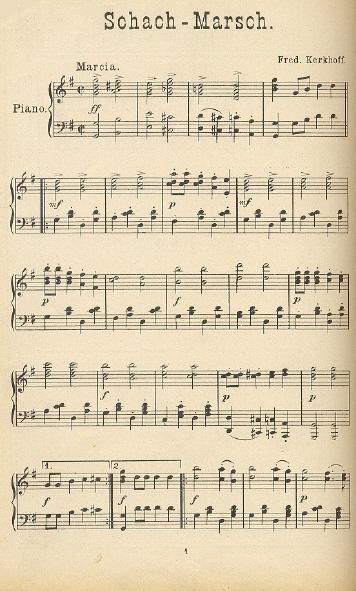

Finally, we mention that two musical scores (‘Schach-Marsch’ by F. Kerkhoff and ‘Schach-Walzer’ by C. Noack) took up 11 pages of the Barmen, 1905 tournament book. They were performed in Barmen on 16 August 1905, i.e. during a presentation of Richard Genée’s Der Seekadett. This operetta, which gave its name to the ‘Sea Cadet Mate’, began with a Prologue recited by Frau Adolf Keller attired as Caissa:

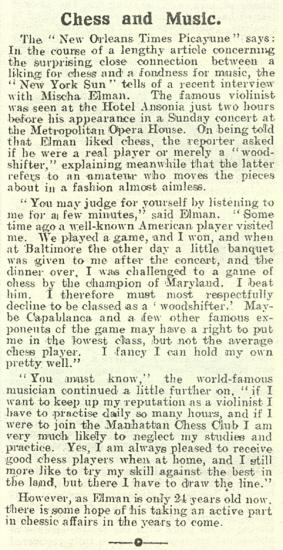

Regarding Mischa Elman, Moriz Rosenthal and other musicians, see pages 222-224 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951). Rosenthal was discussed too in C.N.s 6171 and 6184.

Below is a game lost by Louis Persinger to another expert violinist, David Oistrakh, which was published in Chess Life, March 1967, pages 67-68:

Louis Persinger David Oistrakh

Poznań, 6 December 1957

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 Nf6 2 e3 d5 3 f4 e6 4 Bd3 c5 5 c3 Be7 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 O-O Bd7 8 h3 Qc7 9 Ne5 Ne4 10 Qf3 f5 11 Bxe4 Nxe5 12 fxe5 dxe4 13 Qh5+ g6 14 Qe2 O-O 15 Nd2 a6 16 a4 Rf7 17 g3 Raf8 18 b3 cxd4 19 cxd4 Qc2 20 Qc4 Rc8 21 Qxc2 Rxc2 22 Nc4 b5 23 Nb6 Bc6 24 Rf2 Rc3 25 Rb2 Bd8 26 Bd2 Rd3 27 axb5 Bxb5 28 Nc4 Be7 29 Kf2 g5 30 Nd6 Bxd6 31 exd6 Rd7 32 Bb4 f4 33 gxf4 gxf4 34 exf4 Rf3+ 35 Kg2 Rg7+ 36 Kh2 e3 37 Be1 Bf1 38 Kh1 Rxh3+ 39 Rh2 Bg2+ 40 Kg1 Bc6+ 41 White resigns.

(2691)

A game-score that we are seeking is Persinger’s victory over C.A. Mills in the Metropolitan Chess League of New York in 1943. Page 33 of the March-April 1943 American Chess Bulletin reported that it had won him a special prize donated by Leonard B. Meyer.

(2763)

Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) has kindly provided the game-score requested:

C.A. Mills – Louis Persinger

New York, 1943

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Nf3 O-O 6 e3 c6 7 Qc2 Nbd7 8 Rc1 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Nd5 10 Bxe7 Qxe7 11 Bd3 g6 12 Nxd5 exd5 13 h4 Nf6 14 Ne5 Ng4 15 Nxg4 Bxg4 16 Be2 Bf5 17 Qc5 Qe6 18 h5 Bg4 19 f3 Bxh5 20 g4 Bxg4 21 fxg4 Qxe3 22 Rc3 Qe4 23 Rch3 Rfe8 24 R1h2 Qb1+ 25 Kf2 Qxb2 26 Kf3 Qd2 27 Qa3 Re4 28 Qd3 Qf4+ 29 Kg2 Rae8 30 Bf3 Rxd4 31 Qc3 Rd2+ 32 Qxd2 Qxd2+ 33 Kg3 Qe1+ 34 Kg2 Re2+ 35 Bxe2 Qxe2+ 36 Kg1 Qxg4+ 37 Kf2 h5 38 Rg3 Qf4+ 39 Kg2 h4 40 Rf3 Qe4 41 Rh3 g5 42 Kf1 g4 43 Re3 Qf4+ 44 White resigns.

Sources: New York Post, 5 June 1943 and the Christian Science Monitor, 12 June 1943, page 15. The following year the game was given in the American Chess Bulletin (September-October 1944 issue, page 115).

(2767)

Which musical composer wrote, in consecutive years, two entirely different pieces which were both entitled The Chess Game?

(2978)

The composer was Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957). They were featured in the Errol Flynn films The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) and The Sea Hawk (1940). Numerous recordings of the scores are available, the most complete ones apparently being from Varese Sarabande (VSD-5696 and VSD-47304 respectively).

(2986)

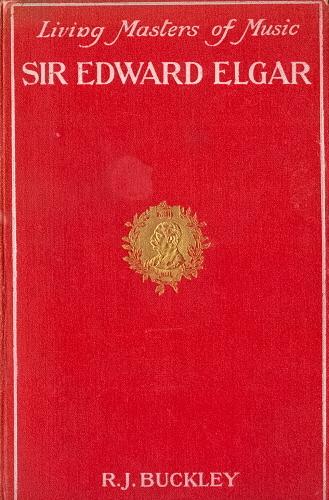

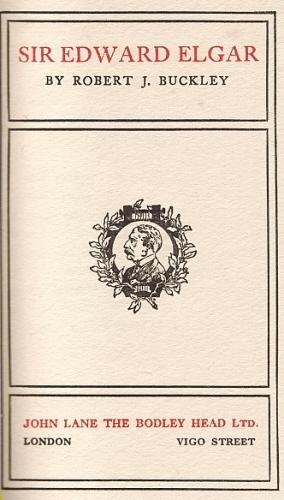

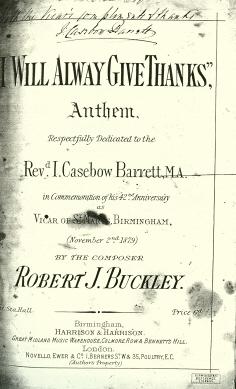

An extract from Who Was R.J. Buckley?:

Another great interest of Buckley’s was music, and in 1904 he wrote a biography of Sir Edward Elgar, whom he knew personally. From page 29:

‘It was in the “Black Knight” period [i.e. circa 1893] that I first visited the composer at “Forli”, a charming cottage under the shadow of the Malvern Hills …’

His chess writing continued but was seldom seen beyond local newspapers, an exception being an article entitled ‘Blackburne and Winawer’ on pages 43-44 of the February 1923 American Chess Bulletin.

The Evening Despatch of 24 August 1935 (page 6) reported:

‘Now Mr Buckley, who retired from active work in 1926, and has continued the “Arley Lanes” [his non-musical writings] mainly as a means of keeping in touch with the papers he has served during the greater part of his life, feels that in his 89th year he must break this last thread.

A severe fall some months ago placed him under doctor’s orders, and it is considered advisable that in future he should devote himself entirely to the books and music which still form his principal interests.’

A very rare mention of him in the BCM came on page 417 of the August 1937 issue:

‘Information having been received at the Blackpool Chess Congress that Robert J. Buckley, of Moseley, Birmingham, would be 90 years of age on 14 July, and, in consequence, a birthday greeting card signed by one or two officials and others was sent to him. Years ago Mr Buckley was particularly well known. He was, for a very long period, chess editor of the Manchester City News, and interested in chess in various ways.’

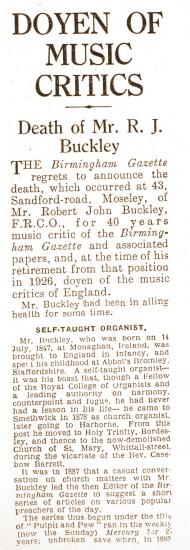

As far as we are aware, no chess periodical recorded Buckley’s subsequent demise. The Birmingham Gazette of 27 December 1938 (page 4) reported under the heading ‘Doyen of Music Critics – Death of Mr R.J. Buckley’:

‘The Birmingham Gazette regrets to announce the death, which occurred at 43 Sandford-road, Moseley, of Mr Robert John Buckley, FRCO, for 40 years music critic of the Birmingham Gazette and associated papers and, at the time of his retirement from that position in 1926, doyen of the music critics of England.

Mr Buckley had been in ailing health for some time.

Mr Buckley, who was born on 14 July 1847 at Monaghan, Ireland, was brought to England in infancy, and spent his childhood at Abbot’s Bromley, Staffordshire. A self-taught organist – it was his boast that, though a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists and a leading authority on harmony, counterpoint and fugue, he had never had a lesson in his life – he came to Smethwick in 1878 as church organist, later going to Harborne …

…In 1893 Mr Buckley was sent to Ireland as special correspondent of the Gazette during the Gladstone Home Rule troubles. The brilliant series of articles he sent back during six months, and which powerfully influenced national politics, made his reputation.

…He was also a prolific contributor of special articles to newspapers all over the country and conducted chess columns at various times in Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield and Liverpool journals.

In 1933, his resignation from the chess editorship of the Manchester City News was signalized by a presentation from solvers of many years’ standing – many of whom had never met Mr Buckley in person.

In addition, he was the author of a volume of short stories, three novels and the first – and still standard – life of Sir Edward Elgar, who was an intimate personal friend.’

(3249)

There was a reference to W.O. Fiske on page 9 of Willard Fiske Life and Correspondence by H.S. White (New York, 1925):

‘Some mention should be made here of Mr Fiske’s younger brother, William Orville, who was born in 1835 and died in 1909. He had the musical gifts which his elder brother missed and the lack of which he often mourned. A handsome man in his prime, with golden hair and beard. Besides teaching the piano, the organ and singing, and officiating as a musical director, he was for many years the organist of St Mary’s Church in Syracuse, and married the niece of its pastor, Father O’Hara, herself a musician, and soprano in the choir. Earlier, Mr Fiske had held a professorship of music in the Fort Plain Seminary. His musical compositions were many and varied, and of artistic worth. In 1872 Oliver Ditson published a work edited by Mr Fiske entitled The Offertorium, a collection of music for the services of the Catholic Church, comprising masses, vespers, anthems, etc. Mr Fiske himself composed much sacred music, but did not disdain the lighter forms of composition, including marches, waltzes, galops, and other pieces for the piano, as well as songs and choruses. Many of Professor Fiske’s Psi Upsilon verses were set to music by his gifted brother.

William Fiske was a chess enthusiast too, and for a while edited a chess column in the Syracuse Standard, at the time when his brother was editing the New York Chess Monthly; and he also won the first prize at a chess tournament in Syracuse. In E.B. Cook’s great collection of chess problems (New York, 1868), 18 specimens by W.O. Fiske are included, comprising mates in two, three, four and seven moves.

The Boston Waverly Magazine published in its earlier years many of William Fiske’s musical compositions. In Vol. XIV (1857) appeared a “Chess Polka” and in Vol. XVIII (1859) a “Caissa Quickstep”, both inscribed to D.W. Fiske, who is described in the latter as “Editor of the New York Chess Monthly”. The name of the author of these two productions was given as “Guglielmo Orville”, evidently an Italianized pseudonym of the fraternal composer.’

(3563)

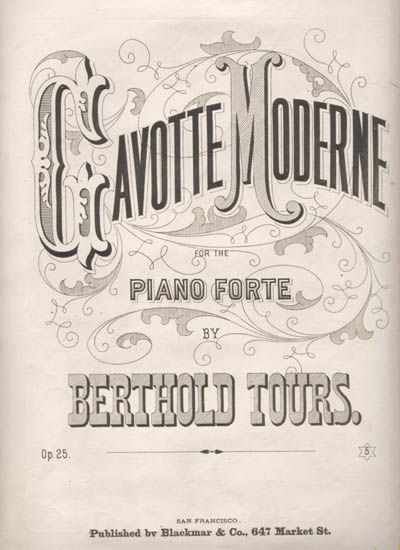

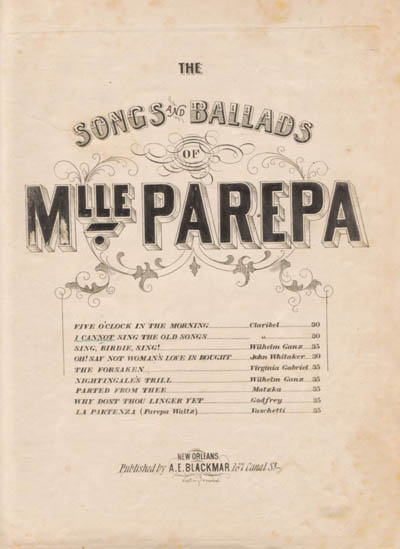

From pages 8-9 of Blackmar-Diemer Gambit edited by K. Smith and J. Jacobs (Chess Digest, Dallas, 1977):

‘Blackmar himself seems the epitome of the Southern gentleman: Born on 30 May 1826 in Bennington, Vermont, he later moved to Jackson, Louisiana, where by 1845 he was a Professor of Music at Centenary College. In 1856, Blackmar opened the first piano and music store in Jackson, Mississippi. Four years later, in 1860, he founded together with his brother a music publishing house in New Orleans. There, Blackmar arranged and/or published a number of famous songs of the Confederacy, among them The Bonnie Blue Flag, The Dixie War Song and The Southern Marseillaise. One of his own compositions later became a part of the musical score to the Clark Gable-Vivien Leigh film version of Gone with the Wind. Blackmar was also an able, enthusiastic chessplayer and a charter member of the Chess, Checker and Whist Club of New Orleans.’

In C.N. 2063 (see pages 153-154 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) Gary Lane, who was writing his own monograph on the Blackmar-Diemer Gambit, asked whether the claim about Gone with the Wind was true. As indicated in C.N. 2119, we could provide no details, even after contacting the Chess Digest editor, Ken Smith. In reply to our enquiry about the source of the information in his 1977 book Mr Smith replied, ‘Don’t remember’, ‘All information I had was given’ and, even more disconcertingly, ‘I don’t know what book this is. Anyway I have no copy’.

Can readers supply any solid information? All we can add for now is that our collection contains two (undated) musical scores: Gavotte Moderne (published by Blackmar & Co., 647 Market St., San Francisco) and The Songs and Ballads of Mlle Parepa (published by A.E. Blackmar, 167 Canal Street, New Orleans):

(3753)

We have now come across an earlier reference to A.E. Blackmar and Gone with the Wind, on page 3 of Discover The Blackmar-Diemer Gambit, volume 1 by Anders Tejler (Dallas, 1971), a book for which Ken Smith was billed as the editor:

‘Armand Edward Blackmar was born in Bennington, Vt. on 30 May 1826. By 1845 he was Professor of Music at Centennary [sic] College, Jackson, La. In 1856 he founded the first piano and music store in Jackson, Miss. By 1860 he and his brother opened a music publishing house in New Orleans, La. Here was published a famous song of the Confederacy: The Bonnie Blue Flag. Blackmar arranged the music for various songs, including the Dixie War Song and the Southern Marseillaise. When New Orleans was taken in 1862, Blackmar remained in the city; his brother, H.C. Blackmar, continued publishing patriotic music for the Confederacy in Augusta, Ga. At the end of the Civil War, the music house of Blackmar was confiscated and he was subjected to a heavy fine. One of Blackmar’s musical compositions was heard in the music to the film Gone with the Wind. Blackmar died in New Orleans on 28 October 1888. He was not only an eminent pianist but also a very good violinist. He was a chess expert, a charter member of the Chess, Checkers and Whist Club of New Orleans.’

Can these statements (similar, but not identical, to what was quoted in C.N. 3753) be corroborated?

(3800)

C.N.s 3753 and 3800 discussed a claim that Armand Edward Blackmar composed music which was included in the film Gone with the Wind. Now Djordje Petrović (Belgrade) draws attention to an article ‘Songs of the Civil War’ by Charles Hamm. Without providing the details sought, it offers interesting background information, mentioning Gone with the Wind and Blackmar.

(5097)

See too Chess Jottings.

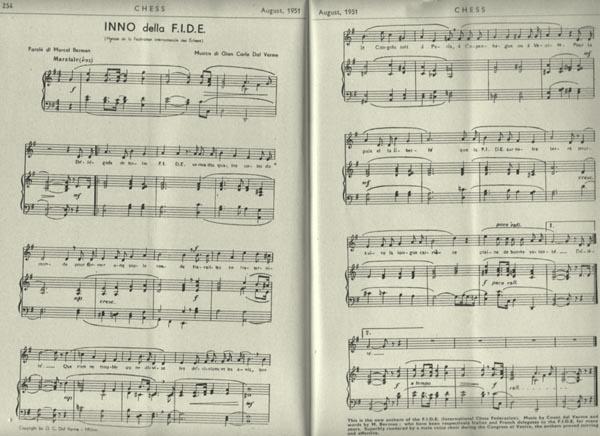

Pages 254-255 of CHESS, August 1951 reproduced the score of the FIDE Anthem, with music by Count dal Verme (1908-1985) and words by Marcel Berman (1895-1960).

(3789)

In an article on pages 209-210 of Chess Life, July 1961 the violinist Louis Persinger wrote:

‘I do believe that musicians have had a very special hypnotic fascination for the 32 little figures and have always been very willing slaves to those little characters’ inexhaustible intrigues and pranks.’

Regarding Persinger (and David Oistrakh) see page 129 of A Chess Omnibus. C.N. 3722 reproduced Persinger’s extensive inscription in one of our copies of The Golden Treasury of Chess by Francis J. Wellmuth, and here we add that on the first page of the Index of Players Persinger wrote ‘I’ve played against – ’ and then added ticks alongside these names in the index: W. Adams, Alekhine, Battell, S. Bernstein, Borochow, Capablanca, Chernev, Dake, Denker, Donovan, Fine, Fish, Fonaroff, Fulop, Grabill, Hanauer, Helms, Hidalgo, Horowitz, Kashdan, Koltanowski, Korpanty, Ed. Lasker, Em. Lasker, Marshall, Platz, Polland, Reinfeld, Reshevsky, H. Steiner, Tenner, Testa, Ulvestad and Woskoff.

From page 97 of Chess World, May 1958:

‘Nearly every one of the world’s leading violinists has been a chessplayer, and indeed, a majority of violinists of any note at all.

Kreisler always carried a travelling chess set for playing over interesting games. Go through a list of the great ones from Kreisler to Oistrakh and we doubt if you can name one non-chessplayer. As for Oistrakh, he is a first-category player in the USSR.’

Yehudi Menuhin’s enthusiasm for chess has been widely reported, our first reference being page 250 of the November 1944 BCM, which gave one of his three games against Aird Thomson. In the photograph below Menuhin is watching a game between Oistrakh (left) and Persinger:

Mischa Elman’s acquaintance with Edward Lasker was mentioned on pages 181-182 of A Chess Omnibus, and below is a photograph of Elman from page 302 of The Strand Magazine, September 1906:

(3912)

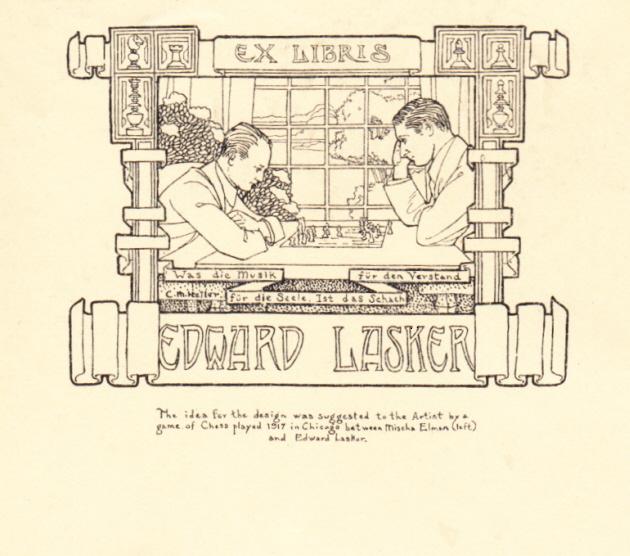

Edward Lasker’s bookplate was discussed in C.N. 2524 (see pages 181-182 of A Chess Omnibus), and below is one of the specimens in our collection, in the 1920 volume of Deutsches Wochenschach. The artist is named as ‘C.M. Heller’ [see C.N. 7886 for further details].

As mentioned in the earlier C.N. item, the photograph on which the illustration is based (Mischa Elman in play against Lasker) was published on page 27 of the February 1918 American Chess Bulletin:

(7886)

Persinger’s score-sheet of a loss to Capablanca in 1936 was added on 17 June 2024 to José Raúl Capablanca Miscellanea.

An article ‘Chess and Music’ by D.G. McIntyre was published in the March 1958 South African Chessplayer and reproduced on pages 154-155 of the October 1984 issue.

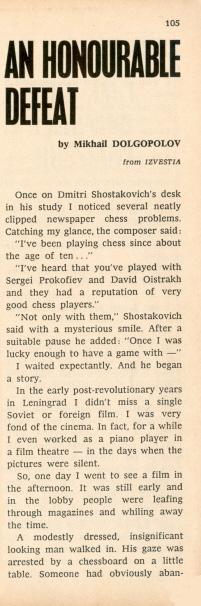

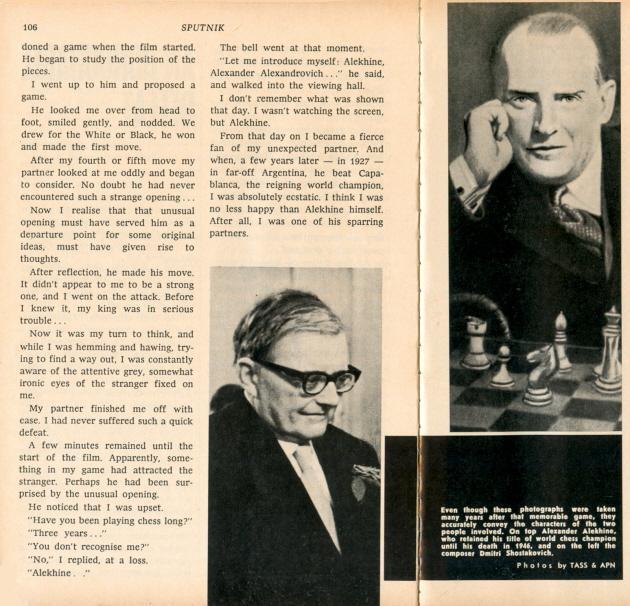

From pages 109-110 of Shostakovich A Life by Laurel E. Fay (Oxford, 2000):

‘Chess was chiefly a youthful infatuation; although he followed match play, he was never as serious a competitor as Prokofiev or David Oistrakh. In old age one of the favourite yarns he liked to retell was how, as a callow teenager, he had challenged and lost to Alexander Alekhine, something which could have taken place only before the future world champion left Russia for good in the spring of 1921.’

The source for this information is given on page 310:

‘M. Dolgopolov, “Budem znakomï – Alekhin ...”, Izvestiya, 17 August 1974, 5. Among others who recall hearing the composer recount versions of this story are Yevgeniy Dolmatovsky and Mstislav Rostropovich.’

A photograph of Shostakovich at the chessboard was given on page 354 of the November 1946 BCM:

(6654)

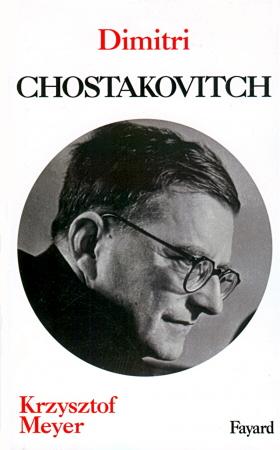

Marcelo Sibille (Montevideo, Uruguay) mentions that a longer account of the meeting between Shostakovich and Alekhine is to be found on pages 396-397 of another biography, published in 1997: Shostakovich Su vida, su obra, su época by Krzysztof Meyer, the source specified being an article by M. Dolgopolov in the 6/1975 issue of Sputnik.

We see no reference to Alekhine in an earlier edition of Meyer’s book, in Polish, Szostakowicz (Cracow, 1973), but the story can be found in the later editions in French and German: on pages 476-477 of Dimitri Chostakovitch (Paris, 1994) and pages 477-478 of Schostakowitsch Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit (Mainz, 2008).

No English translation of Meyer’s book is known to us, but we have procured a copy of the English edition of the June 1975 Sputnik (‘Digest of Soviet Press’). Below is the article by Mikhail Dolgopolov on Shostakovich and Alekhine, from pages 105-107:

(7079)

On pages 32-33 of the 5/2004 New in Chess Boris Spassky mentioned in an interview that at one time Enrico Caruso’s entourage included Boris Kostić.

Kostić took up residence in the United States in the first half of 1915, as reported on page 108 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin. His contact with Caruso was related on pages 34-35 of Ambasador Šaha by D. Bućan, P. Trifunović and A. Božić (Belgrade, 1966) and on pages 33-35 of Ambasador Šaha by D. Bućan (Novi Sad, 1987), and we shall be grateful if a reader can assist us in extracting the hard facts from those two accounts.

Neither book gave any games played between Kostić and Caruso, but on pages 93-94 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978) A. Soltis wrote:

‘One of the most aggressive players in the musical world was Enrico Caruso, who took the game seriously enough to study under Boris Kostić, the first great Yugoslav player. Here is one of their many skittles or offhand games with the mighty tenor playing Black.’

The moves, presented with the customary Soltis sourcelessness, were: 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Nbd7 5 Bg5 Bb4 6 e3 c5 7 Qc2 Qa5 8 Bxf6 Nxf6 9 Nd2 cxd4 10 exd4 O-O 11 a3 e5 12 dxe5 d4 13 Nb5 a6 14 exf6 Re8+ 15 Kd1 axb5 16 fxg7 Bxd2 17 Qxd2 Qa4+ 18 Kc1 bxc4 19 Be2 c3 20 Qd1 Qa5 21 Bd3 cxb2+ 22 Kxb2 Qc3+ 23 Kb1 Re6 24 Bxh7+ Kxh7 25 White resigns.

No place or date was stipulated, but when B. Pandolfini gave the conclusion on page 106 of Treasure Chess (New York, 2007) he put ‘1918’. In some databases (as well as on page 55 of CHESS, September 2004) ‘New York, 1923’ is specified – even though Caruso died in 1921.

(6951)

We add that on page 18 of the November-December 1996 issue of Chess Horizons (acknowledgement: Cleveland Public Library) Josef Vatnikov gave the game, stating, without evidence, that it was ‘played in New York in 1914’.

After just five words Vatnikov deployed ‘once’:

‘The great singer Enrico Caruso once said: “My favorite opening, playing Black, was the Philidor’s Defense.” In due time the famous Italian tenor played a lot of games with the Yugoslav grandmaster Bora Kostic, who was his chess trainer. “Caruso liked chess very much”, said Kostich, “I appreciated his chess ability. He could be on the offensive perfectly. Probably, many chess masters would envy his brilliant combinations.”’

There is no indication as to where any of this came from.

(12108)

The above photograph was on the front cover of the November 1944 Chess Review, with the following note on page 1:

‘Paul Whiteman, King of Jazz, wields his famous baton in defense of his king, attacked by Chess Review Postalite Leo Kahn, first violinist of the Whiteman orchestra. Looking on are violinist Sylvan Shulman (pipe in mouth) and viola player Ralph Hersh. These and other members of the orchestra are ardent chess fans and play during intermissions. This striking pose was taken at a rehearsal for the Blue Network’s Radio Hall of Fame program.’

(7454)

Page 185 of the July-August 1963 Chess Life had this news item in its coverage of the Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Los Angeles:

‘Most commotion of the tournament to date was caused when Frank Sinatra and Mike Romanoff walked in. Tigran Petrosian temporarily lost his title as most-stared-at individual.

The City of Hope was holding a convention at the hotel, and some of the ladies spotted Sinatra. Result – a rush to the playing room that was halted by some fast blocking on the part of our officials.’

A photograph of Sinatra with Walter Browne (and with the time-honoured ‘board problem’) was published on page 24 of Chess Life, May 1982:

(7466)

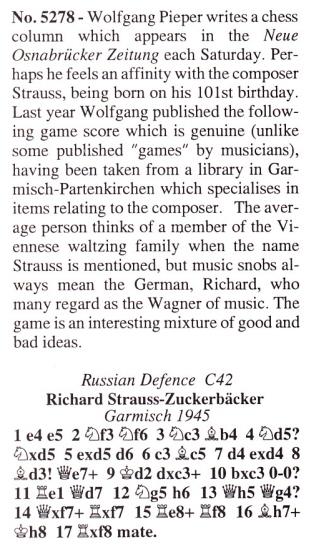

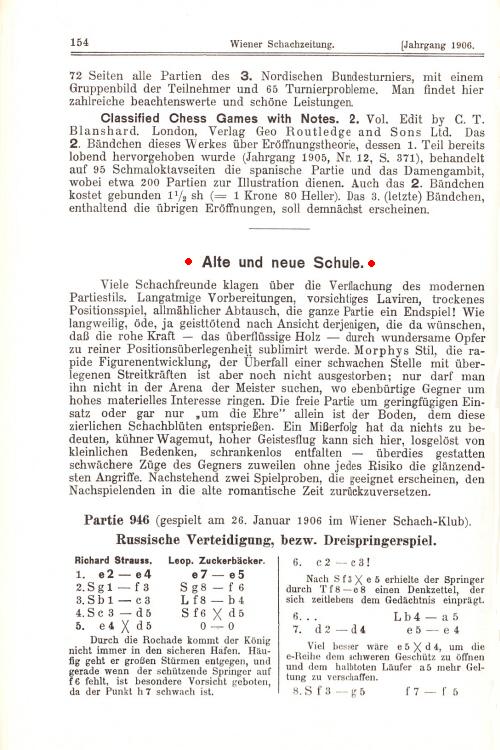

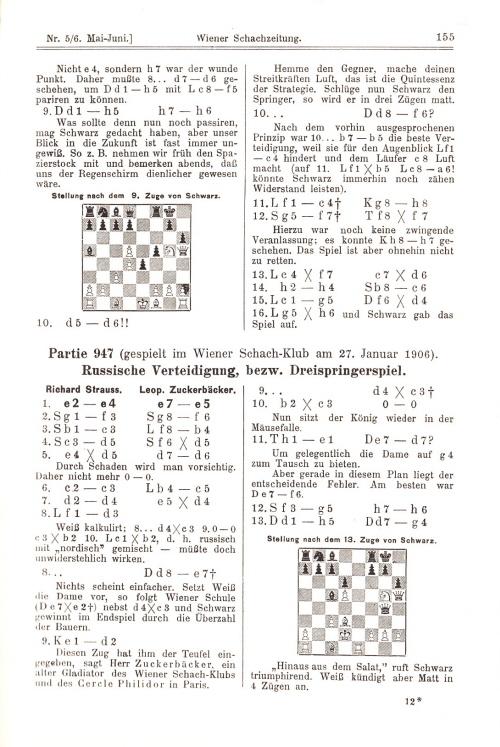

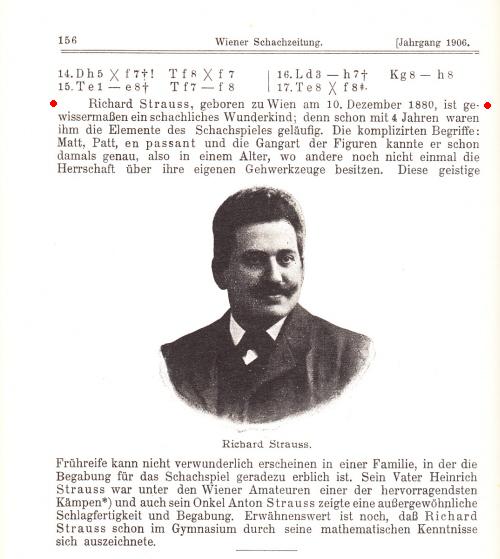

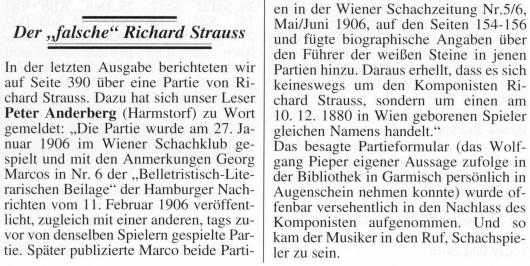

On pages 185-186 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978) A. Soltis attributed to the composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) a 17-move win over ‘Zukkerbrekker’ (Vienna, 1906). Then there was this item by K. Whyld on page 108 of the February 1996 BCM:

In fact, the game was one of two played against Leopold Zuckerbäcker by another Richard Strauss (born in Vienna in 1880) which were published on pages 154-156 of the Wiener Schachzeitung, May-June 1906:

(7667)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) reports that both of the Strauss v Zuckerbäcker games had been published by Georg Marco in his column on page 4 of the supplement to Hamburger Nachrichten, 11 February 1906:

Our correspondent mentions too that the ‘Garmisch, 1945’ claim was made in an unsigned item ‘Richard Strauss war Schachspieler’ on page 390 of the 14/2000 Schach Magazin 64 and that in the following issue (page 420) he had this correction published:

(7676)

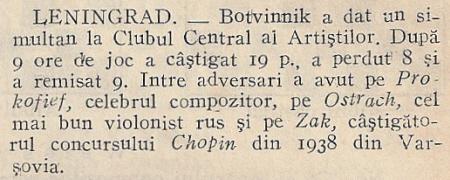

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) draws attention to a news item on page 164 of the Revista Română de Şah, 24 August 1939:

It states that Botvinnik gave a simultaneous exhibition at the Central Artists’ Club in Leningrad, scoring, after nine hours’ play, +19 –8 =9, and that his opponents included Prokofiev, Oistrakh and Zak.

Our correspondent writes:

‘What is known about the chess interest of Yakov Zak (1913-76), the winner of the 1937 Warsaw Chopin Competition? (The date 1938 in the Romanian magazine is incorrect.) He was one of the great names in Soviet piano performing and teaching and was famous for his performances of Prokofiev’s music.

Regarding the photograph in your feature article Sergei Prokofiev and Chess, the girl watching Oistrakh and Prokofiev, Elizaveta (Liza) Gilels, was the sister of the pianist Emil Gilels, the wife of the violinist Leonid Kogan, and the mother of the violinist and conductor Pavel Kogan. She herself was an accomplished violinist.’

(7726)

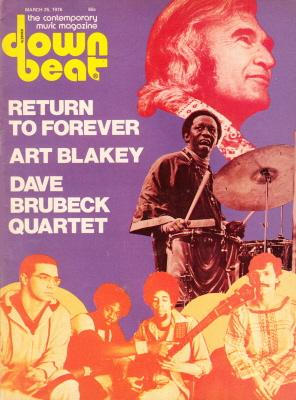

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) observes that a number of websites describe the jazz musician Thelonious Monk (1917-82) as ‘excellent at both chess and checkers’, the source specified being an article by John B. Litweiler, ‘Art Blakey: Bu’s Delights and Laments’.

We have found the magazine containing the article (down beat, 25 March 1976, pages 15-17 and page 44), but there is only one brief reference to chess, on page 15:

‘Art Blakey on Thelonious Monk: “I have yet to meet the man who can beat him at chess, or even checkers, or ping-pong.’”

(7847)

Paul Herzman (Brooklyn, NY, USA) quotes from page 138 of Don Andrés and Paquita The Life of Segovia in Montevideo (Milwaukee, 2012):

‘[On 19 May 1936] they had tea with composer Sergei Prokofiev, his wife, and the great Cuban chess player José Raúl Capablanca. Our two artists shared one of the other legs of the tour through the Soviet Union with Capablanca, whose second wife, Olga Chagodaev, was Russian ... [Capablanca married her in 1938.]

[After 15 June 1936] they went to Kiev. In the Ukrainian capital they again met Capablanca, with whom they shared several walks; they also attended one of his chess matches.’

Capablanca referred to Segovia on pages 13-14 of Last Lectures (New York, 1966):

‘Several years ago, in the Russian city of Kiev, I ran across Andrés Segovia, the great Spanish guitarist. We had known each other for some time; he as a lover of chess, and I as a lover of music! He was to give a concert and I a simultaneous exhibition. Both of these events were to take place in the great concert hall of Kiev, and naturally each of us invited the other to his performance. The simultaneous exhibition had been arranged for 30 students, boys and girls between ten and 16 years of age. Segovia, his wife and I arrived in the hall in due course, and I noted Segovia’s amazement at the spectacle which met his eyes. The huge hall was completely filled, and its balcony held more than a thousand girls who had come to watch the play. All were students and had learned to play chess in their respective schools. On the stage 30 boys and girls had been seated in a rectangle as is customary in such exhibitions. Most of them were boys, all of them ready to do battle with me. In each corner there had been placed a particularly strong adversary. In back of the players there was a crowd of boys and girls with their teachers and in back of them the guests. It was truly, as Segovia said, a phenomenal spectacle. There were at least three thousand people in the hall, almost all of them children.’

(7893)

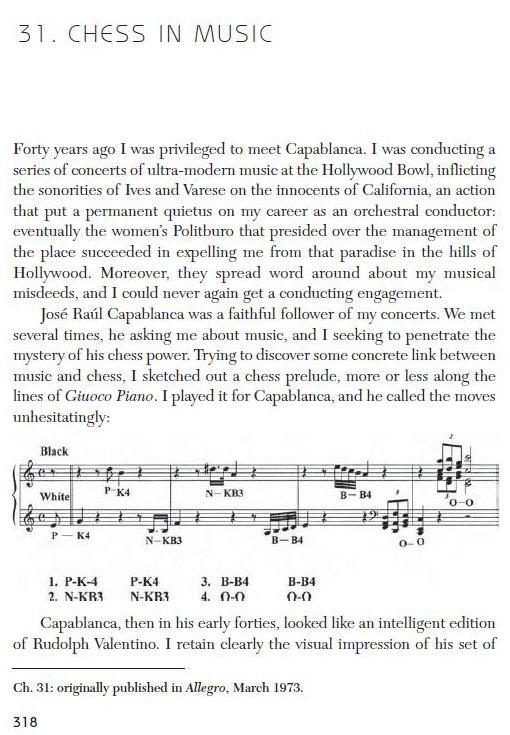

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to chapter 31 (pages 318-322) of volume four of Nicolas Slonimsky: Writings on Music (New York and London, 2005).

The chapter also includes a discussion of Prokofiev.

(7940)

Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands) points out the score and text of a march written in honour of Max Euwe.

(8560)

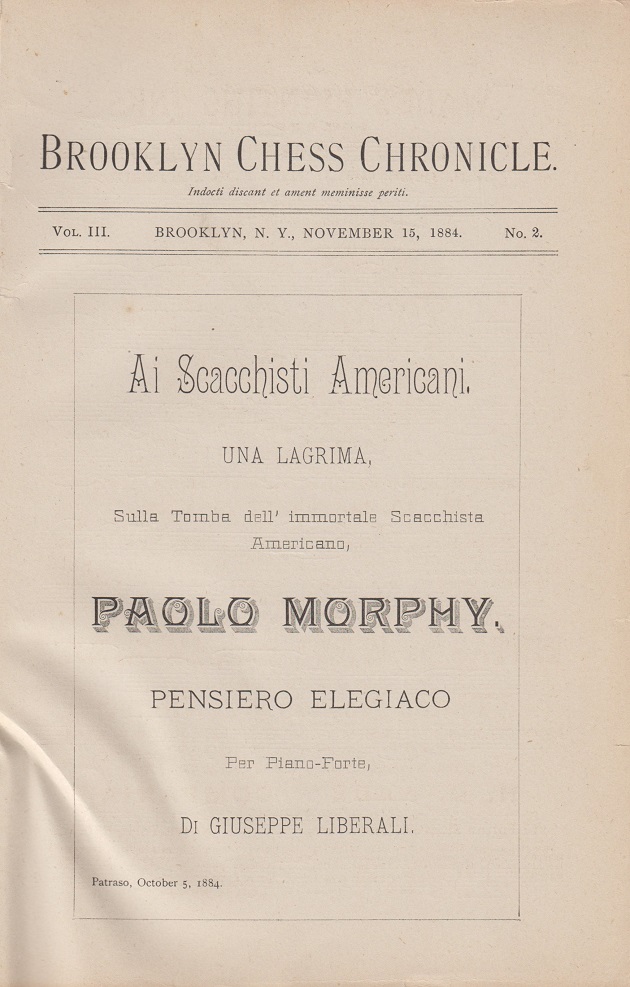

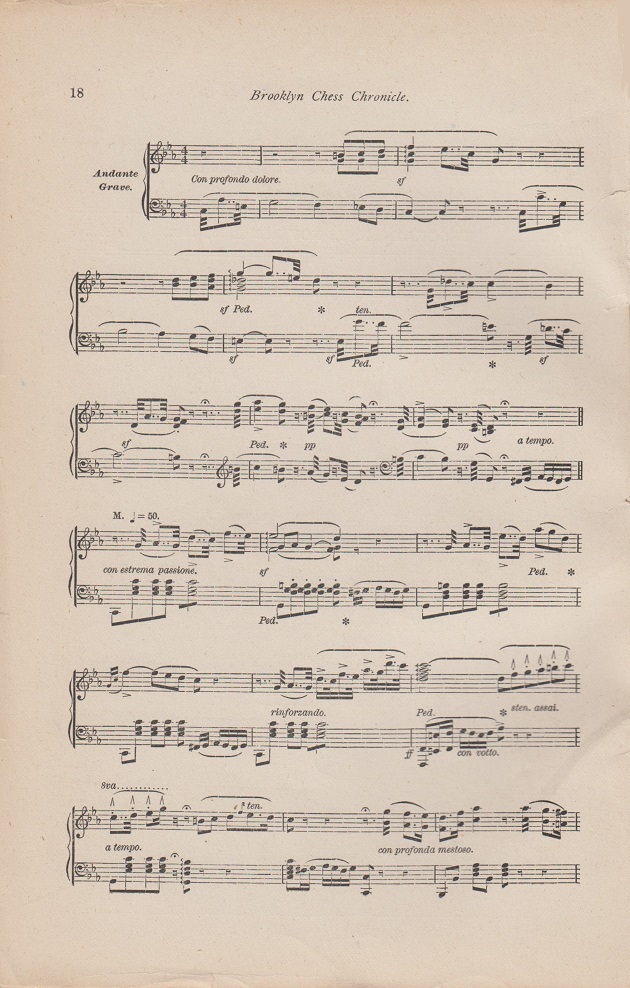

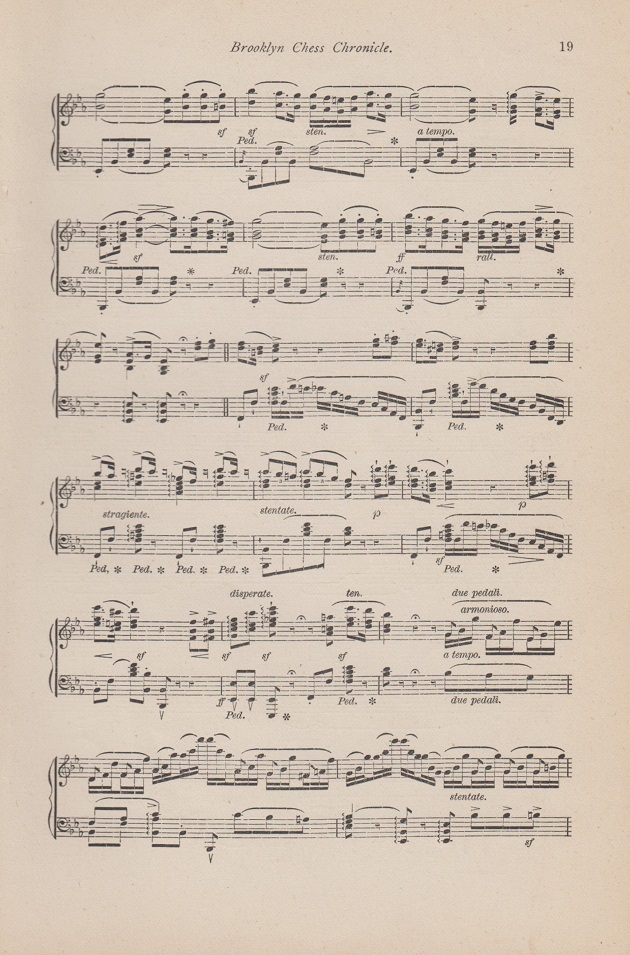

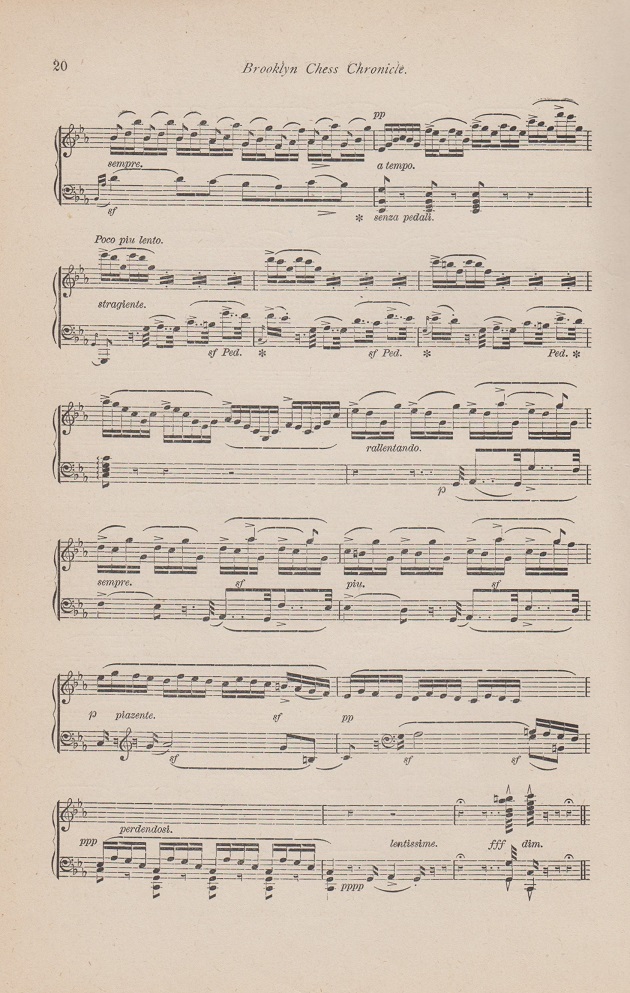

Pages 17-20 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 November 1884 published Ai Scacchisti Americani, Una Lagrima Sulla Tomba dell’immortale Scacchista Americano, Paolo Morphy by Giuseppe Liberali:

(9988)

The photograph of Loman from this page of The Tatler, which was provided by Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England), was shown in C.N. 10362:

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) notes on a CNN webpage a fine photograph of Ray Charles (1930-2004) with a Braille chess set.

(10633)

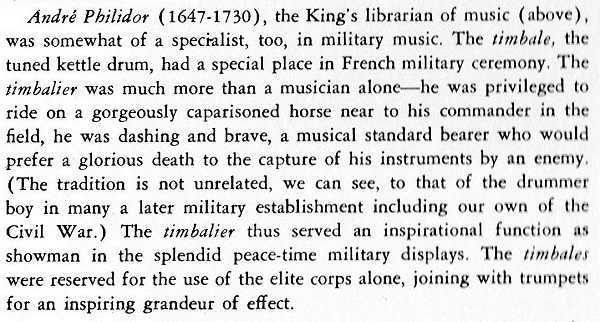

Myron Samsin (Winnipeg, Canada) owns an LP record featuring music composed by André Danican Philidor (1652-1730), the chess master’s father (known as Philidor l’aîné and Philidor le père):

The reverse of the record sleeve has the following note (with an incorrect year of birth for the composer):

For information about la dynastie des Philidor two particularly detailed books are François André Danican Philidor. La culture échiquéenne en France et en Angleterre au XVIIIe siècle by Sergio Boffa (Olomouc, 2010) and Les Philidor by Nicolas Dupont-Danican Philidor (Bourg-la-Reine, 1997).

(10701)

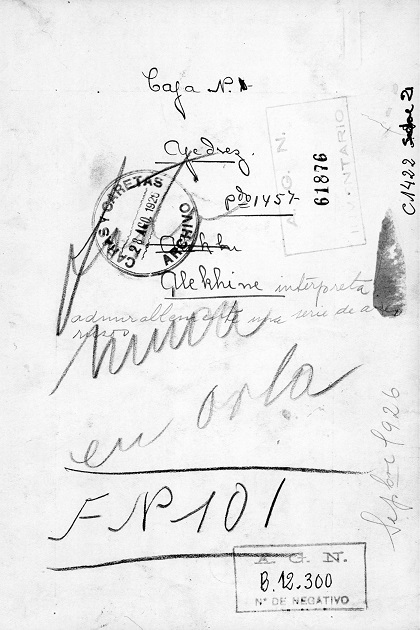

In C.N. 7290 Christian Sánchez pointed out an interview with Alekhine by Carlos M. Portela on page 8 of the magazine Caras y Caretas, 4 September 1926, which was accompanied by a photograph of Alekhine playing the piano.

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére now provides this fine version, from Argentina’s Archivo General de la Nación, courtesy of the Ministerio del Interior, Obras Públicas y Vivienda (reference AR_AGN_DDF/Consulta_INV: 61876):

(10842)

Anthony Santasiere, Chess Review, April 1943, page 111

Information is sought by Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) about a musical entitled Șah Mat (‘Checkmate’). It was an Israeli production in Romanian, and an advertisement in the National Library of Israel’s collection of posters and other ephemera states that the opening night was on 30 September 1967 at the Ohel Shem Theatre in Tel Aviv.

(10709)

Martin Weissenberg sends a photograph from page 98 of Russia’s Great Modern Pianists by Mark Zilberquit (Neptune, 1983) which features the composer and pianist Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007):

(11776)

Courtesy of the Russian National Museum of Music, Olimpiu G. Urcan forwards a better copy of the photograph in C.N. 11776:

(11797)

Martin Weissenberg shares these photographs taken by him at the Budapest home (1932-40) of Béla Bartók, which has been a memorial house since 1981:

(11783)

Concerning Samuel Reshevsky and Joseph Schwarz in the early 1920s, see The Chess Prodigy Samuel Reshevsky.

The website e-newspaperarchives.ch provides an opportunity to read more about the music activities of Peter Saburov (Pierre de Sabouroff). For example:

Source: Courrier de Genève, 19 December 1925, page 5.

Such material complements the biographical information about him given, from the Tribune de Genève, in C.N.s 448 and 2672.

(12198)

There are further references to music in the Factfinder.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.