Edward Winter

The Golden Dozen by Irving Chernev (Oxford, 1976), page 1

Widely diverging views have been expressed as to the qualities of Mein System/My System by A. Nimzowitsch. Examples are included in the present article, which draws together a number of C.N. items on one of the most frequently discussed books in chess literature.

Aron Nimzowitsch (Schweizerische Schachzeitung, May-June 1931, page 67)

From page 41 of the March 1963 Chess World:

‘Unquestionably, the most important single contribution to chess literature has been Nimzowitsch’s Mein System (My System in the English version).

... Although the individual Nimzowitsch is dead, he lives on collectively in every chess master to a greater or less degree. Thus Korchnoi is really Korchnoi plus Nimzowitsch, and so forth. Some masters show little of Nimzowitsch in their styles, but all have been influenced by him.

Other great players contributed to chess theory, but their contributions were mainly indirect. None could be compared with Nimzowitsch, whose contribution was direct, original, and not to the few but to the many.’

(4529)

All kinds of opinions, for and against, informed and uniformed, have been expressed about Nimzowitsch’s My System. It is worth noting the view of C.J.S. Purdy, a great author in his own right, on page 62 of Chess World, 1 March 1949:

‘Nimzowitsch’s immortal masterpiece. The greatest of all chess books, in the sense that it has, more than any other, really changed the methods of master players – and equally, of course, those of strong amateurs.

We all hear books described as “must” books, but this is the “must” book.’

(8170)

In the games section at the end of My System Nimzowitsch annotated a victory, ‘played in 1924’, over Anton Olson. It is the final game (headed Copenhagen, 1924) in Chess Strategy in Action by John Watson (Gambit Publications, 2003), and we quote from pages 281-282:

‘It seems unlikely that the game was played in a tournament setting: we have record of Nimzowitsch’s participation in only one tournament in 1924, a Copenhagen international event in which Olson didn’t play (Nimzowitsch won with 9½ points out of 10!).’

Olson did participate in that event (the Nordic tournament, Copenhagen, 11-23 August 1924), as is shown by the crosstable on, for instance, page 262 of the September 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung. Indeed, on pages 264-265 the magazine’s coverage of the tournament included the Nimzowitsch v Olson game, with annotations by Nimzowitsch himself. Different sets of notes by him subsequently appeared on pages 10-12 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 January 1925 and pages 93-94 of volume II of Schachjahrbuch 1924 by L. Bachmann. In all three cases the game was specified as having been played in the Copenhagen Nordic tournament.

(3004)

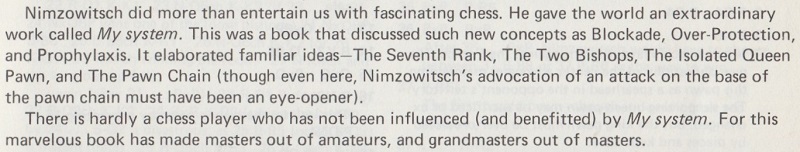

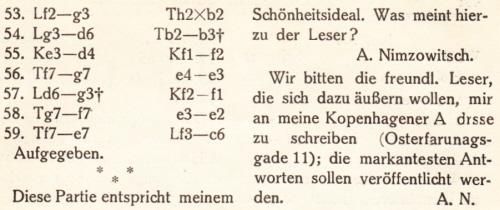

Mario Manasse (Milan, Italy) comments on the term ‘isolani’, a plural noun frequently used in the singular. Our Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms article lists the following with respect to English-language sources:

‘White has an “isolani”.’ My System by A. Nimzowitsch (London, 1929), page 187.

Below is the relevant passage from the original German edition (page 260):

We are seeking earlier uses of the word in a chess context, as well as clarification as to whether the singular form should be isolanus (Latin) or isolano (Italian).

(5047)

Sandro Litigio (Como, Italy) writes:

‘The Italian word isolani is the plural form of the adjective/noun isolano (island/insular/islander), while the corresponding Latin word is insulanus.’

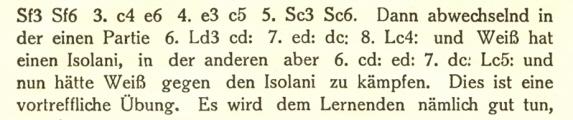

C.N. 5047 quoted the appearance of the word isolani in Nimzowitsch’s Mein System in the mid-1920s, but we have now found it in Leonhardt’s annotations to the game Dus-Chotimirsky v Tarrasch, Hamburg, 1910. Published in the Hamburger Nachrichten of 21 August 1910, the notes were reproduced on pages 357-359 of the October-November 1910 Wiener Schachzeitung. After 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 c5 4 e3 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 a3 Bd6 7 dxc5 Bxc5 8 b4 Bd6 9 Bb2 O-O 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Nb5 Bb8 there is the following:

Can earlier instances of the term be found, in the writings of Leonhardt, Nimzowitsch or anyone else?

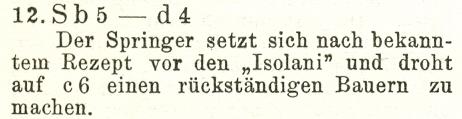

A possible explanation occurs to us regarding the singular/plural puzzle. Depending on the context, the German preposition vor (in front of) takes either the accusative or the dative case, but with a masculine noun (such as Isolani) the definite article would be den in both instances. For example:

a) Knights are effective when they stand in front of the isolated pawns. Springer sind wirkungsvoll, wenn sie vor den Isolani stehen. (Dative plural.)

b) White places his knight in front of the isolated pawn. Weiss setzt seinen Springer vor den Isolani. (Accusative singular.)

Is it conceivable that a German sentence such as the one in a) above was misinterpreted as the accusative singular, with the result that Isolani came to be regarded as a singular noun?

A more general question still outstanding, of course, is why an Italian word was used.

(5083)

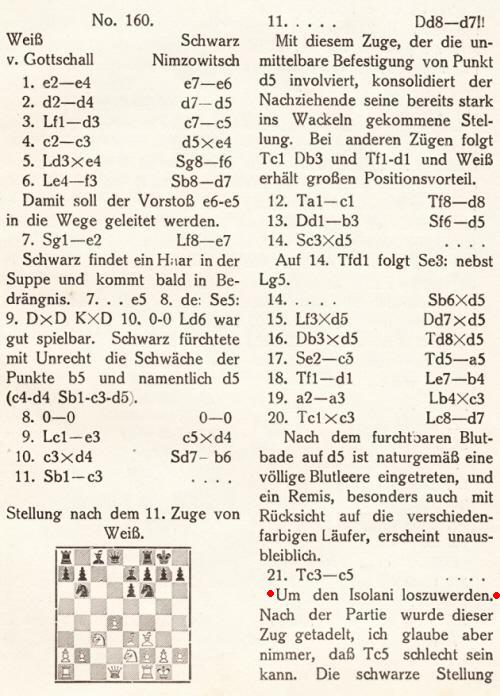

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) notes that Nimzowitsch used the word ‘isolani’ not only in Mein System but also, around the same time, on page 485 of the October-December 1926 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten. As his annotations to the game (H. von Gottschall v Nimzowitsch, Hanover, 1926) are different from those on pages 163-165 of his book Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930), the full game is reproduced here from pages 485-487 of the magazine:

It is not only the annotations that are different. Quite apart from the misnumbering of some moves above, there are discrepancies in the score compared to the version in Die Praxis meines Systems and on pages 66-67 of Kongreßbuch Hannover 1926 (Berlin, 1926). Has either player’s score-sheet survived?

(8281)

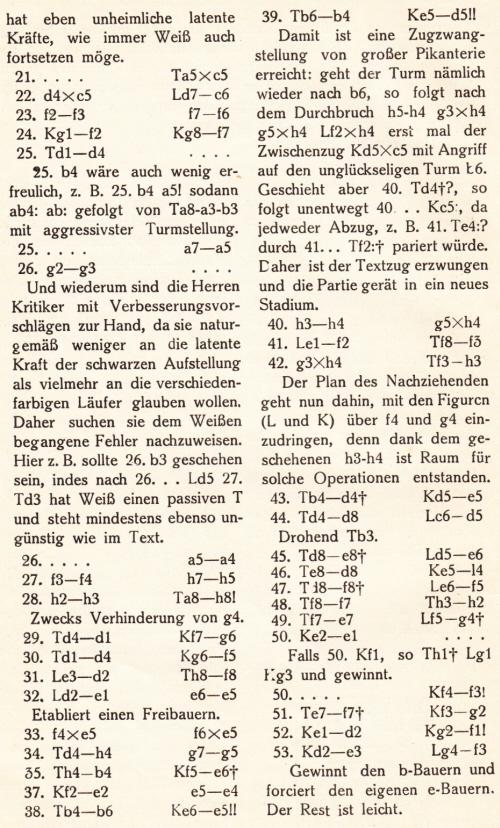

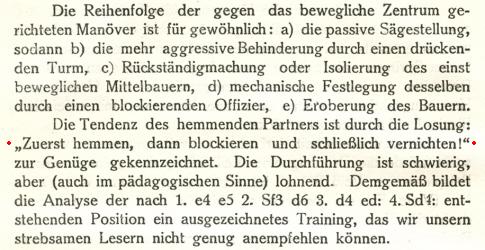

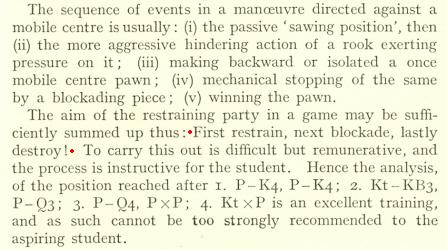

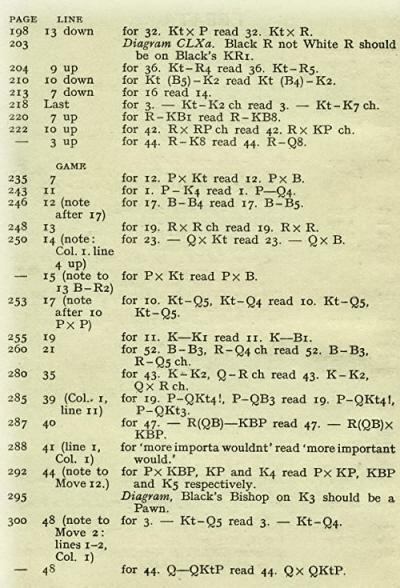

Nimzowitsch’s dictum ‘First restrain, next blockade, lastly destroy’ is certainly famous, yet we are struck by how seldom it is to be found on the Internet. Moreover, not a single webpage consulted by us gives the source (My System), and we found no instance on-line of the original German (‘Zuerst hemmen, dann blockieren und schließlich vernichten’).

Below, to provide the context, is the full passage as it appeared in the first German and English editions (Berlin, 1925, page 246 and London, 1929, page 181):

It was in the section entitled ‘Doppelbauer und Hemmung’/‘The Doubled Pawn and Restraint’. Page numbers vary, but in the later editions of My System in our collection the reference is page 133, 151, 207 or 217. The last of these relates to the translation published by Quality Chess, Göteborg in 2007, which had a slightly different wording: ‘First restrain, then blockade and finally destroy.’

(5557)

Under the heading ‘Continuing efforts to set the record straight’ we wrote in The Termination:

Our Preface to Chess Explorations (1996) commented that Chess Notes was ‘born from the stark realization that the beaten track of chess literature was bestrewn with fallacies, guesswork and hearsay’ and that C.N. attempted ‘to clear away some of the deadwood and supplant it with a garland of more reliable material, founded on proper documentation’. With the Termination, much deadwood has been cleared away, but the supplanting process is slow and difficult.

To set the public record straight, a methodical approach can help: rebut misinformation and speculation, staunch their propagation, piece together the truth. First destroy, next blockade, lastly rebuild.

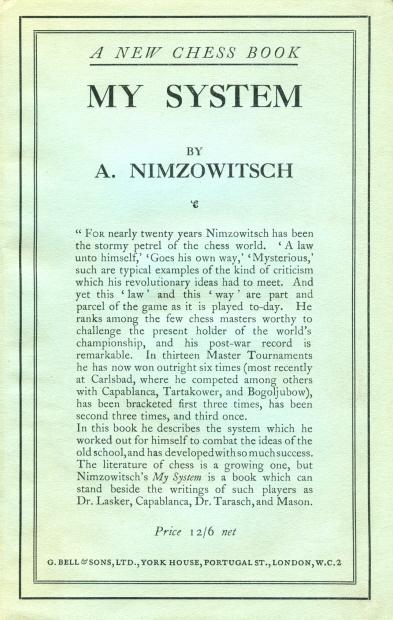

Dust-jacket front (1929)

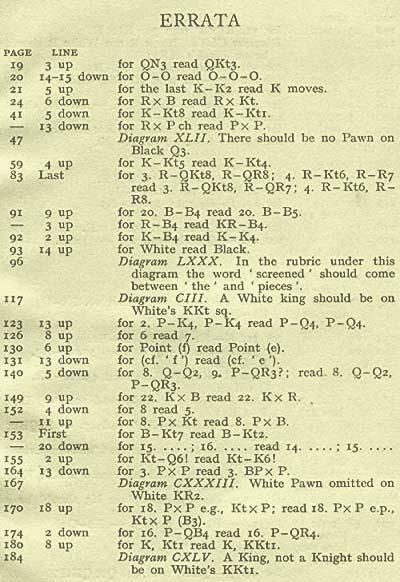

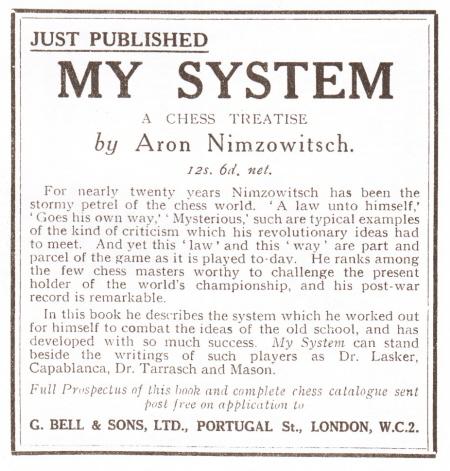

Nimzowitsch’s My System was first published by G. Bell and Sons, Ltd. in 1929 (302 pages), and the company also issued a two-page errata list. Some, though not all, of the corrections were included by Bell many years later in a reset version (265 pages).

In 1987 B.T. Batsford Ltd. chose to reprint the 1929 original, but the company’s then ‘Adviser’, Raymond Keene, did not realize this. He added a Foreword (‘Batsford are proud to present this new edition ...’) which mentioned page numbers corresponding to the other Bell edition. The Batsford reprint furthermore revealed ignorance of the errata list.

In 2003 Hardinge Simpole brought out a reprint of My System, though it was nothing more than an expensively priced, cheaply produced, reprint of the Batsford reprint, still with ignorance of the errata list, still with the mix-up over the page numbers and, even though Batsford’s name was not mentioned elsewhere, still with Mr Keene’s remark ‘Batsford are proud to present this new edition’.

How pride can come into any of this is unclear.

(6237)

Below is the errata list for the 1929 edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System:

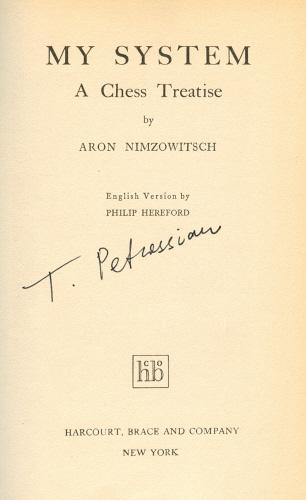

The 302-page edition brought out by Bell in 1929 was published the following year by Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York. One of our copies was inscribed by a world champion on whom Nimzowitsch had considerable influence:

(6245)

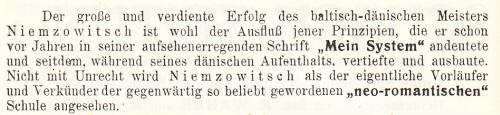

The above paragraph (on page 34 of the April 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung) comes from a report by Tartakower on Copenhagen, 1923. It is quoted by Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany), who asks which publication entitled Mein System Tartakower had in mind, given that Nimzowitsch’s book of that name had not yet appeared at that time.

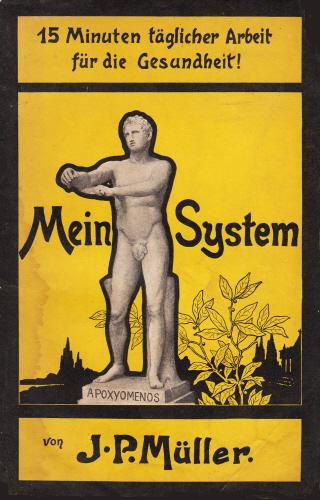

C.N. 2839 (see page 73 of Chess Facts and Fables) referred to pages 294-304 of the October-November 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung, where Nimzowitsch wrote about ‘Das neue System’. In C.N. 5552 a correspondent mentioned that page 24 of Nimzowitsch’s booklet Kak ya stal grosmeysterom (Leningrad, 1929) recommended gymnastics with ‘Müller’s system’, i.e. Mein System 15 Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit by J.P. Müller (Copenhagen and Leipzig, 1904). Further information on Müller’s book was given in C.N. 5572. See too C.N.s 5581 and 7748.

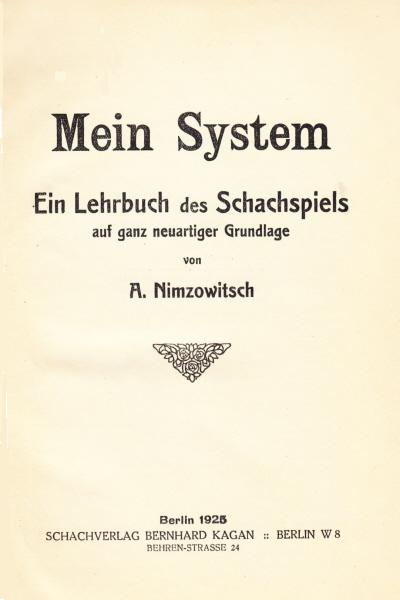

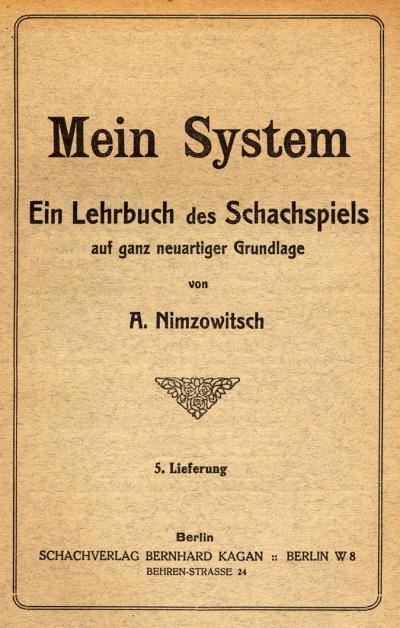

It is customary to state that Nimzowitsch’s Mein System was published in 1925, the year specified on the title page:

However, the work appeared in five instalments, of which only the first was dated 1925. David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) has kindly provided the front covers:

Publication of the first instalment was reported on page 447 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 October 1925. We also note that, for instance, the third instalment was scheduled to appear at the end of April 1926, as announced on page 224 of the January-March 1926 Kagans Schachnachrichten. The bound edition of the five instalments was published on 20 February 1927, according to the back page of the ‘Erstes Extrablatt’ (1927) of Kagan’s magazine.

From Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark):

‘The material published by Nimzowitsch in 1913 (“Das neue System”) is definitely part of “Mein System”, but at the time of the earlier publication Nimzowitsch was not aware of the full scope of the final version of “Mein System”. His article was first and foremost part of his dispute with Tarrasch on the notion of “the centre”. I have no reference to any use of the specific title “Mein System” at that point.

Of course, the final publication Mein System contained far more material, and many more ideas, than “Das neue System”, although much of the material from “Das neue System” found its way into the book. Nimzowitsch wrote on page 28 of Kak ya stal grosmeysterom:

“Although I had felt ‘anxiety’ about them [the elements of Mein System] as early as 1902, I was unable to surmount the enormous difficulties that confronted me for a long time. I conceived isolated parts, e.g. the idea of the outpost, and also the new understanding of the pawn chain, during the period 1911-13.”

Thus I would say that the notion of “Mein System” (as well as the elements) was born no later than 1913.

A further question is when the final version of Mein System was written. It is not possible to give an exact date or period, but it was derived from many articles and game notes published by Nimzowitsch in a variety of newspaper columns and magazines during the years 1911-24. So “Mein System” was something that he had “assembled” and written before any of the instalments were published.

It is worth noting what Nimzowitsch stated about his system on pages 289-290 of the October 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung:

“It is not about the opening but, rather, the middlegame. It is a set of rules about the individual elements of chess strategy such as the open file, the seventh rank, the passed pawn, exchange technique and pawn chains. Everything is there, beautifully arranged and nothing is missing – except a publisher. I have given lectures on “my system” for the last four years in Scandinavia and, for that reason alone, I have hardly felt that my stay here was a self-chosen exile.”

The final point is when his book (concept) was named “Mein System”. As indicated by Nimzowitsch above, he travelled around Scandinavia during the years 1920-24, giving lectures about his “own system”. I have tried to find the first occurrence of the title “Mein System”, but it is not a straightforward matter. Several newspaper articles mention Nimzowitsch “who will lecture on his own system”, but the first specific use of “Mein System” that I have found is in the Swedish newspaper Kalmar Läns Tidning of 21 February 1921:

“Mr N. conducted a lecture under the title ‘My System in Chess’.”

Concerning the interesting question of whether Tartakower’s reference to “Mein System” in 1923 was an anachronism, strictly speaking the answer is probably yes, but I think that he was referring to “Das neue System”, which, as was well known, Nimzowitsch had improved and enhanced during his stay in Scandinavia.’

With respect to individual components of Nimzowitsch’s system, we see the following remark by him on page 300 of the October 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘Dieser tiefe Ausspruch enthält, wenn auch nur im Keim, mein System der Ch. St. [Charakteristische Stellung im Zentrum]!’

(7735)

On page 1112 of the Illustrated London News, 20 December 1958 B.H. Wood wrote:

‘For real depth in middle-game strategy, I have recommended Nimzowitsch’s My System for well-nigh 25 years. It is a tortuous, obscure book in the original German, full of distracting half-jokes. The translator has, if anything, made things worse (for instance by alluding to an “overloaded” piece when obviously “over-burdened” is the word). But there are few books which reward you as richly if you really stick to them. More good players swear by My System than by any other book I know.’

Harry Golombek discussed My System in his section on Nimzowitsch on pages 42-47 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966).

C.N. 5215 quoted a remark about Nimzowitsch by Golombek in his Times column of 17 September 1977, page 10:

‘Colourful and energetic though his writings were, they are based on a fallacy. He gives you a collection of tactics which he elevates into a so-called system. His zestful writing and his great combinational gifts have tended to mask this; but in truth he gives us a façade rather than a building with inner dimensions.’

The conclusion of a review of Nimzowitsch’s My System contributed by T.R. Dawson on pages 29-30 of the November 1929 Chess Amateur:

‘The book is got up in Bell’s usual good style and is free from any great number of obvious errors. The translator shows an ignorance of many well-known technical terms, but that may even be an advantage for the average British player.’

(8548)

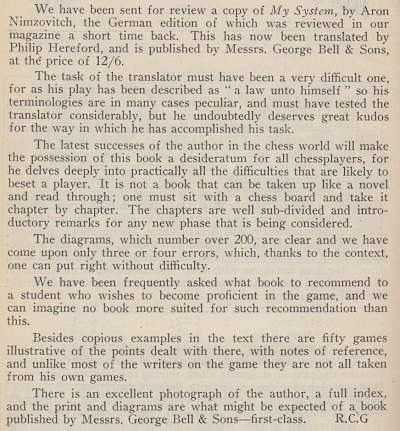

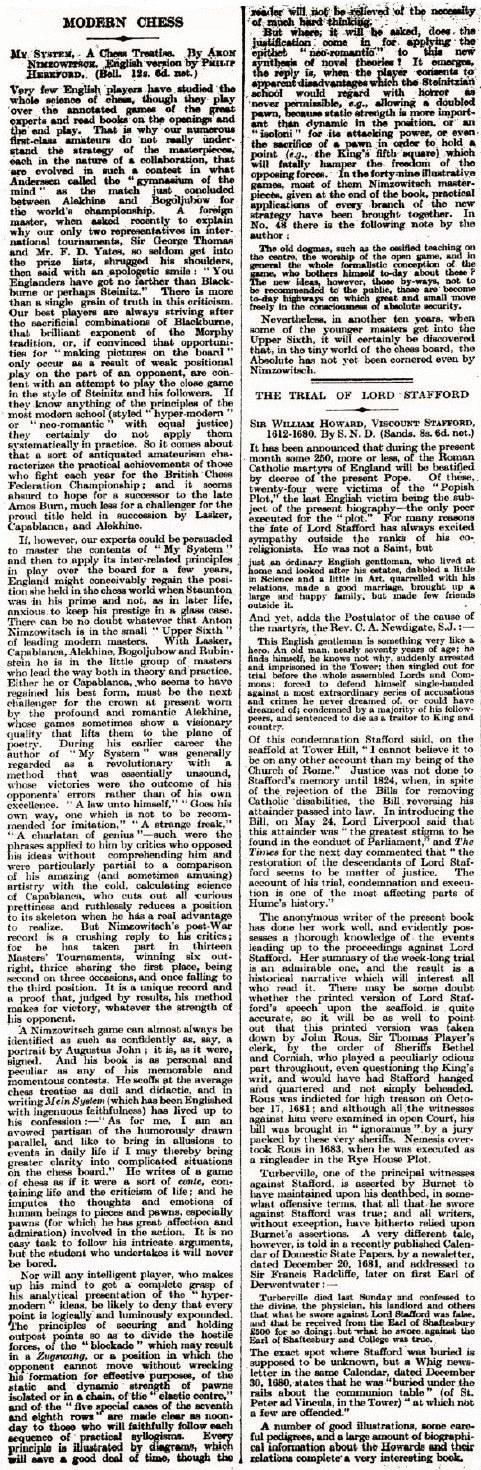

Page 458 of the December 1929 BCM had a perfunctory review by R.C. Griffith:

The technical issues concerning the book were dealt with more deeply in an unsigned critique on page 1021 of the Times Literary Supplement, 5 December 1929:

The February 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung featured four spoof games parodying the annotational styles of Becker, Bogoljubow, Tartakower and Nimzowitsch. For example, pages 52-53 had a 13-move draw (Falkbeer Counter-Gambit) between Grünfeld and Capablanca headed ‘Anmerkungen von E. Bogoljubow’ (‘Annotations by E. Bogoljubow’); it was a bare game-score.

Pages 57-59 carried one of the most famous chess parodies, ‘Eine geniale Illustration zu meinem System’ by ‘Aaron Nimzowitsch’, with the game Nimzowitsch v Sistemsson, Copenhagen, 1927 (beginning 1 e4 e6 ‘2 h4!!’).

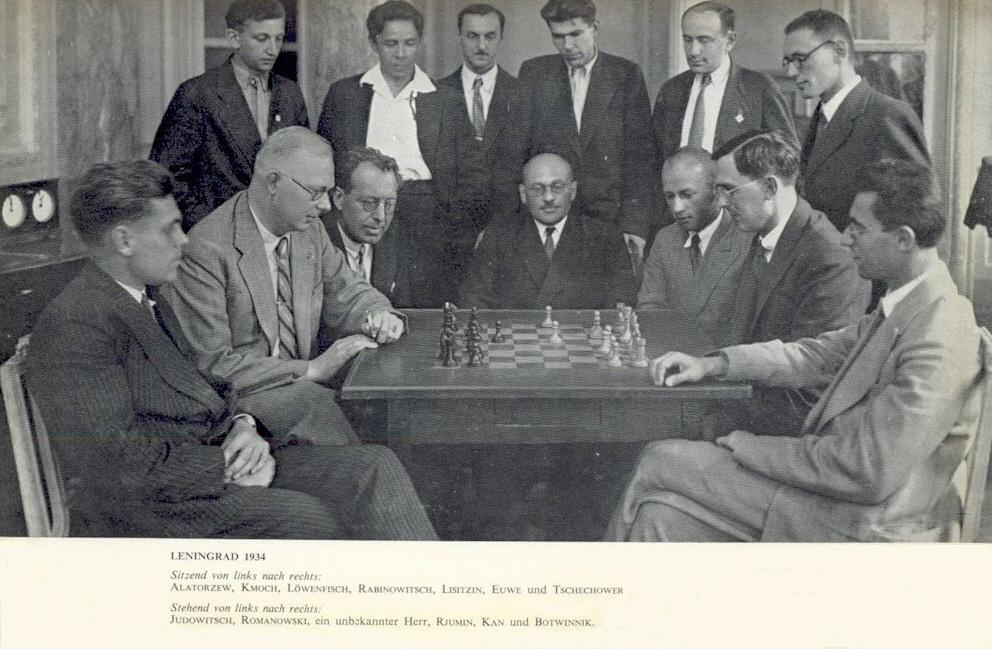

The above photograph was published opposite page 208 of Hundert Jahre Schachturniere by P. Feenstra Kuiper (Amsterdam, 1964), and it was ‘Black’, Hans Kmoch, who had composed the parody. An English edition appeared on pages 104-105 of the April 1951 Chess Review under the title ‘An Ingenious Example of My System’ (where Black was named as Systemsson), and a slightly different text (entitled ‘A Masterly Example of My System’) was given on pages 169-176 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951). Two other anthologies which included it are The Best In Chess by I.A. Horowitz and J.S. Battell (New York, 1965), pages 213-220, and The Best of Chess Life and Review, Volume 1, 1933-1960 by B. Pandolfini (New York, 1988), pages 432-439.

A strange commentary on the parody was written by R.E. Fauber on page 209 of Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992):

‘My System is a peach of a book, ripe both for adulation and parody. When Hans Kmoch’s parody of Nimzovich was reprinted in Chess Review in 1951, readers took the nonsense as serious instruction. Reading that “the move is strong because it is weak!” after the moves 1 e4 e6 2 h4!! caused not a ripple. Some agreed with another note in which “Herr Sistemsson” wrote, “The fact is that I’m a marvelous player, even if the whole chess world bursts with envy”.

One reader wrote, “Sold one copy [of My System], Nimzovich’s system seems to me really good.” Another reader diffidently wrote, “I hope I don’t offend anyone. But I think Aaron [sic] Nimzovich went wrong by 23 Q-R7 ...” and demonstrated that “Sistemsson’s fictitious opponent overlooked a mate in six”.

Even in jest it was Nimzovich’s fate to be misunderstood. The public applauded his teachings only after they had been carefully distorted ...’

The two additions above in parenthesis were by Fauber, who mysteriously ascribed the remark about envy to ‘Sistemsson’ rather than Nimzowitsch/Kmoch. As regards the reaction of Chess Review readers, below are the letters to which Fauber was referring, from page 193 of the July 1951 issue:

It should, in any case, be noted that when publishing the game Chess Review (April 1951, page 105) had made it clear, in this editorial end-note, that the game was a parody:

‘To the incredulous, the above article was published in the February 1928 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung under the editorship of Hans Kmoch.

Kmoch admired and esteemed Nimzovich as a great player and a profound and original thinking. Yet he could not help poking sly fun at Nimzovich’s often pompous and bombastic manner. Luckily this rollicking parody is so good-natured, with a few grains of sense artfully concealed in a farrago of nonsense, that Nimzovich expressed himself as vastly amused by it.’

(4772)

Concerning the man referred to as ‘unknown’ in the group photograph caption above, see C.N. 11173.

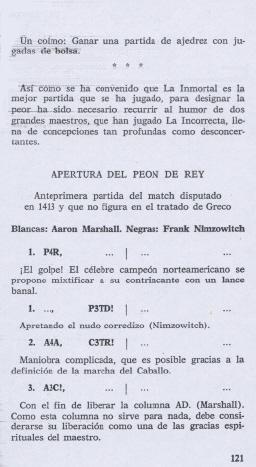

C.N. 4772 dealt with the famous Nimzowitsch v Sistemsson parody, and now Javier Asturiano Molina mentions a fantasy game between ‘Aaron Marshall’ and ‘Frank Nimzowitch’: 1 e4 a6 2 Bc4 Nh6 3 Bb3 Nf5 4 Be6 Na7 5 Qh5 Resigns 6 Drawn.

It was published on pages 121-122 of Ajedrología by Julio Ganzo (Madrid, 1971):

Had the spoof already been published elsewhere?

(4842)

C.N. 2195 (see page 134 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted from page 574 of the March 1882 issue of Brentano’s Chess Monthly a reference to P. Richardson being named ‘The Stormy Petrel’ by G.H. Mackenzie. See too Philip Richardson The Stormy Petrel of Chess by John S. Hilbert (Olomouc, 2009).

The description ‘stormy petrel’ in connection with Nimzowitsch is on page v of My System (London, 1929), at the start of the Translator’s Preface. The translator was Arthur Hereford Wykeham George, using the pseudonym Philip Hereford (BCM, July 1937, page 361).

The relevant text also appeared on the front of the dust-jacket and in advertising material, such as the following on page 45 of the November 1929 Chess Amateur:

Have any other languages taken up a name such as ‘stormy petrel’ in connection with Nimzowitsch, Richardson or any other player?

(8191)

Another player, in addition to Aron Nimzowitsch and Philip Richardson, who was given the name ‘stormy petrel’ is noted by Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel): Israel Barav (Rabinovich) in the Palestine Post, 25 April 1945, page 2.

(10747)

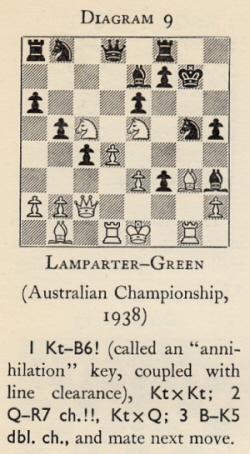

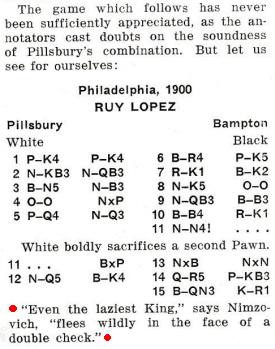

From page 7 of The Brilliant Touch by Walter Korn (London, 1950):

Further information is sought about this position, which was also shown by Irving Chernev on pages 12-13 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960):

Concerning the note after 3...Kh6, it is unclear why Chernev did not mention that ‘Even the laziest king flees wildly in the face of a double check’ was a remark by Nimzowitsch. Chernev knew it, having given the attribution in an article on the inside front cover of Chess Review, November 1954:

The full Pillsbury v Bampton feature was reproduced on pages 200-201 of Chernev’s book The Chess Companion (New York, 1968), and the position at move 13, when the black king flees from the threat of double check, may seem a better illustration than the Lamparter v Green position.

The remark appeared in My System, in the chapter on discovered check; page numbers vary according to the edition. On page 146 of the 2007 translation published by Quality Chess the text was:

‘Even the most sluggish king will panic – driven to flight after a double check.’

In the original of Nimzowitsch’s work, Mein System (Berlin, 1925), the passage was on page 156:

‘Selbst der trägeste König greift angesichts eines Doppelschachs zur wildesten Flucht.’

Whether a ‘perfect’ version of Nimzowitsch’s remark can be made is doubtful, but a curious point is that whereas the English translation from the 1920s (‘Even the laziest king flees wildly in the face of a double check’) is frequently quoted in books and articles, though usually without an exact reference, the original German text is seldom cited anywhere.

(8652)

The full score of the Lamparter v Green game was given in C.N. 8655.

The following appeared in the chapter on pins in My System, e.g. on pages 96-97 of the original English-language edition (London, 1929):

‘A pinned piece’s defensive power is only imaginary. He only makes a gesture as if he would defend; in reality he is crippled and immobile. Hence we may confidently place our piece en prise to a pinned piece, for he dare not lay hands on it.’

From page 133 of Nimzowitsch’s original text, Mein System (Berlin, 1925):

‘Ein gefesselter Stein deckt nur imaginär. Er tut nur so, als ob er decken würde; in Wirklichkeit ist er ja gelähmt und unbeweglich. Daher darf man seine eigenen Offiziere getrost en prise stellen; der gefesselte Stein darf doch nicht zugreifen.’

A different wording in English, ‘The defensive power of a pinned piece is only imaginary’, was given as a Nimzowitsch quote on page 7 of Winning Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948). On page 61 of A First Book of Morphy (Victoria, 2004) Frisco Del Rosario attributed the remark ‘The defensive power of a pinned piece is illusory’ to Reinfeld.

(8716)

In an article presenting his new edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System Fred Reinfeld wrote on page 208 of the July 1949 Chess Review:

Can information be found about Reinfeld’s game against Cohen?

Reinfeld also mentioned his visit to the New York, 1927 tournament on page 161 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games (New York, 1952), in the chapter on Capablanca:

‘The other masters were so clearly outclassed that comparison was piteous. I attended the tournament one day to catch a glimpse of the grandmasters. Capablanca looked sleek, poised, quite sure of himself. The others were fearfully nervous – Sorcerer’s Apprentices, all of them, in the presence of the master magician. In any other man, Capablanca’s air of assurance would have made a distasteful impression – but not in his case: he looked so distinguished, so authentically a great man, that the predominant reaction was one of awe.’

(8805)

Anyone finding Nimzowitsch’s games and writings difficult to understand may wish to refer to the chapter about him in The Dynamics of Chess Psychology by Cary Utterberg (Dallas, 1994). Below is the concluding paragraph, on page 131:

‘When responsibility is first encountered existentially, the resulting anxiety can be particularly troubling (a dilemma akin to Ivan Karamazov’s lament that, “Everything is permitted”, – a recognition that there’s no objective ground of morality, but one accompanied by a nagging feeling that there’s still a universal legislator, only he’s not on the job). In such cases, anxiety tends to manifest itself as lack of direction, indecision, and uncertainty. As a consequence, Nimzovich – one of the first masters to experience responsibility – oscillated between employing the phenomenon and generalizing its insights into strategic laws – entities that can at best reflect the radically subjective nature of responsibility. This is why Nimzovich was the last great law-giver of chess – because leading masters since his day have moved beyond anxiety to a deeper, more authentic relation with responsibility.’

(9544)

Two recent comments, both negative, are added, from Chess for Life by Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan (London, 2016).

On page 143 Nigel Short described My System as ‘a dreadfully boring book’, and on page 164 Yasser Seirawan observed:

‘Personally I found Nimzowitsch unreadable. His ideas on overprotection were over-the-top. He wasn’t the first person to play prophylactically. For some people, though, this book is the cat’s meow. I’ve been told that Nimzowitsch is much better in the original German but some of the humour and nuances have been unavoidably lost in translation.’

Mein System is a rare case of a chess book also existing in a simplified version, edited by Heinz Brunthaler (Zeil am Main, 2007):

(9792)

Russell Enterprises, Inc. has just produced a ‘FastTrack Edition’ of My System, edited by Alex Fishbein.

(12000)

My System, Philip Hereford’s translation of Nimzowitsch’s best-known book, Mein System, was published by G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., London in 1929 and by Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York in 1930. In 1991, Hays Publishing, Inc, Dallas issued a ‘21st Century Edition’ which, the title page specified, was ‘edited and converted to algebraic notation by Lou Hays’:

We have now come across another edition of the Hays volume:

Although the body of the work is identical to the 1991 book, all mention of Lou Hays and Hays Publishing, Inc. has been deleted, as has Yasser Seirawan’s 2½-page introduction.

At the end of the book there is a full-page advertisement, under the heading ‘Recommended Readings [sic]’, for The Art of Checkmate by Georges Renaud [sic], but we have found no corroboration of the claim that it is ‘available at www.snowballpublishing.com’.

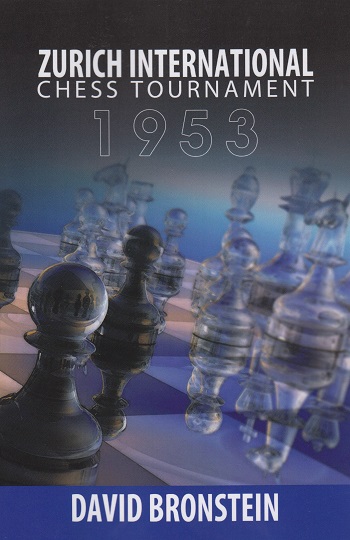

We do, though, have one other Snowball Publishing volume, also dated 2012: Zurich International Chess Tournament 1953 by David Bronstein:

The name of the translator, Jim Marfia, has been retained on the title page, but the book is merely a low-quality reprint of what Dover Publications, Inc., New York brought out in 1979 (front cover below), with all reference to Dover removed.

(10005)

The Chess Tournament – London 1851 by Staunton has just been reprinted – superbly – by Batsford, as has Nimzowitsch’s Chess Praxis. Mr Raymond Keene’s willingness to supply his company with a Foreword to the latter work is not readily comprehensible when one recalls his words on page 4 of Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal:

‘The English of My System is, by and large, very good and makes a brave effort to capture the spirit of Nimzowitsch’s original German, but, unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the translation of Chess Praxis which I find a poor, maimed torso of Nimzowitsch’s original. If you have no alternative read the translation by all means, but if you possess the merest smattering of German I urge you to read the original. It is well worth the effort.’

(1231)

In 2016 New in Chess published My System & Chess Praxis, translated by Robert Sherwood.

The sections on Nimzowitsch in R.N. Coles’ highly-regarded book Dynamic Chess (London, 1956) may be read in conjunction with two articles contributed by Coles to Chess Review that year: ‘New Light on Nimzovich’ (April, pages 108-109) and ‘The Negative Dynamism of Nimzovich’ (November, page 334).

The former article began:

‘That strange genius, Aron Nimzovich, was a chessmaster of many parts, but in no way was his genius more strikingly illustrated than in his ability to convince the world that Aron Nimzovich was a genius and a true original.

Closer examination reveals that Nimzovich’s claims cannot always be substantiated, as for example in his claim to be the discoverer of the theory of over-protection. “That strategically important points”, he writes in his Chess Praxis, “should be over-protected is a principle discovered by the author.” My answer to that is, “Nonsense!”’

Coles subsequently wrote:

‘... all that Nimzovich really did was to invent the phrase, “over-protection”, and for so doing he won all the credit (plus a good deal of adverse criticism) for the idea of over-protection.

In point of fact, he was merely filching an idea from Steinitz, dressing it up as his own and presenting it as part of MY System.’

Coles then gave Steinitz v Weiss, Vienna, 1882, with notes from Dynamic Chess, to demonstrate that Steinitz ‘knew all about over-protection nearly half a century before Nimzovich launched it on the world as his own’.

He concluded:

‘I am not denying Nimzovich his great ability as a player, nor that he was an original thinker, but merely pricking that bubble of bluff which he also handled like a master of another kind ...

I hope that Dynamic Chess will prove illuminating, not merely as putting a few of the Hypermodern ideas in their proper context but also as a review of the Dynamic style of which Nimzovich was genuinely one of the founders, though in some respects to a lesser extent than he himself would have had us believe.’

An editorial footnote quoted a letter from Coles:

‘The article [above] is more polemical than the book [is] on the same subject, since I did not feel that the book was the place to start up hares (or red herrings) of this nature. ... I feel that, if Nimzovich is to be debunked in some small degree, an article rather than a general treatise is the place for it.’ (Ellipses and additions in square brackets are as in the original.)

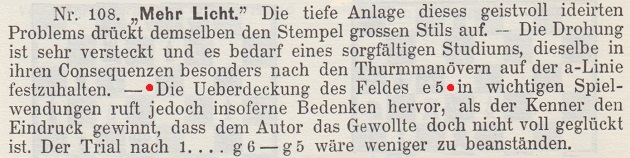

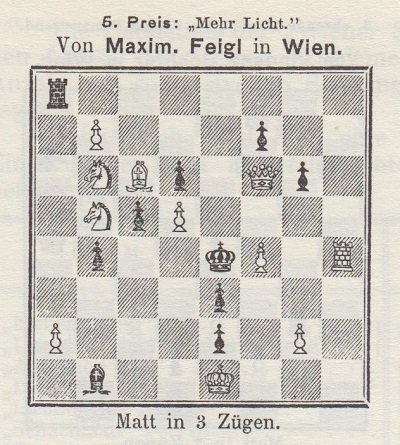

Concerning over-protection (Überdeckung), we seek early sightings of the term. From page 159 of the September 1901 Wiener Schachzeitung:

The problem was on page 161:

The composition had also been published on page 139 of the July 1901 Wiener Schachzeitung. The solution was on page 22 of the January 1902 issue.

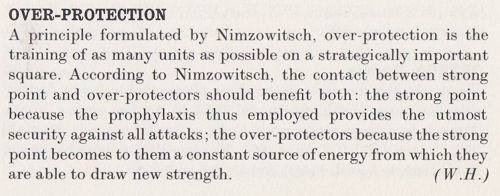

Below is Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on over-protection on page 230 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

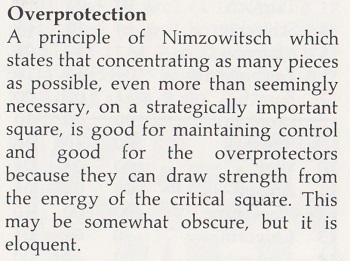

We add without comment what Nathan Divinsky gave on page 154 of The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia (London, 1990):

A third-person summary of the above-mentioned Steinitz v Weiss game was published by Steinitz in his Field column of 3 June 1882:

‘Steinitz treated the French defence, adopted by Weiss, in the same fashion as against Fleissig, viz with the new move 2 P to K5, to which Weiss replied 2...P to QB4. Steinitz then proceeded with P to KB4 and the K fianchetto. He carefully abstained from all attempts at exchanging his QP against the QBP, but kept the QP at Q3. He, however, exchanged immediately, in passing, his KP for the adverse QP as soon as the latter advanced, and he thus obtained the open K file, which, according to his idea, should be the main object of the attack. White had a good game throughout; and, after having well secured the Q side, he opened an attack on the K side, which forced the gain of a P and brought the adverse K into serious trouble. Steinitz would up with an interesting sacrifice of the exchange, which forced a mate after four hours’ play.’

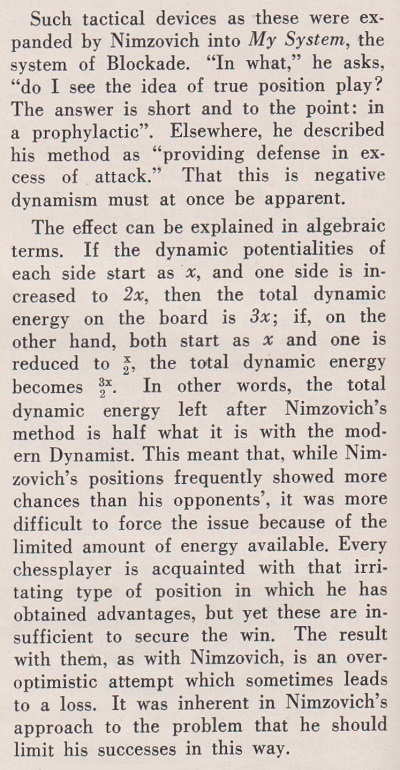

The second Chess Review article by R.N. Coles in 1956 (November issue, page 334), ‘The Negative Dynamism of Nimzovich’, stated:

‘Nimzovich, instead of seeking at all costs to increase the dynamic potentialities of his own position, played instead to reduce at all costs the dynamic potentialities of his opponent’s position.’

After a discussion of certain openings favoured by Nimzowitsch, there came this key section:

Under the title ‘The Evolution of Chess Method’ R.N. Coles also discussed Dynamic Chess, although not Nimzowitsch, on page 317 of CHESS, 8 September 1956, following a book review on page 246 of the 26 May issue and a letter from a reader, J. Taylor, on page 278 of CHESS, 7 July.

(10453)

See too Articles about Aron Nimzowitsch.

Concerning the Horrwitz/Horwitz/Harrwitz/Horowitz matter, see Raking Bishops.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.