Edward Winter

(2000, with additional material)

Firstly, we offer a digest of quotes from the BCM of the 1930s and 40s.

June 1933, page 269:

‘In his anxiously awaited speech to the Reichstag on 17 May, Herr Adolf Hitler made a curious comparison, which is thus reported in the telegraphic accounts. Speaking of the Nazi Storm Troops, he said: “If Storm Troops are to be called soldiers, then even the chess and dog-lover clubs are military associations.” Well, we know that chess has been called effigies belli; but it has not yet gone to the dogs!’

Regarding the authenticity, or otherwise, of the attribution, see C.N. 5902 below.

August 1933, page 344:

‘The German “Propaganda Minister”, Dr Goebbels, is honorary president of the new Federation.’

September 1933, page 385:

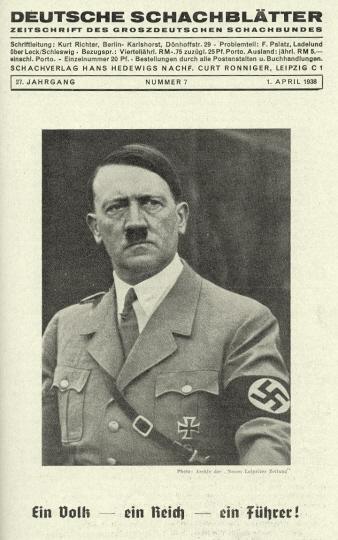

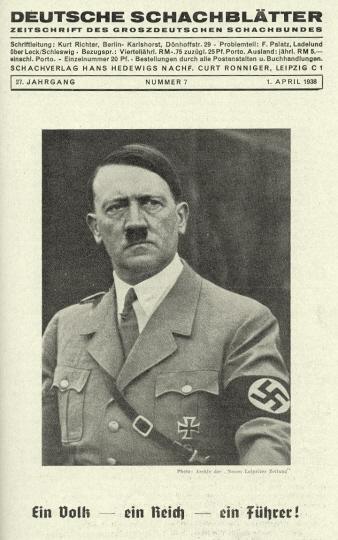

‘The new German Chess Federation is the Grossdeutsche Schachbund, being a Pangermanic League of Chess on National Socialist lines, of which the president must be approved by Chancellor Hitler. We have not seen the articles of constitution. But it is stated that by them players of Jewish origin are not in future eligible for membership of chess clubs in Germany unless they have received the decoration of the Iron Cross or were combatants in the War. “Aryan” race is a requisite for participation in national tournaments.’

December 1934, page 506:

‘The recent embargo on Germans leaving the country, forbidding them to take with them more than the equivalent of about 15s., is likely to prevent visits abroad of players from Germany – notably to England.’

October 1935, page 446:

‘The new German C.A. is not affiliated, but a representative was present [at a FIDE meeting in Warsaw] seeking support of the FIDE for a team tournament at Munich next year concurrently with the Berlin Olympiad (athletics). Some opposition was offered on account of Germany’s non-affiliation, but eventually on a vote it was left to each country to take its own line on the matter.’

April 1936, page 175:

‘We omitted to record last month that in a tournament held at the Bar Kochba, Leipzig, at the end of 1935, for the Jewish championship of Germany, S. Fajarowicz and J. Mundsztuk, both of Leipzig, and S. Rotenstein, of Berlin, tied for first place, with 5 points each in 7 games. The tournament was played on the Swiss system, with 17 competitors in all.’

November 1936, page 546:

‘When then shall we hear of the re-entry of Germany into the International Chess Federation? It is difficult to understand why Germany withdrew; for it was, of course, a case of withdrawal, not of expulsion. The virus of politics is indeed potent if it prevents both Germany and Russia making the FIDE truly what its name claims to be.’

June 1939, pages 257-258:

‘... Germany, since Hitler adopted Nimzowitsch’s theory of over-protection, has acquired fresh and vast resources in the matter of chess masters – e.g. Eliskases, Becker and Lokvenc from Austria and Gilg from Czechoslovakia.’

October 1939, page 425:

‘This time the same enemy has attacked wantonly another Ally, and unfortunately we are not in a sufficiently good geographical position as to give the same assistance as we were able to render to France in 1914 to 1918; and it is evident that, after 25 years, in a war on a large scale, as we must feel this is likely to be, all civilians have to do their share towards helping their country to win the battle for Right over Might.’

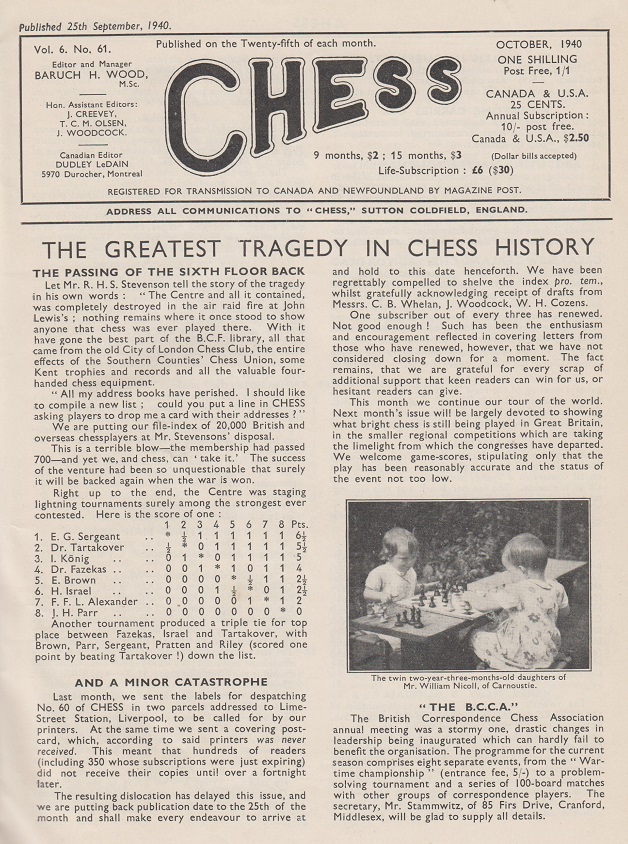

October 1940, page 321:

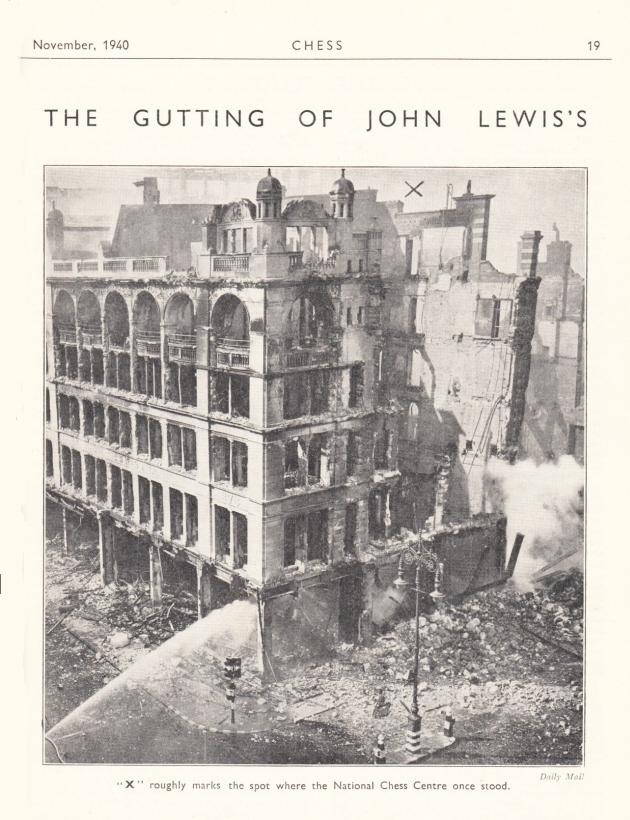

‘Last month our Editor, Mr H. Golombek, reported that as he was serving in the Royal Artillery, he had handed over his editorship to me [R.C. Griffith, Acting Editor], and that all communications should be addressed to me at 8 Victoria Avenue, Bishopsgate, London, E.C.2. In the early hours of 9 September a Nazi pigeon dropped his mess in our courtyard, and Victoria Avenue is now a dust heap. Consequently, much material handed over to me by Mr Golombek, such as articles by I. König, games from all sources, etc., which we had selected for inclusion in the British Chess Magazine, are buried, perhaps to be discovered in the year A.D. 2000.’

December 1940, page 394:

‘The “Gambit”, the famous chess resort in Budge Row, still caters for the lover of chess. We are glad to say that it has escaped the fate of other chess centres, the National Chess Centre, Printingcraft and Frank Hollings (an extraordinary number of disasters for chess and quite out of proportion to the amount of damage done to the capital as a whole).’

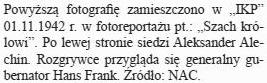

The photograph was also published on page 93 of CHESS, February 1952.

From C.N. 10418:

June 1941, page 166:

‘A remarkable feature of the “Blitzkrieg” is the quite disproportionate amount of damage inflicted on concerns dealing in chess materials and books. The latest sufferers are Messrs John Jaques & Sons, whose factory and offices have been completely destroyed. New premises are being obtained and they expect to recommence manufacture at an early date. The true spirit of the bulldog breed is illustrated by a postscript to their circular letters “DOWN BUT NOT OUT!”’

November 1941, page 285:

‘Mr J. Mieses informs us that a tournament has taken place in Munich last September. … Mr Mieses calls this a “Quisling” tournament and thinks that Opočenský, Foltys, Roháček, Rabar, Nielsen, Cortlever and even – Mr Mieses regrets to add – Dr Alekhine ought to be ashamed to go as guests to Germany.

It is with extreme regret that we must subscribe to Mr Mieses’ criticism. The facts of the case appear to lend credence to the political and literary activities with which the present champion has been credited. We have studiously refrained from quoting from his alleged writings because even now we do not think it possible for Dr Alekhine to be the author of the farrago of absurdities and contradictions which have been attributed to him.

… We have nothing to add to what Mr Mieses says; the strictures passed by such a kindly, gentlemanly and fair-minded man are a terrible indictment.’

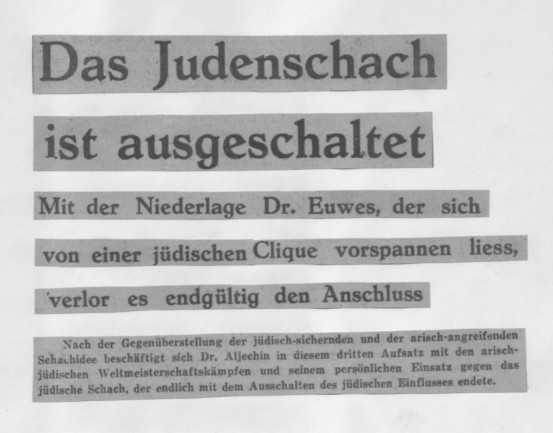

January 1942, page 10:

‘The “New Order” in Germany is busy on chess literature. The outstanding text-book in the German language is Dufresne’s Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, which has held the field for some 60 years. From 1901 to 1937 it was periodically revised, and brought up to date by J. Mieses, and so remained a thoroughly modern work.

As its popularity could not be gainsaid, it had to be “aryanized”, and a new revision was entrusted to a 100 per cent Aryan master [Max Blümich (1886-1942)].

It will hardly be credited that the names of “non-Aryan” players have been omitted from the historical section, including Kolisch, Zukertort, Steinitz, Lasker, Rubinstein, etc. Not only that, all their most brilliant games which adorned earlier editions have been eradicated, although a few of their games were allowed to remain – those they lost! This is on a par with the maintenance of “Aryan” superiority in chess by the simple expedient of excluding non-Aryan competition.

There is only one word for it – lunacy. “Whom the gods wish to destroy …”.’

August 1942, page 178:

‘The German comments on the tournament [Salzburg, 1942] make hilarious reading. It was acclaimed as an event of the highest importance since, with the exception of Euwe, the world’s six strongest players were competing!! Apparently, Russians, Czechs and Americans don’t count.’

January 1943:

‘In the course of these notes, we referred to the grandiose plans by which German chess, supported by German propaganda, proposes to organize European chess, without reference either to the probable outcome of the present crisis or to the wishes of the bulk of players in the invaded countries.

As opposed to this crazy edifice of wantonly abused temporary power, would it not be a reasonable proposition for the organizers of British chess to get together now and to examine where our present system may be at fault and what remedies could be applied after the last shot has been fired?’

May 1943, page 104:

‘Referring to our remarks in our last issue about L. Prins, Mr Belinfante says there is a much more serious reason why his name does not appear in any tournament. The Germans have barred Jews in occupied countries from playing chess even in private clubs. For the same reason, Landau’s name does not appear anywhere. As nearly all Jews in Holland are in concentration camps or have been sent to Poland, very few, it is feared, will survive the ordeal.’

March 1944, page 49:

‘One of our supporters has written to us in protest against our reporting chess news from countries with which we are at war; according to him, we should ignore them and not give them gratuitous publicity.

… We have given chess news from Germany in an entirely objective spirit, except when we criticized, perhaps unnecessarily, propagandist attempts to institute a “new order” in chess also by the creation of a new International Chess Association, which apparently intended the permanent exclusion of such unimportant agglomerations as the USA, Russia and the British Empire. We need not have wasted criticism on such a ludicrous, megalomaniac fatuity, of which very little is heard nowadays.’

August 1944, page 173:

‘The news of this unspeakable tragedy [the death of Vera Menchik] will be received by the chess world with sorrow and with abhorrence of the wanton and useless robot methods of a robot people.

One shudders at the heritage of hatred which will be theirs, but their greatest punishment will come with their own enlightenment.’

January 1945, page 1:

‘A striking feature of the past year is the falling off in the number of tournaments held in Germany and German-occupied territory on the Continent. The great activity in this direction in the early years of the War was a matter of propaganda. But propaganda loses its value in the face of hard and incontrovertible facts.’

Note: The above article originally appeared on pages 50-55 of the Winter 2000 issue of Kingpin. The front cover of the magazine’s Spring 2000 issue had been inspired by the front page of the 1 April 1938 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter reproduced above.

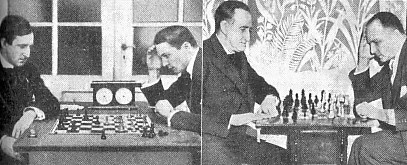

CHESS, 14 January 1938, page 155 featured two photographs of Frank Marshall in play against Kurt Lüdecke, with the following explanation:

‘Frank Marshall and Kurt G.W. Lüdecke started a game on 31 July 1914, the photograph on the left being taken in the course of the game. The War broke out and Marshall had to make an expeditious getaway to Holland, England and home. On 1 December 1937 the game was resumed and concluded. In the meantime Marshall had held the US Championship for some two decades and his opponent had written the sensational book I Knew Hitler, published last year.’

(3449)

A rather different version of the Marshall v Lüdecke story was given on page 114 of the November-December 1937 American Chess Bulletin:

‘A game begun by Frank J. Marshall and Kurt G.W. Lüdecke, author of I Knew Hitler, at Mannheim two days before the world war broke out, was reproduced from a photograph when they met again the other day, after 23 years, at the Hotel Shelton in New York. Failing to recall whose move it was, they did not finish it. Instead they contested three rapid transit games, Marshall winning two and drawing one.’

I Knew Hitler was subtitled ‘The Story of a Nazi Who Escaped The Blood Purge’. On pages 29-30 of the London, 1938 edition Lüdecke wrote:

‘One reason I think I was never a gambler at heart is that I can lay claim to the quality of patience – even the profound patience required of a chessplayer. Chess was an obsession with me. I can still spend hour after hour over the board, unconscious of the world around me.

On an evening at the Café Continental [in Paris], however, my concentration was broken into by the raucous cry of a newsboy. I was about to spring the decisive move in an intricate mate combination, and I bought the boy’s paper so that I could send him on his way. As I put it to one side, the headline caught my eye.

It announced the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo. “C’est la guerre”, I said in thoughtless prophecy, and turned again to a matter of importance. I moved a pawn. “Check!”

... In July we motored to Heidelberg, following the lure of an international chess tourney at nearby Mannheim. There the war burst upon us.’

A player named Lüdecke was mentioned on page 58 of the February 1910 Deutsche Schachzeitung as having participated in a team match between Kiel and Bremen in Altona on 9 January that year, but there would seem only a slight chance that it was Kurt G.W. Lüdecke.

Adolf Hitler and Kurt Lüdecke

(3453)

Before I Knew Hitler goes back on the shelf we mention for the record another reference to chess in Kurt Lüdecke’s memoirs. Pages 454-455 relate an episode from 1932 when he ‘visited Hitler in his luxurious, modern flat of eight or nine beautiful, large rooms covering the entire second floor of 16 Prinzregentenplatz, in one of the better sections of the outer city [of Munich]’:

‘With visible pride, Hitler conducted me to his library, an attractive, cosy room, lined with several thousand books, many of them gifts, ranged in built-in bookshelves. I was delighted when, leading me straight to a section filled with atlases, geographies and travel books, he pointed out the inscribed copy of Ashwell’s World Routes that I had sent him from New York. “I’m told this is a very fine job of editing. However did you do it? I wouldn’t have credited you with the patience to deal with so much detail.” He waved me on into his study, a room which, despite its simple and practical furnishings, somehow reminded me of a college boy’s study fitted out by rich parents.

“Perhaps playing chess and those months in jail taught me to be patient when I must”, I replied.’

(3456)

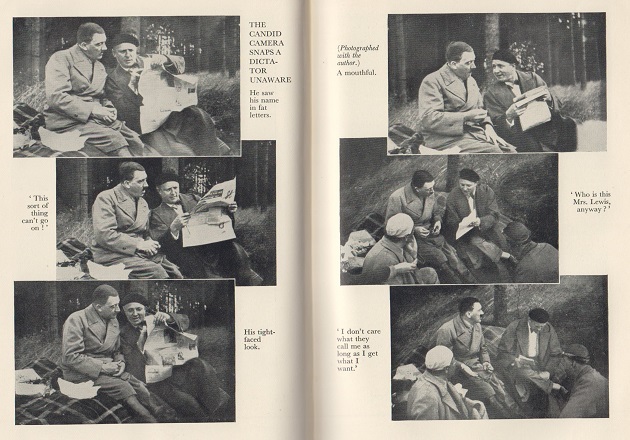

Two photographs of Kurt G.W. Lüdecke with Adolf Hitler were shown in C.N.s 3453 and 3761. They were from a set of six in the plate section of Lüdecke’s book I Knew Hitler (London, 1938), between pages 472 and 473:

(11109)

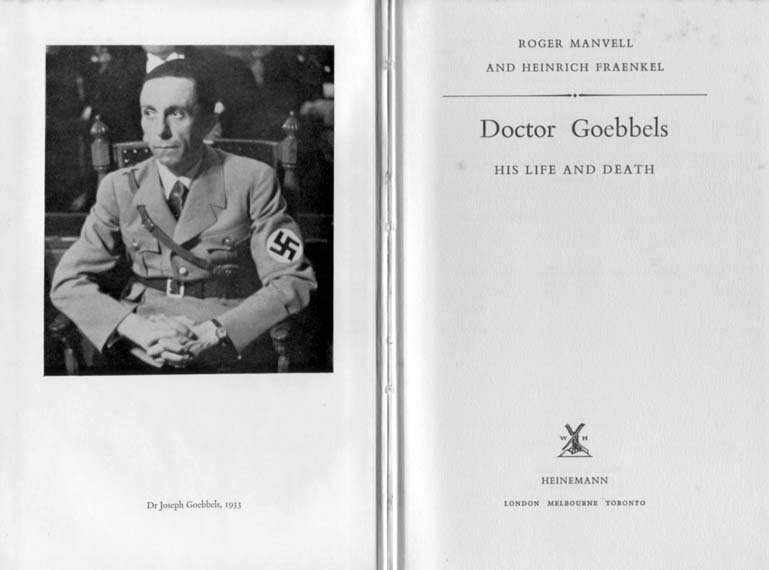

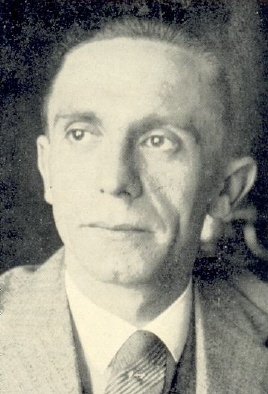

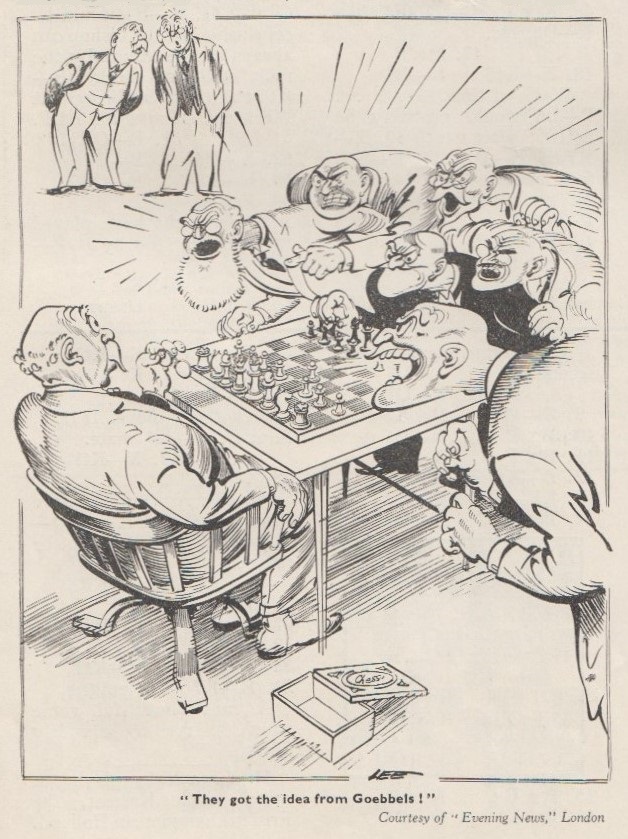

Page 290 of A. Alekhine Agony of a Chess Genius by P. Morán (Jefferson, 1989) quoted from the New York Times of 16 July 1933 a chess-related reference to ‘Dr Paul Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda and Enlightenment, who is a devotee of the game’. Was he?

(3718)

No information has yet been found about Joseph Goebbels’ alleged interest in chess. In 1960 ‘Assiac’ (i.e. Heinrich Fraenkel) co-authored a biography of him with Roger Manvell, but we have noted no references to chess in it.

(3804)

Joseph Goebbels

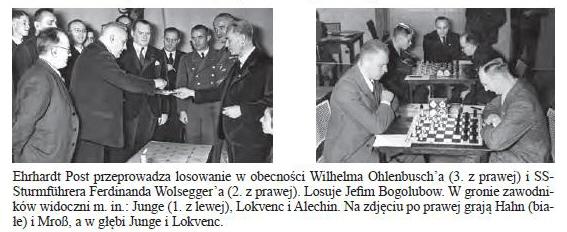

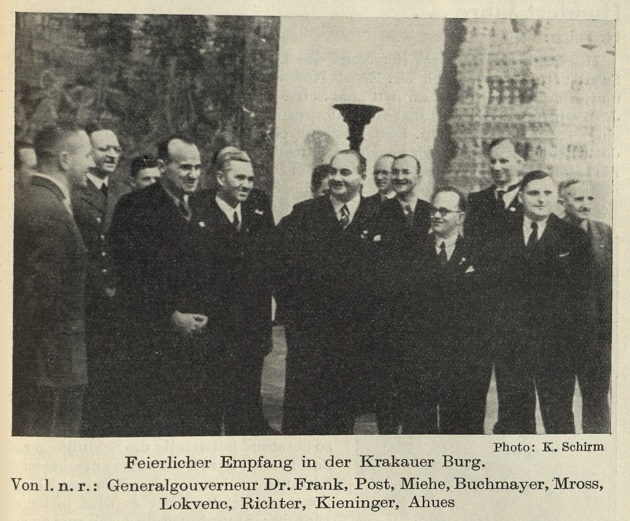

From page 659 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L.M. Skinner and R.G.P. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) comes this passage concerning Munich, 1941:

‘The tournament started on 8 September ... A large reception was held on the evening of the first day. This was attended by leading lights from the Nazi Party, the State Government and the Wehrmacht. ... The Chief Executive of the Großdeutscher Schachbund, Ehrhardt Post, spoke on the importance of forming a new chess organization ... In his speech, he also acknowledged the debt due to the two Reichsministers present, Dr Josef Goebbels and Dr Hans Frank, for their generous support of the tournament.’

See also page 150 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 October 1941. Did any German newspapers of the time have photographs of, or reports on, the reception?

(4381)

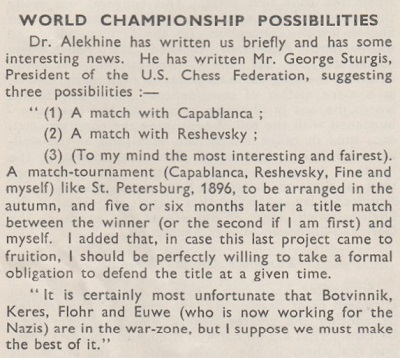

From page 93 of CHESS, January 1940:

(9637)

Concerning William Joyce (‘Lord Haw-Haw’), see C.N. 11446.

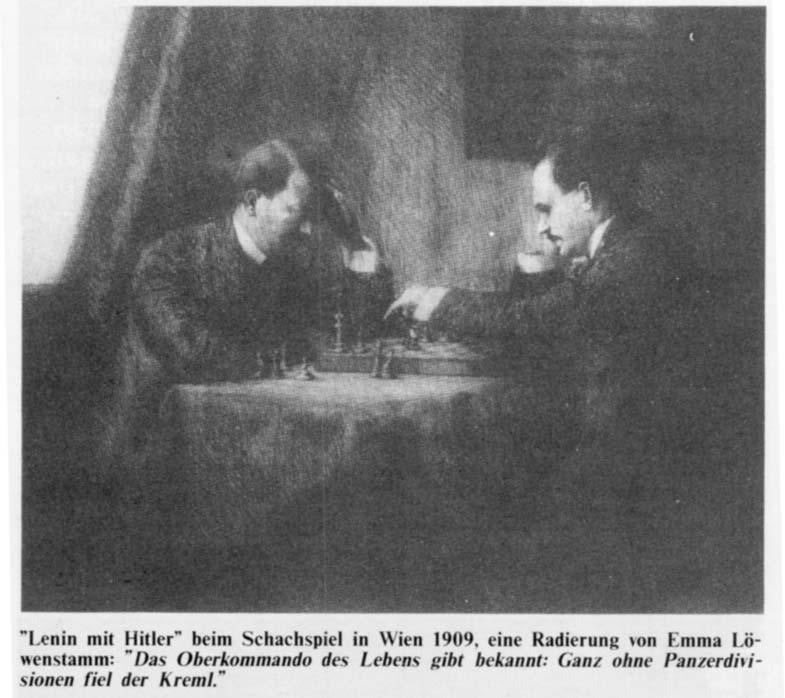

C.N. 3958 mentioned a claim that Adolf Hitler was a chessplayer. It emanated from one of the chess world’s least credible sources, yet we note that a reference to Hitler having possibly played chess with Lenin in Vienna in 1909 appeared on page 188 of Persönlichkeiten und das Schachspiel by B. Rüegsegger (Huttwil, 2000):

‘Die jüdische Malerin Emma Löwenstamm (1879-1941) brachte in Wien Hitler und Lenin zusammen, um sie gemeinsam zu malen. Sie lud beide ins Atelier von Julius von Ludassy ein. Im Donau-Kurier Ingoldstadt vom 19. July 1984 erwähnt Bernd Kallina in seinem Artikel die damals angefertige Zeichnung, wo Lenin auf der Rückseite die Worte “Lenin mit Hitler” hingeschrieben haben soll.’

Weiter wird erwähnt, dass sich beide 1909 in Wien getroffen und zusammen Schach gespielt haben ...’

No Hitler-Lenin illustration was provided in Rüegsegger’s book, but now Edward Hamelrath (Dresden, Germany) sends us the following picture:

Our correspondent writes:

‘This etching comes from the extreme right-wing (and now defunct) magazine Europa Vorn (spezial Nr. 1/4. Quartal 1991), in an article entitled “Ungeist aus der Flasche” by a “v. Freisaß”. The article is just a rambling diatribe on twentieth-century world politics and makes no reference to the picture itself. It is not even clear exactly what the title is – either “Lenin mit Hitler” or “‘Lenin mit Hitler’ beim Schachspiel in Wien 1909”. (The “Das Oberkommando ...” comment under the picture was simply plucked out of the text.) In any case, the Hitler figure corresponds more to his appearance in the mid-1920s than in 1909.’

Further information on this bizarre matter will be welcomed. In the meantime readers are, of course, advised to view it with extreme circumspection.

(4055)

Yury Ryabokon (Moscow), who is a producer with the Russian broadcasting company NTV, asks whether more information is available about this purported picture of Hitler and Lenin (published in the magazine Europa Vorn, spezial Nr. 1/4. Quartal 1991), which a correspondent sent us in 2005.

At that time, the picture became widely known and gave rise to a barrage of speculation, though no facts. Is it possible to do better today?

(10878)

See A Purported Picture of Hitler and Lenin Playing Chess.

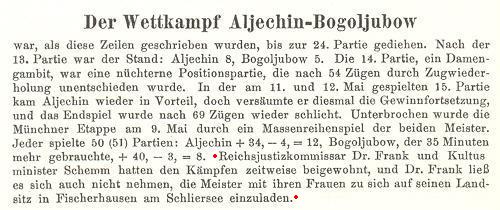

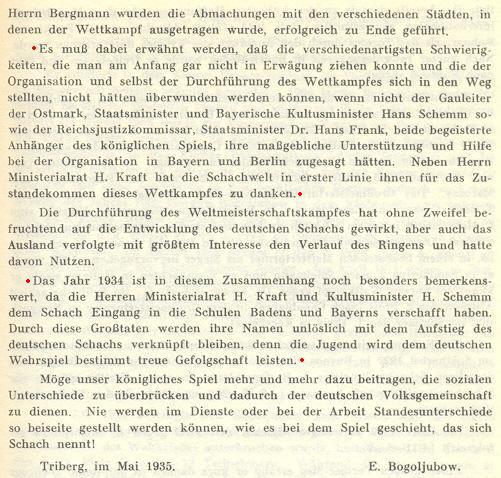

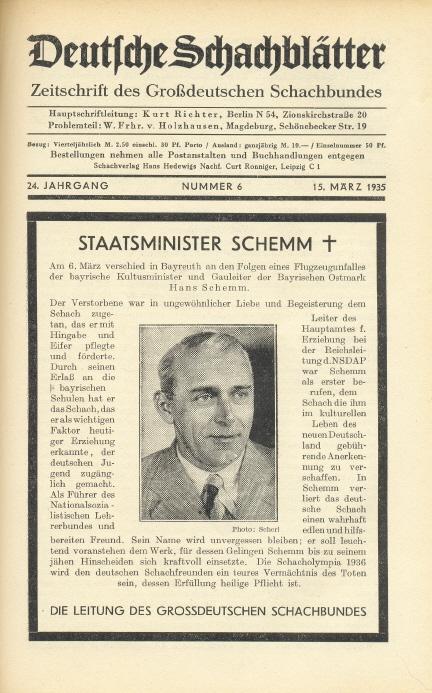

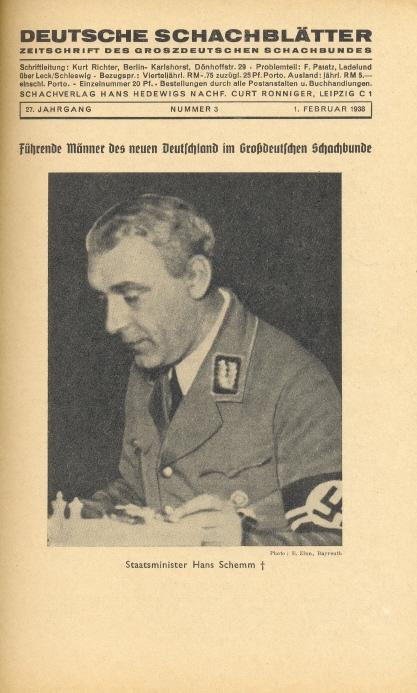

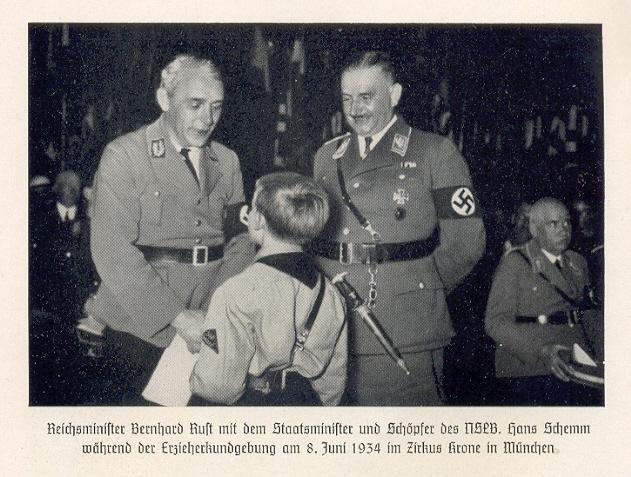

C.N. 3527 described Hans Frank as ‘the most prominent Nazi leader to be strongly interested in chess’. Another official who was keen on the game was the Gauleiter Hans Schemm, and both he and Frank were mentioned in a report about the 1934 world championship match on page 162 of the June 1934 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

On page 5 of his book on the match, Schachkampf um die Weltmeisterschaft (Karlsruhe, 1935), Bogoljubow paid tribute to both Frank and Schemm for supporting the contest:

Already when Bogoljubow’s words were written, Schemm was dead, having been killed at the age of 43 in an aeroplane crash on 5 March 1935 (Deutsche Schachzeitung, March 1935, page 71). News of his death took up the entire front page of the Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 March 1935, and he was featured again in the 1 February 1938 issue:

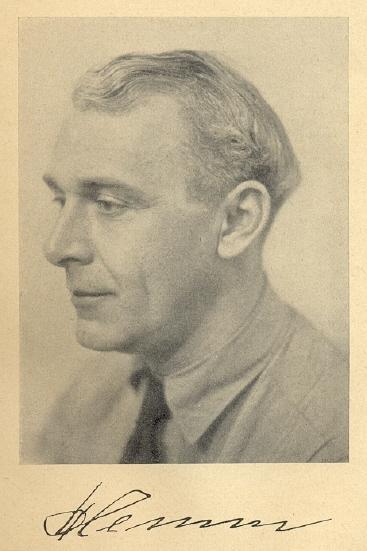

Bogoljubow’s book Schach-Schule was first published in 1935, but we also have the 1940 edition. The latter was dedicated to Schemm and had a page consisting solely of a picture of him with his signature:

Hans Schemm

(4820)

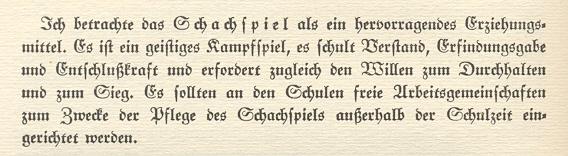

A quote about chess from the Nazi official Hans Schemm (1891-1935):

Our translation:

‘I regard chess as an outstanding educational aid. It is an intellectual battle-game which provides training in reasoning, inventiveness and determination, while also requiring the will for survival and victory. In schools, chess clubs should be set up to cultivate chess outside of school hours.’

Source: Hans Schemm spricht – Seine Reden und sein Werk by G. Kahl-Furthmann (Bayreuth, 1935), page 178.

Below are two photographs of Schemm. The first was published opposite page 192 of Hans Schemm, volume one by Benedikt Lochmüller (Bayreuth, 1935), whereas the picture of him standing alongside Bernhard Rust (1883-1945) appeared in Hans Schemm Ein Leben für Deutschland by Bernd Lembeck (Munich, 1936).

(4833)

A number of C.N. items have discussed, desultorily, the subject of Bogoljubow and the Nazis. For instance, Reuben Fine’s unsubstantiated claim that Bogoljubow had some of his rivals put in concentration camps by the Nazis was dealt with on pages 183-184 of Chess Explorations and pages 191-192 of Chess Facts and Fables, whereas page 92 of the latter book referred to Bogoljubow’s attempts at rehabilitation vis-à-vis FIDE in 1946. Has any chess writer ever published a rigorous, extensive study of Bogoljubow’s conduct during the Third Reich?

Below are three photographs from Deutsche Schachblätter:

Bad Harzburg, 1938 (15 July 1938 issue, page 215)

Cracow/Krynica/Warsaw, 1940 (1 December 1940 issue, page 192). Ludwig Fischer was hanged for war crimes in 1947.

Bogoljubow v Euwe match, Carlsbad, 1941 (1 August 1941 issue, page 113)

(4821)

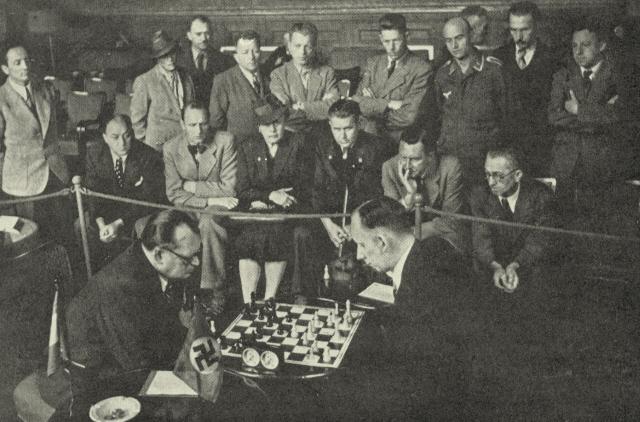

From C.N. 5648:

A. Alekhine v K. Richter, Munich, 1941. Source: page 71 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943)

John Kuipers (Delft, the Netherlands) draws attention to pages 109-110 of Hitlers Berlijn 1933-1945 by H. van Capelle and A.P. van de Bovenkamp (second edition, Soest, 2007), which has a brief paragraph about Heinrich Müller (born in 1900), the head of the Gestapo from 1939 until the end of the Second World War:

‘Net als zijn directe baas Heydrich en zijn ondergeschikte Eichmann, die beiden viool speelden, was ook Müller muzikaal en speelde graag piano en als het even kon schilderde hij landschappen. Bovendien was hij een hartstochtelijk schaker en bridger. Eenmaal in de week kwamen Eichmann en andere hoge Gestapo-functionarissen in de Corneliusstrasse 22 bijeen om een partijtje te schaken. De kettingrokende Müller hield bovendien van een goed glas rode wijn en van cognac.’

Our correspondent’s translation reads:

‘In common with his immediate superior, Heydrich, and his subordinate, Eichmann, both of whom played the violin, Müller was musical and loved to play the piano and, when time permitted, he also painted landscapes. In addition, he was a passionate chess and bridge player. Once a week Eichmann and other leading Gestapo officers gathered at Corneliusstrasse 22 to play a game of chess. The chain-smoking Müller was also fond of a good glass of red wine or cognac.’

Mr Kuipers notes that Corneliusstrasse 22, Berlin was Müller’s private address, where he lived alone (his wife and children having remained in Munich). Müller disappeared in May 1945.

(5751)

The present feature article (see above) includes a quote from page 269 of the June 1933 BCM:

‘In his anxiously awaited speech to the Reichstag on 17 May, Herr Adolf Hitler made a curious comparison, which is thus reported in the telegraphic accounts. Speaking of the Nazi Storm Troops, he said: “If Storm Troops are to be called soldiers, then even the chess and dog-lover clubs are military associations.” Well, we know that chess has been called effigies belli; but it has not yet gone to the dogs!’

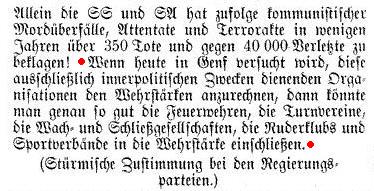

We see no reference to chess in the official transcript of Hitler’s speech in Verhandlungen des Reichstags. The closest passage is the following (first column of page 51):

Page 1 of the New York Times, 18 May 1933 stated that ‘it was said to have been the first time that he had ever delivered a written speech’. An English translation of the full text was given on page 3, and the relevant sentence read:

‘If today an attempt is being made in Geneva to count these organizations exclusively serving political purposes as part of the military force, then one might as well include fire departments, gymnastic societies, rowing clubs and sports associations in the military force.’

(5902)

Addition on 22 February 2025:

We have found a report of the speech that mentions chess, on page 5 of the 17 May 1933 edition of the Evening Standard:

‘If the Storm Troops are to be called soldiers, then you may as well regard the fire brigade, the gymnastic societies, the watchmen’s association, the rowing clubs – even the chess and dog lover clubs – as military associations.’

Caution is required. It will be noted that this version appeared the same day as the speech was delivered.

Santhosh Matthew Paul (Ernakulam, Cochin, India) quotes from page 7 of Hess Flight for the Führer by Peter Padfield (London, 1991):

‘Returning to the front with the 1st Company of the 1st Foot in November, he was engaged in more trench warfare in the Artois sector, and early the following year, 1916, took part in the battles for Neuville St Vaast. Then, struck by a throat infection in February, he spent most of March and April in various hospitals with acute laryngal catarrh. Years later he could recall his pleasure as the only patient at St Quentin to beat a Berlin chess master who took on 12 opponents at once. He had been introduced to the game by his mother when he was 12 while he and his brother, Alfred, had been in quarantine for scarlet fever.’

Page 353 stated that the source of the information about the simultaneous display was a letter from Hess to his wife, Ilse, in December 1947.

Can any further information be found concerning Rudolf Hess and chess?

(6167)

Lawrence Totaro (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to an article ‘When I played chess with Rudolf Hess’ in the Evening Chronicle (Newcastle) of 24 November 2007. Maurice Williams reported that he had played against Hess when on guard duty at Spandau Prison in 1951.

(6173)

Lawrence Totaro notes that page 121 of Standing Up to the Madness by Amy Goodman and David Goodman (New York, 2008) reported:

‘“We got more information out of a German general with a game of chess or Ping-Pong than they do today, with their torture”, said Henry Kolm, 90, an MIT physicist who had been assigned to play chess in Germany with Hitler’s deputy, Rudolf Hess.’

Mr Totaro notes, however, that Kolm’s own ‘Military’ webpage referred to chess games against ‘Colonel Rudolf Hesse, a Prussian faculty member of the German War College and prime strategy advisor to Hitler’. Kolm added:

‘Hesse wanted to play chess every time I visited him in his cabin, and he was very talkative over the chess board. He usually won, and hated the few times he lost.’

Subsequently, Mr Totaro checked the matter with Kolm, who informed him:

‘Chess was simply a way to befriend German generals and get them to talk freely. I never played with Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy ...’

(6196)

Klaus Junge (see C.N. 6433)

‘A remarkable feature of the “Blitzkrieg” is the quite disproportionate amount of damage inflicted on concerns dealing in chess materials and books.’

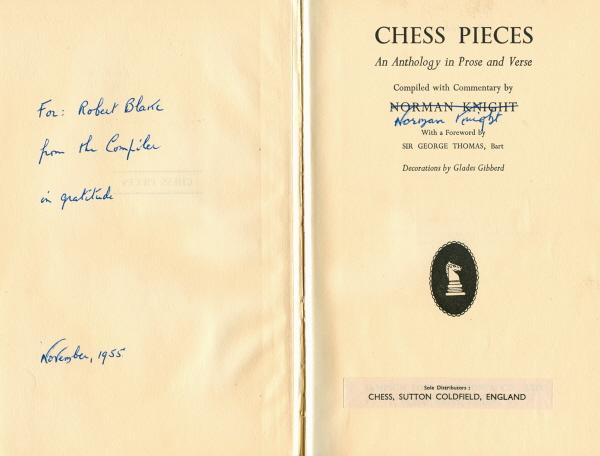

That observation from page 166 of the June 1941 BCM is quoted above. We add a comment by Norman Knight on page xi of the Preface to his compilation Chess Pieces (London, 1949):

‘My task has been made the harder by reason of an “incident” during the night of 12 [sic] May 1941, when several German incendiary bombs fell in the British Museum Library, and it so happened that of the nine million books stored there it was the chess section that suffered most severely.’

Is Knight’s assertion factual or scaccocentricity?

(6551)

C.N. 6551 asked whether Norman Knight was correct to state that German bombs which fell on the British Museum Library in 1941 inflicted particularly severe damage on the chess section.

Michael Chambers (London) of the Humanities Reference Service of the British Library informs us:

‘Books on chess did indeed suffer heavy war damage as the shelfmark ranges occupied by books on the “useful arts” (including sport and games) were among those badly affected by the bombs which fell on the British Museum during World War II.

I did a sample search of the “General printed books pre-1975” subset of the British Library Integrated Catalogue for the term “chess” in the records for pre-1945 publications. Not all records for publications on the subject of chess will include this term, of course, but my search yielded over 850 results, more than 15% of which were evidently destroyed as a result of this enemy action.

Not all war-damaged items can be readily identified from the Integrated Catalogue, but the presence of “D-” before a shelfmark indicates a book destroyed in this way, and shelfmarks beginning “Mic.A” usually indicate war-damaged material replaced by microfilm copies from the Bodleian Library or elsewhere. The search results mentioned above included more than 70 instances of shelfmarks with a “D-” prefix and more than 60 instances of shelfmarks beginning “Mic.A”. Most of these items were published in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (the latest destroyed item in my search results dated from 1939.)’

(6574)

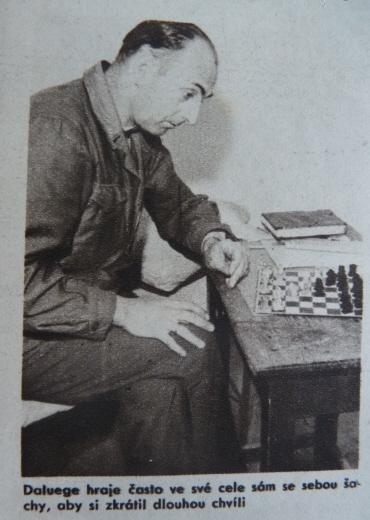

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends a photograph of the Nazi official Kurt Daluege (1897-1946):

Source: Svět v obrazech, 13 October 1946, page 7. The caption states that he often played chess by himself in his prison cell, to alleviate the boredom.

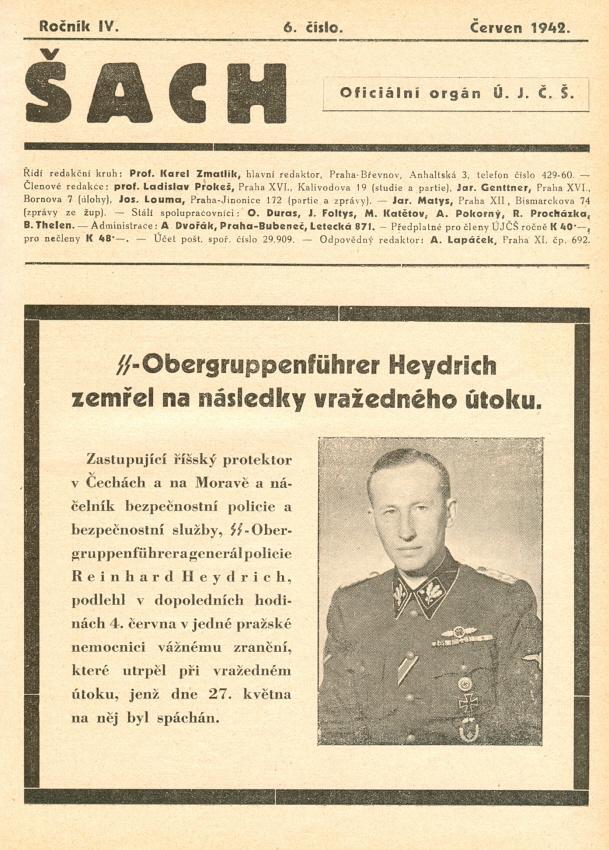

Later that month, Daluege was hanged. He had been the Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, in succession to Reinhard Heydrich (1904-42). The latter, we add, was featured on the front page (page 81) of the June 1942 issue of the Czech magazine Šach, following his assassination.

(7074)

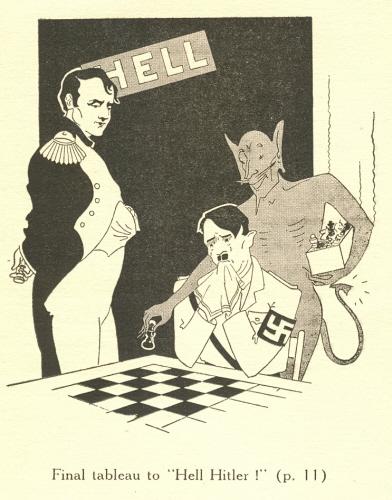

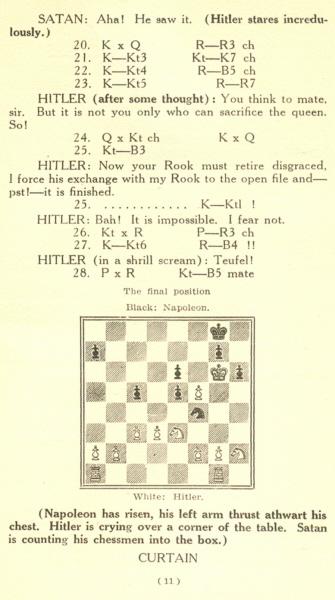

An item on pages 178-179 of A Chess Omnibus noted that C.J.S. Purdy attempted to make light of Hitler in a satirical one-act play ‘Hell Hitler’ in “Among These Mates” (Sydney, 1939), a book which he published under the pseudonym Chielamangus. The dramatis personae were Shade of Napoleon, Shade of Hitler, and Satan, and the play was founded on a spoof Hitler v Napoleon game: 1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 d3 Be6 5 Bxe6 fxe6 6 Be3 Nd7 7 Bxc5 dxc5 8 Nbd2 Ne7 9 O-O O-O 10 Nc4 Ng6 11 c3 Qf6 12 Qb3 Nf4 13 Ne1 Qg5 14 Kh1 Rf6 15 Qxb7 Raf8 16 Qxc7 R8f7 17 Rg1 Qh4 18 Qc8+ Nf8 19 Ne3 Qxh2+ 20 Kxh2 Rh6+ 21 Kg3 Ne2+ 22 Kg4 Rf4+ 23 Kg5 Rh2 24 Qxf8+ Kxf8 25 Nf3 Kg8 26 Nxh2 h6+ 27 Kg6 Rf5 28 exf5 Nf4 mate.

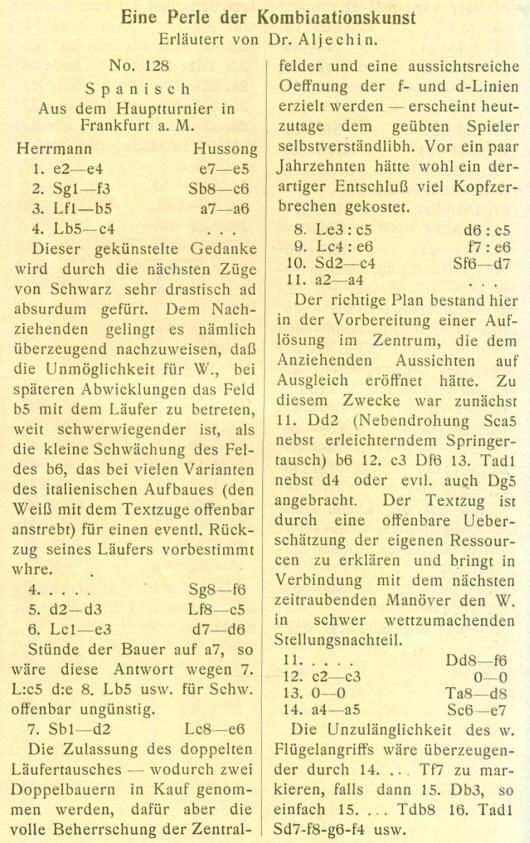

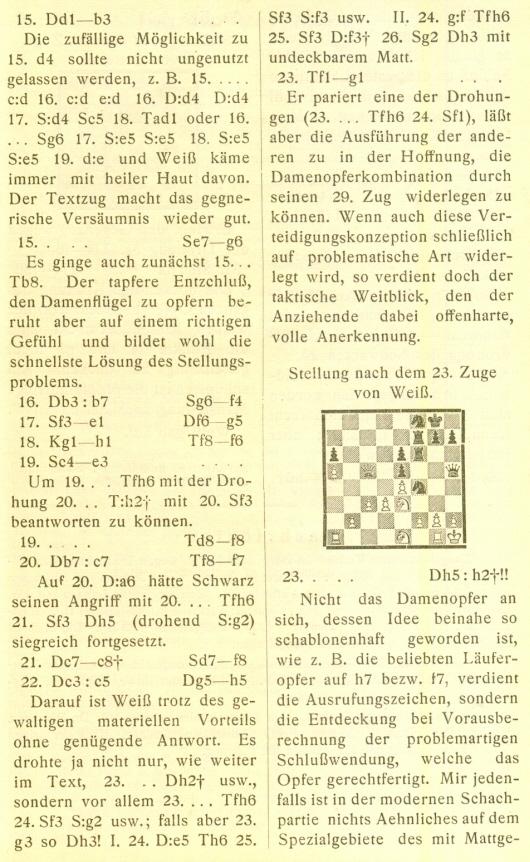

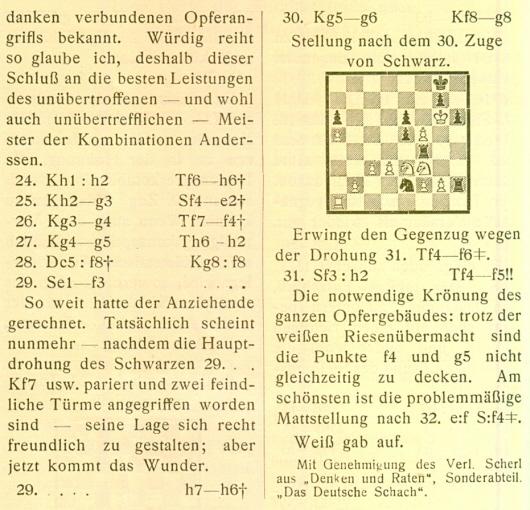

This score was based on the famous brilliancy F. Herrmann v H. Hussong, Frankfurt, 1930 published on pages 314-315 of the October 1930 Deutsche Schachzeitung, October 1930, and, with Alekhine’s notes taken from Denken und Raten, on pages 340-342 of the December 1930 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten:

Below, from Purdy’s book, is the illustration on page 6 and the conclusion of the play on page 11:

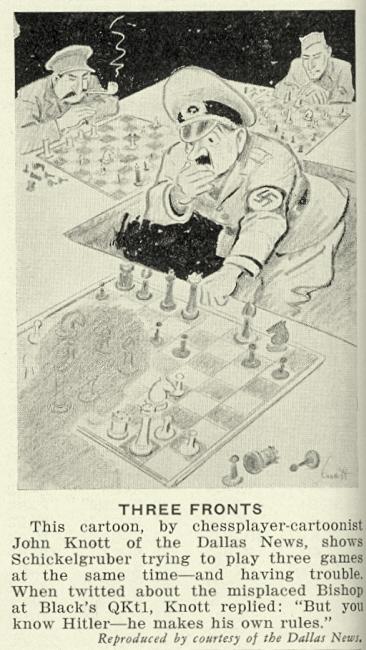

In conclusion, we add the following from page 8 of the October 1944 Chess Review:

(7402)

Thomas Höpfl (Halle, Germany) points out footage of an anti-Communist rally (Ljubljana, 29 June 1944) in which Milan Vidmar can be seen (beginning at about 2’20”).

The first part of the coverage also shows Vidmar (at about 4’45” into the item).

(7864)

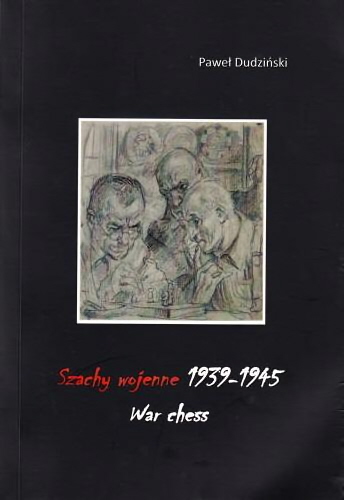

Paweł Dudziński (Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland) has sent us a copy

of his book Szachy wojenne 1939-1945 War chess (Ostrów

Wielkopolski, 2013). Richly illustrated with games, photographs

and documents, the historical narrative is remarkably detailed.

The work is a 299-page soft-cover publication in Polish, with a

summary in English on pages 273-277.

A sample page, although one of the lighter ones:

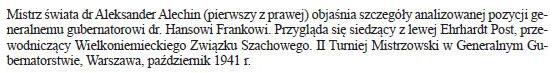

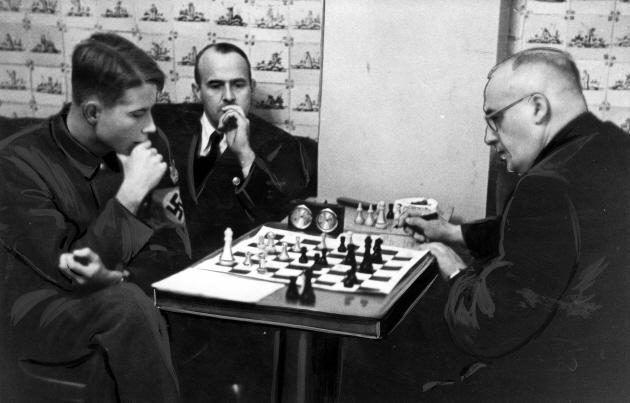

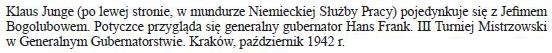

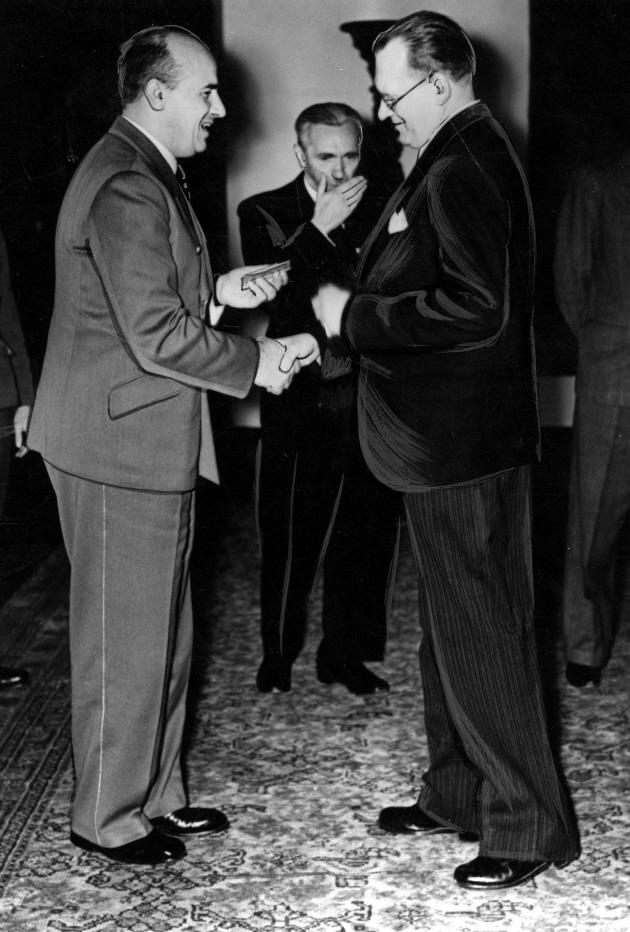

Mr Dudziński has authorized us to reproduce here a number of photographs, and the scans provided by him are accompanied below by the book’s captions.

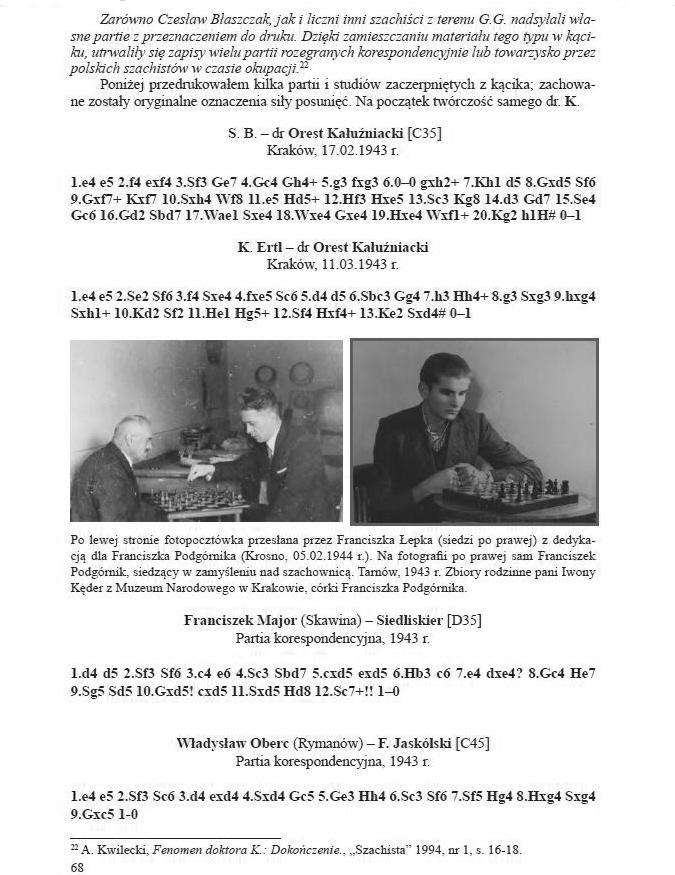

From page 76:

From page 185:

From page 187:

From page 192:

From page 193:

Only a limited number of copies of this exceptional (and, we understand, inexpensive) book are available, and we shall be pleased to forward to the author any messages from readers who wish to buy it.

(8204)

Wolfgang Franz (Oberdiebach, Germany) notes that the photographs in C.N. 8204 can be viewed, together with many others, at the Polish Zbiory NAC on-line website, e.g. by searching for Szachowe or Alechin.

(8208)

It is difficult to know what to make of Alekhine’s remark in brackets at the end of a letter published on page 161 of the August 1941 CHESS:

(8964)

Our feature article on Hans Frank includes many photographs, including the following (from the August 1937 Deutsche Schachblätter) of Post, Zander, Frank, Euwe, Miehe and Bogoljubow, published under the heading ‘Weltmeister Dr Euwe in Berlin’:

C.N. 9890 gave these two photographs (scans provided by the Cleveland Public Library):

Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1940, page 169

Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1941, page 162.

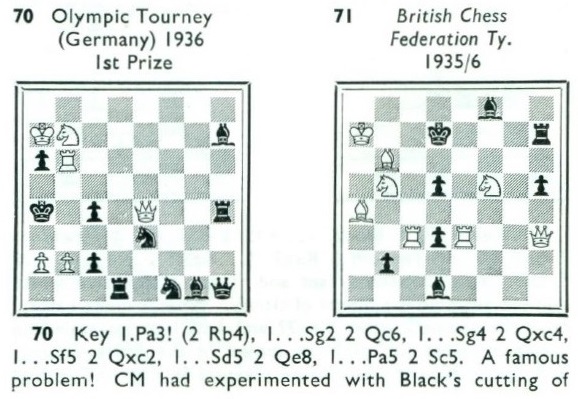

Drawing attention to his article about Comins Mansfield on the website of the British Chess Problem Society, Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) sends us an extract from pages 13-14 of Comins Mansfield MBE: Chess Problems of a Grandmaster by Barry Barnes (Sutton, 1976):

(11122)

See too:

Karlis Ozols

Patriotism, Nationalism, Jingoism and Racism in Chess

Max Blümich

A Letter from Bobby Fischer to Pal Benko

Front cover of Fischer’s copy of Mein Kampf, now owned by David DeLucia and shown here with his authorization.

The 1936 Munich Chess Olympiad

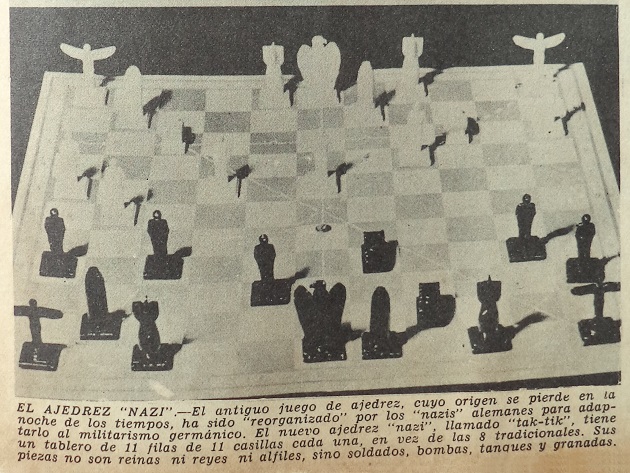

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) sends two photographs in the 26 December 1937 edition of Carteles:

(11850)

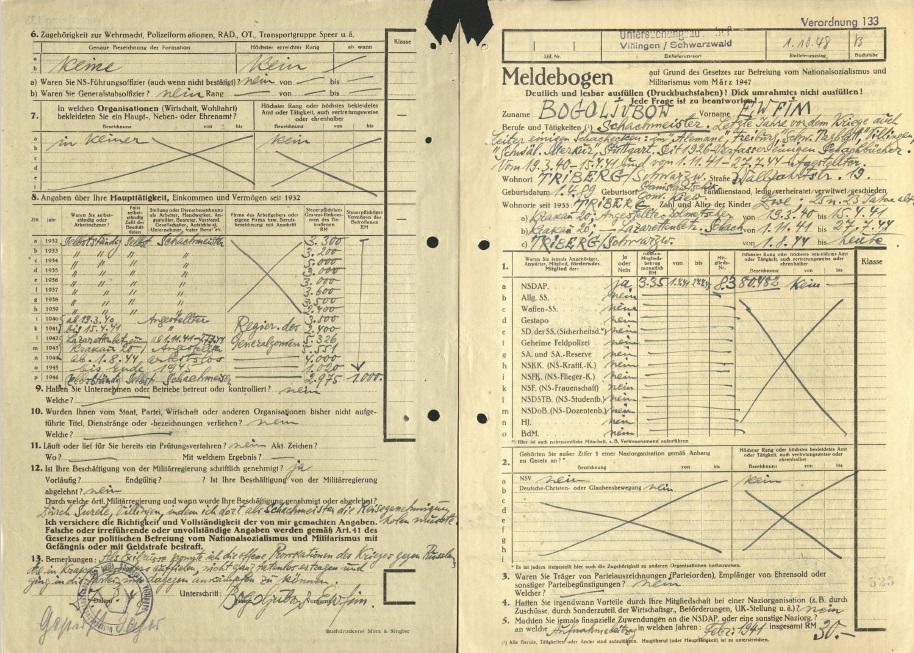

From Bernd-Peter Lange (Berlin):

‘After the Second World War, all German members of the National Socialist Party were required by the Allies to fill in a questionnaire (Meldebogen) for political examination. Bogoljubow’s was written in his own hand in September 1948 in the French zone of occupation where he was resident. It gives a great deal of information about, in particular, the years 1940-44, when he was in the service of Hans Frank, the Governor General of German-occupied Poland. He was employed firstly as a translator and interpreter (Ukrainian and Russian) in the Propaganda Department and then, for a longer period, as a chess instructor in German military hospitals in the Generalgouvernement and for chess-related tasks such as the design and distribution of a new chess set.

The denazification questionnaire gives precise details of his times of employment, payment received, dates of his party membership, and his political justification for having joined the Nazi Party.

A discussion of these texts – together with passages (some hitherto forgotten) related to Bogoljubow and chess matters in the vast service-diary of Hans Frank – has been prepared for the 1/2021 edition of the German-language magazine KARL, under the title “Bogoljubow im Generalgouvernement”. Later in 2021 there will be an expanded version in English, discussing Bogoljubow’s career from 1933 onwards.’

Our correspondent has forwarded us a PDF file which includes the questionnaire completed by Bogoljubow.

(11859)

See too: A Purported Picture of Hitler and Lenin Playing Chess.

Addition on 28 July 2023:

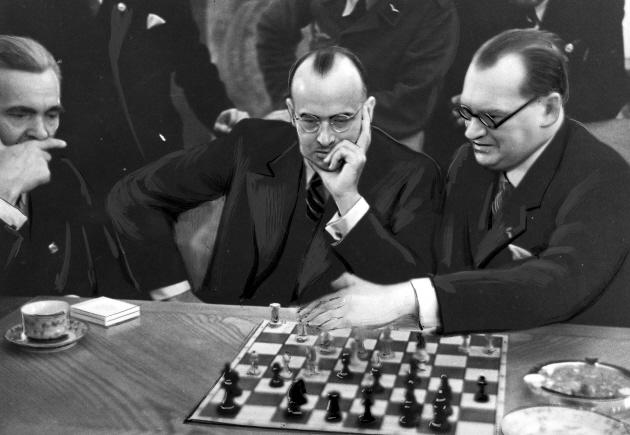

From his collection Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) shares this photograph taken at Salzburg, 1942. It shows Junge, N.N. and Alekhine watching a game played by Paul Schmidt:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.