Edward Winter

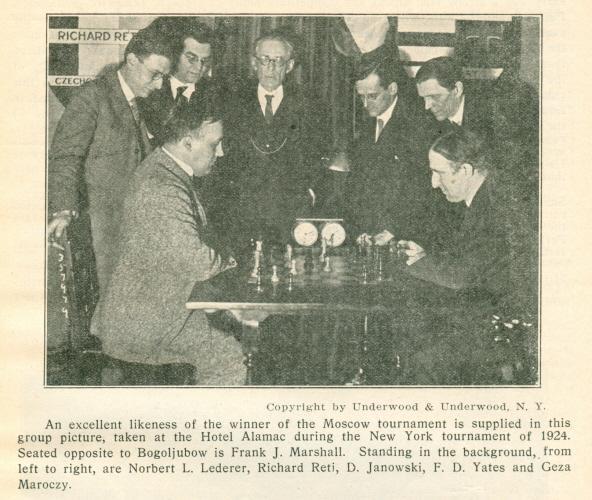

Source: page x of the New York, 1924 tournament book.

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) raises two matters concerning New York, 1924 on the basis of information in the tournament book: a) the speed with which the event was organized and b) the pairing system used.

We offer some supplementary facts from the 1924 volume of the American Chess Bulletin, whose editor, Hermann Helms, was on the board of the tournament directors.

Page 1 of the January 1924 issue announced the proposed tournament:

‘First steps were taken at a meeting in New York on 18 January, having in view a possible gathering of the world’s leading experts as early as 17 March.

As we go to press, there is no absolute certainty as to its taking place, as planned. It is sufficient to say that a number of good men and true are bending all their energies to make it so. Should success crown their efforts, then the congress will be quite unique in the annals of the game, at least in so far as rapidity of action is concerned.

This much can be said. Thanks to good use of the cable, the readiness of several European masters to come over has been ascertained.’

And from page 2:

‘Although a total of nearly $10,000 will be required to defray the expenses, including the prizes, as well as the transportation of several European experts, close upon $4,000 was pledged as a starter [at the committee’s meeting on 18 January].

The members of the committee undertook to raise most of the balance through subscriptions within a fortnight, after which word was to be sent to Europe to the masters who are in readiness to come whenever the call is issued.’

Page 25 of the February 1924 Bulletin stated:

‘Since the announcement made in the January issue of the Bulletin, matters have progressed famously in connection with the New York International Chess Masters’ Tournament. It is now an assured fact. New York, therefore, will be the scene for a gathering of the world’s most famous masters, the like of which is not apt to be witnessed again in our generation.’

Page 4 of the tournament book reported:

‘With the hearty co-operation of Dr Arthur A. Bryant [the Treasurer] and Mr Helms, the preparations at this end were carried forward with the least possible delay, and on 8 March we were able to welcome the masters at the docks with the satisfying knowledge that everything was ship-shape, barring, perhaps, some of the masters. Several unforeseen incidents helped to maintain the interest and contribute a bit of anxiety, chiefly the illness of Capablanca from a severe attack of la grippe, which made his participation in the tournament somewhat doubtful up to the last minute.’

The pairing system was set out in point 19 of the tournament rules (pages 27-28 of the February 1924 American Chess Bulletin):

‘The draw will be made according to the Berger system and the players will draw their own numbers before beginning of the tournament. The number of the round to be played each day will be decided by draw and announced 15 minutes before beginning of playing hours. The first half of the tournament must be completed before any of the rounds of the second half are drawn.

The draw for numbers took place on 11 March (American Chess Bulletin, March 1924, page 49), and the first round of play was on 16 March.

Mr Niessen asks whether other major tournaments have handled pairing in a similar way.

(6608)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) quotes from the Hastings, 1895 tournament book edited by Horace F. Cheshire (London, 1896):

‘The order of play and pairing will be decided by the president drawing lots publicly immediately before the commencement of the Tournament. The future pairing will depend on this, but will not be known until the morning of each day. (Page 6.)

‘The president then made the draw of the names to match with the numbers with which the pairings had been arranged; ... this draw determined the first moves and the pairings of all the rounds, but not the order in which the rounds were to be played. The draw was then made for the round for the day, and the president explained that he, or in his absence the director in charge, would make this draw each day before play commenced.’ (Pages 10-11, in the section entitled ‘The Opening Day’.)

‘No-one knew, till the morning of each day, who would meet ...’ (Page 367, under ‘The Innovations’.)

(6631)

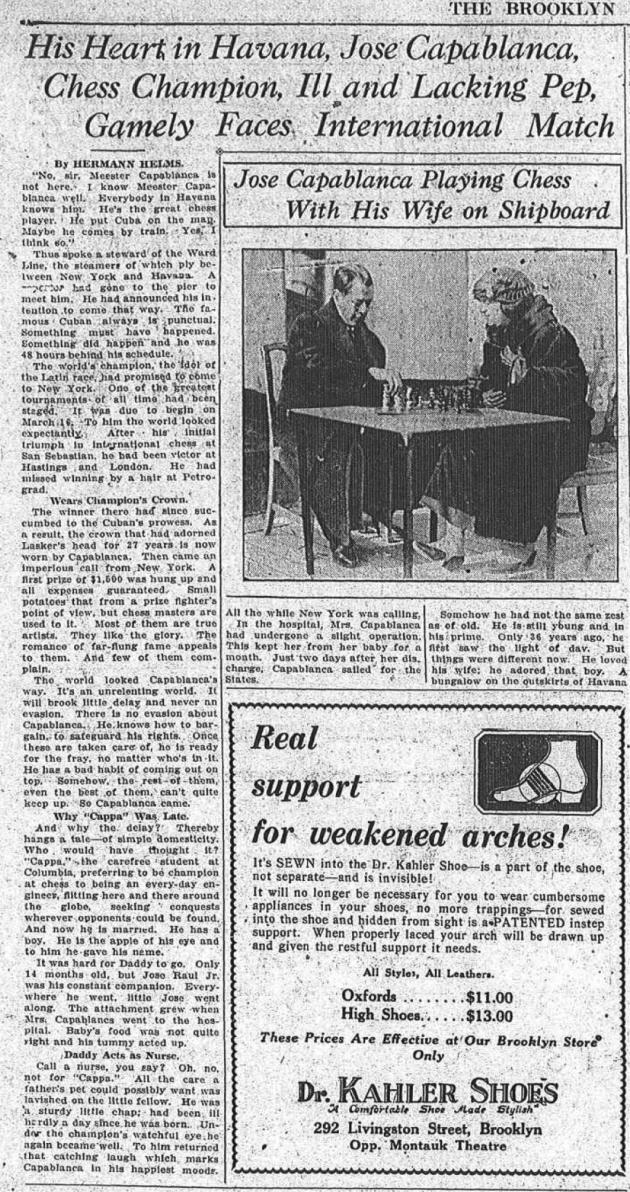

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends this article from the 16 March 1924 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (page A11):

Larger version of the second part

(7097)

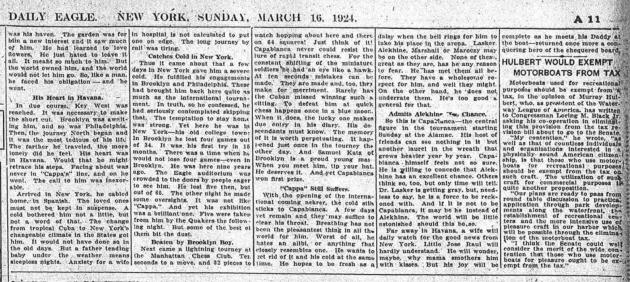

Baltimore Sun, 2 March 1924, page 4, part 1, section 2

The article is notable for the accuracy of Charles Jaffe’s prediction about New York, 1924 and for his general remark about the arduousness of such events:

‘... playing in an international chess tournament requires as much physical endurance as a six-day bicycle race.’

(10926)

Concerning the bicycle race analogy, see C.N. 6881 below.

Information is sought about Siegbert Tarrasch’s absence from New York, 1924 and, in particular, about a claim by Al Horowitz on an unnumbered page in Solitaire Chess (New York, 1962):

‘What really broke his spirit in the end was his non-admittance to the entry list of the great New York tournament of 1924. Lasker, who had been chosen to compete, had been wrangling for a higher retainer. The committee warned him that, if he didn’t accept the offer, Tarrasch would be his replacement. Lasker quickly came to terms.’

(8663)

Supplying links to parts one and two of an article by Hanon W. Russell about New York, 1924, Pete Klimek (Berkeley, CA, USA) notes that the first part has some references to Tarrasch.

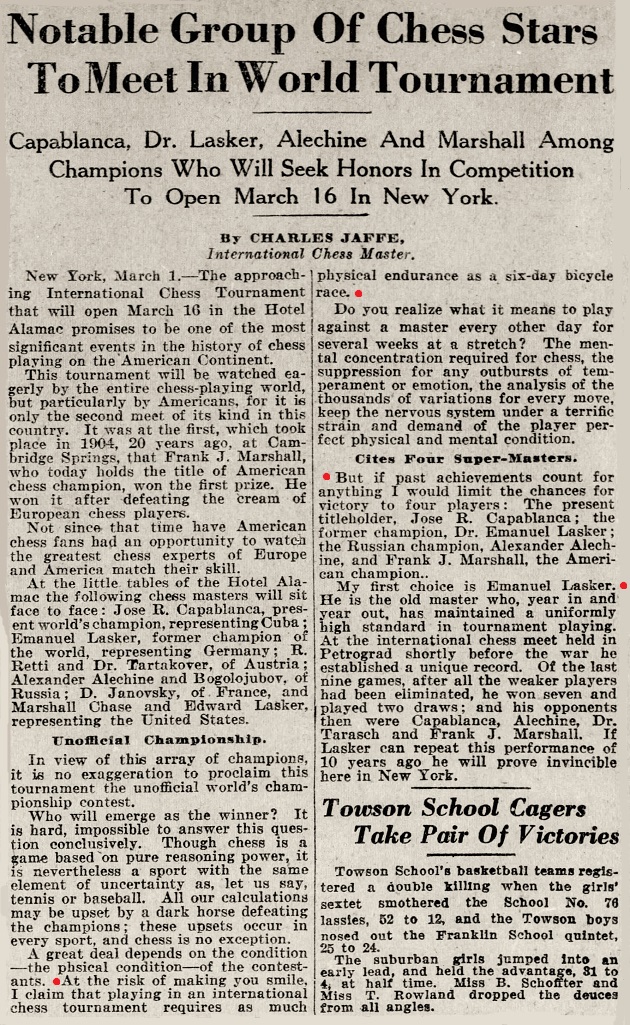

C.N. 3351 presented a photograph (New York, 1924) from Homenaje a José Raúl Capablanca (Havana, 1943):

Our comment was: ‘Any reader who thinks that we are merely reproducing a famous shot is invited to look more closely.’

(5372)

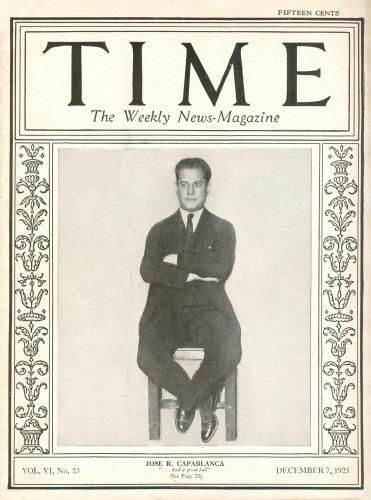

The front cover of Time, 7 December 1925:

The photograph is merely a cut-out from a New York, 1924 group shot.

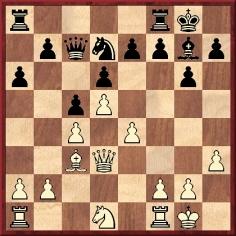

Few players are slow to claim a brilliancy, but Edward Lasker once uncorked a superb move – and did not even realize it. Heidenfeld’s Lacking the Master Touch (pages 10-11) discusses a position from the game Ed. Lasker-Marshall, New York tournament, 30 March 1924:

Position after 27...Ne7-f5

Lasker played 28 Bf4, which helped to relieve his difficult position, although he later lost the game through subsequent sins. But, as Heidenfeld, points out:

‘What Lasker executed with the move 28 B-B4 is one of the very rare anti-Turtons ever seen in play, though it is a well-known combination in problem composition. It consists in forcing the attacker who wishes to double two pieces on the same gait in such a way as to have the stronger piece in front and the weaker behind (called the Turton in the jargon of problemists) into playing the weaker piece across the so-called “critical square” (here Black’s K4) and thus into reversing the planned line-up ...

... Now it is absolutely impossible for even the most modest chess master who knows of these contexts and has the good fortune to bring off such a rare combination, not to crow over it and dismiss the game, as Lasker does, with the words: “Marshall made a complicated combination which permitted me to equalize, when he could have won within a few moves. I lost the game through a blunder in the seventh hour of play ...” Thus, though Edward Lasker included a chapter on problems in his work Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood, his knowledge of this field is clearly deficient – otherwise he would have hailed his game against Marshall as an extraordinary “find” – just as I am doing now. Without a record of this game the literature of chess would be distinctly poorer.’

Presumably the fact that Lasker lost the game helped him shut the brilliancy from his mind. Alekhine in the tournament book merely remarks that after 27...Ne7-f5, ‘White now defends himself capitally’.

Any more examples of the anti-Turton theme in actual play, or instances of a master never realizing how clever he had been?

(553)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘I was very interested in C.N. 553 since I have a small collection of game positions featuring problem themes, although up to now no example of an anti-Turton. It is curious to note that the second brilliancy prize winner from New York, 1924 (Marshall-Bogoljubow) featured an example of the Turton theme (18 Bb1 Bd7 19 Qc2).’

Position after 17...c6-c5

(681)

See The Anti-Turton Theme in Chess.

Alekhine and Réti had opposite views on the worth of Capablanca’s sixth move in his game (as White) against Yates at New York, 1924 (1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bf4 Bg7 5 e3 O-O 6 h3). Alekhine, in the tournament book, said it was ‘not exactly necessary ... after the text-move, Black obtains some counter-play, the defense of which will demand all of the world champion’s care’. Réti, however, calls 6 h3 ‘a move of genius’ (Homenaje a Capablanca, pages 185-186) For him it was ‘the most profound move of the entire game’. He explains its idea as follows (our résumé): if Black is to make the most of the king’s bishop he will need to play, eventually, either ...e5 or ...c5. Capablanca’s plan is to prevent the former, so as to force the latter. This will transfer the battle to the queen’s side, where White will have every chance of securing an advantage, owing to the absence on that flank of Black’s dark-squared bishop. Capablanca, in view of the position of his own bishop in the centre of the board, prevents the centre from becoming the battlefield by 6 h3. He does not allow Black to play 6...Bg4, followed by ...Nbd7 and ...e5.

(916)

Concerning Yates’ loss to Capablanca, see also C.N.s 547 and 2138 in José Raúl Capablanca Miscellanea.

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) enquires about a matter discussed on pages 195-197 of our book on Capablanca: Lasker’s allegation that owing to a defective clock he lost 20 minutes during his defeat at the hands of the Cuban at New York on 5 April 1924. We quoted from De Telegraaf of 3 January 1927 Lasker’s strong attack on the tournament organizers in explanation of his refusal to participate in New York, 1927.

Our correspondent asks whether the 1924 clock dispute was public knowledge before Lasker’s article appeared nearly three years later.

(5080)

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) cites the following from page 74 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 30 April 1924:

‘Auffällig ist eine Mitteilung, die Dr. A. Seitz, der als Zuschauer dem Turnier beigewohnt hat, über die Partie Capablanca-Dr. Lasker macht. Danach wäre die Niederlage L’s die Folge eines Uhrendefekts. L sei infolge dieses Defekts, der zur Folge hatte, daß im kritischen Augenblick beide Uhren gingen, in Zeitnot geraten u. habe das Remis übersehen.’ [Our English translation: ‘A noteworthy report comes from Dr A. Seitz, who attended the tournament as a spectator, regarding the Capablanca-Dr Lasker game. It states that L.’s defeat was the result of a defective clock; owing to that fault, which caused both clocks to be running at the critical moment, Lasker fell into Zeitnot and overlooked the draw.’]

More generally, our correspondent refers to a sentence written by Seitz on page 146 of the May 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘Dem Turniersekretär konnte man nicht das Lob allzu großer Unparteilichkeit geben.’ [‘The tournament secretary could not be praised for excessive impartiality.’]

Finally, Mr D’Ambrosio quotes a passage from the report about New York, 1924 on page 3 of volume one of Schachjahrbuch 1924 by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925):

‘Über ihre Aufnahme und ihren Aufenthalt haben sich die Turnierteilnehmer sehr günstig ausgedrückt. Selbstverständlich gab es die regelmässigen Klagen über gewisse Rücksichtslosigkeiten einzelner Meister, wie gewöhnlich so auch hier, auch fehlten nicht Beschwerden wegen Parteilichkeit des Turnierleiters von deutscher Seite.’ [‘The participants in the tournament expressed great satisfaction with their welcome and stay. Of course, there were the regular grievances about certain inconsiderate behaviour by individual masters, as is usual and as occurred here too, and there was no lack of complaints of favouritism by the tournament director, from the German side.’]

(5088)

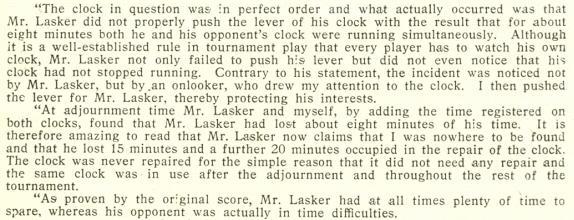

Luca D’Ambrosio submits a further report on the dispute regarding the game Capablanca v Emanuel Lasker, New York, 1924 (from Deutsches Wochenschach, 15 June 1924, page 110):

Our translation:

‘The apparent clock defect in the Capablanca-Lasker game. Dr A. Seitz stated in his tournament reports, among personal attacks on the New York tournament director, N.L. Lederer, that Lasker’s defeat against Capablanca was due to a clock defect, as a result of which at the critical moment both clocks were running and L., who was in Zeitnot, overlooked the draw. Ignoring the personal attacks, we briefly mentioned this information on page 74 on the assumption that an explanation would not be lacking. In a communication Mr Lederer has now drawn to our attention the fact that Dr Seitz did not have access to the playing tables and therefore knew of the matter only by hearsay. “I noticed”, observes Mr Lederer in this respect, “that during the game Dr L. did not press the ‘off’ lever on his clock far enough and that both clocks were running. When play was broken off at six o’clock, we noted precisely the time difference, which was around eight minutes. It should be remarked here that Dr L. was not in Zeitnot at any time. On the contrary, before the end of play C. was in considerable Zeitnot and twice after the piece sacrifice did not make the best moves (Qf3 instead of Qe2 and Nxd6 instead of g4 [sic]). When play resumed at eight o’clock both players were, of course, out of Zeitnot, and the move which, according to Dr L.’s analysis, offered Black the prospect of a draw (Bd5 instead of Qe6) took place long after play had been interrupted ... Dr L. has, of course, never made a remark which could be interpreted as meaning that he lost the game for any reasons other than those having to do with chess, and he spoke about his opponent’s play with the greatest respect; he merely remarked that Qe6 was the losing move and that Bd5 would probably have given him a draw, and analysis will surely bring a final verdict on this.” Mr Lederer goes on to express his regret over the derisive and denigrating comments made by Dr Seitz about the committee and the tournament management, which are as unjustified as they are untrue. He says that this could cause the men whom we have to thank for the organization of the tournament not to repeat their efforts, undertaken purely in the interests of chess, if the result of their work is mean-spirited attacks by people who have enjoyed the hospitality of the Manhattan Chess Club and the Hotel Alamac. In the end, Dr Seitz was requested no longer to enter the premises of the Manhattan Chess Club.’

When the Lasker affair blew up in the United States in January 1927, Lederer wrote as follows regarding the clock incident on page 71 of the March 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

The rules for New York, 1924 were given on pages 27-28 of the February 1924 American Chess Bulletin. The time-limit was 30 moves in the first two hours and 15 moves an hour thereafter. The playing hours stipulated there (13.30-17.30 and 19.30-23.30) were subsequently amended to 14.00-18.00 and 20.00-00.00 (American Chess Bulletin, March 1924, page 49). For Capablanca’s score-sheet of his victory over Lasker see page 80 of A Picture History of Chess by Fred Wilson (New York, 1981).

(5098)

Emanuel Lasker’s absence from New York, 1927 was due to a bitter dispute with the organizers of New York, 1924, and he issued a lengthy statement on the affair at the end of 1926. Much confusion and additional controversy arose because the text was published – in German, Dutch, Spanish and English – with many variants and discrepancies. Richard Forster has sifted through all available versions of the statement in a special article presented here: Lasker Speaks Out (1926).

(11704)

In a short item on pages 78-79 of All About Chess (New York, 1971) Al Horowitz wrote:

‘If any game is to be dubbed the “Immortal Zwischenzug”, it is this one, played in the great tournament of New York in 1924.’

After Tartakower’s 9 Bxb8 Capablanca played his famous move 9...Nd5.

(4107)

Further to the discussion on Pal Benko and ...b5 (see C.N.s 3957 and 3967), Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany) raises the wider question of the earliest occurrence in play of the general ideas behind the Benko Gambit (not necessarily in the first few moves). He proposes Marshall v Réti, New York, 1924, which was annotated on pages 37-40 of Alekhine’s book Das Grossmeister-Turnier New York 1924 (Berlin and Leipzig, 1925) and on pages 18-20 of the English translation.

The game began 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 c4 Bg7 4 Nc3 O-O 5 e4 d6 6 Bd3 Bg4 7 h3 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Nfd7 9 Be3 c5 10 d5 Ne5 11 Qe2 Nxd3+ 12 Qxd3 Nd7 13 O-O Qa5 14 Bd2 a6 15 Nd1 Qc7 16 Bc3

Réti played 16...Ne5, and Alekhine wrote: ‘Bereitet das folgende allzu kühne Bauernopfer vor – im Bestreben, gewaltsam remis zu vermeiden.’ [‘Preparing for the subsequent over-daring sacrifice of the pawn with the intention of avoiding a forced draw.’]

After 17 Qe2 b5 Alekhine commented:

‘Diesen Bauern konnte Weiß ruhig nehmen, da Schwarz Schwierigkeit gehabt hätte, dafür positionellen Ersatz zu erlangen, z.B. 18 c4-b5: a6-b5: 19 De2-b5:! c5-c4 (offenbar die beabsichtigte Pointe des Bauernopfers) 20 Lc3-e5: Lg7-e5: (oder 20...Tf8-b8 21 Db5-c6 Dc7-c6: 22 d5-c6: Lg7-e5: 23 Ta1-c1 Le5-b2: 24 Tc1-c4: mit Vorteil, da Schwarz den a-Bauern wegen 25 Tc4-c2 usw. nicht nehmen darf) 21 Sd1-e3 c4-c3 22 b2-c3: Dc7-c3: 23 Ta1-c1 und Weiß hätte zum mindesten ein sehr leichtes Remis gehabt. Nach der Ablehnung des Opfers wird er dagegen erst hart kämpfen müssen, um es zu erreichen.’ [‘White could safely have captured this pawn, as Black would have difficulty in obtaining positional compensation, for instance: 18 PxP PxP 19 QxP P-B5 (clearly the reason for the pawn sacrifice) 20 BxKt BxB (or 20...KR-Kt 21 Q-B6 QxQ 22 PxQ BxB 23 QR-B BxP 24 RxP with advantage, as Black dare not capture the QR pawn, on account of 25 R-B2) 21 Kt-K3 P-B6 22 PxP QxP 23 QR-B, and White would have had at least a very easy draw. After the refusal of the sacrifice, on the other hand, he can now reach that goal only after hard fighting.’]

The game continued 18 cxb5 axb5 19 f4 Nc4 20 Bxg7 Kxg7 and was drawn at move 50.

(5457)

On page 232 of the August 1970 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld wrote:

‘... a phrase like “Alekhine’s Best Games” is really ambiguous: it may mean two entirely different things, viz. (a) the games Alekhine played best and (b) the objectively best games in which Alekhine was a participant (in which the standard of the game is achieved by both partners) – thus he need not necessarily have won them. This, in fact, is the basis of my anthology Grosse Remispartien.

In fact, it is little short of ludicrous that Alekhine’s Best Games does not contain his draw against Marshall at New York, 1924, where a most original and new strategic conception by Marshall is met by an amazing tactical finesse of Alekhine’s, the whole (drawn) game being one of the greatest ever played. It is similarly ludicrous that Golombek’s anthology of Réti’s Best Games is without his draw against Alekhine at Vienna, 1922 – which has been christened the Immortal Draw and which even Alekhine does not pass over in his own collection. Similarly some game collections of Tal’s are deprived of the fantastic draw against Aronin at the 24th Soviet championship (Moscow, 1957) – a game of which Keres stated in a much-acclaimed article that one could not do justice to Tal’s achievement in that tournament without coming to grips with it.’

(7049)

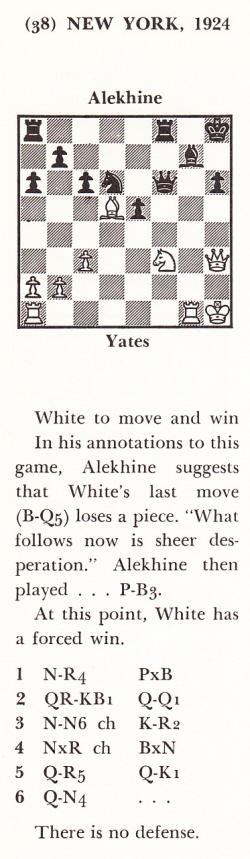

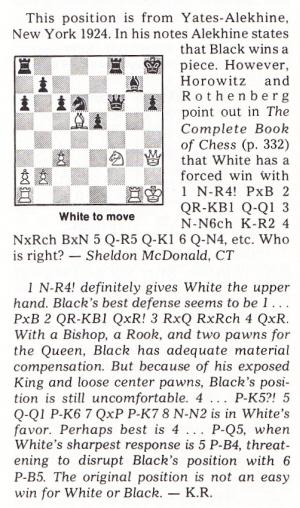

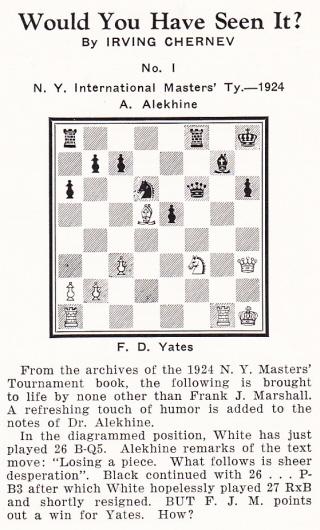

A position from Yates v Alekhine in the first round of the New York, 1924 tournament:

Yates played 29 Bd5, and on pages 17-18 of the tournament book (New York, 1925) Alekhine wrote:

‘Losing a piece. What follows is sheer desperation.’

The continuation was 29...c6 30 Rxg7 Kxg7, and White resigned after Black’s 35th move.

It was later found that White could have played 30 Nh4, but when was the discovery made?

Below is what appeared on page 332 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963):

The matter was taken up by Sheldon McDonald of Connecticut on page 16 of the January 1978 Chess Life & Review, in the ‘Ask the Masters’ column, and a reply from Ken Rogoff followed:

The Complete Book of Chess was the new title of the Horowitz/Rothenberg work when it was reissued in 1969. The co-authors’ text leaves the reader to infer that they found 30 Nh4, but such was not the case. Horowitz’s magazine, Chess Review, had the following on page 291 of the December 1938 issue:

The solution on page 301 (also with incorrect move numbers throughout):

Nowadays the possibility of 30 Nh4 is regularly mentioned, though without attribution to Marshall or anyone else. See, for instance, page 43 of the second volume of the Chess Stars work on Alekhine (Sofia, 2002). For his part, Alekhine annotated the game briefly on pages 73-74 of La Stratégie, April 1924 (notes reproduced from Le Canada) and on page 99 of Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1924, but neither set of notes has anything of relevance to the play under discussion here.

(7746)

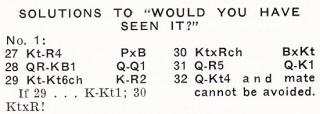

From page 105 of The Amazing Book of Chess by Gareth Williams (Godalming, 1999), in the section on Capablanca:

‘His losses became so rare that on one occasion the front page headline of the New York Times read “Capablanca Loses”.’

That sounds even more dramatic than what Harold C. Schonberg wrote on page 166 of Grandmasters of Chess (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

‘At the New York, 1924 tournament he lost to Réti. So unexpected was that loss, so unbeatable had Capablanca been, that the New York Times commemorated Capablanca’s loss in a headline: CAPABLANCA LOSES/1ST GAME SINCE 1914. (The Times for once was inaccurate, for Capablanca had lost a game to Chajes in New York in 1916.)’

So, just how eye-catching was the newspaper’s front-page story on 23 March 1924, the day after the Cuban’s loss to Réti?

Contrary to the statement in the New York Times, the Cuban’s unbroken run (apart from the loss to Chajes in 1916) stretched back to his defeat by Tarrasch, and not Lasker, at St Petersburg, 1914.

(8205)

C.N. 8205 showed the report of Capablanca’s loss to Réti on the front page of the sports section of the New York Times, 23 March 1924.

There was no mention of the game on the newspaper’s very front page.

(8217)

See also Chess as Front-Page News.

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘When and why did the practice of announcing mate in tournament and match games end?’

Is there unanimity today among administrators and officials on the procedure applicable if a player announces mate during a game (and, additionally, in case of an incorrect announcement)? Information will also be welcomed on the most recent games to contain mate announcements. Have there been many significant specimens since Marshall v Bogoljubow, New York, 1924, in which White announced mate in five moves at move 38?

(8329)

See Announced Mates.

From Janowsky Jottings:

‘Even at New York, 1924, the masters agreed that for the first four hours of play Janowsky was equal to any player in the world.’ So declared the obituary of Janowsky on pages 28-30 of the February 1927 American Chess Bulletin, which also stated that around the first few years of the century he ‘was the strongest player in the world’.

From pages 151-152 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

On page 260 of the April 1974 Chess Life & Review Edward Lasker made the peculiar claim that it was only during the New York, 1924 tournament that Emanuel Lasker learned of the Marshall Gambit:

‘I had told him [Emanuel Lasker] on one of our morning walks in Central Park that during the war, when of course no chess news crossed the Atlantic, Marshall had invented a pawn sacrifice against the Ruy López which he had tried against Capablanca in a tournament in New York in 1918, but despite his tremendous attack, Capablanca succeeded in refuting it over the board. I told him how this “Marshall attack” went …’

A group photograph from page 173 of the December 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

(4992)

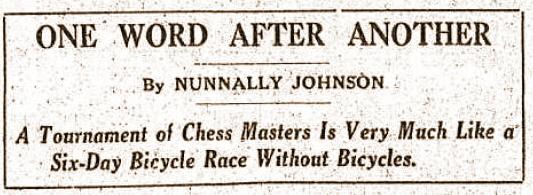

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) brings to our attention an article by an eminent writer on page 24 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 March 1924:

‘One Word after Another

By Nunnally Johnson

A Tournament of Chess Masters Is Very Much Like a Six-Day Bicycle Race Without Bicycles.Hand to hand, at such close grips that their fierce, hot breaths intermingle furiously, 11 giants are battling for world supremacy up at the Alamac Hotel in Manhattan.

They are chessplayers, the finest in the world, and probably the slowest, and their battle of the century is more sedately known as the International Chess Masters’ Tournament. Capablanca, Ed Lasker, F.J. Marshall, Bogoljubow – here are names to conjure with wherever the lure of chess has blown its hardy call. And if you would know what they look like, they look like chessplayers.

For thrill, for life and excitement, for – what is that charming French word which goes in here – verve? – yes, for verve, for all of those things, the only other athletic contest comparable to chess as the masters play it would be a six-day bicycle race. Perhaps, to be more accurate, it would be best to say, a 12-day bicycle race.

Chess fiends all over New York look forward to this grappling of the giants. Today, perhaps at the very moment you read this, they are crowding the long room of the second floor of the Alamac, being shushed by the attendants to preserve silence. It is quiet, so quiet, so very quiet indeed that the heavy rumble of furious thinking can be heard distinctly. If only it were a little rowdier one might fancy that it was a funeral.

The contestants, the men of all nations who have fought their way to the very top of the heap, sit, two-by-two, at tables along one wall. Two stop-clocks look down with them at the board. Cigarette butts, coffee cups, water glasses, the debris of all-night parties, are at their elbows. There is a steady buzz of “sh-sh-sh-sh” whenever the slightest sound rises.

Here in the middle is Capablanca, the Cuban wizard, whose fast under-hand move has revolutionized chess. Opposite him is Bogoljubow, the Ukrainian wizard, whose fast over-hand move has revolutionized chess. This between them is the star spectacle.

Bogoljubow is not a spectacular player. But he is known among chessplayers as the heady man, cool in the pinches and possessed of a wicked shift. He was drafted by the National League of Ukrainia after he had subdued the fast semi-pro Ukrainian All-Star Ukulele Players Chess Team during its spring training trip last year, setting them down, one, two, three. He made good from the start in big company and was soon bought by the Ukrainian Ugenots, the fastest chess combination in south-west Europe – or is it Asia?

They tell a very funny story about Bogoljubow when he came up to the Ugenots, a green Ukrainian country boy. He lost his first game through an odd and, as some say, dirty trick. In the beginning he lost the toss for goal and was forced to defend the Ukrainian east goal, known all over Europe as one of the sunniest fields in the world. And in addition to playing throughout the game with the fierce Ukrainian sun shining in his eyes, he erroneously played the game with his opponent’s men, the judges having deliberately failed to tell him which were his and which his opponent’s.

That Bogoljubow – or, as his friends familiarly call him, Bogoljubow – should now be in this contest and facing the great Capablanca is evidence of his sturdy constitution, unbreakable spirit and well-muscled back and shoulders. He was the kind of boy that was Bound to Make Good.

Moves do not occur to him as quickly as they do to Capablanca. The Cuban wizard sits down, thinks concisely for no more than half an hour, and presto! the trick is done. It is dazzling, his speed, and again and again yesterday the crowd was brought to its feet in outbursts of spontaneous sighing, which is the only form of cheering permitted.

Capablanca is the flashy player, the kind of man that has the crowd with him always, while good old Bogoljubow thinks and thinks and thinks. Time passes. More time passes. But Bogoljubow is thinking. He holds his head in his hands. He eyes them all, queens and those other little doodads on the board, individually and collectively. He writhes. He bites his nails. He twists in mental torment.

And Capablanca, the speed demon of the Hesperides, or thereabouts, paces nonchalantly up and down the runway, exercising, keeping his muscles fit, testing his chess expansion. He deigns only now and then to glance at his tortured opponent.

But Bogoljubow is thinking. The old Ukrainian noodle is hard at it. It was not for nothing that he was known in Ukrainia as the fiercest hand-to-hand thinker in European chess. His arm may give out some day, but still the old bean will be there, working steadily and efficiently.

And at last, as chance would have it, the solution came to him. He moved a gadget. With a smothered curse Capablanca sits down again suddenly, pauses a few hours, and then quickly, surely, promptly, he moves another gadget. It is all over so quickly that one scarcely has time to say Jack Robinson 12,000 times.

On and on it goes like that, from 2.30 [sic] to 6 p.m. each afternoon and again at night, beginning at 8 o’clock.

Down the line are other celebrities – Ed Lasker, from Chicago, using the famous Chicago sidewind before moving; Janowsky, from France, a cunning player with a deceptive straight-arm movement; old Dr Lasker of Germany, the veteran of 10,000 battles; the fierce Dr Tartakower from Austria, brooding madly over everything; the handsome Mr Alekhine of Russia, with a wing collar; Yates of England –

And among the spectators yesterday afternoon was “Ivory Luther” Hooks, the international indoor craps champion, which he won on the fields of Eton last year when he played under the colors of the Brooklyn Mah Jong and Clam Bake Association.

“I hope you do not ask me what I think of this game”, Mr Hooks said to a reporter, “but if you do I shall not tell you.”

This was all that could be got from him.’

(6881)

Wanted: the newspaper article referred to by Edward Lasker on page 159 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood (Philadelphia, 1942):

‘As Horace Bigelow, who covered the tournament for one of the New York papers, remarked at the time: “The modern school came, saw and succumbed.”’

From page 92 of Lasker’s The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘... the amusing though erroneous comment of a chess columnist was: “The New School came, saw, and succumbed.”’

(8196)

An invitation to heresy: are there any famous games that readers considered grossly over-rated? Personally – and it is hard to get more heretical than this – we have never been much taken with the Réti-Bogoljubow brilliancy-prize game at New York, 1924.

(614)

From a letter contributed by Leonard B. Meyer to Chess Review, June 1949, page 161, regarding the conclusion of the New York, 1924 tournament:

‘… local chess-players were divided into Capablanca, Marshall and Réti camps, and I was in the center as a member of the brilliancy prize committee. I was strongly in favor of giving the first prize to Réti for his game against Bogoljubow. The other judges were Hermann Helms and Norbert Lederer, and it was common knowledge that originally the committeemen did not see eye to eye. However, on the night before the dinner at which the awards were to be made, the committee finally unanimously selected this game for first prize.

The next day a bomb burst. There had been a leak, and Herbert R. Limburg, president of the congress, was in a dither. He had received a letter from John Barry, objecting to the committee’s decision. The letter also included a vitriolic attack against me. It began about as follows: “It has come to my knowledge that one Meyer, who is either a knave or a moron, has decided to give the brilliancy prize to Réti”. The balance of the letter, besides discussing patriotism, included a system for deciding prizes, with points for various types of sacrifices, all of which added up to first prize for Marshall for his game with Bogoljubow.

At a hastily called meeting of the tournament committee, the decision of the brilliancy prize committee was upheld. To further sustain the verdict, I quote the following from Dr Alekhine’s annotations to the Réti-Bogoljubow game in the tournament book: “Rightfully, this game was awarded the first brilliancy prize”.

In 1930, I met Dr Tartakower in Paris. He told me that, in his opinion, when all other details of the tournament are forgotten, the Réti-Bogoljubow game will be remembered as one of the six greatest games ever played.

… It is like judging any other work of art: the experts are bound to disagree.

Just for the record, in later years, Barry apologized, and we buried the hatchet.’

(2538)

Luca D’Ambrosio asks when the term ‘Meran Variation’ (or ‘Meran Defence’) first appeared in chess literature. He cites a note to the game Bogoljubow v Maróczy (after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 e6 5 Nbd2) on page 318 of the German edition of Alekhine’s New York, 1924 tournament book:

‘Offenbar um die Meraner Variante (5 Sb1-c3 Sb8-d7 6 Lf1-d3 d5-c4:! usw.) zu vermeiden.’

The note appears on page 232 of the English edition.

We add that Das Grossmeister-Turnier New York 1924 was published in or around February 1925. It was reviewed on page 69 of the March 1925 Deutsche Schachzeitung and on pages 42-43 of the March 1925 American Chess Bulletin. The latter source also stated that publication of the English-language edition was imminent:

‘After many unforeseen and more or less vexatious delays, of which translation from the German was by no means the least, the home edition of the New York Tournament Book has at last reached the bindery ...’

The Meran tournament in question took place in February 1924, and our correspondent is therefore seeking occurrences of a term such as ‘Meran Variation’ between that time and the appearance of the New York tournament book approximately one year later.

(5414)

See The Meran Variation of the Queen’s Gambit.

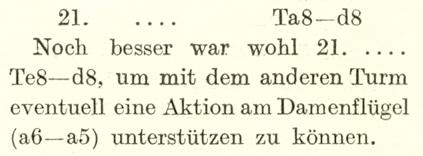

This position occurred after 21 Rfe1 in Tartakower v Réti, New York, 1924. Black played a rook to d8, but which rook?

The question has been put to us by Charles Sullivan (Davis, CA, USA), who comments that although various sources, including databases, give the next move as 21...Rad8, The Book of the New York International Chess Tournament 1924 by A. Alekhine (New York and London, 1925) put ‘KR-Q’ on page 191 and appended this note on the next page:

‘The queen’s rook stays at its own square in order eventually to make a demonstration on the queen’s side (P-QR4).’

We note, though, that page 267 of the German edition of

Alekhine’s tournament book (Berlin and Leipzig, 1925) stated that

the move played was 21...Rad8. Alekhine wrote that moving the

king’s rook to d8 would have been an improvement:

Tartakower annotated the game, which he lost, on pages 220-222 of the August 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung. 21...Rad8 was the move given, with an exclamation mark. It may therefore be strongly suspected that 21...Red8 in the English edition of the New York, 1924 book was wrong, possibly owing to a misunderstanding and/or translation error, but the matter has yet to be put beyond doubt.

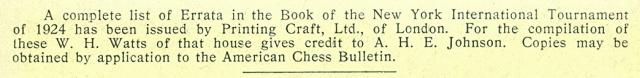

Notwithstanding the quality of Alekhine’s annotations, the book was a lax production. C.N. 2131 (see page 283 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) mentioned that W.H. Watts added a nine-page errata supplement (to the British edition, of which he was the publisher). The list sheds no light on the ‘Which rook?’ puzzle but is, of course, indispensable in connection with any English-language edition of Alekhine’s book.

(5954)

Position after 21 Rfe1

Concerning Tartakower v Réti, New York, 1924, David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) informs us that he owns Réti’s score-sheet, which clearly indicates that 21...Rad8 was played. Since that was also the move given by Tartakower (as shown in C.N. 5954), it seems evident that the English-language edition of the tournament book by Alekhine was wrong.

(6009)

American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1925, page 123.

Most of the corrections in the nine-page list, referred to in C.N. 5954, concern notation, but below are some examples of substantive matters:

(5955)

Noting that the ‘21st Century Edition’ of Alekhine’s New York, 1924 tournament book (Milford, 2008) does not identify the translator or the language in which Alekhine wrote, Michel Therrien (Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada) remarks that it is not unusual for such information to be omitted when old chess books are reissued.

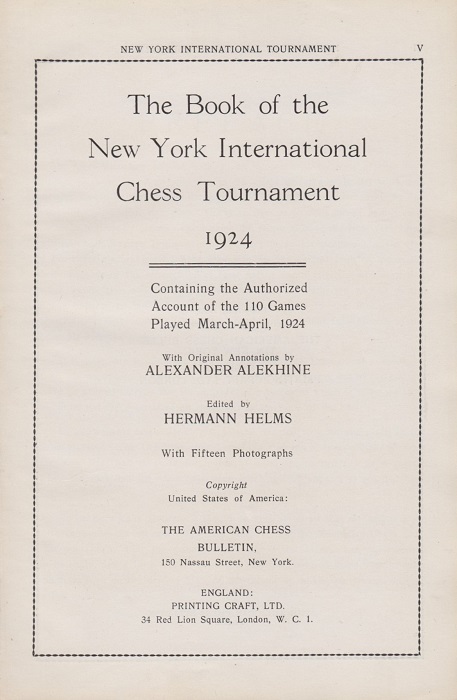

In the particular case of The Book of the New York International Chess Tournament 1924 (New York and London, 1925), however, we point out that no translator or language was specified in the original edition, although H. Ransom Bigelow was credited with translating Alekhine’s article ‘The Significance of the New York Tournament in the Light of the Theory of the Openings’ (pages 247-267). Readers were thus left to assume that all the annotations were translated by the book’s editor, Hermann Helms, who was mentioned on the title page:

In the ‘21st Century Edition’ Helms was named as editor on the imprint page, whereas the writer of the two-page Foreword, A. Soltis, was mentioned on the front cover, the title page and the imprint page.

C.N. 5414 reported that Das Grossmeister-Turnier New York 1924 was published in or around February 1925 and that a review on pages 42-43 of the March 1925 American Chess Bulletin stated:

‘After many unforeseen and more or less vexatious delays, of which translation from the German was by no means the least, the home edition of the New York Tournament Book has at last reached the bindery ...’

(9257)

C.N. 11021 noted that the Dover reprint of the New York, 1924 tournament book included a few post-1924 photographs.

(12161)

See also Chess in 1924.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.