Edward Winter

(2002, with updates)

Carl Schlechter

Alessandro Nizzola (Mantova, Italy) points out this translator’s note about Schlechter on page 119 of Nimzowitsch’s La Pratica del Mio Sistema (Milan, 1987):

‘For the record: the Austrian master starved to death in his home city of Vienna on Christmas Day 1917.’

For the record: wrong city, wrong country, wrong day, wrong year.

(2396)

Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) draws attention to a passage on page 5 of a book published by Kalnājs on the Chicago, 1973 tournament:

‘Carlos Torre, a young unknown chessplayer from distant exotic Mexico, was the greatest threat to the leading grandmasters in Moscow’s international tournament of 1925. Here is one example of his play. Because of Moscow’s freezing winter climate, after a short time illness felled Carlos Torre prematurely at the age of 29.’

Since Torre died in 1978 ... it is the Kalnājs book that felled him prematurely.

(2411)

A surprising number of publications have misguidedly shovelled into the grave various chess figures who were, to a greater or lesser degree, still alive. Below are some examples.

Franz Tendering, a dynamic player, died on 18 August 1875 at the age of 27. The report on page 284 of the September 1875 Deutsche Schachzeitung mentioned that his demise ran counter to the popular belief that anyone whose death was wrongly announced would enjoy a long life; Tendering had been fallaciously declared dead in the March 1872 Deutsche Schachzeitung, pages 79-80, with a retraction published on page 128 of the April 1872 issue. Three games won by him were given on pages 120-121 of A Chess Omnibus. (See too Chess Jottings.)

Page 185 of La Stratégie, June 1879 reported that a number of other Parisian publications had mistakenly announced the death of Morphy. On page 345 of its 15 November 1882 issue La Stratégie noted another report involving Morphy, and the consequence was a stinging attack on the press by Alphonse Delannoy on page 8 of La Stratégie, 15 January 1883. (See also page 370 of the December 1882 Deutsche Schachzeitung.)

Moreover, the Pioneer, Allahabad of 25 December 1882 contained a ‘remarkable statement’, i.e. an invention about Morphy being defeated in a match played in India on a board of gold and silver, with pieces composed of precious stones. The quoted report began, ‘Morphy, the celebrated American chess-player, recently deceased, is said to have detested the very name of India, for here he met his match’. This was reported on page 168 of the February 1883 Chess Monthly. Morphy died the following year.

Another American chess figure who was prematurely despatched to eternity was Gilberg. From page 139 of the April 1889 BCM:

‘We exceedingly regret to hear of the death – after a long and severe illness – of Mr Charles A. Gilberg, the president of the Brooklyn Club.’

However, page 328 of the August issue presented a consultation game involving Gilberg and played on 1 June 1889; ‘it serves to shew that the respected president of the club, Mr Gilberg, whose death has been erroneously announced, is still in the flesh.’

The Chess Monthly (July 1889, page 328) also reported Gilberg’s alleged death:

‘Those who share an interest in American chess will learn, with no little regret, the loss of one of the greatest problem masters of the Western World. Mr Charles A. Gilberg no longer lives to adorn the problem literature of his country, for which in the past he has with his wealth of genius and enthusiasm rendered so much service. In our May issue we quoted, by way of memoriam, two of his successful problems.’

Writing from New York on 3 August 1889, Gilberg set matters straight (see page 6 of the September 1889 Monthly):

‘I am extremely sorry to spoil the pretty little complimentary notice bestowed upon me in the Chess Monthly for July. Although practically defunct to the chess world for some years past, and recently prostrated by a severe and critical illness which confined me to my room for nearly six months, I have not yet “shuffled off this mortal coil”…’

He did not shuffle it off until 1898.

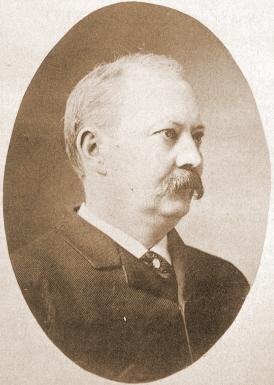

Charles Alexander Gilberg

The BCM (April 1895, page 179) reported the death of Heinrich Schlemm, but its June issue (page 266) printed a rather flummoxed correction: ‘We took the information from one of our German or Austrian exchanges, but cannot now remember which.’ When Schlemm did in fact die, in 1901, the BCM published no obituary.

Similar trouble occurred after the following paragraph appeared on page 2 of the January 1897 BCM:

‘We are extremely sorry to hear that the renowned problemist Mr Mackenzie, of Jamaica, is dead. We hope that the report may be incorrect, but bearing in mind that he has for some time been in a failing condition, and has lost his eyesight, we should not be surprised to find that it was unfortunately true.’

It was fortunately untrue, as the BCM reported on page 43 of the February 1897 number. Mackenzie died in 1905, aged 43.

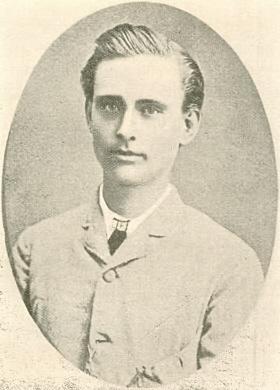

Arthur Ford Mackenzie

Page 89 of the March 1919 American Chess Bulletin included a reference to ‘P. Richardson being the famous veteran problem composer of the USA, who died a few years ago’. On page 165 of the May-June 1919 issue Richardson’s reaction, dated 12 March, was printed:

‘I wish to correct the report of my death. I am still considerably alive, but do not play much chess, on account of my eyesight.’

Richardson died the following year.

The ‘complete disappearance and feared death’ of Alekhine was mentioned on page 183 of the June 1920 BCM. Under the heading ‘A Sinister Report’, page 286 of the July 1920 Chess Amateur quoted an item from the Falkirk Herald which hinted that tragedy had befallen Alekhine but gave no specifics. In The Field, 23 October 1920 Burn referred to the conflicting reports regarding Alekhine: ‘One, which we had from one of the Dutch competitors at the Edinburgh Chess Congress, was that he had been executed in Odessa; another, received later, that he was alive and well in Moscow.’ The BCM re-expressed its concern about the master’s fate on page 368 of the November 1920 issue, but the February 1921 number (page 57) reported, courtesy of Deutsche Schachzeitung, that Alekhine was ‘alive and doing well’. Alekhine’s supposed death was also mentioned in a book, i.e. on page 22 of Cours d’échecs by Alphonse Goetz (Paris, 1921):

‘Unfortunately this brilliant young master, born of the Russian bourgeoisie, seems to have perished in one of the innumerable massacres organized by the Soviets.’

In 1921 various periodicals reported, and retracted, news of the death of Leo Forgács. See, for example, the Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1921, pages 46-47 and March 1921, page 72 (where the old popular belief was reiterated) and the BCM, March 1921, page 87 and April 1921, page 132. He lived on until 1930.

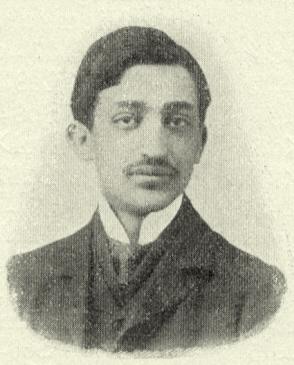

Leo Forgács

Another case was the reported death in 1924 of G. Lazard, who in

fact died in 1948; see our Chess in 1924

feature article.

The death of Alexander Takács was reported on page 502 of the November 1931 BCM. The misinformation was corrected in the December issue (page 530), the magazine having been notified by A.G. Olland that ‘the Takács who died was not the chess master but the celebrated lawn tennis player’. (This was Emmerich Takács. The chess-player, Alexander, died the following year.)

Page 29 of the January 1934 Wiener Schachzeitung stated that Abraham Speijer had died on 19 November 1933. The following issue (February 1934, page 44) announced that that date had merely been Speijer’s 60th birthday. That occasion had been the subject of an extensive article (headed ‘19 November 1873 19 November 1933’ – celebratory not valedictory) on pages 291-293 of the November 1933 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond. Speijer lived on until 1956.

Page 59 of the February 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung refuted claims that Ramón Rey Ardid had died in the Spanish Civil War. He was still alive over 50 years later.

From page 600 of the December 1937 BCM:

‘We are happy to be able to state that the reports which have appeared of a fatal ending to the mishap to Jacques Mieses at Kemeri last summer (see BCM, Sept., p. 474) are incorrect.’

The earlier BCM report had recorded: ‘In attempting to get on an omnibus he slipped, and one of the wheels passed over his leg. We hope for news of a good recovery.’ See also page 316 of the October 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung. CHESS, April 1945 (page 107) reported on a speech by Mieses at a celebration of his 80th birthday:

‘He said he was one of the few men who had read his own obituary notice. In this he was astonished at the wonderful man he had been, and the good things that could be said of one.’

From T.R. Dawson’s Endings column on page 168 of the July 1945 BCM:

‘For the second time in my life, I have to announce the news of the death of Alexis A. Troitzky, the incomparable Russian endings genius. In 1919, he was reported dead, but in 1920 in a letter from his own hand I had the joy of turning “dead” into “missing and found again”. This time, alas, there can be no such outcome.’

Since Troitzky died in 1942, the two announcements of his death were precipitate and belated respectively.

Page 6 of the 1 January 1948 Chess World referred to a claim that ‘some years ago we published an obituary notice of Miss Price, manageress of the Gambit Chess Rooms. We’ll believe it when we see it . If we ever did publish a report of Miss Price’s death it was evidently grossly exaggerated. At any rate, she laughed heartily when told about it.’

Edith Charlotte Price

Coming closer to today, on page 441 of The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal (New York, 1976), Tal said that in 1969 a number of Yugoslav newspapers had reported his death. See also page 393 of the London, 1997 edition.

But we have saved for the end what must surely be the world record in this domain: on page 218 of the October 1922 Deutsche Schachzeitung, J. Berger reported, courtesy of Rinck, the deaths of four endgame composers, A. Troitzky, M. Platov, V. Platov and L. Salkind. All four reports were untrue.

(2543)

The misinformation was even restated on page 332 of L. Bachmann’s Schachjahrbuch 1922 (Ansbach, 1924):

‘Die bekannten russischen Komponisten Troitzky, Salkind und W. und M. Platoff sind während der bolschewistischen Wirren in der Krim ums Leben gekommen.’

(8662)

Regarding A.F. Mackenzie, see also C.N. 11736.

Addition on 15 November 2010, courtesy of Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy):

From The Field, 19 June 1875:

‘Death of Capt. Kennedy

We announce with regret the death, at the age of 68, of Capt. H.A. Kennedy, whose name has been associated with the chess world for the last 40 years – an enthusiastic amateur, acknowledged the best chessplayer in the army, and one of the strongest of English players. In 1845 he played a great deal with Mr Buckle, the author of the History of Civilisation, with whom he then made even games, a creditable performance, if we remember that some years after Mr Buckle was pronounced by Anderssen to be the finest English player. In 1848 he beat Mr Lowe in a match for the four games, by four to three, but soon afterwards lost the return match for the first seven games, also by the odd game; so that the two players came out exactly even. In 1851 he participated in the Grand International Tournament, where in the first round he threw out Mayet, one of the seven stars of Berlin. For the second round he was beaten by the ultimate winner of the second prize, Mr Marmaduke Wyvill, MP for Richmond; in the third round he beat Mr Mucklow; in the fourth round he lost against the Hungarian Szen; and finally was awarded the sixth prize. In 1862 he published a book under the title Waifs and Strays, chiefly from the Chessboard (published by L. Booth), which contained a collection of humorous chess anecdotes. Most of the latter had already appeared in the Chess Player’s Chronicle and the American Chess Monthly, and some of them had previously been found worthy of a place in the pages of Punch. Up to a short time before his death, he took the warmest interest in the game which he had liberally supported throughout his life. His personal qualities were characterized by an amiable disposition, and his loss will be deeply felt in the widest chess circles.’

The retraction, in The Field, 26 June 1875:

‘Captain Kennedy

As appears from the subjoined letter, the report of Capt. Kennedy’s death, published in our last week’s issue, is erroneous. The happily unfounded news was communicated to us independently by two of the strongest metropolitan players, whose bona fides are [sic] above suspicion, and who had received the tidings from a member of a West-end club to which Capt. Kennedy belongs. We have not been able to trace the origin of the false report, but we can assure our esteemed correspondent that, for the first time within our editorial experience, we feel great pleasure in correcting a mistake that has appeared in our columns.

“Sir: I have had the mournful satisfaction of reading my obituary notice in The Field of Saturday last. It is not everyone who is so privileged, and I am much obliged for the friendly and flattering remarks with which you garland my tomb. But I am not dead yet: moreover, if I am to attain the age of 68, I have still some time to spend in this best of all possible worlds. Some wag has been imposing a figment upon you. Let your editorial baton amite him heavily.Yours in the flesh,

H.A. Kennedy.

Junior United Service Club, 22 June.”’

Mr Zavatarelli adds that the ‘true’ obituary of Kennedy was published in The Field of 2 November 1878:

‘Death of Capt. Kennedy

We are sorry to announce with regret the death of Capt. H.A. Kennedy, at the age of 69, which occurred on the 22nd ult., at Ailsa House, Reading. The deceased gentlemen occupied a high place amongst English chessplayers of the old school, and his name has been associated with English chess history for more than 40 years as an enthusiastic amateur, and the acknowledged best player in the army. In 1845 he made even games with Mr Buckle, the author of the History of Civilisation, whom, some years afterwards, Anderssen pronounced to be the finest English player. He also came out even in two matches against Mr Lowe in 1848. In 1851, Capt. Kennedy took part in the Grand International London Tournament, and was awarded the sixth prize, with a creditable final score; for in the first round he threw out Herr Mayet, one of the seven stars of Berlin, by winning two games; in the second round he was beaten by the ultimate winner of the second prize, Mr Marmaduke Wyvill, by 4 to 3, and one draw; in the third round he beat Mr Mucklow four games right off; and in the fourth round he was defeated by the great Hungarian player, Herr Szen, by four games and one draw. As a chess author, Capt. Kennedy contributed much to the rising popularity of our game by the collection of the humorous and satirical anecdotes and essays in relation to chess and chessplayers under the title Waifs and Strays, chiefly from the Chessboard (See our review published 12 February 1876). He was a well-known warm and liberal supporter of the game up to the last, and his loss will be much regretted by chessplayers all over the world.’

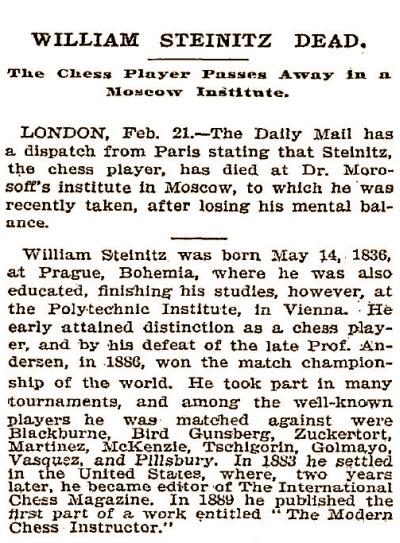

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) mentions this report in the New York Times of 22 February 1897:

We recall that Tarrasch mentioned the premature news reports about Steinitz in the essay ‘Der Fall Pillsbury’ in his book Die Moderne Schachpartie (page numbers vary according to the edition):

In fact, there was no ‘obituary’ of Steinitz in the Deutsche Schachzeitung of 1897, a magazine then edited by Tarrasch. See, however, the extensive selection of Steinitz’s best games on pages 70-85 of the March 1897 issue. The feature began with a note stating that reports of the former world champion’s death were untrue.

(6901)

C.N. 9830 showed material written by Gunsberg in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1897 concerning Steinitz’s supposed death.

An addition is offered by Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) from Mendel Marmorosh’s chess column on page 4 of Davar, 27 May 1938:

Our correspondent provides this translation:

‘Sammy Greenberg the Chessplayer – Alive!

We were unfortunately misled, and wrote an obituary last week in our column about Sammy Greenberg the chessplayer, a member of the “Nir Hayim” [agricultural commune – A.P.] in Kiryat Biyalik. We confused him with Sammy Greenberg from Ein Gev, who was killed in an accident. S. Greenberg the chessplayer is alive and managed, as he writes to us, “to read his own obituary”. Long may he live.’

(8682)

Concerning William Henderson Winter, see our feature article about his son, William Winter.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.