Edward Winter

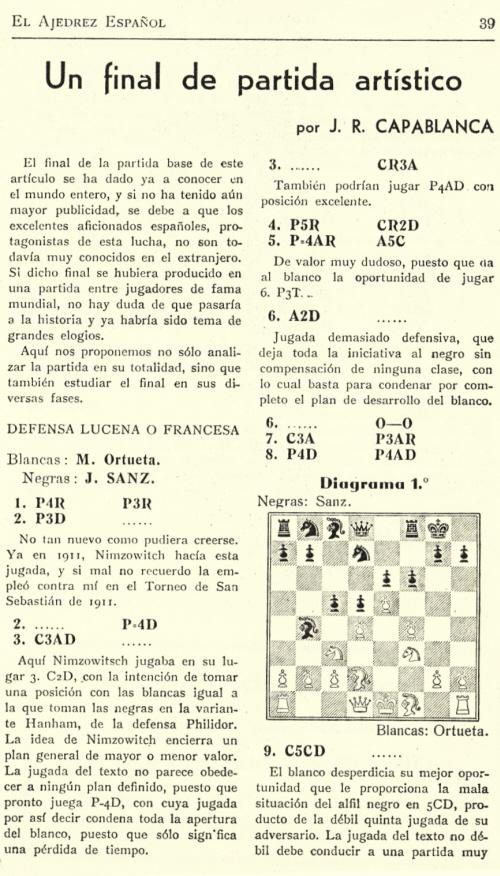

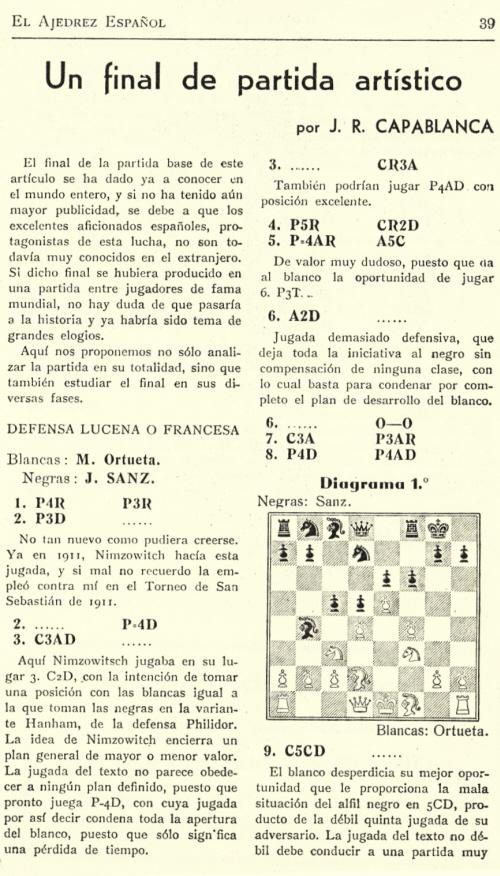

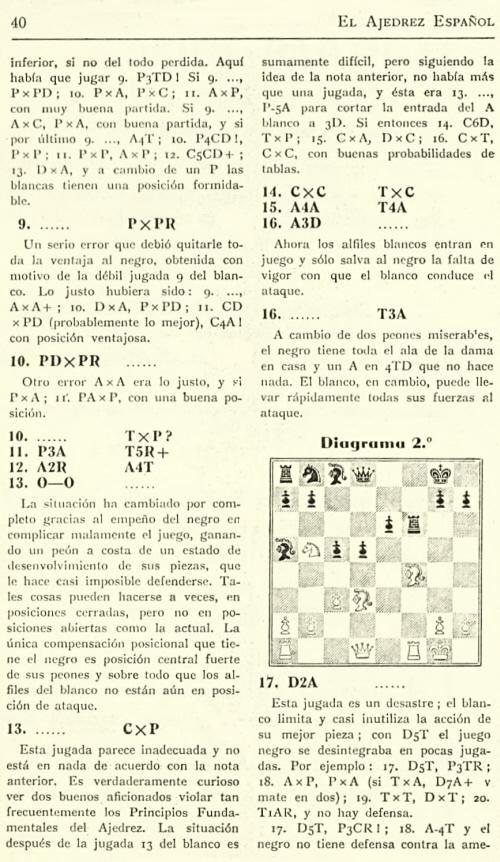

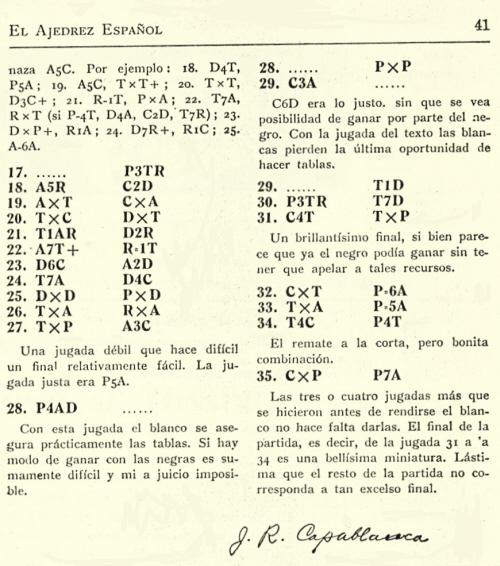

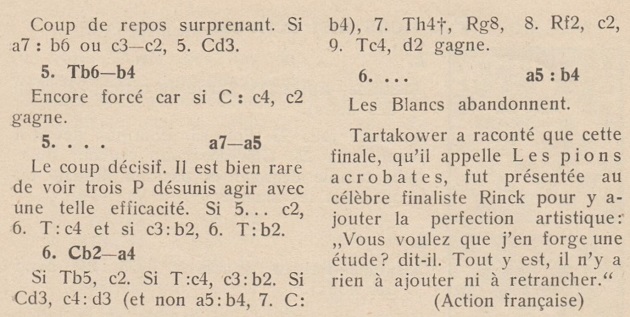

Capablanca’s annotations to this famous game, from pages 39-41 of El Ajedrez Español, February 1936:

For an English translation, see pages 258-259 of our book on Capablanca.

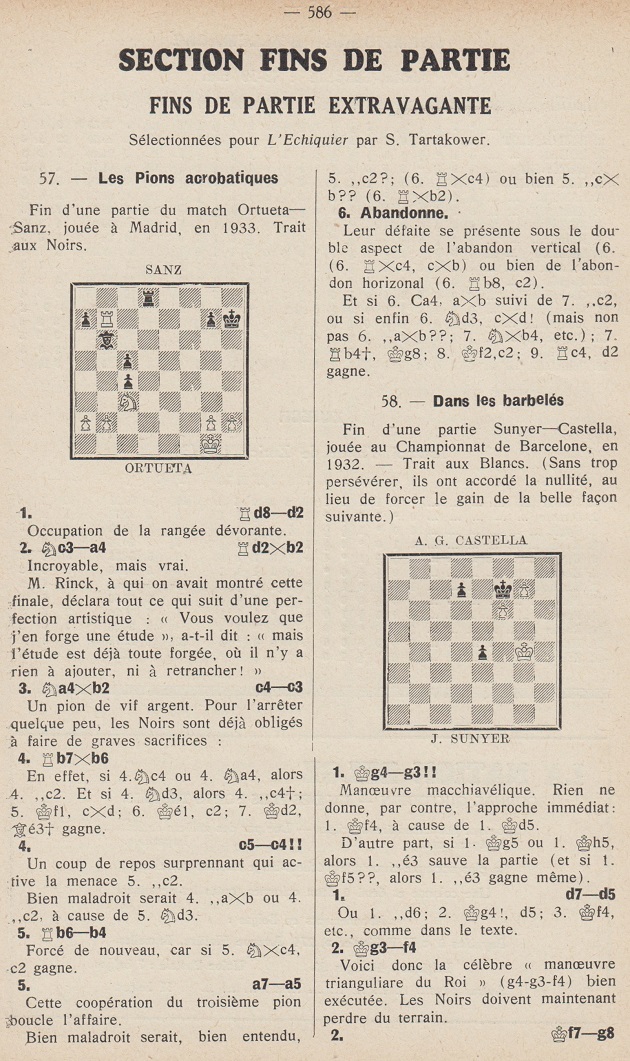

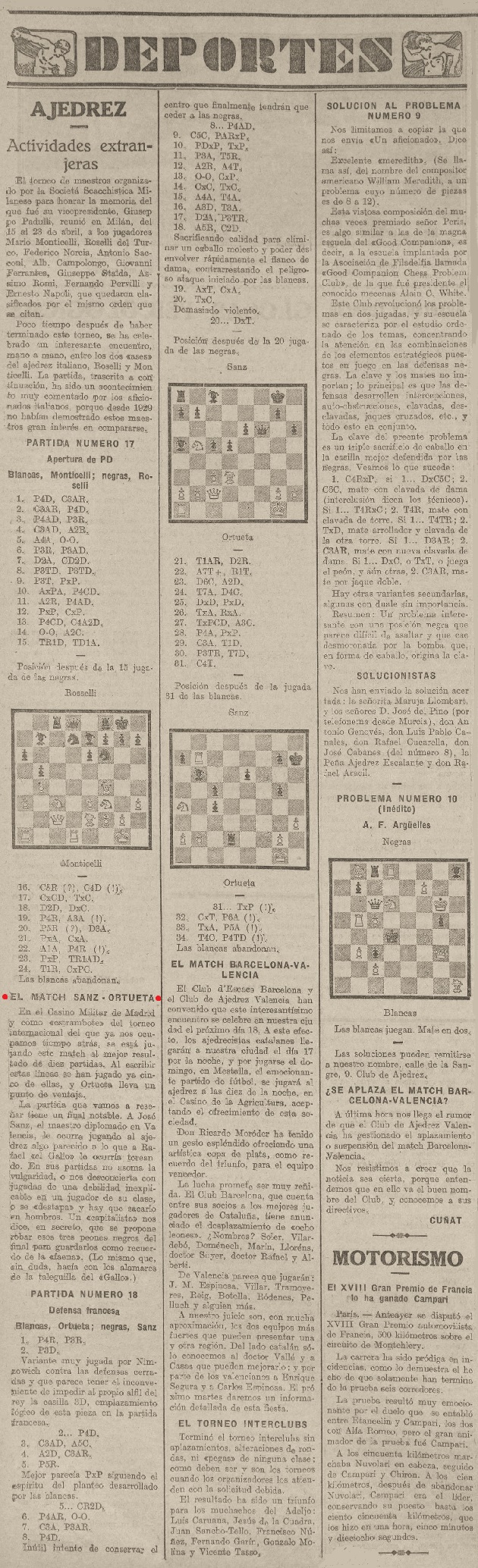

We wonder whether any details are available concerning Rinck’s reaction when shown the finish, according to Tartakower on page 586 of L’Echiquier, 8 August 1934:

‘M. Rinck, à qui on avait montré cette finale, déclara tout ce qui suit d’une perfection artistique. “Vous voulez que j’en forge une étude”, a-t-il dit: “mais l’étude est déjà toute forgée, où il n’y a rien à ajouter, ni à retrancher.”’

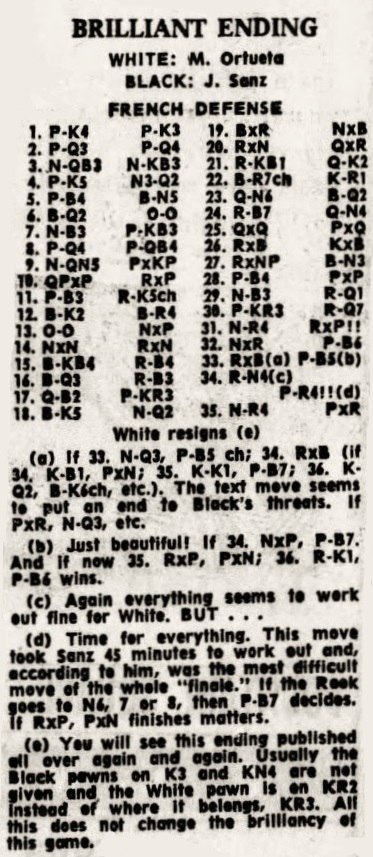

Another question concerns the grounds, if any, that Koltanowski had for stating on pages 96-97 of Chessnicdotes II (Coraopolis, 1981) regarding 34...a5:

‘This move took Sanz 45 minutes to work out and, according to him, was the most difficult of the whole “finale”.’

According to Bruce Hayden (in an article about the game in Chess Review, May 1964, pages 136, 137 and 159) the move on which Black consumed that amount of time was 31...Rxb2:

‘After 45 minutes’ thought, Sanz had produced a thunderbolt with a rook sacrifice heralding one of the most remarkable endgames in the history of chess.’

For detailed information about the game, see Strangest Coincidence Ever – or Hoax? by Tim Krabbé.

(8153)

In C.N. 2273 we commented:

https://timkr.home.xs4all.nl/chess/chess.htmlA most interesting site on the Internet is Tim Krabbé’s ‘Chess Curiosities’. Among his recent articles are an updated investigation of the Ortueta v Sanz mystery, an account of the Dutchman Chris de Ronde (who played ‘an enigmatic immortal game’ in the 1930s which was as shrouded in mystery as he himself), and an excellent listing of ‘chess records’, such as the longest game, the latest castling, and the greatest number of queens.

Krabbé is one of the best chess writers, and his site is not to be missed.

Pointing out an article by Joaquim Travesset about this game, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) comments:

‘The novelty is that the writer’s conclusion, that the Ortueta v Sanz game was a hoax, is based on his view of the character of one of the players.’

(8159)

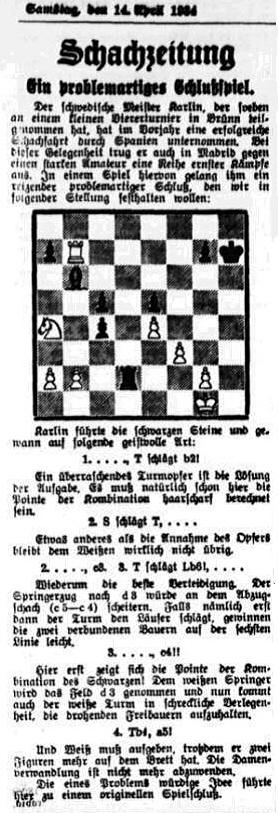

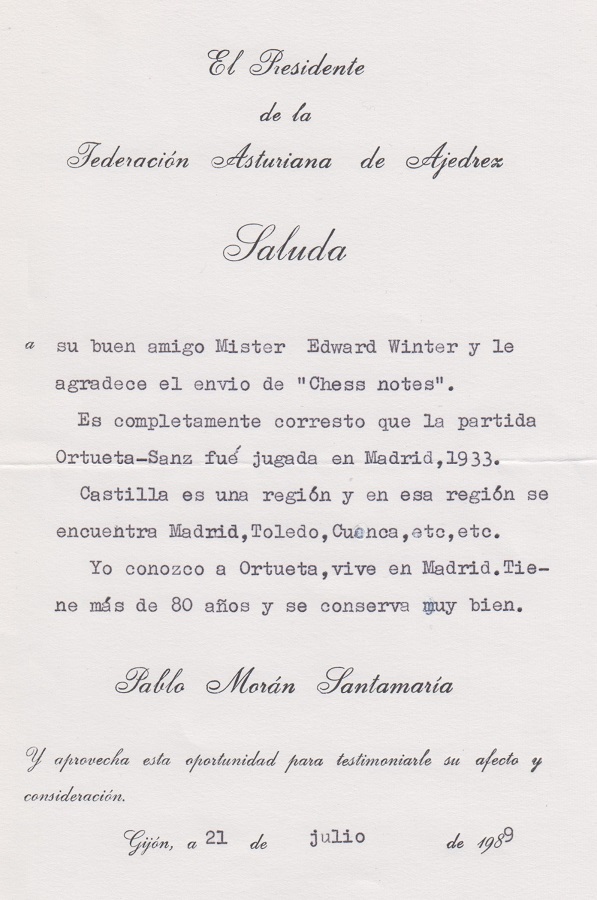

Regarding the famous, mysterious Ortueta v Sanz game, Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) has just found a chess column in the Tagesbote (Brno) of 14 April 1934 which throws a hefty spanner in the works by giving the conclusion of a game said to have been won in Madrid the previous year by the Swedish player Ored Karlin against an unnamed opponent:

(8830)

Zalmen Kornin (Curitiba, Brazil) draws attention to a report on page 46 of ABC, 24 May 1933, which announced a tournament in Madrid with the participation of, inter alios, Karlin, Sanz and Ortueta.

(8847)

The final phase of the Ortueta v Sanz game was published on page 69 of Instructive Positions from Master Chess by Jacques Mieses (London, 1938). His opening and concluding comments:

‘The finish is of extraordinary beauty.’

‘One would imagine this to be an artistic composition and would hardly credit it with being the conclusion of an actual game.’

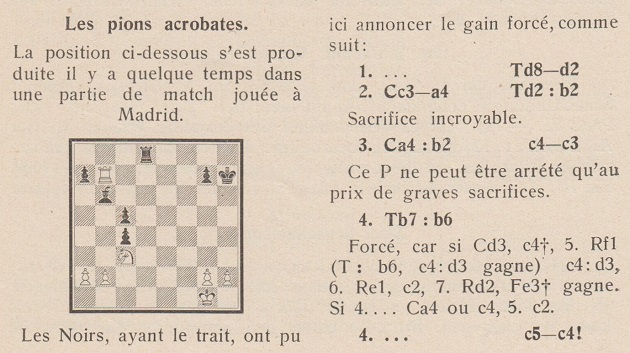

Page 586 of L’Echiquier, 8 August 1934:

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) writes:

‘Page 200 of the July 1933 Deutsche Schachzeitung gave the result of the tournament in Madrid in which the Ortueta v Sanz game may have been played:

If that was indeed the tournament, it is remarkable if the full game was not published earlier than 1936.

The 11 April 1934 edition of the Neues Wiener Journal, page 7, referred to involvement by the police after a report of Ored Karlin’s disappearance from a Budapest hotel:

The 13 January 1935 edition of the Estonian publication Esmaspäev, page 8, discussed the endgame:

As with the Tagesbote article (C.N. 8830), it appears that Karlin suggested that the position was from one of his own games. Soon afterwards, however, the writer noticed the feature on page 356 of the December 1934 Wiener Schachzeitung which credited it to the Ortueta-Sanz game.

The position in the Tagesbote column of 14 April 1934 shows white pawns on a2, b2, g2, f3 and e4 (no pawn on h2). L’Echiquier, 8 August 1934, page 586, the Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 August 1934, page 249, and the Wiener Schachzeitung, December 1934, page 356, had white pawns at a2, b2, g2 and h2, as did the above column in Esmaspäev.

The story about Karlin disappearing from the Budapest hotel and the two newspaper reports suggesting that he claimed the endgame as his own seem to raise doubts about his character. However, that has to be set against comments made by Anders Wigren to Tim Krabbé in item 396 in the latter’s Open Chess Diary.’

(10780)

From Christian Sánchez:

‘The international tournament in Madrid in 1933 was played from 22 to 28 May in the Casino Militar (Centro Cultural del Ejército y de la Armada). The participants were Ored Karlin (Sweden), Willy Kocher (Switzerland) and the Spanish players Vicente Almirall (the winner), Lotario Añón, Alfonso Cadenas, Martín de Ortueta, José Sanz and Ramón Tramoyeres. Sources: the Madrid newspapers Luz, 24 May 1933, page 14, El Sol, 24 May 1933, page 8, and subsequent issues. The main prizes were: 500 pesetas, 300 pesetas and 200 pesetas. The event was covered by the local press and particularly Luz and El Sol. The Luz chess columnist was José Sanz himself, and the reporter in El Sol was Pedro Sánchez de Neyra y Castro, Marquis of Casa Alta, who was the arbiter of the tournament.

No incident occurred until the last round. Sanz simply wrote about his game: “Sanz ½ Karlin ½. Interesting theoretical variation in the Cambridge Springs. White needs a win to take second place, but all the variations lead to a draw.” Source: Luz, 30 May 1933, page 14. However, on page 8 of El Sol, 1 June 1933 Casa Alta inserted a position (shown below) from that Sanz-Karlin encounter, and wrote that Karlin would have a won game after ...h3 but played differently and only drew. Insinuating some kind of collusion, Casa Alta reported that the next day he even confronted Karlin and asked for an explanation. Karlin replied that he “had a headache”.

Sanz answered the accusation (that “the Swedish master gave away the draw”) in his column by noting that Karlin had previously offered a draw twice and that he had refused. The feud continued over the following weeks.

Meanwhile, two matches with a purse were arranged, also at the Centro Cultural del Ejército y de la Armada: Karlin v Almirall and Ortueta v Sanz. In El Sol of 4 June 1933, page 10 Casa Alta replied to Sanz’s response and gave the latest scores in the two matches. For Karlin v Almirall he stated that the first game was won by Karlin and the second was drawn; the third game was being played on 3 June. The score of the Ortueta v Sanz match was reported as a victory by Ortueta in the first game, followed by two draws. The former contest ended in a tie 2½-2½, as stated by ABC on 7 June 1933, El Sol on 8 June 1933, and Luz on 9 June 1933. The dates of play were probably 1-5 June.

In El Sol, 11 June 1933, page 10 Casa Alta presented the Ortueta-Sanz ending without any moves (adding that this win by Sanz was followed by a victory by Ortueta, the last game of the match so far), and he also continued his argument with Sanz:

Karlin left Madrid on 10 June for Saragossa, where, on 11 June, he played Ramón Rey Ardid. Sources: El Sol, 13 June 1933, page 6, and El Mundo Deportivo, 18 June 1933, page 3.

In El Sol, 18 June 1933, page 10 Casa Alta reported that the Ortueta-Sanz match had been suspended when the score was 2½-1½ and gave a game in which Ortueta (Black) won in 36 moves. There is a discrepancy in the match score as given in Casa Alta’s columns.

Sanz presented the finish to his famous game, starting some moves before the combination and showing a knight on b6 instead of a bishop, in Luz, 26 June 1933, page 14:

Conclusions:

The famous combination occurred in an actual game between Ortueta and Sanz. It was the penultimate game in a public match, played in the first week of June 1933 at a renowned club in Madrid.

On 11 June 1933 Casa Alta published a key position preceding the combination, either because he was a witness or because he had a reliable source. Although the issue of the combination’s authenticity arose later, Casa Alta did not question it, notwithstanding the fact that he was in the midst of a feud with the winner, Sanz.

- Karlin was playing (a match against Almirall) at the same place and at the same time.’

(10782)

Two comments quoted above:

On 31...Rxb2:

‘After 45 minutes’ thought, Sanz had produced a thunderbolt with a rook sacrifice heralding one of the most remarkable endgames in the history of chess.’

Bruce Hayden, Chess Review, May 1964, page 136. (On the next page he also mentioned the consumption of 45 minutes for that move.)

On 34...a5:

‘This move took Sanz 45 minutes to work out and, according to him, was the most difficult of the whole “finale”.’

George Koltanowski, Chessnicdotes II (Coraopolis, 1981), page 97.

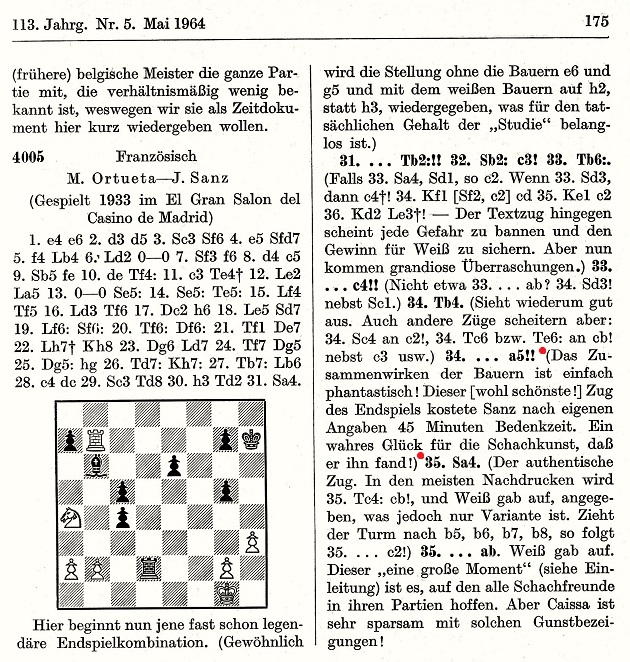

Alan McGowan points out that there was also a reference to 45 minutes on page 175 of the May 1964 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

In the mid-1930s the game became one of the most famous ever played in Spain, and in 1964 it suddenly enjoyed a renacimiento de interés. We note that Koltanowski’s above-mentioned coverage of the game in Chessnicdotes II is similar to what had appeared in his syndicated column on, for instance, page 47 of the Indianapolis News, 2 January 1964:

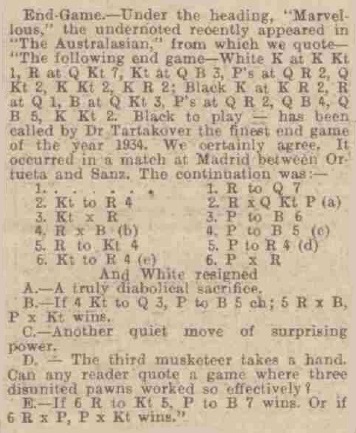

Alan McGowan draws attention to an item on page 14 of the Falkirk Herald, 26 June 1935:

Although that cutting states that Tartakower considered the endgame the finest of 1934, our feature article shows that he correctly dated it 1933 on page 586 of L’Echiquier, 8 August 1934.

As another example of how the brilliancy was disseminated in the 1930s, below is a text, attributed to Action française, on pages 31-32 of the February 1936 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

(11233)

Christian Sánchez writes:

‘Page 4 of La Correspondencia de Valencia, 15 June 1933 has the first appearance found so far of the full Ortueta-Sanz game-score. It came four days after Casa Alta showed the key position, and it even predates Sanz blowing his own trumpet.’

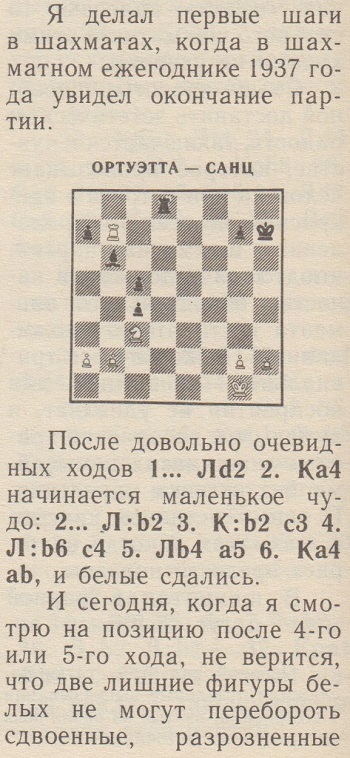

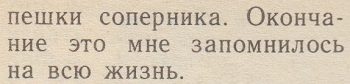

The Ortueta v Sanz ending was highly appreciated by Tigran Petrosian. From pages 136-137 of the posthumous anthology of his writings Шахматные лекции (Moscow, 1989):

Below is the translation on page 94 of the English edition, Petrosian’s Legacy (Los Angeles, 1990):

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.