Edward Winter

A quotation from Botvinnik in the context of Euwe’s death in 1981:

‘The world champions die in the strict order of their succession to the title. Thus the writer of these lines is the next on the list. I telephoned Smyslov and reminded him that after me it would be his turn. Smyslov laughed; indeed, as long as I am alive he can afford to laugh.’

Source: Europe Echecs, April 1983, page 13.

(551)

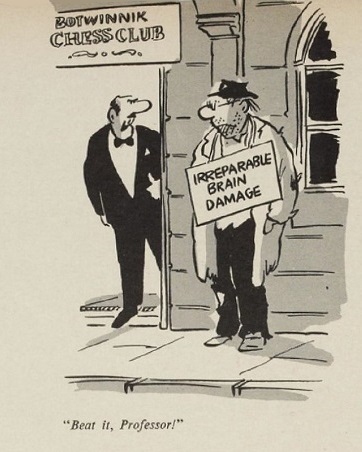

The Botvinnik quotation in C.N. 551 takes on a tragic twist with the premature death of the former world champion Petrosian. Lengthy obituaries have already appeared, and it would not be appropriate here to recall the life of this great player. Suffice it to say that the chess elite are best judged on two criteria: the quality of their best games and the amount of time they maintained world class. On this basis Petrosian was a dominant figure in twentieth-century chess, even if his complex style did not make him a favourite with magazine editors and columnists. Yes, Petrosian’s draw tally was excessive, but it is scarcely fair when commentators dwell on this aspect of his play and ignore his true achievements. Petrosian’s reputation will soar in years to come.

(820)

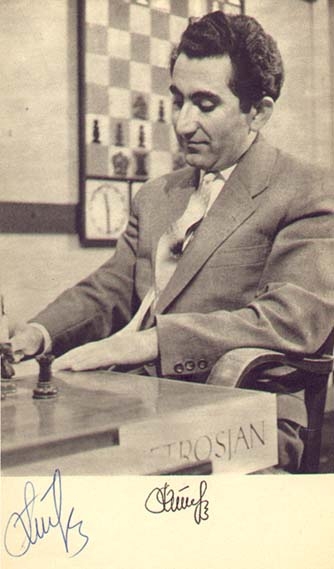

The Games of Tigran Petrosian, Volume I, 1942-1965, compiled by Eduard Shekhtman (Pergamon Press Ltd., Oxford, 1991)

Books featuring the ‘complete games’ of contemporary players seem to have gone out of fashion. In the decade up to 1980, Fischer’s output was well covered by several publishers; Tal had a series of three volumes from Batsford, though the project broke off at 1973; Korchnoi’s career was dealt with by the Oxford University Press; various comprehensive collections of Karpov’s games appeared. Since then, publishers have indulged in what may euphemistically be termed belt-tightening, to the extent that even the games of Kasparov, notwithstanding his popular style of play, have yet to be properly anthologized.

The appearance of The Games of Tigran Petrosian is thus a surprise. Its aim is to provide all the games played by the late world champion (1929-84), and this first volume, for which 1965 provides a rather unnatural break-off point, contains a more or less complete record of the early period. It begins with the sole informal game, a win against Flohr in a June 1942 simultaneous exhibition, and ends with two games against Korchnoi from the Moscow v Leningrad match of November 1965. The scale of the project is underlined by a comparison with the 1963 Wildhagen book on Petrosian, which went as far as the Curaçao Candidates’ tournament of May-June 1962. Wildhagen contained 350 games, while Shekhtman gives 938 for the same period. The overall total in Volume I of Shekhtman’s book is 1,089, and although the majority appear in bare-score form, many have notes. Indeed, almost every leading Soviet player is to be found among the annotators, and over 70 games have analysis by Petrosian himself. He wrote engagingly and instructively, concentrating on prose explanations rather than variations. Moreover, and this tends to be a useful indicator of a good book, the winner’s moves are sometimes criticized. Those 70 or so games would, alone, constitute quite a bookl

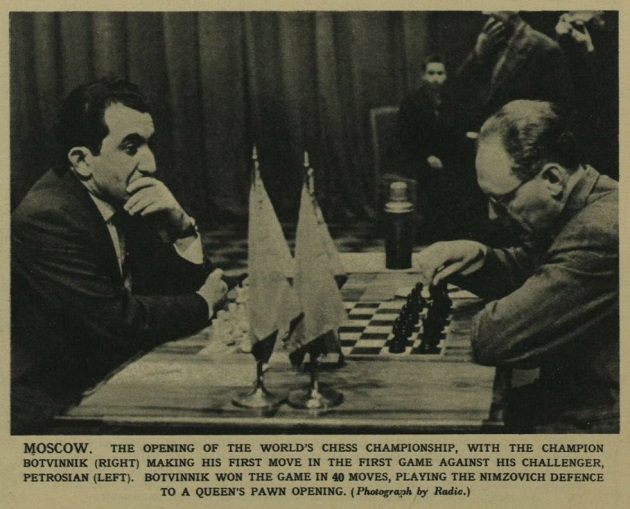

Many of Petrosian’s articles and interviews are woven into the collection, which is further brought to life by eight pages of photographs. His reminiscences repeatedly stress the influence of Nimzowitsch, whose Chess Praxis was the first serious chess book which he studied. For Petrosian, that volume was ‘not a work of reference but a book kept under my pillow – a bedtime story for a chess child’. Nimzowitsch’s aim was to teach positional chess, and Petrosian expresses the interesting view that ‘the teaching of positional play is equivalent to the teaching of chess in general’. But of all the articles, perhaps the most remarkable is a ten-page account by Petrosian, published here for the first time, of the 1963 match against Botvinnik which brought him the world title. He is typically generous about his opponent: ‘Botvinnik, like no-one else, is able to arrive for the start of an event in the highest state of preparedness and from the very first moves to play at full strength.’

The book has been produced with painstaking care, although opponents’ first names and the exact dates of games might have been incorporated. (In the past it was common practice for precise dates to be given in primary sources, whereas nowadays, curiously, this is a compliment generally reserved for world championship games.) An extensive spot-check of game-scores revealed no printing errors at all, and the quality of the English also provides a refreshing contrast to many chess books churned out nowadays. The work has been translated and edited by Kenneth P. Neat, the highly respected translator of some 50 Russian titles.

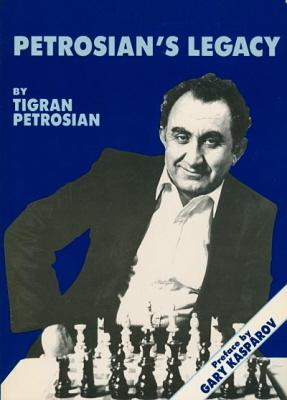

Among other books on Petrosian, English-language readers have long been familiar with those by Clarke (Bell, 1964), O’Kelly de Galway (Pergamon, 1965) and Vasiliev (Batsford/RHM, 1974). In 1990 two further titles appeared. Petrosian the Powerful by Andrew Soltis and Ken Smith (Chess Digest) presented 30 games with entertaining annotations but was poorly structured, having no games at all from the years 1967-1981. Petrosian’s Legacy (Editions Erebouni) was a compilation, also by Eduard Shekhtman, of Petrosian’s writings. Despite some overlap with the new Pergamon book, few will regret acquiring both.

Much has been written about Petrosian’s amenability to an early handshake and his inexplicable (Botvinnik’s word) playing style, which never made him a favourite with those columnists or anthologists chiefly interested in printing 25 or 30 moves of glitter. Diversity of styles at world championship level is proof of the richness and profundity of chess, but Petrosian was perhaps the first reigning world champion whom ordinary players felt free to patronize, as though it was unforgivable for him not to play like Tal. His tournament results were seldom outstanding, and the ‘Petrosian Problem’ had a lengthy airing in the pages of CHESS in 1967-68, with the late Wolfgang Heidenfeld, a formidable debater, leading the prosecution’s case against ‘a king of shreds and patches’. Petrosian was not indifferent to criticism, even admitting that when a Soviet article on the 1956 Candidates’ event ignored him despite his equal third place, ‘I began seriously wondering whether I shouldn’t give up chess’. Although he could be sublimely uncompetitive, it is worth recalling that he was the only one of the seven world champions between Alekhine and Karpov to win outright two consecutive title matches. Ultimately what counts, even more than sporting results, is the character and depth of a player’s talent and the quality of his best games, and in this respect Petrosian’s peers have been notably more appreciative than the chess commonalty. After failing to dethrone him in 1966, Spassky described Petrosian as ‘first and foremost a stupendous tactician’. Kasparov has reported, referring to a post mortem session in 1981, that ‘I found that Petrosian’s positional judgement was considerably deeper than my own’.

The Games of Tigran Petrosian takes us up to the half-way mark in Petrosian’s six-year reign as world champion, a second volume being planned for the final two decades of his life. More vicissitudes were in store, but Petrosian’s imperturbability at the board seems to have been matched by equanimity about his overall career. On page 216 of this fine book he records: ‘Looking back, I rarely recall vexations and disappointments. Compared with the joys which chess has generously given me, they are mere trifles.’

Afterword: This book review first appeared on page 36 of CHESS, October 1991. The second volume, referred to in the final paragraph above and covering the years 1966-83, was published by Pergamon Press shortly afterwards. Later in the 1990s, ‘complete games’ collections for prominent masters returned to fashion.

‘Petrosian is probably the weakest player who has ever held the world championship.’

Source: The Final Candidates Match Buenos Aires, 1971 by R. Fine (Jackson, 1971), page 4.

(2758)

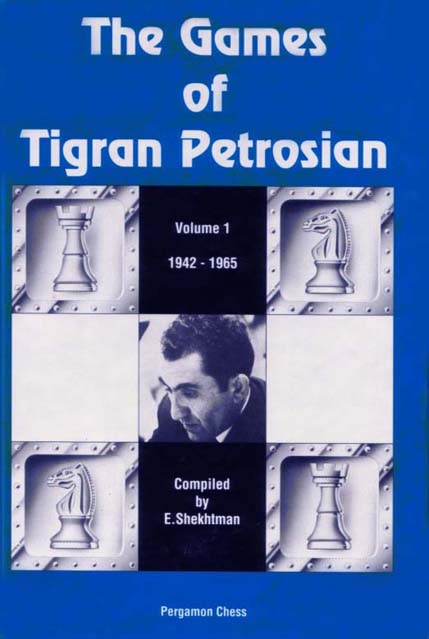

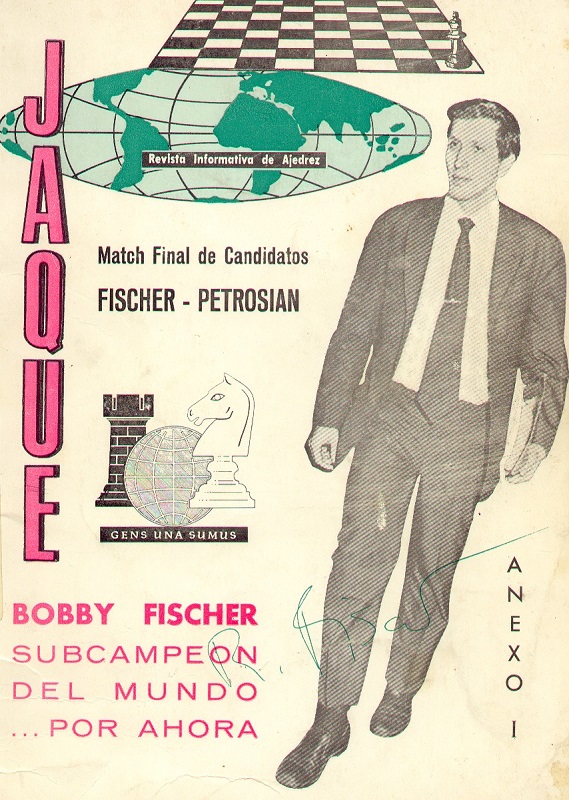

C.N.s 2698 and 2774 reproduced photographs of Petrosian and Fischer (signed, respectively, in green and black) from our copy of the Jaque volume (published in San Sebastián in 1971) on their Candidates’ match. We believed the signatures to be original, but Andy Ansel (Walnut Creek, CA, USA) now informs us that his copy of the book bears identical inscriptions.

(3407)

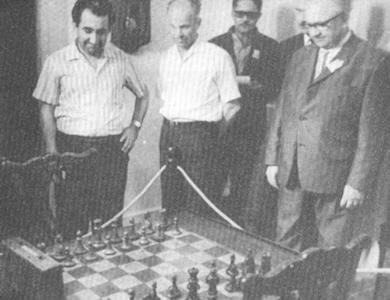

From page 97 of the book Cuba/66 XVII olimpíada mundial de ajedrez comes a photograph of Tigran Petrosian ‘and other masters’ looking at the board used in the 1921 world championship match between Lasker and Capablanca:

(3997)

At a press conference in Belgrade on 26 October 1992 Boris Spassky stated that Tigran Petrosian had been ‘the richest man in the Soviet Union’.

Source: page 230 of No Regrets by Y. Seirawan and G. Stefanović (Seattle, 1992).

Can Spassky’s assertion be corroborated?

(4619)

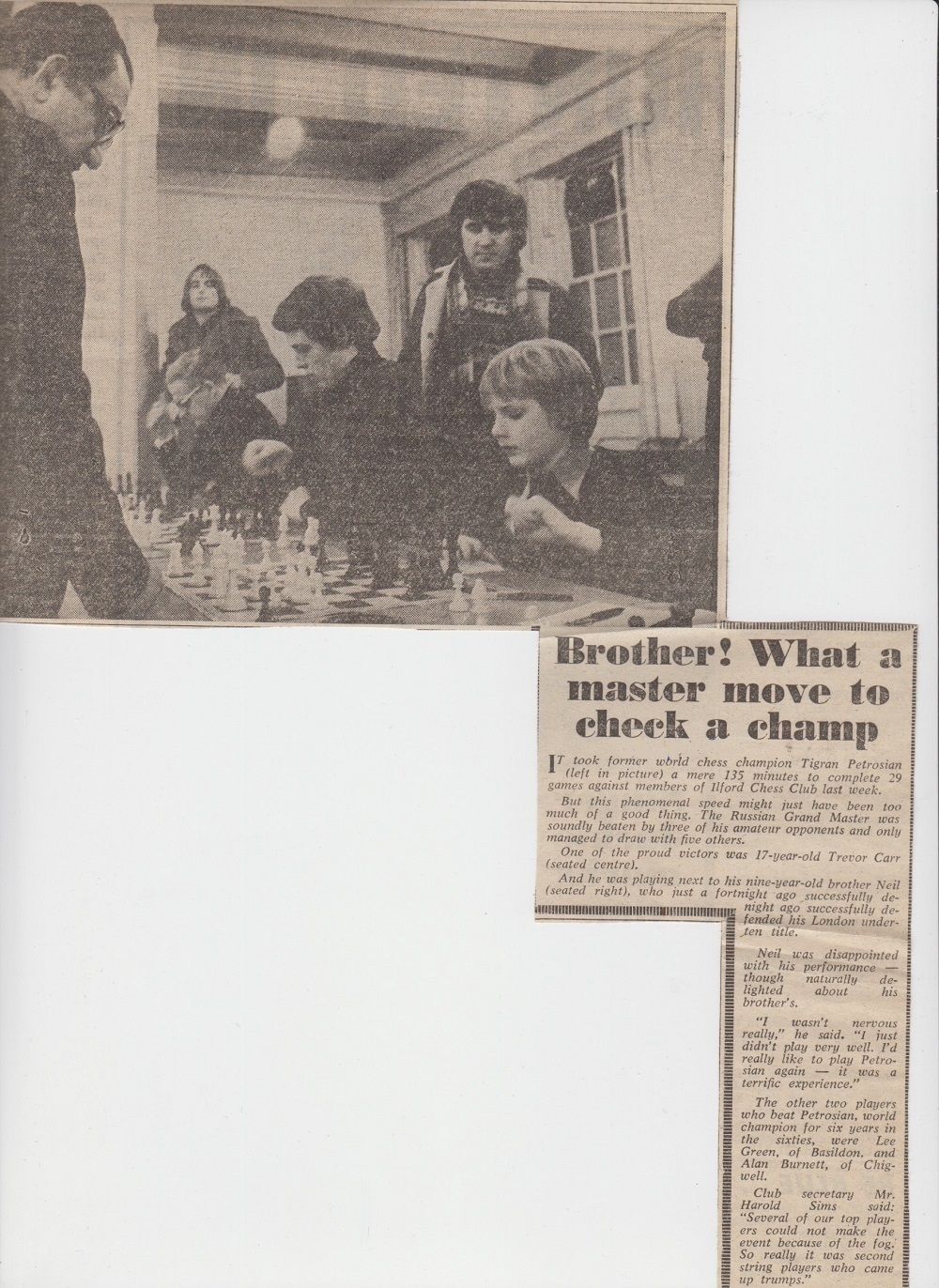

From Harry Woolverton’s column in the Ilford Recorder, 16 February 1978 we take a loss by Tigran Petrosian in a simultaneous display:

Tigran Petrosian – Trevor Carr

Ilford, 1978

Queen’s Pawn Opening

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Bg5 d5 4 Nbd2 Nbd7 5 e3 b6 6 Ne5 Nxe5 7 dxe5 h6 8 Bh4 g5 9 exf6 gxh4 10 Bb5+ Bd7 11 Bxd7+ Qxd7 12 Qh5 Qa4 13 b3 Qa5 14 a4 Qc3 15 Rd1 Qxf6 16 O-O Rg8 17 Kh1 Bd6 18 Nf3 O-O-O 19 Qxh4

19...Rg5 20 e4 Rdg8 21 exd5 Qg6 22 Nxg5 hxg5 23 Qg4 f5 24 Qe2 e5 25 g3 Rh8 26 f3 Qh7 27 Qg2

27...e4 28 fxe4 f4 29 gxf4 gxf4 30 Rd3 Rg8 31 Qe2 Qg7 32 Rdf3 Bc5 33 h3 Qd4 34 Kh2 Rg1 35 c3 Qg7 36 b4 Qg3+ 37 White resigns.

Woolverton remarked:

‘The winner, who is 17, has been somewhat overshadowed by his brilliant young brother, Neil, but he is a fine player in his own right.’

The newspaper’s chess column of 9 February 1978 gave another loss by the former world champion (to A.L. Burnett), as well as this account of the display:

‘Before commencing Mr Petrosian stated that he did not wish to play longer than three hours, at 48 he tires more rapidly, and shortly before he had received a pounding from some stiff opposition at the YMCA, where after 5½ hours he lost nine and drew 11 games out of 30.

But at Ilford against a more modest challenge his speed was remarkable; in the first hour he had made 23 circuits of the arena. Of all those who have played at Ilford he was the fastest, and this includes many of the greatest names the game has known. The quality of the play suggests that he is now a little over the hill for such exhibitions, but even so it was an impressive tour de force.’

Petrosian lost three games and drew five, but the total number of boards was not specified.

(5239)

We have now found a further cutting, from an unidentified local newspaper dated 26 January 1978, with a photograph from Petrosian’s display and stating that it took him ‘a mere 135 minutes to complete 29 games against members of Ilford Chess Club last week’. On the right is Neil Carr (aged nine), and seated next to him is his 17-year-old brother, Trevor.

(5260)

Yakov Zusmanovich (Pleasanton, CA, USA) raises the subject of the earliest books on Petrosian and Korchnoi. He proposes the following:

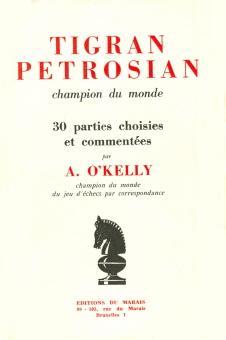

We add that the Wildhagen book was published before Petrosian became world champion (it being briefly reviewed on, for instance, page 118 of the April 1963 BCM). Another early volume was Tigran Pétrosian champion du monde by A. O’Kelly (Brussels, undated, but 1963 or 1964).

(5470)

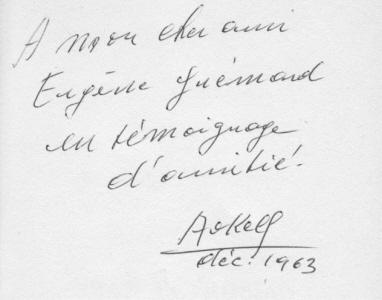

C.N. 5470 referred to ‘Tigran Pétrosian champion du monde by A. O’Kelly (Brussels, undated, but 1963 or 1964)’. Dominique Thimognier (St Cyr sur Loire, France) shows that the book was published in 1963, since he possesses a copy inscribed by O’Kelly to his friend Eugène Guémard in December 1963:

(5486)

Tim Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) writes: ‘I very much like Petrosian’s Legacy (Los Angeles, 1990) and wish it had been properly edited.’ He quotes these extracts:

(5675)

Regarding this photograph taken during the 1953 Candidates’ tournament in Neuhausen and Zurich (C.N. 3956), we are informed by Grzegorz Siwek (Warsaw) that the figure on Kotov’s left is D. Postnikov.

The latest key is thus: Averbakh, N.N., Keres, N.N., Perret, N.N., N.N., Kotov, Postnikov, N.N., Taimanov, Geller and Petrosian.

(6225)

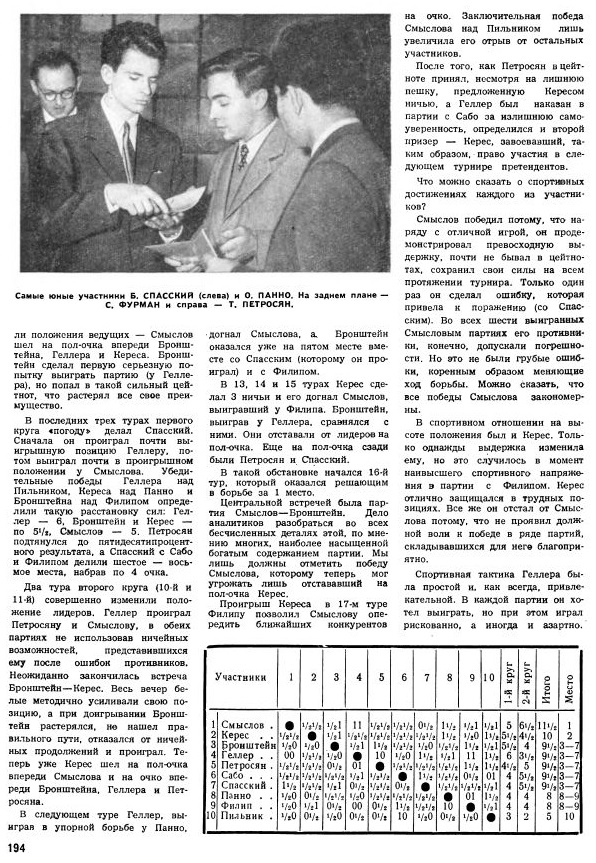

From the front cover of the May 1963 Chess Life:

(6661)

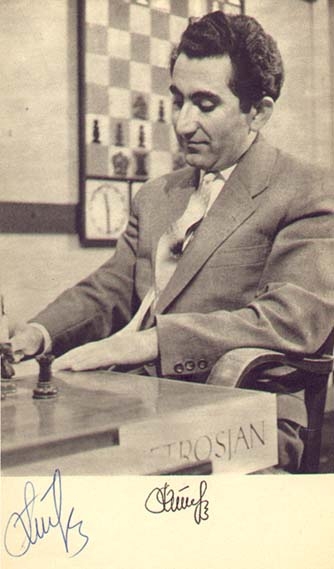

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) draws attention to a photograph of Petrosian (signed by the master overleaf) in his collection:

(6702)

From an article by Boris Spassky ‘The Petrosian-Korchnoi Match: Petrosian Was True to Himself’ on pages 625-627 of the November 1971 Chess Life & Review:

‘The most outstanding feature in the style of ex-world champion Tigran Petrosian is his desire to keep his opponent at his own distance. This can be seen in every game as well as in the overall plan of the match. This is purely his own individual style, his chess character.

Victor Korchnoi may be described as a searching chessplayer. To me, he seems more a destroyer of the other player’s plans and positions rather than a creator. His strength is most evident in counter-attacks. He is known for his flexible playing style and colossal energy and working capacity during a game ...

Korchnoi is also a fighter with stubbornness that anyone could envy. He is tenacious in defense and can become quite “angry” – in the sports sense of that word. When he tackles a problem that comes up over the board, I believe the Leningrad grandmaster has a tendency not to trust his intuition; rather, he relies more on hard, cold calculations. His ability to figure out various continuations far in advance helps him in the endgame.

By his style, Korchnoi is more a tournament player than a match player. Sometimes, when he gets carried away by his ideas and original plans he does not reckon with the more prosaic aspects of chess. One of his shortcomings in his “ability” to get into time-trouble.

Comparing the styles of the two players, it must be said that Petrosian is a tough opponent for Korchnoi. After all, during the course of the struggle Korchnoi has to be able to discover his opponent’s plan in order to begin “destroying” it. But Petrosian’s style is often based on waiting, maneuvering, “semi-tones”. That is why the temperamental Korchnoi often had to shoot at blind targets.’

(7005)

Rick Massimo (Providence, RI, USA) points out a remark by Igor Botvinnik about his uncle on page 9 of Botvinnik-Petrosian The 1963 World Chess Championship Match (Alkmaar, 2010):

‘I had the impression that he did not like to be reminded of this match loss, and it was a subject we hardly ever spoke about. However, when he occasionally talked about the pre-match negotiations, and the story of Petrosian’s sealed move in Game 5, he did say that his nerves had been “preyed upon”.’

Finding no information elsewhere in the book regarding an incident in the fifth game, Mr Massimo asks what happened.

Botvinnik gave the following account on pages 171-172 of Achieving the Aim (Oxford, 1981):

‘I played the match not too well. A definite effect on my state of mind was produced by an incident in the fifth game. At the start of the adjourned session (the game was adjourned in a winning position for Petrosian) the judge Golombek (England) opened the envelope and, after looking at Petrosian’s score sheet, made a losing [sic] for Petrosian. The latter protested energetically; then Golombek shrugged his shoulders and made the move which my opponent insisted on.

After my loss in this game I approached Golombek for an explanation (according to the rules if the judge is doubtful about which move has been made, i.e. if there is an inaccuracy in the writing, then a loss is awarded). Golombek replied that the move was indeed not clear, but he was not in agreement with such an interpretation of the rules. I was infuriated. This legal point had been decided when I was still a young man. I approached Ståhlberg – he supported the position of his colleague.

Then I demanded a photocopy of the score sheet. This was provided a week later. All week I was nervous and managed to lose yet another game. However, the unpleasantness lay in the fact that although Petrosian had written the move down inaccurately there could be no doubt about deciding what move had been sealed, and Petrosian had complete justification for his protest at the adjournment.

I felt bitter at my old friends, the match judges. I just couldn’t understand why they had created such a groundless conflict.’

Golombek covered the match for the BCM, with much detail on matters large and small, but we see no reference to this adjournment incident. Petrosian’s sealed move was 41 Kf7. Is it known whether his score-sheet for the game has survived?

(7141)

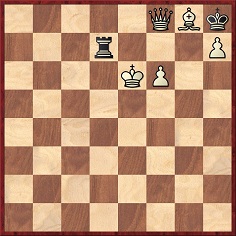

White to move (adjournment position)

Peter Wood (Hastings, England) cites the note to 41 Kf7 on page 147 of Tigran Petrosian His Life and Games by Vik L. Vasiliev (London, 1974):

‘Undoubtedly the strongest, which unexpectedly called forth a protest from the opponent. Here Botvinnik turned to the match arbiter and claimed that White had sealed the impossible move 41 K-B8?? (into check!).

One of Petrosian’s “small weaknesses” is that he has a habit of writing the number 7 with a round tail ... in a word, the mediation of the judge was called for, and after the truth of the matter was established, play continued. The nervous strain of a hard match sometimes produces the most unexpected conflicts!’

(7146)

C.N. 13 (see page 232 of Chess Explorations) cited a quip by Petrosian during the 1974 Karpov v Korchnoi match, from page 166 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980):

‘The press centre was linked to the stage by four television screens. Arranged in groups around the chessboards, grandmasters and journalists analysed the position, periodically glancing at the screens. At the start of the match (before his departure to the international tournament in Manila) perhaps the most popular figure in the press centre was Petrosian. The journalists would constantly turn to the ex-world champion: “Tigran Vartanovich, what should be played here?” “When I knew that, I was down on the stage, instead of up here”, was Petrosian’s joking reply.’

(8410)

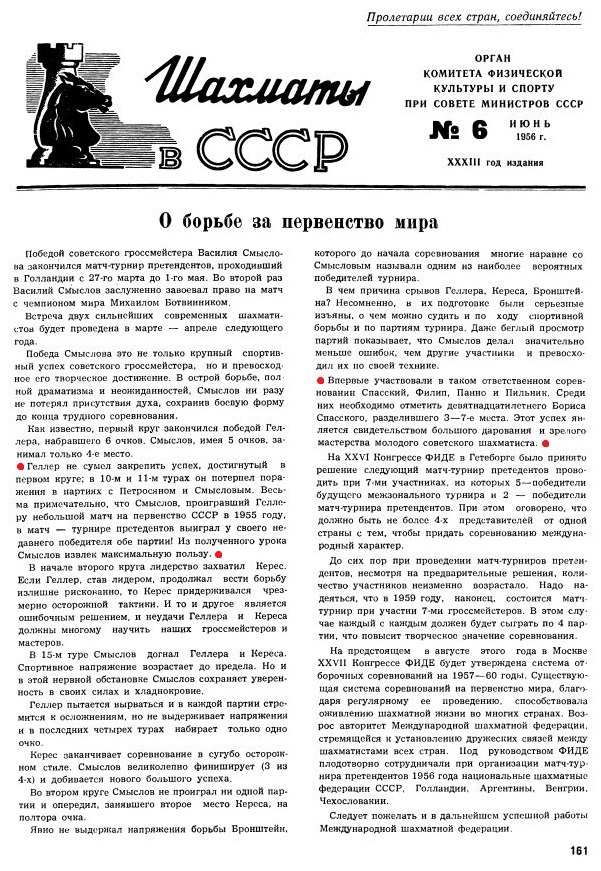

Our review of The Games of Tigran Petrosian (see above) refers to his reaction to press coverage of his performance at Amsterdam, 1956, and below are his comments in full, from pages 215-216 of the book:

‘That same year [1956] an article appeared in the magazine Shakhmaty v SSSR, where the performances of the participants in the Amsterdam Candidates’ tournament were analyzed. I had not played badly there: out of the ten participants I had shared 3rd-7th places. But the article discussed the creative achievements of only nine grandmasters – from the winner, Smyslov, to Pilnik, who brought up the rear. I was not even mentioned – it was as though I had not even played in the tournament.

I must confess that this so wounded me that I began seriously wondering whether I shouldn’t give up chess.’

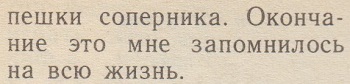

Timothy J. Bogan asks what exactly appeared in Shakhmaty v SSSR, and we are grateful to Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) for providing page 161 of the 6/1956 issue (Editor: V. Ragozin). The unsigned editorial contained one mention of Petrosian, in the fifth paragraph. Later, it discussed the other four players who shared third place with him (the four being singled out as newcomers to that level of competition):

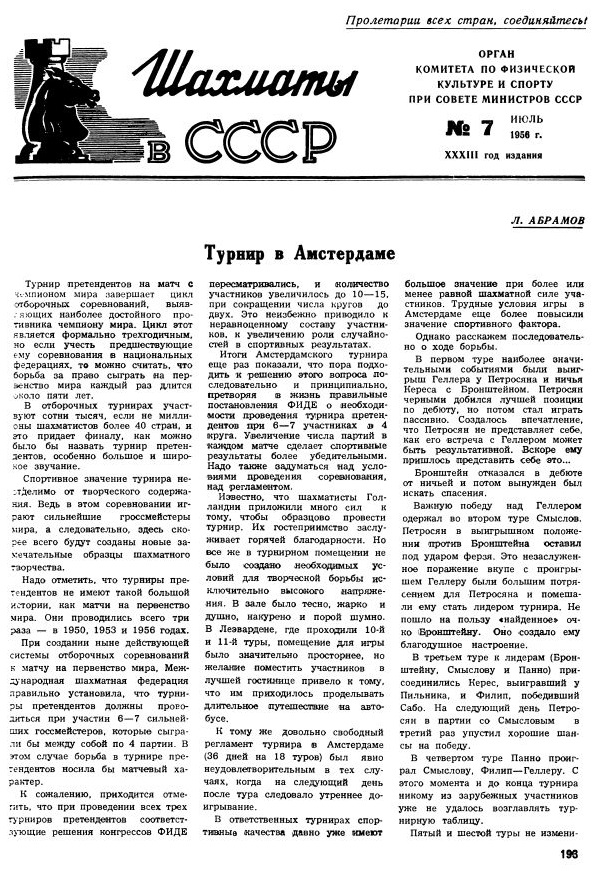

Mr Scoones has also forwarded an article about the tournament by L. Abramov on pages 193-195 of the 7/1956 magazine. It included a brief discussion of Petrosian’s performance on page 195:

(8919)

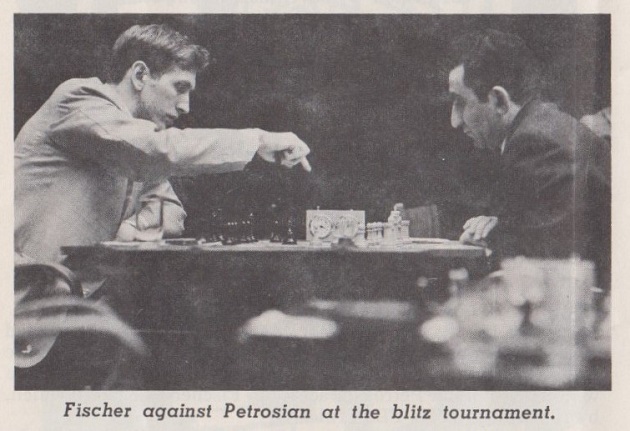

A photograph taken at Herceg Novi, 1970:

Source: Chess Life & Review, June 1970, page 302.

(9114)

Dan Scoones writes:

‘Despite the caption in Chess Life & Review, I believe that the photograph was taken not during the Herceg Novi blitz tournament but in the second round of the USSR v the Rest of the World match in Belgrade. The Belgrade game began 1 c4 g6 2 Nc3 c5, which corresponds to the position in the photograph, whereas the Herceg Novi game opened 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 g6. Moreover, the design of the players’ chairs is consistent with the ones used in Belgrade, and in all the Herceg Novi photographs that I have seen there were white tablecloths. Finally, the shade of Fischer’s jacket matches other Belgrade photographs, but not pictures taken in Herceg Novi.’

(9119)

Photographs received from Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

Illustrated London News, 30 March 1963, page 456

Illustrated London News, 1 June 1963, page 859

Illustrated London News, 8 June 1963, page 882.

(9037)

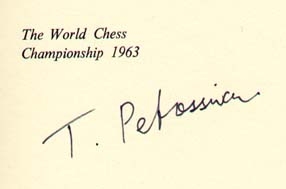

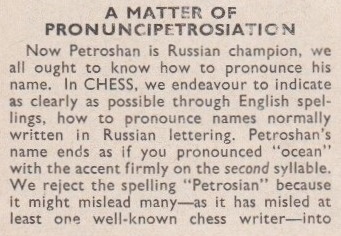

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks about the transliteration of Tigran Petrosian’s surname, shown on page 419 of A Chess Omnibus:

It comes from our copy of The World Chess Championship 1963 by R.G. Wade (New York, 1964), and the inscription was obtained by the book’s previous owner, Alan Benson. What other specimens exist of Petrosian’s signature in the Roman alphabet, and did he customarily write ‘Petrossian’ (the standard spelling in French-language publications)?

‘Petrosyan’ is sometimes seen. CHESS favoured ‘Petroshan’, for the reasons set out (under the heading ‘A matter of pronuncipetrosiation’) on page 137 of its March 1959 issue:

(9470)

C.N. 9470 discussed how Petrosian wrote his name in the Roman alphabet. David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) now reports that he has a copy of Tigran Petrosian His Life and Games by Vik L. Vasiliev (London and New York, 1974) in which Petrosian signed the first photograph in the plate section:

(9518)

Unlikely as it may seem, the 1971 Candidates’ Final match between Petrosian and Fischer prompted a set of five chess cartoons by Bill Tidy on pages 494-495 of Punch, 13 October 1971. The first one is indicative of their standard:

(9471)

The opening paragraph of ‘How Does The World Champion Play Chess?’ by John Hammond on page 2 of Chess World, January 1967:

‘Petrosian sees chess as the organization of available chess space. This, basically, is what chess is. Mate in itself is the denial of space to the opposing king. The idea is as old as chess itself, but the difficulty is to make it work.’

(9693)

A photograph taken during the Candidates’ tournament in Yugoslavia, 1959:

From left to right: Petrosian, Golombek (chief arbiter), Tal, Gligorić, Smyslov, Benko, Fischer, Ólafsson, Keres.

Source: Chess Review, December 1959, page 360. A less clear copy of the picture is opposite the imprint page of Kandidatenturnier für Schachweltmeisterschaft by S. Gligorić and V. Ragozin (Belgrade, 1960) with the caption ‘Alle Spieler mit grossen Hoffnungen: Vor dem Turnierbeginn in Bled’.

(10332)

Frank Camaratta (Huntsville, AL, USA) asks whether photographs are available of Herman Steiner with the violist William Primrose (1904-82).

Adding that Steiner’s chessmen were used in a number of high-profile events in the 1950s and 60s, including the Fischer v Reshevsky match and the Piatigorsky Cup, our correspondent provides two photographs, taken with the agreement of the Steiner family, as well as a shot of Petrosian playing with the set.

(10599)

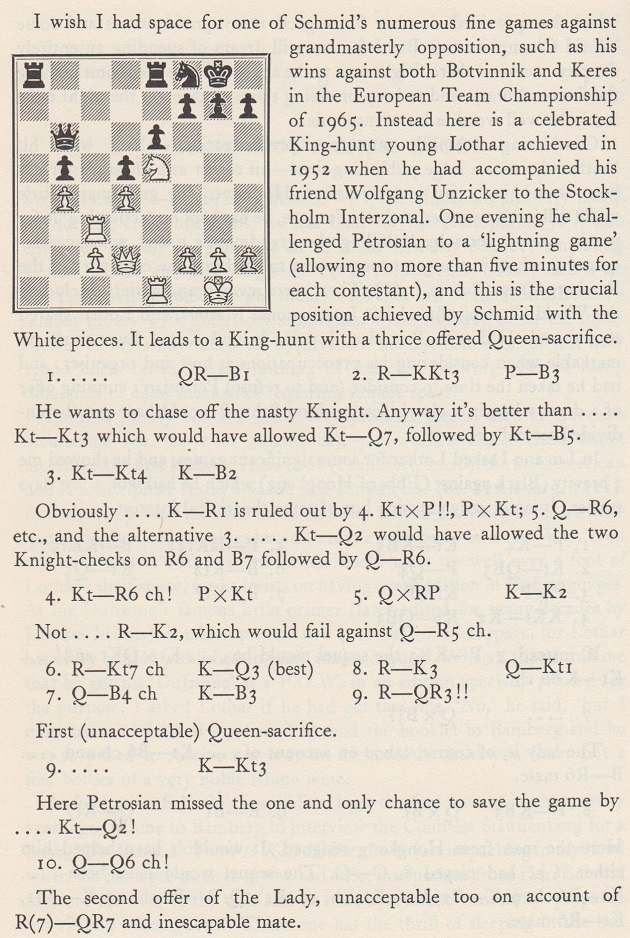

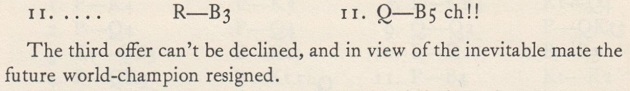

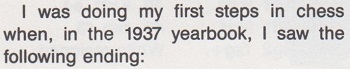

From pages 306-307 of The Delights of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1974):

Assiac had also presented the conclusion on page 202 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

1 e4 c6 2 Nc3 d6 3 d4 Nf6 4 Bf4 Qb6 5 Qd2 Nbd7 6 Nf3 e6 7 Bd3 Be7 8 O-O O-O 9 a4 Qc7 10 e5 Nd5 11 Nxd5 cxd5 12 Rae1 Re8 13 Re3 Nf8 14 Rfe1 Bd7 15 a5 a6 16 exd6 Bxd6 17 Bxd6 Qxd6 18 Ne5 Bb5 19 Bxb5 axb5 20 b4 b6 21 axb6 Qxb6 22 Rc3 f6 23 Ng4 Rac8 24 Rg3 Kf7 25 Nh6+ gxh6 26 Qxh6 Ke7 27 Rg7+ Kd6 28 Qf4+ Kc6 29 Re3 Qb8 30 Ra3 Kb6 31 Qd6+ Rc6 32 Qc5+ Resigns.

The full score of this allegedly ‘celebrated’ game is in databases, but which is the earliest, or best, primary source?

(11178)

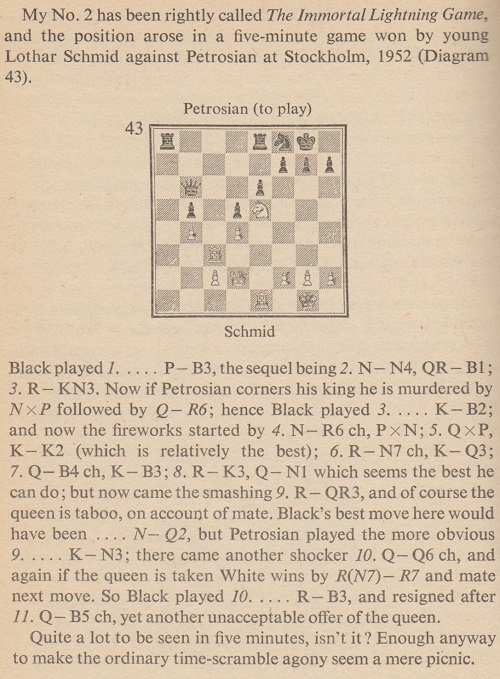

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) sends a report by Lothar Schmid on pages 382-383 of Caissa (‘2. Oktober-Heft 1952’):

(11182)

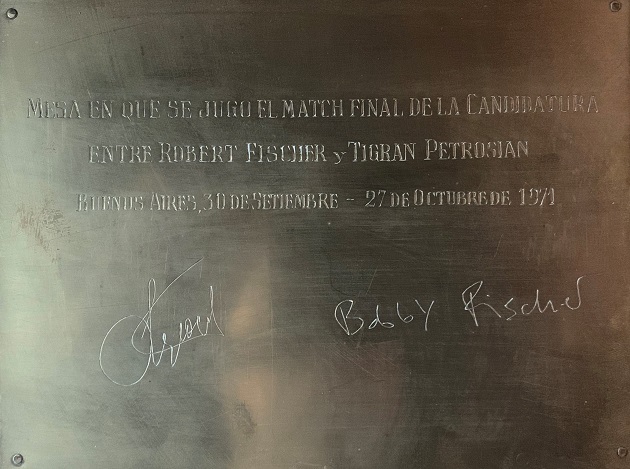

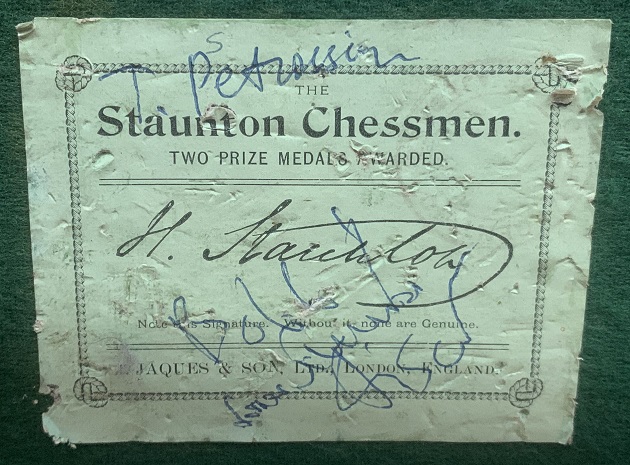

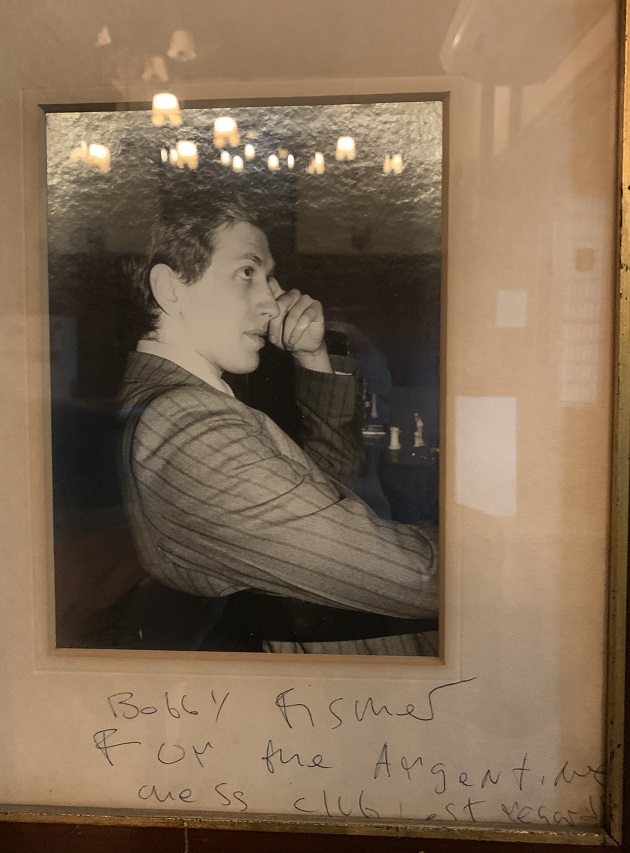

In C.N.s 11219 and 11278 Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) presented a number of photographs taken by him at the Club Argentino de Ajedrez during visits to Buenos Aires earlier this year. In addition, he put us in contact with Mr Carlos León Cranbourne (Buenos Aires), who has now sent us many further pictures.

The present item focuses on Fischer, and, in particular, his 1971 match in Buenos Aires against Petrosian:

The board in the fourth picture shows the conclusion of the final game of the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match.

(11330)

From the Keystone Pictures archives Olimpiu G. Urcan has obtained permission for us to reproduce a photograph of Petrosian with Fidel Castro (Havana, 1966):

(11379)

Tim Bogan submits a pair of quotations:

Page 112 of Training for the Tournament Player by M. Dvoretsky and A. Yusupov (London, 1993), in the chapter ‘Studying the Classics’ by M. Shereshevsky;

Page 90 of Chess Training for Candidate Masters by A. Kalinin (Alkmaar, 2017). The paragraph reported on a 1979 speech by Petrosian.

A general remark about the latter book is that although the imprint page promises, ‘we will collect all relevant corrections on the Errata page of our website’, a start has yet to be made.

(11630)

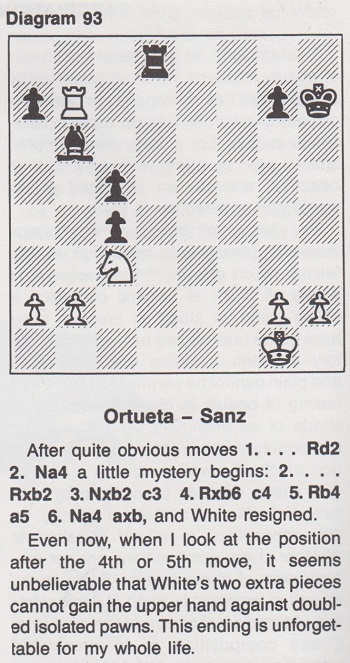

The Ortueta v Sanz ending was highly appreciated by Tigran Petrosian. From pages 136-137 of the posthumous anthology of his writings Шахматные лекции (Moscow, 1989):

Below is the translation on page 94 of the English edition, Petrosian’s Legacy (Los Angeles, 1990):

(11639)

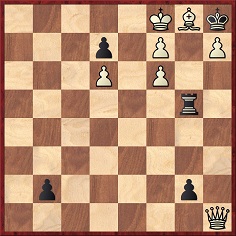

The Petrosian book mentioned in the previous item demonstrated his appreciation of endgame studies with a discussion of three compositions by V. Korolkov and three by H. Rinck. The Korolkov selection included the following:

White to move and win

1 Qg1 b1(Q) 2 Qxb1 g1(Q) 3 Qxg1

3...Rg3 4 Qg2 Rg4 5 Qg3 Rg5

6 Qg4 Rxg4 7 Ke7 Re4+ 8 Kxd7 Rd4 9 f8(Q)

9...Rxd6+ 10 Ke7 Rd7+ 11 Ke6

11...Re7+ 12 Kd6 Rd7+ 13 Ke5 Re7+ 14 Be6+.

This study won second prize in a competition held by Shakhmaty v SSSR in 1938 and was published on page 90 of the February 1938 issue.

(11640)

Note: before being expanded on 24 November 2024, this article was entitled Petrosian’s Games.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.