Edward Winter

See C.N.s 2366 and 9723 below.

General

A quote for filing in the department of unnecessary caution from P. Sunnucks’ The Encyclopaedia of Chess (London, 1976), page 364:

‘Philidor: One of the greatest players of the eighteenth century.’

‘The greatest by a mile’ would have been a more worthy comment.

(433)

C.N. 2323 reported that the term ‘the father of modern chess’ was applied to Philidor by the London correspondent of the International Chess Magazine on page 167 of the June 1888 issue. A footnote on page 344 of A Chess Omnibus added that there was an article on Philidor entitled ‘The Father of Modern Chess’ on pages 207-214 of the May 1893 BCM.

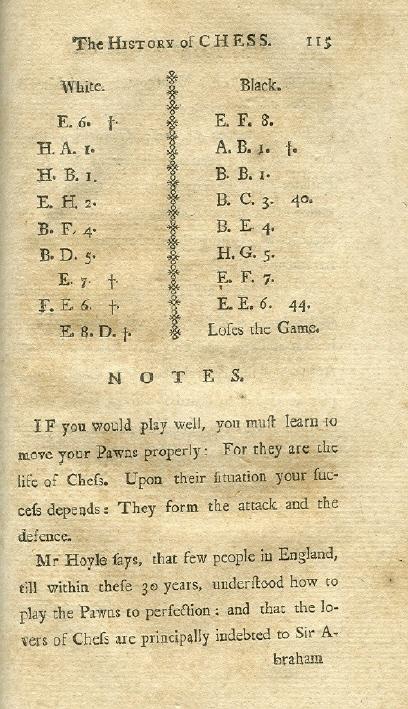

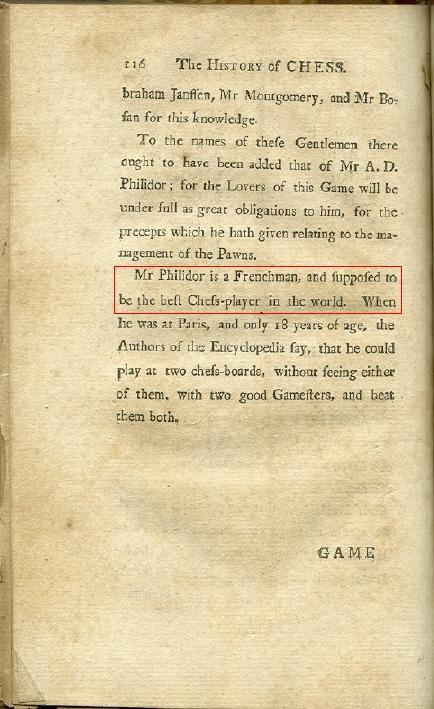

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) has submitted the following from Richard Lambe’s The History of Chess (London, 1764):

William J. Stewart (Glasgow, Scotland) is seeking information about Captain Smith, who lost a well-known game to Philidor in London in 1790.

The ‘notices biographiques’ in the authoritative book Philidor musicien et joueur d’échecs (Paris, 1995) contain merely the following (page 229):

‘Smith, le Captain. Joueur d’Échecs. On connaît surtout la partie qu’il joua contre Philidor le 13 mars 1790 et qui a été plusieurs fois commentée.’

(5017)

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) is seeking substantiation of a statement on page 106 of A History of Chess by Jerzy Giżycki (London, 1972):

‘Philidor thought, for instance, that whoever made first move and made no mistake would win.’

(5887)

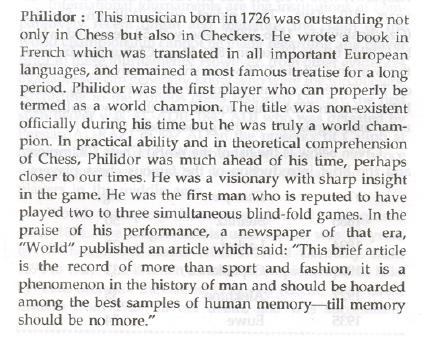

As shown in our feature article on Chess (Basics, Laws and Terms) by B.K. Chaturvedi (Chandigarh, 2001), that book copied extensively from Chess Made Easy by C.J.S. Purdy and G. Koshnitsky. But now comes a rebondissement: is it possible that the (dire) Indian volume was itself subsequently the victim of plagiarism? Below, on the left, is a passage from page 6 of the Chaturvedi book, alongside the text on page 8 of A Guide To Chess ‘Edited and Revised by Philip Robar’ (New Delhi, 2002):

The next paragraph in both books (pages 7 and 9 respectively) is a particularly bumpy read:

Among other examples of ‘similarities’ are the books’ concluding glossaries, but is it a plain case of plagiarism by the Robar volume? We feel that matters are far from simple. For instance, the imprint page of the Robar book states, however implausibly, ‘XIVth Edition 2002’; if there have truly been 13 previous editions of A Guide To Chess, most, if not all, of them would pre-date the 2001 Chaturvedi book. But who is Philip Robar? And what exactly was ‘edited and revised’ by him for the Guide?

A further consideration is that his name is not on the cover but only on the title page:

Finally for now, an additional mystery concerns the book’s spine: it names the author as ‘Dr C.P. Mithal’.

(4683)

See also An Indian Copying Mystery.

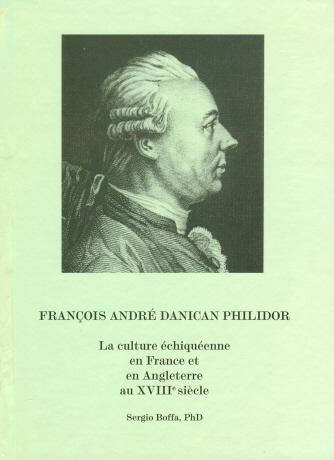

A new book well deserving of an English translation is François André Danican Philidor La culture échiquéenne en France et en Angleterre au XVIIIe siècle by Sergio Boffa (Olomouc, 2010).

(6868)

Trustworthy writers naturally resist the temptation to repeat unverified material, and especially in a domain such as chess lore which is notoriously infested with imprecision and uncertainty.

From page 220 of Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984):

‘I can’t resist repeating that old anecdote about the man going into the café [the Café de la Régence] to watch Voltaire and Rousseau play at chess. Mere scribblers, those two, sniffs an acquaintance. “True, but today they play with Philidor!”’

Information is sought about the tale, which had appeared on page 92 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974):

(8866)

See also the references to Philidor in Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Chess.

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘Glancing at the [chessgames.com] main page today (14 March 2015), I see that it is now attributing a quote to “André Philidor”:

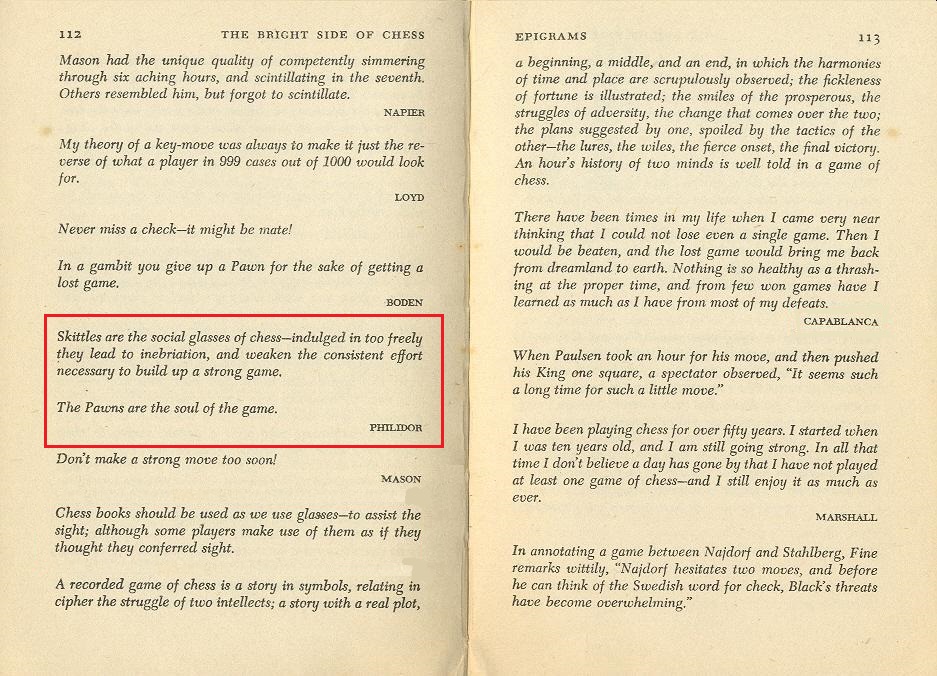

Why would anybody believe that Philidor wrote about “skittles”? My initial search has turned up no pre-twentieth-century occurrences of the quote; it appeared, with no mention of Philidor or anyone else, on page 81 of the December 1904 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine ...’

(9156)

As noted in Chess: the Need for Sources, it seems that, once again, the lay-out of unrelated and sometimes anonymous quotes in the epigrams chapter in The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948) caused the original confusion:

The shortest item in Curious Chess Facts by Irving Chernev (New York, 1937) was on page 14:

‘Philidor never played Philidor’s Defence!’

See too page 13 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974).

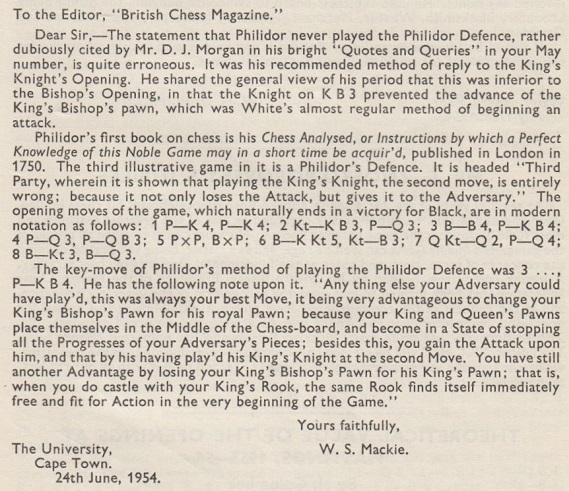

D.J. Morgan mentioned the matter briefly and cautiously (‘Philidor, it is said, never played the Philidor Defence’) on page 157 of the May 1954 BCM, and a letter from W.S. Mackie of Cape Town was published on page 257 of the August 1954 issue:

Suggestions are invited as to when the name ‘Philidor’s Defence’ was first attached to 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6.

(9220)

Bob Meadley (Narromine, NSW, Australia) has sent us two large files of information on François-André Danican Philidor: part one; part two.

(10876)

Blindfold chess

An excerpt from page 19 of “En Passant” Chess Games and Studies by George Koltanowski (Edinburgh, 1937):

‘When Philidor, the Frenchman, in 1816 played six games blindfold the Press went mad, thinking it an eighth wonder ...’

It certainly would have been. Philidor had died in 1795.

Kings, Commoners and Knaves, page 302

A book which has received insufficient attention in chess circles is Philidor musicien et joueur d’échecs, published by Picard in 1995. It reproduces (pages 65-191) Philidor’s correspondence in London from 1783 to 1795, and the letters include a number of references to chess. With regard to the two passages below (excerpts from letters to his wife) it should be noted that the text is two steps removed from modern French. Eighteenth-century spelling differed slightly from today’s usage and, as remarked on page 65 of the book, Philidor had a carefree attitude to spelling.

Letter dated 23 February 1790:

“Samedy prochain, je jouerai trois parties a la fois, deux de mémoire et la 3eme en voyant l’échiquier. Je t’assure que cela ne me fatigue pas autant que bien des gens peuvent le croire. Ainsi, n’ait aucune inquiétude pour ma santé.”

Letter dated 2 March 1790:

“J’ai joué samedy dernier mes 3 parties a la fois, l’une en voyant, contre le comte de Bruhl, et les deux autres sans voir, contre le Dr Riollay et le capitaine Smith. Celle du Comte a été remise, et j’ai gagné les deux autres. Il y avait 43 payants et une quinzaine de membres du club, tout le monde a été dans l’enchantement. Il est vrai que j’avais fait diète et vécu de regime pendant quelques jours, et cela m’a réussi, car je n’ai jamais eu les idées aussi nettes. J’ai eu de profits, tous frais payés, huit Louis (ce sont mes lectures). Notre club sera, je crois, très brillans cette saison. Nous avons dinner 14 ce jour la ensemble, et le général Conway a fait la motion a table de répéter les parties sans voir, et un dinner de 15 jours en 15 jours, ce qui a été agréer par moi et par la compagnie. J’avois grand besoin de cet argent, car j’étois presque sans un shilling.”

(2905)

Dale Brandreth has published a scrapbook entitled Chess Columns 1924 & 1925. Most of the items come from the Washington Post (column conducted by W.H. Mutchler) and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (H. Helms). Not all of the reportage is of choice quality, and one of Mutchler’s columns (on page 6 of the scrapbook) even records:

‘When Philidor conducted three games sans voir, the populace of the fifteenth century entered it in the encyclopedias as miraculous.’

(2996)

For the full text of C.N. 2996, see Chess Jottings.

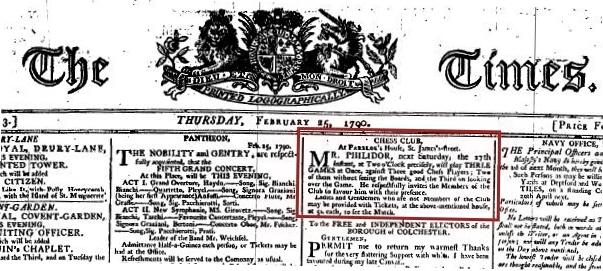

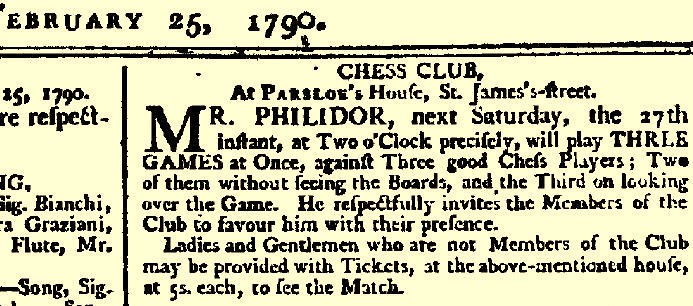

Jon Crumiller (Princeton, NJ, USA) submits this announcement of a blindfold exhibition by Philidor on the front page of the (London) Times of 25 February 1790:

(5299)

Philidor’s legacy

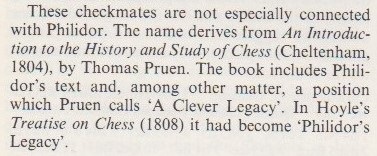

The final paragraph of the entry on Philidor’s legacy on page 306 of the second edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1992):

That information is inaccurate, and there was no reason to mention Hoyle. Strangely, the conclusion of the entry on page 252 of the first edition (Oxford, 1984) of the Companion was shorter and better:

Thomas Pruen’s book, which can be viewed on-line, used the term ‘Philidor’s legacy’ several times.

In his chess column on page 8 of the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 5 February 1916, William Shelley Branch discussed, speculatively though also with a factual contribution from H.J.R. Murray, the origins of Philidor’s legacy, and suggested that it was given that name ‘perhaps for the first time in print’ in Pruen’s book.

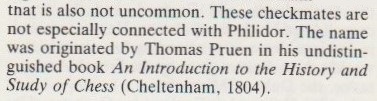

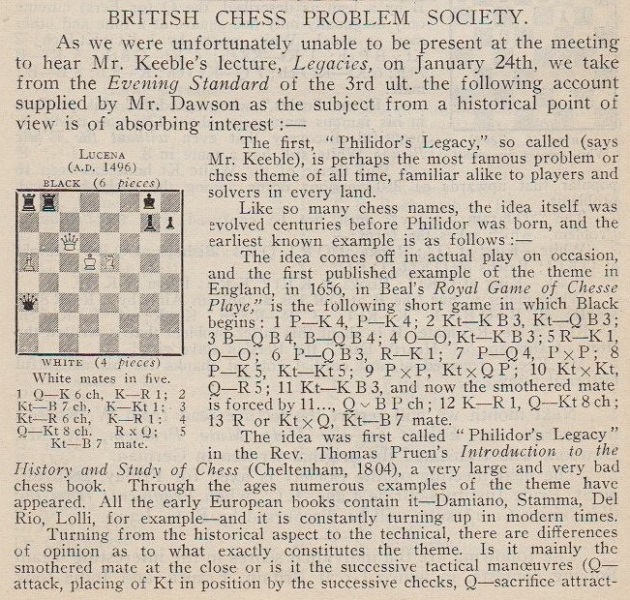

A detailed account of the topic was provided by John Keeble in a British Chess Problem Society lecture, entitled ‘Legacies’, on 24 January 1930. From pages 121-122 of the March 1930 BCM, in the ‘Problem World’ column by B.G. Laws and T.R. Dawson:

Can readers find the report in the Evening Standard of 3 February 1930, or offer a biographical note on Thomas Pruen? He had a dateless entry in the privately distributed 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige.

(9688)

From William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia):

‘Page 873 of Murray’s A History of Chess referred to him as “Rev. Thomas Pruen”. He died on 22 March 1834 at Prince’s Street, Bristol, aged 62 (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 3 April 1834, page 4). His estate was probated in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in May 1834. A Thomas Pruen was baptized on 22 April 1772 at St Mary de Crypt Anglican Church, Gloucester, the son of Thomas and Catherine Pruen.’

(9673)

Pictures

In C.N. 2366 Daniël De Mol (Wetteren, Belgium) drew our attention to various errors on postage stamps with a chess theme, one being a 1988 Guinea-Bissau stamp with a portrait of ‘Fracois’ Philidor. It is shown below, as given in C.N. 9723 courtesy of Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation):

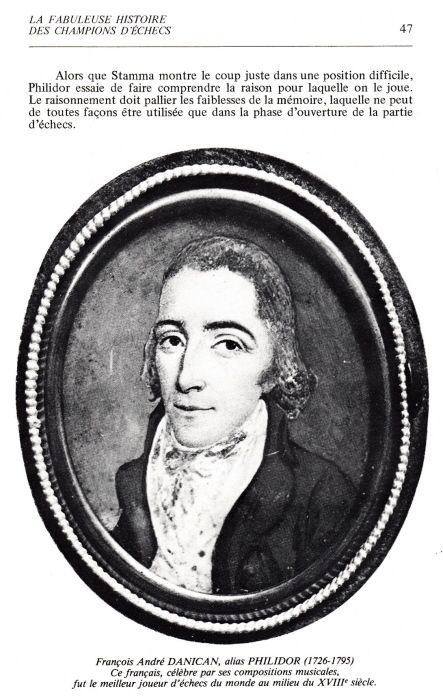

A handful of old portraits of Philidor are known, but one alleged picture stands out as altogether different from the rest. It was published on, for instance, page 47 of La fabuleuse histoire des champions d’échecs by N. Giffard (Paris, 1978) and on page 46 of volume 3 of Lademanns Skak Leksikon by S. Novrup (Copenhagen, 1982). What is known about its origins?

(3431)

Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark) points out that a colour version of the alleged Philidor picture appeared on page 79 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974). Page 248 stated that it came from the Cleveland Public Library.

(3448)

We are grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for providing us with a scan of the original portrait:

The World of Chess and La fabuleuse histoire des champions d’échecs gave the picture in reverse form, as did page 46 of volume 3 of Lademanns Skak Leksikon by Novrup.

The Cleveland Public Library has also sent us documentation about the picture, including a letter dated 8 November 1988 from Jean-François Dupont-Danican and the Library’s subsequent conclusion on a catalogue card that researchers should be discouraged from attributing the portrait to Philidor.

(8691)

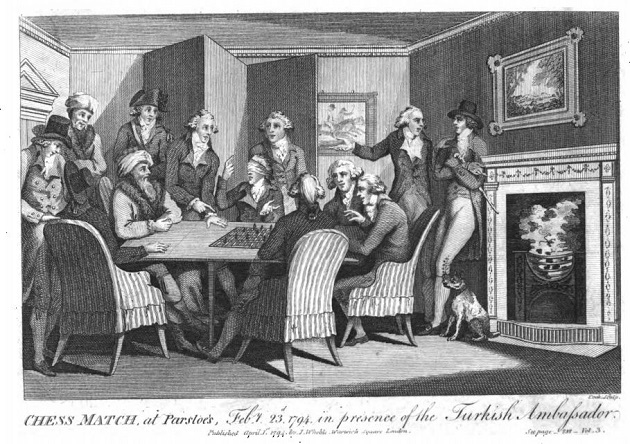

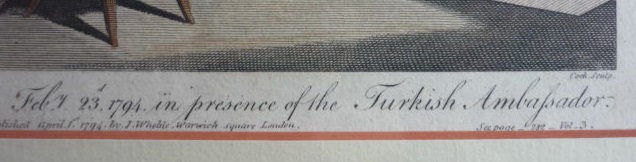

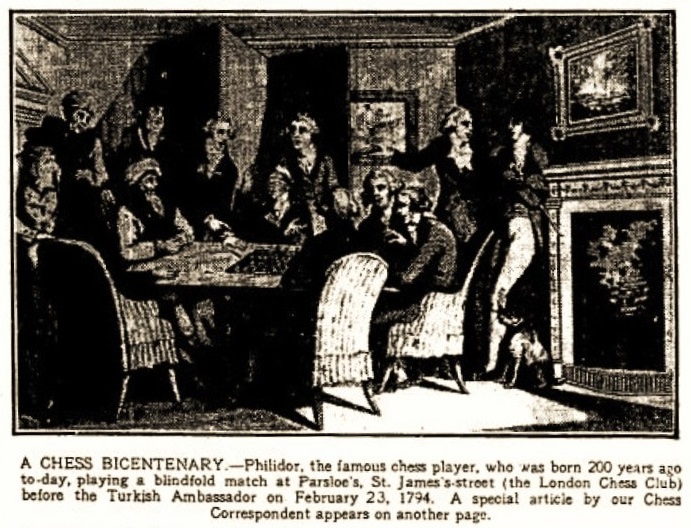

Aaro Jalas (Espoo, Finland) asks for particulars about this famous picture of Philidor, and mentions, by way of example, how it is presented in two books:

We add, firstly, that the picture is also on page 119 of A History of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1976) but with a caption placing it a decade earlier:

‘The acknowledged master of eighteenth-century chess – Philidor playing blindfold at Parsloe’s in London in the presence of the Turkish Ambassador on 23 February 1784.’

A similarly worded caption, also with ‘23 February 1784’, appeared on page 131 of Pocket Book of Chess by Raymond Keene (London, 1988). Page 23 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009) had ‘in the 1780s’, and page 78 of The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974) had ‘c. 1794’.

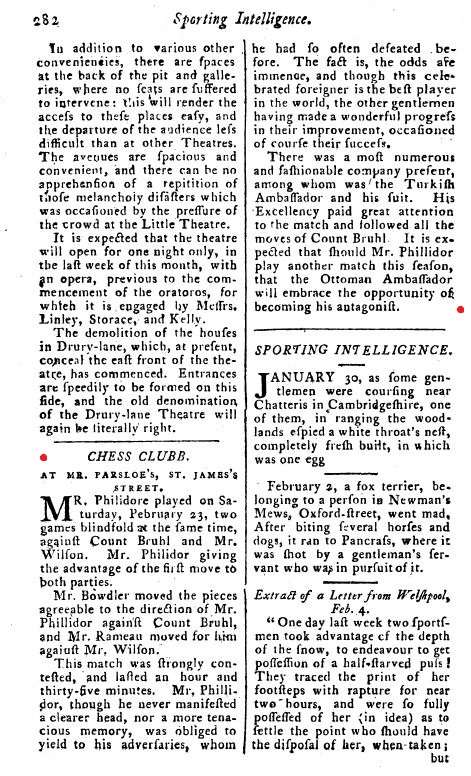

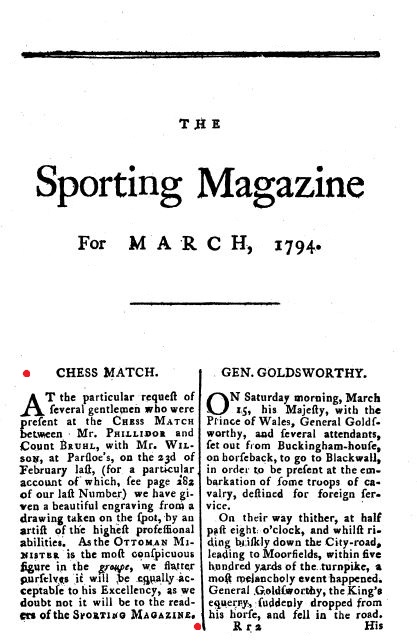

The correct date is 23 February 1794. The engraving was included at the start of volume three of the Sporting Magazine, which covered October 1793-March 1794:

Below are two passages from, respectively, page 282 of the February 1794 issue of the Sporting Magazine and page 297 of the March 1794 edition:

Manfred Mittelbach (Cape Town) reports that he owns a coloured version of the engraving of Philidor’s blindfold display in London in 1794:

Our correspondent also quotes from a letter (London, 25 February 1794) written by Philidor to his wife:

‘J’ai jouée, samedi dernier deux parties sans voir a notre club, et l’ambassadeur turc, qui est résident ici, m’a honorer de sa présence et m’a fait dire par son interprete qu’il reviendroit une autre fois. Il a été très satisfait, ainsi que tout les spectateurs. Cela m’a valu, tous fraix fait, 6 guinées et quelques shillings.’

Source: page 181 of Philidor musicien et joueur d’échecs (Paris, 1995). Philidor’s spelling was not altered. A discrepancy is that ‘samedi dernier’ was 22, and not 23, February.

Mr Mittelbach also mentions that the engraving was published on page 16 of The Times, 7 September 1926, in conjunction with, on page 10, a lengthy article marking the bicentenary of Philidor’s birth.

That material reinforces our criticism of Charles Michael Carroll for writing on page 141 of Pour Philidor (Koblenz, 1994):

‘... during the first half of the twentieth century, Philidor was not a well-known figure in history. As far as I can determine, the 200th anniversary of his birth in 1926 went by totally unnoticed ...’

On page 8 of the Winter 1995 issue of Kingpin (see too page 280 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and Chess Jottings) we quoted Carroll’s remark and commented:

‘To give just one straightforward refutation of that, the October 1926 BCM had a two-page article on Philidor by John Keeble whose first sentence referred to the bicentennial.’

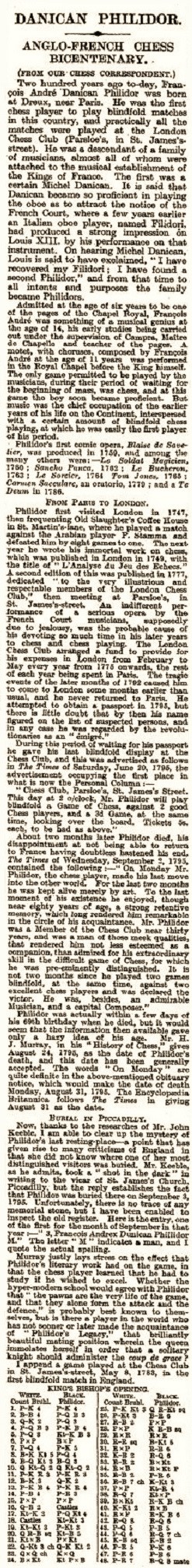

The 1926 Times article was headed:

‘Danican Philidor

Anglo-French Chess Bicentenary

(From our chess correspondent.)’

The newspaper’s chess correspondent was Edward Samuel Tinsley.

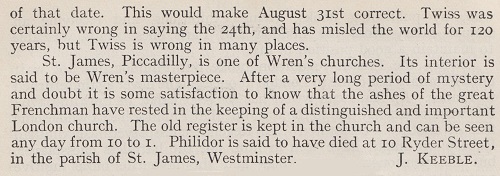

The Times article is relevant to the discussion about the date of Philidor’s death (C.N. 10046). E.S. Tinsley wrote:

John Keeble referred to that passage at the end of his above-mentioned article published on pages 434-436 of the October 1926 BCM:

The latest word on Philidor’s resting place is the article referred to in C.N. 10046, ‘Sleuthing for Philidor’s Grave’ by Gordon Cadden on pages 357-362 of the June 2016 BCM.

On 29 July 2016 Olimpiu G. Urcan wrote to us:

‘In today’s Times, page 19 of the second section, Raymond Keene writes:

“Gordon Cadden’s historical research in the June issue of the British Chess Magazine (see yesterday’s column) performs a further service by correctly establishing not just the correct location of François-André Philidor’s grave but also the accurate time of his death, which had previously been mis-stated as August 24, 1795. In fact, it was August 31 of that year.”

In reality, it has long been common knowledge that Philidor died on 31 August; C.N. 6005 pointed out that “there was doubt about the correct date until the mid-1920s”. George Cadden’s article on pages 357-362 of the June 2016 BCM, an interesting read, made no claim to have discovered anything new about the date.

(10046)

Manfred Mittelbach (Cape Town) notes the discussion on pages 77-79 of a book mentioned in C.N. 6868, François André Danican Philidor La culture échiquéenne en France et en Angleterre au XVIIIe siècle by Sergio Boffa (Olomouc, 2010).

Our correspondent wonders whether the picture of Philidor’s blindfold display was published in any chess book prior to A Century of British Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1934). It appeared there opposite page 22 with the acknowledgement ‘From an engraving, by kind permission of the City of London Chess Club’.

(10070)

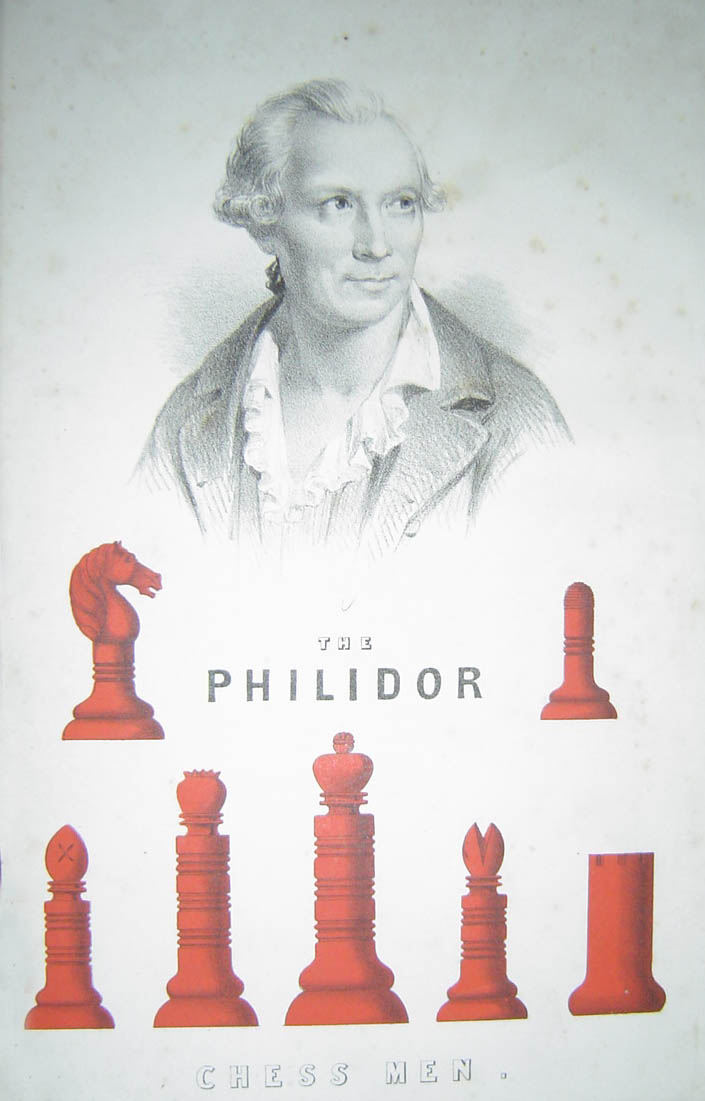

Philidor chessmen

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) sends us an advertising sheet (‘M. & N. Hanhart IMPT’) which he found in a copy of the Chess Player’s Chronicle. The portrait of Philidor is well known, but can a reader provide details about ‘the Philidor chess men’?

(3446)

Information is still being sought about the ‘Philidor chess men’ illustration in C.N. 3446. Our only progress so far is to note that it was included between pages 160 and 161 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1850.

(3591)

Frank Camaratta (Toney, AL, USA) writes:

‘The Philidor chess men were registered in 1850 in the UK and manufactured by George Merrifield. The advertisement for them ran for around six months in a London publication. Staunton ridiculed the design, and that did not help the popularity of the chessmen. They never took hold and had a production run of about a year. I own one full set and one incomplete set. As far as I can determine, they were offered in boxwood/ebony as well as ivory and in two sizes, a 10 cm king and an 11 cm king.’

Our correspondent has provided the following illustration from his collection:

(3652)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘I have looked up the “representation” of the design in the National Archives (BT 43/57, page 135). The design was registered with the Board of Trade under the Ornamental Design Act of 1842. An illustration of the design, approximately five inches by five inches, has been mounted in the record book. It carries the registration number 69599 and the words “THE PHILIDOR CHESS MEN”, with the pieces printed in red. In most respects it is the same as the illustration in C.N. 3446, but it has no portrait of Philidor.

At the bottom is printed “M. & N. HANHART IMPT.”. The Post Office London Directory for 1851 (page 774) shows that Hanhart, Michael & N., were lithographic printers, draughtsmen, and printers in colours, at 64 Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square.

Unfortunately, the appropriate register for Class 2 (Wood) designs (BT 44/6) does not begin until 13 January 1851 (registration number 75737), the early pages being deficient. The “representation” submission is not dated, but it seems safe to conclude that it was made after 8 February 1850 (the date of registration number 67245) but before 13 January 1851 (the date of registration number 75737).

My search has not identified the owner of the design. During 1851 Sarah Ann Graydon registered three chessmen designs, registration numbers 76039, 76317 and 76779 (see BT 44/6 and BT 44/8). The earliest of her addresses in the register (BT 44/8), 32 Store Street, is only about 300 yards from the premises of the printers of the Philidor design at 64 Charlotte Street. Some brief observations about her appeared on page 109 of my book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.’

(7757)

Also from John Townsend:

‘C.N. 7757 contained information about registration of the design of “The Philidor Chess Men” for Class 2 (wood). The same design was also registered in Class 13 (lace), its registration particulars having survived in a document, BT 44/31, at the National Archives. This shows that design number 69559 was deposited on 29 May 1850, the proprietor being “Revd. John Hales Sweet” of “Prince of Wales’s Road, Kentish New Town”. The “Subject of Design” is entered as “The Philidor Chessmen Class II & XIII”.

Another document, BT 43/421, contains a representation of the Class 13 design which is very similar to the illustration in C.N. 7757, but without the portrait of Philidor.

According to John Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses (volume 6, page 94), John Hales Sweet was born on 9 January 1819, the eldest son of William Sweet, a nurseryman, of Clifton, Gloucestershire, and his wife, Mary Ann. He matriculated at Wadham College, Oxford on 1 June 1837 and obtained his B.A. at St John’s, Cambridge in 1844. He was ordained deacon at Ripon on 17 December 1843 and served as curate at Hunslet from 1843 to 1846. Venn also notes that he lived without cure at Pinner, 1859-67, and at Southampton, before becoming rector of Kilmacow, County Kilkenny, 1872-80. He died on 31 May 1880.

The 1851 census (National Archives, HO 107 1498, f. 626) records him as a “Proprietor of Land & Houses”, but the London Gazette of 20 January 1854 (page 195) noted the bankruptcy of John Hales Sweet, seedsman, florist, dealer and chapman, of Tunbridge Wells, Kent. His debt problems persisted. In 1861 he was sued for debt by a tradesman in the Southampton County Court, and the judge ordered him to be committed for 21 days, but with the sentence suspended for seven days (Hampshire Advertiser, 2 February 1861, page 6).

In C.N. 5844 Michael Clapham referred to Sweet’s chess column in the American Chronicle. He had several children, one of whom, Mary Ann Ethel, married Harry Smith, of Montreal, Canada, in 1880.’

(8698)

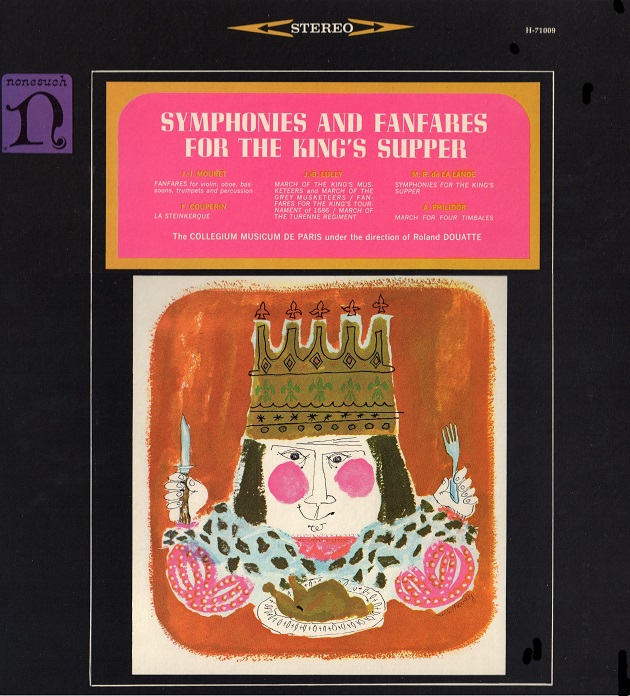

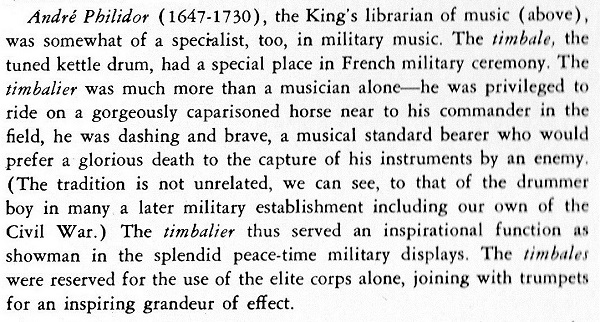

Music

Myron Samsin (Winnipeg, Canada) owns an LP record featuring music composed by André Danican Philidor (1652-1730), the chess master’s father (known as Philidor l’aîné and Philidor le père):

The reverse of the record sleeve has the following note (with an incorrect year of birth for the composer):

For information about la dynastie des Philidor two particularly detailed books are François André Danican Philidor. La culture échiquéenne en France et en Angleterre au XVIIIe siècle by Sergio Boffa (Olomouc, 2010) and Les Philidor by Nicolas Dupont-Danican Philidor (Bourg-la-Reine, 1997).

(10701)

What is the original source of the Polish draughts positions involving Philidor which The Philidorian occasionally published?

(1491)

Rob Verhoeven of the chess library in The Hague writes:

‘I have asked our specialist on draughts, Mr K.W. Kruijswijk, about Philidor’s positions. They are all from Recueil de coups de dames et fins de parties difficiles, published by M(onsieur) Dufour, Paris, chez Everat, 1807:

The Philidorian: page 68, no. 6 – Dufour: no. 86

The Philidorian: page 136, no. 13 – Dufour: no. 43

The Philidorian: page 136, no. 14 – Dufour: no. 229

The Philidorian: page 137, no. 15 – Dufour: no. 274

The Philidorian: page 137, no. 16 – Dufour: no. 322.’

(1566)

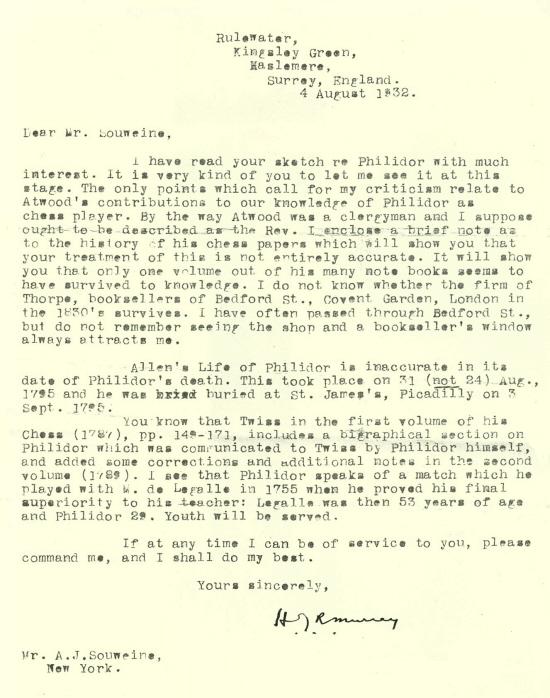

Death

Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) has sent us a copy of a letter dated 4 August 1932 from H.J.R. Murray to A.J. Souweine:

(6000)

Michael Clapham comments that although H.J.R. Murray’s letter, written on 4 August 1932, stated that Philidor died on 31, and not 24, August 1795, page 865 of his History of Chess (Oxford, 1913) gave 24 August.

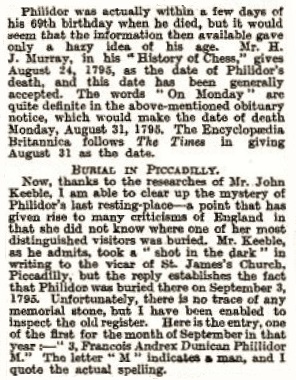

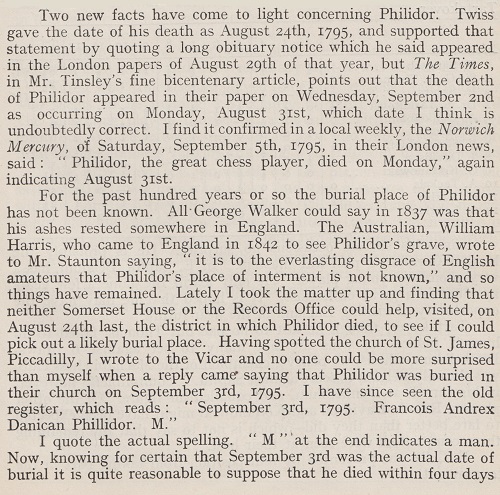

We note that there was doubt about the correct date until the mid-1920s. On page 435 of the October 1926 BCM John Keeble wrote:

‘Two new facts have come to light concerning Philidor. Twiss gave the date of his death as 24 August 1795 and supported that statement by quoting a long obituary notice which he said appeared in the London papers of 29 August of that year, but The Times, in Mr Tinsley’s fine bicentenary article, points out that the death of Philidor appeared in their paper on Wednesday, 2 September as occurring on Monday, 31 August, which date I think is undoubtedly correct. I find it confirmed in a local weekly; the Norwich Mercury, of Saturday, 5 September 1795, in their London news, said: “Philidor, the great chessplayer, died on Monday”, again indicating 31 August.’

(6005)

The full text of the Times article, 7 September 1926, page 10, which was mentioned above:

The engraving on page 16:

Further to John Keeble’s above-mentioned article on pages 436-438 of the October 1926 BCM, G.H. Diggle contributed the following letter on page 688 of the November 1926 issue:

‘The frontispiece of Le Palamède for 1843 consists of a portrait of Philidor under which is written: “Philidor ... Né à Dreux, le 7 septembre 1726, Mort à Londres, le 29 août 1795”.

In the Chess Player’s Chronicle (1840, volume I, page 284), however, Staunton, in answer to “F.M.G.” (a correspondent), definitely states: “Philidor died on 31 August 1795.” This of course confirms Mr Keeble’s version.’

Page 727 of the December 1926 BCM carried a further letter from G.H. Diggle:

‘With reference to my letter concerning Philidor which was published in your last number, it has been pointed out to me very justly that what I alluded to as “Mr Keeble’s version” of the date of Philidor’s death is in fact “The Times’ version” (given in their article on 7 September last, and accepted by Mr Keeble as the correct date). I much regret any injustice to The Times that my letter may have done.’

Immediately afterwards there was a letter from John Keeble:

‘I regret having given a wrong date for the birth of Philidor in my article in October BCM. 7 September 1726, as mentioned by your correspondent, Mr G.H. Diggle, is the right day. It is important to correct this as at some future time a tablet to the memory of Philidor will be placed in St James’ Church.

It is interesting to find that Mr Staunton knew the correct date of Philidor’s death, and so stated it on page 284, Vol I, of the CPC. That particular number of the magazine was dated 28 August 1841. In the same volume (page 185) Mr Staunton stated that a portrait of Philidor by Gainsborough was in existence and said to be in the possession of a Mr Halford. I wonder where it is now.’

Writing to us on 3 September 1992, G.H. Diggle mentioned what lay behind his second letter:

‘I remember writing my first historical letter in the BCM, in 1926, and E.S. Tinsley promptly “sat on me” in a private letter from The Times.’

From John Townsend:

‘Contemporary newspaper reports of the death of Philidor acknowledged the assistance he received from an “old and worthy friend”. There were variations in the words used, but the following statement from the Kentish Weekly Post of 4 September 1795 was typical:

“For the last two months he was kept alive merely by art, and the kind attention of an old and worthy friend.”

George Allen discussed briefly the identity of the “old and worthy friend” on page 109 of The Life of Philidor, Musician and Chess-player (Philadelphia, 1863), but without arriving at a convincing answer:

“In a letter received after the preceding sheet had been printed, Mr Lewis (the eminent English Chess-author and player) kindly answered some inquiries of mine, by saying: ‘Who “the old and worthy friend” was, I know not. I always understood from Sarratt that a Mr Crawford, a very rich man, patronised Philidor, taking a lesson – or being supposed to take a lesson – daily, and giving him carte blanche to dinner, whenever it suited him.’”

A more telling remark, not mentioned by Allen, had previously been made by George Walker in the “To Correspondents” column on page 2 of Bell’s Life in London of 15 November 1840:

“Sir A. Carlisle, just dead, was a staunch friend of Philidor’s, when the latter was on his death bed.”

The expression “kept alive merely by art” suggests skilful medical attention. Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) was a prominent surgeon. The Dictionary of National Biography notes that in 1793 he was appointed Surgeon at Westminster Hospital, where he continued to work for the rest of his life, being knighted in 1820. His death in Langham Place, London, was reported on page 3 of the Morning Post of 6 November 1840, and he was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery on 10 November.

Carlisle was a long-term resident of Soho Square, and George Walker and his father had lived at 17 Soho Square. A brief examination of rates assessments and land tax returns shows that they were both in Soho Square during the years 1819 to 1821, so it is possible that the Walkers knew Carlisle.

On page 127 of his Chess & Chess-Players (London, 1850) George Walker blamed “the mighty and the rich” for the poverty of Philidor’s last days:

“Alas ! for England ! the mighty and the rich suffered Philidor to die, if not in actual need of life’s necessities, at least without those comforts which gold can supply, to soothe down the harsh asperities of utter destitution! Philidor died almost literally in a garret. During his last hours, he was chiefly indebted for support to the assiduities of one kind friend …”

Walker says nothing here of Anthony Carlisle’s involvement. Although Walker’s main thrust above concerned Philidor’s poverty, it is perhaps worth reflecting that he could not have mentioned that Philidor was attended by a surgeon who later became eminent without detracting from his argument.

Walker’s final sentence tends to suggest that support came from one person alone. That is reinforced by a remark by George Allen on page 44 of The Life of Philidor: Musician and Chess-Player (Philadelphia, 1858):

“When among Englishmen were the sick-bed wants of a stranger, even less beloved than Philidor, known and ministered to by one friend and by one friend alone?”

On pages 42-43 of the same book George Allen countered Walker’s accusation by pointing out that ...

“... ‘the garret of Philidor’ (which was no garret) is not pretended to have been any other than such modest apartment as he had chosen to occupy through the whole of his last residence in London. There was not, therefore, the same reason for removing Philidor, during his sickness, as existed in the case of poor La Bourdonnais.”

Philidor’s “modest apartment” was in Little Ryder Street, which was a very short walk from the chess club at Parsloe’s on St James’s Street. Letters presented by Marcelle Benoît in Philidor, musicien et joueur d’échecs (Paris, 1995) suggest that his last known residence was at 10 Little Ryder Street. However, in the Chess Stalker Quarterly, June 2012, in an article entitled “Sleuthing for Philidor’s Grave”, Gordon Cadden reported on page 9 that he had found Philidor’s address entered as 8 Little Ryder Street in a burial ledger for St James’s Chapel of Ease, Hampstead Road.

In 1795, rate books for Little Ryder Street did not show house numbers, which makes it harder to identify the principal occupiers, who are assumed to include Philidor’s landlord. Both 8 and 10 were on the south side of Little Ryder Street, the occupiers of which were listed in an assessment for the Poor Rate (Collector’s Book), dated 18 April 1795 (Pall Mall Ward, parish of St James’s Westminster, Westminster Archives, D116, ff. 35-36). The entry below has been abbreviated:

Little Ryder Street South

Alexander Oswald 20

Thos Williams 24

Wm Fry 22

Wm King 14

Elizth Alexander 22

Chas Wadlow 15

Clement Baker 10

Raymond Baux 16.The figures represent the gross annual rentable values of the properties in pounds. Insurance records of Sun Fire Office, held at London Metropolitan Archives, indicate that on 30 December 1791 Elizabeth and Janet Alexander, of “10 Little Rider Street”, milliners, were insured. That seems to identify “Elizth Alexander” in the above list as the occupier of No. 10. A similar insurance record, dated 25 November 1796, names Thomas Williams, gentleman, of “8 Little Rider Street” as the insured, while in a Westminster coroner’s jury, on 13 August 1794, Thos. Williams, of Little Ryder Street, was described as a haberdasher. Another insurance record, dated 26 March 1799, associates William Fry, gentleman, with the address “9 Little Rider Street”, his wife a trimming maker; and another, dated 19 November 1791, gives Fry’s address as “Little Rider Street”, his wife a mantua and trimming maker. It is clear that in the above Poor Rate list the occupiers of the south side of Little Ryder Street appear in ascending order starting with 7. The only entry which remains in doubt is the one for “Wm King”, who could have occupied either part of No. 9 or part of No. 10.

From this it seems that Philidor resided “through the whole of his last residence in London” either at 10 Little Ryder Street with Elizabeth Alexander, a milliner (or possibly with William King), or at No. 8 with Thomas Williams. A milliner or a haberdasher might easily have taken on a lodger, as did John Maynard, a bookseller, who had Carmine Verdone lodging with him, as was reported in C.N. 9595.

Finally, in the same column on page 2 of Bell’s Life in London of 15 November 1840 the following interesting exchange with a different correspondent was inserted:

“EZ – Are there any chess players living who have played with Philidor? – Yes: Sir Griffin Wilson, and Sir W. Alexander, and doubtless many others. It is 45 years since Philidor’s death.”

Sir William Alexander (1755-1842), of Airdrie, was Chief Baron of the Exchequer at Westminster. A few weeks later, in the same newspaper, dated 13 December 1840, he was reported as having contributed five pounds to the De La Bourdonnais fund in a list of donors printed on page 1. His will was proved on 21 July 1842 in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PROB 11/1965/15).’

(9759)

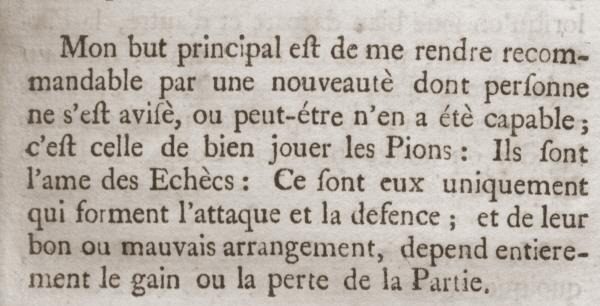

See also Philidor: ‘Pawns are the soul of chess’.

Addition from John Townsend on 10 May 2023:

‘At least one illegitimate child of Philidor was baptized in Westminster, as can be seen from the following baptism entry, dated 18 February 1753, in the parish register of St Anne’s, Soho:

“Andrew-Marix Philidor Son of Andrew and Ellen.”

Included in the left-hand margin is the child’s date of birth; at that point, the writing is faded, so that only the month, January, and the first of two digits of the day, 2, can easily be read. (The date of birth was, therefore, between 20 and 29 January 1753.)

The anglicized form of André, Andrew, was used here for the father’s (i.e. the chessplayer’s) name, and the child was given the names Andrew-Marix. Marix is a rare name in England. For example, the General Register Office’s indexes of births, marriages and deaths record just a few instances of its having been used; more commonly as a surname, but also as a forename. Nothing else is known about either the child or the mother, though there seems to be some scope for further research.

George Allen, on page 34 of The Life of Philidor, Musician and Chess-player (Philadelphia, 1863), raises the matter of Philidor’s having taken with him to Potsdam in 1751 a woman whom the mathematician Euler referred to as eine Maitresse. To avoid any misunderstanding, Allen quoted Euler’s original German:

“Er soll noch ein sehr junger Mann sein, führte aber eine Maitresse mit sich, wegen welcher er mit einigen Officieren in Potsdam Verdriesslichkeiten bekommen, welche ihn genöthiget unvermuthet wegzureisen.”

Allen notes (on page 36) that, after returning eventually to England, Philidor stayed there “until near the close of the year 1754”, and returned to Paris in November (page 39) “after an absence of nine years”. He remained a bachelor until 13 February 1760, when he was married in Paris to Angélique-Henriette-Elisabeth Richer (Allen, page 53).’

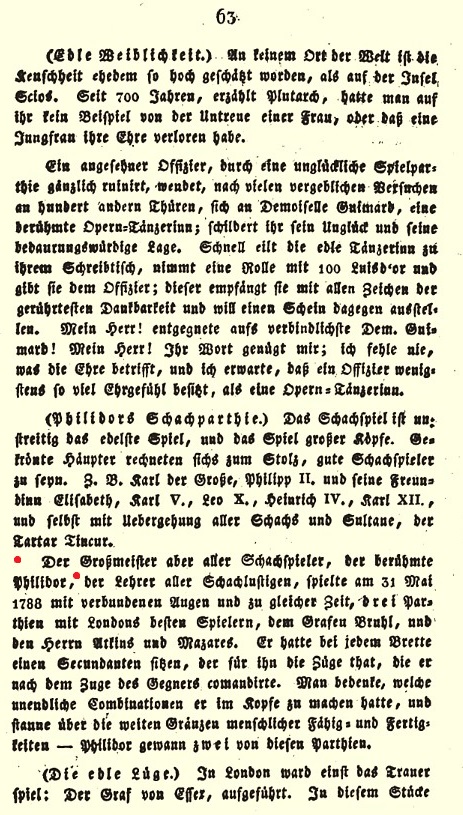

On the subject of early usage of the term ‘grandmaster’, or equivalents in other languages, Nick Pope (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) sends the following in relation to Philidor from page 63 of volume three of Lesefrüchte, belehrenden und unterhaltenden Inhalts (Munich, 1828):

(11967)

John Townsend writes:

‘Page 23 of William Hartston’s The Kings of Chess (London, 1985) contains an example of an announced mate by Philidor. The occasion was an odds game with Count Brühl at Parsloe’s in London on 26 January 1789. White was in check, “and Philidor announced mate in two moves: 28 Qxf5! and 29 Rh8 mate”.

George Walker’s A Selection of Games at Chess, actually played by Philidor and his contemporaries (London, 1835) includes the game on pages 41-42 with the following termination:

“27 K. Kt. P. on. Kt. to K. B. fourth, ch. 28 Q takes Kt., and Mates next move with R.”

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games by Levy and O’Connell (Oxford, 1981) has the score (page 15) as concluding with “27 g5 Nf5+ 1-0” and gives the source as “MS H.J. Murray 64, Bodleian Oxford, ‘Collection of European Games’”.’

See also Announced Mates.

(12014)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.