Edward Winter

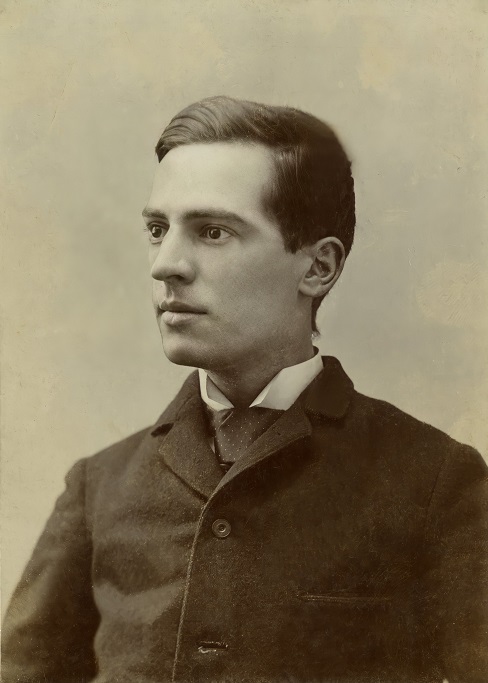

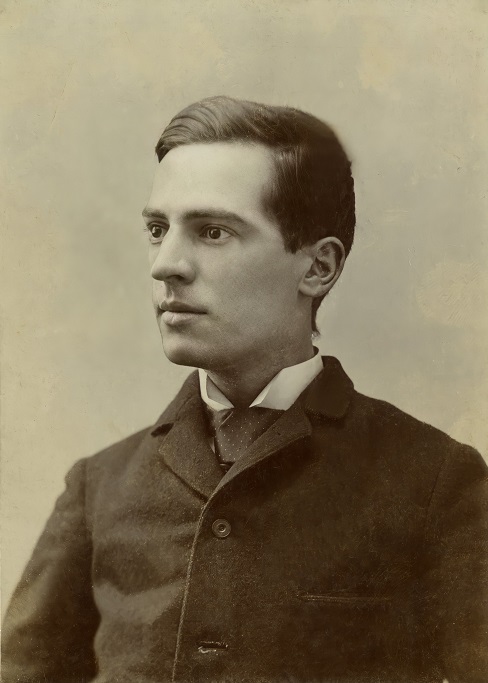

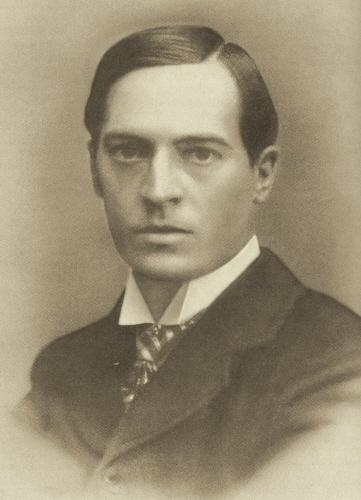

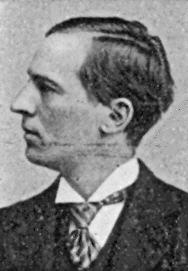

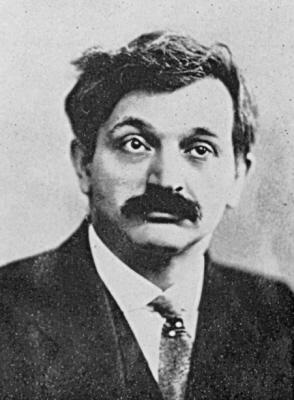

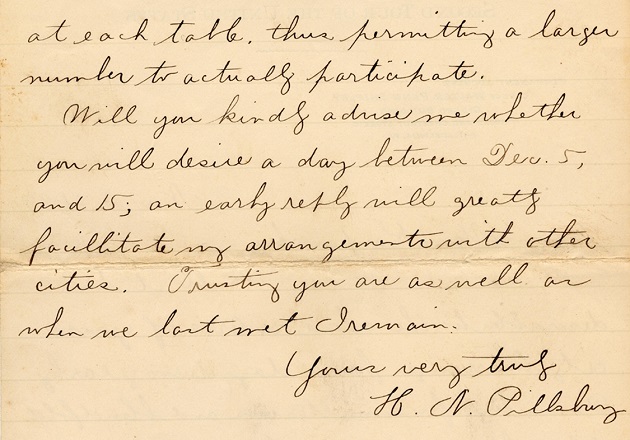

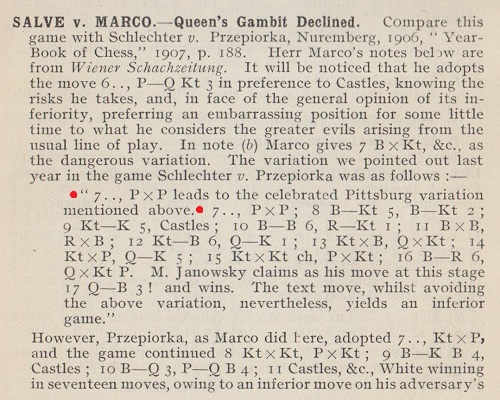

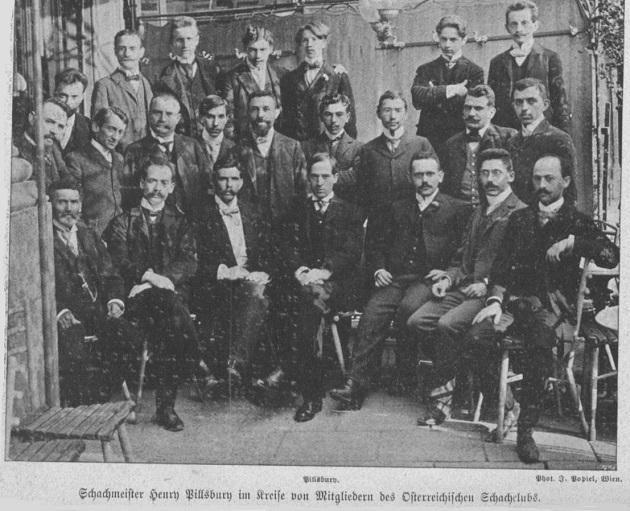

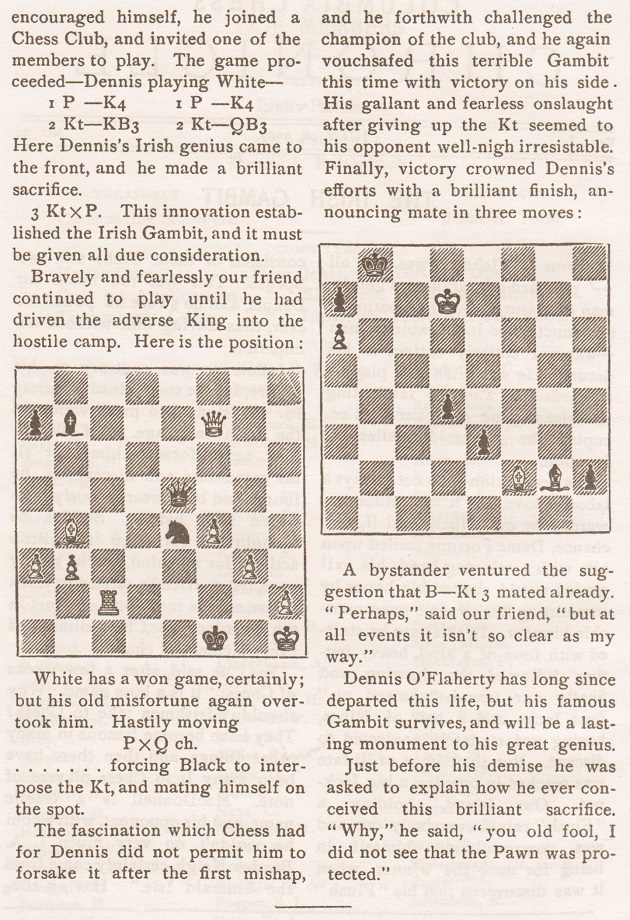

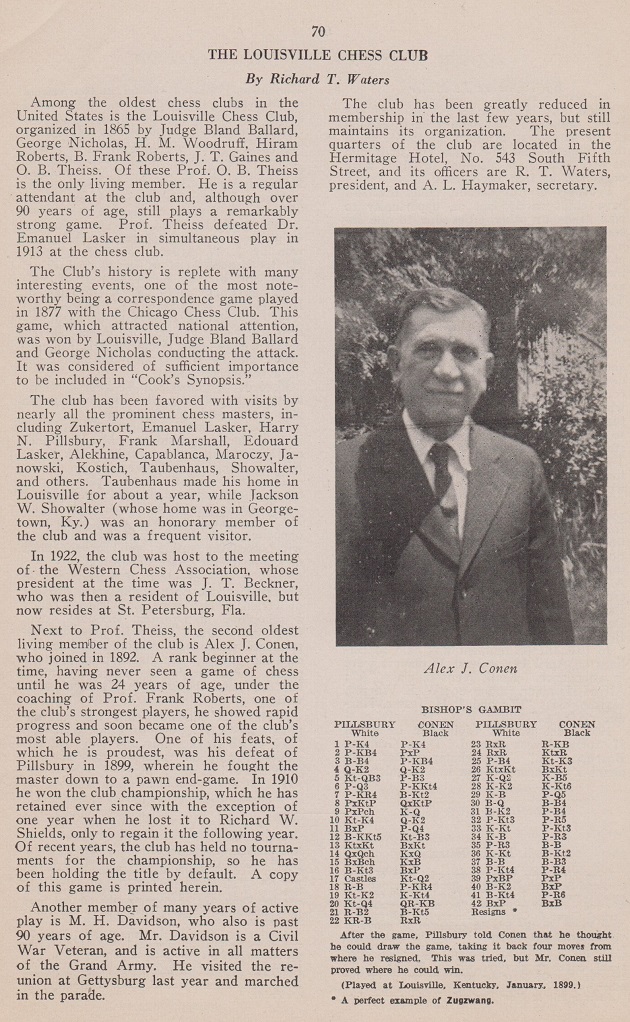

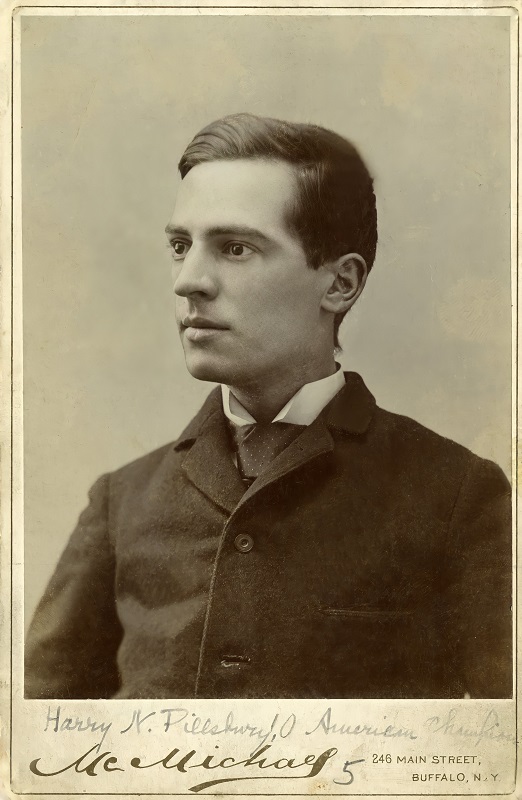

H.N. Pillsbury (1872-1906)

Our feature article Pillsbury’s Torment, written in 2002 and occasionally updated, discusses the final year of his short life. The present article, first posted on 18 October 2021, draws together other C.N. material about the American master.

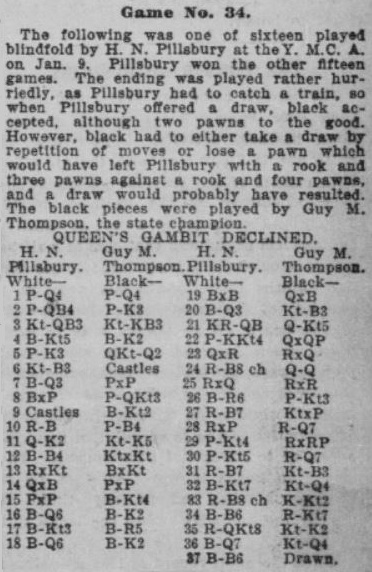

****

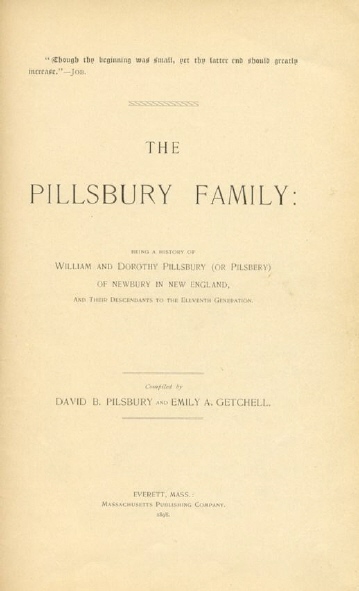

Around 1640-41, during the reign of Charles I of England, a young man named William left his native land for the New World. Settling in Boston, he took employment as a servant and soon began ‘his courtship of a comely serving maiden’, Dorothy Crosbey. They were married in June or July 1641 and had, between 1642 and 1671, ten children, the third of whom was named Moses.

William, who lived until 1686, was the common ancestor of the Pillsbury family in, to use the modern term, the USA, and in the eighth generation there came Harry Nelson Pillsbury. The direct lineage was as follows.

1. William Pillsbury (died 19 June 1686)

2. Moses Pillsbury (born circa 1645; died 1701)

3. Caleb Pillsbury (born 27 July 1681; died 1759)

4. Caleb Pillsbury (born 26 January 1717; died 7 February 1778)

5. Caleb Pillsbury (born 27 March 1752; died 17 September 1832)

6. Caleb Pillsbury (born 17 December 1786; died 17 March 1874)

7. Luther B. Pillsbury (born 23 November 1832)

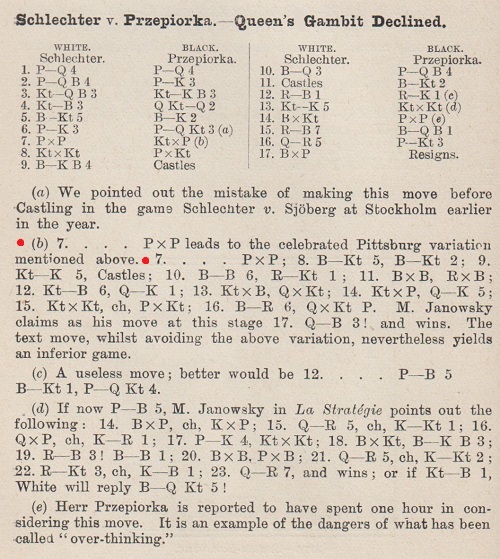

8. Harry N. Pillsbury (born 5 December 1872).

All the above details are taken from the remarkable book mentioned in C.N. 4380, The Pillsbury Family by David B. Pilsbury and Emily A. Getchell (Everett, 1898).

In addition to the information quoted in our earlier item, page 162 of the book states that Harry Nelson Pillsbury’s father, Luther, had a second marriage, to Mary A. Libby on 9 February 1895, and the entry contains the following note:

‘Mr Pillsbury was a graduate of Dartmouth College, and for a number of years taught school successfully in different towns of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Of late years has been engaged in real estate and insurance business, in Somerville. Mrs Pillsbury was a teacher before her marriage, and was a writer of pleasant verse for several publications. Harry, the youngest son, has won name and fame as a chessplayer in America and Europe.’

As regards ‘Nelson’ it may be mentioned that the chess master’s grandfather, Caleb, married Nancy Nelson in 1808. More information about Luther Pillsbury and his family is given at an ‘Historicleaves’ webpage, from which it will be noted that he died on 8 March 1905. Later that month Harry N. Pillsbury spent a grievous period in hospital, as described in our feature article Pillsbury’s Torment.

(4397)

Updated link concerning Luther Pillsbury.

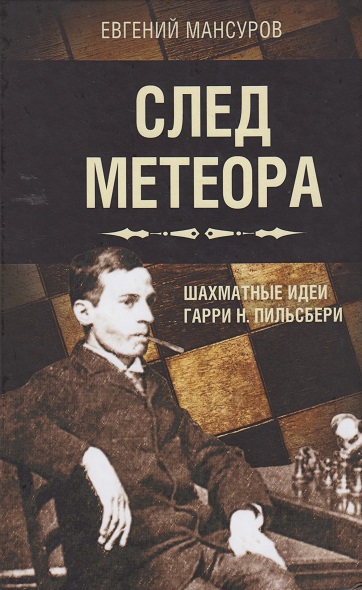

The following books about Pillsbury are in our collection, the first ten having been listed in C.N. 4104:

Acknowledgement: Eswara Kosaraju (San Diego, CA, USA).

C.N.’s references to new chess literature are largely confined nowadays to drawing attention to lesser-known publications. Our latest acquisition is Между Морфи и Фишером. Гарри Пильсбери by M. Sokolov (Moscow, 2020):

(11841)

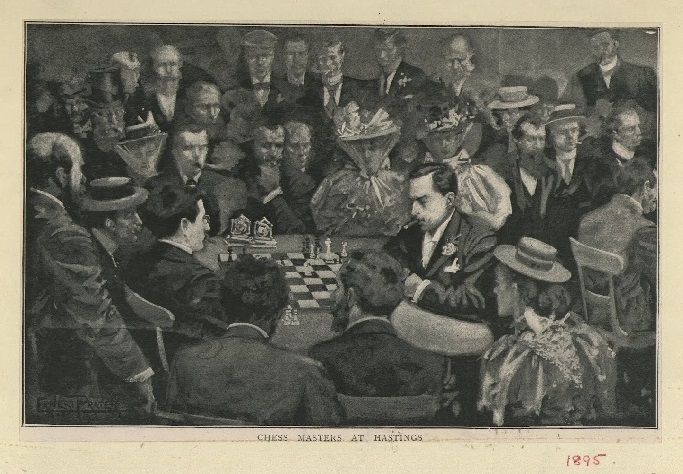

From Who Was Who in America 1897-1942 volume (page 974):

‘PILLSBURY ... won world’s championship at Hastings Internat. Chess Congress, Eng., Sept. 1795.’

(598)

Who was the first player to give a simultaneous exhibition at sea? According to page 296 of the 14 April 1936 issue of CHESS:

‘Did you know ... that the first simultaneous display on board ship was given by Dr Tartakower on the Massilia in the Mediterranean, 1931? Also he is the only person to have given a simultaneous exhibition in an aeroplane – between Budapest and Barcelona in 1929.’

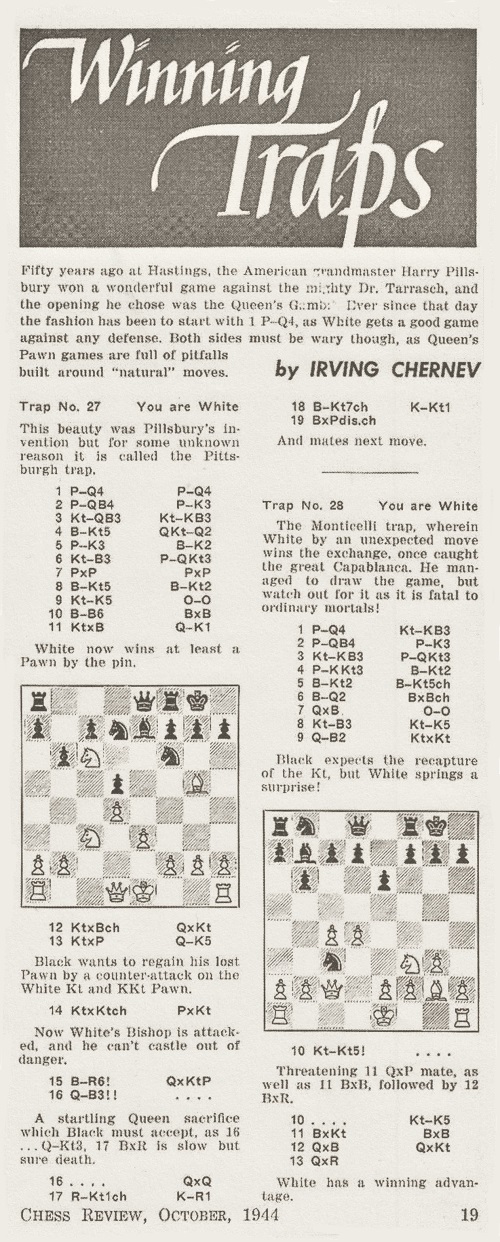

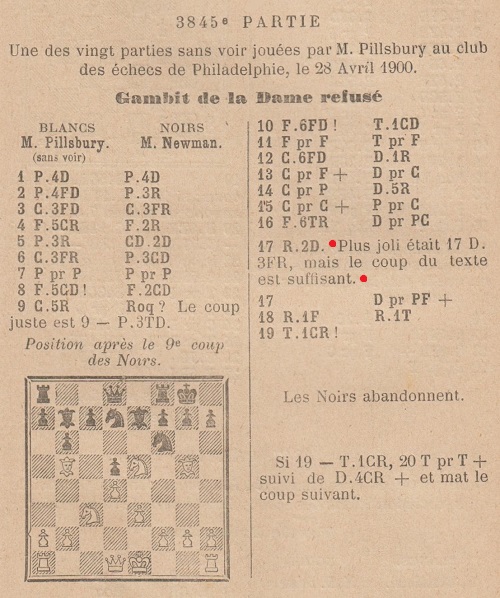

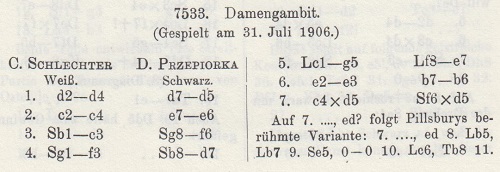

However, some years later (November, 1944, page 19) the same magazine quoted from the May-June 1944 Iowa Chess Correspondent the reminiscences of Norman W. Bingham, a boyhood friend of Pillsbury’s. The two crossed the Atlantic together in 1899:

‘... Pillsbury played a dozen blindfold simultaneous games against various passengers, winning them all handily. The tables were in the smoking room and Pillsbury sat with me on deck, talking about early school days. Stewards from the smoking room flitted back and forth with paper memoranda to communicate the moves from the various tables. I tried to get Harry to tell me how he did it, but he couldn’t; and I don’t believe he knew himself. He said he didn’t carry a picture of the various tables in his mind and he didn’t memorize the moves. He seemed to just know, when told what the move had been on one table, what he wanted to do. At any rate, if he was able to tell me how he did it, he successfully refrained ...’

Pages 356 and 373 of K. Landsberger’s 1993 book on Steinitz mention small displays by Steinitz during Atlantic crossings, in 1897 and 1898.

(1947)

On page 10 of the November 1992 Chess Life A. Soltis said that Pillsbury’s last published game was against Marshall in 1904. Not so. C.N. 1673 gave the score of Pillsbury v Edward Hymes, Philadelphia, May 1905, which had been printed in the New Orleans Times-Democrat of 18 June 1905 and the June 1905 American Chess Bulletin (page 226). Mr Soltis was therefore also wrong to suggest on page 50 of his 1990 book on Pillsbury, written with Ken Smith, that the Hymes game ‘has apparently been lost’.

(1954)

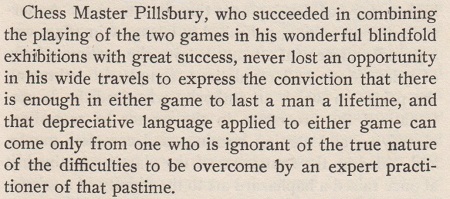

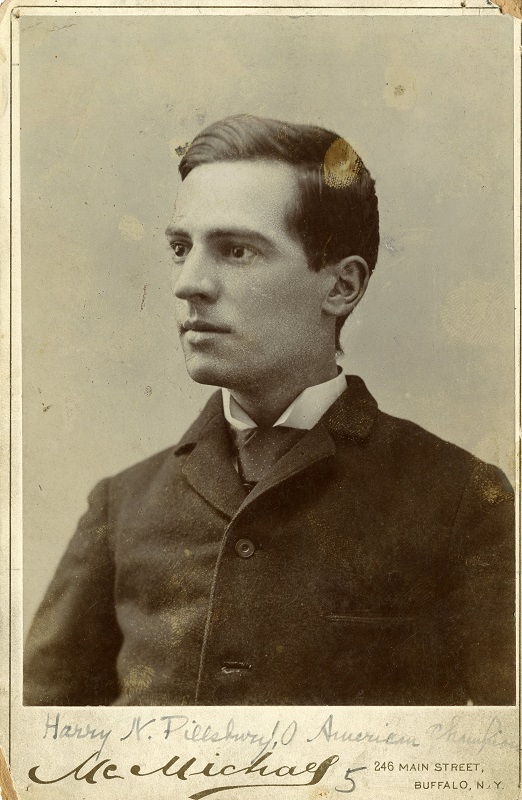

The American Chess Magazine, August 1899, page 75 quoted from the Washington Post H.N. Pillsbury’s explanation of his success in playing chess, checkers and whist simultaneously:

‘I don’t mind smoking interfering with my play. Some folks say it takes the sharp edge from one’s intellect, and spoils one’s memory. I haven’t found it so. I’ve smoked since I was 14, and I can play better when I have a cigar in my mouth – only a cigar, never anything else. When I play a lot of games at the same time, I must be keyed up to it, as it were. I practise what you call self-hypnotism. It is largely will-power. You see, it’s just this way. When it becomes my turn to make a move at one of the chess boards, my mental powers are concentrated severely on the one move. All the other chess boards, the checkers and whist are obliterated from my mind. It is as though I had never started playing those games at all. I seem to remember nothing of them. I come to a decision, the move is made, and I turn again to the cards in my hand. Quick as lightning the game of chess vanishes from my mind. Now it is nothing but whist with me. I seem never to have had a thought of anything but the game of cards. I play one. Then I move one of the checkers. These transitions of mind take place so quickly that I seem to be playing chess, checkers and whist all at once, and to be thinking of all the games at once. But it is as I explained. The only thing I really need for the ordeal is my cigar.’

(1985)

See too Chess and Tobacco.

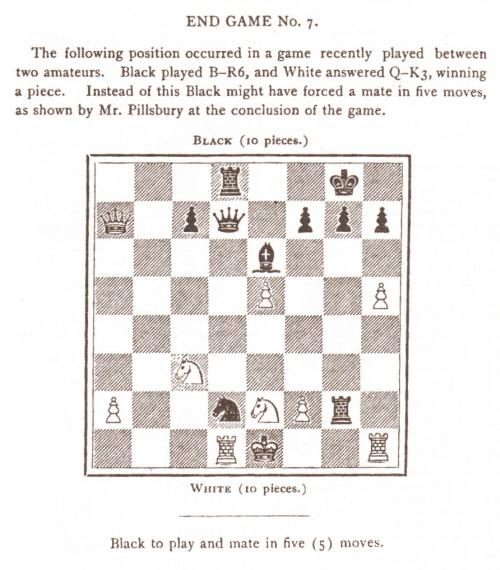

Missed Mates gives the game Kemeny v Pillsbury, Philadelphia, 30 October 1895, in which White overlooked a mate in one: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bd6 6 d4 Nf6 7 O-O O-O 8 Nbd2 Qe7 9 Bd3 Ne8 10 Nc4 f6 11 Ne3 g6 12 Nd5 Qd8 13 Be3 Be7 14 Nd2 d6 15 f4 Ng7 16 f5 g5 17 h4 gxh4 18 Qg4 Kh8 19 Qxh4 Qd7 20 Kf2 Bd8 21 Rh1 Ne8 22 Rh3 Na5 23 Rah1 Rf7 24 Be2 Rg7 25 Bh5 Kg8 26 Bxe8 Qxe8 27 Qxh7+ Rxh7 28 Rxh7 Bxf5 29 exf5 Qf8 30 Rh8+ Kf7 31 R1h7+ Qg7 32 Bh6 Qxh7 33 Rxh7+ Kg8 34 Rg7+ Kh8 35 Ne4 Resigns.

A.B. Hodges on pages 90-91 of the May-June 1923 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Like other great masters, Pillsbury was hampered in the development of his chess talent by the fact that it was his only source of income and at his period there was not sufficient interest manifested in this country to guarantee a livelihood to a chess master. Therefore, it was a continual struggle for him to make both ends meet. Possessing a generous disposition and holding a just pride in his association with those more blessed with worldly goods, he never placed himself under the slightest obligation, though he lamented to me that the trophies won by him in tournaments and matches were one by one parted with for their intrinsic value to meet his actual necessities.’

(2304)

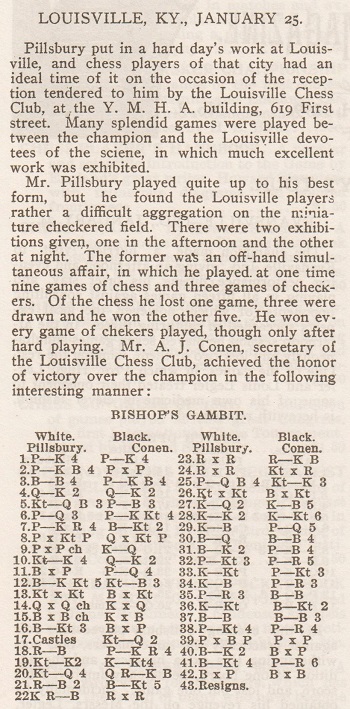

From John S. Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

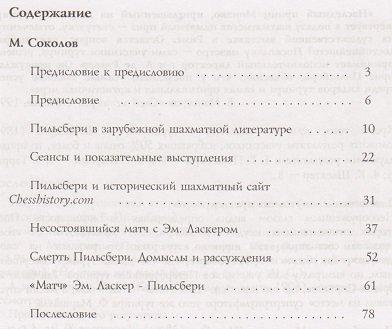

‘Elmer Ernest Southard (1876-1920) played chess for Harvard University for four years, participating in the annual Princeton-Harvard-Yale-Columbia Intercollegiate chess tournaments during 1895-1899. He annually dominated play in these events, finishing his college career with a record 22-2 result. Southard’s distinguished professional career was cut short on 8 February 1920, when he died of pneumonia at the age of 43. His son, Ordway Southard, continued the association with chess, publishing Leaves of Chess a journal of scaccography from January 1957 through 1961.

In researching Elmer Southard’s chess career, I obtained his obituary in the New York Times for 9 February 1920. There we learn that Southard was “a member of the St Botolph and Boston Chess Clubs, and noted as one of the foremost amateur chess players in America. Dr Southard was particularly interested in the case of Harry N. Pillsbury, the former American champion chessplayer, who in the later years of his life lost his mind. Dr Southard made an examination and study of the brain of Pillsbury in an attempt to decide the mooted question of whether a genius for chess tends to deteriorate the mind.”

Had Dr Southard been a Freudian psychoanalyst, his examination of Pillsbury’s “brain” might well be written off as poor word choice by the Times writer responsible for the obituary. At the time of his death, though, he happened to be Bullard Professor of Neuropathology at Harvard Medical School, as well as pathologist to the Massachusetts Commission on Mental Diseases and a Director of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Institution. It appears that Pillsbury’s brain may actually have been in his hands.

Does anyone know if Dr Southard’s study of Pillsbury’s brain has survived, perhaps in the vast depths of Harvard’s libraries? Has anyone else seen Pillsbury’s brain?’

(2405)

Neurosyphilis is a 496-page compendium of case histories. Page 17 states, ‘The names assigned to the cases are fictitious and chosen to suggest race or descent’, and we saw no biographical details corresponding to Pillsbury’s.

(6351)

For other references to E.E. Southard, see the Factfinder.

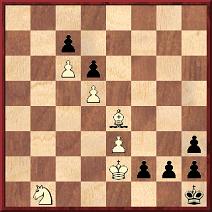

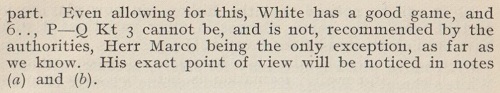

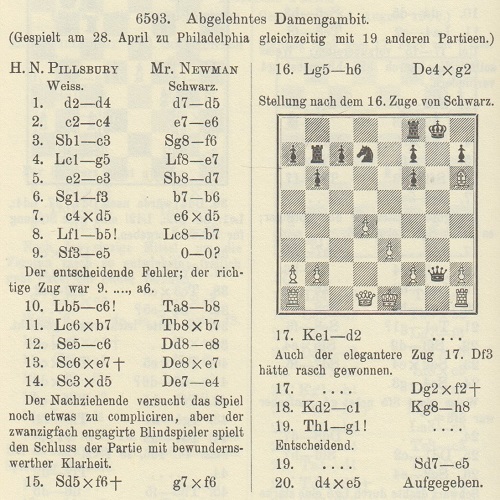

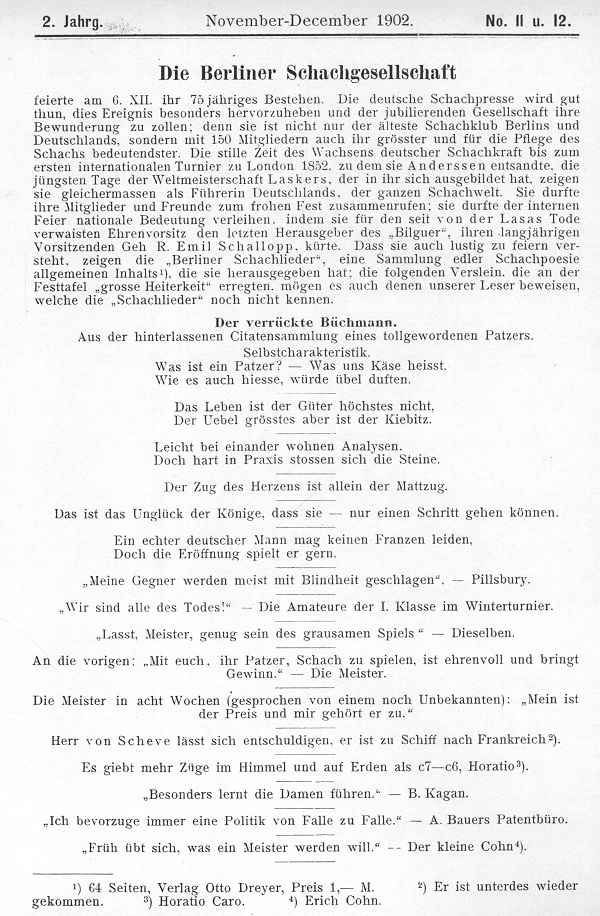

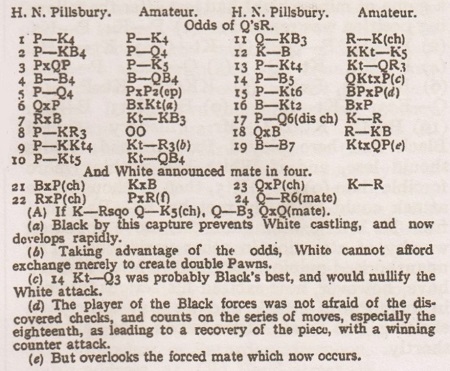

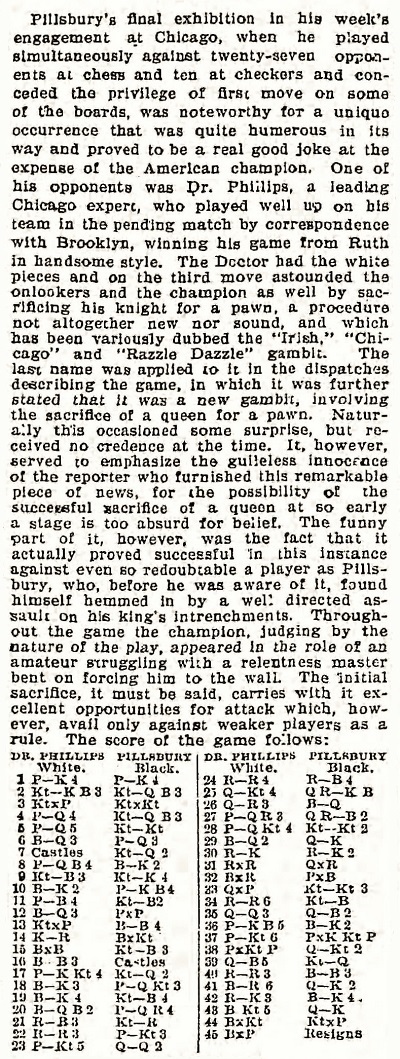

From page 49 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 7 February 1904 comes the conclusion of a ‘recent’ simultaneous game in Brooklyn between H.N. Pillsbury (White) and C. Jaffe:

Black to move

1...f3 2 Qd2 Qc6 3 Qc2 f2 4 Qe2 Qc1+ 5 Ka2 f1(Q)

6 Qf3+ Qc6 7 Qxf1 g2 8 Qf2 Qg6 9 Qg1 Qg4 10 Kb2 Qe2+ 11 Ka3 Qf1 12 Qxg2+ Qxg2 Stalemate.

(2791)

We seek further particulars about this endgame, between Pillsbury and Shinkman, which was published on page 116 of Checkmate, July 1901:

‘In the above position White having the move played 1 c5 b5 2 axb5 cxb5 3 c6 Kd6 4 c7 Kxc7. Here White thought he saw a win, and continued with 5 Kc5 a4 6 Kxb5, but Black replied 6…a3! compelling 7 bxa3, and the game was drawn.’

(2851)

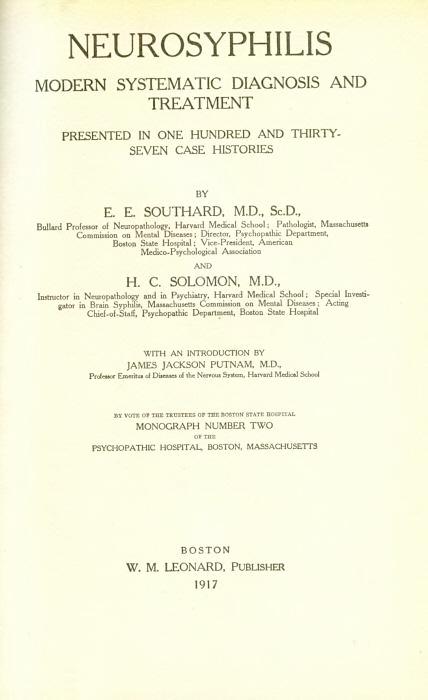

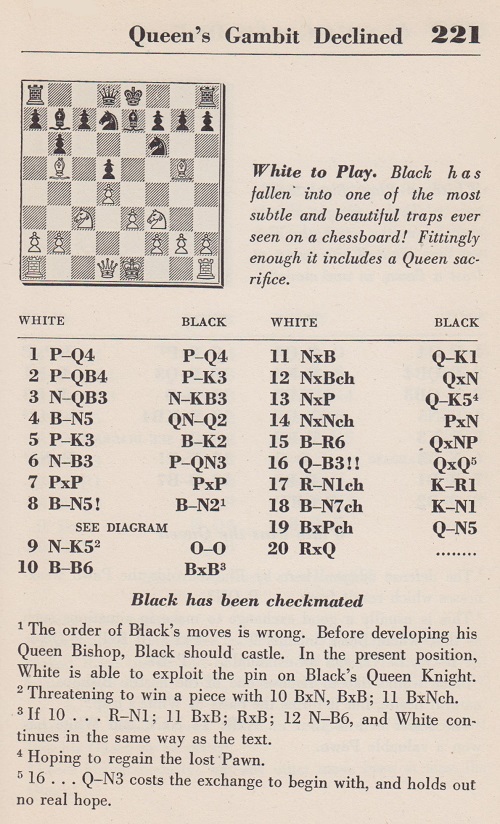

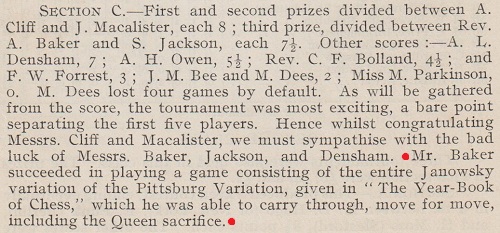

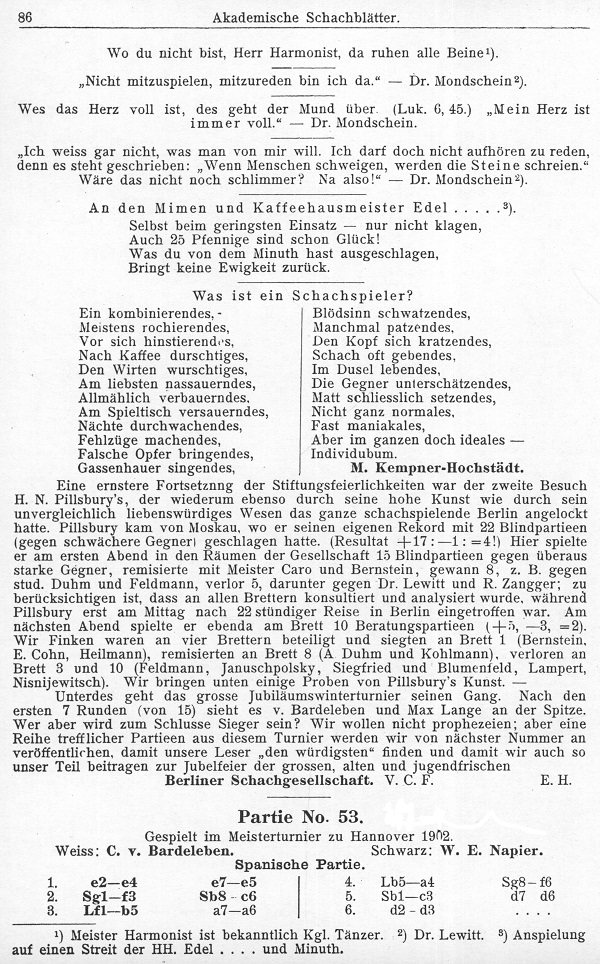

The famous win by Pillsbury (Black):

White to move

1 Qh4 Qf7 2 Bxe4 Qf1+ 3 Bg1 Qf3+ 4 Bxf3 Bxf3 mate.

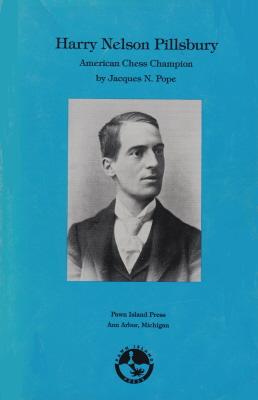

Only these concluding moves are on hand, but in the hope of stimulating further probing we summarize here the current state of knowledge/ignorance concerning this game. No precise information is available on the opponent’s name, the date or the venue. Page 115 of Queen Sacrifice by I. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1991) stated that it was played in a blindfold simultaneous display. Page 73 of Blunders and Brilliancies by I. Mullen and M. Moss (Oxford, 1990) claimed that it occurred in a simultaneous exhibition in the United States in 1902, whereas page 253 of Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996) reported that the occasion was a knight odds game in 1899 and that the position appeared in the Literary Digest of 25 November 1899.

It seems that chess periodicals of the time were inattentive to Pillsbury’s unique combination. Indeed, the first instance we have found so far of the position being given star billing in a chess magazine comes after Pillsbury’s death, i.e. on page 16 of the January 1907 BCM:

‘Mr W.E. Napier recently gave in his column in the Pittsburgh Dispatch (USA) the following diagram which illustrates Pillsbury’s pet position. The play is so piquant and the finale so charming that we are not surprised to learn that the position was a favourite with Mr Pillsbury. We have, of course, seen text-book examples of mate with a single bishop, but we do not recollect having before met with a specimen from actual play. Mr Napier says:

“There was nothing on the chessboard that used to amuse Pillsbury so much as the appended position which occurred in one of his simultaneous exhibitions. I have seen him show it repeatedly, with infinite relish for its humour. It is the sort of hair-breadth escape that he, as, indeed, all master players, would contrive in exhibition play. He chuckled more over this situation than anything he ever ‘brought off’, and was always fond of talking about the career of his ‘lone bishop’.”’

If the position arose shortly before its appearance in the Literary Digest of 25 November 1899 this suggests a game from Pillsbury’s tour of the United States that autumn. In case readers suitably placed can undertake research in the local newspapers, we therefore give below the dates of Pillsbury’s displays during the first part of that tour, as gleaned from the final two issues of the American Chess Magazine, October-November 1899 (pages 158-160) and December 1899 (pages 233-235):

October (exact dates?): Philadelphia, PA

20 October: Bridgeport, CT

21 October: Brooklyn, NY

23 October: Somerville, MA

26 October: Winooski, VT

27 October: Springfield, MA

30 October: Providence, RI

4 November: Bayonne, NJ

9 November: Philadelphia, PA

13 November: Washington, DC.

(2910)

Neil Brennen (Norristown, PA, USA) writes:

‘On 17 November 1899 Pillsbury visited Allentown, Pennsylvania. This information is from the chess notebook of Ludwig Otto Hesse, one of the local players who participated. Hesse does not record the result of the exhibition but does include a game he played with Pillsbury before the display. Both played blindfold, and the game lasted 15 minutes.’

Ludwig Otto Hesse – Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Allentown, 17 November 1899

Falkbeer Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 Nf3 dxe4 4 Nxe5 Bd6 5 d4 exd3 6 Bxd3 Nf6 7 O-O Bxe5 8 fxe5 Ng4 9 Bf4 Qd4+ 10 Kh1 Nf2+ 11 Rxf2 Qxf2 12 White resigns.

(2925)

When the Pillsbury position was given on page 25 of the book Schach ist schön, Schach bringt Freude! by H.-W. von Massow (Berlin, 1940) it was accompanied (on page 24) by the following specimen of a lone bishop administering mate:

White won by 1 Qh7+ Kb6 2 Qc7+ Nxc7 3 Bxd4 mate.

No other particulars were provided, and we do not recognize the position from other sources.

The book contained light text with much sloganeering and a glut of exclamation marks. It was published by the Verlag der Deutschen Arbeitsfront and featured a swastika on the title page.

(2934)

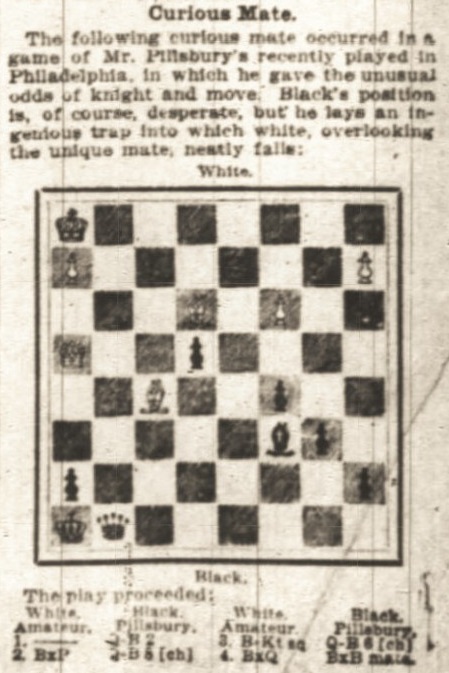

The Pillsbury game ending was printed under the title ‘An Odd Mate’ on page 208 of the December 1901 issue of Checkmate, with this introduction:

‘The following curious mate occurred in a game of Mr Pillsbury’s recently played in Philadelphia, in which he gave the unusual odds of knight and move. Black’s position is desperate, but he lays an ingenious trap into which White, overlooking the unique mate, neatly falls.’

If the information in the Literary Digest (see C.N. 2910) and this reference to Philadelphia are accurate, the date of the game can almost certainly be narrowed down to the first three weeks of October 1899 or 9 November 1899.

(2940)

The item on page 208 of Checkmate, December 1901 which was quoted in C.N. 2940:

We note that the text is barely different from what appeared on page 19 of the Chicago Tribune, 3 November 1901:

Details about the game, including the full score, are still sought. C.N. 2910 mentioned that the finish had been published in the Literary Digest, 25 November 1899.

Literary Digest, 25 November 1899, page 659

There are discrepancies regarding black pawns, and the initial moves 1 Qh4 Qf7 are not indicated.

See also The Single Bishop Mate.

Checkmate, August 1904, page 205 quoted from the Hereford Times an account of Pillsbury’s grievances about that year’s tournament in Cambridge Springs:

‘Pillsbury, in a letter to Dr Tarrasch, complains that Cambridge Springs is anything but an ideal place for a chess tournament. He says it is a “dreary desert”, monotonous and unattractive. Its only hotel, he adds, is remarkable only for the wakefulness of the majority of its inhabitants, who appear to roam about during the greater part of the night, comparing notes in a loud tone of voice, much to the discomfiture of the minority, who desire peaceful and refreshing slumber. The arrangements for the contentment of the inner man were not by any means to Pillsbury’s liking. Breakfast from 8 to 10, and any unfortunate who comes later cannot obtain as much as a cup of coffee for all the wealth of the Astors, or even a chessmaster; luncheon at 12.30, with very bad attendance, etc. On off days there seemed to be nothing particularly to do but to roam about aimlessly, there being no pleasing diversions of any kind to be found. During the 25 days, or rather nights, of his stay at Cambridge Springs, Pillsbury claims that, on an average, he had not more than two hours’ sleep per night. Perhaps, he says, I may have been more susceptible than some of the competitors, but I know that I was not by any means the only sufferer. Good games were exceedingly scarce, and of real masterpieces there were none.’

On page 225 of the September 1904 Checkmate, another participant, A.B. Hodges, rejected Pillsbury’s complaints in a detailed article which read as if drafted by the hotel management (‘The conveniences of the hotel were modern in every respect and not surpassed by the leading hotels of the Metropolis. Bathrooms fitted out with every detail, and no charge to the players for this necessary convenience …’).

On pages 90-91 of the May-June 1923 American Chess Bulletin Hodges provided some reminiscences of Pillsbury. C.N. 2304 quoted a paragraph from them (see page 237 of A Chess Omnibus), and below is a further extract, concerning Ajeeb:

‘Our friendship was enduring and, when he was in control of the chess automaton, it was my privilege, on a number of occasions, to relieve him from the steady monotony by taking his place, and I have always felt, from my own experience, that this strenuous work and the unhealthy environment of the chess figure must have to a great extent undermined his health and was the primary cause of his physical breakdown.’

(3140)

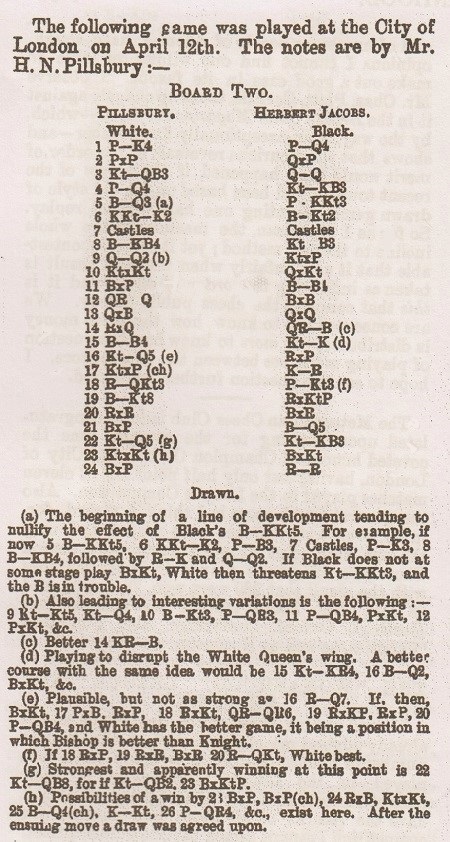

On 21 June 1902 Pillsbury gave a blindfold simultaneous exhibition on 16 boards (+10 –1 =5) at the Cercle Philidor in Paris. On pages 209-211 of La Stratégie, 20 July 1902 Gustave Lazard wrote a detailed account which included the following effective description of Pillsbury’s low-key demeanour:

‘Le visage du maître, entièrement rasé, est d’une délicatesse morbide; de ses yeux se dégage un charme pénétrant, une douceur enveloppante de caresse. Et l’on pressent tout de suite que le sceau du génie a stigmatisé de son empreinte cette effigie de camée au teint d’ivoire.

La taille est petite, le corps apparaît chétif; l’on éprouve cette impression que toute la vitalité de ce prodige a été englobée, accaparée par le cerveau.

Pillsbury n’a rien des façons d’un ‘épateur’. Ni discours, ni mise en scène; aucun ‘battage’. D’allures simples et modestes, correctement vêtu de l’habit noir, il gravit l’estrade qui lui a été réservée et prend possession du fauteuil qui l’y attend.

Puis, sans hâte, les jambes croisées, il allume un premier cigare auquel d’autres cigares feront cortège, à jet continu, jusqu’à la fin de l’émouvant combat qui s’engage.’

(3141)

From Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996) we cull a selection of quotes by the master. Page 11 (from an account of Hastings, 1895 sent by Pillsbury to the Brooklyn Chess Club and published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 24 August 1895):

‘I shall fight every game for all it is worth, hopeful as to the final result, and the records I enclose you may be interesting, if kept for the club, particularly if I should be fortunate enough to come out somewhere near the top. I am living at Cornwallis gardens, far from the maddening [sic] crowd, at the Queen’s Hotel, where Steinitz, Lasker, Tarrasch and four or five others are staying, and I walk or drive everyday, most of all making sure of the quiet necessary to do good work over the board.’

We should like to know the origin of the famous quote attributed to Pillsbury, ‘I want to be quiet; I mean to win this tournament’.

Page 15 (from an interview with the New York Tribune on 29 September 1895):

‘There is nothing nobler or more intellectual in sport than chess. It calls out qualities of character – of the heart as well as the head. I have often wondered why chess is not taught in the schools. It brings about concentration of thought upon a given subject as no other study I know of. In England its value as an educational influence for women is beginning to be understood, and I hope the day will soon come when American women will stand abreast of their English sisters in chess skill.’

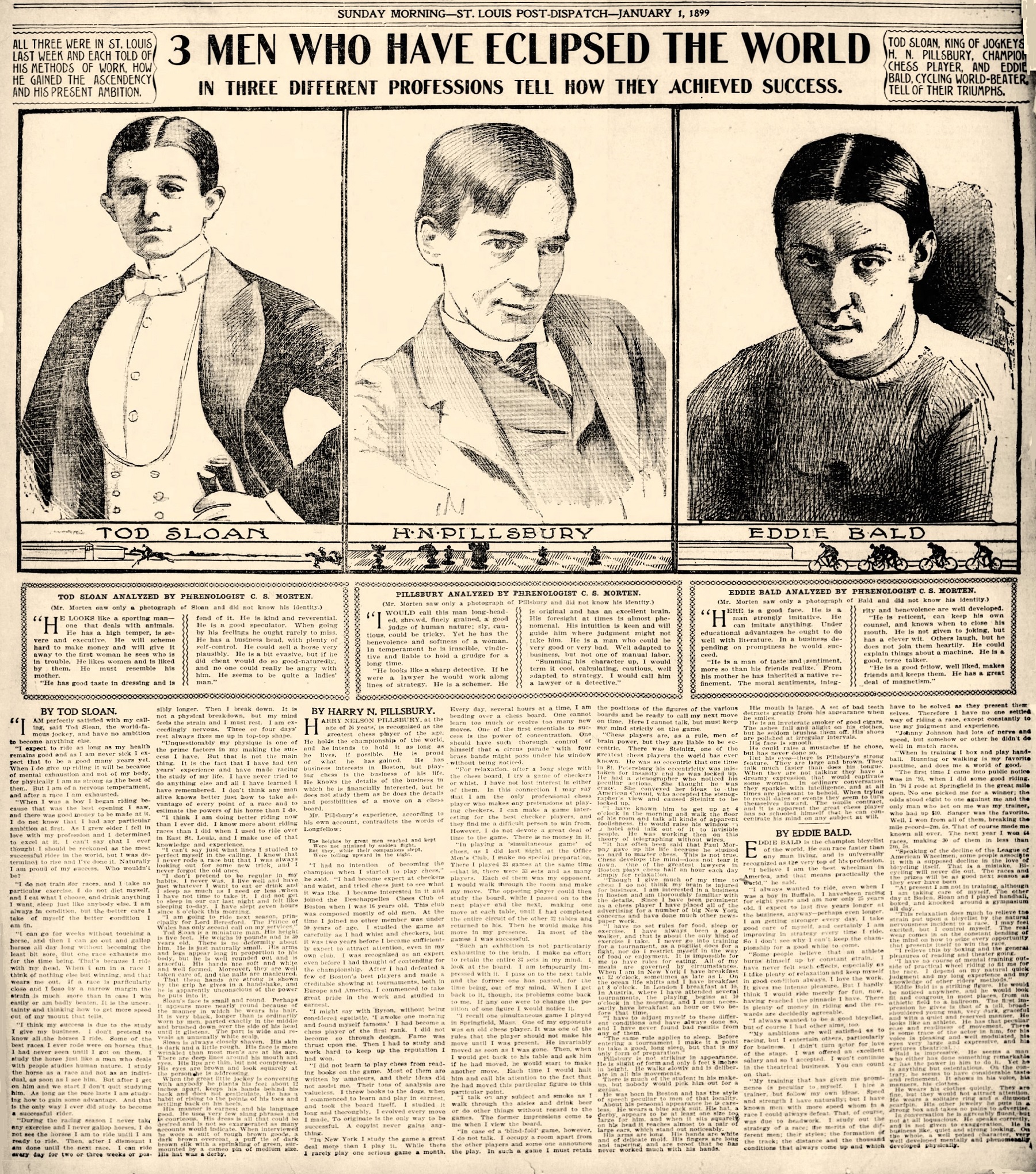

Page 363 (from the St Louis Post-Dispatch, 1 January 1899, page [17]):

‘I might say with Byron, without being considered egotistic, “I awoke one morning and found myself famous”. I had become a chessplayer of the first rank. I did not become so through design. Fame was thrust upon me. Then I had to study and work hard to keep up the reputation I had won.

I did not learn to play chess from reading books on the game. Most of them are written by amateurs, and their ideas did not assist me. Their tons of analysis are valueless. I threw books to the dogs, when I commenced to learn and play in earnest, and took the board itself. I studied it long and thoroughly. I evolved every move I made. To originate is the only way to be successful. A copyist never gains anything.

In New York I study the game a great deal more than I play it. While there I rarely play one serious game a month. Every day, several hours at a time, I am bending over a chess board. One cannot learn too much or evolve too many new moves. One of the first essentials to success is the power of concentration. One should have such thorough control of himself that a circus parade with four brass bands might pass under his window without being noticed.’

Page 365 (ibid.):

‘Before entering a tournament I make it a point to take a good, long sleep, but that is my only form of preparation.’

(3143)

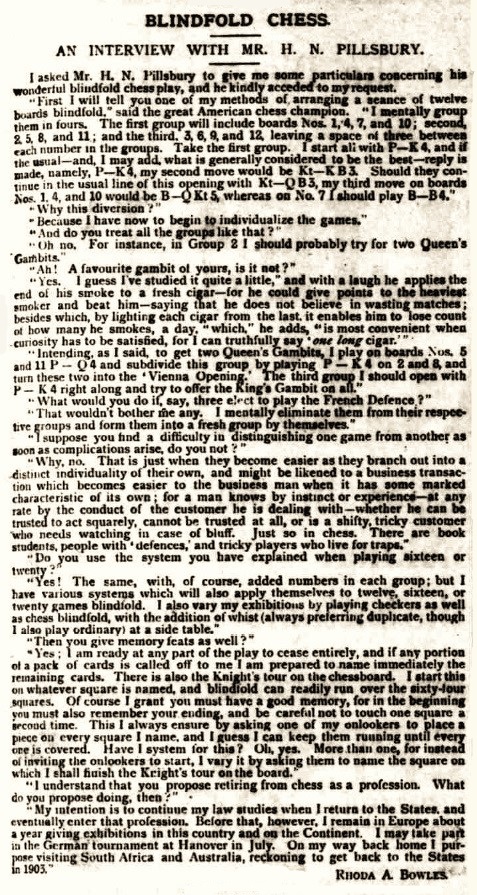

From the report of an interview on pages 215-216 of the American Chess Magazine, November 1898:

‘Janowsky spoke freely of his colleagues among the chess masters of the world, not hesitating to place himself in the niche he believed he fitted. He stated he classed Harry N. Pillsbury, the American champion, and Emanuel Lasker, the world’s champion, above Dr Tarrasch, and thinks that he and the champion are about equal in strength just below the other two. He thinks Lasker is a sounder player than Pillsbury, but Pillsbury possesses greater powers of combination than the world’s champion. Despite his modest admission that he considers the others above him, he said he did not fear any of them, and would not be averse to matches with them.’

(3173)

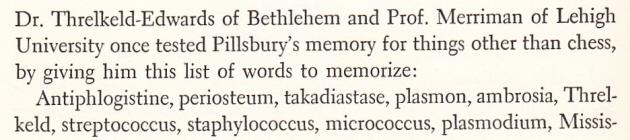

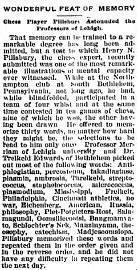

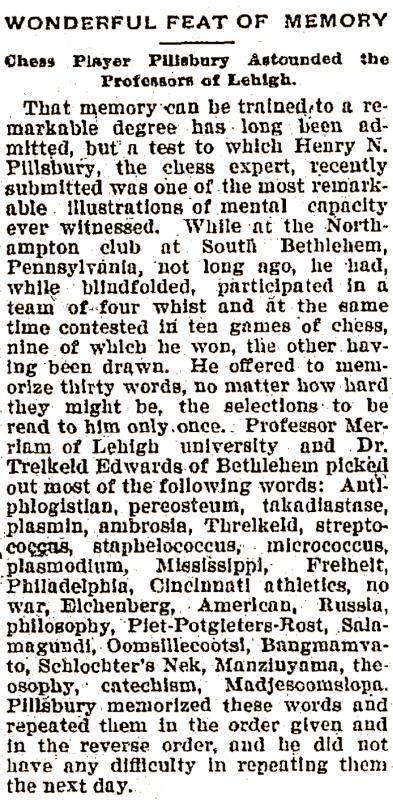

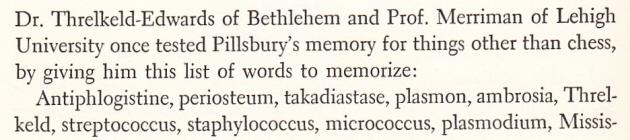

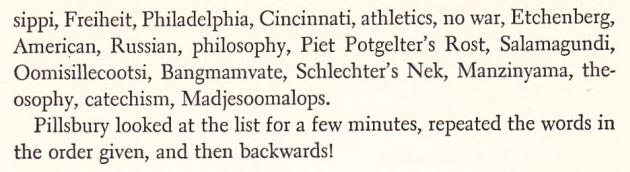

Chess writers have frequently referred to Pillsbury’s exceptional memory, padding out their accounts with the famous list of complex words which he effortlessly learned by heart on one occasion. But on which occasion? Can a reader refer us to a precise contemporary report of that exploit?

In the meantime, we mention two lesser-known displays. The first took place in the United Kingdom on 26 March 1902, after a match between Cambridge and a Ladies’ team at the Cambridge University Chess Club. The BCM (April 1902, page 199) reported:

‘At the call of time the unfinished games were adjudicated by Mr Pillsbury, who then gave the assembled company several remarkable illustrations of his mental powers. The first illustration was the placing of a knight upon any of the squares of the chessboard that the company might select, and then, without sight of the board, Mr Pillsbury rapidly dictated move after move by which the knight, without covering any one square twice, covered each one of the 64 squares in turn. In the next illustration a pack of cards was shuffled and about 20 dealt out, each card being called. Mr Pillsbury not seeing the cards simply listened, and then rapidly and accurately called off all the remaining cards that had not been dealt. Then a list of 30 words and names, some of them most fantastic, were written down by the company, and after the list had been read over he answered correctly all enquiries as to what name appeared against particular numbers and vice versa, and then in conclusion gave the whole list backwards in proper order. These feats were all accomplished by memorizing efforts alone, and bear striking testimony to the remarkable development of his mental powers, which have already become world-famous by his successful achievement of 20 games of chess played sans voir.’

The second account comes from a letter entitled ‘History of St Louis Chess Club’ by Lewis T. Haller on pages 88-89 of The Gambit, November-December 1931:

‘I think the most wonderful feat I ever saw a chessplayer perform was when Pillsbury played at the Columbia Club, Vandeventer and Lindell. He played 16 games of chess and eight games of checkers, all blindfold, and took a hand at duplicate whist at the same time. He won 15 and drew one at chess, won all the checker games and the rubber of whist. During the intermission Pillsbury picked up a copy of the Post Dispatch, read a paragraph, fully one inch deep, through once and handed the paper to me. He then repeated that paragraph backwards word for word without a single mistake.’

(3144)

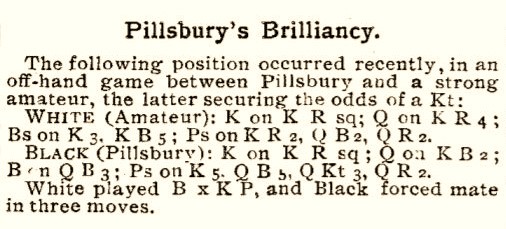

Memory Feats of Chess Masters refers to the complex list of words which Pillsbury is said to have learned, as related, for instance, in this ‘once’ version on pages 106-107 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

It has yet to be established when the list first appeared in print. As regards the individual words, Paul McKeown (Hayes, England) mentions an article dated 2002, ‘Piet Potgelter, Where Are You?’

That website is referred to on page 56 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009), which indicates that the memory experiment was conducted by Dr Threlkeld-Edwards and Professor Merriman of Lehigh University before Pillsbury began a blindfold exhibition in Philadelphia. The book remarks too:

‘Understandably perhaps, some of these items are spelled differently in different sources. Also, the exact conditions under which Pillsbury was tested are not given consistently from source to source.’

We add that another ‘once’ version of the Pillsbury episode was supplied by Frank Rhoden on page 66 of the February 1971 Chess Life & Review:

‘His superb powers of memory made him one of the finest blindfold players ever. He was once tested by a psychologist, one Dr Maguire, before giving a 20-board simultaneous in Philadelphia. A report of this performance appeared in the Illinois Medical Journal of October 1914. Pillsbury was given a list of words to commit to memory ...’

After listing the words, Rhoden concluded:

‘Pillsbury scrutinized the list, polished off 20 opponents, and then repeated the words perfectly. For good measure, he then repeated the list backwards.’

If a reader has access to the Illinois Medical Journal we should like to see exactly what its October 1914 issue contained.

(7702)

Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA) has supplied the requested article, ‘Mental States in Famous Chess Players’ by Louis Miller, published on pages 414-418 of the Illinois Medical Journal, October 1914.

It will be noted that the article, which has a number of obvious factual errors, mentions Pillsbury’s memorization of words on page 415, but without any list.

(7710)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) has found the following report on page 3 of the Littleton Independent of 14 December 1900:

It is not possible to present a larger version here, but, loupe à l’appui, it will be seen that the memory display is said to have taken place ‘recently’ at the Northampton Club in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Our correspondent adds that the following day the same account appeared on page 3 of another Colorado newspaper, the Eagle County Times.

(7713)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides a later but clearer version of the news report shown in C.N. 7713:

Source: page 3 of the Dona Ana County Republican (Las Cruces, New Mexico), 12 January 1901.

(7716)

C.N. 7702 showed an extract from pages 106-107 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

The same C.N. item quoted another ‘once’ version, by Frank Rhoden on page 66 of the February 1971 Chess Life & Review:

Pillsbury ‘... was once tested by a psychologist ...’

Now, we add the following from page 354 of Chess Words of Wisdom by Mike Henebry (Victorville, 2010):

‘He once memorized 30 difficult, unusual and large words that were read to him only once. He read them backwards and forwards without error and even remembered them the next day.’

However, in that passage the ‘he’ was not Pillsbury, but Blackburne.

Earlier in the same paragraph, Mr Henebry had a sentence about Blackburne which began:

‘He was once showed ...’

On the next page, still in the Blackburne section:

‘Once, playing blindfold, he announced ...’

The following paragraph was a quote from a Santasiere/Smith book. It began:

‘Once when Blackburne was giving a simultaneous exhibition ...’

After Blackburne there was a section on Steinitz, with more of the same. From page 359:

‘A story goes that once, he was arrested as a spy!’

(10515)

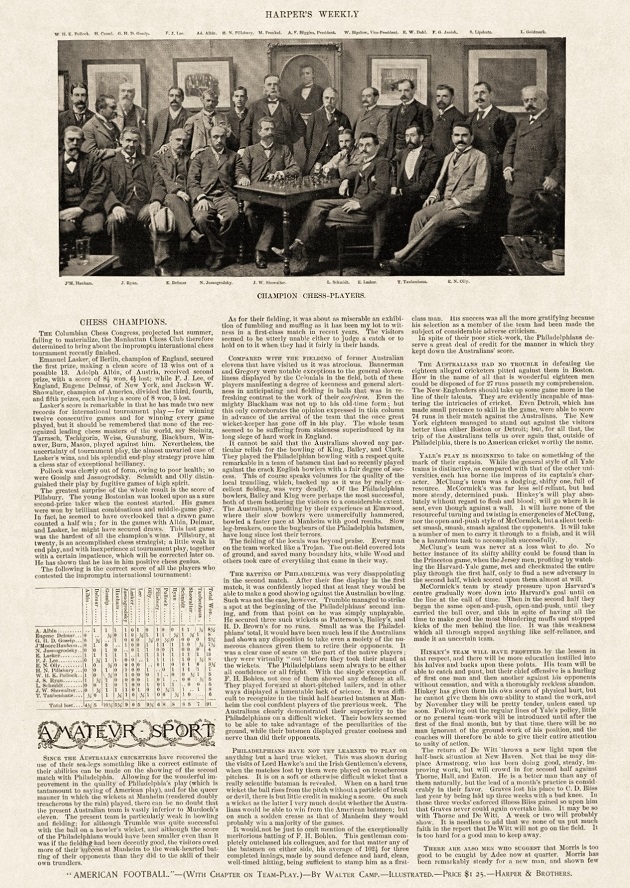

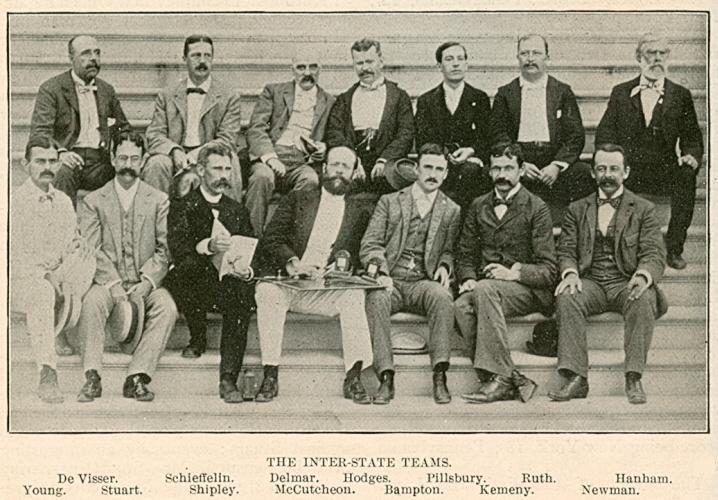

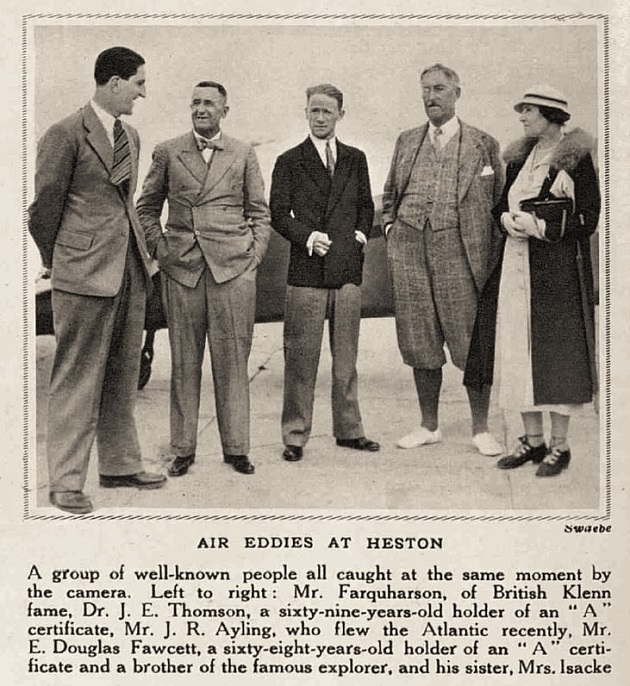

We are grateful to HarpWeek LLC for permission to reproduce a group photograph which appeared in Harper’s Weekly at the time of the New York, 1893 tournament:

From left to right in the back row: W.H.K. Pollock, H. Cassel, G.H.D. Gossip, F.J. Lee, A. Albin, H.N. Pillsbury, M. Frankel, A.F. Higgins, W.Bigelow, E.W. Dahl, F.G. Janish, S. Lipschütz and L. Goldmark.

Front row: J.M. Hanham, J. Ryan, E. Delmar, N. Jasnogrodsky, J.W. Showalter, L. Schmidt, Em. Lasker, J. Taubenhaus and E.N. Olly.

(3240)

Page 52 of Fred Wilson’s A Picture History of Chess has a photograph of Pillsbury ‘with an unnamed opponent at the old Manhattan Chess Club in New York City, 1893’. From the group shot in C.N. 3240 it is evident that the player in question was Jean Taubenhaus.

(3246)

Pillsbury and Steinitz

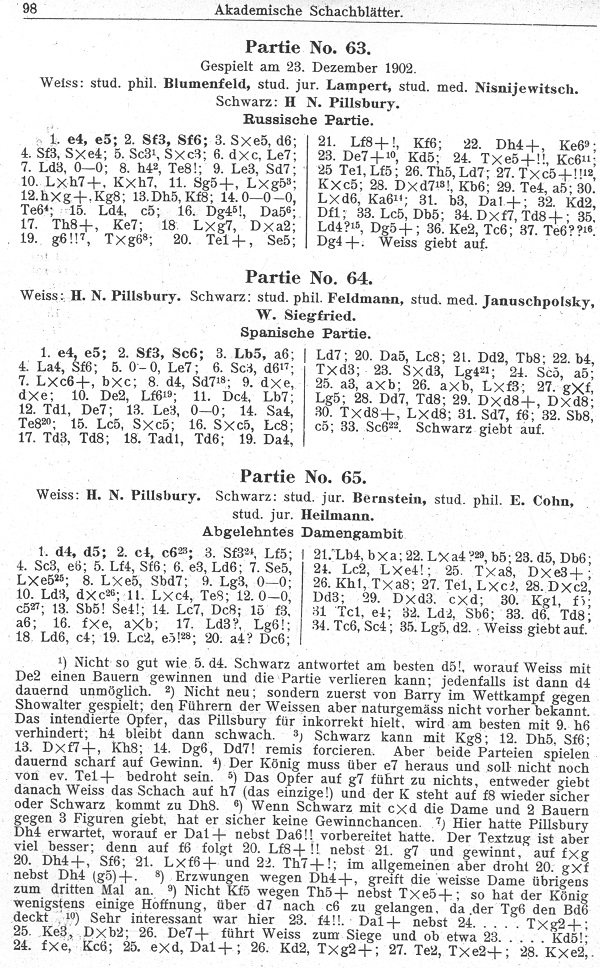

A position from page 41 of Les échecs dans le monde by Victor Kahn and Georges Renaud (Monaco, 1952):

White to move

This is stated to be from a game between H.N. Pillsbury and E.F. Wendell in a simultaneous exhibition on 40 boards in Chicago, 1901, the finish being 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Qh5 Rxh5 14 Ng8+ Ke8 15 Bxf7 mate.

Did Pillsbury win such a game? The following score was given on pages 319-320 of volume one of the second edition of Schachmeister Steinitz by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925):

Wilhelm Steinitz – N.N.

London, 1873

(Remove White’s rook at a1.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 d3 Nc5 6 d4 Na6 7 Bc4 Qe7 8 Nc3 h6 9 O-O g5 10 Nd5 Qd8 11 Nf6+ Ke7 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Qh5 Rxh5 14 Ng8+ Ke8 15 Bxf7 mate.

(3288)

See too page 230 of the City of London Chess Magazine, October 1874, where the Steinitz game was annotated by Zukertort.

Lasker on Pillsbury

On page 171 of World Chessmasters in Battle Royal by I.A. Horowitz and H. Kmoch (New York, 1949) Kmoch wrote:

‘… although he had unequaled ability to master complications, [Lasker] did not care for prepared complications in the opening. During one of the many discussions I had with him he once accused Pillsbury of having started the deplorable custom of studying the openings too extensively. Lasker himself never paid much attention to the openings.’

(3378)

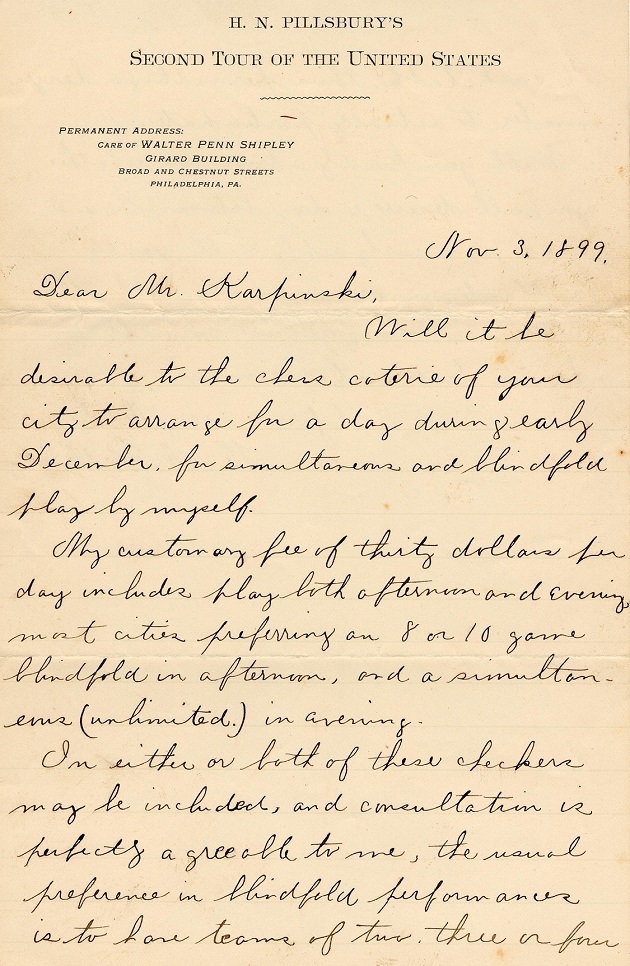

From our collection comes the following item of memorabilia, an envelope addressed by H.N. Pillsbury in 1899:

(3598)

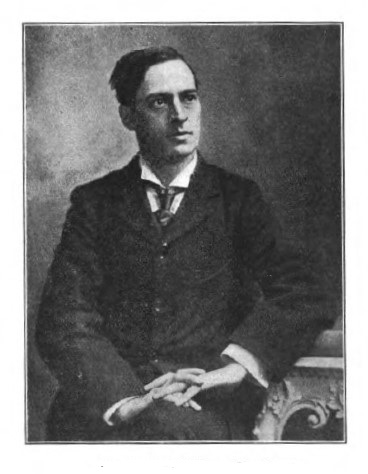

C.N. 702 (see pages 184-185 of Chess Explorations) referred to a report on page 26 of the January 1903 BCM that after a game of living chess between Pillsbury and H.L. Bowles in London on 29 November 1902 ...

‘... the proceedings closed with the setting-up of a two-move problem specially composed by Mr H.N. Pillsbury, and ten minutes were allowed to the audience to find the solution, it being announced that the author of the first correct solution opened would be awarded a pocket chess board as a prize, and the fortunate winner proved to be a young son of Mr Gunsberg, the chess master.’

We asked for further information on the problem and on Gunsberg’s son, but without result.

In 1996 Jacques N. Pope brought out Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion, page 252 of which gave three problems by Pillsbury, i.e. a couple of three-movers (one composed jointly with G. Reichhelm) and the following two-mover:

The source of this composition was specified as the Times Literary Supplement, 18 December 1903, i.e. a year after the above-mentioned London event. Was it nonetheless the problem successfully solved by Gunsberg Junior?

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) sends us a fourth Pillsbury problem, from Womanhood, August 1900 (where it was marked ‘original’):

Mate in seven.

As regards Pillsbury’s solving skills, the following item by G. Koltanowski on page 83 of the December 1969 Chess Digest Magazine comes to mind:

‘White to play and mate in three moves. The author of the problem wrote “... a horrible looking think [sic], which was set up to be difficult and not elegant ...” It was shown to the Masters participating at the New York International Tournament of 1893. It took Dr E. Lasker, champion of the World at that time, 35 minutes to solve. Pillsbury took 40 minutes. The others were way off.’

Quickly passing over Koltanowski’s customary inaccuracy (in 1893 Lasker was not world champion), we note that he did not name the composer. As Michael McDowell mentions to us, the problem is number 247 in A.C. White’s Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913). Pages 200-201 identify it with the caption ‘Manhattan Chess Club, 1893’ and quote Loyd:

‘No. 247 is a horrible looking affair designed for a State Solving Contest. It was evidently posed for difficulty and not for elegance.’

What was the source of Koltanowski’s assertion about the (surprisingly long) time taken by Lasker and Pillsbury to solve the problem?

(3751)

From page 224 of Womanhood, 1903:

Mate in three

The heading was ‘Specially composed for Womanhood by H.N. Pillsbury’. The following issue (page 296) noted that there were two solutions.

(11047)

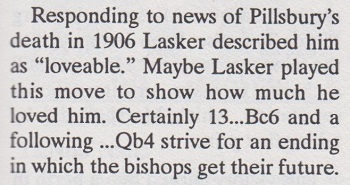

Neil Brennen (Spring City, PA, USA) forwards this game, annotated by Gustavus Reichhelm in the Philadelphia Times, 20 November 1898:

Ching-Chang – J. Hall1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 d5 6 Bd3 Bg4 7 h3 Bh5 8 g4 (‘Had Mr P-, we mean Ching-Chang, suspected the prowess of his adversary, it would not thus lightly have pushed the pawns.’) 8...Bg6 9 Ne5 Bd6 10 Nxg6 hxg6 11 Qf3 Qe7 12 Be3 Nd7 13 Nc3 Bb4 14 Bxe4 dxe4 15 Qe2 f5 16 a3 Bxc3+ 17 bxc3 Nb6 18 c4 O-O-O (‘About this time the barker, boosters, and even the “young” attendant began to look anxiously at the game. The figure had met an opponent worthy of its steel.’) 19 c5 Nd5 20 c4 Nxe3 21 fxe3

21...f4 (‘A masterly move, quite in the vein of Mr Hall’s brilliant style. If Chingy takes this pawn Mr Hall proceeds with ...e3, etc.’) 22 Qf2 g5 23 Rb1 c6 24 Rb3 Rhf8 25 Qb2 fxe3 26 Rxe3 Rf3 27 Rxf3 exf3+ 28 Kf2 Qe4 29 Re1 Qf4 30 Rb1 Rd7 31 d5 Re7 and wins. (‘Ching-Chang, however, fought it out for over 20 moves before it had the grace to resign. It was so unaccustomed to defeat, you know.’)

Ching-Chang, as Mr Brennen points out, was an automaton (see, for instance pages 76 and 170 respectively of John Hilbert’s books on Napier and Marshall). A question raised by our correspondent is whether Reichhelm’s note at move eight was a hint that the conductor of the white pieces was Pillsbury.

(3854)

Now Mr Brennen quotes a passage from the same newspaper three weeks later (11 December 1898):

‘Miss Maynell DeVaney asks who Mr P- is who manipulated Ching-Chang against Mr Hall. Well, it’s something of a secret, at least as far as print is concerned, but when we tell her it is a very celebrated player she will be able to guess the name.’

Mr Brennen also provides some excerpts from Reichhelm’s column a little earlier in the year. On 11 September 1898 he wrote, ‘the famous chess automaton is now in our midst’, and a fortnight later he referred to the machine as ‘Ultimatum’ when presenting its encounter with Charles Newman:

Ultimatum – Charles John Newman

Philadelphia, 1898

French Defence

(Notes – abridged – by G. Reichhelm)

‘What chessplayer has not heard of the famous Ultimatum? It is true, this is not exactly its name, but it is what Judge Wolff calls it, and whatever he says goes. The Ultimatum had been pursuing an uncheckered career of victory, when in an evil moment for itself Charles John Newman, of the Franklin Chess Club, appeared on the scene, and at once the machinery of the enchanted figure began to creak …’

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 f6 4 exf6 Nxf6 5 Nf3 c5 6 Bb5+ Nc6 7 Ne5 Qb6 8 Bxc6+ bxc6 9 dxc5 Bxc5 10 Nd3 O-O 11 Nxc5 Qxc5 12 O-O e5 13 Qe2 e4 14 c3 Ng4 15 Be3 Qd6 16 f4 exf3 17 gxf3 Ba6

‘At this point there was a pause and the machine which descended from the conqueror of Frederick the Great and Napoleon found that it lacked the necessary wheel to make an answer. Seeing this, Mr Newman, with the characteristic courtesy of a great master, offered a draw. And thus endeth the lesson, of which the moral has been mislaid.’ Drawn.

Quite apart from Ching-Chang and Ultimatum, it may be wondered how Ajeeb fits into the story. We quote from page 212 of Chess: Man vs Machine by Bradley Ewart (London, 1980):

‘... Pillsbury planned to take Ajeeb “out west” and it is known that he exhibited the automaton for several weeks in 1898 at the Dime Museum at Ninth and Arch Streets in Philadelphia. While there, Charles J. Newman, an international cable chessplayer, went one day to play the automaton. “I should have beaten him”, reported Newman, “if after lifting a rook he had not put it back and played another piece. Can this automaton take moves back?”, I asked indignantly. “Yes”, said the lady attendant, “he can”. And worse luck he did.’

(3895)

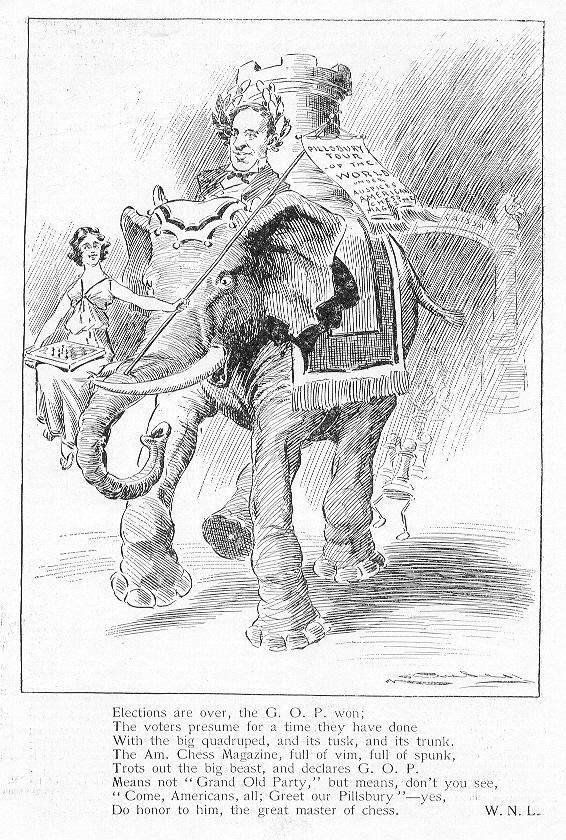

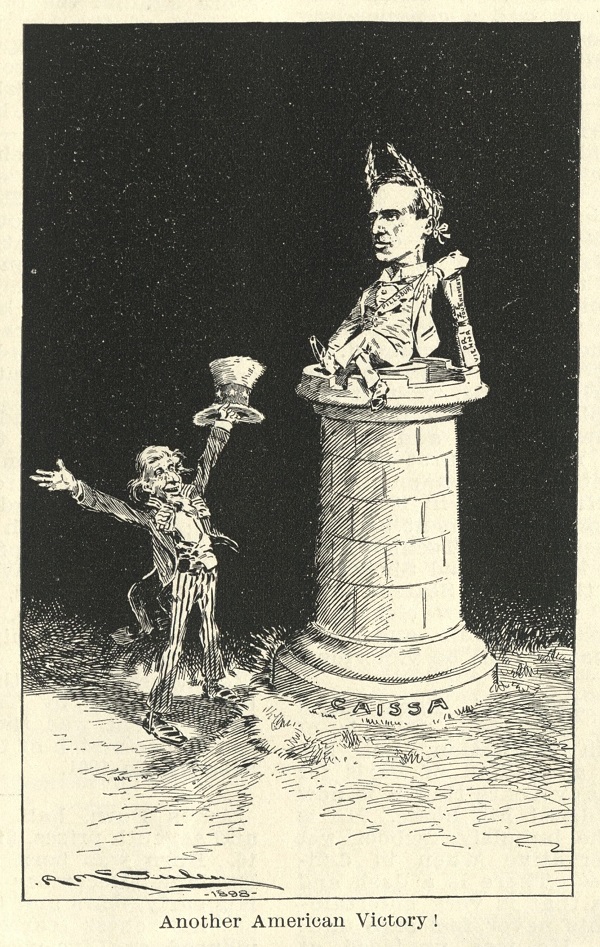

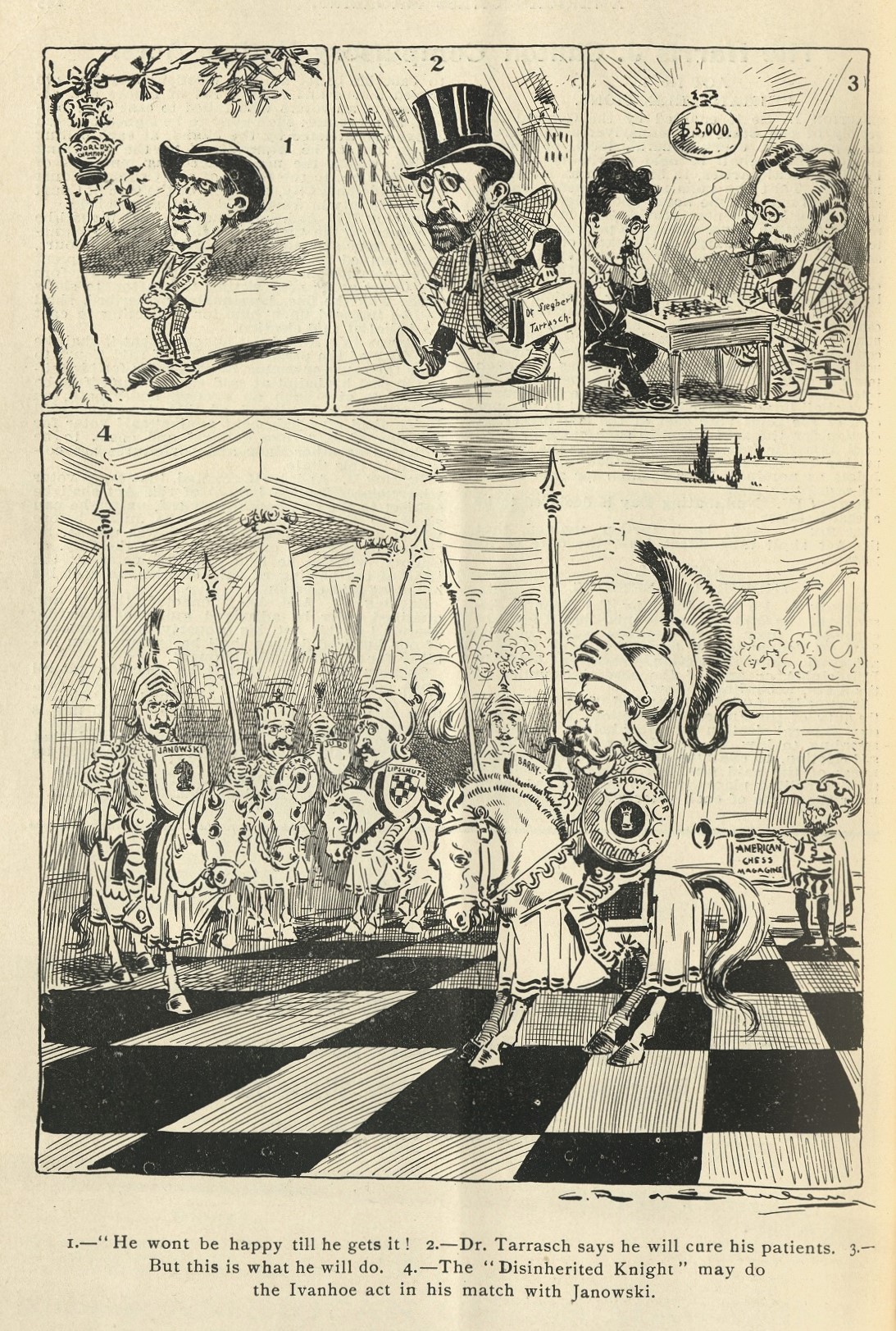

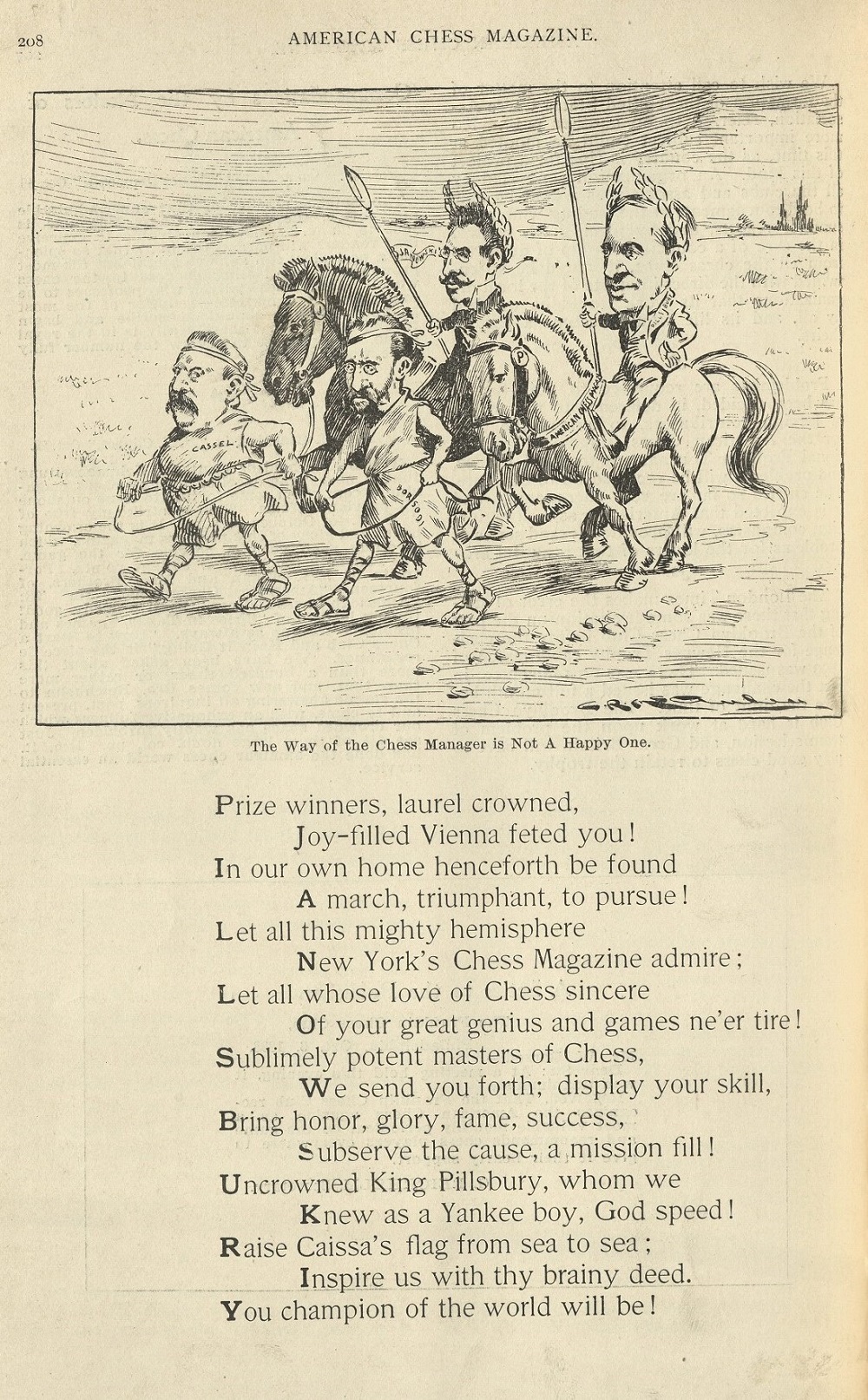

The cartoon and poem below come from page 244 of the December 1898 American Chess Magazine, to mark Pillsbury’s chess tour and the victory of the Republican Party in the mid-term elections:

(3932)

Page 622 of the Literary Digest, 19 May 1900 gave the following extracts from an article by Pillsbury in The Independent of 10 May that year:

‘Perhaps the mental quality most useful to the chessplayer who wishes to rise to distinction in the game is concentration – the ability to isolate himself from the whole world and live for the events of the board while a match is proceeding. And yet “concentration” does not quite suit me as expressing the quality I refer to, for concentration implies narrowing, and I am satisfied that the influence of chess broadens the mind.

Besides the quality which we have, for want of a better name, called concentration, there are others that are essential to the good chessplayer. One of these is patience, or ability to wait. We have players who are known as plungers, who see an opening and drive ahead into it without studying out all that it leads to. Such men can never become good players. The chessmaster must have full control of himself at all times. He must not be impatient, he must be content to mark time, as it were, till he sees the result of his opponent’s attack, and he must be able to resort to meaningless moves to kill time if there is no other way of holding fast to the fortified position till the danger is over. Not all men can do this. They want to rush out and attack, and thereby they expose themselves and lose the game.

Another most useful quality is accuracy, in which Lasker excels. His foresight has not so great a range as that of Chigorin, for instance, but so far as he sees he is infallible. Chigorin may see five moves ahead and Lasker only three, but the latter more than evens up matters by his deadly accuracy and thoroughness.’

(4165)

From pages 149-150 of the Literary Digest, 2 February 1901:

‘In a lecture, recently delivered in Chicago, on chess openings, Mr Pillsbury said that in modern practice among the great masters only two openings – the Ruy López and the Queen’s Pawn – are considered to retain the advantage of the first move for any length of time. He believed that the Berlin Defense of the Ruy López was the best. Of the Petroff Defense, which he brought into practise again in the St Petersburg tournament several years ago, he does not now entertain as good an opinion as he did then. He believes if White continues with 3 P-Q4 the advantage remains with the attack, and for that reason he has abandoned it. He agrees entirely with the principles laid down in Lasker’s Common Sense in Chess and says every great master must necessarily do so. Against the Evans Gambit he recommends Lasker’s defense or the refusal of the gambit. In either case the defense should obtain a better game.

He also holds that the Falkbeer Counter-Gambit against the King’s Gambit should yield the second player the superior, or at least equal, game. He dwelt at length on “the waiting move”, claiming there should be no such thing in a correct game of chess. Should a player at any time make an indifferent move like P-R3, simply because he knows of nothing better, there is an admission of weakness in his game. On the other hand, if such a move is made with the pre-conceived plan of making a general advance in the pawn formation, it is then a sign of strength. He is of the opinion that between even players in serious games the attack, with accurate play, should win about two games in ten, the others resulting in draws.’

(4202)

Walter B. Hart (Burra Creek, Australia) enquires about what became of Pillsbury’s wife.

‘We know from Nick Pope (Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion), John Hilbert (Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster) and others that Harry Pillsbury married Mary Ellen Bush on 17 January 1901. Apparently he was engaged to her for some three years before their marriage and met her at one of his chess exhibitions. Other than that, not much seems to be known about Mrs Pillsbury or her fate after Pillsbury’s early death in 1906.

In the group photograph taken at Hanover, 1902 there is a female sitting next to what looks like Pillsbury. The couple were touring Europe at that time; is there any chance that this is indeed the elusive Mrs Pillsbury?

It is reported that she was the daughter of Judge Bush of Monticello, NY and the aunt of W.E. Napier’s wife Florence (née Gillespie), Florence’s mother being Mary Ellen’s elder sister, Henrietta.’

We offer a few observations:

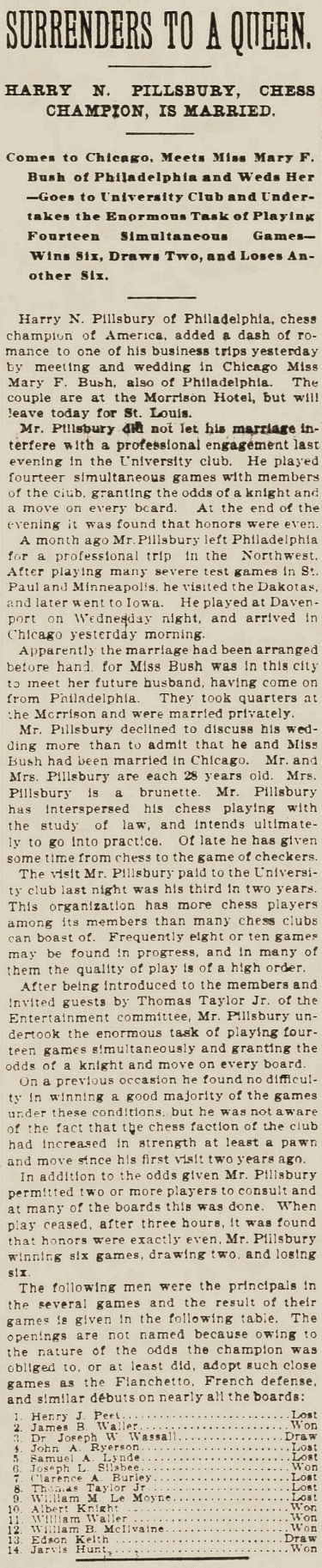

1) The references are pages 37-38 of the Pillsbury book (which quotes Louis Uedemann in the Chicago Tribune of 20 January 1901) and page 329 of the Napier volume. The Uedemann report also appeared on page 5 of Checkmate, January 1901.

2) Below is the relevant part of the Hanover, 1902 group photograph, i.e. a detail from the front cover of the dust-jacket of the 1983 Olms reprint of the tournament book:

3) Some further details appeared on pages 101-102 of the March 1901 BCM. The wedding took place ‘at the home of Mr Bush, a brother of the bride’, and her father was described as follows:

‘... the late Albert J. Bush, who at his death was judge of the County Court, Sullivan County, New York, and resided at Monticello. Judge Bush was considered the ablest lawyer in Sullivan County, and up to the date of his death was respected by all throughout the community in which he resided alike for his ability and integrity of purpose. His daughter was born at Monticello, and resided there with her mother several years after the death of her father. She and Mr Pillsbury have been friends for many years. Prior to her marriage Mrs Pillsbury spent some time in Philadelphia with friends of her family, and during that time many of Mr Pillsbury’s friends had the pleasure of meeting her. All were charmed not only with Mrs Pillsbury’s beauty but with her unusually bright mental attainments ...’

4) We recall seeing no post-1906 information about her.

(4246)

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) has found two webpages which provide information about H.N. Pillsbury’s wife, née Mary Ellen Bush:

WikiTree: Mary Ellen ‘Mamie’ Shearf, born about March 1872 in Sullivan County, NY, the daughter of Albert J. Bush and Charlotte V. (Horton) Pelton, the other children being William H., Henrietta T. Gillespie, Etta and Elvin W. She married Henry D[uBois] Southard in Monticello, NY on 8 October 1890, Harry Nelson Pillsbury in Chicago, IL on 17 January 1901, and Frank Shearf (place and date unknown).

Archives database: Mary B. Shearf was aged 67 at the time of the 1940 US census, and was living at Somers Point, Somers Point City, Atlantic, NJ. The other members of the household were her husband, Frank Shearf, aged 66, and Alberta Shearf, aged 11.

We can add that the 1920 US census does not list Mary Shearf’s husband but states that the couple had a daughter, Ruth, born around 1912 in Pennsylvania. She appeared in the 1930 census under the name Ruth Chaffett (‘widowed’), and a 1/1½-year-old daughter, Alberta Chaffett, was also mentioned.

(4858)

Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) sends this cutting from page 1 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 January 1901:

(9694)

Another photograph of H.N. Pillsbury’s wife is on page 147 of issue 38 of Womanhood, 1902. It is in the recent two-volume reprint of the Womanhood columns (of Rhoda A. Bowles) by Publishing House Moravian Chess, but is a clear version available from the original magazine?

(10562)

See also C.N. 9458 below.

Following on from C.N. 4246, our correspondent in Australia, Walter B. Hart, writes:

‘Pillsbury’s gravestone (in four-sided obelisk form) can be viewed at the ‘Find A Grave’ website. Only two sides are visible in the photograph supplied, with one side inscribed Harry N. Pillsbury 1872-1906 and the other with three names and dates which seem to read: Edwin B. Pillsbury 1860?-1941; his wife M. Eva 1865?-1937; and May F. Pillsbury 1870-1941.’

The pencil sketch of Pillsbury below was drawn by Mrs G.A. Anderson in 1898 and was published on page 66 of Chess Pie, 1922:

(4247)

From Norman Pillsbury (Atascadero, CA, USA):

‘I can shed a little light on the inscriptions, based on the 1898 book The Pillsbury Family by David B. Pilsbury and Emily A. Getchell. Page 162 gives the following information:

“Luther B. (Caleb, Caleb), b. 23 Nov. 1832; m. 14 Aug 1863, Mary A. Leath, of Lynnfield, Mass., who d. in Somerville, 20 Nov. 1888, aged 50. Children:

i. Edwin B., b. in Hopkinton, N.H., 30 Aug. 1866

ii. Ernest D., b. in Hopkinton, N.H., 19 May 1868

iii. May F., b. in Bridgewater, 15 May 1870

iv. Harry N., b. in Somerville, 5 Dec. 1872.”’

(4380)

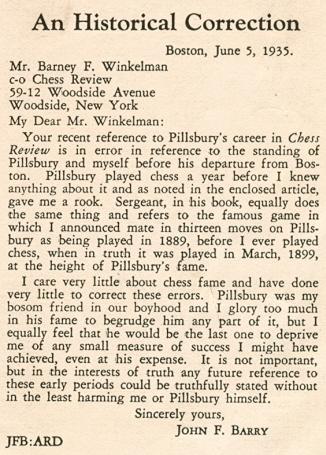

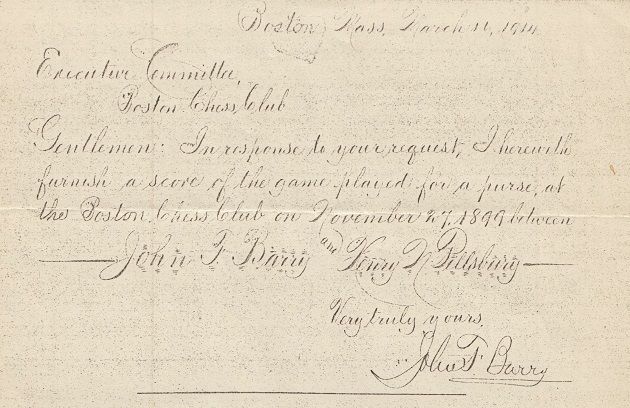

In Boston in 1899 J.F. Barry defeated H.N. Pillsbury. After 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 d4 Nxe4 5 d5 Nd6 6 Nc3 e4 7 Ng5 Ne5 8 Qd4 f6 9 Ngxe4 Nxb5 10 Nxb5 a6 11 Qa4 Rb8 12 Nd4 Be7 13 Qb3 d6 14 f4 Ng4 15 O-O f5 16 Ng3 O-O 17 Nc6 bxc6 18 Qxb8 cxd5 19 Qb3 c6 20 Bd2 Qc7 21 Rae1 Bf6 22 h3 Bd4+ 23 Kh1 Nf2+ 24 Kh2 Ne4 25 Nxe4 fxe4 26 Rxe4 Bxb2 27 c3 Ba3 28 Rfe1 Bc5 29 Re7 Qb6 30 Qd1 Bf5 31 Qh5 h6 ...

... Barry announced mate in 13 moves, starting with 32 Rxg7+.

Page 16 of Pillsbury’s Chess Career by P.W. Sergeant and W.H. Watts (London, 1923) misdated the game 1889, as do various databases today – despite the improbability of Barry’s having won such a game when only in his 16th year.

John Finan Barry

The game was given on pages 275-276 of Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996), courtesy of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 7 December 1899, whose introduction Pope quoted as follows:

‘While Pillsbury was in Boston last week an exhibition game for a stake was arranged at the rooms of the Boston Chess Club between him and John F. Barry of cable match fame.’

As mentioned on page 393 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, Barry chose the game as the best of his career. See pages 66-71 of Chess Masterpieces by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1928), which gave it with Barry’s brief notes, together with some supplementary remarks by Marshall. The latter wrote in his introduction:

‘Needless to say, in a match [sic] such as the one played by Barry against Pillsbury the announcement of a mate in 13 moves is unique, and this brilliant game is one of which any master in the world would be proud to claim ownership.’

(4582)

For further details, see The Best Chess Games.

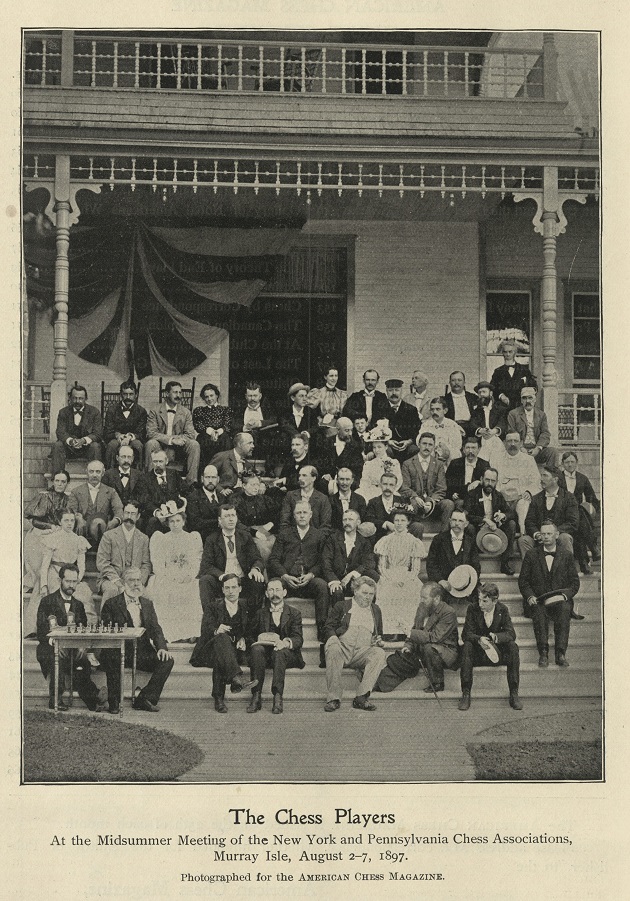

Regarding Thousand Islands, 1897, below is a photograph from page 148 of the American Chess Magazine, August 1897:

(5550)

We add a letter from Barry published on page 185 of the August 1935 Chess Review:

(6978)

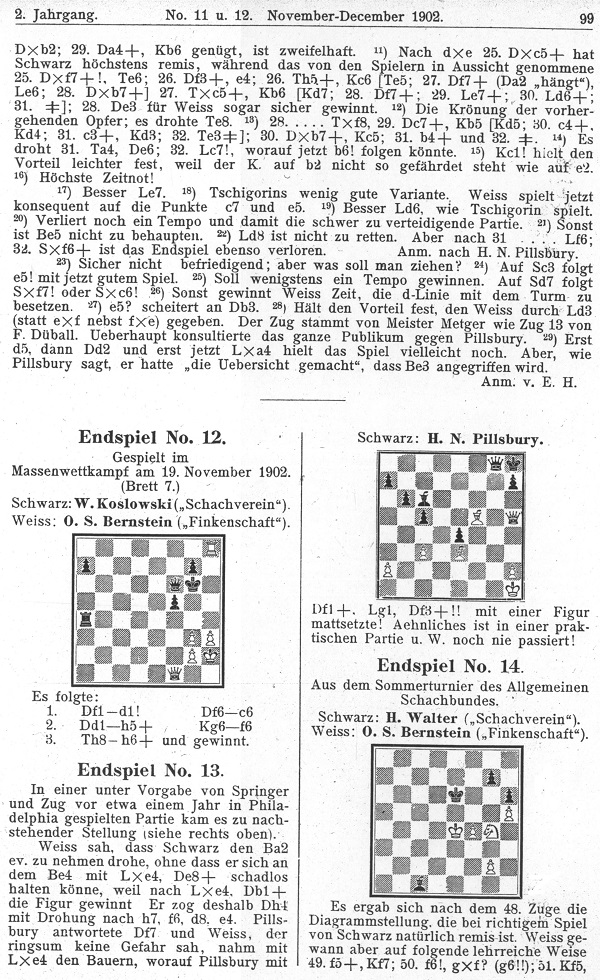

The conclusion of Barry v Pillsbury, Boston, 1899 (White to move):

White announced mate in 13

In 1989 Richard Lappin (Jamaica Plain, MD, USA) sent us the following, from the archives of the Boylston Chess Club (Boston):

We note that this document was referred to on page 30 of the March-April 1978 issue of Chess Horizons.

(11851)

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Pages 9-10 of Chess World, 1 January 1949 had a feature on ‘Gippsland’s chess king, veteran T.J. Edwards’:

‘... Without too much conventional biographical detail, we now take our readers back to 1901, and set them down in the famous old city of Bath. One of the most glamorous chess masters of all time is giving a “simul” there. It’s Harry Nelson Pillsbury. Some of his opponents have tumbled their kings already. Suddenly Pillsbury is seen to be dismantling a position. He is actually restoring it to an earlier stage. Then he beckons the onlookers, and asks them, “Don’t you think I’ve got the best of it here?”

They all agree that he certainly has (see diagram) as he is threatening Qxh7+ and what not.

“Now”, says Pillsbury to his youthful opponent, “Play through your finish again. And the two repeat, for the edification of the onlookers, the combination which has just ended in real earnest. Here is the diagram of the restored position.

White: H.N. Pillsbury Black: T.J. Edwards (Black to move)

Having already indicated the identity of the youthful opponent, we give the moves.

18...e4 19 Nxe4 Bxf3 20 Qxf3 (If 20 Ng5, simply 20…Qxg5 21 Qxh7+ Kf8 22 Qh8+ Ke7. Or, in this, 22 g3 Nf4.) 20...Bxh2+ 21 Kxh2 Rh6+ 22 Kg1 Qh4 23 Qh3 Nf4 24 Qxh4 Ne2+ 25 Kh2 Rxh4 mate.

Then Pillsbury shook hands, saying, “Congratulations – brilliant little combination – took me completely by surprise.”

So that was Pillsbury. The chess world was not permitted to keep him long. A few years later he died, aged 33.’

It would seem that this game was played not in 1901 but in 1903 (on 31 January). Defeat by Pillsbury at the hands of T.J. Edwards was mentioned on page 23 of the 6/2000 Quarterly for Chess History.

(4904)

John Hilbert has been examining issues of the Washington Times, which, together with many other US publications of the period 1900-1910, are available on-line courtesy of the Library of Congress. Our correspondent writes:

‘There was a short-lived chess column in the Washington Times that ran from 7 November 1903 to 30 April 1904. Initially edited by W.B. Mundelle, it was taken over by F. Edward Mitchell as from 12 March 1904, because Mundelle had retired and moved to San Antonio, Texas for health reasons. On page 8 of the 21 November 1903 issue the column gave this forgotten game played at the Washington Chess Club:

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (blindfold) – F.N. Stacy

Washington, 14 November 1903

Falkbeer Counter-Gambit1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 d3 Nf6 5 Qe2 Bc5 6 dxe4 O-O 7 Nf3 Ng4 8 Nc3 Bf2+ 9 Kd1 Bb6 10 Ke1 c6 11 h3 Nf2 12 Rh2 Re8 13 Be3 Bxe3 14 Qxe3 Nxe4 15 Nxe4 cxd5 16 Rd1 Bf5

17 Rxd5 Qxd5 18 Nf6+ gxf6 19 Qxe8+ Kg7 20 g4 Bd7 21 Qe3 Nc6 22 Rd2 Qa5 23 Kf2 Re8 24 Qd3 Be6 25 a3 Qb6+ 26 Kg2 Qxb2 27 f5 Bc8 28 Qb3 Qxb3 29 cxb3 Re3 30 Rd3 Rxd3 31 Bxd3 Ne5 Drawn.

In that blindfold display Pillsbury played simultaneously eight games of chess (+5 –0 =3) and four of checkers (+0 –1 =3).

The same column gave the ending of the Pillsbury v Guthrie draw, whose full score appeared (although only with the heading “USA 1904”) on pages 273-274 of Jacques N. Pope’s book on Pillsbury. That game occurred in a second display at the Washington Chess Club on 14 November 1903 (19 chess games and seven games of checkers, played simultaneously but not blindfold).

That column of 21 November 1903 also included the scores of two checkers games by Pillsbury, against F.E. Potts and Paul F. Grove.

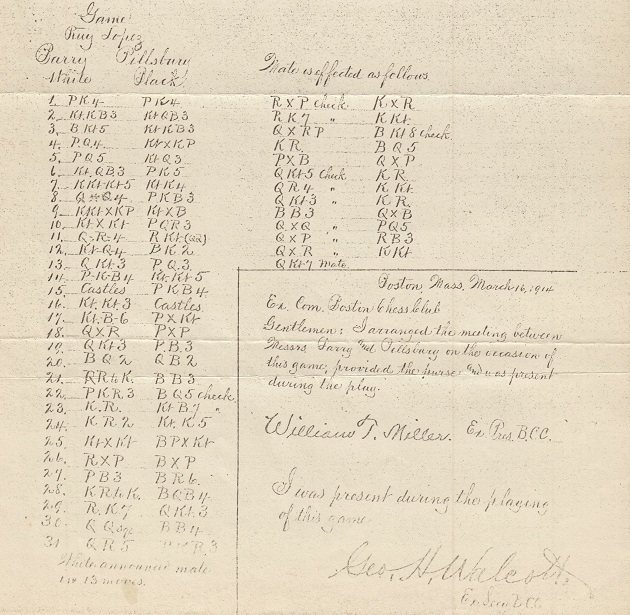

On page 3 of its 9 April 1905 issue the Washington Times had a news story about Pillsbury entitled “Tragic collapse of a brilliant mind”. By way of example, the first paragraph reads:

“When Harry Nelson Pillsbury, the American champion chessplayer, one time champion of the world, and probably the most marvelous trick chessplayer that ever lived, tried to commit suicide in Philadelphia during a fit of insanity a few days ago, he only fulfilled the fate which has been that of nearly all of the great masters of the game. The tremendous mental strain which they undergo in the great tournaments, aided and abetted by excessive use of stimulants to keep them keyed to the proper pitch, is too much for the human brain, no matter how abnormally brilliant.”’

(5158)

Below is the score of a game of checkers won by Pillsbury in Washington on 14 November 1903, as mentioned in C.N. 5158:

‘And this is what Mr Pillsbury did to Paul F. Grove. Pillsbury’s move.’ f6-e5 c3-d4; e5-c3 b2-d4; h6-g5 a1-b2; d6-c5 g3-f4; g5-h4 d2-c3; g7-h6 d4-e5; e7-d6 e3-d4; c5-e3 f2-d4; h8-g7 e1-f2; f8-e7 f2-e3; e7-f6 g1-f2; d8-e7 c3-b4; h6-g5 f4-f8. ‘All over.’

Source: Washington Times, 21 November 1903, page 8.

For readers’ convenience we have converted the score from ‘11-15 22-18’, etc. to the algebraic notation.

(5159)

Olimpiu G. Urcan provides a report from page 14 of the Milwaukee Journal, 28 June 1896:

(5209)

Also from Olimpiu G. Urcan come a report and a cartoon published on page 4 of The World (New York), 20 June 1896:

(7648)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) sends this game from page 6 of L’Echo de Paris of 16 March 1903:

For more information, see the complete column.

Our correspondent has also provided, from page 6 of L’Echo de Paris of 8 April 1901, the game Marshall v Henig, Monte Carlo, March 1901.

(6478)

A position on page 240 of the November 1892 American Chess Monthly:

It does not seem that the Monthly reverted to the position, i.e. to give the conclusion (which was presumably 1...h5+ 2 Kg3 Bh4+, etc.).

(7628)

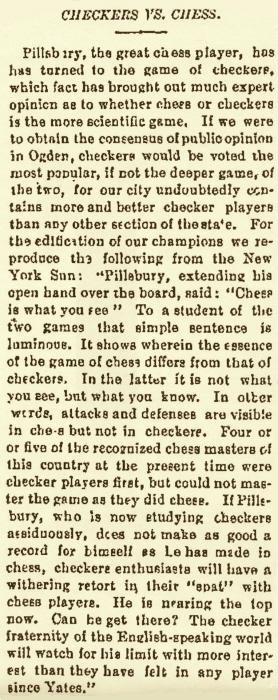

Olimpiu G. Urcan has submitted this photograph taken at Monte Carlo in 1902, from Caras y Caretas, 26 April 1902:

A copy of better quality is sought.

(7649)

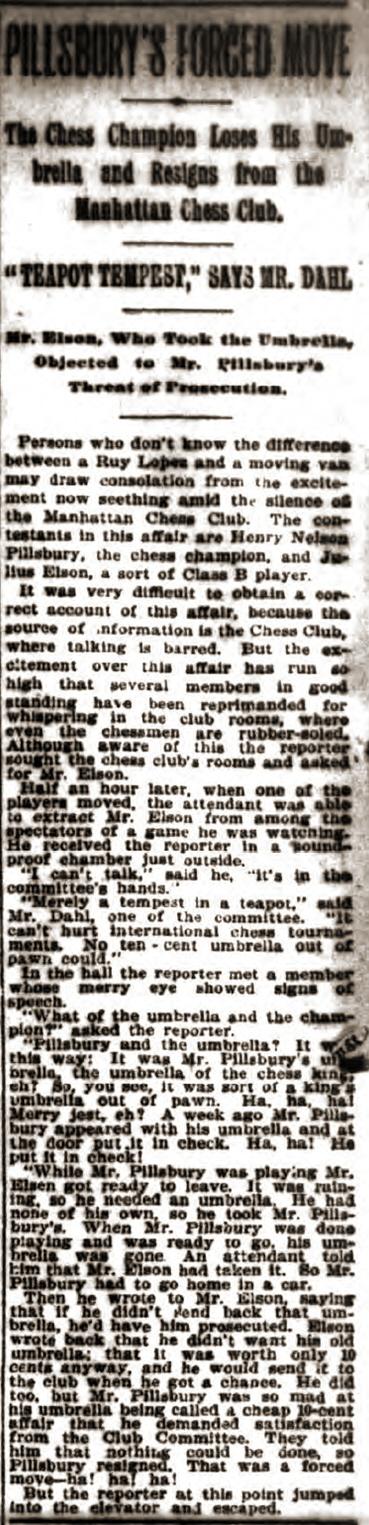

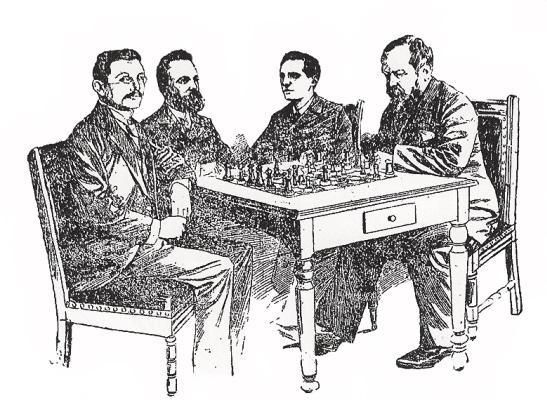

What material about Sherlock Holmes and Harry N. Pillsbury was published in 1964? Some puzzling complications arise from that apparently straightforward question.

Page 23 of An Annotated International Bibliography of Chess Articles in Non-Chess English Language Periodicals 1783-1977 by Paul Richman (Old Bridge, 1978) had the following entry:

Richard Wincor’s name is familiar to Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts. He wrote Sherlock Holmes in Tibet (New York, 1968), although that book had no chess content.

Nor have we found anything by Wincor, or about chess, in the Baker Street Journal of the time indicated by Richman.

Even so, the following appeared on page 144 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

‘Hastings, 1895 then disbanded. But everybody was talking about Pillsbury. There was amazement then that an unknown should take first prize in so powerful a field. In later years theories were to be advanced. The Spring 1964 issue of the Baker Street Journal had a learned article “proving” that the great Sherlock Holmes impersonated Pillsbury at the tournament. But this theory is not generally accepted in chess circles.’

We have found that a Holmes/Pillsbury article, entitled ‘Yet Another Case of Identity’, was printed not in the US publication the Baker Street Journal but on pages 115-118 of the Spring 1964 issue of a London-based publication, the Sherlock Holmes Journal.

Surprisingly, the author was not Richard Wincor but Harold Schonberg himself:

At present it is unclear to us on what grounds both Richman and Schonberg mentioned the Baker Street Journal, and why Wincor was named by Richman as the author of a 1964 piece on Holmes/Pillsbury entitled ‘The Sherlock Holmes Opening’. Does it really exist, in addition to Schonberg’s article of the same year on the same theme?

(5257)

See also Chess and Sherlock Holmes.

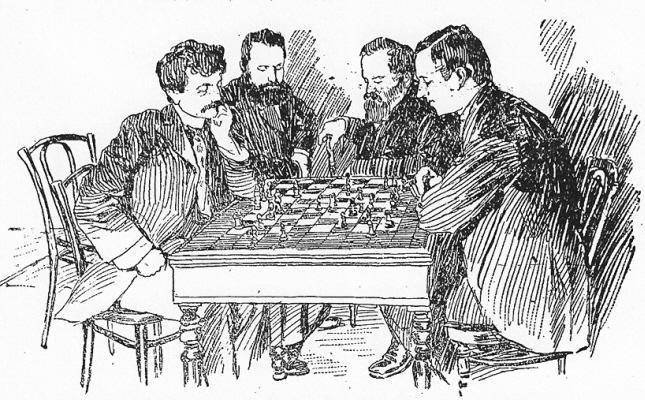

Olimpiu G. Urcan submits three sketches featuring Lasker, Chigorin, Pillsbury and Steinitz (the participants at St Petersburg, 1895-96). The illustrations are taken from the New York Tribune chess column of, respectively, 8 December 1895, 5 January 1896 and 12 January 1896.

(5713)

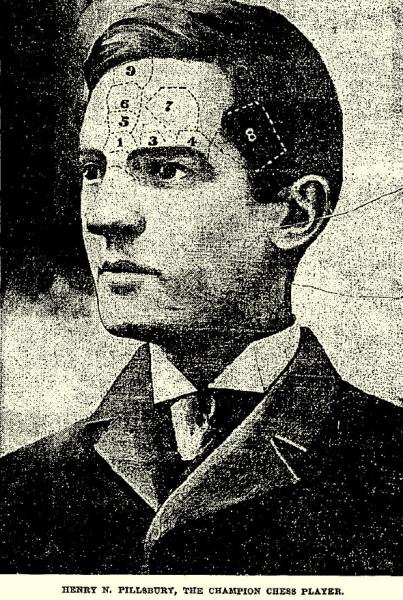

Olimpiu G. Urcan has sent us a copy of the article ‘A Phrenological Estimate of Henry [sic] Nelson Pillsbury, the Champion Chess Player’ by John L. Capen in the July 1900 issue of The Phrenological Journal and Science of Health. It is accompanied by this illustration:

The numbers are given the following meanings: 1) Individuality; 2) Form; 3) Size; 4) Order; 5) Eventuality; 6) Comparison; 7) Causality; 8) Constructiveness; 9) Human Nature. From John L. Capen’s four-page article we pass on just one dazzling discovery:

‘The expression of the countenance of Mr Pillsbury shows great mental activity.’

(5761)

James Stripes (Spokane, WA, USA) informs us that he has written an article about the origins of ‘Pillsbury’s mate’. It includes a discussion of ‘Pillsbury v Lee’, which was referred to in our feature article A Sorry Case. As Mr Stripes remarks, that alleged game was given in chapter 12 of The Art of the Checkmate by Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn (New York, 1953).

(5772)

‘Pillsbury was the first master to realize that combinations directed at the opponent’s king were affected by conditions outside of that immediate area. Control of the center was an important factor, while possession of the square B5 on the queen side (remarkable concept!) could be decisive in effecting mate on the king side. Pillsbury’s combinations were often large-scale productions, involving operations on the whole board.’

Source: Combinations The Heart of Chess by I. Chernev (New York, 1960), page 124.

(5960)

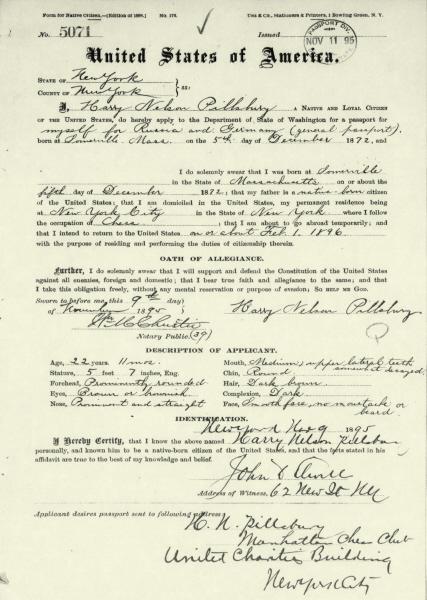

Olimpiu G. Urcan has sent us H.N. Pillsbury’s passport application, dated 1895, from the Passport Application 1795-1905 database provided by www.footnote.com.

(6267)

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) sends this article from page 334 of the 14 March 1896 edition of Black and White:

‘Ladies at Chess

By H.N. Pillsbury

Ladies have latterly invaded almost all the fields hitherto occupied by men, but at the beginning of last year they had not yet gone so far as to form a chess club for themselves. That was a state of affairs which only needed to be noticed in order to be remedied, and so the Ladies’ Chess Club came into existence in the month of January 1895. In the beginning it did not include many members, and the members, instead of spending their afternoons in paying calls, used to meet at one another’s houses and study the Royal Game. But the institution was one of the things which, since they meet a long-felt want, are bound to have a rapid success, and before long the list of members had swelled to such dimensions that it was felt to be necessary to have a club-room. This was found, and Monday evenings were devoted to the game, the afternoon visits being still kept up, until the members obtained their present premises, where the weekly meeting is held from three to half-past ten. At the Hastings Tourney, in the section for ladies, no less than seven of the offered prizes were won by LCC members, and they have done very well in their 23 matches against various London clubs. ’Tis true, they have only thrice scored victories, and only twice drawn the match; but, upon the other hand, it must be remembered that they were playing against those who have had vastly more experience than themselves. They might reasonably enough have demanded odds, but they understood that in such a pursuit as this to take a beating intelligently is to go some distance towards gaining the power to inflict a beating at some future encounter, and so they have played on equal terms.

Moreover, although two victories out of 23 matches is not a high rate of success, the record looks better if you say that in the first 20 matches the games lost were 106½, those won 79½. The success of the club as an institution has gone on increasing, and the members already number close upon a hundred. The founders have received the pleasant flattery of imitation, and their happy idea has been copied in Paris, Brooklyn, New York and other cities. There is even talk of a cable match betwixt the club and one or other of the American institutions. The present premises are at 103 Great Russell Street. Lady Newnes is President, while Mrs Bowles, as match captain, has done much to secure the successes which have been chronicled. She is also, for the present, secretary and treasurer. Miss Field is the first lady who has essayed the difficult task of playing blindfold against several opponents simultaneously. Mrs Fagan has played with success in the matches, and is an excellent composer of problems. Lady Thomas, who was the Hastings champion in the Ladies Section, is among the vice presidents. She has played as many as eight games simultaneously. One of the most promising members is Mrs James, who only began to play the game a year ago, and has already won prizes. A tournament has been proceeding with 32 competitors; and the announcement of a 50 players aside match between the Ladies Club and the Metropolitan is a testimony to the energy and enthusiasm displayed.’

An additional paragraph appeared on page 356 of Black and White, 21 March 1896:

‘The Ladies’ Chess Club concerning which Mr Pillsbury lately wrote in Black and White has added another to its list of successes, defeating the Metropolitan Club by 25½ games to 24½. Thirty of the ladies insisted on playing on equal terms with their opponents, but the remaining 20 accepted odds: six of their opponents surrendering a queen, and the others a rook or a knight. Mrs Arthur Smith writes, concerning Mr Pillsbury’s article, that there was a Ladies’ Chess Club in Brighton from 1881 till 1894, when it was merged into the St Ann’s Club.’

Pillsbury’s article was accompanied by photographs of Lady Thomas, Mrs James, Miss Field, Mrs Fagan and Mrs Bowles. The follow-up item had a drawing ‘Ladies at Chess in London’ by J. Barnard Davis.

(6902)

White played 4 g4

As mentioned in C.N. 2502 (see page 180 of A Chess Omnibus), a game beginning 1 d4 d5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bf4 Bf5 4 g4 (in which Pillsbury gave king’s rook odds to a player identified only by the initial H.) was published on pages 121-122 of the American Chess Monthly, July 1892. The game ‘was played some time ago’ and with regard to the opening the magazine said: ‘Mr Pillsbury lays claim to the invention of it, but I think its similarity to a well-known opening detracts considerably from its originality.’

The complete score as published in the American Chess Monthly:

1 d4 d5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bf4 Bf5 4 g4 Bxg4 5 f3 Bh5 6 Qd2 Nbd7 7 O-O-O c5 8 e4 cxd4 9 Qxd4 dxe4 10 Bb5 exf3 11 Nd5 Nxd5 12 Qxd5 Bg4 13 Nxf3

13...Rc8 14 Ne5 Be6 15 Nxd7 Bxd5 16 Nf6 mate.

C.N. 2502 remarked that page 266 of Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996) dated the game 1895. We add here that the book specified as its source Chigorin’s column in Novoye Vremya of 12 December 1895. The moves from 13...Rc8 to 16 Nf6 mate appeared in a note, and the game’s finish was stated to be 13...Be6 14 Qxe6 fxe6 15 Ne5 Qa5 and ‘White mates in two’.

(7098)

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

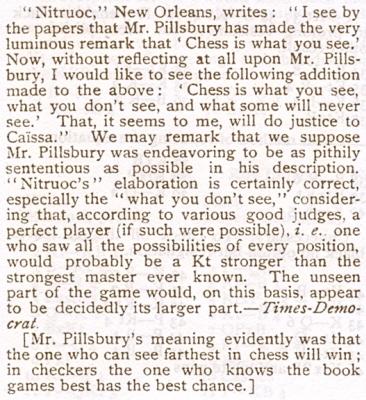

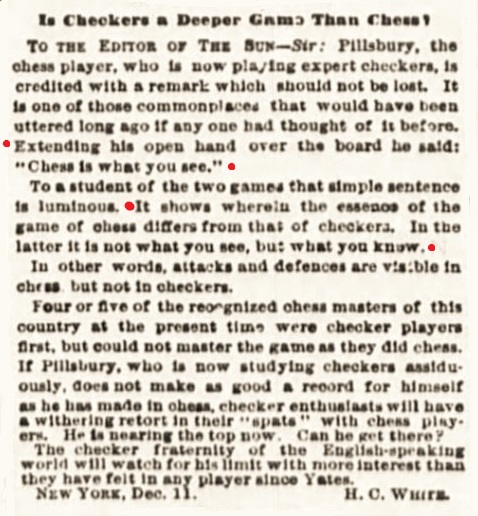

How far back is it possible to trace the quote attributed to Pillsbury ‘Chess is what you see’? The following comes from page 479 of the January 1898 American Chess Magazine:

(7122)

Jerry Spinrad sends this report from page 2 of the Ogden Standard Examiner, 16 December 1897:

(7126)

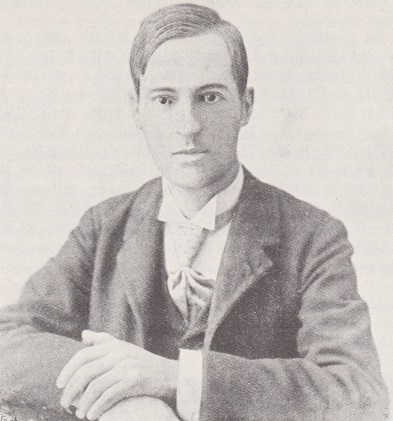

This group photograph comes from page 65 of Tempêtes sur l’échiquier by François Le Lionnais (Paris, 1981):

As stated on, for instance, page 345 of the Hastings, 1895 tournament book, H.N. Pillsbury was born in Somerville, Massachusetts on 5 December 1872, yet even today there are occasional claims that he was born in South Carolina.

In some old sources, Somerville was misspelled Sommerville. See, for example, page 3 of Harry Nelson Pillsbury. 200 partier by W. Henrici (Stockholm, 1913) and, in particular, page 188 of Die Meister des Schachbretts by R. Réti (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930). In the English edition of the latter book, Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933), the incorrect ‘Sommerville’ became the incorrect ‘Summerville’ (see page 100), leaving the reader to assume that Summerville, South Carolina was meant.

The matter was raised, with a mention of Masters of the Chess Board, by L.F. Oakley in a letter published on page 2 of the April 1944 Chess Review. The Editor’s reply noted that W.E. Napier, Pillsbury’s brother-in-law, had confirmed that Somerville, Massachusetts was the correct place. Somerville was also stipulated on page 162 of the book discussed in C.N.s 4380 and 4397, The Pillsbury Family by David B. Pilsbury and Emily A. Getchell (Everett, 1898).

(7358)

Three excerpts from Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). The figures refer to the item numbers in the Amenities work, the pages of which were unnumbered:

The only Pillsbury game in 666 Kurzpartien by K. Richter (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) is dated 1900 without any identification of the opponent or venue: 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 d6 4 Nf3 a6 5 Bc4 Bg4 6 fxe5 Nxe5 7 Nxe5 Bxd1 8 Bxf7+ Ke7 9 Nd5 mate. See page 88.

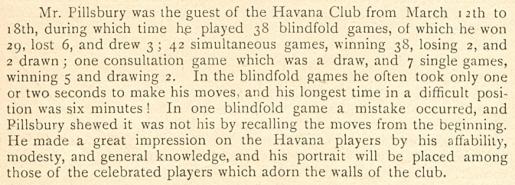

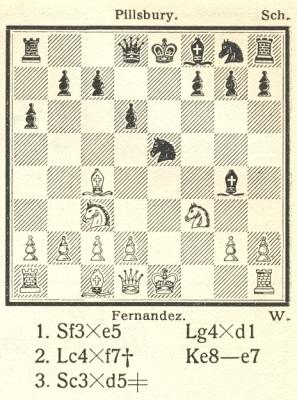

As is well-known, Pillsbury’s opponent (Black) was named Fernández, but where was the game played? There are databases which give ‘Germany’ or ‘Paris’. Page 23 of L’art de faire mat by G. Renaud and V. Kahn (Monaco, 1947) had the venue as Hanover; see too pages 13-14 of the English edition, The Art of the Checkmate.

On the other hand, the information from Renaud and Kahn about the occasion and exact date (a 12-board blindfold display on 16 March 1900) corresponds to what appeared in La Stratégie, 15 May 1900, page 133, and the Wiener Schachzeitung, January 1902, page 11.

Both magazines stated that the game was played in Havana, and Pillsbury was indeed there in March 1900. From page 231 of the June 1900 BCM:

On page 134 of his book Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1914) Franz Gutmayer blundered yet again, by indicating that Pillsbury lost the game:

(7407)

The second fascicule of Les échecs modernes by Henri Delaire, publication of which was announced on pages 167-168 of the June 1915 issue of his magazine, La Stratégie, has a number of scarce photographs, although they are under 2.5cm in width. Three examples:

Isidor Gunsberg

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Emanuel Lasker

The Lasker picture is similar to a well-known shot:

Is it possible to find better copies of the photographs which were given in Les échecs modernes?

(7429)

From a letter contributed by Edward M. Weeks of Washington, DC on pages 1-2 of the April 1944 Chess Review:

‘I lived in Boston from Nov. ’87 to Nov. ’89. I was a member of the Boston YMCU on Boylston St. and played chess there in the evenings. In the Fall of ’88, Pillsbury, then a High School student, began to play there too and at first was easy pickings for most of us. I was a B class player, but by the Spring of ’89 he could beat the best of the group who frequented the chess room at the Union.On a number of occasions Pillsbury and I walked up over Beacon Hill together, I to my room and he on his way to Cambridge. Several times I advised him against letting chess get too great a hold on him as it would interfere with his advancement in other fields.

In the late Spring of ’89, Pillsbury won a game from one of the strongest players at the Boston Chess Club which he played over for our small group at the Union.’

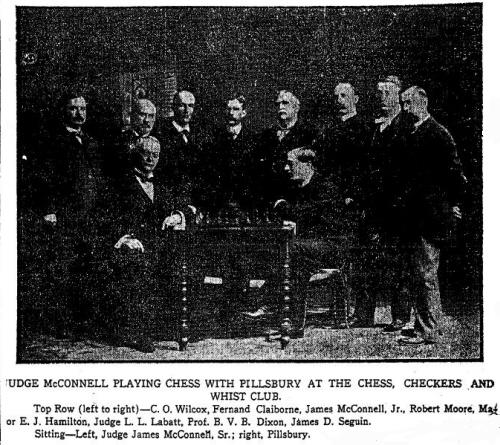

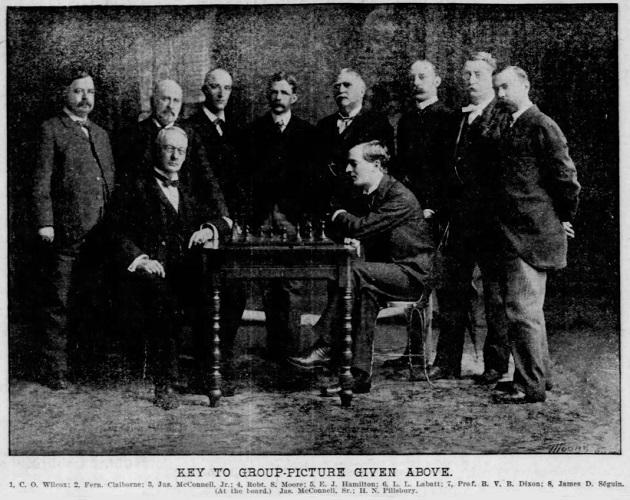

Olimpiu G. Urcan points out that this photograph appeared on page 2 of the third part of the Daily Times-Picayune (New Orleans) of 9 March 1913 (see the pdf version). The earlier (Cleveland) key did not identify the man standing on the right, but now a name is provided: M.F. Dunn.

The second group photograph in the newspaper article, which features Pillsbury, is also of much interest:

A copy of good quality is sought.

(7611)

A version of better quality is given now, from page 14 of the New Orleans Times-Democrat, 15 April 1900:

(10800)

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to Pillsbury’s account of Hastings, 1895 in an interview on page 6 of the New York Times, 29 September 1895:

‘The competing masters received me very kindly at Hastings ... especially Chigorin, Tarrasch and Steinitz, and their attitude toward me did not change at all after I had won the championship. When I had beaten Gunsberg in the final round I was applauded, and Tarrasch, Chigorin and Steinitz left their tables and congratulated me on my victory. I appreciated the honor greatly.

I felt strong as a bull when I left New York and, though I did not expect to win the championship, I thought I would be one of the first three at the end. I had not had sufficient practice, but I believed my studies and theories would aid me. I have a good knowledge of the openings, and I know how to take to aggressive movements in the middlegame stage, and I can handle the endgame very fairly. So I thought I had a good chance. I don’t know whether I would win another important tournament, but I don’t see any reason why I should not duplicate my success, for I now have additional and valuable experience and practice.

I was a little nervous when I was scheduled to play with Chigorin in my first game. I considered it hard luck, but during the progress of the game this feeling wore off and changed to mortification when I had to resign the game. I still feel sore on that point. I boiled with rage, but it stimulated me greatly for the subsequent battles. Chigorin plays a fine, dashing game. He is still unable to speak more than a dozen words of English. Owing to his splendid physique I hold him to be the strongest member of the Hastings team.

Lasker has greater analytical knowledge, but his body is too feeble to stand the strain of a long tournament. If advancing years have impaired Steinitz’s powers of crossboard play he is still as keen an analyst as ever. My game with him was the hardest I had to play in the tournament, but Tarrasch gave me a good deal of trouble. So did Tinsley.

I feel Chigorin to be the strongest player alive, so far as match playing is concerned. I should not feel at all troubled if I had to meet either Steinitz, Lasker or Tarrasch in a set match. I fancy my chess is as good as theirs, and if I should not beat either of them I feel pretty certain of not being disgraced. Neither would I fear Chigorin, as I have a good deal of confidence in myself.

There was but one player at the tournament who was younger than myself. He was Schlechter of Vienna. He is called the draw master, and he is certainly ingenious in forcing strong players to break with him on even terms. He was unfortunate at Hastings, for a series of combinations forced him to draw some games he had well in hand.

Vergani was the weakest player of the lot. He is the first Italian who has engaged in an international tournament in 32 years.

English chess men, of course, hoped Blackburne would win, and when they realized that he was defeated I think they preferred that the championship would go to a native-board American. The trouble with them is that they get to a certain point and then stand still. English masters could not afford to give odds to first-class amateurs. British women, on the other hand, are doing much better than American women. They have established chess clubs, and the game is becoming very popular among them.

I think physical training a good thing for a chessplayer before entering a tournament.

Steinitz still wants to play Lasker. He considers himself champion de jure and Lasker champion de facto, but I have left it to the Hastings Chess Club to decide who is champion, and I shall not hesitate to play him whoever he may be. The Hastings Club has already offered a purse for such a match. I shall not challenge the winner of the Lipschütz-Showalter match to be played here. I shall not claim any title, but shall simply stick to business. Then if I can get any I shall go to St Petersburg in November to play in the quintangular tournament ...

I owe my success ... to the application of certain new theories which I had evolved about the game. I studied them a year and a half and found, when the time came, that they were practical. As a matter of fact, I consider myself more advanced in theory than in practice.

If I go to St Petersburg in November I will probably remain in Europe until Spring, when there will be another tournament at Hastings.’

(7760)

Very similar views by Pillsbury about Chigorin and Lasker were quoted on page 395 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves from page 472 of the November 1895 BCM.

Further to C.N. 5164, mention may be made of this book cover with a reversed image:

(7860)

As noted in Historical Havoc the book misspells a) La Stratégie 16 consecutive times on pages 335-338, and b) Wiener Schachzeitung 16 consecutive times on pages 343-346.

John Blackstone points out an article ‘Chess Playing as a Profession for Women’ by Nellie M. Showalter in the Los Angeles Herald, 6 February 1898, page 24. It includes two sketches of H.N. Pillsbury:

(7877)

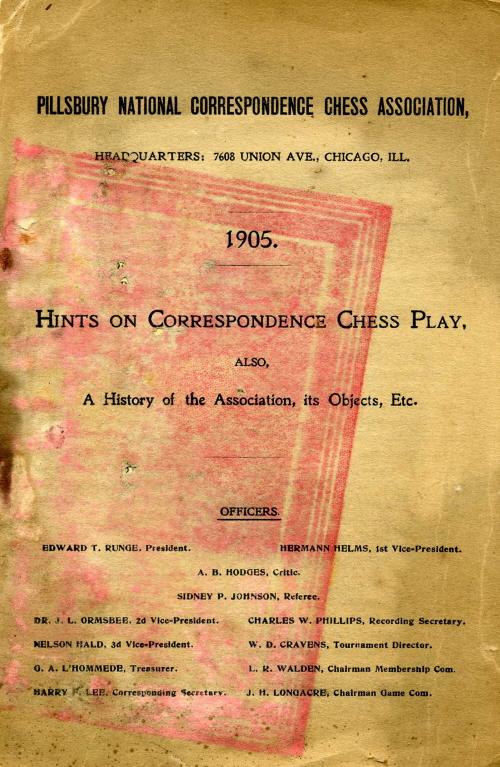

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) comes information about a scarce publication in his collection, a pamphlet produced by the Pillsbury National Correspondence Chess Association in 1905:

Mr Clapham writes:

‘The pamphlet has 12 pages, including the covers, and begins with a short history of the Association which states that it was founded in 1896 and was named as “a tribute to our master player Harry N. Pillsbury”. There follows a list of the accomplishments (two) of the Association and details of how its tournaments were arranged.

The second half of the publication has two articles, of about three pages each, giving general advice and recommendations on correspondence chess play. These are by the Reverend Leander Turney and Walter Penn Shipley.

There are no games, but the pamphlet does state that bulletins will be issued containing notable annotated games.’

(8002)

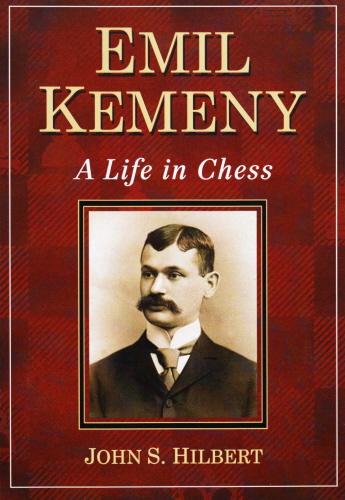

The series of scholarly monographs from McFarland & Company, Inc. continues with Emil Kemeny A Life in Chess by John S. Hilbert.

Pages 228-229 have an exhibition game, new to us, which may be of theoretical interest today:

Emil Kemeny – Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Franklin Chess Club, Philadelphia, October 1899

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Nd6 6 Bxc6 dxc6 7 dxe5 Nf5 8 Qxd8+ Kxd8 9 Nbd2 h6 10 b3 Be6 11 Bb2 Be7 12 Ne4 b6 13 c4 Kc8 14 h3 g5

15 Nd6+ Bxd6 16 exd6 Rg8 17 dxc7 Kxc7 18 g4 Ne7 19 Nd4 Bd7 20 f4 gxf4 21 Rxf4 f5 22 Re1 Ng6 23 Rff1 fxg4 24 Ne6+ Kc8 25 hxg4 Nh4 26 Kh2 Rxg4 27 Rf8+ Kb7 28 Rf7

28...Rag8 29 Rxd7+ Kc8 30 Rd3 Rg2+ 31 Kh3 Rxb2 32 Kxh4 Rxa2 33 Nf4 Rh2+ 34 Nh3 Rd8 35 Ree3 Rxd3 36 Rxd3 a5 37 Kg3 Rc2 38 Nf4 a4 39 bxa4 Rxc4 40 Ra3 Kb7 41 Ne6 Ka6 42 Nd8 Ka5 43 Rb3 b5 Drawn.

The book includes Kemeny’s annotations from the Philadelphia Public Ledger, 25 October 1899.

(8114)

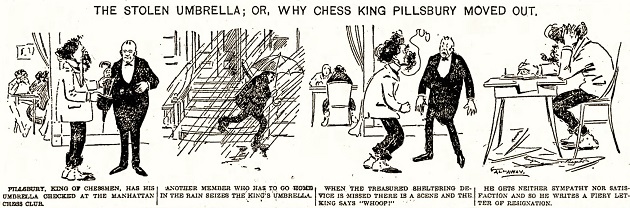

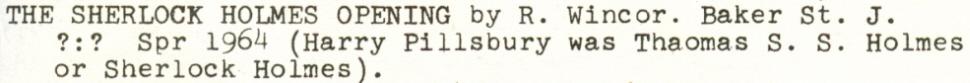

Page 152 of the August 1892 American Chess Monthly:

The solution was on page 268 of the December 1892 issue:

(8333)

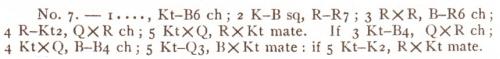

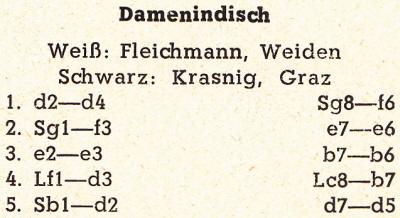

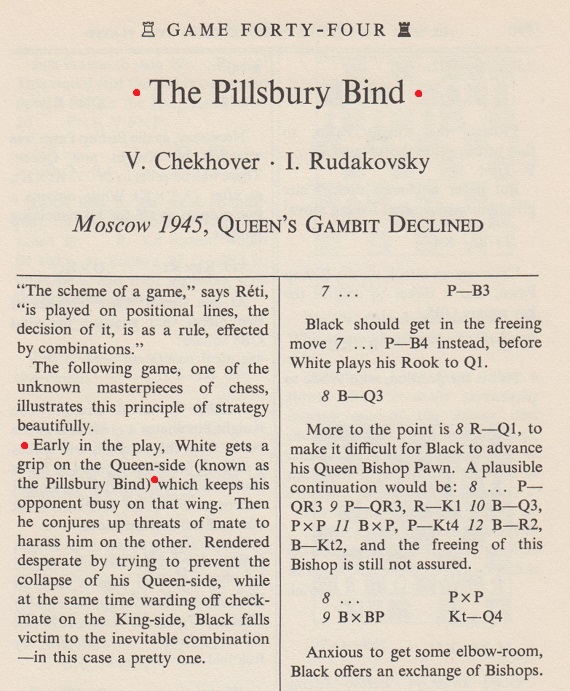

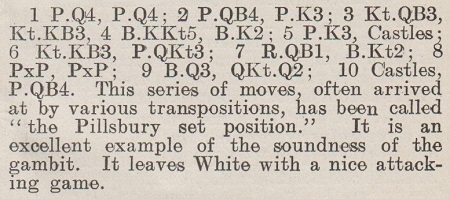

‘The player who achieves the happy arrangement of pieces known as the Pillsbury attack may then sit back and relax. So powerful is this system that the game will play itself!’

So wrote Irving Chernev on page 382 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955):

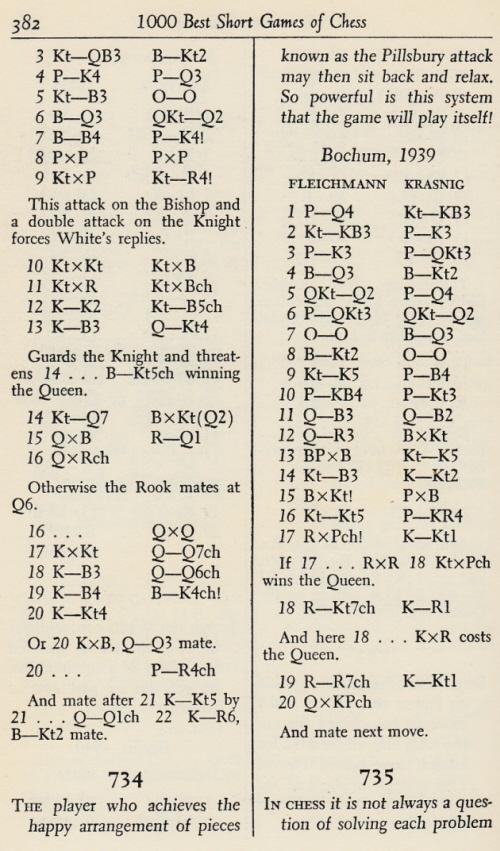

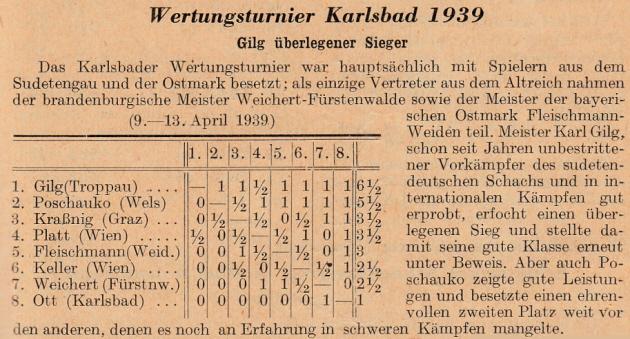

Verification is sought regarding the players’ names and the occasion. There was a win by Fleischmann against Kraßnig at Carlsbad, 1939, as shown by the crosstable on page 137 of the 1 May 1939 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter:

(8699)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) notes that the game in C.N. 8699 was published on pages 151-152 of the 5 July 1939 issue of Schach-Echo. The heading: