Edward Winter

‘I had a toothache during the first game. In the second game I had a headache. In the third game it was an attack of rheumatism. In the fourth game, I wasn’t feeling well. And in the fifth game? Well, must one have to win every game?’

Anyone using a search-engine for that remark, or a slightly different wording, will be presented with countless webpages. Most ascribe the comment to Tarrasch, some to Tartakower, and none to a precise source.

In print, it is no surprise to find A. Soltis writing the following sourcelessly on page 11 of Chess Life, June 1990:

‘And it was Tartakower who had perhaps the final word on excuses. Asked how he could lose so many games in a row at one tournament he replied: “I had a toothache during the first game, so I lost. In the second game I had a headache, so I lost. In the third game an attack of rheumatism in the left shoulder, so I lost. In the fourth game I wasn’t feeling at all well, so I lost. And in the fifth game – well, must I win every game in a tournament?”’

An earlier version was related by Harry Golombek on page 91 of the April 1953 BCM in a report on that year’s tournament in Bucharest, at which he ‘had a really dreadful phase’:

‘If asked to account for these six successive losses I think I cannot do better than to quote Dr Tartakower who on a similar occasion was explaining why he lost five games in a row in an international tournament. “The first”, he said, “I lost because of a very bad headache; during the second I didn’t feel at all well; I was afflicted by rheumatic twinges throughout the third; in the fourth I suffered acute toothache; and the fifth – well, must one win every game in a tournament?”’

Readers may care to imagine themselves entrusted with editing a chess quotations anthology. What to do with this ‘final word on excuses’? Omit it owing to the lack of a source? Give in detail the various versions and attributions? Plump and hope for the best (the process described in C.N. 9887)?

An attempt may first be made to establish when, if ever, Tartakower or Tarrasch lost five consecutive tournament games, and when the story was first attributed to, if not voiced by, either of them.

See also Excuses for Losing at Chess.

(11994)

C.N. 11994 invited readers to imagine themselves as the editor of a chess quotations anthology faced with handling a remark attributed, in various wordings, to both Tarrasch and Tartakower. Now, let readers see themselves as the editor of a single-volume chess encyclopaedia and having to decide what date of birth to give in the entry on Samuel Reshevsky.

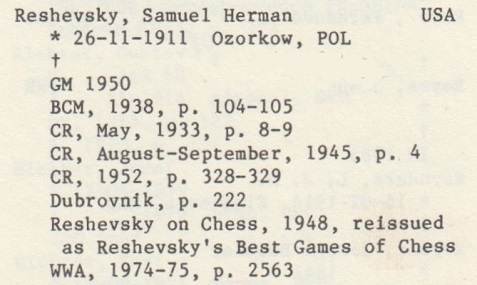

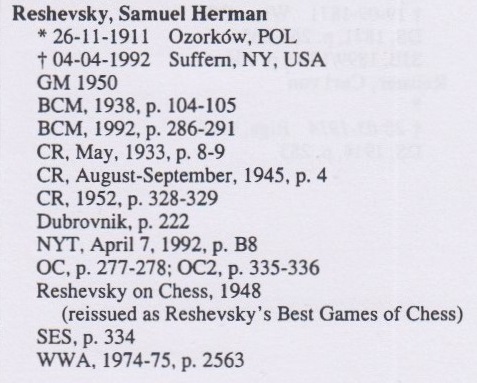

The natural course may be to follow Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) and take the precaution of also checking the privately circulated 1994 edition:

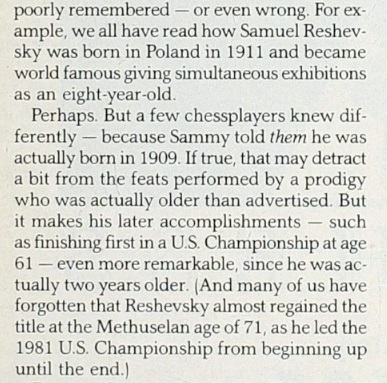

‘26 November 1911’ is in both editions, but the encyclopaedist may worryingly recall an article by Andrew Soltis on pages 10-11 of the August 1992 Chess Life:

From C.N. 1943:

On page 10 of the August 1992 Chess Life Andy Soltis wrote that Reshevsky had told a number of chessplayers that he was born in 1909, and not 1911 as commonly believed.

Page 202 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves added a footnote:

However, in an interview with Hanon Russell in August 1991, Reshevsky insisted that he had indeed been born in 1911.

C.N. 11199 reverted to the subject:

... a claim emerged in the early 1990s that Samuel Reshevsky was born in 1909 and not, as commonly accepted, in 1911.

The matter is discussed by Bruce Monson in an article about Reshevsky on pages 46-55 of the 1/2019 New in Chess.

Here, we quote the start of Monson’s investigation of the birth-date matter (page 51):

‘But in the 1990s other information started percolating to the surface, no doubt in the wake of Sammy’s death on 4 April 1992. In the August 1992 Chess Life Andy Soltis revealed that Reshevsky had told a number of chessplayers that he was actually born in 1909 and not in 1911. Unfortunately, Soltis did not identify these individuals. However, it is plausible. Reshevsky was known on occasion to inadvertently spill the beans about other “secrets” from his past, such as the assertion that he had never studied chess as a child, which is simply not true, only to later try to shove the genie back in the bottle.’

Difficult to summarize, Monson’s article is important and should be read in full. It contains both documentation and speculation, marked as such. One image is a Łódź registration card dated 1919 which indicates that Samuel Reshevsky was born in 1909 (with no exact date). Using this and other materials and inferences, Monson wrote on page 53 of the New in Chess article:

‘Conclusion: Reshevsky’s birthday should – at the bare minimum – be adjusted to 26 November 1909. And in all probability his actual date of birth was 26 May 1909, adding an additional six months to his age.’

What, then, should our hypothetical encyclopaedist put in the Reshevsky entry?

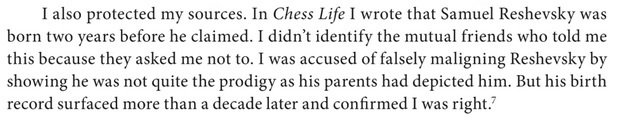

Andrew Soltis has a new book out, a chess memoir entitled Deadline Grandmaster (Jefferson, 2024). Page 246, which can be viewed online, includes the following:

Some obvious questions:

1. ‘In Chess Life I wrote that Samuel Reshevsky was born two years before he claimed.’ Where in Chess Life? Certainly not on page 10 of the August 1992 issue, where, as shown above, Soltis mentioned the 1909 date merely as a possibility derived from hearsay.

2. ‘I was accused of falsely maligning Reshevsky.’ By whom, where and when?

3. ‘His birth record surfaced more than a decade later and confirmed I was right.’ Where and when? And more than a decade later than what?

4. The Deadline Grandmaster text shown above ends with a superscript 7. This leads to the ‘Chapter Notes’, where, on page 356, note 7 reads (in full):

‘New in Chess, Issue 1, 1999.’

Why put that? Issue 1, 1999 of New in Chess has nothing about Reshevsky’s date of birth.

Addition on 2 October 2024:

From Marek Soszynski (Birmingham, England):

‘I believe I was the first to discover and publish evidence that Reshevsky was born in 1909, which I presented in my book The Great Reshevsky: Chess Prodigy and Old Warrior (Forward Chess, 2018). Bruce Monson briefly references my findings in his article, and explained to me at the time that the brevity was due to editorial cuts by New in Chess. My later book, Rare and Ruthless Reshevsky (MarekMedia, 2023), does not revisit the birthdate issue.’

(12035)

Having previously asked readers to imagine themselves as the editor of a chess quotations book (C.N. 11994) and of a single-volume chess encyclopaedia (C.N. 12035), we now invite them to assume the role of a mainstream journalist commissioned to produce a chess article on recent allegations of online cheating. Where to look for the essentials? Where to find output in which opinions, biased or not, do not leap-frog over facts?

The journalist may dive in at some random point proposed by Google, only to find barely comprehensible arguments deployed with links to barely comprehensible X/Twitter posts or YouTube videos, as various parties and partisans compete with declarations, interrogations, accusations and insinuations. But where are a placid, objectively formulated overview and chronology of how any given point was reached? In brief, where is the journalism?

This is not new. Nearly a decade ago, Nigel Short wrote in New in Chess about the differences between male and female chessplayers, and an outcry ensued, unhurriedly. If a journalist today seeks a reminder of the case, where to go? Should Google prove unhelpful, it may seem sensible to turn to a ‘standard’ source such as the Wikipedia entry on Short, but that fails too. It has 70 words on the affair and three endnotes, all three being links to ‘outcry’ articles by non-specialist writers in three UK newspapers, the Independent, the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph; all three articles, as it happens, were dated 20 April 2015. The New in Chess piece had been published about a month previously.

Wikipedia does not relate what Short had written in New in Chess, even though the full text was reproduced by ChessBase not long after the tumult began, and is still there. Nor does Wikipedia display awareness of Short’s follow-up article in New in Chess, which was, in part, a reply to the assertions in the three UK newspapers. The media had gorged themselves and, in terms of actual arguments, the second New in Chess article was, so to speak, even more ignored than the first one. Vive l’indifférence.

That was the shallow treatment of a controversy in 2015, and one looks in vain, even today, for a plain, factual account of it. How will the media of 2024 be judged in future years for their handling of the present cheating cacophony? Who will emerge with honour for showing care over facts and respect for fair play? Who will work hard to clarify the issues for the public’s benefit? And when will the process start?

Addition on 14 November 2024:

An example of how the public record may be skewed is provided by the reaction, or lack thereof, to Nigel Short’s follow-up article (‘A Beautiful Minefield’) on pages 36-37 of the 4/2015 New in Chess, where he wrote, for instance:

‘On 20 April an article appeared in The Daily Telegraph entitled “Nigel Short: Girls Just Don’t Have the Brains to Play Chess”. Never mind the fact I didn’t say that, it was a catchy headline to set me up as a misogynist pantomime villain. In extraordinary rapid succession came a whole series of similar articles, in The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, many with totally fabricated quotes and grotesque distortions – such as the Daily Mail’s “Women aren’t smart enough to play chess because the game requires logical thinking, says British Grandmaster”, despite me having said nothing at all about logic.’

C.N. 9344 quoted that rebuttal, but where else can it be found on the Internet? We see only one place, at the English Chess Forum, where, on 18 December 2020, Short reproduced the full text of ‘A Beautiful Minefield’.

(12060)

Further to the role-playing exercises in C.N.s 11994, 12035 and 12060, readers are now invited to imagine themselves investigating supposed measures to ban chess in the Middle Ages, including, for example, oft-told stories about Bishop Guy of Paris having a chess board which was disguised by being folded.

Finding nothing in H.J.R. Murray’s books and articles, the investigator may try a search engine, the dubious reward being a plethora of similarly worded paragraphs such as this:

‘In 1125, Bishop Guy of Paris banned chess and excommunicated a few priests who were caught playing chess. A chess enthusiast priest then devised a secretive folding chess board. Once folded, it looked like two books lying together.’

That is merely a sourceless item on a sourceless Bill Wall webpage. Instead, Google Books may seem promising since it offers relevant (though not perfectly matching) texts, such as the following:

That passage is on page 348 of the 6 May 1865 issue of All the Year Round, ‘a weekly journal conducted by Charles Dickens’. With C.N. 12043 (‘figurehead romanticism’) in mind, no excited suggestion can be made that the article, entitled ‘Chess Chat’ and published on pages 345-349, was by Dickens himself. All the Year Round articles were usually anonymous. But who did write it, and on what historical basis?

With such questions unresolved, one’s eye may well be drawn to the last two paragraphs of the article, which abruptly move on from chess history to some general criticism of the game:

‘To play well at chess – “Cavendish” opines – is too hard work. It is making a toil of a pleasure. We resort to games as a relief, when we have already experienced enough – perhaps more than enough – brain excitement. Under those circumstances, we do not desire severe mental exertion, but rather repose of mind, which is not promoted by engaging in a contest of pure skill. To take up chess, as an amusement, after mental labour, is to jump out of the frying-pan into the fire. Chess, well played, is no relaxation, and ought not to be regarded as a game at all. It is not a game with first-rate performers, but the business of their lives. Chess is their real work; ordinary engagements are their relief. Sarah Battle “unbent” over a book.

But for what is all this intellectual tension, this toil and trouble, this stretch of thought? Simply to fill an otherwise unoccupied portion of human life. “Labour for labour’s sake”, says Locke, “is against nature. The understanding, which, as well as the other faculties, chooses always the shortest way to its end, would presently obtain the knowledge it is about, and then set upon some new inquiry.” But chess affords no information, leads to no purpose, effects no result, leaves no trace. It is a beautiful piece of mechanism, conducing to nothing. When the number of known combinations, problems, and solutions, shall have been increased a hundred-fold, the world will not be a jot the happier, the wiser, the better, or the richer. Those who like thus to occupy their leisure, have a perfect right so to do. If their striving and straining do no good, at least it does no harm. But it is difficult not to say to one’s self that the total amount of effort bestowed on chess, say only within the last hundred years, might have sufficed to gird the world with trans-oceanic telegraphs, or to work out the means of aërial locomotion.’

And so now there are two puzzles on the go: the origin of the religious claims and the authorship of the criticism of chess. For both matters, further burrows beckon, and C.N. readers’ company and assistance will, as ever, be appreciated.

(12110)

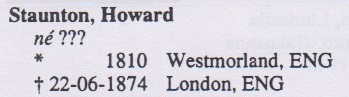

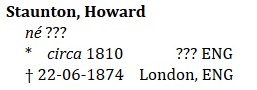

C.N.s 12116 and 12127 prompt an addition to Predicaments for Chess Writers: the task of writing just a factual line or two about Howard Staunton’s early (pre-chess) years.

(12140)

Addition on 29 May 2025:

In C.N. 12149 John Townsend (Wokingham, England) examined the available evidence about Staunton’s early life, noting that his place of birth is uncertain and that, even, ‘it may be a mistake to assume that Staunton was born in 1810’.

In that case, the start of the entry in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (1987 and 1994 editions) ...

... might be pared down further:

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.