Edward Winter

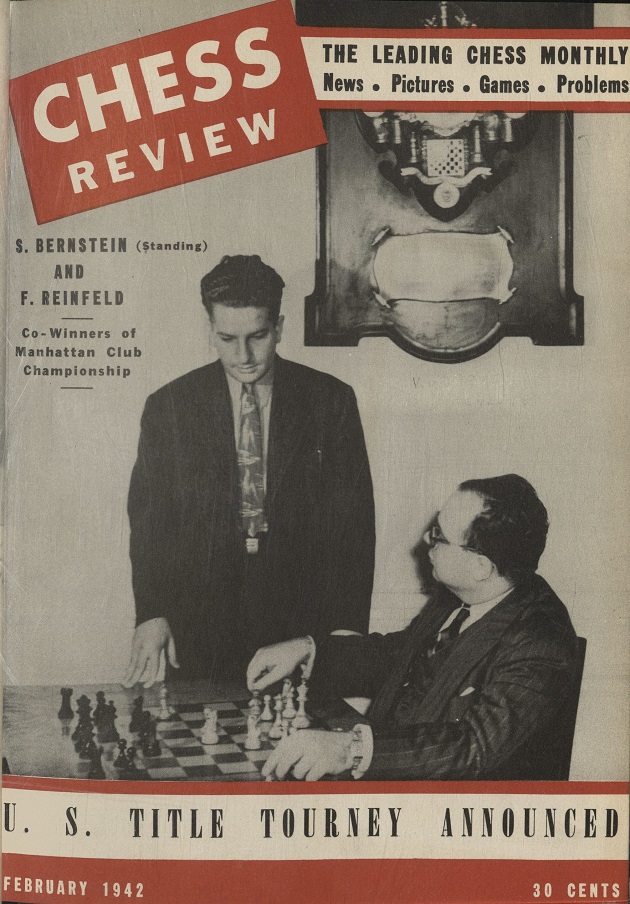

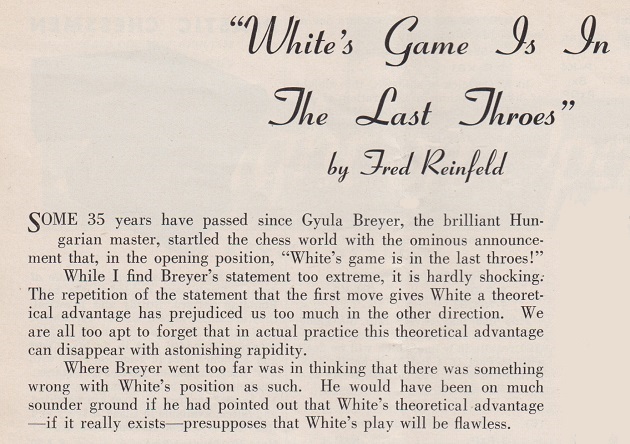

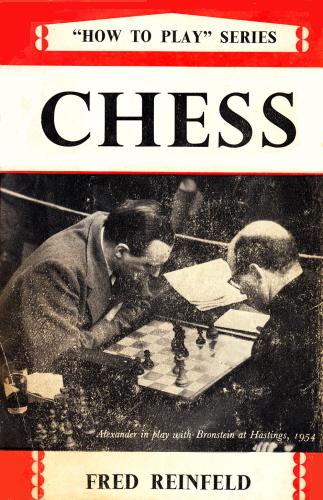

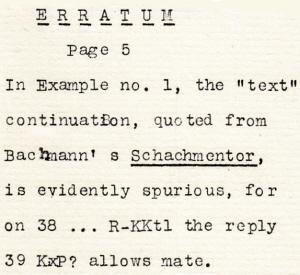

Fred Reinfeld, Chess Review, February 1952, page 41

***

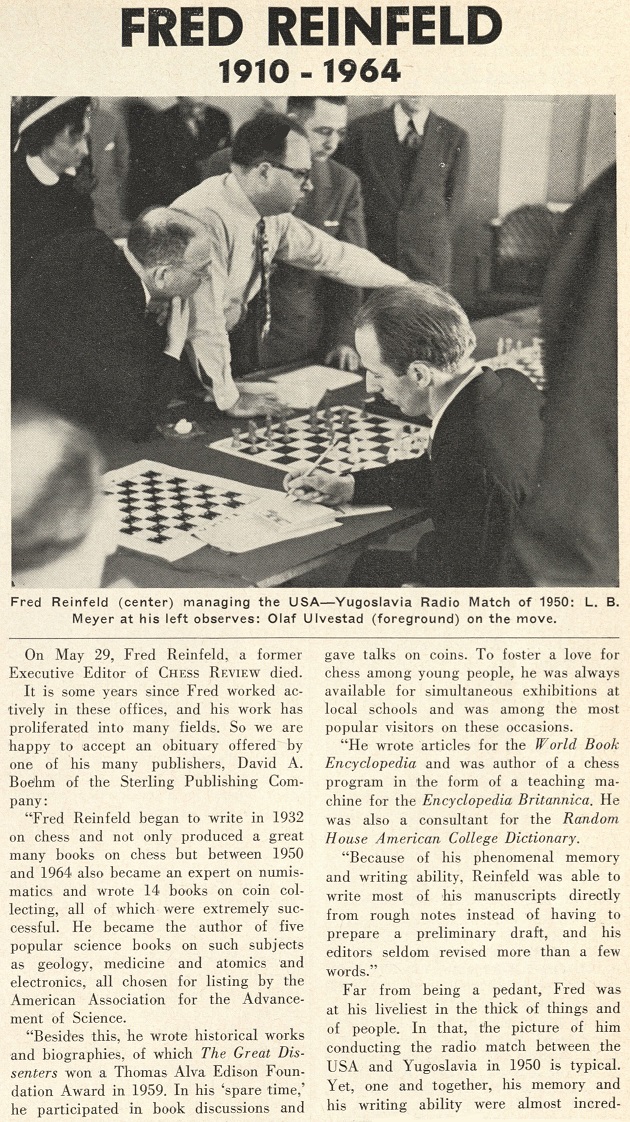

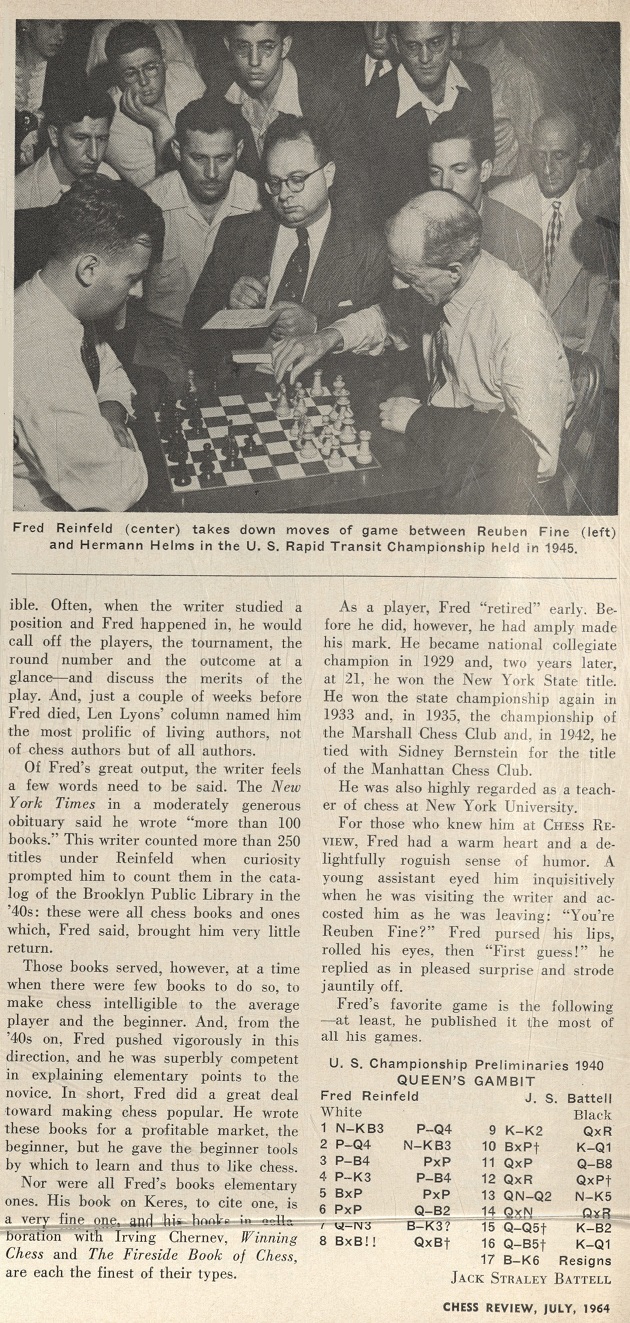

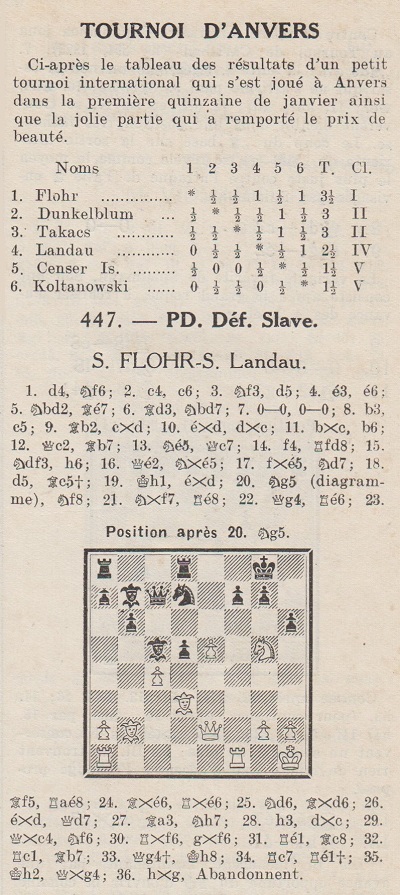

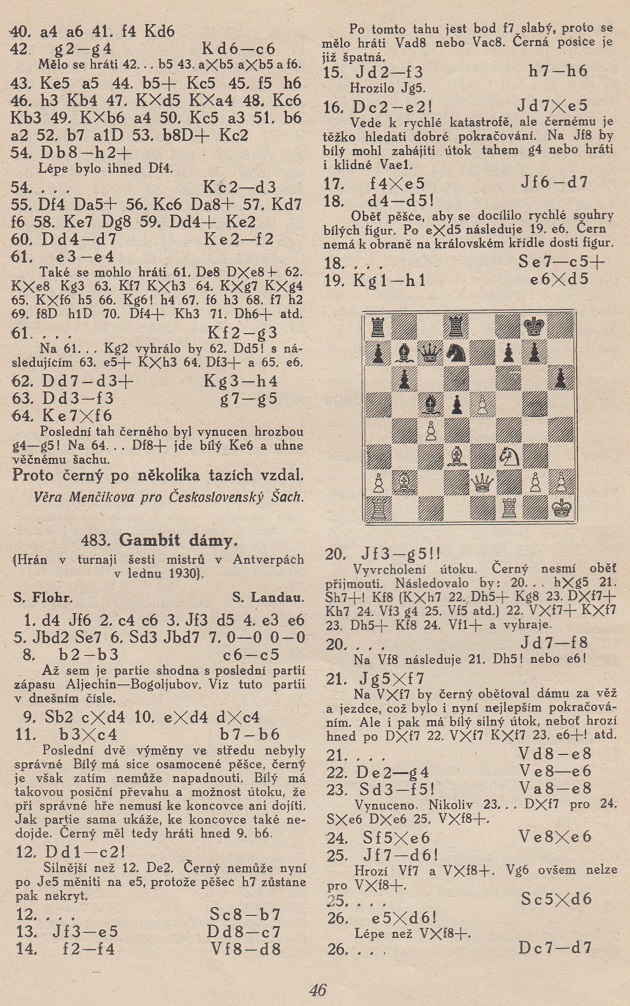

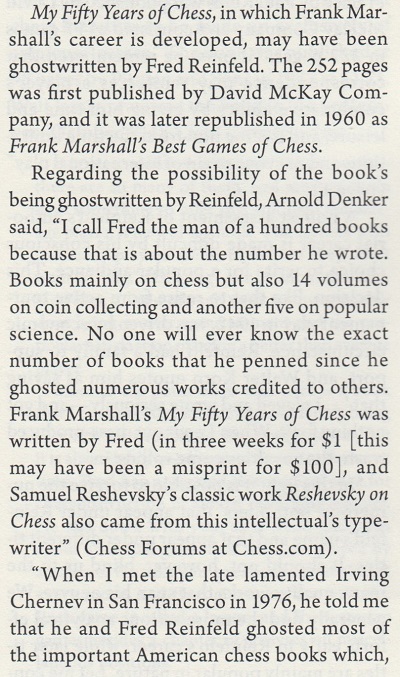

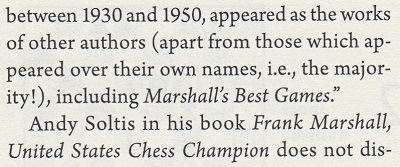

From pages 193-194 of the July 1964 Chess Review:

W.D. Rubinstein (Victoria, Australia) writes:

‘When I met the late lamented Irving Chernev in San Francisco in 1976, he told me that he and Fred Reinfeld ghosted most of the important American chess books which, between 1930 and 1950, appeared as the works of other authors (apart from those which appeared over their own names, i.e. the majority!), including Marshall’s Best Games. (Marshall, according to Chernev, was incapable of writing a coherent page, at least by the 1930s.) Can anyone identify any other important chess “ghosts”?’

(341)

Sidney Bernstein (Brooklyn, NY, USA) informed us on 25 September 1986:

‘I was a close friend of Reinfeld – and, for what it’s worth, he confided to me that he had indeed written the Reshevsky book [Reshevsky on Chess]. (He was, as you may well have surmised, a prolific ghost-writer – and “did” other books by great players, including Frank Marshall.) Marshall, incidentally, was a delightful, lovable gentleman as well as a chess genius.’

(1273)

From Harry Golombek’s column in The Times (Saturday Review), 29 October 1977, page 11, in a discussion of My Fifty Years of Chess by F.J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

‘I have been told he did not in fact write the book but that it was written for him. In any case one must assume that even if he did not actually write the work he told someone else what to write.

It is odd how this tradition of deputing other people to write one’s books seems to have flourished in America since Marshall was followed in this practice by two of the most outstanding of his successors as United States champion, Sammy Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer. It is also a little odd if indeed Marshall did descend to this practice since I gained the strong impression when I met him that he was one of the most honest and sincere of all grandmasters.’

(9834)

Reinfeld and Bernstein eventually fell out, as the latter explained to us in a letter dated 15 October 1988:

‘I was working for Fred as an analyst (chess) in the 1950s. After some time he complained about my work. That upset me, which was noticed by my wife (a Russian Jewish lady who was a fairly good player). Unbeknownst to me, she wrote him an unfriendly note – whereupon there was no further friendship or collaboration between us (Fred and myself, I mean). He was a brilliant man, and we had been fast friends. The above explains why I’ve never known what was behind the break between him and Horowitz. I have no details whatever about the indubitable rift between them.’

A number of C.N. readers’ views of Fred Reinfeld were quoted in C.N.s 473 and 522:

C.D. Robinson (Toronto, Canada):

‘Reinfeld-bashing seems fashionable. I doubt if his critics have together contributed one-tenth of the enjoyment and instruction that have been derived from his books.

Reinfeld produced at least three books of lasting value, and that is more than can be said for most chess writers. The Treasury of Chess Lore remains an entertaining anthology, and The Unknown Alekhine is invaluable. The Human Side of Chess (aka The Great Chess Masters and Their Games) is the third. It becomes sketchy towards the end (deadline imminent?), and Reinfeld is sometimes dead wrong, as when he asserts that Alekhine’s style became dull and laboured from 1932: yet no other writer has produced accounts of Morphy, Anderssen, Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine which surpass the overall quality of these chapters by Reinfeld. There is no documentation, but this is true of virtually every historical or biographical chess book. The exploration of Alekhine’s psychology, for example, is excellent. After seven years of research, I can but agree with it.’

Frank Skoff (Chicago, IL, USA):

‘Reinfeld did produce some first-class books (Warsaw, 1935, for example; Cambridge Springs, 1904 too); but like A. Conan Doyle, he discovered that such well-done works were not financially successful. His publishers talked him into doing potboilers instead, and these proved very popular, so much so that Reinfeld was forced on the treadmill of continuing to turn them out as his publisher pestered him for more and more of the same.’

Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, PA, USA):

‘I would like to offer what might be called a Reinfeld Defense. As you know, the life of Alekhine offers a superabundance of contradictions and inaccuracies. Early in my avocation, I put together a dozen pages on Alekhine’s life simply to lay out the contradictions, the sources, and non-chess accounts. When my reckoning was finished (I won’t say completed), Reinfeld’s account of Alekhine stood up the best. I expect that Pablo Morán’s biography has well superseded Reinfeld’s, but my ignorance of Spanish prevents me from offering even a tentative judgement.’

Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘Reinfeld never wrote a bad chess book in my opinion, but he wrote precious few that made any contribution to chess knowledge. His later books were potboilers but he seemed to have written with such impetus that even death only slowed down rather than ended his output. I give good marks to The Human Side of Chess which, despite its many errors in all chapters, is a model of accuracy when compared to Schonberg’s Grandmasters of Chess. What I don’t understand is why you say [in the list (C.N. 473) given below] it is absurd to claim that Morphy was better read than Capa. M. had read everything published in book form from c. 1830 and knew most of the games by heart. His ability to quote complete games published years earlier frequently amazed (and no doubt demoralized) his opponents.’

(We confess that we have never looked upon Morphy as a bookish

person. Lawson’s biography quotes Charles Maurian as saying that

Morphy, during his college days, scarcely gave chess a thought and

had only three or four books. We have not traced references to

Morphy’s reading widely later in life either. Can readers provide

any other quotes to indicate how much/little Morphy studied

chess?) [See C.N. 1328 below.]

After the Morphy digression we return to Reinfeld, and Fred Wilson (New York, NY, USA):

‘You must know that Reinfeld was very envious of Capa’s great natural talent; as a basically mediocre master, Reinfeld (who did beat Reshevsky twice and draw once with Alekhine) achieved whatever he could over-the-board through sheer hard work and he could not imagine that someone with Capa’s ability would be so unwilling to do any real studious effort to maintain his position at the top of the chess world.

Speaking of Reinfeld, I have always thought it was obvious he wrote Reshevsky on Chess – just compare the style of writing with any of the books Sammy really wrote! Also, Reinfeld wrote My Fifty Years of Chess in about three weeks for 100 dollars (Marshall’s book!) Irving Chernev told me this himself about six months before he died (he said he couldn’t believe it when Carrie Marshall asked him what he thought of Frank’s book!) Again, if you compare the semi-literate Marshall’s earlier writing with My Fifty Years ... you will see the difference.

Reinfeld had a clear, if somewhat pseudo-intellectual, style (he would have been a great “trashy” or melodramatic novelist, I think) which could be quite entertaining. The “good” Reinfeld left us with Colle’s Chess Masterpieces, Cambridge Springs, 1904, Reshevsky on Chess (!), Tarrasch’s Best Games (admittedly much stolen out of “300 Chess Games”), etc. etc., while the “bad” Reinfeld did many awful beginners’ books. But he had (and has) a great impact, especially on new enthusiasts, and the chess world would have been much poorer had he never lived. The difference between Reinfeld’s and Schonberg’s knowledge and appreciation of the greatest chess champions is very marked; one is clearly only a moderately informed “fan” while the other is obviously a devoted expert. Reinfeld says in his preface that he is at times subjective (so am I, in my book) but I think this is fair when someone has interesting opinions worth sharing.’

Frank Skoff quotes from Walter Korn in America’s Chess Heritage, page 127, which gives an interesting view on Reinfeld:

‘His writing was aided by a phenomenal memory for master games, and by intensive adherence to a work schedule which enabled him to pour out his stream of books in quick succession, Too often, though, his pace made it impossible to sustain the excellence of his earlier titles, and he became repetitious. After his death, many sections from his books were over and again reprinted by various paperback publishers, often under changed titles.

When I spoke to Reinfeld in 1950, I questioned him about the contrasting quality of his early and late writing. He said: “In those days I played and wrote seriously – and got nothing for it. When I pour out the mass-produced trash, the royalties come rolling in.” Reinfeld agreed when I asked, “But you lost a pastime?”’

From James J. Barrett (Buffalo, NY, USA):

‘In C.N. 522 you ask: “Can readers provide any other quotes to indicate how much/how little Morphy studied chess?” How about this from Fiske to Allen, 16 November 1857: “He knows everything in the books thoroughly and can play over for you the games of M’Donnell, Staunton, Von der Lasa, Kieseritzky etc. by the week.” The full text of this letter is only to be found in H.S. White’s Willard Fiske – Life and Correspondence (New York, 1925). There are several excellent letters from Fiske to Allen in this volume, containing Fiske’s observations about Morphy at the time of the New York, 1857 Congress, and they are to be found nowhere else. I urged Lawson to include them in the appendix of his book, but he chose not to. Probably he ran out of space after the Holmes speech, the Staunton letters, etc. ...’

(1328)

The Complete Chess Course by Fred Reinfeld (Unwin Paperbacks, London, 1983) is a compendium of six separate books pasted together to offer a single volume that is good value, if confusing reading.

At a time when 1...a6 is being accorded serious theoretical consideration and Kasparov’s famous remark ‘Chess is not skittles’ is being unfavourably received in the context of 1 c4 g5, it is quaint to read some of Reinfeld’s flat statements on the openings:

Surely even beginners should not be deceived to this extent. And talking of deception, the publisher’s blurb tries hard to make out that Reinfeld is still alive, while darkly calling him ‘a former chess master’.

(499)

‘To the lover of beautiful chess, a draw is a very distasteful thing.’

Fred Reinfeld on page 123 of Great Moments in Chess, and quoted on page 109 of the April 1967 BCM.

(561)

C.N. 1496 quoted without comment this passage from page 2 of Morphy Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld and A. Soltis:

‘Paul Morphy was a Herculean figure in his day, and his fame has not suffered with time. He was not just the first American to triumph over representatives of the Old World at chess. He was the first American to achieve a position of world superiority in any field.’

We now note the following text from page 142 of Checkmate, May 1904:

‘In a recent letter to a New York journal Mr F.M. Teed called attention to the fact that America won the yachting and chess primacy of the world about half a century ago. The old cup, he says, is still here, and even those who don’t care for yachting (or, like him, can’t afford it) are always pleased to hear of another win for Columbia or Reliance.’

(3062)

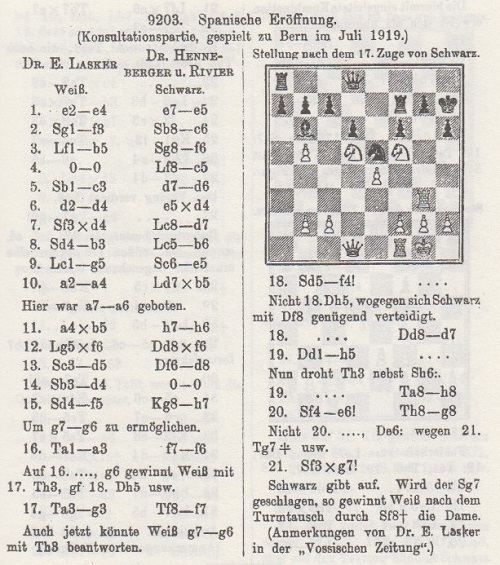

Most readers will be familiar with the Reinfeld/Fine book Dr Lasker’s Chess Career, Part I: 1889-1914 (London and New York, 1935), reprinted in 1965 by Dover under the title Lasker’s Greatest Chess Games 1889-1914. Part II was never published, but a manuscript may still exist. As quoted in C.N. 1500, Reinfeld wrote in the October 1948 CHESS (page 24):

‘Mr Finck’s letter is typical of a number of requests I have had for a Dr Lasker’s Chess Career, Part II. I have had such a manuscript in readiness for a number of years, but I do not know of any publishing firm which has a burning interest in the project. To my deep regret, therefore, the manuscript continues to remain unpublished. If any of your readers know of any way to make publication possible, I shall be deeply grateful.’

Reinfeld did not make it clear whether Fine also collaborated on Part II. As pointed out in C.N. 1572, Fine referred to his participation in Part I on page 80 of his book Lessons from My Games.

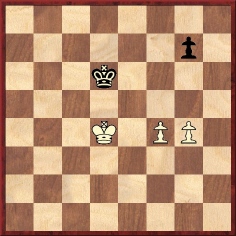

In Chess Fundamentals Capablanca published the following as ‘Example 8’:

Page 64 of Comprehensive Chess Endings, volume 4, by Y. Averbakh and I. Maizelis (Oxford, 1987) comments on the position as follows:

Critical analysis of this position appeared on page 268 of the November 1949 Magyar Sakkvilág, where Dr Jenő Bán claimed to correct Capablanca by demonstrating a win by 1 f5 g6 2 fxg6 Ke6 3 g5 (Not 3 Ke4 Kf6 4 g7 Kxg7 5 Kf5 Kf7, with a draw) 3...Ke7 4 Ke5 Kf8 5 Kf6 Kg8 6 g7 Kh7 7 g8(Q)+ Kxg8 8 Kg6 and wins. These moves were repeated by Fred Reinfeld on page 279 of The Joys of Chess (New York, 1961), in a chapter entitled ‘Boners of the Masters’.‘Here the only move not to win is 1 g5? in view of 1...g6. Curiously, in the 1st edition of his Chess Fundamentals, Capablanca asserted (he later corrected this) that 1 f5 also did not win in view of 1...g6 (he left the analysis of the variation to the reader). Capablanca gave the solution 1 Ke4 Ke6 2 f5+ Kf6 3 Kf4 etc. But it is precisely by 1 f5! that White wins more quickly.’

(2011)

For a detailed discussion of this position, see A Pawn Ending Mystery.

The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1961), page 116

‘One of the greatest masters in the world’ is the description of Fred Reinfeld in the entry for his book Scacchi per ragazzi on page 16 of Lineamenti di una bibliografia italiana degli scacchi by A. Sanvito (Rome, 1997). Our thanks to Alessandro Nizzola (Mantova, Italy) for drawing our attention to this considerable exaggeration.

The English-language edition of Reinfeld’s book, Chess for Children, called him a ‘Leading Chess Master’ and the ‘world-famous chess writer and champion player’. The dust-jacket also declared:

‘Fred Reinfeld is an author extraordinary. Some of his many readers call him a “genius”, and all recognize his versatility and talent. He is probably the most prolific American writer living today, author of about 75 books (more than he can count, he says).’

Yet those affirmations are like the gospel truth compared to the self-glorification in which Cardoza Publishing has recently allowed its chess writers [e.g. Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller] to indulge – dregs pretending to be cream.

(2377)

An early specimen of his play:

Fred Reinfeld – S.L. Thompson

Correspondence game (North American Championship, section

three), 1927

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d5 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 Qf3 f5 6 d3 Nxc3 7 bxc3 d4 8 Qg3 Nc6 9 Be2 Be6 10 c4 Bb4+ 11 Kd1 Qd7 12 Rb1 Rb8 13 Bf3 O-O 14 Ne2 Bc5 15 Nf4 Ne7 16 h4 b5 17 cxb5 Bxa2 18 Nh5 Ng6 19 Ra1 Be6 20 Bc6 Qf7 21 Bf4 Bd5

22 Nf6+ gxf6 23 h5 Bxc6 24 bxc6 Rb6 25 e6 Qg7 26 hxg6 Qxg6 27 Qf3 Qg4 28 Qxg4+ fxg4 29 Rh5 Rxc6

30 Ra5 Bb6 31 Rag5+ Kh8 32 Rd5 Rxe6 33 Rd7 Rfe8 34 Rhxh7+ Kg8 35 Kc1 Ba5 36 Rdg7+ Kf8 37 Bh6 Re1+ 38 Kb2 Bc3+ 39 Kb3 Rb8+ 40 Kc4 Rb4+ 41 Kc5 Re5+ 42 Kc6 Rb6+ 43 Kd7 Resigns.

Source: The Gambit, January 1928, page 28.

(2492)

On page 45 of Chess Review, February 1956, Fred Reinfeld wrote:

‘Like many another great composer, Rossini knew a good tune when he stole one. Perhaps that is why his masterpiece, The Barber of Seville, is so full of gay and witty melodies. Yet the day may come when this opera will be remembered only as the occasion of Morphy’s most brilliant game!’

This text also appeared on page 123 of Morphy Chess Masterpieces by Fred Reinfeld and Andrew Soltis, except that in that book (published in 1974, ten years after Reinfeld’s death) ‘Yet the day may come’ was replaced by ‘Perhaps the day will come’.

An odd suggestion in both wordings. At all events, some chess writers have claimed that the Morphy miniature was played during a performance of Bellini’s Norma.

(Chess Café, 1998)

The following news item comes from page 195 of the July 1965 Chess Review:

‘The Library of Fred Reinfeld, chess champion, writer and teacher who died last year, has been given to New York University by his widow, Mrs Beatrice Reinfeld.

The collection of more than 1,000 books on chess, includes a group of tournament books, books about the world’s chess masters and a general library covering the game in English, French, German, Russian, Spanish and other languages.

Included are a collection of international chess periodicals from 1880 to 1964 and a number of the more than 260 books written by Mr Reinfeld. He was New York State chess champion in 1931 and 1933 and was Executive Editor of Chess Review.’

The two totals quoted would seem, respectively, very low and very high.

(2579)

From page 179 of Great Moments in Chess by Fred Reinfeld:

‘In modern times the level of annotating rose very steeply. Alekhine’s profound annotations for the book of the New York, 1924 tournament, on which he is said to have spent a whole year, set a hitherto unknown standard. Actually, the Teplitz-Schönau, 1922 tournament book, which came out somewhat earlier but did not attain a wide circulation, was on an even higher plane. In fact, there are those who think that this masterpiece of Grünfeld and Becker is the greatest work of annotating that has ever been seen. Equally fine books may be written in the future, but it may be said with confidence that these two great works will always tower over the run-of-the-mill productions of chess annotators.’

The Teplitz-Schönau book (all 664 pages of it, although this total includes considerable coverage of masters’ career records, problem chess, etc.) was reprinted by Edition Olms, Zurich in 1981.

(2626)

From the Preface (page vi) of How to Play Better Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

‘But the present type of book – one intended for players who are beyond the beginning stage – is much more difficult to write. How does one select the subject matter?! What A needs to know is familiar to B and of no interest to C.

Looking at earlier books is of no great help. Capablanca’s Chess Fundamentals does not indicate any awareness of the problems involved. He does not bother, for example, to explain the moves of the pieces, the nature of checkmate, the details of the chess notation! Yet his book devotes three pages to an ending which has occurred only once, to my knowledge, in the whole history of master play. Again, eight pages are spent on the mate with bishop and knight and the win with queen against rook – although most of us play chess for a whole lifetime without once encountering these problems!

In Lasker’s Manual of Chess we find the same lack of selectivity. The book is long, and demands considerable reading time. It contains pages and pages of abstruse philosophical thinking, which is interesting but of no use to a beginner. There are many composed endings which are artistic but of no practical value; yet Lasker gives slight attention to the endings that actually occur in real games; and he (intentionally!) skimps the openings rather badly.’

(2644)

‘Dr Bernstein is a famous master; his fame rests on three atrociously played games with Capablanca. That this great player deserves more than merely negative immortality is realized by very few people. Tartakower points out the interesting fact that Bernstein, in common with Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch and Spielmann, was among the first to rebel against the artificial stiffness and formalism of the Tarrasch epoch.’

Source: Page 36 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933).

(2692)

There cannot be many cheap paperback reprints which are harder to find than the original hardback edition, but such a case is A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld. It was first brought out by Chatto & Windus, London in 1950 and is still easy to procure today. For some reason the same cannot be said of the 1962 Dover edition (for which Reinfeld added six games played between 1949 and 1961).

(2698)

Coles Publishing Company pirated editions of books by Capablanca, Marshall, Reinfeld, Rice and Love (see A Publishing Scandal).

Postings at the Chess Café’s Bulletin Board in 2001 (most notably by Paul Kollar) pointed out many passages published under Larry Evans’ name which were identical or similar to what had appeared in books by Lasker, Réti, Reinfeld and Fine.

(2971)

The following is Fred Reinfeld’s introduction to Tartakower v L. Steiner, Warsaw, 1935, on page 116 of Relax with Chess (New York, 1948):

‘When Professor Weiner [sic – Wiener] of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology invented a calculating machine which requires only one ten-thousandth of a second for the most complicated computations, he was quoted as saying, “I defy you to describe a capacity of the human brain which I cannot duplicate with electronic devices”.

Up to the time these lines were written, the Professor had apparently not yet perfected an electronic device capable of making such chess moves as Tartakower’s 20th in the following game. The day may yet come, however, when we shall see such books as ‘Robot’s 1000 Best Games’, or when chess tournaments will have to be postponed because of a steel shortage.’

Today’s computers find 20 Nxd8 instantaneously. As regards his 19th move, i.e. the sacrifice Nxf7, Tartakower wrote on page 61 of his second Best Games volume: ‘The art of chess is simple: you play Nf3-e5 and then, sooner or later, Nxf7 is decisive.’

(3177)

Alekhine has been the subject of two main accusations of violent action after losing a game: a) destroying hotel furniture and b) throwing his king across the tournament hall. These were discussed on, respectively, page 156 of Chess Explorations and pages 279-280 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

Alexander Alekhine

Page 3 of the January 1986 APCT News Bulletin had the following affirmation about Alekhine v Yates, Carlsbad, 1923:

‘Rumor has it that after losing this game, Alekhine went back to his hotel room and smashed the furniture.’

As reported in C.N. 1129, we requested a source for this (‘a contemporary reference, naturally, and not a Horowitz or Reinfeld potboiler’), but the February 1986 issue of the Bulletin (page 41) merely offered the following passage from page 128 of Reinfeld’s Great Brilliancy Prize Games of the Chess Masters (New York, 1961):

‘The story is told that one day after losing a game in the formidable Carlsbad tournament of 1923, Alekhine went back to his hotel room and smashed every stick of furniture. The following game [Alekhine v Yates] may well be the one that made him so rambunctious, for his defeat cost him clear first prize in the tournament.’

C.N. 1129 then pointed out that Alekhine’s loss to Yates was the second of three defeats at Carlsbad, 1923. Both Reinfeld and the APCT News Bulletin had overlooked that it was played as early as round seven (out of 17 rounds) and therefore did not ‘cost him clear first prize’. We added that the incident was often ‘rumoured’ to have occurred after Alekhine’s loss to Spielmann in the same tournament.

And there the matter was left. But now we note that in an article published 11 years before Reinfeld’s book appeared (i.e. in Chess Review, May 1950, pages 136-138) he co-authored with Hans Kmoch an article on Carlsbad, 1923 which stated:

‘Alekhine was as furious as only he could be when he unexpectedly lost a game in his palmy days. On such occasions, rare though they were, he was filled with savage anger, so much so that he ran the danger of getting a stroke if he did not have an adequate outlet for venting his rage. Having resigned his game to Spielmann, he stormed back to his room at the Imperial (the best hotel in Carlsbad) and smashed every piece of furniture he could get his hands on.’

It may be wondered why Reinfeld was later to speculate, when writing solo, that the game in question had been against Yates.

Another article by Reinfeld and Kmoch in the 1950 Chess Review (February issue, page 55) said that at the end of his game against Grünfeld at Vienna, 1922 ‘Alekhine resigned – by taking his king and throwing it across the room’. Kmoch was a participant in the tournament.

Such accounts are insufficiently vivid for the likes of Harold C. Schonberg, who decided, on page 27 of Grandmasters of Chess, to make the throwing more dramatic and the destroying more frequent:

‘Alekhine once resigned, frantic with rage and frustration, by picking up his king and hurling it across the room, nearly braining a referee in the process. (Tournament pieces are weighted with lead; they can be dangerous weapons.) Alekhine would also relieve himself after a loss by going to his hotel room and destroying the furniture.’

In Grandmasters of Chess Schonberg exhibited scant concern for facts or fairness, and on page 220 he even professed that Alekhine was ‘as amoral as Richard Wagner or Jack the Ripper’. If morality is the issue, Schonberg’s act of writing such a thing is worth a moment’s contemplation.

(3196)

From an article ‘Unconventional Surrender’ by Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld on page 55 of the Chess Review, February 1950:

‘Alekhine hit on still another way of resigning during the Vienna tournament of 1922. ... When he saw that Grünfeld had sealed 54...Q-B6 (the strongest move), Alekhine resigned – by taking his king and throwing it across the room.’

From page 4 of Why You Lose at Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘Hans Kmoch and I once surveyed [methods of resigning] in an article called “Unconventional Surrender”. We recalled that Alekhine, who was unequaled as a desperate fighter in disheartening situations, occasionally [our emphasis] resigned by picking up his king and hurling it across the room.’

Notwithstanding the word ‘occasionally’, the Kmoch/Reinfeld article had not suggested that the conclusion of the Alekhine v Grünfeld game was other than an isolated incident.

As noted above, Kmoch was a participant in Vienna, 1922, but does any other source corroborate the claim about Alekhine which Kmoch made nearly three decades later?

(5843)

The above C.N. item was entitled ‘The anecdotalist’s plural’.

From page 12 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘... Alexander Alekhine was not only the greatest of the world champions; he was also the greatest chess artist of all time. He was a man of extraordinary nervous energy who had been known to fling his king across the room or smash furniture on the rare occasions when he lost. A rotten sport, maybe, but he took his chess very hard.’

See also Chess with Violence.

From page 227 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘So Lasker dodged Rubinstein and Capablanca for years, and Alekhine acquitted himself shabbily in never allowing Capablanca a return match. Alekhine merely waited over 20 years, until Capablanca’s skill deteriorated below the level required for a match.”

It may be wondered which period of ‘over 20 years’ Reinfeld had in mind.

(3271)

‘In chess the “pin” is mightier than the sword!’

So wrote Robert M. Snyder on page 75 of Chess for Juniors (New York, 1991), but a more careful author would have refrained from using Fred Reinfeld’s old quip without attribution. Reinfeld quoted his remark on page 293 of The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951), but we do not know when he first came up with it.

(3599)

We can add that on page 159 of his book Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963) he offered a simple variant: ‘... the pen is mightier than the pin’.

(3625)

C.N. 3599 commented, ‘Reinfeld quoted his remark on page 293 of The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951), but we do not know when he first came up with it’. That remains the case, but page 32 of the March 2006 CHESS points out that it was also attributed to Reinfeld when quoted under the chapter heading on page 7 of an earlier work, Winning Chess (co-authored with Irving Chernev). That book was first published in 1948 (not 1949 as stated by CHESS), and the quest continues for any previous appearance of the phrase in Reinfeld’s output.

(4313)

Winning Chess was published in or around May 1948 (see page 3 of the 20 May 1948 Chess Life), and a slightly earlier occurrence of the quip can now be offered:

Source: page 147 of Reinfeld’s Nimzovich the Hypermodern (Philadelphia, 1948). The book was reviewed on page 2 of the 5 March 1948 issue of Chess Life.

(7799)

The saying ‘The pin is mightier than the sword’ has occasionally been attributed to Al Horowitz. For instance, on page 45 of the January 1975 Chess Life & Review Walter Meiden and Norman Cotter wrote:

‘The late Al Horowitz, who was publisher of Chess Review, used to say: “The pin is mightier than the sword”.’

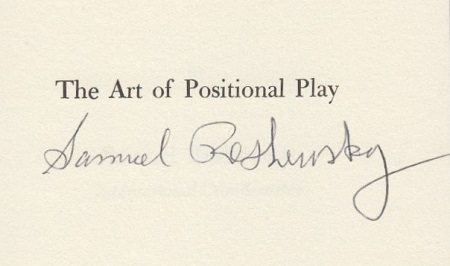

And from page 79 of The Art of Positional Play by Samuel

Reshevsky (New York, 1976):

‘The late I.A. Horowitz used to quip: “The pin is mightier than the sword”.’

Loose claims about what people ‘used to’ say/quip obviously lack credibility, and Horowitz himself attributed the phrase to Reinfeld:

‘... there are pins and pins, despite Reinfeld’s dictum that “the pin is mightier than the sword”.’

Source: page 70 of Chess for Beginners by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1950).

(8730)

It may seem paradoxical to describe as ‘little known’ a game published in a book by Reinfeld and Chernev, but the encounter between Flamberg and Levitzky, St Petersburg, 1914 is seldom seen nowadays. Yet when they published it on pages 43-44 of their book Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933), the Americans wrote by way of introduction:

‘The Polish master Alexander Flamberg was a highly gifted player with profound and original ideas. Chronic ill-health prevented him from ever asserting his full powers.

Concerning one of his notable games – one of the most significant in the history of chess – his countryman Przepiórka has commented as follows: “When one examines the opening moves and the subsequent course of the game, it is almost incredible that it was played in 1914 ... The double fianchetto of the bishops, the operations on both wings, and later on the manoeuvers with the black knights and the posting of the queens on the long diagonal – all these ideas are, as we know, considered the very latest achievements of the Hypermoderns.”’

For the record we add that these comments by Przepiórka appeared on page 34 of the February 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung. He used the term ‘A Prophetic Game’ to describe this victory by Alexander Flamberg (1880-1926).

Alexander Flamberg

Alexander Flamberg – Stepan Mikhailovich Levitzky

All-Russian Masters’ Tournament, St Petersburg, 16 January 1914

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 e6 5 O-O Be7 6 b3 O-O 7 Bb2 d6 8 c4 Nbd7 9 Nbd2 c5

10 Ne1 Qc7 11 Rc1 Bxg2 12 Nxg2 Qb7 13 Ne3 cxd4 14 Bxd4 Nc5 15 Qc2 Nce4 16 Nxe4 Nxe4 17 Qb2 e5 18 Bc3 Bg5 19 f4 exf4 20 gxf4 Bf6 21 Bxf6 Nxf6 22 Rcd1 Qe4 23 Rf3 Nh5 24 Nd5 Rae8 25 Kf2 Qf5 26 Rg1 f6 27 Qb1 Qc8 28 Qd3 f5 29 Qc3 Kh8 30 Rh3 Nf6

31 Rxg7 Kxg7 32 Rg3+ Kh6 33 Nxf6 Re6 34 Rg5 Qc5+ 35 Kf1 and wins.

Przepiórka (as well as Reinfeld and Chernev) stated that the game ended 35 Kf1 Re3 36 Ng4+ fxg4 37 Qg7 mate, whereas Black resigned at move 35 according to pages 34-35 of Schachjahrbuch 1914 I Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914).

It may be felt that calling the game ‘one of the most significant in the history of chess’ is an exaggeration, but the play is certainly an early illustration of hypermodern tenets.

(3692)

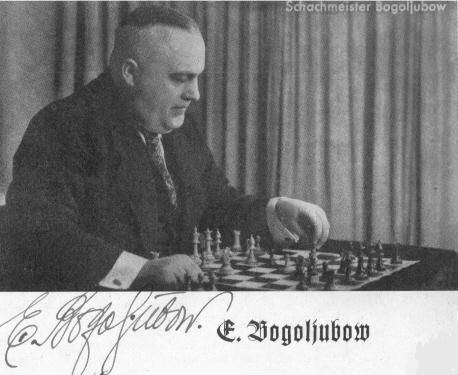

From Hypermodern Chess:

It is not always clear who should be regarded as a hypermodern player. C.N. 653 mentioned the case of Efim Bogoljubow, pointing out that on page 106 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942) Reinfeld described Capablanca v Bogoljubow, London, 1922 as the Cuban’s ‘first encounter with an outstanding Hypermodern master’. However, we added that a random check of tournament books of some of Bogoljubow’s greatest triumphs in the 1920s indicated that his opening play was extremely classical, with barely an Indian Defence, Réti Opening, etc. in sight.

Efim Bogoljubow

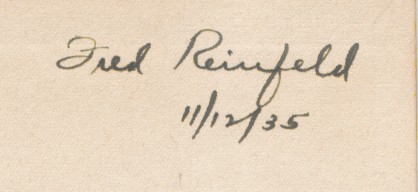

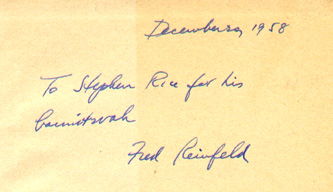

The book mentioned in C.N. 3692, Chess Strategy and Tactics, is one of only two in our collection which are inscribed by Fred Reinfeld, the other being The Secret of Tactical Chess (London, 1958).

Dealers’ catalogues occasionally mention the unexpected fact that books signed by Reinfeld are rare.

(3693)

Opposite the title page of The Human Side of Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1952) was a list of four other books by him, including ‘Paul Morphy, King of Chess (in preparation)’. No such volume ever appeared, although in 1974 Collier Books, New York brought out Morphy Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld and A. Soltis. (The back cover stated that Reinfeld had ‘died in 1973’, instead of 1964.) We know nothing of the genesis of the Reinfeld/Soltis book, i.e. to what extent it may have been based on Paul Morphy, King of Chess.

(3827)

Regarding Reinfeld’s treatment of a Morphy v Lichtenhein game and related Morphy matters, see C.N. 11485.

Comments by Reinfeld about Morphy’s famous opera game are included in Morphy v the Duke and Count.

From page 158 of CHESS, April 1940 (in a review of Reinfeld’s book Practical End-Game Play):

‘Mr Reinfeld is an attractive and industrious writer but there are certain faults of which he must rid himself to become a great one. It is in all kindness that we enumerate them. The first is bumptiousness. He is too prone to throw his weight about from the safe retreat of armchair analysis. The amateur reader, hearing him denounce Tarrasch for “gross blunders”, Schlechter for “superficial appraising of the position”, Euwe for “grossly miscalculating”, Tartakower for “lack of insight” and so forth can hardly fail to ask, with initial admiration: “Who is this genius who can pierce through the armour of the great?” Mr Reinfeld’s playing record comes as a shock. The discovery of occasional “gross errors” in his writings, committed not under the nervous tension of tournament play but in the calm of literary composition and overlooked in successive proof-corrections and the realization that the analysis on which he bases his denunciations is rarely his own (as his own meticulous acknowledgments reveal) add to the disillusionment. Such a disillusionment is unnecessary and pointless. We judge a writer as a writer, a player as a player – until the writer obtrudes his own personality on us by such harsh and pointless criticisms.’

(3829)

From page 24 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘At the chessboard Zukertort was a remarkable mixture of deep analytical powers and far-reaching intuitive genius. He produced beautiful moves with the practiced ease of a conjurer.

The following combination [against Blackburne at London, 1883], generally recognized as his finest, has always had a special fascination for me. When I was 11 years old, I learned the moves by reading the article on chess in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Included in the article were a number of memorable master games, and one of them contained the following combination.

The sequence of incomprehensible moves troubled me. For three months I played over the combination every day, hoping to puzzle out its why and wherefore. But I failed to fathom it – and no wonder. For this combination is one of the sublime examples of the art of chess.’

That quote is a welcome addition to our series entitled ‘When did Reinfeld learn chess?’ (C.N.s 2116 and 3285), which has presented the following incompatible statements:

‘Born in New York on 27 January 1910, Fred Reinfeld learned the moves of the game at the age of nine and, as he himself confesses, forgot in five minutes all he had learned in ten. He challenges anybody to duplicate that record. Subsequently, he became interested for a time in checkers, but abandoned the sister game in favour of chess.

Around Christmas of 1923 Reinfeld began haunting the libraries in search of chess literature, much of which he was at great pains to copy. At length he had a collection of some 2,000 games. At that time he was studying at De Witt Clinton High School and in due course earned a place on the school team.’

(3872)

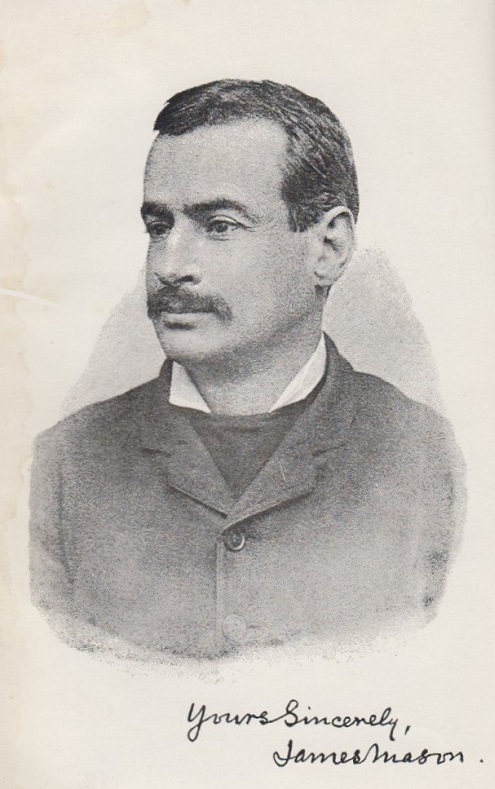

This sketch of Reinfeld was given in C.N. 3285:

From page 18 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004):

‘Match with Fred Reinfeld, New York, 25 July-9 August 1931. Fred Reinfeld’s papers indicate that the youngsters contested a six-game match in the late summer. Fine won three games to Reinfeld’s two, the other game being drawn. In addition to the match Fine and Reinfeld were involved in a consultation game on 17 September. Game-scores unavailable. Crosstable unavailable.’

However, we note that on pages 8-9 of the stencilled booklet A Course in the Elements of Modern Chess Strategy (Lesson V, Part II) by Fred Reinfeld and Matthew Green (New York, 1936) the following game was given (annotated by Reinfeld):

Fred Reinfeld – Reuben Fine

‘Impromptu match 1931’

Nimzo-Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 c5 5 dxc5 Nc6 6 Nf3 Ne4 7 Bd2 Nxc5 8 Qc2 f5 9 a3 Bxc3 10 Bxc3 O-O 11 g3 b6 12 Bg2 Bb7 13 O-O Qe7 14 Rfd1 d6 15 Nd4 Nxd4 16 Rxd4 Bxg2 17 Kxg2 Rac8 18 Rad1 Rfd8 19 b4 Ne4 20 f3 Ng5 21 Qd3 Nf7 22 e4 Ne5 23 Qe2 Qc7

24 Rxd6 Rxd6 25 Bxe5 Rd2 26 Qxd2 Qxe5 27 Qd7 Rf8 28 Qd4 Qxd4 29 Rxd4 e5 30 Rd5 fxe4 31 fxe4 Rc8 32 c5 bxc5 33 Rxc5 Rxc5 34 bxc5 Kf7 35 Kf3 Ke6 36 Kg4 Resigns.

(3920)

A number of C.N. items (the most recent being C.N. 3872) have discussed Fred Reinfeld’s contradictory statements about when he learned chess. Here we give his earliest game known to us, from pages 58-69 of his book How to Play Chess Like a Champion (New York, 1956). The only details supplied about this ‘typical amateur game, conveying above all the lack of consecutiveness which is so common in such games’ were that it occurred in a high-school match when he was aged 15. The punctuation in the game-score is his.

N.N. – Fred Reinfeld

New York, 1925 (?)

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 d3 h6 6 O-O d6 7 Nd5 Nxd5 8 Bxd5 Be6 9 Bxe6? fxe6 10 b3? O-O 11 Bb2 Qf6! 12 Qe2 a5 13 c3?! Kh7? 14 Qc2? Qg6! 15 Nh4 Qg5 16 g3 Rf4? 17 Bc1! Raf8 18 Ng2? Rxf2!! 19 Rxf2 Rxf2 20 d4 Rxc2 21 Bxg5 exd4 22 cxd4? Nxd4? 23 Bd8? Nc6+ 24 Kf1 Rf2+ 25 Ke1 Rxg2 26 White resigns.

(3978)

Andy Ansel (Laurel Hollow, NY, USA) informs us, on the basis of a notebook of Reinfeld’s, that the game given in C.N. 3978 was played against Stubing in an Inter-Scholastic league match between DeWitt Clinton and Mount Vernon at the Manhattan Chess Club on 15 November 1924. Reinfeld’s book should thus have given his age as 14 rather than 15.

Mr Ansel provides, from the same source, another Reinfeld game, played at the Manhattan Chess Club three weeks later:

Pimsler – Fred Reinfeld

Morris v DeWitt Clinton match, New York, 6 December 1924

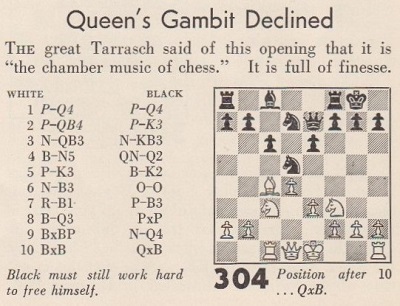

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 d5 4 Bg5 c5 5 e3 Be7 6 Nbd2 Nc6 7 a3 O-O 8 dxc5 Bxc5 9 Rc1 Bd6 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Bd3 Bg4 12 Qc2 h6 13 Bh4 Rc8 14 Bg3 Bxg3 15 hxg3 Ne5

16 Nxe5 Rxc2 17 Rxc2 Qe7 18 Nxg4 Nxg4 19 Nf3 Re8 20 Be2 Qe4 21 Bd1 d4 22 Re2 d3 23 Rd2 Ne5 24 Nxe5 Qxg2 25 Bf3 Qxh1+ 26 Bxh1 Rxe5 27 Rxd3 Rb5 28 Be4 Kf8 29 b4 Ke7 30 Bd5 Rb6 31 f4 Rd6 32 Ke2 b6 33 e4 f6 34 g4 g6 35 Ke3 Rd7 36 e5 Rd8 37 Be4 Rxd3+ 38 Bxd3 g5 39 exf6+ Kxf6 40 f5 Resigns.

(3982)

‘I believe that this book is the first in the history of chess literature to be made up exclusively of amateurs’ games ...’

Fred Reinfeld on page ix of his book Chess for Amateurs (Philadelphia and London, 1943).

(4096)

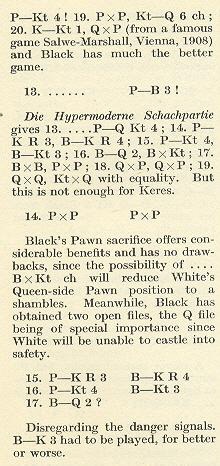

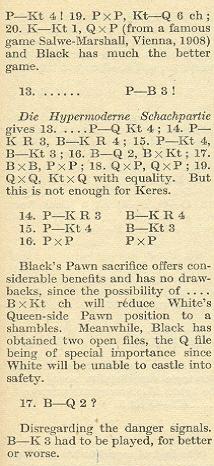

C.N. 4355 asked what the explanation was for the following:

They are reproductions from page 201 of Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 by Fred Reinfeld, i.e. the original 1941 edition and the 1946 ‘reprinted’ version. The game was M. Luckis v P. Keres in the round-robin tournament in Buenos Aires, 1939. The full score was given on pages 27-28 of Torneo internacional del círculo de ajedrez octubre 1939 by M. Czerniak (Buenos Aires, 1946), where the possibility of 14 dxc6 Qd1 mate was noted.

‘Have I made a great discovery or has the printer made a great bloomer?’, asked Alfred Milner on page 83 of the April 1942 BCM after mentioning the one-move mate in the context of Reinfeld’s book. Page 110 of the May BCM reported:

‘Several readers have pointed out that Keres did not leave a mate on the move as suggested in our last issue. There is a transposition of moves in F. Reinfeld’s book and the possibility did not occur.’

(4362)

A curiosity among books ‘by’ Fred Reinfeld is 101 Chess Problems for Beginners. It is readily available in various paperback editions published by the Wilshire Book Company, and the front cover and spine ascribe editorship to Reinfeld, with no mention of anyone else. Inside, however, an explanatory note is entitled ‘101 Chess Problems for Beginners by Comins Mansfield and Brian Harley Edited by Fred Reinfeld’. The final paragraph of that note reads:

‘All these problems are the work of Comins Mansfield, one of the most distinguished men in this field. The introduction and the detailed explanations of the solutions are by Brian Harley, one of the outstanding authorities on problems. Fred Reinfeld has contributed a foreword, helpful hints to solvers, and careful editing to enhance the reading pleasure of those who are trying their hand at problem-solving for the first time.’

Tracing the genesis of the book is not easy, but it is a rewritten version of Mansfield and Harley’s The Modern Two-Move Chess Problem (London, 1958).

Reinfeld’s book is dated 1960, at which time Mansfield, though not Harley, was still alive. We are not insinuating that Reinfeld did anything improper (the 1958 book is, after all, mentioned on the imprint page), but we should like to know more about any arrangement entered into with Mansfield which led to the curiosity of only Reinfeld’s name appearing on the cover.

(4775)

We have now acquired a copy of the original (hardback) edition of the problem book, published in New York in 1960. It was entitled not 101 Chess Problems for Beginners but 101 Chess Puzzles and How To Solve Them. As regards authorship and editorship, the title page was entirely accurate:

(4785)

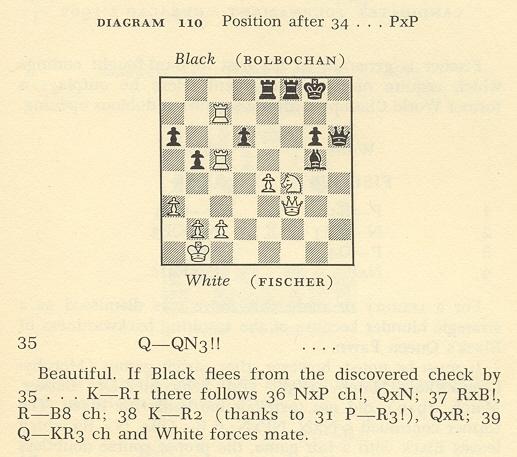

Concerning the Fischer v Bolbochán analytical fiasco, below is a snippet from Fischer’s Fury:

The following appeared on page 233 of Great Games by Chess Prodigies by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1967 and 1972), with a white rook at c5 instead of d5:

C.N. 889 (see pages 264-265 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) mentioned that half-way through a review of Great Games by Chess Prodigies, John Graham’s The Literature of Chess (Jefferson, 1984) started calling Reinfeld Horowitz.

Page 235 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 30 June 1912 mentioned a person from Fellin (i.e. Viljandi) named F. Reinfeld.

(5246)

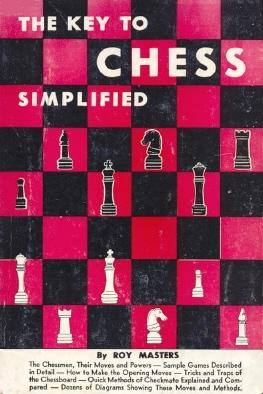

We believe that Fred Reinfeld’s first non-chess book was an abridgment of Oliver Twist (New York, 1948). The front cover featured John Howard Davies in the title role in the film version released the same year, and the last two pages (313-314) had an Afterword by Reinfeld about Dickens’ life and work.

(4859)

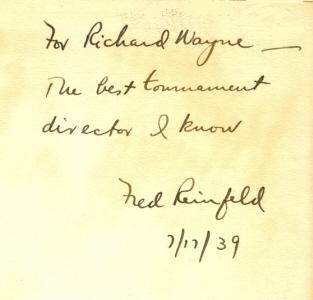

A further specimen of an inscription by Reinfeld in our collection comes from the book he co-authored with Reuben Fine, Dr Lasker’s Chess Career: Part I, 1889-1914 (New York, 1935):

A biographical note on Richard Wayne would be welcomed.

(5422)

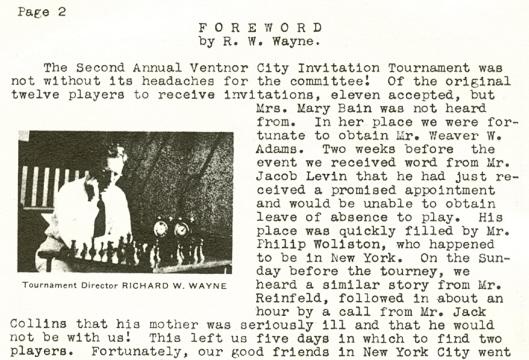

Pete Tamburro (Morristown, NJ, USA) reports that Richard W. Wayne was a director of the United States Chess Federation in the 1940s and lived in Ventnor City, NJ. He was the tournament director of the City of Ventnor Invitation Tournament (8-16 July 1939), in which Fred Reinfeld participated. A victory by Wayne against G. Ross in the 1940 Ventnor City Chess Club Championship was given in the April 1940 issue of Jersey Chess. An item by Robert Durkin on page 3 of the April 1974 Atlantic Chess News stated that Wayne was then aged 80 and ‘was a motorcycle test driver in his younger days, as well as a Sgt. major in the British Army’.

We note that a small, dark photograph of him appeared on page 2 of the Ventnor City, 1940 tournament book:

(5445)

On page 327 of the November 1955 Chess Review Fred Reinfeld wrote:

‘Some time ago a friend complained to me that, although he had been playing chess for many years, his game did not improve. “Is this”, he asked, “because I play only once a week?”

My words stunned him. I advised him: “Stop playing altogether for about a year.”

“How will my game improve if I don’t play?” He enjoyed playing, and the whole point of bettering his game was so he could enjoy it more.

“Of course”, I replied, “you want to play better, but playing won’t teach you enough, fast enough, or clearly enough, to make you the good player you want to be. You should read rather than play – study rather than stumble along.” Playing only reinforces bad habits (if they are bad to begin with), I told him. Learn the right way; play by yourself with some books for a year, and then go back to club play.

This is still the best advice I can give anyone whose game is weaker than it should be: “Read, and read more. Study, and study more.”’

Reinfeld’s article then recommended his series, The First Book of Chess, The Second Book of Chess, etc. There were eventually eight volumes in all, published between 1952 and 1957, the first being co-authored with Al Horowitz.

(4519)

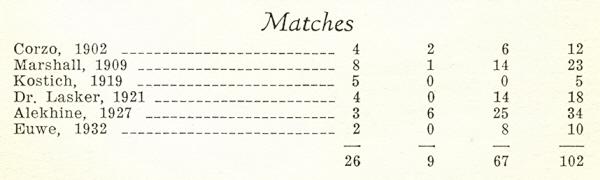

An extract from C.N. 4574:

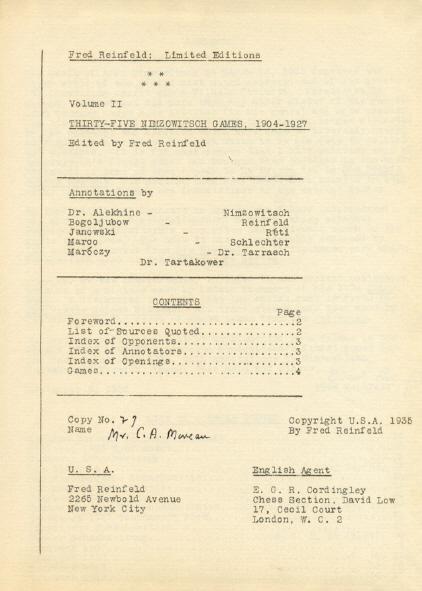

It was mentioned in A Chess Omnibus that the list of subscribers to Reinfeld’s 1935 book on Cambridge Springs, 1904 included ‘C. Moreau’, and here we add that our copy of Reinfeld’s book Thirty-five Nimzowitsch Games, 1904-1927 (New York, 1935) contained, handwritten, the subscriber’s name, C.A. Moreau:

However, the list of subscribers on page 91 of Keres’ Best Games 1932-1936 (New York, 1937) by F. Reinfeld stated ‘C.L. Moreau’. Whether or not it was Colonel Moreau whom Reinfeld had among his subscribers is not known.

C.N. 2578 (see page 191 of A Chess Omnibus) gave a list of non-chess books by Fred Reinfeld and mentioned one of his alleged pseudonyms, ‘Robert V. Masters’. Is any firm information available on that name?

Moreover, what is known about Roy Masters, the author of The Key to Chess Simplified, a 96-page book from Key Publishing Company, New York which first appeared in 1959?

(4778)

‘Roy Lopez’ appeared on the front cover of lesson XV in Fred Reinfeld’s series A Course in the Elements of Modern Chess Strategy, but Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA) notes that some of the pamphlets were reprinted several times and that his copy has the correct spelling.

We had before us the ‘Second Printing, September 1938’:

Our correspondent also mentions that lesson XXIV invited subscriptions for an additional four issues, whereas Douglas A. Betts’ Annotated Bibliography (pages 197-199) indicates that XXIV was the last to be published. For our part, we have never seen any subsequent issues.

Lesson XXIV (‘First Printing, December 1938’) was devoted to the Tarrasch Variation in the Ruy López and included on pages 11-12 an early postal victory by Reinfeld:

Fred Reinfeld – Narraway1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 dxe5 Be6 9 c3 Be7 10 Be3 O-O 11 Nbd2 Bg4 12 Nxe4 dxe4 13 Qd5 exf3 14 Qxc6 fxg2 15 Qxg2 Qd7 16 Rfe1 c5

17 Bh6 gxh6 18 e6 Qc8 19 exf7+ Kh8 20 Rxe7 Bh3 21 Qd5 Qg4+ 22 Kh1 Qg5 23 Rg1 Bg4 24 Rxg4 Resigns.

(4858)

The opening part of the first sentence (on page v) of the Preface to How to Play Better Chess by Fred Reinfeld (London, 1948):

‘Chess has been played for thousands of years …’

(Kingpin, 2000)

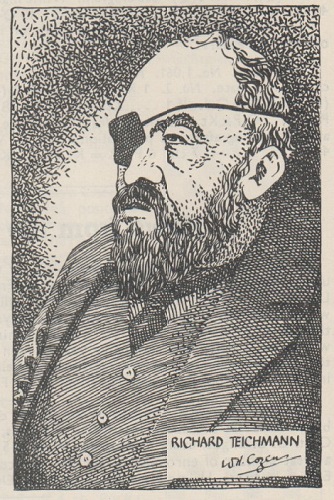

C.N.s 3079 and 3251 (see pages 326-327 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed a quote attributed to Teichmann, and now we note that Fred Reinfeld also gave it on page 129 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess (New York, 1960):

‘It took Nimzowitsch 20 years of tireless preaching to achieve acceptance. So great a master as Teichmann commented dourly that “in the first place there is no Hypermodern School, and in the second place Nimzowitsch is its founder”. This was a more or less polite way of saying that Nimzowitsch was crazy.’

That last remark of Reinfeld’s seems far-fetched, and it is unclear why he affirmed that Teichmann made the remark ‘dourly’.

Aron Nimzowitsch

Reinfeld on Nimzowitsch can be a strange spectacle. For example, on that same page he wrote: ‘By the time Nimzowitsch was 20, he had perfected his system.’ In his revised edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System (Philadelphia, 1947) Reinfeld wrote (page xxi) that ‘by 1906, when he was only 20, Nimzowitsch had definitely become a master of the very first rank’.

(5006)

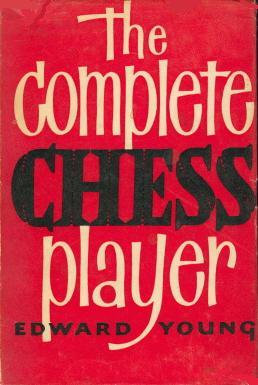

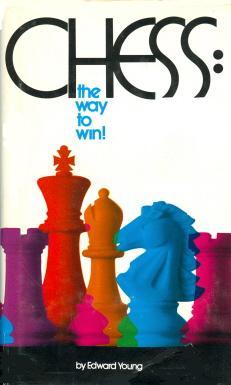

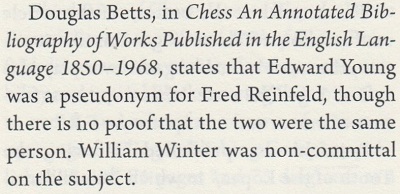

In 1960 Arco Publications (London) published The Complete Chess Player by ‘Edward Young’. Although Betts‘ Bibliography says that this was a pseudonym used by Fred Reinfeld, the dust-jacket of Young‘s book commends the author‘s work as follows: ‘Throughout the book his commentary on the various moves is most lucid and sound, and for sheer readability he is on a par with Fred Reinfeld.’

Nor is it easy to understand the brief, cryptic review which appeared on page 319 of the November 1960 BCM:

‘The (n+2)th way of becoming a “complete chessplayer”. The publishers inform us that this book “should rank as a classic of its kind”. It will. Information on the dust-jacket has been compiled with the usual meticulous attention and errors are purely accidental.’

In 1953 Reinfeld himself had produced a book entitled The Complete Chessplayer (published in New Jersey). The content was altogether different.

(Kingpin, 1995)

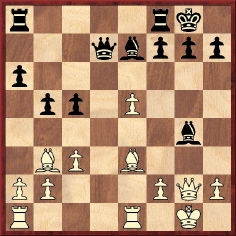

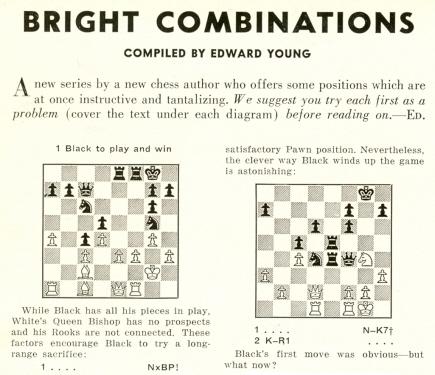

Proof is still being sought that Edward Young was a pseudonym of Fred Reinfeld. In 1955 Chess Review published three articles entitled ‘Bright Combinations’ by Edward Young, who was described as ‘a new chess author’.

(Kingpin, 1996)

Edward J. Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA) notes that around 1955 several small works appeared under the name of Edward Young: A Pocket Guide to Chess Openings, A Pocket Guide to Chess Pitfalls, A Pocket Guide to Chess Endings, A Pocket Guide to Chess Combinations and Sacrifices and Chess at a Glance. The publishers were I. & M. Ottenheimer, Baltimore, Maryland.

Jimmy Adams (London) sends a copy of Chess in 30 minutes, published by E.S. Lowe Company Inc., New York. It is marked ‘Copyright 1955 by Edward Young’. However, the book is evidently a reissue, since it concludes (page 91) with a reference to the first USA world champion, Bobby Fisher [sic].

Proof that Edward Young was Fred Reinfeld is still proving elusive.

(Kingpin, 1997)

We are still seeking information about ‘Edward Young’ (see page 327 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, which consists of material we originally gave in Kingpin). Books and articles appeared under his name, but Douglas A. Betts’ Bibliography stated that ‘Edward Young’ was a pseudonym for Fred Reinfeld.

The first appearance of the name that we have found is on page 114 of Chess Review, April 1955, at the start of a two-page article:

The two volumes below have the same contents and were published in 1960 by, respectively, Arco Publications, London and Castle Books, USA:

(5014)

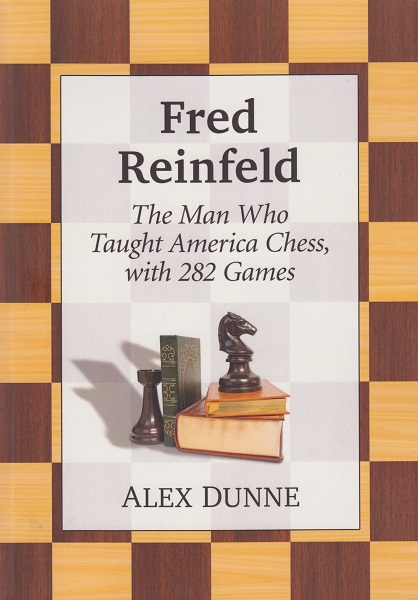

From page 158 of the new book mentioned in C.N. 11310, Fred Reinfeld. The Man Who Taught America Chess, with 282 Games by Alex Dunne:

Although, naturally enough, the general index has no entry for William Winter, it does refer to ‘Richard Cole’ (Richard Nevil Coles), ‘E. Sergeant’ (P.W. Sergeant), ‘Jack Spense’ (Spence) and ‘Rudolph Spielmann’ (Rudolf), errors which also occur in the body of the book.

A lamentable feature is some of the sourcing, or lack thereof. The references provided by Dunne include the following:

‘Chess Forums at Chess.com’ (page 47); ‘An Internet review by Mianfel states ...’ (page 56); ‘Wikipedia’ (page 94); ‘Chess Forums at Chess.com’ (page 131); ‘Chess Forums, Chess.com’ (page 142); ‘A review following the book’s Amazon advertisement read ...’ (page 160); ‘ChessManiac’ (page 168); ‘Arnold Denker in Chess Forums said of Reinfeld ... Chess.com’ (page 170); ‘ChessManiac’ (page 170); ‘The letter was published in ChessBase’ (page 173).

(11315)

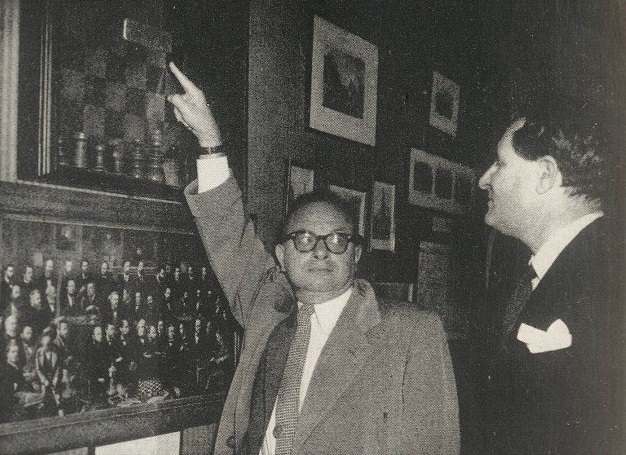

See too the review of the Dunne book by Tim-Jake Gluckman at the Kingpin website. A photograph of Reinfeld at Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, London is included there, and below we show a different shot (given in C.N. 2680), from page 356 of the December 1957 Chess Review.

The caption states:

‘Two chess writers meet, at Simpson’s Divan famous from long ago as a chess center in London: Fred Reinfeld and (right) Bruce Hayden inspect a trophy.’

Concerning the defilement of the chessboard plaque by the addition of Raymond Keene’s name, see The Immortal Game.

Did Fred Reinfeld, the author of The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942), know much about the Cuban’s career? In C.N. 473 we listed defects in the chapter on Capablanca in Reinfeld’s book The Human Side of Chess (London, 1953). The list is reproduced below, and it should be noted that the page numbers in the US edition (New York, 1952) are different. Twenty-four years on from the publication of C.N. 473 there are a few points that we would present differently today, but it remains extraordinary that Reinfeld made so many factual errors in a single 24-page chapter.

Below is an excerpt from a letter to us dated 19 January 1977 from Irving Chernev (San Francisco, CA, USA):

(5036)

See also Capablanca Goes Algebraic, as well as our feature article on Irving Chernev.

We have been re-reading Golombek’s chess column in The Times, which contained much of interest. On 10 December 1977 (page 11), for instance, he discussed, none too warmly, Fred Reinfeld’s writing career, although he seems to have considerably overestimated the quantity of the American’s production: ‘My own library contains 62 books by him and I believe this to have been about one fifth of his output.’ Reinfeld’s books on Botvinnik, Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch were deemed unimpressive, and regarding Nimzovich the Hypermodern (Philadelphia, 1948) Golombek wrote:

‘... there appeared in the American Chess Review of the time a review couched in the most glowing terms that occupied the whole of the last page. No full signature appeared but simply the initials F.R., and your guess is as good as mine as to whether this meant that the review was by Fred Reinfeld.’

It is unclear what Golombek had in mind, but the extensive book review on page 184 of the June 1949 Chess Review was signed not ‘F.R.’ but ‘J.R.’ (John Rather, the magazine’s Managing Editor).

(5215)

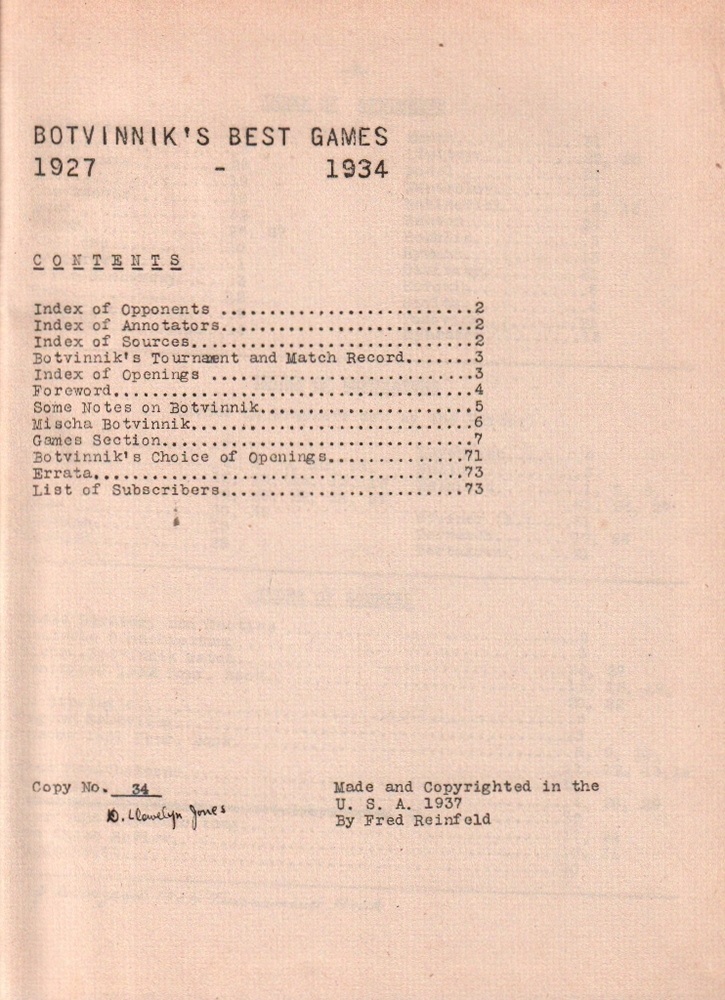

This group photograph (Pasadena, 1932) was published on page 116 of the July-August 1932 American Chess Bulletin. Does any reader have a better copy?

(5543)

‘Of all the chess books I have ever written, this is the one that was the most fun, because it has enabled me to share my chess pleasure with the reader.’

Source: page 19 of How To Get More Out Of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1957). The book was later reprinted under the title An Expert’s Guide to Chess Strategy.

(5739)

This quote was also given in C.N. 2493.

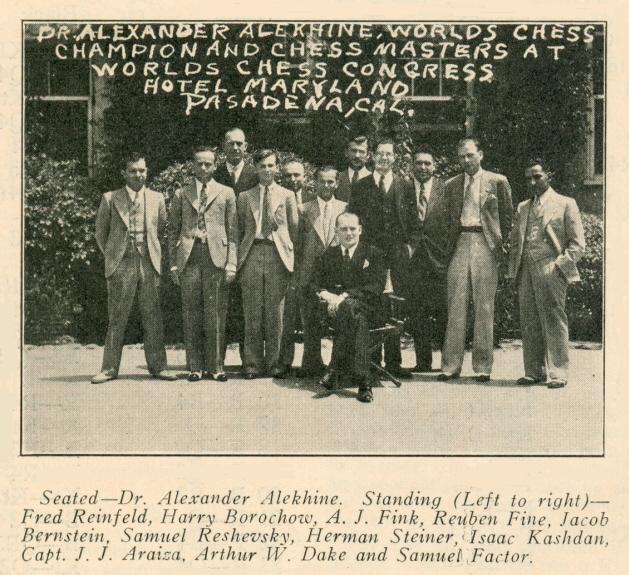

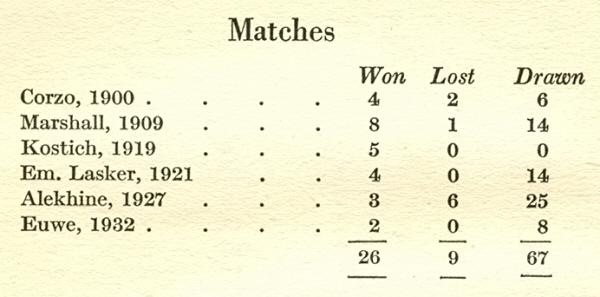

Page 14 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1942)

Page 20 of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1947)

In the Lasker match there were ten, not 14, draws. The Euwe match was in 1931, not 1932. The only matter on which the books disagree is the year of Capablanca’s match against Corzo, and both are wrong. It was played in 1901.

The two books have been the subject of modern reprints which have not bothered to correct these (and innumerable other) elementary mistakes.

(5904)

Fred Reinfeld, Chess Review, January 1943, page 29

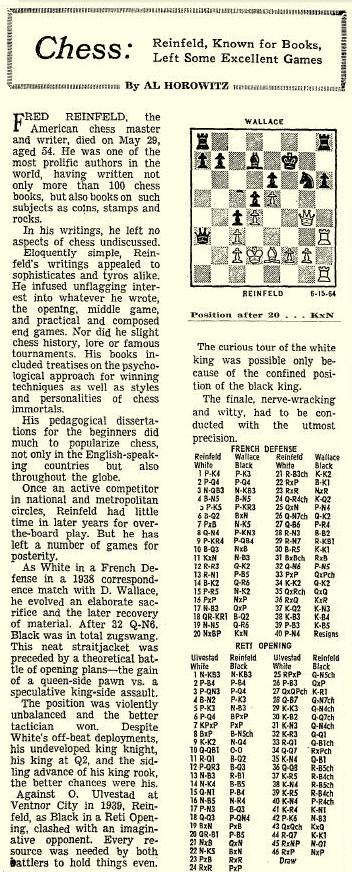

A question from Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) is whether anything is known about how Fred Reinfeld died, on 29 May 1964.

Information seems scarce. J.S. Battell’s obituary of Reinfeld on pages 193-194 of the July 1964 Chess Review gave no particulars and, remarkably, in the 1964 volume of Chess Life we see no mention at all of Reinfeld’s demise. The obituary on page 17 of the New York Times, 30 May 1964 did not specify the cause of death but reported that Reinfeld had died the previous day ‘at Meadowbrook Hospital’.

On page 209 of the July 1964 BCM S. Morrison stated that Reinfeld ‘died of a virus infection at his home in Long Island’. He was 54.

(5906)

Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA) draws attention to a passage in the chapter about Fred Reinfeld on pages 61-67 of The Fascination of Book Publishing by David A. Boehm (New York, 1994):

‘Fred had what he thought was a headache, which turned into an earache. On Saturday [sic] night, he fell asleep. He never woke up.

Death had been caused by an aneurysm.

Webster: “Aneurysm. A permanent abnormal blood-filled dilating of an artery, resulting from a disease of a vessel wall.”

Fred had been born with it and at 54 years of age, it had burst and flooded his brain.’

The reliability of the information is an open question, since the chapter has such dubious statements as the following on page 61:

‘Before Fred Reinfeld was six, he had mastered the chessboard ...’

Our Factfinder has an entry ‘Reinfeld, Fred (when he learned chess)’. In none of his contradictory claims did he profess familiarity with the game at such an early age.

(5937)

A few quotes from Why You Lose at Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

(5907)

‘The most devastating win ever achieved against a grandmaster’ was Fred Reinfeld’s description of the 12-move game Zukertort v Anderssen, Berlin, 1865 on pages 10-11 of Relax with Chess (New York, 1948). On pages 54-55 he called the 17-move game Flamberg v Důras, Abbazia (Opatija), 1912 ‘perhaps the most complicated contest of its length that has ever been played’.

A remark on page 124 also surprised us:

‘It was left for the brilliant young Breyer to pronounce that the first move was a disadvantage, presumably on the ground that White has to commit himself.’

Breyer’s alleged ‘last throes’ remark, it will be recalled, concerned White’s position after 1 e4.

(6223)

‘... the Hungarian Breyer claimed that in the opening position (with all the pieces and pawns still unmoved) White’s game was in the last throes.’

Source: Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1954), pages 74-75.

(6493)

The start of an article on pages 242-243 of the August 1954 Chess Review:

From Solitaire Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1962):

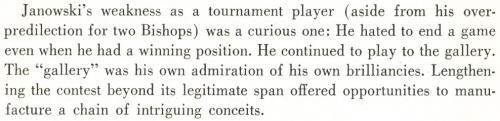

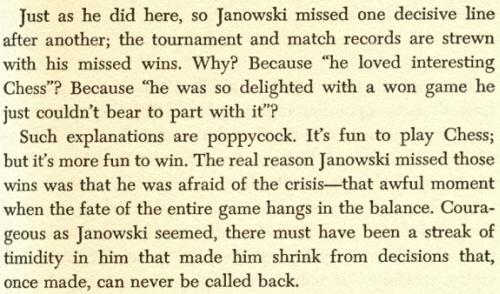

From page 17 of Why You Lose at Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

Other quotes on this Dawid Janowsky matter will be welcomed.

(6242)

We now add a ‘once’ account from page 72 of a book co-authored by Horowitz and Reinfeld, How To Improve Your Chess (Kingswood, 1955):

(6567)

Below is what Reinfeld wrote in ‘Emanuel Lasker: An Appreciation’ in his edition of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (Philadelphia, 1947):

(8233)

This position arose after 27 Rf1-d1 in Reinfeld v Alekhine, Pasadena, 1932.

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes a discrepancy over Black’s 27th move and the remainder of the game:

A) 27...Nc3 28 Rxd8+ Qxd8 29 Qd2 Qxd2 30 Nxd2 Bd5 31 e4 Be6 32 Bc4 Bc8 33 Bb5 Be6 34 Bc4 Bc8 35 Kf2 Kf8 36 Bb5 Be6 37 Bc4 Bc8 38 Bb5 Drawn. (Los Angeles Times, 26 August 1932, page A8.)

B) 27...Nb6 28 Rxd8+ Qxd8 29 Qd2 Qxd2 30 Nxd2 Bd5 31 e4 Be6 32 Bc4 Bc8 33 Kf2 Kf8 34 Bb5 Be6 35 Bc4 Bc8 36 Bb5 Drawn. (Various databases.)

We add that Version A was given on page 431 of the Skinner/Verhoeven volume on Alekhine, which also mentioned as a source pages 8-9 of the 11/1932 issue of The Chess Reporter. This version was published too on page 1885 of L’Echiquier, 28 November 1932.

Has Version B, which entails various errors in the final phase, ever appeared in an authoritative publication?

A hybrid version (27...Nb6 28 Rxd8+ Qxd8 29 Qd2 Qxd2 30 Nxd2 Bd5 31 e4 Be6 32 Bc4 Bc8 33 Bb5 Be6 34 Bc4 Bc8 35 Kf2 Kf8 36 Bb5 Be6 37 Bc4 Bc8 38 Bb5 Drawn) is on page 92 of The Games of Alexander Alekhine by R. Caparrós and Peter P. Lahde (Brentwood, 1992).

(6291)

From page 27 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

Reinfeld’s game against Rubinstein was played at the Marshall Chess Club in New York on 18 February 1928. Rubinstein’s opponents included E. Tholfsen (one of two winners) and M. Hanauer (one of two players who drew), and among the 20 losers were Reinfeld, H.R. Bigelow, W. Frere, B.M. Anderson, J.C.H. Macbeth and A.E. Santasiere. Source: New York Times, 20 February 1928, sports section, page 17.

Rubinstein’s loss to Tholfsen was given on page 261 of Akiba Rubinstein: The Later Years by J. Donaldson and N. Minev (Seattle, 1995).

Below is a picture of Rubinstein from opposite page 628 of the May 1927 issue of L’Echiquier:

(6518)

A further recollection by Reinfeld, from page 94 of his book Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘Many years ago I played against Rubinstein in a simultaneous exhibition. I was almost cross-eyed with reverence for the great man, and, in Frank Marshall’s classic phrase, “he beat me like a child”. One detail still lingers in memory. Though Rubinstein was a stocky man with stubby fingers, his hands maneuvered the chessmen with such elegance that I was spellbound.’

Which chess book contains the most hype? One promising contender (at least from the pre-Cardoza era) is Fred Reinfeld’s Beginner’s Guide to Winning Chess, which was first published in 1964, the year he died. Here is the back-cover of the 1994/2006 paperback edition from Foulsham (which used the spelling Beginners’):

There is plenty more inside concerning ‘the rarest of Grandmasters’. Page 6 (‘About the Author’) starts:

‘Fred Reinfeld was, as Dr M.W. Sullivan states in his introduction to Beginners’ Guide to Winning Chess, a brilliant chess player and “the leading writer on chess in the entire history of the game”. This is indeed saying a great deal, since chess has been played for more than a thousand years, but the overwhelming evidence is that the Sullivan statement is actually true!’

After a page in similar vein, Dr Sullivan takes over the loud-hailer for his introduction (pages 7-8). It begins:

‘Ours is no age for a universal genius, but Fred Reinfeld offers us a close approximation of the ideal. The quality and quantity of his books made him not only the finest chess author of his day, but also the leading writer on chess in the entire history of the game.

Of course, Fred Reinfeld was a brilliant chess player ... as great a writer as he was chess player.’

Much more could be quoted, but we merely observe that it was not one-way traffic. Dr Sullivan was the author of A Programmed Introduction to the Game of Chess, and it included a full-page encomium by Reinfeld which worked itself up to the following finale:

‘... this is the most revolutionary book ever written on chess – a work that is destined to have a profound influence on all worthwhile chess books of the future.’

(6585)

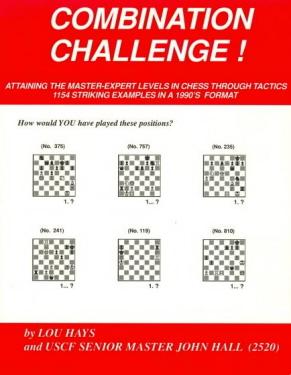

Who first pointed out publicly that Combination Challenge! by L. Hays and J. Hall (Dallas, 1991) was guilty of wholesale plundering from Fred Reinfeld’s 1955 book 1001 Brilliant Chess Sacrifices and Combinations?

We recall, but cannot currently trace, a 1990s magazine item which criticized Hays and Hall for misappropriating so much of Reinfeld’s work. One of the authors subsequently responded that, in fact, a (relatively small) number of the positions came from elsewhere, which prompted the magazine to make a sarcastic remark to the effect, ‘Well, that’s all right then’. Where did those exchanges appear?

The Reinfeld volume has also been published under the titles 1001 Chess Sacrifices and Combinations and 1001 Winning Chess Sacrifices and Combinations. No players’ names or venues were given, but many famous games were included. See, for instance, page 137 (and page 4 of the Hays/Hall monstrosity, which had a total of 1,154 positions).

(6886)

Left: Reinfeld (1955). Right: Hays/Hall (1991)

(6886)

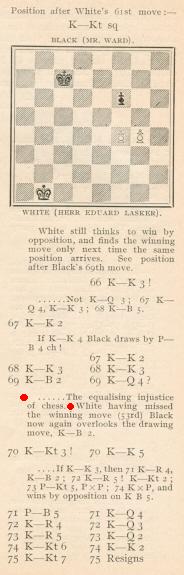

From an annotation on page 156 of the May 1961 Chess Review, in the magazine’s postal section (conducted by Jack Straley Battell):

‘... or, in the more erudite language of Dr Tartakower, “The equalizing injustice of chess”.’

A passage on page 251 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘... Bernstein made a point of what he called “the equalizing injustice of chess”. By this he meant, presumably, that the apparent unfairness of such a loss is canceled by a sequence of blunders: the player who finally pays for a mistake has probably escaped punishment for earlier mistakes. In the long run, undeserved victories will balance out with undeserved losses. (Of course, the term “undeserved” raises problems, for a mistake deserves to be punished.)’

It is indeed to Bernstein that the phrase is usually ascribed. See, for instance, pages 178-179 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood (Philadelphia, 1942) and pages 75 and 94 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951), to mention two books by Edward Lasker.

Even so, the earliest citation that we can offer at present is from Edward Lasker himself (with no reference to Bernstein), in his annotations to a game on page 301 of the July 1913 BCM:

(6912)

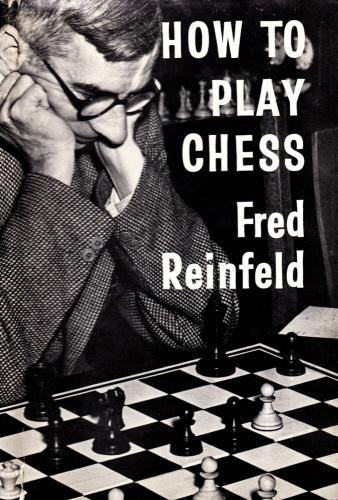

This is the front of the dust-jacket of Reinfeld’s How to Play Chess, which was published by Eyre & Spottiswoode, London in 1954 and reprinted in 1959. Elsewhere the dust-jacket states that the photograph was ‘reproduced by courtesy of Kemsley Picture Service’, but who is the player shown?

We have consulted Leonard Barden (London), who feels 60-70% sure that it is W.J. Fry. The winner of the Southampton championship ten times, Fry died on 29 October 1954 at the age of 58. Brief obituaries were published on page 116 of CHESS, 27 November 1954 and on page 382 of the December 1954 BCM.

Reinfeld’s book had been published in the United States in 1953 under the title The Complete Chessplayer, but with a different dust-jacket.

(7547)

The photograph shown in C.N. 7547 seems not to have been used until the 1959 reprint of Reinfeld’s book How to Play Chess. Below is the front of the dust-jacket of the original 1954 edition, with a shot of the famous game in which Alexander defeated Bronstein at Hastings:

(7569)

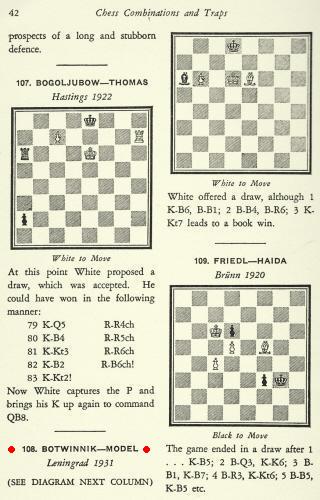

Below is page 42 of a book edited by Reinfeld, Chess Combinations and Traps by V. Ssosin (New York, 1936):

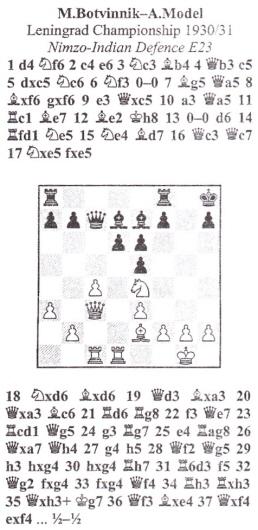

What more is known about the Botvinnik v Model position? We wonder whether it arose later in the game which was given in part on page 217 of Botvinnik’s Complete Games (1924-1941) and Selected Writings (Part I) (Olomouc, 2010):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 c5 5 dxc5 Nc6 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Bg5 Qa5 8 Bxf6 gxf6 9 e3 Qxc5 10 a3 Qa5 11 Rc1 Be7 12 Be2 Kh8 13 O-O d6 14 Rfd1 Ne5 15 Ne4 Bd7 16 Qc3 Qc7 17 Nxe5 fxe5 18 Nxd6 Bxd6 19 Qd3 Bxa3 20 Qxa3 Bc6 21 Rd6 Rg8 22 f3 Qe7 23 Rcd1 Qg5 24 g3 Rg7 25 e4 Rag8 26 Qxa7 Qh4 27 g4 h5 28 Qf2 Qg5 29 h3 hxg4 30 hxg4 Rh7 31 R6d3 f5 32 Qg2 fxg4 33 fxg4 Qf4 34 Rh3 Rxh3 35 Qxh3+ Kg7 36 Qf3 Bxe4 37 Qxf4 exf4, and the game was subsequently drawn.

(7549)

Some observations by Fred Reinfeld on pages 1-2 of The Secret of Tactical Chess (New York, 1958):

‘Chess has been subjected to several myths which need puncturing. One of the most prevalent is that some people become chess addicts, neglecting wife, children, job. I have played chess and known chessplayers for 35 years, and have not yet come across an instance of this kind. I have known people who passionately loved chess who were famous authors, eminent scientists, distinguished professionals in many fields, and the like. So I would say that the myth of the chess addict belongs to the same category of American folklore as does the myth of the absent-minded professor.’

(7960)

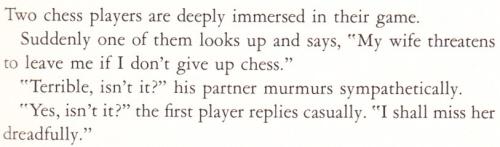

This well-known jape is, rather inaptly, the opening passage in Chess for Young People by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1961), page 3.

Page 14 of another Reinfeld book published the same year, The Joys of Chess, also gave the story, the first player being described as an Englishman. That article of Reinfeld’s, ‘32 Ways to Go Crazy’, was reprinted from Esquire, March 1953.

(8287)

From B.H. Wood’s column in the Illustrated London News, 30 March 1963, page 482:

‘I know of only one book devoted to the saving of lost positions; that is, not unexpectedly, by Fred Reinfeld, who must in the course of his lifetime have racked his brain to think what he could write about next. (His enormous output once prompted David Bronstein to remark that, whilst — — [Wood’s dashes] might possibly be the best writer of chess books in the English language, Fred Reinfeld was obviously the best lightning-chess-writer.) Illuminatingly, this book is one of Reinfeld’s very latest, showing clearly that it is one of the last subjects that even occurred to such a prolific writer.’

And from Wood’s column on page 114 of the 28 May 1977 issue:

‘It was Flohr, I think, who compared him [Golombek] with Reinfeld, who also wrote a great many chess books, describing Reinfeld as the world’s worst lightning chess writer, Golombek as the best (lightning chess is the term for chess played at an average of a few seconds per move). The assessment is hard on Reinfeld; Bob Wade has remarked again and again how poorer players find him helpful. It is kind to Golombek, whose books sometimes exhibit a smooth sameness, who had one rather egocentric period and who can find it difficult (who does not?) to avoid repeating himself.’

Is anything further known about the views attributed to Bronstein and Flohr?

(8364)

‘It is one of the most enticing riddles of the centuries-old attractiveness of chess that a phenomenon so deeply rooted in the materialistic and rapacious should offer a satisfaction which is so deeply spiritual and so innocent of harm to one’s fellow man.’

Source: page 119 of How to Improve Your Chess: Second Steps by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952).

(8404)

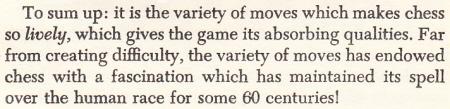

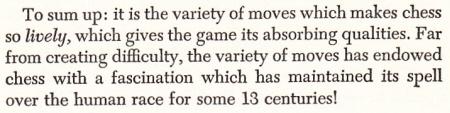

From page 7 of Learn Chess Fast! by S. Reshevsky and F. Reinfeld (London, 1952):

Concerning the reference to ‘some 60 centuries’, we have seen other editions of the book (originally published in the United States in 1947) which have ‘some 13 centuries’:

Readers’ help is requested to determine the chronology of that textual change in the various editions published on both sides of the Atlantic.

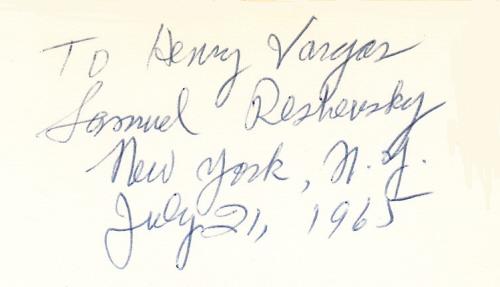

Below is Reshevsky’s inscription in our copy of a New York edition, published by David McKay Company, Inc. (‘Sixth Printing January 1958’):

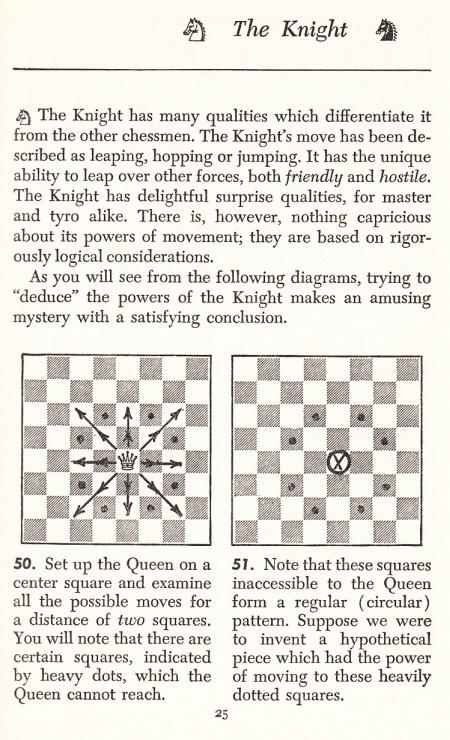

Another curiosity, on pages 25-26, is the presentation of the knight’s move in the captions to diagrams 50-53:

Have many other instructional works explained the knight’s move in this way, i.e. by reference to squares inaccessible to the queen?

(8431)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) mentions that the first US edition of the Reshevsky/Reinfeld book Learn Chess Fast! (published by David McKay Company, Philadelphia in 1947) had the ‘60 centuries’ version with regard to the history of chess.

When preparing C.N. 8431 we were unable to trace an edition of the book which, according to Douglas A. Betts’ bibliography (page 116), was issued by Pitman in 1948. Our UK edition was published by Hollis and Carter, London in 1952.

Mr Clapham comments:

‘Betts states that the book was “issued” by Pitman rather than published by that company, and it is possible that Pitman imported the McKay books and distributed them in the United Kingdom. Pitman also “issued” Chess by Yourself by Fred Reinfeld (Betts 11-41). My copy of the latter was published by McKay (copyright date: 1946) but was almost certainly issued in England as it has the CHESS, Sutton Coldfield sticker.

Another US book imported and issued/published by Pitman was Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine, published by Chess Review, New York in 1945. My copy has Chess Review on the spine, but the original title page has clearly been removed and replaced with another including the imprint of Sir Isaac Pitman.

A brief review of Learn Chess Fast! was published on page 269 of the August 1948 issue of CHESS, mentioning both McKay and Pitman. The book is also included in various advertisements for Pitman books and on dust-jackets of the company’s books, such as Walter Korn’s The Brilliant Touch (London 1950):’

Below is the title page of one of our copies of the first (1942) edition of The Immortal Games of Capablanca by Fred Reinfeld, with a ‘Distributed by Pitman’ sticker:

(8447)

From a postcard which David Hooper sent us on 23 August 1975:

‘[X – we omit the individual’s name] should be ignored, given enough rope he will hang himself. History will accord him no place. I have a little sympathy for Reinfeld. He started with some serious books, found they didn’t pay, that the public wanted drivel (How to win in ten moves) and American pace necessitated mass production of drivel, he developed contempt of chessplayers, including many champions. His Lasker book was good, but sales low and no sequel possible. He had a rapid, keen mind, and found chess masters altogether narrow and often stupid. I think he wrote the Marshall book which makes Marshall look like a moron which is not a bad description anyway. He had a fine mind and had to write drivel to live, and lost all the joy of doing a task well.’

(8436)

Addition on 17 August 2018: The individual in question was James Schroeder.

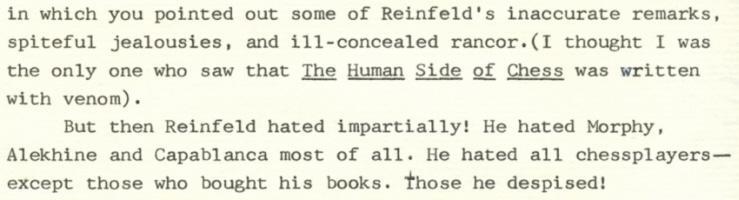

C.N.s 644 and 5036 quoted some comments to us about Reinfeld from Irving Chernev, in a letter dated 19 January 1977:

‘I thought I was the only one who saw that The Human Side of Chess was written with venom. But then, Reinfeld hated impartially! He hated Morphy, Alekhine and Capablanca most of all. He hated all chessplayers – except those who bought his books. Those he despised.’

The remarks were also given on page 265 of Chess Explorations, where we added:

On page 127 of America’s Chess Heritage, Walter Korn reported that in 1950 he had questioned Reinfeld about the contrasting quality of his early and late writing. Reinfeld replied: ‘In those days I played and wrote seriously – and got nothing for it. When I pour out mass-produced trash, the royalties come rolling in.’

In C.N. 793 a correspondent in Australia, Bob Meadley, submitted a letter dated 14 January 1965 which Fred Reinfeld’s widow, Beatrice, wrote to C.J.S. Purdy, the Editor of Chess World:

‘I’d like to make a correction – but you need not print it, it does not matter now, but it might give you some picture of the man. The reason Mr Reinfeld wrote so much was that he did not have a steady, or indeed any other, job. He devoted himself entirely to study and writing on subjects that interested him. He had the capacity to do many things at once and he had several desks on which he worked at different projects. No matter what they were, there was always a chessboard there with a magazine, or a book, so that he could turn aside from his work to play over a game or study a position that intrigued him.

You may think his output of chess books was large. But I have files and files of annotated games and positions which were never published. It was not by choice that he gave up writing chess books of the depth of his early ones, which he published himself under the imprint of the Black Knight Press. Fred’s popular books brought many people to a deeper understanding of chess than they otherwise would have had – and we must not look down our noses at the learners and average players. The masters may look down their noses at these books, but we knew that they meant a great deal to many people who did not aspire to tournament play – was it Tarrasch who said something to the effect that “chess, like music” had the power to make men happy”? In his way my husband brought that happiness to many people. He would have preferred to continue to write books like The Human Side of Chess, or his Limited Editions, or his pamphlets on the openings and endings, but they were beyond the average player – and the masters, who complain about his simpler books, certainly gave him no encouragement. So the chess world was indeed a tragic world for him in a sense. However, the breadth and depth of his other interests kept him too busy to worry about that.’

The back of the dust-jacket of How To Get More Out Of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1957).

(8436)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam BC, Canada) recalls that after Reinfeld died Al Horowitz’s column in the New York Times commented that Reinfeld infused unflagging interest into whatever he wrote.

To complement C.N.s 5906 and 5937, we give below the full article, from page 26 of the 15 June 1964 edition of the New York Times:

(8446)

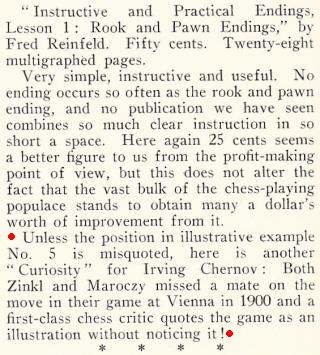

In an article presenting his new edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System Fred Reinfeld wrote on page 208 of the July 1949 Chess Review:

Can information be found about Reinfeld’s game against Cohen?

Reinfeld also mentioned his visit to the New York, 1927 tournament on page 161 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games (New York, 1952), in the chapter on Capablanca:

‘The other masters were so clearly outclassed that comparison was piteous. I attended the tournament one day to catch a glimpse of the grandmasters. Capablanca looked sleek, poised, quite sure of himself. The others were fearfully nervous – Sorcerer’s Apprentices, all of them, in the presence of the master magician. In any other man, Capablanca’s air of assurance would have made a distasteful impression – but not in his case: he looked so distinguished, so authentically a great man, that the predominant reaction was one of awe.’

(8805)

From the same Chess Review article by Reinfeld referred to in the previous item: