Edward Winter

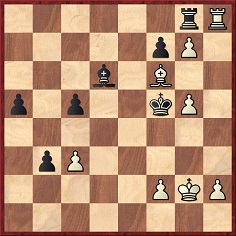

Wanted: little-known cases of resignation in a winning position. Here is a straightforward early one (Paris, 1846) in which ‘a distinguished English Amateur’ unnecessarily resigned against Kieseritzky. It appeared on page 327 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 16 October 1847.

Play continued 28 Rxg8 (‘28 c4 would have won the game directly.’) 28...b2 and White resigned. (‘A remarkable termination, the winning player surrendering the victory! Annoyed at not having advanced his c-pawn to stop the onward march of Black’s pawn, White hastily gave up the game at the moment it was within his grasp. He had simply to play 29 Rb8, and he must have won without difficulty...’) The magazine points out the line 29...Bxb8 30 g8(Q) b1(Q) 31 Qh7+.

(2123)

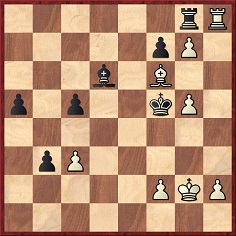

E. Sonnenschein gave this position on page 236 of CHESS, 14 March 1938:

Players and occasion?

Sonnenschein wrote: ‘A friend of mine played Bh6 in the diagrammed position and, when Black replied ...Rfe8, resigned. He could have won the game by a splendid sacrificial line 1 Bxf7+ Kxf7 2 Rf1+ Kg8 3 Rf8+ Rxf8 4 Qg7 mate.’

Although Sonnenschein does not stipulate that he was Black, such is stated by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss on page 90 of Blunders and Brilliancies (Oxford, 1990).

(2144)

Two other cases of resignation despite having a won game:

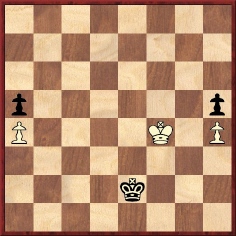

The position below comes from page 297 of issue 26 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, published in 1931. It is from a ‘recent’ game between W.H. Watts and J.A.J. Drewitt in the London Chess League:

Black played 1…Qxf6+ and Watts resigned, instead of winning on the spot with 2 g5+. (Black, however, did not wish to accept the resignation; the game was continued, and White won.)

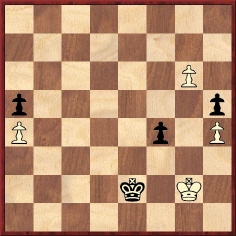

The second diagram shows the final position in a game between Urban and E. Zimmer, Karbitz, 1924 as reported on page 5 of the January 1935 Chess Review:

Believing that his only choice lay between losing his queen and being mated, White resigned. He could have won with 1 Bg6.

(2661)

A short game which has often been resigned by Black at move six is 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Bc4 Be7 5 c3 dxc3 6 Qd5.

This was discussed in C.N.s 99, 194 and 1068, the illustrative game being Midjord (Faeroe Islands) v Scharf (Monaco) in round 5 of the finals of the 1974 Nice Olympiad. As is well known, except to those who do not know it, Black can stay in the game with 6…Nh6 7 Bxh6 O-O.

C.N. 1068 reported that in his book Frank J. Marshall P. Wenman (Leeds, 1948) gave (on pages 160-161) a simultaneous game (Liverpool, 1912) between Marshall and J.R. Whiting which began 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 Nc6 5 Nf3 Be7 6 Qd5 Nh6 7 Bxh6 O-O 8 Nxc3 Nb4 9 Qd2 gxh6 10 a3 Nc6 11 Qxh6 and was drawn at move 28. We have yet to find corroboration of the game-score in a contemporary source.

Two old instances of the miniature are added here. The first comes from a match between W.M. DeVisser (Brooklyn Chess Club) and L.W. Jennings (Ocean Hill Chess Club) in Brooklyn on 4 March 1922. The game went 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Be7 5 c3 dxc3 6 Qd5 and ‘Jennings paid the penalty for being over-courteous to his opponent and resigning prematurely’ (American Chess Bulletin, March 1922, page 49). The Bulletin said that Black should have continued with 6…Nh6 7 Bxh6 O-O 8 Bc1 Nb4 9 Qd1 c2, recovering the piece.

The second six-move game (with the same move order) was between Schwarz (Munich) and Düren (Dortmund) in Frankfurt on 10 September 1938. The score was published on page 294 of the 1 October 1938 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter, which took the opportunity to reiterate some analysis given on page 180 of its 15 June 1935 issue, i.e. the fact that the theoretical line 8…Nb4 9 Qh5 Nxc2+ 10 Kf1 Nxa1 11 h4 with a mating attack does not take account of the strong interpolation 9…d5.

(3075)

On page 10 of his 1968 book TV Chess Koltanowski wrote that when he was a teenager in Belgium he won a match (+3 –1 =1) against Frédéric Lazard and that his victory in the third match game went as follows: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nd7 4 Bc4 Be7 5 dxe5 dxe5 6 Qd5 Resigns.

Corroboration is sought from contemporary sources.

(3076)

Regarding the Marshall v Whiting game, see C.N.s 6963 and 8345.

The following addition (Cukierman v Lazard, Paris, 1929) comes from pages 105-106 of The Quiet Game by J. Montgomerie (London, 1972):

‘In this position Black played 32...Rxg2+ 33 Nxg2 Qf2+ 34 Kh2 e3 35 d5 Qg3+ 36 Kh1 Rf2, and White resigned. All very forceful play by Black and a just result. But there is a flaw. Instead of resigning White should have continued 37 Rg4 and if 37...Qxh3+ 38 Kg1 Qxg4 39 Qxc7+ Ka8 40 Qd8+ Bc8 41 Rxc8+ Kb7 42 Rc7+ Ka6 43 Qc8+, winning comfortably. Instead of 36...Rf2 Black should have played 36...Bxd5, so that if 37 Rg4 Bxg2+, etc.’

The full game is given below, from page 30 of the 1999 Chess Player booklet which included all available games from the tournament:

Josef Cukierman – Frédéric Lazard

Paris, June 1929

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 d4 fxe4 5 Bxc6 dxc6 6 Nxe5 Qh4 7 Be3 Bd6 8 Qd2 Be6 9 Bg5 Qh5 10 Nc3 Nf6 11 Ne2 O-O-O 12 Ng3 Qe8 13 Qa5 Kb8 14 O-O c5 15 c3 Bc8 16 Nc4 b6 17 Nxd6 Rxd6 18 Qa3 cxd4 19 Bf4 Rd8 20 cxd4 Bb7 21 Rac1 Rd7 22 Rc4 Qg6 23 Rfc1 Nd5 24 Be3 h5 25 Qa4 Rf7 26 Qc2 h4 27 Nf1 Rhf8 28 f4 Nxf4 29 Bxf4 Rxf4 30 Ne3 Qf6 31 h3 Rf2 32 Qc3 Rxg2+ 33 Nxg2 Qf2+ 34 Kh2 e3 35 d5 Qg3+ 36 Kh1 Rf2 37 White resigns.

The booklet quoted the game from L’Action française, which also mentioned that White’s resignation was erroneous and asked, ‘Is it luck if you are able to see more than your opponent?’

(3720)

White to move

C.N. 2202 (see page 15 of A Chess Omnibus) gave this position, which one modern source labelled ‘Ahues v Hans Müller, Berlin, 1920’. After White’s 1 Qxf6 Black resigned, whereas he could have won with 1...Qg4.

Our inability to find the position in any 1920s source was mentioned in C.N. 2202, but now we note that it was given, courtesy of the Deutsche Schachblätter, on page 111 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, July 1923. The heading was vague: ‘Aus einer von Meister Ahues vor Jahren gespielten Partie’.

(3918)

From Karsten Müller (Hamburg, Germany):

‘The final position of Colle v Grünfeld, Carlsbad, 1929 is often given with the black king on e2, allowing Grünfeld to draw with 77...Kd3. See, for instance, page 18 of Endgame Tactics by G.C. van Perlo (Alkmaar, 2006). However, I would expect Black’s king to be on f1 in the final position. Can you shed any light on the matter?’

Above is the position as given in the Dutch book, which states that Black resigned here although he could have drawn with 77...Kd3 78 Kg5 Ke4 79 Kxh5 Kf5.

The game appeared, with annotations by Colle, on pages 384-385 of IV. Internationales Schachmeisterturnier Karlsbad 1929 (Vienna, 1930), where the conclusion was presented as follows:

71 g7 f3+ 72 Kh2 f2 73 g8(Q) f1(Q) 74 Qc4+ Ke1 75 Qxf1+ Kxf1 76 Kg3 Ke2 77 Kf4 Resigns. This corresponds to the final position as given by van Perlo.

Colle’s notes did not mention that Grünfeld resigned in a drawn position. Was this an omission/oversight or did the drawing opportunity never arise because the game-score in the tournament book was faulty? If White’s 72nd move had been Kg3, rather than the odd-looking Kh2, there would have been no draw for Grünfeld because after the exchange of queens the white king would reach f4 at move 76, and not move 77.

The immediate question is thus whether a contemporary source exists which gave White’s 72nd move as Kg3.

(4677)

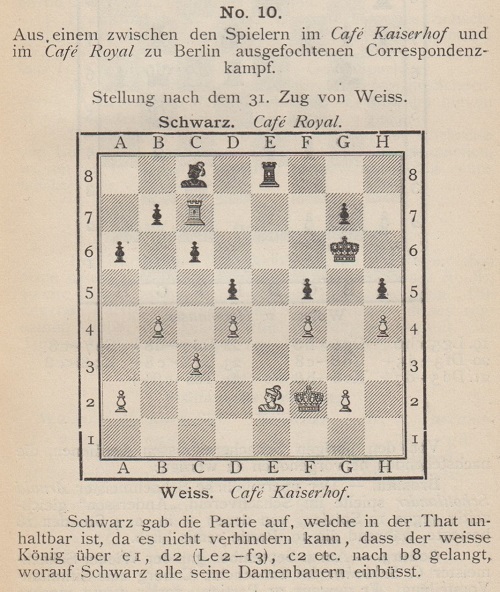

From page 37 of Chess Review, January 1947 (an article by I.A. Horowitz):

‘In a match game with Grob, Flohr resigned when he was a piece to the good. He mistakenly believed that he could not stop a mate in one. In a similar situation, Fine resigned to Kevitz when he could force an easy draw by perpetual check.’

No details were given.

As indicated in the Factfinder, Flohr v Grob has been discussed in C.N. several times. The other game, played in the Metropolitan League, is on pages 69-70 of the April 1932 American Chess Bulletin:

Alexander Kevitz (Manhattan Chess Club) – Reuben Fine

(Marshall Chess Club)

New York, 16 April 1932

Dutch Defence

1 c4 f5 2 d4 Nf6 3 g3 e6 4 Bg2 Bb4+ 5 Nc3 O-O 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 Ne4 9 Qd3 b6 10 Ba3 Re8 11 d5 Na5 12 Bb4 Nc5 13 Qd4 d6 14 dxe6 Nxe6 15 Qd2 Bb7 16 Bxa5 bxa5 17 Rab1 Be4 18 Rb5 c6 19 Rb2 Nc5 20 Nd4 Bxg2 21 Kxg2 Qd7 22 Rfb1 Qf7 23 Nxc6 Qxc4 24 Qxd6 Na4 25 Rb7 Qe4+ 26 Kg1 Nxc3 27 h3 f4 28 Qc7 Qg6 29 Ne5 Rxe5 30 Qxc3 Rae8 31 Qc4+ Kh8 32 Qxf4 Rxe2 33 Rb8 h6 34 Rxe8+ Rxe8 35 Rc1 Qe6 36 Kh2 Qxa2 37 Rc7 Kg8 38 Qd4 Resigns.

C.S. Howell wrote in the Bulletin:

‘A most entertaining game. I am informed that both players were hard pressed for time. As is usual in such cases, the more experienced player wins out. Fine, a truly promising young player, here overlooks 38...R-K4! If White captures the rook, 39...QxPch draws.

Pillsbury once gave me a very useful bit of advice regarding clock difficulties. It was to note the time on the score-sheet after I made each move; after the game to play it over and try to explain to myself why I took so long to make obvious moves or ones that my chess instinct should have indicated. It is good discipline and will help young players who get into trouble with the clock.’

(8585)

Position after 38 Qd4

From Lonnie Kwartler (Chester, NY, USA):

‘The defense suggested for Fine, 38...Re5, prolongs the game, but White still has a win with 39 Qd8+ Kh7 40 Qf6 Rg5 41 h4 Rg6 42 Qf5. (This position can be reached with 39 Rc8+ four moves later.) Of course, 38...Re5 would have been a good try, and if Black does not fall into mate White is “limited” to a clearly won endgame. Black cannot stop White’s attack without exchanging queens.’

(8588)

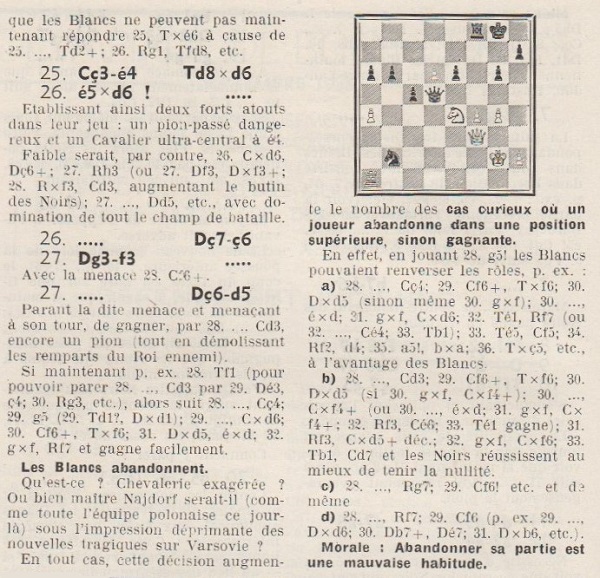

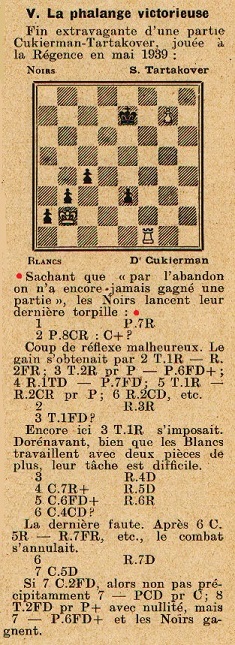

On pages 120-122 of the May 1946 issue of Le monde des échecs Tartakower annotated the game Najdorf v Cortlever from the 1939 International Team Tournament in Buenos Aires. His concluding notes:

The game was also given on pages 226-227 of Chess World, 1 November 1946, under the title ‘Resigns??’. After quoting Tartakower’s final note (including ‘Moral: Resigning is a bad habit’), Purdy commented:

‘We hope beginners will not use Dr Tartakower’s witticism as an excuse for dragging on hopelessly lost games. Friendly games, by the way, should be resigned earlier than match games. By resigning quickly, you give time for another game – more fun and more practice.’

(9400)

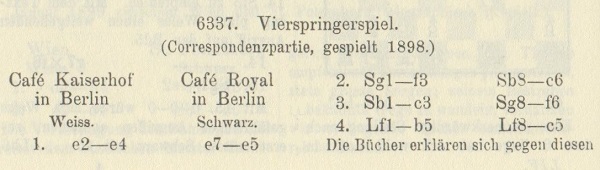

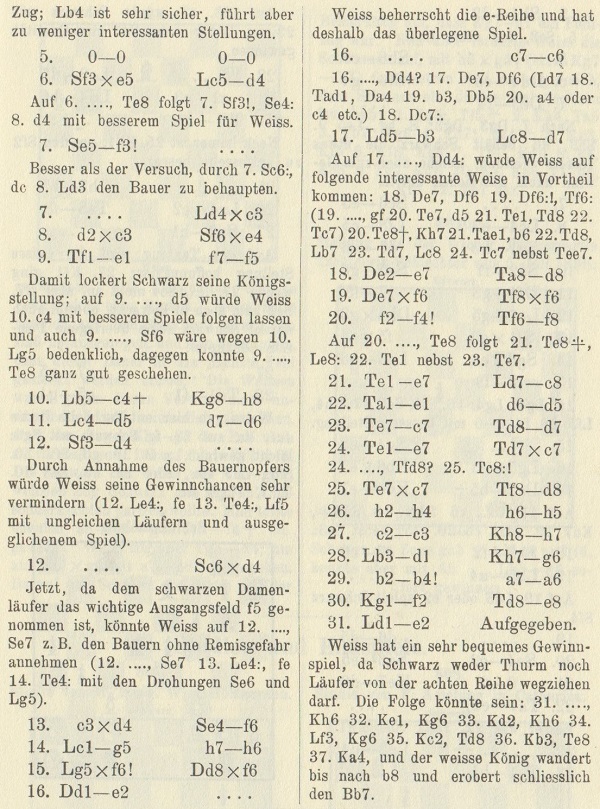

After 31 Be2, was Black justified in resigning?

(10992)

After 31 Be2 Black resigned on the grounds that a decisive march by the white king to b8 is unpreventable.

The game, played by correspondence in Berlin between the Café Kaiserhof and the Café Royal, was published on pages 50-51 of the February 1899 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bc5 5 O-O O-O 6 Nxe5 Bd4 7 Nf3 Bxc3 8 dxc3 Nxe4 9 Re1 f5 10 Bc4+ Kh8 11 Bd5 d6 12 Nd4 Nxd4 13 cxd4 Nf6 14 Bg5 h6 15 Bxf6 Qxf6 16 Qe2 c6 17 Bb3 Bd7 18 Qe7 Rad8 19 Qxf6 Rxf6 20 f4 Rff8 21 Re7 Bc8 22 Rae1 d5 23 Rc7 Rd7 24 Re7 Rxc7 25 Rxc7 Rd8 26 h4 h5 27 c3 Kh7 28 Bd1 Kg6 29 b4 a6 30 Kf2 Re8 31 Be2 Resigns.

From page 13 of Schachjahrbuch für 1899. II. Theil by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1900):

Richard Forster (Zurich) writes:

‘The best line may be 31...Rh8 32 Bf3 Kf6, and now if 33 Ke2 then 33....g6 34 Kd2 Rg8 35 Kc2 Ke6 36 Kb3 Kd6 37 Rh7 b6. The computers suggest 33 a4 g6 34 b5, which wins a pawn and probably gives very good winning chances, but the game is not yet over.’

(10997)

Information about the famous ‘Mieses v Post’ position is in C.N.s 11378 and 11389.

From page 12 of the Universities Chess Annual, November 1950:

Black to move

This position arose in the game between J.E. Littlewood and M.J. Egginton in round ten of the inaugural individual championship of the British Universities Chess Association, held at Trinity College, Cambridge on 17-28 July 1950:

‘Egginton resigned in the diagram position, but Kt-B7ch would have won for him.’

Nothing more was said about the game.

(11674)

Jon Ludvig Hammer is one of the best commentators on YouTube and Twitch, blending lucidity with dry whimsy.

During his live commentary on the seventh-round women’s match between Sweden and Paraguay at the Budapest Olympiad on 18 September 2024, he discussed this position (Pia Cramling v Jennifer Pérez), starting at about 4:03:30 in the transmission:

White has played 46 Rb7-c7, and Black resigned.

Instead of surrendering, why not produce some fireworks with 46...Qa6 47 Rxd7+ Kh8 48 Qh6 (threatening mate on the move) 48...Qxf1+ 49 Kxf1 Rc1 mate?

Hammer gave the answer: 49...Rc1 is not mate.

(12024)

Concerning Midjord v Scharf, Nice, 1974 (1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Bc4 Be7 5 c3 dxc3 6 Qd5 Resigns), see page 55 of Chess Facts and Fables and C.N.s 6963 and 8345. One of the most famous resignations in chess history is discussed in Steinitz v von Bardeleben. Claims that Alekhine resigned by throwing a chess piece are examined in Chess with Violence.

The view of Tarrasch was given on page 388 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘... there are some masters, unfortunately notable among them being Marshall, who are quite devoid of any sense of tact, and who make it a matter of principle to continue playing with stupid obstinacy in the most hopeless positions. Such procedure makes them themselves look ridiculous, and is degrading to the tourney as a spectacle.’

Tarrasch expressed these sentiments in Die Schachwelt, and they were reported on page 204 of the May 1912 BCM. He was referring to his 90-move win against Marshall at San Sebastián, 1912, in which the American fought out an ending with a rook against rook, bishop and two pawns.

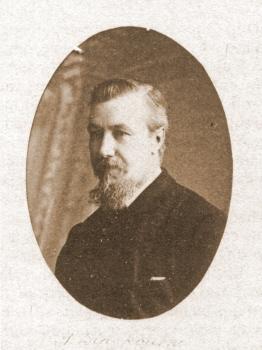

The Christmas 1969 issue of CHESS had a quiz which claimed (on pages 116 and 125) that D. Janowsky ‘was so annoyed at reaching a losing position against Sir George Thomas’ that he ‘did not arrive for resumption of play, and the tournament director upon opening the envelope merely found the word “abandonnent”.’ No occasion was specified or source given, but it seems that Janowsky’s only loss to Sir George Thomas was at Marienbad, 1925 – an 88-move game given on pages 96-97 of the tournament book.

Dawid Janowsky

In an article entitled ‘Unconventional Surrender’ on page 55 of the February 1950 Chess Review Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld stated that such an incident occurred in the game between Müller and Yates at Kecskemét, 1927, and that White sealed ‘aufgegeben’. See page 130 of Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951). Kmoch was a participant in the tournament.

(4942)

Page 49 of The Delights of Chess by Assiac (London, 1960) has come to our attention:

The two masters played each other twice in a 1926 tournament in Ghent, but both games were drawn.

(5287)

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) refers to page 177 of Secrets of Grandmaster Chess by John Nunn (London, 1997), which states that at the Malta Olympiad in 1980 Tony Miles sealed ‘Resigns’ in his game against Lajos Portisch.

(4947)

Joseph Henry Blackburne

The following paragraph appeared on page 248 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, April 1905:

‘The Cheltenham Chronicle is authority for the remark that once upon a time Blackburne was playing a simultaneous series in one of the English chess clubs and upon his opponent replying to his P-K4 with P-K3 he tried to be facetious and said, “Ha, I resign”. The player promptly replied, “Thank you, Mr Blackburne, I accept. Mr Secretary, will you kindly score a win for me.” And the game was so scored.’

We recall that an earlier version of the yarn was different. From page 232 of the May 1891 BCM, in an article on Purssells, London (‘one of the greatest chess rooms in the world’):

‘Blackburne was once playing here with a very irascible old gentleman, who was most particular in enforcing all rules of the game and, when in a certain humour, could not take a joke. It was his own first move, and he played P-K3. “Ah”, said Blackburne, “now I resign.” “All right”, said his touchy opponent, “that’s one game to me”, and nothing, as Blackburne knew, would alter that determination, so it was duly scored. This is the shortest game on record. Blackburne was beaten in one move.’

(4963)

C.N. 1792 cited from page 3 of the Winter 1988 issue of Chess Post a neat message for use in correspondence chess:

‘If resigns, thank you for the game.’

In C.N. 2426 the late David Pritchard referred to a postcard on which a player wrote his latest move and added:

‘If Rd7, resigns.’

(5249)

White, to move, resigned

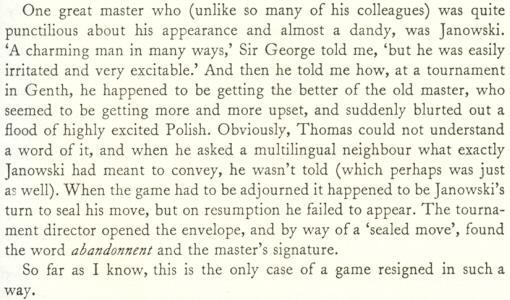

From page 92 of the 1 April 1949 issue of Chess World:

(6884)

As shown above, C.N. 6884 reproduced this advice from page 92 of the 1 April 1949 Chess World:

‘... never resign just to show you can see your opponent’s threats.’

C.J.S. Purdy reverted to the matter on page 184 of the August 1961 issue of his magazine:

‘Never play quickly against a slow resigner just to show how easy it is. Likewise, never resign prematurely just to show you recognize your game is lost. In other words, showing off doesn’t pay.’

(11430)

An article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, which was published in the March 1981 Newsflash and on page 66 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘That incorrigible chess satirist, W.R. Hartston, dealing with “etiquette for chessplayers on losing”, recommends (Soft Pawn, page 41) that resignation should be accompanied by “a pertinent congratulatory message” and gives as a textbook example for our guidance: “I hope that makes you happy, you smug bastard.” An alternative worth consideration (which the BM once actually overheard in a League Match) is “Fancy losing to you”, bringing home to the “bastard” that he was not only smug but incredibly lucky.

Chess history records many instances of gracious conduct in adversity. In 1859 the illustrious Henry Thomas Buckle, whose stature earned him a “special licence” as a “disagreeable man”, visited the Boulogne Chess Club, where he was invited to play a total stranger (who was, in fact, Thomas Winter Wood, an able player and the father of Mrs W.J. Baird, the lady problemist of the 1890s). “What odds shall I give you?”, growled the great man brusquely. Observing Winter Wood’s raised eyebrows, Buckle barked out “Never play otherwise” and peremptorily removed his KBP, adding: “I’ll give you pawn and move”. After several exchanges Buckle found himself still a pawn down without compensation, whereupon he abruptly announced: “I don’t feel well – I’ll give it up.” Winter Wood remarks that the great historian was indeed in poor health at the time, and died three years later. [See page 12 of the January 1898 BCM.]

Coming down to resignations at Badmaster level, Monsieur Leduc, a knight player of the Café de la Régence in the 1830s, ended up in a dead drawn position with king against king and pawn, but his opponent (a cantankerous person ignorant of the principles of the opposition) insisted on playing on. After a great deal of ill-natured banging of kings to and fro at a furious rate, the inevitable happened, and poor M. Leduc thumped his unfortunate monarch onto the wrong square. “There”, brayed the triumphant ignoramus, “I told you I would win.” “You have won”, shrieked M. Leduc, “because you do not know how to play.”

The Badmaster, though an experienced resigner, must admit that on one occasion he himself “turned nasty”. His opponent was an exuberant foreign youth from an Eastern clime and the BM, after playing (as he always does) a rook below his real strength, was on the verge of yielding up the ghost with his usual sepulchral grace, when his antagonist presumptuously came to his assistance: “I sink dis is where you give it in. I haf two lovely passed pawns – is it not goodbye?” “Young man”, rejoined the outraged BM, “I have given you no Power of Attorney to resign games on my behalf.” Needless to say, this brilliant shaft was completely wasted on the obtuse visitor, who broke into a beaming smile: “Oh, velly good, sir. Velly good indeed. You lose, and yet (how say you it?) you pull good sporty crack, yes?”’

(7750)

See too Excuses for Losing at Chess.

Chess literature is awash with claims that Tartakower ‘once’ wrote that nobody ever won a game by resigning, but never once have we found proof.

The matter was raised by Daniel King (London) in C.N. 2356 and discussed in C.N. 3374 (see page 345 of A Chess Omnibus and page 337 of Chess Facts and Fables). The latter item quoted the following from page 121 of Tartakower’s Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924), in a note to Black’s 33rd move in Maróczy v Chajes, Carlsbad, 1923:

‘Der transatlantische Meister Chajes steht auf dem Standpunkt, dass man durch das Aufgeben noch keine Partie gerettet hat.’

We commented in C.N. 3374:

This may be translated as ‘The transatlantic master Chajes is of the view that no player has ever saved a game by resigning’, it being unclear whether Tartakower was suggesting that Chajes himself had made the remark in question.

(9857)

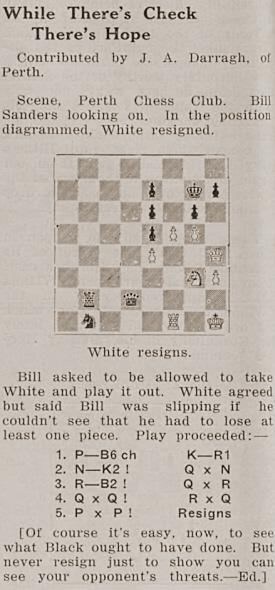

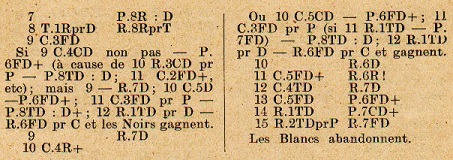

An addition from Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) is the conclusion of Cukierman v Tartakower, Paris, 1939, annotated by the latter on pages 102-103 of La Stratégie, July 1939:

(9867)

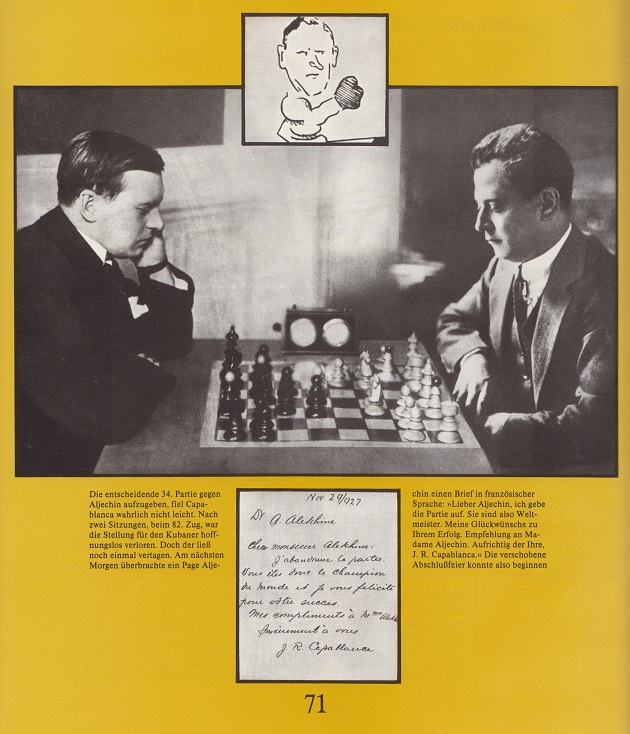

Richard Jones (Bologna, Italy) raises the question of whether Capablanca was a poor loser, and particularly in the immediate aftermath of his match defeat by Alekhine in 1927.

As shown on pages 202-206 of our monograph on the Cuban, his public statements about Alekhine’s victory were generous. The conclusion of the match was discussed on pages 348-350 and 521 of Miguel A. Sánchez’s 2015 book on Capablanca, but a properly documented account of what happened in Buenos Aires at the end of November 1927 remains to be written. With optimum use of source material, the chess historian must try to show what is certain, what is probable, what is unlikely and what is untrue, and at every stage the reader is entitled to ask, ‘Where did that come from?’ With erratic use of source material, Miguel A. Sánchez often makes do with a mixture of facts, assertion, imagination and speculation.

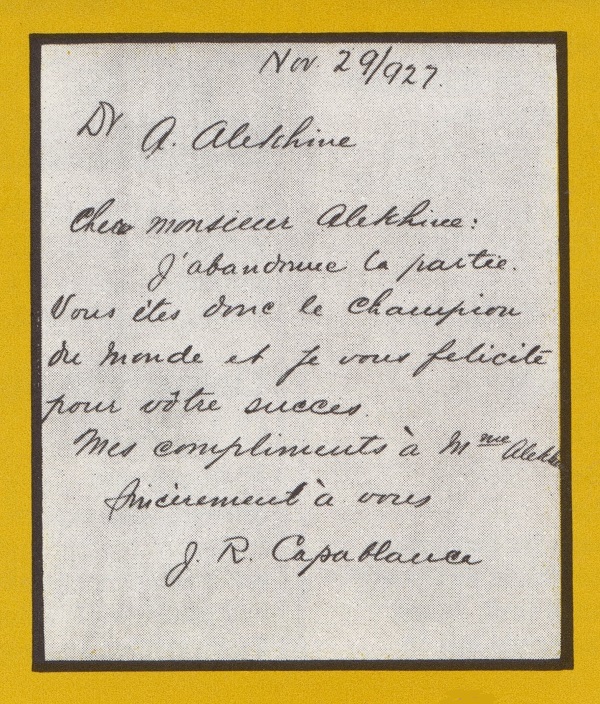

Concerning Capablanca’s letter of resignation of game 34, we do not know when the original first became public. One book which reproduced it (on a page chiefly comprising the fake Alekhine-Capablanca photograph) was Umkämpfte Krone by R. Stolze (East Berlin, 1986):

Correct French would have been desirable.

On page 521 of his book Sánchez characteristically referred to ...

‘... the text, originally written in French, although with some grammatical inaccuracies (probably because of Capablanca’s state of mind) and later fixed ...’

(10022)

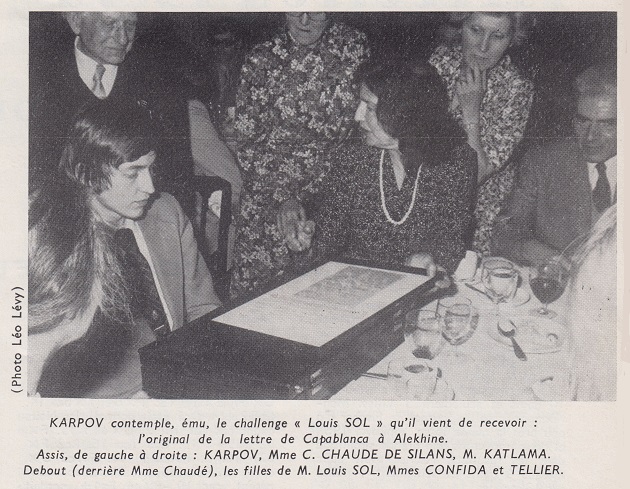

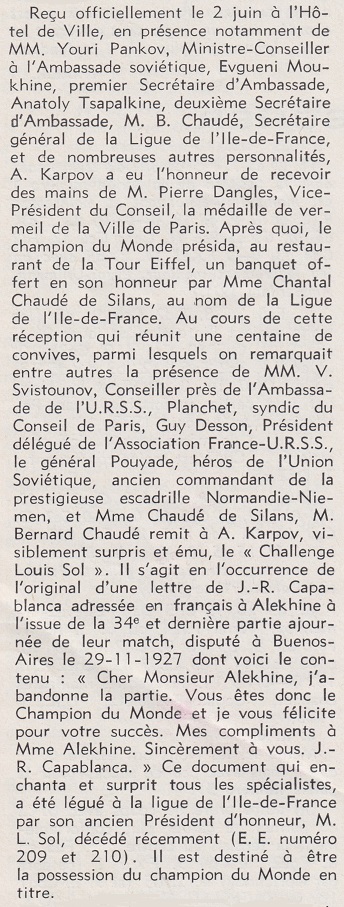

Concerning Capablanca’s letter to Alekhine dated 29 November 1927, which was shown in C.N. 10022, Thierry Lafargue (Mont de Marsan, France) draws attention to an article entitled ‘Le séjour de Karpov à Paris’ by Roland Lecomte on page 197 of Europe Echecs, July 1976. It recorded that at a reception in his honour in Paris on 2 June 1976 Karpov was presented with the original letter, which had been bequeathed to the Ligue de l’Ile-de-France by its late Honorary President, Louis Sol. The document ‘est destiné à être la possession du champion du Monde en titre’.

The relevant parts of the report:

Mr Lafargue asks where Capablanca’s letter is today.

(10050)

Lasker’s resignation of the world title in favour of Capablanca prior to their 1921 match has been discussed, inter alia, on pages 109-110 of our monograph on the Cuban and in How Capablanca Became World Champion.

See pages 47-48 of our Capablanca book for an account of the accusation by Reuben Fine about how Capablanca lost to Marshall in the 1913 Havana tournament.

Dominique Thimognier refers back to the ‘cynical’, sourceless annotation attributed to Tartakower, ‘Here Black overlooks that he has the right to resign’ (C.N.s 10171 and 10182).

Our correspondent draws a parallel with a remark given in C.N. 202 (see page 233 of Chess Explorations). That item pointed out that page 27 of the Australasian Chess Review, 30 January 1936 quoted a comment by Tartakower concerning Alekhine’s move 30...Kh8 in the 12th match-game against Euwe in 1935:

Position after 30 Rxc1

We add that a similar annotation was attributed to Tartakower on page 127 of CHESS, 14 December 1935:

Tartakower covered the world championship match for De Telegraaf, and below is his note on page 9 of the 30 October 1935 edition of the Dutch newspaper:

Although the Australasian Chess Review and CHESS both had the adjective ‘excellent’, the usual meaning of ‘geschikte’ is ‘suitable’, and a more literal translation of Tartakower’s remark ‘Hier mist zwart een geschikte gelegenheid om op te geven’ would therefore be ‘Here Black missed a suitable opportunity to resign’. That, though, is far less quotable than ‘Here Black missed excellent resigning chances’. It is difficult to judge how much humour and/or irony Tartakower’s note in Dutch was intended to convey.

(10202)

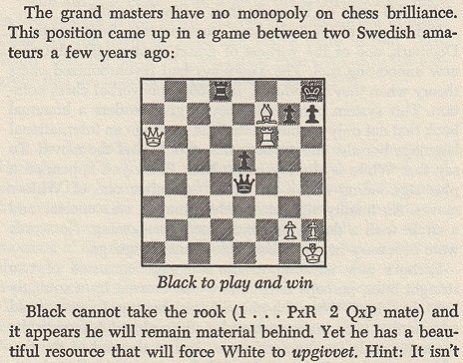

From page 127 of Chess to Enjoy by A. Soltis (New York, 1978):

Whatever details about the players and occasion are lacking, perhaps of necessity, did Soltis take the position from a reliable source? The reader is not told even that.

His comment ‘will force White to upgivvet’ is doubly wrong: the Swedish word is not upgivvet but uppgivet and, in any case, ‘will force White to ge upp’ is needed.

The same misspelling upgivvet was on page 57:

Larry Evans blindly availed himself of that material, though without mention of Soltis, in his syndicated column in, for instance, the Reno Evening Gazette, 3 March 1979, page 17. Even the idea of ‘disgust’ in connection with the German term aufgegeben was repeated:

For the full (uncorrected, of course) column, see page 45 of Evans’ book The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982).

(10233)

Frits Fritschy (Leiden, the Netherlands) comments that A. Soltis’ attempt (copied by L. Evans) to give the Dutch term relating to resignation was also faulty, since geef het op is the imperative form. Standard Dutch usage is either the past participle opgegeven or Wit geeft het op/Zwart geeft het op.

We add that elsewhere on page 57 of the Soltis book referred to in C.N. 10233 German tenses were muddled: ‘... and Spielmann got a chance to “aufgegeben”.’

(10249)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.