Edward Winter

See C.N. 9936 below.

The present general article on Richard Réti (1889-1929) complements the following:

Réti v Tartakower, Vienna, 1910;

***

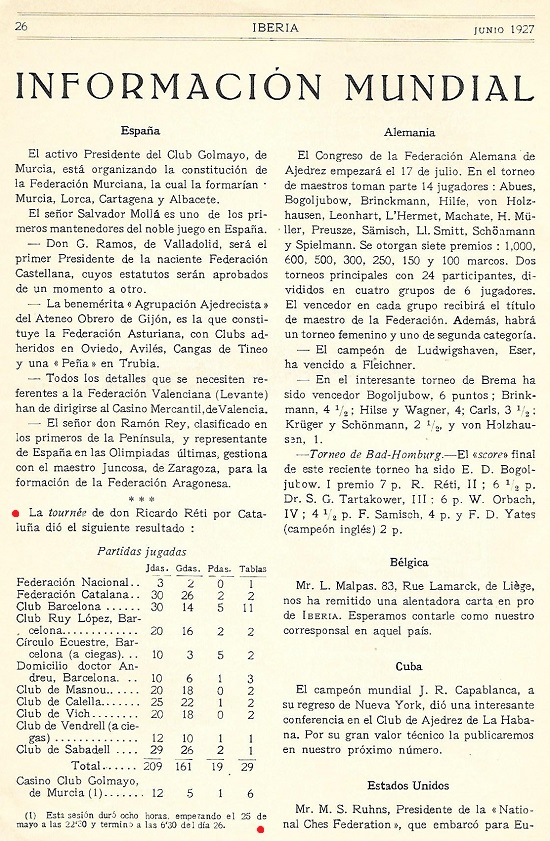

Many of our readers are, we know, avid collectors of tournament books. A new series of the greatest promise is ETC, Encyclopedia of Tournament Chess, under the direction of Warren H. Goldman. The first volume is Temesvar, 1912 which, in addition to the 105 games (the best being well annotated), contains some 30 pages of excellent introductory material (information about the tournament winner, Breyer, and a study of Hungarian chess). The book also serves as a reminder of the slow start that Réti made in serious chess competition (a very undistinguished equal 11th). His loss against Jenő Székely in the third round is an oddity in the way that one tactical circumstance dominates almost the entire game: White’s threat of a bishop move to win the unprotected black queen:

Jenő Székely – Richard Réti

Temesvar, 13 August 1912

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Bd3 Ngf6 6 Nf3 Nxe4 7 Bxe4 Nf6 8 Bd3 c5 9 O-O cxd4 10 Nxd4 Bc5 11 Be3 Qb6 12 b4 Bxd4 13 Bxd4 Qxb4 14 Rb1 Qd6 15 Re1

Source: Temesvar 1912 by Warren Goldman (Bamberg, 1981), pages 45-46.

(541)

The following extract from Capablanca on London, 1922 appeared in The Times, 29 July 1922, page 10:

‘Réti has an exceedingly well-balanced style of play; possesses a thorough knowledge of the game in all its departments, and if he had the confidence and energy of the other two he might be the strongest candidate of the four [Rubinstein, Bogoljubow, Alekhine and Réti]. He has not had, so far, the success to which I think his play entitles him. He has of late devoted considerable time to blindfold playing on a large scale – that is, he has often played 20 games or more simultaneously without sight of board or men. Such displays may excite wonder among a large number of chess enthusiasts, but as far as the performer is concerned they do him a great deal of harm in the long run. It gets him into the habit of playing a certain kind of game, not at all like what he is called upon to produce when facing opponents of the class he is bound to meet in international contests. I would not be surprised if it is his blindfold playing that has been the cause of his relative failure in the last two years.’

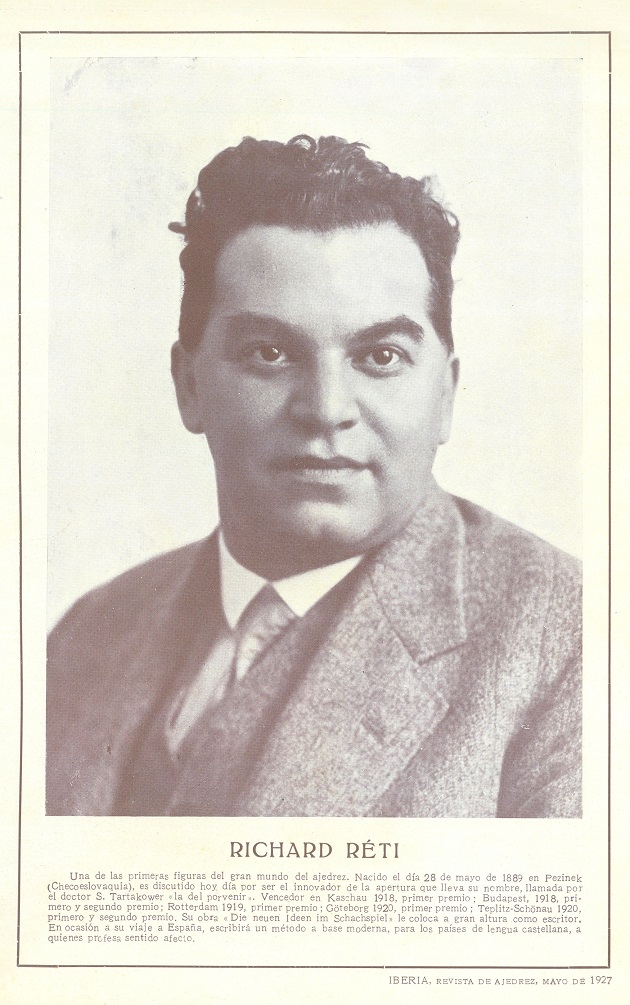

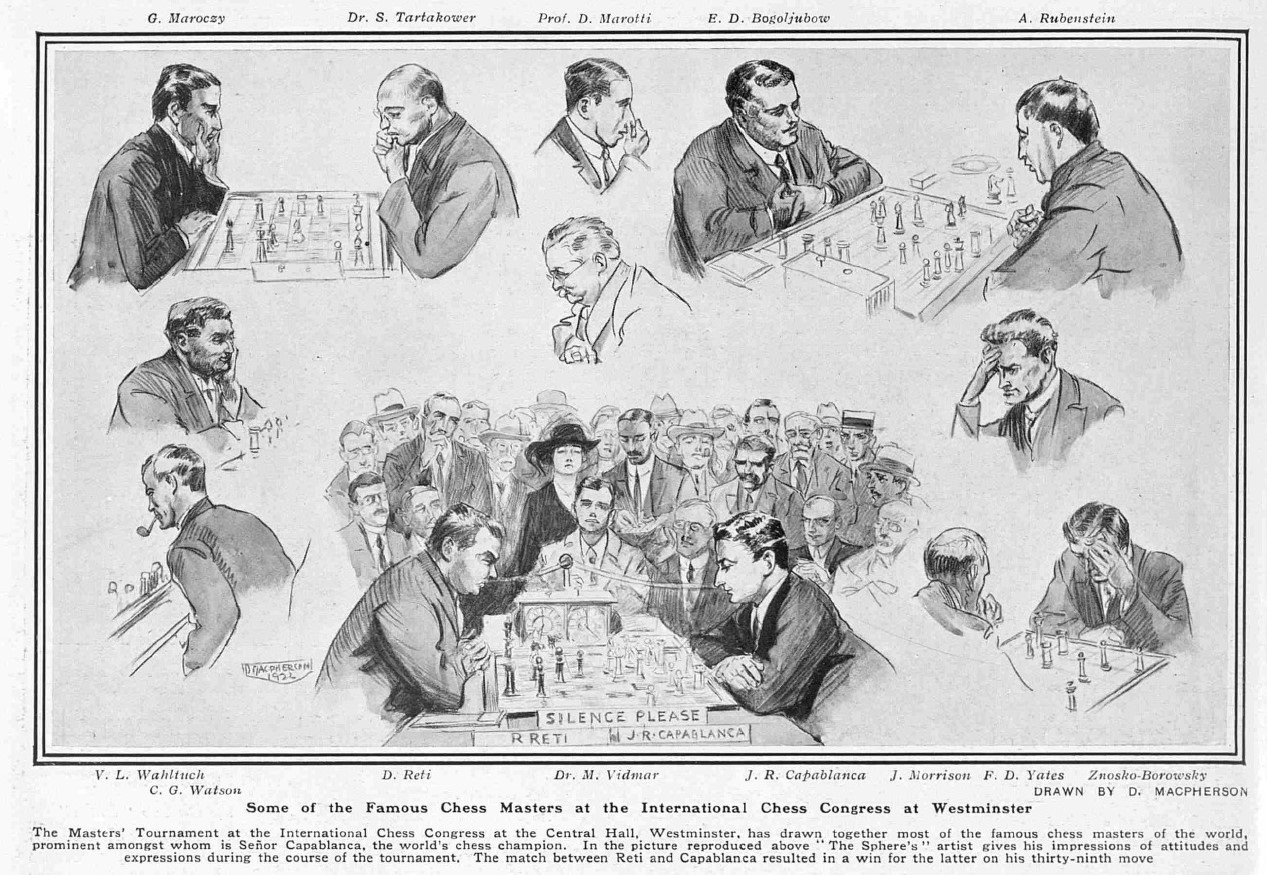

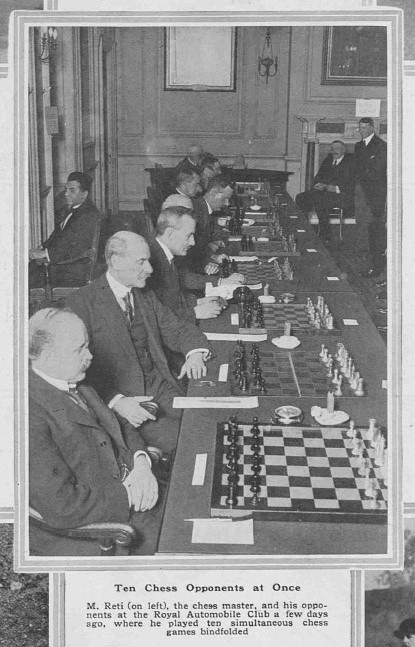

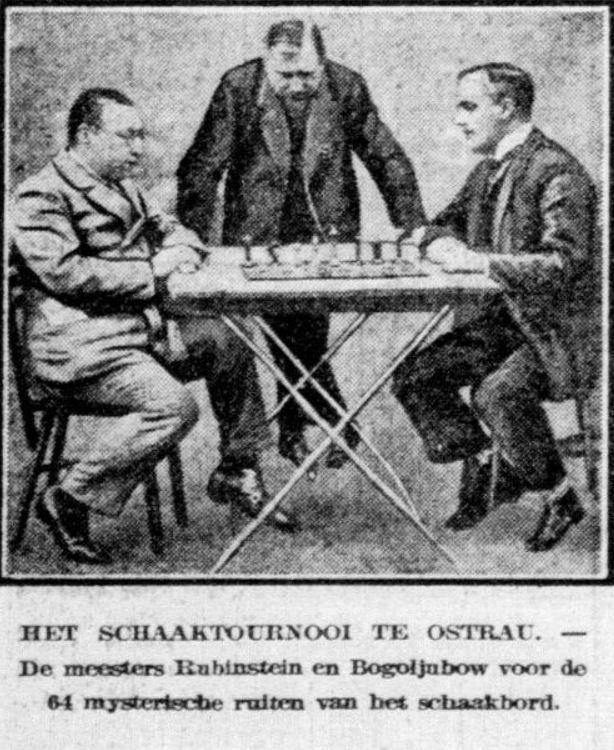

From page 186 of The Sphere, 19 August 1922:

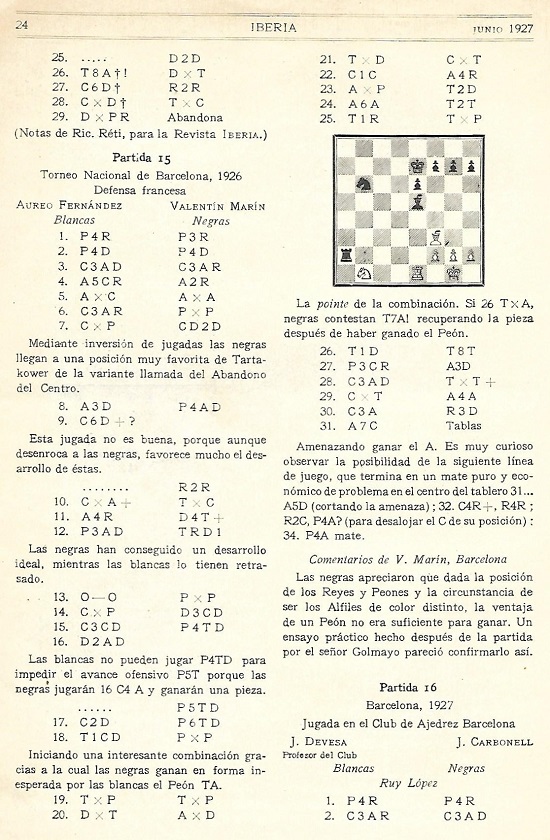

An invitation to heresy: are there any famous games that readers considered grossly over-rated? Personally – and it is hard to get more heretical than this – we have never been much taken with the Réti-Bogoljubow brilliancy-prize game at New York, 1924.

(614)

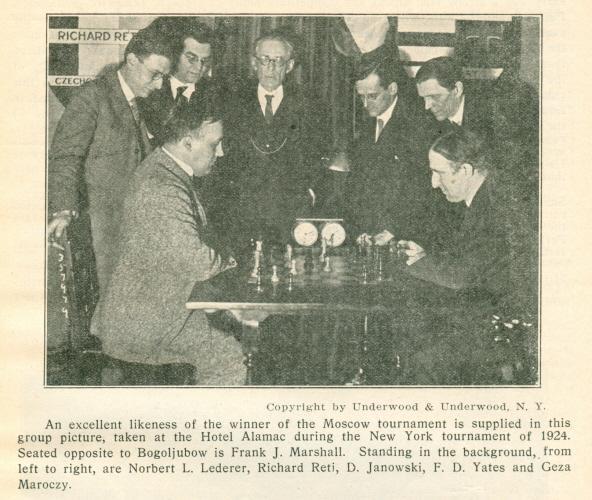

From a letter contributed by Leonard B. Meyer to Chess Review, June 1949, page 161, regarding the conclusion of the New York, 1924 tournament:

‘… local chess-players were divided into Capablanca, Marshall and Réti camps, and I was in the center as a member of the brilliancy prize committee. I was strongly in favor of giving the first prize to Réti for his game against Bogoljubow. The other judges were Hermann Helms and Norbert Lederer, and it was common knowledge that originally the committeemen did not see eye to eye. However, on the night before the dinner at which the awards were to be made, the committee finally unanimously selected this game for first prize.

The next day a bomb burst. There had been a leak, and Herbert R. Limburg, president of the congress, was in a dither. He had received a letter from John Barry, objecting to the committee’s decision. The letter also included a vitriolic attack against me. It began about as follows: “It has come to my knowledge that one Meyer, who is either a knave or a moron, has decided to give the brilliancy prize to Réti”. The balance of the letter, besides discussing patriotism, included a system for deciding prizes, with points for various types of sacrifices, all of which added up to first prize for Marshall for his game with Bogoljubow.

At a hastily called meeting of the tournament committee, the decision of the brilliancy prize committee was upheld. To further sustain the verdict, I quote the following from Dr Alekhine’s annotations to the Réti-Bogoljubow game in the tournament book: “Rightfully, this game was awarded the first brilliancy prize.”

In 1930, I met Dr Tartakower in Paris. He told me that, in his opinion, when all other details of the tournament are forgotten, the Réti-Bogoljubow game will be remembered as one of the six greatest games ever played.

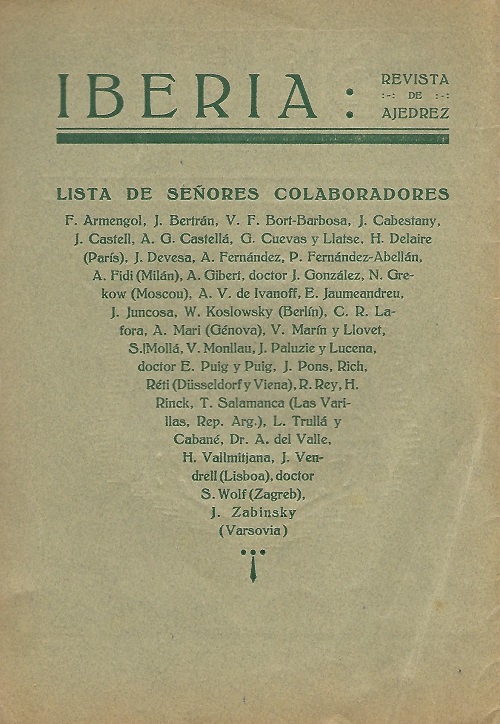

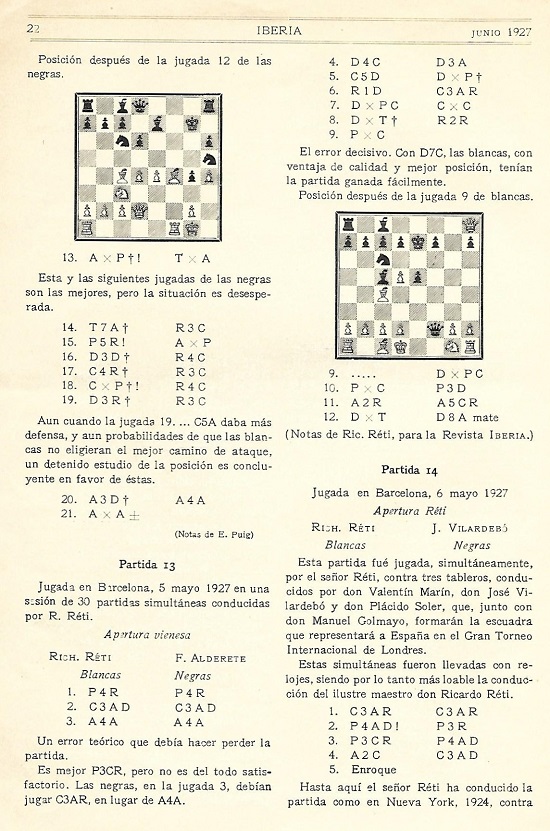

… It is like judging any other work of art: the experts are bound to disagree.

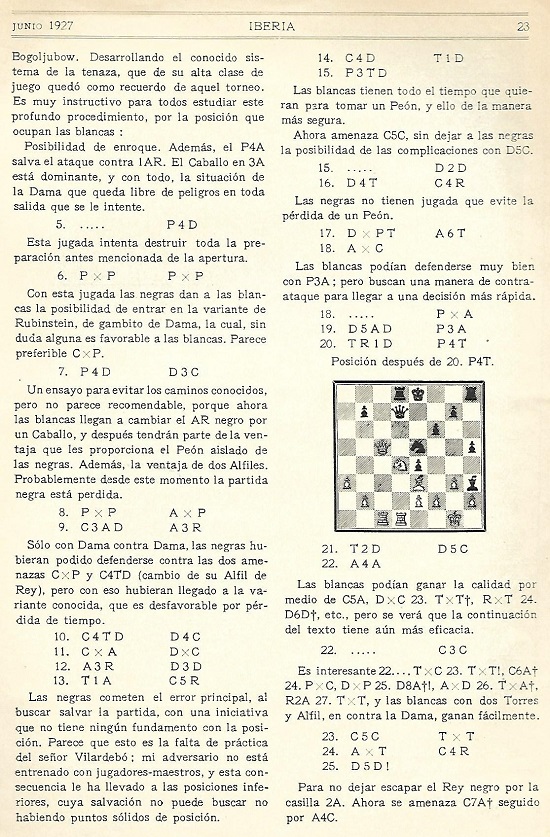

Just for the record, in later years, Barry apologized, and we buried the hatchet.’

(2538)

See too Chess in 1924.

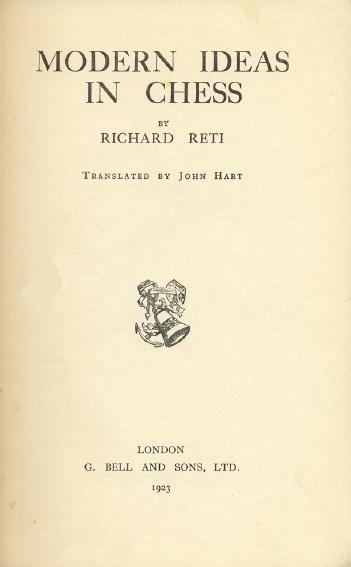

C.N. 654 quoted from a review of Modern Ideas in Chess by Richard Réti in the BCM, September 1923, page 338, written by P.W. Sergeant:

‘On page 141 Breyer is quoted as saying that after 1 P-K4 “White’s game is in its last throes”. But this is scarcely hyper-modern, for H.E. Atkins made a similar joking remark to the present reviewer if his memory is not at fault, 25 years ago.’

For a detailed discussion of this topic, see Breyer and the Last Throes, which included, from C.N. 6264, this misattribution from page 26 of Evans on Chess by Larry Evans (New York, 1974):

‘... Richard Reti, who in 1919 startled the chessworld by announcing that “White’s game is in its last throes” after 1 P-K4.’

From J.W. Harper (Harrogate, England):

‘Do you know the source of Réti’s often misquoted remark on visualization at New York, 1924? It must be often misquoted since it is given in so many different forms. After his fifth-round defeat of Capablanca, both players are said to have been interviewed by a journalist who asked them the non-player’s usual question, how many moves they saw ahead. Capablanca is quoted as claiming ten (did he really say such a silly thing?). Réti’s reply is variously given as “usually only one” or “usually not even one” or “only one, but it is always the best one”, etc. What did he say? Or is the story apocryphal?’

(837)

For the ensuing discussion of this topic, see How Many Moves Ahead?

From page 74 of The Literature of Chess by John Graham (Jefferson,1984), regarding Modern Ideas in Chess:

‘The word “modern” refers to 1942 when Réti first recorded these ideas.’

Réti died in 1929.

(889)

Alekhine and Réti had opposite views on the worth of Capablanca’s sixth move in his game (as White) against Yates at New York, 1924 (1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bf4 Bg7 5 e3 O-O 6 h3). Alekhine, in the tournament book, said it was ‘not exactly necessary ... after the text-move, Black obtains some counter-play, the defense of which will demand all of the world champion’s care’. Réti, however, calls 6 h3 ‘a move of genius’ (Homenaje a Capablanca, pages 185-186) For him it was ‘the most profound move of the entire game’. He explains its idea as follows (our résumé): if Black is to make the most of the king’s bishop he will need to play, eventually, either ...e5 or ...c5. Capablanca’s plan is to prevent the former, so as to force the latter. This will transfer the battle to the queen’s side, where White will have every chance of securing an advantage, owing to the absence on that flank of Black’s dark-squared bishop. Capablanca, in view of the position of his own bishop in the centre of the board, prevents the centre from becoming the battlefield by 6 h3. He does not allow Black to play 6...Bg4, followed by ...Nbd7 and ...e5.

(916)

The May-June 1912 Wiener Schachzeitung (pages 175-176) reports on a simultaneous exhibition given by Capablanca in Vienna on 21 October 1911, his score being +22 –5 =8. One of the eight draws was secured by Réti. It would be marvellous to find the score of the Capa-Réti game, though the chances must be virtually nil.

(1211)

As reported on page 45 of our monograph on Capablanca, he wrote in the Diario de la Marina, 4 May 1913:

‘I became acquainted with Réti in Vienna in November [sic] 1911 when he was a university student. He is a young man of about 22 years of age, dark, thin and of frail appearance.’

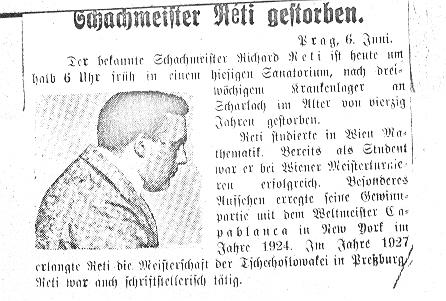

C.N. 1268 pointed out the extreme brevity of the BCM’s obituary of Réti (July 1929 issue, page 258): seven lines.

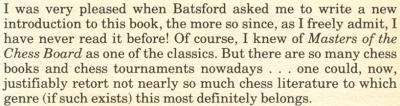

In any discussion of linguistic barbarism the name of Jon Speelman rarely remains in the background. Batsford have just issued a reprint of Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board (which, a silly blurb pretends, is ‘the only collection of the best games of all the world’s leading pre-war players from Anderssen to Alekhine’). Speelman provides a Foreword, from which we quote the first paragraph in full:

‘I was very pleased when Batsford asked me to write a new introduction to this book, the more so since, as I freely admit, I have never read it before! Of course, I knew of Masters of the Chess Board as one of the classics. But there are so many chess books and chess tournaments nowadays ... one could, now, justifiably retort not nearly so much chess literature to which genre (if such exists) this most definitely belongs.’

In Réti’s day such gibberish as that last sentence would have been unmercifully expunged by a member of the editorial staff.

(1441)

Chess and the English Language.

It is frequently stated that Rudolf Spielmann was very mild-mannered, in stark contrast to his fiery attacking style over the board. On page 199 of the September 1981 CHESS Euwe described him as follows: ‘Very pleasant, though a little inclined to complain about things. He has often stayed with me. He was rather a dreamer ...’

One novel complaint made by Spielmann (according to page 18 of P. Michel’s Lachaga book on Dortmund, 1928) arose from his loss to Bogoljubow in the third round of that tournament. The trouble was that in round four Bogoljubow proceeded to lose recklessly to Dr Alfred van Nüss. Spielmann was not slow to see a malevolent pattern:

‘I am bound to believe that it is only against me that opponents display their full strength.’

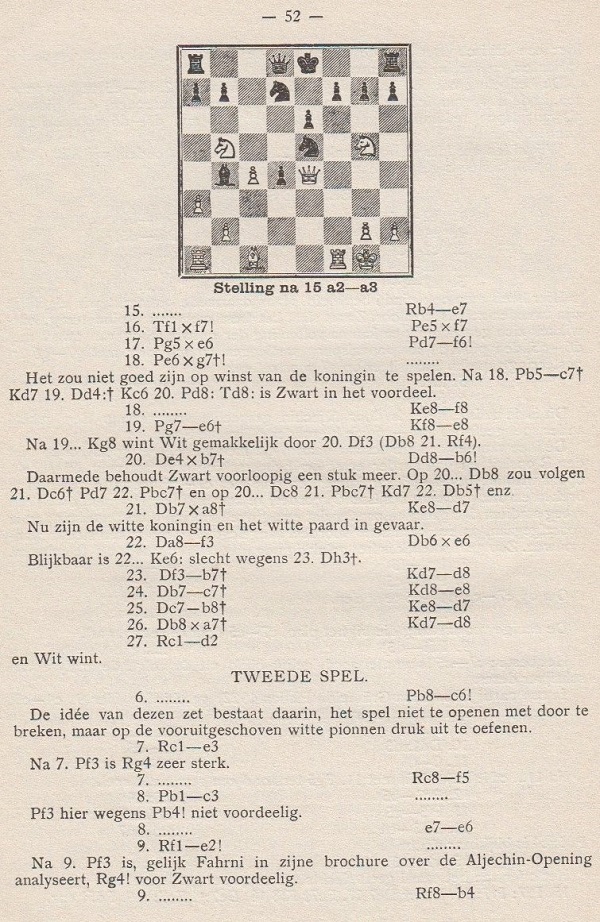

In round two Spielmann had only himself to blame:

Rudolf Spielmann – Richard Réti

Dortmund, 28 July 1928

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Nc6 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Ne2 d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Bxd5 Qxd5 8 O-O Qa5 9 a3 O-O 10 Be3 Bxc3 11 Nxc3 Nd4 12 b4 Qa6 13 f4 Qc6 14 Qd2 Qxc3 15 White resigns.

Master chess contains few moves to compare with White’s 14th.

(1539)

The earlier French version of Euwe’s remarks about Spielmann quoted above:

‘Très gentil et un peu enclin à se plaindre. Il a souvent logé chez nous. Il avait un air un peu bizarre; enfant, il était tombé sur la tête ...’

Source: Europe Echecs, August 1981, page 372 (interview translated from the Dutch by J. Marguillier). The original Dutch version was published in the May 1981 issue of Schakend Nederland.

At the Central Café in Vienna on 2 December 1914, Richard Réti won a miniature against Dunkelblum (‘of Cracow’):

Richard Réti – Dunkelblum

Vienna, 1914

Three Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Bc5 4 Nxe5 Nxe5 5 d4 Bxd4 6 Qxd4 Qf6 7 Nb5 Kd8 8 Qc5 Resigns.

The game was published on page 153 of the July-August 1915 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung and has become an anthology piece. White’s seventh and eighth moves were awarded two and three exclamation marks respectively, and the conclusion is certainly a neat example of the double threat (to c7 and f8). Yet remarkably, the identical moves had been played before, and although the earlier game had been won by none other than Capablanca, it was promptly forgotten. The occasion was a simultaneous display in Washington on 6 January 1909. Missing the main threat, the young Cuban’s opponent, E.B. Adams, played 8...Nc6, which was naturally answered by 9 Qf8 mate.

(Inside Chess, 1992)

See Capablanca Goes Algebraic.

‘Réti had an extraordinary gift for using his knights to create weaknesses in open positions’, wrote Roberto Grau in La Nación of 26 October 1930. By way of example, he printed the following forgotten game, in which over half of White’s moves are made by the knights:

Richard Réti – Luis Belgrano Rawson

Buenos Aires, 6 September 1924

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nf6 5 Ng3 e5 6 Nf3 exd4 7 Qxd4 Qxd4 8 Nxd4 Bc5 9 Be3 Nd5 10 Ne4 Nxe3 11 Nxc5 Nxf1 12 Rxf1 b6 13 Ne4 O-O 14 O-O-O c5 15 Nb5 Na6 16 Ned6 Be6 17 f4 g6 18 h3 h5 19 Rf2 Kg7 20 f5 gxf5 21 Nxf5+ Kg6 22 Nbd6 Rad8 23 Ne7+ Kg7 24 g4 hxg4 25 hxg4 Nc7 26 Rfd2 Kf6 27 Nc6 Ra8 28 Rf1+ Kg7 29 Nf5+ Kg6 30 Ne5+ Kg5 31 Nd6 f6 32 Ne4+ Kh6 33 Nxf6 Kg7 34 g5 Nd5 35 Rh2 Rh8 36 Nh5+ Kg8 37 Rfh1 Resigns.

The annotations by Grau call 8...Bc5 a slight error and criticize 9...Nd5 as a routine move. White’s 10 Ne4 is described as ‘a formidable manoeuvre to eliminate the bishop, which is watching over d6’. However, a different view on this line was expressed by Alekhine in his book on New York, 1927. In the 14th round, Alekhine v Capablanca had the same opening. To the Cuban’s 8...Bc5, Alekhine replied 9 Ndf5 and wrote, ‘Naturally not 9 Be3 immediately, because of 9...Ng4 or 9...Nd5, etc.’

Grau did not specify the venue or date of the Réti game. We imagine that it was one of his two wins against the tail-ender in the 1924 Argentine Championship, a tournament which Réti won, playing hors concours. Page 213 of the December 1924 American Chess Bulletin gave the final standings, but no games.

(1962)

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) confirms our suggestion that the Réti v Belgrano Rawson game occurred in the Buenos Aires tournament of 1924. It was played in round three, on 6 September 1924. The score was published on pages 424-426 of El Ajedrez Argentino, 1926.

Mr Kalendovský is the author of Richard Réti – šachový myslitel.

(2007)

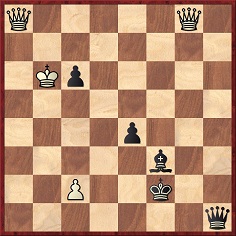

An endgame featuring two queens against one is Réti v Rubinstein, Marienbad, 1925. Queens were exchanged at move 16, but three promotions on moves 52-54 led to this position:

Play continued: 54...e3 55 Qa4 e2 56 Qd4+ Kf1 57 Qd3 Kf2 58 Qd2 Qb1+ 59 Kc7 c5 60 Qb3 Qxb3 61 cxb3 Kf1 62 Qd3 Kf2 63 Qc2 Kf1 64 Qc4 Kf2 65 Qxc5+ Kf1 66 Qc4 Kf2 67 Qd4+ Kf1 68 Qd3 Kf2 69 Qd2 Kf1 70 Qd3 Kf2 71 Qd4+ Kf1 72 Qc4 Kf2 73 Qc5+ Kf1 74 Qc4 Kf2 75 Qd4+ Kf1 76 Qd3 Kf2 77 Qd2 Kf1 78 Qe3 Bg2 Drawn.

(2025)

For other games with the same motif, see Chess Jottings.

John Donaldson (Seattle, WA, USA) sends an English translation by R. Tekel and M. Shibut of an interesting article by Réti ‘Do “New Ideas” Stand Up in Practice?’, published on pages 8-10 of the Virginia Chess Newsletter of September/October 1993.

A sidelight is Réti’s nomination for White’s best first move: 1 c4. His reasoning begins: ‘One would expect Black’s strongest point in the centre to be d5 since, unlike e5, it has natural protection by the queen. Therefore, the ideal initial move is 1 c4, immediately taking aim at d5.’

Tartakower (see page 15 of his first volume of Best Games) called 1 c4 ‘the strongest initial move in the world’.

(2030)

We first mentioned that remark of Tartakower’s in C.N. 1219. See also The English Opening.

On page 151 of Instructions to Young Chess-players by H. Golombek (London, 1958) Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess was described as ‘the best book ever written on chess’.

(2165)

In L’Eclaireur du soir (Nice) of 25 June 1929 Georges Renaud recalled some remarks by the recently deceased Richard Réti:

‘I see no reason why I should not be world champion one day. If an extraordinary Wunderknabe is not being bottle-fed somewhere at the moment, I shall be world champion at 50. That is because I do not have genius. Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine have genius. They cannot progress. I do not even have talent, I owe everything to my work, and I am making progress every day. One day I shall overtake them. And if the Wunderknabe does not arrive beforehand, I shall be champion of the world.’

Renaud reported that Réti’s smile and sparkling eyes indicated that he only half believed his claim.

Elsewhere in the article Renaud stated that after playing 24 games blindfold in Haarlem on 6 August 1919, Réti conducted a private experiment against Euwe and Oskam, each of whom took 18 boards against him. Réti managed to play blindfold the first eight moves of all 36 games, but then decided to venture no further with the trial.

(2303)

From page 131 of The Sphere, 10 February 1923:

Tartakower related an incident which occurred at Carlsbad, 1923:

‘… Teichmann, who did not like to overdo it, had accepted the draw offered by Réti when the tournament director, Mr Tietz, who considered that Teichmann had the better position and who “had his interests at heart”, refused to accept the decision and ordered the battle to continue. Teichmann then went for outright simplification … and soon sank. Was such a result not unfair?’

Source: Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 24, pages 244-245.

(2465)

B. de Oliveira and M. Kiss – R. Réti and L. Vianna

Rio de Janeiro, 10 February 1925

Alekhine’s Defence

1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Nd5 3 c4 Nb6 4 b3 d6 5 Bb2 dxe5 6 Bxe5 Nc6 7 Bb2 Bf5 8 d4 e6 9 Be2 Bb4+ 10 Kf1 Qd7 11 c5 Nd5 12 a3 Bxb1 13 axb4 Bg6 14 b5 Ncb4 15 Qd2 O-O 16 Nf3 Qe7 17 h4 Qf6 18 h5 Be4 19 Ng5 Bxg2+ 20 Kxg2 Nf4+ 21 Kf1 Qxg5 22 Rg1 Qf5 23 d5 Qh3+ 24 Ke1 Nbd3+ 25 Bxd3 Nxd3+

26 Qxd3 Resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, March 1925, page 60.

The Bulletin quoted Aubrey Stuart’s eye-witness report in the Brazilian American:

‘Réti is a swarthy black-haired man in the prime of life. His spacious occiput and neck show nerve control and a plentiful supply of blood to the brain. Round shoulders and long straddling legs detract from his appearance when he rises, but seated at play he is an interesting figure.’

(2487)

See The Chess Seesaw.

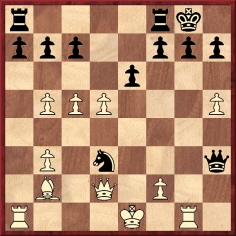

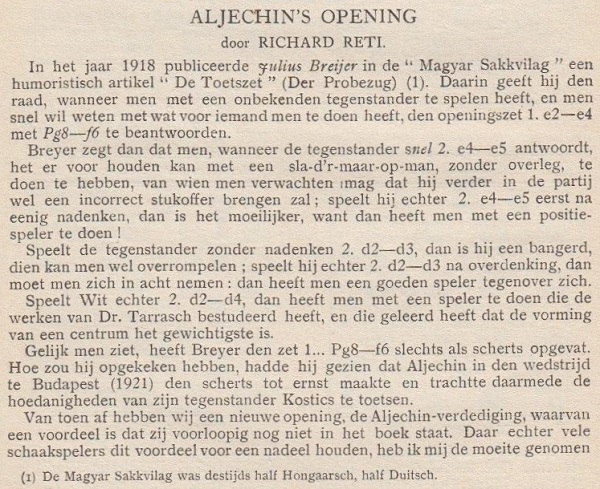

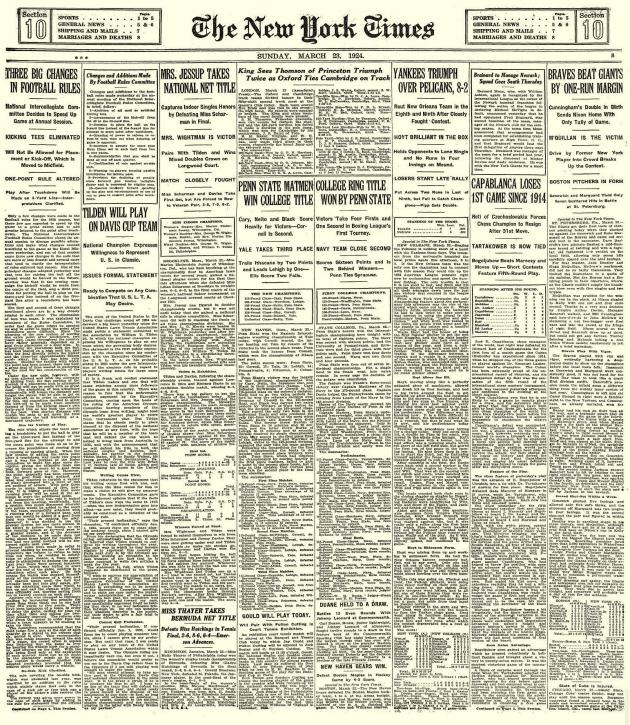

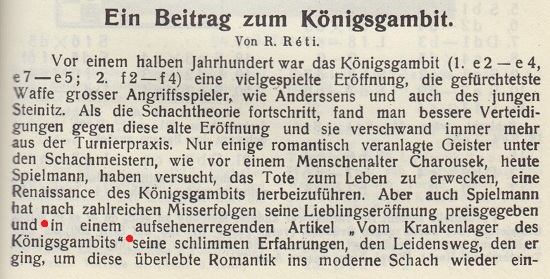

An article on Alekhine’s Defence by Richard Réti on pages 50-54 of the February 1923 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

Spielmann on Réti:

‘The late master was one of my most dangerous opponents, and I must honestly admit that he surpassed me in terms of richness of ideas in the opening. In almost every game he played against me he invented something new. Yet perhaps his strength lay not so much in the discovery of a new move or a hitherto unknown tactical finesse as in a new strategy. Very frequently, and within just a few moves, I would find myself in a lost position against him without knowing exactly how it had happened.’

Spielmann annotated ‘one of the best games Réti played against me’, from the Vienna, 1923 tournament (although he gave the date as 1920, the opening move-order as 1 Nf3 e6 2 c4 d5 and the conclusion as ‘28 a3 and White won quickly’). His notes concluded, ‘an excellent game, typical of Réti’s style’.

Source: L’Echiquier, August 1929, pages 338-339.

The full score is given below:

Richard Réti – Rudolf Spielmann

Vienna, November 1923

Réti’s Opening

1 Nf3 d5 2 c4 e6 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 c5 5 cxd5 exd5 6 d4 Nc6 7 O-O cxd4 8 Nxd4 Bc5 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 Qc2 Qb6 11 Nc3 Bd4 12 Na4 Qb5 13 Rd1 Be5 14 Be3 O-O 15 Rac1 Ba6

16 Nc5 Rab8 17 Nd3 Nd7 18 Bxa7 Rb7 19 Nxe5 Nxe5 20 Bd4 f6 21 Bxe5 fxe5 22 Qxc6 Qxe2 23 Bxd5+ Kh8 24 Bf3 Qb5 25 Qxb5 Rxb5 26 Be2 Ra5 27 Bxa6 Rxa6 28 a3 h6 29 Rd7 Raf6 30 Rc2 Rf3 31 Re7 R8f5 32 Re2 Rb3 33 R7xe5 Rxe5 34 Rxe5 Rxb2 35 a4 Ra2 36 a5 Kh7 37 h4 Kg6 38 h5+ Kf6 39 Rb5 Ra4 40 Kg2 Ke6 41 Rb6+ Kf7 42 a6 Ra5 43 Rb7+ Kf6 44 a7 Ra4 45 f4 Ra3 46 Kf2 g6 47 Rb6+ Kf5 48 Rxg6 Rxa7 49 Rxh6 Ra2+ 50 Kf3 Ra3+ 51 Kg2 Kg4 52 Rg6+ Kxh5 53 Rg5+ Kh6 54 Kh3 Rb3 55 Ra5 Kg6 56 Kg4 Rc3 57 Ra6+ Kg7 58 Kh4 Resigns.

(2488)

From Missed Mates (an article of ours originally published by ChessBase):

In C.N. 2117 Richard Forster (Zurich) referred to the position which arose after White’s 25th move in Réti v Marshall, New York, 1924 (see pages 165-166 of the English-language tournament book, published in 1925):

Play went 25...Nxg3 26 Rhg1, and Alekhine wrote: ‘Or 26 hxg3 Qxg3+ 27 Ke2 Qg2+ 28 Kd3 Rxh1 29 Rxh1 Qxf3+, to be followed by 30...Qxh1, with an easy win.’ Instead, there is 28...Qc2 mate.

Analysis by Alekhine (position after 28 Kd3)

On page 33 of his 1929 book Schachmethodik Tartakower also ignored the mate, as did Soltis on page 270 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion (Jefferson, 1994).

C.N. 2131 remarked that in the original 1925 edition of Alekhine’s tournament book W.H. Watts gave a nine-page errata supplement which mentioned (on page vi) 28...Qc2 mate, and when discussing the matter further on pages 283-284 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves we drew attention to some complications. Here is the complete game-score as it appeared in the tournament book (English and German editions):

Richard Réti – Frank James Marshall

New York, 6 April 1924

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 d5 3 cxd5 Nxd5 4 d4 Bf5 5 Nc3 e6 6 Qb3 Nc6 7 e4 Nxc3 8 exf5 Nd5 9 Bb5 Bb4+ 10 Bd2 Bxd2+ 11 Nxd2 exf5 12 Bxc6+ bxc6 13 O-O O-O 14 Qa4 Rb8 15 Nb3 Rb6 16 Qxa7 Qg5 17 Qa5 c5

18 Qxc5 Nf4 19 g3 Rh6 20 Qxc7 Ne2+ 21 Kg2 Qg4 22 Rh1 f4 23 f3 Qh3+ 24 Kf2 Rc8 25 Qa5 Nxg3 26 Rhg1 Qxh2+ 27 Rg2 Qh4 28 Rc1 Re8 29 Qb5 Ne4+ 30 Kf1 Qh1+ 31 White resigns.

However, we observed, when Réti annotated the game on pages 259-260 of the September 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung he gave White’s 18th move as 18 dxc5. If that were correct, Alekhine would have missed no mate later in the game. Hanon Russell (Milford, CT, USA), who possessed the original score-sheets of both Réti and Marshall, informed us that they respectively gave White’s 18th move as ‘Dxc5’ and ‘QxP’. A later transcription error in the German notation would have been easily made (i.e. ‘Dxc5’ becoming ‘dxc5’).

On page 126 of Das New Yorker Schachturnier 1927 (Berlin, 1928) Alekhine wrote regarding the communication of game-scores by telegraph:

‘But in general more accurate wire information for the foreign press should be provided during American tournaments. In 1924, for example, a similar error resulted in a wholly incorrect judgment of Marshall’s win against Réti.’

Here, a further point in this complex affair may be added. In 1924 Alekhine also annotated the game in Le Pion (Montreal); see pages 116-117 of the May 1924 issue of La Stratégie. He gave White’s 18th move as Qxc5, and at move 26 merely wrote, ‘If 26 hxg3 Qxg3+ 27 Ke2 Qg2+, winning easily’.

From a letter (written in Moscow on 23 April 1936) which Emanuel Lasker had published on pages 357-358 of the 14 May 1936 issue of CHESS:

‘Réti’s alleged remark that my conception of chess as a fight is fully in accordance with my philosophy to fight against my opponent not only intellectually but “with the whole of my personality” is astounding. I often wrote of the theory of contests – in Common Sense in Chess, 1896, in Struggle, 1906, in Das Begreifen der Welt, 1913, in Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar, 1918, in Lasker’s Chess Manual, also in my Chess Primer. Moreover, my philosophical books were painstakingly discussed, over a period of five years, by the pupils of a professor of philosophy at the University of Giessen, but I do not think anybody has found in my writings anything bearing out the above remark, even remotely. My writings deal only with the laws and principles governing the struggle between perfect strategians. These do not exist in the flesh, because no-one, in any respect whatever, is perfect. Perfect strategians are instincts personified and idealized, for instance the perfect strategian at chess is the perfect chess instinct (usually called judgement). My books do not deal with mistakes or human foibles. Only my latest manuscript goes further than that, in that it deals with the erring and blundering creature, his psychology, his ethos and his drama. But it was never known to Réti. In fact, only a few persons know it, because, as the world at present runs, it has, as yet, not found its publisher.

But did Réti make the above remark in sober earnest? I think not. I have examined what he said of my style in his Lehrbuch (1930) page 123 e.g. and in the sentences cited by Fred Reinfeld and Reuben Fine in their Dr Lasker’s Chess Career page 12. In the former book Réti explains my style in that I strive to take advantage of the shortcomings of my opponent (but everybody does that) and in the latter by “my boundless faith in common sense”, which is much more to the point. Probably, after mature deliberation, Réti preferred to express his real views as in these two places, and the remark you quote was uttered as a mere casual and only half-serious conjecture.

The worst of his remark is that it is very vague. What does “the whole of one’s personality” circumscribe? Did other masters fail to fight “with their whole personality”? Without further explanation Réti’s alleged remark, I fear, has many widely different meanings. Under the cloak of such vagueness a debater is at liberty to support any theory whatsoever, for instance, that of Kmoch (“infallible judgment”, “elasticity of outlook”) or Spielmann’s (“the ideal fighter”) or Dr Tartakower’s (“unswerving belief in the elasticity of the position”; I became “the father of ultra-modern chess”) or Dr Tarrasch’s (in his Die moderne Schachpartie, 1916, page 193, he said, one is tempted to believe that I use witchcraft, hypnotism or such in order to induce my opponent to commit mistakes) or that of Maróczy (I smoke execrable cigars during play which cause my opponent to deteriorate for the time being, New York Times, 1928).

A collection of judgements on my style would be quite interesting and instructive. As the years passed I came across many of them. He who judges another, judges himself. However, I cannot go into this question at present. But I have repeatedly explained my conception of a contest between masters, i.e. between creative minds representative of their period. The fight between them is the necessary and sufficient condition of their creative work. To have a worthy opponent is a boon. He is short-sighted who strives for indisputable supremacy in his domain, whether at chess or other creative work. If, by ill-chance, he succeeds in approaching his stupid goal, he is blinded to his defects and deteriorates. When the outcome of tournaments is most uncertain and incalculable, as at present, then is chess passing through its most fertile periods.’

(2516)

See also Chess and Hypnosis and Chess and Tobacco.

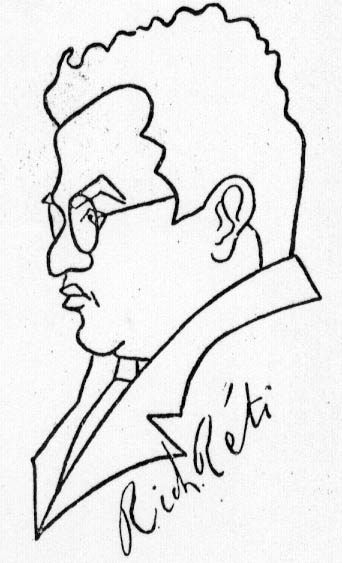

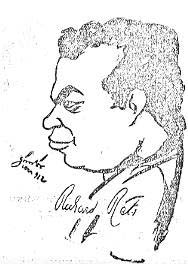

From our collection: a baker’s dozen of sketches and caricatures of Richard Réti:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

(3110)

Now we have found three more:

(4125)

From Miriam Friedman Morris (Pomona, NY, USA):

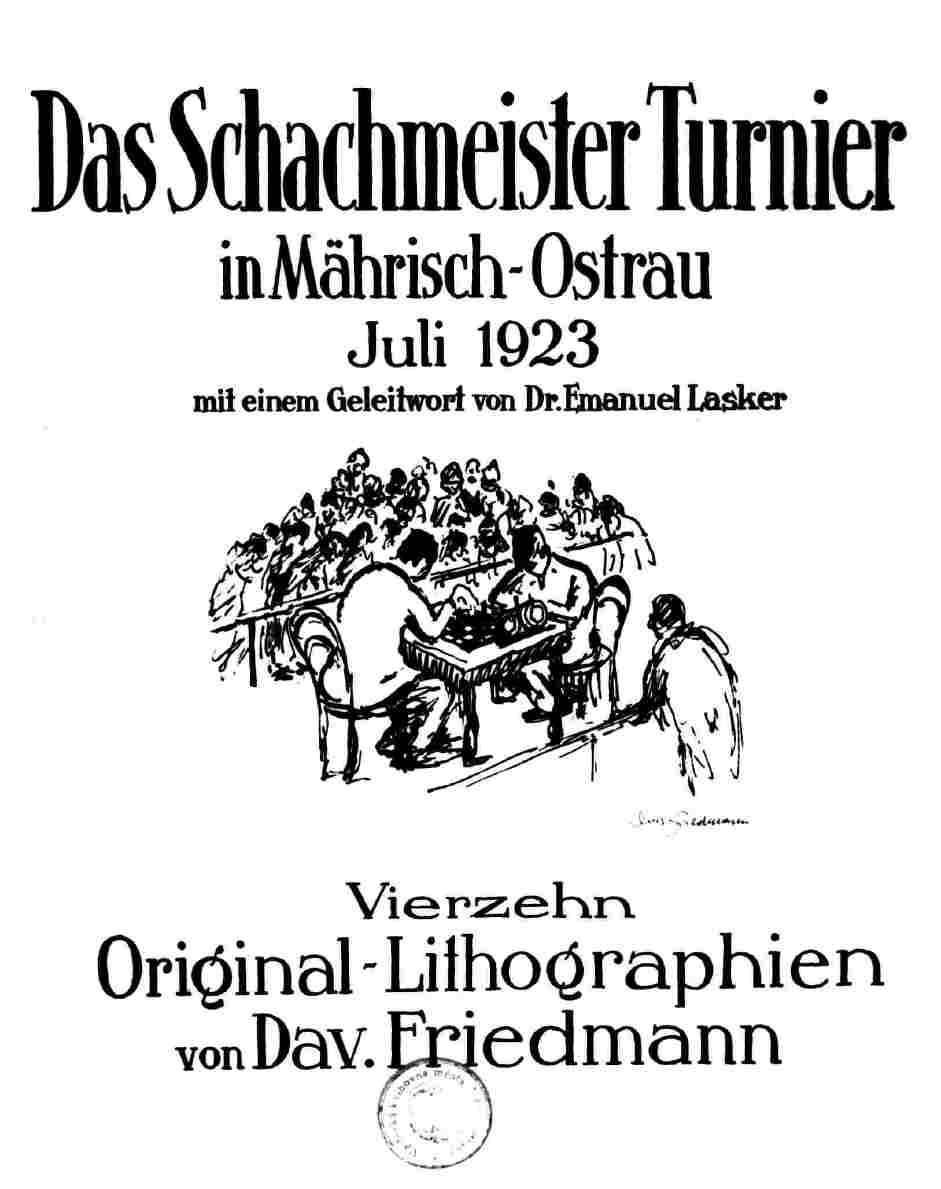

‘C.N. 3510 includes three portraits of Réti (1, 9 and 11) produced by my father, David Friedmann (1893-1980).

Richard Réti (Copyright: Miriam Friedman Morris)

He is renowned for a series of lithographs entitled “Das Schachmeister Turnier in Mährisch-Ostrau, Juli 1923” (The Chess Master Tourney) and “Köpfe berühmter Schachmeister” (Portraits of Famous Chess Masters). Four portfolios of “Köpfe berühmter Schachmeister” were found. One of them, No. 28, is in the collection of the Royal Library of the Netherlands, The Hague.

The portfolio of the Mährisch-Ostrau tourney comprises 14 lithographs, one portrait representing each participant: Lasker, Réti, Grünfeld, Selesniev, Euwe, Tartakower, Bogoljubow, Tarrasch, Spielmann, Rubinstein, Pokorný, Hromádka, Wolf and Walter.

The portfolio “Köpfe berühmter Schachmeister” consists of 12 or 14 portraits. Two chessplayers were dropped, whereas Ossip Bernstein and/or Richard Teichmann were added. It is possible that as many as 50 portfolios were produced. All the lithographs bear the signature of the chessplayer depicted, and the signature Dav. Friedmann was handwritten in pencil on each lithograph.’

(4132)

For further information, see Chess Cartoons and Caricatures and Chess Cartoons by Tom Webster.

Giordano Bergamo (Cavareno, Italy) writes:

‘I have noticed that in Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board Tartakower is the only grandmaster criticized personally. Had there been enmity between Réti and Tartakower?’

What criticism the book contains seems quite covert. The best-known account of bad blood between the two masters is probably Golombek’s on pages 67-68 of Chess Treasury of the Air edited by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966). Golombek quoted Tartakower as telling him, ‘Réti was a dreadful liar’.

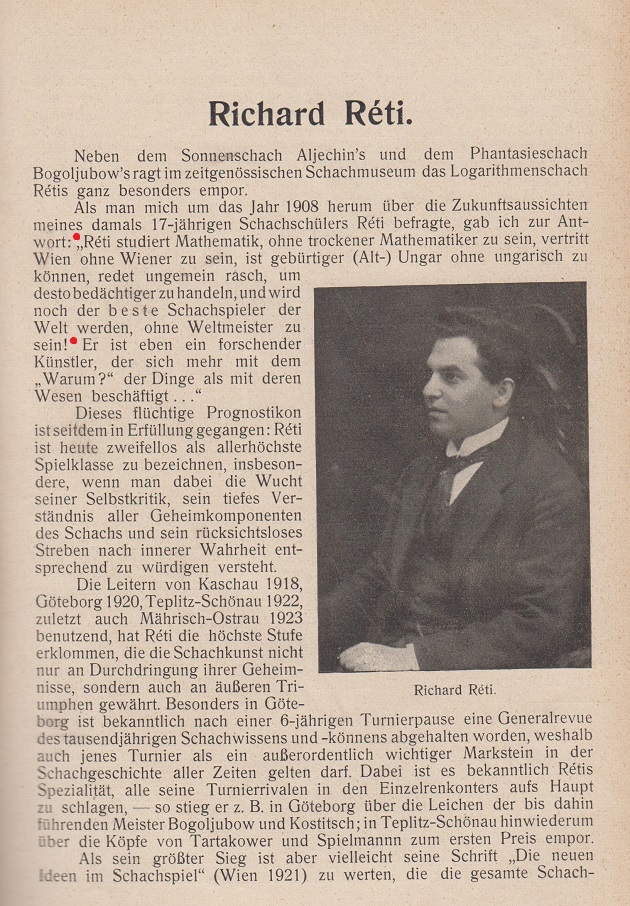

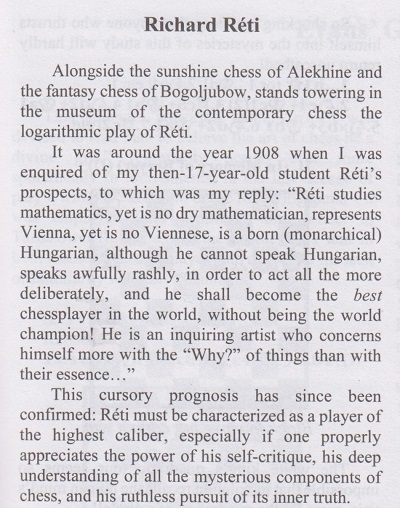

When Réti died, Tartakower published an article about him on pages 212-214 of the July 1929 Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, but it focussed on Réti’s hypermodern opening play. Did the two masters write about each other elsewhere in more personal terms?

(3176)

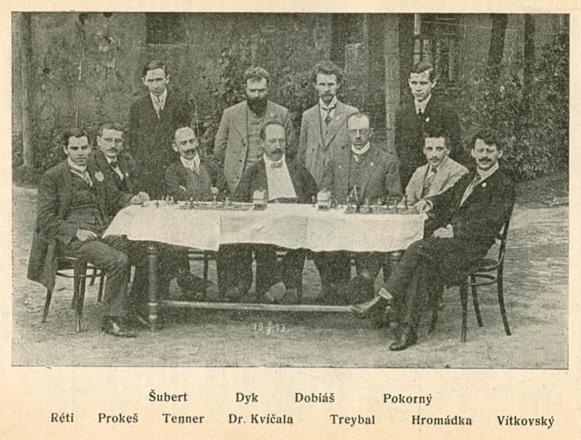

A group photograph from London, 1927:

Seated from left to right: F.J.

Marshall, W. Winter, E. Bogoljubow, A. Nimzowitsch, W.A.

Fairhurst, S. Tartakower.

Standing: W.H. Watts, M.E. Goldstein, H. Kmoch, M. Vidmar, R.C.

Griffith, Sir George Thomas, E. Busvine, F.D. Yates, J. Schumer,

E. Colle, V. Buerger, R. Réti

(3959)

When Réti died a Vienna newspaper, Der Abend of 6 June 1929, mixed him up with Bogoljubow:

(4124)

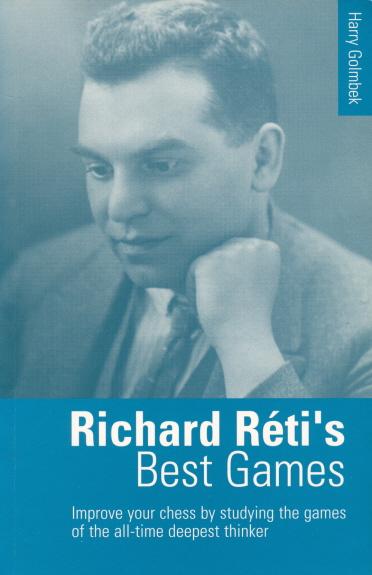

From a review by J.M. Aitken of Réti’s Best Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1954) on pages 100-101 of the March 1955 BCM:

‘Chess books (and, in particular perhaps, games collections) can be divided into two main classes – those that are the product of a genuine devotion of the author to the subject and those that are, in the main, made to order to meet a real or supposed topical demand. It is not intended to scorn or disparage unduly the second class; given a competent and conscientious author, an excellent book will probably be produced. Nonetheless, it is in the first category that the true masterpieces are likely to be found and it is high in this class that we must rate Golombek’s book on Réti. Réti has clearly always been one of Golombek’s chess heroes and now, like a more fortunate Antony, he comes not to bury Réti, but to praise him.’

Below is Golombek’s inscription in one of our copies of his book:

(4206)

From page 12 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1942):

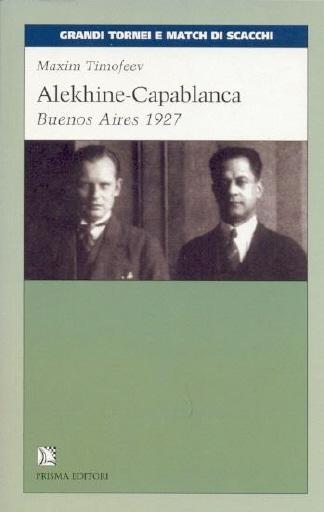

‘Before the 1927 match for the title took place, not a single commentator considered the possibility that Capablanca could lose the match. Some speculated that Alekhine might win a game or two, but that was the limit of their expectations.’

In the ‘Victory and Disaster’ chapter on page 115 of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947) Harry Golombek wrote:

‘To the astonishment of practically the whole of the chess-playing world (Réti was the only far-sighted exception), Alekhine challenged and defeated him in a match for the world championship at Buenos Aires that very same year.’

So what exactly was predicted and by whom?

Pages 51-62 of Alekhine-Capablanca Buenos Aires 1927 by Maxim Timofeev (Rome, 2004) has a chapter entitled ‘I pronostici della vigilia’ which focuses on pre-match suggestions that Capablanca was, at least, not certain to win. It presents Italian translations of three articles:

To avoid possible imprecision from using the Italian translations as intermediaries, we wonder whether a reader with access to the above Russian material could kindly send us an English version of the paragraphs containing the predictions.

Timofeev’s book also contains (pages 151-207) a digest of post-match observations by Alekhine, Capablanca, Lasker, Romanovsky, Ilyin-Genevsky, Levenfish, Réti, Tartakower, Spielmann and Brinckmann.

(4648)

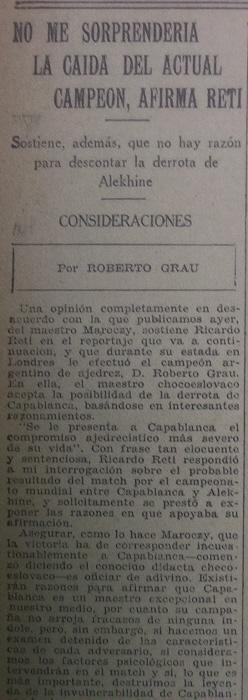

Concerning predictions as to the outcome of the 1927 world championship match we have come across the view of Réti as published on page 12 of the Argentinian newspaper La Nación of 14 September 1927 and quoted on page 209 of volume one of Historia del ajedrez argentino by José A. Copié (Buenos Aires, 2007):

‘To assert, as does Maróczy, that victory is bound to go to Capablanca ... is to act as a fortune-teller. There will be reasons for saying that Capablanca is an exceptional master in our field, in that his career has no failures of any kind, yet if we make a thorough study of the characteristics of each player, if we consider the psychological factors that will come into play in the match and if, more importantly, we destroy the legend of Capablanca’s invulnerability – which has become a reality among aficionados – we shall conclude that there are no fundamental reasons for affirming with such certainty that the Cuban grandmaster must necessarily defeat the talented Slav player.’

‘Capablanca has an apathetic temperament, he does not have further ambitions and he is incapable of preparing himself intensely for a match of this kind, since it is annoying for him to have to think. By dint of his natural talent he has arrived where he is, but he does not love chess. He is admirably instinctive but lacks the energy to undertake strict training.

Alekhine, in contrast, has an extraordinary wealth of energy. When engaged in battle, he is driven by noble eagerness to excel himself, and he has subjected himself to training commensurate with the importance of the match to be played ...’

Christian Sánchez has provided the complete text of the newspaper item, in which Roberto Grau reported comments made to him by Réti in London that summer.

(5665)

The topic of Réti’s comments was raised in C.N.s 37 and 1162. The latter item quoted from ‘Chess Giants in an Unseen War –15.9 - 29.11.1927’ by Dimitru Taraoiu, published in Bonus Socius (The Hague, 1977):

‘Réti manifested another opinion: “Capablanca is apathetic. His natural talent pushes him upwards, but he didn’t love chess. He does not possess energy for severe training. He has, indeed, admirable nerves supporting him in all situations. Pure genius can fail. Alekhine has a solid luggage of novelties and a great combinative spirit, always in pursuit of victory.”’

C.N. 1162 noted that this text was credited to La Nación, 17 September 1927.

See also Chess Predictions.

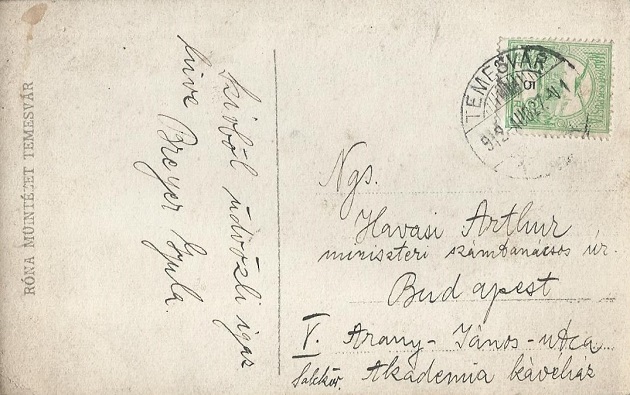

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has forwarded to us these two photographs of Richard Réti (Brussels, January 1924) from the collection of Daniël De Mol. Among the spectators is Edmond Lancel, who is standing second from the left in the first photograph and, in the other shot, sixth from the left, with Edgard Colle on his right. The photographs were taken during Réti’s tour of Belgium which was scheduled for late 1923 but was postponed owing to an accident sustained by Réti. Our correspondent draws attention to the following report to that effect in L’Indépendance Belge of 9 October 1923: ‘Par suite de l’accident dont Richard Réti a été victime il y a une quinzaine de jours, le grand maître tchécoslovaque nous prie d’annoncer que sa tournée en Belgique, prévue pour le début du mois d’octobre, ne pourra avoir lieu qu’au commencement du mois de novembre prochain.’ There were further delays, and the tour (Brussels, Ghent and Antwerp) eventually took place on 6-21 January 1924.

Mr Winants has a fine webpage [broken link] regarding the tour but has so far been unable to establish the nature of Réti’s accident.

(4690)

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Was Réti Jewish? Many sources, including some Hebrew-language ones, say that he was, but is reliable corroboration available?’

Richard Réti

(4834)

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) writes:

‘On page 9 of his book Richard Réti, šachový myslitel (Prague, 1989) Jan Kalendovský mentioned that Richard Réti was born in 1889 in Pezinok to Samuel Réti from Hlohovec and to Anna, née Mayerova, in a Pezinok Jewish family.

Richard’s brother Rudolph (1885-1957), a noted Viennese concert pianist, composer and musicologist, emigrated to the United States in the late 1930s and subsequently became an American citizen. His papers and the chess manuscripts and notes of Richard Réti are held at the Library of Congress.

Richard Réti is listed as a Jewish chessplayer in the Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1973) – see pages 401-409 of volume five and page 103 of volume 14 – but the chess editor, Gerald Abrahams, did not provide supporting references for his text.’

Richard Réti

(4856)

Further to the discussion in C.N.s 4834 and 4856 on whether Réti was Jewish, Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) points out a webpage devoted to Jewish studies, Compact Memory. He comments:

‘Réti had a chess column in the magazine Menorah (subtitled “Illustrated Monthly for the Jewish Home”) from February 1924 to May 1928. The July 1929 issue (page 433) featured an obituary of Réti which mentioned his honorary membership of the Chess Section of the Vienna Hakoah (a Viennese athletic club known for its Jewish football team).

It is interesting to note that his brother Rudolf (or Rudolph) had a column on music in the same publication (January 1924-September 1929).

The whole magazine is available on-line at Compact Memory. For example, on page 20 of the May 1924 Menorah Richard Réti’s brief annotations to his victory over Capablanca at New York, 1924 can be found.

A large number of other Jewish publications can also be consulted there. They include Ost und West, in which Emanuel Lasker conducted a chess column between November 1909 and February 1914.’

(5335)

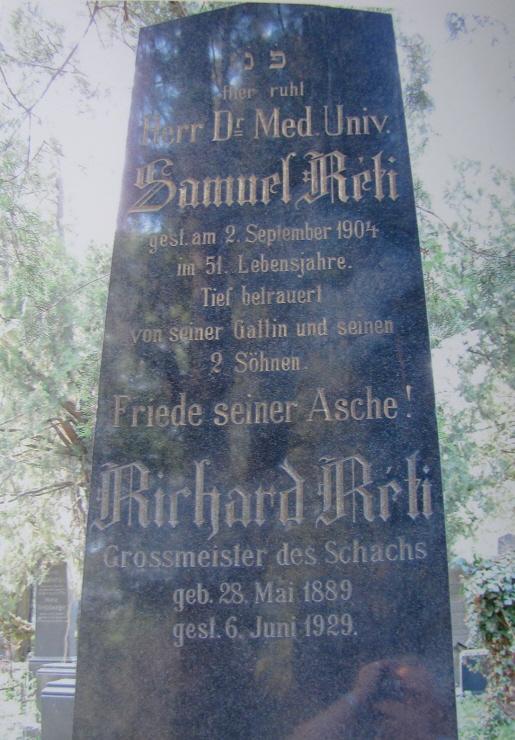

Michael Lorenz (Vienna) writes:

‘As far as is known, Réti was indeed Jewish. His father Samuel was Jewish and was buried in his parents’ grave in Vienna’s Jewish cemetery. He is not listed in Anna Staudacher’s book Jüdisch-protestantische Konvertiten in Wien 1782-1914 (Frankfurt am Main, 2004). Most Viennese chess masters were born Jewish, although many of them renounced Judaism. Prominent non-Jewish chess masters who come immediately to mind are Feyerfeil, Grünfeld, Hamppe, Kmoch, Krejcik, Liharzik, Marco, Mayerhofer, Müller, Schlechter and Seidl.’

(11533)

See Chess and Jews.

Andrew Templeton (Newmarket, Ontario, Canada) is seeking biographical information about John Hart, who translated into English Richard Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess (London, 1923). In particular, when did he die?

Readers’ assistance is requested. Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia has an entry for John Yealand Hart, who was born in London in 1884, and a reference to this item on page 418 of the October 1922 BCM:

Was J.Y. Hart of 56 Nibthwaite Road, Harrow the translator of Réti’s book?

(4885)

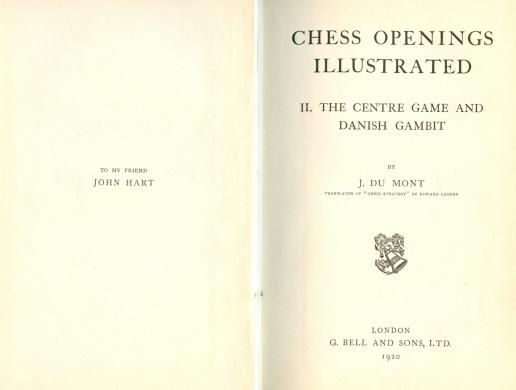

No further information about John Hart has yet come to light, but it may at least be mentioned that he was a friend of Julius du Mont, who dedicated to him his 1920 book on the Centre Game and Danish Gambit – Chess Openings Illustrated, volume two (London, 1920).

(5031)

On pages 213-215 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951) an extract from Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess was introduced by Reinfeld as follows:

‘Du Mont refers somewhere to Modern Ideas in Chess as a “lovable book”. The adjective comes as a surprise, but then I am reminded of the breathless eagerness with which I read Réti’s masterpiece as a schoolboy. The greatness of Réti’s achievement lies in this: his book not only gives us pleasure; it teaches us how to enjoy other books, other games. These modern ideas will always be modern.’

It seems likely that Reinfeld mixed up two books by Réti, because we recall that Julius du Mont made the following comment on page 50 of the March 1942 BCM:

‘Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board, a most lovable book ... It is as good as reading a novel.’

Is any information available about M.A. Schwendemann, the translator of Masters of the Chess Board?

(4892)

Richard Réti

Before proceeding, readers are invited to identify the five people in the above photograph.

It was taken during a small tournament in Bladel, the Netherlands in 1969, and the opening 1 d4 f5 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Nh6, played in one of the games, was christened the Bladel Variation. The average age of the participants was nearly 70, and the photograph shows all four of them: M. Euwe is facing K.Opočenský, and in the top right-hand corner are H. Müller and S. Flohr. The Dutch Defence game was a 12-move draw between Flohr and Euwe. Standing next to the Dutchman is the widow of Richard Réti; the tournament commemorated the 40th anniversary of his death.

The photograph comes from page 14 of CHESS, September 1969, which reported:

‘As an additional gesture, Réti’s widow has also been invited over from Moscow. She attended every round and watched all the games with great interest.’

Biographical information about her will be appreciated. On page 194 of the July 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung Hans Kmoch remarked that from the Moscow, 1925 tournament Réti brought back not only a ‘beauty prize’ for his game against Romanovsky but also a beautiful young Russian as his wife:

‘... Réti, der aus Moskau nicht nur den Schönheitspreis für seine Partie gegen Romanowski, sondern auch eine schöne junge Russin als Gattin mitgebracht hat, mit der er nun seine Hochzeitsreise unternimmt.’

On page 3 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess (London, 1954) Harry Golombek referred to Kmoch’s comment, and page 129 mentioned again the prize won by Réti for his game against Romanovsky. However, Golombek went astray on page 37 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966) by stating that Réti did not win such a prize in the Moscow, 1925 tournament. Referring to the opening ceremony of the Botvinnik v Tal world championship match in 1960 Golombek wrote:

‘One of the items this time was a prelude for pianoforte dedicated to Tal and Botvinnik. Afterwards I was introduced to the composer who, surprisingly enough, wasn’t a chessplayer. His connexion with the chess world was that his wife was the former Mrs Réti. Despite the passage of some 35 years since the remark was made, on looking at her I realized what was meant when it was said that Réti may not have won a beauty prize over the board at Moscow, 1925, but he had come away with one all the same. For this was the beautiful Russian girl whom he had met and married in Moscow that year.’

Can the name of Mrs Réti’s later husband be established (possibly from a souvenir programme for the opening ceremony of the 1960 match)?

(4912)

Michael Lorenz draws attention to the reference to Réti’s marriage on page 189 of Richard Réti šachový myslitel by Jan Kalendovský (Prague, 1989). Her maiden name was Rogneda Sergeievna Gorodetskaia, and she was the daughter of the Russian poet Sergei Gorodetsky (1884-1967). The couple met during the Moscow, 1925 tournament and married in Moscow on 28 May the following year (Réti’s 37th birthday). A footnote in the Czech book stated that in 1987 she was still alive, in Moscow.

Richard Réti

(4929)

There are two photographs of Réti’s wife on pages 29-33 of the Russian-language work Richard Réti by Anatoly Matsukevich (Moscow, 2005). See too C.N. 5041.

Richard Réti and Savielly Tartakower

David Lovejoy (Mullumbimby, NSW, Australia) mentions a claim by Tartakower that Réti tricked him out of an engagement for a simultaneous display in South America, as reported by Harry Golombek (in 14 lines) on pages 67-68 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966). Our correspondent asks when exactly Tartakower and Réti were both in South America.

(4983)

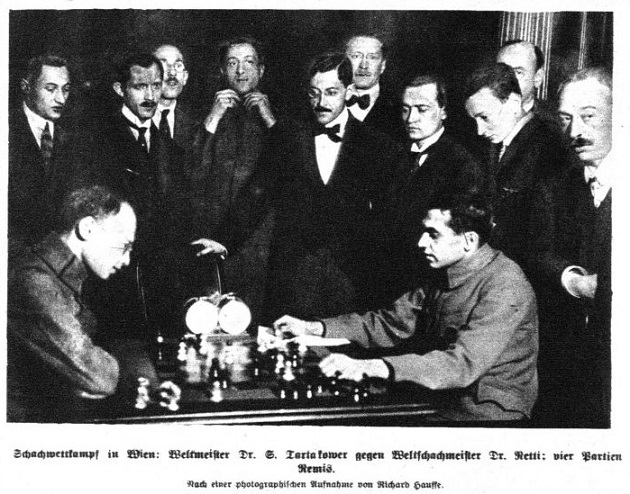

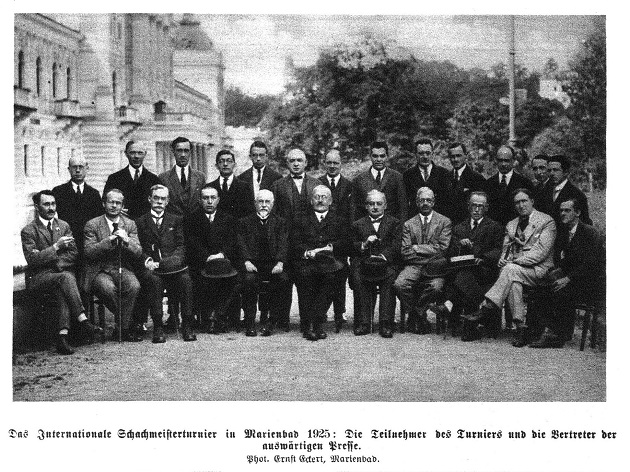

A group photograph from page 173 of the December 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

(4992)

Jan Kalendovský has been trying to identify all the figures in the group photograph of Marienbad, 1925:

He offers the following:

‘Seated (left to right): N.N., A. Nimzowitsch, R.P. Michell, A. Rubinstein, I. Gunsberg, N.N., V. Tietz, Sir George Thomas, D. Janowsky, F.J. Marshall, F.D. Yates

Standing: L. Burian, H. Kmoch(?), M. Walter, C. Torre, N.N., D. Przepiórka, R. Spielmann, R. Réti, E. Grünfeld, F. Sämisch, S. Tartakower, A. Haida, K. Opočenský.’

The photograph appeared at the start of the tournament book, with the caption ‘Tournament participants and guests’ (‘Teilnehmer und Gäste des Turniers’). Mr Kalendovský reports that it was originally published in the Wiener Bilder, 7 June 1925.

(5119)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) mentions that a key to the Marienbad, 1925 group photograph was published on page 89 of the May-June 1925 American Chess Bulletin. The additional information it supplies is:

(5125)

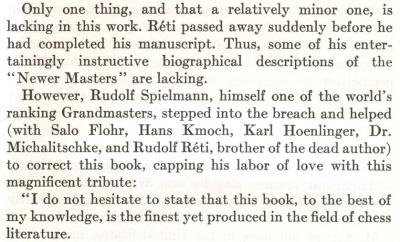

Below is a photograph taken during the Czech championship in Mladá Boleslav, 1913:

Source: Časopis Českých Šachistů, 9/1913, page 140.

(5186)

Further to the discussion on Pal Benko and ...b5 (see C.N.s 3957 and 3967), Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany) raises the wider question of the earliest occurrence in play of the general ideas behind the Benko Gambit (not necessarily in the first few moves). He proposes Marshall v Réti, New York, 1924, which was annotated on pages 37-40 of Alekhine’s book Das Grossmeister-Turnier New York 1924 (Berlin and Leipzig, 1925) and on pages 18-20 of the English translation.

The game began 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 c4 Bg7 4 Nc3 O-O 5 e4 d6 6 Bd3 Bg4 7 h3 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Nfd7 9 Be3 c5 10 d5 Ne5 11 Qe2 Nxd3+ 12 Qxd3 Nd7 13 O-O Qa5 14 Bd2 a6 15 Nd1 Qc7 16 Bc3

Réti played 16...Ne5, and Alekhine wrote: ‘Bereitet das folgende allzu kühne Bauernopfer vor – im Bestreben, gewaltsam remis zu vermeiden.’ [‘Preparing for the subsequent over-daring sacrifice of the pawn with the intention of avoiding a forced draw.’]

After 17 Qe2 b5 Alekhine commented:

‘Diesen Bauern konnte Weiß ruhig nehmen, da Schwarz Schwierigkeit gehabt hätte, dafür positionellen Ersatz zu erlangen, z.B. 18 c4-b5: a6-b5: 19 De2-b5:! c5-c4 (offenbar die beabsichtigte Pointe des Bauernopfers) 20 Lc3-e5: Lg7-e5: (oder 20...Tf8-b8 21 Db5-c6 Dc7-c6: 22 d5-c6: Lg7-e5: 23 Ta1-c1 Le5-b2: 24 Tc1-c4: mit Vorteil, da Schwarz den a-Bauern wegen 25 Tc4-c2 usw. nicht nehmen darf) 21 Sd1-e3 c4-c3 22 b2-c3: Dc7-c3: 23 Ta1-c1 und Weiß hätte zum mindesten ein sehr leichtes Remis gehabt. Nach der Ablehnung des Opfers wird er dagegen erst hart kämpfen müssen, um es zu erreichen.’ [‘White could safely have captured this pawn, as Black would have difficulty in obtaining positional compensation, for instance: 18 PxP PxP 19 QxP P-B5 (clearly the reason for the pawn sacrifice) 20 BxKt BxB (or 20...KR-Kt 21 Q-B6 QxQ 22 PxQ BxB 23 QR-B BxP 24 RxP with advantage, as Black dare not capture the QR pawn, on account of 25 R-B2) 21 Kt-K3 P-B6 22 PxP QxP 23 QR-B, and White would have had at least a very easy draw. After the refusal of the sacrifice, on the other hand, he can now reach that goal only after hard fighting.’]

The game continued 18 cxb5 axb5 19 f4 Nc4 20 Bxg7 Kxg7 and was drawn at move 50.

(5457)

Irving Chernev gave ‘some personal opinions’ on page 28 of the November-December 1933 Chess Review. The first was the following:

‘The perfect game is Réti-Kostić, Teplitz, 1922.’

(5624)

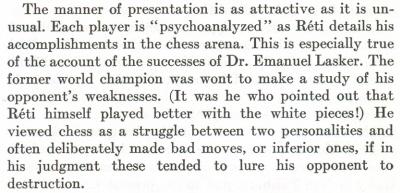

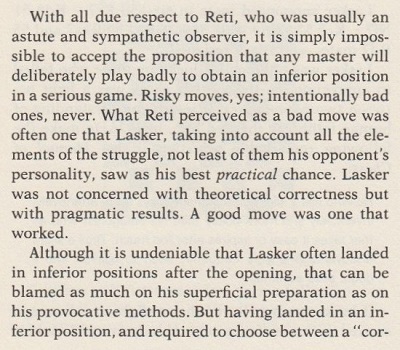

The section on Lasker in Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933) suggested that the former world champion ‘often deliberately plays badly’ (page 64). That claim is well known, but we wonder about this passage, regarding Réti himself, on page 173 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959):

‘Réti viewed chess as a struggle between two personalities and as his biographer, Horace R. Bigelow, stated, Réti “often deliberately made bad moves, or inferior moves, if in his judgment these tended to lure his opponent to destruction”.’

(5679)

Horton, we add now, had misconstrued a section on page v of Bigelow’s Introduction to the 1932 US edition of Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board:

At the start of the final sentence the word ‘He’ obviously refers to Lasker, not Réti.

Lasker’s reaction to some of Réti’s comments about him appeared in a letter on pages 357-358 of the 14 May 1936 issue of CHESS. It was reproduced in C.N. 2516 (see above).

Bigelow’s Introduction to Masters of the Chess Board also included, on page ix, this paragraph about Réti:

‘As a composer of endgames he was in a class by himself among the masters. His “positions” were all apparently simple and “natural-looking”, but in the words of the then world champion, José Raúl Capablanca: “Réti’s endings are the only ones worth solving and the only ones to give me trouble.”’

We have no information as to the source of the remark attributed to Capablanca.

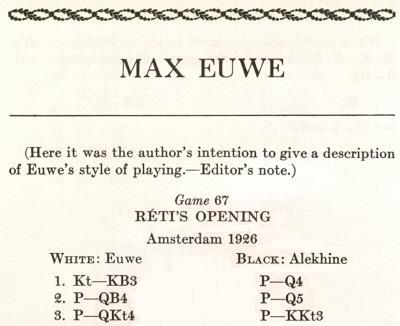

The Cuban wrote briefly about Réti’s book on page 82 of A Primer of Chess (London, 1935):

‘There are besides some interesting books of various kinds that are very useful to the expert or near-expert. One of the most interesting is Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board. I refer only to the part written by Réti himself. He died before the book was finished and someone else wrote the last part of the book, which cannot be compared with the first.’

Capablanca’s criticism may mystify readers of the British edition of Réti’s book (London, 1933). It ended with a 23-page section on Alekhine, whereas in the US edition that chapter was followed by further material: brief sections on Grünfeld, Euwe, Sämisch, Colle and Torre, with a single annotated game per master and no discussion. For example, page 420 began:

Page vii of Bigelow’s Introduction (which was also absent from the British edition of the book) supplied an explanation:

We do not read that text as justifying any suggestion of ghosting.

The same helpers had been acknowledged by Richard Réti’s brother in his Afterword on pages 395-396 of the German-language edition, Die Meister des Schachbretts (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930).

The British and US editions (which, textually, were by no means identical) stated on the title page ‘Translated from the German by M.A. Schwendemann’. (C.N. 4892 asked, without result, whether any information was available about him.) Page v of the British edition gave a brief note on Réti by Julius du Mont, but the latter had far more involvement in the English-language editions than might be thought. Details were supplied by du Mont himself in correspondence with Granville Whatmough, who quoted from it on page 196 of the July 1965 BCM (in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column):

‘The English edition of Réti’s book Masters of the Chess Board is entirely by him. The German edition has a few small chapters on Grünfeld, Euwe, Sämisch, Colle and Torre. These consist of one game each, the article describing their style of play is in each case missing in the German edition. I thought it best to leave out the whole thing because the inclusion of these with the exception of Euwe would debilitate Réti’s explanation why some great players, including English ones, were not included, namely that they had no influence on the history and the development of the game.

I would like to add that the translation which the British publishers bought from the Americans proved hopelessly inadequate, and I was commissioned by them to effect a thorough revision, in other words, translate the translation. I may say that the American publishers subsequently bought and adopted my revision.

Of course, the remarks of Capablanca referring to “the last part of the book”, etc. refer to that part in the German edition which was omitted in the English one.’

The above-mentioned ‘explanation’ by Réti about the selection of players was on, respectively, pages 216 and 107 of the US and British versions. The editorial involvement of du Mont in the English-language volumes is confirmed on page 248 of the June 1933 BCM, which stated that he had ‘revised the translation and annotations’. How thorough he was is another matter. Near the end of the introductory material in the Alekhine chapter it was stated that Alekhine wrote a book entitled My Hundred Best Chess Games. The equivalent erroneous claim (Meine hundert besten Schachpartien) had appeared on page 340 of the German original of Réti’s book, but du Mont might have been expected to correct the title in English, given that he was the co-translator of the Alekhine anthology in question, My Best Games of Chess 1908-1923 (London, 1927).

Euwe, for his part, had a longstanding grievance over Réti’s book. On page 21 of the April 1982 Chess Life Walter Meiden recalled concerning his co-author and friend:

‘He never said much about the opinion of others of his chess performance, but he deeply resented the fact that Richard Réti had almost decided not to include him in his Masters of the Chess Board.’

It may be wondered what grounds Euwe had for his belief about Réti’s intentions.

(6889)

Richard Réti’s remark that Emanuel Lasker ‘often deliberately plays badly’ was given in the section on the former world champion in Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933); on page 124 of the German edition (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930) the wording was ‘Lasker spielt oft absichtlich schlecht’. See too pages 404-405 of A Chess Omnibus, as well as C.N. 6889. We should like to give the full text of Réti’s original article (‘published after the New York tournament of 1924’).

A detailed study of Lasker’s play has just been published, John Nunn’s Chess Course (London, 2014), and it is unmissable.

In his Introduction (page 7) Nunn writes:

‘... the myth has developed that many of Lasker’s wins were based on swindles, pure luck or even the effect of his cigars. In reality, there was nothing mystical or underhand about his games; they were based on a deep understanding of chess, an appreciation of deceptive positions and some shrewd psychology. Another myth for which there seems no real evidence is that Lasker deliberately played bad moves in order to unsettle his opponents. Certainly Lasker played bad moves, as all chessplayers do from time to time, but the point which struck me when analysing his games was how often he adopted a safety-first strategy. Lasker was a great fighter and had a strong will to win, but his winning efforts hardly ever crossed the boundary into recklessness; in almost every case, he played moves that appeared provocative but were no worse than the alternatives, with the important difference that they were more likely to induce a mistake.’

(8660)

Concerning Réti’s claim that ‘Lasker often deliberately plays badly’, the idea was rejected on pages 18-19 of Benko and Hochberg’s Winning with Chess Psychology (New York, 1991):

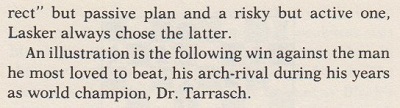

The book’s coverage of Lasker v Tarrasch, Mährisch-Ostrau, 1923 included the following on page 20:

Pages 286-287 of the Australasian Chess Review, 8 October 1936 published Lasker v Levenfish, Moscow, 1936, introduced thus:

‘Not often does one find an out-and-out Lasker game as described by Réti. Here is one that Réti would have seized on with shrieks of joy; the whole game pans out just as Réti would have it. First of all, the deliberately bad play, then the crisis when Lasker totters on the brink of the abyss, followed by the superb resourcefulness that upsets his opponent’s morale, culminating in the final collapse which makes Lasker the victor. It is all here, in this game.’

Levenfish’s annotations in the tournament book do not support the claim that Lasker deliberately played badly in that game (1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 e6 4 Be2 d5 5 d3 Nge7 6 Nf3 Nd4 7 O-O Nec6 8 Qd2 Be7 9 Bd1 O-O 10 Qf2 a6 11 Re1 Bf6 12 Ne2 dxe4 13 Nexd4 e3 14 Bxe3 cxd4 15 Bd2 Qd5 16 Qg3 Bd7 17 Ne5 Rfd8 18 c4 dxc3 19 bxc3 Be8 20 Bc2 g6 21 d4 Bg7 22 h4 Rac8 23 Be4 Qd6 24 Rad1 b5 25 h5 b4 26 hxg6 hxg6 27 Re3 bxc3 28 Bxc3 Nxe5 29 fxe5 Bxe5 30 Qh4 Rxc3 31 Rxc3 Bxd4+ 32 Kh1 Ba4 33 Rdd3 Bb5 34 Bxg6 fxg6 35 Rh3 Qd7 36 Rcg3 Bd3 37 Rxd3 Resigns).

(9684)

An observation by C.J.S. Purdy on page 43 of the March 1960 Chess World:

‘I have never believed that Lasker played designedly bad moves in the opening. I think he played designedly rapid moves – to conserve time – and it naturally turned out fairly often that they were not the best. And he would vary from “the book” if he thought a move had a good chance of turning out just about as good as the “book” move.’

(9837)

Richard Réti

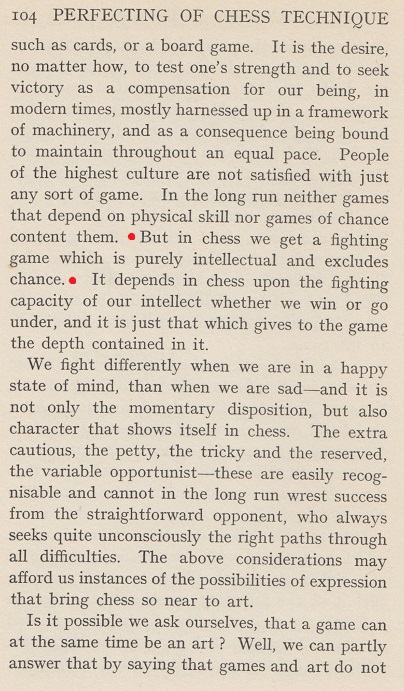

Peter Morris (Kallista, Victoria, Australia) quotes the final passage of Modern Ideas in Chess by Richard Réti (London, 1923):

‘But one thing is certain. If Americanism is victorious in chess, it will also be so in life. For in the idea of chess and the development of the chess mind we have a picture of the intellectual struggle of mankind.’

This text was on page 181 of the English edition but had not appeared in Die neuen Ideen im Schachspiel (Vienna, 1922). Where can the original be found?

(5828)

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) asks whether there is any truth to a story about Réti told by H. Golombek on pages iv-v of his Foreword to Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess (London, 1943):

‘... There is related an anecdote typical of the man. In the closing stages of an international tournament he was playing one of the weaker competitors and had obtained a won game. It was his turn to move – an obvious one since all he had to do was to protect a threatened piece. He seemed to fall into a brown study, did not move for ten minutes; then suddenly started up from his chair – still without making his move – and sought out a friend who was present in the congress rooms. To him he explained that he had just conceived an original and entrancing idea for an endgame study. Not without difficulty his friend dissuaded Réti from demonstrating and elaborating this idea on his pocket chess set, and Réti returned, somewhat disgruntled, to the tournament room, made some hasty casual moves and soon lost the game.

Without troubling at all about this loss, Réti at once returned to his hotel and spent almost the whole of the night in working out his endgame study. As a consequence he lost his next game through sheer fatigue and with it went his chances of first prize. He perfected a beautiful endgame composition at considerable financial loss.’

(5905)

In C.N. 5905 a correspondent asked about Golombek’s claim that Réti lost two consecutive tournament games through being preoccupied by an idea for an endgame study which occurred to him during play.

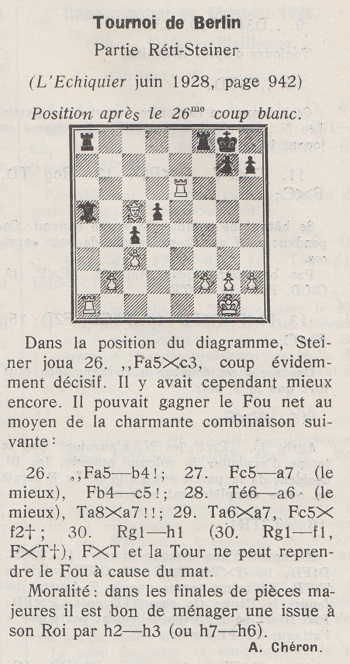

Now, Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) draws attention to a passage regarding the February 1928 tournament in Berlin in Jan Kalendovský’s monograph on Réti (see page 211 of the Czech original and page 374 of the Italian edition). It is stated that, after obtaining the better game against Brinckmann in round ten, Réti played 44 Nh5 but was informed that he had overstepped the time-limit. He then happily explained that the position on another board had inspired him to conceive a beautiful study. Still preoccupied with the study, he also lost his games against Tartakower and Steiner. His prize money was 500 Marks lower, but he produced the study, for which he received five Marks.

Corroboration of this account is sought.

(6016)

Two fine photographs of Nimzowitsch and Réti which we have occasionally reproduced from pages 159 and 82 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943) prompt a question from Maurice Carter: bearing in mind that the chess sets and boards appear to be identical, on what occasion were the photographs taken?

(5933)

Zdeněk Závodný (Brno, Czech Republic) notes that the same photograph of Réti, although showing more of the board position, was published in the 11 June 1929 issue of the Czech magazine Letem světem.

(5938)

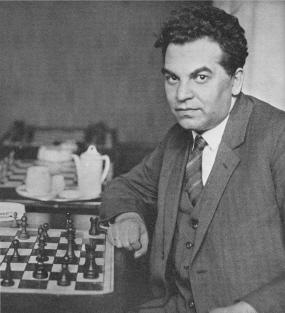

This position occurred after 21 Rfe1 in Tartakower v Réti, New York, 1924. Black played a rook to d8, but which rook?

The question has been put to us by Charles Sullivan (Davis, CA, USA), who comments that although various sources, including databases, give the next move as 21...Rad8, The Book of the New York International Chess Tournament 1924 by A. Alekhine (New York and London, 1925) put ‘KR-Q’ on page 191 and appended this note on the next page:

‘The queen’s rook stays at its own square in order eventually to make a demonstration on the queen’s side (P-QR4).’

We note, though, that page 267 of the German edition of Alekhine’s tournament book (Berlin and Leipzig, 1925) stated that the move played was 21...Rad8. Alekhine wrote that moving the king’s rook to d8 would have been an improvement:

Tartakower annotated the game, which he lost, on pages 220-222 of the August 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung. 21...Rad8 was the move given, with an exclamation mark. It may therefore be strongly suspected that 21...Red8 in the English edition of the New York, 1924 book was wrong, possibly owing to a misunderstanding and/or translation error, but the matter has yet to be put beyond doubt.

Notwithstanding the quality of Alekhine’s annotations, the book was a lax production. C.N. 2131 (see page 283 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) mentioned that W.H. Watts added a nine-page errata supplement (to the British edition, of which he was the publisher). The list sheds no light on the ‘Which rook?’ puzzle but is, of course, indispensable in connection with any English-language edition of Alekhine’s book.

(5954)

Position after 21 Rfe1

Concerning Tartakower v Réti, New York, 1924, David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) informs us that he owns Réti’s score-sheet, which clearly indicates that 21...Rad8 was played. Since that was also the move given by Tartakower (as shown in C.N. 5954), it seems evident that the English-language edition of the tournament book by Alekhine was wrong.

Regarding the nine-page errata supplement issued by W.H. Watts in 1925, see C.N.s 5954 and 5955.

(6009)

Lawrence Totaro (Las Vegas, NV, USA) asks whether evidence exists to back up this passage on page 46 of Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin (New York, 2008):

‘The Czech master Richard Réti once played 29 blindfolded games simultaneously. (Afterward he left his briefcase at the exhibition site and commented on what a poor memory he had.)’

We recall that the following appeared, without any source, on page 287 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994):

‘In São Paulo the same year [1925] he broke the blindfold record by playing 29 boards five days after Alekhine had set his own record with 28 in Paris. As the Czech master left the playing hall he forgot his familiar green briefcase. When it was returned to him Réti said, “Oh, thank you. I have such a bad memory.”’

The earliest reference to Réti’s briefcase that we can quote comes in a footnote on page 170 of Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie by S. Tartakower (Vienna, 1924):

On page 4 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess (London, 1954) Harry Golombek made use of the passage:

‘To quote Tartakower again: “He forgot everything, stick, hat, umbrella; above all, however, he would always leave behind him his traditional yellow leather briefcase, so that it was said of him: wherever Réti’s briefcase is, there he himself is no longer to be found. It is therefore evidence of Réti’s pre-existence.”’

A different version was given by J. du Mont on page v of Réti’s posthumous book Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933):

‘I can see him now, with his perennial smile on his good-humoured features, bustling along with his leather briefcase under his arm. It used to be a saying amongst his friends that where Réti’s briefcase was, there was Réti.’

(6020)

The accounts cited in C.N. 6020 disagreed as to whether Réti’s briefcase was green or yellow, and now Maurice Carter quotes from page 57 of With the Chess Masters by George Koltanowski (San Francisco, 1972):

‘He always carried an old black briefcase filled with reams and reams of sheets on which he had scrawled his comments, and dozens of addressed envelopes.’

On the following page Koltanowski gave a game he played against Réti, dating it 1929 instead of 1927.

(6026)

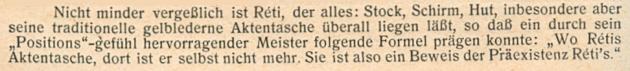

A contribution from Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) is this page from Das interessante Blatt of 26 March 1914:

Concerning Capablanca’s play in Vienna against Réti, as well as Fähndrich and Kaufmann, in 1914 see page 72 of our book on the Cuban. The game-scores were given in The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975).

Mr Urcan asks whether it is possible to identify any of the other players in the photograph. In particular, is Arthur Kaufmann there? Our correspondent informs us that he has Kaufmann’s death certificate and will, which show that he died in 1938, and not circa 1940 as given in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia.

(6232)

Erwin Huber (Munich, Germany) notes that when the Capablanca v Réti photograph appeared opposite page 81 of Ernst Franz Grünfeld by Michael Ehn (Vienna, 1993) the man standing second from the right was identified as Grünfeld.

(6236)

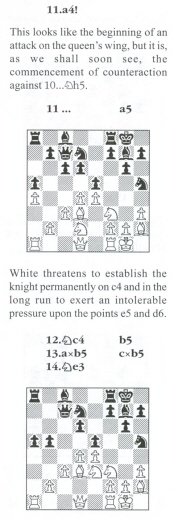

The above (concerning the game Bogoljubow v Réti, Berlin, February 1919) comes from page 115 of Modern Ideas in Chess by R. Réti (Milford, 2009) – a ‘21st Century Edition’ edited by Bruce Alberston.

What was known in the twentieth century is that page 157 of the English-language edition of Réti’s book in the descriptive notation (London, 1923 and London, 1943) erred by giving 11...P-R4 instead of 11...P-QR3. The double pawn move makes no sense, since the b5-pawn would remain continuously en prise later in the game. The error in the game-score was pointed out by Bernard Cafferty on page 215 of the May 1982 BCM.

We add that 11...a6 was given correctly on page 98 of the original German edition, Die neuen Ideen im Schachspiel (Vienna, 1922), as well as in such sources as page 229 of the November 1919 Deutsche Schachzeitung and page 30 of Schachjahrbuch 1919 by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1920).

The ‘21st Century Edition’ has added many diagrams to the game, with the black a-pawn consistently misplaced on a5.

When planning to reprint or otherwise reissue an old book, publishers could easily make an open appeal for information about errors which anyone may have marked in his copy of the original. Yet publishers do not do so. Why not?

(6776)

This photograph, taken by Miloslav Salomounek, has been sent to us by Jan Kalendovský:

We have also received a photograph from Stanislav Vlček (Bratislava, Slovakia):

The location is the Jewish part of the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna

(Section T1, Group 51, Row 5, Grave 34), and Mr Kalendovský draws

attention to an article

about Réti’s grave [broken link].

(6821)

Concerning the grave of Richard Réti in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna, we have received the following from Michael Lorenz (Vienna):

‘It is not Réti’s body that is buried there, but the urn containing his ashes. The urn was buried in Vienna on 30 June 1929. Owing to the cause of his death, Réti’s body had to be cremated in Prague.

The source for this information is the card catalogue of Jewish graves in the archive of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde (IKG) in Vienna. The basic information (i.e. the location of the grave and the date of Réti’s burial) can also be accessed at the Abfrage Friedhofs-Datenbank webpage.’ [Broken link.]

(6854)

See also Graves of Chess Masters.

On page 232 of the August 1970 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld wrote:

‘... a phrase like “Alekhine’s Best Games” is really ambiguous: it may mean two entirely different things, viz. (a) the games Alekhine played best and (b) the objectively best games in which Alekhine was a participant (in which the standard of the game is achieved by both partners) – thus he need not necessarily have won them. This, in fact, is the basis of my anthology Grosse Remispartien.

In fact, it is little short of ludicrous that Alekhine’s Best Games does not contain his draw against Marshall at New York, 1924, where a most original and new strategic conception by Marshall is met by an amazing tactical finesse of Alekhine’s, the whole (drawn) game being one of the greatest ever played. It is similarly ludicrous that Golombek’s anthology of Réti’s Best Games is without his draw against Alekhine at Vienna, 1922 – which has been christened the Immortal Draw and which even Alekhine does not pass over in his own collection. Similarly some game collections of Tal’s are deprived of the fantastic draw against Aronin at the 24th Soviet championship (Moscow, 1957) – a game of which Keres stated in a much-acclaimed article that one could not do justice to Tal’s achievement in that tournament without coming to grips with it.’

(7049)

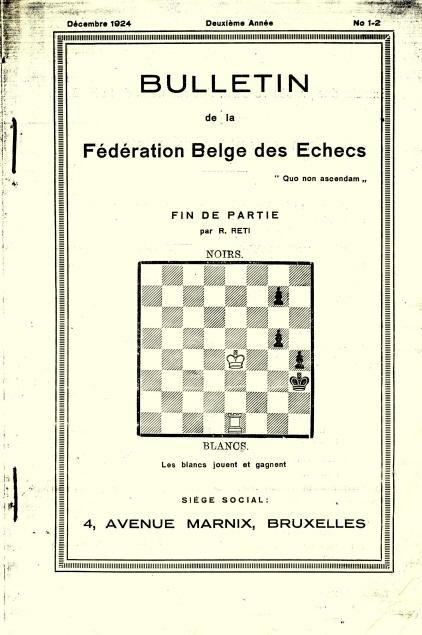

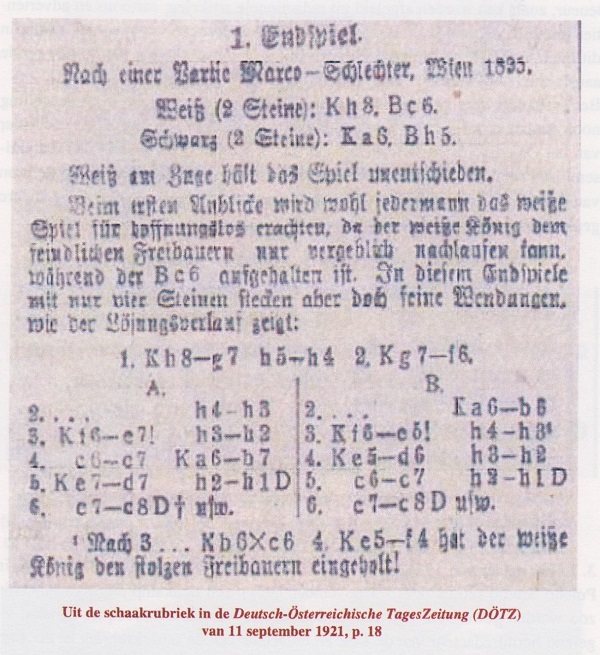

When Luc Winants forwarded the FIDE material mentioned in C.N. 7282, he included the cover page of the December 1924 issue of the Bulletin de la Fédération Belge des Echecs:

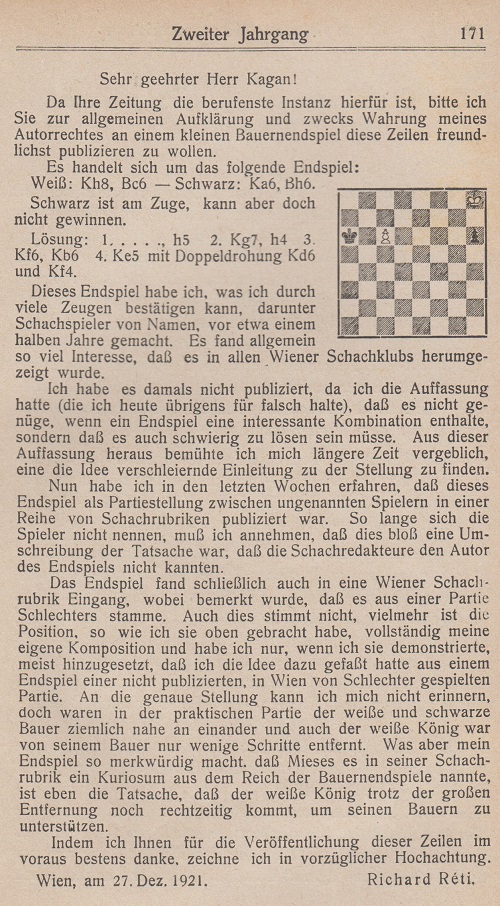

We are intrigued by the Réti study, which is not included in the standard books and databases. It is, though, similar to a composition (‘Verbessert nach Tijdschrift 1922’) given on page 26 of Richard Réti: Sämtliche Studien (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1931), the sole difference being that the rook is on f2.

Readers are invited to ponder the study in the Belgian magazine, and a future item will revert to this topic.

(7283)

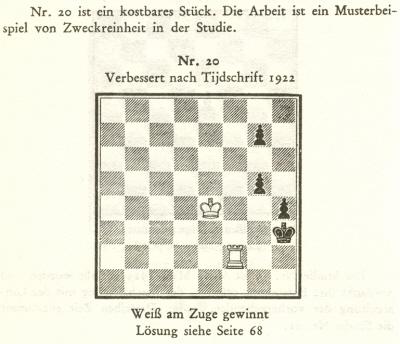

From page 26 of Richard Réti: Sämtliche Studien (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1931):

Can this study be found in any year(s) of the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond?

(7316)

Reporting that no progress had been made with this enquiry, C.N. 7468 drew attention to John Beasley’s compilation of studies by Réti.

From Gaffes by Chess Publishers and Authors:

C.N. 2397 commented that:

.. in 1997 Batsford produced a reprint of Golombek’s book on Réti, putting ‘Golmbek’ on the frnt cver.

John Nunn gave an account of the matter on page 283 of his book Grandmaster Chess Move by Move (London, 2005):

‘David Cummings proudly gave me a copy of a book I had edited, Richard Réti’s Best Games (by Harry Golombek), which had just arrived from the printer. I pointed out that they had spelt the author’s name “Harry Golmbek” on the front cover. David Cummings, who did not come from a publishing background, had assumed that if you hand a cover designer a disc containing the cover text, it will come out correctly. Needless to say, the books went out with “Golmbek” on the cover.’

Below is an example of Franz Gutmayer’s output, from pages 20-21 of his book Der fertige Schach-Praktiker (Leipzig, 1923):

In the Capablanca v Réti game (London, 1922) neither player overlooked that the Cuban’s king was in check. It was on e1, and the white rook was on c1, not a1. Black had a pawn on b5.

(7392)

Regarding Spielmann’s preferred first move as White, Reinfeld wrote on page 117 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘There is an interesting story related to the following fine finish, played in the Trentschin-Teplitz tournament of 1928. Réti started the game with 1 P-Q4, and Spielmann was so impressed by the overwhelming drubbing that he received that he thereupon started playing 1 P-Q4 after a lifetime of beginning with 1 P-K4.’

Is there any substance to the story? When the game was published on pages 85-86 of Reinfeld and Chernev’s Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) the suggestion was more speculative:

‘One of the many sensations of the great Carlsbad (1929) tournament was Spielmann’s belated renunciation of his beloved P-K4 in favor of Queen’s Pawn openings. The suddenness of the change was no less astonishing than the stubbornness with which Spielmann had previously clung to the King’s Gambit and similar openings. Perhaps the clue to this surprising change will be found in the overwhelming drubbing administered by Réti in the following elegant game.’

The Réti v Spielmann game, played on 23 May 1928, was annotated by Spielmann on pages 146-147 of the May 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung. His closing remark may be quoted in passing:

‘Gerade gegen mich spielt Réti immer das beste Schach. In welchem Gegensatz dazu steht sein auffallend schwaches Spiel in mehreren anderen Partien des gleichen Turniers.’

The Carlsbad tournament began over a year after the Réti v Spielmann game was played. During the intervening period, Spielmann played 1 d4 a number of times: v Bogoljubow at Bad Kissingen, 1928, v Vajda at Budapest, 1928 and v Réti and Capablanca at Berlin, 1928. He had also played it occasionally earlier in his career.

(7852)

A brief extract from our feature article on World Champion Combinations by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller (New York, 1998):

Chapter 6, dealing with Capablanca, has six games and four positions:

1. Réti-Capablanca, Berlin, 1928. A one-sentence note at move 10 reads ‘White miscalculates and Black won’t be able to take advantage of the exposed queen’. That is the exact opposite of the intended meaning; ‘and’ should read ‘that’. (This time it is a case of unsuccessful copying from page 58 of Schiller’s 1997 companion volume, World Champion Openings.) There is also an inaccurate concluding note. Following 17…Bf3 it is stated, ‘The sacrifice must be accepted, or else …Qh3 is an easy win’. Yet after 18 gxf3, the move 18…Qh3 was indeed played, with such an easy win that Réti at once resigned.

After examining the remainder of that section, we concluded:

Not one of the ten Capablanca games and positions given by Keene and Schiller emerges with a clean bill of health.

Below is the text of C.N. 3048 (see page 54 of Chess Facts and Fables), concerning a familiar miniature:

Lukomsky – Pobedin

Moscow, 1929

Queen’s Fianchetto Defence1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 Nc3 e6 4 e4 Bb4 5 e5 Ne4 6 Qg4 Nxc3 7 bxc3 Bxc3+ 8 Kd1 Kf8 9 Rb1 Nc6 10 Ba3+ Kg8 11 Rb3 Bxd4

12 Qxg7+ Kxg7 13 Rg3+ Resigns.

Some sources (including the Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1929, pages 184-185) gave Pobedin’s name as ‘Podebin’.

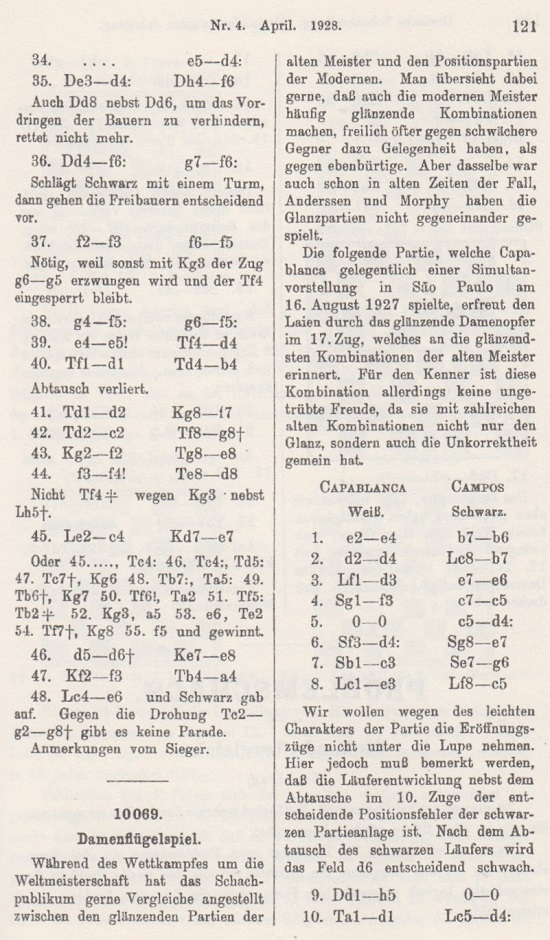

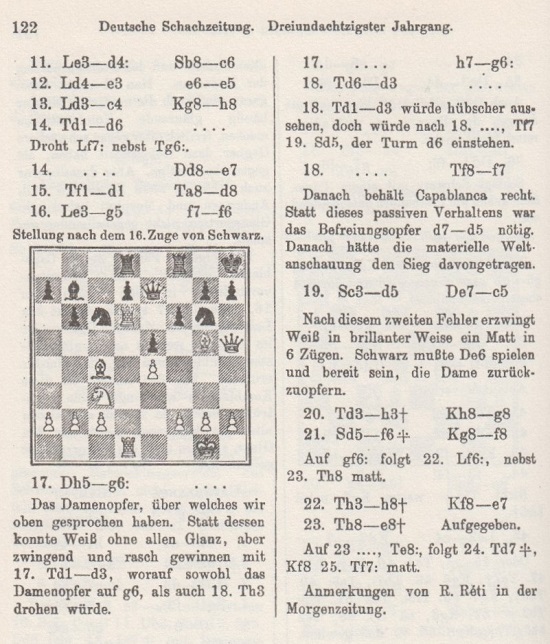

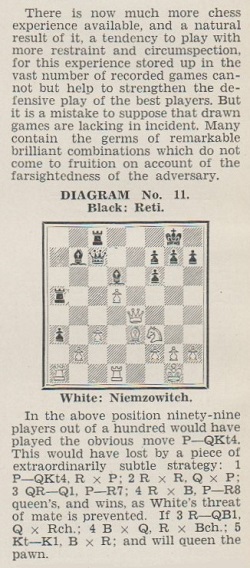

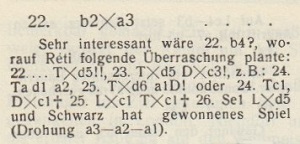

The game illustrates how prominent masters may differ in their appreciation of games and positions. Annotating the miniature on pages 122-124 of the June 1930 Ajedrez, Tartakower gave White’s 12th move two exclamation marks and referred to ‘this splendid queen sacrifice’. On page 178 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955) Irving Chernev reported that Marshall ‘was fond of this game’. In contrast, Réti found the combination ‘banal and uninteresting’. He was writing in Morgenzeitung, and his notes were reproduced on pages 218-219 of the July 1929 Deutsche Schachzeitung. Below is that item, followed by page 5 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1954):

(7900)

The remainder of C.N. 7900 is given in our feature article on Tartakower.

From page 105 of The Amazing Book of Chess by Gareth Williams (Godalming, 1999), in the section on Capablanca:

‘His losses became so rare that on one occasion the front page headline of the New York Times read “Capablanca Loses”.’

That sounds even more dramatic than what Harold C. Schonberg wrote on page 166 of Grandmasters of Chess (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

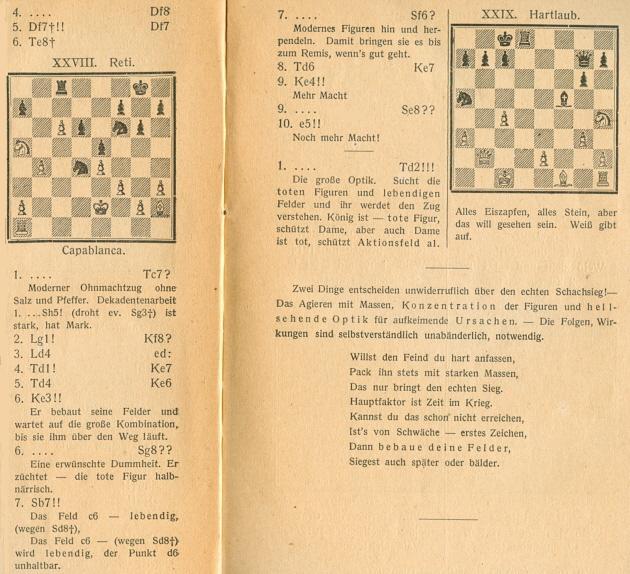

‘At the New York, 1924 tournament he lost to Réti. So unexpected was that loss, so unbeatable had Capablanca been, that the New York Times commemorated Capablanca’s loss in a headline: CAPABLANCA LOSES/1ST GAME SINCE 1914. (The Times for once was inaccurate, for Capablanca had lost a game to Chajes in New York in 1916.)’

So, just how eye-catching was the newspaper’s front-page story on 23 March 1924, the day after the Cuban’s loss to Réti?

Contrary to the statement in the New York Times, the Cuban’s unbroken run (apart from the loss to Chajes in 1916) stretched back to his defeat by Tarrasch, and not Lasker, at St Petersburg, 1914.

(8205)

C.N. 8205 showed the report of Capablanca’s loss to Réti on the front page of the sports section of the New York Times, 23 March 1924.

There was no mention of the game on the newspaper’s very front page.

(8217)

See also Chess as Front-Page News.

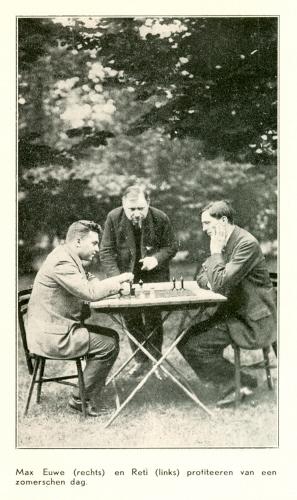

C.N.s 5187 and 5197 gave the above photograph, taken from Aljechin-Euwe by Guus Betlem Jr (Helmond, 1936), and in the latter item Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) suggested persuasively that the figure standing between Réti and Euwe was Willem Schelfhout.

Mr de Jong now forwards another picture, from page 4 of De Telegraaf (morning edition), 12 July 1923:

The setting and furniture being similar, our correspondent concludes that the Réti v Euwe picture was also taken during the Mährisch-Ostrau, 1923 tournament.

(8355)

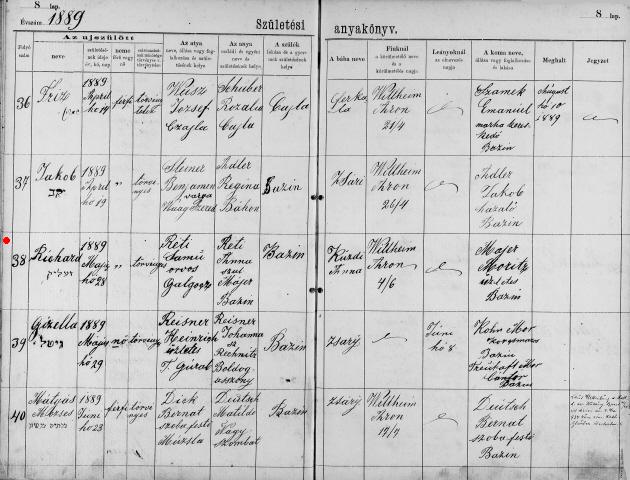

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) informs us that a colleague of his, Alon Schab, recently noted Richard Réti’s birth record in the database of the Latter-Day Saints church (the Mormon Church):

Mr Pilpel comments:

‘Below the word “Richard” there appears, in Hebrew letters, the name זעליק – “Selig”. If a comparison is made with the other lines, it seems clear that this is Réti’s “Jewish” name, which would make his full name Richard Selig Réti.’

(8629)

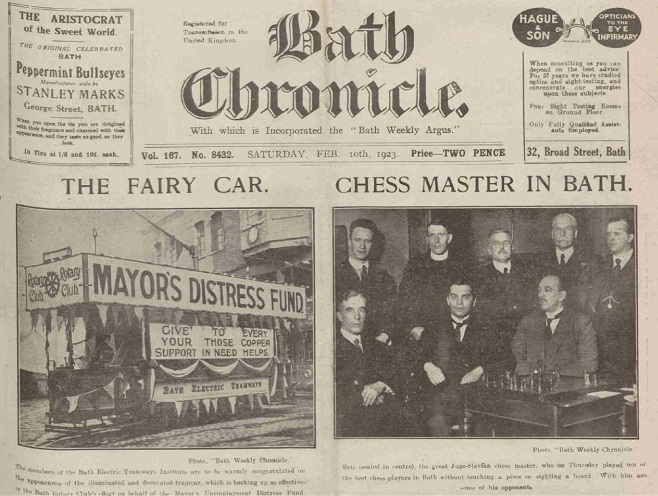

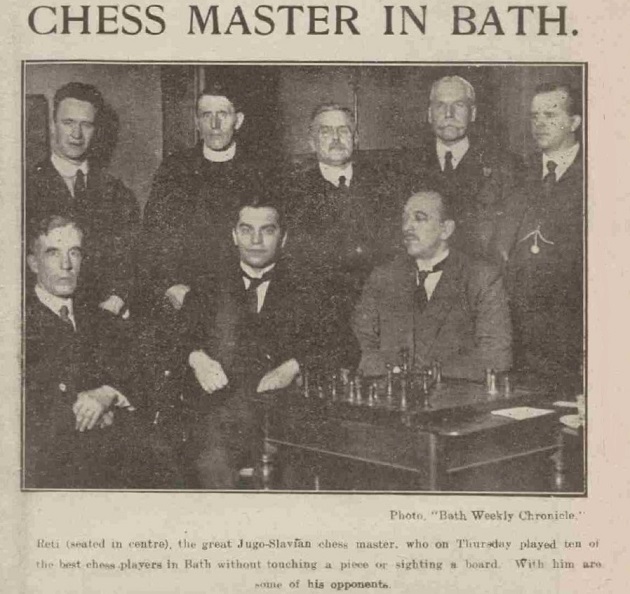

Olimpiu G. Urcan has found the cuttings presented below:

Bath Chronicle, 10 February 1923, page 1.

From the Burnley Express of 23 April 1927 (page 3), 30 April 1927 (page 11) and 4 May 1927 (page 5) come reports of a 21-board simultaneous display, including three games which Mr Urcan has transcribed (diffidently in view of the newspaper’s imperfect use of the descriptive notation):

John Robinson – Richard Réti

Burnley, 26 April 1927

Four Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bc4 Bb4 5 d3 d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Bxd5 Qxd5 8 Bd2 Bxc3 9 Bxc3 O-O 10 O-O Bg4 11 Re1 Rfd8 12 Qe2 f6 13 Qe4 Qxe4 14 Rxe4 Bxf3 15 gxf3 Kf7 16 Rg4 h5 17 Rg2 Nd4 18 Bxd4 Rxd4 19 Kf1 Rad8 20 Rd1 c5 21 Ke2 b5 22 Rh1 Rh4 23 Rg3 Rdd4 24 c3 Rdf4 25 a3 c4 26 dxc4 bxc4 27 b4 Rf5 28 h3 Rhf4 29 h4 e4 30 Rhh3 exf3+ 31 Rxf3 Rxf3 32 Rxf3 Rxf3 33 Kxf3 g5 34 hxg5 fxg5 35 Kg3 Kf6 36 Kf3 Ke6 37 Ke4 Kf6 38 Kf3 Ke5 39 Kg3 Kf6 40 f3 Ke6 41 f4 h4+ 42 Kg4 h3 43 Kxh3 gxf4 44 Kg2 Ke5 45 Kf3 Kf5 46 a4 Ke5 47 a5 Resigns.

Richard Réti – A.A. Bellingham

Burnley, 26 April 1927

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Qf3 Qh4+ 4 g3 Qf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 Nd5 Qd8 7 gxf4 Nf6 8 Nxf6+ Qxf6 9 c3 h5 10 d4 d6 11 f5 Qh4+ 12 Kd1 g5 13 Bd3 Bh6 14 Qg3 Bd7 15 Qxh4 gxh4 16 Bxh6 Rxh6 17 Nf3 O-O-O 18 Rg1 Ne7 19 Ke2 Ng8 20 Rg7 Rf8 21 Rag1 Nf6 22 h3 Rhh8 23 Nxh4 Ne8 24 R7g3 Nf6 25 c4 Re8 26 Ke3 c6 27 Kf4 b6 28 d5 c5 29 Nf3 h4 30 Rg7 Nh5+ 31 Ke3 Nxg7 32 Rxg7 Bxf5 33 Rxf7 Bxe4 34 Rf4 Drawn.

Walter Cole – Richard Réti

Burnley, 26 April 1927

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nbd2 b6 4 e3 Bb7 5 Be2 c5 6 c3 cxd4 7 cxd4 Be7 8 O-O O-O 9 b3 d5 10 Bb2 Nbd7 11 Bd3 Rc8 12 Rc1 Bd6 13 Qe2 Qe7 14 Ne5 Ba3 15 Nb1 Bxb2 16 Qxb2 Nxe5 17 dxe5 Nd7 18 Nd2 f6 19 exf6 gxf6 20 f4 Rf7 21 Nf3 Nc5 22 Bb1 Kh8 23 b4 Ne4 24 Rxc8+ Bxc8 25 Bxe4 dxe4 26 Nd4 Rg7 27 Nc6 Qf7 28 Qd4 Qg6 29 Rf2 Rd7 30 Qa1 Rd3 31 Qe1 Qh5 32 Rd2 Qb5 33 Rc2 Ba6 34 Nd4 Qa4 35 Rc1 Qd7 36 Qh4 Qd8 37 Qf2 Bc4 38 h3 b5 Drawn.

(8960)