Edward Winter

Alexander Alekhine

From page 99 of Chess Lists by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 2002):

‘Against Richard Réti at Baden-Baden 1925, Alekhine omitted two moves that repeated the position in what turned out to be perhaps his finest game.’

Having found three versions of the game-score, we wonder whether the matter is so clear-cut.

The Baden-Baden tournament books by Tarrasch (Berlin, 1925) and by Caissa Editions (Yorklyn, 1991).

Alekhine’s second volume of Best Games;

Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft by Alekhine (Berlin and Leipzig, 1932);

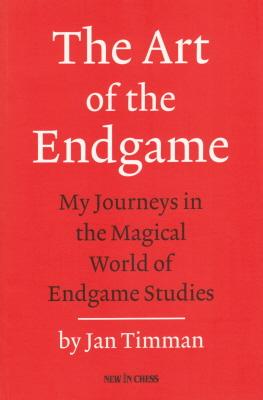

Pages 100-101 of L’Echiquier, May 1925 (notes by Alekhine);

The Baden-Baden tournament book by N. Grekov (Moscow, 1927). It gave Alekhine’s annotations from Shakmaty, which were the same as those published in L’Echiquier;

G. Renaud, in L’Eclaireur du Soir, as reproduced on page 75 of the April 1925 L’Echiquier;

A. Rubinstein in La Nation Belge, as reproduced on page 124 of the June 1925 La Stratégie;

C.S. Howell in the American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1925, pages 94-95;

Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 6 (1926), page 182.

R. Spielmann, Wiener Schachzeitung, May 1925, pages 135-136;

Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1925, pages 147-148.

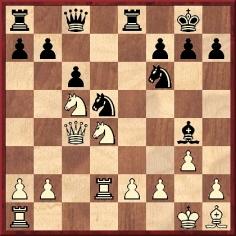

Position before ...h5

So, did Alekhine play ...h5 on move 22, 20 or 18? Did he really abridge the score, even though his version is by far the most common and despite publication in the Wiener Schachzeitung and the Deutsche Schachzeitung of a version that was shorter still?

When the game was presented on pages 35-40 of Chess Masterpieces by F.J. Marshall (New York, 1928) the United States champion introduced it as follows:

‘At the conclusion of the 1927 New York tournament I asked Dr Alekhine, now the world’s champion, which he considered to be his best game, and was pleased when he selected the one he played against Réti in the 1925 Baden-Baden tournament. I was present when this fine game was played and won the admiration of both the masters and the public. Dr Alekhine thinks he has nothing to add to the notes made by Mr C.S. Howell in the American Chess Bulletin and the comments I made in discussing this remarkable game.’

The game-score followed (version B above), with notes adapted from Howell’s on pages 94-95 of the May-June 1925 American Chess Bulletin. Howell mentioned that Réti had annotated the game in La Prensa (Argentina), and we should like to know which version of the game-score Réti gave.

(5632)

C.N. 5632 pointed out that three versions of the game Réti v Alekhine, Baden-Baden, 1925 have been found:

The Baden-Baden tournament books by Tarrasch (Berlin, 1925) and by Caissa Editions (Yorklyn, 1991).

Alekhine’s second volume of Best Games;

Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft by Alekhine (Berlin and Leipzig, 1932);

Pages 100-101 of L’Echiquier, May 1925 (notes by Alekhine);

The Baden-Baden tournament book by N. Grekov (Moscow, 1927). It gave Alekhine’s annotations from Shakmaty, which were the same as those published in L’Echiquier;

G. Renaud, in L’Eclaireur du Soir, as reproduced on page 75 of the April 1925 L’Echiquier;

A. Rubinstein in La Nation Belge, as reproduced on page 124 of the June 1925 La Stratégie;

C.S. Howell in the American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1925, pages 94-95;

Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 6 (1926), page 182.

R. Spielmann, Wiener Schachzeitung, May 1925, pages 135-136;

Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1925, pages 147-148.

Thus the question was whether ...h5 was played at move 22, 20 or 18. Our item furthermore asked if Réti’s annotations to the game, in La Prensa (Buenos Aires), could be traced, and we are now grateful to Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) for providing them. He writes:

‘The game was played on 25 April 1925, and Réti’s analysis appeared on page 13 of the 28 April issue of La Prensa, his article being dated 27 April. Réti stated that ...h5 was played at move 22, Alekhine having offered a draw on the previous move.’

Mr Sánchez points out that Réti criticized three of his moves:

(6358)

From page 7 of Timman’s The Art of the Endgame (C.N. 7418):

‘The world of chess was the most fascinating. I devoured Euwe’s books. The memory of the game Réti-Alekhine, annotated in his book Practical Chess Lessons, which never ceased to amaze me: the black rook appearing on e3 and remaining en prise there for several moves.’

C.N.s 5632 and 6358 discussed the unresolved matter of the contradictory versions of the game-score:

A) 18 Bg2 Bh3 19 Bf3 Bg4 20 Bg2 Bh3 21 Bf3 Bg4 22 Bh1 h5;

B) 18 Bg2 Bh3 19 Bf3 Bg4 20 Bh1 h5;

C) 18 Bh1 h5.

In other words, it is currently unknown whether the game ended with 42...Nd4, 40...Nd4 or 38...Nd4.

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) notes that version B was given on pages 653-654 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952). We add that it was also version B that Tartakower annotated on pages 97-99 of his book Schachmethodik (Berlin, 1928 and 1929).

(7436)

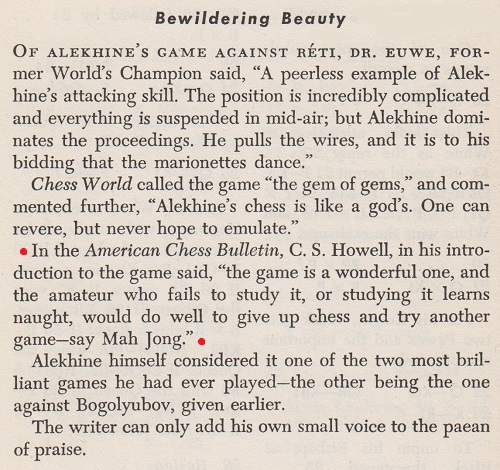

When presenting Réti v Alekhine, Baden-Baden, 1925 (under the heading ‘The Gem of Gems’) on pages 110-111 of the 1 June 1946 issue of Chess World, C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘We disagree with Mr Goldstein when he says that Alekhine’s chess is easier for the ordinary player to understand than Capablanca’s. Capablanca’s moves may often surprise, but usually their logic is soon apparent after examination. But many of Alekhine’s moves depend on some surprise that comes far too many moves ahead for an ordinary mortal to have the slightest chance of foreseeing it. Alekhine’s chess is like a god’s. One can revere, but never hope to emulate.’

(9384)

After 19 Bf3 Bg4 Purdy wrote on page 110 of Chess World, 1 June 1946:

‘Here Alekhine erroneously claimed a draw by recurrence of position. The position has occurred only twice, and even had it occurred three times Black could not claim a draw because a draw by recurrence can be claimed only by the “Player”, i.e. the one whose turn it is to move. Had Réti now played 24 B-N2, Black could then have claimed successfully. Having a slight superiority in position, Réti decides to evade the draw. Not, of course, by allowing the exchange of his fianchetto bishop, as that would seriously weaken his white squares.

Alekhine may have made the absurd claim deliberately to make Réti over-confident.’

Purdy’s notes were reproduced, without specification of the original source, on pages 56-58 of C.J.S. Purdy’s Fine Art of Chess Annotation and Other Thoughts compiled and edited by Ralph J. Tykodi (Davenport, 1992).

Alekhine played 16...Bh3

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) writes:

‘How were the repetition rules applied at the time? Did a claim have to be made by one of the players, or could a referee/judge impose a decision without the players’ agreement?

If the tournament books (by Tarrasch and Grekov) and Réti’s annotations in La Prensa are accurate, version A of this game would seem to be illegal under modern rules, whereas versions B and C would both be legal, under a modern or a 1925 interpretation of the rules.

Whichever sequence is believed, it is important to remember that Alekhine’s repetition offer forced Réti’s hand, and Réti had the last word on whether to accept the draw. Alekhine’s annotations (and apparently Réti’s in La Prensa) support this point.

After 17...Bg4 (version B), Alekhine says this on page 11 of his second volume of best games (London, 1939):

“Giving the opponent the choice between three possibilities: (1) to exchange his beloved ‘fianchetto’ bishop; (2) to accept an immediate draw by repetition of moves (18 B-Kt2 B-R6 19 B-B3, etc.) which in such an early stage always means a moral defeat for the first player, and (3) to place the bishop on a worse square (R1). He finally decides to play ‘for the win’ and thus permits Black to start a most interesting counter-attack.”When Réti finally refused the draw with 20 Bh1 (again, in version B), Alekhine exclaimed, “At last!”

Alekhine annotated the phase after 17...Bg4 slightly differently in his book On the Road to the World Championship 1923-1927 (Oxford, 1984). From page 53:

“Now White is faced with an unpleasant choice. Obviously he cannot very well allow the exchange of bishops, because this would weaken his king’s position and grant the opponent equality at least, but to agree to a draw by an automatic repetition of moves would amount to an implicit admission that his novel treatment of the opening is by no means convincing. So there is nothing left but the modest retreat to h1, which is what he decides on in the end. This allows Black the gain of an important tempo, however.”

This is C.J. Feather’s translation of Alekhine’s text on pages 53-54 of Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1932).

Euwe gave version B on pages 43-47 of Meet the Masters (London, 1940). After 19...Bg4 he introduced an idea which I have not seen elsewhere:

“And Alekhine claimed a draw by repetition of moves. Réti protested, and the tournament director ruled that the automatic draw by repetition had not yet come about.

The reporters wrote nothing about this; and some, in reproducing the game, omitted the repetition completely, publishing scores reading 16...B-R6 17 B-B3 B-Kt5; 18 B-R1. Yet the precise circumstances contribute useful evidence towards a correct judgment of the situation.

Réti now went 20 B-R1 and now Alekhine knew that, if he were to get a draw, he would have to fight for it.”

Examples of the omission of the repetition, as referred to by Euwe, are given in your article as version C: the 1925 Wiener Schachzeitung (Spielmann) and Deutsche Schachzeitung.

Both Réti and Alekhine were evidently aware of the repetition issue. Thus, the sporting question is not when Alekhine played ...h5, but when Réti played Bh1 and refused the draw.

In your feature article on repetition John Nunn referred to “world championship games from the early twentieth century” and wrote, “As I understand it, at one time the repetition rule required that the moves had to be repeated, rather than the positions”. The context of his point predates the Réti-Alekhine game, but it may be asked whether the same idea is relevant to the 1925 game.

It is unclear whether Réti and Alekhine had the same interpretation of the repetition rule. Although Réti was writing almost immediately after the game was played, it cannot be assumed that he, and not Alekhine, provided an accurate account of the move order.’

(9423)

The introduction to the Réti v Alekhine game on page 85 of Bobby Fischer and his Predecessors in the World Chess Championship by Max Euwe (London, 1976):

‘... the deepest strategical combination with rooks and light pieces ever played.’

From page 142 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

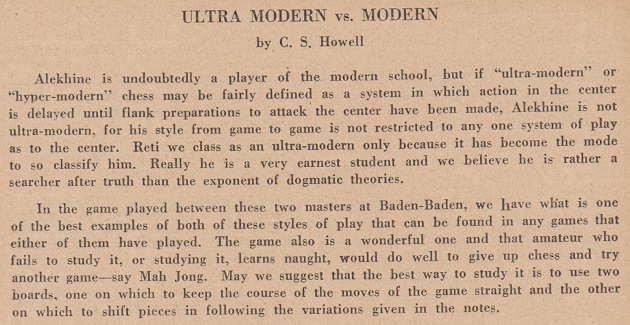

C.S. Howell’s notes are referred to in our feature article, and below is his full introduction (with the familiar Mah Jong remark), from page 94 of the May-June 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

(10235)

Concerning the penultimate paragraph by Chernev given in C.N. 10235, we add Alekhine’s final note to his win over Réti on page 13 of his second Best Games volume (London, 1939):

‘I consider this and the game against Bogoljubow at Hastings, 1922 (cf. My Best Games 1908-23) the most brilliant tournament games of my chess career. And by a peculiar coincidence they both remained undistinguished as there were no brilliancy prizes awarded in either of these contests!’

See too The Best Chess Games.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.