Edward Winter

Akiba Rubinstein

From John Nunn (Chertsey, England):

‘I recently received a pre-publication copy of White King and Red Queen by Daniel Johnson. In it I read (page 11) that “Rubinstein’s sanity, always precarious, gradually left him and he spent his last 30 years in a sanatorium”. A similar claim was made in another recent book, The Immortal Game by David Shenk, which stated (page 143) that “... [Rubinstein] spent the last 30 years of his life in a mental institution”. I was surprised both by these claims and the similarity between them (the precise 30-year figure).

I may be mistaken, but I had the impression that while Rubinstein may have suffered bouts of mental illness, he had regular contact with other players in the post-War years. Do you know of any evidence that might support the claims of Johnson and Shenk or is this just a myth?’

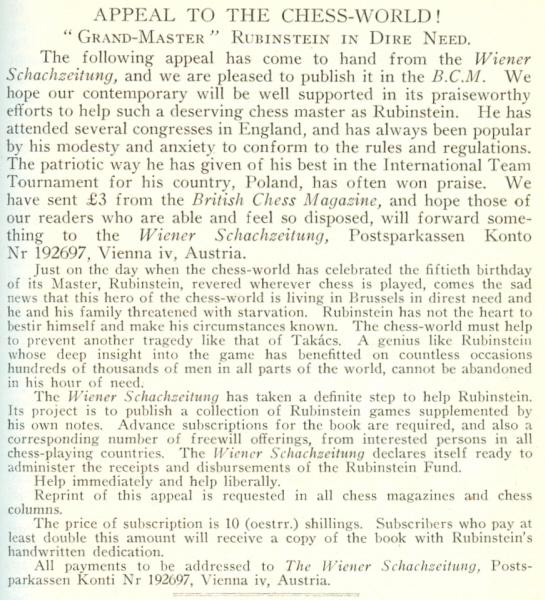

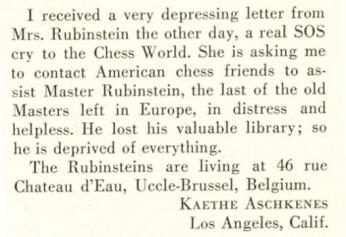

We propose to deal with the matter in some detail. Firstly, it will be recalled that Akiba Rubinstein’s serious chess career ended in the early 1930s, at which time his personal circumstances became desperate. The text below appeared on page 111 of the March 1933 BCM:

Here is Rubinstein’s inscription in one of our copies of the book subsequently published, Rubinstein Gewinnt! by Hans Kmoch (Vienna, 1933):

The remainder of his life, nearly three decades, was so tragic and obscure that chess writers have had a field day light-mindedly filling in the gaps. From page 148 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992):

‘The rest of the story is sadder. He had settled in Belgium and, after 1932, talked to no-one but his immediate family. When his wife died, conversation grew even more sparse. He stopped bathing and let his hair and beard grow without shaving or clipping. The Nazis came in 1940 and asked this wild-haired Jew if he was willing to work for the Third Reich. He said yes, and this frightened them. Even an SS ape was still able to feel awe and fear in the presence of a man divinely or hellishly mad. For 30 years he lived in a silent and unwashed purgatory until his death in 1961.’

No sources were provided for any of that, of course, but it seems that Fauber was decorating an article about Rubinstein by Hans Kmoch on pages 176-177 of the June 1961 Chess Review. After relating his failure to secure Rubinstein’s participation at Bled, 1931, Kmoch wrote:

‘Nor was this writer more successful five years later when he made the trip from Amsterdam to Brussels in order to invite Rubinstein to a tournament in Holland. This last meeting with the grandmaster (as it proved to be) was but brief. For Mrs Rubinstein warned beforehand: if a visitor doesn’t leave soon, Rubinstein himself might leave, possibly through the window.

Another World War broke out, and Rubinstein, although now living at the other end of Europe, came again under German occupation, this time a much more dangerous one. But, miraculously, he survived, even without any extra effort. When they came to fetch him and asked whether he was willing to work for Germany, he simply said yes, and that seems to have frightened them. At any rate, they withdrew and left him alone for the rest of the War. It happened in Belgium, after all, where the Germans, as in Denmark, showed some restraint in return for the King’s capitulation.

A few years ago, Mrs Rubinstein passed away; and, with her, Rubinstein died his second death. He would no longer wash, shave, have his hair cut, change his clothes nor speak a word. He stayed on only as a living corpse, until recently the corpse also demised.’

Kmoch, whose account indicated that his last personal meeting with Rubinstein was in 1936, did not specify the provenance of the details concerning the remainder of Rubinstein’s life.

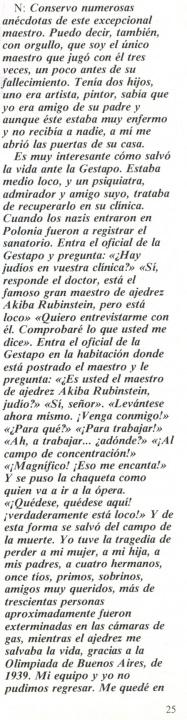

As regards the story about Rubinstein being invited ‘to work for Germany’, we wonder whether the article in the 1961 Chess Review was its first appearance in print. Subsequently, M. Najdorf related it with particular relish. For example, C.N. 1660 referred to his statements on page 25 of the June 1988 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez, in an interview with Eduardo Scala:

In short, after asserting that he was an exception in being allowed into the Rubinsteins’ home Najdorf said that after the Nazis invaded Poland Rubinstein expressed delight when invited to work in a concentration camp. The Gestapo thus concluded that Rubinstein was truly insane, and the master avoided going to a death camp. The fact that Rubinstein was in Belgium, not Poland, during the Second World War, apparently passed Najdorf by.

A similar account by him was quoted on page 109 of Najdorf x Najdorf by Liliana Najdorf (Buenos Aires, 1999):

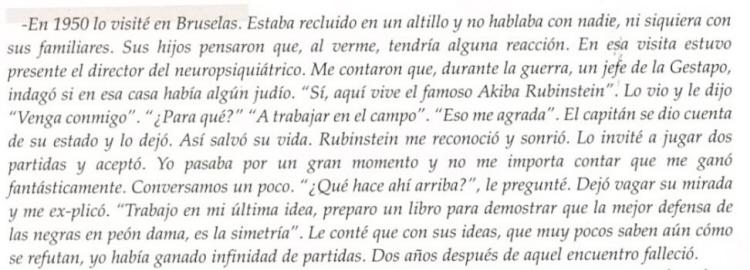

Here, M. Najdorf affirmed that in Brussels in 1950 he visited Rubinstein, who had shut himself away in an attic and spoke to nobody. Also present during the visit were Rubinstein’s sons and the director of a neuropsychiatric institute, and they told Najdorf the Gestapo story. Najdorf added that Rubinstein agreed to play two games with him and that Rubinstein won in fantastic style. Najdorf then asked him what he did in his attic, and received the following reply: ‘I am working on my latest idea; I am preparing a book to demonstrate that the best defence for Black in the Queen’s Pawn Opening is symmetry.’

Najdorf’s narrative ended by stating that two years after this meeting Rubinstein died. Since the visit purportedly took place in 1950 and Rubinstein’s death, in Antwerp, occurred on 15 March 1961, that is just one more example of the kind of discrepancy without which no reportage by Najdorf is complete. On the other hand, the comment on symmetry for Black is a reminder of a reference to Rubinstein on page 122 of the April 1940 BCM:

‘He is living in retirement in Brussels but is still actively concerned with chess analysis, notably with an exploration of the variation 1 P-Q4 P-Q4 2 P-QB4 P-QB4.’

Akiba Rubinstein

Whether Max Euwe, any more than Hans Kmoch, had first-hand knowledge of, or contact with, Rubinstein after the 1930s is not clear to us, but he too related the Nazi story, in an interview with Hans Bouwmeester. Below is the English version (complete with the anecdotalist’s ‘once’) which appeared on page 200 of CHESS, September 1981:

‘He finished his life in a mental asylum in Antwerp. During the war these asylums were sometimes exploited as refuges by resistance workers. Nazi investigators once descended on the place and asked Rubinstein, “Are you happy here?” “Not at all”, Rubinstein replied. “Would you prefer to go to Germany and work for the Wehrmacht?” “I’d be delighted to”, Rubinstein replied. “Then he really must be barmy”, the Nazis decided.’

In passing we also cite a vague claim on page 176 of Max Euwe by Alexander Münninghoff (Alkmaar, 2001):

‘Until long after the war he [Rubinstein] languished in lamentable circumstances in a Belgian institution, and it wasn’t until 1961 that he finally gave up the spirit, which in another sense had long since departed.’

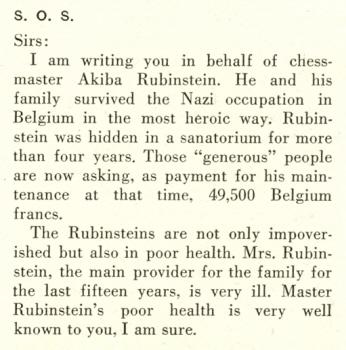

Specific information about the Rubinstein family’s circumstances after the Second World War was provided in a letter from Kaethe Aschkenes on page 1 of Chess Review, March 1948:

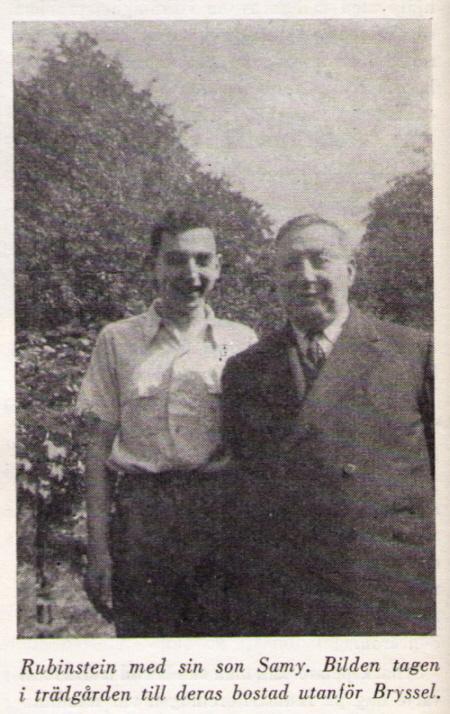

The master’s younger son, Sammy Rubinstein, supplied some details for C.N. in 1985 (see pages 121-122 of Chess Explorations). He was questioned by a correspondent of ours, Karl De Smet (Brussels), who submitted a recording of their exchanges (in French), from which we made a summary. Among the facts provided were the following:

Akiba Rubinstein married in 1917, and his wife (née Lew) bore him two sons, in 1918 (Jonas) and 1927 (Sammy). She died in 1954. The master played in private at home with Yanofsky, Najdorf and O’Kelly. (Pages 119-122 of D.A. Yanofsky’s book Chess the Hard Way! (London, 1953) gave a game he played against Rubinstein at the latter’s home in Brussels in February 1947.)

Our summary of Sammy Rubinstein’s reminiscences concluded:

‘The family lived together (A.K.R.’s wife having opened a restaurant in the early 1930s) until 1942. S.R. spent 1943-44 in the hands of the Germans. After the death of his mother, S.R. suffered a depression and spent three-four years in a psychiatric institute.

At home A.K.R. tended to remain alone in his room, being very uncommunicative. Sammy concludes: “Chess was everything for him, and I don’t believe it is enough to fill a life. You have to do other things as well.”’

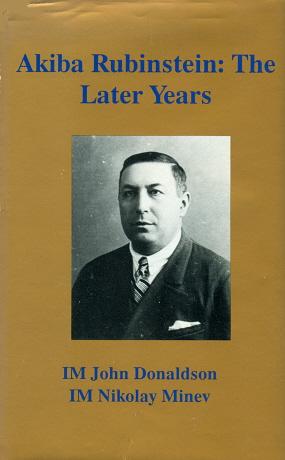

The most detailed examination of Rubinstein’s long final period is in Akiba Rubinstein: The Later Years by J. Donaldson and N. Minev (Seattle, 1995). See, in particular, pages 1-8 and 290-291, which included the following information:

The above biographical information was obtained by John Donaldson during a visit to Jonas Rubinstein and his wife in Charleroi, Belgium in 1995 (as noted on page 290).

On page 3 of their book Donaldson and Minev wrote (prior to demolishing a Koltanowski yarn):

‘Most stories concerning Rubinstein are at best half truths, which have become so embellished over time that they bear little resemblance to what actually transpired.’

That is indisputable. Much about the last 30 years of Rubinstein’s life is unclear or unknown, but it is evident that for most of that period he lived at home, and not in a sanatorium or mental institution.

(5250)

Roland Kensdale (Aberdeen, Scotland) quotes the following passage about Rubinstein from page 168 of Russian Silhouettes by Genna Sosonko (Alkmaar, 2001):

‘His nurse, madame Rubin-Zimmer, remembered: “He was an unusually calm and self-controlled person. He was easy to look after. Physically he was exceptionally strong and very healthy for his age. But from time to time he would behave strangely. For days on end he would not come out of the room for even a short walk. Or sometimes in the evening he would not want to go to bed. Then he would sit in the armchair next to the bed and meditate deeply about something or move the pieces on a pocket chess set.”

We do not know how the lessons went, when the young O’Kelly went to the clinic to visit the famous Maestro. What was Rubinstein thinking of when, in the very last period of his confinement, he would sit for a long time in front of a chess board, with the pieces set up in the initial position, sometimes making the move 1 c2-c4 and, taking the pawn back after half an hour’s thought, again looking at the chess board? What solution to the secret of the initial position did he imagine that he saw?’

Our correspondent notes that Sosonko’s book has no bibliography and does not specify the source of the above information.

(5256)

From Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel):

‘In his book Dykteryjki i ciekawostki szachowe (Warsaw, 1971; second edition, Warsaw, 1974) the Polish chessplayer and author Władyslaw Litmanowicz gave an account of his visit to Akiba Rubinstein in June 1957, at an old people’s home in Brussels (“Maison de retraite pour vieillards – A.S.B.L.”).

He stated that Rubinstein had arrived there two years earlier, after the death of his wife, and lived in a room for eight, sharing with two persons. Though surprised by the unexpected visit, Rubinstein received his guests dressed in a well-tailored suit, with the appearance of an elegant elderly gentleman. He sported a large beard, and invited his visitors to speak in the language of their choice: Polish, Russian, German or French.

Litmanowicz conveyed to Rubinstein the greetings of Kazimierz Makarczyk and Marian Wróbel, and informed him of the recent deaths of Tartakower, Regedziński and Důras. Rubinstein was not aware of Smyslov’s victory over Botvinnik for the world championship and refused to play a game against his guest. He did, however, analyse two studies by Důras with much interest.

After leaving the old people’s home, Litmanowicz was told by C. Rubin-Zimmer, the nurse who devotedly looked after Rubinstein, that he was in very good health considering his age, and was very quiet and restrained, notwithstanding several oddities: sometimes he refused to leave his room, or to go to bed to sleep. In such cases he sat on a chair near his bed, thinking deeply about something, or moving pieces on his pocket chessboard.’

(5301)

Stefan Müllenbruck (Trier, Germany) makes the following points:

a) authoritative sources such as Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia state that Akiba Rubinstein died in Antwerp, Belgium;

b) in an article on page 246 of the journal Menora, 1996 Ernst Strouhal wrote of Rubinstein:

‘Er wurde von seinen Söhnen im jüdischen Altersheim in der Rue de la Glacière untergebracht.’ [‘He was placed by his sons in the Jewish old people’s home in the rue de la Glacière.’]

Strouhal’s source was an interview by Monika Bernold with Rubinstein’s sons, Samy (Sammy) and Jonas in June 1995;

c) a Jewish old people’s home exists, still today, at rue de la Glacière 31-35 in Brussels.

Our correspondent asks how the discrepancy between Antwerp and Brussels is to be explained.

We have consulted Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium), and his reply is given below:

‘I have checked the matter with Akiba Rubinstein’s daughter-in-law. She informs me that the home in the rue de la Glacière was temporarily closed for renovation and that the residents were all transferred to Antwerp.’

(5744)

Page 7 of The Pleasures of Learning Chess by Fairfield W. Hoban (New York, 1974) presents, without any sense of propriety, his variant (nearly 40 lines) of the Rubinstein family’s alleged encounter with the SS during the Second World War. For example:

‘The Nazis looked at each other. The leader spoke. “That’s all irrelevant, madam. Here are the forms for you to complete. Pack your belongings and be ready to leave tomorrow morning at 8.00 a.m.” They turned and stamped down the stairs.’

By the next morning, however, the stamping SS officers had become tender-hearted and munificent, and once again Hoban is in possession of the exact words spoken (or, better say, an English translation thereof):

‘The plans are changed, Frau Rubinstein. You and your son will not be leaving, after all. I have been given orders to issue you these identification papers, ration books, and this sum of Reichmarks. You will not be troubled any further.’

Hoban knows everything except the identity of the ‘unknown guardian, a benefactor whose name never was revealed, but whose memories of happier days and beautiful chess games had been reawakened when he saw the name of a chess immortal – Akiba Rubinstein – on his death list.’

(6677)

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) draws attention to a passage on page 123 of Histoire des maîtres belges by M. Wasnair and M. Jadoul (1988):

‘Après la guerre, O’Kelly et Devos rendaient régulièrement visite à Akiba Rubinstein qui avait élu domicile à Bruxelles. Malade, absent, les yeux éteints, le grand A. Rubinstein reprenait vie devant l’échiquier. Comme le contait Devos, “ses yeux s’allumaient sitôt l’échiquier installé”. Rubinstein et O’Kelly ont joué ensemble des dizaines de parties sur le même thème: 1 é4 é5 2 Cf3 Cc6 3 Fb5 Fç5 (le système Cordel de la partie Espagnole). L’étude approfondie de cette variante où O’Kelly conduisait toujours les noirs, deviendra l’une de ses armes favorites. L’enseignement des parties jouées avec A. Rubinstein, mais surtout son travail personnel, permettront à O’Kelly de passer du niveau de bon maître national à celui de maître international et enfin à celui de grand maître.’

Did either O’Kelly or Devos write any articles about their meetings with Rubinstein?

(6710)

This sketch of A. Rubinstein by his son Sammy is reproduced courtesy of John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA). It appears on page 380 of the 2011 monograph which he co-wrote with N. Minev (C.N. 7572).

Mr Donaldson comments to us that the latest photograph of Rubinstein known to him was published on page 124 of the June 1949 issue of Tidskrift för Schack. We are grateful to Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) for the scan below:

(7584)

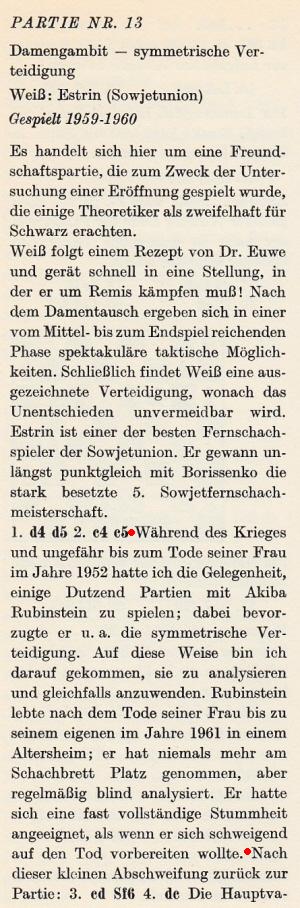

Timothy J. Bogan, (Chicago, IL, USA) draws attention to a passage by O’Kelly on page 32 of 34 mal Schachlogik:

To summarize: During the Second World War and until Rubinstein’s wife died, O’Kelly played several dozen games against Rubinstein, some of which featured the ‘Symmetrical Defence’ to the Queen’s Gambit, an opening which O’Kelly then analysed and played himself. As a widower, Rubinstein spent his final years in an old people’s home, no longer using a chess set but regularly analysing without a board. He remained almost silent, as if wishing to prepare himself for death.

See also:

Akiba

Rubinstein Miscellanea

The

Rubinstein Trap.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.