Edward Winter

W. Steinitz

Source: Chess Monthly, January 1886, pages 136-137.

Regarding the 9-9 clause, below is the text of C.N. 3324 (see pages 134-135 of Chess Facts and Fables and our feature article on Zukertort).

From page 65 of part one of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors (London, 2003), concerning the 1886 world championship match (ten games up) between Steinitz and Zukertort:

‘There was an important nuance: with a score of 9-9 the match would be considered to have ended in a draw, since the players did not want the outcome of such an important duel to rest on the result of one game. Such a rule was to apply later in a number of unlimited matches for the world championship, and it became a stumbling-block in the years when Fischer was champion (as will be described in a later volume).’

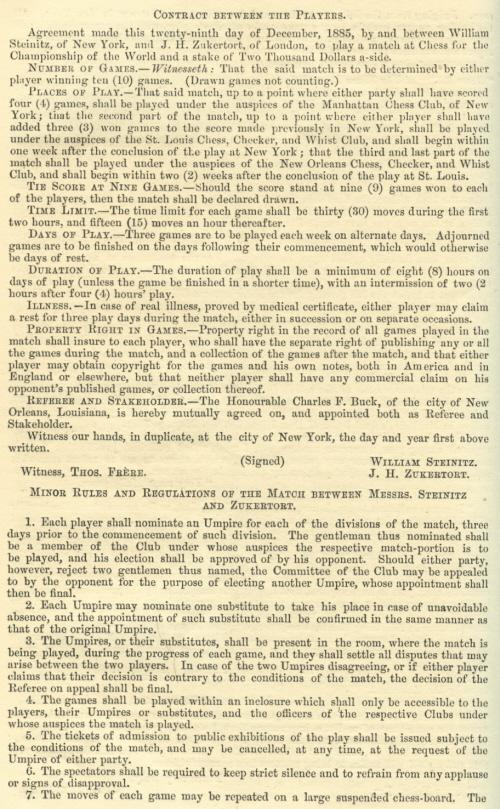

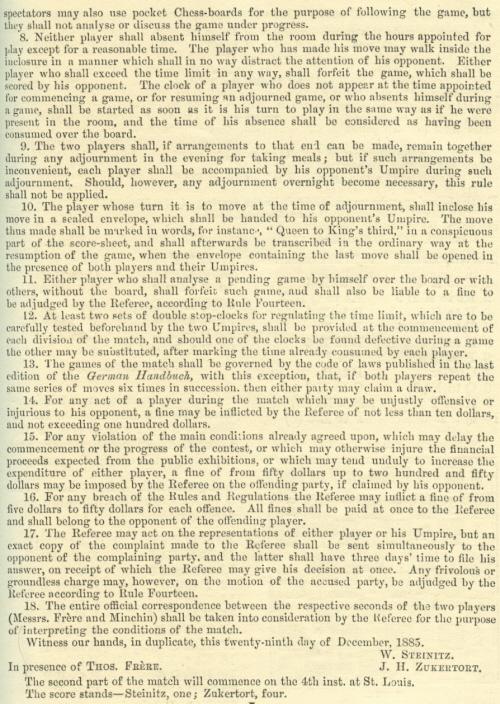

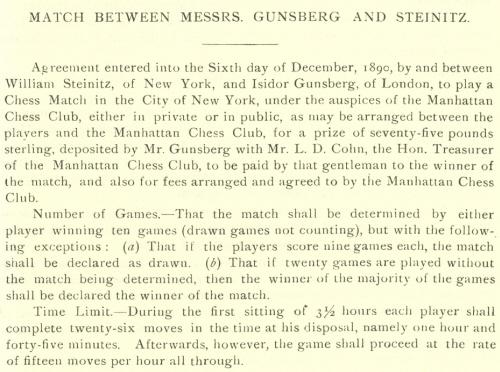

It is indeed true that Steinitz and Zukertort’s contract (29 December 1885) stipulated:

‘The Score at Nine Games. Should the score stand at nine (9) games won to each of the players, then the match shall be declared drawn.’

Source: Chess Monthly, January 1886, pages 136-137.

However, on page 118 of the May 1886 International Chess Magazine Steinitz reported that this provision had been amended before the final series of games began in New Orleans on 26 February 1886:

‘Two of the conditions of the match [one of them omitted here, being a minor matter concerning playing hours] were altered by mutual consent of the players, who had agreed, in the first place, to reduce the score, which rendered the match a draw, to eight all, instead of nine all, as previously stipulated. There can be no doubt that both the principals acted bona fide and chiefly in the interest of their backers in agreeing to such a modification of the original terms of the match, for their main reason in adopting the alteration was to exclude all element of chance as much as possible and to avoid risking the issues at stake on the result of two games. But, on consideration and in order not to establish a questionable precedent, we feel bound to say that the opinions of some critics, who, without in the least impugning the motives of the two principals, have expressed doubts on the legality of such proceeding, now appear to us reasonable. For it is justly contended that the two players had no right to alter any of the main conditions of the match without consulting their backers, who had deposited their stakes after the chief terms had apparently been finally settled …’

Source: International Chess Magazine, December 1888, pages 355-356.

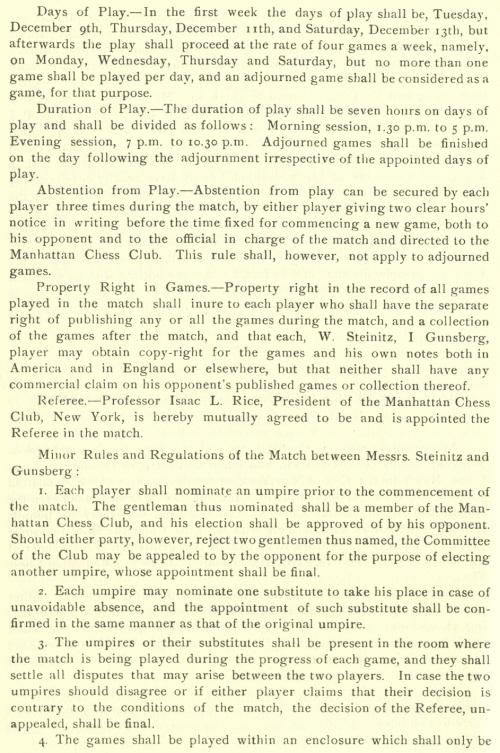

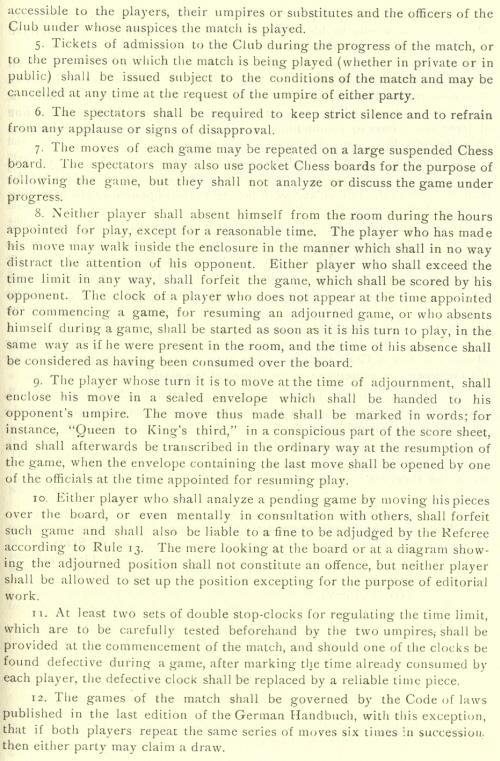

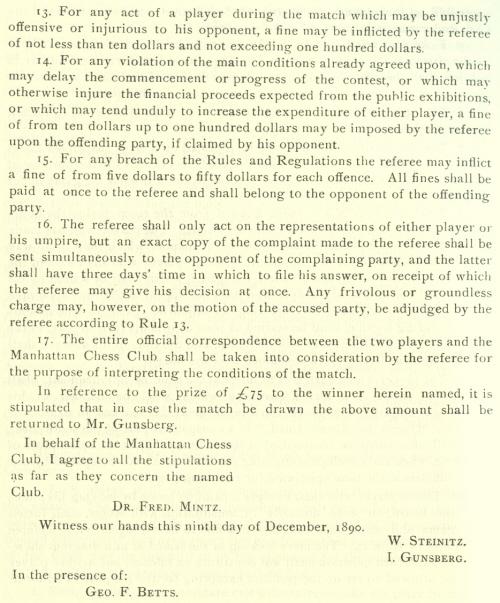

Source: International Chess Magazine, November 1890, pages 325-328.

Source: International Chess Magazine, July 1891, pages 200-201.

Source: BCM, April 1894, pages 162-163. A signed original (ten pages) of the above-mentioned agreement is owned by David DeLucia, who reproduced the first two pages in the books discussed in C.N.s 3164 and 5323.

Page 425 of the November 1896 BCM stated that the return match between Lasker and Steinitz would take place ‘under the same conditions as those of the first match, with the exception of the stake’. On page 468 of the December 1896 issue a summary of the match rules was provided: ‘it will be decided by ten won games, draws not being counted. The time-limit is 15 moves an hour. A purse of £200 will be presented by the Moscow Club to the winner, and £100 to the loser.’

The date when Steinitz became world champion is not a matter of consensus among chess historians (or, indeed, among non-historian broad sweepists). Below is a chronological list of relevant citations that we have found so far in contemporary magazines.

1866 (Steinitz defeated Anderssen +8 –6 =0 in London). No use of any term such as ‘world championship match’ has been located.

1872 (Steinitz defeated Zukertort +7 –1 =4 in London). From page 150 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, October 1872:

‘The one-sided character of the play must be attributed (as the Westminster Papers have pointed out) to the ill-health of Mr Zukertort; but this does not detract from the well-earned laurels of Mr Steinitz, who may now be fairly pronounced the champion player of the time.’

1876 (Steinitz defeated Blackburne +7 –0 =0 in London). From Alphonse Delannoy’s article/report on page 100 of La Stratégie, 15 April 1876:

‘Aujourd’hui que ce charmant Morphy a abandonné les échecs, il faut considérer M. Steinitz comme le roi de l’Echiquier moderne, et nous nous inclinons, tout éblouis, devant son éclatant triomphe.’

1881-82 (Challenge issued by Steinitz). As a result of an analytical argument between Steinitz and Zukertort, the former issued a match challenge. Below is the report in the 18 January 1882 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (as quoted in the Cincinnati Commercial of 18 February 1882), which includes a reference to ‘Mr Steinitz’s claim to be recognized as the champion of the world’:

‘We are enabled to announce that Mr Steinitz will challenge the co-editors of the Chess Monthly (Messrs Hoffer and Zukertort) to a chess match of 11 games up.

Conditions

The stake to be not less than £100, nor more than £250.

Two games to be played each week.

Time-limit – 15 moves per hour.Mr Steinitz will offer his joint opponents the odds of two games out of the 11; or, should they deem such an offer unacceptable, he will play them level, or even accept the odds of two games from them.

The above announcement will undoubtedly cause a sensation in the chess world. Mr Steinitz has adopted the best, and we are glad to say also the most interesting, course, to endeavour to prove to the joint editors of the Chess Monthly that they have, without justification, attacked and questioned his judgment in chess matters generally, and analysis in particular.

Mr Steinitz’s claim to be recognized as the champion of the world is based on the fact of his having defeated the three great chess masters of the age – Anderssen, Blackburne and Zukertort – who, apart from Mr Steinitz himself, occupied the foremost position in the chess world since the time of Morphy. Mr Steinitz also won the first prize at the London tourney of 1872, and the Vienna tourney of 1873.

The offer to play the prize-winner of the Paris tourney of 1878 and the victor of Blackburne in a set match of 11 games, allowing him to consult with another strong player, is unquestionably a bold one, but when taken in connection with Mr Steinitz’s offer to concede two games out of 11, we cannot withhold our surprise and admiration. Such an undertaking on the part of Mr Steinitz will, we think, call forth, even from men whose knowledge of the players and judgment of chess entitle their opinion to some weight, doubts as to whether the Herculean powers of Mr Steinitz will be equal to the successful accomplishment of the task. He has, however, our best wishes for the success of his bold and spirited enterprise.’

Concerning the refusal of Zukertort/Hoffer to accept the challenge, see the Chess Monthly, February 1882 (pages 161-162), March 1882 (pages 193-194) and April 1882 (pages 225-226).

1883 (London tournament, won by Zukertort, three points ahead of Steinitz). No apposite quotations traced so far.

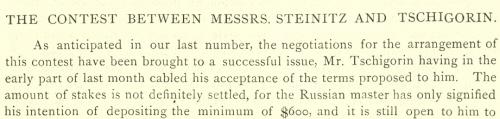

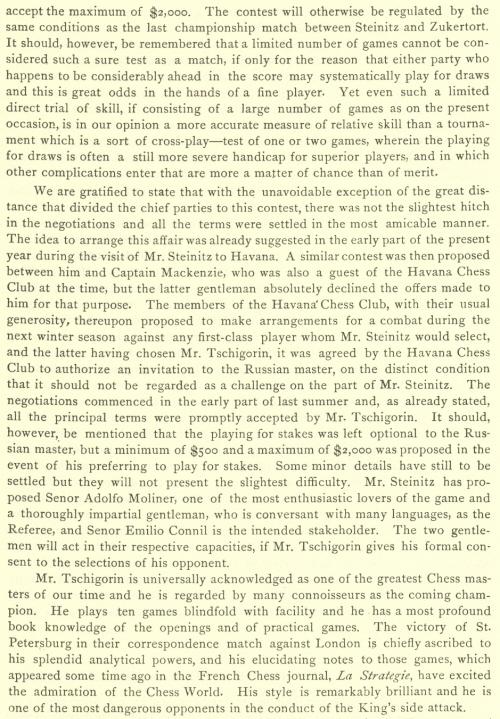

1886 (Steinitz defeated Zukertort +10 –5 =5 in New York, Saint Louis and New Orleans). In January 1885 Steinitz had begun publication of his International Chess Magazine, which contained much documentary material about the protracted match negotiations. At first the references were merely to the ‘championship’ or ‘the champion title’, without ‘world’. For example, on page 38 of the February 1885 issue Steinitz reported that in Turf, Field and Farm of 8 February 1884 [sic] he had published a challenge …

‘… to the effect that he was willing to play Mr Zukertort in New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans or Havana, or any other place this side of the Atlantic, for the champion title only, without any other stake or prize, and without charging any fee for expenses, while Mr Zukertort would be at liberty to make any terms he chose with any society which would arrange the contest. As the Globe-Democrat of St Louis subsequently remarked, Mr Steinitz offered to make the match a benefit performance, solely for Mr Zukertort’s pecuniary profit.’ [Italicized emphasis as in the original.]

On page 353 of the December 1885 issue of his magazine Steinitz wrote:

‘The two players will soon enter on their heavy trial for the coveted championship of the world …’

The first sentence of the contract between the two players (the Chess Monthly, January 1886, pages 136-137) specified that the match was ‘for the Championship of the World’.

1887 (Steinitz quote). From page 265 of the International Chess Magazine, September 1887:

‘Of course, such literary trickeries are nothing new to me, and I have been used to it for 20 years that according to the constructions in certain journalistic quarters everybody in turn was the champion during that period, excepting myself. The only consolation I had was that most of the defeats I suffered occurred in my own absence.’

1888 (Steinitz quote). On page 86 of the International Chess Magazine, April 1888 Steinitz asserted ‘for once’ that he had been world chess champion since 1866:

‘And I mean to devote to the task [i.e. exposing the alleged dishonesty of James Séguin], if necessary, the space of this column for the next 12 months, or for as many years, in case of further literary highway robberies perpetrated by the same individual, and provided that I and this journal survive, in order to statuate for all times, or as long as chess shall live, an example that the only true champion of the world for the last 22 years (I may say so for once), who has always defended his chess prestige against all-comers, has also a true regard for true public opinion, and that he can defy single-handed all the lying manufactories of press combinations to show any real stain on his honor; and that he can convict and severely punish any foul-mouthed editor who, like the shystering journalistic advocate of New Orleans, attempts to rob him of his good name outside of the chess board.’

1894 (Steinitz’s career summarized). Page 163 of the April 1894 BCM stated:

‘Wm. Steinitz, who is in his 58th year (he was born 17 May 1836), has held the chess championship of the world for 28 years, having won it by his defeat of Anderssen in 1866. During these 28 years his career has been one of continuous triumph …’

1908 (Lasker’s view). From an autobiographical article in Lasker’s Chess Magazine, May 1908 (page 1):

‘The last tournament held there [in England] was in 1899. The continent has had more than a dozen meanwhile. England has not been the playing ground of a match for the championship of the world since Steinitz beat Anderssen, in 1866.’

On this last quote we add a brief comment. The inescapable implication of Lasker’s references to England and to 1866 is that he considered a) that Steinitz’s matches against Zukertort (1872) and Blackburne (1876), both of which took place in London, were not for the world title and b) that, consequently, Steinitz held the world title for 20 years (i.e. 1866-86) without defending it at all. It is hard to imagine, though, that this was the meaning that Lasker intended to convey.

We shall naturally welcome further contemporary citations, whether for or against the view that Steinitz held the world title for 28 years.

(3325)

Bartlomiej Macieja (Lasek, Poland) refers to the feature articles Early Uses of ‘World Chess Champion’and World Chess Championship Rules and draws attention to a further text, published a few days before the first Steinitz v Lasker match began. Page 24 of the New York Times, 11 March 1894 stated:

‘For 26 years the veteran has successfully defended the championship of the world.’

Also:

‘If a man who has held the world’s championship for 26 years accepts a challenge for a match which promises to him less remuneration than matches he contested before, he deserves some praise.’

The illustrated article was also published, with due credit, on page 3 of the Montreal Daily Witness, 13 March 1894.

Nineteenth-century references to the duration of Steinitz’s tenure are always welcome, regardless of the view adopted.

(12082)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.