Edward Winter

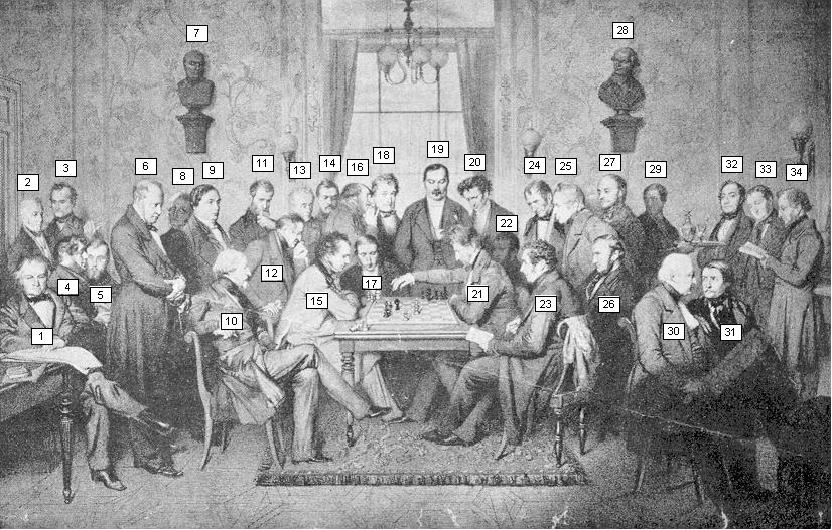

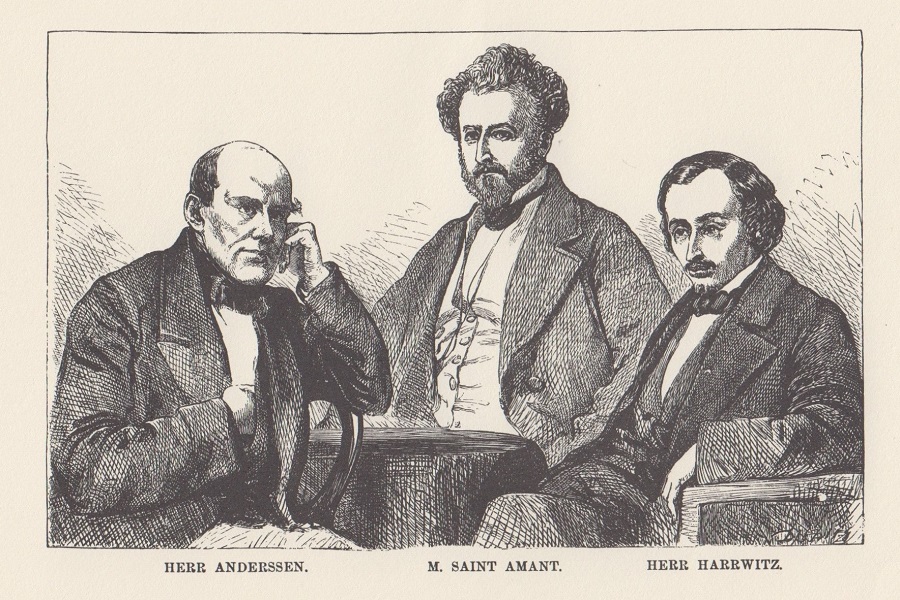

Le Palamède, 15 July 1842 (frontispiece). See C.N. 12073 below.

From page 453 of the November 1933 BCM, in the course of a two-part article on Saint-Amant by G.H. Diggle:

‘In Bell’s Life, 13 February 1853, Walker speaks of St Amant “at Hyères on the Mediterranean shore, engaged in literary labours respecting his late voyage to California”. From 1853-56 he wrote several books on the French Colonies which according to the Westminster Papers for December 1872 “were standard works on the subject”. In 1854 he also wrote a treatise on Les Vins de Bordeaux.’

In a footnote on the same page Diggle added:

‘The writer has ransacked France in vain for copies of these books. One was entitled La Guyane Française et ses mines d’or. Mr Adrian Horton of San Francisco informs me that another of St Amant’s books, Voyages en Californie et dans L’Oregon (Paris, 1854), is in the San Francisco Public Library. It contains 651 pages and is illustrated.’

Further information on any of these books will be welcomed.

(4264)

Dan Scoones (Victoria, BC, Canada) reports that Saint-Amant’s book La Guyane Française et ses mines d’or can be read online through the Google Books Library Project website.

(4270)

From page 383 of the first volume of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (1841), a quote from Staunton which is of particular interest in view of his subsequent difficulties with Morphy:

‘Chess is unquestionably the finest game known; but still it is only a game; and one can entertain but a sorry opinion of his intellect, who makes it, or any amusement, the business of his existence.’

(596)

Addition on 28 August 2023:

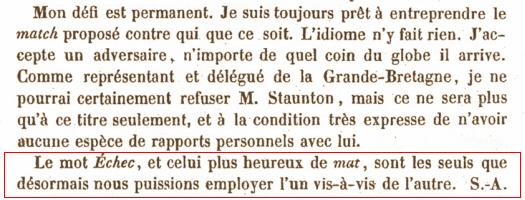

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) quotes the words used by Saint-Amant about Staunton when writing about their first match in May 1843, on pages 203-204 of Le Palamède, 1843:

‘… j’attaque un homme qui, comme Labourdonnais, n’a pas d’autre occupation, d’autre sol à défricher que celui de l’échiquier; qui, de la tête aux pieds, est tout échec; qui y travaillait hier, qui y a rêvé cette nuit, et qui demain, après demain, n’a d’autre spécialité que celle-là. Moi, au contraire, je me partage; des occupations commerciales sont le sérieux de mon temps; les Échecs sont mon plaisir, mes distractions. Dans quelles conditions d’infériorité ne me présentais-je pas au combat!’

Our correspondent comments:

‘You will see that he finds in Staunton characteristics similar to those which had been deplored by Staunton himself some 20 months earlier in C.N. 596. Saint-Amant may have exaggerated a little in order to magnify his achievement in winning the match. I previously used this quotation on page 77 of my book, Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.

Later, Alphonse Delannoy made similar criticisms of Staunton at the time of the Paris match (Le Palamède 1843, pages 543-544), to which George Walker replied, pointing out that “his [Staunton’s] time is equally filled up with business matters as that of St. A.” (Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1845, page 93). However, Walker did not mention what “business matters” he was alluding to; he may have meant his work on the Chess Player’s Chronicle.’

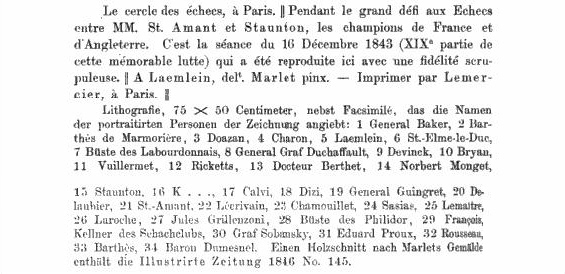

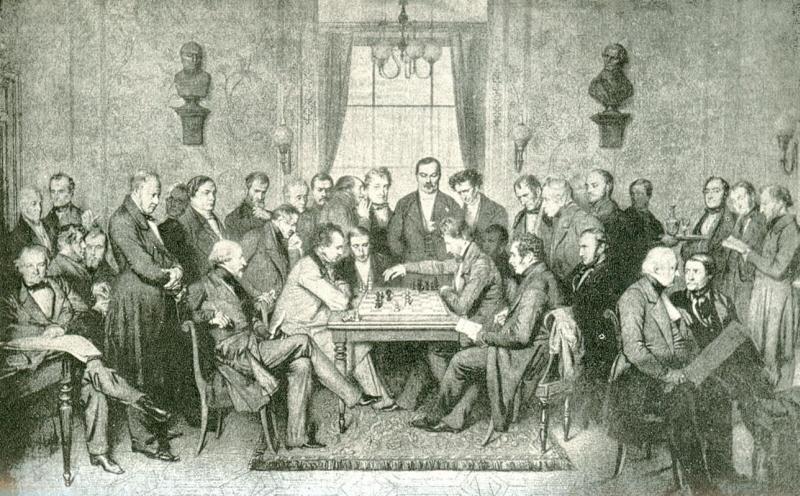

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) raises the subject of the 1843 illustration of Staunton v Saint-Amant, which has been widely published (e.g. as a supplement to the November 1911 issue of La Stratégie). Noting that a key was given on pages 325-326 of volume two of Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels by A. van der Linde (Berlin, 1874), our correspondent has added numbers in the reproduction below:

Mr Gnandt comments:

‘At least two of the figures are inconsistent with the key: “General Graf Duchaffault” (8) appears to the left of the “Büste des Labourdonnais” (7) while “Delaubier” (20) is clearly to the right of “St.-Amant” (21). These inconsistencies make me wonder about the correctness of the key as a whole. Can anyone confirm the identities of all the figures?’

We add that when the picture was given as the frontispiece to the February 1899 BCM ‘J.A.L.’ wrote on page 49 of that issue:

‘The original painting, after which the engraving was produced, is by Marlet, and in connection with it it is curious to note that its publication by the Palamède led to a lawsuit, in which St Amant was involved in his capacity of editor of that celebrated chess periodical. It appears that St Amant bought the painting of the artist for 500 francs, and handed it over to the engraver, Laemlein. The latter did not engrave from the original, but in the first instance made a copy of the painting, in which he substituted several well-known characters in the chess world for some of the persons in the original. As a consequence of these alterations, St Amant considered he was dealing with a fresh picture, and on publication he therefore only suffixed the name of the engraver. Thereupon Marlet brought an action against the Palamède for publishing his picture without his consent, and likewise for damages for the omission of his name. The first part of the action was dismissed, as it was held that the artist, in selling his picture, ceded all his rights to the purchaser. For the omission of his name he was awarded 200 francs damages, and St Amant was ordered to have Marlet’s name added to all future copies.’

(4259)

Etienne Cornil (Brussels) has made available online a 420-page document tracing every Belgian championship from 1901 to 2007.

Reverting to his Cahier on the Café de la Régence (referred to in C.N. 5241 and available through the above link to the Cercle Royal des Echecs de Bruxelles), Mr Cornil also mentions to us that pages 33-39 discuss the Staunton v Saint-Amant picture and offer a slightly different key from the one proposed by a correspondent in C.N. 4259.

(5395)

The following account by G.H. Diggle originally appeared in Newsflash, August 1980 and was republished on page 60 of Diggle’s book Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess History contains many shadowy episodes on which only an uncertain light has been shed, chiefly because the sources of information lie in musty volumes now so rare that only eccentrics know where to find them. The six games played in London in May 1843 between Staunton and Saint-Amant (six months before their Great Match in Paris) are a case in point. The scores were all preserved and the result (St A. 3, S. 2, Drawn 1) is not disputed – but did the games constitute a set match, or were they, as Murray claims, “six informal games which the Frenchman afterwards magnified into a chess match”?

Staunton (Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1843) published the games, but said nothing about a match, and informed his readers that “they were of inferior quality, affording nothing like a test of the relative skill of the two players”, that “he had entered the arena for the first time after severe indisposition”, that he ought to have won the second game “without difficulty” and the fifth “easily”, and that in the sixth game “the timidity, so foreign to Mr S.’s usual style of play, which he exhibits in this contest is undoubtedly attributable to the state of his health”.

But Saint-Amant (Palamède, 1843), though he certainly “went to town” over his victory, is full of praise for the sportsmanship both of his opponent, who was “parfait de courtoisie” throughout, and of “la galerie” at the St George’s Chess Club – “comme beaux joueurs et vrais gentlemen les Anglais très certainement sont nos maîtres”. Moreover, his six-page account fairly established that, though hurriedly arranged and for a nominal stake of one guinea only, it was in fact a match, the winner of the first “trois parties” to be declared the victor, draws not counting. The arrangements at the St George’s, St A. informs us, showed commendable “savoir-vivre” – two “obligeants amateurs” sat recording the moves, and an “honorable assistance” instantly conveyed them to “une nombreuse réunion” who eagerly awaited them with chess sets at the ready in an adjoining apartment.

The first game (Sicilian Defence) was won by Staunton as Black after 69 moves and four hours; the second (Bishop’s Opening) was drawn after 90 moves and six hours, the third and fourth (two Giuoco Pianos of 36 and 30 moves played at one sitting resulted in one game all): the fifth (Sicilian) won by St A. after 60 moves and six hours; and the sixth and deciding game (QP Dutch Defence), won by Saint-Amant after 58 moves (adjourned on 52nd move after 6½ hours – duration of final session not recorded, but Staunton occupied 57 minutes over his 56th move). The games themselves show that Staunton (though scarcely in the debilitated state he says he was) did not reveal the subtle positional strategy that he used with such effect in the later and greater match. The best game of the earlier series is probably the drawn one, a fine struggle which was included by R.N. Coles in Battles-Royal of the Chessboard (1948).’

(4706)

An addition (1844 vintage) to our feature article about Copyright on Chess Games comes from Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘On page 92 of volume V of the Chess Player’s Chronicle Staunton included the following in his “Proposals For Another Great Chess Match” with Saint-Amant:

“I think, also, it would be advisable for the interest of the players that some arrangement should be entered into for the purpose of prohibiting the publication of the games, until the termination of the contest.”

On page 128 Staunton commented that he was ...

“... only anxious to prohibit the printing of the games before the match concludes, that the advantages accruing from their publication may be reaped by the parties best entitled to them.”

He then accused Saint-Amant of having had a private arrangement for publication of games from their first match, to Staunton’s disadvantage.’

(4767)

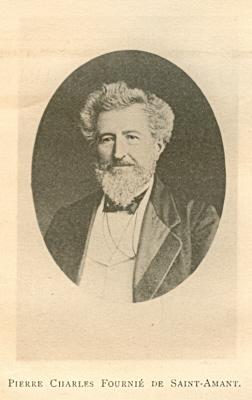

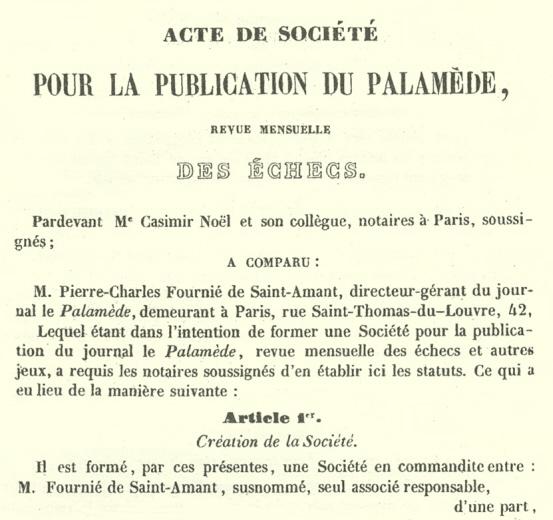

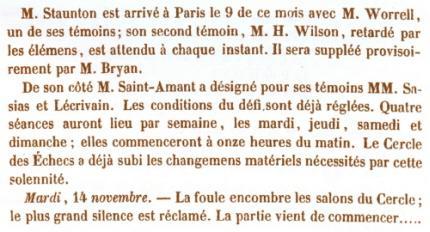

‘Pierre-Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant’ is the most commonly seen version of the master’s full name, but equally respectable sources have ‘Fournié’. For example, whereas ‘Fournier’ was used in his obituary (La Stratégie, 15 December 1872, page 354), ‘Fournié’ appeared in a biographical article by William Wayte on pages 49-50 of the February 1892 BCM (accompanied by the illustration below).

We note now that a particularly weighty source also has ‘Fournié’. Pages 197-204 of the 15 November 1842 issue of Le Palamède, a periodical which Saint-Amant then owned, reproduced a lengthy legal document which referred to him as follows:

‘M. Pierre-Charles Fournié de Saint-Amant, directeur-gérant du journal le Palamède, demeurant à Paris, rue Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, 42.’

(5473)

See also C.N.12073 below.

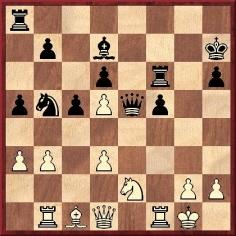

An annotational disagreement occurred between Staunton and Saint-Amant regarding two positions in the 16th game of their match in Paris, played on 11 December 1843.

Here, Staunton played 20 exf5, and Saint-Amant commented on page 66 of the February 1844 issue of Le Palamède:

‘Ceci est un désavantage, car les 2P de la D doublés ne sont plus liés ensemble, et le plus avancé sera peut-être difficile à défendre.’ [‘This is disadvantageous, as the doubled d-pawns are no longer linked together, and the more advanced one will perhaps be difficult to defend.’]

Staunton quoted this in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 April 1844, page 99 and responded:

‘Now we, on the contrary, opine that the taking this pawn increased the advantage in position which White had previously obtained.’

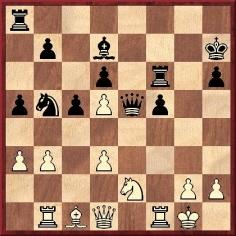

After 20 exf5 the game continued 20...gxf5 21 Nh5 Qe8 22 Nxf6+ Rxf6 23 fxe5 Qxe5.

At this point Saint-Amant commented in Le Palamède:

‘Bien préférable à prendre du P. Les Noirs ont maintenant l’attaque, et leur jeu est supérieur à celui de leur adversaire.’ [‘Much better than taking with the pawn. Black now has the attack, and his game is better than his opponent’s.’]

In the Chess Player’s Chronicle, Staunton disagreed:

‘In the Palamède for February, page 66, note (6), we are gravely told at the present point, “Les Noirs ont maintenant l’attaque (!!), et leur jeu est supérieur à celui de leur adversaire” (!!!). We shall have much pleasure in affording the Editor of Le Palamède an opportunity of verifying this, to us, somewhat startling assertion; and for the purpose, we undertake, on his next visit to London, to play White’s game against him from this move, half-a-dozen times, for as many guineas as he may think proper to risk on the result.’

Saint-Amant reverted to these matters on pages 164-168 of the April 1844 issue of Le Palamède. Concerning 20 exf5 he maintained his standpoint, adding that it was a question of theoretical principle on which most experts would agree with him. (‘Nous ne voyons pas dans les paroles de M. Staunton le moindre motif de rien changer à ce que nous avons dit. Ceci est une question de principe théorique, sur laquelle nous ne craignons pas d’avancer que nous aurons certainement la majorité des connaisseurs de notre côté.’)

As regards the second position, Saint-Amant maintained that Black had the attack, whilst adding that it was a matter of taste:

The two positions entail general positional considerations, rather than specific analysis, and we should like to know how a modern master assesses the respective views of Saint-Amant and Staunton.

The game, which Saint-Amant won at move 58, lasted nine hours (Le Palamède, February 1844, page 66).

(5709)

Regarding the annotational disagreement between Staunton and Saint-Amant arising from the 16th game of their match in Paris in 1843, the first diagram below shows the position after 19...Na7-b5. Play continued 20 exf5 gxf5 21 Nh5 Qe8 22 Nxf6+ Rxf6 23 fxe5 Qxe5, reaching the second diagram.

Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam) writes:

‘After 19...Nb5 I much prefer Black’s position. I consider Staunton’s move 20 exf5 to be dubious because, as Saint-Amant correctly points out, the d5-pawn becomes weak. After 21 Nh5 I would have played 21...Bh8, retaining the two bishops and raising the question of what the white knight is actually doing on h5.

Regarding the second position, I am not sure that Black stands better any more, and he may have frittered away his advantage at this point by failing to keep his two bishops. So is Saint-Amant’s claim that Black has the attack true? After 24 Bb2 Nd4 (if 24...Qe3+ 25 Kh1 Rf7 26 Rf3 and 27 Nf4, I do not see Black’s “attack” at all) 25 Bxd4 cxd4 26 Nf4, and White’s problems are over.’

(5715)

Further to the Tarrasch-Lasker story in C.N. 5707 [‘I have only three words to say to you, check and mate’], we note the following variation on a theme: a passage by Saint-Amant in the course of his bitter public dispute with Staunton. It comes from page 40 of Le Palamède, January 1845:

(5719)

François-Jules Devinck, Wuillermet, Benoît and Delondre –

Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant

Paris, 25 January 1847

Centre Game

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Nxd4 O-O 7 Nc3 Bc5 8 Be3 Ne5 9 Bb3 Nfg4 10 Bf4 d6 11 h3 Nf6 12 Be3 c6 13 f4 Ng6 14 Qd3 a5 15 a4 Nh5 16 Nce2 Qe8 17 g4 Nf6 18 Ng3 b6 19 g5 Nd7 20 Nxc6 Ba6 21 c4

21...d5 (‘Ce coup extraordinaire décide la partie.’) 22 Nd4 dxc4 23 Bxc4 Nde5 24 fxe5 Nxe5 25 Bb5 Nxd3 26 Bxe8 Rfxe8 27 Rf3 Ne5 28 Rf4 Rad8 29 Ndf5 Nd3 30 Bxc5 Nxf4 31 Bxb6 Rd2 32 Bxa5 Nxh3+ 33 Kh1 Rxb2 34 Nxg7 Rc8 35 N7h5 Rcc2 36 Nf6+ Kf8 37 Ng4 Nxg5 38 Rd1

38...Bd3 and White resigned after two or three further moves.

Source: Le Palamède, January 1847, pages 34-35.

(5962)

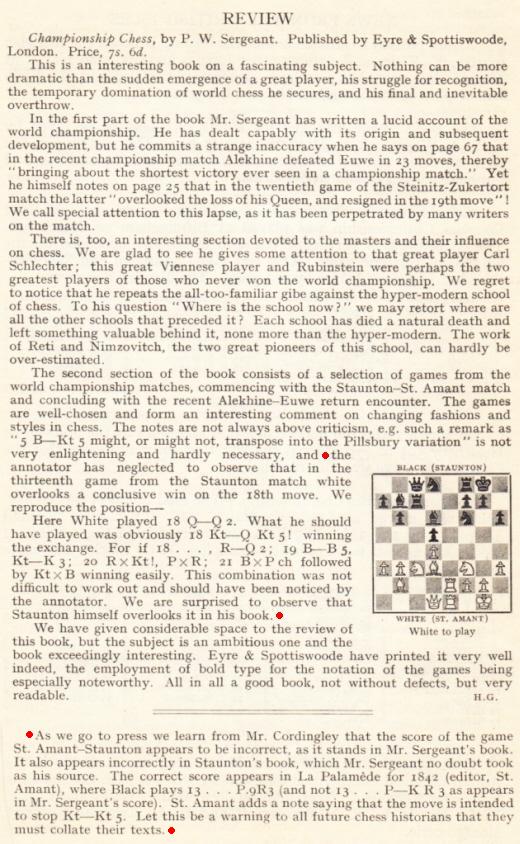

Lynne Leonhardt (Claremont, WA, Australia) is seeking information about her great-great-great-grandfather, John Worrell, who was a second to Staunton in the 1843 match against Saint-Amant in Paris.

We have noted fewer particulars in the Chess Player’s Chronicle than in Le Palamède. From page 481 of the 15 November 1843 issue of the latter:

The agreement between Staunton and Saint-Amant, signed on 13 November 1843, was given on page 563 of the French magazine, 15 December 1843, and the following was published on page 31 of the 15 January 1844 issue:

‘M. Staunton s’est trouvé placé dans des conditions bien défavorables en venant lutter sur une terre étrangère, et se trouvant ensuite abandonné par ses témoins, MM. Worrell et Wilson, qu’une grave et subite maladie a forcés de retourner en Angleterre. Nous devons dire cependant, qu’ayant été dignement remplacés par MM. Bryan et Dizi, leur absence à peine s’est fait sentir.’

(7028)

On the Archives nationales d’outre mer website Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) has discovered the death certificate of Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant. It can be viewed by entering ‘Fournier’ as the surname, with the date 1872.

The document states that Saint-Amant died at three o’clock in the afternoon on 28 October 1872. This contradicts the previously accepted death-date (29 October 1872), which was derived from page 353 of La Stratégie, 15 December 1872.

(7609)

The following article is reproduced from pages 43-44 of our publication Chess Characters, volume two by G.H. Diggle (Geneva, 1987), having originally appeared in the Christmas 1986 issue of Newsflash. Known as the ‘Badmaster’, Diggle, a quintessentially English writer, was aged 84 at the time.

‘The Badmaster, though now retired from chess polemics, has received a kind invitation from the Editor to send Acrimonious Greetings for Christmas 1986. In response to numerous anxious enquiries from pseudonymous admirers (such as In Zugzwang, Three Pawns Down and Just Fools-mated) the BM is pleased to report that, like Captain Corcoran, “he is in reasonable health” and happy to sit reading Newsflash each week and watching the Chess World go (or rather whizz) by with momentous British triumphs and weekend tournaments springing up, in and out of season.

As one of these (Brighton, 1986) landed right on his doorstep, the BM actually tottered down to “The Old Ship” and entered for one of the side-shows. As his last appearance in a South Coast Tournament occurred 47 years ago, it was like leaping a two-generation gap and landing on a new chess planet. The BM had innocently expected to encounter grave adversaries in sober attire who had procured respectable weekend apartments on the Sea Front (Visitors are requested not to play the piano on Sundays, etc.). Instead, half the opposition came roaring in for the day on old bangers and motorcycles – several wore jeans and ate lunches out of rucksacks.

Their style of play, too, the BM found (to quote Boden’s old joke) was “a stile he couldn’t get over”. None of them had ever heard of P-K4, and whenever the BM “occupied the centre” they either crawled around the side of it and mated him in the corner, or undermined it by some system of remote control, picked up no doubt from the latest “Batsford”. Still they were generous victors – “Hope I shall put up as good a fight when I’m your age, sir!” Indeed, all was cheerfulness and Coca Cola. The organizers were as good-humoured as they were efficient, and W.R. Hartston’s “serious lunch-time talk” was punctuated with laughter which would have “excited the admiration” of Terry Wogan.

But, as Sir Robin Day would point out, the topic under discussion is not the BM, but Christmas. Has Britain ever celebrated a great Chess Christmas, one coming immediately on top of a National Chess Triumph? For a collective triumph one has to go back only two years (Salonika, 1984) and even this may soon be “old hat” for as the BM writes this we are already in the lead at Dubai. But for an individual triumph, it seems we must go back to 1843, when on 20 December, after 14 hours’ play, “Mr Staunton achieved his 11th and final victory in Paris”. As London and Paris were still unconnected by rail or telegraph, the news had to come ploughing across The Channel, and reached the Press only two days later. “The Englishman’s victory”, says Murray, “was received with great enthusiasm, and Staunton was fêted on his return”. Yet owing to the unexpected vicissitudes of the course of the match, he only just got home in time for Christmas.

He had been “gloriously successful at the onset” and by 9 December led +10 –3 =2. At this point Staunton’s two seconds, Captain Wilson (indisposed) and Mr Worrell, returned home, “laissant à leur Champion la tâche facile d’achever un ennemi expirant” (Le Palamède). But St Amant, like Karpov in the late great struggle, refused to “expire”. Though one bad move would have cost not only the game but the match, he played with superb accuracy and sang froid through five more games covering 278 moves in all. Staunton’s substitute second and admirer, the American amateur Thomas Jefferson Bryan, was so alarmed that to boost his hero’s morale he collected several English friends in Paris to turn up and “show the flag” at the 21st game. Staunton then pulled himself together and produced (in Ray Keene’s opinion) one of his four greatest games. The match ended in a blaze of goodwill, Staunton being delighted with his victory and his opponent with his great stand at the end – “J’ai sauvé l’honneur”.

On the eve of his departure Staunton invited several leading members of the Paris Chess Club to a farewell soirée at his hotel – “a prior engagement prevented M. St Amant from being present at the dinner, but he arrived immediately afterwards, and participated cordially in the festivities of the evening”.’

(6421)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) forwards this feature from page 416 of the Illustrated London News, 28 December 1844:

(7610)

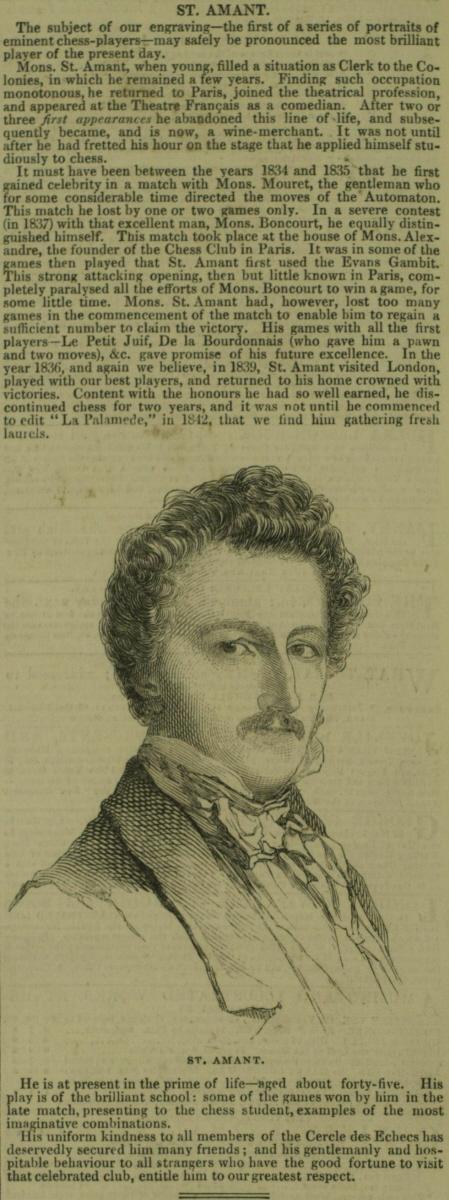

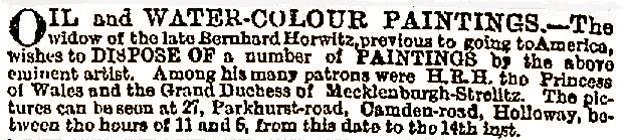

James Pelletier (Costa Mesa, CA, USA) refers to game 13 in the 1843 match in Paris between Saint-Amant and Staunton, which is commonly given in databases as follows:

1 d4 e6 2 c4 d5 3 e3 Nf6 4 Nc3 c5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 a3 Be7 7 Bd3 O-O 8 O-O b6 9 b3 Bb7 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Bb2 cxd4 12 exd4 Bd6 13 Re1

13...a6 14 Rc1 Rc8 15 Rc2 Rc7 16 Rce2 Qc8 17 h3 Nd8 18 Qd2 b5 19 b4 Ne6 20 Bf5 Ne4 21 Nxe4 dxe4 22 d5 exf3 23 Rxe6 Qd8 24 Bf6 gxf6 25 Rxd6 Kg7 26 Rxd8 Rxd8 27 Be4 fxg2 28 Qf4 Rc4 29 Qg4+ Kf8 30 Qh5 Ke7 31 d6+ Kxd6 32 Bxb7 Kc7 33 Bxa6 Rc3 34 Qxb5 Resigns.

However, on pages 65-67 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1844 (volume five) and on pages 350-351 of Staunton’s book The Chess-Player’s Companion (London, 1849) the score was given as 13...h6 14 Rc1 Rc8 15 Rc2 Rc7 16 Rce2 Qc8 17 h3 Nd8 18 Qd2 a6. That would allow Saint-Amant to play Nb5 on or before move 18, and Mr Pelletier therefore wonders whether the actual move-order was 13...a6 and 18...h6.

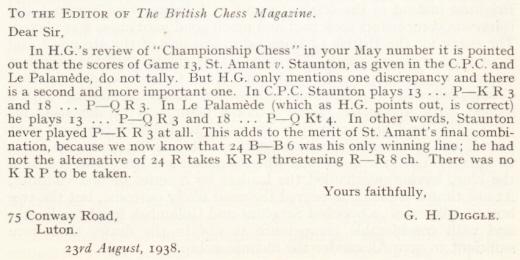

We recall that the matter was discussed in the BCM after publication of Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938). Below is page 205 of the May 1938 BCM:

A response to Golombek’s review from G.H. Diggle was published on page 405 of the September 1938 BCM:

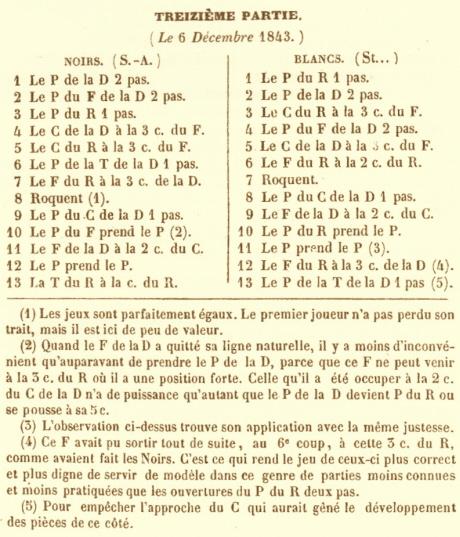

We reproduce below the score as given on pages 23-24 of the January 1844 issue of Le Palamède:

In short, there is every reason to believe that the game-score in Le Palamède is correct. If ...h6 had occurred at some point and ...b5 had not been played, Saint-Amant would have had 33 Qxf7+ instead of 33 Bxa6, since the rook on c4 would be en prise.

(8055)

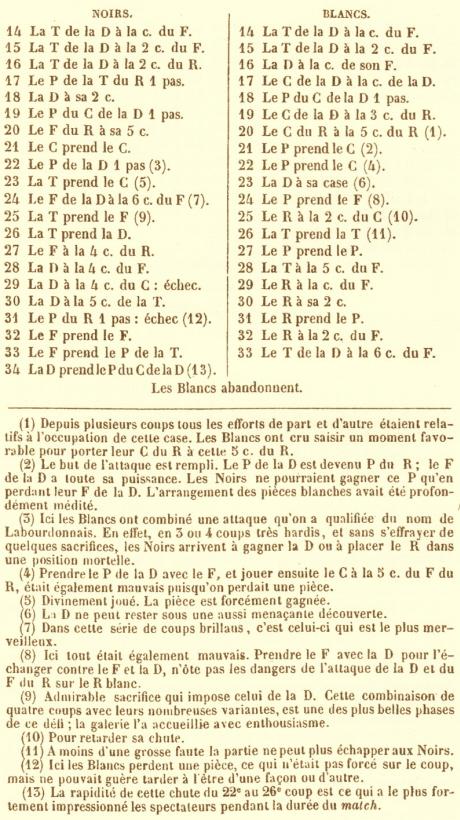

Wanted: information about paintings by Bernhard Horwitz. On page 210 of the May 1846 issue of Le Palamède Saint-Amant wrote:

‘M. Horwitz, peintre allemand distingué, a établi son chevalet au milieu du salon des Echecs, et manie alternativement ses pinceaux et les pièces de l’échiquier. Il lutte de combinaisons avec tous les membres et les immortalise ensuite sur sa toile.’

(8479)

John Townsend has found this item in The Times, 8 June 1886, page 2:

(8487)

26 November 2024:

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) sends the following extract from Le Sport (7 August 1861), page 3, where Saint-Amant was commenting on the 1861 Anderssen v Kolisch match in London.

‘Les parties jouées sont belles sans doute, quoique gâtées souvent par des méprises indignes de si habiles champions. Elles trahissent, en outre, un sentiment d’appréhension mutuelle, une trop grande réserve, si mieux l’on aime. Le Pion du Roi un pas, y joue un rôle fréquent. Nous citons le fait, sans y attacher une pensée de critique, mais simplement d’observation, car nous avons assez préconisé ce début qu’on appelle la partie française, en soutenant, ce qui a pris place dans la théorie des échecs, que ce serait le seul début à adopter si l’on devait jouer aux échecs, non pas seulement sa tête, mais celle de sa femme et de ses enfants.’

Strange to say, we have yet to find a translation machine which conveys Saint-Amant’s final comment correctly, i.e. that the French Defence would be the only opening to play if the survival of one’s close family were at stake.

Dominique Thimognier has been sifting through the contradictory evidence about the name, date of birth and date of death of an eminent nineteenth-century chess figure:

‘Le Palamède, 15 July 1842 (frontispiece)

Pierre Charles Fournié de Saint-Amant came from a noble family in the south west of France. Much of what is known about him is derived from the obituary by Jean Preti in La Stratégie, 15 December 1872, pages 353-355. From page 354:

These lines in the obituary contain no fewer than three errors. Firstly, he was born at Château Latour, not “de Latour”, as was confirmed by the French chess historian Louis Mandy in an article for L’Echiquier de France, April 1956, pages 75-76 after visiting the site:

Nor was he born on 12 September 1800, a mistake repeated in some reference works, including Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (1987). The departmental archives of Lot-et-Garonne provide online access to his birth record (not publishable online without their consent). He was born on 12 Vendémiaire, Year IX of the French Republic. It is likely that Preti erred when converting that date (from the calendar used in France from 1792 to 1805) into the Gregorian calendar; it should be 4 October 1800. The error was noted as early as 1887, as the date 4 October 1800 is in the Biographie Générale de l’Agenais by Jules Andrieu (Paris and Agen, 1887), volume 2, pages 269–270.

See also this Edo page on Saint-Amant.

His name was stated incorrectly in the La Stratégie obituary, given that the birth record states Pierre Charles Fournié Saint Amant:

During the period of the Revolution it would be unthinkable for a civil registrar to include the aristocratic particle “de” on a birth record. However, the spelling “Fournié” is noteworthy.

When Saint-Amant resumed management of Le Palamède he published the “Acte de société” to relaunch the magazine (C.N. 5473). The notarized document also had “Fournié”.

Le Palamède, 15 November 1842, page 197

That spelling was also used in an article about him in the BCM 20 years after his death, on pages 49-50 of the February 1892 issue. (Signed “W.W.”, i.e. William Wayte, the article also erroneously gave his birth-date as 2 September 1800.)

BCM, February 1892, opposite page 49

Below is another article by Louis Mandy, on pages 611-612 of L’Echiquier de France, January 1958:

There has been confusion surrounding Saint-Amant’s death. In 1861, he retired to Algeria, where he had bought the Château d’Hydra on the outskirts of Algiers, in the commune of Birmandreïs (today Bir Mourad Raïs). He died as the result of a fall. The widely accepted date of his death was 29 October 1872, as reported in the French press of the time (e.g. Le Sport, 20 November 1872, pages 2-3) and as also inscribed on his tombstone, noted by Louis Mandy in an article on page 75 of Europe Echecs, April 1961:

The same date, 29 October 1872, appears in Chess Personalia, but, as Hans Renette pointed out in C.N. 7609, the death record of Saint-Amant, available online via the ANOM (Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer), shows a small discrepancy. The record, drafted on 29 October 1872, unequivocally states that Pierre Charles Fournié Saint Amant had died at three o’clock the previous afternoon. The margin of the record confirms the date as 28 October 1872:

The civil registrar spelled his name “Fournier”, and with no hyphen between “Saint” and “Amant”.

During his time as director of Le Palamède (December 1841 to December 1847) Saint-Amant invariably signed each issue as follows: “Le directeur du Palamède, rédacteur en chef. Saint-Amant”. Frequent contributors to the magazine, such as Alphonse Delannoy and George Walker, referred to him simply as “Saint-Amant” or “St-Amant”. Below is one example, from page 9 of the 15 January 1846 issue:

The New York, 1857 tournament book (page 84) includes “Mr Charles St Amant of Paris” among the foreign Honorary Members of the American National Chess Association:

Fiske’s book was not published until 1859, but in his column on page 2 of Le Sport, 30 June 1858 Saint-Amant mentioned receiving documentation from the Association, and he reproduced the same list without any spelling changes to the name “Charles St-Amant”:

That spelling also appeared in Paris newspapers which announced his death (e.g. Le Gaulois, 13 November 1872, page 2, and La Gazette des Etrangers, 14 November 1872, page 1).

To conclude, although there is much confusion over Saint-Amant’s name and the dates of his birth and death, no evidence has been found that he ever used the spelling “Fournier”, or that he included the aristocratic particle “de” except on formal occasions. It would seem that his record should therefore read as follows:

Formal complete name: Pierre Charles Fournié de Saint-Amant;

Commonly used name: Charles Saint-Amant;

Born: 4 October 1800, Château Latour, Montflanquin, France;

Died: 28 October 1872, Château d’Hydra, Birmandreïs, French Algeria (today Bir Mourad Raïs, Algeria).’

(12073)

From a list of references in our feature article on stalemate:

Le Palamède, April 1846, pages 177-181: an article by P.C. Saint-Amant on stalemate/en passant:

‘Peut-on se déclarer pat quand on a encore à jouer?’ Follow-up items on pages 223-225 of the May 1846 issue and on pages 374-379 of the August 1846 issue.

A plate in F.M. Edge’s 1859 monograph on Paul Morphy:

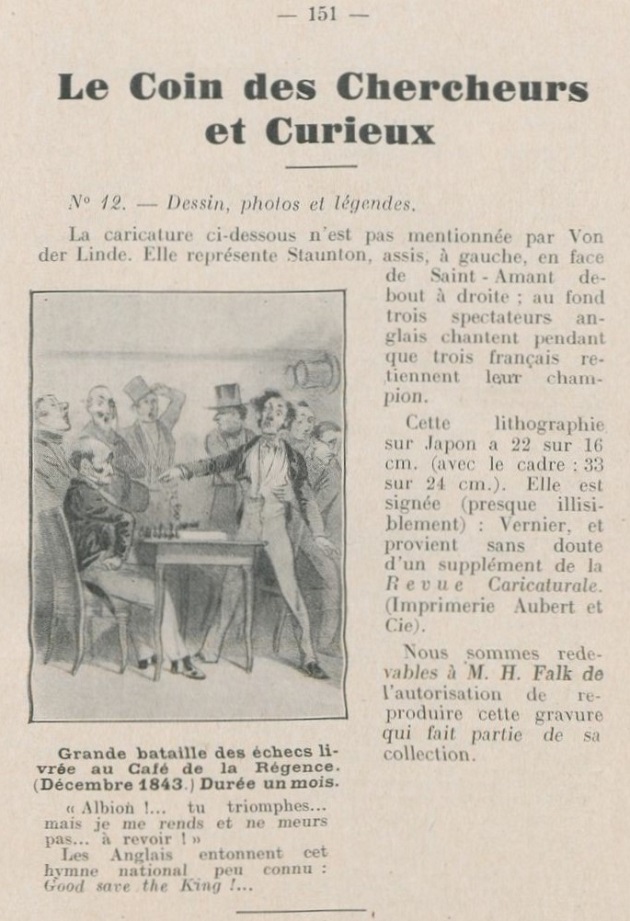

As cited in C.N. 8134, G.H. Diggle’s review of The Kings of Chess by William Hartston noted the inclusion of a cartoon depicting ‘Staunton’s final victory over Saint-Amant, with his supporters singing the National Anthem in the background’.

Dominique Thimognierdraws attention to the cartoon’s appearance on page 151 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 49, September-October 1935:

Our correspondent adds:

‘La Revue Caricaturale published the work of major French caricaturists, including the celebrated Honoré Daumier. The chess cartoon, by Charles Vernier, appeared in the 5 January 1844 edition. It is shown on the Bordeaux website Séléné, although with a notice which appears incorrect regarding the place of first publication (not Bordeaux but Paris).’

(12091)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.