Edward Winter

Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) reports a claim by G.C.A. Oskam on page 39 of Schaakmat, February 1951 that at the 1921 tournament in The Hague Rubinstein began his record of a game on the second row of the score-sheet. According to Oskam, Rubinstein explained himself as follows: ‘There are always players who do not observe the rule of recording every move. They save time by not doing so. In time-pressure they want to profit from my record and look at my score-sheet. They then think that they have only one more move to make, whereas two moves should be made. There is no need for me to help my opponent.’

As already seen in C.N. 4505, Oskam’s stories need to be read guardedly. In any case, we recall only ‘normal’ score-sheets in Rubinstein’s hand. See, for example, page 225 of Akiba Rubinstein: The Later Years by John Donaldson and Nikolay Minev (Seattle, 1995).

(4534)

From Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA):

‘What was the policy during tournaments (prior to the Second World War) concerning the players’ original score-sheets? Was there a general rule or practice whereby they were considered the property of the relevant chess federation, sponsor or tournament committee? Did any notable tournaments have their own particular regulations regarding ownership of score-sheets?’

(5401)

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) quotes from the regulations for Meran, 1924, which stipulated that within an hour of the end of each game both players had to deliver a correct, legible score-sheet, which then became the organizers’ property:

‘12. Spätestens eine Stunde nach Beendigung der Partien haben beide Spieler dem Turnierleiter oder dessen Stellvertreter eine richtige und lesbare Partieaufzeichnung abzuliefern.

13. Die Partien sind Eigentum des Kur- und Verkehrsvereins und des Zentralpropagandakomitees Meran.’

Source: Programmheft des I. Internationalen Schachmeisterturniers Meran 1924, page 14.

(5413)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘On page 17 of the Chicago, 1874 tournament book, rule 11 reads:

“The winner of a game shall furnish a correct copy of such game to the Committee of Management before the commencement of play next day, under penalty of having the game scored against him. In drawn games, the player moving first shall furnish such copy under the same penalty.”

Of course, the reference to “correct copy” does not necessarily imply the original score-sheet, which often contains errors in notation.’

(5423)

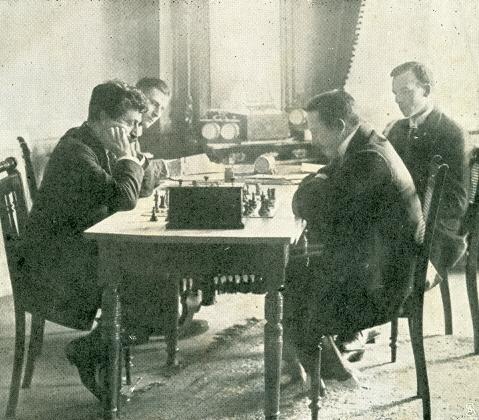

Emanuel Lasker and Siegbert Tarrasch (C.N. 5517), frontispiece to The Championship Match: Lasker v Tarrasch by L. Hoffer (London, 1908)

From Ola Winfridsson (Cambridge, England):

‘To judge from the photograph of Lasker and Tarrasch in C.N. 5517, the players are not keeping score of the game. Instead, that seems to be the task of the two men in the background. When did it become customary for the players themselves to keep score of the game? Was there a difference between tournaments and matches?

(5532)

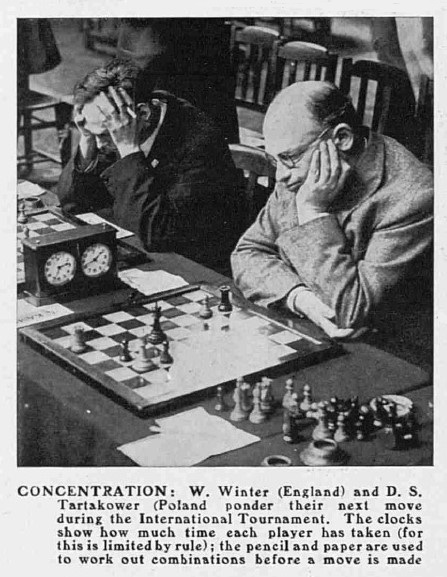

The caption to this photograph from C.N. 6038 prompts us to reproduce two earlier items. C.N. 203 quoted the following from page 176 of the Australasian Chess Review, 20 July 1932:

‘In a recent number of the London Sphere there is a fine photo of two of the players in the London congress seated at the board with clocks and score-sheets alongside them. Underneath is the following priceless description:

“Concentration. W. Winter (England) and Dr S. Tartakower (Poland) ponder their next move during the international tournament. The clocks show how much time each player has taken (for this is limited by rule). The pencil and paper are used to work out combinations before a move is made.”’

C.N. 1004 referred to a paragraph on page 247 of CHESS, August 1940:

‘The London Evening Standard published a picture of Norman Sortier, youngest competitor, in play in the British Boys’ Championship. He was just writing down a move on his pad. The bright caption was, “He used a notebook to help him work out his moves”.’

(6049)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found dozens of rare pictures in The Sphere, 1910-47. They include the following, which was discussed in C.N. 203 (see pages 139-140 of Chess Explorations):

The illustrations discovered by Mr Urcan are presented in our latest feature article, Chess Pictures in The Sphere.

(10291)

From page 91 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘Tartakower had a fluent pen; he wrote voluminously, often annotating a game for a newspaper or magazine while he was playing it.’

Is any further information available about this alleged practice?

(6930)

No information has yet been found on the practice ascribed by Reinfeld to Tartakower (the annotation of games during play). Daniel King (London) asks whether such writing would have been legal in many events of Tartakower’s time.

(6983)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘I witnessed Tartakower making notes during at least one game, at one or more of the Southsea tournaments of 1949, 1950 and 1951, where we both participated. His game against Ravn at Southsea, 1951, which is in his Best Games collection, sticks in my mind.

On one occasion I was curious enough to creep up behind him to see exactly what he was doing. There was a dense sheet of variations and quite small writing, and I think he had some difficulty in reading his own material, pushing his spectacles back on his forehead, screwing up his eyes, and peering closely. I feel fairly sure that nobody objected. He was a legend, and the rules on consulting written material during play were more relaxed then than now.’

(6990)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.