Edward Winter

A.R.B. Thomas came up with the following proposal on page 118 of CHESS, 24 January 1960:

‘I suggest that players in a tournament should be allowed to agree that one take three-quarters of a point and his opponent a quarter. A player is often disinclined to accept a draw but not certain that he can win; the three-quarters of a point might satisfy him and a safe quarter-point might be acceptable to his opponent. Such a result could be quite helpful to an organizer pairing up in a Swiss tournament.’

(3036)

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

‘When did the system of counting draws as a half-point start? On page 8 of Transactions of the British Chess Association, 1866-67 I have found the following passage in the report on the preliminary meeting (3 September 1867) regarding that month’s tournament in Dundee:

“The Grand Tournament comprised ten competitors, each of whom was to contend one game with every other combatant, the prizes to be awarded according to the scores thus made. In order to obviate the difficulty experienced at the recent tournament in Paris, it was decided that a ‘draw’ should be reckoned as half a game to each player engaged in it.”

The tournament results on pages 8-9 gave the scores with the half-points included.

It is difficult to use modern compilations to determine when the “half-point” system began, because modern compilers sometimes present tournament and match scores of that period with the half-points even if the original tables did not use the system. So, which other original sources help to pinpoint the beginning of the half-point system for draws?’

(5605)

Kristo Miettinen (Rochester, NY, USA) asks about the various ways in which draws have been scored in chess tournaments and matches since the mid-nineteenth century:

‘For instance, the phrase “draws do not count” in match play has meant different things at different times; in the first American Chess Congress, at New York in 1857 (to name but one early event) drawn games did not count even for purposes of alternating colors, so that two players who drew played their next game with the same colors as in the draw, until a decisive result was scored. Only after decisive results were colors alternated.

Many descriptions of nineteenth-century tournaments also mention that drawn games had to be replayed, but without indicating whether colors were alternated for the replay.

Other oddities include the Paris, 1900 tournament, in which draws were replayed once only, with alternation of colors, but a second draw stood as the final result.

My interest is in the effect that such rules may have had on opening selection. For instance, rules that required a player with the black pieces to continue playing black until he won (or lost) a game would strongly discourage playing to draw from the outset with Black, regardless of the opponent.’

Do readers know of any systematic treatment of this matter?

It will be recalled that some tournaments deviated from the practice of awarding half a point for a draw. A notable example was Monte Carlo, 1901, and we quote from page 373 of the December 1900 issue of La Stratégie:

‘La première partie nulle comptera pour ¼ à chaque joueur et devra être rejouée; si l’un d’eux gagne la seconde elle lui sera comptée ¾ en tout; si elle est encore nulle chacun aura ½ point. Cette modification pour les nullités a été suggérée par M. le Dr E. Lasker.’

Or, as Jeremy Gaige summarized the system on page 171 of volume two of Chess Tournament Crosstables (Philadelphia, 1971):

‘Initial games, if drawn, counted ¼ and were replayed. If the replayed game was drawn, both players won another ¼. The winner of a replayed game received ½, the loser 0.’

The identical wording turned up on page 6 of Chess Results, 1901-1920 by Gino Di Felice (Jefferson, 2006).

In case of a draw at Monte Carlo, 1901 there was alternation of colours for the second game. See, for instance, A.J. Gillam’s booklet on the tournament (Nottingham, 1995) and, in particular, the discussion of the experimental scoring system on pages 67-70.

(6671)

From Robert John McCrary:

‘In early events the English rule was that a player retained the first move for the next game when a game had been drawn. This did not necessarily mean keeping the same color, as the rule that White moves first was not fully established until later.

That rule was in effect for the McDonnell-Labourdonnais games, because it was “according to the English law” (page 374 of the fourth volume of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1843). Staunton’s The Chess-Player’s Handbook (London, 1847) stated on page 36 that players alternate the first move, except that “If a game be drawn, the player who began it has the first move or [sic] the following one”. This is presumably why the First American Chess Congress (New York, 1857) used this rule, as page 63 of that tournament book stated that the Code in Staunton’s Handbook would govern play, adding on page 64, “Drawn games are not to be counted”.

However, a movement to change this rule was evident as early as 1844. Page 156 of that year’s Chess Player’s Chronicle (volume five) noted that the match between Stanley and Schulten in New York required the first move to alternate even in case of draws. On pages 252-253 of that same volume a correspondent advocated requiring that the first move alternate even in case of draws. Staunton expressed agreement with that change, which he said was already the rule in France and, he believed, throughout the continent. Thus, it seems that Staunton’s publication of the old rule in his Handbook was based on earlier codes, and not necessarily on his own opinion.

On page 188 of the London, 1851 tournament book Staunton said that the players at that event had voted to alternate the first move even in case of draws, although this rule had been forgotten or ignored in one of the games.’

(6676)

In a letter on page 441 of CHESS, 20 August 1955 P.N. Wallis of Quorn referred to ‘dull and unenterprising chess which is prevalent in this country’, adding:

‘The remedy is quite simple. In the British Championship and similar tournaments let a win count 3 points and a draw one to each player, thus putting a premium on the win.’

On page 454 of the 30 September 1955 issue, R.W. Ives of Leeds responded:

‘Mr Wallis raises an old issue. James Mason in 1895 advocated allowances of 1, 0 and minus a half for a win, a draw and a loss respectively, and this seems to me mathematically more logical than the present system. Certainly it seems now that quite a few halves can be picked up in a congress without much thinking. Why should a pre-arranged draw improve either player’s score? The position should be the same as before they started. A player who has lost has a worse record after the game than when it started. Can your readers work it out?’

Writing from Belfast, A.S. Russell commented in CHESS, 15 October 1955:

‘Mr P.N. Wallis proposes that a draw should count only one-third as much as a win. This is intended to penalize the player who adopts stodgy drawing variations. To me it seems that it might have the opposite effect.

Suppose an enterprising player meets a draw-minded opponent, he is faced with a difficult problem. If he ventures on risky play to avoid a draw ... he runs great danger of losing and handing an easy three points to the very type of player Mr Wallis wants to penalize.

The solid player would not now plod along half-way down the table but would bound ahead, aided by bonus points gained against desperate opponents risking too much to avoid the penalizing draw.’

A contribution from C.J.S. Purdy of Sydney was published on page 93 of the 10 December 1955 issue:

‘R.W. Ives (CHESS, 30 September) did not realize that James Mason’s proposal to award 1,0 and minus a half for a win, draw and loss respectively is mathematically exactly the same as P.N. Wallis’s proposal to count a draw as worth one third of a win. This is easily seen if you add a half to every player’s score in every game, irrespective of his result (this cannot affect the positions). You then get 1½, ½, 0; or, eliminating fractions, 3, 1, 0, which is Mr Wallis’s system. Less drastic, of course, would be 5, 2, 0. Mathematically, there is no objection whatever to penalizing draws.

In CHESS of 15 October, A.S. Russell raises an objection which is much less weighty than many players imagine. His objection is that by deliberately playing “stodgy drawing variations” players can induce strong opponents to play wildly and thus lose. The old bogey that it is a great handicap to meet an opponent who plays deliberately for a draw, and that one has to play mad gambits to circumvent him, dies hard. Botvinnik, when three points up against Smyslov, could have won the match easily had there been anything in this theory. It “cuts both ways”. The draw-monger will fail to make the most of his position, and thus give his opponent chances to gain ground, e.g. Capablanca against Lasker at St Petersburg, 1914, where Capablanca played “drawishly” instead of seeking to exploit his two bishops aggressively, and lost. I see no objection to one player trying to draw – only to both players trying to draw. Penalizing draws would certainly eliminate that. Admittedly, many draws are genuine, and it is a drawback that all would be equally penalized. But not as great an evil as arranged draws, which give some players extra rest days. These draws are not merely “drab”. They are cheating.’

W. Heidenfeld of Johannesburg replied on pages 153-154 of CHESS, 11 February 1956:

‘In your “drab draws” correspondence C.J.S. Purdy writes: “Admittedly, many draws are genuine, and it is a drawback that all would be equally penalized. But not as great an evil as arranged draws, which give some players extra rest days.” It is hard to believe that your correspondent is serious in his suggestion that draws of whatever nature should be “penalized”, seeing that chess – like cricket – is a game that allows for a very wide drawing margin; a game that regards players as equal who are merely “approximately equal” and that does not insist that differences of split seconds or fractions of inches in performance are to be rewarded by plus and minus signs. In athletics “draws” are few and far between; in tennis they do not exist at all; and it would have been simple enough to have chess decided on similar lines.

It is clearly illogical not to object to one player trying to draw, but to object to both players trying to draw – if the draw serves the purpose of both. Playing in a tournament, your object is not to win the game – any game – but to win the tournament; and where playing for a win at all cost does not conform to this aim, even the temptation to do so must be firmly resisted. In fact, the ability to resist this temptation is part of a successful player’s technique. Some of the most glorious strokes of cricket may have to remain unplayed – some of the most imaginative games of chess to remain unconceived – because the player has the will to win ... the match or the tournament. In other words, it is exactly the will to win that may dictate to you the necessity of drawing an individual game. Players who do not possess this will to win may indulge their fancy at leisure – but they hardly deserve to get an extra bonus for it.

Leaving aside the special case of the “drab” draw, I believe that masters and annotators have a lot to answer for the [sic] general contempt of “drawn games”. It does not suit their book to annotate such games – because obviously it is far more difficult to assess a good fighting draw correctly than it is to come to definite conclusions regarding the merits of a won and lost game. In the latter, the fact that one side lost is in itself a clear indication of some inferior moves somewhere or another. But in a drawn game – did White stand to win? Did Black? Or was what Lasker called the Remisbreite never exceeded all through the game?

Looking at draws without passion or emotion, one must surely realize that they are the best chess games of all. The best draws must be better games than the best wins – neither side made a mistake sufficiently serious to enable the other, even with best play, to swing the balance in his favour. Yet how many anthologies of famous games have such draws? Games like Alekhine v Réti, Vienna, 1922 or Alekhine v Marshall, New York, 1924? At best very short games of this nature, like the famous draw between Pillsbury and Halprin at Munich, 1900, or the equally famous first encounter between Botvinnik and Alekhine at Nottingham, 1936, are “tolerated”.

If, in such games, the defender had been a little less alert, had lost his way, no matter how slightly, just once, they would rank among the very best specimens of fighting chess. And because the defence was perfect they don’t? Is this the famed chess players’ logic?

I am at present working on the MS of a book “Battle in the balance”, a collection of the finest draws of modern chess, from Hamppe v Meitner, 1872 to Schmid v Castaldi, Venice, 1953. During these 80 years some 50 to 60 practically perfect games of chess were played –and the great majority of them are almost completely unknown.’

The references above to James Mason’s proposal in 1895 concern the extensive correspondence (also involving E.N. Frankenstein and W. Sonneborn) published in the BCM that year and in 1896. However, Mason had made his proposal in a letter (London, 10 December 1892) on pages 40-43 of the January 1893 BCM. On page 42 he wrote:

‘A win should count 1, a draw 0, and a loss minus ½ only, it being in reality no more. It takes two to make a game. What any player loses in losing any particular game is not the whole of that game, but only his own individual half of it, or his chance of winning it. The game counts 1 to the winner; that 1 is made up of twice ½ – his own ½ and his opponent’s ½ – only one of which is, strictly speaking, either won or lost. In fine, the system here proposed is a natural system, and the only one which can be substituted for the present system with advantage to all concerned. It would encourage every player in a tournament to do his best to win, the draw being valueless for scoring purposes.’

(10251)

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) writes:

‘When did the Swiss System obtain its name and when was it invented? The standard reference works mention that it was introduced by Dr Julius Müller of Brugg at the 1895 Swiss Championship in Zurich.

Julius Müller (1857-1917) was a meteorologist and teacher in Brugg (not far from Zurich). He was a founding member of the Swiss Chess Federation in 1889, and a member of the committee and then treasurer until 1903, when he was elected an honorary member. The Swiss pairing system, the official magazine (Schweizerische Schachzeitung) and many other sparkling ideas are credited to him (as noted in his obituary in the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, July 1917, page 103).

The Swiss system was created for the Swiss chess congresses which, starting in 1889 in Zurich, usually packed four or five rounds into two or three days (plus a problem-solving contest, a general assembly and a banquet). As is shown by the tournament regulations (Turnier-Ordnung), during the first few years a prototype of the modern system was used: after each round the field was, according to the results of the previous round, divided into two groups, winners and losers, who were then paired among each other by lot. In case of a draw it was decided by lot who would belong to the “winners” and who to the “losers”. Only at the very end were the points gained added together to ascertain the final ranking. Whether or not attention was paid to equal colour distribution is unknown, and we do not know for sure whether the same two players could be paired against each other more than just once. In the third edition, for instance, two players won with 4/4 in a field of 16; this would not be possible under today’s system because they would have met in the fourth round at the latest.

For the ninth congress (Lausanne, 1899) the rules were changed so that players with an equal number of points were paired against each other, but in case of a draw one player was still counted as the “winner” and the other as the “loser”. Only in the rules for the St Gallen congress (1901) was it stated that the actual number of points was the sole criterion for pairing.

This does not exclude the possibility that the pairings were handled in the modern way long before the St Gallen tournament (after all, the members of the pairing committee were presumably always the same), but it still leaves open the question of why the 1895 tournament is commonly singled out as marking the birth of the Swiss System.

Incidentally, in 1940 Erwin Voellmy referred to Julius Müller as the inventor of the “Swiss (or sometimes Danish) pairing system” (Schweizerische Schachzeitung, May 1940, page 71). What is known about these Danish roots of the Swiss System?’

(4118)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) raises two matters concerning New York, 1924 on the basis of information in the tournament book: a) the speed with which the event was organized and b) the pairing system used.

We offer some supplementary facts from the 1924 volume of the American Chess Bulletin, whose editor, Hermann Helms, was on the board of the tournament directors.

Page 1 of the January 1924 issue announced the proposed tournament:

‘First steps were taken at a meeting in New York on 18 January, having in view a possible gathering of the world’s leading experts as early as 17 March.

As we go to press, there is no absolute certainty as to its taking place, as planned. It is sufficient to say that a number of good men and true are bending all their energies to make it so. Should success crown their efforts, then the congress will be quite unique in the annals of the game, at least in so far as rapidity of action is concerned.

This much can be said. Thanks to good use of the cable, the readiness of several European masters to come over has been ascertained.’

And from page 2:

‘Although a total of nearly $10,000 will be required to defray the expenses, including the prizes, as well as the transportation of several European experts, close upon $4,000 was pledged as a starter [at the committee’s meeting on 18 January].

The members of the committee undertook to raise most of the balance through subscriptions within a fortnight, after which word was to be sent to Europe to the masters who are in readiness to come whenever the call is issued.’

Page 25 of the February 1924 Bulletin stated:

‘Since the announcement made in the January issue of the Bulletin, matters have progressed famously in connection with the New York International Chess Masters’ Tournament. It is now an assured fact. New York, therefore, will be the scene for a gathering of the world’s most famous masters, the like of which is not apt to be witnessed again in our generation.’

Page 4 of the tournament book reported:

‘With the hearty co-operation of Dr Arthur A. Bryant [the Treasurer] and Mr Helms, the preparations at this end were carried forward with the least possible delay, and on 8 March we were able to welcome the masters at the docks with the satisfying knowledge that everything was ship-shape, barring, perhaps, some of the masters. Several unforeseen incidents helped to maintain the interest and contribute a bit of anxiety, chiefly the illness of Capablanca from a severe attack of la grippe, which made his participation in the tournament somewhat doubtful up to the last minute.’

Source: page x of the tournament book.

The pairing system was set out in point 19 of the tournament rules (pages 27-28 of the February 1924 American Chess Bulletin):

‘The draw will be made according to the Berger system and the players will draw their own numbers before beginning of the tournament. The number of the round to be played each day will be decided by draw and announced 15 minutes before beginning of playing hours. The first half of the tournament must be completed before any of the rounds of the second half are drawn.

The draw for numbers took place on 11 March (American Chess Bulletin, March 1924, page 49), and the first round of play was on 16 March.

Mr Niessen asks whether other major tournaments have handled pairing in a similar way.

(6608)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) quotes from the Hastings, 1895 tournament book edited by Horace F. Cheshire (London, 1896):

‘The order of play and pairing will be decided by the president drawing lots publicly immediately before the commencement of the Tournament. The future pairing will depend on this, but will not be known until the morning of each day. (Page 6.)

‘The president then made the draw of the names to match with the numbers with which the pairings had been arranged; ... this draw determined the first moves and the pairings of all the rounds, but not the order in which the rounds were to be played. The draw was then made for the round for the day, and the president explained that he, or in his absence the director in charge, would make this draw each day before play commenced.’ (Pages 10-11, in the section entitled ‘The Opening Day’.)

‘No-one knew, till the morning of each day, who would meet ...’ (Page 367, under ‘The Innovations’.)

(6631)

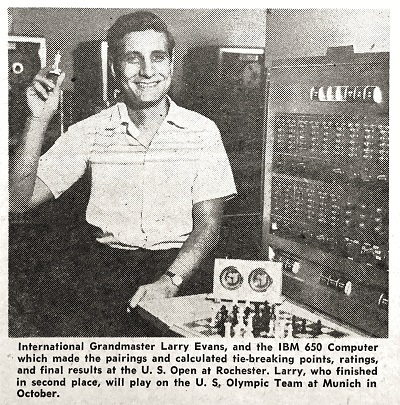

This cutting from page 1 of Chess Life, 5 September 1958 has been forwarded by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

Which was the first open tournament where all the pairings were made by a computer?

(11097)

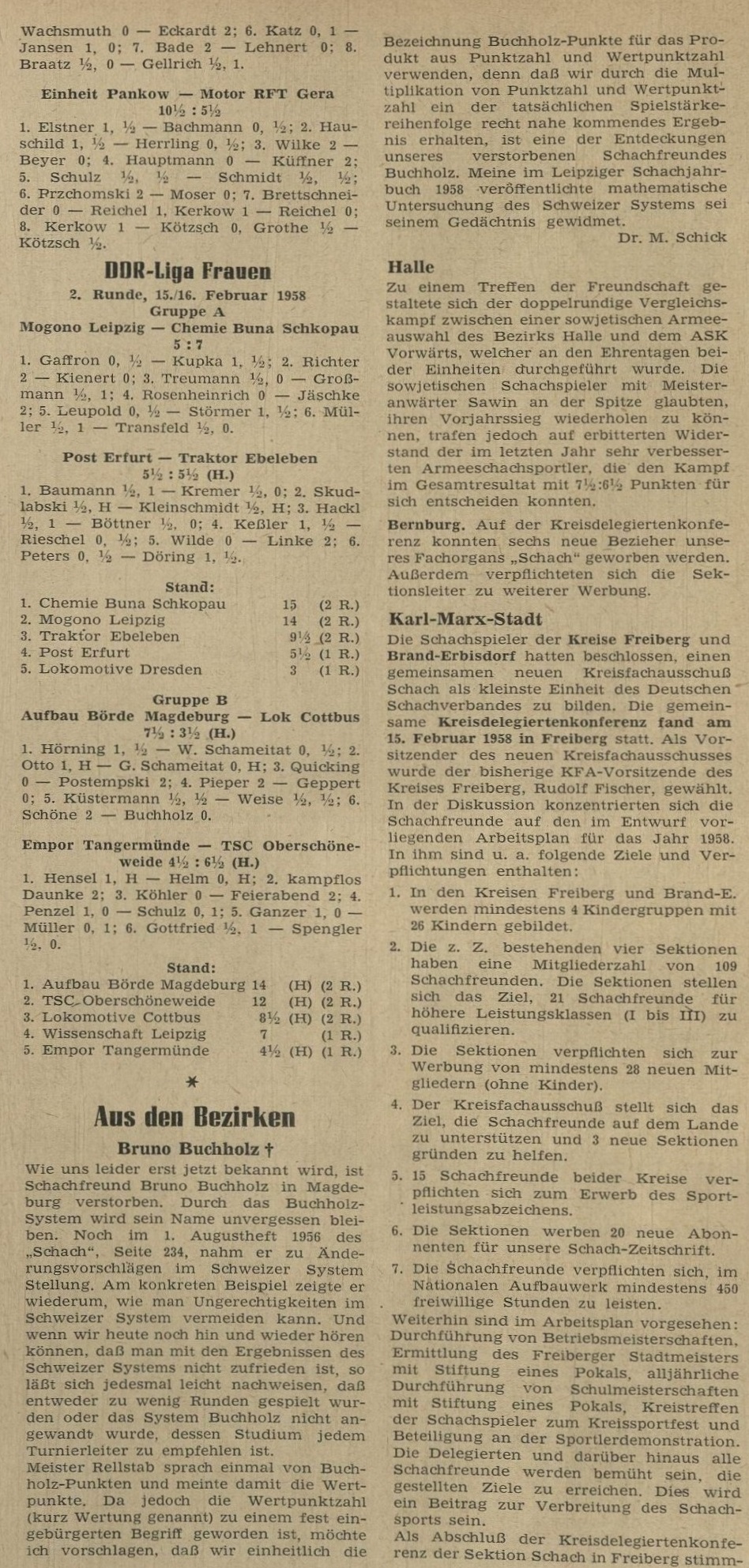

A commonly misspelled name is Buchholz, and Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige (Jefferson, 1987 and subsequent privately circulated information) has a brief entry for Bruno Buchholz, who died circa 1958 in Magdeburg, East Germany. The only contemporary reference cited by Gaige was ‘Schach, 1958, page 96’.

That was the culmination of a series of pairing articles in the German magazine, and with the assistance of the Cleveland Public Library we reproduce the sequence:

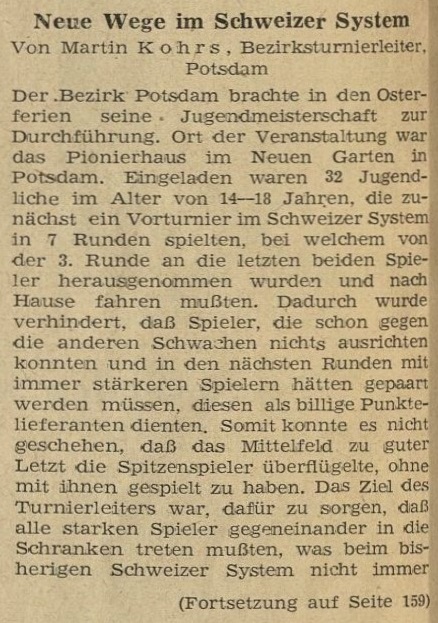

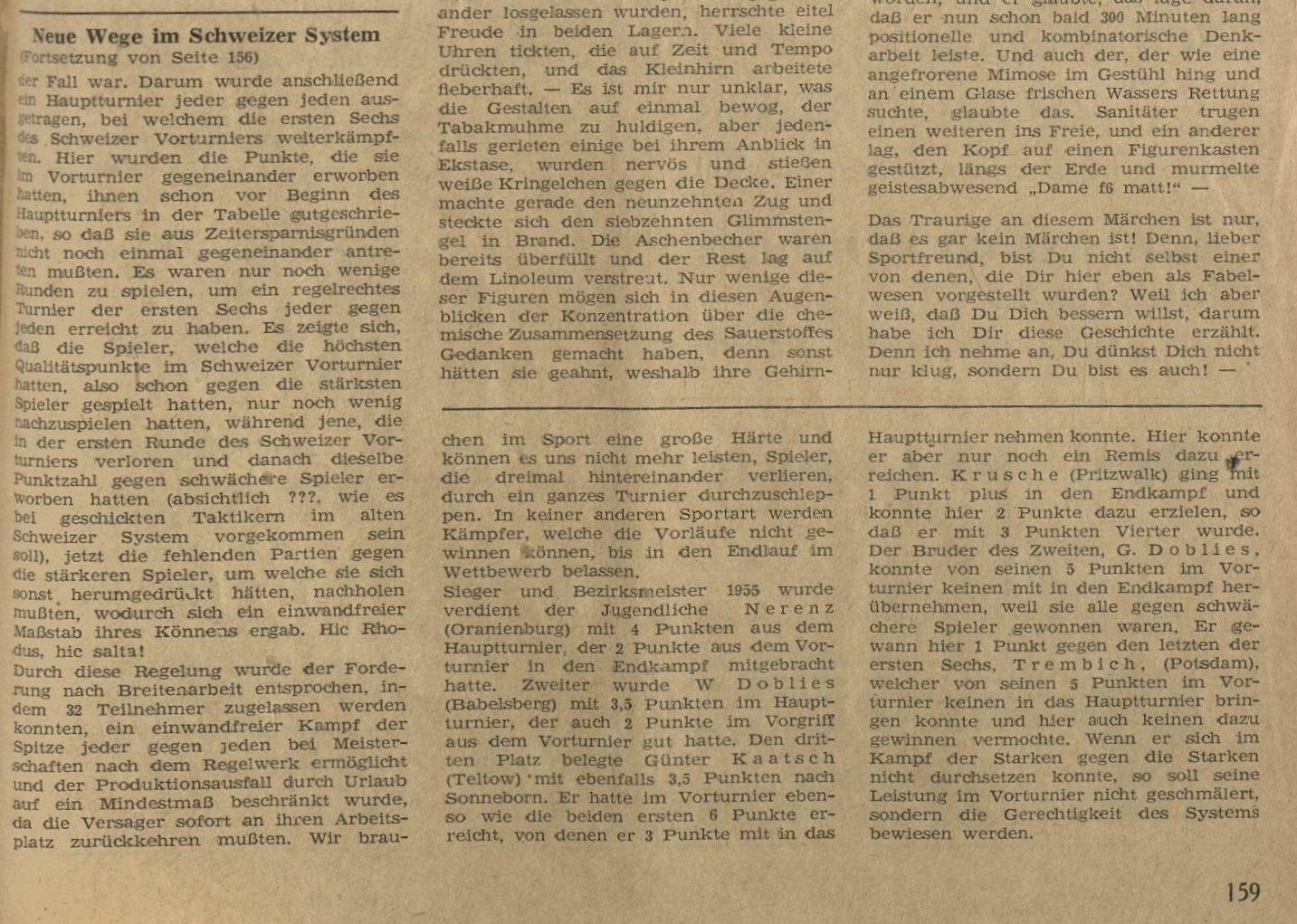

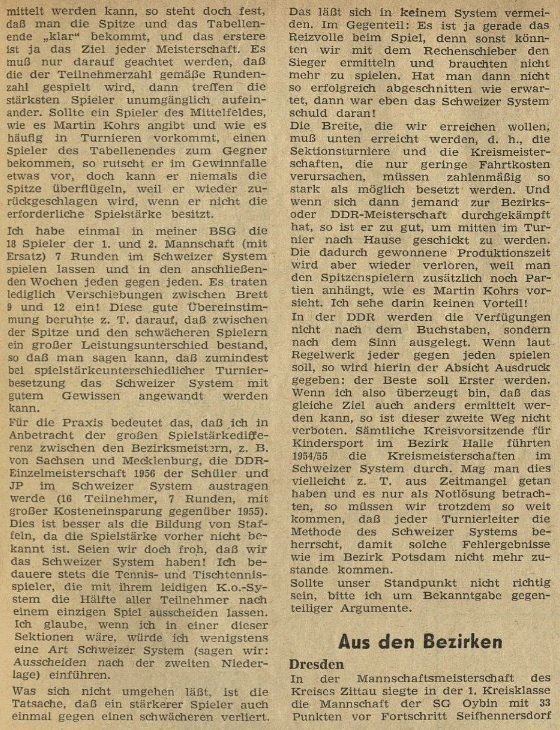

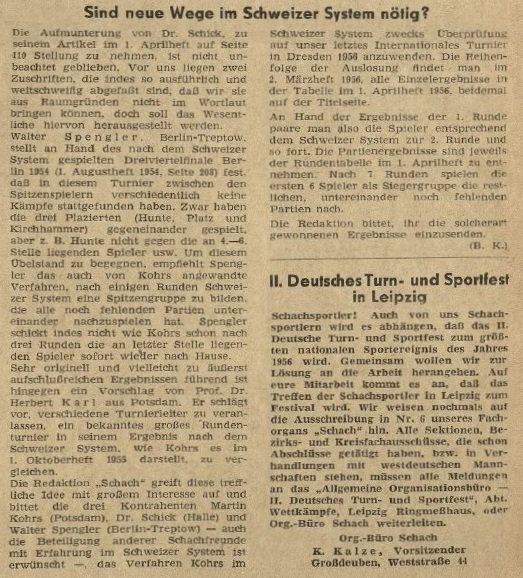

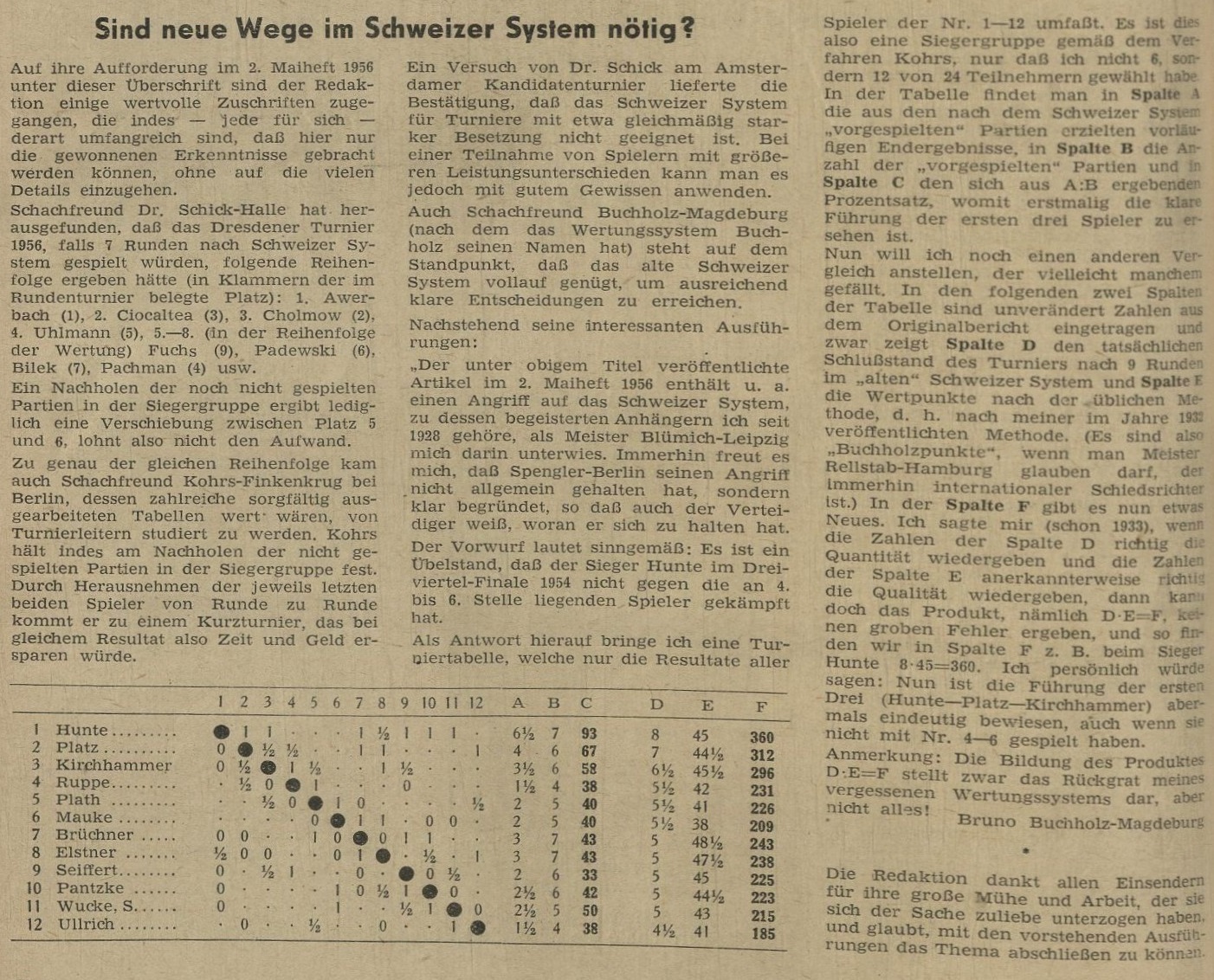

Schach, 10/1955, pages 156 and 159:

Schach, 1/April 1956, pages 110-111:

Schach, 2/May 1956, page 153:

Schach, 1/August 1956, page 234:

Schach, 2/March 1958, page 96:

Carl Fredrik Johansson (Stockholm) enquires about the origins of the Monrad pairing system, and we offer some initial jottings.

An article by K.D. Monrad entitled ‘Et nyt Turneringssystem’ (A New Tournament System) was published on pages 40-41 of the April 1925 issue of the Danish magazine Skakbladet, with a follow-up article by him on page 81 of the July 1925 edition. There was extensive discussion of the system in Norsk Schakblad, beginning on pages 130-132 of the September 1925 number (contributions by Erling Wold and O. Trygve Dalseg) and continuing in December 1925, pages 180-181 (Erling Wold) and January-February 1926, page 13 (O. Trygve Dalseg).

All the above material can be conveniently viewed online: see Skakbladet and Norsk Schakblad.

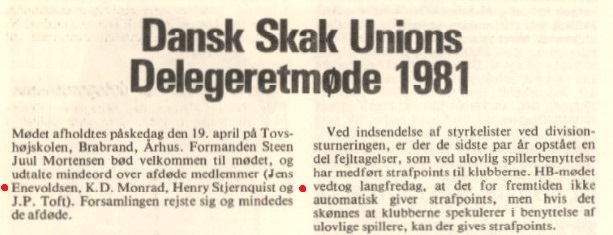

About K.D. Monrad, further information will follow, with readers’ assistance. For the time being, we note a reference on page 102 of the 6/1981 Skakbladet:

(12096)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.