Edward Winter

(1434)

On page 296 of The Art of Chess (London, 1895) James Mason wrote:

‘Fairly tried and found wanting, the Sicilian has now scarcely any standing as a first-class defence.’

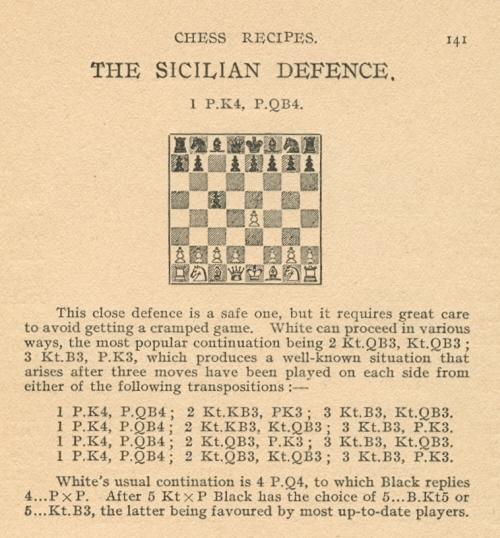

When discussion of the Sicilian Defence began on page 355 of L’ABC des échecs by N. Preti (Paris, 1906), the move 1...c5 was given a question mark.

(2936)

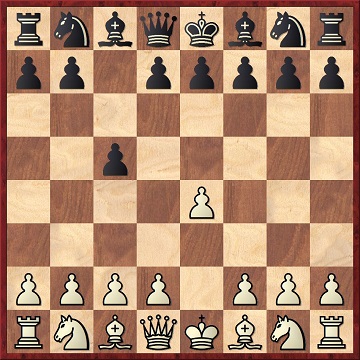

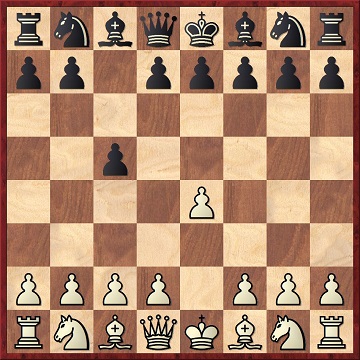

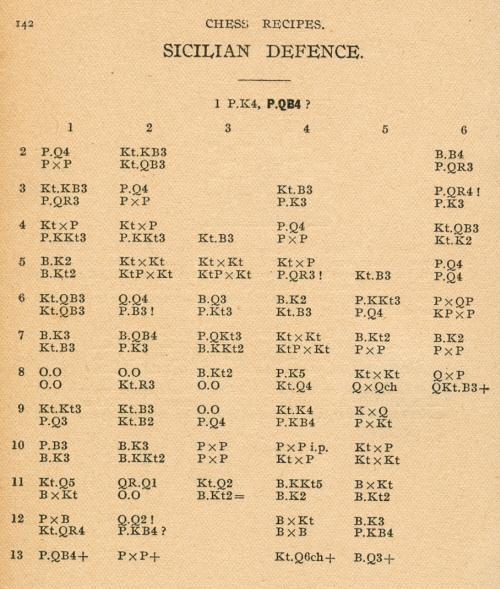

Concerning Chess Recipes by E.A. Greig (Stroud, 1914), below is the book’s full coverage of the Sicilian Defence, which includes, at one point, a question mark for 1...c5:

(6788)

From Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA):

‘Robert Snyder published a booklet The Snyder Sicilian in which he dared to name 1 e4 c5 2 b3 after himself. As I pointed out in the Myers Openings Bulletin, that was played by Cochrane against Staunton, and later in major competition by Kieseritzky and L. Paulsen. Then in this century it was practised by Czerniak; he published analysis of it in the 1940s, and it has his name. Then Snyder did it again, continuing to name the opening after himself in a larger book. Worse is that US magazines such as Chess Life and the Chess Correspondent publish his writings, without editing his claims.’

Hugh Myers has consistently argued – with great force – against those who name chess openings after themselves, and we go with him all the way.

(799)

C.N. 11852 gave a game won by Myers with 1 e4 c5 2 a4.

From the back-cover blurb of the T.U.I. Openings Booklet The 2 f4 Sicilian by Nigel Davies (Plumstead, 1985):

‘Considering that the move 2 f4 is an immediate way to sidestep the vast bulk of normal Sicilian opening theory, it is remarkable that it has not been played more. One explanation for this may be the surprising dearth of literature on this variation.’

(950)

The heading of this item was ‘La Ronde’.

We are still trying to find out on what grounds R.N. Coles wrote on page 137 of Dynamic Chess (London, 1956) that Capablanca gave as his reason for practically never playing the Sicilian Defence, ‘Black’s game is full of holes’ (C.N. 2105). The passage is on page 135 of the Dover edition (New York, 1966).

Another alleged remark on which more information would be welcomed appeared in a tribute to Capablanca by Reuben Fine on page 3 of The Chess Correspondent, May-June 1942:

‘Capa was a perfect example of the intuitive type of master, who sees that a move is good, but cannot explain why. I recall a story told me by a strong amateur in Mexico, whom Capa once offered to teach. The gentleman was overjoyed and promptly appeared the next day for his lesson. “In the Sicilian Defense”, Capa explained, “after 1 e4 c5 the best move is 2 Ne2.” “Why?” “No importa, it does not matter; it is the best move.” And that was about all that the poor amateur could find out; it was the best move and that was all there was to it. Capa’s judgement was usually right, so this absolute certainty in himself was an invaluable asset.’

(3961)

Source: page 137 of Dynamic Chess by R.N. Coles (London, 1956). In the 1966 Dover edition, the passage is on page 135.

C.N. 2105 (see page 155 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) asked where, if anywhere, Capablanca wrote the ‘full of holes’ remark. Reiterating the question (which remains unanswered today), C.N. 3961 added a passage by Reuben Fine that we had found on page 3 of The Chess Correspondent, May-June 1942:

From page 18 of Capablanca: A Primer of Checkmate by Frisco Del Rosario (Newton Highlands, 2010):

Finally, an extract from pages 40-41 of Capablanca move by move by Cyrus Lakdawala (London, 2012), in a discussion on 1 d4 f5 2 e4:

In short, Lakdawala credits Del Rosario for material which the latter lifted from C.N. 3961, and Lakdawala’s insertion of the ‘full of holes’ remark in the story of a Mexican pupil is a plain fabrication, as is his claim that Capablanca called 2 Ne2 ‘perhaps a refutation’.

(10344)

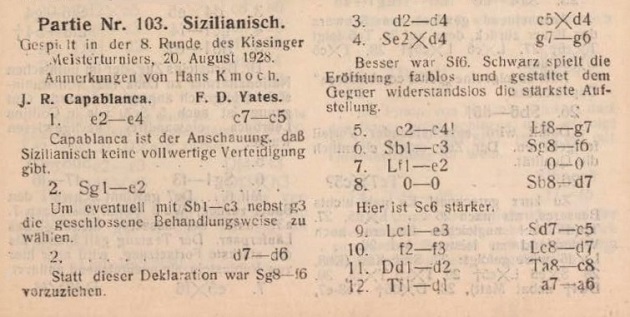

The start of Hans Kmoch’s annotations to Capablanca v Yates, Bad Kissingen, 1928 on page 259 of the Wiener Schachzeitung, September 1928:

(10383)

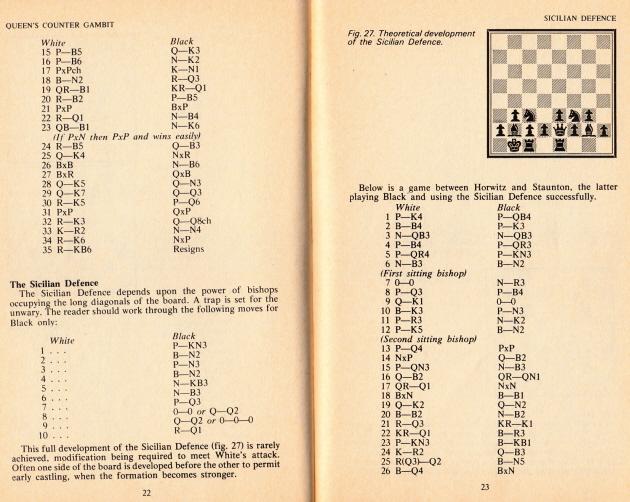

Charles Milton Ling (Vienna) draws attention to the coverage of the Sicilian Defence in Discovering Chess by R.C. Bell (Aylesbury, 1976):

(8482)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) has provided this magazine cover:

See Gaffes by Chess Publishers and Authors.

Page 79 of Soltis’s Pawn Structure Chess (New York, 1976) notes that in his autobiographical Izbrannyye partii, published in 1953, F. Dus-Chotimirsky claimed to have invented the name ‘Dragon Variation’. This is another term whose origins tend to be skated over by the reference books. Dus-Chotimirsky recorded (pages 57-58) that his astronomy studies had led him, in 1901, to see a resemblance between the black pawn formation and ‘the pattern of Draco the Dragon in the northern sky’. It would be interesting to discover when ‘Dragon Variation’ started appearing in print.

(Kingpin, 1992)

A dozen years ago we discussed briefly and inconclusively the origins of the name ‘Dragon Variation’ in the Sicilian Defence and wondered when it began appearing in print.

No proposals having been received, we make a start here by quoting from page 43 of the February-March 1925 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond. After the moves 1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be2 g6, H. Weenink referred to ‘De “drakevariant” van den Siciliaan’.

(3311)

Pre-1925 citations are sought, and in the meantime we quote an author who considered the Dragon Variation to be a line for White. The game below was annotated on pages 52-53 of Les échecs par la joie by Aristide Gromer (Brussels, 1939), and we give only the notes relevant to the ‘Dragon’ name:

Aristide Gromer – A. Baulier [‘Beaulier’]

French Championship, Toulouse, 1937

Sicilian Defence

(‘... La “Sicilienne” se distingue principalement par un effort des Noirs sur l’aile Dame tandis que les Blancs portent leur activité sur l’aile Roi. La variante la plus caractéristique de cette conception stratégique est la variante dite “du Dragon”, dont nos disciples trouveront un spécimen dans la partie qui suit.’) 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be2 (‘Le coup préparateur de l’avance à la dragonne future.’) 6...g6 7 Be3 Bg7 8 O-O O-O 9 Nb3 Be6 10 f4 Na5 11 f5 Bc4

12 g4 (‘Le coup constitutif de la variante dite du “Dragon”. Il faut d’ailleurs faire bien attention à ce que le Dragon ne perde pas son souffle; car les Blancs découvrent leur Roi et une contre-attaque des Noirs serait des plus dangereuses.’) 12...Rc8 13 Bd4 a6 14 g5 (‘Dans ce genre d’attaques à la dragonne, il ne faut pas perdre de temps.’) 14...Bxe2 15 Nxe2 Nh5 16 Bxg7 Nxg7 17 Nbd4 Nc4 18 Qc1 d5 19 b3 Ne5 20 f6 exf6 21 gxf6 Nh5 22 Qg5 Nd7 23 e5 Re8

24 e6 Ndxf6 25 exf7+ Kxf7 26 Nf4 Qb6 27 Rad1 Nxf4 28 Rxf4 Kg7 29 Kh1 Re4 30 Rxe4 dxe4 31 Nf5+ Resigns. (‘L’attaque du “Dragon” est une attaque dangereuse. Elle doit être conduite de la part des Blancs avec célérité (comme toutes les attaques) car les Noirs ont d’intéressantes possibilités de contre-attaque.’)

Have other writers used ‘Dragon Variation’ for the pawn advance g2-g4 in the Sicilian Defence? We wonder too how well known the term was in any context during Gromer’s career. For instance, pages 571-572 of L’Echiquier, February 1927 had a French translation of Kmoch’s annotations to a game (Kostić v Canal, Meran, 1926) which began 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6; the note to Black’s fourth move included a reference to ‘La “Drachen” variante choisie ici’, implying unawareness that use was being made of a German term for the Dragon Variation.

Aristide Gromer (born in 1909) was discussed on pages 175-177 of Chess Facts and Fables, and we still have no information about him from the 1940s onwards. The picture below was published opposite page 80 of El Ajedrez Español, November 1934.

Aristide Gromer

(5135)

With regard to the earliest appearance of the term ‘Dragon Variation’, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) mentions that Tartakower referred to ‘Die Drachenvariante’ in a note to Alekhine v Sämisch, Vienna, 1922 (after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6) on page 270 of Die hypermoderne Schachpartie (published in instalments in 1924-25, as mentioned in C.N. 5279).

Looking further into the matter, we can cite an annotation by Heinrich Wolf on page 164 of the June 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung, after 1 c4 e5 2 a3 Nf6 3 e3 Be7 4 Qc2 in Tartakower v Lasker, New York, 1924:

‘Damit ist eine wohlbekannte Variante aus der sizilianischen Verteidigung (die sogenannte Paulsensche Drachenvariante) entstanden, nur mit dem Unterschied, dass Weiss vorläufig die Rolle des Verteidigers freiwillig auf sich genommen hat.’

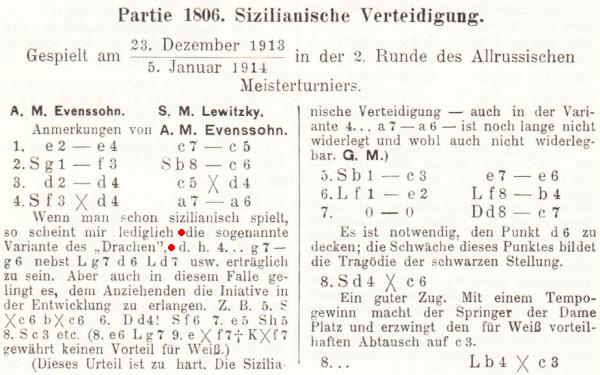

More significantly, we have found the following on page 30 of the January-February 1914 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung:

(7826)

Concerning The Dragon Variation by Anthony Glyn, see Chess in Fiction.

The death of Mikhail Kalashnikov on 23 December 2013 prompts us to ask when the opening 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 d6 first bore his name, and why.

We timidly open the bidding by noting that on page 25 of the April 1991 CHESS, in an article by Ian Rogers, a game between Solomon and Gausel in the 1990 Olympiad in Novi Sad was headed ‘Sicilian Kalashnikov’.

Page 479 of the October 1991 BCM mentioned a monograph by Jeremy Silman, The Neo-Sveshnikov, and commented:

‘The line 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 d6, known jocosely as “Kalashnikov”, has a band of followers of repute.’

Neil McDonald’s 1995 book on the opening has nothing of direct relevance to the origins of the name ‘Kalashnikov’.

(8450)

Joose Norri (Helsinki) points out the first note by John van der Wiel in his game, as Black, against Nigel Short at the 1988 Olympiad in Thessaloniki:

Source: New in Chess, 1/1989, page 35.

(8456)

Joose Norri quotes a remark by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam in a report on the Wijk aan Zee tournament on page 18 of the 2/1990 New in Chess:

‘In recent times Short has enriched the Kalashnikov – the semi-automatic, fast-firing version of the Sveshnikov – with many interesting ideas ...’

(8493)

The game Mellgren v Alekhine, Örebro tournament, 1935 (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 e5 6 Nxc6 bxc6 7 Bg5 Rb8 8 Bxf6 Qxf6 9 Bc4 Rxb2 10 Bb3 Bb4 11 Qd2 d5 12 exd5 e4 13 O-O-O Bxc3 14 Qe3 O-O 15 d6 Bg4 16 d7 Bxd1 17 Rxd1 Ba5 18 Qd4 Qxd4 19 Rxd4 Rxb3 20 White resigns) was published by Purdy on page 216 of the Australasian Chess Review, 1 August 1935 with the heading ‘Alekhine goes back to Labourdonnais for his latest novelty!’ However, the Frenchman’s ...e5 against McDonnell always came on the fourth move. Nowadays, of course, the line with 5...e5 is called the Lasker-Pelikan, although Emanuel Lasker played it in only one serious game in his entire life (the ninth match-game with Schlechter, 1910, drawn after 65 moves).

(577)

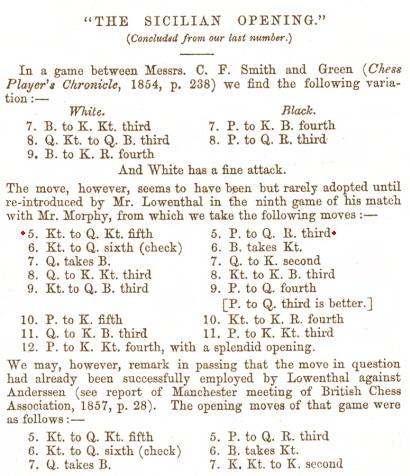

Carl Boor (Columbus, OH, USA) asks why 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 a6 is often called the Löwenthal Variation and whether Johann Löwenthal ever played it.

As regards terminology, the chapter on the ‘Lowenthal Variation’ on pages 140-144 of Beating the Sicilian 2 by John Nunn (London, 1990) began:

Page 202 of the tenth edition of Modern Chess Openings (Evans/Korn, 1965) stated that 4...e5 ‘was originated in the game Macdonnell-Labourdonnais in 1839 and later enlarged upon by Löwenthal’. The year 1839 was naturally wrong (Alexander McDonnell having died in 1835), and on page 174 of the eleventh edition (Korn, 1972) the comment on 4...e5 became:

‘This thematic move was originated in a game MacDonnell-Labourdonnais in 1934 and later enlarged upon by Löwenthal.’

The same sentence appeared on page 208 of the twelfth edition (Korn, 1982), except that the correct date, 1834, was given at last.

An historical note regarding 4...e5 was provided on page 355 of La defensa siciliana by Carlos A. Palacio (Havana, 1973), in a chapter headed ‘Variante Lowental [sic] – Labourdonnais’:

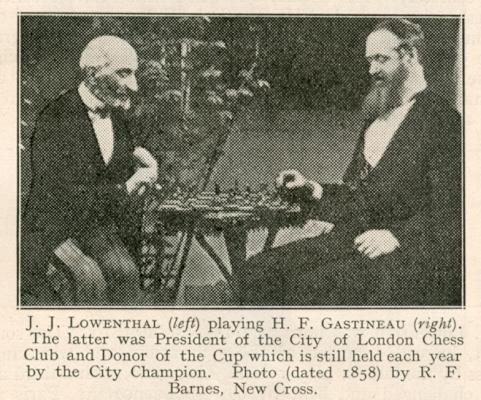

Löwenthal’s match against Morphy in 1858 was played in London, not Paris. The Sicilian Defence occurred twice:

Both games were annotated by Löwenthal in his book Morphy’s Games of Chess (London, 1860), but his observations contain nothing of relevance to the ‘Löwenthal Variation’ appellation.

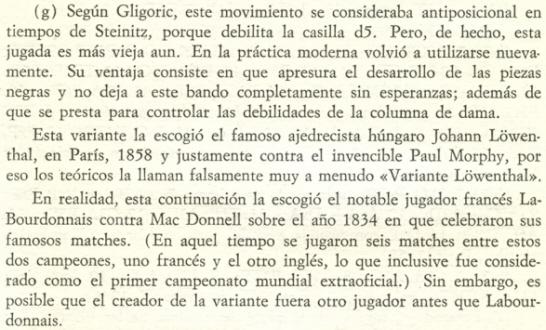

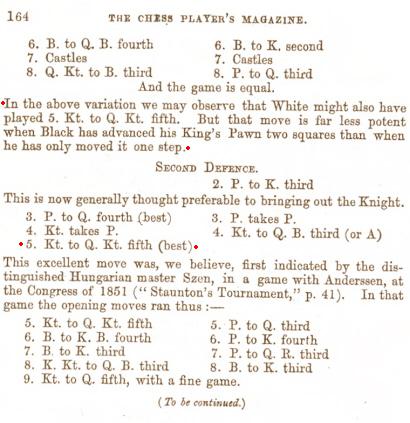

We recall no games by Löwenthal which began 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 a6, but in 1865 the Chess Player’s Magazine (of which he was the editor) had an article in six instalments, ‘The Sicilian Opening’. The fifth part (pages 162-164) discussed a line which began 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 (‘best’) 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nf3 (‘best’) Nf6, and page 164 contained this comment:

‘In the above variation we may observe that White might also have played 5 Nb5. But that move is far less potent when Black has advanced his king’s pawn two squares than when he has only moved it one step.’

Then the article turned to the ‘second defence’ (2...e6), the ‘first defence’ having been 2...Nc6. The following moves were given: 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nc6 5 Nb5.

When the article was resumed on page 193 of the following issue, Löwenthal was named (with an incorrect reference to the ‘ninth game’, instead of eleventh, of his match against Morphy):

The awkward presentation, in conjunction with different positions in which 5 Nb5 could be played, offered scope for complications and misunderstandings about the use of Löwenthal’s name, but the whole matter seems murky. Wanted: early uses of the term ‘Löwenthal Variation’ with reference to a) 4...e5 only and b) 4...e5 5 Nb5 a6.

Source: BCM, August 1926, page 346.

We can cite only one nineteenth-century game which reached the diagrammed position: the 11th match-game between de Rivière and Journoud (Paris, 1859). Staunton annotated it on page 19 of the 7 January 1860 Illustrated London News, and we are grateful to Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) for supplying a copy:

(6580)

A remark about Géza Maróczy by Capablanca on pages 149-154 of the Spanish version, Lecciones elementales de ajedrez (Madrid, 1973):

‘His chief contribution to opening technique has been the well-known variation in the Sicilian Defence wherein White places pawns at a2, b3, c4, e4, f3, g2 and h2, against black pawns at h7, g6, f7, e7, d6, b7 and a7. White’s formation is considered so advantageous that Black generally avoids it by all means available.’

Wanted: information about the origins of the Maróczy Bind, named after Géza Maróczy. One of the few writers to venture a precise game reference is Andrew Soltis. Pages 97-98 of his Pawn Structure Chess claim that ‘the first master game to gain recognition of the Bind was Swiderski v Maróczy, Monte Carlo 1904, in which Maróczy, with Black in a Dragon formation, was the “bindee” rather than the “binder”. It was his opponent who played P-QB4 and P-K4. But for years later Maróczy, a great Hungarian grandmaster and chess journalist, repeatedly drew attention to the powers of the Bind, and, by the 1920s, permitting the Bind was equated with making a blunder.’

The quoted Swiderski Bind actually arose through transposition; the opening moves were 1 e4 c5 2 c4 Nc6 3 Nf3 g6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Bg7 6 Be3 Nf6 7 Nc3 d6 8 Be2 Bd7 9 O-O O-O, and subsequent imprecision by White gave Maróczy the game in 48 moves. Around this time, an early c4 by White in the Sicilian was being linked to Maróczy’s name (e.g. Wiener Schachzeitung, October 1906, page 348), but it is far from easy to trace early specimens of the Maróczy Bind, played either by G.M. himself or by other masters.

(Kingpin, 1992)

An addition on page 148 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

Page 79 of the March-April 1906 Wiener Schachzeitung reproduced from Magyar Sakklap Maróczy’s annotations to the 16th match-game between Tarrasch and Marshall at Nuremberg, November 1905 (which began 1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 a6 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Be2 Bg7 6 Nc3 Nc6). On four consecutive moves (3-6) Maróczy stressed the value of the move c4.

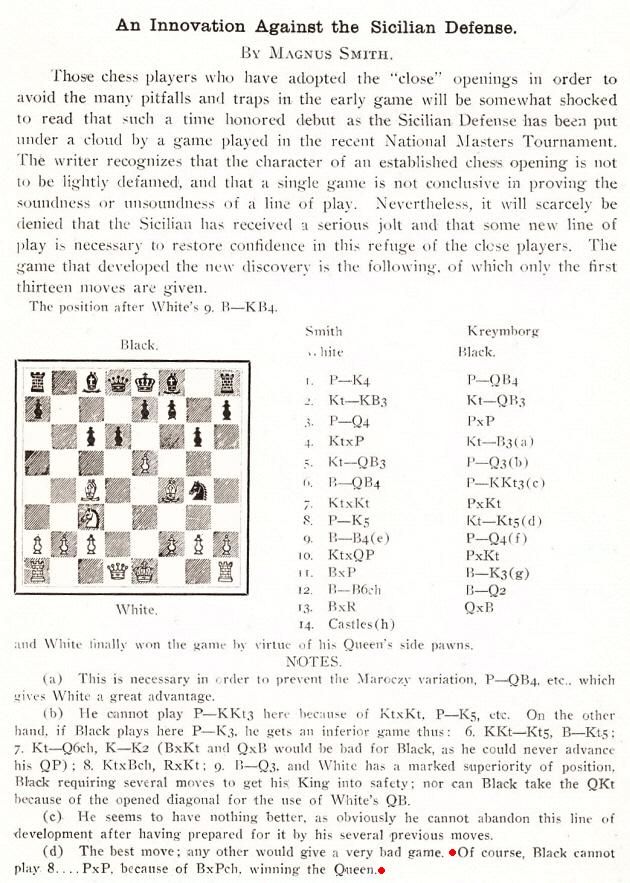

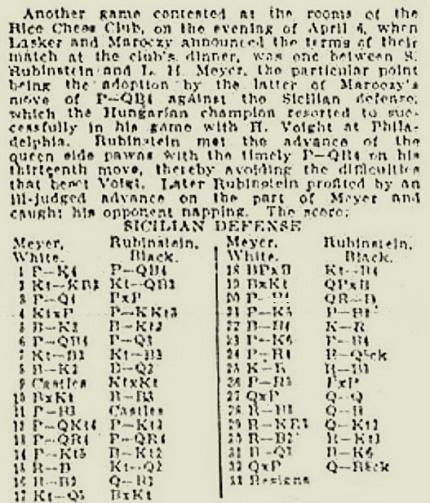

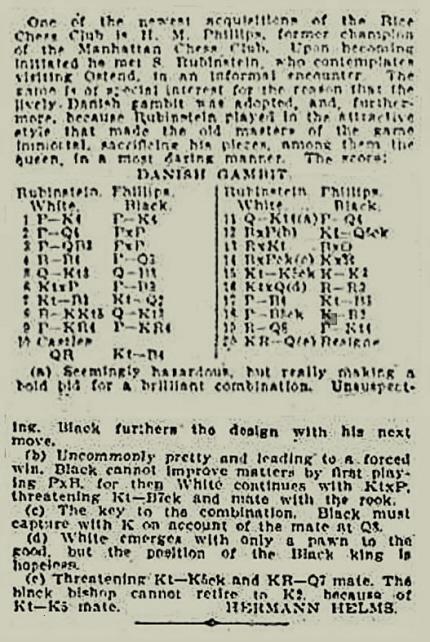

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has found that the game discussed in C.N. 8541 is the second of two victories by Solomon Rubinstein published by Hermann Helms on page 9 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 May 1906:

The Meyer v Rubinstein game (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Be3 Bg7 6 c4 d6 7 Nc3 Nf6 8 Be2 Bd7 9 O-O Nxd4 10 Bxd4 Bc6 11 f3 O-O 12 b4 b6 13 a4 a5 14 b5 Bb7 15 Rc1 Nd7 16 Bf2 Qc7 17 Nd5 Bxd5 18 cxd5 Nc5 19 Bxc5 dxc5 20 f4 Rac8 21 e5 f6 22 Bc4 Kh8 23 e6 f5 24 h4 Bd4+ 25 Kh1 Rf6 26 h5 gxh5 27 Qxh5 Qd8 28 Rf3 Qf8 29 Rh3 Qg7 30 Rc2 Rg6 31 Bd3 Be3 32 Qxf5 Qa1+ 33 White resigns) is of relevance to the discussion on the origins of the Maróczy Bind on pages 147-148 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

(8544)

Further to C.N. 8544, Mr Blackstone sends the Maróczy v Voigt exhibition game mentioned by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, from the supplement section of the Los Angeles Herald, 29 April 1906:

Géza Maróczy – Hermann G. Voigt

Philadelphia, 1906

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 g6 4 Nxd4 Bg7 5 c4 Nf6 6 Nc3 d6 7 Be2 O-O 8 Be3 Bd7 9 O-O Nc6 10 h3 Nxd4 11 Bxd4 Bc6 12 Bf3 Re8 13 b4 b6 14 a4 Rc8 15 a5 Qc7 16 axb6 axb6 17 Ra6 Nd7 18 Bxg7 Kxg7 19 Qa1 Ne5 20 Ra7 Qd8 21 Be2 Bd7 22 Nd5 Kg8 23 Rc1 e6 24 Ne3 h5 25 b5 Qh4 26 Rd1 Qf4 27 g3 Qh6 28 Rxd6 Resigns.

We add that brief notes by Maróczy were published on page 76 of the April 1906 American Chess Bulletin. After 5 c4 he wrote:

‘This continuation has been emphatically recommended by me. P-Q4 is no longer possible to Black and he obtains a cramped game.’

(8545)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) notes that when the Maróczy v Voigt game given in C.N. 8545 was published on page 2 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 April 1906, the following assertion came after 1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 g6 4 Nxd4 Bg7 5 c4:

‘This is Mr Maróczy’s new move, and he is so sure that it gives White a great advantage that he offered to give Dr Tarrasch five games out of ten if the doctor would play the variation taking the black pieces. The doctor, however, declined.’

(9901)

The above position arose after 1 Nc3 g6 2 e4 c5 3 Nf3 Bg7 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nc6 6 Be3 d6 7 Bc4 Nf6 8 f3 O-O 9 O-O Bd7 10 Qd2 a6 in the rapid game Shipman v Fischer, New York, 1971. See, for instance, pages 318-319 of volume three of Bobby Fischer (Madrid, 1993).

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére points out that the position after Black’s tenth move had occurred in the following game, from a four-college tournament:

N. Hull (Yale) – Frederick Bayard Barshell (Columbia)

New York, 31 December 1902

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Be3 Bg7 6 Nc3 Nf6 7 Bc4 d6 8 O-O O-O 9 f3 Bd7 10 Qd2 a6 11 a3 Rc8 12 Bb3 Kh8 13 Rad1 Kg8 14 Nd5 Nxd5 15 exd5 Ne5 16 Rfe1 Nc4 17 Bxc4 Rxc4 18 b3 Rc8 19 a4 (‘P-KR4’) 19...e5 20 dxe6 fxe6 21 c4 Be5 22 f4 Bxf4 23 Bxf4 e5 24 Bh6 exd4 25 Bxf8 Qxf8 26 Qxd4 Rc6 27 Rf1 Bf5 28 b4 Qc8 29 Rc1 Be6 (‘P-R3’) 30 b5 axb5 31 axb5 Rc5 32 Qxd6 Bf5 33 Qe7 Rxc4 34 Rxc4 Qxc4 35 Qxb7 Bd3 36 Qb8+ Resigns.

Source: The Sun (New York), 1 January 1903.

The opening (a ‘Rauzer Sicilian’) is to be noted. As indicated in the game-score above, at two points our correspondent has amended the moves given in the Sun, to make sense of the ensuing play.

For Black’s name, the newspaper report had both ‘Barshell’ and ‘Barshall’. The details we have incorporated in the game heading come from page 47 of Columbia University Alumni Register 1754-1931 (New York, 1932). His identity is confirmed by the report on the tournament in the New York Times, 30 December 1902.

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) is seeking pre-1932 specimens of the Richter (or Richter-Rauzer) Attack in the Sicilian Defence (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5).

We have found two games so far:

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 d6 6 Bg5 (Müller-Nandor v Gregory, Barmen, 1905 – see pages 388-389 of the tournament book).

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 (Breyer v von Balla, Budapest, 1913 – Magyar Sakktörténet, volume 3, page 128).

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) reports that his database has the following early examples with the move order 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5:

Rausch v Schönmann, Hamburg, 1910

Pavlov v Golubev, Leningrad, 1922

Alekhine v Board 7, Blindfold exhibition, Paris, 1925

E.G. Sergeant v Winter, Scarborough, 1930.

(Kingpin, 1997)

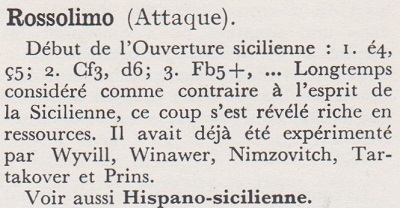

Position after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5

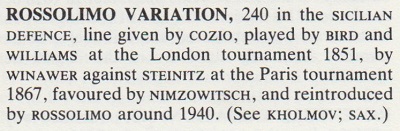

Some initial historical jottings are offered on the Rossolimo Variation of the Sicilian Defence, played in the 2018 world championship match between Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana.

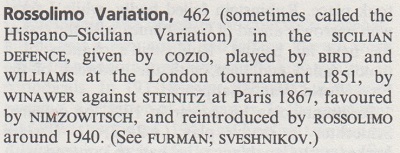

What cannot be given for now is a comprehensive explanation as to when Rossolimo’s name was attached to – or, indeed, detached from – the opening. Databases have relevant Rossolimo games from the late 1940s onwards, and the reference to ‘around 1940’ in The Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (1984 and 1992 editions) has yet to be substantiated:

1984 edition, page 286

1992 edition, page 345

Annotating Rossolimo v Romanenko, Salzburg, 1948 on pages 647-648 of the October 1975 Chess Life & Review, Pal Benko wrote after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5:

‘Rossolimo usually avoided normal Sicilian patterns, and the text was one of his favorites. Nimzowitsch played this against Gilg in 1927, but it was Rossolimo who, through his frequent use of it, made this system an effective and fully respectable weapon. For a time, it was known as “the Rossolimo Variation” and is today commonly seen with colors reversed in the English Opening’ [as in the game Barry v Rossolimo, World Open, New York, 1975 which Benko annotated on page 648].

Page 181 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967 and 1974) called 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 ‘L’attaque hispano-sicilienne’, and had the following on page 340:

C.N. 1230 drew attention to the obvious inaccuracy of this text on page 1 of The Anti-Sicilian: 3 Bb5(+) by Y. Razuvayez and A. Matsukevitch (London, 1984):

Although the Companion also mentioned Winawer v Steinitz, Paris, 1867, that game began 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 Bb5, as shown on pages 182-183 of the tournament book.

When were the moves 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 first played? The earliest game that we have found is on pages 327-328 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1845 (volume six), a win by Elijah Williams against John Withers, played (according to page 325) ‘very recently at Bristol’:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nd4 4 Nxd4 cxd4 5 O-O e5 6 d3 Qb6 7 Bc4 d6 8 f4 Be6 9 Bxe6 fxe6 10 fxe5 O-O-O 11 Rf7 dxe5 12 Bg5 Nf6 13 Nd2 h6 14 Nc4 Qb5 15 Bxf6 gxf6 16 Qg4 f5 17 exf5 h5 18 Qg6 Rh6 19 Rxf8 Rxg6 20 Nd6+ Kd7 21 Rxd8+ Kxd8 22 Nxb5 and wins.

Source: XIV. Schach-Olympiade Leipzig 1960, page 192.

(11098)

1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 d3 a6 5 a3 Qc7 6 f4 b5 7 Ba2 Bb7 8 Nf3 Be7 9 O-O Nf6 10 Be3 O-O 11 Qe2 Rad8 12 e5 Ng4 13 Bd2 d5 14 h3 Nh6 15 g4 Kh8 16 f5 exf5 17 Nxd5

17...Nd4 18 Nxd4 Bxd5 19 Nxf5 Nxf5 20 Rxf5 g6 21 Rff1 Ba8 22 Rxf7 c4 23 Rxf8+ Rxf8 24 Bc3 Qb6+ 25 d4 Qb7 26 Qh2 Qf3 27 White resigns.

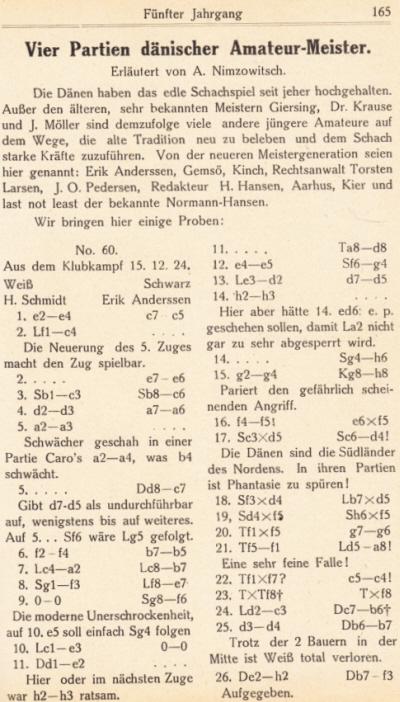

This game between H. Schmidt and Erik Andersen [sic] was published on page 165 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925 with annotations by Nimzowitsch:

Javier Asturiano Molina asks whether it is possible to identify the game by Caro to which Nimzowitsch refers in his note to White’s fifth move.

So far we have not found it. It may be mentioned that, in any case, the move 5 a4 had been seen in the 11th match-game between Löwenthal and Harrwitz in 1853 (see pages 368-370 of that year’s Chess Player’s Chronicle). As recorded on pages 340-341 of the same volume, the seventh match-game began 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 e6 3 Nc3 a6 4 a4 Ne7 5 d3 d5. The move 5 a3 had occurred two years previously (after 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 d3 e6 4 Nc3 a6) in Ranken v Hodges (fourth match-game in the London, 1851 Provincial Tournament). See pages 204-206 of Staunton’s volume on London, 1851.

(7850)

For 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4, see also C.N. 8482 above.

Regarding Raymond Keene’s coverage of exchange sacrifices by Black on c3 in the Sicilian Defence, see a brief article by Olimpiu G. Urcan.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.