Edward Winter

We learn with great regret of the death of Jeremy Silman in Los Angeles on 21 September 2023, at the age of 69.

***

As shown in a feature article of ours on the very best chess books, Jeremy Silman was a highly respected author, among whose works were The Amateur’s Mind, Silman’s Complete Endgame Course and How to Reassess Your Chess.

His interest in chess history is shown in the C.N. items below, which included a number of contributions from him.

***

Concerning Pal Benko My Life, Games and Compositions by P. Benko and J. Silman (Los Angeles, 2003) see our feature article on Pal Benko.

We are hopeful that a reader can help us find out more about an incident reported in C.N. 790 (see pages 119-120 and 263 of Chess Explorations), i.e. the claim that shortly before the Vienna, 1922 tournament Alekhine tried to kill himself.

On 27 June 1984 James J. Barrett (Buffalo, NY, USA) wrote to us:

‘Did you know that Alekhine once plunged a knife into his abdomen while in a hotel lobby, in the presence of his friend Edmond Lancel? I have never seen a reference to this episode in all the Alekhine material I have read.’

Mr Barrett subsequently provided particulars, i.e. an extract from Lancel’s article about Alekhine on pages 1152-1153 of the April 1946 issue of L’Echiquier Belge. Below is the relevant passage, in our translation:

‘Alekhine took a few days off to rest in Aachen, where I was staying. Since the beginning of the year, we had been together on several occasions. We spent the evening of his birthday together at the Hotel Corneliusbad. He confided in me, talked to me about his life and showed me pictures of people close to him. We played, as we often did, several training games in preparation for the important Vienna tournament, which was to take place from 13 November to 2 December. Around three o’clock in the morning, without any warning whatsoever, in the grand hall of the hotel which was deserted except for my partner and myself, Alekhine suddenly tried to commit suicide in a moment of despair by stabbing himself in the stomach, and fell unconscious at my feet. I alerted the people at the hotel; the director, doctor, ambulance and police were summoned. The situation appeared extremely serious, and Alekhine did not regain consciousness. However, thanks to the rapid and energetic intervention of those called, he came around and a few days later he had recovered. Nonetheless, this incident was significant, occurring as it did shortly before the Vienna tournament. I did my best to dissuade my old friend from participating, for I was sure that he would not do well. My efforts were in vain; he insisted on playing ...’

(3842)

Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) asks whether any further details are available regarding Edmond Lancel’s claim.

As reported in an endnote on page 263 of Chess Explorations, in C.N. 862 C.D. Robinson (Toronto, Canada) commented:

‘Alekhine is alleged to have stabbed himself about 3 a.m. after celebrating his birthday. The actual date would be either 20 October or 1 November, according to whether he kept his birthday on the Russian date of 19 October or the Western date of 31 October. This allows a maximum of 24 days in which to recover from a serious wound and to travel from Aachen to Vienna for a tournament beginning on 13 November ... Lancel is wrong when he claims that Vienna, 1922 was Alekhine’s worst result between Scheveningen, 1913 and Nottingham, 1936. The earlier limit should be Vilna, 1912 (the All-Russian Tournament).’

C.N. 1854 offered an excerpt from the reminiscences of Francisco José Pérez in the March 1989 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez (page 14). Regarding Alekhine he said:

‘While playing in a tournament in Sabadell in 1945, Alekhine said that he did not have the courage to commit suicide; his wife had written to him saying that she did not want to hear from him any more.’

(6127)

Jeremy Silman asks about the circumstances of Capablanca’s loss to Roy T. Black at New York in 1911 (a Sicilian Wing Gambit).

Contrary to appearances, the game was played, on 25 January 1911, in a serious event: the national tournament in New York. From page 50 of the March 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Capablanca lost only one game, in the fourth round, when he was opposed to R.T. Black, of Brooklyn. Against him, Capablanca, before he had really settled down to serious work, played a gambit variation of the Sicilian Defense, a course he had reason to regret. It was surprising to find Capablanca, after six games, with a score of 3½ to 2½, yet such was the case and it required six successive wins in the remaining rounds to enable him to get as close to Marshall as he did.’

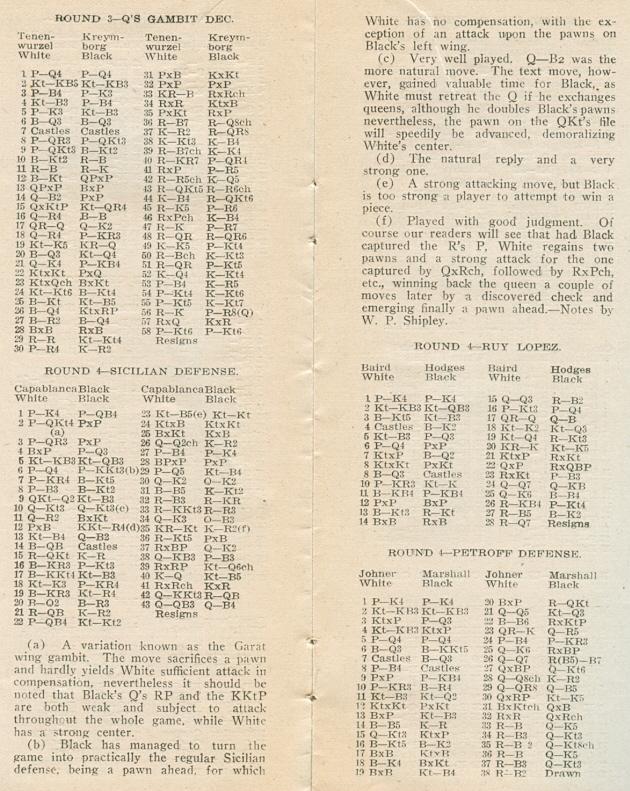

The same issue (pages 56-57) had the game against R.T. Black, with annotations by Walter Penn Shipley:

Among the few books to have annotated the game are Capablancas Verlustpartien by Fritz C. Görschen (Hamburg, 1976) and the first volume of the ‘Chess Stars’ anthology on Capablanca (Sofia, 1997).

The Cuban, for his part, gave this account towards the end of Chapter IV of My Chess Career (London, 1920):

‘In the winter of 1910-1911 I made another tour of the US. A tournament was arranged in New York, which I entered with the idea of practising for the coming tournament at San Sebastian. The New York tournament started in January. I rode on a train 27 hours straight from Indianapolis, the last city of my tournée, to New York. I arrived at nine in the morning and had to start at eleven the same day, and play every day thereafter. I was so fatigued that I played badly during the first part of the contest. Half of it was over and I was yet in fifth place, though the only opponent of real calibre was Marshall. I finally began to play better, and by winning five [six, in fact] consecutive games finished second to Marshall.’

(6239)

Jeremy Silman informs us that he has been studying the games of Gioacchino Greco (1600-circa 1634) with increasing admiration:

‘There are many games which show Greco toying with his hopelessly over-matched opponents, and one gains the impression that he was a master of tactics and of open games, and that he was so far beyond other players of his time that it was, in effect, a case of a grandmaster versus players rated between 1000 and 1800. Once in a while, Greco would face someone who could fight back, which allows us to see Greco’s positional skills. It is possible that some, or even all, of the games were fabricated, but even if they were inventions they still show a chess understanding centuries ahead of his time.

Here are two great examples (both of which will be used in my forthcoming new edition of How to Reassess Your Chess):

N.N. – Gioacchino Greco

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 c5 4 c3 Nc6 5 Nf3 Bd7 6 Be3 c4 7 b3 b5 8 a4 a6 9 axb5 axb5 10 Rxa8 Qxa8 11 bxc4

(Black has to recapture the pawn on c4. Either choice is playable, but one stands out above the other.) 11…dxc4 (Breaking the old “always capture towards the center” rule. This gives Black far more to work with than the pedestrian 11...bxc4. With 11...dxc4, Black creates a home on d5 for a knight, opens up the a8-h1 diagonal for his queen (and potentially for his light-squared bishop too) and, most importantly, creates a queen’s-side majority of pawns. This means that Black, whenever he chooses to do so, can make a passed pawn by ...b4.) 12 Be2 (12 d5 exd5 13 Qxd5 Qb8 is also fine for Black.) 12…Nge7 13 O-O Nd5

(Black, with his knight on d5 and his pawn majority ready to make a passed pawn (by ...b4) any time he wants, has an excellent position.)

Source: The Games of Greco by Professor Hoffmann (London, 1900), pages 79-81.

N.N. – Gioacchino Greco

1 e4 c5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 d6 4 Bc4 Nh6 5 O-O Bg4 6 c3 e6 7 h3 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Qd7 9 d3 O-O-O 10 f5 Ne5 11 Qe2 Nxc4 12 Bxh6 Na5 13 b4 Nc6 14 Bd2 exf5 15 exf5 f6 16 b5 Ne7 17 Qe6

(The queen has just leapt to e6, where it flexes its muscles and also dares Black to capture and give White a passed pawn on e6. But Greco sees beyond the hype and realizes that it is actually a severe weakness.) 17…Qxe6 18 fxe6 (The pawn is imposing here, but it turns out to be extremely vulnerable.) 18…Ng6 (Another way is 18...Re8 19 a4 Nd5 20 c4 Nc7.) 19 d4 d5 20 Be3 c4 21 Bc1 Re8 22 Re1 Bd6 23 a4 Nf8

(The pawn falls, leaving Black with an extra pawn and a winning position.)

Source: The Games of Greco by Professor Hoffmann (London, 1900), pages 92-93.

My impression is that Greco was further ahead of his contemporaries than any player who came after him. He was clearly of grandmaster strength at tactics, his openings were (for his time) cutting-edge, and his play in open positions was world-class. Yes, he took liberties which would not stand up against stronger opponents, but I think that he was well aware of his opponents’ failings and thus had little or nothing to worry about – he swung the bat freely in an effort to create classic mates and attacks that no doubt amused him.

He had solid positional skills too. In the first game above, his capture away from the center (11...dxc4) was very astute, and in the second game he was more than happy to play for the win of a pawn (although, even then, he ended up with a strong king’s-side attack).

Moving forward, I feel that Philidor may have been the best of his time, but other players were close (and Greco would have slaughtered everyone of Philidor’s day, including Philidor). Labourdonnais was extremely strong, but that was 200 years after Greco’s reign. Even so, in my opinion Greco would have given both Labourdonnais and Morphy a stern challenge. In the modern age (starting with Steinitz), Greco would have needed to pick up many new tricks to compete, but I think that talent like his would have blossomed in any period.

Greco was a man in an age of chess children. There never was, and never will be again, a player so far ahead of his time.’

(6320)

Our feature article Fischer’s Fury includes a quotation from Jeremy Silman’s ‘Inside Chess Online’ review of My 60 Memorable Games:

‘Mr Burgess, I don’t know where you learned this “standard” typesetting law, but any major publishing house in the United States would instantly fire any typesetter doing this kind of thing. A typesetter who butchers an author’s work to make his own job easier should find a new vocation.

… Burgess seems to be saying that the typesetter is the one responsible for all the textual changes (and then he says that this is perfectly all right). Nunn says that he didn’t really make any errors, and that his only job was to typeset the book! Dr Nunn, are you responsible for all the textual changes? Is Burgess? Who is? Do you think that such changes are justified? Can you honestly say that you wouldn’t mind if I made hundreds of textual changes to one of your books someday?

Quite frankly, I am tired of Mr Burgess, Dr Nunn and Batsford pointing out the errors they corrected … while simultaneously excusing themselves for the mess they made of everything else. Why not take a mature stand and simply admit that bad judgment was used and, hopefully, that it won’t happen again? We are not dealing with a government conspiracy here, gentlemen. Isn’t it time to come clean and put this nonsense behind you?’

C.N. 7875 gave a position from Alekhine v Nimzowitsch, San Remo, 1930, and we should like to know the origins of the term ‘Alekhine’s Gun’, which has been widely applied to a manoeuvre in that game.

For example, after 26 Qc1 Jeremy Silman wrote on pages 280-281 of How to Reassess Your Chess (Los Angeles, 1993):

‘The pressure White exerts on the file is crushing. After this game was played, this form of tripling on a file with both rooks in the lead became known as Alekhine’s Gun.’

In the periodicals of the time that we have checked, 26 Qc1 received no comment at all. When was the ‘Gun’ term first attached to it?

(7880)

Jeremy Silman informs us that he does not recall the provenance of the term ‘Alekhine’s Gun’, which, as mentioned, in C.N. 7880, he used on pages 280-281 of How to Reassess Your Chess (Los Angeles, 1993).

That remains our first sighting of ‘Alekhine’s Gun’ in print. Can readers find earlier occurrences?

(7914)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘I have found a reference to Alekhine in Russian sources. Fundamentos estratégicos del ajedrez edited by Yakob Estrin (Barcelona, 1985) has the following on page 24, in a chapter by B. Zlotnik (below the relevant diagram):

“Las piezas blancas están idealmente colocadas para penetrar en el campo enemigo. A esa manera de disponer la artillería se le suele dar el nombre de Alekhine, por ser típica del antiguo campeón mundial y sin duda también debido al gran efecto que produjo en una famosa partida jugada en San Remo, en 1930, entre Alekhine y Nimzowitsch.”

The Spanish book comprises only section two of the original work, Теория и практика шахматной игры (Moscow, 1984 [first edition: 1981]), where page 43 has this:

English translation of the marked passage:

“The white pieces are ideally situated for the invasion of the enemy camp. Such an arrangement of the heavy pieces is often called Alekhine’s/Alekhinian, probably on account of the famous game Alekhine v Nimzowitsch (San Remo, 1930).”’

(7972)

Jeremy Silman notes that pages 118-119 of Techniques of Positional Play by V. Bronznik and A. Terekhin (Alkmaar, 2013) discuss Blackburne v Rosenthal, Paris, 1878, in which this position arose:

The heading in the book is ‘Brute force: Blackburne’s battering ram’, and the authors comment regarding 23 R1c2 (which was followed by 23...Qd8 24 Qc1):

‘Blackburne brings all three major pieces on to the c-file – and the rooks belong in front of the queen.’

The earliest specimen of the manoeuvre that we can quote is Kennedy v Mayet, London, 1851 (see pages 35-38 of the tournament book):

The game continued 21...Rc5 22 a4 Rfc8 23 Rec1 R8c7 24 h3 Qc8.

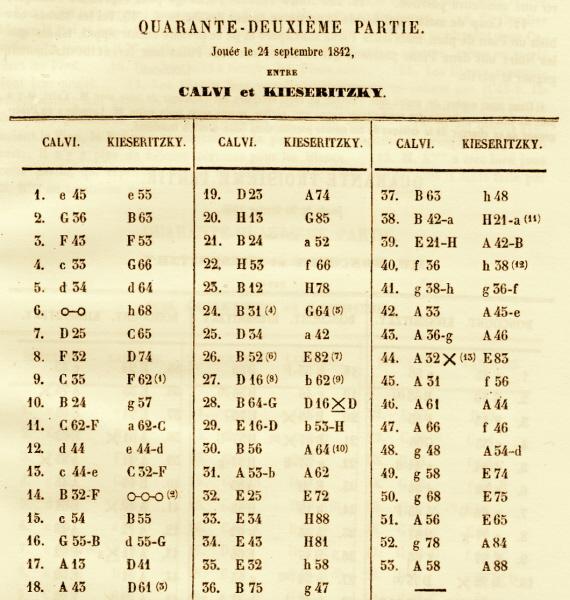

An earlier game in which the major pieces were tripled, though with the queen placed between the rooks, was Calvi v Kieseritzky, third match-game, Paris, 1842:

Play went 19 Qc2 Rd7 20 Rc1.

Below is the full score as given on page 39 of Kieseritzky’s book Cinquante parties jouées au Cercle des Echecs et au Café de la Régence (Paris, 1846):

(8625)

C.N. 6191 showed two portraits of Alekhine by Man Ray. Now, Jeremy Silman draws attention to a third photograph, apparently from the same time. The website dates it circa 1925, which seems to us less likely than the ‘circa 1928’ in the book mentioned in our earlier item, Man Ray’s Paris Portraits: 1921-39 by Timothy Baum (Washington, 1989).

(8363)

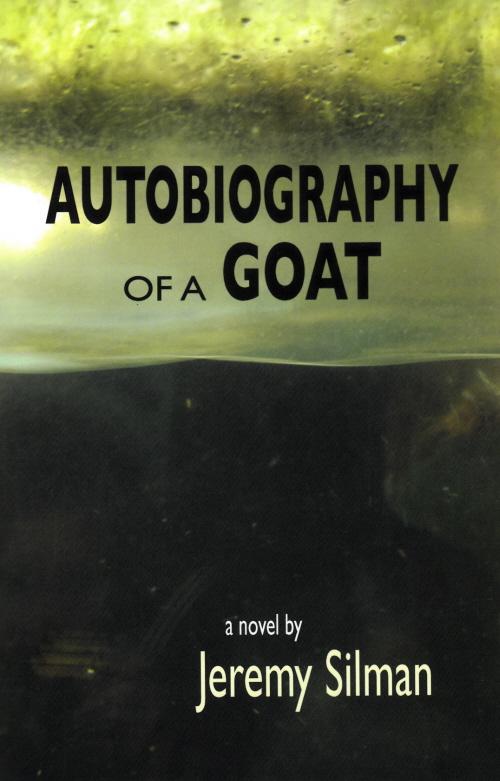

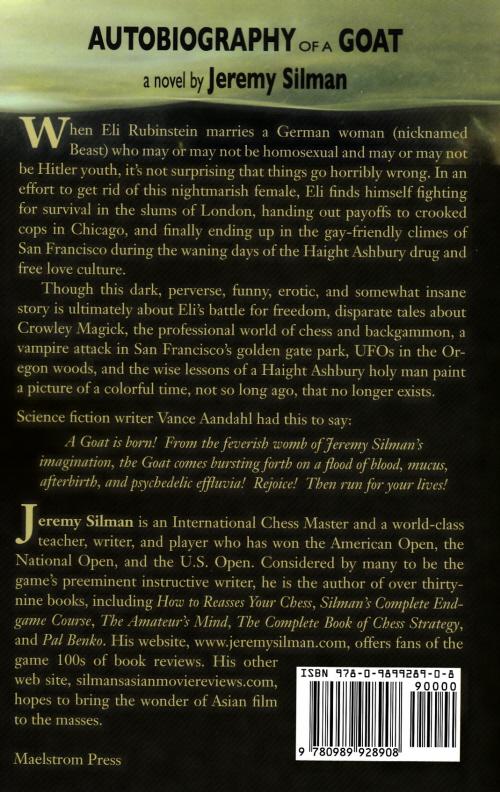

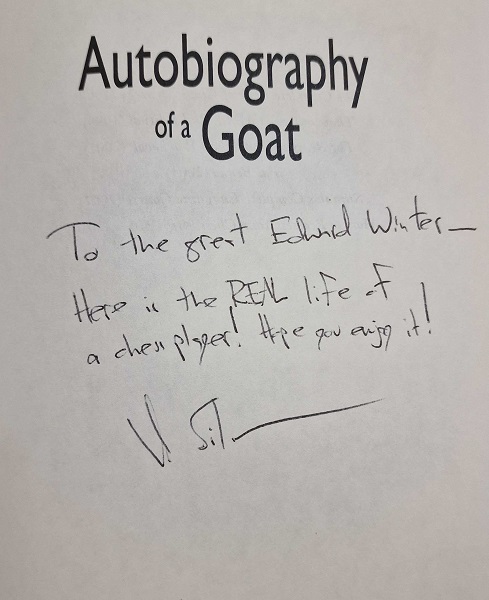

Chess authors often write fiction, but Jeremy Silman has done so intentionally with a novel, Autobiography of a Goat (Los Angeles, 2013):

(8526)

Jeremy Silman wishes to know the truth about suggestions that Alekhine was found drunk in a field during his 1935 world championship match against Euwe.

The Factfinder has an entry for ‘Alekhine, Alexander (alcohol)’, and further citations will be appreciated, after which all available documentation will be drawn together in a feature article. The word documentation is stressed; frequently elsewhere the subject is treated merely as good for a gossip and a giggle.

(8548)

Our subsequent feature article was Alekhine and Alcohol.

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) notes the title page of The Neo-Sveshnikov by Jeremy Silman (Moon Township, 1991):

(8874)

See Chess Diagrams.

Concerning the name ‘Jeremy B. Silman’, John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) informs us that the initial was used for personal reasons, and that ‘Jeremy David Alexander Silman’ was on his birth certificate.

See too The Origins of Chess.

On 24 May 2011 Jeremy Silman wrote to us:

‘Schiller is an ego-driven imbecile.’

Our ‘Silman inbox’ (130 e-mail messages) contains some blisteringly frank comments about, for instance, the ignorant public reaction that he often received to his chess.com articles. His remarks to us about chessplayers and writers were often similarly brutal, two notable exceptions being Yasser Seirawan and John Donaldson. Regarding the latter, for instance, Jeremy Silman wrote to us on 1 May 2011:

‘In general, I’m quite protective of fellow chess professionals. It’s not an easy life – no health insurance, little money, little respect from the public, and very little security as far as retirement goes. Of course, the patron saint of chess pros is John Donaldson, who always comes riding to the rescue when fellow chess players are in desperate need. It’s hard not to love John.’

Addition on 13 May 2025:

From an e-mail message to us from Jeremy Silman dated 9 May 2011:

‘Recently (a few days ago) on chess.com, several people (with no real names, so they were anonymous) created a forum within the larger website whose sole purpose was to attack me. They went berserk, saying that everyone (millions of members) needed to go to Amazon and give one star to all my books (even though most don’t have them), write fake super negative reviews, demand I get fired, etc. This went on ... seemingly non-stop, for three days and little was done about it. Anyone that dared say a good word about me was crushed by the madmen, and as they got more and more lathered up, they became more and more filled with Silman-hate.

These people would regularly write under my weekly Q&A column (for chess.com) nasty, very ignorant comments and, if I found them too disgusting (and if they had nothing to do with the article’s topic), I would delete their hate post. This finally turned them into killing machines, and they raved about the constitution and how they had the right to say anything they wished to say.

I explained to the site leaders (some very nice guys) that if this was happening to any other writer (Pogonina, Serper, or even Schiller, whom I’m not fond of) I would demand it be taken down and stopped, or I’d quit. Nobody deserves that. But I put up with it myself since the monsters wanted me to quit and I couldn’t bring myself to give them the pleasure of victory (they would have viewed it as such).

These things are traumatic and so uncalled for.’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.