Edward Winter

Bobby Fischer (see C.N. 9812 below)

Section 1: Predictions

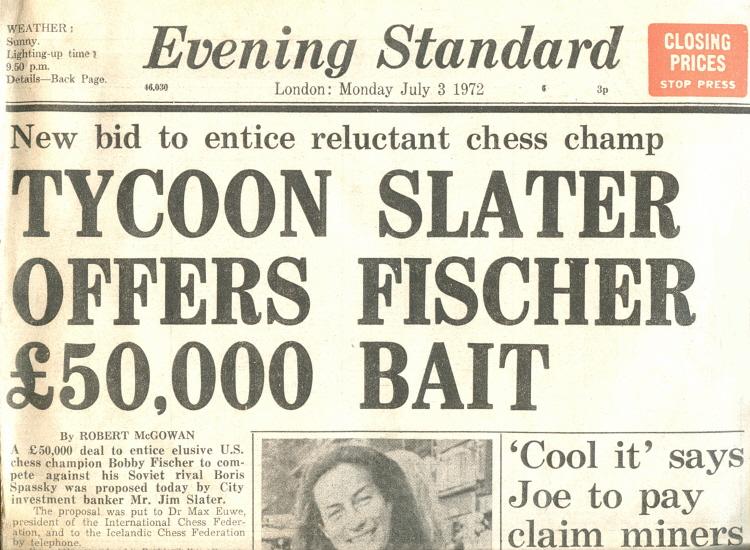

Section 2: James Slater

Section 3: Seconds and preparations

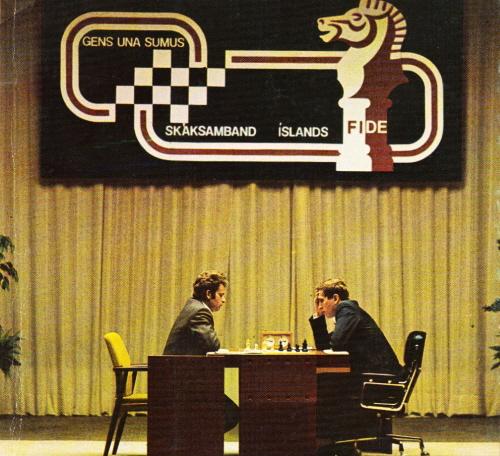

Section 4: Reykjavik

Section 5: Television and film footage

Section 6: 29...Bxh2 in the first match-game

Section 7: Press coverage

Section 8: Cartoons and comic strips

Section 9: Post-match

Section 10: Books on the match

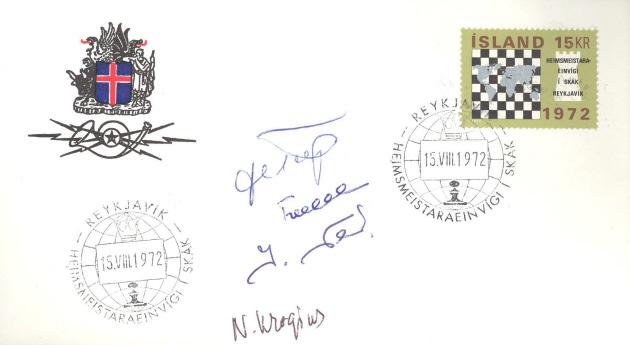

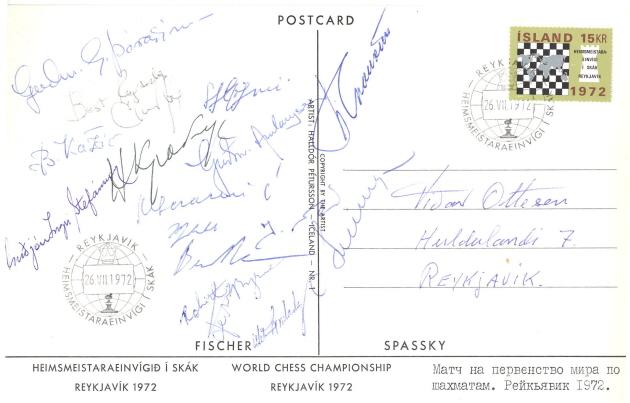

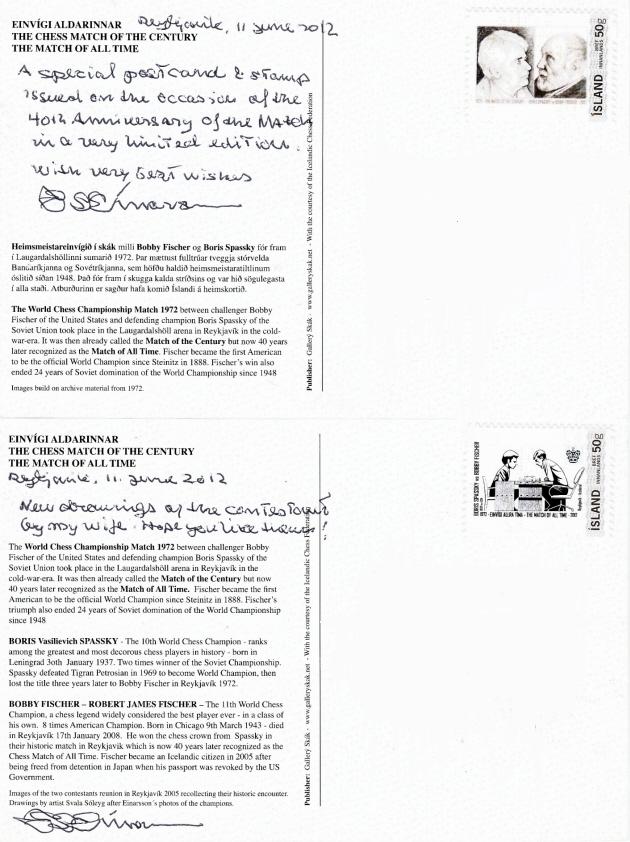

Section 11: Memorabilia

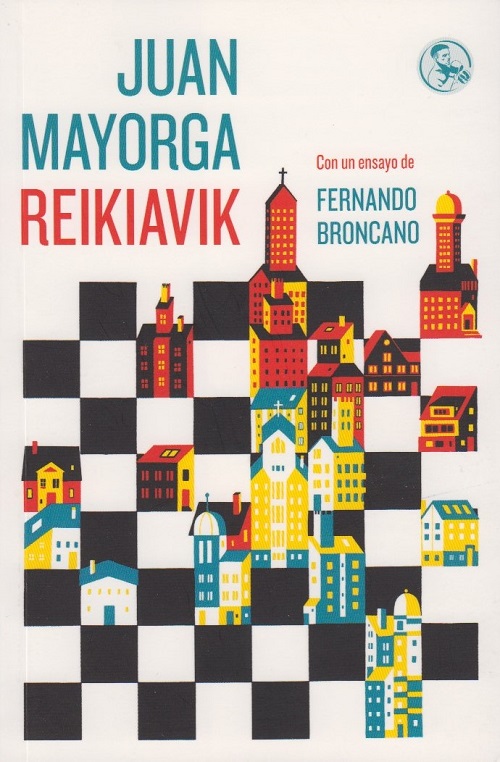

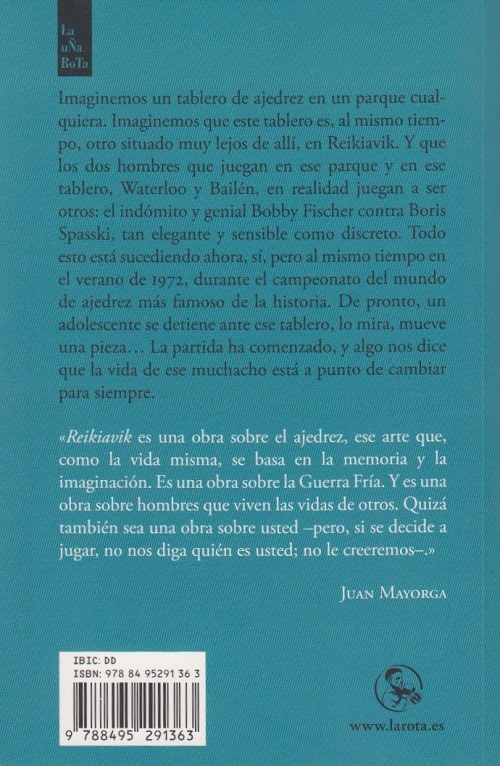

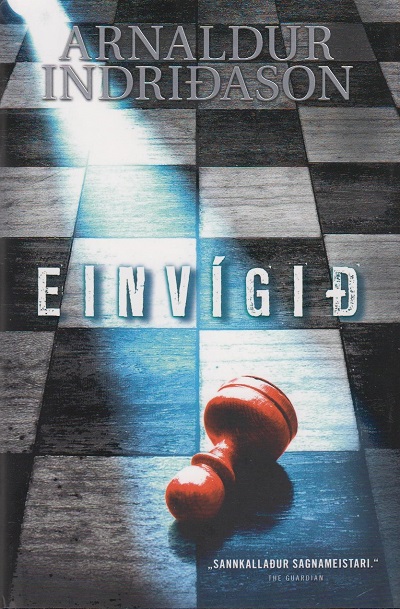

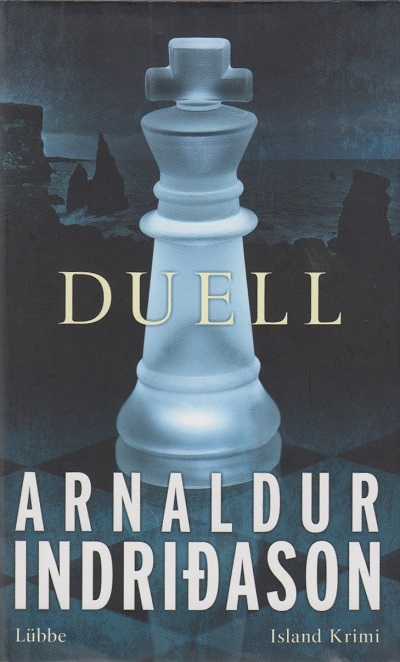

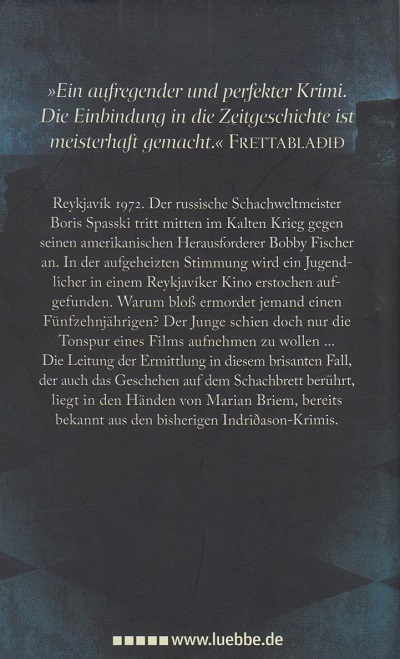

Section 12: Works of fiction

Section 13: Junk

The following appeared as C.N. 2737 (see page 205 of A Chess Omnibus):

‘An uncanny prediction by Robert Byrne on page 162 of the March 1972 CHESS:

“I believe Fischer will win. Would you like the score? 12½ to 8½! They will play 21 games.”

This was spot on, although Byrne’s next sentence was spot off:

“Fischer will be the world champion for the next 15 years.”’

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) now writes:

‘It sounds very good, but how much of a prediction is it? Byrne is simply saying that Fischer will win 4 games to 0, or 5-1, 6-2, 7-3 or any +4 score. The winning score of 12½ was not hard to fathom; only Botvinnik playing Tal had been ruthless enough to win the last game in a non-drawn title match since the War.’

Byrne was one of 26 respondents in the CHESS item on forecasts for the 1972 match. Many were non-committal, and the others were equally split as to whether the victor would be Spassky or Fischer. Only Byrne predicted a specific score. Three masters suggested in general terms that Fischer was certain to win: Donner, Mecking and Najdorf.

(5681)

In an article ‘Masters and Experts View the Match’ by Bill Goichberg on pages 409-410 of the July 1972 Chess Life & Review several respondents (Herbert Seidman, Harry Borochow, Joseph Platz and John N. Jacobs) predicted that Fischer would defeat Spassky 12½-8½.

Reuben Fine’s prediction, Fischer by 12½-7½, was accompanied by the comment:

‘The odds are now (March) 4 to 2 that the Russians will dodge the match, using it as a political football.’

On page 15 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Fine wrote:

‘The road was now clear for the final match with Spassky. Bobby was the favorite. I predicted that he would win 12½ to 8½. Others came up with other figures.’

(6257)

Jonathan Berry (Nanaimo, BC, Canada) quotes from page 21 of the September 1972 issue of Chess Canada:

‘Chess Canada’s Spassky-Fischer Contest Winners

Thirteen correct predictions were received by Chess Canada and each of these will receive a credit for $50 worth of books. The people correctly predicting a score of 12½-8½ were H. Winston, M. Mares, R. Eberlein, I. Zalys, C. Dwyer, P. Arens, R. Joho, J. Musumeci, J. Sember, H. Brodie, W. Browne, J. Burstow and the UBC Chess Club.

The final score of 12½-8½ was predicted 13 times, as was 12½-9½. The next most common prediction was 12½-10½ with 7. Fifty-seven entrants expected a Fischer win while ten predicted Spassky and only three expected a tie.’

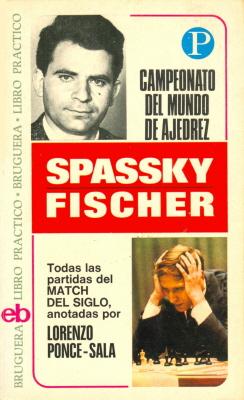

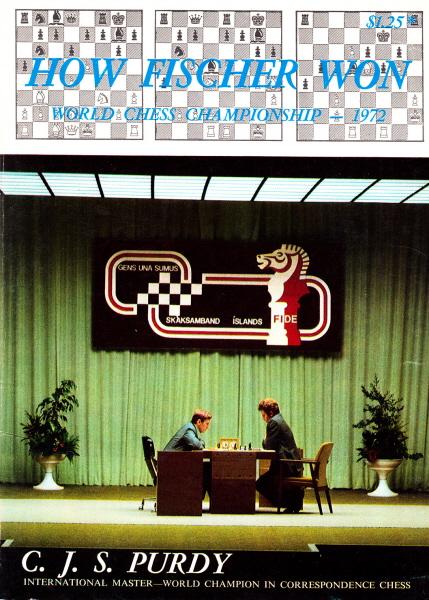

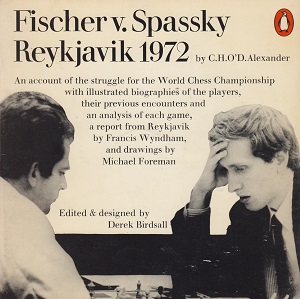

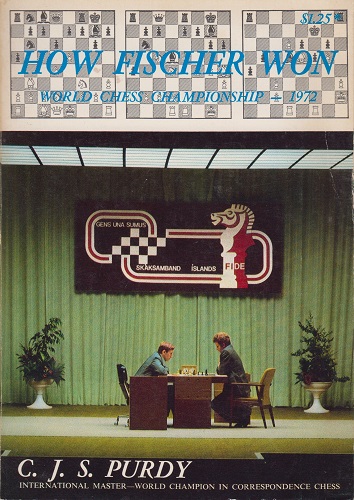

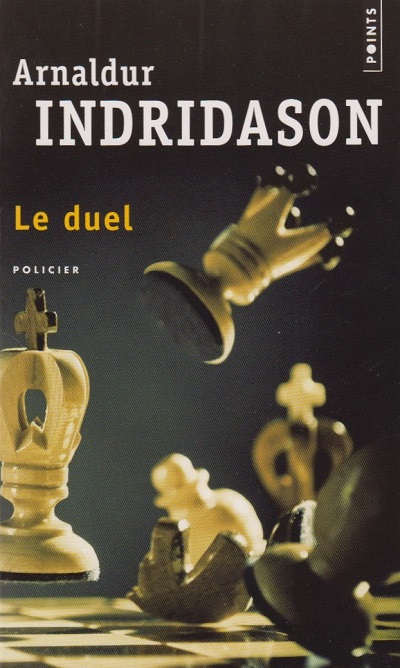

We wonder in passing whether an authoritative tally has been established of books on the 1972 match. Below, taken at random, is one of the many:

(6262)

On page 410 of the July 1972 Chess Life & Review Joseph Platz was one of a stream of pundits who dispensed opinions on the Reykjavik match. Predicting a final score of 12½-8½, he commented:

‘Fischer’s knowledge of the game, his natural ability, his will to win every game, even when he has no advantage, will carry him to victory. ... Spassky is under greater pressure ... what will happen to him if he loses the match? ... Fischer will fight with confidence; he is under obligation to nobody.’ (Ellipses in the original.)

(10241)

C.N. 10241 also reported Platz’s prediction as to how Fischer would die.

For Leonard Barden’s account of the episode, see pages 26-27 of CHESS, November 1997.

(5198)

Roy Henock (Eureka, CA, USA) notes a statement at the Huffington Post website: ‘In 1972, Kavalek was Bobby Fischer’s second in his world championship match against Boris Spassky in Reykjavik.’

In terms of presence in Iceland, is it possible to find, or compile, a comprehensive list of seconds, attendants, representatives and officials, with respect to both Fischer and Spassky?

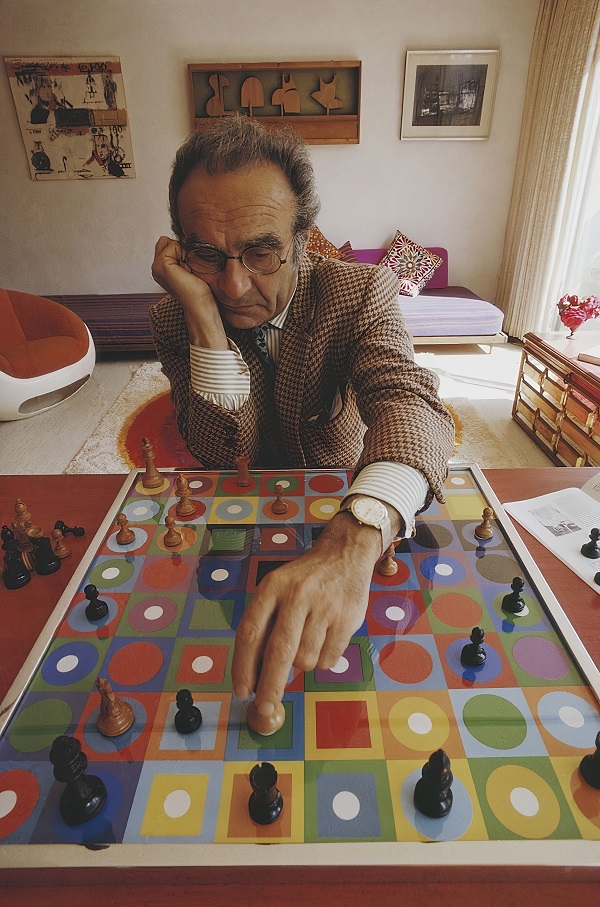

From the front cover of El match del siglo by L.Pachman (Barcelona, 1972)

(8125)

From Lubomir Kavalek (Reston, VA, USA):

‘I wrote about my role during the 1972 world championship match in an article on pages 60-68 of the 6/2012 New in Chess. It includes transcripts of two interviews with Fischer.

In brief, I took over the second’s duties during the adjournment of the 13th game after Fischer sent Lombardy away. I was analysing with Fischer alone until the end of the match. We also spent time walking together, swimming and bowling. To my knowledge, there were only three other people (Bill Lombardy, Fred Cramer and Brad Darrach) who had daily contact with Fischer away from the playing hall. I was also busy reporting for the Voice of America. I know that there was a list of the invitees to the closing ceremony; since Lombardy was the official second, I was listed as “Bobby Fischer’s coach – bowling”, although I bowled only three times in my life. However, it enabled my wife and me to sit at the same table with Bobby and Boris Spassky.’

We add a brief excerpt from Lubomir Kavalek’s above-mentioned article in New in Chess (page 66):

‘It was during this game [the 13th] that I started working with Bobby on the adjournment games after he sent his official second, Bill Lombardy, away from his suite. Bobby and Bill were a great pair, but during that night they turned into two strong personalities with two different opinions. The tension was resolved by Lombardy’s sneeze. “I don’t want to get your cold, Bill”, Bobby said and added he wanted to work with me. Bill left quietly.

From that moment on, I analysed just with Bobby till the end of the match.’

(8135)

Further to C.N. 8135, Aðalsteinn Thorarensen (Reykjavik) asks why Sæmundur Pálsson was not also mentioned, and we have put the question to Lubomir Kavalek. His reply:

‘I was more concerned about the chess experts around Bobby Fischer, and I did not think of Sæmi Pálsson. He was more visible after the match. I did not see him driving with us to the US Army base in Keflavík, or during our midnight swims and walks, and he was not in Fischer’s room during our analysis. Nor was he in Fischer’s villa during our interview after the match, although this does not mean that he was not around. I did notice the Life photographer Harry Benson, who showed up regularly while he was on the island.’

(10451)

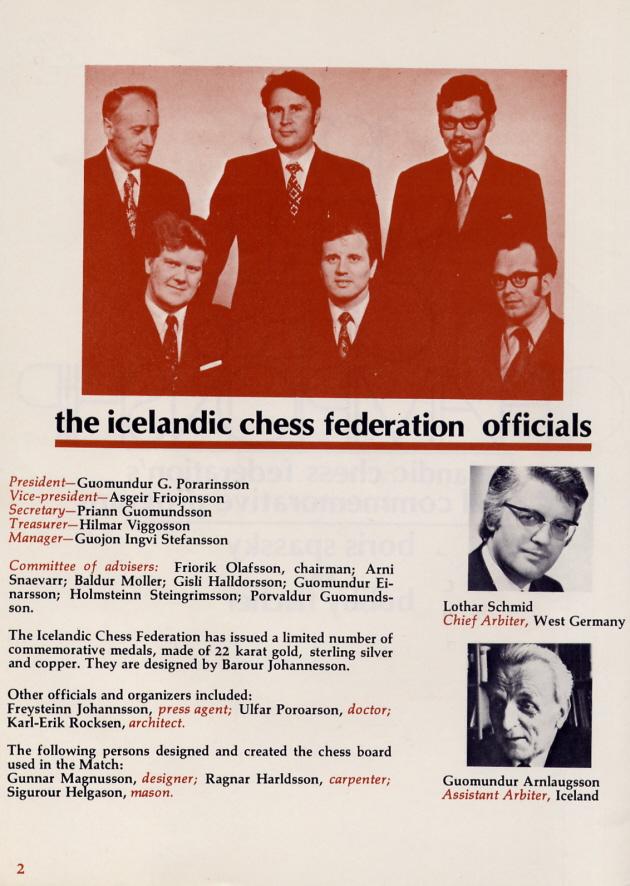

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) forwards page 2 of the Icelandic Chess Federation’s Commemorative Programme (New York, 1972):

(8136)

From Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA):

‘You refer to Kavalek’s role as a second, and his correspondence with you includes an important detail:

“To my knowledge, there were only three other people (Bill Lombardy, Fred Cramer and Brad Darrach) who had daily contact with Fischer away from the playing hall.”

Your article adds this excerpt from Kavalek’s article in the 6/2012 issue of New in Chess:

“It was during this game [the 13th] that I started working with Bobby on the adjournment games after he sent his official second, Bill Lombardy, away from his suite. Bobby and Bill were a great pair, but during that night they turned into two strong personalities with two different opinions. The tension was resolved by Lombardy’s sneeze. ‘I don’t want to get your cold, Bill’, Bobby said and added he wanted to work with me. Bill left quietly.

From that moment on, I analysed just with Bobby till the end of the match.”

Compare that account with Darrach’s gossipy version on pages 219-220 of Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World:

“Bobby meanwhile was having a personnel problem. After six weeks of trying to pull as a team, Bobby and Lombardy had developed halter sores. During dinner, Lombardy sneezed a few times; Bobby made a five-act drama of the incident. ‘You got a cold, Bill! You know I can’t afford to catch a cold now!’ Half an hour later, when Lombardy arrived in Bobby’s suite to resume analysis, he found grandmaster Lubomir Kavalek across the board from Bobby.

‘Bill, you go analyze somewhere else’, Bobby said carelessly. ‘I want to work with Lubosh.’ As Lombardy left, Bobby sat looking after him. ‘You know’, he said, ‘I think Bill is a vicious person.’

Though only the inner circle was aware of it, Bobby worked with Kavalek from the 13th game forward more than he worked with Lombardy.”

Lombardy alludes to the situation on pages 219-220 of Understanding Chess (Milford, 2011):

“Suffice to say, I was the only person on the intimate inside during that Match of the Century. I chose to say very little because I do not delight in satisfying idle curiosity! As for my ‘uselessness’ on the technical side of chess at Reykjavik, let me point out that there were 14 adjourned games. Bobby and I worked together on those adjourned positions without making a single technical error! Beyond that, I bested the Soviet team psychology, even though that team had a so-called professional psychologist. For little remuneration, I dedicated my services in the Icelandic capital to guarantee that Bobby followed through and finished the match victoriously.”’

(10310)

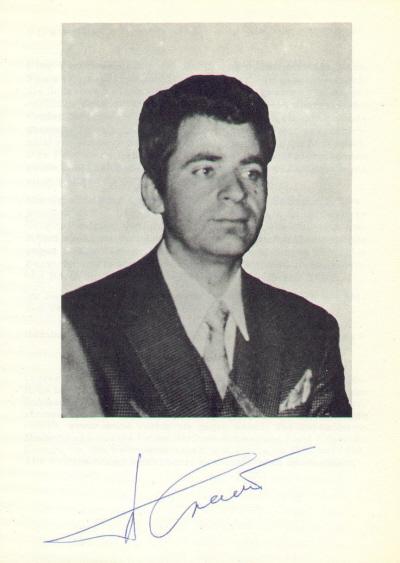

The illustration below shows Spassky’s signature on our copy of the Weltgeschichte des Schachs collection of his games:

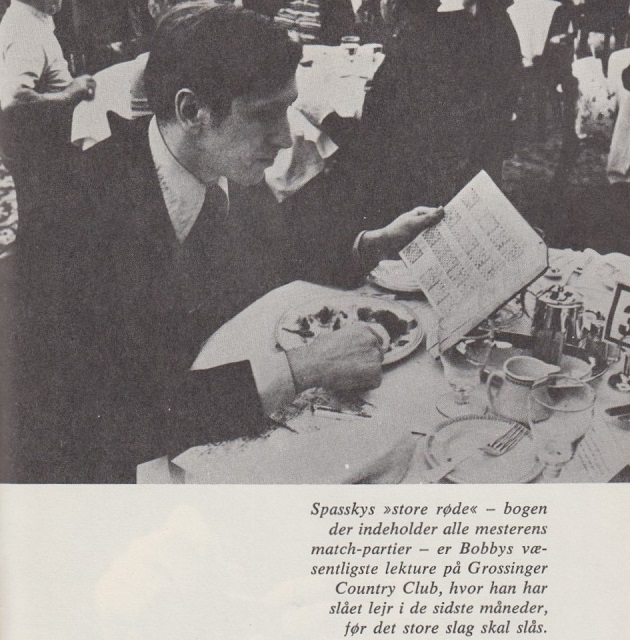

This is the famous ‘red book’ so often mentioned at the time of the 1972 world championship match. The opening titles of the film Searching for Bobby Fischer include footage of Fischer studying it, and we note that the game he was analysing is identifiable as Spassky v Langeweg, Sochi, 1967.

(2909)

Regarding the many references in the press to Fischer’s red book on Spassky (including confusion over the Wildhagen volume on Spassky and Robert Wade’s research for Fischer), see C.N.s 8962, 9167, 10677, 10682, 10686 and 10808.

Two images from C.N. 8969:

From page 189 of Bobby Fischers vej til VM by Jens Enevoldsen (Copenhagen, 1972)

A ‘secret’ match between Spassky and Karpov, was mentioned by the latter in an interview with Irwin Fisk posted by ChessBase on 2 March 2015:

‘I.F.: Spassky was in preparation to play Fischer for the world championship. Had you played Spassky?

A.K.: Yes, I played a training match with Spassky. He asked me to play training games, but we played only one game. Spassky won this game even though he had a lost position, but I made a stupid mistake, and after this suddenly Spassky said he didn’t want to continue this training match, so maybe he was happy he beat me in that game.

I.F.: Where was this game played?

A.K.: We were near Moscow.’

A similar, though more detailed, account is on pages 98-99 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1990):

‘Toward the end of the camp, Spassky, wishing to check his form, decided to play several games with me. In the first game, he selected the Ruy López. I played White and quickly gained a winning position. All I had to do was hold on to it for a little while longer, but, weary from the previous inactivity and irritated by how I was being treated, I decided to show off and embarked upon unnecessary tactical complexities. This gave Spassky a chance to display his customary resourcefulness. I should have regrouped in time, changed the arrangement, and played to at least hold on to what remained. But I already realized my lead was receding, and I overplayed and lost. Spassky liked this game. He decided that his form was superior and there was no reason to continue checking it. My participation in his final prematch training was virtually limited to this one game.’

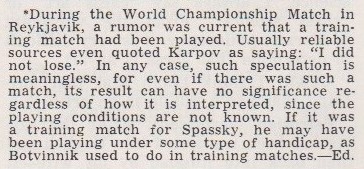

On page 8 of the September 1989 Chess Life A. Soltis disseminated a different version:

‘In some instances, no details about a match are ever disclosed. Or a smidgen of information surfaces, such as after the 1972 world championship match, when Anatoly Karpov confirmed the rumors that he had played a match to help prepare Boris Spassky for the challenge of Bobby Fischer. All Karpov would say then about the result was “I did not lose”.’

A similar text appeared on page 148 of Soltis’s book Karl Marx Plays Chess (New York, 1991), but in neither case did he offer the reader any source. It is possible that he was relying on a mere rumour published, as an editorial end-note, on page 70 of the February 1973 Chess Life & Review:

(9361)

Comments by Bobby Fischer in the article ‘“This little thing between me and Spassky” – Bobby Fischer talks to James Burke’ on pages 51-52 of The Listener, 13 July 1972, further to a BBC-2 television programme broadcast at the beginning of the month:

‘I think I’ve been the best since I was about 18 or 19 – somewhere around 1962. I felt I had the talent even before I played the game. I just was always good at games. I like to keep taking on all the top players to really prove that I am the best player in the world today, so that when they go home that night they can’t kid themselves that they’re so hot. And so this is where it’s at, the apex of my whole life, taking on this Spassky. This is really the big match. This is for everything. This is for the title. If I don’t win, it’s not going to be easy to get up to again. This little thing between me and Spassky, it’s a microcosm of the whole world political situation. They always suggest that the two world leaders should fight it out hand to hand, and this is the kind of thing that we’re doing – not with bombs but battling it out over the board.’

(Asked whether it was arrogant of Fischer to consider himself the best chessplayer.) ‘If it’s true then it isn’t arrogant.’

(On his prospects against Spassky.) ‘It’s not 100 per cent, but it wasn’t 100 per cent that I was going to beat Taimanov or Larsen or Petrosian. I think I am definitely the heavy favourite according to all past results.’

(In reply to a question on the most important thing about winning the world title.) ‘I guess knowing that other people regard me as the Champion. I’ve felt all along that I’ve been the best so I’m not proving that much to myself any more. I’d like to prove it to myself as well, but especially to the general public. I’d like to show the Russians too. That’s what I’d enjoy the most about winning the title – reading the Russian magazines, what they’d say about it. Either they’re going to say nothing or they’re going to have some involved nonsensical explanation.’

(Did he resent the Russian domination of chess over recent decades?) ‘When I first started playing chess, to me the Russians were heroes, and they still are as chessplayers. I used to study all their literature; most of the first books I read were Russian chess books. But the first time the Russians ever mentioned me – I was 13 – they said: there’s this talented young American player. And they showed this famous game I’d won against Donald Byrne. They showed the game, but on top of the game they said he’s a very fine young player, but all this publicity he’s having will surely do damage to his character. And sure enough, from then on they started attacking my character. They’d never even met me, or knew anything about me. So this kind of attitude really turned me off. They have the title, and the title belongs to them in perpetuity because it’s theirs – that’s their attitude. They don’t have a sporting attitude about it. Their attitude should be: he’s the best, he should have the title. They don’t believe in giving foreigners a chance to play for the title.’

(On his early interest in chess.) ‘I just found that I had more of a feel for the game, more of a knack for winning, than others had. I liked games: I was playing a lot of board games at home. We had Pachisi, Monopoly and all these board games, Chinese chequers and what not, but I kept hearing the hardest game was chess, so I finally persuaded my mother to give me that. They thought that it would be too advanced for me, but they finally got me a set, and that is the game that I concentrated on from then on. When I was playing these other games they were too simple. There was something that didn’t turn me on about games like Chinese chequers.

I played a little with my sister, but she wasn’t too interested, so then I started playing games with myself. I would make the white moves and the black moves, and then I would just play through the whole game. My mother started to get worried that it wasn’t too healthy, playing chess by myself all the time, so she got me some opponents, local kids. I started getting lessons from a player in the Brooklyn Chess Club, and that is when I started to advance. I was lucky: he taught me an awful lot of things. I don’t think it would be possible to have a better teacher. We worked together for several years. I was giving him about a dollar a lesson, one a week.

When I was 16 I wanted to play chess all the time. All these invitations kept coming in to travel around and to make money. I’d had enough and I didn’t particularly like high school anyway. I wasn’t really learning that much, and I felt I could learn on my own.’

(Asked whether most of his friends are from the chess world.) ‘I think just about all of them. I have a few peripheral friends here and there that don’t play, but I don’t see them too much. I just don’t seem to have too much communication with non-chessplayers. It’s a strange thing.’

(In reply to the remark ‘It seems to be a game which demands that you live almost a hermit’s life.’) ‘That’s true. If you start partying around, it just doesn’t go. I like to meet people but I don’t like to meet 80 people at a shot.’

(‘You have been said to be among the most particular, the most perfectionist of players in things like light and noise and distraction during the game. Yet, to the outsider, you seem to be someone who concentrates so greatly that that kind of thing might not matter.’) ‘It does matter, if it really gets annoying. I think I have pretty good powers of concentration, but I remember I once played, I think it was in West Berlin, and there was this guy with his head right over the board. That’s the kind of thing I’ve had to put up with. Another time I was playing in Oakland in the States, and this guy whispers a move in my ear. Things like this are not really conducive to high-class play.’

(Could a successful fight against Spassky be rather an anti-climax?) ‘After I get the title it’s going to be a lot easier. I know it’s a dangerous way to think, but I will be able to ease up a little bit.’

(‘Is there anybody else in sight that you think could topple you afterwards?’) ‘Possibly, eventually. There are a lot of talented players in the West. But I think that if you keep yourself in good shape physically, and you keep in love with the game and keep studying, you should be a top player till you’re in your 60s.’

(‘Don’t you ever worry that concentration on just one side of your character might prove to have been a mistake?’) ‘I try to broaden myself. I read quite a bit. But it is a problem, because you’re kind of out of touch with real life, being a chessplayer – not having to go to work and deal with people on that level. I’ve thought of giving it up off and on, but I always considered: what else could I do?’

(9268)

On 30 April 2025 Ryan Paulis (Amsterdam) informed us that the BBC Archive has made the programme available on YouTube.

As shown below, in the opening titles and the Radio Times billing the preposition was ‘with’, whereas ‘between’ was used in the accompanying Listener article mentioned earlier.

At the same time on 2 July 1972, BBC-1 broadcast Omnibus: Groucho Marx and Frank Muir. In his television review column on pages 26-27 of The Listener, 6 July 1972 Clive James wrote:

‘Frank Muir and Groucho Marx unforgivably clashed with Spassky and Bobby Fischer on the two BBC channels. Button-punching only resulted in Frank Muir asking Bobby Fischer questions about his film career. There was nothing for it but to go to bed with a book of end-games and dream through a long night in Capablanca. Groucho threatens White Queen, played by Margaret Dumont.’

From the first paragraph of Arthur Koestler’s introduction (page 7) to Fischer v Spassky by H. Golombek (London, 1973):

‘In the prehistoric days before the great match started and this book was written, I wrote in the Sunday Times: “Chess is a game too noble to be left to the chess-players”.’

The article in question appeared on pages 33-34 of the 2 July 1972 issue of the newspaper and was reproduced on pages 206-214 of Koestler’s anthology The Heel of Achilles (New York, 1974). The sentiments were, however, expressed tentatively:

‘The haggling about the venue and the revenue, the political invectives and insinuations, made one almost feel that chess is a game too noble to be left to the chess-players.’

(6511)

A further article by Koestler (on pages 33-34 of the Sunday Times, 3 September 1972) is notable for describing Fischer as a ‘mimophant’:

Contrary to occasional claims, Koestler had coined the term many years before he applied it to Fischer. See this Stack Exchange page.

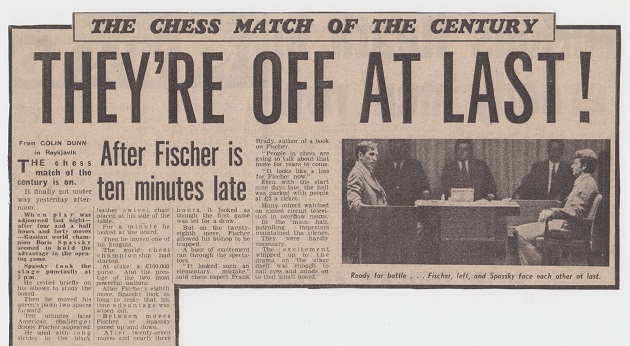

Greg Delaney (Little Chute, WI, USA) mentions the third game of the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match and asks for information about other chess games for the world championship which were not played in public. With readers’ assistance we should like to draw up a list, with details of the exact circumstances in each case.

Regarding the third match-game in Reykjavik, Frank Brady wrote on pages 249-250 of Profile of a Prodigy (New York, 1973):

‘The temporary playing room, located on the second floor of the stadium, above and to the rear of the stage, was a large, breezy, green-carpeted affair, used normally for table-tennis tournaments. Police guards were placed at the stairways to prevent anyone from reaching the room and disturbing the players. One unmanned, noiseless closed-circuit television camera, looking not unlike a spindly robot, was positioned about ten feet from the board.

During the game, I was in a small room about 20 feet away from the players, doing a remote broadcast for ABC’s Wide World of Sports, following the action on a soundless closed-circuit monitor and using an open telephone line to New York.’

(8667)

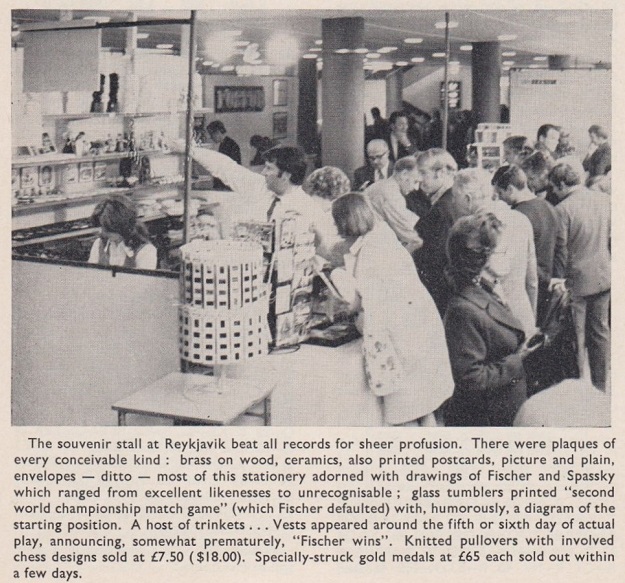

Given the number of journalists present during the Spassky v Fischer world championship match, chess magazines of the time had surprisingly few photographs of the general chess scene in Reykjavik, as opposed to pictures of the champion and challenger. One was on page 5 of CHESS, October 1972:

(9162)

Aðalsteinn Thorarensen has sent us a pair of Icelandic Chess Federation links (one and two) [broken links] including a rich selection of photographs taken during the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match.

(9769)

We are struck by how often photographs of the pre-game handshake show both players avoiding eye contact. An example, taken at random, comes from the plate section of International Championship Chess by B. Kažić (London, 1974):

(6880)

Michael Syngros (Amarousion, Greece) has updated his catalogue of ‘Chess literature in Hellenic (original or translations) and books by Hellenic authors in other languages’ and kindly authorizes us to make it available here.

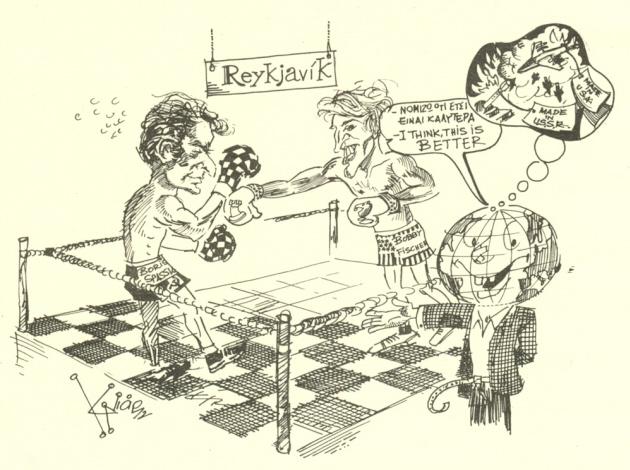

This illustration comes from the multilingual cartoon book Η ζωή μας είναι σκάκι by Κώστα Νιάρχου/Costas Niarchos (Athens, 1972).

(7037)

Ian Tregillis (Santa Fe, NM, USA) has been reviewing accounts of the contact between Bobby Fischer and Henry Kissinger in connection with the Spassky v Fischer match:

‘Kissinger himself, in the transcript of a telephone conversation with Jerry Schecter of Time on 21 July 1972, stated:

“I made only one call. I made it the day the parts [sic – departure?] for Iceland was in doubt and you know I did it as sort of being interested in chess.”

This suggests a call placed during Fischer’s stay in the Saidy household, which was approximately 30 June-3 July 1972. Kissinger’s conversation with Schecter took place roughly between games five and six of the match.

The following was the opening paragraph of an article ‘The Battle of the Brains’ by Ray Kennedy on page 32 of Time, 31 July 1972 (C.N. 5559):

From page 233 of Profile of a Prodigy by Frank Brady (New York, 1973), in connection with Fischer’s eventual decision to leave for Iceland:

“Later, it was learned that Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s presidential adviser, had called Fischer and appealed to him to play to avoid insulting the Icelandic nation.”

On page 184 of Endgame (New York, 2011) Brady wrote that Anthony Saidy himself answered the telephone when Kissinger's secretary called to set up a conversation with Fischer. Brady’s endnotes (page 358) cite a telegram from the American embassy in Reykjavik to the US Department of State, seeking White House assistance in having Fischer leave for Iceland. On page 184 Brady included the famous line allegedly spoken by Kissinger:

“This is the worst chessplayer in the world calling the best chessplayer in the world.”

In autumn 2017 I corresponded with Carla Braswell, an archivist at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, where many of Kissinger’s telephone transcripts of the period are kept. Dr Braswell searched all records for July 1972 and found no mention of Fischer. She stated that it was possible, although in her opinion unlikely, that the transcript exists in Kissinger’s donated papers at either Yale University or the Library of Congress. That remains to be verified. She also pointed out that not all of Kissinger’s calls were recorded and transcribed, but the omission strikes me as peculiar, because that call to Fischer appears to have taken place after another call by Kissinger for which a transcript does exist: a conversation with David Frost. A publicly known transcript corroborates the Kissinger/Frost call at 10.45 on 3 July 1972. In addition, the archivists at the Nixon Library provided me with an unredacted version.

In that conversation with David Frost, Kissinger said, “I’ll do it”. That was only a few hours before Fischer was due to catch an overnight flight to Reykjavik.

Later, in the wake of Fischer’s forfeiture of the second match-game, matters become even cloudier.

From page 248 of Profile of a Prodigy:

“Fischer began receiving letters and cables – thousands according to Cramer – urging him to continue the match, and presidential adviser Henry Kissinger called him from Washington [my emphasis] to appeal to his patriotic interests in playing for the United States.”

A statement by Fred Cramer dated 17 July 1972 was reported briefly on page 21 of the New York Times the following day (“Kissinger Phone Call To Fischer Disclosed”). The Times item, which had a Reykjavik byline, suggested that a call had been made by Kissinger to Fischer in the Icelandic capital:

“Fred Cramer, a spokesman for Bobby Fischer, said today that Henry L. [sic] Kissinger had telephoned the American chess star here.

Mr Cramer, a vice president of the United States Chess Federation, would give no details of the call. He would not say when it had been made or what had been said.

It is believed, however, that Mr Kissinger, President Nixon’s closest adviser on foreign policy, had urged Fischer – who had threatened to walk out on the world championship chess match with the titleholder, Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union, to continue with the match.”

Page 194 of Endgame states that in the wake of Fischer’s forfeiture of the second game of the match, and his implied threat to abandon the match, “... Henry Kissinger called him once again, this time from California [again, emphasis mine] ...”

Were there definitely two calls from Kissinger to Fischer, and what more is known for certain?’

Finally for now, in the 1972 bound volume of Chess Life & Review we note two references to Henry Kissinger:

‘Slater announced that he was personally doubling the $125,000 purse. A certain Kissinger from the White House phoned – he would call again in a later crisis.’ (Anthony Saidy, November issue, page 679.)

‘With the score 2-0 against him, nobody expected Bobby to continue the match which he had been so reluctant to enter in the first place. But a massive telegram campaign, a phone call from presidential advisor Henry Kissinger, and redoubled efforts by his friends and advisors here [in Reykjavik], made him change his mind and cancel his plane reservations home.’ (Robert Byrne, September issue, page 537.)

(10958)

The exact reference for the above-mentioned transcript of the telephone conversation between Henry Kissinger and David Frost: Kissinger-Frost Telcon; July 3, 1972; folder July 3-9, 1972; box 15; National Security Council Files: Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversation Transcripts (Telcons); Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Yorba Linda, CA.

Serin Marshall (Brooklyn, NY, USA) asks whether any recordings have survived of Shelby Lyman’s television programmes on the 1972 world championship match.

(6464)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points out a series of links to film coverage of the 1972 world championship match.

(9391)

Douglas Stidham (Austin, TX, USA) asks how much of the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match was filmed by Chester Fox, and where the footage is today. Such questions are often asked, but we have found no definitive answer. Can readers assist?

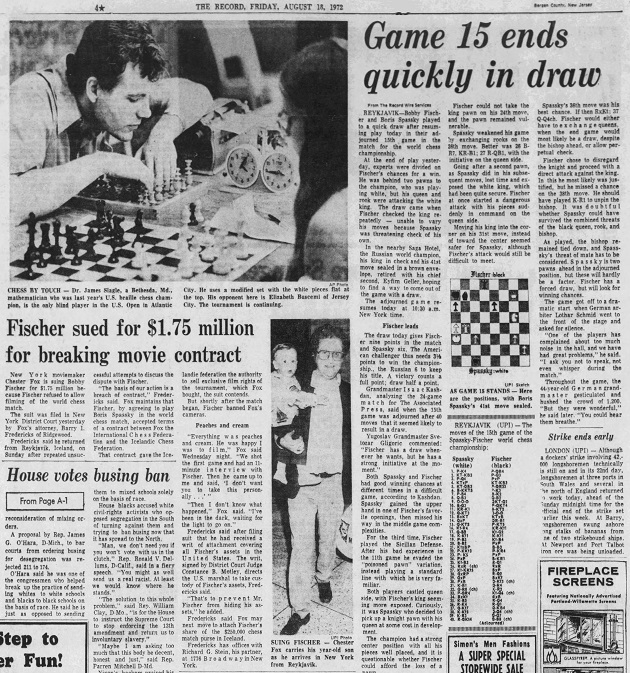

From page A-6 of the Record (Bergen County, NJ, USA), 18 August 1972:

Lesser-known information about Chester Fox in Reykjavik is available at the Icelandic website Tímarit.is.

(11738)

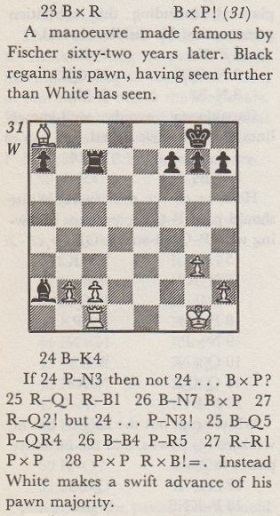

This position is from a game between Capablanca (Black) and Juan Corzo in Havana on 21 July 1909. It was published on page 197 of the American Chess Bulletin, September 1909 and was included on pages 37-38 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975). Page 199 gave as the source the Cuban newspaper Diario de la Marina, 22 July 1909.

From page 38 of The Unknown Capablanca:

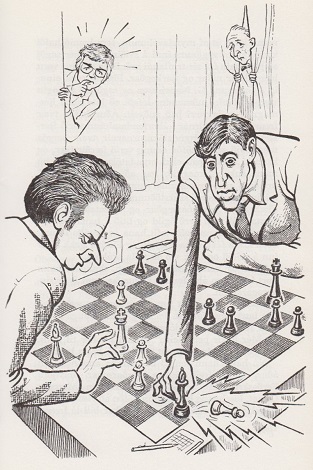

The Fischer game (played almost exactly 63 years after Corzo v Capablanca) did not need to be identified. The notoriety of 29...Bxh2 in the first Spassky v Fischer match-game is such that, as shown in C.N. 9762, it even inspired a cartoon:

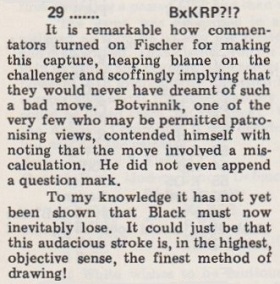

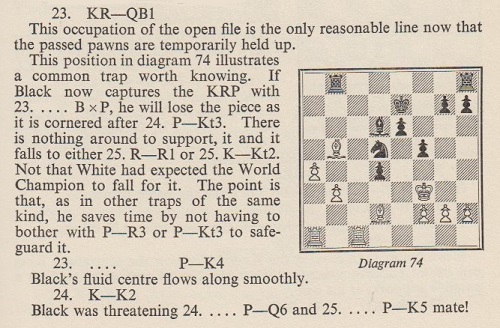

The possible play after 29...Bxh2 has been investigated in exceptional detail; see, for example, pages 75-94 of Analysing the Endgame by Jon Speelman (London, 1988). In the early comments after the match, P.H. Clarke’s on page 303 of the September 1972 BCM were among the most surprising:

Although page 431 of the second edition of The Games of Robert J. Fischer by Robert G. Wade and Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1972) stated that ‘29...BxRKP?!’ [sic] ‘is no gross blunder’, that was not the commonest view. For instance, the move received two question marks on page 114 of Reuben Fine’s book on the match, where he remarked:

‘Every beginner knows that this is a blunder, and it does lose ...’

Strange to say, it is a struggle to find pre-1972 books for beginners that warned of the specific type of poisoned-pawn trap which occurred in the Reykjavik game.

(9805)

Martin Sims (Upper Hutt, New Zealand) points out a passage on page 69 of Further Chess Ideas by John Love and John Hodgkins (London, 1965), concerning Bronstein v Botvinnik, Moscow, 1951 (eighth match-game for the world championship):

(9809)

From Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA):

‘Fischer can be seen playing 29...Bxh2 at the 1’00” mark of a video from the NBC news archives. The moments of play shown are not necessarily sequential; for example, the bishop already stands on h2 at 0’42”. Some of the subsequent play (33 Kg2 hxg3 34 fxg3) can be seen at 1’10” of another video.From the NBC item it appears that Spassky was away from the board when 29...Bxh2 was played, a circumstance which casts doubt on any descriptions of his supposedly surprised reaction to the move. For example, on page 172 of Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World (New York, 1974) Brad Darrach wrote:

“Spassky jolted like a man hit by a bullet and stared at the board.”

Page 92 of Fischer/Spassky: The New York Times Report on the Chess Match of the Century mentioned the “look of incredulity” on Spassky’s face, said to be noticed by an audience member with binoculars.

That New York Times book (by Richard Roberts, with Harold C. Schonberg, Al Horowitz and Samuel Reshevsky) is perhaps unique in its appraisal of the position after 29...Bxh2, as it claimed – without supporting analysis – that Fischer had winning chances after the loss of the bishop: Page 121 stated:

“But two pawns often defeat a bishop in an endgame, and Fischer’s seizing of the “poisoned” king rook pawn, after the exchanges that followed, left him with five pawns to Spassky’s three. This would have meant obtaining winning chances if he had continued the game properly and precisely.”

Pages 122-123 added:

“In one sense, the first game began with Black’s 29th move. And it is still difficult to say whether Fischer’s judgment was correct. He could have won. He certainly could have drawn. But he did neither. He lost. [*]

What followed that 29th move was inaccurate play on Black’s part that made the capture of the king rook pawn, in retrospect, look like a blunder. It was not. Fischer did, however, blunder away his chances in the play that followed, first missing a win and then a draw. His technique failed.”

I see nothing in the book to indicate which of the four co-authors was responsible for that opinion.’

We note that page 113 of the French translation of the New York Times book, published under the title Fischer Spassky. Le super-match du siècle (Montreal, 1972), added a translator’s note to the passage that we have marked above with [*]:

‘Seule une admiration aveugle pour Fischer peut justifier ce passage. N’importe quel amateur sait qu’il faut généralement non pas deux, mais trois pions pour tenir tête à un fou en fin de partie. Il est vrai que Fischer a commis, à son 40e coup, une erreur qui lui a coûté la nulle, mais l’auteur ne mentionne pas que ses chances d’annuler n’apparurent que grâce à une erreur de Spassky au 36e coup. En effet, si celui-ci avait mis son roi en marche tout de suite par 36 Rg4!, au lieu de perdre un tempo avec 36 a4?, Fischer n’aurait pas pu, malgré la meilleure technique du monde, sauver la partie, et encore moins la gagner!’

The imprint page stated that the book had been translated and adapted by Yves and Camille Coudari. The latter was also named on the title page as a contributor.

Reshevsky’s role in the New York Times volume is unknown, but his own book on the match (New York and Edinburgh, 1972) described ‘29...BxKRP??’ as ‘the worst blunder Fischer ever made’. See pages 5 and 9.

(9812)

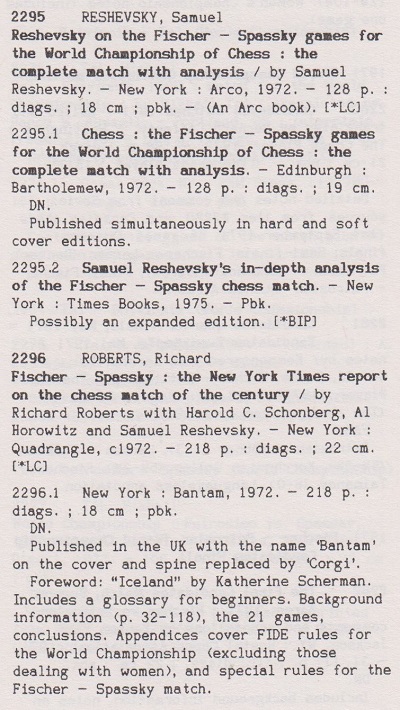

From page 196 of Chess An Annotated Bibliography 1969-1988 by Andy Lusis (London, 1991):

It is curious that Reshevsky had his name on the title page of three books on the Spassky v Fischer contest. The least familiar of them is Samuel Reshevsky’s In-Depth Analysis of the Fischer/Spassky Chess Match, and, contrary to the information (gleaned from Books in Print) in Lusis’ entry, it too was dated 1972. The title and imprint pages:

(The orange front cover had ‘Prepared exclusively for The New York Times and Bantam Books by Samuel Reshevsky’.)

The content is very similar – and often identical – to that of the well-known 128-page book published in New York and Edinburgh. Reshevsky’s Foreword is substantially different, and, for instance, page 3 of the Quadrangle Books, Inc. volume had the following:

‘Though the pre-match fireworks – cliff-hanging negotiations, protests, demands, postponements, disappearances – were more than anyone had expected, the title match itself fell disappointingly short of the titanic battle everyone looked forward to.

True, there were several excellent games but, in general, Fischer didn’t live up to the public’s expectations. His play lacked brilliance, though he defended excellently. And toward the end he surprised everyone by coasting along, accepting draws. He had never done that before; his reputation was that of a killer, a player who played to win, not to draw.

And Spassky? His performance seemed inexplicable. If Fischer made bad blunders, Spassky made incredible ones. In two games, for example, he overlooked one-move combinations; the first forced his immediate resignation, the second deprived him of all chances for a victory.’

The final paragraph nonetheless stated:

‘Still, despite the blunders, despite the general lack of brilliance, it was truly the chess match of the century, and the one that gave the United States its first formal world chess champion.’

How much of this was penned by Reshevsky is impossible to know, for the reasons set out in Chess and Ghostwriting.

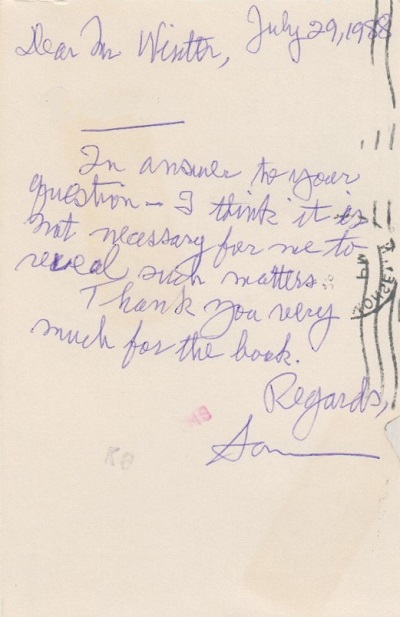

In a letter dated 23 July 1988 we asked Reshevsky about published suggestions that books of his had been ghostwritten, and he replied by postcard on 29 July 1988:

(9833)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) has sent us a PDF file of Botvinnik’s annotations to the first match-game, on pages 8-9 of the 28/1972 issue of 64, as well as an analytical article on the ending (by Anatoly Mikhailovich Kremenetsky on pages 39-41 of the 2/1973 issue of Shakhmatny Bulletin).

A comment by Fischer on 29...Bxh2, 20 years later, is noted by Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA). Page 15 of No Regrets by Yasser Seirawan and George Stefanovic (Seattle, 1992) reproduced a question from Ivan Solotaroff of Esquire in the transcript of the first press conference, on 1 September 1992:

‘Why did you take on h2 in the game against Spassky in 1972? Were you trying to create winning chances by complicating a drawn position?’

Fischer’s reply:

‘Basically, that's right. Yes.’

An addition from Sean Robinson on 23 July 2022:

‘The recently published English translation of Guðmundur Thórarinsson’s The Match of All Time (New in Chess, 2022, originally published in 2020 in Iceland), refers to the bishop move, citing Thórarinsson’s account of a conversation with Fischer in Iceland, circa 2000-05. (Thórarinsson does not cite dates, but contextual references on pages 136 and 184 offer clues.) The specific reference to 29...Bxh2 appears on page 136:

“Many known chess masters are of the opinion that this turn of events must be categorized as the most unexpected blunder in the history of chess. Later, in Tokyo, I discussed the incident with Fischer, and he told me that he had overlooked that the bishop would be hemmed in. Friðrik Ólafsson in his annotations demonstrated that Fischer could have achieved a draw.”’

Concerning the ‘BxRP manoeuvre’ in other games, see C.N.s 9805, 9809, 9812, 9861, 9871, 10264 and 11552. For example, C.N. 10264 discussed the position after 27...Bb5-c4 in the 30th match-game (also described as the fifth exhibition game) between Alekhine and Euwe, Rotterdam, 16 December 1937, in which Alekhine played 28 Bxh7.

Many annotators of the 12th game in the 1972 world championship match (Fischer v Spassky) referred, on or around move 16, to Ståhlberg v Capablanca, Margate, 1936, although only for that earlier game’s theoretical significance.

For further information about the 1936 game, see not only C.N. 8169 but also C.N.s 8184, 8189 and 8271.

C.N. 6081 gave a photograph of Clement Freud presenting a cheque to Robert Bellin, the winner of the London Chess Congress in Islington in December 1972.

Earlier that year, as mentioned on page 222 of Profile of a Prodigy by Frank Brady (New York, 1973), Clement Freud went to Reykjavik for the Spassky v Fischer world championship match. We note that an article by him, ‘A week of waiting for P-Q4’, was published in the Financial Times of 8 July 1972 and reproduced on pages 161-166 of the posthumous anthology A feast of Freud (London, 2009). Some snippets:

If you consider that in the course of seven days God created the universe, it is pretty shameful that in 80% of that time the World Chess Federation, though urged on by a fair section of the world, was unable to bring two men around one chess board. Yet such was the case.’

We had expected Fischer to come loping out of a corner on all fours, frothing at the mouth, bandages hiding the wounds from which surgeons had extracted his horns. He turned out to be a lean, gangling, engaging man wearing an uncontroversial green suit and matching tie.’

We have seen no references to chess in Clement Freud’s autobiography Freud Ego (London, 2001).

Clement Freud’s signature in our copy of Freud Ego.

Regarding the logo for the 1972 match, see too C.N. 10672.

From Božidar Kažíć (Belgrade):

‘During the closing ceremony in Reykjavik, 1972, the then President of FIDE, Dr M. Euwe, presented Fischer, the new world champion, with a gold medal. While still on stage, Fischer spoke to Dr Euwe as he showed him his medal. I have read in many books and magazines that Fischer remarked that the medal “was too small”. Once I asked Dr Euwe what Fischer really said at that moment. “He said that his name was not on the medal”, Dr Euwe replied to me. Nothing about the gold medal being little ...’

(1799)

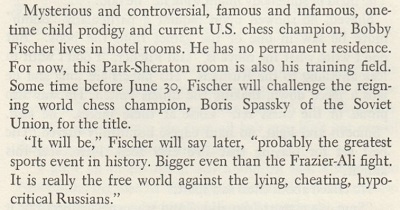

The final paragraph of the Introduction on page 16 of Fischer vs. Spassky by S. Gligorić (New York, 1972):

‘The challenger was, perhaps, right when he claimed: “It will probably be the greatest sports event in history. Bigger even than the Frazier-Ali fight ...”’

It has been affirmed (see, for instance, page 18 of the November 1999 Chess Life) that Fischer made that remark ‘on the eve’ of the Reykjavik match, but we have traced it back to a syndicated newspaper article by Ira Berkow published in January 1972. One of many outlets available on-line is the Lompoc Record, 17 January 1972, page 7.

The interview by Berkow (‘New York, January 1972’) was included on pages 79-82 of his anthology Beyond the Dream (New York, 1975), under the title ‘Bobby Fischer: Sportin’ Champ’. From page 79:

(8996)

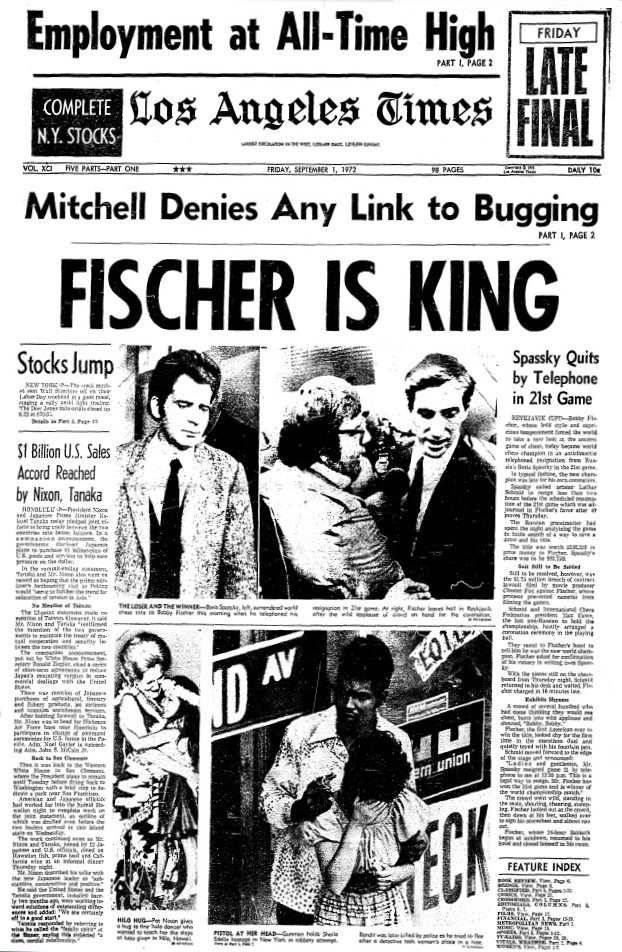

Page 1 of the Los Angeles Times, 1 September 1972:

(9004)

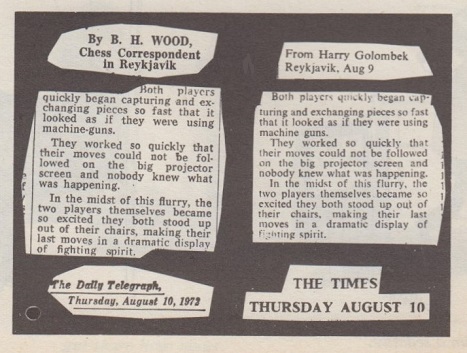

A curious item from page 204 of the 16-22 August 1972 issue of Punch:

Can any reader take the matter further?

(9106)

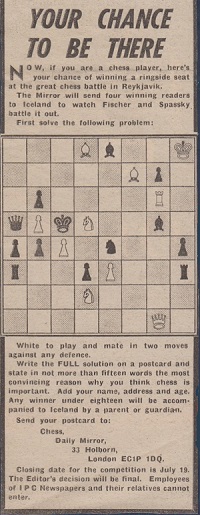

Below, from our archives, is a report in the Daily Mirror (London), 12 July 1972:

The same page had a two-mover by, we believe, Guy W. Chandler:

No record has been found of the Daily Mirror setting a problem-solving competition in 2014 for its readers to win a ringside seat in Sochi.

(9141)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The two-mover from the Daily Mirror was indeed by Guy Chandler. Comins Mansfield quoted it in his Selected Two-Movers column in the September 1972 issue of The Problemist (page 252), although he gave the date of publication as 13 July, and not 12 July as indicated in C.N. 9141.

Mansfield wrote:

“It must be a rare, if not unique, experience for a composer to have one of his problems fetched by a special car from a distance of 12 miles. This happened to our esteemed secretary in July, when he had an urgent telephone call from a national newspaper. It proposed to offer a free holiday in Reykjavik to four readers who would solve a chess problem and answer in not more than 15 words a question such as ‘What makes chess worthwhile?’. The newspaper wanted immediately a ‘tough and entirely original problem’, but all that could be offered on the spot was an original two-mover. They gladly accepted this and sent a car down to Sutton to fetch it. This resulted in the publication of A on 13 July. With its nine variations and clear-cut theme it was just the sort of problem to stimulate popular interest.”’

The date discrepancy referred to by Mr McDowell is explained by the fact that the problem appeared in the Daily Mirror on both 12 and 13 July, the latter time on a page entirely devoted to chess. The problem was on page 9 on both days.

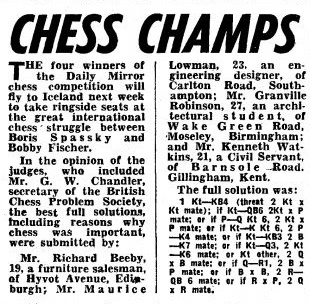

We have found the solution to the competition and the winners’ names on page 2 of the 4 August 1972 edition of the Daily Mirror:

(9145)

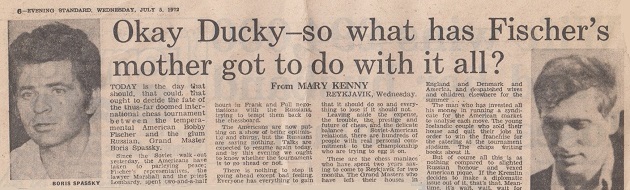

A rummage through boxes of newspaper cuttings on the 1972 world championship match suggests that the sharpest criticism of Fischer was written by Mary Kenny in the London Evening Standard. With no chess knowledge (she mixed up the words game, match and tournament and described Harry Golombek as a grandmaster) she concentrated on human aspects in her reports and wrote good prose. Below is an excerpt from her article ‘Genius maybe – but is he human?’ on page 17 of the 28 July 1972 edition. At that time she had been watching Fischer in Reykjavik for ten days:

‘Fischer, as is widely known, is not merely a megalomaniac but also a monomaniac; all the kilowattage of that 187-IQ brain has been channelled into the game, leaving aside almost everything else in the spectrum of life’s experiences.

He is a chess phenomenon, it is true; but he is also a social illiterate, a political simpleton, a cultural ignoramus and an emotional baby. There are no vibrations of humanity from him; when you look at him, his eyes are blank and unstaring, since he only has eyes for chess. He is a machine.

The article ended on a low note:

‘He will go on to be the undisputed chess king of the world, and destroy all challengers for some time to come. And then what?

Unlike old boxers, for old chess champions there is nothing else. Gligoric, the Yugoslav Grand Master who is writing a book about this very tournament, says that the end for chess geniuses is a towering solitude. They die in their 40s and early 50s. They fall into depression or paranoia, like Nimzowitch and Rubinstein; die alone of drink in foreign hotels like the great Alekhine, or sink into bewildering madness in a hospital straitjacket, like Fischer’s only comparably outstanding compatriot, Paul Morphy.

The way that the game possesses, spends and finally exhausts the minds that become engaged and committed to it is, in one sense, a tribute to its extraordinary magic, its brain-burning bewitchment.’

A curiosity is that the exact phrase about Fischer ‘also a social illiterate, a political simpleton, a cultural ignoramus and an emotional baby’ is in a recent work of fiction, The Sinking of the Basil Hall by James Street. [The link no longer works.]

(9146)

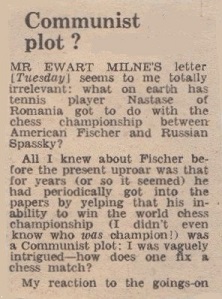

C.N. 9146 referred to Mary Kenny’s breezy despatches from Reykjavik in the London Evening Standard during the 1972 Spassky v Fischer world championship match. In addition to her yellow, or yellowish, journalism, the newspaper welcomed comment of the same hue on its correspondence pages. It is doubtful whether any previous chess event offered so many people an opportunity to ‘have their say’ despite being even less well informed than most of the journalists.

On 1 August 1972 A. Hawson (London) felt the need to respond in the Evening Standard (‘Via-Dictate-A-Letter’) to what a correspondent had said on 27 July and, in particular, ‘to take issue with the suggestion that the £50,000 donated by Mr Slater ... should have been given to the British Olympics Appeal. The publicity now being given in the British Press to the great game of chess is long overdue and I, for only one, am very glad ...’, etc., etc. On the same page, Ewart Milne (Bedford) recalled Mary Kelly’s description of Fischer as ‘a social illiterate, a political simpleton, a cultural ignoramus and an emotional baby’ and proffered this rejoinder: ‘So was Napoleon Bonaparte, but he changed what is called the art of war forever.’ Mr Milne’s contribution ended: ‘Personally I cannot see anything abnormal or even objectionable about Bobby’s tantrums. How about Nastase? Or is it only Americans who are hated when they show off?’ That red rag elicited a letter in the 4 August 1972 edition from Teresa Malik (London). Her analysis of the Match of the Century seamlessly incorporated a description of her credentials for the task:

From Iceland, meanwhile, Mary Kenny continued to chew over almost every aspect of the chess match except the chess, and the eventual cessation of her reports was itself a topic for comment. The following was published on 16 August 1972:

Letter-writers know that submissions in colourful language (‘despatch her to Terra [sic] del Fuego’) are more likely to reach the presses. To that end, ‘lock them up and throw away the key’ and ‘hanging is too good for them’ have always been serviceable entreaties. Then as now, a measured analysis of pros and cons is less likely to attract an editor’s eye than a spree of fustian ignorance. Now but not then, the Internet allows anyone to by-pass whatever barriers, however low, editors put in place for participation in a discussion. There are pros and cons there too.

Chess magazines in 1972 were relatively restrained in their strictures on Fischer’s conduct and, with so much chess play to cover, little space was available for disquisitions by the unknown. As the Reykjavik frenzy receded, however, so-called debates came back into fashion. Criticizing ‘free speech in action’ may not be regarded as good form, but Wolfgang Heidenfeld had no such inhibitions on page 257 of CHESS, June 1973, in a letter headed ‘Rabbits and Nonsense’:

‘Your correspondence about simultaneous display etiquette is becoming boring, especially as most of the views represented are those of rabbits who do not even know the rules.’

Heidenfeld died long before the Internet age. What he would have written about vox populi today is neither difficult nor unpleasant to imagine.

(9531)

Another typical letter (‘Bobbie Fischer is awful, but ...’), from the Evening Standard, 3 August 1972:

On the subject of hypnotism (Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) adds the case of Romark, who was discussed by Harry Golombek on pages 95-96 of Fischer v Spassky (London, 1973). Golombek quoted the following ‘from what I wrote at the time’:

‘Romark, Newcastle’s own Ron Markham, has challenged Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky to play a consultation game against him at the end of the match and this for a stake of £125,000. Fischer and Spassky are asked to put up £62,500 each as their stake. So confident is Romark of winning that he is putting up £25,000 himself, the remainder being provided by his backers and associates. More, he is prepared to play blindfold against them.

... The reader, if as ill-informed as I was, might now ask who is Romark, what is he? Here are some facts provided by his publicity agents. At present he is based in Durban. At an anti-smoking rally in Newcastle last year he cured 2,000 people of smoking. This year, in Durban, before an audience of doctors, he hung [sic] himself for four minutes, was officially pronounced dead, and then, presumably, recovered. Romark says he is an average chessplayer. He would appear to be a more than average hypnotic medium.’

Golombek’s original article, ‘High drama in Reykjavik’, was written in Iceland during the world championship match and appeared on page 11 of The Times, 19 August 1972. Before coming on to Romark, Golombek indulged in much booksy waffle, contriving to mention Corneille, Agatha Christie and The Mousetrap, Brian Rix’s farces, Racine, Mozart, The Caretaker and Lord of the Flies. He also gave Spassky’s win in the 11th match-game, with brief notes.

A small advertisement on page 23 of The Times, 27 June 1975:

(9129)

The Icelandic database Tímarit.is has much interesting material, a good starting-point being searches with the words ‘skák’, ‘Spassky’ and ‘Fischer’.

(9573)

To write about the 2016 ‘Karjakin-Carlsen’ match would be odd and, even, discourteous to the defending champion, yet most of us have, at least occasionally, referred to the ‘Fischer-Spassky’ match of 1972. Alphabetical order and the identity of the winner cannot explain this, because the 1927 world title match is usually, and properly, termed ‘Capablanca-Alekhine’. Fischer’s profile in 1972 was so high, often for woeful reasons, that it is tempting to name him first even though he was the challenger, but a linguistic point also arises. From pages 39-40 of The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsyth (London, 2013), in the chapter on hyperbaton:

‘Have you ever heard that patter-pitter of tiny feet? Or the dong-ding of a bell? Or hop-hip music? That’s because, when you repeat a word with a different vowel, the order is always I A O. Bish bash bosh. So politicians may flip-flop, but they can never flop-flip. It’s tit-for-tat, never tat-for-tit. This is called ablaut reduplication, and if you do things any other way, they sound very, very odd indeed.’

Thus in British politics in the late 1970s, the term ‘Lib-Lab pact’ was used despite the Liberal Party being far smaller than the governing Labour Party. Even when the consonants in the two elements are different, it may seem more natural for I to precede A. ‘Fischer-Spassky’ is certainly more euphonious than ‘Spassky-Fischer’, but ‘Fischer-Spassky’ may best be reserved for their 1992 match.

(9912)

Juan Carlos Sanz Menéndez (Alcorcón, Spain) submits the following:

‘La Batalla Fischer-Spassky/El maravilloso Mundo del Ajedrez’ in Estrellas del Deporte (Mexico, 1973), page 31.

(5418)

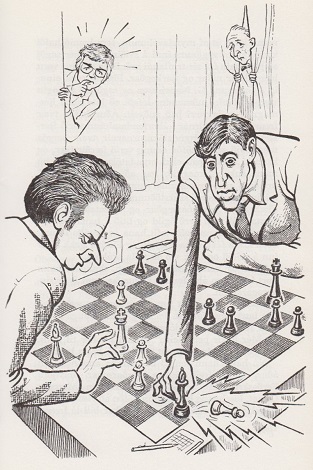

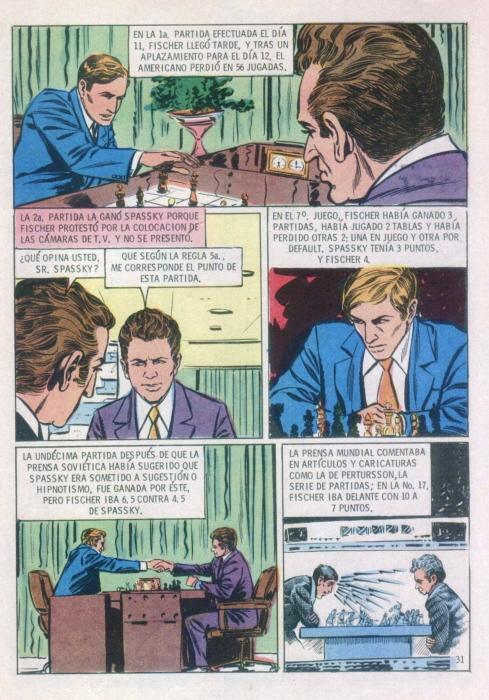

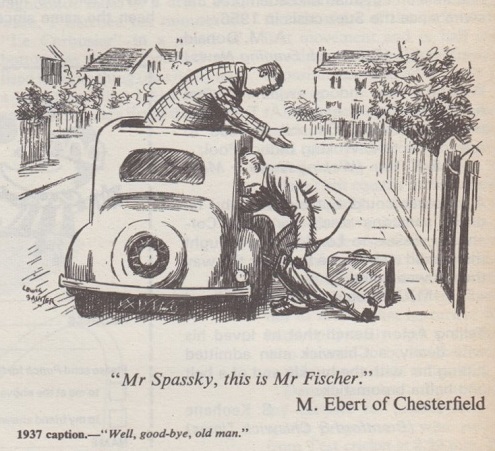

The immense popularity of chess in 1972 is demonstrated by a double-page spread of cartoons (‘There’s No Business Like Chess Business’) by Mahood on pages 118-119 of the 26 July-1 August 1972 issue of Punch:

One example:

(9105)

Punch, 16-22 August 1972, page 220

(9124)

Evening Standard, 5 July 1972

(9147)

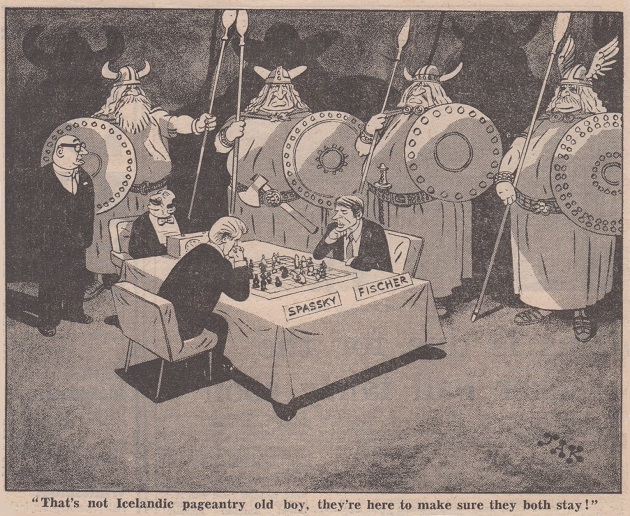

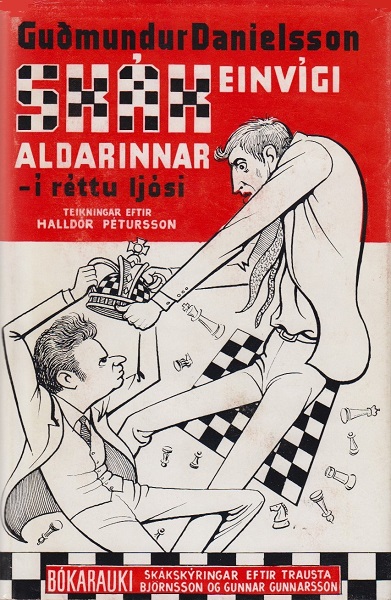

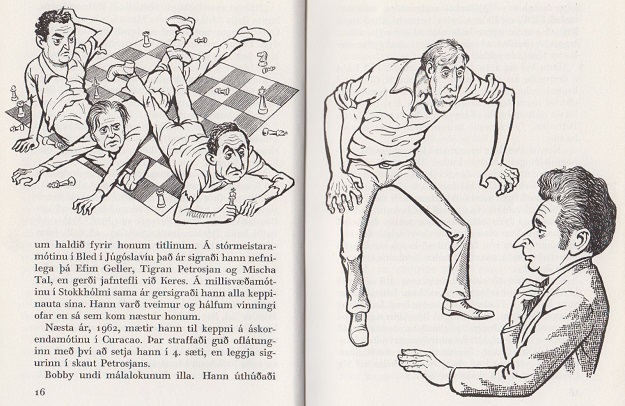

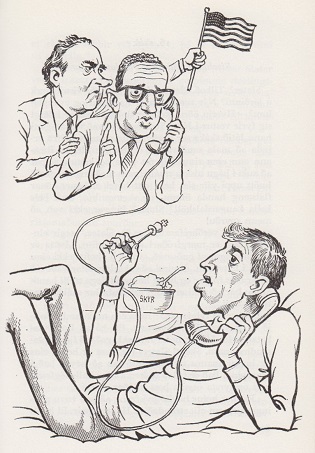

Of all the books on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match, the one in our collection with the most cartoons is Skákeinvígi aldarinnar by Guðmundur Daníelsson (Reykjavik, 1972). A small sample (from pages 16-17, 103 and 163):

Although mainly a prose account of the Reykjavik match, the book concludes with annotations to the games (pages 291-345).

(9762)

An Icelandic webpage presents a set of 19 cartoons on the 1972 world championship match.

(9948)

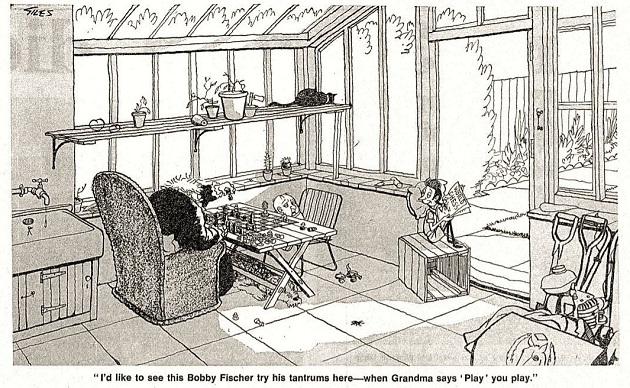

A cartoon by Giles on page 6 of the Daily Express, 6 July 1972:

(10827)

Readers are invited to identify the person with whom Fischer is, to borrow a mouldy expression favoured by captionists, ‘sharing a joke’.

(5065)

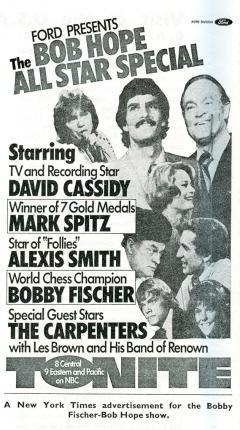

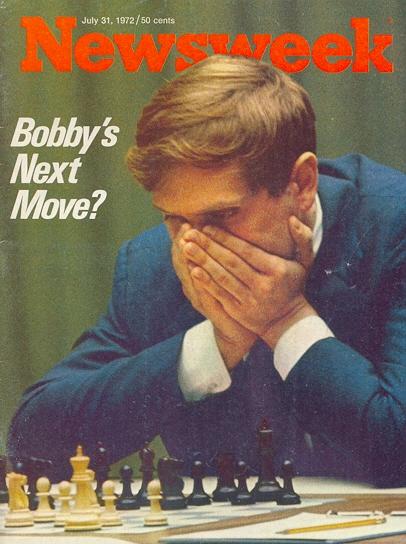

Bobby Fischer is at the board with Bob Hope (1903-2003) in a photograph on page 291 of a book on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match, Campeonato del mundo (San Sebastián, 1972). An advertisement for the television programme appeared, inter alia, on pages 78-79 of CHESS, December 1972:

A recording of Fischer’s performance is commercially available.

(5072)

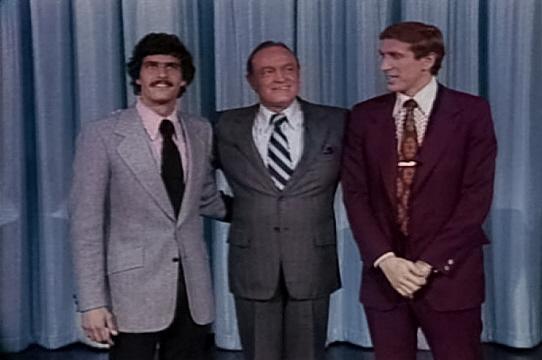

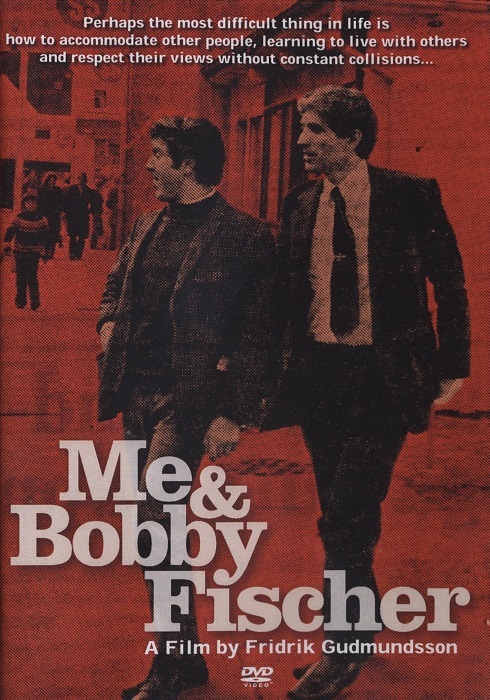

From Fischer’s guest appearance in autumn 1972 on The Bob Hope Special television show, which also starred Mark Spitz, we have made three stills:

In the early part of the programme Bob Hope (‘Hopeski’) was shown enduring a lonely wait at the board. The world champion’s eventual arrival led into some rather wooden banter (naturally covering such topics as unpunctuality, cameras, noise and money), whereafter the comedian played 1 c4 and won a top-speed game during which he muddled chess and checkers and elicited the loudest possible racket from a bag of nuts.

Although the cue-cards were successfully kept off-camera, the production and editing were choppy, with, even, Hopeski’s king and queen switching places between two shots at the start of the game. The sketch lasted six minutes. Fischer received a very warm reception, although not the standing ovation accorded to Mark Spitz.

(5094)

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) points out a letter written by Reuben Fine which was reproduced on page 260 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2007). Dated 27 November 1972 and addressed to Norval Wigginton of Bethesda, MD, Fine’s letter reads (last paragraph):

‘I’ve challenged Bobby to a match for the title for a purse of $1 million, which I think could be raised if he would agree to play. But he hasn’t replied to my letter. Maybe you could get a committee together to see whether it could be done.’

Is anything more known about the challenge? The following appeared as a footnote on page 54 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship by ‘Reuben Fine, Ph.D., International Chess Champion’ (New York, 1973):

‘A Las Vegas hotel reportedly offered $1.4 million for a return match with Spassky which Fischer refused, demanding $10 million. I have also challenged Fischer to a match for a purse of $1 million. Some are now openly wondering whether Fischer will ever play again.’

In a review of Fine’s book on page 396 of the June 1974 Chess Life & Review Anthony Saidy referred to ‘Fine’s rather pathetic “$1 million” challenge to Bobby’. On page 467 of the July 1974 issue ‘A Reply from Reuben Fine’ did not comment on that point.

(6165)

Regarding Reuben Fine’s post-Reykjavik challenge to Bobby Fischer for a world title match with a purse of one million dollars, a sourceless paragraph was published on page 125 of the February 1973 CHESS:

‘“I’d play Fischer for the world championship if the stakes were high enough”, said Reuben Fine to Robert Byrne recently. “How high?”, asked Byrne. “Say a million dollars”, replied Fine and was quite upset when Byrne thought he was joking.’

(8273)

Pages 4-7 of the January 1973 Chess Life & Review transcribed interviews (originally published in the Icelandic magazine Skák) by Gligorić with Fischer, Spassky and Thórarinsson for a radio audience. A compilation of some remarks by Fischer is given below:

(4274)

General reference works customarily avoid hyperbolic editorialization, but the nine-line entry on Spassky on page 1376 of the Chambers Biographical Dictionary edited by Magnus Magnusson (Edinburgh, 1990) has this statement in connection with the 1972 world championship match:

‘His defeat before the full glare of international attention gave him the unfortunate legacy of the most famous loser in sporting history.’

(8622)

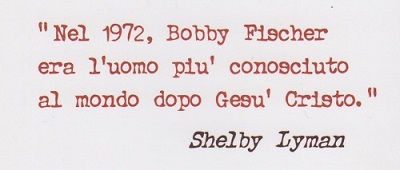

From the back cover of Tutte le partite di Bobby Fischer by Karsten Müller (Rome, 2011):

Whether Shelby Lyman ever made that specific assertion is unclear, but after about an hour of Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World (C.N. 7345) he did say to camera:

‘One of Fischer’s problems was that, after the match, he was supposedly better known by the population of the world than anyone except for Jesus Christ. And he was a guy who treasured his privacy. He had a problem.’

(9953)

Regarding Bobby Fischer Against the World, Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA) noted in C.N. 7361 a remark by Anthony Saidy on the third game in the 1972 world championship match, which began 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 c5:

‘In game three Bobby played an opening, a defense, he had never played before, the Benoni ...’

C.N. 10497 presented extracts from the article ‘Reflections after Reykjavik’ by Gerald Abrahams on pages 84-90 of Encounter, March 1973. A selection is below:

‘Journalism is the study of the irrelevant. Through that too bright glass, which when focused disturbs the concentrator on essentials as sorely as the television lights disturbed Bobby Fischer, everything trivial is aggrandized, everything insignificant given a value. Over there, at “the battle of Reykjavik”, there was no dearth of trivia. As Browning might have asked, “Who fished up that maroon suit? What breakfast had the Russ?” In that novel context a plethora of irrelevancies scattered itself around for grubmen to devour and regurgitate; just like mistakes on the chess board, waiting there to be made.’

‘... in the lively oracles of the world press, we were shown Might campaigning against Right, or Right against Left – strange analogies for a couple of hard-working Jewish boys “doing the best they could”. Incidentally, they and their companions, coming from Brooklyn and Moscow to Iceland, constituted the first large-scale Jewish immigration in the history of the island.’

‘Fischer’s play was described as “relentless” and “ruthless”. This is a splendid example of what Ruskin called “The Pathetic Fallacy”, as when the would-be poet speaks of the “cruel Sea” or the “kindly Vales”. Chess moves are effective or ineffective. A chess move is not cruel when it is good; nor is a bad move intended as an act of kindness.’

‘Chess, which is a science of the relevant – everything that journalism is not – was purveyed as news to the avid spectators of meaningless spectacle. These were determined to see a bullfight; and they clothed with appropriate trappings one who was never a bull and another who was never a matador. In fairness, it should be added that Fischer cooperated, away from the board, by baiting FIDE, baiting Iceland, baiting the Soviet Union, attacking the TV promoters, and conducting a first-class war against himself. But the metaphor of the bullring loses everything when one realizes that never at any stage was Fischer hostile to Spassky; whom, in fact, he has always admired.’

‘The match was probably “the most human” chess contest that has ever been staged. Fischer, starting in the grip of a nervous breakdown, handicapped himself as no world contestant has ever done.’

‘[Fischer] came to the board (rather late) in the third round and produced a masterpiece. He seemed detached, somnambulistically, from all that had gone before.

The famous Kt-R4 in that game may have seemed to Spassky to be a gamble; but there was profound and original thought involved in it. One is reminded of that fact that the immortal attack with which Fischer, playing Black, defeated Donald Byrne nearly 20 years ago, commenced with a sacrificial Kt-R5. If Fischer has a style, under his versatility, it seems to be characterized by clever knight play, and there was plenty in this match. In this respect he resembles Alekhine rather than Capablanca ...

In this game Fischer gave the friendly critic many reasons for admiration. First, he showed that chess strategy can be dynamic: not only knowing what to do when there is nothing to do; but a line of thought in which the tactics and the shaping of the game are integrated in purposeful play, involving a clear vision of long and subtle variations. This is great chess.’

‘Fischer is said to think badly of Lasker. But I permit myself to suggest that he showed Laskerian qualities in two ways: first, in his readiness to accept any offer of material; second (and this is necessitated by the first) in his extraordinary powers of defence against heavy attack, and his ability to emerge with advantage. Perhaps he drove on beyond visibility, but his judgment was always superb.

There are, roughly, two ways of trying to win at chess. The tradition of Morphy, Steinitz, Capablanca and Rubinstein is to develop well and subtly, seizing very slight initiatives, converting them to advantages and the advantages into victory. Like “unheard melodies”, the Sturm und Drang are in the mind only. The other method, the method of Lasker and Alekhine, is to unbalance the game, bringing about skirmishes and hard fighting. There the great combinations are more frequently visible.’

Have recordings survived of the ‘first post-match interviews’ with Fischer and Spassky conducted by Gligorić for Radio Belgrade?

A report by Dragoslav Andrić on pages 2-3 of CHESS, October 1972 had transcripts, including these exchanges:

Gligorić: ‘Will you be making propositions concerning possible changes in the procedure of the world championship?’

Fischer: ‘I would not like to say anything definite just yet. For the time being, I want to play a few matches. Money is there and I want to make it.’

Gligorić: ‘Perhaps you would like to play Spassky again.’

Fischer: ‘Sure. If the purse is big enough, we will certainly play a return match.’

(10976)

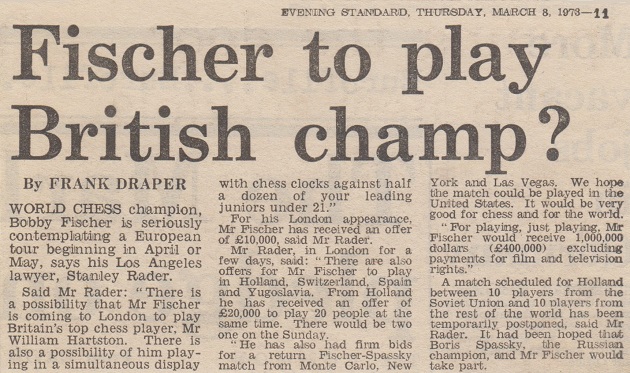

An article by Frank Draper on page 11 of the Evening Standard, 8 March 1973:

See too C.N. 11045.

Anyone feeling rather anti-Soviet just now and fearing for his objectivity should procure the April [1985] issue of the trilingual Schweizerische Schachzeitung and read a four-page article ‘Les énigmes de Moscou’ by Fernando Arrabal. The title turns out to be something of a misnomer since the writer has all the answers. His solution to the Moscow mess is that the most anti-Soviet masters should form a committee to arrange a championship between ‘today’s two strongest living players: Fischer and Kasparov’. Our initial impression on reading Arrabal’s grotesquely distorted account of how Fischer made it to the summit despite Soviet treachery is that here at last the West has found its answer to Kotov and Roshal. What do the Fischer experts think of Arrabal’s propaganda?

(979)

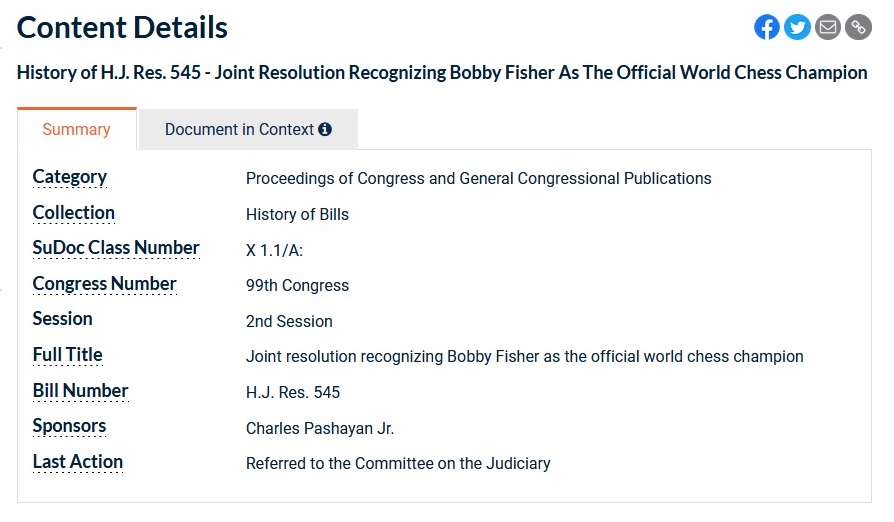

In the United States in March 1986 the House of Representatives passed a Resolution, sponsored by Charles Pashayan, which recognized Bobby Fischer as the world chess champion. Siegfried Hornecker (Heidenheim, Germany) provides a link to the record of the Resolution.

(7338)

The above link no longer works, and we offer this replacement regarding the ‘Fisher’ Resolution:

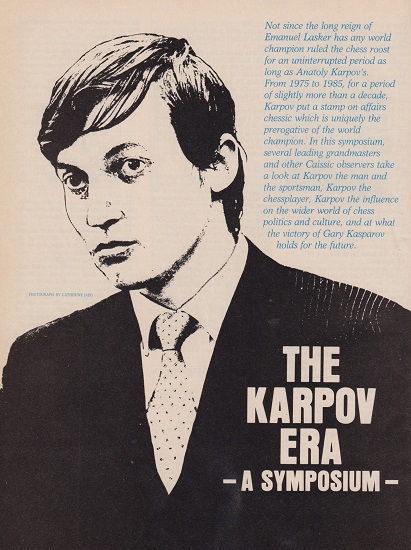

‘This must surely be simply the stupidest remark made about any aspect of chess in 1985.’

That observation by a correspondent, W.D. Rubinstein, was published in C.N. 1121 (March-April 1986). It concerned a review of the Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1984) on page 33 of the December 1985 Chess Life. The reviewer, Larry Parr, devoted well over half his space to complaining that the Companion was pro-Soviet, and in C.N. 1079 we quoted a small sample, such as this:

‘But the grand prix for breathtaking mendacity must be this entry on Garry Kasparov ...’

In C.N. 1143 Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA) commented:

‘I would like especially to commend and strongly support Professor Rubinstein (C.N. 1121) for saying what needed to be said concerning the increasingly ludicrous remarks of L. Parr (in general, and specifically in his review of The Oxford Companion to Chess). Clearly some statement must be made regarding the deterioration in the quality (and the almost blatant jingoism) of Chess Life since Parr assumed the editorial position. Another disturbing development within the Chess Life/United States Chess Federation hierarchy appears to be linked in a way to this xenophobia and red-baiting: the sudden concern to declare Bobby Fischer world champion, a kind of obsessive cry to “bring back Bobby” while vilifying Karpov and the entire Soviet chess establishment for the behind-the-scenes chess politics that drove Fischer from chess, presumably. Certainly the Soviets have had more than their share of unsavory wheeling and dealing since the advent of the existing world championship qualifying system. But this insidious use of the specter of Fischer seems motivated solely by the political leanings of certain individuals at the apex of US chess, to be wielded like a club for whatever purposes deemed necessary.’

Also in C.N. 1143 we quoted from a Symposium on ‘The Karpov Era’ on pages 26-34 of the March 1986 Chess Life. For example, although Arnold Denker observed regarding Karpov, ‘even his severest critics never questioned his right to reign’, four pages later Charles Pashayan wrote:

‘... is it really any wonder that the World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer remains aloof from public chess?’

And here is Lev Alburt:

‘Isn’t it time that we Americans recognize the truth: Bobby Fischer is the reigning world champion.’

He called Kasparov ‘the new FIDE world champion’.

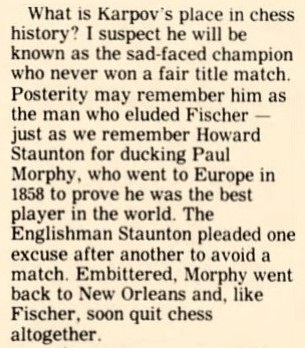

The contribution by Larry Evans to the Symposium had this remark about Karpov:

‘He will go down in history as the man who avoided a match with Bobby Fischer and then eluded him for the next ten years.’

The issue of Chess Life (December 1985) which contained the Companion review also published, on page 9, a letter from Lev Alburt with the following:

‘Mr Larry Goldberg and myself were active co-sponsors and defenders of Leland Fuerstman’s motion for the USCF to declare Bobby Fischer the world champion.’

Alburt then mentioned ...

‘... an idea for promoting chess: why not start off each issue of Chess Life with a small picture of Bobby Fischer in the upper right hand corner of the cover?

Your magazine is an excellent journal, but only a few hundred thousand of the thirty million Americans who play chess even know about it or, for that matter, about the USCF. A far larger number know the picture of Bobby Fischer. What better way could there be to attract attention, to increase newsstand sales, and to bring into the USCF thousands of new members?’

Reuben Fine

(frontispiece of his 1987 book The Forgotten Man:

Understanding the Male Psyche)

Another letter in Chess Life in 1985 (on page 6 of the May issue) was from Reuben Fine. Whilst criticizing the historical circumstances, he at least acknowledged that Karpov had become world champion in 1975 and had retained the title since then. Fine opined that ‘for the USSR chess is only a footnote to politics’ and he proposed that ‘the US Chess Federation should undertake bold and constructive action’:

‘I recommend that the United States take the initiative of splitting up FIDE into two separate organizations: one for the free world and one for the communist world. The best player from each world would then meet on as neutral soil as possible to play for the world championship.

If it is feasible, Robert Fischer should be brought back and declared the champion of the free world. If the Soviet champion should then refuse to meet Fischer in a match going to the man who first wins ten games, the Western countries should declare Fischer the world champion and let the two federations go their respective ways.’

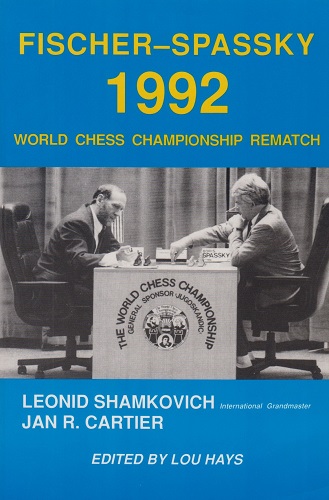

Despite such contributions to Chess Life, there has been almost universal acceptance that Kasparov became the chess champion of the world in November 1985 when he defeated Karpov in their second match. Seven years later, however, further attempts were made to shunt Kasparov aside, when Fischer played his second match against Spassky. In Instant Fischer, which examined six volumes on that 1992 match, we commented:

‘The books, all written before the Kasparov-Short world championship controversy arose, show a surprising willingness to entertain Fischer’s claims to the world championship.’

It is, though, necessary to bear in mind, and seek further information on, Kasparov’s ‘co-champion’ remark to Fischer, quoted in our above-mentioned feature article from page 282 of No Regrets by Yasser Seirawan and George Stefanovic (Seattle, 1992).

Anybody wishing to argue that Fischer was still the world champion in 1992 should, logically, also assert that he remained so until his death in 2008. That would make him the longest-reigning chess champion in history and would mean that Kramnik, for instance, never held the title at all. In reality, any chronicle which gives Fischer’s dates of tenure as other than ‘1972-75’ is, at best, eccentric.

Everything, of course, goes back to FIDE’s decision to remove the title from Fischer in 1975. Who has written the most detailed, accurate and equitable account?

(9880)

Concerning the above-mentioned review of the Companion, on 5 May 1986 Ken Whyld wrote to us:

‘Parr. I have no wish to enter debate with him. We assessed that his review of the Companion did us more good than harm. One of his points was that we did not say that Gulko was being detained against his will. At the time we sent in the MS it was reported in the chess press that he had an exit visa, so we were likely to appear out-of-date had we said he was detained. Parr’s review was published 15 months after the book’s publication, and two years after we finished the text. I do believe we could sue him for libel when he accuses us of “breathtaking mendacity” for our entry on a man whose forename Parr cannot even spell. Curiously our “mendacity” appears to be that we told exactly the same story that Parr tells, but far less crudely.’

The previous month (letter dated 4 April 1986) Mr Whyld had commented to us regarding Larry Parr:

‘His reputation as a bigot precedes him.’

From Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA):

‘On page 77 of his book on the life and games of V. Pupols, Larry Parr is described as having tied for first “in an international Swiss (1970) in Frankfurt, West Germany”. I was stationed in West Germany with the US Army from 1969 to 1971 and participated in a number of USCF-organized events where Larry Parr also played. The event which is described as an “international Swiss” was in reality at Rhein-Mein Air Force Base, where he and I and another player finished in a three-way tie for first. Although there were over 50 participants, I can’t believe it deserved any international connotations; certainly it lacked any participants of master strength or any host nation participants of significance. In short, it was a typical USCF weekend event that happened to be held and organized by military personnel outside the United States. A minor matter, but perhaps significant in the light of Larry Parr’s recent challenges regarding the academic and ideological credentials of others.’

In corroboration of the above Mr Tassinari kindly sends us a photocopy of pages 1-3 of the European Chess District Newsletter of the United States Chess Federation, dated 1 December 1970.

Frank Skoff (Chicago, IL, USA) passes us a copy of the November-April 1986 Minnesota Chess Journal, in which Kevin Toon says all the right things about Chess Life, its editor and its ‘Symposium’. Then there is an even more strongly worded article, by John Tomas, in the August 1986 APCT News Bulletin, to say nothing of a call for Mr Parr’s dismissal in the latest issue of the Myers Openings Bulletin.

(1238)

On 17 February 2002 Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) wrote to us:

‘As far as Evans and Parr are concerned, I think what it basically comes down to is that both have some sort of delusions that they know something of chess history, whereas in truth they both know very little. Thus the only real defense they have is scurrilous attacks on those who point out their absurd errors. Schiller belongs to the same slovenly group.

Nothing would surprise me about the USCF. Although I have known some good people in lesser positions there over the years, the people who have the power there are generally little better than guttersniping thieves out to enrich themselves at the expense of the USCF. Note their constant turnover. The publication has been a sorry rag for years and every time they start to improve it, some of their idiotic people ruin it again.’

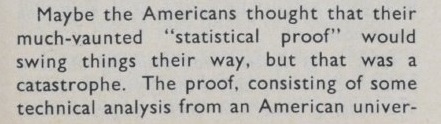

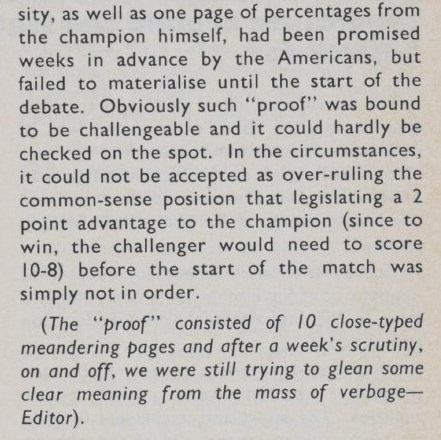

Myron Samsin (Winnipeg, Canada) notes that on page 229 of the May-June 1975 CHESS Craig Pritchett gave an eye-witness report on the FIDE General Assembly held in Bergen on 18-20 March 1975, where Fischer’s match proposals were voted on for the final time. An extract, together with a comment by the Editor, B.H. Wood:

Our correspondent asks for more information about the calculations submitted by the Americans.

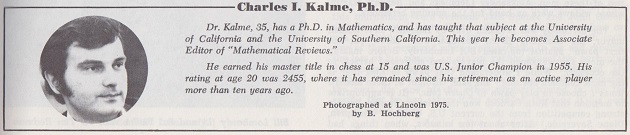

A huge amount of material on the topic (i.e. on the fairness or otherwise of Fischer’s proposed conditions) appeared in Chess Life & Review at the time. C.N. 2630 (see page 124 of A Chess Omnibus) mentioned the contribution of Charles Kalme, and we had particularly in mind his vast article ‘Bobby Fischer: An Era Denied’ on pages 717-729 of Chess Life & Review, November 1975. On page 715 of that issue, the Editor, Burt Hochberg, described the publication of Kalme’s article as ‘a momentous occasion in American chess’.

Chess Life & Review, November 1975, page 729

It will be appreciated if a reader can summarize, with brisk objectivity, the mathematical and statistical considerations underlying Fischer’s demands (i.e. his retention of the title in case of a 9-9 draw, and a score of 10-8 being required by his challenger to gain the world title).

As regards material submitted to the March 1975 extraordinary session of the General Assembly, details are sought. We have a large bound volume entitled ‘FIDE Papers 1972-75’, but the last document is dated 3 January 1975 (a letter to the Federations from the President, Max Euwe).

C.N. 8998 quoted the final paragraph of the match book Fischer/Spassky by Richard Roberts with Harold C. Schonberg, Al Horowitz and Samuel Reshevsky (New York, 1972):

‘One thing is certain: Three years from now there will be a new match for the chess championship of the world.’

For information about Richard Roberts, see C.N.s 9856 and 9869.

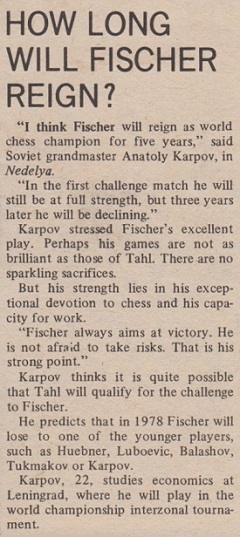

From page 15 of Soviet Weekly, 2 June 1973:

Adam Ponting (Petersham, Australia) notes a ChessBase article dated 5 April 2005 in which one of the questions posed to Kasparov by Mig Greengard and Dylan Loeb McClain, ‘Where would you rank yourself all-time?’, was answered as follows:

‘I don’t like this question in general, it’s too subjective. By most standards, number one because of the length of my high performance and the strength of the opposition. The greatest gap between the number one and the rest was Bobby Fischer in 1972, but that was just one or two years and then came Karpov. I was able to keep up with the new generation and beat them. I was able to stay on the cutting edge, stay on top of the ranking for 20 years. I would say that entitles me to be number one.’

(9852)

On pages 6-7 of Como ser campeón en el ajedrez by Evgueni Leonov (Mexico City, 1985) the list of world champions includes Murphy, Ewe, Aleknine and Boltvinik. The last two names are Eddie Fischer and Boris Karpov.

(10023)

Journalists who pay a flying visit to the chess world often muddle the terms ‘game’ and ‘match’, but confusion may even slip into chess books. It may be wondered who wrote the final paragraph of the unsigned Introduction to Chess: Games to Remember by I.A. Horowitz (London, 1973):

‘This book does not include the matches in the World Championship in Iceland in the late summer, 1972.’

(10601)

From page 16 of The Batsford Chess Yearbook by Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1975):

‘Quote of the Year

“If you don’t believe in victory you have no business sitting down to a chess board.” Anatoly Karpov.’

No source was provided, but we give the following from page 3 of the January 1975 BCM:

Corroboration of the remarks in a Soviet source will be appreciated.

(10625)

Dan Scoones provides part of an interview with Karpov on page 10 of the 48/1974 issue (29 November-5 December) of 64: