Edward Winter

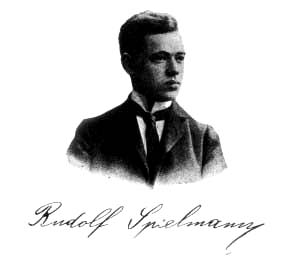

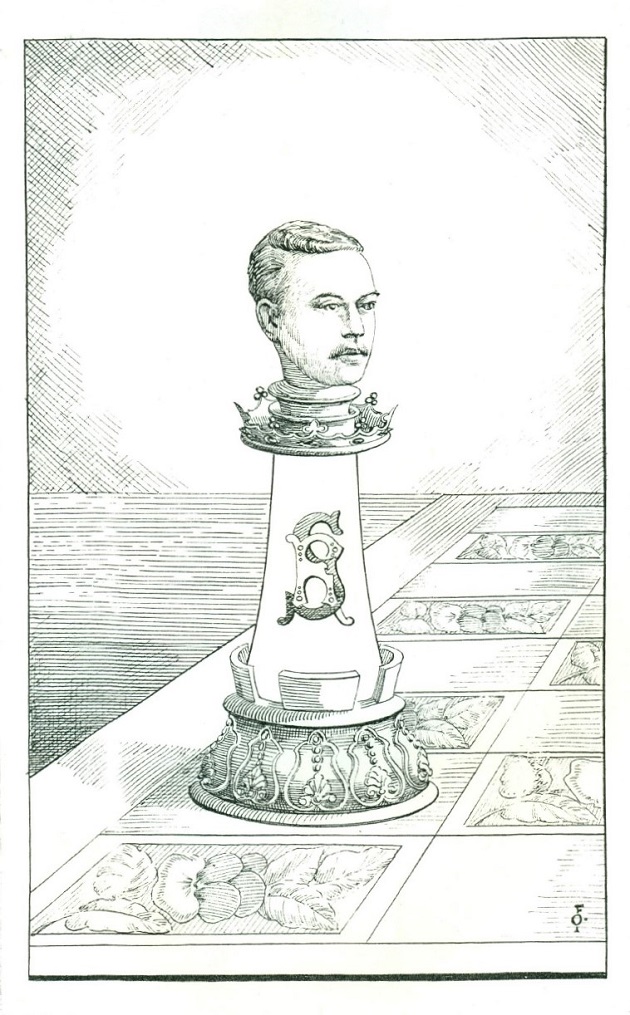

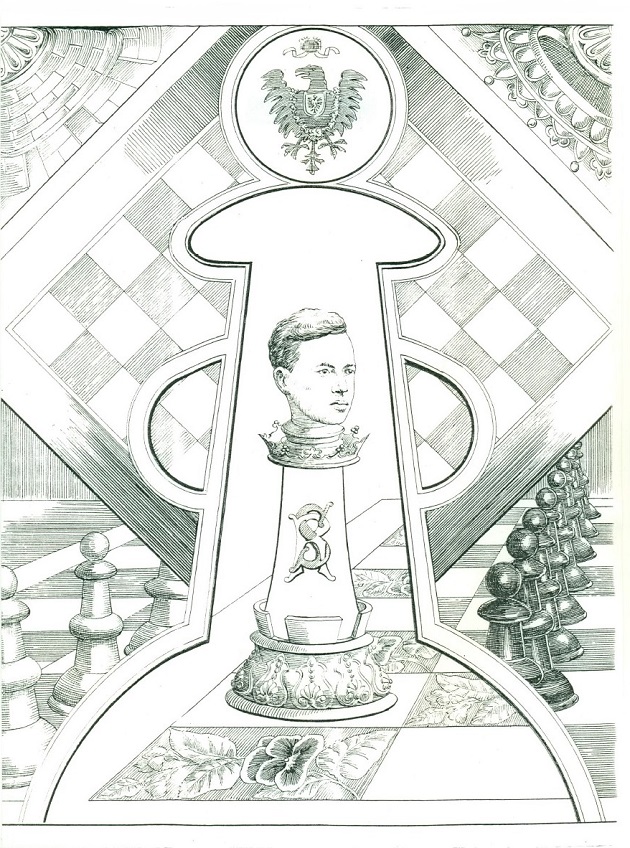

From the set ‘Le Monde des Echecs’ produced by L’Echiquier in the early 1930s.

A selection of Chess Notes items concerning Rudolf Spielmann (1883-1942).

***

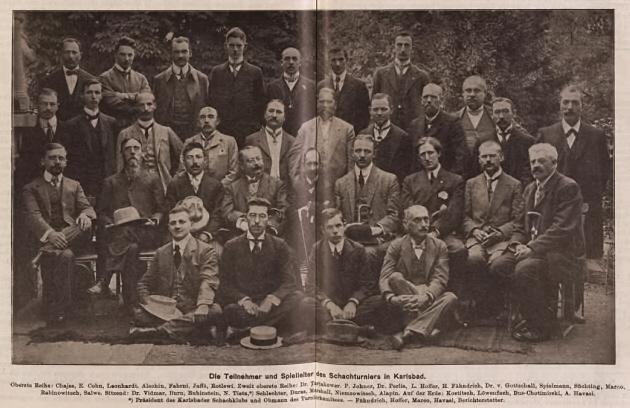

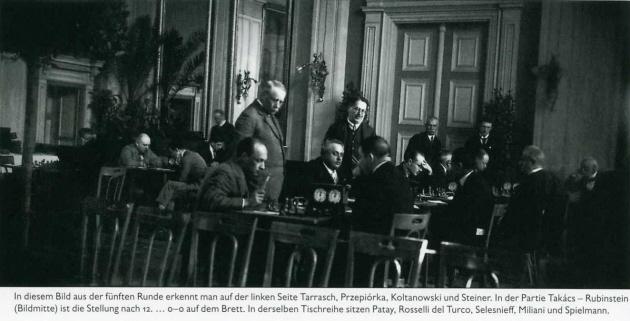

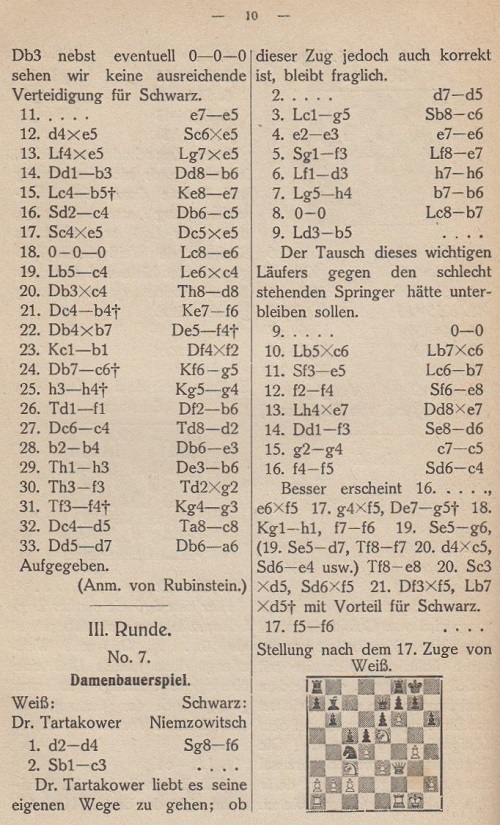

From Nimzowitsch’s book on Carlsbad, 1929 (Dover Publications, New York, 1981):

‘No matter how much we have tried to convince Spielmann of the impossibility of surviving on nothing more than developing and attacking moves (and I have tried hardeup of all, through my books and our conversations), still he tries, almost as a matter of principle, to avoid the necessity of defense!’ (page 32)

‘... Spielmann is, in fact, the hardest-working of all the masters, continually searching out the flaws in his game and striving to eliminate them.’ (page 63)

(511)

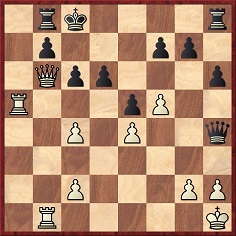

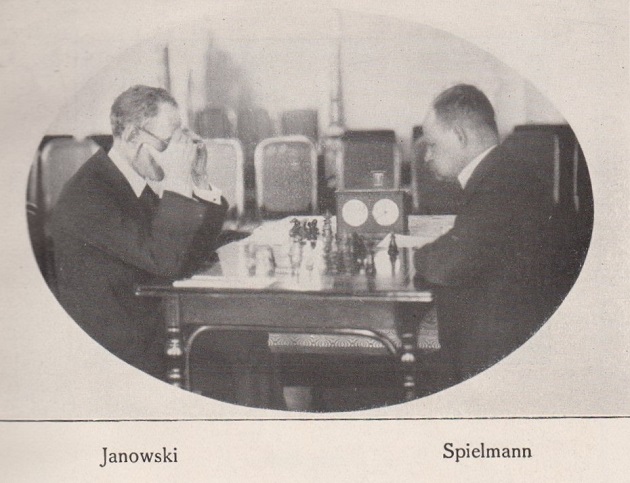

From the Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1926, pages 106-107, a position from the Spielmann-Janowsky game at the Semmering tourney of that year:

White played 37 b7, putting everything en prise. The other point of interest is the continuation, a rare example of two queens against a queen and two rooks:

37...Rxc1 38 b8(Q)+ Rd8 39 Qb6 Kf7 40 a5 Rcc8 41 f5 gxf5 42 a6 Rd5 43 Qf4 Rd7 44 Qb3 Ke8 45 Qe5 Rd5 46 Qh8+ Kd7 47 Qb7+ Rc7 48 Qhc8+ Kd6 49 Qb6+ Resigns.

(697)

The following game, so awful that it cries out for publication, was probably the quickest victory of Spielmann’s career. We take the score from the tournament book by Lachaga:

Rudolf Spielmann – B. Stupan

Maribor, 1934

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 e6 6 Ndb5 Qa5 7 Bd2 Qd8 8 Bf4 e5 9 Bg5 Resigns.

The players’ times are given: 0.10’ and O.56’.

(914)

The game below is one of the forgotten gems of chess. It appears in none of the dozens of ‘standard’ anthologies that we have consulted, yet contains a sparkling and original sequence of major piece sacrifices. The occasion was a simultaneous display (+25 –1 =5).

Rudolf Spielmann – H. Strassl

Passau, 21 April 1912

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Nc6 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Bg5 d6 6 Nge2 Bg4 7 f3 Be6 8 O-O Bc5+ 9 Kh1 Nd4 10 f4 h6 11 Bxf6 Qxf6 12 f5 Bxc4 13 dxc4 Nxe2 14 Nd5 Qh4 15 Qxe2 O-O-O 16 b4 Bb6 17 a4 c6 18 Nxb6+ axb6 19 a5 bxa5 20 Rxa5 Kc7 21 b5 Ra8 22 b6+ Kxb6 23 Rb1+ Kc7 24 Qe3 Rab8 25 Qb6+ Kc8

26 Ra8 Qe7 27 Qxc6+ Qc7 28 Rxb7 Resigns.

Source: Schachjahrbuch für 1912 by Ludwig Bachmann, pages 91-92.

(1555)

It is frequently stated that Rudolf Spielmann was very mild-mannered, in stark contrast to his fiery attacking style over the board. On page 199 of the September 1981 CHESS Euwe described him as follows: ‘Very pleasant, though a little inclined to complain about things. He has often stayed with me. He was rather a dreamer ...’

One novel complaint made by Spielmann (according to page 18 of P. Michel’s Lachaga book on Dortmund, 1928) arose from his loss to Bogoljubow in the third round of that tournament. The trouble was that in round four Bogoljubow proceeded to lose recklessly to Dr Alfred van Nüss. Spielmann was not slow to see a malevolent pattern:

‘I am bound to believe that it is only against me that opponents display their full strength.’

In round two Spielmann had only himself to blame:

Rudolf Spielmann – Richard Réti

Dortmund, 28 July 1928

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Nc6 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Ne2 d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Bxd5 Qxd5 8 O-O Qa5 9 a3 O-O 10 Be3 Bxc3 11 Nxc3 Nd4 12 b4 Qa6 13 f4 Qc6 14 Qd2 Qxc3 15 White resigns.

Master chess contains few moves to compare with White’s 14th.

(1539)

The earlier French version of Euwe’s remarks about Spielmann quoted above:

‘Très gentil et un peu enclin à se plaindre. Il a souvent logé chez nous. Il avait un air un peu bizarre; enfant, il était tombé sur la tête ...’

Source: Europe Echecs, August 1981, page 372 (interview translated from the Dutch by J. Marguillier). The original Dutch version was published in the May 1981 issue of Schakend Nederland.

An endnote on page 259 of Chess Explorations:

C.N. 173 pointed out that Spielmann once lost 12 games in a tournament (Carlsbad, 1923).

Gordon Pollard (Wallingford, England) writes:

‘While looking through Spielmann’s games I noticed that Spence (volume two, page 81) says that Spielmann v Johner, Pistyan, 1922 escaped much publicity at the time; but the BCM published it (August 1922, page 312) and I have it in a newspaper cutting pasted into my schoolboy notebook. Spence and the BCM give Johner’s iniital as “S.”, but my cutting shows “P.”, and reference to Gaige’s Catalog suggests that his name was Paul.

R. Spielmann-P. Johner, Pistyan, 1922. Vienna Game.

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d5 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 Nf3 Be7 6 d4 O-O 7 Bd3 f5 8 exf6 Nxf6 9 O-O Nc6 10 Bg5 Bg4 11 Qe1 h6 12 Bxh6 gxh6 13 Qg3 Bd6 14 Ne5 Qe7 15 Nxd5 Nxd5 16 Qxg4+ Qg7 17 Qe6+ Kh8 18 Rf7 Resigns.

Spence demonstrates a win for White after 18...Rxf7 but does not mention 18...Nf4, threatening mate. Now if 19 Ng6+ then 19...Qxg6 and Black wins. White’s best seems to be 19 Rxf4, when after 19...Bxe5 20 Rxf8+ Rxf8 21 dxe5 Nxe5 a win for White is not readily demonstrable. This is perhaps another instance of premature resignation.’

A few comments of our own:

i) That Black was Paul (as opposed to Hans) Johner is confirmed by the tournament book. We know of no S. Johner.

ii) The game may have received little publicity because the tournament book (page 149) castigated White’s 12th move. Moreover, it gave 14...Qe7 a double question mark, recommending 14...Nxd4 15 h3 Qe7 as a way of curbing the attack. The BCM awarded 12 Bxh6 an exclamation mark.

iii) Although the BCM and, for instance, Chess, More Miniature Games by J. du Mont (page 74) give 16...Qg7, the tournament book records that Black played 16...Qg5. If 16...Qg5 was the move played, then 18...Nf4 would leave open a mate in one.

(1563)

‘The late master [Réti] was one of my most dangerous opponents, and I must honestly admit that he surpassed me in terms of richness of ideas in the opening. In almost every game he played against me he invented something new. Yet perhaps his strength lay not so much in the discovery of a new move or a hitherto unknown tactical finesse as in a new strategy. Very frequently, and within just a few moves, I would find myself in a lost position against him without knowing exactly how it had happened.’

Spielmann annotated ‘one of the best games Réti played against me’, from the Vienna, 1923 tournament (although he gave the date as 1920, the opening move-order as 1 Nf3 e6 2 c4 d5 and the conclusion as ‘28 a3 and White won quickly’). His notes concluded, ‘an excellent game, typical of Réti’s style’.

Source: L’Echiquier, August 1929, pages 338-339.

The full score is given below:

Richard Réti – Rudolf Spielmann

Vienna, November 1923

Réti’s Opening

1 Nf3 d5 2 c4 e6 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 c5 5 cxd5 exd5 6 d4 Nc6 7 O-O cxd4 8 Nxd4 Bc5 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 Qc2 Qb6 11 Nc3 Bd4 12 Na4 Qb5 13 Rd1 Be5 14 Be3 O-O 15 Rac1 Ba6

16 Nc5 Rab8 17 Nd3 Nd7 18 Bxa7 Rb7 19 Nxe5 Nxe5 20 Bd4 f6 21 Bxe5 fxe5 22 Qxc6 Qxe2 23 Bxd5+ Kh8 24 Bf3 Qb5 25 Qxb5 Rxb5 26 Be2 Ra5 27 Bxa6 Rxa6 28 a3 h6 29 Rd7 Raf6 30 Rc2 Rf3 31 Re7 R8f5 32 Re2 Rb3 33 R7xe5 Rxe5 34 Rxe5 Rxb2 35 a4 Ra2 36 a5 Kh7 37 h4 Kg6 38 h5+ Kf6 39 Rb5 Ra4 40 Kg2 Ke6 41 Rb6+ Kf7 42 a6 Ra5 43 Rb7+ Kf6 44 a7 Ra4 45 f4 Ra3 46 Kf2 g6 47 Rb6+ Kf5 48 Rxg6 Rxa7 49 Rxh6 Ra2+ 50 Kf3 Ra3+ 51 Kg2 Kg4 52 Rg6+ Kxh5 53 Rg5+ Kh6 54 Kh3 Rb3 55 Ra5 Kg6 56 Kg4 Rc3 57 Ra6+ Kg7 58 Kh4 Resigns.

(2488)

E. Werner – Rudolf Spielmann

Occasion?

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Nf3 d6 5 d3 Bg4 6 Be3 Nd4 7 Bxd4 Bxd4 8 h3 Bh5 9 g4 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Bg6 11 Qb1 Qc8 12 h4 Qxg4 13 Qxb7 Qxf3 14 Bb5+ Ke7 15 Qxc7+ Kf8 16 Qc6 Qxh1+ (Nimzowitsch pointed out that Black should have played 16…Rd8, and if 17 Qc7 then 17…Qxh1+, followed by 18…Qxh4.) 17 Kd2 Qxa1 18 Qxa8+ Ke7 19 Qe8+ Kf6 20 Qd8+ Resigns.

Source: Tidskrift för Schack, July-August 1920, page 143.

When this game (C.N. 2542) was added on page 73 of A Chess Omnibus, we pointed out that it was played in an eight-game simultaneous exhibition.

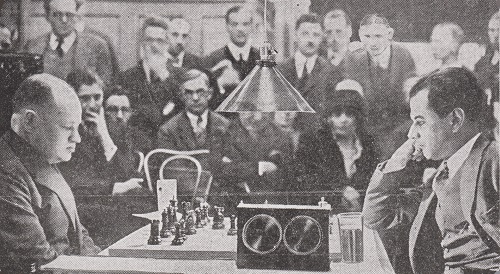

As mentioned in C.N. 3405, the Semmering, 1926 tournament book by Robert Laseker (published in Mährisch-Ostrau in 1934) contains the following photograph of Gilg and Spielmann:

C.N. 4532 added that when the picture was published on page 143 of the November 1926 American Chess Bulletin the onlooker was identified as ‘Washburn Jr., son of the American Ambassador in Vienna’.

We note from Amazon.com that Everyman Chess plans to publish a book entitled Rudolph Spielmann Master of Invention by Neil McDonald in December 2005. There should, therefore, be time for the master’s forename to be corrected to Rudolf.

Rudolf was the spelling used by Jack Spence in his Spielmann trilogy, although confusion arose when the Chess Player became the publisher (i.e. with Rudolph on the front cover and Rudolf on the title page). In contrast, Schiller’s 1996 book on Spielmann had Rudolf on the front cover and Rudolph on the title page (as well as everywhere else). However, in all the books, signatures, etc. of Spielmann himself that we have seen he used Rudolf, and no justification for Rudolph is apparent. Similarly, it is unclear on what grounds A. Soltis often, though not always, writes ‘Karl’ Schlechter.

The January-February 1907 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung (pages 8 and 10) had photographs of Schlechter and Spielmann with their signatures:

(3686)

The McDonald book has now been published, and it is good to see that Rudolph has been duly corrected to Rudolf.

(4321)

From a simultaneous exhibition:

Rudolf Spielmann – Elaine Saunders

Occasion?

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 d6 5 c4 Nf6 6 Nc3 g6 7 Be2 Bg7 8 Be3 O-O 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 h4 Qa5 11 Qd2 Ng4

12 h5 Nxe3 13 Qxe3 Qb4 14 Qd2 Be6 15 hxg6 fxg6 16 a3 Qc5 17 O-O-O Rxf2 18 b4 Qe5 19 White resigns.

This score is taken from a feature on Elaine Saunders on pages 263-264 of the Australasian Chess Review, 31 October 1938, which commented:

‘We do not intend to wallow in newspaper sensationalism about this little champion. Our readers will be more interested in the following remarks made by her father, Mr H. de B. Saunders, in response to our request for Elaine’s photo.

“I should like to stress the point that despite the reports of the ‘sensational press’ Elaine is quite an ordinary child, and not a ‘prodigy’. She is fond of all outdoor sports, and is especially keen on swimming, riding, skating and ball games. All the same, she has chess to thank for making innumerable friends both at home and abroad. She is playing three sets of correspondence chess with German opponents at the moment; all of whom are otherwise quite unknown to her.

Her successes have been almost entirely due to the kind and patient coaching of our friend Mr C.D. Locock (whose Imagination in Chess you have reviewed in the ACR). Although a veteran, Mr Locock still finds time to visit girls’ schools and teach chess; his service in this direction being entirely voluntary. Without his help, Elaine would never have risen above the ranks of ‘woodshifters’ and she bears him a considerable debt of gratitude.”’

Below is the illustration which accompanied the article in the Australasian Chess Review:

The Australasian Chess Review did not specify the occasion of the above game, but the following appeared on page 303 of CHESS, 14 May 1938, in a feature on the previous month’s tournament in Margate:

‘Twelve-year-old Elaine Saunders did it again. Beat Spielmann in his simultaneous display. She’s hard on the masters!’

(3817)

Page 98 of the 5/2005 New in Chess has the following exchange with Ruslan Ponomariov:

‘What is the best chess game you ever saw?’

‘Spielmann-Stoltz, Stockholm 1930, 5th game of the match.’

Ponomariov’s interesting choice prompts us to offer some jottings on this famous game, given here for ease of reference: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 Nf6 4 e5 Nfd7 5 Bd3 c5 6 c3 Nc6 7 Ne2 Qb6 8 Nf3 cxd4 9 cxd4 Bb4+ 10 Kf1 f6! 11 Nf4 fxe5 12 Nxe6 e4 13 Bf4

13...exf3!! 14 Bc7 Nf6 15 Nxg7+ Kf7 16 Bxb6 Bg4 17 g3? Bh3+ 18 Kg1 Kxg7 19 Bc7 Rhe8 20 Be5 Nxe5 21 dxe5 Rxe5 22 Qb3 Bc5! 23 Bf5 Bxf5 24 Qxb7+ Kg6 25 Qxa8 Re2 26 h4 Bxf2+ 27 Kf1 Be3 28 h5+ Kg5 29 White resigns.

Spielmann won the match +3 –2 =1, despite succumbing in the above brilliancy, which he annotated in the Münchner Zeitung. [See the correction in C.N. 4524 below.] Those notes were reproduced on pages 375-377 of the December 1930 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and his punctuation has been included in the game-score above. He called the encounter reminiscent of the Immortal Game, adding that he was still not altogether sure where he had made his decisive mistake and whether he already had a lost game after winning his opponent’s queen:

‘Eine Partie, die wie ein Märchen aus längst verklungenen Zeiten anmutet und an die unsterbliche Partie Anderssen-Kieseritzky erinnert. Wo aber habe ich eigentlich den entscheidenden Fehlzug gemacht? War meine Partie nach dem Damengewinn schon verloren? Diese Fragen kann ich bis heute nicht restlos beantworten und man sieht wieder, wie unergründlich tief und rätselvoll das Schachspiel trotz aller Fortschritte geblieben ist.’

Annotating the game on pages 86-87 of the February 1931 BCM J.H. Blake commented:

‘Spielmann generously says in his column in the Münchner Zeitung that his opponent’s conduct of this game reminds him of Anderssen’s “Immortal Game”; but this will be considered in some quarters as extravagant. In view of the course of the game a juster comparison would be with the great 50th game between Labourdonnais and McDonnell, in which the latter on his 13th move sacrificed his queen for two minor pieces and won on the 36th move.’

Gösta Stoltz

Tidskrift för Schack (December 1930, pages 273-274) gave the Spielmann v Stoltz game with a Swedish translation of Spielmann’s notes, and fairly detailed annotations by E.E. Böök appeared in his two monographs on the victor, i.e. on pages 40-42 of Schackmästaren Gösta Stoltz (Stockholm, 1947) and on pages 30-32 of Stormästaren Gösta Stoltz (Stockholm, 1968). We have yet to ascertain whether Stoltz himself annotated the game anywhere.

(3845)

From Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden):

‘I have never seen the Spielmann v Stoltz game annotated by Stoltz himself. Eero E. Böök’s remark on 1...e6 was: “According to Stoltz this was the first time he played the French

Defence in a tournament [sic] game.”

Some of Böök’s other comments in Schackmästaren Gösta Stoltz (Stockholm, 1947) are of interest:

3...Nf6: “After the game the move was considered finally refuted. This is correct, but the evidence submitted is wrong, as we shall soon see.”

12...e4!?: “In reality a decisive mistake! Nine years after this game was played Keres proved that Black obtains a superior game after the surprising pawn sacrifice 12...Nf6! The idea is rather simple, a real Columbus egg, but it is strange that nobody thought of the move, despite this elegant game having been published in all chess magazines and columns all over the world.”

In the second edition (Stockholm, 1968) Böök’s annotations were different:

3...Nf6 No comments ...

12...e4!: “Nor can Black save the game with 12...Nf6!?, which was mentioned by Keres as a refutation. In the game Vasilchuk v Chinarev, Moscow, 1962 White obtained a decisive advantage after 12...Nf6!? 13 Nxg7+ Kf8! 14 Bh6 Kg8 15 Qc1! Ng4 16 Nh5 (16 Nf5! is even stronger.) 16...Be7 17 h3 Nb4 18 hxg4 Nxd3 19 Qd2, etc. Stoltz’s move in the game, for a long time considered wrong owing to Keres’s ‘refutation’, is a brave try to save a seemingly hopeless game.”’

(3848)

We are grateful to Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) for a correction to C.N. 3845: Stoltz won the 1930 match against Spielmann, with a score of +2 –1 =3. Our correspondent quotes page 358 of the December 1930 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and we add the following from page 266 of the Swedish magazine Schackvärlden, November 1930: ‘Stoltz besegrade Spielmann med 3½ p. mot 2½’. It is curious that some later secondary sources gave Spielmann as the winner, by +3 –2 =1. See, for instance, page 342 of the Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi by A. Chicco and G. Porreca (Milan, 1971).

(4524)

From Calle Erlandsson:

‘I know only three games from the match between Spielmann and Stoltz, all annotated by Spielmann in Tidskrift för Schack, December 1930, pages 269-274. Play went as follows:

Game 1 (12 November): Spielmann v Stoltz ½-½ (32)

Game 2 (13 November): Stoltz v Spielmann 1-0

Game 3 (14 November): Spielmann v Stoltz 1-0

Game 4 (16 November): Stoltz v Spielmann ½-½ (38)

Game 5 (17 November): Spielmann v Stoltz 0-1 (28)

Game 6 (18 November): Stoltz v Spielmann ½-½.The Stockholm Schacksällskap had organized an international tournament to celebrate Ludwig Colllijn’s 25th year as club president. The tournament (20-25 October 1930) had seven players; Kashdan, who lost to Spielmann, won with 4½ points (+4 –1 =1). Then came Bogoljubow and Stoltz with 4 points, followed by Ståhlberg (3), Spielmann (2½), Rellstab (2) and Lundin (1). Spielmann lost to Stoltz and Bogoljubow.

The Collijn Jubilee continued with matches, but Bogoljubow went to Finland for three weeks. From 30 October to 5 November Spielmann and Kashdan played matches against the Swedes. Stoltz beat Kashdan +2 –1 =3, and Spielmann won against Ståhlberg +4 –1 =1). Later Stoltz played Spielmann (see above), and afterwards Spielmann beat Lundin +4 –0 =2.’

(4528)

Page 75 of Rudolf Spielmann Portrait des Schachmeisters in Texten und Partien by M. Ehn (Koblenz, 1996) has a photograph of Spielmann’s grave in Stockholm.

There seem to be few photographs of Spielmann taken during his last years. Offhand, the latest we recall seeing is on page 54 of Mina Bästa Partier by Harald Malmgren (Örebro, 1953). It shows Spielmann facing Malmgren in a simultaneous exhibition:

(4128)

In C.N. 3194 (see pages 280-281 of Chess Facts and Fables) a correspondent mentioned a report in Alexander Münninghoff’s book on Max Euwe (pages 155-156 of the Dutch original and page 112 of the English edition) that in 1935 Euwe played, while preparing to face Alekhine for the world championship, a secret ten-game match against Spielmann. Below is Münninghoff’s text:

‘… just before the final secondary school exams he met Spielmann for a drawing-room match. This latter piece of practical training went quite badly for him; we don’t know whether he found it hard to concentrate because of his schoolwork or whether he had underestimated Spielmann, who was clearly past his prime as a chessplayer, but the fact remains that the peripatetic Austrian veteran claimed this secret ten-game match in fairly superior style with 6-4 (+4 –2 =4).’

Max Euwe

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) quotes three reports from 1935 which show that the existence of the match was not a secret and that, moreover, there is no unanimity as to who won the contest:

1) From page 402 of the September 1935 BCM:

‘In preparation for his match for the world championship, Dr Max Euwe has had a practice match with R. Spielmann, whom he beat by 4-2, with 2 draws.’

2) Pages 282-283 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 September 1935 also referred to the Euwe v Spielmann match, without giving the result:

‘Der holländische Vorkämpfer nimmt den Kampf sehr ernst; so hat er sich in Trainingskämpfen mit Spielmann und Eliskases geschult und in Wien theoretische Studien getrieben.’

3) The December 1935 Wiener Schachzeitung had an article reviewing the past year, and on page 354 it was stated that Spielmann had defeated Euwe:

‘... in einem Übungswettkampf schlug er Euwe 4:2 ...’

We can add that in De Groene Amsterdammer (an article reproduced on pages 185-186 of the June 1935 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond) Salo Landau wrote that Euwe and Spielmann were playing a training match in the absence of the press and witnesses, so that Alekhine would not have the benefit of seeing the games:

‘Het is bekend, dat Euwe op het oogenblik een oefenmatch speelt met Spielmann. Pers noch toeschouwers worden hierbij toegelaten, uit vrees, dat Aljechin de partijen te zien zal krijgen en daardoor het geheim der vorderingen van den Nederlandschen kampioen te weten zou komen.’

Can readers shed further light on the Euwe v Spielmann match?

(4174)

From W.E. Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). The figure refers to the item number, given that the pages were unnumbered:

237. ‘Spielmann plays always like an educated cave-man, who fell asleep several thousand years ago, – and woke up quite lately in the Black Forest.’

C.N. 1928 (see page 230 of Chess Explorations) suggested that Bruce Pandolfini broke new ground on page 36 of Chess Openings: Traps and Zaps (New York, 1989) by indicating that Rudolf Spielmann lived to be 109:

In fact, the following had already appeared on page 158 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

(4857)

Further to the furniture-destruction story discussed in Chess with Violence, Mark Nieuweboer (Moengo, Surinam) refers to an article on Spielmann by Hans-Wilhelm Fink on pages 111-149 of Rudolf Spielmann Portrait des [eines] Schachmeisters in Texten und Partien by Michael Ehn (Koblenz, 1996). Pages 127-128 quote most of what Hans Kmoch wrote on pages 61-62 of his book Die Kunst der Bauernführung (Berlin-Frohnau, 1956). The relevant part of Kmoch’s book is the final paragraph of that section:

The passage in question (over 60 lines) is absent from the English edition of Kmoch’s book, Pawn Power in Chess (New York, 1959). Our correspondent asks whether Kmoch was present during the Carlsbad, 1923 tournament.

We add that Michael Ehn’s book on Spielmann is admirably researched.

(5013)

Addition on 24 January 2024:

In reaction to our feature article, on 12 July 2023 Michael Lorenz (Vienna) wrote ‘I beg to differ’ regarding our comment in C.N. 5013 that ‘Michael Ehn’s book on Spielmann is admirably researched’. He mentioned a few errors, and on 14 July 2023 we replied to him regarding his brief message:

I shall willingly quote it as an addition to the feature article – as your text stands or with any other examples you may care to add. Please let me know your preference.

We received no reply.

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) has found various observations/predictions by Rudolf Spielmann in Sonntagsbeilage der Augsburger Postzeitung of 25 June 1927, page 104:

For a larger version, click here.

Two passages highlighted by our correspondent are given below, together with our translations:

‘Trotzdem Aljechin in New York teilweise glänzend spielte, würde es mich wundern, wenn er in dem im Herbst bevorstehenden Kampf um die Weltmeisterschaft gegen Capablanca auch nur eine Partie gewinnen würde.’ [Although Alekhine sometimes played brilliantly in New York, I should be surprised if, in this autumn’s world championship match against Capablanca, he were to win even a single game.]

‘Capablanca freilich hält mit seinen eisernen Nerven die fünfstündige Spielzeit glänzend durch. Schon wegen dieses Punktes allein glaube ich, daß Aljechin in seinem bevorstehenden Wettkampf keine ernstliche Chance hat.’ [Capablanca certainly maintains his iron nerve throughout the five hours of play. For that reason alone I believe that in his forthcoming match Alekhine has no serious chance.]

(5338)

Page 117 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960) suggested that this was a frequent complaint by Spielmann:

‘Away from the chessboard he was a timid and modest man, always plaintively wondering out loud why every opponent played his best chess against him.’

Wanted: other instances of the grievance being expressed by Spielmann.

Rudolf Spielmann

(5589)

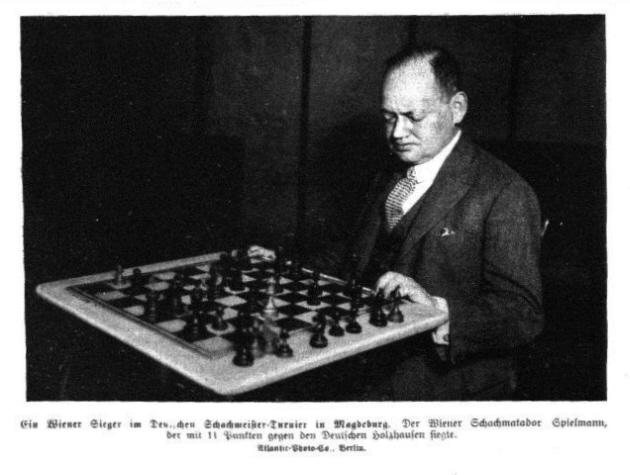

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) has provided a photograph of Rudolf Spielmann at Magdeburg, 1927, from page 4 of Wiener Bilder, 7 August 1927:

(6131)

Addition on 8 August 2025:

The two subsequent C.N. items below indicate that the Spielmann photograph dates from a tournament in Berlin in November 1926:

We are authorized to show this portrait of Akiba Rubinstein which is held by the Jewish Museum of Belgium:

(12131)

From Philip Jurgens (Ottawa, Canada):

‘The portrait of Rubinstein is intriguing. Although the location and date may seem unclear, I recall the photograph of Rudolf Spielmann provided by Jan Kalendovský in C.N. 6131 in connection with Magdeburg, 1927, from page 4 of Wiener Bilder, 7 August 1927:

It is not only the chessboard and background that are similar in the two photographs. Remarkably, even the position appears to be the same, showing the conclusion of the fourth-round game in Berlin, November 1926 in which Rubinstein was White against Grünfeld. The handwritten note on the bottom border of the Rubinstein picture matches the credit on the Spielmann photograph: “Atlantic Photo Co., Berlin”.

Rubinstein did not participate in Magdeburg, 1927, which Spielmann won. However, they did both play in the November 1926 tournament in Berlin, meeting in round one.’

(12187)

A photograph from page 273 of the 13 March 1936 issue of CHESS:

(6404)

Richard Benjamin (St. Louis, MO, USA) asks whether information is available about a photograph (featuring Rudolf Spielmann) on a postcard in his possession:

(7195)

Peter Holmgren (Stockholm) sends this photograph, found in a local archive in Gävle:

It appears to show Rudolf Spielmann giving a simultaneous exhibition in the early twentieth century. Can further information be found?

(10091)

Black to move. Should he castle?

Richard Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) draws attention to this position, which would have arisen in the game Spielmann v Nimzowitsch, Stockholm, 1920 if White had played Nimzowitsch’s suggestion of 17 Nf4-d3 (instead of the move actually played, 17 Be3).

Position after 16...Qg5

On page 364 of The Praxis of My System (London, 1936) Nimzowitsch gave various lines beginning 17 Nd3 Qg1+.

However, Mr Hervert points out that on page 20 of A Complete Defence for Black by Raymond Keene and Byron Jacobs (London, 1996) there is no mention of 17...Qg1+ in reply to 17 Nd3. Instead, the book states in the note to 17 Be3:

‘White’s best is 17 Nd3!, when Black should play quietly with 17...O-O-O! when his prospects are still not bad. He is ahead in development with two pawns for a piece and with White somewhat tied up.’

Except, of course, that White can somewhat untie himself with 18 Bxg5, winning the queen for nothing.

(7210)

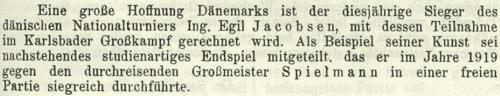

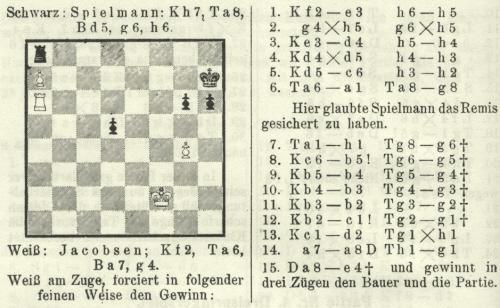

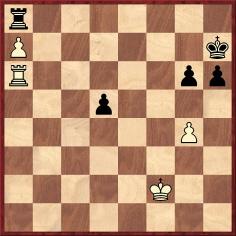

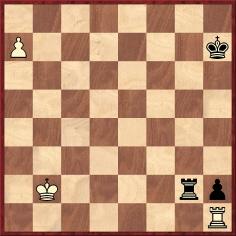

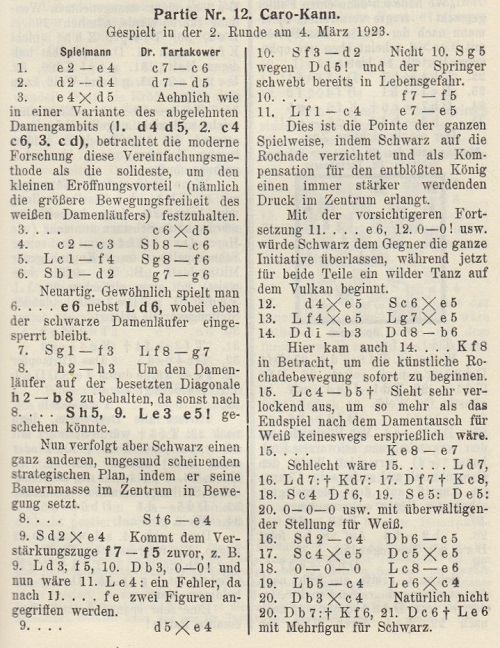

Below is an extract from an article by Tartakower (‘Schachmeister Dr Tartakower in Dänemark’) on pages 3-6 of the March 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung:

The play in this offhand game is of much interest:

1 Ke3 h5 2 gxh5 gxh5 3 Kd4 h4 4 Kxd5 h3 5 Kc6 h2 6 Ra1 Rg8 7 Rh1 Rg6+ 8 Kb5 Rg5+ 9 Kb4 Rg4+ 10 Kb3 Rg3+ 11 Kb2 Rg2+

12 Kc1 Rg1+ 13 Kd2 Rxh1 14 a8(Q) Rg1 15 Qe4+ and wins.

Egil Jacobsen died on 27 March 1923, a fortnight after the Copenhagen tournament (Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1923, page 77).

(7235)

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) notes that according to pages 118-119 of Skakbladet, April 1919 Spielmann had travelled through Denmark, staying in Copenhagen for two days (exact dates not specified by the Danish magazine). He gave two simultaneous displays, in the Studenterforeningen (Students’ Chess Club) and, the following day, in the Industriforeningen (Industrial Union Chess Club). His results were +19 –5 =6 and +19 –2 =6, respectively, but Egil Jacobsen was not among those named as winning or drawing. The full game-score of Jacobsen v Spielmann has not been found, and it is unclear where Tartakower obtained the ending for use in the Wiener Schachzeitung.

(7242)

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) informs us that he investigated this Moscow, 1935 photograph in the 1980s and drew up the key given below:

Mr Mokrý also mentions an article which he has written on the two variations of the Russian-language tournament book and the subsequent removal of Krylenko’s name and contribution. See under ‘Moscow 1935’ in the ‘Collector’s Corner’ of our correspondent’s webpage.

(7286)

From Photographs of Capablanca, a feature article which appealed for better copies of a number of images in Soviet publications:

Source: Moscow tournament bulletin, 64, 13 June 1936 and 64, 16 June 1936, page 1

In C.N. 7301 Philippe Pierlot (Le Perchay, France) provided a good-quality copy (source not yet identified):

From page 60 of the March 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

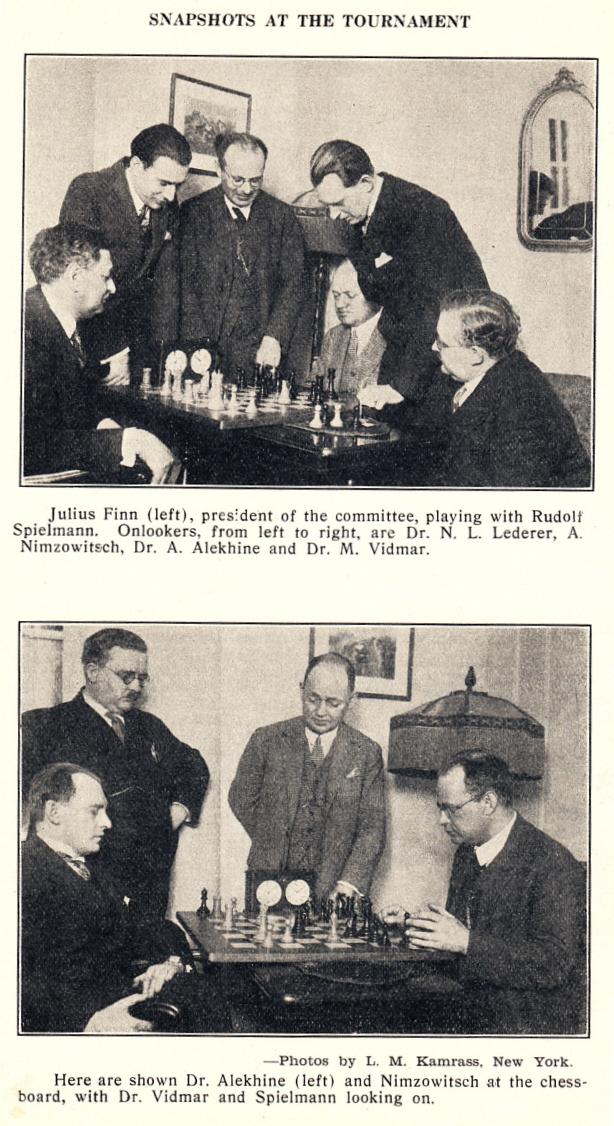

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), who gave the first photograph on page 226 of his book Julius Finn (Jefferson, 2010), informs us that he has now acquired a much better copy:

Our correspondent identifies the position as arising in analysis of the third-round game at New York, 1927 between Vidmar and Spielmann:

(7602)

The two games below, played in simultaneous displays given by Spielmann, come from pages 121-128 of Sonja Graf’s Así juega una mujer (Buenos Aires, 1941). The book includes Tarrasch’s annotations.

Sonja Graf – Rudolf Spielmann

Munich, 1932

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 c6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 a4 Bf5 6 e3 Na6 7 Bxc4 Nb4 8 O-O e6 9 Ne5 Be7 10 Qe2 O-O 11 e4 Bg6 12 Nxg6 hxg6 13 Be3 Qa5 14 f4 Qh5 15 Qxh5 gxh5 16 Rad1 Rad8 17 h3 Rd7 18 Kh1 Rfd8 19 Bb3 h4

20 f5 exf5 21 Rxf5 g6 22 Rf3 Kg7 23 Rdf1 Nh5 24 Rxf7+ Kh8 25 R1f3 Ng3+ 26 Kg1 Bd6 27 Bg5 Rxf7 28 Rxf7 Resigns.

Sonja Graf – Rudolf Spielmann

Munich, 1932

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 e6 2 c4 Nf6 3 Bg5 h6 4 Bd2 Ne4 5 Nf3 Nxd2 6 Nbxd2 d5 7 e3 Be7 8 Bd3 O-O 9 O-O Nd7 10 Qe2 Nf6 11 c5 c6 12 Ne5 Bd7 13 f4 Be8 14 g4 Nd7 15 Ndf3 Nxe5 16 Nxe5 Bf6 17 f5 exf5 18 gxf5 Qe7 19 Ng4 Bd7 20 Qg2 Kh8 21 Qh3 Bg5 22 Rf3 Rae8 23 Re1 Bh4 24 Ref1 Bg5 25 Rg3 Bh4 26 Rg2 Bg5 27 Rf3 Qd8 28 b4 a5 29 a3 axb4 30 axb4 Qa8

31 Nxh6 Bxh6 32 Rxg7 Qa1+ 33 Rf1 Qxf1+ 34 Kxf1 Kxg7 35 f6+ Kxf6 36 Qxh6+ Ke7 37 Qd6+ Kd8 38 Bf5 Resigns.

(7622)

As mentioned in our feature article on Tarrasch, in an interview on page 12 of the Chess World, 1 October 1932 Spielmann described him as ‘the greatest chess leader of all times, past and present.’

Regarding Spielmann’s preferred first move as White, Reinfeld wrote on page 117 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘There is an interesting story related to the following fine finish, played in the Trentschin-Teplitz tournament of 1928. Réti started the game with 1 P-Q4, and Spielmann was so impressed by the overwhelming drubbing that he received that he thereupon started playing 1 P-Q4 after a lifetime of beginning with 1 P-K4.’

Is there any substance to the story? When the game was published on pages 85-86 of Reinfeld and Chernev’s Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) the suggestion was more speculative:

‘One of the many sensations of the great Carlsbad (1929) tournament was Spielmann’s belated renunciation of his beloved P-K4 in favor of Queen’s Pawn openings. The suddenness of the change was no less astonishing than the stubbornness with which Spielmann had previously clung to the King’s Gambit and similar openings. Perhaps the clue to this surprising change will be found in the overwhelming drubbing administered by Réti in the following elegant game.’

The Réti v Spielmann game, played on 23 May 1928, was annotated by Spielmann on pages 146-147 of the May 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung. His closing remark may be quoted in passing:

‘Gerade gegen mich spielt Réti immer das beste Schach. In welchem Gegensatz dazu steht sein auffallend schwaches Spiel in mehreren anderen Partien des gleichen Turniers.’

The Carlsbad tournament began over a year after the Réti v Spielmann game was played. During the intervening period, Spielmann played 1 d4 a number of times: v Bogoljubow at Bad Kissingen, 1928, v Vajda at Budapest, 1928 and v Réti and Capablanca at Berlin, 1928. He had also played it occasionally earlier in his career.

(7852)

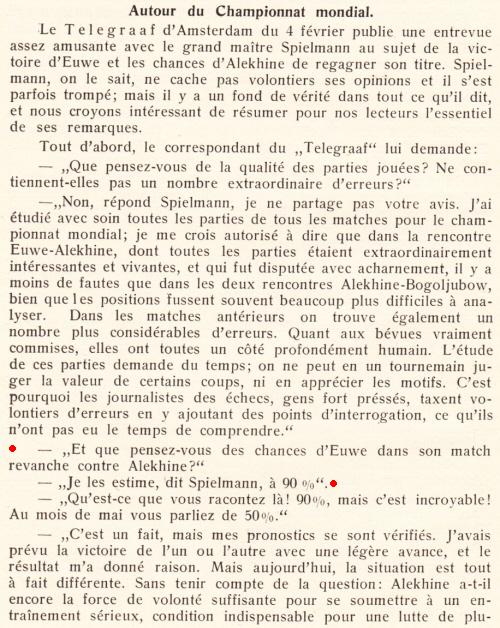

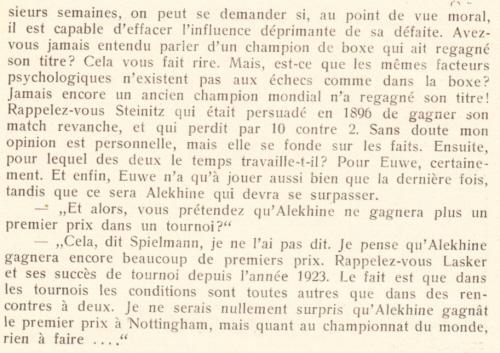

C.N. 7929 asked which prominent master estimated in 1936 that Euwe’s chances of retaining his world title against Alekhine were 90%. The answer is Rudolf Spielmann, as shown by an article on pages 68-69 of the May 1936 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

(7933)

‘Curious, but true chess stories’ are promised on the front cover of Fried Liver & Burning Pants by “Coach Jay” Stallings, an execrable 89-page book published in 2012. To quote from pages 19-21:

‘Chess, too, has taken its toll on the sanity of men for many years. Alekhine was a great chessplayer, but his tendency to sometimes yell and knock over the chess pieces after a loss prompted players and fans to keep their distance when Alekhine’s opponent was on verge of victory ...

... At the Carlsbad tournament in Czechoslovakia (now known as the Czech Republic) in 1923, Alekhine had worked hard, as usual, and with only two rounds remaining was comfortable in his familiar position at the top of the standings. He fully expected to stay there; after all, he had spent a lot of time carefully preparing, as he always did. And then, something for which he had not prepared happened – he lost! He had abandoned a chance for a draw and was pushing for a win when his opponent (Frederick Yates) used his queen and bishop to take advantage of Alekhine’s exposed king. Alekhine’s frustration was enormous, but, as good sportsmanship requires, he politely shook his opponent’s hand and congratulated him on his victory. Then, Alexander Alekhine calmly walked back to his hotel room and destroyed every piece of furniture in the room!’

As noted in Chess with Violence, at Carlsbad, 1923 Alekhine was defeated by Yates in round seven (of 17). He lost two other games, to Treybal in round three and to Spielmann in round 16.

Lest there be doubt, we add that it is Spielmann who dominates the front cover, and the picture also fills page 22 (headed ‘Burning Pants & a Lap Full of Soup!’, to introduce further ‘true chess stories’). Stallings uses the word ‘true’ slackly, meaning any yarn written by anyone anywhere.

(8559)

The stories about Rudolf Spielmann referred to in C.N. 8559 can be found at the start of an article by R.E. Fauber on pages 268-269 of the Chess Digest Magazine, December 1974:

This model of how not to write about chess history re-appeared on page 168 of Fauber’s book Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992).

(9165)

A detail of Spielmann from the Carlsbad, 1911 group photograph (Wiener Schachzeitung, September-October 1911, pages 304-305):

(8574)

From page 177 of The Art of Sacrifice in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann (London, 1935):

‘In the days of Anderssen, perhaps the greatest sacrificial artist of all time, a king-hunt sacrifice was no rarity.’

Spielmann’s original text is on page 77 of Richtig Opfern! (Leipzig, 1935):

‘In der Epoche von Anderssen, vielleicht des größten Opferkünstlers aller Zeiten, waren Jagdopfer keine Seltenheit.’

(8578)

Further to the references to Rudolf Spielmann in Chess: the Need for Sources, the passage below comes from page 111 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

Can the original text be traced?

(8579)

From page 3 of Meet the Masters by Max Euwe (London, 1940):

‘Ordinary mortals can envy Alekhine’s genius in the discovery of charming and startling combinations; the more skilful player who feels himself quite capable of executing such combinations has a different feeling on the subject. To quote Spielmann, who is surely competent to pass an opinion on combinative skill: “I can comprehend Alekhine’s combinations well enough; but where he gets his attacking chances from and how he infuses such life into the very opening – that is beyond me. Give me the positions he obtains, and I should seldom falter. Yet I continually get drawn games, even out of the King’s Gambit.”

Well said, Master Spielmann! Alekhine’s real genius is in the preparation and construction of a position, long before combinations or mating attacks come into consideration at all.’

In case it helps in tracing the original of Spielmann’s words, below is the relevant section of pages 2 and 3 of the Dutch edition of Euwe’s book, Zóó schaken zij! (Amsterdam, 1938):

(8603)

Just published: Die internationalen Schachturniere zu Meran 1924 und 1926 by Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, 2014), a deeply researched, luxuriously produced hardback (500 large pages). With the author’s permission two photographs are reproduced below, from pages 108 and 389 respectively:

(8657)

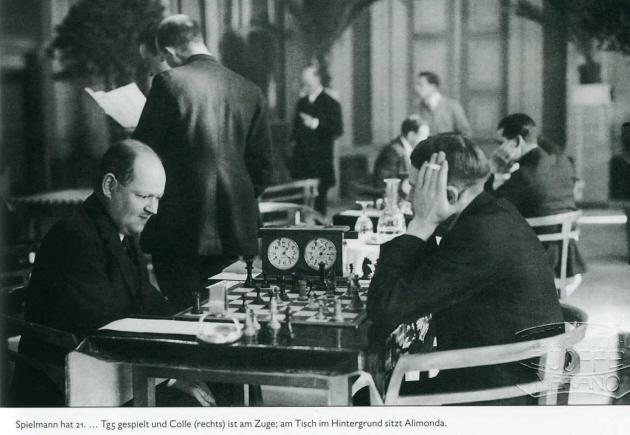

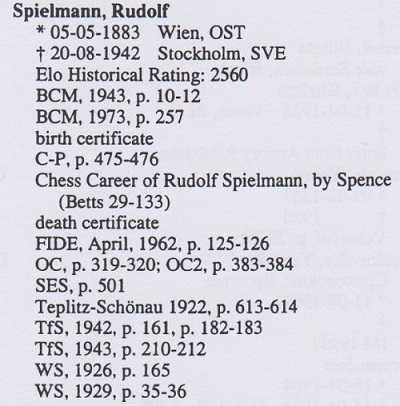

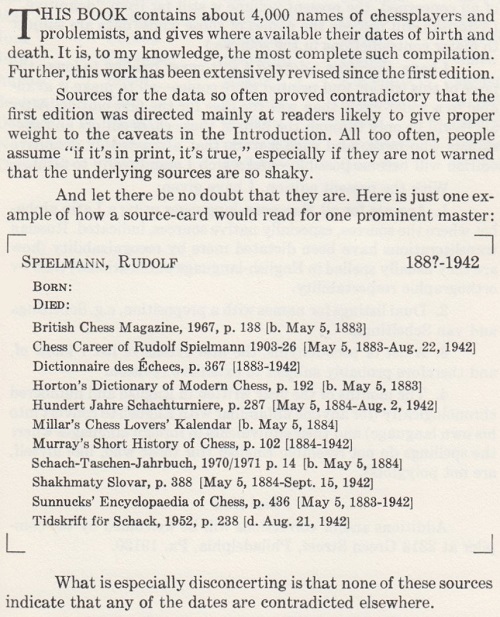

Basic biographical data about some prominent players took much time to establish, one example being Rudolf Spielmann’s date of birth. An extract from page 717 of the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

Yet a few decades ago it was not known for sure when Spielmann was born. Below is the start of Gaige’s Introduction on page i of A Catalog of Chessplayers & Problemists (Philadelphia, 1971):

Two sentences are worth highlighting:

‘All too often, people assume “if it’s in print, it’s true”, especially if they are not warned that the underlying sources are so shaky.’

‘What is especially disconcerting is that none of these sources indicate that any of the dates are contradicted elsewhere.’

(9086)

Position after 20 bxa6

‘The combination here is unique in the literature of chess games. Where else can one find a rook’s pawn on the sixth rank stronger than a queen?’

Source: page 24 of Solitaire Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1962). Horowitz had not included that curious remark when his article, ‘Spielmann Outspielmanned’, was published on page 9 of Chess Review, January 1955.

The full game-score, for ease of reference: 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 Nd7 4 Nc3 Ngf6 5 Bg5 Bb4 6 cxd5 exd5 7 Qa4 Bxc3+ 8 bxc3 O-O 9 e3 c5 10 Bd3 c4 11 Bc2 Qe7 12 O-O a6 13 Rfe1 Qe6 14 Nd2 b5 15 Qa5 Ne4 16 Nxe4 dxe4 17 a4 Qd5 18 axb5 Qxg5 19 Bxe4 Rb8 20 bxa6 Rb5 21 Qc7 Nb6 22 a7 Bh3 23 Reb1 Rxb1+ 24 Rxb1 f5 25 Bf3 f4 26 exf4 Resigns.

As shown on pages 167-168 of our book on Capablanca, the Cuban annotated the game in an article on pages 1 and 2 of the New York Times, 13 March 1927. Among his comments: ‘We have been warmly congratulated by amateurs and experts alike for the manner in which we conducted the attack.’ He also provided notes on pages 245-248 of A Primer of Chess (London, 1935).

In the 1920s, other annotators included Maróczy (Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, April-June 1927, pages 304-305) and Alekhine in Das New Yorker Schachturnier 1927. (The English translation of the notes on pages 116-117 of the ‘21st Century Edition!’ (Milford, 2011) made no attempt to capture Alekhine’s prose style.) Réti gave the game in Masters of the Chess Board.

On page 143 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942) Fred Reinfeld presented Capablanca v Spielmann as follows:

‘This might well be considered the classic Capablanca game. It shows his proverbial clean-cut and logical simplicity in its most attractive form.’

It was also the game that Harry Golombek picked for the section on Capablanca on pages 222-224 of The Game of Chess (various editions). The introduction stated:

‘Here is a game that seems perfectly natural once one has played through it; but no-one, save Capablanca, could have produced it.’

A detailed set of annotations, by John Nunn, was published on pages 149-152 of an anthology which he co-wrote with Graham Burgess and John Emms: The Mammoth Book of The World’s Greatest Chess Games (London, 1998). From the introduction:

‘Capablanca had the unusual ability to dispose of very strong opponents without any great effort. At first glance, there is little special about this game; the decisive combination, while attractive, is not really very deep. The simplicity is deceptive; a closer look shows that the combination resulted from very accurate play in the early middlegame.’

This photograph of Spielmann and Capablanca in the New York, 1927 tournament is in our monograph on the Cuban:

(9515)

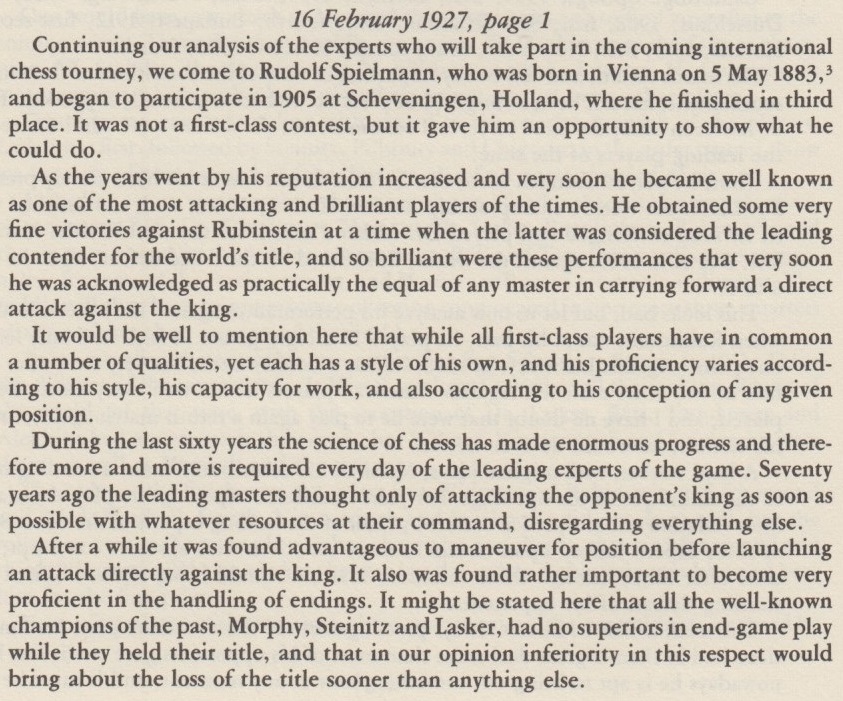

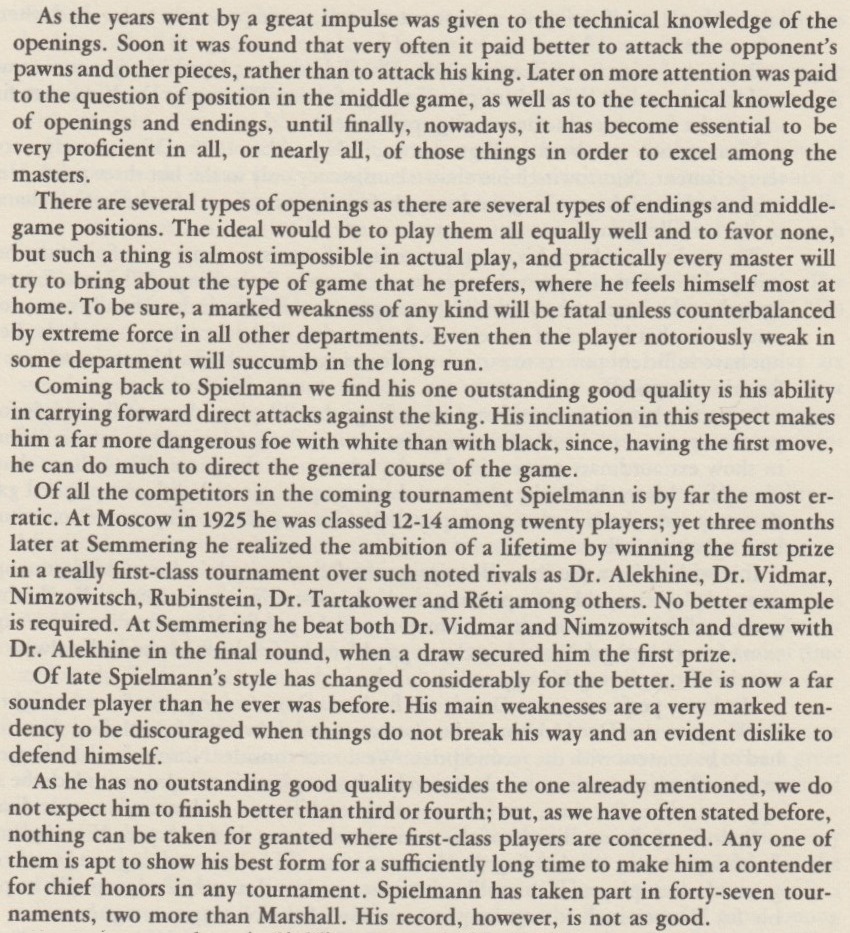

Before the New York tournament began, Capablanca wrote about Spielmann in his New York Times column of 16 February 1927, page 1. The text appears below from pages 154-155 of our 1989 monograph on Capablanca:

A claim by Fred Reinfeld on page 197 of The Joys of Chess (New York, 1961):

‘All his life long, Rudolf Spielmann looked back nostalgically to the brilliant gambit chess of his grandfather’s day.’

(9567)

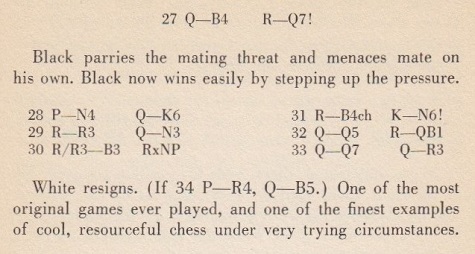

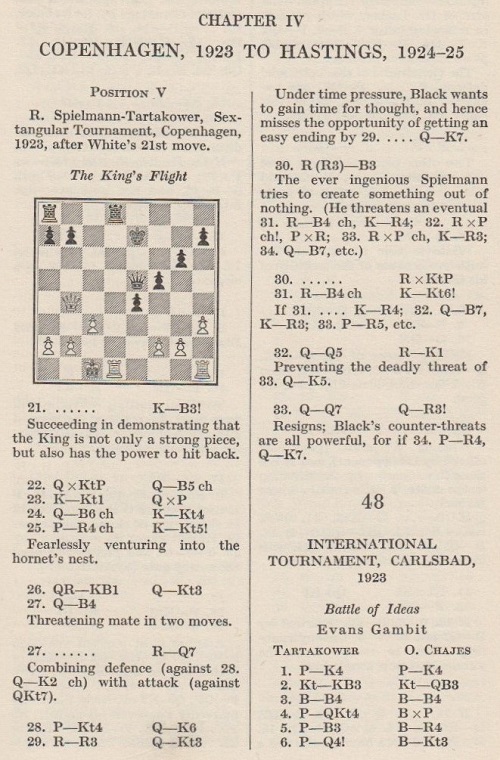

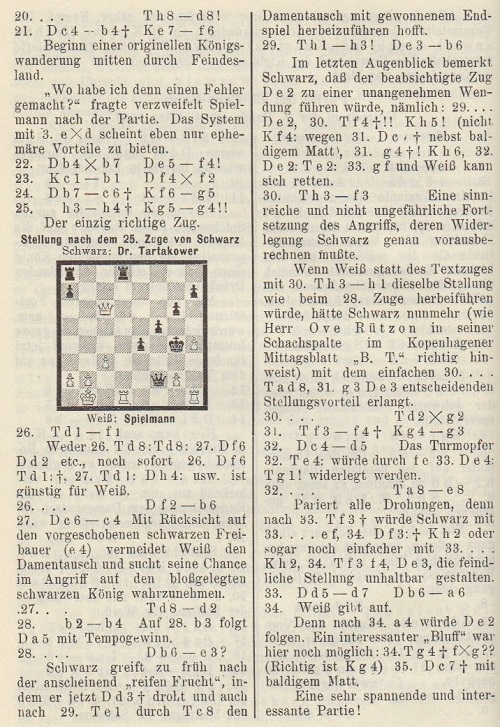

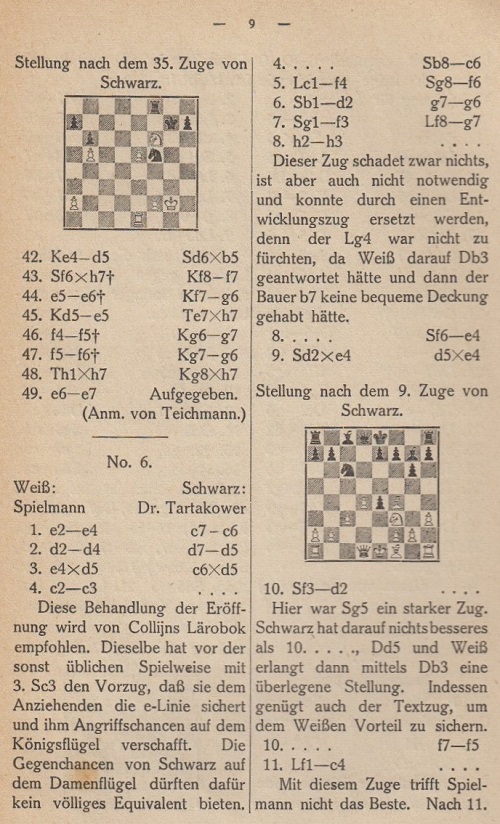

‘One of the most original games ever played, and one of the finest examples of cool, resourceful chess under very trying circumstances.’

That was the concluding remark by Fred Reinfeld about a game which he annotated on pages 69-73 of How to Play the Black Pieces (New York, 1955):

The players were not named, but the game was Spielmann v Tartakower, Copenhagen, 1923. Tartakower gave only the conclusion on page 115 of My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 (London, 1953):

The full game was annotated by Tartakower on pages 35-36 of the April 1923 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung:

The ‘bluff’ mentioned in the final note is of particular interest, and it will be seen that in both publications Tartakower gave his 32nd move as ...Ra8-e8. Reinfeld, however, put ‘...R-QB1’, and that was also the move in the tournament book, where notes by Rubinstein were given on pages 9-10:

The improbable 32...Rc8 could be answered by 33 Rxe4.

Position after 32 Qd5

The score as published by Tartakower in 1923: 1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 cxd5 4 c3 Nc6 5 Bf4 Nf6 6 Nd2 g6 7 Ngf3 Bg7 8 h3 Ne4 9 Nxe4 dxe4 10 Nd2 f5 11 Bc4 e5 12 dxe5 Nxe5 13 Bxe5 Bxe5 14 Qb3 Qb6 15 Bb5+ Ke7 16 Nc4 Qc5 17 Nxe5 Qxe5 18 O-O-O Be6 19 Bc4 Bxc4 20 Qxc4 Rhd8 21 Qb4+ Kf6 22 Qxb7 Qf4+ 23 Kb1 Qxf2 24 Qc6+ Kg5 25 h4+ Kg4 26 Rdf1 Qb6 27 Qc4 Rd2 28 b4 Qe3 29 Rh3 Qb6 30 Rhf3 Rxg2 31 Rf4+ Kg3 32 Qd5 Re8 33 Qd7 Qa6 34 White resigns.

It was played in the same tournament as the Sämisch v Nimzowitsch ‘Immortal Zugzwang’ encounter, and neither game was widely published at first.

(9679)

From page 79 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929), in the section on Rudolf Spielmann:

‘A curious feature of his record is the unevenness of his performances. He himself maintains that he plays as consistently well in tournaments where he has been less successful as in those which he has won, and he explains the difference in the results by what may almost be termed the luck of the game. If this really exists it is more applicable to the case of an attacking player, since he commits his whole game to an onslaught, the outcome of which it is in many cases impossible to foresee.’

(9715)

From the Marienbad, 1925 tournament book:

(9844)

The series of portraits by Frederick Orrett [see the references in the Factfinder] sent to us by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) continues with two incomplete pictures of Rudolf Spielmann:

(10082)

From page 136 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948):

Next, a line from a column by Robert Byrne in the New York Times, 8 October 2000:

‘In the 1930s, the great champion of the gambit, Rudolph [sic] Spielmann, wrote an article titled, “From the Sickbed of the King's Gambit”.’

On page 171 of Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992) R.E. Fauber indicated that Spielmann’s article was written in 1926.

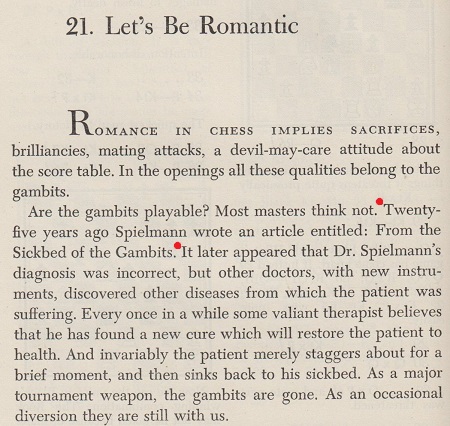

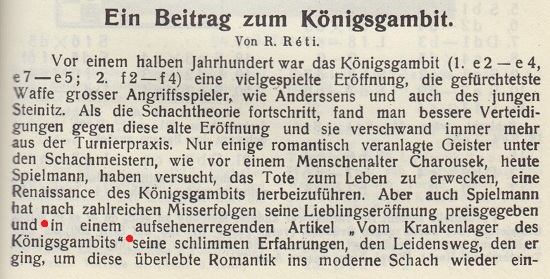

Many writers have referred to the article without any sign of having read it, and the date of its appearance is not altogether straightforward. If, as sources state, it was published in the July-September 1924 issue Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, how could Réti have mentioned it at the start of an article on pages 317-320 of the December 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung?

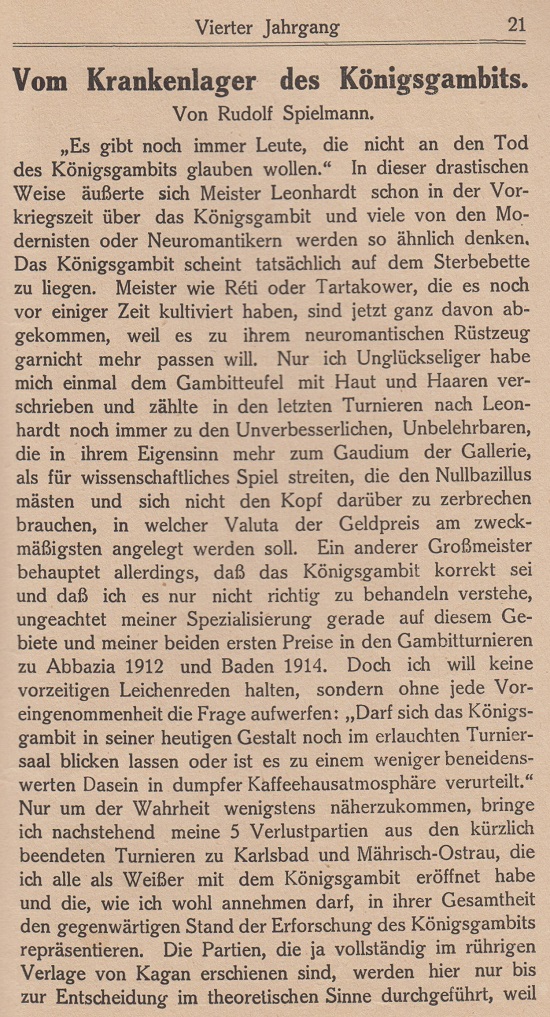

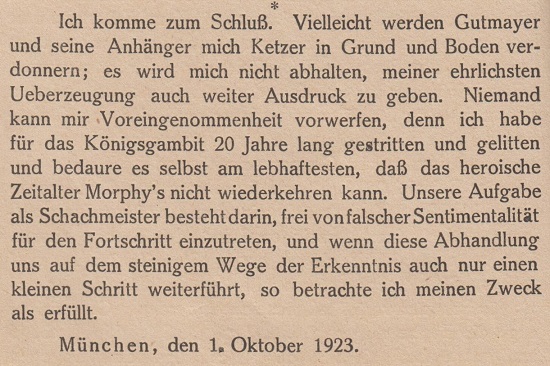

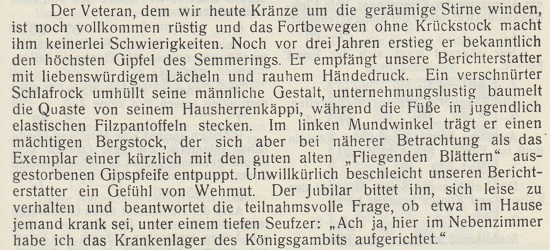

The answer is that the publication schedule of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten was even more erratic than usual, and the July-September 1924 issue comprised games and articles from 1923. Spielmann’s ‘Vom Krankenlager des Königsgambits’ appeared on pages 21-36. The first page and the conclusion are shown below, and it will be seen that the article was dated 1 October 1923.

Under the title ‘New Light on the “Falkbeer”’, P.W. Sergeant discussed Spielmann’s ‘From the Sickbed of the King’s Gambit’ article on pages 433-434 of the December 1923 BCM. The magazine had two follow-up articles (January 1924, pages 1-2, and February 1924, page 59).

The theme was also taken up in a spoof article ‘Spielmann 46 Jahre alt!!’ on pages 35-37 of the February 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung:

A related matter is the term, ostensibly coined by Tartakower, ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’ to describe Spielmann. As shown below, the nickname appeared in J. du Mont’s obituary of Spielmann on page 10 of the January 1943 BCM, but how far back can it be traced?

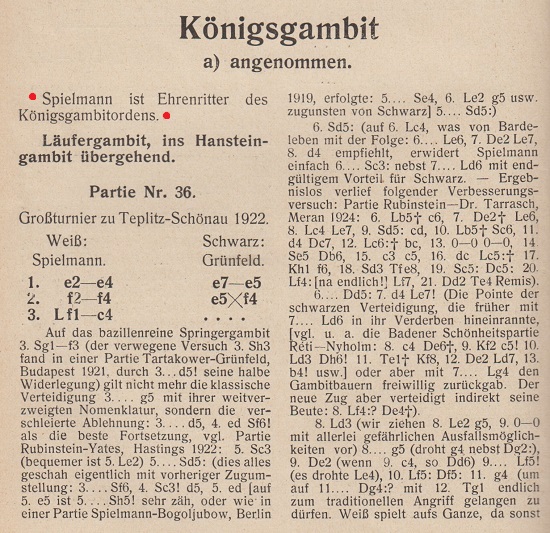

The heading in the King’s Gambit section on page 212 of Tartakower’s Die hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924) had ‘Spielmann ist Ehrenritter des Königsgambitordens’ (‘Spielmann is an honorary knight of the King’s Gambit Order’):

The introduction to a game on page 296 of book one of 500 Master Games of Chess by Tartakower and du Mont (London, 1952) referred to ‘the Knight of the King’s Gambit’:

The word ‘last’ is absent.

This leads to the question of whether it is really a coincidence that Réti wrote similarly, but with the word ‘last’, in the section on Spielmann on page 236 of Die Meister des Schachbretts (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930):

‘Spielmann ist der letzte Barde des Gambitspiels und wollte insbesonders das Königsgambit zu neuem Leben erwecken.’

In the English edition, Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933), the translation (page 127) was:

‘Spielmann is the last bard of the Gambit Game, and what he wanted to revive especially was the King’s Gambit.’

Regarding ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’, two tentative conclusions thus seem possible: either Tartakower used that full term in a text which has yet to be traced or the description resulted from a mistake (by du Mont or by an earlier writer) which combined remarks on Spielmann by Tartakower and Réti.

In any case, ‘The Last Knight’ became attached to Spielmann’s name. It was, for example, the title of a chapter about him on pages 60-64 of Strövtåg i schackvärlden by G. Ståhlberg (Skara, 1965):

As is well known, in the late 1920s Spielmann began opening with 1 d4 far more often than previously. From page 85 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933):

The game was Réti’s victory in 31 moves at Trenčianske Teplice, 1928.

In conclusion, though, the following may be noted from page 80 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929), in the section on Spielmann:

(10265)

From page 96 of Réti move by move by Thomas Engqvist (London, 2017):

‘In Masters of the Chess Board, Réti mentions that Spielmann was the last bard of the Gambit Game, who especially wanted to revive the King’s Gambit. Following Spielmann’s successful result at Carlsbad in 1929, where he shared second place with Capablanca and even managed to beat him, he constantly adopted 1 d4. This conversion made his colleagues nickname him not “the last knight of the King’s Gambit” but “the last knight of the Queen’s Gambit”.’

No particulars were offered.

(10348)

Wanted: early sightings of the rule-of-thumb suggestion about the material value of three tempi. Examples from the 1930s:

‘Ebenso kann man einen Bauern gleich drei Tempi schätzen.’ Page 311 of Das Schachspiel (Berlin, 1931). From page 219 of The Game of Chess (London, 1935): ‘A pawn can be valued at three tempi.’

‘Wir wissen, daß in offener Stellung drei Tempi ungefähr einen Bauer ersetzen.’ Page 45 of Richtig Opfern! (Leipzig, 1935). From page 93 of The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (London, 1935): ‘We know that in an open position three tempi are approximately equal to a pawn.’ From page 85 of the Reinfeld/Horowitz revision (New York, 1951) of J. du Mont’s translation: ‘We know that in open positions, three tempi are approximately worth a pawn.’ Although the volume by Reinfeld and Horowitz was an extensive rewrite, it was used in the ‘21st Century Edition’ (Milford, 2015) without any mention of them.

(10751)

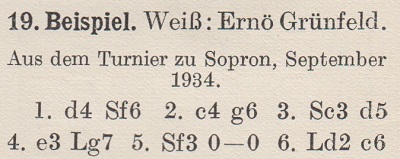

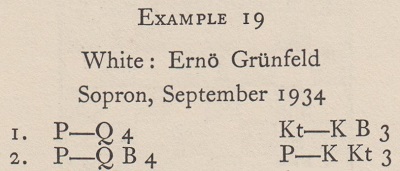

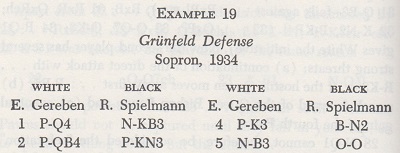

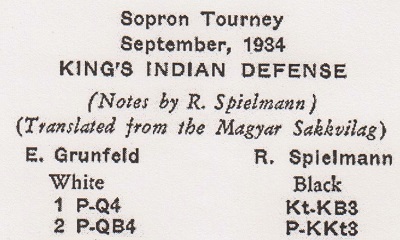

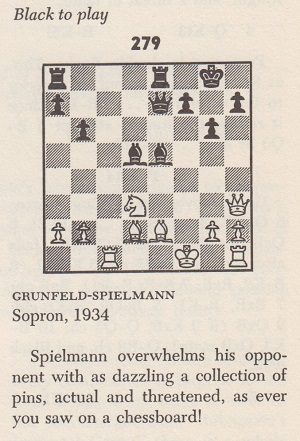

The remark by Spielmann about tempi quoted in C.N. 10751 above came from his annotations to a game which he won at Sopron, 1934:

Original edition of Richtig Opfern! by Spielmann (1935), page 44

Translation by du Mont (1935),

page 91

Extensively revised/rewritten

edition by Reinfeld and Horowitz (1951), page 84

As is well known, Ernő/Ernst Grünfeld of Sopron (1907-88) changed his name to Ernő Gereben, and in the Spielmann game either Grünfeld or Gereben may be used, as long as no impression is given that the player was the E. Grünfeld (1893-1962). That impression was given when the game appeared, with Spielmann’s notes, on pages 224-225 of the December 1934 Chess Review ...

... and when Irving Chernev presented the conclusion on pages 167-168 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960):

In a report on Sopron, 1934 on page 264 of the September 1934 Wiener Schachzeitung the confusion was referred to by Spielmann himself:

‘Der Soproner Meister Ernő Grünfeld hat sich wacker gehalten, darf aber nicht mit dem Wiener Großmeister Ernst Grünfeld verwechselt werden, wie dies einer Wiener Tageszeitung passiert ist.’

The most detailed account of the Grünfeld/Gereben name-change known to us is on pages 11-13 of Ernő Gereben by Gottardo Gottardi (Kecskemét, 1991).

(10752)

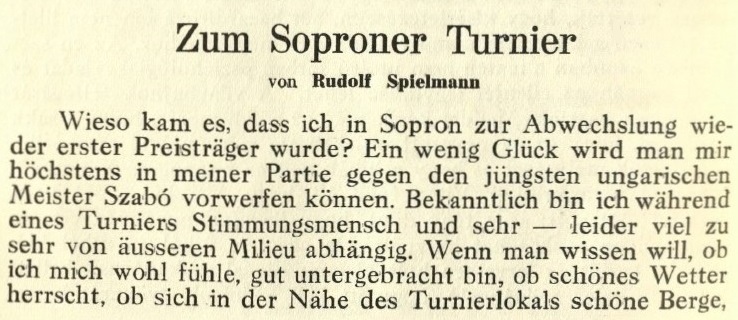

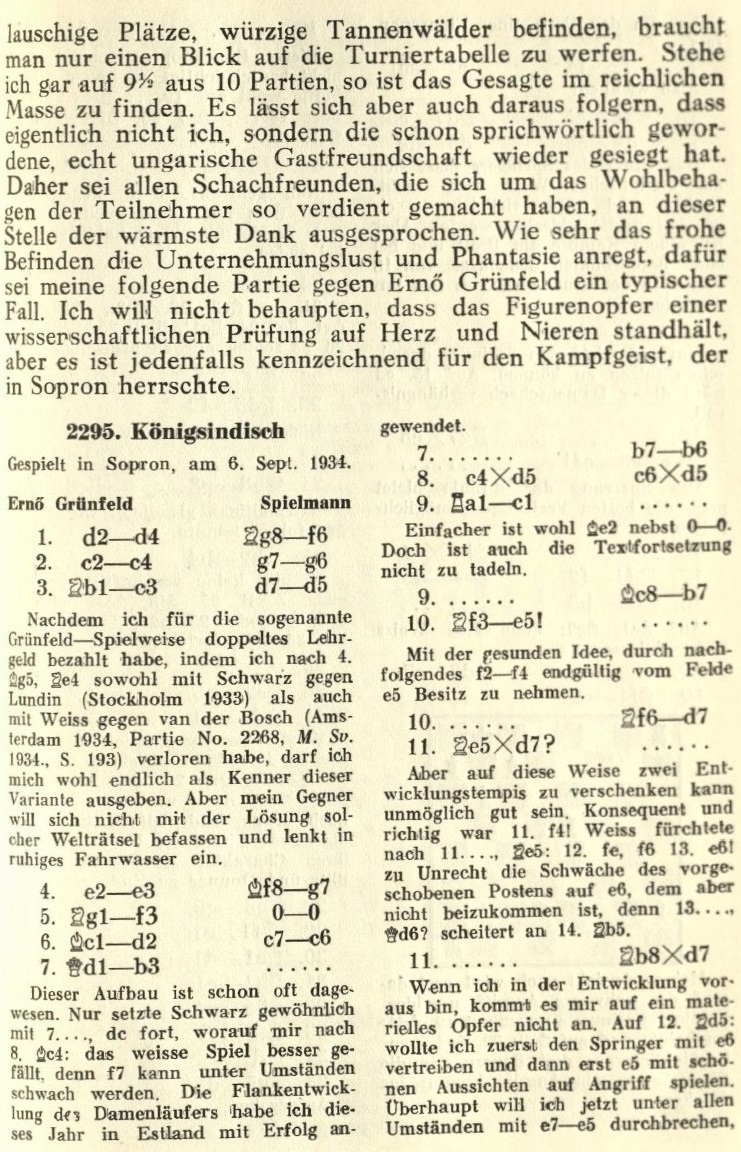

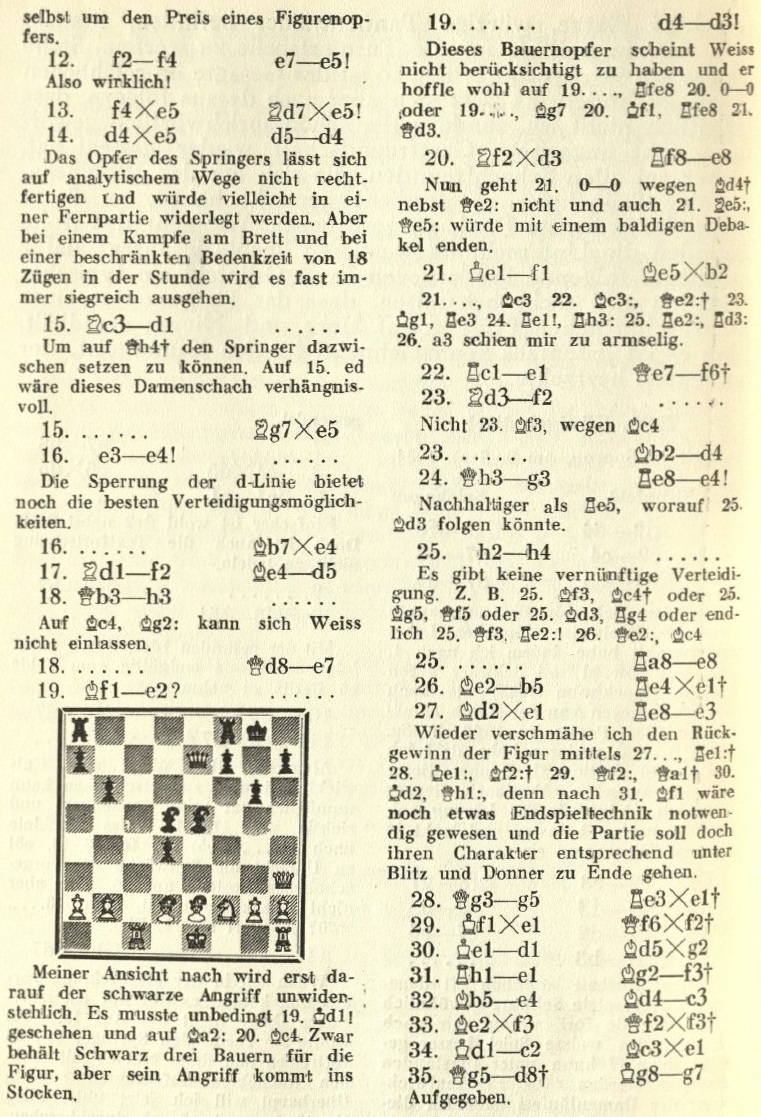

Spielmann’s original text on pages 235-238 of Magyar Sakkvilág, September-October 1934 has been supplied by the Cleveland Public Library:

(10757)

James Lanning (Bloomington, IN, USA) draws attention to this curious passage on page 442 of Die hypermoderne Schachpartie by Savielly Tartakower (Vienna, 1924):

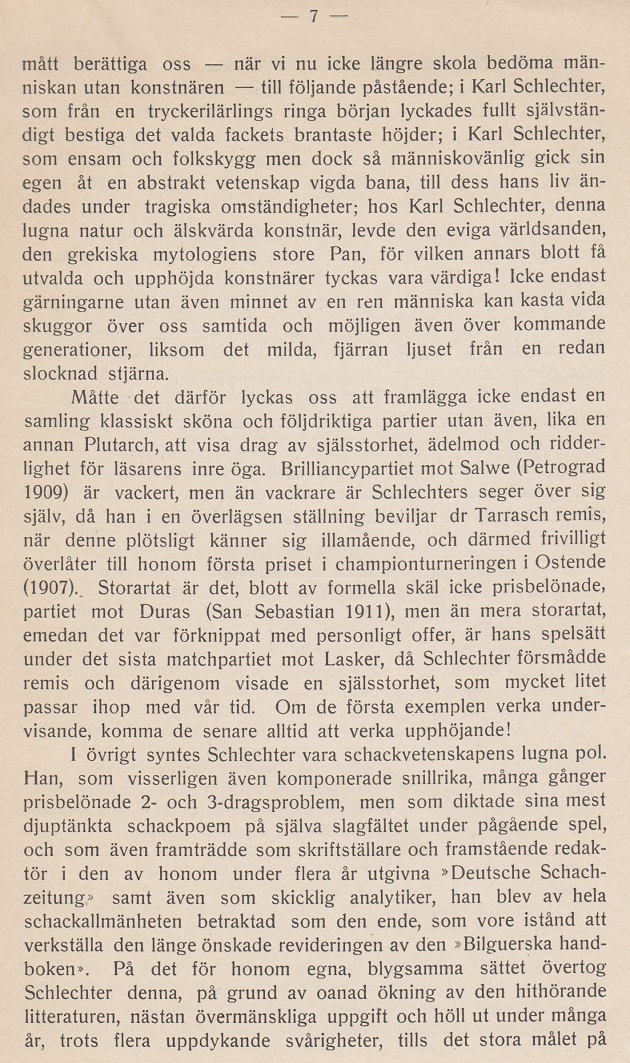

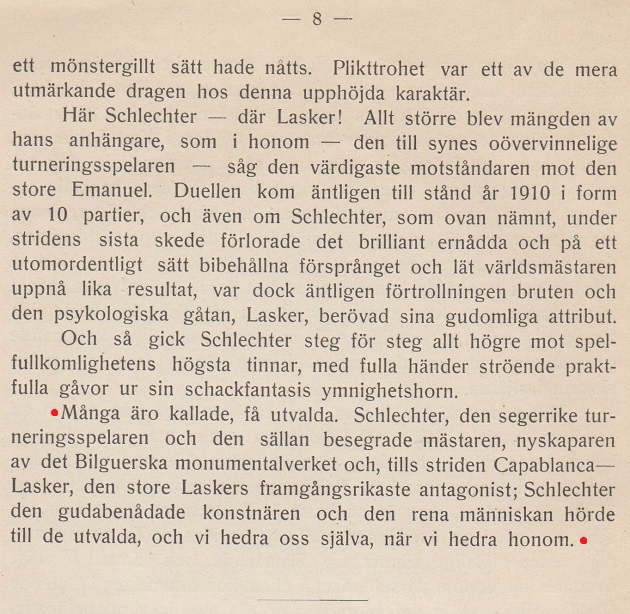

Tartakower’s essay in Spielmann’s monograph on Schlechter is given below in full. It appeared under the pseudonym ‘Spielmann’ in the sense that it was in Spielmann’s book without any indication of authorship, thus leaving readers to assume that the three and a half pages were by Spielmann himself.

The passage in Die hypermoderne Schachpartie mentioned by our correspondent was mistranslated in the disastrous English edition (see C.N.s 9701 and 10408) of Tartakower’s book, The Hypermodern Game of Chess (Milford, 2015):

(10915)

Olimpiu G. Urcan notes that a search for sakk on the Magyar Világhíradók website provides film coverage of Budapest, 1928 ...

(10764)

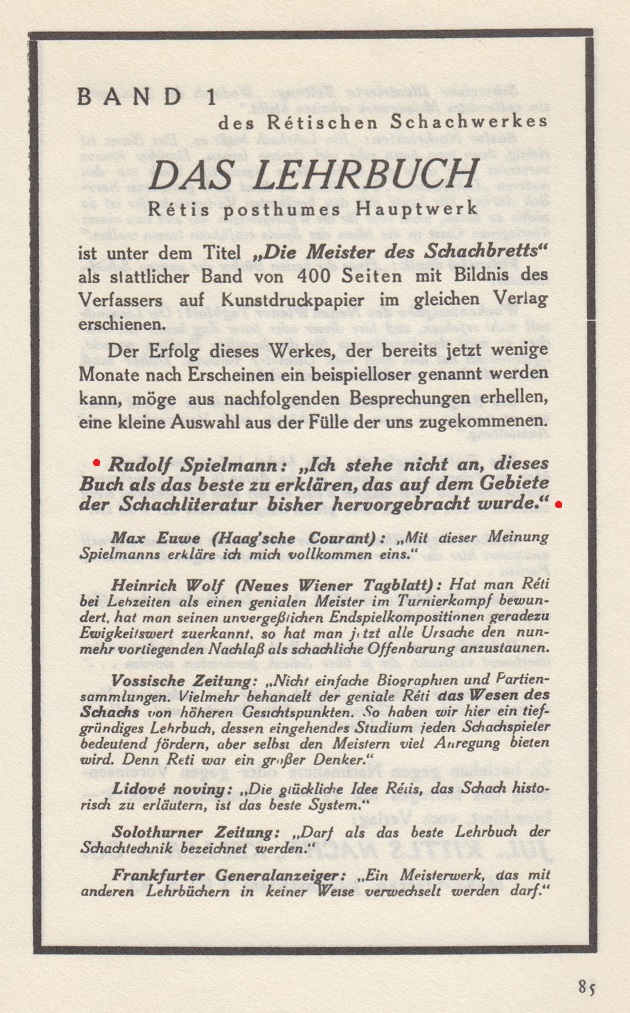

Wanted: further information about Rudolf Spielmann’s assessment of Masters of the Chess Board by Richard Réti.

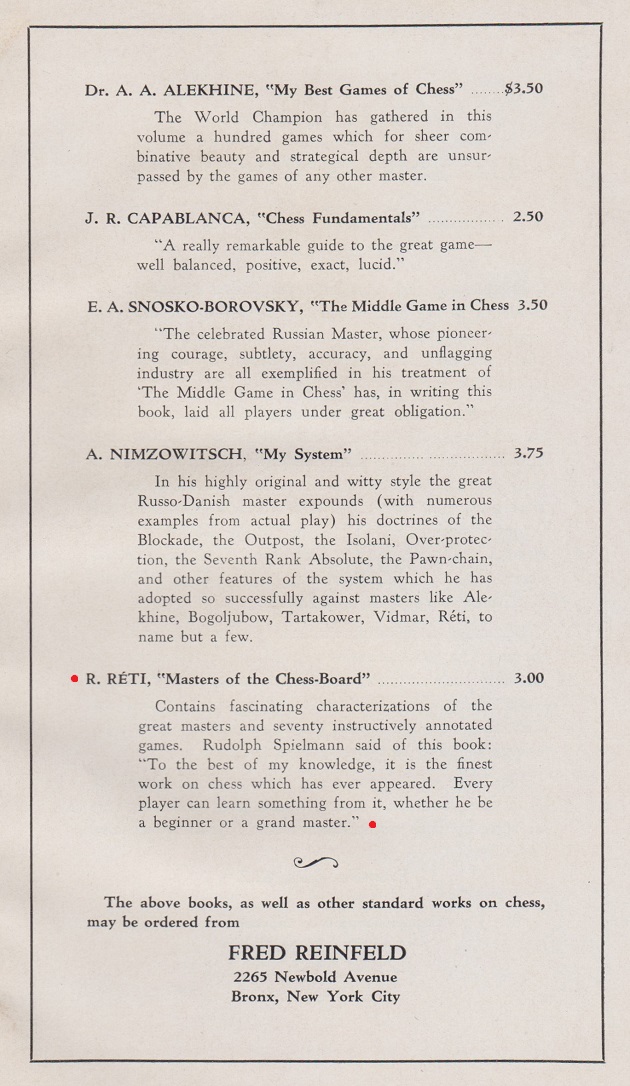

The first of two pages of testimonials in Richard Réti: Sämtliche Studien (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1931), from the same publisher as Die Meister des Schachbretts (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930):

Below is the penultimate (unnumbered) page of Chess Strategy and Tactics by Fred Reinfeld and Irving Chernev (New York, 1933):

(11217)

James Bell Cooper (Vienna) sends a photograph which he took in the Austrian capital on 15 December 2018:

(11138)

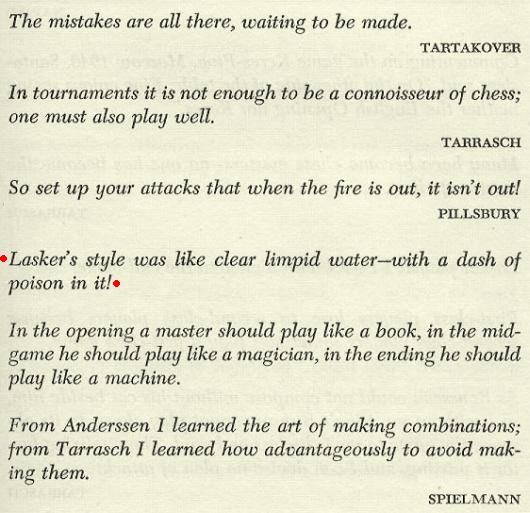

A number of websites continue to ascribe to Spielmann, rather than Mieses, the familiar ‘water and poison’ remark concerning Lasker, so it is worth recalling that C.N. 3161 (see pages 246-247 of Chess Facts and Fables) gave three quotes:

1) From an article by Mieses in the Berliner Tageblatt which was reproduced on page 16 of his San Sebastián, 1911 tournament book:

‘Laskers Stil ist klares Wasser mit einem Tropfen Gift darin, der es opalisieren lässt. Capablancas Stil ist vielleicht noch klarer, aber es fehlt der Tropfen Gift.’

2) The translation on pages xix-xx of the French edition of the book:

‘Le style de Lasker pourrait être comparé à de l’eau claire recevant une goutte de poison qui la rendrait opaline; le style de Capablanca est peut-être encore plus clair, mais il y manque la goutte de poison.’

3) An English version by J. du Mont on page 13 of H. Golombek’s book Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947):

‘Lasker’s style is clear water, but with a drop of poison which is clouding it. Capablanca’s style is perhaps still clearer, but it lacks that drop of poison.’

Chess Facts and Fables explained the misattribution to Spielmann by reproducing page 107 of Irving Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948):

In C.N. 3160 (see also C.N. 4156) we commented:

‘It is evident from other parts of that chapter of Chernev’s that when he gave, for instance, two unattributed quotations followed by an attributed one it was only the last of these that he intended to ascribe to the writer named. Thus in the extract reproduced above the “poison” quote has no more to do with Spielmann than does the “book, magician and machine” comment.’

C.N.s 3741, 4209 and 6714 provide examples of how the lay-out of that chapter of Chernev’s book caused other quotes to be misascribed (to Capablanca and Napier).

(7697)

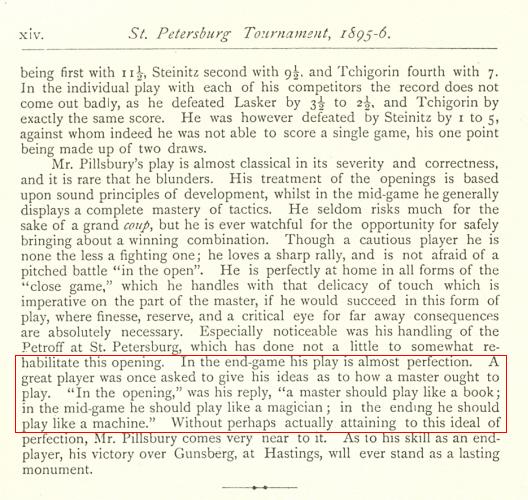

See too Muddled Chess Epigrams and Chess: the Need for Sources. The latter article demonstrates, in particular, that the observation ‘In the opening a master should play like a book; in the mid-game he should play like a magician; in the ending he should play like a machine’ should not be ascribed to Spielmann. From a book published in 1896:

How do such things happen?

(11534)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.