Edward Winter

Which game has seen the most blatant example of a spite check? The following one offers a good start:

Alan Phillips – Stefan Fazekas1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nc6 6 Be3 Qa5 7 Be2 Nf6 8 O-O O-O 9 Nb3 Qc7 10 f4 d6 11 g4 Be6 12 g5 Nd7 13 f5 Bxb3 14 axb3 Nb4 15 Ra4 a5 16 Rxb4 axb4 17 Nd5 Qd8 18 f6 exf6 19 gxf6 Bxf6 20 Rxf6 Nxf6 21 Bb6 Nxd5 22 Bxd8 Nf4 23 Bf6 Rfe8 24 Bf3 Re6 25 Bd4 g5 26 Kf2 Rh6 27 Kg1 Nh3+ 28 Kh1 Rh4 29 Bg4 Nf4 30 Bf5 d5 31 Qg1 h6 32 Bf2 Rh5 33 Bg4 Nh3 34 Bxh3 Rxh3 35 Qg4

35…Ra1+ (‘The spite check in its purest form.’ – Harry Golombek.) 36 Kg2 Resigns.

Source: BCM, July 1955, pages 219-220.

We have been reminded of the above tart comment of Golombek’s by its appearance on page 59 of a new book by Alan Phillips, Chess: Sixty Years On with Caissa and Friends (Yorklyn, 2003), but are there even worse/better examples of the spite check?

Although not all reference books agree, we would reserve the term for moves which offer no realistic prospect of success. Thus we would not use it to describe Burn’s 36 Ne7+ in his game against Důras at Breslau, 1912:

On page 48 of Lessons in Chess Strategy (London, 1968) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘Crafty to the end, Burn makes this check before resigning. It is not only a spite check, for Black, flushed with the triumph of his pawn, might have quickly replied 36…Kh8, whereupon comes 37 Nxf7 mate.’

(3182)

Lawrence Humphrey (Torrelles, Spain) mentions the conclusion of Capablanca v Blackburne, St Petersburg, 1914 (30...Rxh3+).

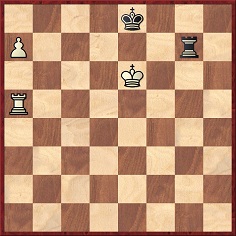

Here is a simple position of our own invention:

Black to move

Instead of resigning, moving his king or making some (other) bishop move (allowing White to mate in one), Black plays the spite check 1...Bb2+.

In our view, candidates for the title of ‘purest’ spite check in actual play need to be of comparable shamelessness.

(3186)

On page 153 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952) Blackburne’s 30...Rxh3+ was called ‘a rancorous check’.

White to move

This position arose at the end of Janowsky v Capablanca, New York, 1916. White played 46 Rxe6+, and on page 217 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965) Irving Chernev wrote:

‘A spite check. Janowsky must realize there isn’t one chance in a million that Capablanca will move 46...K-R4, and allow himself to be mated.’

Chernev wrote similarly on page 96 of his book on Capablanca’s endings.

Naturally the Cuban played 46...Kh7, whereupon Janowsky resigned. Even so, the following appeared at the bottom of page 39 of Bobby Fischer and his Predecessors in the World Chess Championship by Max Euwe (London, 1976):

The mistake was left uncorrected in the US edition, Bobby Fischer – The Greatest? (New York, 1979). The Dutch version of the book, Fischer en zijn voorgangers (Baarn, 1975), was also wrong. From page 72:

(6866)

The remainder of C.N. 6866 discussed bibliographical details concerning the the Euwe book.

We do not regard 46 Rxe6+ as a spite check, because there was a

possibility, however slight, that it would provoke the wrong king

move.

For a discussion of the earliest known occurrences of the term ‘spite check’ (as well as ‘spite sacrifice’) see C.N.s 6966 and 6967.

João Pedro S. Mendonça Correia (Lisbon) draws attention to this annotation on page 217 of the Caissa Editions translation (Yorklyn, 1993) of Tarrasch’s book on St Petersburg, 1914 and wonders whether any personal acrimony underlies the reference to billiards:

From the original German edition (page 151):

The game was Capablanca v Marshall in round four of the final section: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 Qe2 Qe7 6 d3 Nf6 7 Bg5 Be6 8 Nc3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 d4 Be7 11 Qb5+ Nd7 12 Bd3 g5 13 h3 O-O 14 Qxb7 Rab8 15 Qe4 Qg7 16 b3 c5 17 O-O cxd4 18 Nd5 Bd8 19 Bc4 Nc5 20 Qxd4 Qxd4 21 Nxd4 Bxd5 22 Bxd5 Bf6 23 Rad1 Bxd4 24 Rxd4 Kg7 25 Bc4 Rb6 26 Re1 Kf6 27 f4 Ne6 28 fxg5+ hxg5 29 Rf1+ Ke7 30 Rg4 Rg8 31 Rf5 Rc6 32 h4 Rgc8 33 hxg5 Rc5 34 Bxe6 fxe6 35 Rxc5 Rxc5 36 g6 Kf8 37 Rc4 Ra5 38 a4 Kg7 39 Rc6 Rd5 40 Rc7+ Kxg6 41 Rxa7 Rd1+ 42 Kh2 d5 43 a5 Rc1 44 Rc7 Ra1 45 b4 Ra4 46 c3 d4 47 Rc6 dxc3 48 Rxc3 Rxb4 49 Ra3 Rb7 50 a6 Ra7 51 Ra5 Kf6 52 g4 Ke7 53 Kg3 Kd6 54 Kf4 Kc7 55 Ke5 Kd7 56 g5 Ke7 57 g6 Kf8 58 Kxe6 Ke8 59 g7 Rxg7 60 a7 Rg6+ 61 Kf5 Resigns.

Tarrasch also criticized 46 c3, appending a question mark.

Below is the position after White’s penultimate move, 60 a7:

Tarrasch called Marshall’s 60...Rg6+ a Racheschach. It is not a ‘spite check’ strictu sensu, given that two of the three possible king moves by White lose.

(11997)

Various writers offer various definitions, but we should like to know of any (close) equivalents in other languages. Spanish, for instance, has jaque por despecho.

(12008)

See too The Chesswriting Practices of Christian Hesse.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.