Edward Winter

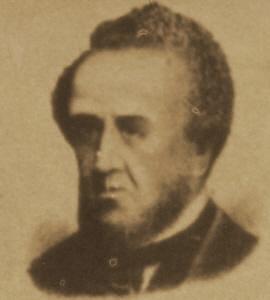

Howard Staunton

On 30 September 1848 the Morning Post published a letter from Thomas Beeby to Captain Kennedy which concluded with a memorable effusion of sarcasm. Beeby offered to put up the funds for a match of 25 games between Kennedy and Lowe …

‘… such games to be published without note or comment, but upon the express understanding that, whatever may be the result, we hear nothing of indigestion, headache, indisposition, want of preparation, rust, or any other excuse, however ingenious, as palliative of defeat.’

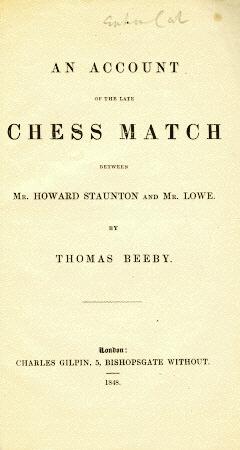

Source: An Account of the Late Chess Match Between Mr Howard Staunton and Mr Lowe by T. Beeby (London, 1848), pages 5-10.

However, Beeby’s 28-page booklet reserved the sharpest barbs for Staunton:

‘Now, truly, this self-glorification is very ridiculous – you beat Mr Mongrédien and the other gentleman named, and straightway bedaub them with the most offensive flattery – the act however is insidious; the majority of those gentlemen are men of a high order of intellect, and by no means weak enough to be duped – they perceive the snake’s eyes glistening beneath the grass, and see that by your efforts to elevate them, your real object is to inflate yourself.

The fact is, no sane man places the slightest reliance on what falls from you, as a matter of opinion, because the man so eaten up by self-conceit, whose notions of himself are so exaggerated, cannot be a safe guide as to the capacity of others.’

Ibid., page 16.

Elsewhere (page 18), Beeby referred scornfully to Staunton’s ‘hebdomodal pop-guns’ and on that same page used a phrase which shows how much the English language has changed in the past century and a half: ‘a luckless wight yclept Turner’.

(K 1999)

Regarding the last sentence above, we added this footnote on page 384 of A Chess Omnibus:

We nonetheless note that the word yclept appeared on page 8 of the January 1930 American Chess Bulletin: ‘In the chapter yclept “the heroical defence”.’

Now an excerpt from page 14 of A Review of “The Chess Tournament,” by H. Staunton, Esq., a very scarce polemical work written by ‘A member of the London Chess Club’ (London, 1852):

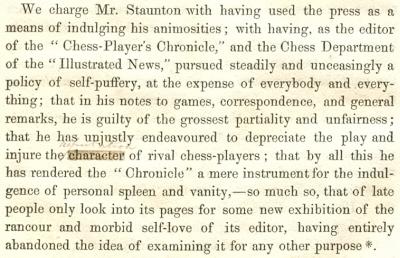

‘We charge Mr Staunton with having used the press as a means of indulging his animosities; with having, as the editor of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, and the Chess Department of the Illustrated News, pursued steadily and unceasingly a policy of self-puffery, at the expense of everybody and everything; that in his notes to games, correspondence, and general remarks, he is guilty of the grossest partiality and unfairness; that he has unjustly endeavoured to depreciate the play and injure the character of rival chess-players; that by all this he has rendered the Chronicle a mere instrument for the indulgence of personal spleen and vanity, – so much so, that of late people only look into its pages for some new exhibition of the rancour and morbid self-love of its editor, having entirely abandoned the idea of examining it for any other purpose.’

The next passage appeared on pages 15-16:

‘From the commencement of the Chronicle, in 1841, we find Mr Staunton constantly excusing his defeats, never attributing the loss of a game to the skill of his antagonist, but only to his own “want of care and attention”, to “severe indisposition”, or, as a last resource, to the “intolerable tedium” of his opponent. We give a few extracts at random; the volumes abound with them. He is losing of course. “This game is given up by a supineness perfectly incomprehensible.” “Lost after having obtained advantages sufficient to decide the game at any time in his favour.” “This game is not very creditable to the skill of either party.” “The play on both sides is incredibly weak.” “This game would be discreditable to third-rate players at a coffee-house.” When he makes bad moves (that his opponent takes advantage of), “they can only be attributed to culpable inattention, arising from over confidence or want of interest in the struggle”; or “they are made mechanically, being utterly indifferent as to the result”. When his adversary extricates himself by a dexterous move from an embarrassing position, it is said to be “a lucky resource”. He comes at last and pleads “sheer exhaustion”, and no doubt has arrived at his ultimatum. What new excuse will be fabricated in the event of his sustaining fresh defeats, it is impossible to conjecture. We would advise him to take the matter into due consideration, as, from recent symptoms of “exhaustion”, there is every probability that his ingenuity in palliating or accounting for defeat will frequently have to be called into exercise.

A very different style, however, is adopted when Mr Staunton proves the victor. He says “he is at length roused into action”. “The game is opened with remarkable care and prudence on both sides.” It is said “to be remarkable also for the varied and interesting positions it assumes”. He is ever feeling temptations “to represent positions of such unusual interest upon diagrams”. “Their consideration will amply repay the student.” He makes moves “that require the nicest calculation”. What was, in the case of his opponent, “a lucky resource” becomes in his “a coup de ressource, which White was evidently quite unprepared for”. Having won a match of Mr Horwitz, he states that it must be highly gratifying to the chess community to be introduced to “so accomplished a master”. No one will deny the skill of Mr Horwitz, but the modest inference Mr Staunton leaves to be drawn from his own words must scarcely fail in raising a smile.’

(2800)

Howard Staunton

A further extract (pages 16-19) from the booklet, and further execration of Staunton:

‘But these ebullitions of vanity are harmless when compared with others that he has penned at various times. His career as a professional chessplayer had, up to the year 1847, been a successful one, and therefore no occasion had up to that time arisen to call forth any very special marks of unfairness, inasmuch as a victor can afford to concede many things to a vanquished enemy. Towards the end of that year, however, Mr Staunton and Mr Lowe were engaged by Mr Ries, the proprietor of the Grand Divan in London, to play a match in celebration of the reopening of that chess saloon. Mr Staunton gave Mr Lowe the odds of the pawn and two moves, and lost the match – he was fairly beaten, and it was evident he could not afford to give the odds to Mr Lowe. No one would have thought the worse of Mr Staunton’s play because he had lost to Mr Lowe, giving such odds as “the pawn and two moves”; but from the moment of his losing the match he seems to have been afflicted with a monomania that the existence of his reputation as a chessplayer depended upon the utter annihilation of that of Mr Lowe! […] Before this match, Mr Staunton speaks of Mr Lowe as “long and favourably known to the frequenters of the Divan as a player of unquestionable talent”, and the Divan is stated to be the resort of the most eminent metropolitan players. After the match, both player and place are condemned together. In a note to a game, he says that the play “never rises beyond the dull level of Divan mediocrity”. We leave our readers to form their own opinion of the consistency of these remarks. An unceasing torrent of abuse filled for months the chess columns of the Illustrated News and the Chess Chronicle – all was poured upon the head of the devoted Lowe. We would here take the opportunity of drawing the attention of the reader to a little pamphlet by Mr Thomas Beeby (Gilpin, 6, Bishopsgate Street Without, 1848), which gives an account of this match, and in which the conduct of Mr Staunton in the affair is severely handled, and with such telling effect that Mr Staunton has never dared to venture a word in reply. Mr Lowe, however, has not been the only victim of Mr Staunton’s hostility. Mr Williams has lately been the object of his vituperation, and for the same reason – Mr Staunton was defeated by him – “Hinc illae lachrymae”. Nothing can be more true than a remark Mr Beeby makes. “To be continually praised by Mr Staunton is a proclamation of having been beaten by him, while to be the object of his attacks is a proof of having beaten him.” The sting of defeat was infinitely more mortifying in Mr Williams’ case than in Mr Lowe’s. In the latter, Mr Staunton could shelter himself to some extent behind the fact of having rendered odds to his opponent; but in the former, the fact of having been beaten even, by a player whom he had long affected to despise, could not be disguised by any ingenuity. A reference to the book under review will show the miserable subterfuges to which Mr Staunton resorts, to palliate his defeat in the Tournament by Mr Williams. The gravamen of the charges against Mr Williams is that “he practised a systematic delay over every move, and that he thereby so irritated his antagonist that he was compelled often to surrender games out of pure fatigue”. Was ever such a plea for defeat as this before offered in games of such consequence to the players as the Tournament games were? The excuse may be readily accepted in the case of games played merely for the purpose of recreation, but it becomes preposterous when urged as it has been by Mr Staunton. Moreover, had the charge been perfectly true, – had Mr Staunton, as he states, been compelled to surrender games out of pure fatigue, which Mr Williams utterly denies, – he would only have been beaten with weapons introduced by himself, and which he has long had the reputation of being an adept in using. His physical endurance in long matches has ever been a subject of remark among players, and conjectures have been hazarded that he owes many a victory to that useful quality. We may here remark that Mr Williams is now playing at the London Chess Club a most interesting and well-contested match, with Mr Horwitz. Sixteen games have been played, and of these the average duration has not exceeded three hours. We must make one or two more remarks upon the inordinate vanity and self-conceit of Mr Staunton. How he, with the commonest perception of what is decent or becoming in society, or with the smallest possible grain of modesty in his composition, can suffer things to be printed in his own magazine that he does, has long been the astonishment of the sober-minded portion of the chess world.’

(2812)

From Mario Ziegler (Nonnweiler, Germany):

‘Shortly after Staunton brought out his London, 1851 tournament book a German translation was published in Berlin: Das Schach-Turnier zu London im Jahre 1851 (“Nach Staunton’s Chess Tournament”). Given that the anonymous author sometimes advances a different view from Staunton’s, it would be interesting to know his identity.

Also, is it possible to name the anonymous author of the pamphlet A Review of “The Chess Tournament”, by H. Staunton, Esq., by a member of the London Chess Club (London, 1852)?’

Extracts from the latter work, a 26-page pamphlet, have been given in our feature article (see above). Our copy of the pamphlet has three markings. In the term ‘wilful misrepresentation’ on pages 9 and 12 the adjective has been deleted, although it remains fully legible. On page 14 the word ‘character’ has been similarly deleted, replaced by hand with ‘reputation’.

The copy of the pamphlet available at Google Books has the same textual amendment, although handled in such a way that ‘character’ is no longer visible.

(6690)

From page 149 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘Staunton was pompous and bombastic, a self-appointed dictator of the chess world. On one occasion a rival published a statement that he had won the majority of his games with Staunton. The next time they met Staunton thundered, “You can’t print that!” His rival stammered feebly that the statement was true. “What’s that got to do with it? Of course it’s true!”, Staunton raged. “But you still can’t print it!”’

(4030)

See Falkbeer, Staunton and Löwenthal.

Below is an article by G.H. Diggle, the Badmaster, from page 90 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It was originally published in the January 1983 issue of Newsflash.

‘The bellicose BM, who keeps a collection of chess disputes in letters, articles and pamphlets going back over 150 years, has duly added to his catalogue the correspondence in December Newsflash in which two most eminent lady players cross swords in fair fight and with due regard to the rules of honourable controversy. But alas! compared with the fights of Victorian days, “what a falling off was there!”

In 1848 Staunton, whose match career since 1843 had been an unbroken success both on level terms and at odds, finally lost a match at “pawn and two” to the least likely player imaginable – namely, Edward Löwe, a perfunctory old Divan player considered to be a very soft touch, as he seldom attacked or made a combination but “just pottered along without having the road up at every step”. The defeated Staunton rose to the occasion magnificently – “You see, sir”, he told a friend, “the odds were not large enough – I could not play my best. I ought to have given him a Knight!” But a fiery anti-Stauntonian, Thomas Beeby of Dyers Hall College, wrote triumphantly to the Morning Post, “The result has proved that Mr Staunton, though never in better play, and having won at the same odds against Mr Harrwitz, Captain Kennedy and other celebrated players, has on the present occasion been over-matched”. At this the high-spirited Captain Kennedy, annoyed at the inference that Löwe was stronger than himself, sprang to the defence of Staunton’s reputation (and his own): “I believe it to be a pleasant delusion (mentis gratissimus error) on the part of Mr Löwe and his friends that Mr Staunton is unable to yield him the odds of pawn and two. It was commonly remarked amongst those who witnessed the match that Mr S. played loosely and considerably below his ordinary pitch, being somewhat rusty for lack of practice. Had Mr S. fought the match in the same trenchant fashion as he did in his former engagements with Mr Harrwitz and myself, I make bold to asseverate that Mr Löwe would have been routed horse, foot, and artillery ... ”

Beeby replied with an enormous letter which wound up by “offering Mr Löwe an engagement at his (Beeby’s) own expense to play Captain Kennedy a match of 25 games the games to be published without note or comment, but on the express understanding that whatever the result, we hear nothing of indigestion, indisposition, headache, want of preparation, rustiness, or any other excuse, however ingenious, as palliative of defeat!” Captain Kennedy affected to regard the last paragraph as an imputation on his temperance and refused to correspond further with Beeby, but agreed to play the match and handed over all negotiations to Mr Turner, the Secretary of the Brighton Chess Club, a high-handed gentleman who (after some heated exchanges with Beeby) followed the Captain by “breaking off all relations”: “I am more than sorry – I am ashamed – that I ever addressed you at all. I desire that you will not write to me again on this or any other subject, as it is not my intention to hold any further communication with you.” Beeby then let himself go in a searing pamphlet: “To reason with such a man as Turner, is like stabbing at water, like cudgeling a woolsack ... I nevertheless endeavoured to dwarf myself to the measure of his capacity by writing in such a manner that no-one not worthy of being an inmate in a lunatic asylum could escape my meaning – the attempt, however, failed, Turner was impervious to reason.” Amazing to relate, the Match did later come off, Löwe winning 7-6-1.’

(5861)

On page 394 of the December 1947 BCM R.N. Coles discussed an odds match, played a century previously, in which Staunton was defeated by Edward Lowe (or Löwe):

‘A pamphlet on the match appeared, making out that Staunton was most disconcerted by his defeat. The author was one “T. Beeby”, a typical pseudonym of the time for somebody whose initials were T.B.B., but whom I have been unable to identify.’

In a letter published on pages 66-67 of the February 1948 BCM G.H. Diggle wrote:

‘I have J.W. Rimington Wilson’s old copy of the pamphlet to which Mr Coles refers in this month’s number. “The Late Celebrated Chess Match between Mr Howard Staunton and Mr Lowe” (published by Charles Gilpin, 5 Bishopsgate Without – price one shilling) was not, as Mr Coles surmises, a pseudonymous effort. The author, Thomas Beeby of Dyers Hall College, Dowgate Hill, was one of the most irate men who ever embarked even on the sea of chess controversy; but though certainly a “vessel of wrath”, he flew his own colours. Nor can his pamphlet (though blistered with italics from head to foot) be called (as Mr Goulding Brown justly calls a later attack on Staunton by F. Edge) “a contemptible publication”. Beeby’s style is robust but not pettifogging. His complaint against Staunton was that he had been “agreeably excited” by reading the announcement of the match in the January number of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, that he had purchased the February number in anticipation of “a continuation of the agreeable excitement”, but found that the last two games of the match had been left out ...’

J.W. Rimington Wilson’s copy of the pamphlet, referred to above, is now in our collection, and is referred to in our ‘Attacks on Howard Staunton’ article. Although ‘An Account of the Late Chess Match Between Mr Howard Staunton and Mr Lowe’ appeared on the title page, the front cover had ‘An Account of the Late Celebrated Chess Match Between Mr Howard Staunton, (Editor of the Chess Player’s Chronicle), and Mr Lowe; with Notes Critical and Explanatory, (By an eminent Chess Player) by Thomas Beeby’.

See also Diggle’s account of the controversy in C.N. 5861 (above). We should like further information about Beeby.

Regarding Edge’s book on Morphy, the description ‘contemptible publication’ originated with Staunton and was endorsed by Goulding Brown. Exact sources for the two occurrences are given in Edge, Morphy and Staunton.

(6870)

Steinitz wrote at length about Staunton on pages 210-213 of the July 1888 International Chess Magazine. Below is a digest of salient quotes:

‘… this very Mr Staunton had made himself notorious as the literary persecutor of Harrwitz, Löwenthal and Anderssen, whom he assailed with personal hostilities in his various writings including actually the annotations of games.’

After writing that Staunton had ‘tortured poor Morphy’ over the possibility of a match between them, and in particular Staunton’s suppression of a key paragraph in a Morphy letter, Steinitz referred to ‘my having received similar treatment at the hands of this Mr Staunton’.

‘This Mr Staunton was one of my first opponents in the Literary Steinitz Gambit and an editorial patient whom I had to cure … from his journalistic delusions …’

‘At that very time this Mr Staunton was again the almighty ruler of public opinion in the chess world and his performance against Morphy was remembered only by very few. In his usual manner he commenced attacking my play; a mode of warfare which, I can assure you, always left me indifferent. But finding that this did not draw sufficiently, he made during my match with Bird an assault on my private character by means of what I may call at least a combination of suppressio veri and suggestio falsi …’

‘… judging from the effect which the first shots from these journalistic batteries had on myself, I have always suspected, that Morphy’s subsequent apathy and hatred for chess, which was, I believe, not alone the first symptom but also the cause of decay of his powerful genius, must have originated from the treatment which he received from that Mr Staunton …’

Regarding his own grievance (the ‘falsifications in the Illustrated London News’) Steinitz contacted Staunton both publicly and privately:

‘My move turned out a very good one, I can assure you, for its first effect was that this very Mr Staunton, who had the audacity of mutilating one of Morphy’s letters and of refusing to publish the letter’s correction of false statements until a Right Honorable Lord interfered on his (Morphy’s) appeal; this very Staunton felt compelled to publish my letter in full the very next week, though with an alteration of the date in order to make it appear to some innocent people that I had used the “strong language” before writing the letter ...

The result of the publication of the letter was that though Staunton with his satellites and suckers tried with might and main to expel me [from the Westminster Chess Club], as I had of course anticipated, he soon discovered that he would not find the usual two-third quorum for such a purpose.

... This is my analysis of my first Club fight or contempt without silence gambit, which was a victory for me … Proof of my statement is that with the exception of two or three growling articles … I enjoyed complete literary peace for the rest of his life, about seven years long, from this very Mr Staunton, who had always fancied that he could aggrandize himself by assailing his rivals with the grossest falsehoods.’

(K 1999)

A footnote on page 384 of A Chess Omnibus:

A remark in the 1851 Chess Player’s Chronicle (page 264) about the ninth game in that year’s match between Anderssen and Löwenthal may be noted here:

‘In this game, which is quite below the mark of both players, there is scarcely a move or position of interest from the beginning to the end.’

Howard Staunton

See too the letter from Steinitz to E.B. Cook, 17 June 1885, on pages 76-77 of The Steinitz Papers by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 2002). For example:

‘... Staunton was most unscrupulous and those who followed him were even worse.’

Below are some observations that we presented in our feature article Edge, Morphy and Staunton:

An historian who worked hard to rehabilitate Staunton up to and including the 1970s was R.N. Coles (1907-82). Howard Staunton, the English World Chess Champion by R.D. Keene and R.N. Coles (St Leonards on Sea, 1975) had the following remark on page 21:

‘Morphy’s ardent but polemical supporter, F.M. Edge, a reporter for the American Herald, published his version of the letters between the two men [Staunton and Morphy] in a form most damaging to Staunton and one which is by no means devoid of bias. The great majority of American chess writers since then, with the notable exception of Bobby Fischer, have suffered from what may be termed the Morphy-Edge syndrome.’

Whether Coles’ co-author shared that view is another question. At all events, 1975 was also the year that this appeared on page 174 of Chess Olympiad Nice 1974 by R. Keene and D. Levy:

‘We feel that the actions of the FIDE congress at Nice and those of the President, Dr Euwe, in particular, represent the biggest scandal the chess world has seen since Staunton refused to play a match with Morphy.’

Coles, for his part, reiterated to us in a letter dated 11 March 1978 that Lawson suffered from the Morphy-Edge syndrome, ‘like most American writers on Morphy’s relations with Staunton’. That viewpoint may be contrasted with an observation by Dale Brandreth on page 141 of the July 1985 APCT News Bulletin:

‘… the fact is that the British have always had their “thing” about Morphy. They just can’t seem to accept that Staunton was an unmitigated bastard in his treatment of Morphy because he knew damned well he could never have made any decent showing against him in a match.’

Making a general point about The Companion, Fred Wilson wrote on page 114 of the 1992 American Chess Journal, ‘There appears to be a clear anti-American bias in the book’. The issue of national bias does, unfortunately, require consideration in the Staunton-Morphy affair. In an attempt to achieve balance in our own book World Chess Champions (Oxford, 1981), for the Staunton chapter we picked Coles (England) and, for the Morphy chapter, David Lawson (United States).

It will be noted from the present article that the main criticism of Edge (an Englishman who was undeniably anti-Staunton) has come from his fellow countrymen. On the lack of a match against Morphy, Staunton has, over the years, been berated by writers of many nationalities, but the strongest general attacks on him have undoubtedly come from the United States, particularly from neo-historians of past generations. For example, in the Preface to his book A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces (London, 1950) Fred Reinfeld wrote (page v):

‘There is no Staunton game – it takes too much time to find a game by him which one can enjoy.’

On page 9 of Napier’s Paul Morphy and the Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957) Reinfeld wrote:

‘It may be true, as a noted psychoanalyst has claimed, that Morphy’s life was ruined by Staunton’s contemptuous rebuffs; but while Staunton’s tomes moulder in provincial libraries, Morphy’s masterpieces still continue to delight every generation of chess players.’

That is not to say that divisions have been on strict national lines. Many, though not all, historians have striven for objectivity, and some of the sharpest anti-Staunton barbs have come from England. The chapter devoted to him in Hartston’s The Kings of Chess is entitled ‘The Pompous Years’.

On pages 261-265 of the September 1964 BCM G.H. Diggle wrote ‘The Morphy-Edge Liaison’, and in reply to criticism of his article from Frank Skoff, Diggle commented in C.N. 1012:

‘When I wrote “The Morphy-Edge Liaison” in 1964 I was a “fiery youth” of only 61, a lifelong admirer of Staunton who for four decades had witnessed my hero denigrated in potboiler after potboiler not only as the “cowardly evader of Morphy” but a producer of “devilish bad games”. As I considered that the main source of all this was Edge, I launched forth my “counterblast” in an attempt to redress the balance. If I have now lived to be myself “counterblasted” out of my “wheelchair”, I must accept this as one of the hazards of indiscreet longevity.’

There follow some examples of how Howard Staunton was treated in certain ‘popular’ books.

The chapter on Morphy (pages 233-245) in The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963) has some particularly biting comments on Staunton:

‘England can look back to a long honorable history of gentlemen with unflinching devotion to the principle of fair play. Definitely not to be counted among them is Howard Staunton who somehow – with no convincing record to substantiate it – gained for himself, in his own day, a name of eminence in the chess world.’

‘... one of the most tragic chapters of shame in the history of chess is Staunton’s gross, shabby, arrogant treatment of a highly sensitive young chess genius [Morphy] ...’

‘Staunton initiated his campaign of perfidy in his 24 December 1857 column in the London Illustrated News [sic] ...’

‘In the meantime, the Shakespearean scholar, the man of culture, Howard Staunton, carried on dilatory tactics with a firm resolve, born of a craven soul, never to face alone an inevitable drubbing at the hands of the young American genius.’

‘Surprisingly, the one person of standing who has come to Staunton’s defense is H.J.R. Murray, famed chess historian. In an article in Chess Magazine [sic – it was the BCM], December 1908, Murray justifies Staunton’s stand [regarding the non-match against Morphy] on the ground of his “arduous literary occupations”. It is to be hoped that Murray’s conclusions in his History of Chess are based on more firm ground than in his preposterous apologia in behalf of the unspeakable Howard Staunton.’

‘Yes, this delicate human being [Morphy] was mortally wounded, for in his own mind he had failed to accomplish his purpose, and he was not at all impressed with the overwhelming evidence that Staunton had run away, cravenly, in virtual disgrace.’

As regards the criticism of H.J.R. Murray, the specific term ‘arduous literary occupations’ does not appear in his BCM article. It was used, however, by P.W. Sergeant when referring to Murray’s article on page 18 of Morphy’s Games of Chess (London, 1916):

Whether Horowitz and Rothenberg had read Murray’s article is an open question.

It should hardly be necessary to add that quotation of such anti-Staunton material indicates nothing about our own views. The purpose is merely to make texts available for general consideration,

(6650)

Even in the pre-Internet age, some people required only a few words or lines to give themselves away in terms of unfairness and/or inaccuracy. From page 10 of The Collier Quick and Easy Guide to Chess by Richard Roberts (New York, 1962):

That is the full ‘potted biography’ of Staunton.

(9869)

See too C.N. 10412, as well as The Facts about Larry Evans.

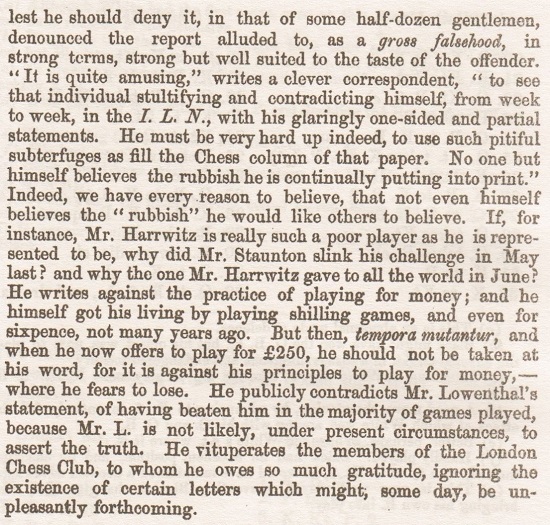

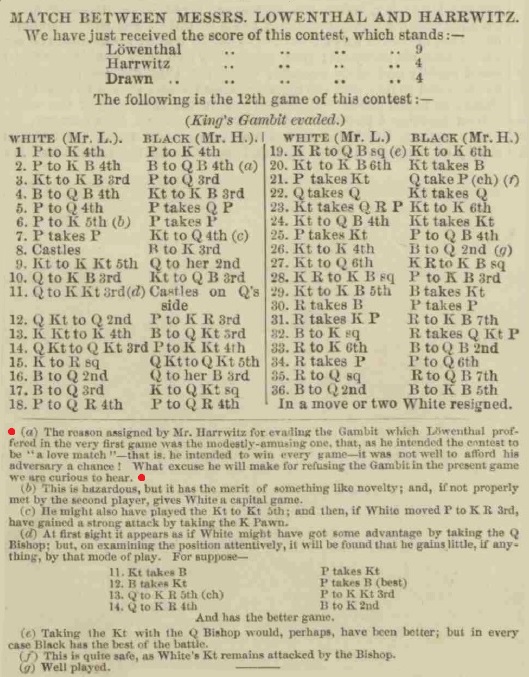

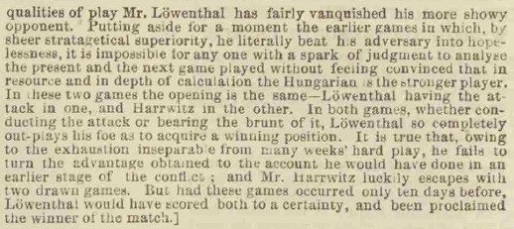

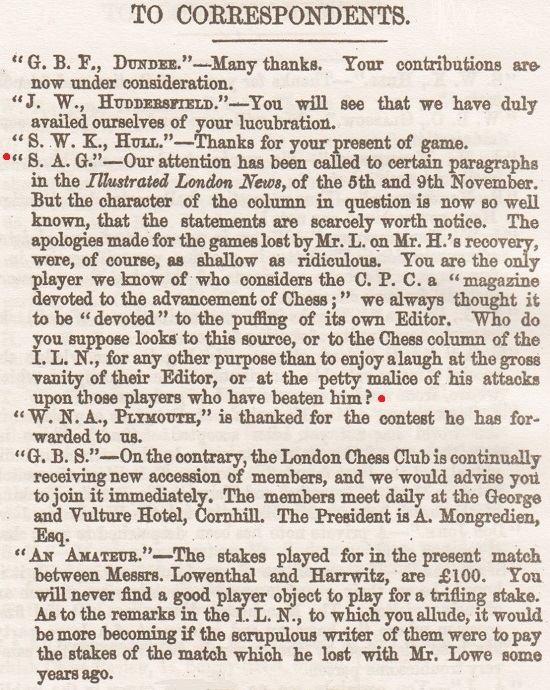

An addition from pages 381-382 of Daniel Harrwitz’s British Chess Review, 1853:

Below is the relevant part of the Illustrated London News column referred to (5 November 1853, page 383):

(11319)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The 1853 British Chess Review article reproduced in C.N. 11319 contains expressions such as “egregious falsehoods”, “ridiculous absurdities” and “rubbish”, all directed at Howard Staunton. One might expect that such truculent language would be accompanied by suitable substantiation, yet in the few examples discussed only a small amount of evidence was proffered, and it looks far from convincing.

Staunton is accused of a “gross falsehood” regarding his remark that Harrwitz intended “a love match” against Löwenthal. However, that Harrwitz did say something similar was later affirmed by Charles Tomlinson, a scientific writer and lecturer whose recollection of the controversy appeared on pages 50-51 of the BCM, February 1891, in an article about Simpson’s Divan:

“Harrwitz was so elated at having won the first two games that he declared in my presence that Löwenthal should not win a single game.”

Later Tomlinson witnessed a confrontation in Spring Gardens when Harrwitz denied the boast, whereupon both Staunton and Tomlinson were silent:

“Staunton simply smiled, and said nothing. Of course I was equally silent, from a reluctance to get into hot water with the Divan party.”

Tomlinson’s account implies that he could have rebutted Harrwitz’s accusation.

The accusation “slink his challenge” is used in connection with the abortive negotiations in 1853 for a Staunton-Harrwitz match, but that seems a biased summary of what took place. In an address to the Northern and Midland Counties Chess Association at its Manchester meeting in 1853 (see the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1854, pages 187-189), Staunton explained at some length his reluctance to accept Harrwitz’s challenge, observing, in particular, that he had previously beaten him in a match and that the opponent whom he was really seeking was Adolf Anderssen. Nevertheless, negotiations did eventually get underway, but later broke down, after which a letter from Edgar Sheppard, Staunton’s second, which was published on page 61 of the Illustrated London News, 21 January 1854 gave the impression that Harrwitz’s side had defaulted and forfeited the £25 deposit “by the articles of agreement”.

Staunton’s attitude towards playing for money appears to have changed with time, and he is criticized for that. Nonetheless, in the case of an important match a worthwhile stake was customary, and it is arguable that he was justified in seeking one for a match with Harrwitz in which he had little to prove, having previously defeated him decisively.

The article supports Löwenthal’s side of the argument over the disputed Staunton v Löwenthal score but, in the absence of any evidence to explain the reasoning, is the comment really worth anything?

The final sentence contains a mysterious threat regarding “the existence of certain letters”, presumably containing some compromising information about Staunton. However, the letters have not so far been “unpleasantly forthcoming”, despite the passage of 166 years. Without them the remark seems no better than tittle-tattle.

The editor of the British Chess Review was Daniel Harrwitz, but was he solely responsible for this article? It is questionable whether someone whose native tongue was not English could have produced the article without help. Tim Harding discussed the involvement of Samuel Standidge Boden with the British Chess Review on pages 130-132 of his book British Chess Literature to 1914 (Jefferson, 2018).’

(11329)

C.N. 11319 showed extracts from Staunton’s Illustrated London News column of 5 November 1853, page 383, concerning the Harrwitz v Löwenthal match. An addition comes from page 427 of the 19 November 1853 issue:

A response to both columns appeared on the cover of the December 1853 edition of Harrwitz’s British Chess Review:

(11433)

‘Staunton showed the effectiveness of the English opening, 1 P-QB4. Actually, his greatest impact on chess history was a negative one: by refusing to go through with a match against Morphy, he presumably effected the latter’s disillusionment and permanent withdrawal from chess.’

Source: page 17 of The Battle of Chess Ideas by Anthony Saidy (London, 1972).

(11425)

From John Townsend:

‘The Satirist, or Censor of the Times was a Sunday paper which specialized in scandal and innuendo. Chess was discussed occasionally, but the material needs to be viewed with great caution.

Page 4 of the 24 December 1843 issue carried the following reply to a correspondent, “Queer Gambit”, who, it is implied, had suspected some kind of skulduggery in the Staunton v Saint-Amant match in Paris:

“Queer Gambit. – Ever since chess became a betting game, it is as little removed from ‘the cross system’, as the race, the ring, the river, or running matches. We believe the contest in the French capital to have been a fair one, notwithstanding what ‘Queer Gambit’ has heard.”

The “cross system” refers to a method of breeding racehorses in which strict pedigree requirements are watered down.

Howard Staunton may have been paying the price of newly-won fame, since, two weeks later, on 7 January 1844, he was featured again, on page 4:

“A correspondent asks us if it is true that the English champion at chess, Mr Staunton, used to be known in certain circles some years back by the jocular soubriquet of ‘the Bird’. Perhaps somebody will satisfy this curious gentleman.”

No follow-up insertions have been found. Enlightenment is sought as to the possible significance of the soubriquet “the Bird”, and what the “certain circles” may have been.

The Editor was Barnard Gregory (1796-1852), who was also the leader of a company of amateur actors called the Shaksperians. According to Frederic Boase’s Modern English Biography (volume 1, pages 1233-1234):

“... he libelled and blackmailed many persons, especially Charles, Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg.”

The Duke played against Paul Morphy in the celebrated consultation game (Paris, 1858). The same source mentions that Gregory was twice imprisoned and that he played Hamlet at Covent Garden on 13 February 1843, “when there was a riot headed by the Duke of Brunswick”.

Gregory also edited The Penny Satirist, 1837-46.’

(11568)

Addition on 10 February 2025:

In C.N. 12105 John Townsend commented on the coverage of the Staunton-Morphy affair in The Real Paul Morphy: His Life and Chess Games by Charles Hertan (Alkmaar, 2024). Below is an extract:

‘... it seems that even-handedness was not part of Mr Hertan’s objectives. He refers to Morphy sometimes as “Paul”, while the supposed villain of the piece has to make do with “Staunton”.

The following anti-Staunton language and sentiment is to be found:

Page 268:

“Paul understandably doubted Staunton’s intentions”

“... sucker punches received from Staunton in the press ...”

“... Morphy shared his concern that Staunton would try to evade the match, and pin the blame on Paul ...”

Page 270:

“... but Staunton being Staunton, he couldn’t resist taking more cheap shots at Morphy in his column ...”

“... his shoddy treatment of the American ...”

Page 271:

“These actions were certainly petty and ungracious on Staunton’s part”

“... the bitchy sniping of a humiliated champion ...”

“... potshots at Morphy ...”

“... rattled by Staunton’s antics ...”

“... his unseemly behavior ...”

Page 272:

“... Staunton’s catty, distasteful behavior ...”

“But Staunton’s defenders never threw in the towel.”

Page 273:

“Howard Staunton had a deeply flawed personality.”

This last remark is perhaps the most damning of these criticisms and is stated with the same certainty as if Mr Hertan had had Staunton on the psychiatrist’s (or psychotherapist’s) couch in his consulting-room. It almost reaches the level of conviction of Dale Brandreth, whom you quoted [from page 141 of the July 1985 APCT News Bulletin; see above]:

“… the fact is that the British have always had their ‘thing’ about Morphy. They just can’t seem to accept that Staunton was an unmitigated bastard in his treatment of Morphy because he knew damned well he could never have made any decent showing against him in a match.”’

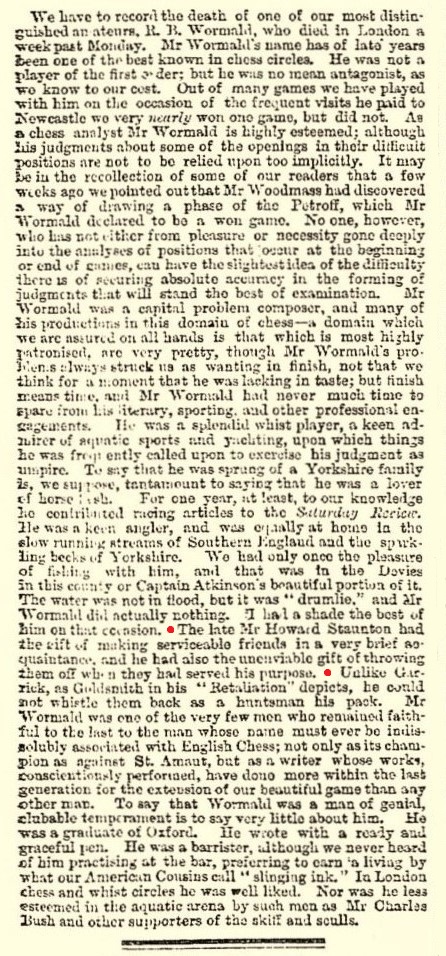

From page 7 of the Newcastle Courant, 15 December 1876 (chess columnist: William Mitcheson):

The marked text reads:

‘The late Mr Howard Staunton had the gift of making serviceable friends in a very brief acquaintance, and he had also the unenviable gift of throwing them off when they had served his purpose.’

Does that claim hold up under scrutiny?

(12117)

From John Townsend:

‘In C.N. 12117, the chess columnist William Mitcheson stated that Howard Staunton “threw off” friendships when they were no longer of service to him. No evidence for his assertion was offered, and no examples were provided.

It cannot be doubted that Staunton made enemies, but the same could be said of other top players who have been world champion or regarded as the world’s best, or who have achieved great fame. The examples of Steinitz and Alekhine spring to mind, while Lasker and Capablanca acquired reputations for making challenges difficult to mount, resulting in tensions. Is there not something special about the position of a champion which provokes envy, rivalry and hostility? They are there to be shot at.

In the case of Staunton, he was, in addition, a forthright man. The art critic Thomas Jefferson Bryan, in comparing him with Saint-Amant, preferred Staunton’s openness and made the following observation:

“Mr Staunton cares not to appear other than he is. I make no pretensions to etiquette, but common sense induces me to prefer his sincerity – and I confess his mode of behaviour is the more pleasing to me – for we cannot accuse him of carrying his politeness to an undue excess.” (Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1846, page 147.)

In a letter to the City of London Chess Magazine (January 1875, pages 12-13), von der Lasa referred to Staunton’s own remarks about his associations with five notable chess figures:

“Staunton’s letter of November last [1873] was altogether written in a most friendly tone, and spoke likewise in affectionate terms of other players. ‘I was sorry’, he wrote, ‘to lose Lewis and St Amant, my dear friends Bolton and Sir F. Madden, and others of whom we have been deprived, but for Jaenisch I entertained a particular affection, and his loss was proportionately painful to me. He was truly an amiable and an upright man.’”

In the case of the problemist Reverend Horatio Bolton, a Norfolk clergyman, he had been a friend since at least 1840, when the two contested a correspondence match, and he was referred to as a friend in a letter as late as 1873, the year of Bolton’s death.

Von der Lasa acknowledged that Staunton was responsible for “animosities” in the world of chess and attributed the cause to “his great irritability of temper”, which resulted from his heart problem.

In the world of Shakespearean studies, Staunton enjoyed a long and rewarding friendship with the scholar James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps. Their correspondence (see C.N. 11993) ended only with Staunton’s death in 1874, having begun in 1855 or earlier. Their exchanges are respectful and nearly always cordial. These qualities are not diminished by the odd blunt remark made by Staunton; neither is their friendship jeopardized by it.

Finally, it is relevant to mention here his wife Frances, to whom he was married for 25 years. The impression left is that their marriage was harmonious, since no evidence is known that during that time the two of them even quarrelled, let alone had a serious rift.’

(12141)

A small photograph of Mitcheson appears in C.N. 3467.

Our article Attacks on Howard Staunton includes chess observations by, among others, Fred Reinfeld, Al Horowitz and Larry Evans. Remarks by Evans are discussed in detail in The Facts about Larry Evans, and here is another one:

Reno Gazette-Journal, 18 April 1987, page 33

(12127)

Note: Material above which we originally presented in Kingpin is indicated by the reference ‘K’, followed by the magazine’s year of publication.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.