Edward Winter

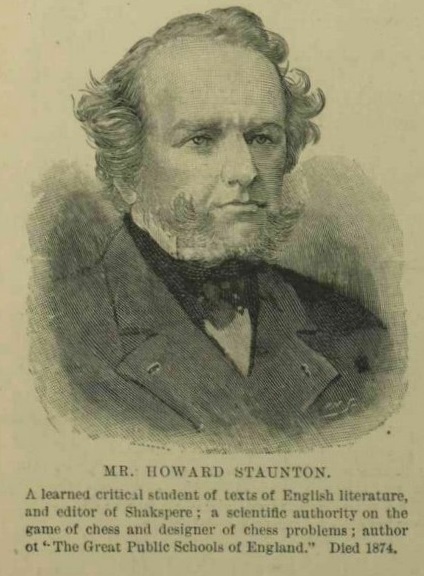

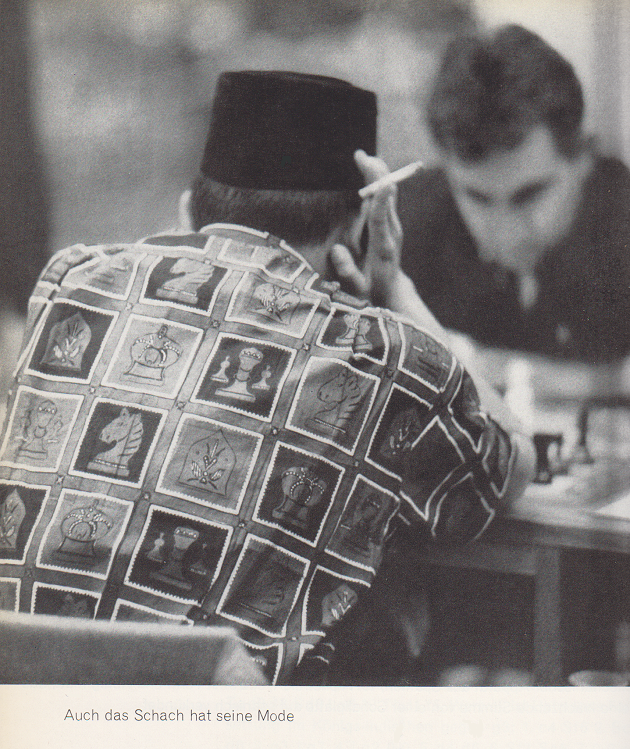

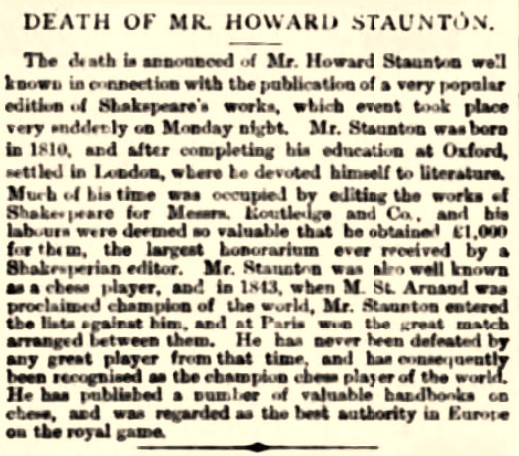

Illustrated London News, 864 May 1892, page 598

The present general article on Howard Staunton does not repeat material in our existing articles on the Staunton v Morphy controversy, or in Attacks on Howard Staunton and Pictures of Howard Staunton.

A quote from George Walker’s pioneering work Chess Studies (London, 1844), page x:

‘In stating that I consider Mr Staunton to be at present the first English player, I sufficiently mark my opinion of the high qualities of his game. Brilliancy of imagination – thirst for invention – judgement of position – eminent view of the board – untiring patience – all are largely his. In Mr Staunton we are proud to recognize a champion worthy to succeed M Donnell. – Can praise go further?’

(7)

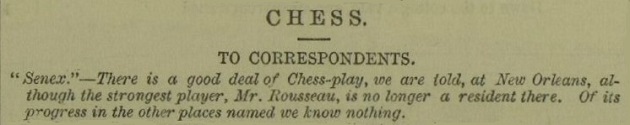

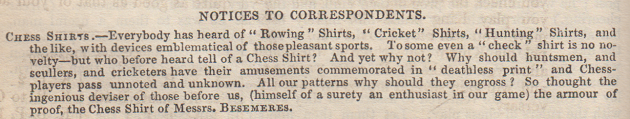

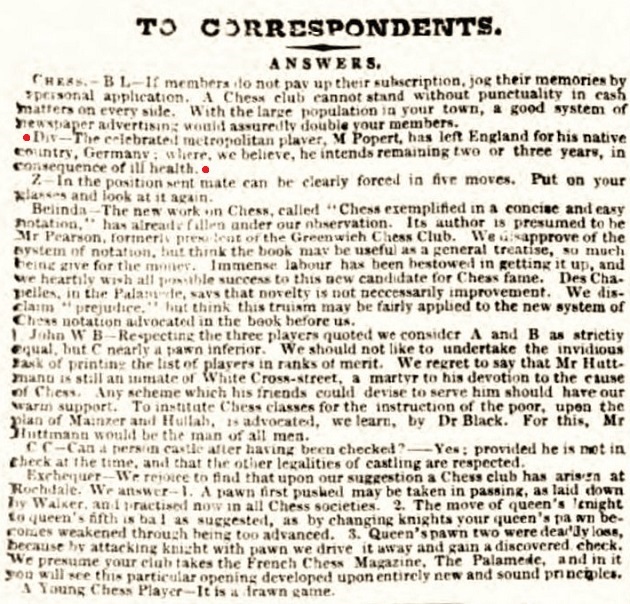

For an entertaining couple of hours or so, read through some of Staunton’s celebrated chess columns in the Illustrated London News. Some of his more ‘abusive’ Answers to Correspondents are quite well known. We give below a couple more:

‘J.K. Manchester. Assuredly Mr Staunton must be as much surprised as you can be by the announcement of a book of chess problems with his name as author, seeing that he has never made a chess problem in his life. The work turns out to be the wretched trick of a dishonest bookseller We should recommend any person who has been duped into buying this volume to proceed against the vender for obtaining money under false pretences.’ (24 January 1857)

What was the volume referred to?

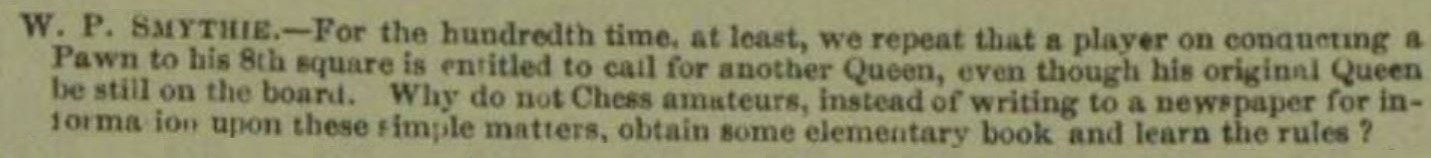

‘For the hundredth time, at least, we repeat that a player on conducting his pawn to the 8th square is entitled to call for another queen even though his original queen is still on the board. Why do not chess amateurs, instead of writing to a newspaper for information on these simple matters, obtain some elementary book and learn the rules?’ (30 May 1857)

(91)

Regarding the 24 January 1857 column, we added this endnote on page 271 of Chess Explorations:

It seems that the only problem book published in 1857 was A Selection from the Problems of the Era Problem Tournament, prefaced by Löwenthal (published by T. Day, London). A German edition, Era-Schachproblem-Turnierbuch, appeared in Leipzig the same year. Any connection with Staunton remains to be established. Despite his use of the word ‘announcement’ it is more likely that Staunton was referring to a work of some five years previously. From page 34 of Betts’ Annotated Bibliography: ‘The Cleveland catalogue also has the following entry under Staunton, Howard: “Chess problems, consisting of upwards of seven hundred games and problems by the most eminent players: being the whole of ‘The Chess Player’s Chronicle’ for the years 1851 & 1852. 2 vols. in one. London, C. Skeat, 1852.”’ Has anybody ever seen a copy?

Why should the silly season not also invade the chess press? On page 90 of the August 1982 CHESS R. Hanna ‘reads your horoscope and names some famous players under their sign of the zodiac’. Some jaundiced souls may have found it hard to get past the first two sentences of the opening star-sign, Aries: ‘ARIES are bright and creative. Their weakness is in the endgame.’ Two typical Aries masters are then quoted: Smyslov and Portisch. We, however, were most grateful to R. Hanna. For no amount of historical research has ever revealed anything about the birth of Howard Staunton apart from the year: 1810. Yet astrology triumphs where historical investigators have failed; R. Hanna is able to reveal exclusively that Staunton was born under Cancer.’

(216)

From page 383 of the first volume of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (1841), a quote from Staunton which is of particular interest in view of his subsequent difficulties with Morphy:

‘Chess is unquestionably the finest game known; but still it is only a game; and one can entertain but a sorry opinion of his intellect, who makes it, or any amusement, the business of his existence.’

(596)

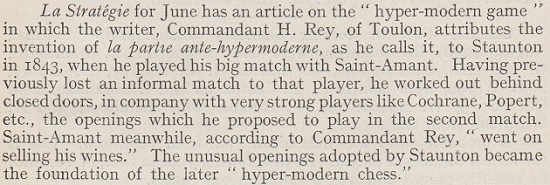

Addition on 28 August 2023:

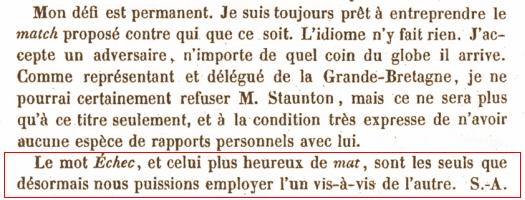

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) quotes the words used by Saint-Amant about Staunton when writing about their first match in May 1843, on pages 203-204 of Le Palamède, 1843:

‘… j’attaque un homme qui, comme Labourdonnais, n’a pas d’autre occupation, d’autre sol à défricher que celui de l’échiquier; qui, de la tête aux pieds, est tout échec; qui y travaillait hier, qui y a rêvé cette nuit, et qui demain, après demain, n’a d’autre spécialité que celle-là. Moi, au contraire, je me partage; des occupations commerciales sont le sérieux de mon temps; les Échecs sont mon plaisir, mes distractions. Dans quelles conditions d’infériorité ne me présentais-je pas au combat!’

Our correspondent comments:

‘You will see that he finds in Staunton characteristics similar to those which had been deplored by Staunton himself some 20 months earlier in C.N. 596. Saint-Amant may have exaggerated a little in order to magnify his achievement in winning the match. I previously used this quotation on page 77 of my book, Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.

Later, Alphonse Delannoy made similar criticisms of Staunton at the time of the Paris match (Le Palamède 1843, pages 543-544), to which George Walker replied, pointing out that “his [Staunton’s] time is equally filled up with business matters as that of St. A.” (Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1845, page 93). However, Walker did not mention what “business matters” he was alluding to; he may have meant his work on the Chess Player’s Chronicle.’

In New in Chess issue 3/1986 the readers’ letters section suddenly comes alive with a series of excellent contributions on the Sphynx problem in Staunton’s Handbook.

(1190)

See also C.N. 12177.

Staunton wrote in the 1849 Chess Player’s Chronicle, page 48 (after 1 d4 e6 2 e4 d5 3 exd5 Qxd5):

‘The only advantage of taking the pawn thus, instead of in the way recommended by common sense, is that being likely to involve you in difficulties, it affords a charming opportunity for the display of ingenuity in extricating yourself afterwards.’

Quoted by D.J.Morgan, BCM, December 1954, pages 387-388.

Opinions are invited on whether Staunton had a sense of humour. Was his lacerating prose sometimes mere drollery?

(1283)

From G.H. Diggle (Hove, England):

‘Staunton’s jibe in the 1849 Chess Player’s Chronicle about the “charming opportunity for the display of ingenuity” was aimed at Edward Lowe, one of whose games against Capt. Kennedy he was annotating. Staunton displayed rather more humour as a raconteur than as a writer. He would solemnly relate absurd stories (never intended to be believed) either about himself or some other master.’

(1305)

From page 209 of the July 1899 BCM (in an obituary of G.A. MacDonnell by J.G.C.):

‘Staunton himself was a talker of repute; his stories were well told, his anecdotes pointed, and his humour flowed freely, albeit the stream might be somewhat turgid, and there was a general air about him which seemed to say, “When I ope’ my lips let no dog bark”.’

From W.D. Rubinstein (Aberystwyth, Wales):

‘Is anything more now known about the ancestry of Howard Staunton than when Keene and Coles’ biography appeared in 1975? According to the account in the Oxford Companion to Chess, “nothing is known for certain about Staunton’s life before 1836”. Have the Westmorland parish registers for the spring of 1810 ever been searched for a record of his birth? If he was not the illegitimate son of the fifth Earl of Carlisle, how did the rumour arise that he was, given that the Earls of Carlisle were not really household names among the English aristocracy? The fifth Earl (1748-1825) would have been 62 when Staunton was born. According to the Dictionary of National Biography he was a playwright of some note and was Chancery guardian to Lord Byron, which might be of relevance, given Staunton’s literary pursuits. There is no mention of Howard Staunton in his will. Could Staunton possibly have been the illegitimate son not of the fifth Earl, but of one of his sons – for instance of his third son Lord Frederick Howard, who was born in 1785 and was killed at Waterloo? Has any research been done with their wills?’

(1453)

From Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘Among the many studies Hooper and I made for the Companion was to examine the Westmorland parish registers for every male child born of a father named William in the period March-September 1810. We also looked at every play-bill where Kean was in The Merchant of Venice and noted the Lorenzos. The secretary of the Earl of Carlisle is certain that Staunton was not of the family, and wills have been examined. I am sure, but cannot prove of course, that his original names were neither Howard nor Staunton. We know that he was, when young, greatly influenced by Kean, and a study of Kean’s life gives clues that show how Staunton might well have selected his name and circulated (in order to deny) the Earl of Carlisle bastard rumours. We took out death certificates for any William or Mary Staunton who died at a time which would fit their having been Howard’s parent, but only one turned out to be of the right sort of age. Birth and death certificates were issued only from 1837 onwards. Hooper made a map showing the place of death of every Staunton who died from the beginning of records in October 1837 up to December 1885. There were 240; none in Westmorland.’

(1471)

From pages 395-396 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘The names of Philidor and La Bourdonnais are destined to an immortality as lasting as the game of Chess itself; and, if the fame of M. Des Chappelles should prove less enduring, it will not be from inferiority of genius, but the misfortune which has preserved for posterity so few of his remarkable achievements.’

Howard Staunton, the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 27 November 1847, page 378.

(7069)

Louis Blair (Keyser, WV, USA) submits a position discussed on pages 26-27 of The Chess-Player’s Handbook by Howard Staunton (various – but all? – editions):

Staunton writes:

‘White is enabled to castle, giving check to the adverse king at the same time, and win the game easily, for Black has no square to which he can move his king without going into check, and is consequently obliged to interpose his Q. at K.B’s second or K.B’s third square [f7 and f6 respectively], in either case being checkmated in two more moves, as you will soon be able to see.’

Our correspondent wonders where the mate in two is after ...Qf6.

(2073)

In his Times column on 1 October 1999 Raymond Keene wrote, in amongst all the customary blank space, that Howard Staunton ‘had also embarked on a history of the English Public School system that remained unfinished when Staunton died in 1874’.

However, before us lies the first edition of The Great Schools of England, a 517-page book which was published in London in 1865. A quote from the Introduction (pages xxi-xxii) offers some characteristic Staunton prose:

‘Education in England is at present very much of a chance-medley affair. It has neither unity of object nor of spirit. The whims of individuals, the bigotry of sects, the timid interference of the Government, the tricks of charlatans, sciolism, incompetency, coarse popular feeling, and necessity, all commingle and counteract. What fruits can such a system, or rather such an absence of system, bear? A Minister of Public Instruction would not, it is true, eradicate the whole evil, would not provide a perfect remedy, but he would be an efficient instrument of a great reformation. He would potently help to bring order and unity; he would infuse energy, and would compel even the most recalcitrant and incapable to follow a comprehensive plan. In this country there is a dislike, and a very proper dislike, to that bureaucratic meddling which is the bane of Continental States. But we sometimes suffer as much from the want of centralization as other nations do from its excesses. By all means let bureaucracy, which is the pedantry of despotism, be opposed. Let no dread, however, be entertained of centralization where education is concerned; for vigorous centralization would quicken and stimulate public instruction, enlarge its scope, and hasten its march.’

And from pages xxxvi-xxxvii:

‘Of all the chief modern languages, English is perhaps the worst spoken and the worst written by educated people. It is written too often with an almost total disregard of euphony, elegance, and even grammar; and it is spoken mincingly or mouthingly, with countless horrible disfigurements. Why should not English be written with as much of precision and propriety and classical finish as French? Why should not Englishmen speak as accurately as Frenchmen? We need not, in England, as respects language, be apprehensive of becoming purists; the danger lies in the opposite direction. Pedantry in speech is an evil; barbarism in speech is a greater evil …

That a boy should be able to speak and write his native language as it ought to be spoken and written, is of more solid and lasting importance than that he should excel in the composition of Greek and Latin verses; yet many a boy can do the latter, who is utterly incompetent to the former.’

(Kingpin, 1999)

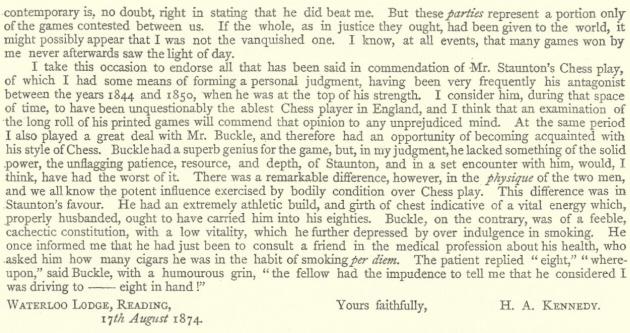

The young Morphy’s well-known ‘devilish bad games’ disparagement of Staunton did untold harm to the Englishman’s reputation in the twentieth century. As G.H. Diggle pointed out in C.N. 1932, P.W. Sergeant gave currency to the gibe in three of his books (Morphy’s Games of Chess, Morphy Gleanings and A Century of British Chess).

The remark was subsequently seized upon by various anti-Staunton writers. Here, for example, is a paragraph from page 3 of Al Horowitz’s book from the early 1970s, The World Chess Championship A History:

‘About Staunton as a player it is perhaps impossible to be strictly objective: it is just too incredible that anyone seemingly so weak as he could have achieved such success and exerted such influence for so long. When the book of the tournament at London in 1851 came into the hands of the then 15-year-old Morphy, the lad felt moved to scribble on the title page, under the legend declaring it to be “By H. Staunton, Esq., author of the ‘Handbook of Chess’, ‘Chess-player’s Companion’, etc.” the irreverent parenthesis “(and some devilish bad games)”. Devilish bad they certainly are, and share with their author’s prose style a turgidity that is truly exasperating. The real secret of Staunton’s success was that he picked his opponents carefully – how carefully will soon become apparent. Only once in his life did he fail to be careful enough.’

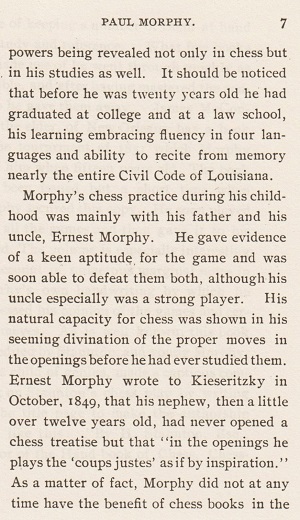

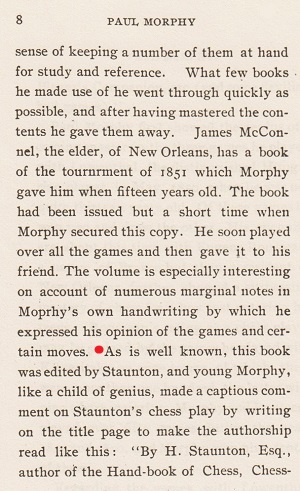

In Morphy’s Games of Chess (page 5) Sergeant quoted C.A. Buck as the source of the ‘devilish bad games’ story. For the record, we cite below what appeared on pages 7-9 of Buck’s book, Paul Morphy. His Later Life (published in Newport, Kentucky in 1902):

‘As a matter of fact, Morphy did not at any time have the benefit of chess books in the sense of keeping a number of them at hand for study and reference. What few books he made use of he went through quickly [sic] as possible, and after having mastered the contents he gave them away. James McConnel [sic], the elder, of New Orleans, has a book of the tournrment [sic] of 1851 which Morphy gave him when 15 years old. The book had been issued but a short time when Morphy secured this copy. He soon played over all the games and then gave it to his friend. The volume is especially interesting on account of numerous marginal notes in Moprhy’s [sic] own handwriting by which he expressed his opinion of the games and certain moves. As is well known, this book was edited by Staunton, and young Morphy, like a child of genius, made a captious comment on Staunton’s chess play by writing on the title page to make the authorship read like this: “By H. Staunton, Esq., author of the Hand-book of Chess, Chess-Player’s Companion, etc. (and some devilish bad games)”.’

The Buck booklet (30 small pages) was brought out by Will H. Lyons, who wrote in the ‘Publishers Prface’ [sic]:

‘C.A. Buck of Toronto, Kansas is the author of this interesting and comprehensive biography of Paul Morphy. Mr Buck has gathered from authentic sources facts and data in the later life of Morphy that have never been published. Several years were devoted to securing information; a month was then spent in New Orleans verifying and adding to his store of facts; Morphy’s relatives and friends giving him great assistance. The matter first appeared in a prominent Western newspaper. With Mr Buck’s consent, I now offer it in its present form …’

Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (pages 213-215) gave further particulars of the genesis of Buck’s work and commented that it ‘appears to be responsible for a number of erroneous statements that have been widely accepted’. Lawson listed many examples, but had not mentioned Buck earlier (i.e. on page 42) when (unquestioningly) relating the ‘devilish bad games’ matter.

On page 54 of The Human Side of Chess Fred Reinfeld asserted that Buck was ‘a subsequent owner of Morphy’s copy’ of the Staunton tournament book, but we recall no other claim that the volume owned by James McConnell (1829-1914) passed into Buck’s possession. Nor do we know what happened to McConnell’s books when he died (in New Orleans on 21 November 1914). Perhaps C.N. has a reader in New Orleans who could investigate further.

(2885)

C.N. 2885 included a passage from pages 7-9 of Paul Morphy. His Later Life by C.A. Buck (Newport, 1902):

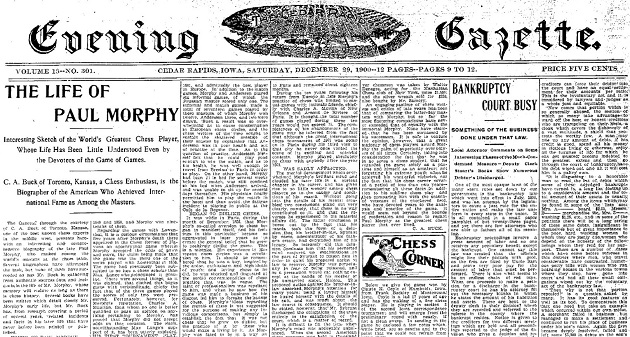

Buck’s text on Morphy had been published on pages 1-7 of the American Chess World, January 1901, introduced as follows:

‘We reprint from the Evening Gazette of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a biographical sketch of the life of the immortal Morphy, by Mr C.A. Buck, of Toronto, Kansas, who is one of the most enthusiastic and best known chess experts in the Middle West.’

On page 214 of his 1976 biography of Morphy, David Lawson gave 29 December 1900 as the date of the article’s appearance in the Evening Gazette. Can any reader provide a copy?

(10293)

The Cleveland Public Library has provided the article referred to in C.N. 10293 (Evening Gazette of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 29 December 1900, page 9):

(10353)

As pointed out in C.N. 155, page 3 of Ray Keene’s Good Move Guide by Raymond Keene and Andrew Whiteley (Oxford, 1982) had, in the very first paragraph, ‘damned’ instead of devilish.

A rare example of [Staunton] being lauded beyond his homeland [at that time, i.e. circa the 1950s]. The text comes from page 137 of Les échecs dans le monde by Victor Kahn and Georges Renaud (Monaco, 1952):

‘Howard Staunton a été non seulement le précurseur de Steinitz et de son époque, mais encore il laisse pressentir le style actuel d’un Botvinnik. Il est regrettable que la gloire factice d’un Anderssen, porté au pinacle par ses compatriotes, ait fait oublier – tout au moins hors de la Grande-Bretagne où son traité se lisait encore avant la première [sic] guerre mondiale – la profondeur des conceptions du champion anglais, conceptions tout à fait surprenantes pour ce temps-là.

Mais Staunton, à son époque, était unique et il n’y avait pas, pour apprécier son style, un climat et un public.’

(3283)

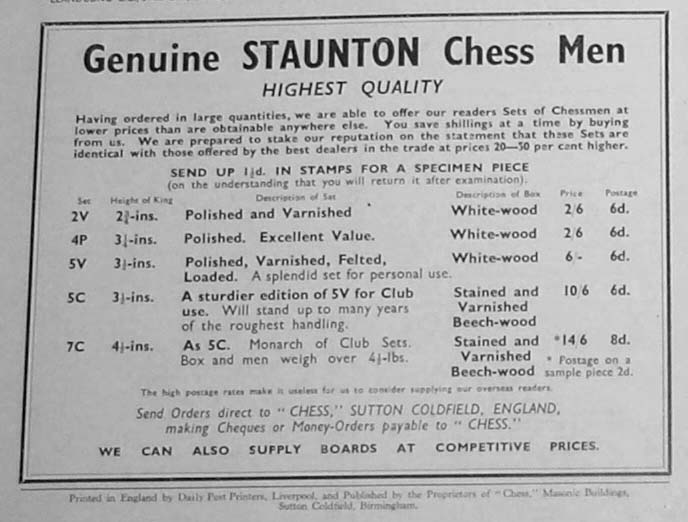

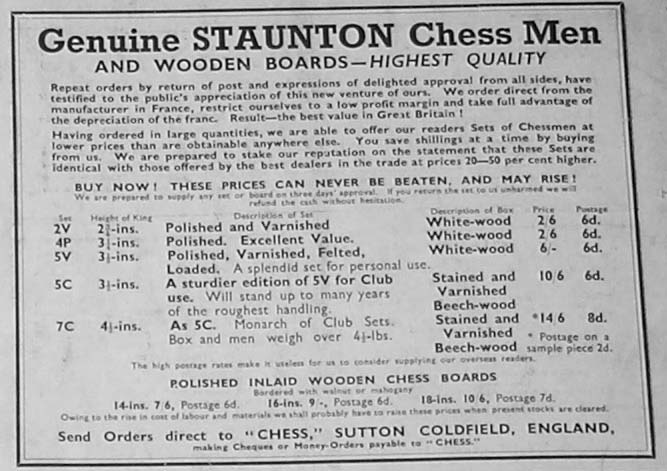

Frank Camaratta (Toney, AL, USA) reverts to a matter outlined in C.N. 360: the court action taken by John Jaques & Son, Ltd. against CHESS after the magazine’s 14 September 1937 issue featured an advertisement for ‘genuine Staunton chessmen’, whereas they had not been manufactured by Jaques. CHESS lost the suit, but won on appeal. In addition to the article by Fred Wren mentioned in C.N. 360, an account of the affair by Gareth Williams on pages 28-31 of CHESS, September 2001 may be noted.

Mr Camaratta asks for a copy of the offending advertisement, as his 1937 issues of CHESS are in bound form and lack the covers (where the magazine’s advertising material appeared). Our own copies for the 1930s are also bound and coverless, but a reader will certainly be able to show us exactly what appeared in issue 25 of CHESS to provoke what the magazine later called (on page 351 of the July 1939 number) ‘the chess lawsuit of a century’.

(3653)

Andy Ansel (Walnut Creek, CA, USA) has sent the back-cover advertisements which appeared in CHESS, 14 September 1937 and 14 October 1937:

(3656)

See Chess in the Courts.

As mentioned in C.N. 4843, on pages 240-245 of the July 1883 BCM W.N. Potter reviewed Chess Life-Pictures by G.A. MacDonnell (London, 1883).

A comment by Potter about the coverage of Staunton:

‘The author has evidently a great admiration of Staunton, and the consequence is a portrait painted in the brightest colours, virtues exaggerated, faults minimized, and gravest flaws suppressed. Very graceful and attractive is such magnanimity on Mr MacDonnell’s part for he was at one time violently, not to say virulently, attacked by the object of his laudation. Horwitz says of Staunton, “I never liked his principles, but he was always a man”. The author quotes and tries to attenuate this criticism; but Horwitz meant what he said, and I think all impartial judges must agree with him. Staunton, however, had splendid talents and, what is much to his credit, they were self-cultivated. The sketch given of him in this book, though highly coloured, is so far real that it gives us a good idea of Staunton in many respects and particularly in those mannerisms and characteristics which constitute the visible man.’

(4844)

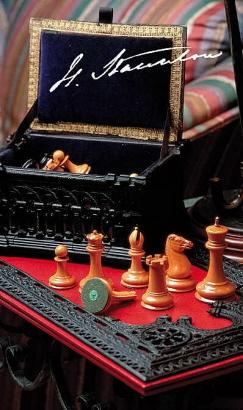

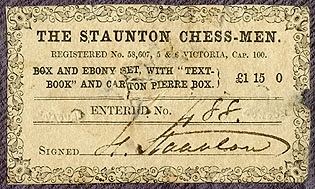

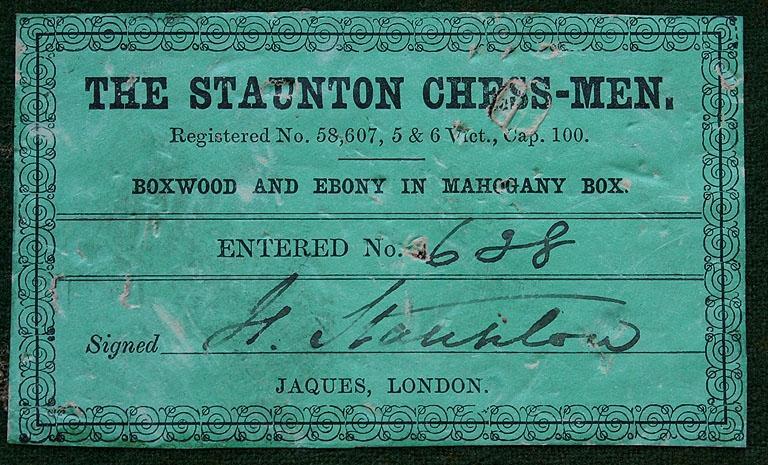

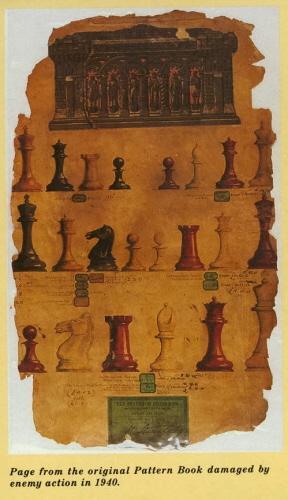

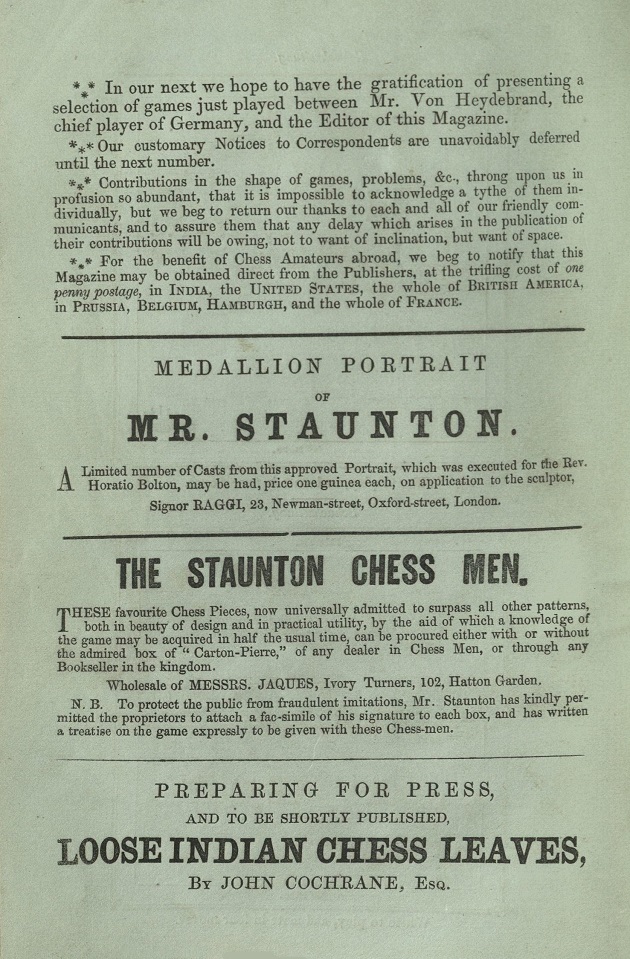

Milan Ninchich (Macquarie, ACT, Australia) enquires about the original price of the first Jaques club-size Staunton set (dated 1849) and asks what is known about the boxes which Staunton signed and numbered by hand.

We consulted the owner of The House of Staunton, Frank Camaratta (Toney, AL, USA), who is writing a book entitled The Staunton Chessmen and their Predecessors. Mr Camaratta has informed us:

‘The original plan was to have Staunton hand-sign and hand-number 1,000 (or possibly 999) of the manufacturer’s paper labels, which were affixed to the bottom of the boxes of Jaques chessmen (wood, ivory, both sizes), and it is known that he signed at least 600, as I have seen specimens with numbering that high. Here is a label from set number 488:

It shows the price of an unweighted boxwood and ebony set with a 3-3/8” king in a carton-pierre casket: £1 15s 0d

The label below is from the large club-size chessmen (4-3/8” king):

The price of the club-size set, loaded with lead, was £2 5s 0d. By contrast, the club-size set made from African ivory was £9 9s 0d in the extra-large carton-pierre casket and £10 10s 0d in a Spanish mahogany case with two partitioned fitted trays for the chessmen. I have seen hand-numbered labels as low as 10.

There was a series of numbered labels which followed, all having a facsimile signature of Staunton and a printed Entered (production) Number. The labels came in three colors: green, yellow and red. The green labels were found only on wooden sets, all sizes, in mahogany hinge-top boxes and were numbered from 1,000 (1,001?) to 1,999. I have seen labels numbered between 1,009 and 1,975. The yellow labels bore numbers from 2,000 to 2,999 and were found only on carton-pierre caskets which housed the smaller (2-7/8” and 3-3/8” kings) unweighted Jaques boxwood and ebony sets. The weighted sets (which were made only in the 3-3/8”, 4” and 4.4” king sizes) could not be housed in the carton-pierre caskets since they would “break through” the sides of those relatively fragile caskets. Finally, the red labels bore numbers from 3,000 to 3,999 and were reserved for ivory sets. Ivory sets were housed in carton-pierre caskets (of which there were three sizes), blue velvet-lined mahogany boxes and the large-fitted (Spanish) mahogany caskets. After that, the labels were not numbered.

There is also a story surrounding the small green round registration stickers found under the bases of the earlier Jaques chessmen.

These gave the class and date of registration for the design. There were actually three designs, and not one as is commonly believed. Two had errors and may well become valuable. There was also a short run of early Jaques labels bearing the incorrect registration number.’

Readers may wish to note that Mr Camaratta has a new company, The House of Staunton Antiques, LLC. He has kindly supplied all the illustrations for the present item, including this final one:

(5104)

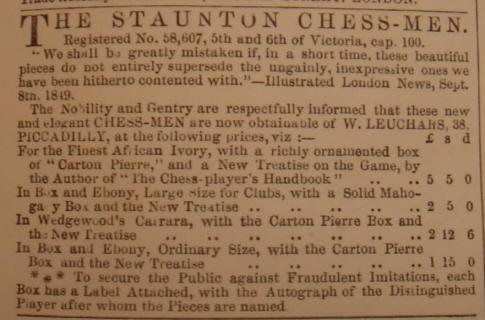

Jon Crumiller (Princeton, NJ, USA) sends the first advertisement for the Jaques Staunton set, on page 223 of the Illustrated London News, 29 September 1849:

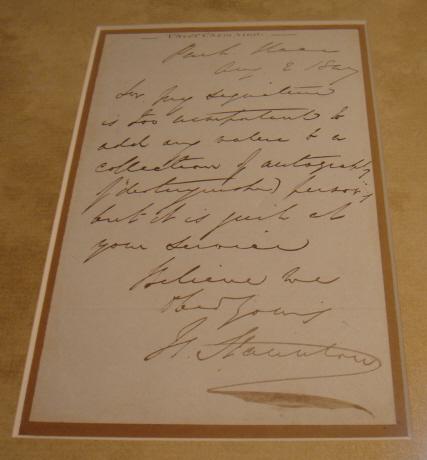

Our correspondent also reports that he possesses a (framed) letter written by Staunton on 8 August 1847 (and headed ‘Chess Champion’):

The body of the letter reads:

‘My signature is too unimportant to add any value to a collection of autography of distinguished persons but it is quite at your service.’

(5111)

John Townsend asks whether it is known where Howard Staunton was living at the time of the 1841 census.

The three addresses in our Where Did They Live? feature article come from later on:

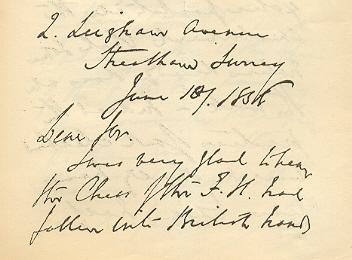

Here we add that pages 411-414 of the September 1891 BCM reproduced in facsimile form an 1858 letter written by Staunton to Charles Tomlinson. The address was 2 Leigham Avenue, Streatham, Surrey.

It is worth noting in this context a passage from page 101 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976):

‘Just how soon Morphy met Staunton is not known, but evidently it was on 23 or 24 June [1858] because he enjoyed Staunton’s hospitality at his country home at Streatham that weekend, as Edge mentions in one of his letters.’

Page 226 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library. A Few Old Friends by D. DeLucia (Darien, 2003) shows part of a four-page letter from Staunton to Fitz-Cook in which Staunton’s address was 27 Chilworth Street, Hyde Park, London. The letter is undated but the opening comment (‘With regard to the Chess World Magazine. Although I doubt whether a periodical solely devoted to chess will ever be a very lucrative undertaking ...’) suggests that it was written in the second half of the 1860s, when he was the editor of Chess World.

Thus the earliest address on hand is from 1849, at the time of his marriage, but where did he live during his bachelor days? The year of interest to our correspondent, 1841, was when Staunton began the Chess Player’s Chronicle, and it may be supposed that he wrote many letters. Have any survived?

(3979)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) draws attention to a footnote on page 49 of A Century of British Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1934):

‘Staunton later [i.e. after 1832] had a house at Richmond; but I have not been able to trace when Staunton’s association with the neighbourhood began.’

Our correspondent also mentions that one of the addresses given in C.N. 3979 (2 Leigham Avenue, Streatham) appeared in an 1850s letter from Staunton reproduced on page 110 of Howard Staunton Uncrowned Chess Champion of the World by Bryan M. Knight (Montreal, 1974). The exact year of the letter is not easy to read.

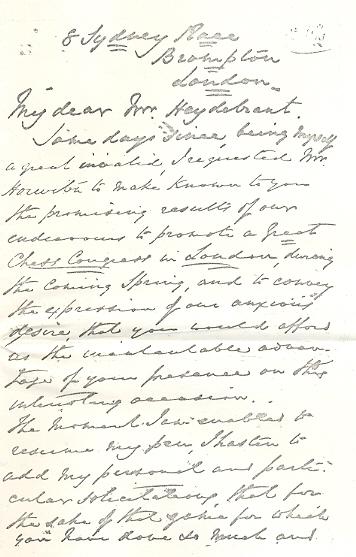

In connection with Knight’s book we add that when, in 1974, Albrecht Buschke sold copies of the limited hardback edition he added for his customers a facsimile of a letter from Staunton to Tassilo von Heydebrand und der Lasa, written from 8 Sydney Place, Brompton on 20 January 1851. From Buschke’s transcript it will be seen that Staunton referred to the astronomer H.C. Schumacher, who was discussed in C.N. 3976, and that he misspelled both Heydebrand and Lasa.

‘8 Sydney Place

Brompton

LondonMy dear Mr Heydebrant,

Some days since, being myself a great invalid, I requested Mr Horwitz to make known to you the promising results of our endeavour to promote a Great Chess Congress in London, during the coming Spring, and to convey the expression of our anxious desire that you would afford us the incalculable advantage of your presence on this interesting occasion.

The moment I am enabled to resume my pen, I hasten to add my personal and particular solicitations, that for the sake of the game for which you have done so much and, I may add, sacrificed so much, you will not suffer any insurmountable impediment to prevent your being present at this striking and unique assemblage – Already from all parts of England, from France, from India & America we have the most gratifying manifestations of sympathy and support, and on all sides there is an anxious longing expressed to learn [hear?] that you will take part in a Congress so fraught with important consequences to the future prosperity of chess.

Do my dear Sir exert yourself to gratify the wishes of the chess community – I wrote to you some weeks ago on [an?] account of our early proceedings through our dear, lost, friend Mr Schumacher, but his illness prevented his communicating with you. In a few days I will send you a programme of the intended assemblage – but, in the meantime, I entreat you to give me the assurance that you will join us. This [That] assurance will induce hundreds to join our standard and infuse the greatest animation through all ranks of players both here and abroad. Should you determine to come, I will later care that you are subjected to conveniences (?) on the score of a residence. London will doubtless be disagreeably full & I have many visitors, but on hearing of the month when you propose coming I will take you comfortable apartments in the neighbourhood of the Town – and on your arrival will meet you in company of Mr Horwitz to convey you from the Railway to my house and from thence to your abode (?).

Anxiously awaiting your reply and with best compliments

I subscribe myself

My dear Sir,

Faithfully yours

H. StauntonHerr Von Heydebrant der Laza

Jany. 20th 1851.’

Page 181 of the 1851 Chess Player’s Chronicle referred to the absence from the tournament of Heydebrand und der Lasa, ‘who, to his deep regret, was unable to leave his diplomatic duties’.

(3984)

From John Townsend:

‘Howard Staunton was commemorated in 1999 by a blue plaque at 117 Lansdowne Road, Notting Hill, London:

“HOWARD STAUNTON 1810-1874

British World Chess Champion

lived here 1871-1874”I believe the dates contain an inaccuracy in that he did not live there until 1872. In my book Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton, published in 2011, his place of residence between 14 February 1872 and 1 April 1872 is clearly traced on pages 153-154 through the contents of four letters which are cited:

- 14 February 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street;

- 13 March 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street: he is “in treaty for a house near to St John’s Church, Notting Hill”;

- 15 March 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street: he extends an invitation to his new home when he moves into it;

- 1 April 1872: written from 117 Lansdowne Road: he moved in “last Saturday”.

Consequently, Staunton did not reside at 117 Lansdowne Road until Saturday, 30 March 1872.

The above-mentioned English Heritage webpage states:

“Staunton’s plaque was therefore erected at 117 Lansdowne Road, where he lived from late 1871 until spring 1874, shortly before his death.”

In the light of the four letters mentioned above, it would be interesting to know what evidence exists for the “late 1871” part of this statement and for “1871” on the plaque.’

(11883)

An addition from John Townsend on 21 April 2023:

‘I wrote to English Heritage to advise them of the error and I recently received a reply from the Senior Historian, Blue Plaques. My research was accepted as “conclusive”, and it was acknowledged that the dates 1872-1874 should have appeared on the plaque, and not 1871-1874.

It was explained that the “arrival date came from the chess writer R.N. Coles”. (He died in 1982.)

The reply also stated that once a plaque is made and installed, there is no correcting it. However, the webpage has been amended to reflect the error.’

From page 149 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘Staunton was pompous and bombastic, a self-appointed dictator of the chess world. On one occasion a rival published a statement that he had won the majority of his games with Staunton. The next time they met Staunton thundered, “You can’t print that!” His rival stammered feebly that the statement was true. “What’s that got to do with it? Of course it’s true!”, Staunton raged. “But you still can’t print it!”’

In C.N. 1624 (see pages 132-134 of Chess Explorations) we quoted Chernev’s version of the anecdote in The Bright Side of Chess, as well as a (significantly different) account by G.A. MacDonnell in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. In both cases Staunton’s rival was named as Löwenthal. Do any other nineteenth-century sources discuss the alleged episode?

(4030)

See too Chess Anecdotes.

On page 11 of The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951) Reuben Fine wrote about Howard Staunton:

‘He wrote, he played, he traveled all over, lecturing and giving simultaneous exhibitions.’

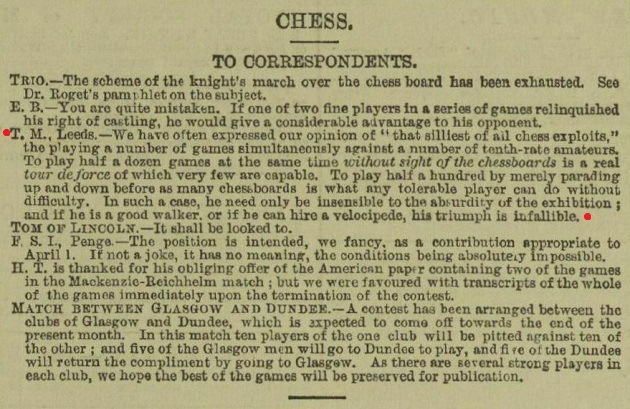

In fact, Staunton shunned simultaneous play, as mentioned in C.N. 594 (see pages 237-238 of Chess Explorations), which quoted the following passage from his column on page 371 of the Illustrated London News, 14 April 1866:

‘We have often expressed our opinion of “that silliest of all chess exploits” – the playing a number of games simultaneously against a number of tenth-rate amateurs. To play half-a-dozen games without sight of the chessboards is a real tour de force of which very few are capable. To play half-a-hundred by merely parading up and down before as many chessboards is what any tolerable player can do without difficulty. In such a case, he need only be insensible to the absurdity of the exhibition; and if he is a good walker, or if he can hire a velocipede, his triumph is infallible.’

What detailed records exist of Staunton playing simultaneous chess?

In his Psychology book (page 30) Fine wrote of Staunton, ‘No brilliant games of his have survived ...’, a remark characteristic of much that used to appear about him in US chess literature. Other examples were quoted in our feature article on Frederick Edge; for a particularly ill-natured paragraph about Staunton by Al Horowitz see page 259 of Chess Facts and Fables.

(4492)

C.N.s 594 and 4492 (see too pages 237-238 of Chess Explorations) mentioned Staunton’s aversion to simultaneous displays, as expressed on page 341 of the Illustrated London News, 14 April 1866:

The difficulty in establishing Morphy’s non-blindfold simultaneous activities was referred to in C.N. 10423.

(11874)

See also C.N.s 11939 and 11992, as well as the following:

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) informs us that the only simultaneous display by Staunton which he has seen mentioned in the Chess Player’s Chronicle is a very small one at the Rock Ferry Chess Club (July 1853 issue, pages 217-218):

After supper and speeches the games were resumed, but the report did not specify the outcome.‘A special Meeting of this Society was held on the evening of the 5th ult. at the Club Rooms, Rock Ferry Hotel, for the purpose of welcoming to Cheshire Mr Staunton, who, during his short visit, was the guest of Mr Morecroft, of the Manor House ... In the course of the evening there was some very interesting play. Mr Staunton conducted simultaneously two games against the Liverpool gentlemen, in consultation at one board, giving them the odds of pawn and two moves, and against the Rock Ferry gentlemen, at another board, giving them the odds of the knight.’

On Morphy, Jerry Spinrad and John Townsend refer to a simultaneous display which is well known. Mr Townsend writes:

‘David Lawson, in Paul Morphy, the Pride and Sorrow of Chess (new edition by Thomas Aiello, 2010), quoted (on pages 213-214) from an account of a simultaneous exhibition which took place at the St James’s Chess Club in London on 26 April 1859, the source being the Illustrated News of the World, of “the following Saturday”:

“A highly interesting assembly met in the splendid saloon of St James’s Hall, on Tuesday evening last [26 April], when Mr Morphy encountered five of the best players in the metropolis.”

The opposition was formidable:

“The first table was occupied by M. de Rivière; the second, by Mr Boden; the third, by Mr Barnes; the fourth, by Mr Bird; and the fifth, by Mr Löwenthal. Mr Morphy played all these gentlemen simultaneously, walking from board to board, and making his replies with extraordinary rapidity and decision. Although we believe that this is the first performance of the kind by Mr Morphy, it is a remarkable fact that he lost but one game. Two other games were won by him and two were drawn.”’

Those reports, one display apiece by Staunton and Morphy, are all that can currently be cited here, although the following may be recalled from C.N. 10423 (concerning Morphy after his match with Anderssen):

‘He confined himself to simultaneous displays, playing 20, 30 and even 40 people at once ...’

Source: page 274 of Keene On Chess by R. Keene (New York, 1999). The identical wording was on page 275 of Complete Book of Beginning Chess by R. Keene (New York, 2003).

(11996)

Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA) writes:

‘A fantasy series by George R.R. Martin (four volumes so far) is popular. The latest volume, A Feast for Crows, refers to a noble family named Staunton and has a character named Alekyne. Martin was once a tournament director for Bill Goichberg’s Continental Chess Association in the United States.’

(4608)

The following account by G.H. Diggle originally appeared in Newsflash, August 1980 and was republished on page 60 of Diggle’s book Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess History contains many shadowy episodes on which only an uncertain light has been shed, chiefly because the sources of information lie in musty volumes now so rare that only eccentrics know where to find them. The six games played in London in May 1843 between Staunton and Saint-Amant (six months before their Great Match in Paris) are a case in point. The scores were all preserved and the result (St A. 3, S. 2, Drawn 1) is not disputed – but did the games constitute a set match, or were they, as Murray claims, “six informal games which the Frenchman afterwards magnified into a chess match”?

Staunton (Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1843) published the games, but said nothing about a match, and informed his readers that “they were of inferior quality, affording nothing like a test of the relative skill of the two players”, that “he had entered the arena for the first time after severe indisposition”, that he ought to have won the second game “without difficulty” and the fifth “easily”, and that in the sixth game “the timidity, so foreign to Mr S.’s usual style of play, which he exhibits in this contest is undoubtedly attributable to the state of his health”.

But Saint-Amant (Palamède, 1843), though he certainly “went to town” over his victory, is full of praise for the sportsmanship both of his opponent, who was “parfait de courtoisie” throughout, and of “la galerie” at the St George’s Chess Club – “comme beaux joueurs et vrais gentlemen les Anglais très certainement sont nos maîtres”. Moreover, his six-page account fairly established that, though hurriedly arranged and for a nominal stake of one guinea only, it was in fact a match, the winner of the first “trois parties” to be declared the victor, draws not counting. The arrangements at the St George’s, St A. informs us, showed commendable “savoir-vivre” – two “obligeants amateurs” sat recording the moves, and an “honorable assistance” instantly conveyed them to “une nombreuse réunion” who eagerly awaited them with chess sets at the ready in an adjoining apartment.

The first game (Sicilian Defence) was won by Staunton as Black after 69 moves and four hours; the second (Bishop’s Opening) was drawn after 90 moves and six hours, the third and fourth (two Giuoco Pianos of 36 and 30 moves played at one sitting resulted in one game all): the fifth (Sicilian) won by St A. after 60 moves and six hours; and the sixth and deciding game (QP Dutch Defence), won by Saint-Amant after 58 moves (adjourned on 52nd move after 6½ hours – duration of final session not recorded, but Staunton occupied 57 minutes over his 56th move). The games themselves show that Staunton (though scarcely in the debilitated state he says he was) did not reveal the subtle positional strategy that he used with such effect in the later and greater match. The best game of the earlier series is probably the drawn one, a fine struggle which was included by R.N. Coles in Battles-Royal of the Chessboard (1948).’

(4706)

Richard Holmes (London) writes:

‘I have been looking up Howard Staunton (1810-74) in the various genealogical resources now available on-line.

In the 1871 census Howard and Frances Staunton were recorded at Gad’s Hill, Northfleet in Kent, but I cannot find that place on a modern map; the Gadshill where Charles Dickens once lived is not far away, but surely could not be described as Northfleet. Howard Staunton’s occupation was given as “professional writer” and his birthplace as Keswick, Cumberland (rather than Westmorland, as seen in other sources). The reference is RG10/897/69/21.

In the 1861 census the couple were visiting the sisters Emma and Martha Englehart in Isleworth. Howard Staunton was recorded as “Author (scientific & general literature)”, and his birthplace was given as “in the Lakes” (RG9/771/50/12).

In the 1851 census Staunton and his wife were at 8 Sydney Place, Kensington with two of her relatives and two servants. He was described as “Journalist and Annuitant”, his birthplace being recorded as Westmorland (HO107/1469/322/33).

I cannot find Howard Staunton in the 1841 census.

As is well known (and is confirmed by www.familysearch.org), he married Frances Carpenter Nethersole on 23 February 1849 at St Nicholas, Brighton. However, a further fact derived from that website which I have not seen noted is that Frances Carpenter and William Dickenson Nethersole had no fewer than eight children baptized at St Clement Danes between 1826 and 1842.

The baptismal entries for 1810 at Crosthwaite, the parish that included Keswick, were also consulted via the above-mentioned website; they show around 40 male baptisms, but none named either Howard or Staunton. None of this throws any real light on Howard Staunton before the first documented appearance generally quoted (1836) but may offer clues for further research.

The obituary in The Times, 30 June 1874, page 8, quoted a press release from the Athenaeum which appears to be the source for several of the “facts” about his life, e.g. that he attended Oxford without taking a degree and that he once played Lorenzo to Kean’s Shylock.’

(4776)

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) asks whether detailed research has been undertaken into claims that Staunton was an actor.We believe that the best treatment of the subject, though still inconclusive, is by John Townsend on pages 25-30 of Notes on the life of Howard Staunton (Wokingham, 2011).

(10461)

From John Townsend:

‘If the story is true that Howard Staunton played Lorenzo to Edmund Kean’s Shylock, a likely venue is the small theatre at Deptford, for the reasons given on page 26 of my 2011 book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.

One small development since 2011 has been identification of a performance in which Kean played Shylock at Deptford. Page 3 of the Morning Post of 14 March 1831 reported that Kean had played that role in The Merchant of Venice at the Deptford Theatre the previous Saturday, 12 March, for the benefit of a Mr Ormond, to a full house.

I have not discovered who took the part of Lorenzo. If a playbill for the performance has survived, it should contain the name of the actor, but none has been located so far.’

(10466)

From the chess section on page 18 of The Boardgame Book by R.C. Bell (Los Angeles, 1979):

‘[Staunton] designed a board in 1843 which has since become the standard European board.’

(4827)

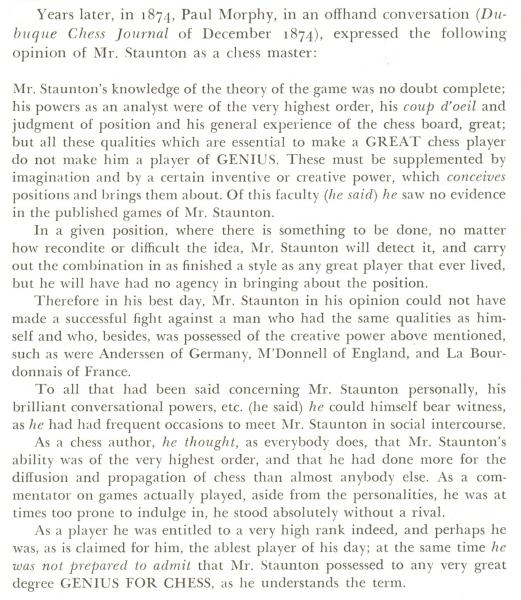

A feature on page 104 of Fred Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951) entitled ‘Morphy’s Estimate of Staunton’ was taken from page 410 of the September 1891 BCM, but the latter offered no source. For that, and a more extensive version, we turn to page 155 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976):

Is a reader able to supply the item as it appeared in the Dubuque Chess Journal or in any other source during Morphy’s lifetime? We should like to know the exact context and circumstances of this ‘offhand conversation’.

(5008)

Below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, is the item published in the Dubuque Chess Journal:

Jon Crumiller sends a cutting from page 4 of the Wisconsin publication the Whitewater Register of 31 July 1858. Readers are naturally advised to treat it with great prudence.

(5283)

From the obituary of Howard Staunton on pages 232-234 of the August 1874 Huddersfield College Magazine:

‘... Mr Staunton had the sole charge of the weekly chess column in the Illustrated London News since its commencement in 1842, for which, if we are rightly informed, he received a very handsome stipend. Some idea may be formed of the labour which devolved upon him in this connection from the fact that his correspondence, as he himself stated to the writer of this article, averaged 700 letters weekly.’

(5488)

John Townsend notes that the Huddersfield College Magazine was incorrect to state that Staunton’s column in the Illustrated London News began in 1842, the right date being 1845.Our correspondent forwards two quotes from the Illustrated London News:

‘We have great pleasure in announcing to our chess subscribers and readers generally that we have secured the valuable services of Mr Staunton, the eminent chessplayer, to edit the chess department of the Illustrated London News.’

‘“Scacchi”, Glasgow must be aware that the gentleman to whom he directs his comments is not in any way responsible for the errors which may be found in this department of our paper prior to 22 February ...’

(5492)

From page 105 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1841 (an answer by Staunton to a correspondent):

‘“XYZ, BRAINTREE”: We reply to every communication that reaches us: our correspondent’s letter was not received.’

(5513)

Three correspondents offer information about Howard Staunton’s standing as a Shakespearean scholar.

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) draws attention to the Shakespeare’s Editors [link broken] webpage on Staunton, which quotes from the entry on the latter in the 1909 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography.

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) refers to the 1979 edition of Staunton’s work published by Park Lane, New York:

‘The Foreword, by Solomon J. Schepps, comments on page xiv that Staunton:

“... was one of the great Shakespearean scholars of his age. His knowledge of the texts themselves and of Elizabethan language and customs was enormous. And, equally to his credit, he understood the importance of including extra material in this edition.”

However, in the 1969 Pelican Shakespeare I can find no mention of Staunton, although other nineteenth-century volumes by other editors are cited.’

From William D. Rubinstein (Aberystwyth, Wales):

‘Staunton’s name can be found in modern reference books on Shakespeare, but only briefly and not invariably. For instance, he does not appear at all in Shakespeare’s Lives by S. Schoenbaum, the standard work on how Shakespeare has been discussed and examined since his death. Staunton’s views on the meaning of a word in Shakespeare are occasionally cited in recent editions of the plays, such as the Arden and Oxford publications, but, again, not often.’

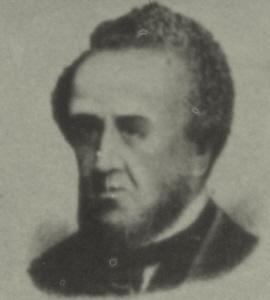

Howard Staunton

Finally for now, we add a brief item from page 81 of the February 1888 BCM:

‘In the course of a speech which Mr Routledge, the eminent publisher, made lately at a complimentary dinner, he paid a high tribute to the literary abilities of the late Howard Staunton, and stated that his firm had paid that gentleman £1,000 for editing his edition of Shakespeare. The work was a labour of love on the part of the great chessplayer, but nevertheless the payment would be welcome.’

(5516)

From Richard Allen (Cambridge, England):

‘The commentary on this subject in C.N. 5516 indicated that while Howard Staunton was a Shakespearean scholar and editor of considerable learning and distinction in his own time, his contribution to this field is only briefly and occasionally recognized today. This is unsurprising, given that Shakespeare studies have become a mass global industry in the modern age. Indeed, one aspect of this development, large collaborative projects supported by prestigious institutions, was already under way in Staunton’s own day. His three-volume edition of Shakespeare’s plays (1858) may have earned him £1,000 but it was a labour of love on the part of a self-taught, unaffiliated amateur. It nevertheless won plaudits for its careful and judicious collation of available texts, as well as for other virtues to which I shall return. Unluckily, however, it was rather overshadowed by the appearance only five years later of The Cambridge Shakespeare (1863-66), edited by W.G. Clark, J. Glover and W.A. Wright. This publication, according to J. Isaacs on pages 305-324 of Shakespearian Scholarship, A Companion to Shakespeare Studies by H. Granville-Barker and G.B. Harrison (Cambridge, 1934), “was the great landmark [in Shakespearean scholarship] of the mid-century ... Its rigorous system of collation was facilitated by [Edward] Capell’s superb bequest of quartos to Trinity College’ (page 314). Two further landmarks of collaborative scholarship, J.J. Furness’s New Variorum Edition and the foundation by F.J. Furnivall (“a team-leader”, according to page 315 of Isaacs’ work) of the New Shakspere [sic] Society, followed in 1871 and 1872 respectively. By comparison with these monumental enterprises, Staunton’s achievements must already have appeared somewhat modest by the time he died in 1874.

That, however, is by no means the whole story. Both The Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness’s Variorum were produced by academic specialists for an academic audience; they were tomes to be consulted mainly in university libraries. Staunton’s edition, by contrast, was produced for the general public, first appearing – like a Dickens novel of the same period – in shilling monthly parts. And again like a Dickens novel, only more so, it contained an abundance of distinctive illustrations; there were some 831 sketches by John Gilbert, all engraved by the Dalziel brothers, making Staunton’s edition, according to Peter Holland – see page 65 of volume one of Performing Shakespeare in Print: Narrative in Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Shakespeares, Victorian Shakespeare by G. Marshall and A. Poole (London, 2003) – “the most popular of mid-nineteenth-century illustrated Shakespeares”. The combination of popular appeal and editorial standards that were still acceptably high accounts for its twentieth-century reprint (referred to in C.N. 5516), which remained in print until the early 1990s – “an extraordinary longevity for any Shakespeare edition”, as Holland remarks (volume one, page 67).

There were many illustrated Shakespeares published in the nineteenth century, but in even some of the more notable, such as Charles Knight’s National Edition of 1851, the pictures tend to be undramatic and de-contextualized. In Staunton’s edition, on the other hand, Gilbert’s prodigiously numerous sketches are embedded in the text, providing dramatic vignettes from various distances and perspectives, and foregrounding character. Thus, argues Holland, was “created a dramatic narrative of performance, as close an interconnection between illustrations and the performed text ... as the century could ever have hoped to achieve” (Marshall and Poole, volume one, page 71).

While naturally keen to represent Gilbert as “the powerhouse for the edition” (Marshall and Poole, volume one, page 68), Holland acknowledges Staunton’s “decent and honourable” editing (page 68) and notes that a few of his emendations have retained acceptance among modern editors. The tribute is very much to the point but perhaps understates Staunton’s achievement. The main reason for the small number of emendations retained today is that Staunton actually proposed only a few. This was in keeping with the deliberate modesty and moderation of his whole editorial approach, in which a wide range of available readings has been considered but the oldest (quarto) ones usually adopted unless there is a strong case against. Staunton’s methods need to be seen in the context of the sensational forgeries perpetrated by a leading Shakespearean of the day, J. Payne Collier. In 1853, Collier published Notes and Emendations to the Text of Shakespeare’s Plays, in which he listed marginal annotations in a seventeenth-century hand purportedly discovered in a copy of the Second Folio he had bought in a bookshop. The authenticity of this discovery was soon questioned, but the document and numerous others that Collier claimed to have found were not conclusively proved to be forgeries until 1859. In a detailed account of this shocking case in the Preface to the 1860 edition of his Shakespeare, Staunton states that he himself instigated the scrutiny of the fabricated documents by Sir Frederic Madden, N.E. Hamilton, and other professional “paleographers” at the British Museum; he was prompted, he says, by a sense of responsibility to have the issue determined before his own editorial project saw the light of day. The investigation took longer than anticipated because of Collier’s obstructiveness, but it is clear that Staunton’s commitment to “decent and honourable” editing was reinforced by Collier’s gross transgression of such standards. Staunton’s other major publication in the field, Memorials of Shakespeare (1864), a collection of photolithographic facsimiles of extant documents such as the dramatist’s will and the indentures of conveyance and mortgage of his house, can be seen as similarly motivated by a desire to help restore the values of fidelity and authenticity to popular Shakespeare scholarship.

The essay on Staunton on pages 319-321 of volume 52 of the new Dictionary of National Biography by H.C.G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford, 2004), an updating by Julian Lock of Sidney Lee’s original article, recognizes his immense contribution to the world of chess while noting flaws of personality displayed therein – for example, his tendency to become involved in vendettas and the hint of class snobbery betrayed in his leadership of St George’s feud with the London chess club. It is interesting that such weaknesses seem much less evident in Staunton the Shakespearean. In his strictures on Collier’s malpractice he does not resort to personal denigration, and he even deprecates the undue “stringency” of a previous attack on the wretched forger. And though largely forgotten today, his own distinctive achievement in this field was to produce a reputable version of Shakespeare in an accessible and attractive format.’

(5603)

C.N. 4870 invited readers to identify the person whose obituary stated that ‘a man of his literary distinction is an honour to the game’ – a nineteenth-century figure who died in his sixties and was known not only for his activity in the chess world (e.g. the Chess Player’s Chronicle and the Illustrated London News) but also for his writings on Shakespeare as from circa 1860.

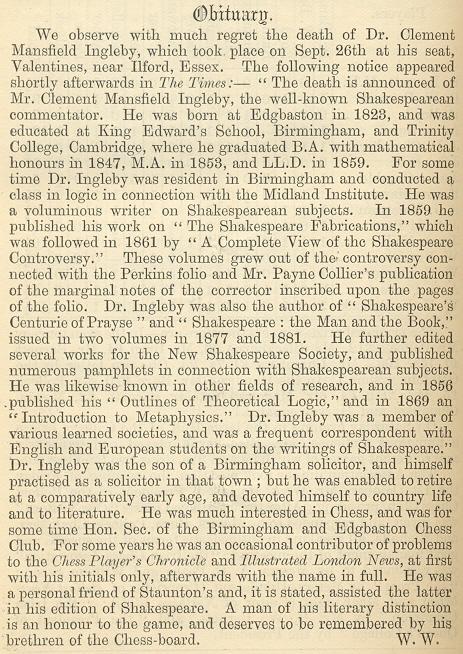

It was not Howard Staunton (1810-74) but Clement Mansfield Ingleby (1823-86). Below is the complete obituary published on page 416 of the November 1886 BCM:

(4876)

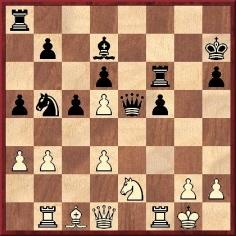

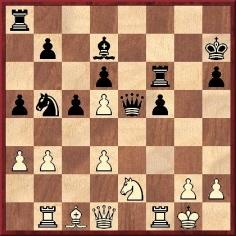

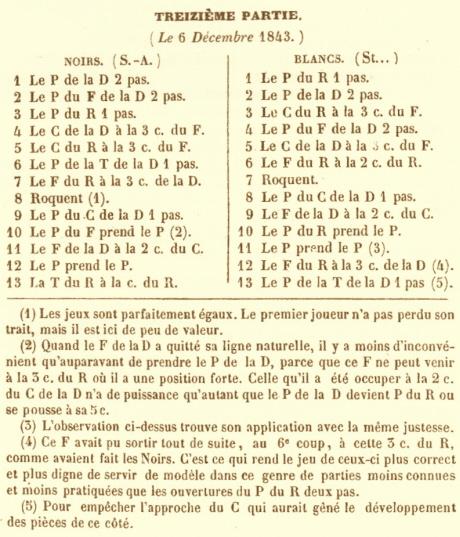

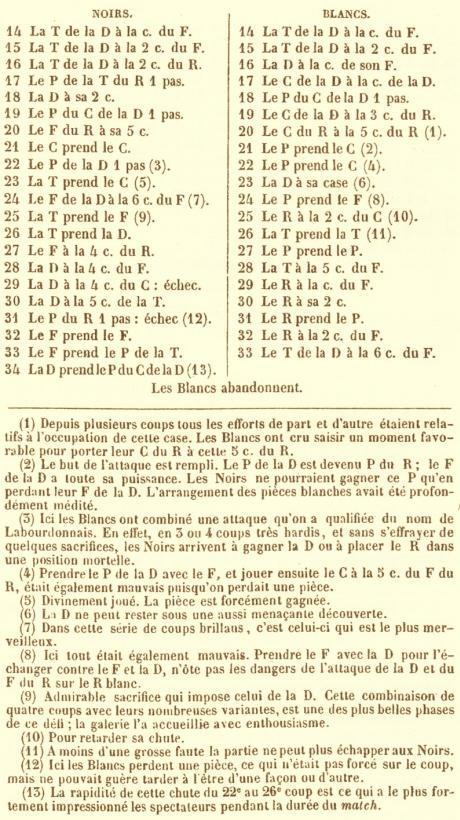

An annotational disagreement occurred between Staunton and Saint-Amant regarding two positions in the 16th game of their match in Paris, played on 11 December 1843.

Here, Staunton played 20 exf5, and Saint-Amant commented on page 66 of the February 1844 issue of Le Palamède:

‘Ceci est un désavantage, car les 2P de la D doublés ne sont plus liés ensemble, et le plus avancé sera peut-être difficile à défendre.’ [‘This is disadvantageous, as the doubled d-pawns are no longer linked together, and the more advanced one will perhaps be difficult to defend.’]

Staunton quoted this in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 April 1844, page 99 and responded:

‘Now we, on the contrary, opine that the taking this pawn increased the advantage in position which White had previously obtained.’

After 20 exf5 the game continued 20...gxf5 21 Nh5 Qe8 22 Nxf6+ Rxf6 23 fxe5 Qxe5.

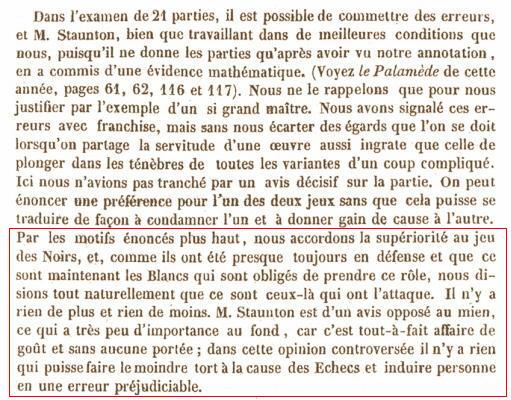

At this point Saint-Amant commented in Le Palamède:

‘Bien préférable à prendre du P. Les Noirs ont maintenant l’attaque, et leur jeu est supérieur à celui de leur adversaire.’ [‘Much better than taking with the pawn. Black now has the attack, and his game is better than his opponent’s.’]

In the Chess Player’s Chronicle, Staunton disagreed:

‘In the Palamède for February, page 66, note (6), we are gravely told at the present point, “Les Noirs ont maintenant l’attaque (!!), et leur jeu est supérieur à celui de leur adversaire” (!!!). We shall have much pleasure in affording the Editor of Le Palamède an opportunity of verifying this, to us, somewhat startling assertion; and for the purpose, we undertake, on his next visit to London, to play White’s game against him from this move, half-a-dozen times, for as many guineas as he may think proper to risk on the result.’

Saint-Amant reverted to these matters on pages 164-168 of the April 1844 issue of Le Palamède. Concerning 20 exf5 he maintained his standpoint, adding that it was a question of theoretical principle on which most experts would agree with him. (‘Nous ne voyons pas dans les paroles de M. Staunton le moindre motif de rien changer à ce que nous avons dit. Ceci est une question de principe théorique, sur laquelle nous ne craignons pas d’avancer que nous aurons certainement la majorité des connaisseurs de notre côté.’)

As regards the second position, Saint-Amant maintained that Black had the attack, whilst adding that it was a matter of taste:

The two positions entail general positional considerations, rather than specific analysis, and we should like to know how a modern master assesses the respective views of Saint-Amant and Staunton.

The game, which Saint-Amant won at move 58, lasted nine hours (Le Palamède, February 1844, page 66).

(5709)

Regarding the annotational disagreement between Staunton and Saint-Amant arising from the 16th game of their match in Paris in 1843, the first diagram below shows the position after 19...Na7-b5. Play continued 20 exf5 gxf5 21 Nh5 Qe8 22 Nxf6+ Rxf6 23 fxe5 Qxe5, reaching the second diagram.

Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam) writes:

‘After 19...Nb5 I much prefer Black’s position. I consider Staunton’s move 20 exf5 to be dubious because, as Saint-Amant correctly points out, the d5-pawn becomes weak. After 21 Nh5 I would have played 21...Bh8, retaining the two bishops and raising the question of what the white knight is actually doing on h5.

Regarding the second position, I am not sure that Black stands better any more, and he may have frittered away his advantage at this point by failing to keep his two bishops. So is Saint-Amant’s claim that Black has the attack true? After 24 Bb2 Nd4 (if 24...Qe3+ 25 Kh1 Rf7 26 Rf3 and 27 Nf4, I do not see Black’s “attack” at all) 25 Bxd4 cxd4 26 Nf4, and White’s problems are over.’

(5715)

Further to the Tarrasch-Lasker story (C.N. 5707), we note the following variation on a theme: a passage by Saint-Amant in the course of his bitter public dispute with Staunton. It comes from page 40 of Le Palamède, January 1845:

(5719)

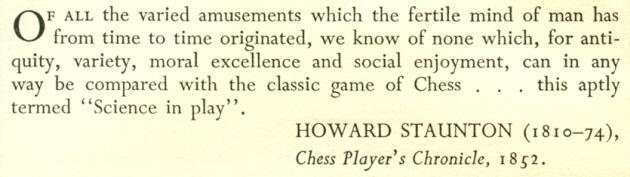

From page 10 of Chess Pieces by N. Knight (London, 1949):

From page 144 of Caissa’s Web by Graeme Harwood (London, 1975):

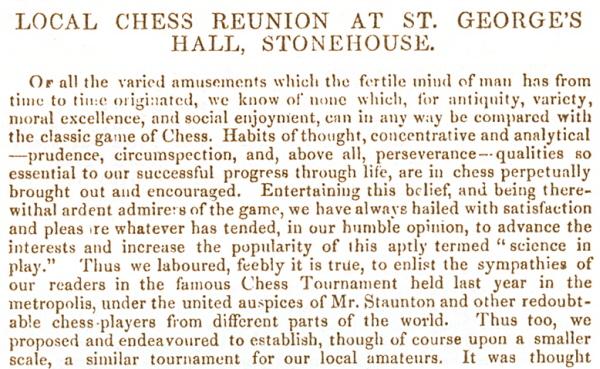

The passage comes from the first paragraph of an article on pages 189-191 of the 1852 volume of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, but the magazine stated, on page 191, that the article was taken from the West of England Conservative Journal. What grounds could there be for ascribing the text to Staunton?

(6055)

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) notes the curious discrepancies futile/fertile and variety/vanity in the versions reproduced by N. Knight and G. Harwood. It is the latter who went awry. Below is the passage from the West of England Conservative Journal as it appeared on page 189 of the 1852 Chess Player’s Chronicle:

(6061)

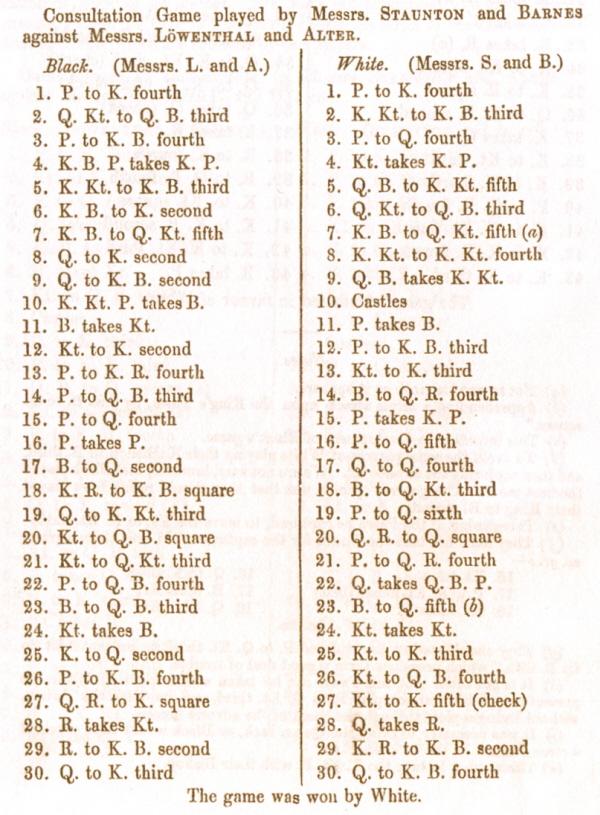

Dan Quigley (Augusta, GA, USA) asks about an encounter involving Löwenthal and Staunton (London, 1856) which may be found listed in databases as a consultation game:

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d5 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 Be2 Nc6 7 Bb5 Bb4 8 Qe2 Ng5 9 Qf2 Bxf3 10 gxf3 O-O 11 Bxc6 bxc6 12 Ne2 f6 13 h4 Ne6 14 c3 Ba5 15 d4 fxe5 16 dxe5 d4 17 Bd2 Qd5 18 Rf1 Bb6 19 Qg3 d3 20 Nc1 Rad8 21 Nb3

21...a5 22 c4 Qxc4 23 Bc3 Bd4 24 Nxd4 Nxd4 25 Kd2 Ne6 26 f4 Nc5 27 Rae1 Ne4+ 28 Rxe4 Qxe4 29 Rf2 Rf7 30 Qe3 Qf5 0-1.

Our correspondent also mentions a database where 21...a6, and not ...a5, is given.

We note that the game was published on pages 28-29 of the 1859 Chess Player’s Chronicle:

Löwenthal’s partner (‘Alter’) was John Owen.

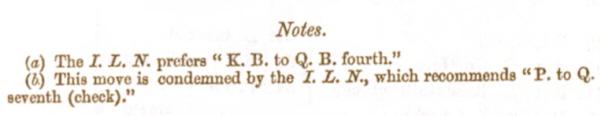

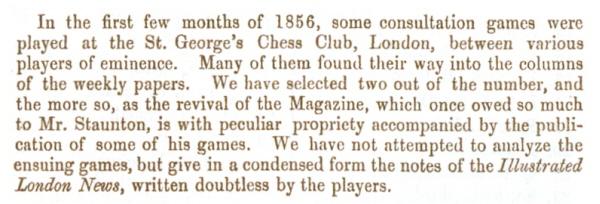

Another consultation game (Löwenthal and Barnes v Staunton and Alter) was on pages 26-28 of the Chronicle, with this introduction on page 26:

With regard to the Illustrated London News, Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) kindly informs us that the game under discussion was in Staunton’s column on page 258 of the 8 March 1856 issue (with 21...a5). Mr Edwards adds:

‘After Staunton and Barnes’ 30...Qf5, Staunton stated in the Illustrated London News that “The remaining moves were not recorded, but the game was won by White”. It should be borne in mind that Staunton and Barnes had the white pieces.

It was one of a series of consultation games played between Staunton and Löwenthal in which each player had various allies. Sometimes the allies even switched partners. The series was announced on page 187 of the 16 February 1856 Illustrated London News, where the result of the first two games was given. Cumulative scores were provided periodically, and the last tally that I have found was in the 13 September 1856 magazine (page 281): “Staunton and Co.” had nine wins and “Löwenthal and Co.” five, with two games drawn. However, consultation games between Staunton and Löwenthal with various allies continued to be reported sporadically until the 4 July 1857 issue (page 22).’

(6455)

Rod Edwards writes:

‘The record of Howard Staunton’s matches given on pages 129-130 of your 1981 book World Chess Champions shows the result of his match with Charles Henry Stanley at the odds of pawn and two moves as +2 –3 =1, and the year is given as 1841. The Oxford Companion to Chess (first edition, page 324; second edition, page 389) concurs on the result and the year. Feenstra Kuiper’s Hundert Jahre Schachzweikämpfe (page 12), Golombek’s Encyclopedia (pages 307 and 456 of the hardback and paperback editions respectively) and Chess Results, 1747-1900 by Di Felice (page 3) all have the same result but give the year as 1839. Fiske’s New York, 1857 tournament book (page 406) states that the match was played not long before Stanley’s departure for the United States (which he says was in 1842), and that Stanley won “by a large majority”.

However, in the 1842 volume of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (page 368) Staunton wrote:

“Messrs St--n and S--y have played in all but 12 games, exclusive of drawn ones, at the odds of ‘the pawn and two moves’. Of these 12, Mr S--y won seven, and Mr St--n five.”

I wonder where the +2 –3 =1 result comes from originally, and how it can be reconciled with Staunton’s claim in the Chess Player’s Chronicle.

World Chess Champions indicates (page 130) that in cases where the final scores were not known the match results given “are those of surviving games”. Presumably, this does not apply to the Staunton-Stanley match, since I count eight game-scores in volume two of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (pages 117-118, 200, 211-212, 213, 226-228, 241-242, 293-294 and 324-325), amounting to +3 –4 =1 for Staunton. I wonder whether all these games were considered part of the formal match.’

The Staunton biography and results tables in World Chess Champions were by R.N. Coles. The only addition that we can offer at present is that an account of Stanley’s life on pages 364-367 of the August 1982 BCM (following research by Jeremy Gaige) stated that Staunton was defeated +2 –3 =1 and that the contest took place in December 1841.

(6563)

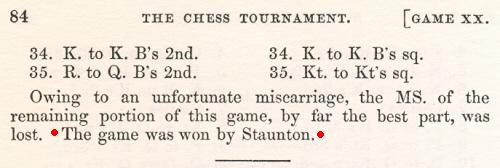

Mario Ziegler (Nonnweiler, Germany) refers to the fifth game in the Staunton v Horwitz encounter at the London, 1851 tournament. Page 84 of Staunton’s tournament book gave the moves 35 Rc2 Ng8 and then stated:

‘Owing to an unfortunate miscarriage, the MS of the remaining portion of this game, by far the best part, was lost. The game was won by Staunton.’

Our correspondent asks, firstly, whether the missing moves are available anywhere.

Secondly, he points out that if Staunton did indeed win that game his total score in the match against Horwitz would be +5 –2 =0, since all seven games (pages 71-88) were indicated as having a decisive outcome. However, page 38 stated:

‘In this section the victory in each contest was adjudged to the player who first won four games.’

Moreover, page 174 gave the final score between Staunton and Horwitz as +4 –2 =1. The question, therefore, is which of the seven games was drawn.

We note that page 219 of the 1851 Chess Player’s Chronicle stated that it was the fourth match-game, but can that be so? The tournament book (page 82) shows that game as finishing with an overwhelming advantage for Staunton (after his final move 33...b2):

Restrictions were initially placed on the dissemination of games from London, 1851, as shown by the first quotation in Copyright on Chess Games.

(6598)

C.N. 6598 quoted the concluding note on page 84 of Staunton’s book on the London, 1851 tournament, concerning his fifth match-game against Horwitz:

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) points out that in a subsequent edition of the tournament book (published by Bell & Daldy, London in 1873) the text was amended to state that the result was a draw:

Below is the title page of the 1873 edition:

(6601)

A number of comments on Hoyle by Staunton in the Illustrated London News are drawn to our attention by Jon Crumiller:

(6790)

The book also contains carefully-researched material about some secondary figures discussed in C.N., such as T. Beeby, F.M. Edge and J. Worrell.

(7038)

Further to the item (C.N. 7277) about Bernhard Horwitz’s application for support from the Royal Literary Fund, John Townsend writes:

‘It seems that Clement Mansfield Ingleby, a Shakespeare critic and chessplayer, had some influence in such matters. He held a position at the Royal Society of Literature, 4 St Martin’s Place, and he wrote to the Prime Minister, Disraeli, immediately after Staunton’s death, seeking a pension on the Civil List for Staunton’s widow. (See page 167 of my recent book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.)

One way of dealing with such requests was via a grant from the Royal Bounty, which was one of the classes of the Civil List, being at that time under the administration of the Prime Minister. In Mrs Staunton’s case, a lump sum of £200 was granted. (See Records of the Royal Bounty (1868-1880), National Archives, PMG 27/62, page 136 (1874).) If Horwitz’s application followed a similar course, one might hope to find an entry during 1872 or 1873 in the same group of records at the National Archives.’

(7287)

An article by G.H. Diggle published in the March 1980 Newsflash and reprinted on page 55 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘In the February Newsflash the Editor refers to the Olympic controversy and invites general comment on “politics and sport” with special reference to chess. The Badmaster, far too timorous and cagey a bird to accept such a gambit as this, will confine himself to recounting what actually took place when a boycott of a famous international chess tournament was attempted 130 years ago. In 1851 England, as the greatest nation in the world, staged the Great Exhibition, and Howard Staunton, as the greatest chessplayer in the world, proposed that England should be host country of the First International Chess Tourney. The conception of this idea was magnificent, and its execution by Staunton a tremendous feat, when travel was still so slow and inter-communication so poor. Yet the success of the tournament was jeopardized not only by these difficulties but by a boycott which, however, emanated not from outside countries’ dislike of Britain but from dislike in certain quarters of Staunton himself. For the great man, splendid chess leader as he was, possessed every quality except tact. His aggressive and overbearing personality had put him at variance with the wealthy and powerful London Chess Club. He himself was confidently expected to win the tournament, if it came off; and (as is now said of the Soviet Union) it was said by his enemies that his real object in organizing the event was to puff himself. Consequently, “the London” would have nothing to do with it; Harrwitz (their professional) did not compete; and out of the much-needed £550 raised in subscriptions by Staunton’s efforts, only two of their members subscribed (John Cochrane then in India and their venerable honorary member William Lewis). In the end seven foreign masters arrived and competed with nine Englishmen not all of their calibre, especially “Mr Mucklow, a player from the country never before even heard of” – his very name, indeed, suggesting a rustic crewyard. Before their boycott, the London Chess Club had toyed with the idea of getting the venue changed from the St George’s Club to their own; and after the tournament (in spite of the boycott) had run to its conclusion on 21 July 1851 they hastily arranged a rival tournament at their own club for foreign masters only, to which they invited Anderssen, Deacon, Harrwitz, Horwitz, Kieseritzky, Ehrmann, Meierhofer, Löwe and Szabo. Each player had to play one game with every other (the very first “American” tournament) but, rather stupidly, the Club offered one prize only (a gold cup valued at 100 guineas). This left no inducement to players who did badly at first to go on playing. Harrwitz, indeed, took flight after losing one game; Kieseritzky had already left London for Paris whither his invitation followed him; but when the luckless French master recrossed the Channel and again reached London, half the players had packed in and he only got three games, losing to Anderssen and Meierhofer and beating Szabo. Only about 20 games were played in all, and Anderssen alone played his full quota, winning the cup with a score of 8-0-1. To sum up, the boycott damaged but did not ruin Staunton’s tournament, and the rival tournament was a shambles. Will history repeat itself in 1980?’

(7705)

What is the fairest brief description of Howard Staunton’s organizational involvement in the London, 1851 tournament?We put the matter to John Townsend, who responds:

‘“Played a leading role in” would be my choice.

However, there were limits to his involvement and responsibility. The Committee included several aristocrats, who could be infinitely more powerful than he was.

Rivalry existed between the London Chess Club and the St George’s and, where there was conflict, Staunton has been blamed. However, his was only one voice on the Committee – albeit an important one – so he was not solely responsible for decisions taken. Neither was Staunton the Secretary of the Committee. That was Miles Gerald Keon, and it was he who dealt with correspondence on behalf of the Committee.’

(11870)

This article by G.H. Diggle, originally published in Newsflash, April 1981, was given on page 67 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess matches have often been abandoned half-way through by demoralized combatants after successive wins have been piled up against them; Harrwitz v Morphy and Kostić v Capablanca are notable examples. Dr Hübner’s recent resignation to Korchnoi is a more unusual case, as he was only potentially 4-6 down with six games to play. In 1851, however, there were two similar match resignations caused (as in Hübner’s case) by stress, though in both cases the stress was not due so much to “world publicity” as to the “intolerable tedium” of pre-time-limit chess. In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) “rather than undergo the torture of another game”. The other case (though recounted in the BCM for February 1940) is less well-known. In one of the “side-shows” of the great 1851 tournament, the youthful Frederic Deacon, burning with eagerness to win his chess spurs, was, though already notorious for slow play, selected very injudiciously by the Committee to play a match of seven games up with Edward Löwe, then a perfunctory old stager nearly 40 years Deacon’s senior. The prizes were £8 to the winner and £3 to the loser, and Deacon won the first two games, with Löwe moaning throughout about Deacon’s slowness. In the third game (Deacon later wrote to the Tournament Committee) “Mr Löwe noted the time I took to consider a move and then delayed double that time before he made his own – this was in the presence of Mr Löwenthal and Mr Williams.” (The BCM comments, “We can imagine Williams scenting tedium and watching this new experiment with the air of a patron.”) Deacon’s attempt to speed things up led to his losing the game in 37 moves after a mere four and a half hours’ play. Finally in the fourth game, as Deacon was considering his 16th move after about two and a half hours’ play “when I had unquestionably the better game” Löwe suddenly resigned the match and walked off. To all arguments to induce him to resume the contest Löwe replied that he found there was no time to fulfil his business engagements if he had to play any more chess with Deacon, to whom he resigned the prize. “I cannot say fairer!” This left Deacon with no other course but to write to Staunton as Secretary of the Tournament troubling the Committee for “the prize which I of course believed to be my due”. Then came the unkindest cut of all. “The Committee were not prepared to award any prize as the conditions of the match had not been fulfilled.” Deacon pointed out with indignant triumph that if this ruling became “case-law” it would always be in the power of one player to prevent his antagonist receiving the prize by resigning the match “even just before he had lost his seventh game”. This so staggered the Committee that they brought pressure to bear on Löwe, who was finally induced to play out the match, Deacon winning 7-2-1. Staunton in annotating the games admits that “the tedium of Mr Deacon’s play is quite insufferable, and although with him this arises from habit only, and not from a design to exhaust and irritate an opponent, the sooner he corrects so grave a fault the better.”’

According to Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), Frederic H. Deacon was born in Bruges in about 1829 and died, possibly in Brussels, circa October 1875. However, the privately-circulated 1994 edition gave his full name as Frederick Horace Deacon and stated that he was born in Bruges in about 1830 and died in Brixton, London on 20 November 1875. The additional sources specified by Gaige were the death certificate (reporting that Deacon died at the age of 45) and the probate record.

(7854)

From John Townsend:

‘In C.N. 7854 G.H. Diggle reported:

“In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) ‘rather than undergo the torture of another game’.”

Although the match score was level, the same cannot be said of the position on the board, since, at the time of his resignation, Staunton was a piece down in a completely lost endgame. On page 349 of The Chess Tournament (London, 1852) he made a curious remark in a note to his move 41...Kf7 in that game.

“It is clear that Black could have made a drawn battle if he chose, by

41...R to KR’s 8th

42 K to Kt’s 2nd, or 3rd 42 R to QKt’s 8th

43 B to QKt’s 2nd 43 K to B’s 2nd, etc.but it having been long quite evident that his opponent would protract the sitting until he (Black) could no longer support the fatigue (the present game lasted above 20 hours!), he preferred resigning the contest, although two games ahead, to undergoing the torture of another game.”

What exactly did Staunton mean by the last part of that remark? If he was suggesting that his inferior choice of 41...Kf7 was his way of capitulating, he omitted to explain why he played on for a further 38 moves. His eventual resignation, at move 79, was fully called for. He was, clearly, frustrated by Williams’ slow play, but here he seems to have confused that issue with the subject of his resignation and, hence, to have picked the wrong battlefield on which to attack Williams.

This was the return match after Williams had defeated him in the play-off for third place in the tournament. It was played at Staunton’s “country house” in Cheshunt, the exact location of which is not known. As he led by six wins to three before the 13th game but had given Williams the odds of three games’ start, the Badmaster was correct that the match score stood level. Staunton’s remark quoted above that he was two games ahead must be wrong, unless he meant that, after losing the 13th game, he remained two games ahead. Being two games ahead was useless, since Williams, by scoring his fourth win in the 13th game, reached the target of seven wins needed to secure the match, so for Staunton “undergoing the torture of another game” was no longer an option.’

(7858)

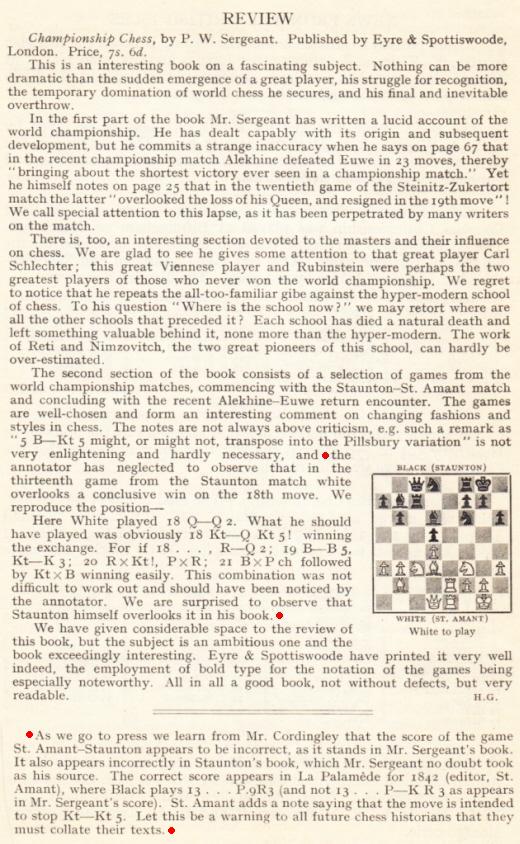

James Pelletier (Costa Mesa, CA, USA) refers to game 13 in the 1843 match in Paris between Saint-Amant and Staunton, which is commonly given in databases as follows:

1 d4 e6 2 c4 d5 3 e3 Nf6 4 Nc3 c5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 a3 Be7 7 Bd3 O-O 8 O-O b6 9 b3 Bb7 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Bb2 cxd4 12 exd4 Bd6 13 Re1