Edward Winter

W. Steinitz

C.N. 711 reported that after we complained to a columnist, James Pratt (Odiham, England), that he had published assertions about Torre taking his clothes off in a bus, Weaver W. Adams being addicted to bicarbonate of soda and Steinitz claiming that he could offer pawn odds to God, we received this reply, in a letter dated 8 February 1984:

‘You are probably correct that my anecdotes about Steinitz, Torre and Adams are untrue but I was writing purely to amuse myself. I would be very stupid if I spent hours and hours on an article, weeks on research before that, only to have it dismissed as 25% of my stuff is.’

See too pages 266-267 of Chess Explorations.

An extract from C.N. 891, concerning Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984):

In a sense we could repeat our comments on the Eales work (C.N. 878): Total Chess’s main attraction is that it is clear and sensible (whilst also conveying what might be labelled the ‘excitement’ of current chess). It too is less good on individuals than on tendencies – once again (page 146) poor old Wilhelm Steinitz is ridiculed for alleged hallucinations that Mr Spanier is happy to mention but would be unable to corroborate. The temptation to add piquancy and colour to chess books is so great that few authors can stop themselves from repeating ‘good’ stories, even if not a shred of evidence exists to support them. As noted before in this magazine, we deplore such a ‘masters are fair game’ attitude.

Louis Blair (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) sends a photocopy of an article by Paul Hofmann entitled ‘Launching my Fried Liver Attack’ on pages 129-140 of Smithsonian, July 1987. In the course of a discussion of his loss to Larsen in a simultaneous exhibition, the writer comments:

‘When the world champion Wilhelm Steinitz lost a match in 1896, he began to lose his mind, too. He believed that he could talk to people on an invisible telephone and waited around for it to ring. After he failed to make a comeback in an important tournament, he apparently claimed that, over his special telephone, he had beaten God at chess in spite of having generously given Him the advantage of the first move and the odds of a pawn.’

(1824)

This was on the next page (page 130):

Chess anecdotalists being carefree name-droppers, it is no surprise that ‘Steinitz versus God’ stories are regularly seen in all kinds of contradictory versions. C.N. 3100 quoted the statement by Peter Fuller on page 49 of The Champions (New York, 1977) that ‘Steinitz claimed to have played God at pawn odds and won’, and in C.N. 3101 we asked how far back, and in which different forms, the story could be traced. The following small sample was given from the output of some post-Second World War writers:

From page 114 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (1974):

‘According to one story, he claimed to be giving God odds of pawn and move.’

In Grandmasters of Chess (e.g. page 113 of the 1973 edition) Harold C. Schonberg affirmed:

‘He also tried to get in touch with God; he wanted to challenge the Deity to a match, offering Him odds of pawn and move.’

From page 42 of The Psychology of the Chess Player (1956/1967) by R. Fine:

‘One story says that he claimed to be in electrical communication with God, and that he could give God pawn and move.’

On page 9 of The Bright Side of Chess (1948) Irving Chernev wrote:

‘Confidence? Steinitz had enough of it to say once that he did not believe even God could give him pawn and move odds.’

The origins of the story remain to be traced, but Avital Pilpel (New York) now writes to us:

‘In his article in Time about Fischer entitled “Did Chess Make Him Crazy?” (http://www.time.com/time/columnist/krauthammer/article/0,9565,1054411,00.html) Charles Krauthammer follows the usual mode of such essays: start with an old anecdote about a master’s bizarre behavior; assume that chess caused this behavior; then speculate that chess causes insanity. In Krauthammer’s view, a “particularly fatal” and “unique” characteristic of chess is that it is “a playing field on which the other guy really is after you”. Imagine that. A board game where both players try to win ...

Krauthammer says that “Steinitz claimed to have played against God, given him an extra pawn and won”. This story has many forms. As C.N. 3101 notes, Fine’s version (in The Psychology of the Chess Player) has “[Steinitz] claimed to be in electrical communication with God, and that he could give God pawn and move”. Telegraphic or electrical communications feature in many versions of the tale. I suggest that what we have here are two unrelated stories that became crammed together.

In Steinitz’s day, the late nineteenth century, many – including leading scientists – speculated that the newly-discovered invisible substance, electricity, might at long last explain the supernatural: perhaps spirits, God, angels, etc. might be proven actually to exist, as electrical entities of some sort. If so, communicating with them by electrical means (such as the telegraph) might be possible.

If Steinitz had ever made similar claims (again, at the time, by no means evidence of mental illness), a later writer might mistakenly believe that both of Steinitz’s unrelated claims – about the possibility of communication with God by telegraph and about his possible result against God – referred to the same incident. He might conclude that Steinitz was speaking (on two different occasions) about the means and the result, respectively, of a game played with God.

But first things first: did Steinitz, in fact, show any interest in the paranormal in general, and in communicating with it by electrical means in particular?’

We shall welcome any relevant quotes, and for now we merely add that a lengthy article ‘Steinitz says he is not mad’ dated 23 March 1897 (our copy of which is in the third of Walter Penn Shipley’s scrapbooks – see page 45 of Chess Explorations) included the following:

‘He thought he could succeed in telephoning without any apparatus at all by mere force of will, and so he stood in the middle of a room and talked and sang loudly with the wish that such and such persons should hear him; and by degrees he imagined that he got answers, that those he addressed sang the chorus to his songs.’

For a slightly different wording see page 345 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion by K. Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993).

(3731)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to accounts in the New York Times of 21 May 1897 (page 4) and 14 August 1900 (page 5). In the first the newspaper reported that while Steinitz was in Russia ...

‘... someone presented him with a mechanical contrivance that looked like a silver snuffbox, and told him that it was a new invention in telephoning. If anyone spoke into a hole in the box the sound, he was told, would be transmitted to a wire, and could be heard at any distance.

This box, Mr Steinitz said, he took to his rooms and began experimenting, imagining that he had a wonderful invention which would bring him a fortune. His secretary told him his son in America could hear him. He was not feeling well at the time; his nerves were unstrung by his hard work at chess, and the statement of his secretary made him still more nervous. Later he was taken to an asylum on the representations of his secretary.

Mr Steinitz said he had made no definite plans for the future. He wants to rest and to see if he can get any redress for being sent to the asylum.’

The second item, the obituary of Steinitz, included the following:

‘... he would experiment with his wireless telephone. His theory was that he could use his willpower to convey words any distance. For hours he would stand in his room trying to “call up” various people he knew in Europe.

After he was tired of these experiments he would devote his time to writing his books.’

For further details (including the full text of the obituary) see pages 356 and 393-396 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion by K. Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993). The first reference to God in this connection is still being sought.

(3749)

See also pages 200 and 202 of The King by J.H. Donner (Alkmaar, 2006) or pages 216 and 218 of the hardback edition (Alkmaar, 1997).

Graced with some exceptionally rich archive material, Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World is disgraced with some exceptionally poor interviewees. A particular low point, with some of the talking heads less concerned about being truthful than noticed, is the dense sequence which seizes on the issue of insanity:

Anthony Saidy: ‘Victor Korchnoi claimed to have played a match with a dead man and he even provided the moves.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Rubinstein jumped out of the window because the fly was after him.’

Anthony Saidy: ‘Steinitz in late life thought he was playing chess by wireless with God Almighty – and had the better of God Almighty.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Carlos Torre took all his clothes off on a bus.’

To highlight only the Steinitz versus God yarn, no scrap of serious substantiation is available. Once again we witness the magnetic pull of malignant anecdotitis. And since the theme is insanity, an uncomfortable question arises: can such groundless public denigration of Steinitz and others be considered the conduct of a rational human being?

(7345)

Things That Matter by Charles Krauthammer (New York, 2013) has three brief chess articles, on pages 55-57, 102-104 and 108-111, but the only thing that apparently matters to him about the great masters of the past is using their lives as fodder for ‘fun’.

Page 104 (in an article reproduced from Time, 19 November 1990) has this remark, with the almost mandatory ‘once’:

‘The great Steinitz, who once claimed to have played against God and won (he neglected to leave a record of the game), went quite mad.’

There is nothing else about Steinitz, and the short paragraph moves on seamlessly to three or four lines about Fischer (dental fillings and the KGB).

(8461)

The matter of Steinitz versus God has even been mentioned in prominent reference book. Below is the final sentence of the brief entry on Steinitz on pages 1392-1393 of the Chambers Biographical Dictionary edited by Magnus Magnusson (Edinburgh, 1990):

‘He died, impoverished, in a New York mental asylum following an unsuccessful attempt to challenge God to a chess match.’

(8838)

From page 14 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘Overall, chessplayers are much less odd than is generally supposed. It is unfortunate that Fischer is such an extreme type; his unbalanced behaviour has inevitably encouraged journalistic muck-raking for other eccentricities amongst chess masters. I find the references to Steinitz and his statement that he could give God odds at chess particularly repugnant; Steinitz’s mind broke down when he was old, ill, unhappy and within a year of his death. It is as misleading as it is heartless to represent his conduct then as if it were his normal behaviour.’

(8920)

On page 143 of The Immortal Game (New York, 2006) David Shenk wrote regarding Steinitz:

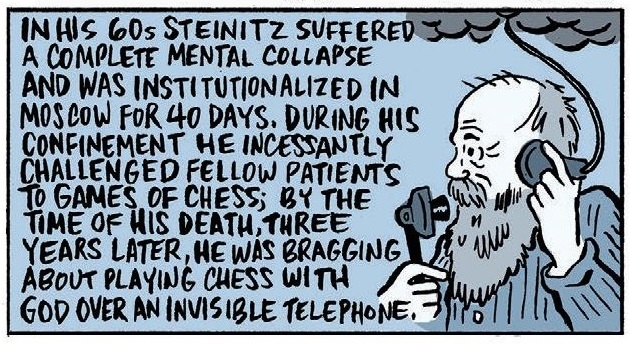

‘As years went by, he veered into a much more serious state of psychosis. For a time, he was confined to a Moscow asylum. He insisted that he had played chess with God over an invisible telephone wire. (God lost.)’

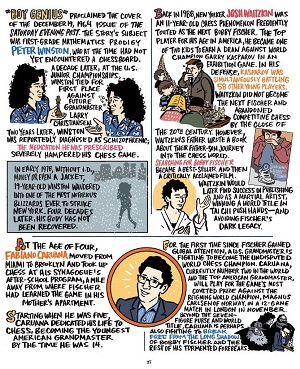

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to a cartoon feature on pages 26-27 of the November-December 2018 Playboy: ‘American Chess Masters’ written by Brin-Jonathan Butler and illustrated by Nathan Gelgud.

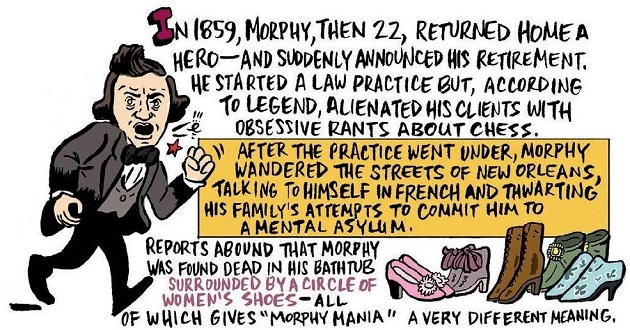

The left-hand section on Morphy refers to ‘a spooky child prodigy’ who later ‘traveled across Europe and toured royal courts ...’ Then comes this ‘Fun’:

The treatment of Steinitz does not even attain the ‘according to legend’ and ‘reports abound that’ level:

(11086)

See too page 109 of The Psychology of Chess by Fernand Gobet (Abingdon, 2019).

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.