Edward Winter

(2003, with updates)

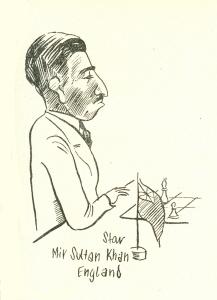

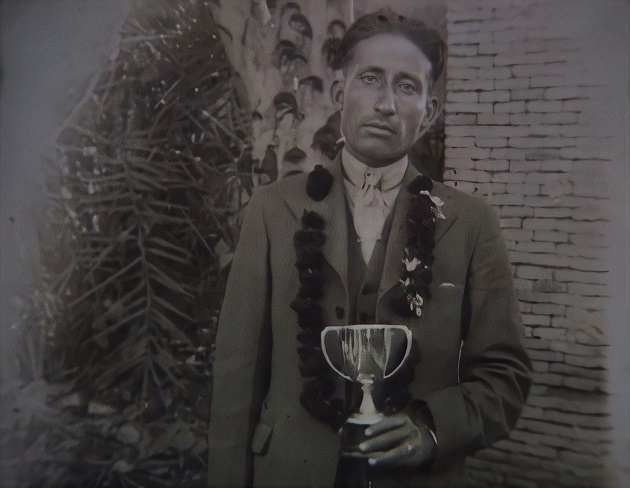

A portrait given in C.N. 6529, courtesy of Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark)

A comment about Sultan Khan by Gerald Abrahams on page 223 of the August 1952 BCM:

‘An obscure Indian from a Punjab village held his own with the best players in Europe without ever making a surprising move.’

(2616)

In the light of these descriptions, we have been looking back at some earlier comments on Sultan Khan, beginning with page 338 of the September 1929 BCM:

‘The Nawab Umar Hayat Khan, though occupied with official duties in Whitehall, paid three visits to the Congress [the British Championship at Ramsgate], and showed great interest in the doings of the champion, who, owing to his unfamiliarity with the language and the tournament procedure, was also indebted to his companion interpreter, Syed Akbar Shah. The latter nursed him during his illness, kept him posted with information, and was often to be seen translating press reports to him.’

Next, an account by Harry Golombek on page 175 of the June 1966 BCM. (The item was purportedly a review of the first edition of Coles’ Mir Sultan Khan, but the book was barely mentioned.)

‘I first met Sultan Khan when he was competing in his first British Championship at Ramsgate in 1929. Not that we were in the same tournament or anything like it. He was some six years older than me and far in advance of a schoolboy who was competing in his first open tournament (to be precise, the second-class). However, only recently arrived in England he was in search of a type of cooking not too far away from his Indian variety and thus it happened that he and I were the only chessplayers at a Jewish boarding house where, I still remember it, the cooking was indeed infinitely better than anything offered by the smarter hotels of the resort.

Despite the fact that he had little English we got on very well together, particularly over the chess board after the day’s play. Though so much younger than him I was more or less able to hold my own in analysis since I was London Boy Champion and had a very quick sight of the board. For this reason, later on, when we did meet in tournaments, he treated me with care and a sort of respect that he did not exactly vouchsafe to players who were by reputation my superior.’

Also in 1966 a more detailed piece by Golombek was published on pages 61-65 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966). Two passages are quoted here:

‘When he first came to Europe, in the early summer of 1929, Sultan Khan could neither read nor write a European language. The few scraps of knowledge he had about the openings had been picked up by watching other Indian players who were able to read English, and his style of play was greatly influenced by the other form of the game.’

‘… It so happened however that I stayed at the same boarding house as Sultan Khan, and that we were the only two chessplayers there. Considering the language barrier we understood each other remarkably well, partly by signs and partly by the use of chess pieces and the chess board. For anything complicated I had recourse to his friend and interpreter, whose excellent English more or less compensated for his utter ignorance of chess. Sultan Khan, I discovered, was totally uneducated, rather lazy, and blest, or cursed, with a childish sense of humour that manifested itself in a high-pitched laugh. He loved to play quick games but, strange to relate, match and tournament chess were a trial to him.’

Notwithstanding the various allegations that Sultan Khan was completely illiterate (as opposed to merely unfamiliar with any European languages) we note, without drawing any conclusions, that in the group picture of the masters in the Berne, 1932 tournament book he appeared engrossed in a document:

Berne, 1932. From the

back row and from left to right:

W. Rivier, O. Naegeli, P. Johner, B. Colin, H. Grob

F. Gygli, H. Johner, O. Bernstein, A. Staehelin, E. Voellmy

M. Euwe, Sultan Khan, A. Alekhine, W. Henneberger

E. Bogoljubow, S. Flohr

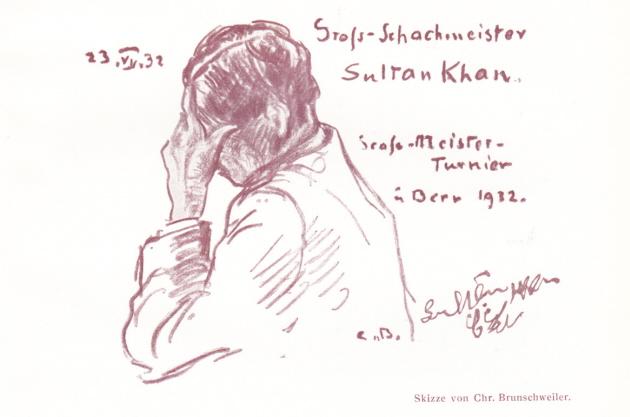

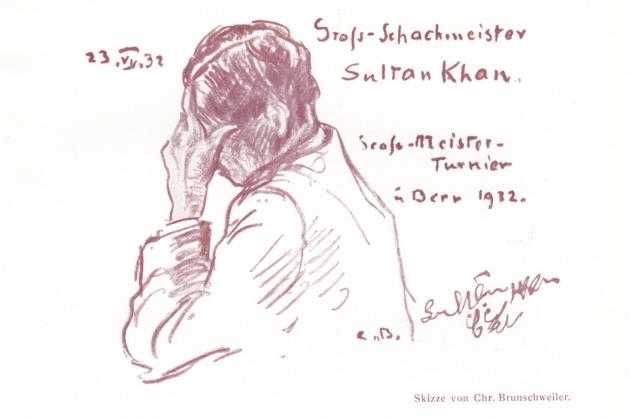

Below is a sketch also from the Berne, 1932 tournament book:

Biographical accounts seldom refer to Sultan Khan’s later life, but below are two reports from the 1950s. The first was on page 250 of the August 1954 BCM:

‘Pakistan. It is good news indeed to hear that the great player Sultan Khan, who made such a mark in European chess during the brief space of four years before the war, is still alive and apparently interested in chess. According to a report a tournament is being held in Pakistan to select four players to meet him in a final tournament. One hopes that this is merely the prelude to the return of so greatly gifted a master to the international arena.’

On what basis the above claim was made is unclear.

Savielly Tartakower and Sultan Khan, match, Semmering, 1931

The second report about Sultan Khan is taken from CHESS, 19 December 1959 (page 93) and concerned an apparent mix-up in South Africa with a musician of the same name:

‘The South African Chessplayer prints an extraordinary report about Sultan Khan, the Indian serf who won the British Championship in three out of four attempts and defeated Tartakower in a match, then vanished back to India and has not been heard of in chess for over a quarter of a century. Kurt Dreyer states that Sultan Khan is living in Durban and is a professional concert singer, “has not played chess for a long time”.

Pending confirmation, we take this report cum grano salis.’

Under the heading ‘Sultan Khan is not in South Africa’ the 20 February 1960 CHESS (page 154) published a letter from Mohammed Yusuf of Lahore, West Pakistan:

‘The unconfirmed report on Sultan Khan appearing in CHESS No. 354 is amusing.

I have known Sultan Khan since 1918. He is settled as a small land-lord in the Sargodha District of the old Punjab. The reason for his disappearance from the chess world is that his patron, the late Malik Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana, died in 1941 [sic; in 1944, in fact]. Since then there has been no great opportunity for players scattered all over the country to meet. Furthermore it is well known that Sultan Khan’s knowledge of English does not go beyond his ability just to read a game-score. The secretary of the late Sir Umar used to help him to a certain extent to study annotations. Now he has nobody to help him or to give him practice. Even now he is distinctly better than the best active player in Pakistan or even in India I believe. He is a genius.’

Sultan Khan

It may be mentioned in passing that ‘Malik’ is sometimes also seen with reference to Sultan Khan himself. For example Schonberg (page 212 of his above-mentioned book) referred to ‘Mir Malik Sultan Khan’.

Then there is the following paragraph about Sultan Khan on page 215 of The Guinness Book of Chess Grandmasters by W. Hartston (Enfield, 1996):

‘Eighteen years later, however, [i.e. in 1951] when he was shown the moves of the games in the world championship match between Botvinnik and Bronstein, he is reputed to have dismissed them as the games of two very weak players.’

The source of this reputed dismissal is unknown to us, but as noted on page 378 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves Sultan Khan has been quoted as making such a remark about Alekhine and Bogoljubow. We quote below from William Winter’s memoirs in CHESS, February 1963, page 148:

‘I remember vividly my first meeting with the dark-skinned man who spoke very little English and answered remarks that he did not understand with a sweet and gentle smile. One of the Alekhine v Bogoljubow matches was in [a] progress and I showed him a short game, without telling him the contestants. “I tink”, he said, “that they both very weak players.” This was not conceit on his part. The vigorous style of the world championship contenders leading to rapid contact and a quick decision in the middle game was quite foreign to his conception of the Indian game in which the pawn moves only one square at a time.’

On the following page of CHESS another incident was related by William Winter:

‘At the Team Tournament at Hamburg (1930) he also did extremely well on the top board against the best continental opposition though his apparent lack of any intelligible language annoyed some rivals. “What language does your champion speak?”, shouted the Austrian, Kmoch, after his third offer of a draw had been met only with Sultan’s gentle smile. “Chess”, I replied, and so it proved, for in a few moves the Austrian champion had to resign.’

The problem with this story is that the game between Sultan Khan and Kmoch was drawn.

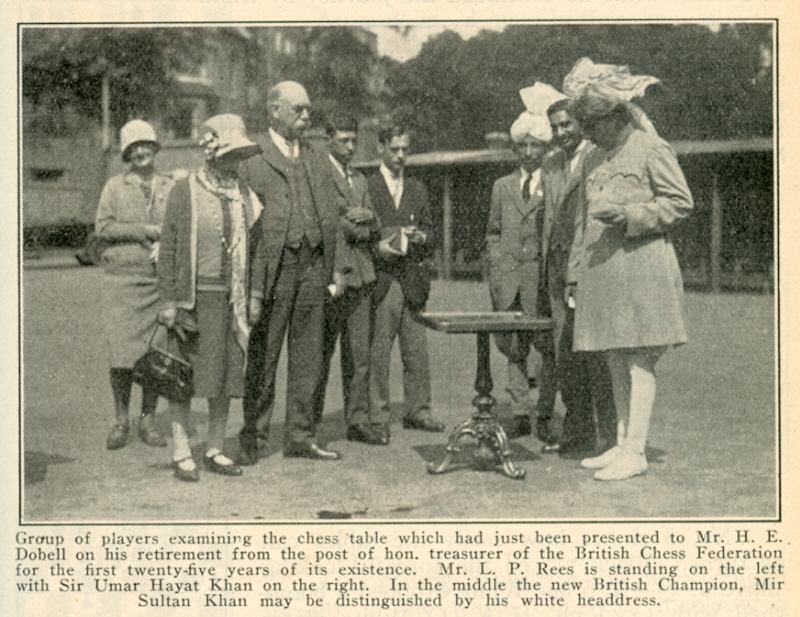

Ramsgate, 1929. From page 345 of the September 1929 BCM.

Readers interested in Sultan Khan will wish to note the publication of the 254-page work, Kometa Sultan-Khana by A. Matsukevich (Moscow, 2003).

(2912)

C.N. 2912 quoted another passage from William Winter’s memoirs, on page 149 of CHESS, 23 February 1963. It concerned Sultan Khan:

‘At the Team Tournament at Hamburg (1930) he also did extremely well on the top board against the best continental opposition though his apparent lack of any intelligible language annoyed some rivals. “What language does your champion speak?”, shouted the Austrian, Kmoch, after his third offer of a draw had been met only with Sultan’s gentle smile. “Chess”, I replied, and so it proved, for in a few moves the Austrian champion had to resign.’

In C.N. 2912 we observed: ‘The problem with this story is that the game between Sultan Khan and Kmoch was drawn.’

Kmoch himself rebutted the anecdote in a letter published on page 245 of CHESS, 25 May 1963:

‘Not that it matters, nor that I would cast any blame on the late Winter, whom I knew as a perfect gentleman. It is only for the sake of curiosity that I ask permission to comment on Winter’s story concerning my game against Sultan Khan.

I never asked Winter or anybody else what language Sultan Khan spoke. Nor did I shout (I never do). Sultan Khan and I had met before. What little conversation there was between us was done in English, of which we both had a command sufficient for the purpose.

Winter, being not asked, had no opportunity to reply “Chess” or anything else.

I did not offer a draw three times, nor did Sultan Khan, who never smiled, meet my offers with a smile. Nor again did I resign a few moves later. And I was not the Austrian champion (contests have not been held at all in my active time).

Sultan Khan had White; we played a Giuoco Piano. After a small number of moves, probably 18 or so, a position was reached which I considered as fully satisfactory for Black.

I offered a draw so as to gain time for my work as a reporter. (I used to be very strict in never offering a draw to anybody unless my position, to the best of my understanding, was fully satisfactory.)

Sultan Khan accepted my offer outright. The game’s ending in a draw is a provable fact.’

(3960)

Dan Scoones (Victoria, BC, Canada) draws attention to this passage from pages 24-25 of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958):

‘The story of the Indian Sultan Khan turned out to be a most unusual one. The “Sultan” was not the term of status that we supposed it to be; it was merely a first name. In fact, Sultan Khan was actually a kind of serf on the estate of a maharajah when his chess genius was discovered. He spoke English poorly, and kept score in Hindustani. It was said that he could not even read the European notations.

After the tournament [the 1933 Folkestone Olympiad] the American team was invited to the home of Sultan Khan’s master in London. When we were ushered in we were greeted by the maharajah with the remark, “It is an honor for you to be here; ordinarily I converse only with my greyhounds.” Although he was a Mohammedan, the maharajah had been granted special permission to drink intoxicating beverages, and he made liberal use of this dispensation. He presented us with a four-page printed biography telling of his life and exploits; so far as we could see his greatest achievement was to have been born a maharajah. In the meantime Sultan Khan, who was our real entrée to his presence, was treated as a servant by the maharajah (which in fact he was according to Indian law), and we found ourselves in the peculiar position of being waited on at table by a chess grand master.’

Finding corroboration of Fine’s account may not be easy, but certainly the US team went to London after the Olympiad. We quote below from page 320 of the Social Chess Quarterly, October 1933:

‘Before their departure from England the victorious American team visited the [Empire Social Chess Club in London], and the youngest member, R. Fine, who is only 18 years old, gave a very successful simultaneous display on 20 boards. Playing almost with lightning rapidity, the young American won 17 games and drew three in a little less than two hours …’

Below is an extract from the section on Sultan Khan in Fine’s book The World’s Great Chess Games (first published in the early 1950s):

‘The appearance of an Indian on the tournament scene was one of the sensations of the early 1930’s. Sultan (a first name, not a title) was a serf on the estate of an Indian Maharajah, who was impressed by his extraordinary ability at chess. His master took him to England, where Sultan Khan had to learn the European rules, which were not adhered to in India. In spite of this handicap, his native genius was such that he soon became British champion …’

See also, in this context, page 51 of The Chess Beat by Larry Evans (published in 1982) and Chess Life, February 2002, page 32.

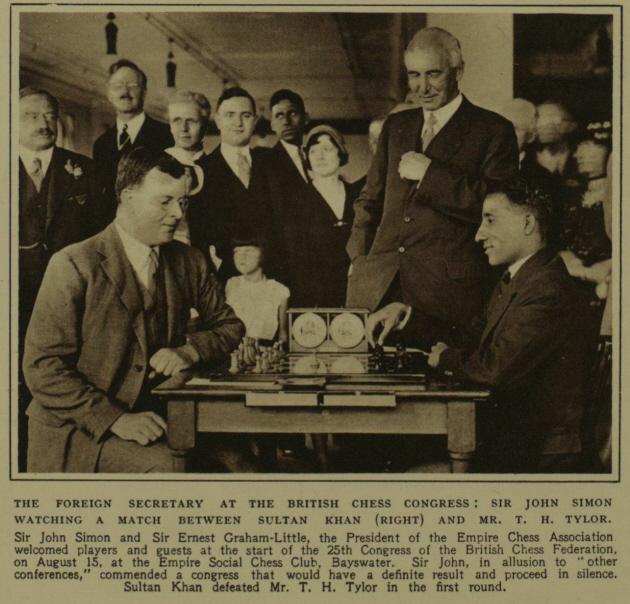

For comments about Sultan Khan by Sir John Simon, together with a photograph of them together, see our feature article A Chessplaying Statesman.

From the report on page 64 of the February 1931 BCM, regarding the Hastings, 1930-31 tournament (at which Capablanca lost to Sultan Khan):

‘A “movietone” was taken of the proceedings one morning, but Capablanca was not “in the picture”. A good joke was provided by the wife of one of the chess correspondents, who wrote to her husband thus: “I have been reading the chess reports (not her husband’s, by the way) and I notice that the Aga Khan has beaten Capablanca.” Nobody enjoyed this one more than Capablanca.’

(Kingpin, 2000)

A group photograph, from the 1929 British Championship in Ramsgate, is added here, gleaned from page 162 of the September-October 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

Left to right, standing: W.H.M.

Kirk, W. Winter, J.A.J. Drewitt, Rev. F.E. Hamond, T.H. Tylor,

R.P. Michell, J.H. Morrison

Seated: A. Eva, H.E. Price, M. Sultan Khan, G. Abrahams, W.A.

Fairhurst

(4059)

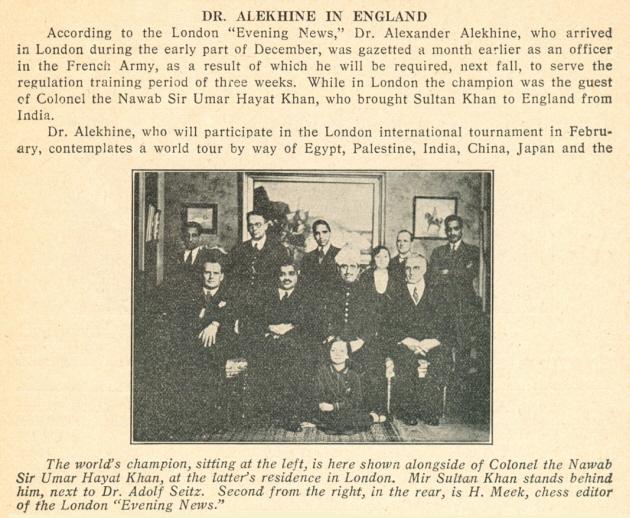

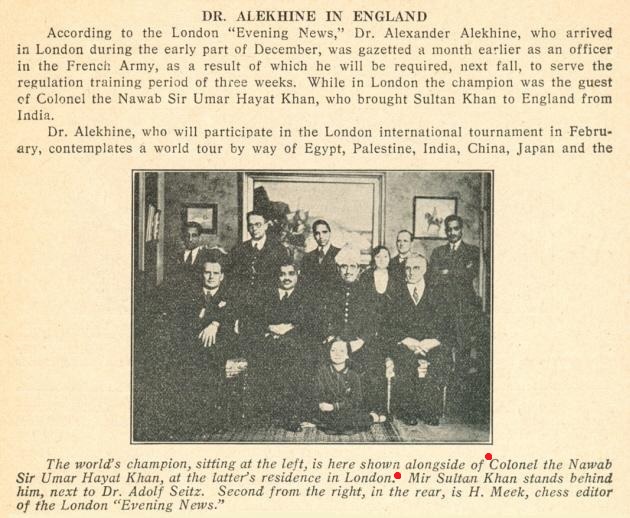

Centre background: Colonel Nawab

Sir Umar Hayat Khan

Back row (left to right): C.D. Locock, R.H.S. Stevenson, P.W.

Sergeant, C. Wreford Brown, Sir Ernest Graham-Little, M.P., R.C.

Griffith, F.D. Yates, J. du Mont, A. Rutherford, J.B. Whieldon

Next row: Miss Joseph, Mrs Latham, Mrs Arthur Rawson, V.

Menchik, A. Alekhine, Mrs Stevenson, J.A. Seitz.

Foreground: S. Basalvi, Aziz, Mir Sultan Khan.

The photograph came from the February 1932 BCM, and the magazine’s key has been given. Page 71 explained the occasion:

‘Colonel Sir Umar Hayat Khan arranged one or two receptions at his residence in honour of Dr Alekhine, the champion of the world. On each evening a dinner followed, characterized by all Sir Umar’s well-known hospitality. On 15 December after full justice had been done to the repast, speeches were made by Sir Ernest Graham-Little, MP, J. Whieldon, C. Wreford Brown and R.C. Griffith; Miss Vera Menchik and Dr Alekhine himself responded to the good wishes and thanks accorded them by the company.

The group photo we give as frontispiece was taken by Malik Ghulam Mohammed Khan, one of the most trusty of Sir Umar’s entourage and a warrior of great distinction. The small photo hanging on the wall to the right of the mirror (behind R.C. Griffith and F.D. Yates) shows Sir Umar in his official robes as Herald of the Princes at the great Durbar.’

(5602)

Steven Pla (Albuquerque, NM, USA) asks whether any of the master’s game-scores at ‘old chess’ (shatranj) are extant.

We recall none. It may be noted, though, that page 268 of The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants by David Pritchard (Godalming, 1994) gave the moves of a game of shatranj between Herbert Jacobs and George Thomas at the City of London Chess Club in 1914. Did either player contest games of shatranj against Sultan Khan during the latter’s brief period in Europe (1929-33)?

(5645)

This photograph (Sultan Khan v R.P. Michell, Hastings, 29 December 1930) was given in C.N. 6038, from page 116 of Le miroir du monde, 24 January 1931. Acknowledgement: Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium).

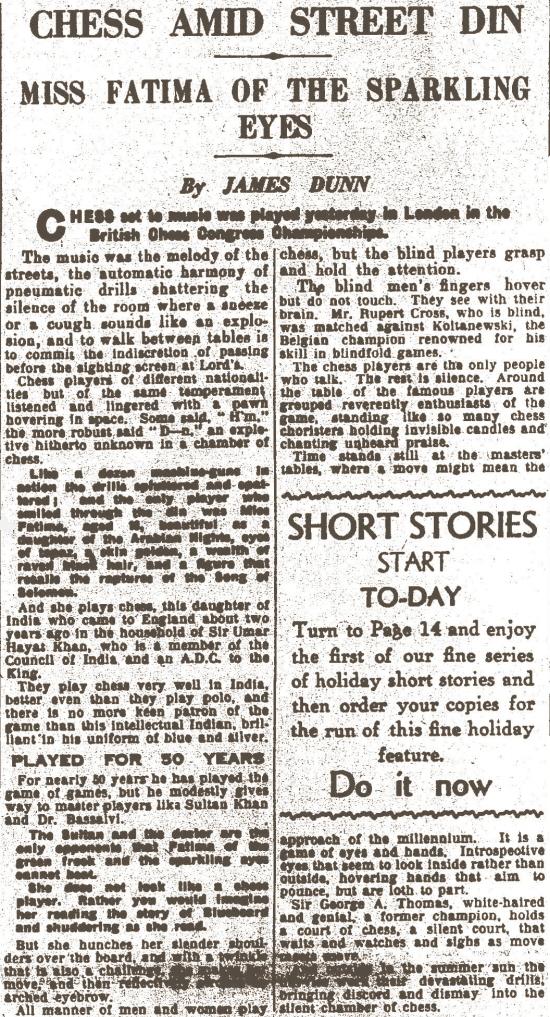

For the book on Indian chess history mentioned in C.N. 6152 Manuel Aaron (Chennai, India) would like information on Miss Fatima, who won the 1933 British Ladies’ Championship in Hastings by a margin of three points.

We raised the subject in C.N. 14, but even basic biographical details about her are still lacking. She had also participated in the previous year’s championship, finishing sixth, and page 381 of the September 1932 BCM reported:

‘... additional interest was imparted by the entry of Miss Fatima, from India, who has had the advantage of some instruction from Sultan Khan and other chessplayers on Sir Umar Hayat Khan’s staff.’

The following passage appeared on page 424 of the October 1932 issue:

‘Miss Fatima made a very good first appearance in the event. She is only 18, has never played in a tournament before, and very little in public at all. The experience should give her confidence; and she has been well taught.’

Page 375 of the September 1933 BCM commented:

‘Miss Fatima was clearly the strongest and cleverest, as the fact of her being able to recover from quite a number of “lost” positions showed. She has had coaching from Miss Menchik, while Dr Bassalvi also has given her a good deal of practice. There is only room to give a specimen of her capital end-play.’

The position was from her win as White against Mrs Stevenson:

30...Rg8 31 Rxg8 Qxg8 32 Qd4 Qd8 33 Qd6+ Qxd6 34 exd6+ Kd7 35 Bc4 b5 36 Bb3 Ke8 37 Kd2 Kf7 38 Kc3 Kf6 39 Kd4 Bd7 40 Bd1 Be8 41 h4 Bf7

42 d7 Ke7 43 Ke5 Kxd7 44 Kf6 Be8 45 Bb3 Kc7 46 Bxe6 and wins.

Miss Fatima was interviewed about Sultan Khan in the Bandung Limited television production The Sultan of Chess broadcast by Channel 4 in the United Kingdom on 19 September 1990. She mentioned that she had given some chess instruction to Queen Mary, the wife of George V.

(6201)

Addition on 14 June 2021:

Olimpiu G. Urcan has sent us this screen-shot (occasion unknown) from the above film:

See too G.H. Diggle, the Chess Badmaster.

Two games won by Miss Fatima were given in C.N. 6208.

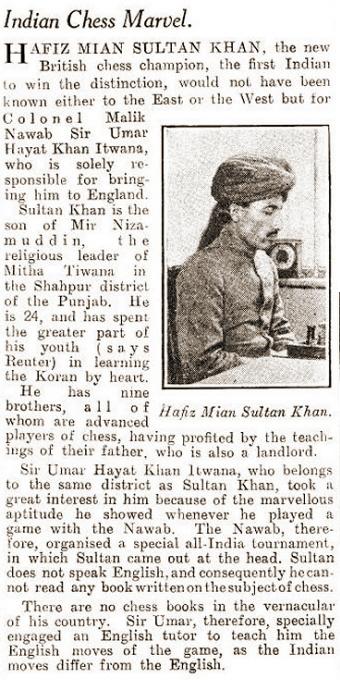

Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England) sends a report on page 8 of the Daily News (London), 12 August 1929 headed ‘The new chess champion’:

‘Hafiz Mian Sultan Khan, the new British chess champion, the first Indian to achieve this distinction, was “discovered” by Colonel Malik Nawab Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana, who is solely responsible for bringing him to England.

Sultan Khan, who is 24, is the son of a religious leader in the Punjab. He has nine brothers, all advanced chessplayers, having profited by the teachings of their father. Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana took a great interest in Sultan Khan because of the marvellous aptitude he showed, and organized a special All-India Tournament, in which Sultan came out at the head. Sultan does not speak English, and cannot read any book on chess, so Sir Umar engaged an English tutor to teach Sultan the English moves of the game.’

Our correspondent asks if Sultan Khan’s exact date of birth is known. The best reference that we can cite is from H. Meek on page 337 of the September 1929 BCM:

‘Concerning the career of the new champion, I am indebted to his friend, Syed Akbar Shah, for the following information.

M. Sultan Khan was born in 1905 in the village of Mittha Tawana in the Sirgoodha district of the Punjab. He learnt the game [Indian chess] at the early age of nine from his father, who was a very strong player.’

(6234)

Nick Pinkerton (Bracknell, England) sends a report from page 12 of the Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 12 August 1933:

‘History was made at Hastings Chess Club this week when the British Chess Championship and the British Women’s Championship were each won by Indian competitors.

Mir Sultan Khan secured the men’s championship, which he gained last year and previously, and the women’s championship was won by the young Indian lady player, Miss Fatima, who held an unbeaten record throughout the contest.

This remarkable victory of East over West makes memorable the first British championship contest to be held in Hastings since 1904.

Miss Fatima is a young and charming devotee of the game. She speaks little English and is very modest about her success. She is the first of her countrywomen to win the women’s championship.

There was a picturesque gathering in the tournament room yesterday (Friday) morning when Sir Umar Khan, who introduced both Sultan Khan and Miss Fatima, paid a visit to the club. He was accompanied by Indian friends, and the party wore Indian costume.

Sir Umar is adviser on Indian affairs to the British Government and Aide-de-Camp to His Majesty the King. The whole of his extensive staff are keen chessplayers ...

Miss Fatima was a radiant figure in a robe and veil of bright red, bound to her dusky hair with golden bands.’

Our correspondent seeks further information about Miss Fatima, including her background and later life. We have a few newspaper cuttings from the 1930s to give shortly, but nothing about her later life beyond what is indexed in the Factfinder.

(9077)

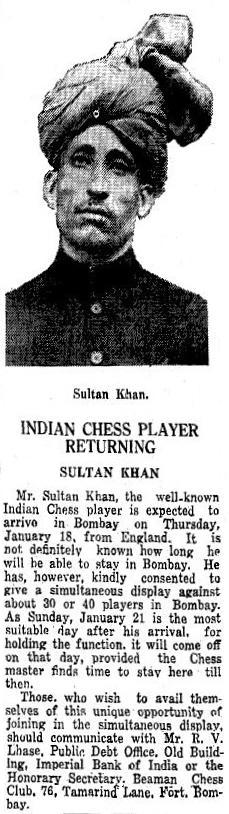

From page 5 of the January 1932 American Chess Bulletin:

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found this photograph on page 5 of The Times of India, 16 January 1934:

The caption reads: ‘Colonel Sir Umar Hyat Khan bidding farewell to Miss Fatima and Sultan Khan, the Indian Chess champions, when the[y] left London for Tilbury, on their return to India.’

(7168)

Addition on 16 October 2011:

Olimpiu G. Urcan draws attention to a number of photographs available courtesy of Getty Images:

Sultan Khan in 1929

The Sultan Khan v Alexander photograph was discussed in C.N.s 6277 and 6285, as shown in our feature article on C.H.O’D. Alexander. On 8 January 2025 we received permission to show the following version:

From page 184 of the June 1930 BCM:

The picture is the above-mentioned ‘group photograph of team match, 1930’.

(11171)

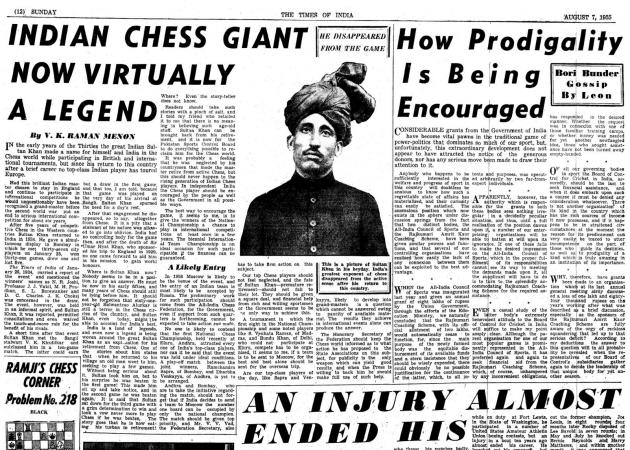

Also from Mr Urcan comes an article on page 12 of The Times of India, 7 August 1955:

Our correspondent has noted that the same photograph was used on page 12 of the 15 January 1934 issue of the newspaper:

(7329)

Olimpiu G. Urcan has submitted the following photographs from the Illustrated London News:

17 August 1929, page 293

20 August 1932, page 264

Sultan Khan with the British championship trophy. 3 September 1932, page 332

(7490)

For photographs of Sir Umar Hayat Khan see C.N. 7511.

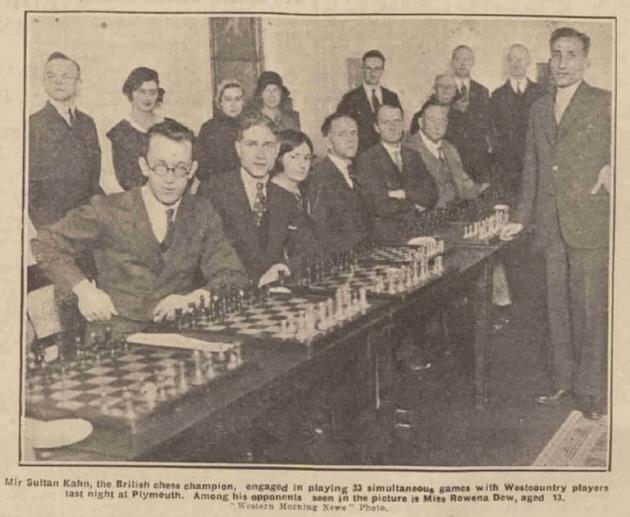

Olimpiu G. Urcan sends a detailed report about Sultan Khan’s visit to Plymouth, which accompanied the above photograph, on page 5 of the Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 27 October 1932.

(7993)

With regard to the alleged illiteracy of Sultan Khan, George L. Gretton (Edinburgh) suggests that the sketch reproduced from the Berne,1932 tournament book appears to have the master’s signature, using the Latin alphabet:

(8061)

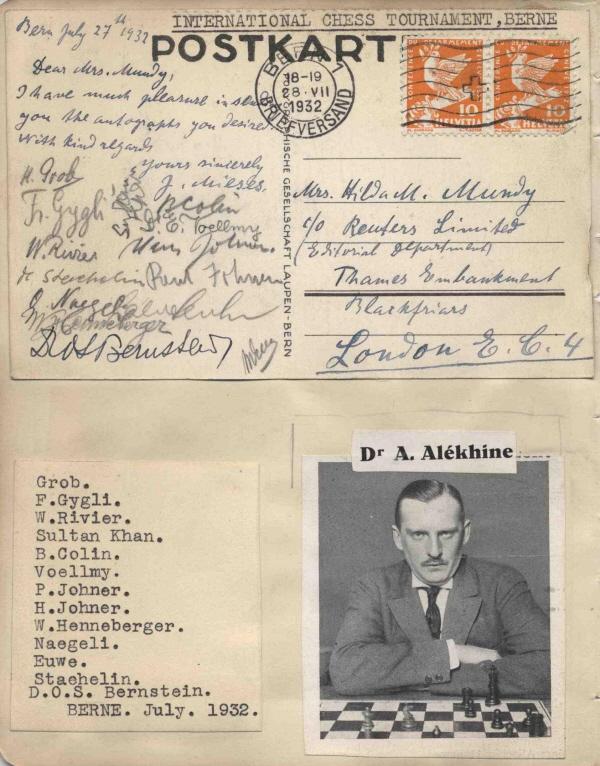

Rudy Bloemhard (Apeldoorn, the Netherlands) owns a postcard (Berne, 1932) with the same signature of Sultan Khan:

(8065)

Mr Bloemhard has now posted the card on his website, with all the signatures identified individually.

(8081)

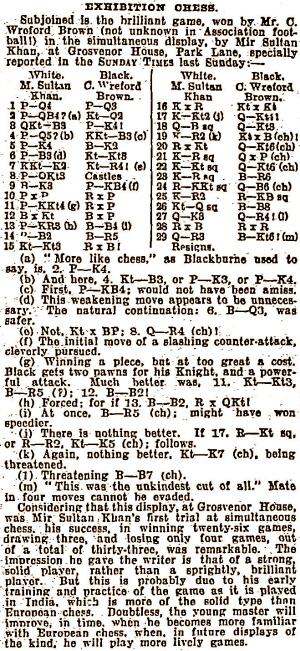

Olimpiu G. Urcan sends this report by Louis van Vliet in the Sunday Times, 29 September 1929, page 21:

Our correspondent also provides a game-score from page 4 of the newspaper’s 6 October 1929 edition:

Sultan Khan – Charles Wreford Brown

London, 28 September 1929

Old Indian Defence

1 d4 d6 2 c4 Nd7 3 Nc3 e5 4 d5 Ngf6 5 e4 Be7 6 f3 Nb6 7 Nge2 Nh5 8 b3 O-O 9 Be3 f5 10 exf5

10...Rxf5 11 g4 Rxf3 12 Bxb6 Bxg4 13 h3 Bf5 14 Bf2 Bh4 15 Ng3 Rxf2 16 Kxf2 Nxg3 17 Kg2 Qg5 18 Qc1 Qg6 19 Kh2 Nxf1+ 20 Rxf1 Qg3+ 21 Kh1 Qxh3+ 22 Kg1 Qg3+ 23 Kh1

23...Bh3 24 Rg1 Qf3+ 25 Kh2 Rf8 26 Nd1 Bf1 27 Qe3 Qh5 28 Rxf1 Rxf1 29 Qh3 Bg3+ 30 White resigns.

The display, organized by Mrs Arthur Rawson of the Imperial Chess Club, was also reported on page 422 of the November 1929 BCM and on page 27 of the November 1929 Chess Amateur.

(8190)

Olimpiu G. Urcan has forwarded a number of chess items published in the Daily Mail in the 1920s and 1930s, including the following:

Daily Mail, 28 September 1929, page 5

Daily Mail, 17 August 1932, page 5

Daily Mail, 11 August 1933, page 7

(8193)

From page 265 of the September 1929 Chess Amateur:

‘BCF Ramsgate Congress

The British Amateur Championship was won by Malik Sultan Khan, a young Indian gentleman of good family, 23 years of age, who holds the Indian Championship.’

Our feature article has mentioned that he was sometimes referred to as ‘Malik Sultan Khan’ or ‘Mir Malik Sultan Khan’. In Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) by Jeremy Gaige the entry was headed ‘Sultan Khan, Mir (Malik?)’, and clarification is still sought.

(8670)

The above-mentioned report that Sultan Khan was living in Durban also appeared on page 134 of the May 1960 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s ‘Quotes and Queries’ column. He published a retraction on page 200 of the July 1960 issue.

Two photographs in the present article (given courtesy of Messrs Lysdal and Urcan) were reproduced in ‘The Indian Summers of Mir Sultan Khan’ by John Henderson (CHESS, July 2016, pages 30-32). No source was specified.

There is also an Alchetron page which helps itself to various illustrations from our Sultan Khan article. That makes it convenient for the chessgames.com page on him to be illustrated as follows:

R.N. Coles sent us the following autobiographical note in a letter dated 4 April 1979:

(10455)

The first 45 pages of The Indian Chessmaster Malik Mir Sultan Khan by Ulrich Geilmann (Eltmann, 2018) have over a dozen illustrations of the master. Nearly all of them have been lifted, without permission or acknowledgement, from our feature article on Sultan Khan.

(10939)

Page 12 of Tidskrift för Schack, January 1934:

Acknowledgement for the above scan: the Cleveland Public Library.

The mirror image presented by the Swedish magazine is amended below:

The smaller picture ...

... may be compared with a photograph which we have given previously from page 5 of the American Chess Bulletin, January 1932:

(11339)

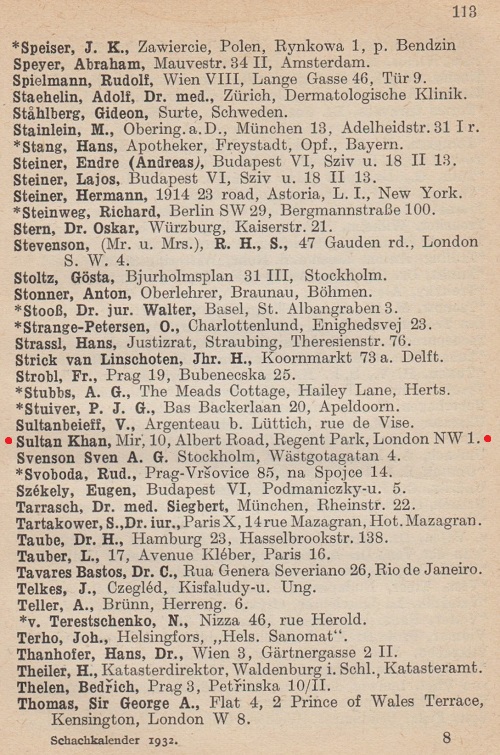

Sébastien Moig (Villiers-Adam, France) refers to this feature (American Chess Bulletin, January 1932, page 5) and asks about the location of Sir Umar Hayat Khan’s residence in London:

Rahmat Ali by Khursheed Kamal Aziz (Wiesbaden, 1987) has several references of relevance, including the following on page 209:

‘10 Albert Road, Regent’s Park (residence of Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana).’

That address (today: 10 Prince Albert Road) is in the entry for Sultan Khan in Where Did They Live?, on the basis of page 113 of Ranneforths Schachkalender, 1932:

(11501)

Addition on 17 April 2020: The latest monograph is Sultan Khan The Indian Servant Who Became Chess Champion of the British Empire by Daniel King (Alkmaar, 2020).

Addition on 11 July 2020: Olimpiu G. Urcan has forwarded this photograph from page 40 of the Sunday Pictorial, 12 November 1933:

Addition on 24 September 2021:

Olimpiu G. Urcan forwards these two portraits of Miss Fatima from the Edwin Smith photographic archive:

See too Two Indian Chess Figures.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.