Edward Winter

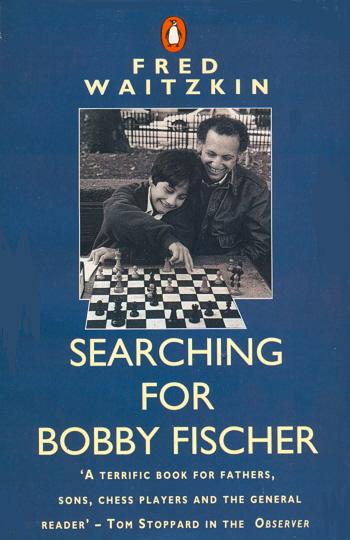

When a literary figure as eminent as Tom Stoppard calls a chess book ‘well written’ and ‘captivating’ (The Observer, 2 April 1989, page 45) there is little room for argument. And when an ex-prodigy such as Nigel Short praises that same book for its realism and honesty (The Spectator, 8 April 1989, pages 30-31) the matter must be considered settled. Sure enough, Fred Waitzkin’s Searching for Bobby Fischer (Random House and Bodley Head) is an enchantingly truthful account of the career of his young chess-playing son Josh.

Waitzkin Senior clinically dissects his own and other people’s actions, quirks and motivations. ‘It’s an odd position for a father to be caddy and coach for his three-and-a-half foot, sitting, brooding, son’, he writes on page 4. His own interest in chess resulted from the ‘Fischer explosion’ of the early 1970s, and he started playing in Greenwich Village: ‘On that first occasion, I played against a pimply adolescent who after 20 minutes caught on to my methodical bob-and-weave style and began to read a newspaper’ – page 13. Young Josh takes lessons from Bruce Pandolfini, an appreciated coach but, on the personal front, reliable only for his unreliability, and F.W. faithfully relates the pleasures and frustrations of life on the chess circuit. He reports many insiders’ remarks, such as the one of an international master obliged to support himself by taking on menial jobs: ‘I can’t make a living from chess, but I’ve devoted so much time to the game that I have no other marketable skill’ (page 16). From page 58: ‘Professional players in the United States are bitter about their poverty and lack of recognition, but they don’t do much to improve their image. Failure seems to beget more failure. Even at the best tournaments the players are a ragtag group, sweaty, gloomy, badly dressed, gulping down fast food, defeated in some fundamental way.’

The first UK edition

As the chess skill of Josh, a delightful child, develops, he is taken to the Soviet Union by his father and Pandolfini during the first Karpov-Kasparov match. The account is forceful and chilling (‘The all-night bars at the Cosmos are captained by heavy-lidded men who speak liquor and money in a dozen languages’ – page 69). Josh made a considerable impression on Soviet television viewers, and ‘during one interview he demonstrated a winning line for Kasparov with bubble gum all over his chin’ (page 76). Nor do the vagaries of chess journalists escape Fred Waitzkin:

‘Dimitrije Bjelica was a dynamo, turning out articles in different languages for various papers. Like a track star he raced from phone to phone, belting out stories. “I never write a thing; there’s no time”, he said. One afternoon while he took a frantic break, I mentioned some piece of gossip about Bobby Fischer. The following morning the story was printed in two different newspapers.’ (page 78)

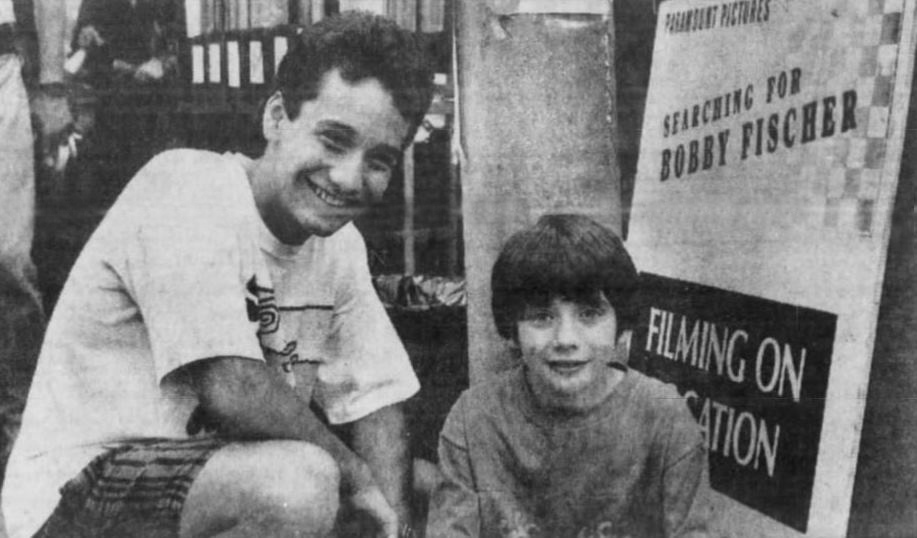

The Penguin edition, featuring the actor Max Pomeranc

Family life is not easy, and the author’s wife ‘often chides me for thinking more about the chessplayer than the boy, and I nod sheepishly; I am guilty of this crime. It is hard for me to remember Josh before he was a chessplayer. It’s terrible, but when he wins or plays brilliantly my affection for him gushes. After he plays badly, I notice that I don’t walk as close to him on the street, and I have to force myself to give him a hug’ (pages 123-124). An equally disarming remark by another chess parent is recorded on page 163: ‘I don’t mind spending all my free time on Morgan’s chess. He has more talent for chess than I have for anything I do.’

This book contains so much else. Relations between coach, pupil and family, tournament nerves and, above all, the constant fretting about whether it is all worthwhile; these are just some of the topics treated with an acuity and grace that offer the reviewer something quotable on almost every page.

An inscription by Josh Waitzkin in his 1995 book Attacking Chess

Then there is the spectre of Bobby Fischer, whom the author makes an unsuccessful attempt to locate, though this is not the best part of the book. Waitzkin interviews a number of Fischer’s former (i.e. ditched) associates. They relate his soft-spot for Hitler and other personal matters, but the chapter would have been stronger without the airy speculation (pages 189-190) of a clinical psychologist who has never met Fischer. Similarly, the book is not well informed on certain current political matters in the chess world. And can Chess Life really be (page 56) ‘a treasured illicit commodity to Russian players’? Other miscellaneous comments: Page 76 has ‘Tisdale’, although the name has been corrected in the British edition. On page 92 an account by Gulko of a game Bronstein was allegedly ordered only to draw with Smyslov during ‘the Zurich Interzonal’ in 1953 obviously refers to the Neuhausen/Zurich Candidates’ event, but there can be no question of Bronstein having had ‘winning chances’ in the short draw with Smyslov played in the 26th round. Nor is there any particular reason for thinking that the draw cost Bronstein the chance of a match against Botvinnik. Page 145: ‘Quintero’s’. Page 226 (final paragraph of the book): Botvinnik was 14, and not 12 as ‘someone said’, when he beat Capablanca in a simultaneous exhibition. But there is little else to regret in Searching for Bobby Fischer. It is a delightful book.

See too: Articles about Bobby Fischer.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.