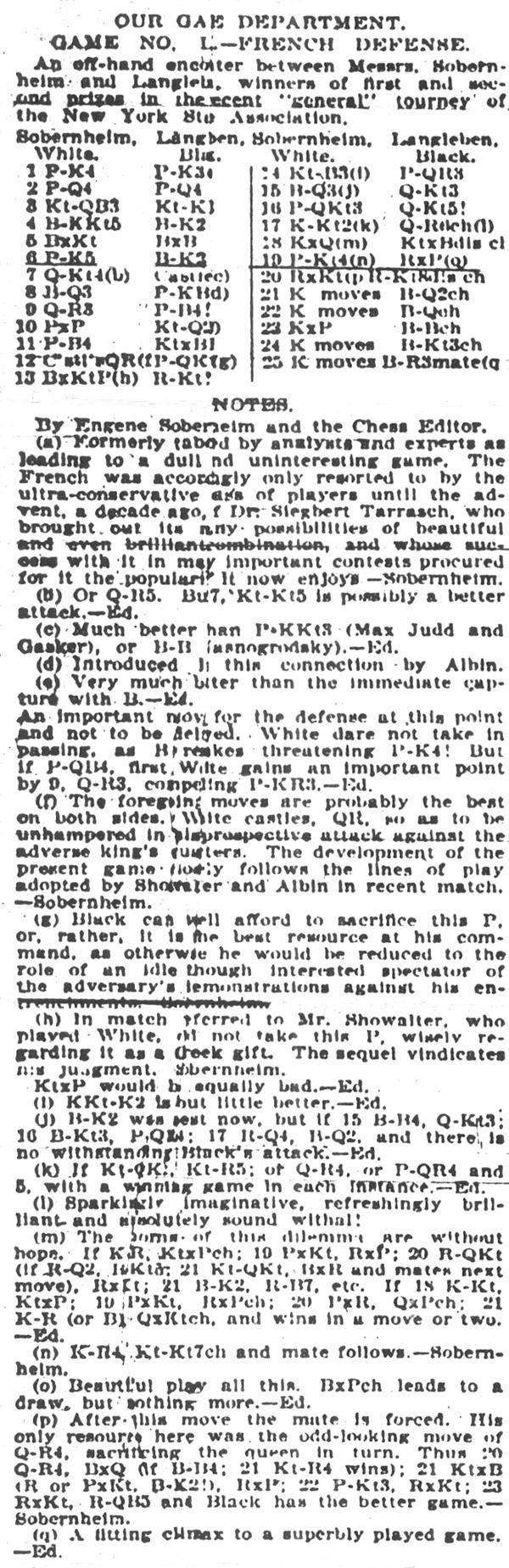

Edward Winter

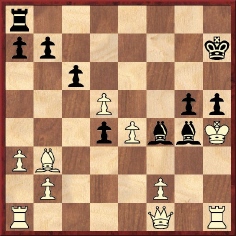

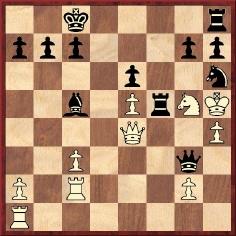

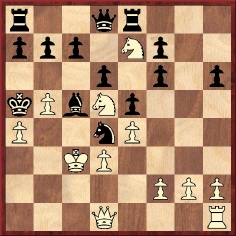

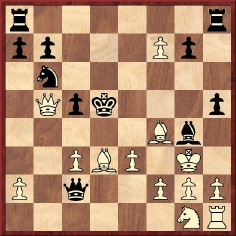

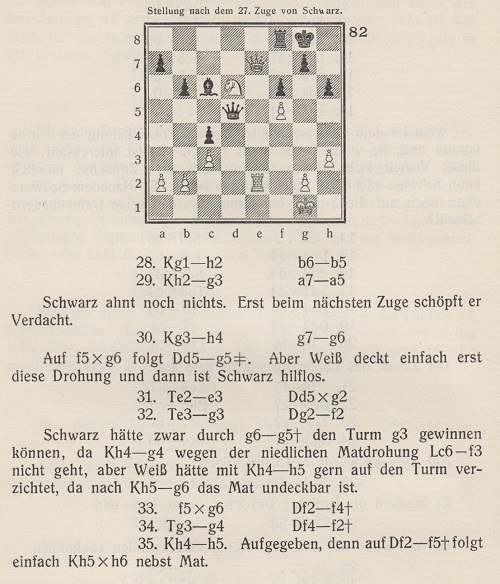

A number of chess literature’s most famous games feature a king which wanders into the open, in most cases reluctantly. That fine writer W.H. Cozens (1911-84) published a book entitled The King-Hunt, and T. Krabbé’s Chess Curiosities had a lengthy chapter on what he termed ‘Steel kings’. Here we examine some other, neglected examples from yesteryear, beginning with the most frequent type: enforced peregrinations. In the position below, the black king is smoked out by a violent combination prepared by an innocent-looking pawn move.

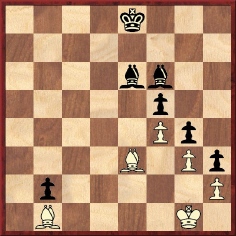

White to move (William Cook and William Henry Krause Pollock – Francis Joseph Lee and Oscar Conrad Müller, London, January 1888). White played 1 a3 and, after the routine reply 1...a5, unleashed 2 Nxe6 Kxe6 3 Qxd5+ Kxd5 4 Ba2 mate.

Source (position only): page 157 of Pollock Memories by F.F. Rowland (Dublin, 1899). In a lecture reported on page 14 of the January 1911 American Chess Bulletin Hermann Helms referred to this ending as ‘the acme of chess artistry’. [Addition on 2 April 2016: the full game was given in C.N. 9827.]

A similar ‘smoking out’ idea had occurred a few years earlier:

Reina – Thimm

Mexico City, circa 1884

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Bc5 4 Nf3 d6 5 O-O O-O 6 c3 c6 7 Bb3 Bg4 8 Be3 Na6 9 Nbd2 d5 10 h3 Bh5 11 g4 Nxg4 12 hxg4 Bxg4 13 Kg2 d4 14 cxd4 exd4 15 Bf4 Qf6 16 Kg3 h5 17 Rh1 Rfe8 18 Qg1 Nb4 19 Qf1 Kh7 20 a3

20...Nd5 21 exd5 Qxf4+ 22 Kxf4 Bd6+ 23 Kg5 f6+ 24 Kh4 Bf4 25 Ne4 Rxe4 26 dxe4 g5+ 27 Nxg5 fxg5 mate.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 June 1884, pages 137-138.

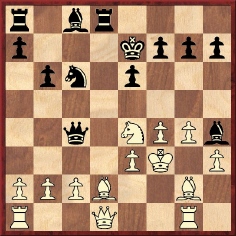

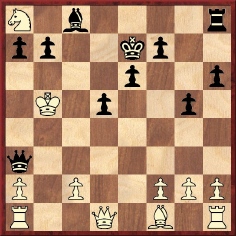

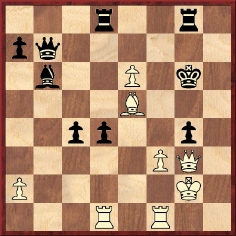

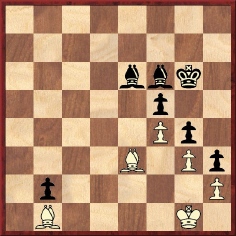

The next position, published on page 278 of the 31 July 1910 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach, also has knight and queen sacrifices on consecutive moves. The only details given are that White was Charles Kühne and that the game was played at the Geneva Chess Club:

White played 1 Qe2, and Black announced an elegant mate in four: 1…Ne5+ 2 fxe5 Qxe4+ 3 Kxe4 Bb7+ 4 Kf4 g5 mate.

It might be an exaggeration to call this game ‘Dufresne’s Evergreen’, but the finish is certainly piquant:

Jean Dufresne – Willberg

Occasion?

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 h5 6 Bc4 Rh7 7 Nxf7 Rxf7 8 Bxf7+ Kxf7 9 d4 d6 10 Bxf4 Nd7 11 Bg5 Be7 12 O-O+ Kg6 13 e5 Bxg5 14 Qd3+ Kh6 15 Rf7 Ngf6 16 hxg5+ Kxg5 17 Rg7+ Kh4

18 Qh3+ gxh3 19 g3 mate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, August 1857, pages 267-268.

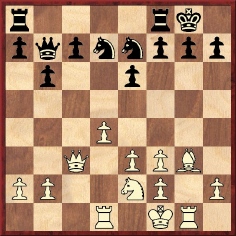

Next, two specimens in which the dragnet is set up by the move Qxg7+, followed by a powerful double check.

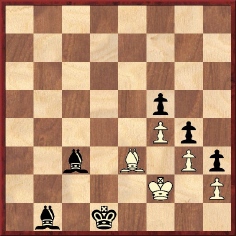

White to move (Vane – Miles, Sydney, 1897). 1 d5 Nxd5 2 Qxg7+ Kxg7 3 Be5+ Kh6 4 Bg7+ Kh5 5 Rxd5+ f5 6 Nf4+ Kh4 7 Rg4+ fxg4 8 Rh5 mate.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 19 December 1897, page 467.

C.S. Anderson – Schneider

Brooklyn, 1908

Hungarian Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Be7 4 O-O Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 h3 O-O 7 d4 exd4 8 Nxd4 Bd7 9 Qd3 h6 10 Qg3 Kh7 (10...Nxd4 wins.) 11 Qd3 Kh8 12 b3 Nh7 13 f4 Na5 14 Bb2 Nxc4 15 bxc4 Qc8 16 Nd5 Qd8 17 Qg3 Bh4

18 Qxg7+ Kxg7 19 Nf5+ Kg6 20 Nxh4+ Qxh4 21 f5+ Bxf5 22 exf5+ Kh5 23 g4+ Qxg4+ 24 hxg4+ Kxg4 25 Rf4+ Kg3 26 Raf1 Ng5 27 Bd4 Nh3+ 28 Kh1 Nxf4 29 Rxf4 Resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September 1908, page 191.

‘A remarkable specimen of chess, particularly by correspondence’ was James Mason’s description of this game:

Lionel C. Moise – J.W. Harriman

Correspondence game, 1899

Evans Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bb6 5 a4 a6 6 c3 Nf6 7 Qb3 O-O 8 d3 d6 9 a5 Ba7 10 Bg5 h6 11 h4 hxg5 (Mason gives this a question mark, suggesting instead 11...Qe7.) 12 hxg5 Ng4 13 Bxf7+ Rxf7 14 g6 Bxf2+ 15 Ke2 d5 16 gxf7+ Kxf7 17 exd5 Na7 18 Rh5 Qf6 19 Nbd2 Qf4 20 d6+ Be6 21 Ng5+ Kg6

22 Qxe6+ Kxh5 23 Rh1+ Bh4 24 Ngf3 Qe3+ (Here Mason recommends 24...g5.) 25 Kd1 Nf2+ 26 Kc2 Qxd3+ 27 Kb3 g5 28 Nxe5 Qxd6 29 g4+ Resigns.

Source: BCM, February 1900, pages 72-73.

Another novel game:

J.R. Deacon – Adrián García Condé1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 c3 e6 5 h3 Qd7 6 Nf3 O-O-O 7 Nh4 Be4 8 Nd2 Be7 9 Nxe4 dxe4 10 Qg4 Nxd4 11 Qxe4 Nb3 12 Be2 Nxc1 13 Nf3 Nxe2 14 Kxe2 Qb5+ 15 Ke3 Qxb2 16 Rhc1 Bc5+ 17 Kf4 Qxf2 18 Rc2 Rf8+ 19 Kg4 Nh6+ 20 Kh5 Qg3 21 Ng5 Rf5 22 h4

22…g6+ 23 Kxh6 Bf8 mate.

Source: BCM, February 1919, page 56.

And now an example from tournament praxis:

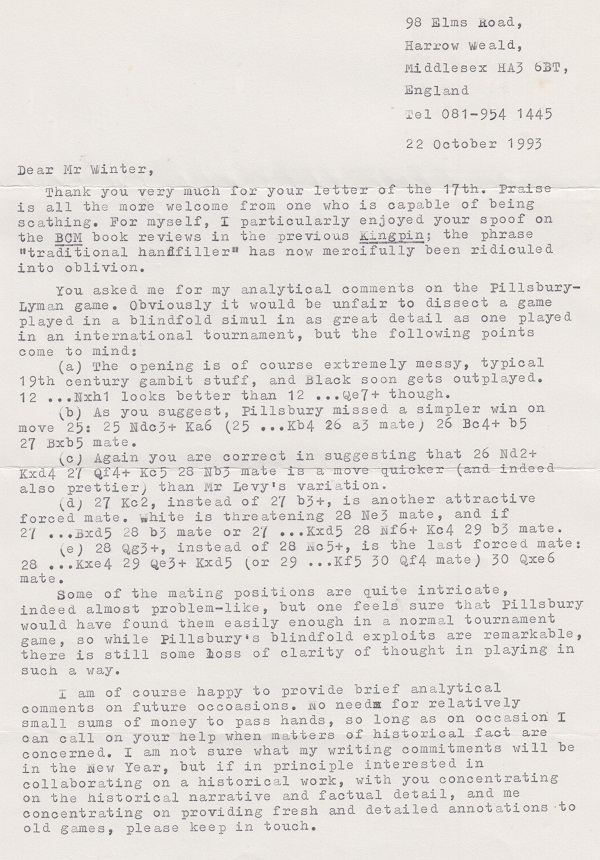

B. Thanhofer – Emmrich

Oeynhausen, 14 August 1922

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Bb4 6 Nb5 Nc6 7 Bg5 h6 8 Bh4 g5 9 Bg3 Nxe4 10 Nc7+ Ke7 11 Nxa8 Nxc3 12 bxc3 Bxc3+ 13 Ke2 Nd4+ 14 Kd3 Qa5 15 Be5 Qxe5 16 Kxc3 Nb5+ 17 Kb3 Qc3+ 18 Ka4 Qa3+ 19 Kxb5 d5 20 White resigns. (In view of the threatened 20...Bd7 mate or 20 Nb6 a6 mate.)

Source: tournament book, pages 168-169.

Sometimes an audacious king will, unprompted, commit felo de se. In the three examples below the king march is neither compulsory nor judicious:

A. Hvistendahl – James Stanley Kipping

Liverpool v Manchester Team Match, Manchester, 17 November 1883

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 O-O Na5 8 Be2 Bd7 9 d5 Qf6 10 Bd3 c5 11 e5 dxe5 12 Nxe5 O-O-0 13 Nxd7 Rxd7 14 Qg4 g6 15 Bb5 Qe7 16 Bxd7+ Qxd7 17 Qxd7+ Kxd7 18 Nc3 Ne7 19 Ne4 Nxd5 20 Rd1 Kc6 21 b4 Nxb4 22 Rd6+ Kb5 (‘This was running his head into the noose indeed, but he may be forgiven on account of the pretty termination which it produces, and because in any case, with correct play, White must have won.’ – C.E. Ranken.) 23 a4+ Kc4

24 Bb2 Nb3 25 Bxh8 Nxa1 26 Nd2 mate.

Source: BCM, January 1884, page 20.

William Hewison Gunston – Oscar Conrad Müller

Manchester, 1890

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 bxc6 8 dxe5 Nb7 9 Nc3 Nc5 10 Nd4 Ba6 11 Qg4 Bxf1 12 Qxg7 Rf8 13 Kxf1 Ne6 14 Nf5 Bg5 15 Qxh7 Bxc1 16 Rxc1 Qg5 17 Re1 Qg6 18 Ne4 Qxh7 19 Nf6+ Kd8 20 Nxh7 Rh8 21 Nf6 Rxh2 22 Kg1 Rh8 23 Rd1 Nf8 24 Nd4 Kc8 25 Nf5 (‘Trying it on. Black’s king might have come back again. It is not clear what he hoped or expected by going to b7.’ – E. Freeborough.) 25...Kb7 26 Nxd7 Ne6 27 Nf6 Rad8 28 Rxd8 Rxd8 29 Ne3 Kb6 30 Kf1 Kc5 31 g3 Kd4 (‘The king is a strong piece and he plays boldly. The ending shows, in amusing fashion, how he may easily be too bold.’ – E. Freeborough.) 32 Nfg4 Ke4 33 Ke1 Ng5 34 Ke2 Rh8 35 c3 Rb8 36 b3 Rh8 37 f4 Nh3 38 Nf6 mate.

Source: BCM, November 1890, pages 456-457.

C. Schmid – C. Schwede

Dresden, 1879

Four Knights’ Game

(Notes abridged from James Mason’s)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 Nd5 Bc5 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Bd7 8 Nh4 h6 9 Bxf6 gxf6 10 Qf3 Nd4 11 Bxd7+ Kxd7 12 Qg4+ Kc6 (‘If 12...Ke8, of course 13 Qg7. However, rather than undertake this ill-starred journey with his king, Black should interpose the pawn, and then, if 13 Nxf5 or 13 exf5, play 13...Qg5.’) 13 Nf5 (‘It would be safer to castle... 13...Nxf5 would defer the end, but make it certain – as certainties in chess are reckoned.’) 13...Nxc2+ 14 Kd2 Nxa1 15 Nfe7+ Kb5 16 a4+ Ka6 17 b4 Nb3+ 18 Kc3 Nd4 19 b5+ Ka5 20 Qd1 Re8 (‘Here Black perhaps misses his only chance. 20...c6 would give his antagonist a great deal of trouble – even if it would not compel him to raise the siege altogether.’)

21 Kc4 Bb4 22 Nxb4 a6 23 Ned5 c5 24 Qd2 Resigns.

Source: BCM, May 1893, page 239.

There is some similarity between the preceding Schmid v Schwede game and this one:

Josef Rejfíř – Karel Treybal

Prague, 18 March 1928

Queen’s Gambit Declined

(Punctuation by Důras)

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 a6 6 cxd5 exd5 7 Bd3 Nbd7 8 Nge2 b6 9 Ng3 g6 10 Bh6!! Bb7 11 h4! c5 12 h5 c4 13 Bc2 b5 14 Bf4! Rg8 15 hxg6 hxg6 16 e4!! Nb6 17 e5! Nfd7 18 Qg4 Nf8 19 Nf5! Bc8 20 Qg3 Ne6 21 Be3 Kd7! 22 Nh6 Rf8 23 f4 Kc6 24 Ke2 b4 25 Na4

25...Kb5! 26 Nxb6 Qxb6 27 Rad1 Ng7 28 Qf3! Be6 29 g4 f5 30 gxf5 Nxf5 31 Nxf5 gxf5 32 Rh6! Rae8 33 Rdh1 Qc6 34 Rg6 Bd8 35 Rhh6 Qd7

36 Qh1!! Bb6 37 Qd1!! Ka5 38 a3! b3 39 Bxb3! Qb5 40 Bd2+!! c3+ 41 Ke1! Bxd4 42 bxc3 Resigns.

Source: Československý Šach, April 1928, pages 54-55. Although Treybal lost, the game was also published on page 115 of the monograph Dr Karel Treybal by L. Prokeš (Prague, 1946).

Just occasionally, a centralized monarch can perform magnificently in the middle-game:

Alfred Crosskill – Edmund Thorold

Beverley (England), 3 September 1875

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 O-O d6 7 d4 exd4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Bg4 10 Bb5 Bxf3 11 gxf3 Kf8 12 Bxc6 bxc6 13 Kh1 Nf6 14 Bg5 h6 15 Bh4 g5 16 Bg3 h5 17 h3 Qd7 18 Kg2 Rg8 19 e5 Nd5 20 Nxd5 cxd5 21 Qd3 g4 22 hxg4 hxg4 23 f4 c5 24 dxc5 dxc5 25 Rad1 Rd8 26 f5 c4 27 Qa3+ Kg7 28 e6 fxe6 29 fxe6 Qb7 30 Be5+ Kg6 31 Qg3 d4+ 32 f3

32...Kf5 (‘This king is the most attacking piece on the board.’ – J. Wisker.) 33 Qf4+ Kxe6 34 Qf6+ Kd5 35 Bxd4 gxf3+ 36 Kf2 Rg2+ 37 Kxf3 Bxd4 38 Kxg2

38...Kc5+ 39 Qf3 Rg8+ 40 Kh2 Qh7+ ‘and Black wins’.

Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, October 1875, pages 337-338.

Karsten Müller (Hamburg, Germany) writes regarding the above game (given on page 125 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves).

Crosskill played 37 Kxf3 and lost, but our correspondent comments:

‘White could hold the position with 37 Ke3!:

A) 37...Re8+ 38 Kxf3 Bxd4 39 Qxd4+ Ke6+ 40 Ke3 Rg3+ 41 Ke2 Rg2+ (41...Rd3 42 Qxc4+ Rd5 43 Rxd5 Qxd5 44 Qxd5+ Kxd5+ 45 Kd3 =) 42 Ke3 Rg3+ 43 Ke2 =.

B) 37...Re2+ 38 Kxf3 Bxd4 39 Qxd4+ Ke6+ 40 Kxe2 Rxd4 41 Rxd4 Qa6 42 Rff4 Qxa2+ 43 Kf3 c3 44 Rfe4+ =.’

(2341)

From pages 128-129 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

In C.N. 1399 (as well as on page 58 of Chess Explorations) we gave the following odds game, taken from pages 24-25 of Mein Abschied vom Schach by J. Krejcik (Berlin, 1955):

Josef Krejcik – N.N.

Café ‘Jägerzeile’, Vienna, April 1947(Remove White’s queen.)

1 e4 e6 2 d4 h6 3 Nc3 a6 4 Nf3 g5 5 Bc4 g4 6 Ne5 f5 7 exf5 exf5 8 Bf7+ Ke7 9 Nd5+ Kd6 10 Nc4+ Kc6 11 Nb4+ Kb5 (We wondered why 11…Bxb4+ was not played here.) 12 a4+ Kxb4 13 Bd2 mate.

We now note that the score was published on page 144 of the May 1962 Chess Review by Walter Korn, who made the following points:

a) the actual finish was: 10 c4 b6 (Richard Forster points out to us the line 10…c5 11 b4 cxd4 12 Bf4 and White is winning.) 11 c5+ bxc5 12 Nc4+ Kc6 13 Na5+ Kb5 14 a4+ Kxa5 13 Bd2 mate.

b) ‘Krejcik told me in 1949 that he really played this silly game against a Dr Gruber’.

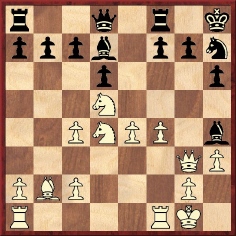

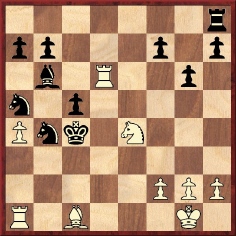

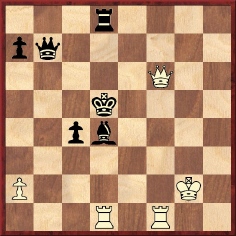

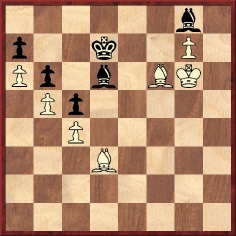

In the next example, the White allies miss their chance of a rare march:

White to move (Edersheim and Rudolf Johannes Loman – Censer and van’t Veer, The Hague, 14 May 1915). White played 25 Qxa7 and the game was eventually drawn. In the Amsterdam publication Weekblad A. Speyer pointed out that White could win easily and prettily by 25 Qc6+ Kf8 26 Qc8 Ke8 27 h4 (Preventing 27…g5, followed by 28…Rg6. If 27…g5 then 28 h5.) and the white king is free to infiltrate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, September 1915, page 269.

In the game below both kings have Wanderlust:

E.R. Perry – G.E. Croy

Los Angeles, 1918

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bf4 Nbd7 5 e3 c5 6 Nb5 e5 7 dxe5 Qa5+ 8 Ke2 dxc4 9 Nd6+ Bxd6 10 Qxd6 Ne4 11 Qd5 Qb4 12 Rb1 Nc3+ 13 bxc3 Qxb1 14 Qxc4 h5 15 e6 Qc2+ 16 Kf3 Nb6 17 exf7+ Kd8 18 Bg5+ Kd7 19 Qb5+ Kd6 20 Bf4+ Kd5 21 Bd3 Bg4+ 22 Kg3 (‘The kings do a merry dance around the board. For one player’s king to be at g3 and the other player’s at d5 with so much material remaining makes the position look more like a problem than an actual game.’)

22…Qxc3 23 Nf3 Bd7 24 Qb1 Qf6 25 Ng5 h4+ 26 Kf3 c4 27 Be4+ Kc5 28 a3 a5 29 Rd1 Rh5 30 Rd6 Bg4+ 31 Kxg4 Rxg5+ 32 Kf3 Nd5 33 Bxd5 and wins.

Source: BCM, September 1918, page 278. It was stated that ‘Master Croy’ was aged 15.

The above article first appeared at the Chess Café in 1998.

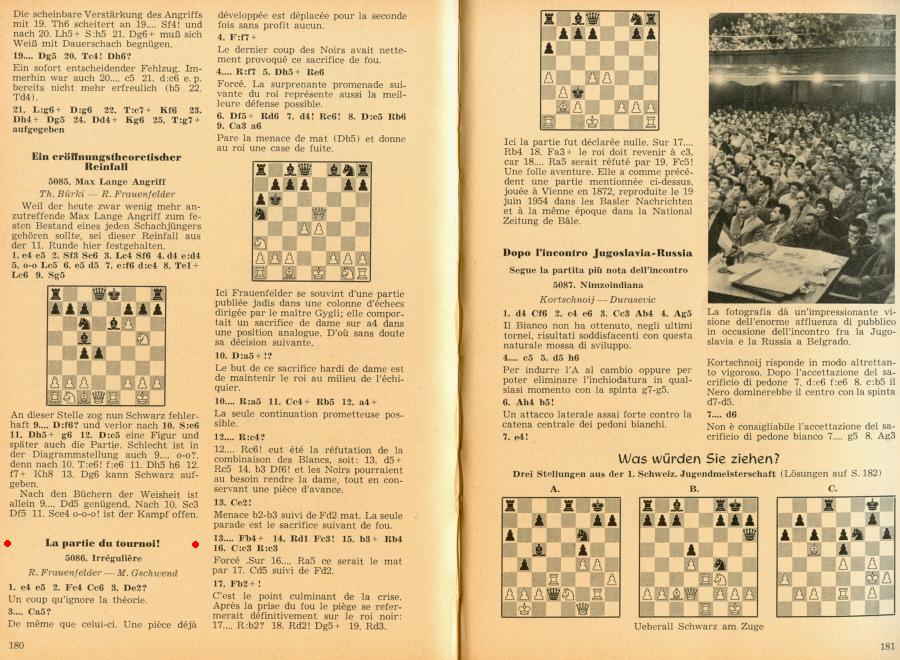

The first chapter of François Le Lionnais’ book Tempêtes sur l’échiquier (Paris, 1981) is intriguing. On page 10 he gives the score of the famous game Hamppe v Meitner, Vienna, 1872 (our readers will have no trouble finding the game) and then adds the following, astonishingly similar battle:

Rudolf Frauenfelder – Max Gschwend1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 Qe2 Na5 4 Bxf7+ Kxf7 5 Qh5+ Ke6 6 Qf5+ Kd6 7 d4 Kc6 8 Qxe5 Kb6 9 Na3 a6 10 Qxa5+ Kxa5 11 Nc4+ Kb5 12 a4+ Kxc4 13 Ne2 Bb4+ 14 Kd1 Bc3 15 b3+ Kb4 16 Nxc3 Kxc3 17 Bb2+ Kb4 18 Ba3+ Kc3 and drawn by perpetual check.

(Le Lionnais wrote ‘Frauenfelder v Gshend, Switzerland, 1957.’)

(286)

The game was published in the March 1957 BCM, page 59, the source being Leonard Barden’s The Field column of 17 January 1957. That must mean that Le Lionnais’ ‘1957’ was wrong. The BCM (D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column) gives ‘1956 Swiss Boys’ Championship’ and states that the players were R. Frauenfelder and M. Gschwend. D.J. Morgan’s view was that ‘two bright lads have pulled a fast one!’ He added that ‘the commentator on the game in the Zurich National Zeitung [sic] did not notice the identity of the old game’.

(1397)

The Frauenfelder v Gschwend game was published on pages 180-181 of the September 1956 Schweizerische Schachzeitung, where it is described as ‘the game of the tournament’ (Swiss Junior Championship). The annotations state that after move nine White recalled the nineteenth-century game from a column by Gygli a couple of years earlier.

In May 1998 Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) verified the matter with R. Frauenfelder. The latter stated that several participants in the event, including Gschwend, were staying at his family’s home. Both he and Gschwend had lost badly the previous day and therefore decided to make an amusing and spectacular draw. In short, their game was pre-arranged.

(Footnote on page 50 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves)

Walter Korn gave the game on page 237 of the August 1957 Chess Review, commenting, ‘... we share our British colleagues’ opinion that this draw is somewhat wilful’.

The item concluded with a strange remark by Korn:

‘Finally, as we are debunking history, the 1872 game was also a mere analysis, more of which was summarized in the Deutsche Schachzeitung of 1895.’

On page 10 of the January 1890 International Chess Magazine Steinitz wrote:

‘... I beg to claim to the best of my belief and knowledge as my own entirely what is not distinctly acknowledged as belonging to somebody else, including “the principles” and “the modern school”, on which subject their full due is given in my book to Heydebrand, Staunton, Winawer, Paulsen, etc., and some more will be said in my second volume about a still more important forerunner of modern play, Herr Hammppe [sic] of Vienna.’

Steinitz was referring to his book The Modern Chess Instructor; the reference to Hamppe is most interesting. Who can say more about this unsung hero?

(1635)

From G.H. Diggle (Hove, England):

‘In C.N. 1635 you ask for more about the “unsung hero Hamppe”, misspelt by Steinitz “Hammppe” and by both Staunton and Harrwitz “Hampe”. I have had a little search and find the following item in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1850, page 289:

“Chess in Germany. A few months since the members of the chess circle at Berlin were gratified with a visit from Herr Hampe, who since the departure of Mr Löwenthal is accounted the strongest player in Vienna. ‘He has won’, observes the Berlin Schachzeitung, ‘from Mr Jenay a majority though not a very large one; he has been defeated by the celebrated Löwenthal, but not disgracefully, since he won [sic] in the ratio of four to five. He played also with Mr Falkbeer in the last month which the latter spent in Vienna, about 30 games, of which Mr Hampe was only one or two ahead. Finally he has had an opportunity lately of measuring himself against Mr Szén, with whom, to use his own expression, he got off better than in former combats. The games which he played with us bear evident marks of that genius and originality for which his play is remarkable. In style he reminds us of an old friend, Mr Schorn, who has always ready some ‘devilment’ which is not to be found in the books.”

(Schorn was, of course, the weakest of the seven “Berlin Pleiades”, though he was “as much above Horwitz as a painter as he was below him as a chessplayer” – W. Wayte in the BCM, 1882, page 44.)

This paragraph is followed by two of Hamppe’s games, a draw v Hanstein and a win against Wolff.

In 1852 Harrwitz visited Vienna and played seven games with Hamppe (Harrwitz 4 Hamppe 1, drawn 2). For the scores see Chess Review, 1853, page 258 et seq.

Hamppe’s recorded games in Staunton’s Chess Praxis show him as a 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 addict: two losses to Szén on pages 81-82, a draw with Szén on page 429, two losses to Löwenthal on pages 431-435, one loss to Falkbeer on page 436. Page 225 of Harrwitz’s Chess Review, 1853 has a loss by Hamppe to Szén. His unique game against Meitner appeared in La Stratégie, 1872, page 323.’

(1714)

Detailed notes to the Hamppe v Meitner game are also to be found in the following sources:

A minuscule photograph of Hamppe was given in C.N. 3478. Regarding the comment by Steinitz concerning Hamppe’s significance in the development of the game, see the feature article Steinitz, Lasker, Potter and ‘Modern Chess’.

On the subject of Hamppe’s forename (Karl, not Carl), see C.N. 11434.

Sixten Johansson (Göteborg, Sweden) has found this brevity on pages 36-37 of Eero Böök’s entertaining book Odödliga partier och andra schackkåserier (Halmstad, 1966) – (Immortal games and other chess chats):

Eero Einar Böök – A. Hiidenheimo

Helsinki (junior tournament), 1924

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nxe4 4 Qh5 Ng5 5 d4 Ne6 6 d5 g6 7 dxe6 gxh5 8 exf7+ Ke7 9 Bg5+ Kd6 10 O-O-O+ Kc5 11 Rd5+ Kxc4 12 b3+ Kb4 13 Rb5+

13...Ka3 (13...Kxc3 14 Ne2 mate is remarkable.) 14 Nb1+ Kxa2 15 Ra5+ Ba3+ 16 Rxa3 mate.

(648)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 Bc4 Bh4+ 5 g3 fxg3 6 O-O gxh2+ 7 Kh1 Be7 8 Bxf7+ Kxf7 9 Ne5+ Ke8 10 Qh5+ g6

11 Nxg6 Nf6 12 Rxf6 Bxf6 13 Ne5+ Ke7 14 Qf7+ Kd6 15 Nc4+ Kc5 16 Qd5+ Kb4 17 a3+ Ka4 18 b3 mate.

Source: Revista Cubana de Ajedrez, September-October 1923, page 23.

W.C. Spencer – N.N.

Fort Snelling (USA), 1884 (?)

Four Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 Bc4 Nxe4 5 Bxf7+ Kxf7 6 Nxe4 d5 7 Nfg5 Kg6 8 Qf3 dxe4 9 Qf7 Kxg5 10 d3+ Kh4 11 g3+ Kh3 12 Qh5+ Kg2 13 Bg5 Qe8

14 Rg1 Kxg1 15 Qe2 Kg2 16 Qxe4+ Kh3 17 Qh4+ Kg2 18 g4 Resigns.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, November 1884, page 31.

(Kingpin, 1994)

A complex game with underpromotion and a strange king march was given in C.N. 2353:

Häfner – L. Herrmann

Dortmund, 1937

Nimzo-Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Nc6 5 Nf3 d6 6 Bg5 h6 7 Bxf6 Qxf6 8 e3 O-O 9 Bd3 e5 10 d5 Nb8 11 O-O Bxc3 12 Qxc3 Qe7 13 Nd2 f5 14 f4 Nd7 15 Rae1 e4 16 Bc2 a5 17 Nb3 a4 18 Nd4 Nf6 19 b4 axb3 20 axb3 Bd7 21 Ra1 c5 22 dxc6 bxc6 23 b4 Kh7 24 h3 Nh5 25 Kh2 g5 26 Rxa8 Rxa8 27 g4 fxg4 28 fxg5 Qe5+ 29 Kg1 Qg3+ 30 Kh1 Qxh3+ 31 Kg1 Ng3 32 Rf7+ Kg8 33 Rg7+ Kh8 34 Rf7 Ra1+ 35 Qxa1 Qh1+ 36 Kf2 Qxa1 37 Rxd7 Nh5 38 Bxe4 g3+ 39 Ke2 Qb2+ 40 Kf3 g2 41 Ne6

41…g1(N)+ 42 Kg4 Qe2+ 43 Kf5 Ng3+ 44 Kf6 Nxe4+ 45 Kg6 Nf6 46 gxf6 Qg4+ 47 Kf7 h5 48 Nf8 Nf3 49 Ke8 Ne5 50 Rh7+ Kg8 51 Rg7+ Qxg7 52 fxg7 h4 53 Nh7 h3 54 Nf6+ Kxg7 55 Nh5+ Kh6 56 Ng3 Drawn (although the endgame is a win for Black).

Source: Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 November 1937, pages 346-348.

The game between H. Colborne and Frederick William Womersley, Hastings, 1883 or 1884 (C.N. 2618) saw a most unusual march by the black king:

Play went: 72…Bf6 73 Be3 Kb4 74 Kf2 Kb5 75 Kg1 Kc6 76 Kf2 Kd7 77 Kg1 Ke8

78 Kf2 Kf7 79 Kg1 Kg6

80 Kf2 Bd5 81 Kg1 Be4 82 Ba2 b1(Q)+ 83 Bxb1 Bxb1 84 Bf2 Kf7 85 Ba7 Ke6 86 Bf2 Kd5 87 Ba7 Ke4 88 Kf2 Kd3 89 Be3 Bc3 90 Bb6 Kd2 91 Be3+ Kd1

92 Kg1 Ke2 93 Bb6 Be1 94 Bc5 Kf3 95 Bb6 Bxg3 96 hxg3 Kxg3 97 Bf2+ Kxf4 98 Kh2 Kf3 99 Bc5 f4 100 Bb6 Bf5 101 Bg1 g3+ 102 Kh1 Be4 103 Bb6 and Black mates in two.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 August 1884, page 168.

C.N. 4882:

Subsequently, Womersley adapted the position into an endgame puzzle, reversing the colours and offering a book prize for the first solution (BCM, June 1886, page 264). A corrected position (with the black king on d7 and not e8) appeared on page 301 of the July 1886 issue, and the solution followed on pages 337-339 of the August-September 1886 BCM – over 80 lines of analysis.

White to move and win

J. Drabble – S. Chadwick

Correspondence game (Gambit Tourney, Pillsbury National

Correspondence Chess Association)

Steinitz Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 d4 Qh4+ 5 Ke2 b6 6 Nf3 Ba6+ 7 Kd2 Qf2+ 8 Ne2 Nb4 9 Qe1 Nf6 10 Kc3 Nxe4+ 11 Kb3 d5 12 c3 Bc4+ 13 Ka4 b5+ 14 Ka5 Nc6+ 15 Ka6 b4+ 16 Kb7 Rb8+ 17 Kxc6 Rb6+ 18 Kxc7 Bd6+ 19 Kc8

19...Ke7 mate.

Source: the Chess Weekly, 15 August 1908, page 86.

(2715)

A game from page 632 of L’Echiquier, May 1927 was given in C.N. 2977:

P. Mendlewicz – Victor Soultanbéieff

Liège, 20 December 1926

Irregular Opening

1 e3 e5 2 b3 d5 3 Bb2 Nd7 4 Nf3 Bd6 5 c4 Ngf6 6 cxd5 Nxd5 7 Bc4 N5b6 8 O-O Nxc4 9 bxc4 e4 10 Nd4 Ne5 11 Nb5 Nf3+ 12 gxf3 Bxh2+ 13 Kxh2 Qh4+ 14 Kg1 Qg5+ 15 Kh2 Qh5+ 16 Kg3 Qh3+ 17 Kf4 Qh4+ 18 Ke5

18…c5 (Soultanbéieff gives this two exclamation marks.) 19 Nd6+ Ke7 20 Nxc8+ Raxc8 21 f4 Rhd8 22 Kxe4 f5+ 23 Kxf5 Rf8+ 24 Ke4 g5 25 Be5 gxf4 26 Rh1 Qg5 27 Rxh7+ Ke6 28 Qh5 Qg2+ 29 f3 Resigns.

Concerning 19…Ke7 Soultanbéieff writes:

‘This “logical” move loses the game, whereas the bolder 19…Kd8!!, which I indicated subsequently, leads to countless very beautiful variations and would have won by force.’

The diagram below shows the position after 19…Kd8:

Soultanbéieff now analysed eight White moves as leading to a win for Black, one example being 20 Nxf7+ Kc7 21 Nxh8 Qg5+ 22 Kxe4 Qf5 mate. A possibility not mentioned is 20 Kd5, and C.N. 2977 asked if Black also won after that move. In C.N. 2981 Karsten Müller (Hamburg, Germany) responded that after 20 Kd5 b6 Black does indeed win, as follows: 21 Nxc8 (Or 21 d3 Qe7, and if 21 Be5 Be6+ 22 Kc6 Qe7.) 21...Kxc8 22 f4 f5 23 Be5 Qe7.

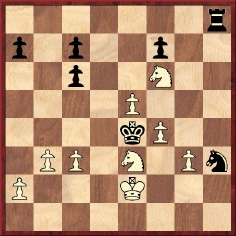

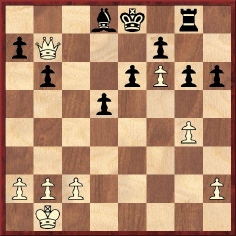

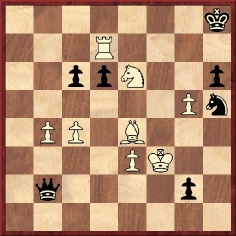

By no means unknown, the game below, from C.N. 4123, is worth noting for a curious march by the black king, which strays as far as f4 and e4 but is back on its home square at the moment of victory:

G. Bezručko – Efim Dimitrijewitsch Bogoljubow

Kemeri-Riga, March 1939

Sicilian Defence

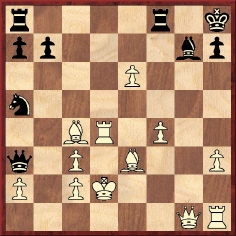

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Qxd4 Nc6 4 Qe3 Nf6 5 Nc3 g6 6 Be2 d6 7 f4 Bg7 8 Nf3 Ng4 9 Qg1 f5 10 h3 Nf6 11 exf5 Bxf5 12 Nd4 O-O 13 Nxf5 gxf5 14 Be3 d5 15 O-O-O e6 16 g4 Ne4 17 gxf5 Nxc3 18 bxc3 Qa5 19 fxe6 d4 20 Rxd4 Kh8 21 Bc4 Qa3+ 22 Kd2 Na5

23 Qxg7+ Kxg7 24 Rd7+ Kf6 25 Bd4+ Kf5 26 Rd5+ Kxf4 27 Be3+ Ke4

28 Rd4+ Ke5 29 Rd5+ Kf6 30 Bd4+ Ke7 31 Rd7+ Ke8 32 Bb5 a6 33 Rxb7+ axb5 34 White resigns.

Source: Šachs Latvijā by K. Bētiņš, A. Kalniņš and V. Petrovs (Riga, 1940), pages 265-266. The game also appeared, with detailed (languageless) notes on pages 229-230 of Bogoljubow – The Fate of a Chess Player by S. Soloviov (Sofia, 2004).

C. Chapman (Kent) – C. Coates (Cheshire)

Correspondence

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 d4 exd4 4 e5 Ne4 5 Qe2 Bb4+ 6 Kd1 d5 7 exd6 f5 8 dxc7 Qxc7 9 Nxd4 O-O 10 Qc4+ Qxc4 11 Bxc4+ Kh8 12 Ke2 Re8 13 Bb5 Bd7 14 Kf3 Nc6 15 Nxc6 bxc6 16 Rd1 Nf6 17 Ba4 f4 18 h3 g5 19 a3 g4+ 20 hxg4 Bxg4+ 21 Kxf4 Ba5 22 Kg5

22...h6+ 23 Kxf6 Bd8+ 24 Rxd8 Raxd8 25 Bxh6 Rd5 26 Kf7 Re6 27 Bg7+ Kh7 28 Bb3 Rd7+ 29 Kf8

29...Re2 30 f4 Rxg7 31 Nc3 Rd2 32 Rh1+ Kg6 33 f5+ Bxf5 34 Rd1 Rf2 35 Ke8 Rb7 36 White resigns.

Sources: BCM, May 1915, page 173; Chess Amateur, August 1915, page 327; The “British Chess Magazine” Chess Annual 1915 by I.M. Brown (Leeds, 1916), page 171.

(7956)

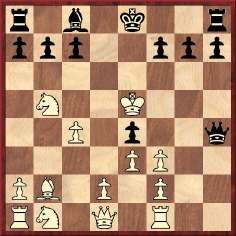

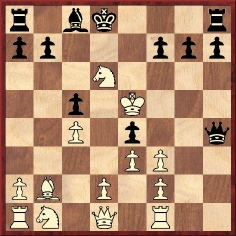

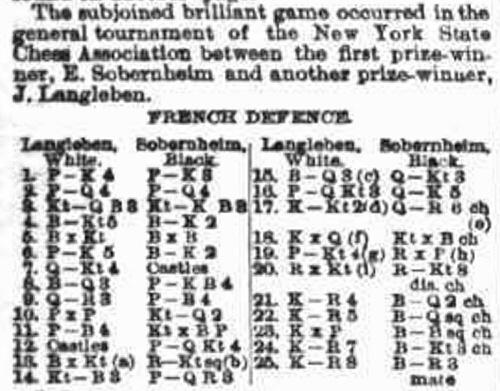

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e5 Be7 7 Qg4 O-O 8 Bd3 f5 9 Qh3 c5 10 dxc5 Nd7 11 f4 Nxc5 12 O-O-O b5 13 Bxb5 Rb8 14 Nf3 a6 15 Bd3 Qb6 16 b3 Qb4 17 Kb2

17...Qa3+ 18 Kxa3 Nxd3+ 19 b4 Rxb4 20 Rxd3 Rb1+ 21 Ka4 Bd7+ 22 Ka5 Bd8+ 23 Kxa6 Bc8+ 24 Ka7 Bb6+ 25 Ka8

25...Ba6 mate.

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) points out two newspaper appearances of this famous miniature, with a discrepancy over the winner and loser, and over whether or not it was a formal game.

New York Recorder, 3 March 1895

Evening Post (New York), 9 March 1895, page 12

The game is commonly given in chess literature as ‘Sobernheim v Langleben, Montreal, 1895’, e.g. on page 525 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1955). On the other hand, page 126 of Learn Chess from the Greats by Peter J. Tamburro (Mineola, 2000) referred to ‘Langleben-Sobenheim [sic] from a New York tournament from the thirties’. On page 4 of the April 1933 Chess Review Chernev had presented the game (‘Langleben-Sobenheim’) without a date, merely stating that it was ‘played in a New York tournament’. It was also given as Langleben v Sobenheim/New York/undated when Chernev published it again on page 256 of the December 1942 Chess Review, but a few years later, on page 64 of The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948), he reversed the names, corrected Sobenheim to Sobernheim and changed New York to Montreal, 1895.

Those alterations in the 1948 book brought the details into line with what had appeared on pages 169-170 of the June 1895 Deutsches Schachzeitung, which reported that the game had been played recently at the Montreal Chess Club.

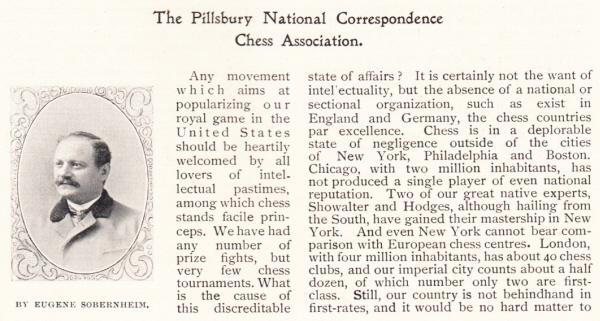

Both Sobernheim and Langleben were New York players. Regarding Eugene Sobernheim, see, for instance, page 285 of the September-October 1893 American Chess Monthly, as well as pages 89-90 of the July 1897 American Chess Magazine, where he contributed an article:

Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996) published two games in which Salomon Langleben was an opponent. They were played at the Buffalo Chess Club, New York and in Brooklyn.

The following news report, concerning chess in New York, appeared on page 164 of the April 1895 BCM:

‘For the general or free-for-all tourney there were 18 entrants, including Messrs Frère, Helms and other strong players. The outcome was that Mr Soberheim [sic] succeeded in winning the first prize, the others being divided among Messrs Buz, Langleben, T. Lipschütz, Napier and Roething.’

Regarding the nature (i.e. off-hand or otherwise) of the royal walkabout game, see page 9 of Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997), as well as the details provided in the full New York Recorder column of 3 March 1895, which is available at the Chess Archaeology website.

How did Montreal, rather than New York, become so widely associated with the game?

(7989)

A game submitted by Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia):

A.A. Murray – Floyd E. Hebert

Washington State Tourney, 1949

English Opening

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 e6 3 e4 Nc6 4 d4 d5 5 e5 Ne4 6 Nf3 Bb4 7 Qc2 O-O 8 Bd3 f6 9 O-O Bxc3 10 bxc3 fxe5 11 dxe5 Ne7 12 Ba3 Rf4 13 Rad1 Qe8 14 Nd4 Nf5 15 Bxe4 Rxe4 16 Rfe1 Qh5 17 Rxe4 dxe4 18 Nxf5 exf5 19 Rd8+ Kf7 20 Qa4 c6 21 Qb4 Kg6 22 Qd6+ Kg5 23 g3 f4 24 Bc1 Kg4 25 Bxf4 Kh3 26 Rh8

26...Bf5 27 Rxa8 Qf3 28 Kf1 Qh1+ 29 Ke2 Bg4+ 30 Ke3 Qf3+ 31 Kd4 Qd3+ 32 Kc5 b6+ 33 Kxc6 Qxc4+ 34 Kb7 Qf7+ 35 Kb8

35...e3 36 Bxe3 Qe8+ 37 Kxa7 Qa4+ 38 Kb8 Qe8+ 39 Ka7 Qa4+ 40 Kxb6 Qxa8 41 a3 Qa4 42 Qb4 Qe8 43 Qb5 Qb8+ 44 Ka5 Qd8+ 45 Kb4 Qe7+ 46 Kb3 Be6+ 47 Kb2 Qd8 48 Kc1 Qa8 49 Qb4 Qh1+ 50 Kd2 Qd5+ 51 Ke2 Bg4+ 52 f3 Qxf3+ 53 Kd3 Qd5+ 54 Bd4 Bf5+ 55 Ke2 Qe4+ 56 Be3 Qc2+ 57 Kf3 Qd1+ 58 Kf4 Qg4 mate.

Source: Washington Chess Letter, August 1950, page 12.

A.A. Murray, who was the Games Editor, commented:

‘This game is the most shattering experience White has had at the chess board.’

(8174)

For a note on Arthur A. Murray, see C.N. 8190.

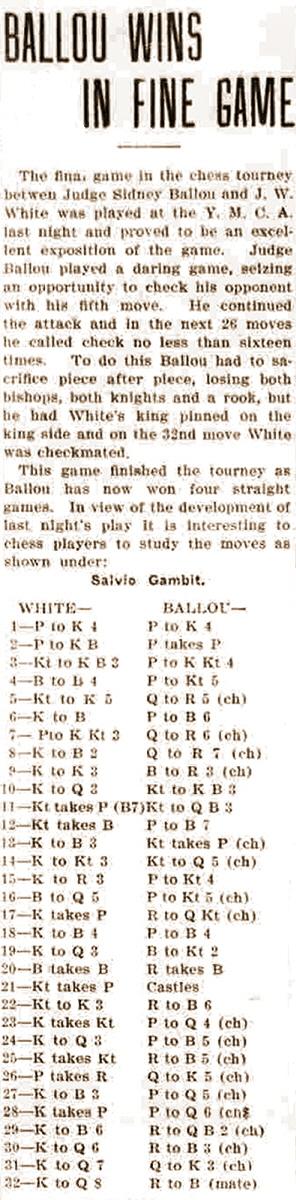

A royal walkabout submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére:

J.W. White – Sidney Miller Ballou

Fourth match-game, Honolulu, 24 October 1910

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Ne5 Qh4+ 6 Kf1 f3 7 g3 Qh3+ 8 Kf2 Qg2+ 9 Ke3 Bh6+ 10 Kd3 Nf6 11 Nxf7 Nc6 12 Nxh6 f2 13 Kc3 Nxe4+ 14 Kb3 Nd4+ 15 Ka3

15...b5 16 Bd5 b4+ 17 Kxb4 Rb8+ 18 Kc4 c5 19 Kd3 Bb7 20 Bxb7 Rxb7 21 Nxg4 O-O 22 Ne3 Rf3 23 Kxe4 d5+ 24 Kd3 c4+ 25 Kxd4

25...Rf4+ 26 gxf4 Qe4+ 27 Kc3 d4+ 28 Kxc4 d3+ 29 Kc5 Rc7+ 30 Kd6 Rc6+ 31 Kd7 Qe6+ 32 Kd8 Rc8 mate.

Source: Hawaiian Star, 25 October 1910, page 6:

(8533)

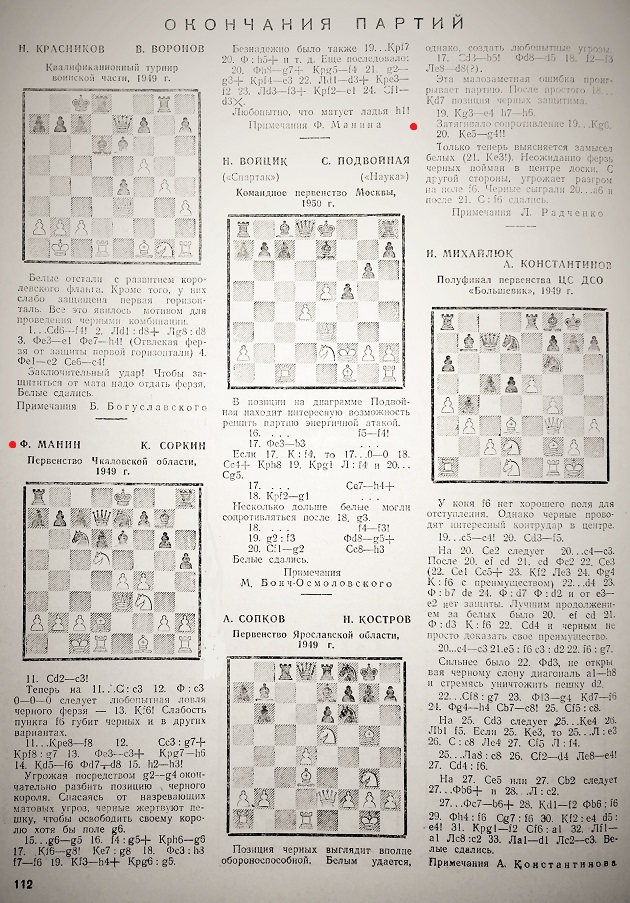

A further specimen (Manin v Sorkin, Chkalovsky, 1949) is provided by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére, from page 112 of the 4/1950 Shakhmaty v SSSR:

11 Bc3 Kf8 12 Bxg7+ Kxg7 13 Qc3+ Kh6 14 Nf6 Qd8 15 h3 g5 16 fxg5+ Kg6

17 Ng8 Nxg8 18 Qxh8 f6 19 Nh4+ Kxg5 20 Qg7+ Kf4 21 g3+ Ke3 22 Rd3+ Kf2 23 Rf3+ Ke1

24 Bd3 mate.

As regards the missing opening moves, our correspondent points out that the position after Black’s tenth move occurred in Chigorin v Mackenzie, Vienna, 1882 with one exception: Mackenzie played 10...O-O-O and did not move his h-pawn. Source: pages 152-154 of Das II. Internationale Schachmeisterturnier Wien 1882 by C.M. Bijl (Zurich, 1984).

(8911)

A further game submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére:

Eldorous Lyons Dayton – A.G. Pearsall

Correspondence

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Nxc3 Bc5 5 Bc4 d6 6 Qb3 Nc6 7 Bxf7+ Kf8 8 Bxg8 Rxg8 9 Nd5 Nd4 10 Qd3 Bd7 11 b4 Ba4 12 bxc5 Nc2+ 13 Kf1 Nxa1 14 Qf3+ Ke8 15 Qh5+ Kd7 16 Qf5+ Kc6 17 Nb4+ Kb5

18 c6+ Kxb4 19 Bd2+ Ka3 20 Qa5 b5 21 Qb4+ Kxa2 22 Bc1 Qf6 23 Ne2 Nb3 24 f4 Nxc1 25 Nxc1+ Ka1 26 Qa3+ Kb1 27 Qa2+ Kxc1

28 Ke2+ Resigns.

Source: Philadelphia Inquirer, 26 February 1950, page 22. Isaac Ash’s column stated that the game was ‘played in a recent mail contest’.

(10267)

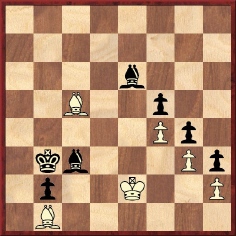

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O Nxe4 6 Re1 d5 7 Bxd5 Qxd5 8 Nc3 Qh5 9 Nxe4 Be6 10 Bg5 Be7 11 Bxe7 Nxe7 12 Qxd4 O-O 13 Ng3 Qh6 14 Rad1 Nc6 15 Qa4 Rad8 16 Nd4 Nxd4 17 Rxd4 Rxd4 18 Qxd4 b6 19 Qe5 c5 20 f4 Bc8 21 f5 Qc6 22 Qe7 Bb7 23 Re2 Qd5 24 h3 b5 25 Kh2 (As will be seen below, there is no unanimity over the move-order in this phase.) 25...f6 26 Ne4 c4 27 Nd6 Bc6 28 c3 h6 29 Kg3 a6 30 Kh4 g6 31 Re3 Qxg2 32 Rg3 Qf2 33 fxg6 Qf4+ 34 Rg4 Qf2+ 35 Kh5 Qc5+ 36 Kxh6 Resigns.

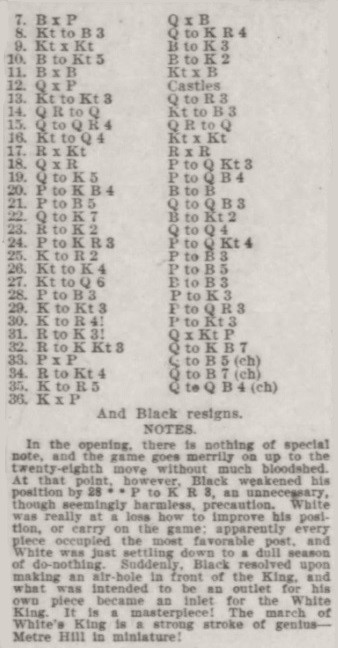

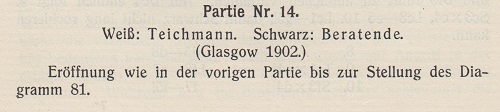

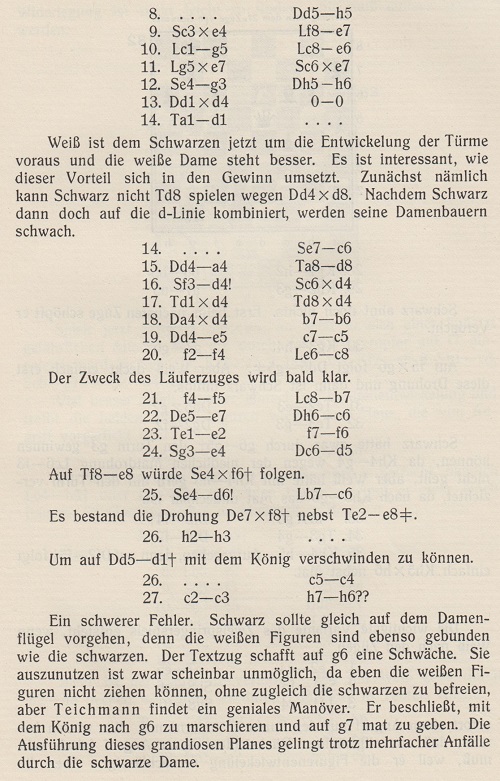

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

‘It appears that the well-known game Teichmann v Allies, supposedly played in Glasgow in 1902, actually occurred there three years later.

The game is in various books and databases, and Teichmann’s use of his king in the closing stages is a winning idea seen in Short v Timman, Tilburg, 1991. There are slightly different versions of the Teichmann game, and, for instance, page 75 of L. Pachman’s Modern Chess Strategy (London, 1963) had 28 Kh2, 29 Kg3 and 30 Kh4, whereas White appears to have placed his king on h2 a few moves earlier:

I have noted this reference to the game on page 8 of the Falkirk Herald, 20 September 1905:

Page 8 of the Falkirk Herald of 15 March 1905 gave the dates of some of Teichmann’s engagements:

Monday, 13 March: Queen’s Park Chess Club

Tuesday, 14 March: Central Chess Club

Wednesday, 15 March: Stirling

Thursday, 16 March: Falkirk Chess Club

Friday, 17 March: Burns Chess Club.The Queen’s Park, Central and Burns Chess Clubs were all in Glasgow.’

We add the game’s appearance on page 11 of section two of the 11 June 1905 New Orleans Times-Democrat:

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) has forwarded us a photocopy of the game’s original publication, by W.E. Napier, in the Pittsburg Dispatch of 5 June 1905.

Teichmann had also visited Glasgow in 1901-02, for four months (BCM, February 1902, page 60), but Napier’s report of the communication from Teichmann indicates that the king-march game was played recently, i.e. in March 1905.

No publication of the game prior to 5 June 1905 has been found, and we wonder when the date 1902 was first proposed. An early instance in a book is the first edition of Edward [Eduard] Lasker’s Schachstrategie (Leipzig, 1911), pages 100-102:

As mentioned in C.N. 7933, Beratende is a German word for consultants/allies. In Lasker’s final note, a move by the black queen to c5 (QB4), and not f5 (KB4), was evidently meant. The move order given by Lasker included the sequence 28 Kh2, 29 Kg3 and 30 Kh4, as in the Pachman book but also, strange to say, as in item 114 of Unit Two of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1934), which, moreover, had the date 1902. See too pages 167-168 of Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess by W.E. Napier (New York, 1957 and 1971).

(10798)

C.N. 1985 gave several simultaneous games by Pillsbury from pages 342, 343, 345 and 390 of the American Chess Magazine, February and March 1899, including this one:

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (blindfold) – T.B. Lyman

Washington, 8 February 1899

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ng5 d5 6 exd5 Nf6 7 Nc3 Bg7 8 d4 Nh5 9 Bc4 Ng3 10 Bxf4 Qe7+ 11 Kd2 Nxh1 12 d6 cxd6 13 Bxf7+ Kd8 14 Nd5 Nf2 15 Qf1 Ne4+ 16 Kc1 Qf8 17 Nxe4 Bh6 18 Bg5+ Bxg5+ 19 hxg5 Kd7 20 Qf6 Kc6 21 Ne7+ Kb6 22 Qxd6+ Nc6 23 Nd5+ Ka5 24 Qc7+ Kb5 25 a4+ Kc4 26 c3 Be6 27 b3+ Kd3 28 Nc5+ Ke2 29 Nxe6 Black resigns.

A follow-up item (C.N. 2009):

Too late for inclusion in C.N 1985 it dawned upon us that Pillsbury missed a mate in three at move 25 of his game against Lyman (25 Ndc3+ Ka6 26 Bc4+ b5 27 Bxb5 mate). Now Salomon Levy (São Paulo, Brazil) has pointed out to us that, a move later, 26 Nd2+ would also mate faster, although he does not mention the quickest line, namely 26 Nd2+ Kxd4 27 Qf4+ Kc5 28 Nb3 mate.

Colin Crouch (Harrow Weald, England) has kindly confirmed these mates at our request, and adds:

‘27 Kc2, instead of 27 b3+, is another attractive forced mate. White is threatening 28 Ne3 mate, and if 27...Bxd5 28 b3 mate or 27...Kxd5 28 Nf6+ Kc4 29 b3 mate.

28 Qg3+, instead of 28 Nc5+, is the last forced mate: 28...Kxe4 29 Qe3+ Kxd5 (or 29...Kf5 30 Qf4 mate) 30 Qxe6 mate.

Some of the mating positions are quite intricate, indeed almost problem-like, but one feels sure that Pillsbury would have found them easily enough in a normal tournament game, so while Pillsbury’s blindfold exploits are remarkable, there is still some loss of clarity of thought in playing in such a way.’

(See pages 68-71 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.)

Below is Colin Crouch’s full letter (22 October 1993), written in response to ours (which included a word of appreciation for a spoof which he had contributed to Kingpin):

Addition on 27 August 2023:

Pages 98-99 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975) give a victory by the Cuban against G. Ravinsky (Leningrad, 24 March 1935) in ‘the toughest clock-simultaneous display of all time.’ At move 41 the Cuban began ‘a unique long march with his king in order to guard his pawn at QR4. He does not play P-QN3, which would block a way for his pieces ...’

Here Capablanca played eight consecutive moves with his king: 41 Kg2 Kd7 42 Kf2 Qe7 43 Ke1 Kc8 44 Kd2 Rd7 45 Kc1 Rdd8 46 Kb1 Rdg8 47 Ka2 Qd8 48 Ka3

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.