Edward Winter

(1989, with additions)

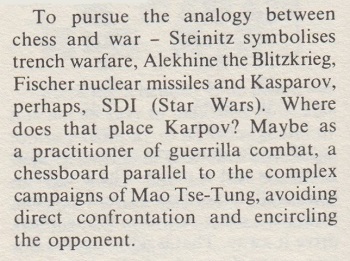

Hot off the

photocopying machine ... The caption in Kingpin

for this illustration was: ‘How to write a chess book: a

“manuscript” page from Warriors of the Mind,

which was cobbled together from Times and Spectator

columns.’ (See pages 215-216 of Warriors of the Mind.)

On page 43 of the February 1989 issue of the Canadian magazine En Passant, Dr Nathan Divinsky claimed that Magnús Smith and Colonel Moreau were ‘borderline cases’ for the award of a posthumous Grandmaster title. For that and various self-evident reasons, we were not expecting to enjoy Warriors of the Mind by Raymond Keene and Nathan Divinsky (Hardinge Simpole, Brighton, 1989), though we still hoped we would. Alas, expectation soundly defeated hope. Subtitled ‘A Quest for the Supreme Genius of the Chess Board’, Warriors of the Mind hazards a guess at the best 64 players of all time (including Szabó, Furman, Kholmov and Hort but not Réti, Spielmann or Tartakower), calculates most (not all) of the results between them, juggles the figures and then proclaims that ‘the strongest chessplayer of all time’ is Garry Kasparov. Elo ratings were considered good enough (more or less – page 13 admits that the selection process was arbitrary) for picking the 64 candidates – one for each square of the board, as if anybody cared – but not for deciding Number One. That results from a series of complex weighting operations, one reason being that ‘when we talk of the strength of some old time champion, like Wilhelm Steinitz, we mean his strength, today, [sic] after he has had some time for further study, to absorb the theory and knowledge that was developed after his time’ (page 4). Not that this has been properly taken into account in the picking of the 64. One might in any case ask on what basis it is assumed that each generation has built on its predecessors, at least in the present century. Most master games are won or lost in the middlegame; what precise scientific advances have been made in that phase of the game since, let us say, the 1930s?

Page 1 warns that ‘we should divest ourselves, as much as possible, of any pre-conceived ideas or prejudices. For example certain names are quite famous because of the books they wrote rather than the level of their play, names like Nimzowitsch, Tartakower, Tarrasch and even Alekhine.’ That is worth comparing with another page one, page 1 of Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal, in which Raymond Keene described Nimzowitsch as ‘one of the world’s leading Grandmasters for a period extending over a quarter of a century, and for some of that time he was the obvious challenger for the world championship’. Now, however, he knows better; Nimzowitsch just scrapes into the top 50. Nor will everyone be able to divest himself of the preconceived idea or prejudice that Alekhine (Kasparov’s hero, so Raymond Keene never used to tire of telling us) was one of the all-time greats, but the co-authors are having to pave the way for the shock revelation on page 323: Alekhine comes only 18th in the list of the best players in chess history. Alas, the book ignores the fact that although Alekhine had to play the best while they were at their best, Kasparov has not, except in the case of Karpov. From Kasparov’s record against the 22 players listed in Warriors of the Mind, it should be noted that only Short, Yusupov and Seirawan can be called contemporaries. On average, the other 19 are well over a quarter of a century older. Thus Kasparov’s figures include a dazzling 100% record (+1 –0 =0) against Najdorf, who is old enough to be Kasparov’s great-grandfather. Another half-dozen could be his grandfather. This is said not to decry the world champion’s chess genius, but to emphasize the absurdity of such statistical comparisons.

Page 15 lets another cat out of the bag. Concerning the Kasparov-Short games played at 25 minutes per side, it is disclosed that ‘we did not include them, but in principle we see no objection’. ‘No objection’, the authors are admitting, to throwing 25-minute games into the pot with world championship match games. While pondering whether they therefore see any objection to including Capablanca’s 1914 lightning match victory over Lasker, the co-authors would do well to sort out their policy on exhibition games (see the faulty Capablanca v Bernstein totals on page 75 and page 94).

Then comes the biggest part of the book, the ‘biographies’ and games by the lucky 64. A quote from page 23 about Steinitz (died 1900) is irresistible: ‘One traditionally pictures Steinitz struggling in the trenches. His chess seems almost a symbolic portent of the conflict of the Great War 1914-1918.’ That’s a deep one. Nothing is dealt with in detail or with care. Alekhine’s birth-date is wrong, as is Capablanca’s death-date. The Lasker-Janowsky match in Paris is still incorrectly called a world championship encounter; Capablanca is still falsely accused of demanding money in gold in 1922 as part of the London Rules; New York, 1927 is still being described as possibly having been a Candidates’ event (of which there is no question at all). That is the trouble with scissors-and-paste books: what a writer got wrong before he will get wrong for ever more. Seirawan’s ‘biography’ (pages 278-279) is lifted lock, stock and barrel from page 53 of Raymond Keene’s notorious Docklands Encounter, with the sole exception that ‘my feeling’ has been changed to ‘our feeling’. As noted in C.N. 904, Docklands Encounter asserted that Seirawan was ‘born in England’ (instead of Damascus). Warriors of the Mind naturally repeats the gaffe.

Page 43 of the book remarks that in view of his record Lasker ‘has claims to being the greatest world champion of the thirteen’ (cf. ‘Kasparov, the most successful world champion chess has ever seen’ – Raymond Keene, The Times, 29 April 1989, page 41). Schlechter receives three times as much space as Marshall, though the book claims they were roughly the same strength. Důras ‘appears to have been a real coffee-house player’ (page 78). Rubinstein died in ‘an old peoples’ [sic] home’ (page 82). Page 115: faulty German in the title of an Alekhine book. Page 119 and page 341 refer to a magazine which will be news to one and all: ‘Tijdschrift van den Nederlandsch-Indischen [sic] Schaakbond’. We can be sure that such misinformation was not supplied by the Rob Veerhouven [sic] mentioned on page 68. [In C.N. 1872 Jeremy Gaige pointed out that a magazine entitled Tijdschrift van den Nederlandsch-Indischen Schaakbond did exist. It was published in Indonesia.] Page 128: Harry Golombek’s book was not called 1948 World Championship. Nor was it published by the ‘British Chess magazine’ [sic] but by Bell (the BCM merely did a reprint decades later). Pages could be filled with a detailed catalogue of the book’s defects as it stumbles along with superficially annotated Famous Games, ending up with Short-Ljubojević, Amsterdam, 1988. Here the annotations are lifted, unacknowledged, from The Spectator of 19 March 1988 (page 52) though there are minor variations; thus The Spectator referred to the position after Black’s 27th move as being ‘a unique occurence’ [sic]. For Warriors of the Mind the spelling hasn’t been corrected, of course, but a deft nuance has been introduced: now it is ‘An almost unique occurence’ [sic].

By then we are at the concluding mathematical section. The authors’ (inaccurate) research yielded 10,148 game results with the following top percentage scores: 1 Morphy, 2 Lasker, 3 Capablanca, 4 Fischer, 5 Kasparov, 6 Alekhine, 7 Karpov. But now, they say, amendments have to be made to take account of 1) ‘opposition strength’, 2) ‘era effect’ and 3) ‘career span’. On criteria 2 and 3, at least, one would expect Capablanca, to name but one, to surge ahead, not least because the table on pages 313-314 shows the Cuban with a better record than Kasparov (more wins, fewer draws and fewer losses). Nor could he expect to lose out on criterion 1, because, as we now know, direct comparisons of Elo ratings between generations are unreliable, and the figures favour the moderns. But it is not to be. One way or another, Kasparov and Karpov are brought out on top, and Botvinnik is left looking silly for having said on page 257, ‘Of course, I consider Capablanca a greater player, a bigger talent [than Karpov].’ Page 313 reveals who were the ‘winningest’ [sic] players. Page 325 says that ‘apart from Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine, Rubinstein was clearly the genius of his age’; the co-authors have evidently forgotten that just two pages earlier the same Rubinstein was cast off as the 44th greatest player of all time, just behind Hort. On page 331 we learn that The Hague 1948 [sic – no mention of the Moscow half of the event) was the stongest [sic] tournament ever. Page 336 explains that the calculations would have held good if Tartakei [sic] had been included in the 64 top players. The book finishes with a blunder-ridden bibliography, which advertises not only an inordinate number of Raymond Keene’s own books but also such literary phantasms as ‘Selected Games of Paul Keres’ [sic], 3 volumes, by Keres and Alexander [sic].

The dust-jacket calls Warriors of the Mind ‘a seminal work written by two scholars of the game’. In reality it is swill.

(1853)

From page 234:

From Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA):

‘Anyone who loves chess and who respects those players who truly deserve to be called great should welcome the review of Warriors of the Mind in C.N. issue 44. The book deserves the negative opinion which concludes the review. I’ve also seen it described especially well by this adjective: “appalling”.

But this book merits further “distinction”. I call it the worst chess book ever printed.

There are worse ones for reasons such as poor production or lack of information. And I wouldn’t call it the worst just because of its typographical errors and its errors of fact, as are fairly criticized by the review. However ...

This is the first chess book that can actually be described as evil. Reasons fall into two categories:

1. Muddled gobbledegook, masquerading as a sound mathematical system for the ranking of players, is unfairly used in an attempt to damage the reputations of the greatest players of the past.

2. The questionable motives of the authors have a political and commercial foundation; there is conflict of interest, right from the dedication (“This book is dedicated to Bessel Kok and all members of the Grandmaster Association”) on through its final and probably predetermined conclusion (“Garry Kasparov is the greatest chess player that ever lived!”).

The mathematical system is riddled with holes. Sixty-four players were more or less selected because they had “2600” elo ratings. Actually some were put in who had lower ratings. Others with similar ratings were left out. And in all cases these elo ratings were only calculated for five-year periods, yet the book’s rankings are based on lifetime results of games played among the 64, without considering age differences of the players or relative seriousness of the competitions.

In the June 1985 BCM one of the authors, Nathan Divinsky, wrote an article in which he tried to prove that von der Lasa was the first player to get a 2600 rating. Von der Lasa not only isn’t one of the 64, he’s not even mentioned.

Neither is Louis Paulsen, who in three matches with Anderssen had two wins and a tie. So that didn’t hurt Anderssen’s ranking but neither was it helped by excluding his best result, winning at London, 1851. Anderssen’s ranking for all time is therefore based on how he did against only four players: Zukertort, Steinitz, Morphy and Blackburne.

That’s more than in Morphy’s case. His only rated games are 11 versus Anderssen.

I don’t say Morphy shouldn’t be in the 64. But what about having left out Réti, Spielmann, Tartakower and Grünfeld? That’s not just a question of being unfair to them, it means that in this system no-one (such as Alekhine, ranked here No. 18) gets credit for beating them, while Kasparov is rewarded for having scored against Beliavsky, Hübner, Vaganian, Yusupov and Short.

The book’s “explanation” of its ranking system has a dizzying series of tables. Ranking orders change; revisions are made as they go along. When things didn’t look right, they reduced some “strength numbers” by 7% and others by 10% – and increased some by 5%. In this they confess (page 322): “Dealing with this career span problem is known as massaging one’s material!”

That goes along with another admission (page 316) of how they scientifically arrived at the “strength numbers” which were vital to their formulae: “... we bring in the monster computer to actually solve this large system of equations – this is done by a sequence of iterations (repeated intelligent guesses [sic!]) until we have the values ...”

On page 318 they solve what they call their “era effect flaw” (meaning they were embarrassed by a system that was indicating that Vaganian was stronger than Lasker, and Polugayevsky was stronger than Capablanca) with a page-wide mathematical formula which not one chessplayer in ten thousand will remotely comprehend. They know that; they then say (page 318), “Readers who wish to know more about the details of this, may have to wait because this will be published as a research paper ...”

Those who dislike Alekhine might not mind that he is ranked No. 18. But who except the most inexperienced players can avoid a shudder when they see Rubinstein, Steinitz, Nimzowitsch, Tarrasch, Pillsbury, Schlechter and Chigorin all rated lower than Hort, Hübner, Gligorić, Szabó, Vaganian, Furman, Beliavsky, Averbakh, Kholmov and Sokolov? If you agree with me that this is simply wrong, then you should see that such error at the bottom of their list is a natural consequence of deliberate error at its top.

It must have pained the authors to rank Karpov as No. 2 of all time (as it will pain Fischer fans to see Fischer in third place). But they had little choice. When these calculations were made, Karpov had won a lot more tournaments than Kasparov, and Kasparov was ahead of him only 50½ to 49½ in their personal confrontations. It would have been impossible to rank Karpov any lower while calling Kasparov “the greatest chess player that ever lived”.

As for my allegation that there is conflict of interest for Kasparov to be so designated in this book, that should be self-evident to many people – after all of the media attention given to chess politics in the past five years – but I have to back it up.

Author Raymond Keene became Kasparov’s political ally in 1985. They were the main critics of Campomanes, and they have continued to be, in spite of the failure of their joint effort to take over FIDE in 1986. Author Divinsky joined Keene’s anti-Campomanes and pro-Kasparov campaign when he went to London for the 1986 Karpov v Kasparov match, giving his biased opinions on London television. Keene also has had commercial links with Kasparov (publishing of his books by Batsford and presenting him with his English agent, A. Page). Note the dedication of this book: Kasparov is President of the GMA. Then there are those thanked for “contribution of valuable ideas”: Larry Parr, who as Chess Life editor was the most rabid Campomanes critic and Kasparov supporter, and Kevin O’Connell, business associate of David Levy (Keene’s brother-in-law and manager of his 1986 anti-Campomanes campaign). Even one of the publishers of this book, Julian Simpole (thanked for “constant encouragement”), is more involved than as publisher: he’s Secretary of “The English Chess Association”, an organization set up by Keene when he had a falling-out with FIDE and the BCF (leaving his positions in both). Considering all that, what could be done by this group except to make Kasparov (Campomanes’ big headache) “the greatest that ever lived”? Politics placed before Alekhine, Capablanca, Lasker, Tal ...’

If any C.N. reader would like to defend or compliment this book, the space awaits.

(1871)

Regarding Warriors of the Mind, C.N. 1871 concluded: ‘If any C.N. reader would like to defend or compliment this book, the space awaits.’ Two readers, W.D. Rubinstein (Victoria, Australia) and Ronald Pearce (Wroughton, England), have responded.

From Professor Rubinstein:

‘While I am in almost total agreement with both you and Hugh Myers on the merits of Warriors of the Mind in its approach to ranking the greatest players, the book does have one valuable feature which should probably be noted, namely the information it provides on the lifetime scores of the greatest players against one another. This information, except for some world champions, is surprisingly difficult to obtain. If one wants to know, for instance, how Spielmann performed against Tartakower, the only source known to me that will provide this information is Professor Divinsky’s Around the Chess World in 80 Years. If one wishes to know where and when Spielmann beat Tartakower, or vice versa, there is no source that will tell you. One could plow through Gaige’s Crosstables for tournaments but only through 1930, supplemented by Feenstra Kuiper’s work on matches (incomplete, and ending around 1951). For recent players, say Smyslov’s lifetime score against Gligorić, there was, similarly, no work that will provide this information until Warriors of the Mind, and no work that gives the places, dates and game-scores. There is an obvious major gap here in chess reference works waiting for someone to fill.

Although Warriors of the Mind provides some of this valuable information, however, I am in complete agreement that it fails on virtually every count as a convincing analysis of chess ability. This can be shown by the merest comparison of Warriors of the Mind with Professor Elo’s The Rating of Chess Players Past and Present. In contrast to the tendentious special pleading of Warriors of the Mind, Elo’s work, and the rating system behind it, is obviously superior in every way, containing no element of biased selection (all games by rated players are included), one formula for all ratings, and lifetime ratings that are far more plausible (Fischer’s peak is 2780, Kasparov c 2750 over three years, Capablanca 2725, Alekhine 2690, etc.) and extraordinarily consistent by age-specific performance across the careers of leading players.’

Whilst agreeing with Professor Rubinstein’s point about the unavailability of lifetime scores, we cannot, even in this domain, regard Warriors of the Mind as a step forward because its tables are inaccurate and incomplete. Nor does the work make clear in each case the kinds of events that have been included or omitted. As Tartakower and Spielmann are both absent from the book’s chosen 64, let us take the other pair mentioned by Professor Rubinstein: Smyslov and Gligorić (‘+5 –7 =21’). Since there is no information about when (i.e. when exactly in 1987) the cut-off date was for these and other modern players, how can we verify or update the statistics?

From Ronald Pearce:

‘I should like to comment on C.N. 1871 and Mr Myers’ views on Warriors of the Mind, but only in respect of the remarks about the mathematical methods used.

The purpose of this book is to compare the strengths of players over lengthy periods. As in any statistical examination of performances of this sort, mathematical models have to be set up and their conclusions examined. It seems to be unacceptable to Mr Myers that the authors change their approach in the course of the investigation. A statistical approach works like that, and if Mr Myers is so troubled by “a dizzying series of equations” (page 58, paragraph 2), then he really should not be commenting on a subject with which he is clearly not au fait. In the same way, Mr Myers opens himself to ridicule by quoting Divinsky’s “repeated intelligent guesses” and adding “(sic)” to show his contempt. The reference is to solution by iteration, and the method goes back at least to Isaac Newton.

Perhaps I may offer the simple analogy of a weighing machine. Supposing I step upon a hospital weighing machine – the sort where small weights are added to, or subtracted from, an arm until the scale balances. The method is simple, but an “entering value” is needed. The nurse could “enter” with 3 kg. or 300 kg., but these values are not likely to be near the true weight and would waste time. She would either read my last weight recorded in the notes, or estimate from my appearance, or ask for my normal weight. These would be three versions of the “intelligent guess”, and the simple procedure of adding and subtracting would quickly give the correct result.

In solution by iteration, the equation itself functions rather like the weighing machine. The “guess” value is fed through the equation, and an output value results. This output value is reprocessed by the equation, until eventually input and output values coincide and the equation is solved. It is therefore quite wrong to ridicule Divinsky’s mathematical approach. Mr Myers would be on firmer ground if he confined his criticisms to matters such as selection of subjects, weighting of data, etc., which are clearly open to debate.’

Hugh Myers replies:

‘First, I don’t like being misquoted. I said “a dizzying series of tables”, not “a dizzying series of equations”. The tables are lists of players in ranking orders. I was saying that these associates of G. Kasparov kept revising tables until their version of “cream” (Kasparov) rose to the top, not “until the equation was solved”.

“Solved”. What was solved? What sort of solution could it be to say that Alekhine is number 18 and that Nimzowitsch is ranked 30 places below Sokolov?

Mr Pearce says that I shouldn’t comment on subjects with which I’m “clearly not au fait”, and that I’ve “opened myself to ridicule”. All because I put “(sic)” after “guesses”? I don’t see what else there is in the article that enables Mr Pearce to deduce my knowledge of the subject, and then to conclude I have no right to comment on it.

He’s right that my “(sic)” shows contempt. I won’t be bothered if that “(sic)” results in “ridicule”, considering where it’s coming from. Mathematicians are the most elitist people I know, cloaking themselves in esoteric formulae, like medieval alchemists and their spells.

I don’t mind that as long as they don’t pretend that their perfect equation-solving methods always produce incontrovertible solutions. But I already had personal experience (nasty letters from Arpad Elo) with how mathematicians react to what they imagine to be criticism of mathematics itself. They believe so strongly in the purity of numbers that they overlook common sense. What enraged Elo was that I detailed the flaws of his system in issues 35 and 36 of the Myers Openings Bulletin. Games were being rated as if they were all the same. They are not. There are differences in time controls, seriousness of the competitions, and playing conditions. It makes a difference if the player knew or didn’t know that the game would be rated. A game from a two-player match shouldn’t be rated the same as a tournament game; depending on match conditions, a draw may or may not affect the result of the match, and when it doesn’t, it shows little about the players’ playing strengths.

These problems with rating were compounded in Warriors of the Mind. Players were rated on how they scored against others in a 64-player list, but there are wide variances in too many factors: number of opponents in the list, number of rated games, and the relative percentages. One player’s rated games are all from one year; those of others are spread over decades. A game played at age 20 is rated like another one played at 65. Worst of all is that a player can be rated “for all time” on only a small percentage of the games he played in serious competition. That defect was the inevitable consequence of exclusion from the list of many outstanding pre-1940 players.

As for “iterations”, saying that they go back to Isaac Newton doesn’t carry much more weight than to say that belief in a flat Earth goes back thousands of years. But I don’t dispute the occasional practicality of such employment of trial and error. My “(sic)” expressed contempt for utilization of “repeated intelligent guesses” when they are based on inadequate or flawed data, when they purport to give exact ranking of players (not placing them in categories, but putting them in specific relative positions, thereby affecting the reputations of players both living and dead), and where there is evidence of ulterior motive (the ranking of Kasparov as “the greatest of all time” by people with whom he has had political and commercial alliance).

With regard to W.D. Rubinstein, I don’t think there is much argument here (except for my hearty disagreement with his high opinion of Elo’s rating system, but that’s another matter). Professor Rubinstein is saying that lack of current published records of lifetime results between particular players is a gap that needs to be filled, not that those in Warriors of the Mind are entirely accurate. I can accept that those records are the “best” feature of Warriors of the Mind (hardly anything is all bad); knowing Mr Keene’s track record for historical accuracy (or lack of it), those statistics should be taken with a grain of salt, but certainly they are better than nothing for someone who is curious about them. Let’s hope that similar work will be undertaken by someone who has knowledge and integrity.’

Professor Rubinstein and Mr Pearce informed us that they did not wish to add any further comments.

(1929)

As reported on page 141 of A Chess Omnibus, in 1999 the co-publisher of Warriors of the Mind, Julian Hardinge, dismissed our review as ‘an apoplectic catalogue of the typographical errors in the book’. In 2002 his company re-issued the tome. Although two extra pages were found for some puffery, textual corrections were not made, and the innumerable gaffes were allowed to stand. ‘Tartakei’ remained ‘Tartakei’.

Warriors of the Mind was discussed in an article entitled ‘Ex Acton ad Astra’ on pages 18-33 of the Spring 2007 issue of Kingpin. The magazine’s Editor kindly allowed us to reproduce an illustration from page 31 (given at the start of the present article).

The full text of the above-mentioned item on pages 141-142 of A Chess Omnibus:

Grandmaster Strategy by ‘Raymond Keene OBE International Chess Grandmaster’ (Trowbridge – or North Korea?, 1999) contains a foreword by Julian Hardinge which asserts that a Keene book that he co-published ten years ago, Warriors of the Mind, was ‘well received’ except by a few ‘sworn enemies’. We are singled out for having written ‘the most ferocious review’, which is dismissed as ‘an apoplectic catalogue of the typographical errors in the book’.

Anybody who has seen that review will know that it dealt with far more than the book’s teeming typos. Moreover, even the BCM (which, on Keene issues, has been a sworn poodle) published a distinctly unfavourable critique (May 1989 issue, page 197) ending with the words ‘“Back to the drawing board”, must be the verdict.’

It is nonetheless true that Warriors of the Mind was extolled by isolated individuals. On page 267 of the June 1989 BCM K. Whyld wrote in his ‘Quotes and Queries’ column: ‘This book must be a strong candidate for the Chess Notes book of the year prize.’ (As far as we recall, it failed to score at all.)

Over the years, hundreds of falsities from Mr Keene’s pen have been logged publicly, without Julian Hardinge & Co. having ever attempted a rebuttal. Discovering praise for Mr Keene’s historical output is a challenge, yet not an impossible one. Here, for instance, is what appeared on page 20 of the August 1990 CHESS, in a review of Chess An Illustrated History:

‘Who better to provide a vivid picture of the broad sweep of chess history than Grandmaster Raymond Keene, who is alert to every development of our game?’

The writer: K. Whyld again.

(Kingpin, 1999)

In Edge, Morphy and Staunton we commented regarding K. Whyld:

At his best, he was one of the best; at his worst, he was one of the worst.

From the same feature article:

On 30 January 2004 Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) wrote to us:

‘As an aside on the Edge letters, I know that in one of your Chess Notes Whyld was quoted as calling Edge an outright liar for his comments on Staunton. My considered view is that at least Whyld, and possibly Hooper too, very deliberately started the Morphy homosexual rumor to besmirch Morphy. If you read all of Edge’s letters, I think you, or anyone else, would have to agree that there is no suggestion that they had any kind of homosexual relationship. That doesn’t prove that Morphy was not a homosexual, but why even ever bring it up unless there exists some evidence to support such a theory? Despite all the hoohaw about how great a student of the game’s history Whyld was, I still think he was extremely devious and I greatly distrust his judgments on many matters having to do with chess.

He often ill-concealed his bias.’

And on 1 February 2004:

‘Whyld repeatedly, in my experience, sought refuge in evasion and distortion when called upon to prove some of his assertions.’

An earlier comment by Dr Brandreth was in an e-mail message to us dated 3 August 2000:

‘I have never fully understood Whyld. With me he often just evades an issue or question. I suppose I am to be able to figure out what such non-responses mean, but I find that frustrating and inadequate.’

Dr Brandreth was the publisher of a book which K. Whyld edited: Reflections by David Hooper (Yorklyn, 2000).

A feature article about K. Whyld is Reliability Eroded.

‘I’m not good at attention to detail’, stated Mr Keene uncontroversially on page 17 of the November 1990 CHESS.

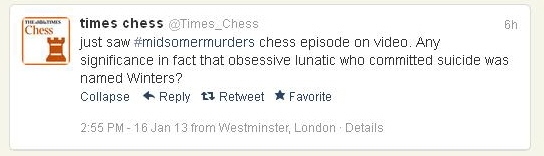

A Times tweet posted by Raymond Keene on 16 January 2013:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.