Edward Winter

It is impossible not to have misgivings, both general and particular, about Wikipedia, but we have recently noticed a great improvement in some of the chess articles in the site’s English-language version. There is, for instance, excellent treatment of G.H.D. Gossip, and it is also good to see a fine article on Hugh Myers.

(5919)

Both articles were written principally by Frederick S. Rhine.

Other examples of good Wikipedia articles are the ones on James A. Leonard and Leonard Barden.

A grotesque publishing innovation is a series of books which, self-confessedly, are no more than grab-bags of Wikipedia entries. Slim volumes on Capablanca and Lasker have just been in our hands, as briefly as possible.

Readers who visit amazon.com and enter ‘Alphascript’ for the publisher and ‘chess’ for the keyword will see that the adjective ‘grotesque’ also applies to the prices.

(6380)

C.N. 6380 referred to ‘a series of books which, self-confessedly, are no more than grab-bags of Wikipedia entries’. It is becoming increasingly common to find Wikipedia spit-outs, and the worst so far must surely be this:

Chess Webster’s Quotations, Facts and Phrases (251 pages) says that it was published by ICON Group International, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA (‘Copyright © 2008 by Philip M. Parker’), although it seems to have appeared only recently, as part of a large series on various subjects. The final page states: ‘Printed in Great Britain by Amazon.co.uk, Ltd., Marston Gate’.

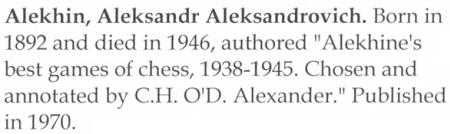

This calamitous volume comprises random snippets robotically slashed out of such sources as Webster’s Online Dictionary, Wikipedia and WordNet. During a 45-minute flick-through (self-imposed time-limit) we came upon such entries as this (page 44):

Similarly, page 57 says that Capablanca authored Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek, a book supposedly published in 1972.

Page 151 states that by the time Blackburne defeated Nimzowitsch at St Petersburg (the date 1914 is omitted) ‘he was concentrating on writing his chess column for “The Field”, a position he held up until his death in 1924 at the age of 82’. Blackburne has been muddled with Burn. Page 201 refers to ‘Joseph Henry Blackburne (1859-1951)’. Blackburne has been muddled with Blake. Page 199 offers, from WordNet, three-line entries for Karpov and Kasparov. Karpov’s entry gives the impression that Kasparov was born in 1951; Kasparov’s entry gives the impression that Karpov was born in 1963.

The mindless cut-and-paste (in a book which has no illustrations or diagrams) is apparent from an entry for ‘Novotny’ (from ‘WP’, i.e. Wikipedia) on page 158:

An entry for Fischer on page 138, also courtesy of Wikipedia, starts towards the end of an unidentified and unexplained quote:

In fact, any mention of ‘chess’ in Wikipedia et al. may result in an entry in this Webster book, as demonstrated by page 219:

The 22-page index has also been generated automatically, of course, and seems to contain entries for most words in the book which begin with a capital letter, including ‘Bob’, ‘Der’, ‘Foreword’, ‘Kasparows’, ‘Mes’,‘Miscellaneous’, ‘Mrs’, ‘Produced’, ‘Strange’ and ‘Tuesday’.

(6771)

The reference to the British Chess Club Handicap Tournament, in which Zukertort was participating at the time [of his death], is a reminder of how chess history suffers when Wikipedia entries make do with references to obviously sub-standard sources. The English-language page on Zukertort currently gives links to two articles by Bill Wall, one of which states:

‘He died on 20 June 1888 from cerebral stroke after a chess game during a tournament at Simpson’s Divan. At the time, he was in 1st place. He was scheduled to play Blackburne and Burn in the final two rounds.’

Burn was not even a participant in the tournament.

...

Instead of citing inept Internet articles, the Wikipedia entry on Zukertort would gain from using primary sources and the books written on him:

At present, not one of those works is even mentioned in the Wikipedia entry.

(8122)

Wikipedia removed the false information and added the book references.

‘[Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, London] also hosted the great tournaments of 1883 and 1899, and the first ever women’s international in 1897.’

C.N. 7892 provided documentary proof that all three events took place elsewhere, but the incorrect statement still appears on the Wikipedia page for Simpson’s-in-the-Strand.

(8123)

The inaccurate references were removed by Wikipedia.

Among the many chess oddities on the English-language Wikipedia site are a disproportionately long, though interesting, entry on Grace Alekhine and a Fischer-related page whose three-line section on My 61 Memorable Games ends:

‘Larry Evans originally thought it was possible that it was a pirated version of a genuine Fischer manuscript, but in April 2008 concluded it was a hoax.’

Mr Evans asserted that the 1995 Batsford edition of My 60 Memorable Games was better than the original (see Fischer’s Fury), and there can hardly be value in chronicling what such an individual may have originally thought was possible, or what he later concluded, about My 61 Memorable Games, a book which he never even saw.

Wikipedia frequently neglects figures in the problem world (e.g. A.C. White and P.H. Williams), and it is impossible not to comment slightingly on the thin entries for such masters as S. Alapin, O. Důras and R. Teichmann. On the Teichmann page the sole ‘Reference’ is the 1976 edition of Anne Sunnucks’ The Encyclopaedia of Chess.

There is even a Wikiquote page of chess quotes presented without any sources and obviously therefore needing to be re-started from scratch.

(8130)

Alain C. White now has a substantial article. The Wikiquote page has been transformed.

There has been, particularly of late, a steep decline in the quality of chess obituaries; many are dumped online after hurried copy-pasting. Often nowadays, people are wikipediaed into the grave.

(9346)

From Chess Thoughts:

When chess masters die, good writers go to their bookshelves. Bad writers go to Wikipedia.

To state the obvious, or what ought to be, great wariness is required over ‘community’ websites which, instead of trying to get matters correct from the outset, allow individuals, usually unnamed, to post whatever they choose. The onus is placed on others to try to make rectifications if they can be bothered.

In the particular case of Wikipedia, the quality of chess entries varies enormously (C.N. 5919 named two good ones, and there has been considerable overall improvement to the site since then). Discernment remains essential, and quoting Wikipedia is not a step to be taken lightly.

In C.N. 8110 (see Chess: the Need for Sources) a correspondent pointed out that in The Immortal Game by David Shenk (New York, 2006) ‘details of Spassky’s chess career are attributed to a Wikipedia entry’. Recent books with no qualms about citing Wikipedia include Miguel A. Sánchez’s volume on Capablanca (C.N. 9456); see pages 509 and 527. From the latter page:

‘According to Wikipedia ... But according to the more reliable version of Andy Soltis in ...’

McFarland books really should do better than that.

In Players and Pawns (C.N. 9500) the endnotes offered by Professor Gary Alan Fine include one on page 241 which gives a Wikipedia link combined with a reference to an atrocious book by Larry Evans, This Crazy World of Chess. On page 256 the Professor refers to Wikipedia for information about Claude Bloodgood.

On page 9 of Carlsen move by move (London, 2014) the vastly over-published Cyrus Lakdawala even quoted Wikipedia on matters of opinion:

‘Wikipedia says of Carlsen’s opening play: “He does not focus on opening preparation as much as other top players, and plays a variety of openings, making it harder for opponents to prepare against him.”’

The most glaring example found so far of a chess book’s lazy use of Wikipedia is on page 11 of Chess Openings for Dummies by James Eade (Hoboken, 2010):

‘According to Wikipedia, The Oxford Companion to Chess lists 1,327 named chess openings and variations.’

(9511)

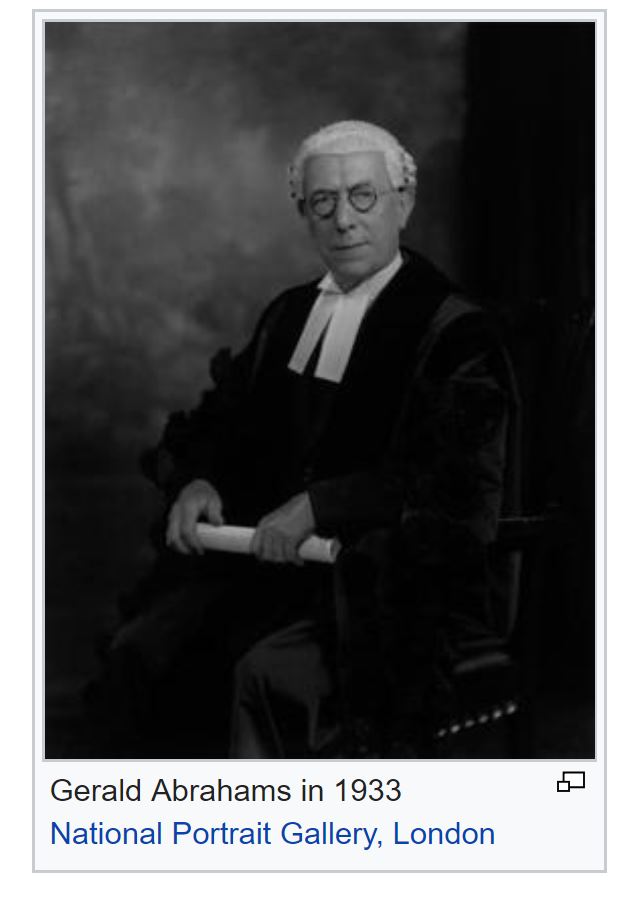

Sources [regarding The Termination] disagree about what Campomanes supposedly said and, for once, it is worth mentioning what Wikipedia states. Below is the text that currently appears in the English-language entry for Campomanes:

And in the Wikipedia entry on FIDE:

What role may have been played by Dlugy (who was aged 19 at the time of the Termination) is unclear, but in any case the words ascribed to Campomanes are completely different. Instead of ‘I told them exactly what you told me to tell them’, we now have ‘But Anatoly, I told them just what you said’ (Campomanes page) and ‘But Anatoly, I told them what you said’ (FIDE page). It remains to be discovered why such discrepancies exist.

(9580)

Olimpiu G. Urcan asks about an oft-seen claim concerning Mrs Fagan in India. Below, for example, is an extract from her entry on pages 129-130 of Indian Chess History 570 AD-2010 AD by Manuel Aaron and Vijay D. Pandit (Chennai, 2014):

‘In the spring of 1882 she was the only female in a 12-player knockout chess tournament in Bombay. Best of three, knockout matches were held. When the last three were reached, they played three-game matches against each other. Fagan won all her games, but was disqualified because she was a woman playing in a club whose membership was confined to men. She appealed this decision in court and won. The names of the other players are not known.’

The Fagan entry merely credits ‘Anthony Gillam and Wikipedia’. For the Bombay story, Wikipedia, in turn, merely credits a sourceless item by Bill Wall.

(9779)

The French edition of Wikipedia is one of many language versions which give (on both masters’ pages) the fake photograph of Alekhine and Capablanca:

(10010)

The photograph has been removed.

Concerning copying from Wikipedia by Philippe Dornbusch (over 430 words), about Capablanca, see C.N. 10009.

From Olimpiu G. Urcan:

‘Having bought a digital edition of the August 2017 BCM (“Editors: Milan Dinic and Shaun Taulbut”), I saw on pages 498-499 an unsigned article “Did F.D. Yates Kill Himself?”:

You are mentioned briefly near the beginning, but everything (all the facts, quotes, etc.) about Yates’ death in the entire article has been copied from your work, and without mention of your (active) feature article.

That leaves just the BCM’s general introductory paragraph on Yates’ career. It has been lifted from Wikipedia.

So more or less the only “contribution” by the BCM itself is a Wikipedia-sourced photograph of Emanuel Lasker. The magazine identifies him as “Edward Lasker”.’

(10538)

For further details, see our feature article on Yates.

From the English-language Wikipedia entry for Gerald Abrahams:

See too the National Portrait Gallery’s Gerald Abrahams page, which has a number of similar shots, all dated 21 August 1933.

At that time, Abrahams was aged 26.

(10985)

The matter was raised again in C.N. 12138.

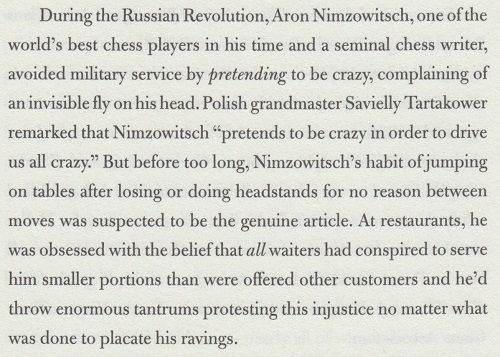

An extreme example of a chess book treating the leading players of the past without respect is The Grandmaster by Brin-Jonathan Butler (New York, 2018). From page 133, this is the sum total (Wikipedia-based, of course) of what the book offers on Nimzowitsch:

(11128)

Regarding Chess Problems, Play and Personalities by Barry Martin (Beddington, 2018).

... Pages 194-195 (the section on Leonard Barden) are little more

than pickings from his Wikipedia entry ...

(11186)

From the Wikipedia page on Rudolf Spielmann:

Spielmann’s forename and surname are misspelled in a dire Wikipedia article entitled ‘Romantic chess’ which includes, for instance, a reference to ‘the 1930s when hypermodernism began to become popular’.

(11422)

The faulty Spielmann quotation has been removed, but there is still a section of unsourced quotes. The Romantic chess entry has been improved, but the faulty 1930s reference remains.

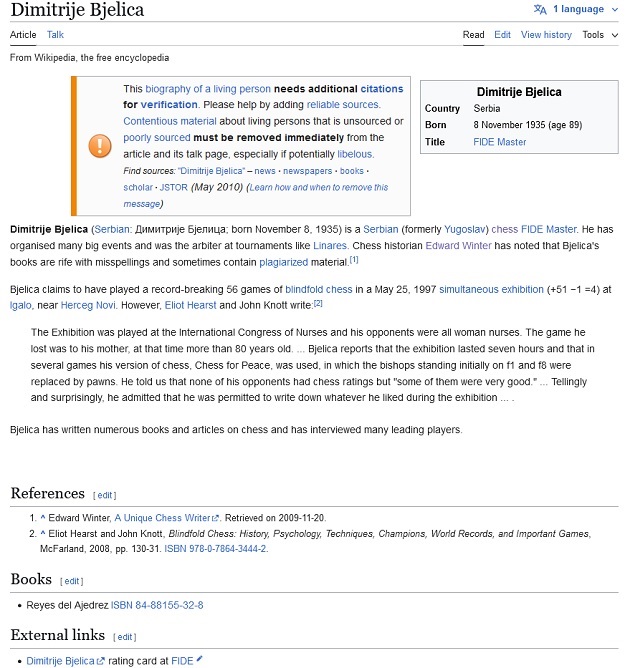

Following the reference to D. Bjelica in C.N. 11585, a look at his current Wikipedia entry seems timely:

Given the alleged existence of ‘over 80 books in 180 editions’, it is an act of mercy that (contrary to the Wikipedia articles on, for instance, Bruce Pandolfini and Eric Schiller) the entry eschews a list and mentions only one alleged volume. However, that solitary reference, ‘Reyes del Ajedrez ISBN 84-88155-32-8’, is worthless because Bjelica had a series of books published under the generic title ‘Reyes del ajedrez’; the ISBN number given – randomly, it seems – is for the volume on Botvinnik (Madrid, 1994).

The first paragraph also affirms that Bjelica was ‘the arbiter at tournaments like Linares’. Which tournaments are ‘like Linares’ is an open question, and, in any case, no substantiation for the alleged role is provided. There is, at least, a little something on page 177 of the May 1988 BCM, in a report on the sixth ‘Ciudad de Linares’ tournament: ‘the chief arbiter was Viktor Baturinsky, helped by Dimitrije Bjelica and Diego Martinez Linares.’

Still in the first paragraph of the Wikipedia entry, we contend that ‘contends’ is far too weak a word in connection with the rifeness of misspellings and plagiarism in Bjelica’s books. It is not a contention, but the expression of an incontrovertible fact. The first of the two ‘References’ on the Wikipedia page will take the reader to Jan Timman’s description of Bjelica: ‘a gutter journalist who wrote books that were full of printing errors and plagiarisms.’

The references to ‘Black Oscars’ (with and without quotation marks) and ‘White Oscars’ (without quotation marks) appear outmoded, incomplete, unsubstantiated and irrelevant. Awards involving Bjelica need to be treated with the utmost caution. None of the ‘External links’ leads anywhere of value. The ChessBase one relates to a 2004 article with much dubious wording identical to what is still in the Wikipedia entry for Bjelica even today.

According to the first paragraph of the entry, Bjelica (a ‘FIDE Master’ with very few published games) ‘can be found in the Guinness Book of Records for playing a 312-board simul in Subotica in 1997 (score: +219 −1 =92)’, with the implication that the alleged record is still valid today. In which edition or editions of that book can such a display be found, and on whose authority was it included? We lack almost all pre-2005 editions of the Guinness work, but can confirm that Bjelica is not mentioned in any edition from 2005 to 2020.

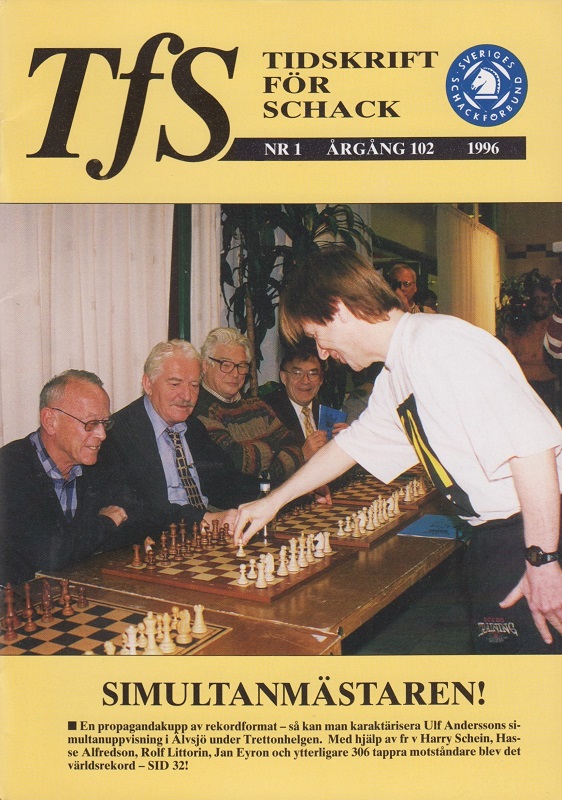

On that unspecified day in 1997 did the ‘FIDE Master’ really dethrone Ulf Andersson, who had (although his own Wikipedia entry does not mention it) played the previous year against 310 opponents simultaneously in Älvsjö, Sweden? On that performance an illustrated, documented report was published on pages 32-33 of the January 1996 issue of Tidskrift för Schack.

A basic search in Google Books shows that Bjelica was listed by Guinness in a number of editions in the 1980s, for an earlier alleged display:

‘Dimitrije Bjelica (Yugoslavia) played 301 opponents simultaneously (258 wins, 36 draws, 7 losses) in 9 hours on Sept. 18, 1982, at Sarajevo, Yugoslavia. Bjelica’s weight dropped by 4½ lb as he walked a total of 12.4 miles.’

Without demurral, that claim was presented as still being a record on page 132 of The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993), but on what grounds? Video coverage of record attempts today often shows a Guinness adjudicator, ascetically dressed, with a pair of severe glasses, an unforgiving stopwatch, and pen menacingly poised over clip-board, but was any such invigilator present in Sarajevo during Bjelica’s alleged display? And what proof or corroboration was published in reliable Yugoslav sources of the time?

Concerning any alleged exploit by Dimitrije Bjelica there is, at the very least, fog. Nowadays, Wikipedia has some excellent chess entries, but Bjelica’s is currently one of the worst.

(11591)

The Bjelica article has been cut down and improved out of all recognition:

Addition:

On 18 June 2025 Wikipedia’s pages on Bjelica (in English and Serbian) recorded his death, at the age of 89.

Dmitriy Komendenko (St Petersburg, Russia) notes that the Russian Wikipedia page for Maurice Benyovszky (1746-86) refers to his interest in chess and connection with Benjamin Franklin:

‘Во время пребывания в Париже Бенёвский увлёкся шахматами и на этой почве сблизился с американским посланником Бенджамином Франклином, который впоследствии принимал деятельное участие в воспитании его детей.’

Is further chess information available?

(11953)

From Chess: Mistaken Identity:

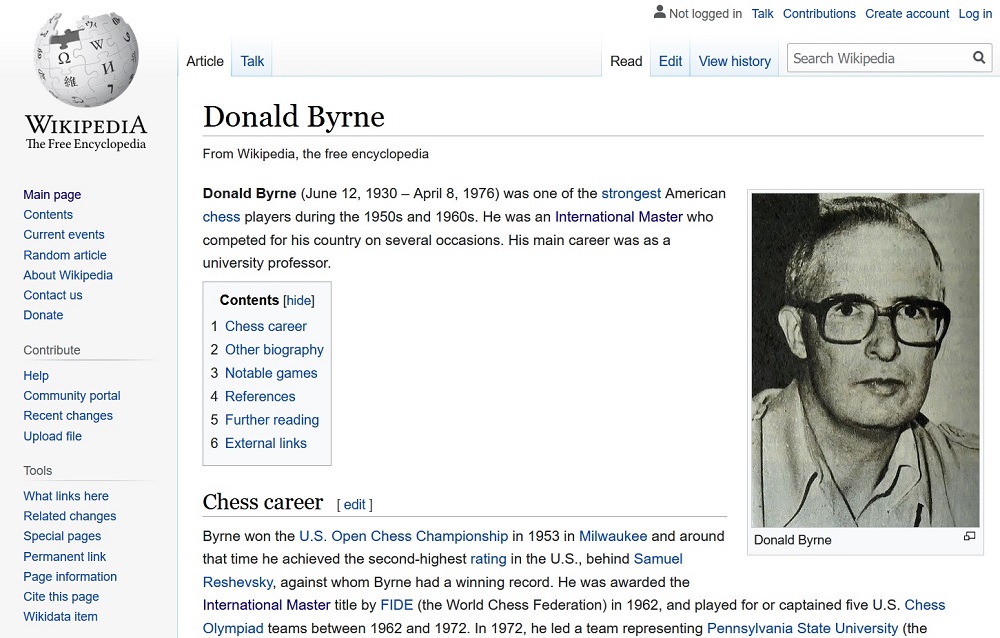

The start of the Wikipedia entry on Donald Byrne:

See also many of the other language versions of the D. Byrne entry listed on Wikipedia:

The photograph is, of course, of Donald Byrne’s brother, Robert.

All the language versions were subsequently corrected.

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) draws our attention to Delia Monica Duca (born 1986):

‘She has the unique achievement of having solved in the World Chess Solving Championship (in 2006 and 2011, the second time as a member of the Romanian team – she has also solved in three European Championships) and represented Romania in the Miss Universe competition in 2012. Her Wikipedia entry says that she was “national champion in solving chess problems” in 2006, but as there are a number of much stronger solvers in Romania I suspect that may mean that she was the women’s champion.’

From our feature article on Brian Eley:

The Wikipedia article on Eley includes a link to a webpage stating that he died in Amsterdam on 6 April 2022. However, we note too a page about Eley’s ‘reported death’ on the Yorkshire Chess Association website.

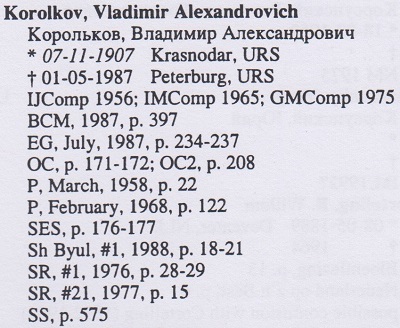

Chernev’s Chessboard Magic! (New York, 1943) gave nine studies by Korolkov (‘Korolikov’). The composer’s entry in the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

At present, Korolkov has no English-language Wikipedia entry.

(11640)

If we received a nominal sum every time a scanned image from chesshistory.com was misappropriated and viewed on YouTube, Wikipedia, X/Twitter, Facebook, chess.com, or other websites and outlets, we could single-handedly offer to fund future world championship matches.

(12034)

C.N.s 5706, 6972, 11074 and 11719 have discussed, inconclusively, J.W. Showalter’s year of birth. From C.N. 5706 (posted on 9 August 2008):

Kevin Marchese (Canal Winchester, OH, USA) informs us that he is writing a book on Jackson Whipps Showalter, with the assistance of some of the master’s relatives, and that the work will show that Showalter was born on 5 February 1859 (and not 5 February 1860, as previously believed). His exact place of birth still requires investigation.

Nothing much more has been made available to C.N., and it is unclear why the English-language Wikipedia article on Showalter and his World Chess Hall of Fame page state unequivocally and without evidence that he was born in 1859. The entry for Showalter in Jeremy Gaige’s 1994 edition of Chess Personalia is reproduced in C.N. 11719. It states that Showalter was born in Minerva, KY on 5 February 1860.

(12046)

C.N. 12046 continued with an examination of the issue by John Townsend (Wokingham, England). See also Jackson Whipps Showalter.

Nearly a decade ago, Nigel Short wrote in New in Chess about the differences between male and female chessplayers, and an outcry ensued, unhurriedly. If a journalist today seeks a reminder of the case, where to go? Should Google prove unhelpful, it may seem sensible to turn to a ‘standard’ source such as the Wikipedia entry on Short, but that fails too. It has 70 words on the affair and three endnotes, all three being links to ‘outcry’ articles by non-specialist writers in three UK newspapers, the Independent, the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph; all three articles, as it happens, were dated 20 April 2015. The New in Chess piece had been published about a month previously.

Wikipedia does not relate what Short had written in New in Chess, even though the full text was reproduced by ChessBase not long after the tumult began, and is still there. Nor does Wikipedia display awareness of Short’s follow-up article in New in Chess, which was, in part, a reply to the assertions in the three UK newspapers. The media had gorged themselves and, in terms of actual arguments, the second New in Chess article was, so to speak, even more ignored than the first one. Vive l’indifférence.

(12060)

From Alan Slomson (Leeds, England):

‘In relation to your comments in C.N. 12060 about the inadequate Wikipedia entry about Nigel Short, it is worth noting that “Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia, created and edited by volunteers around the world and hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation” as it describes itself.

Anyone can edit Wikipedia entries. If the accuracy of Wikipedia is a matter of concern, it is up to the community of chess historians to improve entries relating to chess history when they are felt to be inaccurate or inadequate.’

As regards the English-language entries on chess, there is a Wikipedia project page.

(12063)

Wanted: more detailed local (i.e. Breslau/Wrocław) information about Marshall’s ‘Gold Coins’ Game, and also about the loser.

Other games where a queen moves to KKt6 (i.e. g6 or g3) are discussed in The Fox Enigma.

Frank James Marshall by Frederick Orrett (see C.N. 9722)

Regarding the alleged gold coins episode, the English-language Wikipedia page on the game currently cites, of all things, a 2006 book published by Cardoza:

‘Eric Schiller wrote, “others say they were just paying off their wagers”.’

C.N. 12063 referred to the existence of a Wikipedia project group created to ‘improve information on chess-related articles’. The project group states:

‘Print sources are generally considered reliable, but certain authors such as Eric Schiller and Raymond Keene have a reputation for unreliability.’

(12129)

Recent C.N. items referring to Wikipedia are a reminder that its entry on the chess term skewer does not currently name the man who coined it, Edgar Pennell.

(12130)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.