Edward Winter

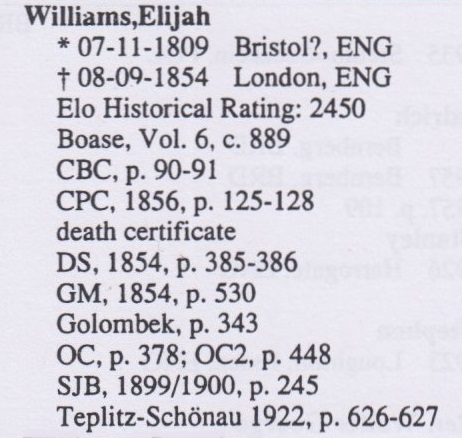

From the privately distributed 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

***

A prominent chessplayer who succumbed to cholera was Elijah Williams. To quote R.N. Coles on page 299 of the September 1954 BCM:

‘The summer of 1854 in London was overshadowed by a great epidemic of cholera, which out of a population of two-and-a-quarter million claimed over 3,000 deaths a week. The well-known chess master Elijah Williams, himself a doctor, was actually playing in the Divan one day in September when the disease attacked him ...’

It may be mentioned in passing that the entry on Williams in Harry Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977 and Harmondsworth, 1981) duly recorded that he died in 1854 but carelessly suggested that he was still writing his chess column in The Field three years later.

In the chapter ‘Ahead of Their Time’ in The Chess Companion (New York, 1968) Irving Chernev declared himself intrigued by Williams’ performance at London, 1851. From page 184:

‘Was his prolonged thinking part of a plan to infuriate his opponents? Or was it because he was slowly evolving a new system of play?

The terms “Double Pawn Complex” and “Zugzwang” could have had no meaning for Williams, but here, in two games [against Löwenthal and Staunton], we have this Nimzowitsch of a hundred years ago demonstrating these concepts.’

Chernev’s item originally appeared as an article on page 340 of the November 1955 Chess Review. We wonder if other writers have attempted to back up his theory, although nothing particularly helpful has yet been found by us in Williams’ book Horæ Divanianæ (London, 1852) or in other sources.

(3764)

Regarding the seesaw, or windmill, manoeuvre, the earliest instance of the word ‘seesaw’ found so far appeared on page 251 of the American Chess Magazine, September 1897:

‘A pretty so-called seesaw of checks finishes the game ...’

John Simpson (Oxford, England), the Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, notes an earlier, different, use of the term on page 263 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1849:

‘This see-saw is pretty enough. White evidently must not accept the proffered donum.’

The proffered donum was the black rook, the note being appended to Black’s 38th move. The full game, from pages 262-263 of the Chronicle, was:

Henry Edward Bird – Elijah Williams1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 exd5 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 Bd3 Bd6 6 O-O O-O 7 c3 Ne4 8 Nbd2 f5 9 c4 c6 10 cxd5 cxd5 11 Qb3 Kh8 12 Qc2 Nc6 13 a3 h6 14 b4 a6 15 Nb3 Qf6 16 Bb2 g5 17 Nfd2 g4 18 f4 gxf3 19 Rxf3 Qh4 20 Rh3 Qg5 21 Re1 Rg8 22 Nf3 Qg7 23 Ne5 Bxe5 24 dxe5 Be6 25 Bc1 f4 26 Rh4 Raf8 27 Bxf4 Ng5 28 Kh1 Ne7 29 Nd4 Bf7 30 e6 Bg6 31 Bxg6 Qxg6 32 Qxg6 Rxg6 33 Bxg5 Rxg5 34 Rxh6+ Kg7 35 Rh3 Re5 36 Rg3+ Ng6

37 Rc1 Rc8 38 Rf1 Rf8 39 Kg1 Rxf1+ 40 Kxf1 Re4 41 e7 Kf7 42 Nf5 Rf4+ 43 Rf3 b6 44 Kf2 a5 45 bxa5 bxa5 46 Kg3 Rxf3+ 47 Kxf3 Ne5+ 48 Ke3 Nc4+ 49 Kd4 Nxa3 50 Kxd5 Nb5 51 Nd6+ Nxd6 52 Kxd6 Ke8 53 Kc5 and White won.

(5853)

A famous Staunton position, from his eighth match-game against Elijah Williams, London, 1851:

Staunton (White) played 14 Bxf6 Qxf6 15 cxd5 exd5 16 d4.

On page 155 of Better Chess (London, 1997) William Hartston wrote after 16 d4:

‘Envisaging this pawn move, White first exchanged his black-squared bishop to ensure that it would not become bad (though it was another 50 years before anyone came up with the concept of a “bad bishop”).’

When were the concept and the term ‘bad bishop’ first recorded in print?

(7769)

Regarding the ‘bad bishop’ question, see C.N.s 10844 and 11048.

Part of an article by G.H. Diggle originally published in Newsflash, April 1981 and given on page 67 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess matches have often been abandoned half-way through by demoralized combatants after successive wins have been piled up against them; Harrwitz v Morphy and Kostić v Capablanca are notable examples. Dr Hübner’s recent resignation to Korchnoi is a more unusual case, as he was only potentially 4-6 down with six games to play. In 1851, however, there were two similar match resignations caused (as in Hübner’s case) by stress, though in both cases the stress was not due so much to “world publicity” as to the “intolerable tedium” of pre-time-limit chess. In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) “rather than undergo the torture of another game”. The other case (though recounted in the BCM for February 1940) is less well-known. In one of the “side-shows” of the great 1851 tournament, the youthful Frederic Deacon, burning with eagerness to win his chess spurs, was, though already notorious for slow play, selected very injudiciously by the Committee to play a match of seven games up with Edward Löwe, then a perfunctory old stager nearly 40 years Deacon’s senior. The prizes were £8 to the winner and £3 to the loser, and Deacon won the first two games, with Löwe moaning throughout about Deacon’s slowness. In the third game (Deacon later wrote to the Tournament Committee) “Mr Löwe noted the time I took to consider a move and then delayed double that time before he made his own – this was in the presence of Mr Löwenthal and Mr Williams.” (The BCM comments, “We can imagine Williams scenting tedium and watching this new experiment with the air of a patron”.)’

(7854)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘In C.N. 7854 G.H. Diggle reported:

“In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) ‘rather than undergo the torture of another game’.”

Although the match score was level, the same cannot be said of the position on the board, since, at the time of his resignation, Staunton was a piece down in a completely lost endgame. On page 349 of The Chess Tournament (London, 1852) he made a curious remark in a note to his move 41...Kf7 in that game.

“It is clear that Black could have made a drawn battle if he chose, by

41...R to KR’s 8th

42 K to Kt’s 2nd, or 3rd 42 R to QKt’s 8th

43 B to QKt’s 2nd 43 K to B’s 2nd, etc.but it having been long quite evident that his opponent would protract the sitting until he (Black) could no longer support the fatigue (the present game lasted above 20 hours!), he preferred resigning the contest, although two games ahead, to undergoing the torture of another game.”

What exactly did Staunton mean by the last part of that remark? If he was suggesting that his inferior choice of 41...Kf7 was his way of capitulating, he omitted to explain why he played on for a further 38 moves. His eventual resignation, at move 79, was fully called for. He was, clearly, frustrated by Williams’ slow play, but here he seems to have confused that issue with the subject of his resignation and, hence, to have picked the wrong battlefield on which to attack Williams.

This was the return match after Williams had defeated him in the play-off for third place in the tournament. It was played at Staunton’s “country house” in Cheshunt, the exact location of which is not known. As he led by six wins to three before the 13th game but had given Williams the odds of three games’ start, the Badmaster was correct that the match score stood level. Staunton’s remark quoted above that he was two games ahead must be wrong, unless he meant that, after losing the 13th game, he remained two games ahead. Being two games ahead was useless, since Williams, by scoring his fourth win in the 13th game, reached the target of seven wins needed to secure the match, so for Staunton “undergoing the torture of another game” was no longer an option.’

(7858)

Below is the start of an article by G.H. Diggle which was published in the May 1985 Newsflash and reprinted on page 21 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987):

‘The autopsy on the late world championship contest continues. An eminent “ex-Soviet” grandmaster has now declared categorically that “the infamous match ended, appropriately, in shame”. To which “the two Ks” may well reply, in the famous words of a lady witness who made court-room history, “He would, wouldn’t he?”

But throughout the ages, long chess matches have always “come in for some stick”. Löwenthal and Williams, 1851 (L. 7, W. 5, drawn 4) lasted only 16 games but, with no time-limit and Williams at the board, occupied nearly two months. Staunton (annotating the eighth game) maintains an ominous silence for the first 20 moves, but finally erupts:

“It can hardly fail to strike the most unobservant reader that in this match there is scarcely any combination on either side. Mr Williams, with his habitual imperturbability, contents himself by keeping his game together, and exchanging his pieces as opportunity serves, satisfied to await the chances which a 12 or 14 hours’ sitting may turn up. The Hungarian, in despair of infusing anything like fire into such an unimaginative opposite, resigns himself to the far niente tactics of the enemy, and like him resolves to wait and watch also. The remarkable thing is that with all this wariness and lack of enterprise, with hours upon hours devoted to the consideration of the shallowest conceptions, the games abound with blunders. In a game shortly preceding this one, Mr W. leaves a bishop en prise. In the present, we find Mr L. very generously giving up his queen, and in the very next game Mr W. loses his queen in a similar manner.” [London, 1851 tournament book, page 277.]

(8075)

From Joose Norri (Helsinki):

‘In an article in the 7-8/2003 issue of Suomen Shakki I pointed out, on pages 234 and 244, that there is some confusion about the Wyvill formation. Firstly, Tarrasch attributes to Wyvill the stratagem ...Na5, ...Ba6 and ...Rc8, whereas Euwe/Kramer and Kmoch use his name to describe the actual pawn structure. More importantly, I believe that Tarrasch was mistaken. No such game by Wyvill from London, 1851 exists. In one game, Wyvill v Anderssen, he had the doubled pawns, but he is supposed to have recognized the weakness of such pawns and not to have had them.

There are, however, two games played by Elijah Williams at London, 1851 (Staunton v Williams and particularly Löwenthal v Williams) which fit the description. Williams never had time to carry out the whole manoeuvre with the knight, bishop and rook, but he clearly intended it.

There remains the question of whether Wyvill used the idea somewhere else.’

(8268)

See Marmaduke Wyvill and the Wyvill Formation.

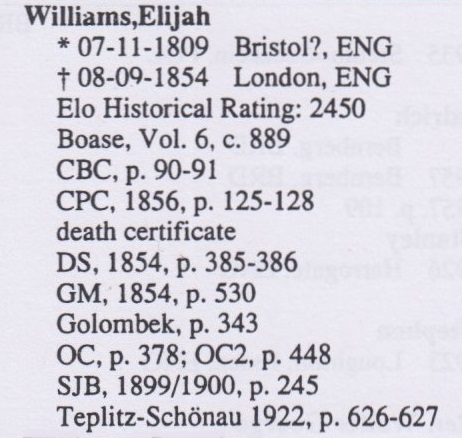

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) mentions that the Immortal Game was published on pages 171-172 of Horæ Divanianæ by Elijah Williams (London, 1852):

(8862)

See our feature article on The Immortal Game.

Below are extracts from C.N. 9909, in which John Townsend wrote about Joseph Brown:

...

‘The 1841 census (National Archives, HO 107 665/2, f. 11) described Joseph Brown as a “special pleader” at Bedford Row, Islington, with his wife, Mary. In the same household was William Smith, aged 29, a man of independent means, who is taken to be Mary’s brother. It appears that William Smith also became a chessplayer, since a man of that name, of Winchcombe, appears on page 142 in the list of subscribers to Elijah Williams’ book Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club (London, 1845), in addition to the following entry on page 139:

“Brown, Joseph, Esq. Temple, London.”

...

The Middle Temple had at least one other very fine chessplayer, Thomas Wilson Barnes. Born in Armagh, Northern Ireland, he had obtained his M.A. at Trinity College, Dublin in the summer of 1851 (source: Alumni Dublinenses, 1924, page 41) before being called to the Bar on 8 June 1852. He became one of the strongest amateurs of his day, winning casual games against Paul Morphy. Another barrister of the Middle Temple, though not, as far as is known, a chess proficient, was Richard Brinsley Knowles (1820-82), who was called to the Bar on 26 May 1843. He must have known Joseph Brown. An author and dramatist, Knowles edited the Illustrated London Magazine from 1853 to 1855. For a short time, Elijah Williams edited a chess column for the magazine, and on page 141 of volume one (1853) he annotated a game in which he played the white side of a Queen’s Gambit Declined against “Joseph Brown, Esq.”. It was a long game, eventually won by Williams. Earlier, on page 96, in an introduction to Williams as the chess editor, the following statement had been made:

“In each month he will supply the latest games of any interest played by the best players.”

This makes it seem possible that the game against Brown was fairly recent. If so, Brown’s ability to compete against the winner of the third prize at the 1851 London international tournament without receiving odds would suggest that he retained the reputation of being a strong player as late as 1853.

An earlier game between the two had appeared on pages 126-127 of Williams’ 1852 book Horæ Divanianæ:

Elijah Williams – Joseph Brown

Occasion?

Scotch Gambit1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Qf6 5 O-O d6 6 c3 d3 7 Ng5 Ne5 8 f4 Nxc4 9 Qa4+ Bd7 10 Qxc4 O-O-O 11 e5 Qf5 12 Qxf7 Nh6 13 Qxf5 Bxf5 14 h3 dxe5 15 g4 Bc5+ 16 Kh2 Bxg4 17 hxg4 Nxg4+ 18 Kg3 Ne3 19 Bxe3 Bxe3 20 Nf7 Bxf4+ 21 Kg2 g5 22 Nxh8 Rxh8 23 c4 e4 24 Nc3 e3 25 Rae1 Re8

26 Kf3 h5 27 Rh1 e2 28 Rxh5 Bd2 29 Rxe2 g4+ 30 Kf2 g3+ 31 Kf3 dxe2 32 Nxe2 Re3+ 33 Kg2 Rxe2+ 34 Kxg3 Be1+ 35 White resigns.

The list of subscribers to Horæ Divanianæ includes on page 173:

“Brown, Joseph, Esq., Temple”

Later, this game was given in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, December 1870, pages 180-182, where Black was identified as “Mr J. Brown, QC”. The date of the game is not known, and it may have been well before Williams reached his full strength. The same consideration applies, only much more so, to ten games between Elijah Williams and J. Brown, “one of the best Metropolitan players”, which had previously appeared in Williams’ Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club in 1845. These games were numbered LXXI to LXXX on pages 91-105, and Williams won six to Brown’s three, with one drawn.

In another game, published on page 155 of volume eight of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1847, Williams won against Brown on the black side of a French Defence Exchange Variation.

It is uncertain whether Elijah Williams’ opponent was Joseph Brown in six other games, played by him against “Mr B---n”, which had previously been published in volume three of the Chess Player’s Chronicle on pages 291-297. If it were confirmed, it would mean that the two had played each other as early as 1842. Of the six, Williams won two and lost one, with three draws.

Joseph Brown’s legal activities naturally focused on his commercial practice, which was prosperous. His obituary in the Times considered him “industrious and learned, rather than brilliant”. He was the author of several legal titles, the best known perhaps being The Dark Side of Trial by Jury (1859). His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography indicates that he “had a wide-ranging intellect and interests”, including geology and numismatics. Evidently he chose to keep a low profile as a chessplayer, but, in any case, there are no obvious signs of his having played after his mentions by Williams.’

John Townsend writes:

‘Personal biography

Elijah Williams was born on 7 November 1809 and baptized on 3 June 1810 at a Calvinistic Methodist chapel known as the Tabernacle in Penn Street, Bristol (National Archives, RG 4/1360), a son of Elijah Williams and his wife Sarah, of the parish of St Stephen in Bristol. The same register also contains baptism entries for two siblings, Ann Baynton Williams (1805) and Joseph Baynton Williams (1807).

Father and son were sometimes referred to as Elijah Williams senior and junior. The occupation of Elijah Williams senior at the time of his son’s birth is not known. An “Elijah Williams, of the city of Bristol, upholsterer, dealer and chapman” was declared bankrupt in the London Gazette of 30 May 1815, page 1029, but it remains to be established whether it was the same person.

Page 183 of Mathews’s Annual Bristol Directory for 1836 shows that by that time the chessplayer’s father was a landing waiter, at 15 Portland Street, Kingsdown. It was a responsible customs job, overseeing the landing of goods from vessels. On the next line is an entry for Elijah Williams junior, a surgeon, of 24 Union Street.

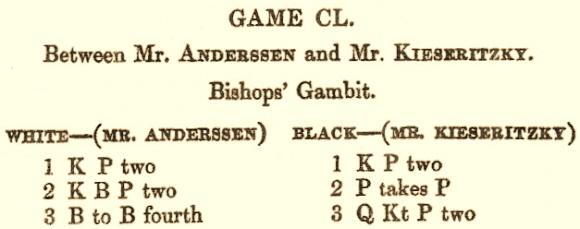

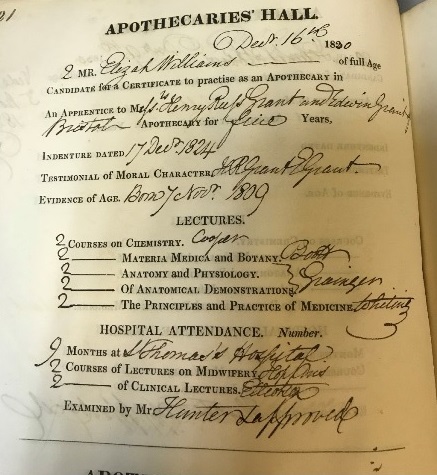

Williams qualified as a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA), to whom I am grateful for providing the following information from their “Court of Examiners’ Candidates Qualification Entry Book”. This shows that he qualified from Apothecaries’ Hall on 16 December 1830, having been examined and approved. He had been an apprentice by an indenture of 17 December 1824 to Messrs Henry Russ Grant and Edwin Grant, Bristol apothecaries, for five years. His masters also provided a testimonial of his moral character. He had attended lectures in Chemistry, Materia Medica and Botany, Anatomy and Physiology, Anatomical Demonstrations, and the Principles and Practice of Medicine, while his hospital attendance had included nine months at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, two courses of lectures on Midwifery and two courses of Clinical lectures. The record also confirms his date of birth as 7 November 1809.

His occupation was surgeon at the time of the 1841 census, when he was listed at Stokes Croft, Bristol (National Archives, HO 107 372/2, folio 11).

His brother, Joseph Baynton Williams, was declared bankrupt in the London Gazette of 15 October 1841, page 2558; he was described as a wholesale and retail ironmonger, dealer and chapman, of the city of Bristol. At other times he was a solicitor, having been articled on 26 October 1825 to William Baynton, of Bristol (National Archives, KB 106/11) and on 20 May 1829, for the remainder of the term, to Edward John Horton, of Furnival’s Inn, Holborn (National Archives, KB 106/14). A William Baynton of Clifton appears in the list of subscribers appended to Elijah Williams’ 1845 book Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club. In 1846 Joseph was in London, but spent some time in the debtors’ prison for London and Middlesex, as is shown by a notice regarding his insolvency in the London Gazette of 1 May 1846, page 1620. He eventually surmounted these financial difficulties. By coincidence or design, Joseph’s presence in London was close to the time when Elijah moved to the capital.

Elijah Williams’ first marriage took place on 9 April 1844 in the church of St Mary Kirkdale, near Liverpool, his bride being Amelia Cassin, “youngest daughter of T. Cassin, Esq.”, and the service performed by Rev. D. James, according to the Manchester Courier, 13 April 1844, page 6.

Elijah Williams was described as a surgeon, of Bristol, which suggests that he was in Kirkdale just for the wedding rather than as part of a longer stay in Lancashire. A Diocese of Chester marriage licence allegation, dated 6 April 1844, indicates that Amelia was a spinster, of the parish of Walton on the Hill, and Elijah a bachelor. Her surname in that document was spelt Casson.

An Amelia Cassin is to be found in the 1841 census in the expected locality at Devonshire Place in the parish of Everton, her age indicated in the range 30-34 (National Archives, HO 107 519/3, folio 44). In the same household were a John Cassin, merchant – possibly a brother – and two small children.

The marriage was soon ended by death, though not before it bore fruit. The parish register of St Mark, Kennington (South London) shows that a daughter, Mary Cassin Williams, was born on 26 August 1846 and baptized there on 11 October. In 1850, Elijah married again as a widower, so Amelia is assumed to have died in the intervening period. There is an entry in the General Register Office’s index of deaths for Amelia Williams, aged 36, in the district of Lambeth for the December 1846 quarter (volume four, page 200), which, if it were the correct entry, would mean that she died only a few months after the birth of the child. Their daughter died in St Leonards-on-Sea on 22 November 1931 at the age of 85 (National Probate Calendar).

His second marriage was recorded in the register of St Mary’s, Lambeth, on 21 November 1850, and was by licence. The groom was described as Elijah Williams junior, widower, a surgeon, of 56 Walnuttree Walk, son of Elijah Williams, gentleman, and the bride as Mary Ann Robina Moore Hodson, a spinster, of 32 Dodington Grove, a daughter of John Hodson, deceased, a clerk in the Audit Office.

It is at 32 Dodington Grove, Newington, that the couple are to be found in the 1851 census (National Archives, HO 107 1568, folio 6). This was the Hodsons’ family home, and was headed by Williams’ mother-in-law, Mary Hodson, who lived off “funded property”, having been born in Barbados. Williams was described as a lodger, a non-practising surgeon. His wife was born in Middlesex, and her age was given as 28.

In a rare, if not unique, physical description of Williams, he was noted by H.A. Kennedy in an article entitled “A Desultory Ramble with the Chess-men”, which appeared on page 47 of Charles Tomlinson’s Chess Player’s Annual (London, 1856) as having “burly form, light hair and eyes, and florid complexion”.

According to the General Register Office’s index of deaths, Elijah Williams senior died in the final quarter of 1853 in the registration district of Bedminster, Somerset, his age given as 77 (volume 5c, page 501). Page 8 of the Bristol Mercury, 24 December 1853 states that he died on 6 December “at his residence at Portishead, after a long illness”. His will (National Archives, PROB 11/2187/23) describes him as a gentleman of Portishead, Somerset. He named as his executors two gentlemen of Bristol, who were instructed to hold on trust his estate, which included freehold property on the Broad Quay and in Portland Street, Bristol, and freehold and leasehold property at Portishead. His daughter, Ann Baynton Williams, was to receive the rents and profits of his estate for her natural life. After her decease, the rents and profits were to go to his son, Elijah Williams, and after his death to his four grandchildren, including Mary Cassin Williams, “share and share alike” as tenants in common. The will, including a codicil which was added on 15 June 1853, was proved on 3 February 1854.

A weakness in the provisions in the will was that, in the event of the early death of Elijah Williams junior, his widow would not benefit; nor would the children except in the long term, which meant that all of them would be unprovided for. That swiftly happened.

The tragedy of Williams’ end was reported in “Obituary of Eminent Persons” in the Illustrated London News, 30 September 1854, page 299. It tells the story of his death from cholera on 8 September 1854 at Charing Cross Hospital. He had been “seized with violent pains near Northumberland House”, which no longer exists today, but stood then at the extreme west end of the Strand, on the south side. He had “walked to town”, so his last fateful journey must have taken him from Kennington to the north side of the Thames and thence to the west end of the Strand. A friend advised him to go to Charing Cross Hospital. The article, presumably by Howard Staunton, was written sympathetically and included a plea for charitable support for Williams’ widow:

“We urge the claims of the widow the more earnestly because we are acquainted with her truly deplorable position.”

The parish register of St Mark, Kennington records the baptisms of two other daughters, Ada Ellen on 23 July 1852, the address entered as Surrey Place, born on 4 October 1851, and Blanch Hodson, on 25 October 1854, the address given as South Street, Kennington Common, “sd to be born 14 Novr. 1852”. A son, Elijah, born on 18 January 1854, was baptized there on 5 November, the father’s occupation still entered as surgeon and the address given as Hope Terrace, South Street. Consequently, the remark in the obituary that Williams left “a widow and four young children” can be corroborated.

For the last child, Elijah, a place was obtained at the Infant Orphan Asylum, Wanstead. He led a long and prosperous life, becoming a chartered accountant and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He died at Runfold Place, near Farnham, Surrey, on 1 February 1937 (source: National Probate Calendar). The 1901 census (National Archives, RG 13/200, folio 123) shows that he married and had several children, so there is every possibility that descendants of Elijah Williams the chessplayer are alive today.

As a player and an author

An assessment of Williams’ chess career appeared in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1856, pages 125-128, then edited by R.B. Brien, in an article entitled “Mr Williams as a Chess-Player”. About his style of play it stated:

“If he had any defect in play, it was not over-caution, but a striving for some small advantage, which could hardly be gained without danger. He played, in short, more for little permutations of force and position than in the spirit of high art, although he did not neglect greater things when they came in his way. No-one held to an advantage more firmly than he did, nothing generally was better than the unflinching courage and perseverance which he displayed under difficulties.”

The article notes his early involvement with the Bristol Chess Club and his position as President, mentioning that the club mustered more than 60 members within three weeks of its formation. This springing “into manhood almost at its birth” the author ascribes to a national enthusiasm to obtain victory over the French – eventually achieved by Staunton in 1843 – but no date was attached to the club’s formation.

On page 1 of The Bristol Chess Club (Bristol, 1883) J. Burt claimed to have “undoubted evidence that it was formed in 1829 or 1830, under the Presidentship of Mr Elijah Williams”. Unfortunately, he did not mention what the “undoubted evidence” was. In 1836 the club and several of its members, including Williams and Withers, were listed among the subscribers on page 280 of William Greenwood Walker’s book A Selection of Games at Chess Actually Played in London by the Late Alexander M’Donnell, Esq.

The birth of his first daughter, noted above, shows that he had moved to London by the summer of 1846. Charles Tomlinson (BCM, February 1891, page 53) relates that “he gave up his practice for a precarious seat in the Divan”. If that was, in fact, his hare-brained plan, in official records, at least, he continued to be described as a surgeon for the rest of his life, and it was only in the 1851 census that “non-practising” was added.

His highest achievement was in the 1851 London tournament. After knocking out Löwenthal and Mucklow, he played a semi-final match against Marmaduke Wyvill. He took the first three games to stand on the verge of a place in the final, needing just one more win, but Wyvill, the MP for Richmond, Yorkshire, staged an extraordinary come-back and took the next four games. Williams’ peak had arrived and passed. Nevertheless, by his victory in the contest to decide third place he showed that he was capable of winning a match even against Staunton. The subsequent “revenge” match between them suggested that Staunton was then the stronger of the two, even though Williams won that second match too, on account of the three games’ start which Staunton had conceded. Brien, in his article, countered “a statement then published” to the effect that Staunton lost because of ill-health to an opponent “accustomed previously to take the pawn and two moves” by suggesting that in printed games Williams had not received those odds since 1845. However, he did not question Staunton’s “ill-health”.

A description of Williams’ mode of play comes from H.A. Kennedy in the above-mentioned article “A Desultory Ramble with the Chess-men” in Charles Tomlinson’s Chess Player’s Annual (London, 1856), page 47:

“Mr Williams is a player of large calibre. Tardy in unfolding his plans, and cautious in the extreme, he, nevertheless, marshals his forces with such ability and judgment, as to make them present a firm, compact front, within which no enemy finds it an easy matter to penetrate. His manoeuvres are conducted with soundness and precision, he has great accuracy of calculation, and his constant practice gives him a command of the board equalled by few.”

His two books were collections of games, Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club (Bristol, 1845) and Horæ Divanianæ (London, 1852). In the latter, his hostility towards Howard Staunton is amply reflected by the fact that Staunton was not mentioned anywhere in the book. Williams’ involvement with the Illustrated London Magazine was referred to in C.N. 9909. In addition, he contributed to the Bath and Cheltenham Gazette, The Field, and The Historic Times.

Slowness

Staunton blamed his defeat by Williams in the 1851 London tournament and in the return match on Williams’ excessively slow play. H.J.R. Murray, on page 84 of A Short History of Chess (Oxford, 1963), described him as ...

“the slowest of all players in a time of slow players (for chess clocks had not yet been thought of)”.

In The Times of 19 April 1980, page 7, H. Golombek remarked that Williams has ...

“good claims to be regarded as the slowest player in the history of the game”.

C.N. 3764 quoted some remarks by Irving Chernev about Williams’ supposed slowness. Chernev asked:

‘Was his prolonged thinking part of a plan to infuriate his opponents? Or was it because he was slowly evolving a new system of play?’

P.W. Sergeant alluded to “Williams’ exceedingly slow methods” on page 77 of A Century of British Chess (London, 1934). He made the point that Staunton had previously shown no “ill-feeling” towards Williams and suggested that the latter’s slow play was the sole cause. However, one could argue conversely that the cause was Staunton’s annoyance at being beaten.

In an advertisement for the Illustrated London Magazine the following appeared on page 6 of the Worcestershire Chronicle, of 13 September 1854:

“Mr Elijah Williams, the celebrated chessplayer, who wore out Staunton, contributes annotated games of chess and problems, which add to the former attractions of this pictorial.”

This text must have had Williams’ agreement, and one wonders exactly what was meant by the claim that he “wore out Staunton”. Does it go any way towards acknowledging slow play, or does it merely claim that Williams endured the exertion better? Or was it a joke?

In a letter to Bell’s Life in London, 7 December 1851, page 5, he explained that initially he said nothing ...

“as it was quite apparent to me that Mr Staunton was somewhat irritated by his defeat”.

Staunton’s irritability at that time is well known. In my book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton (pages 111-112) it was suggested that he was suffering from accumulative stress caused by the demands made on him by the 1851 tournament. C.N. 7858 describes an incident from the “return match” which reflects Staunton’s frustration or irritation, resulting in his making an unfair annotation.

Later, Williams felt the need to respond when Staunton persisted with his criticism, and he claimed that he “took no more time over his moves” than Staunton.

R.B. Brien, who had earlier been an ally of Staunton, indicated in his 1856 article that he found nothing remarkable about the speed of Williams’ play:

“The evidence, however, of those who witnessed several of his matches is to the effect that, although there might be an exceptional case, he was on the whole not so very slow.”

There was also support for Williams in the Chess Player, edited by Kling and Horwitz, volume two, 1852, page 304:

“As you observe, the unworthy efforts which have been made to fasten upon Mr Williams the stigma of wilfully playing a ‘slow march’, with the view of wearying out his antagonist, cannot be too strongly reprobated. We have had the good fortune to be present at some of the finest chess matches of late years, and we doubt very much whether Mr Williams’ play is any slower than that which we observed in the matches in question.”

Nevertheless, the number of contemporary players willing to defend Williams appears to have been limited. If he had suffered any real injustice from the criticism, would there not have been more sympathizers? After all, Staunton had no shortage of enemies during the period in question. No-one timed the players’ cogitations, as had Harry Wilson in the Staunton v Saint-Amant encounter in Paris, so uncertainty remains over how slow Williams was.’

(11424)

Addition on 6 August 2024:

With the kind permission of The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, London the image below is reproduced:

It is referred to in C.N. 11424 above. John Townsend sent an enquiry to the Society of Apothecaries because Williams was a surgeon, and some surgeons were members of the Society. Although Williams was not, in fact, a member, the Society was able to report that he gained the qualification LSA (Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries) from the Apothecaries’ Hall on 16 December 1830. The image provided is from the ‘Court of Examiner’s Candidates Qualification Entry Book’.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.