Edward Winter

Shortly before 5 p.m. on Wednesday, 13 September 1911 a man was shot dead in his office at 56 Cambridge Road, Hastings, England. A first bullet, found lodged by the crest of the haunch bone, resulted in a wound seven inches in length in the direction of the thigh bone downwards. A second bullet had gone across his skull, slightly turning upwards and leaving a wound five inches deep.

Persons in the vicinity had heard shots from the victim’s office, whose front window was open, and he was found dead on the floor in a pool of blood. There were no signs of a struggle having taken place. A man stood in the room; he had a revolver in his possession, with three chambers loaded and two discharged. A police officer took him into custody and charged him with felonious, wilful murder with malice aforethought.

The case became a cause célèbre, not least because, a week after the shooting, the officer who had made the arrest went into a police cell and committed suicide with the suspect’s revolver. Moreover, a high-profile Counsel whose successful prosecution of Dr H.H. Crippen the previous year had resulted in the American poisoner being sent to the gallows would, in the Hastings case, be acting for the defence.

The offices in Cambridge Road were the Hastings and East Sussex Building Society, and the victim was the Society’s manager, Frederick William Womersley. He had been a leading figure in Hastings chess circles and a member of the organizing committee of the Hastings, 1895 tournament. For many years he had written the local newspaper’s chess column. Monographs on such players as Blackburne, Lasker and Pillsbury provide the scores of simultaneous and consultation games in which he played against, or with, many of the world’s leading masters. For decades, reports on Hastings chess had seldom lacked a mention of Womersley’s name.

An obituary appeared on page 375 of the October 1911 BCM:

‘The recent tragic death of Mr F.W. Womersley, of Hastings, who was shot in his office, was a great shock to chessplayers generally, but particularly to the members of the Hastings and St Leonards Club. Nearly 30 years’ service to the game had given Mr Womersley a very large circle of chess friends in all parts of the country, and the many messages of sympathy received since his death testify to the esteem in which he was held. Mr Womersley took a prominent part in founding the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club in 1882, and working with others assiduously for some years had the satisfaction of seeing the club acquire great reputation. Elected on the first committee he retained the position for 25 years, when he was elected a vice-president. Playing regularly in the first-class matches and chief tournaments, he won many prizes, including the club championship no less than five times – 1886, 1888, 1891, 1892 and 1902. Joining the club tours in Scotland and Ireland he won the match prize for most wins during the Irish tour. Quite recently he reached the final of the Dobell Cup handicap. In addition to his active work for the club, Mr Womersley edited the chess column in the Hastings weekly Observer, with interest and instruction to both players and problemists. During the famous Hastings international tournament of 1895 Mr Womersley was responsible for the arrangements for play, with excellent results. At one time he was frequently to be met at Simpson’s and other London chess resorts, also at the Cable Matches. Although 72 years of age, he retained his energy and enthusiasm to a large degree, continuing his active interest both in business and chess until an untimely and violent death ended an honourable and useful career, to the sorrow of his relations and friends, the regret of his acquaintances, and the loss of the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club.’

Frederick William Womersley (see

C.N. 10578)

Womersley was an archetypal club stalwart, and towards the end of the present article we shall be looking at some of his chess (including, most notably, a consultation game in which he partnered Janowsky). The brief obituary in the Chess Amateur, October 1911 (page 389) focussed on the singular circumstances of his death, but for the details of the affair it is to the local newspaper reports that we must now turn. Unless otherwise specified, all facts in the present article come from the extensive coverage of the case in the Hastings and St Leonards Observer, as follows:

We are most grateful to Mr Roger Bristow of Hastings Library for copies of the above newspaper reports and for his excellent assistance with other points of fact.

In its first account of the shooting of Womersley and the arrest of the armed man, Joseph James, a 52-year-old chemist, the Hastings and St Leonards Observer gave a description of the victim:

‘The late Mr Womersley is a Hastings man, a son of the late Mr Charles J. Womersley and a brother of Councillor Ben Womersley. He was respected as a thoroughly reliable business man; he had been for 22 years manager of the Hastings and East Sussex Building Society (which formerly had its offices in Trinity Street) and, in addition, he was an accountant and held several local auditorships. He was always a hard worker, and about his only recreation outside his love for Sunday school and other religious work was that of chess. He had a good deal to do with the great International Tournament held at Hastings some years ago, and was himself one of the leading local players, holding the captaincy of the club for some years. For a considerable period our readers will remember the interesting chess column in the Observer, which was regularly contributed to by Mr Womersley during the winter months. For a long period he was a leading member of the congregation of the Croft Congregational Chapel. In all his business relations Mr Womersley was fair and reasonable, and those who knew him intimately knew that at heart he was a thoroughly good-natured man.

Mr James has resided in Hastings and carried on the business of a chemist in Nelson Road for two or three years. It is said that he came to the borough for the benefit of his health, and it is believed that his business has not flourished and that of late he has had financial troubles.’

The morning after Womersley’s death, 14 September, Joseph James appeared at a packed Police Court, the formal charge being ‘feloniously killing and slaying’. He was described as a short, thick-set man with a ruddy complexion who wore a loose lounge suit and pince-nez glasses. The purpose of the hearing was merely to present sufficient evidence to justify his being remanded in custody. During the proceedings he was entitled to ask questions and he proved trenchant in his observations on the testimony of one of the witnesses, Richard Francis, a riding master at the Royal Mews, Cambridge Road. After Francis had answered questions from the Clerk, a series of exchanges took place between the witness and the accused:

James: ‘It is a tissue of falsehoods. Do you say you were the first man in the house?’

Francis: ‘Yes.’

James: ‘No; the first was a common man, with reddish hair, and he came to the station and said, “When you want me you will know where to find me”.’

Clerk: ‘Did you see any other man in the house?’

Francis: ‘No.’

James: ‘Did you hear me call “Police, help, and doctor”?’

Francis: ‘No, you did not.’

James: ‘It is merely a case of one man contradicting another.’

Clerk: ‘This is a very important matter.’

James: ‘That is why I want it down. It is very important. You say three or four shots were fired. Are you aware only two shots had been fired? If all your evidence is taken on that scale, it is not worth much.’

Francis: ‘I said I thought I heard two or three; I could not say for certain.’

James: ‘I don’t think it is any good going into the matter. Your evidence is not satisfactory. I never used the words “I give myself up”. I called “Police” at once.’

Francis: ‘You did not call “Police” at all. You asked me if I would call a doctor. I went and fetched the doctor myself.’ …

James: ‘In which pocket do you say I put the revolver?’

Francis: ‘Right-hand.’

James: ‘You said right-hand jacket. I have not got one. It was the trousers’. [Francis had indeed told the Clerk earlier, ‘he put it into his jacket pocket’.] ‘In what direction was the man’s face turned, right or left?’

Francis: ‘Left.’

James: ‘Facing the fireplace or door?’

Francis: ‘I can’t say.’

James: ‘Your evidence is not worth taking down. You don’t know where the man’s face was placed.’ …

James: ‘You said you never left me?’

Francis: ‘I left you, and went and called the police. You told me you would give yourself up.’

James: ‘You contradict yourself every time. Did you see a short man with ginger hair, commonly dressed?’

Francis: ‘Yes; he followed me in.’

James: ‘I thought just now you said you did not see him. That evidence wants reading over. One gets fogged. I think that’s all I’ve got to ask him. Quite understand, I plead not guilty. It was quite an accident.’

Later in the hearing, Detective Sub-Inspector Edward Chantler made a deposition:

‘At five minutes past five last evening I was called to 56 Cambridge Road. When I got there I saw the prisoner sitting in a chair in the front room of Mr Womersley’s office, on the ground floor. P.C. Lawrence was standing close beside him, and he gave me this revolver. (The revolver, a formidable looking weapon, was handed up to the Bench.) I saw the body of Mr Frederick William Womersley lying on the office floor. He was lying on his back, with his head towards the window, and was being attended by Dr [Adolphus Theodore] Field. The latter said to me in prisoner’s hearing: “He is dead.” I said to prisoner: “I am a police officer; whatever you may say now may be taken down in writing and used as evidence against you.” He replied: “I called to see him; we had a quarrel, and I fired a shot to frighten him. He knocked my hand up. It was an accident. I am quite willing to go with you.” I took him to the station, where he was charged. The charge was read over to him, and he replied: “Not with malice aforethought; it was an accident; he sold my home up today. I called on him to ask why he let my goods go practically for nothing. He was very insolent, and said he would make a further distraint.” There was a good deal of blood on the floor of the room.’

James also had the right to cross-examine the police officer, and did so with vigour:

James: ‘Where is the detective with whom I walked down Cambridge Road to the police station?’

Chantler: ‘I was the officer.’

James: ‘He was shorter than you.’

Chantler: ‘No; I went with you myself.’

James: ‘You said just now the revolver was given up in the front room of Womersley’s; I walked down with it in my trousers pocket?’

Chantler: ‘No; you are wrong.’

James: ‘I say the same to you. Dr Field said: “Where is the weapon?”, and I said I would give it up at the station. It is no good going further; it is only a waste of time. My word is as good as yours.’

Chantler: ‘Yes, quite.’

James: ‘When you went into the room, and Dr Field was attending to him, in what position was his head?’

Chantler: Towards Cambridge Road.’

James: ‘How was he facing?’

Chantler: ‘Facing the sea.’

James: ‘I fancy you are mistaken. Dr Field put round the head in order to see the position of the wound.’

Next, Dr Field, a police surgeon, made a statement:

‘At five o’clock yesterday afternoon, I had an urgent message to go to Mr Womersley’s house, which is next door but one to my house. I went immediately. I was conducted into the front room, where I saw Mr Womersley lying on the floor. I examined him, and found he was dead. He was lying across the room in an oblique position, partly on his right side; the head was under the table furthest from the window, the legs being nearest to the door. There was a gunshot wound in the head at the back of the left ear. There was a small cut on the back of the head probably caused by a fall.’

At a later hearing Dr Field was to state that on the evening of Womersley’s death he was summoned to the Central Police Station and saw Joseph James in a cell. James told him that he suffered from valvular disease of the heart. Field had examined him, and ‘James was hysterical and burst into tears’.

On the afternoon of Friday, 15 September, the inquest into Womersley’s death was opened at the Market Hall before the Borough Coroner. Among those in attendance were three relatives of the deceased: his son Godfrey (‘formerly well known as a vocalist’), his daughter Emily and his brother Ben (a councillor). James himself was not there, but was represented by a solicitor.

Emily Womersley, who had lived with her father, testified that she last saw him alive at 4.15 p.m on the day of his death, seated in a revolving chair at his office desk. He was alone and appeared in his usual health. She was aware that her father had a tenant of a house in Nelson Road named Joseph James, although she did not know him.

Richard Francis said that shortly after the shooting he entered the room and saw James with his back to the entrance, standing just in the doorway. He stated that he heard James, who was about four feet away, say, ‘You’ve asked for this’, in a rather harsh tone of voice. James then said to him, ‘It’s an accident’.

The first police officer on the scene, P.C. Lawrence, related that in the hall he met James coming through the doorway from the office. James had said, ‘Constable, there has been an accident with a revolver and I wish to give myself up’. Lawrence commented, ‘One report [i.e. sound of gunfire] may be an accident but two are not’. James made no reply. However, he did also remark, ‘I always carry a revolver’. He handed the weapon to Detective Sub-Inspector Chantler.

The following week (i.e. Wednesday, 20 September) the coroner’s inquest was resumed for further testimony before being adjourned again. Then on 21 September Joseph James came before the Magistrates on the remand charge of wilful murder. The Observer reported:

‘The greatest excitement was again evinced, possibly as it was known the day previous that Mr R.D. Muir, the famous Counsel, was coming to conduct the defence on behalf of James. It will be remembered that Mr Muir amongst the famous criminal trials in which he has figured was also prosecuting Counsel in the celebrated Crippen and Morrison cases.

With him was Mr C.F. Baker, who had represented James at the adjourned inquest during the previous evening. The court was crowded to suffocation, and for half an hour before the doors were opened a large throng of people assembled outside, and there was much jostling in order to be the first in.

…James walked slowly into the dock with his pince-nez almost on the tip of his nose and slightly bowed to the Magistrates. He again showed great composure, and before being told to sit down he placed both hands on the front of the dock with a pencil protruding and glanced calmly round the court.

In his opening address for the Crown, Mr Day [A.W. Day, a solicitor to the Treasury], after stating that in view of the present stage of the case he would not give a lengthy address, said that James was 52 years of age, and had had a chemist’s business in the town for several years. On 21 August Mr [William Neaves] Oldham received a distress warrant from Mr Womersley. Accused asked the Auctioneer that the sale should not take place on his premises, because it might by that course be somewhat prejudiced, and suggested that certain goods should be given over to the Auctioneer. After consultation with the deceased this arrangement was ultimately agreed upon. After a list had been shown to the Auctioneer by James, the former said that it was not sufficient and he would have to put a man in. Accused was alleged to have answered, “If you do, he will have a rough time of it”. It was about an hour and a half after the completion of the sale that James called at deceased’s office and the tragedy happened. He submitted that the motive for shooting deceased, as shown by accused’s own statements, was utter revenge for the small price which his goods had fetched. [The gross amount was £14 12s., which Oldham considered ‘a very fair price indeed’.]

…Describing the shots, he said one entered the right thigh and travelled almost to the knee, which showed that it must have been fired from a position above, and he suggested that it was fired when the deceased was bending down. Accused had said it was an accident. If fired immediately after one another, as in the case of an accident, it would have sounded “bang-bang”, but the man Francis had time to run across the road before he heard the other shot. One went in his left ear and the other his right thigh, so that the position of the men in relation to one another must have been entirely different at each shot.’

Another witness was the accused’s young daughter (aged 13 or 14), Gladys Trewartha Noble James, who had accompanied her father to Womersley’s office. ‘When we got there, father rang the bell outside. The outer door was open; the inner door was shut. Mr Womersley answered the bell. …Father said, “I have come to have a little chat about this matter this afternoon.” Mr Womersley said, “Come to my office.” Joseph James’ daughter remained just inside the outer door, having shut the inner door. She heard her father say that he did not see why an eight-guinea Warwick machine should go for eight shillings and ask Womersley, “Are you going to distrain again?” Womersley ‘said he did not know; he must see’. Then she heard a shot from inside the office. She opened the door to leave (to go to Dr Field’s house), and as she went down the steps she heard another shot.

A dealer from 106 All Saints’ Street, John Jones, repeated his evidence from the inquest, i.e. that he had been attracted by the sound of quarrelling from Mr Womersley’s office, and had then heard two shots, the interval between them being the time required to fill a rifle with ammunition. James, he said, had told him, ‘It’s an accident. I have had a lot of trouble with this man, and I fired a revolver off to frighten him.’

The case was again adjourned.

The Hastings and St Leonards Observer of 23 September 1911 carried the dramatic headline ‘Detective in charge of Case shoots himself with accused’s Revolver’ and reported that just after 9 a.m. on the Wednesday morning (20 September) Detective Sub-Inspector Chantler, a single man aged 35, was found shot dead in one of the cells at the Central Station, ‘with a wound in his head and a revolver clasped in his hand, the same as used by James the previous week’. Two chambers of the revolver were still loaded, while one contained an empty cartridge. Dr Field reported that he had found a large lacerated wound in the roof of the mouth and a fracture at the base of the skull radiating from the wound and caused by the bullet. From this he concluded that the muzzle of the revolver had necessarily been in Chantler’s mouth when the shot was fired. The Jury found that the police officer had committed suicide during temporary insanity. No satisfactory explanation for his motivation was put forward, although there was naturally speculation as to whether his handling of the James case had prompted him to kill himself. The Chief Constable of Hastings, Frederick James, told the inquest that he had discussed the Womersley case with Chantler the evening before the latter’s death.

Coroner: ‘Did he have anything to say about the case to you?’

Chief Constable: ‘He did mention that he had made one discrepancy before you. I did not look upon it as such, and it was to be corrected at the next enquiry. It did not in any way affect the evidence. When he brought the prisoner James into the Central Office he stated before you that the prisoner immediately made a statement, whereas he should have said that the statement was made shortly after the formal charge had been read to him.’

Coroner: ‘That was a very trivial thing.’

Chief Constable: ‘Quite so. I mention it to show how careful he was in his work.’

Coroner: ‘Did it trouble him?’

Chief Constable: ‘Not in the least.’

Coroner: ‘Can you account for this affair in any way?’

Chief Constable: ‘No. Chantler was the last man I should think that would take his life.’

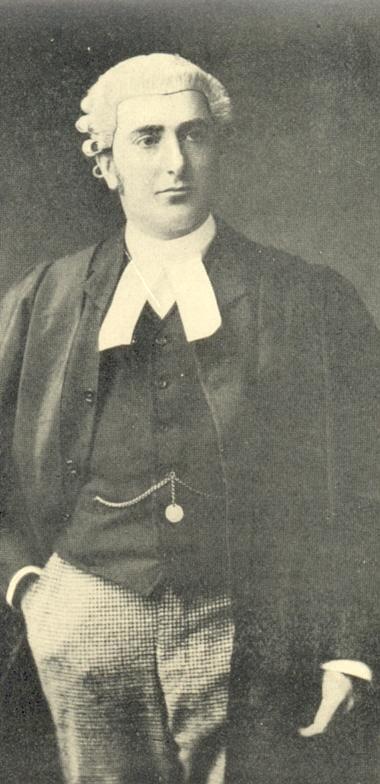

Richard Muir

The court hearing on 30 September lasted three and a half hours and featured ‘a lengthy cross-examination of Mr A.T. Field, the police surgeon, by Counsel for the defence, Mr R.D. Muir. He directed a vigorous fire of questions to the doctor, who answered with remarkable calmness.’ Above all, the day ‘was remarkable for a most dramatic speech from the dock’ by Joseph James:

‘I wish to explain why I fired the revolver.

On Wednesday, 13 September, in the afternoon, I called on Mr Womersley for a business chat. Our chat over, I gave him notice that I should damage his mantelpiece. It would be a means for my getting a summons for damages in the County Court, and so air there some of the grievances which I had. Accordingly, I rose from my chair – I was then seated at the end of the table near the window on the door side – drew the revolver from my right-hand pocket, and pointed at the jamb of the mantelpiece opposite my right hand. The muzzle was slightly depressed, and would have hit a spot about 18 inches from the shelf of the mantel. I glanced at the weapon to see that it was in order, but on looking up found that Mr Womersley was sliding from his chair, head to the window, face downwards. I at once saw that his head was in the line of fire; my finger was on the trigger, I had brought slight pressure to bear, and anxious not to hit him, like a flash I altered the direction of the revolver to the other jamb. I had not time to notice that the muzzle had been acutely depressed. The explosion took place, and Womersley was hit on the right haunch.

I was horrified and dazed, and for a moment did not know what to do. I thought we must have help, and went towards the door. The door was then about 18 inches open. Just as I was about to open it further, I heard a noise at my back, and wheeling round to the left I saw that Womersley had risen from under the table about 18 inches from the end.

The expression on that man’s face I shall never forget. Fiendish rage and hatred! I felt positively afraid of him. Glaring at the revolver which was in my right hand instinctively made me remove my finger from the trigger catch, and with it and the rest of my hand firmly grasped the stock of the revolver. We were then about three paces apart. He lunged towards me, and I put up my left arm to fend him off. With his right hand he broke down my defence, and with his left knocked up my right hand which held the revolver shoulder high, with his right hand he grasped the muzzle of the revolver; with his left hand he grabbed at the trigger guard. His fingers became entangled with the trigger. Turning his face to the fireplace and slightly inclined to the right, inclining his body also to the window as though as to get the weight of his body as well as his arm force into the coming wrench, he made a terrific wrench. I felt my hold on the stock loosen; there was an explosion, and Womersley fell to the floor shot.’

James then stood back in the dock, paused a while, and added, ‘That is all’.

At the end of the hearing, James ‘was committed to the Lewes Assizes on the capital charge of wilfully murdering Frederick William Womersley on 13 September’.

The adjourned inquest, for its part, was concluded on 4 October, and the Jury then took only seven minutes to reach its decision:

Coroner: ‘Are you agreed upon your verdict?’

Foreman: ‘Yes, sir.’

Coroner: ‘What do you find the cause of death?’

Foreman: ‘That he was shot in the head.’

Coroner: ‘Who by?’

Foreman: ‘By Joseph James.’

Coroner: ‘What else?’

Foreman: ‘And we also find a verdict of Wilful Murder against James.’

After completion of the inquest it was two months before the date of the trial was announced: 11 December, at the Assizes in Lewes, Sussex.

The Observer’s headlines included ‘Hastings Office Sensation’ and ‘Extraordinary Development in Murder Trial’ to describe what happened that day. Mr Justice Scrutton called the Counsel for the prosecution and the defence into his private room, and upon their return to court some ten minutes later the Clerk announced, ‘Bring up Joseph James’. Then, the Observer recorded:

‘The prisoner walked in slowly and glanced all about him as if in amazement before finally stepping into the dock. He then remained practically in the same attitude as at the Police Court proceedings, just holding on to the rails of the dock, and with his pince-nez balanced on the tip of his nose, looking calmly at the Counsel and the Judge. He wore a light tweed suit, but whatever horrible suspense into which his two and a half months’ custody must have plunged him, it left no outward sign of its effects. On the contrary, prisoner looked exceedingly well, and there was only one incident, when his brother had to unravel the painful past of their family, and his mother’s unhappy death in an asylum, at which the prisoner showed any emotion.’

The court heard that enquiries had been made into the mental history of James and of members of his family, many of whom had been of unsound mind. Experts and other witnesses (including the accused’s son Stanley), stepped forward to speak of Joseph James’ instability, and not all the evidence was weighty. The Observer noted that Dr Reginald Brown informed the court that he had become acquainted with James when the latter was a chemist in the Stoke Newington area:

‘[Brown] referred to the fact that [James] had worked up a big business, but caused considerable attention as the result of peculiar notices posted outside his shop. One of these ran, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. I am off for four days’ holiday.”

His Lordship: “I don’t know that that is a sign of insanity. Members of the Bar sometimes do that.” (Laughter).’

It was a rare moment of levity. The evidence heard, the Jury required only a minute’s deliberation before returning its verdict. The Observer reported:

‘At the Sussex Assizes on Monday, Joseph James, 52, a chemist, described as of superior education, was found insane, and therefore unfit to plead in the indictment against him of murdering Frederick William Womersley, at Hastings on 13 September 1911.

…“The order of the court is that the prisoner shall be kept in strict custody until His Majesty’s pleasure be known.”’

He was then taken away to an institution and forgotten.

Memories of Frederick Womersley also faded. Despite his long enthusiasm for chess, it is no easy task to put together a set of fine games played by him, although it may be recalled that Chess Notes (item C.N. 2618) gave a remarkable king march which he brought off in the 1880s. Especially towards the end of his life he was prone to bad oversights, and it was hardly generous of the Chess Amateur (July 1911, page 305) to publish a game lost by Womersley that May in a match between Hastings and Thornton Heath; he was mated by A.W. Foster at move 16 after a blunder which allowed a smothered mate in one in the centre of the board. Around this time, it may be mentioned, another family member was playing alongside him. Page 118 of the March 1909 BCM gave the results of a team match in which Hastings had played Tunbridge Wells on 31 January. On board five Womersley had drawn with R.H.S. Stevenson, while the board nine for Hastings had been ‘Mr G. Womersley’. (See also page 467 of the October 1907 BCM.)

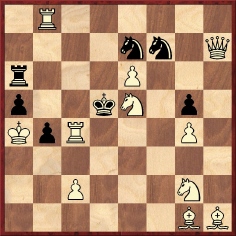

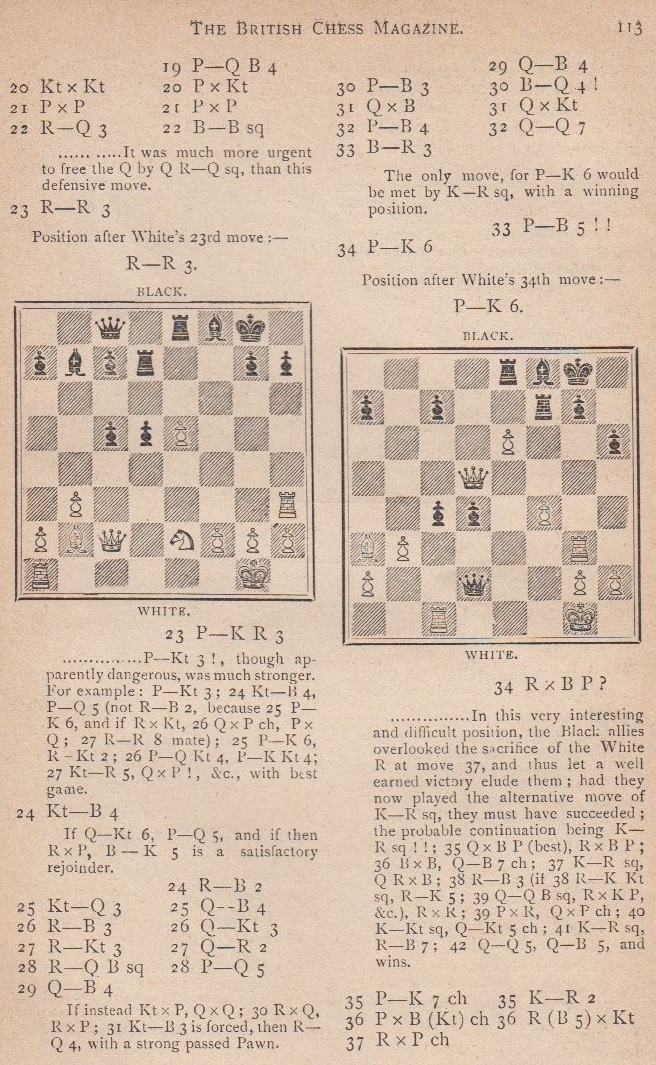

Nor were Womersley’s published problems always of choice quality. His mate-in-three compositions given on page 524 of the December 1894 BCM and page 464 of the November 1896 BCM were unsound, the former being declared to have eight solutions. The best problem we have found is the following three-mover, which won first prize in the Sussex Tourney and was published by James Rayner on page 429 of the October 1888 BCM:

Key move: 1 Re8.

The flavour of Womersley’s writing style is conveyed by the opening paragraph of ‘Chess Tourists’, an account of the Hastings Club’s tour of England and Scotland on pages 375-378 of the September 1899 BCM:

‘Some few months ago, our hon. sec., Mr H.E. Dobell, mentioned that in taking his annual holiday he generally had himself for companion, but how much more enjoyable it would be if a few friends could take their vacation together, and suggested some of the members of the chess club might unite for a week or two, and take a tour together. What boy could resist the idea of a holiday and we, some old boys, together with some of the girls, I mean lady members, at once accepted the suggestion as a happy one, and requested him to arrange a tour that would bring us into touch with some of the most noted provincial chess clubs, and an opportunity of crossing pawns and becoming acquainted with players whom many of us knew by repute, as well as give an itinerary of interest to us as tourists.’

In a 1935 article published on pages 270-272 of the December 1943 BCM Dobell praised Womersley’s contribution to the success of the Hastings Club, which included securing playing accommodation at the Queen’s Hotel in 1887.

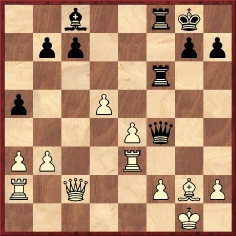

We conclude with what is perhaps Womersley’s most interesting contribution to chess literature. After partnering Janowsky in a consultation game, he transcribed their discussions during play and published them in his Observer column of 11 January 1902 (page 6). They were also reproduced on pages 74-76 of the February 1902 BCM.

Joseph Henry Blackburne and I.M. Friedberger – Dawid Janowsky and Frederick William WomersleyF.W.: ‘Have you any special defence you would like to try? If not, we will accept any gambit or opening they like to offer.’

D.J.: ‘All right.’

1 c4

D.J.: ‘Oh, oh, English. Well, there is no special defence, we will play French; English v French.’

1…e6 2 g3

D.J.: ‘An original method, which I do not think is good in conjunction with 1 c4; but Mr Blackburne wants to try an experiment.’

2…d5 3 Bg2

F.W.: ‘Shall we advance the pawn, which we can afterwards support?’

D.J.: ‘It is rather premature; we might bring out the knight first, but well –’

3…d4 4 Nf3

F.W.: ‘If we push …d3 it might be troublesome.’

D.J.: ‘Yes, but also difficult to sustain; better –’

4…Nc6 5 d3

D.J.: ‘Now they wish to prevent …d3 and also to develop their queen’s bishop. We may as well bring our bishop into play (the knight can always come out, and it may be via e7); the best square seems d6, where it will prevent Bf4 and also support the pawns when they advance.’

5...Bd6 6 Nbd2

D.J.: ‘To await events. Equally available for f1, e4 or b3.’

F.W.: ‘Shall we play …f5?’

D.J.: ‘You are a little too impulsive; let us get the e-pawn on first.’

6…e5 7 a3

D.J.: ‘In order to advance the b-pawn and drive us off the queen’s side. We therefore prevent by –’

7…a5 8 b3

D.J.: ‘Naturally. We can now advance our f-pawn, and afterwards bring out the knight.’

8…f5 9 Qc2

D.J.: ‘Threatening c5, also to prevent advance of our pawns.’

F.W.: ‘Shall we play …Qe7, supporting our centre and the bishop also?’

D.J.: ‘Where to place the queen is always a matter of special consideration, and we are not quite ready for that; we can avoid the threat and prevent the advance of their e-pawn by –’

9…Bc5 10 O-O

D.J.: ‘Bring a piece into play supporting the centre for an advance.’

10…Nf6 11 Re1

D.J.: ‘They are much cramped in position, and must free their game; the move makes room for Nf1, and will support the advance of the e-pawn. For ourselves, the general principle, don’t leave your king opposite an enemy’s rook, even though several pieces may be between.’

11…O-O 12 Nf1

D.J.: ‘Here are several interesting continuations. Suppose 12…e4; if 13 dxe4 Nxe4, and we may continue …Nxf2, with a splendid attack; and if 13 Nh4 Ng4, also with a good but complicated attack; no doubt premature until the queen’s bishop and rook are in play, therefore –’

12…Qd6 13 e3

D.J.: ‘At this stage the White are much restricted in play, and we can play …Bd7 and afterward …Rae8, with a very fine game.’

F.W.: ‘The variations you have just shown and others on our playing …e4 are so interesting, I would like to continue with that line.’

D.J.: ‘If I was playing a tournament game I would bring out my pieces and could not lose, but it would be a venture to advance now.’

F.W.: ‘I would rather try an interesting and exciting game, even if we lost, than win a dull plodding contest.’

D.J.: ‘It is the most important move of the game; let us look a little further. We will try it.’

13…e4 14 Nxd4

D.J.: ‘Best. If 14 dxe4 then 14…d3 15 Qb2 fxe4, with a strong centre.’

14…Nxd4 15 exd4 Bxd4 16 Bf4

D.J.: ‘A saving move, as the rook can remove on retiring our queen; of course a draw is open to us by 16…exd3 17 Bxd6 dxc2 18 Bxf8 Bxa1 19 Rxa1 Kxf8.’

F.W.: ‘Don’t let us play for draw; where shall we play the queen; to b6?’

D.J.: ‘For some variations to c5 is best, but there are some where b6 is preferable.’

16…Qb6 17 Be3

D.J.: ‘If now 17…exd3 18 Qxd3 Bxe3 19 Rxe3 or Nxe3 Bd7, with even but uneventful game. Better at once –’

17…Bxe3 18 Nxe3

F.W.: ‘Shall we push the f-pawn, which can be recovered with perhaps some attack, instead of at once taking the pawn with the pawn?’

D.J.: ‘Yes; I think it will be all right.’

18…f4 19 gxf4

D.J.: ‘Now I wish at 16 that we had played …Qc5; we could then recover by …Nh5, but as we now stand the knight would attack our queen; therefore –’

19…Qd6 20 dxe4 Qxf4 21 Nd5

D.J.: ‘If we remove the queen, they play 22 f4, very strong, and if we take the knight, the c-pawn retakes, also very strong; but we can bring our queen’s rook into play.’

21…Nxd5

D.J.: ‘I think we ought not to have played this; 21…Qh4 would have been better. We should threaten …Ng4, if they captured the c-pawn; and if Ne7+, followed by Nf5, we could have re-played Qf4. Now the pawns will be very powerful.’

22 cxd5 Ra6 23 Re3

D.J.: ‘A very strong move, which settles the whole possibility of our getting a king’s-side attack.’

F.W.: ‘Shall we play 23…Rh6?’

D.J.: ‘I think to f6 is preferable, we shall have the rooks doubled; if to h6 they will play Rg3, defending everything, and our queen will not have quite the same liberty.’

23…Raf6 24 Ra2

D.J.: ‘Good, defending the f-pawn and threatening e5.’

F.W.: ‘I think 24…Qh6 would be good. They cannot then advance the pawn, nor play Rg3, nor take the c-pawn with the queen, because we should take the f-pawn with advantage.’

D.J.: ‘Yes, but 25 Qc3 settles the whole threat. I think 24…Rh6 better; if we play 24…Qe5 they would challenge queens.’

F.W.: ‘Why not try 24…Qh4, for if 25 Rg3 Rxf2 26 Qxf2 Rxf2 27 Rxf2, gaining queen and pawn for two rooks?’

D.J.: ‘They would be strong then. I like best 24…Rh6.’

(F.W.’s subsequent editorial note: ‘The disinclination of D.J. to the move of …Qh4 was good judgement; for the play might have been 24…Qh4 25 Rg3 Rxf2 26 Qxc7 R2f7 27 Qxa5 or if 26…Qf6 27 Rxg7+ Qxg7 28 Qxg7+ Kxg7 29 Rxf2.’)

24…Rh6 25 Rg3

F.W.: ‘Let us play 25…b6 and then bring out the bishop.’

D.J.: ‘I prefer 25…c6 to break up the centre.’

F.W.: ‘Rather risky.’

25…c6 26 Qc3

F.W.: ‘Very powerful; I do not like that.’

D.J.: ‘We defend –’

26…Rf7

D.J.: ‘Too hasty, a fatal move, we cannot now take the d-pawn, as the bishop is undefended; we ought to have played 26…g5, which would have preserved a quite defensible game.’

27 e5

D.J.: ‘Threatening to shut in the bishop, as well as to drive the rook; we must therefore play –’

27…Bf5 28 e6

F.W.: ‘Oh, the terrible pawns.’

D.J.: ‘Yes; we have a lost game, but try a few more moves, perhaps an opportunity of capturing the d-pawn may arise.’

28…Rc7

29 Rd2

D.J.: ‘A very fine move; we cannot escape from all the threats; if 29…Qd6 30 dxc6 Qe7 31 Qxg7+ Qxg7 32 Rd8 mate. If 29…cxd5 they can take 30 Rxg7+, etc.; but they might play 30 Rxd5, in which case we continue 30…Rf6, and if 31 Qxf6 Rc1+ 32 Bf1 Qxg3+ 33 hxg3 gxf6 34 Rxf5 and we are lost. Let us resign.’

F.W.: ‘We may as well see how they finish us off.’

29…cxd5 30 Rxg7+ Resigns.

F.W.: ‘Quite settles us, but we have had a good and enterprising game.’

Additional information (21 December 2007): Paul Buswell (Hastings, England) informs us that Womersley was mentioned in the minutes of a meeting of the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club on 15 September 1911. The Club decided who would represent it at the funeral and resolved to buy a wreath costing no more than one guinea.

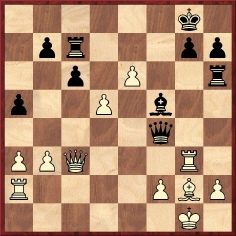

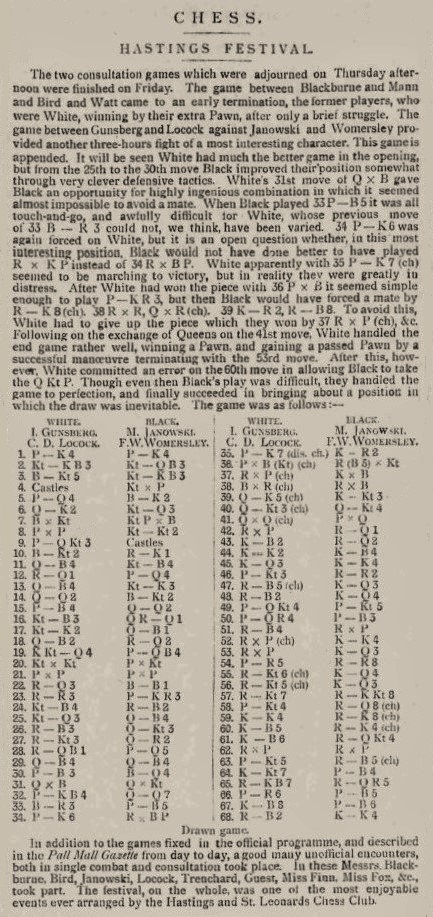

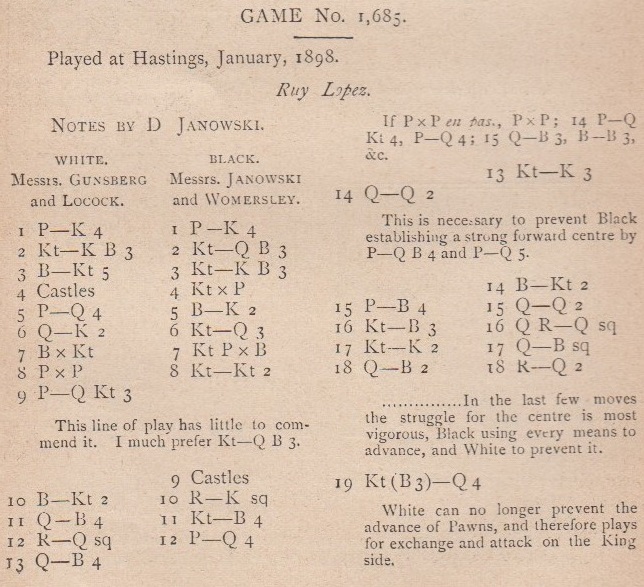

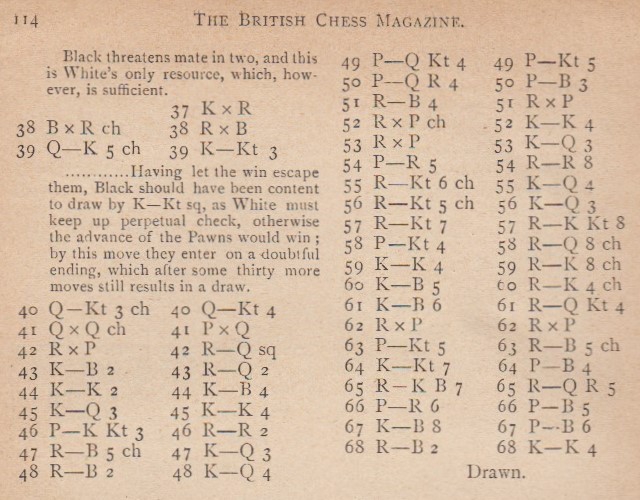

Another consultation game involving F.W. Womersley and Janowsky, against Gunsberg and Locock, was published on page 9 of the Pall Mall Gazette of 29 January 1898 (chess column by Gunsberg) and on pages 112-114 of the March 1898 BCM (annotations by Janowsky):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 bxc6 8 dxe5 Nb7 9 b3 O-O 10 Bb2 Re8 11 Qc4 Nc5 12 Rd1 d5 13 Qf4 Ne6 14 Qd2 Bb7 15 c4 Qd7 16 Nc3 Rad8 17 Ne2 Qc8 18 Qc2 Rd7 19 Nfd4 c5 20 Nxe6 fxe6 21 cxd5 exd5 22 Rd3 Bf8 23 Rh3 h6 24 Nf4 Rf7 25 Nd3 Qf5 26 Rf3 Qg6 27 Rg3 Qh7 28 Rc1 d4 29 Qc4 Qf5 30 f3 Bd5 31 Qxd5 Qxd3 32 f4 Qd2 33 Ba3

33...c4 34 e6 Rxf4 35 e7+ Kh7 36 exf8(N)+ Rfxf8 37 Rxg7+ Kxg7 38 Bxf8+ Rxf8 39 Qe5+ Kg6 40 Qg3+ Qg5 41 Qxg5+ hxg5 42 Rxc4

42...Rd8 43 Kf2 Rd7 44 Ke2 Kf5 45 Kd3 Ke5 46 g3 Rh7 47 Rc5+ Kd6 48 Rc2 Kd5 49 b4 g4 50 a4 c6 51 Rc4 Rxh2 52 Rxd4+ Ke5 53 Rxg4 Kd6 54 a5 Rh1 55 Rg6+ Kd5 56 Rg5+ Kd6 57 Rg7 Rg1 58 g4 Rd1+ 59 Ke4 Re1+ 60 Kf5 Re5+ 61 Kf6 Rb5 62 Rxa7 Rxb4 63 g5 Rf4+ 64 Kg7 c5 65 Rf7 Ra4 66 a6 c4 67 Kf8 c3 68 Rf2 Ke5 Drawn.

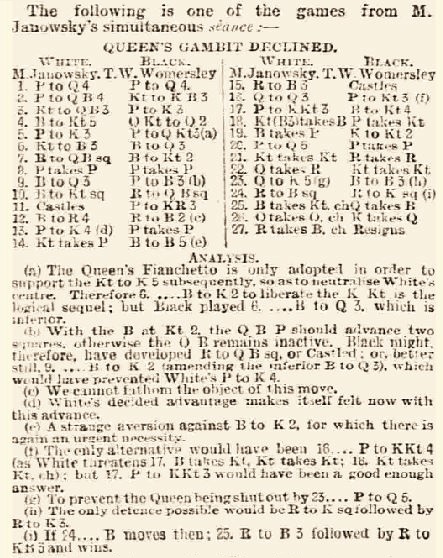

The game was played in Hastings on 27-28 January 1898. On 24 January Janowsky and Womersley had faced each other in the former’s 29-board simultaneous exhibition. Below is the game as published on page 7 of the Standard, 1 February 1898:

Black’s initials T.W. were amended to F.W. when the game was given on, for instance, page 2 of the 19 February 1898 edition of the Newcastle Courant.

1 d4 d5 2 c4 Nf6 3 Nc3 e6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 b6 6 Nf3 Bd6 7 Rc1 Bb7 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Bd3 c6 10 Bb1 Rc8 11 O-O h6 12 Bh4 Rc7 13 e4 dxe4 14 Nxe4 Bf4 15 Rc3 O-O 16 Qd3 g6 17 g3 Bg5 18 Nfxg5 hxg5 19 Bxg5 Kg7

20 d5 cxd5 21 Nxf6 Rxc3 22 Qxc3 Nxf6 23 Qe5 Bc6 24 Rc1 Re8 25 Bxf6+ Qxf6 26 Qxf6+ Kxf6 27 Rxc6+ Resigns.

(9657)

Regarding consultation games, see too C.N. 9669.

A draw between H. Colborne and F.W. Womersley was published on page 167 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 14 October 1885. Pages 383-384 of the 17 February 1886 issue had the following win by Womersley against A. Wisden in a handicap tournament of the Hastings and St Leonards Club in which he gave his queen in exchange for Black’s rook on a8 and pawn on f7:

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 c3 d6 5 h3 h6 6 b4 Bb6 7 a4 a6 8 a5 Ba7 9 b5 Nb8 10 d4 Qe7 11 dxe5 dxe5 12 b6 cxb6 13 Ba3 Qc7 14 axb6 Bxb6 15 Nbd2 Nc6 16 O-O Na5 17 Bd5 Nf6 18 c4 Nxd5 19 cxd5 Kf7 20 Rfc1 Qb8 21 Bb4 Qa7 22 Nxe5+ Kf6 23 Nd3 g5 24 Bxa5 Rd8 25 g4 Bd7 26 Nf3 Bb5 27 Bc3+ Ke7 28 Bb4+ Kf7 29 Nfe5+ Ke8 30 Rc3 Bd4 31 Rc7 Bd7 32 Rac1 Bb6 33 Nc6 Bxc6 34 Re7+ Kf8 35 Rxb7+ Ke8 36 Rxa7 Bxa7 37 dxc6 Rc8 38 Ne5 Bb6 39 Nc4 Bc7 40 Bd6 Bd8 41 c7 Bxc7 42 Nb6 Resigns.

See too Royal Walkabouts.

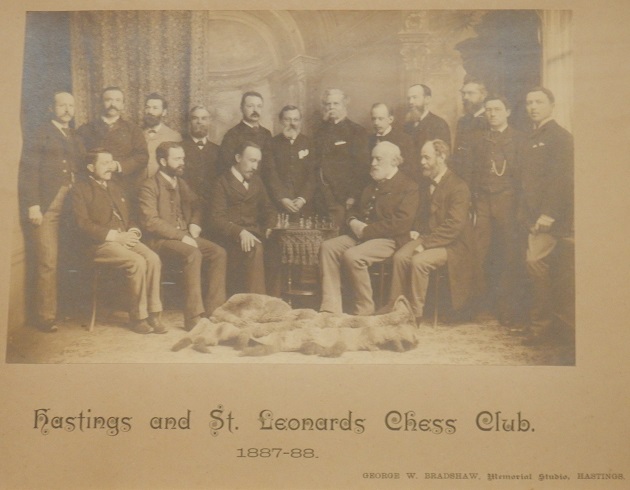

This photograph has been provided by Tim Jones (Liverpool, England), from the memorabilia of his grandfather Richard Jones, who is second from the left in the front row. It seems that the player seated by the black pieces is F.W. Womersley.

(11214)

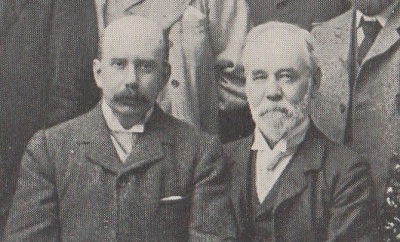

Below is a detail of the group photograph of ‘the Hastings Club Touring Team, 1901’ which was the frontispiece to the October 1901 BCM:

Herbert Edward Dobell and Frederick William Womersley

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘The birth indexes of the General Register Office show that Frederick William Womersley was born in the registration district of Hastings during the quarter ending 30 September 1839 (volume 7, page 328), his mother’s maiden name being Shaw. He seems to have been called William in the family, since he is listed by that forename in the censuses of 1841 and 1851. In 1841 the family was at Albion Place, Hastings, his father, Charles Womersley, being described as an upholsterer, with Caroline Womersley (aged 30-34), and four children, of whom William was the youngest (National Archives, HO 107/1107). In 1851, at 3 and 4 York Place, his father was described as “Upholsterer Auctioneer”, born at Tenterden, Kent; in the place of Caroline, who had died since 1841, was Catherine Womersley, aged 37; William was a “scholar” at that time (National Archives, HO 107/1635, folio 69). By 1861 he had become an upholsterer’s clerk (National Archives, RG9/560, folio 80), and in 1881 an upholsterer (National Archives, RG 11/1024, folio 39). During the quarter ending September 1859, Womersley had married Mary Ann Long in the registration district of Hastings (volume 2b, page 17). The 1881 census indicates that she was born in Bexhill, and that at that time they had two children, Emily and Godfrey. Mary Ann died in the March quarter of 1899 (Hastings, volume 2b, page 16), and in the same year the National Probate Calendar shows that Womersley also lost his father (full name Charles John Womersley). In the 1911 census, a few months prior to his death, Frederick William Womersley was shown as a widower, professional accountant and public auditor, living with his daughter, Emily, 50, who was single and served as housekeeper (National Archives, RG 14/4747).’

Our correspondent has also provided some information about Womersley’s killer, Joseph James, from page 7 of the Western Daily Press, 9 September 1931:

‘Murderer Dies at Broadmoor

The death has occurred at Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum of Joseph James, a chemist (71), who at the Sussex Assize, in December 1911, was sentenced to be detained during his Majesty’s pleasure on a charge of wilful murder.’

Mr Townsend adds:

‘Confirmation of Joseph James’ death is provided by the death indexes of the General Register Office, in an entry in the September quarter of 1931 in the registration district of Easthampstead (vol. 2c, page 416), his age also being given as 71.’

(11290)

See also Chess and Murder.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.