Edward Winter

George Stern (Canberra, Australia) writes:

‘When I came across the following passage about F.K. Young by Lawrence J. Fuller on page 503 of Volume I of The Best of Chess Life and Review, my eyebrows went up in disbelief:

“Mr Young was a contemporary of Steinitz, Zukertort and the American champions Mackenzie and Pillsbury, from all of whom he won games which he credited to his system.”

Can it really be that F.K.Y. defeated Steinitz, Zukertort, Mackenzie and Pillsbury? If he did, why is the fact not better known? Why, indeed, did Young himself not boast about it – as a success of his system – in the lattermost of his “Strategetics” series, Chess Strategetics? There are all sorts of other puffery in the “Introductory” to that book, but no mention of victories over world-class contemporaries. Incidentally, I notice that in that book Young made this claim:

“The synthetic method of chessplay ... early received the indorsement [sic] of Emmanuel [sic] Lasker, who, in a personal letter to Mr Edwin C. Howell, collaborator in Minor Tactics, stated that the new method of chess play ‘was replete with logic and common sense’.”

I wonder too whether Young’s claim about Lasker is true. Can you or your correspondents shed any light on either of these matters?’

Finding victories by Young is not easy, though his obituary on page 10 of the January 1932 American Chess Bulletin said that ‘in the middle ’80s, contemporary with George Hammond [sic –G.H. died in 1881], Preston Ware, C.F. Burrille [sic] and Charles B. Snow, he was one of the finest players in America’. In an off-hand queen’s knight odds game in Boston in April 1885 Young was defeated by Steinitz. The game appeared on pages 217-218 of the July 1885 issue of the International Chess Magazine. Steinitz described his opponent as ‘one of the strongest local players’ and believed that he ‘would be too strong for such odds in a serious contest’.

None of the standard sources seems to contain any games between Pillsbury and Young, but, by coincidence, Richard Lappin (Jamaica Plain, MD, USA) has just sent us a copy of a 1972 booklet Chess Was Front Page News ... 80 Years Ago, subtitled ‘A Salute to Harry N. Pillsbury’. This gives the following game, played before Pillsbury ‘found himself’:

Franklin Knowles Young – Harry Nelson Pillsbury1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 d4 Bd7 5 O-O f6 6 c3 Nge7 7 Nh4 g6 8 f4 Bg7 9 f5 gxf5 10 exf5 O-O 11 Qg4 Kh8 12 Rf3 Rg8 13 Rh3 Bh6 14 Qh5 Bxc1 15 Ng6+ Kg7 16 Qxh7 mate.

Not exactly the kind of game with which Young could have propagated his singular teaching system.

The booklet also reproduces an article by John Barry entitled ‘Chess in Boston 1857-1937’ which has a couple of paragraphs on Young:

‘Then entered Franklin K. Young, who developed until he defeated Ware in a match and claimed the championship of New England. I believe this is the genesis of the title.

In later years, when somewhat retired from chess in 1892, Young began his famous series of books on [sic] the vocabulary of military terms – a science in which he was notably skilled for a layman. Of these books, his first Minor Tactics is one of the finest contributions to the literature of chess and the most orderly guide for a tyro student.’

(1886)

Richard Lappin writes that a search of Young’s The Grand Tactics of Chess (Boston, 1905) turned up numerous Young victories, including the following:

‘1) Mackenzie-Young, Boston Chess Club, 16 June 1884.

2) P. Ware and Young-Zukertort, Boston Chess Club, 17 January 1884.

3) Young-PilIsbury, Boston Press Club, 26 January 1893 (C.N. 1886) ... as well as draws (?) as follows:

4) Steinitz-Young, Boston Chess Club, 9 July 1886.

5) Young-PilIsbury, Boston Press Club, 13 January 1893.

The Field Book of Chess Generalship (New York and London, 1923) also contains many Young victories (unfortunately mostly undated and unplaced):

6) Young-Zukertort.

7) Mackenzie-Young, Boston Chess Club, exhibition game.

Also, the following game fragment is found:

8) Steinitz-Young (an alternate finish, this time victorious, to the afore-mentioned 9 July 1886 game ...).

It seems clear that these were exhibition games, which might account for F.K.Y.’s reluctance to broadcast his success. I have no insight, however, into the alternative finishes to the Steinitz-Young game.’

This last point is a curious matter. Here is the game as given on pages 443-444 of The Grand Tactics of Chess:

Wilhelm Steinitz – Franklin Knowles Young1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Ne5 Qh4+ 6 Kf1 Nh6 7 d4 f3 8 Nc3 fxg2+ 9 Kxg2 Qh3+ 10 Kg1 Nc6 11 Bf1 Qh4 12 Bf4 d6 13 Bg3 Qg5 14 Nc4 Bg7 15 Bf2 f5 16 Nd5 O-O 17 Nxc7 Rb8 18 c3

18...g3 19 hxg3 Ng4 20 Qd2 f4 21 gxf4 Qe7 22 Nd5 Qxe4 23 Bg2 Qg6 24 Re1 Be6 25 Nde3 Rxf4 26 Bg3

26...Rxd4 27 cxd4 Bxd4 28 Rh4 h5 29 Rxg4 Qxg4 30 Bf2 Qf4 31 Nd5 Qxf2+ 32 Qxf2 Bxf2+ 33 Kxf2 Rf8+ 34 Kg3 Nd4 35 Nxd6 Rd8 36 Ne4 Kg7 37 Nec3 b6 38 Nf4 Bf7 39 Kh4 Kh6 40 Re5 Rg8 41 Bd5 Rg4+ Drawn.

But on pages 138-139 of Field Book of Chess Generalship it is claimed that there was a much prettier finish and a different result:

26...Nge5 27 dxe5 Qxg3 28 Qe2 Rbf8 29 exd6 Bxc4 30 Nxc4 Nd4 31 cxd4 Bxd4+ 32 Ne3

32...Rf1+ 33 Rxf1 Bxe3+ 34 Qxe3 Qxe3+ 35 Kh2 Qe5+ 36 Kh3 Rxf1 37 Rxf1 Qxd6 and Black won.

(1911)

Consultation games often lack sparkle, but the next game is a definite exception.

Preston Ware and Franklin Knowles Young – Johannes Hermann Zukertort1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O dxc3 8 Qb3 Qf6 9 e5 Qg6 10 Nxc3 Nge7 11 Ba3 O-O 12 Rad1 b5 13 Bd3 Qg4 14 h3 Qe6 15 Bxh7+ Kh8 16 Nd5 b4 17 Ng5 Nxd5 18 Nxe6 fxe6 19 Bb1 bxa3

20 Qd3 (‘The allies had intended to play 20 Qc2, and upon Black’s replying ...Rf5, which is forced, 21 Rxd5, winning easily. One of them, however, nervously called out Qd3.’ – C.E. Ranken.) 20...Rf5 21 g4 Nxe5 22 Qe4 Nf3+ 23 Kh1 Ng5 24 Qg2 Rf3 25 Rxd5 exd5 26 Rd1 Rxh3+ 27 Kg1 Nf3+ 28 Kf1 Ba6+ 29 Bd3 Nh2+ 30 Kg1 Rxd3 31 Rxd3 Bxd3

32 Qxd5 (‘Black must have overlooked this move, by which, curiously enough, every one of his pieces is attacked, and he must lose two of them.’ – C.E. Ranken.) 32...Rf8 33 Kxh2 Rxf2+ 34 Kg3 Bb6 35 Qxd3 Rxa2 36 Qxd7 Rf2 37 Qe8+ Kh7 38 Qh5+ Kg8 39 g5 Kf8 40 g6 a2 41 Qh8+ Ke7 42 Qxg7+ Kd6 43 Qc3 Ke6 44 Qh8 Rf6 45 g7 Rg6+ 46 Kh3 Kd7 47 Qh7 Rh6+ 48 Qxh6 a1(Q) 49 Qd2+ Ke7 50 g8(Q) Qh1+ 51 Qh2 Qf3+ 52 Qhg3 Qh1+ 53 Kg4 Qd1+ 54 Kg5 Qc1+ 55 Kh5 Qd1+ 56 Q8g4 Black resigns.

(‘The whole game is one of the most interesting that we ever played over.’ – C.E. Ranken.)

Source: BCM, July 1884, pages 275-276.

Concerning move 20, in a footnote on page 81 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves we commented:

‘A different version was given by Young on page 440 of The Grand Tactics of Chess. He referred to ‘the miscalling, by the teller, of White’s 20th move.’

(2115)

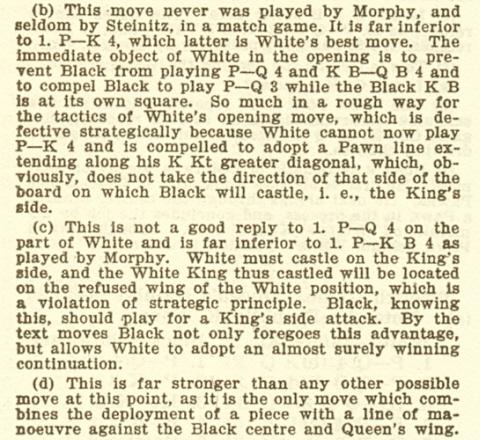

Discussing the Ruy López on page 359 of The Grand Tactics of Chess (Boston, 1905), Franklin K. Young had the following to say about 3…a6:

‘…bad, inasmuch as the left minor crochet is of no utility in a minor right oblique refused, nor in a full front unopposed by the major oblique echeloned.’

We have seen the light.

(Kings, Commoners and Knaves, page 168)

‘A preface is sometimes the best part of a book’, wrote E.J. Winter-Wood in his preface (page iii) to Chess Souvenirs (London, 1886). Those words came back to mind as we were leafing through Field Book of Chess Generalship by Franklin K. Young, whose preface (page v) begins:

‘For some years past, I have had frequent requests from chessplayers to write a little book, giving in simple language a clear and easy method for utilizing in practice the theory of chessplay laid down in my previous works on the game.’

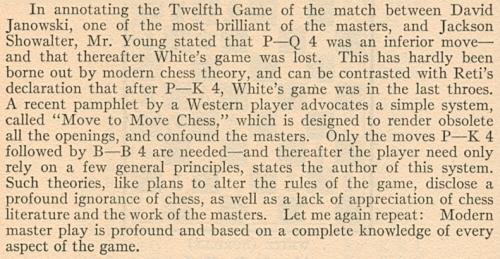

A measure of how Young fared is provided by the following (wholly typical) passage on page 119:

‘The normal formative processes of a Logistic Grand Battle consist, first, in Echeloning by RP to QR4 and then in Aligning the Left Major Front Refused en Potence by the development of QKtP to QKt5, followed by Doubly Aligning the Left Major Front Refused and Aligned by developing QRP to QR5.

The final and decisive development in the formative process of a Logistic Grand Battle is the transformation of the Left Refused Front Doubly Aligned into a Grand Left Front Refused and Echeloned by the development of QRP to QR6.’

(3149)

Tartakower is one of the most difficult chess writers to translate into English (among others are A. Nimzowitsch and F.K. Young).

(4437)

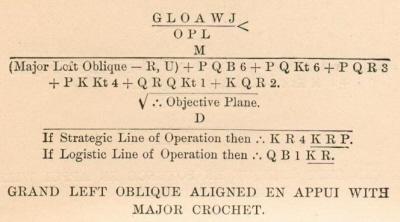

Henrique Marinho (Curitiba, Brazil) notes that Chapter X of Modern Chess by Barnie F. Winkelman (Philadelphia, 1931) has a discussion of Franklin K. Young and that in Chapter XX (page 180) the following paragraph appears:

‘In the work of Mr F.K. Young mentioned in a previous chapter, certain recognized formations were advocated by him, but the principles underlying the proper co-ordination of the pieces were never touched on. Mr Harold Perrin, a strong amateur of Boston, sensed the real situation when he stated that chess is not a status, but a flux, and this emphasis upon the ever-changing relations of the forces rightly describes the real situation.’

Information about the relevant writings of Perrin would be welcomed.

(6444)

From page 106 of Winkelman’s above-mentioned book:

As regards the reference to Réti, see Breyer and the Last Throes.

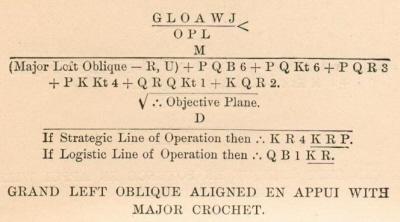

The following notes by Young to the Janowsky v Showalter match-game (concerning, respectively, 1 d4, 1...d5 and 2 c4) appeared on page 362 of the February 1899 American Chess Magazine:

(6445)

A staunch defender of Franklin K. Young was Charles W. Warburton, in his book My Chess Adventures (Chicago, 1980). See, in particular, pages 2, 13-14, 42 and 94-96. Below is a sample passage from page 95:

Warburton did not name the Englishwoman, but she was Eileen Tranmer, on page 187 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

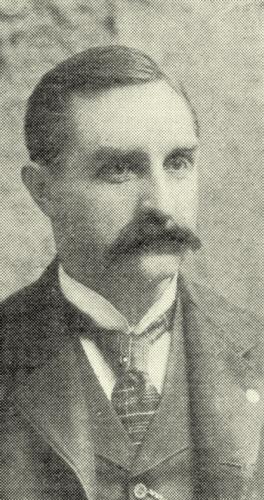

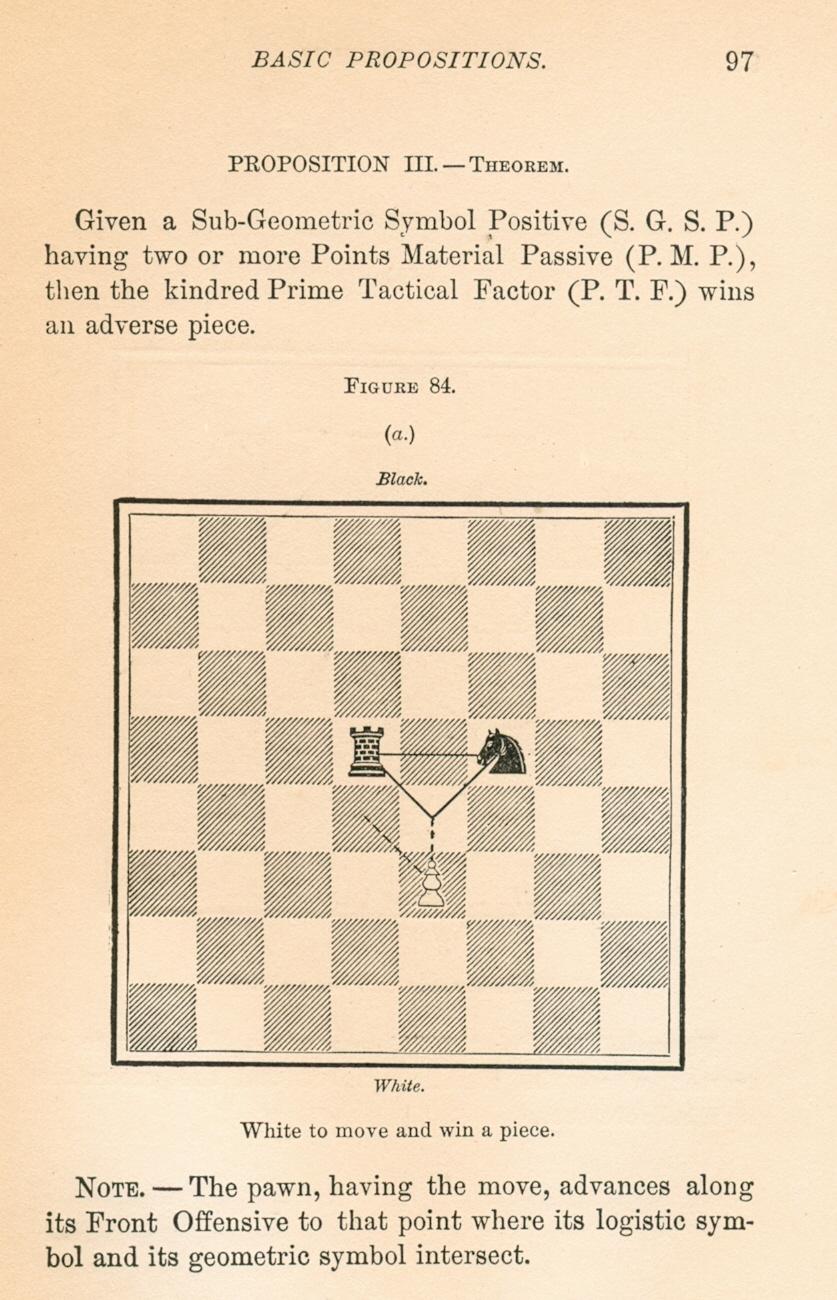

This photograph of F.K. Young comes from page 71 of The Rice Gambit (souvenir supplement to the 1905 American Chess Bulletin):

(6447)

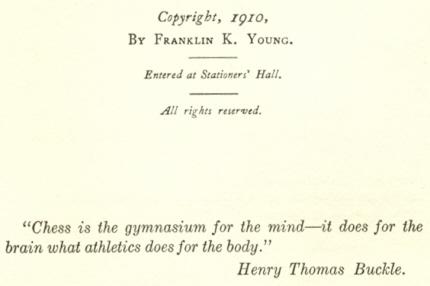

For reasons unknown, the imprint page of volume one of Chess Generalship by Franklin K. Young (Boston, 1910) credited a famous observation to H.T. Buckle:

Young had written similarly on page 408 of the Pall Mall Magazine, 1897 (volume 11), in an article entitled ‘The Major Tactics of Chess’:

(6453)

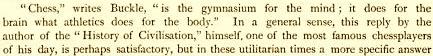

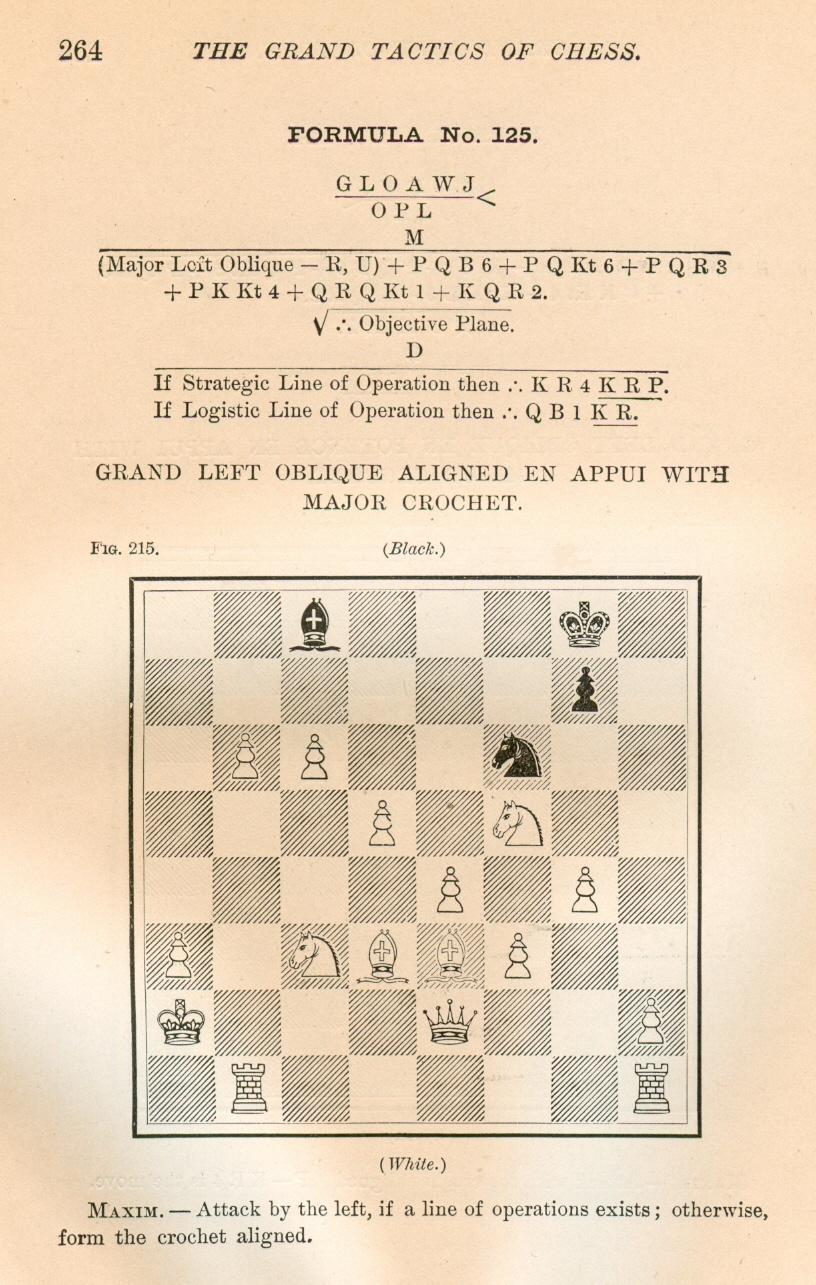

Another sample page, from The Major Tactics of Chess (Boston, 1909):

Page 10 of the January 1932 American Chess Bulletin:

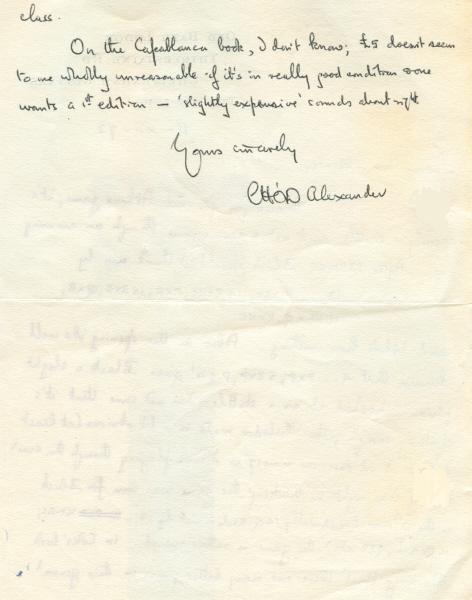

An oft-discussed case of duplication in chess concerns the games Young v Doré, Boston, 1892 and Atkins v Jacobs, London, 1915: 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Nxe4 6 O-O Nd6 7 Nxc3 Nxc4 8 Re1+ Be7 9 Nd5 Nc6 10 Bg5 f6 11 Rc1 b5 12 Rxc4 bxc4 13 Ne5 fxg5 14 Qh5+ g6 15 Nf6+ Bxf6 16 Nxg6+ Qe7 17 Rxe7+ Bxe7 18 Ne5+ Kd8 19 Nf7+ Ke8 20 Nd6+ Kd8 21 Qe8+ Rxe8 22 Nf7 mate.

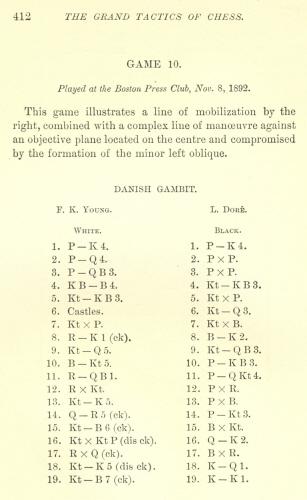

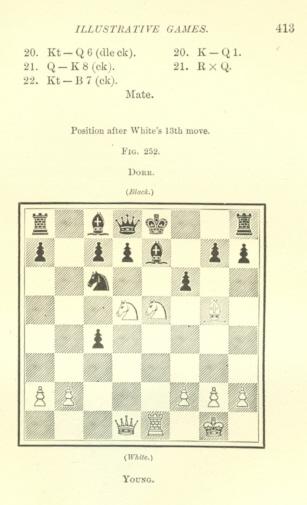

Young published the game on pages 412-413 of his book The Grand Tactics of Chess (Boston, 1898 and 1905):

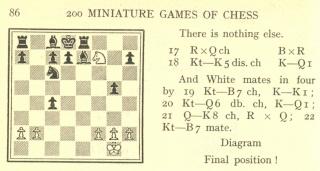

Regarding the Atkins v Jacobs game, we are aware of no publication earlier than pages 85-86 of 200 Miniature Games of Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1941):

The duplication of the game-score was noted by Walter Korn in an article ‘The Finishing Touch’ on pages 74-75 of the March 1960 Chess Review. He commented:

‘The question is was Atkins in the London Championship knowingly copying from Franklin K. Young, while Jacobs unwittingly aided and abetted him?’

The two games were also included on pages 188-190 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974). Under the heading ‘Chernev experiences psychic phenomenon’ the author stated that while playing over the Young game he had received a telephone call from a friend regarding the Atkins version.

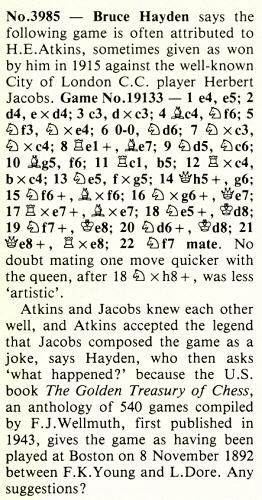

From K.Whyld’s Quotes and Queries column on page 406 of the September 1979 BCM:

It will be noted that no evidence, let alone proof, was proposed for the suggestion that the game was a joke.

On page 475 of the October 1991 BCM Whyld mentioned again Hayden’s reference to a joke involving H.E. Atkins and H. Jacobs but then speculated as follows:

‘My conclusion is that the game was played twice; Young-Doré, and M.G. Atkins-Jacobs, London Championship 1915-16. Michael Glover Atkins was killed in the war towards the end of 1916, and was not around to give his account of the game, when it became controversial.’

M.G. Atkins did indeed defeat Jacobs in the 1915-16 City of London Championship, as is shown by the crosstable on page 175 of the May 1916 BCM. Atkins’ obituary was published on page 401 of the December 1916 BCM and on pages 65-66 of the December 1916 Chess Amateur. Page 98 of the January 1917 Chess Amateur stated: ‘Though slightly over military age, he patriotically volunteered for service, and has now met his death.’

As shown above, du Mont’s book had only the surnames Atkins and Jacobs in the game heading. The respective forenames Henry Ernest and Herbert appeared solely in the index, and the possibility of a mix-up between two players named Atkins cannot be excluded. In C.N. 2623 (see page 164 of A Chess Omnibus) we wrote in another context:

‘Pages 451-452 of the Chess Amateur, December 1911 had a description of Capablanca’s first two simultaneous exhibitions in England (at the City of London Chess Club on 15 November and at the Imperial Chess Club two days later). In the first display his opponents included J.H. Blake, H.G. Cole, R.J. Loman and O.C. Müller, but it would seem that The Unknown Capablanca by D. Hooper and D. Brandreth erred by stating (on page 146) that among the participants was also “one grandmaster, H.E. Atkins”. Neither the Chess Amateur report nor the account in the BCM (December 1911 issue, pages 474-475) mentioned H.E. Atkins, but both stated that a board was taken by M.G. Atkins.’

It may be added that M.G. Atkins’ obituary on page 401 of the December 1916 BCM said that ‘he was one of those who defeated Capablanca in his simultaneous exhibition at the City club, on 13 October 1913’.

On 11 December 1973, a couple of months before he died, C.H.O’D. Alexander wrote us a letter about the Danish Gambit game:

By ‘Coles’, of course, Cozens was meant. See too in this connection page 587 of the December 1979 BCM, which also referred to Chernev and his ‘psychic phenomenon’.

In the early twentieth century the Young v Doré game received two small bursts of publicity, in 1903 and 1915. A number of magazines in 1903 reproduced the score from The Times (exact source?), an example being page 202 of the May 1903 issue of the Belgian periodical Revue d’échecs:

It will be noted that the venue was specified as Philadelphia rather than Boston.

The game’s publication in The Times in 1903 was also mentioned by A. Keiner of Meiningen on page 302 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 24 October 1915. Young v Doré had been given on page 287 of the 10 October 1915 magazine, taken from the BCM (page 281 of the August 1915 issue). It was contributed to the BCM by C.F. Davie of Victoria, British Columbia. No source was supplied, but on pages 357-358 of the October 1915 BCM he gave two further games (Young v Pillsbury and Young v Snow) which are also in Young’s book The Grand Tactics of Chess. Can it really be a coincidence that the year (1915) in which Young v Doré was quite widely published was the same year in which, according to du Mont, the game Atkins-Jacobs occurred?

About L. Doré we can offer no biographical information, but the following passage on pages 58-59 of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978) is worthy of note and investigation:

‘Franklin Young’s games were pretty ones, but he played another significant role as well. He was a member of the Boston group of chess enthusiasts, consisting of J.F. Barry, C.F. Burille, L. Dore, H.N. Stone, P. Ware Jr., and others, who called themselves “The Mandarins of the Yellow Button”, a minute allusion to the German seven-master group, “The Pleiades”, of the 1850s.’

In view of the multiple loose ends, it would seem unwise to put forward any conclusions at present about either Young v Doré or Atkins v Jacobs.

(7096)

Alan Smith (Manchester, England) mentions that an Atkins v Jacobs game was published on page 32 of the Illustrated London News, 1 January 1916:

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Nf6 3 d4 Qxd5 4 Nc3 Qa5 5 Nf3 c6 6 h3 Bf5 7 a3 Nbd7 8 Bd2 e6 9 Bc4 Qc7 10 Be3 Bd6 11 Bd3 Bg6 12 Qd2 O-O 13 Bxg6 hxg6 14 Ng5 Rfd8 15 Nce4 Be7 16 Nxf6+ Nxf6 17 Bf4 Qb6 18 c3 c5 19 dxc5 Bxc5 20 Qe2 Rd5 21 b4 Be7

22 c4 Qd4 23 O-O Qxf4 24 cxd5 Qxg5 25 dxe6 Qd5 26 exf7+ Qxf7 27 Rad1 a5 28 Qb5 axb4 29 axb4 Bf8 30 Rd4 Re8 31 f3 Qe6 32 Rfd1 Qe3+ 33 Kh1 Nh5 34 Qd5+ Kh7 35 Rh4 Re6 36 Qd3 Qg5 37 Rg4 Qe5 38 Rh4 Bd6 39 f4 Qf5 40 Qxf5 gxf5 41 Rxh5+ Resigns.

The heading was: ‘Game played in the Championship Tournament of the City of London Chess Club, between Messrs G. [sic] Atkins and H. Jacobs.’

(7147)

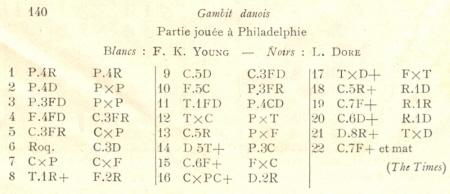

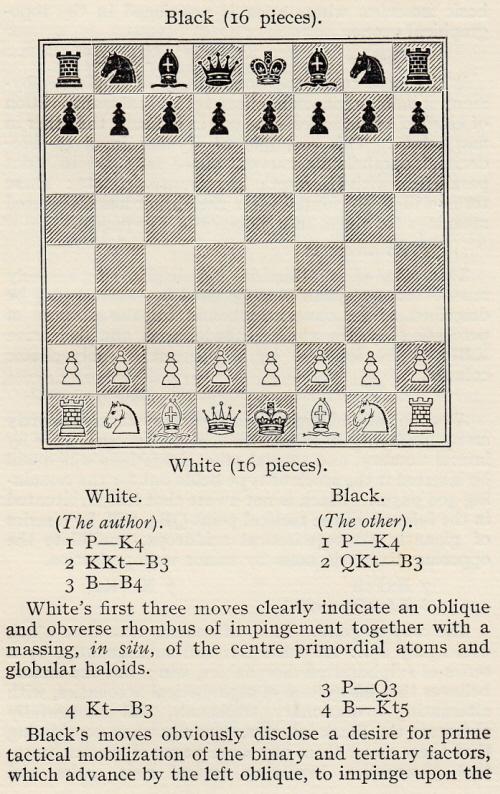

A parody of Young from pages 74-77 of Chess Chatter & Chaff by P.H. Williams (Stroud, 1909):

(8790)

From page 345 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

‘Some players talk a better game of chess than they play. In Young’s case the reverse was true.’

From page 406 of the September 1979 BCM (Quotes and Queries item 3986 by Kenneth Whyld):

‘The mention of Franklin Knowles Young (1857-1931) reminds me of a bon mot which may be new to readers. Young wrote several weird chess books which no doubt deceived military theoreticians into believing that they understood chess. His fellow American, Clarence Seaman Howell (1881-1936) wrote of Young’s “theories of that vague and dreamy and word-opulent character which abound in art, but are unwholesome in chess”. This led to a challenge to a duel over the chess-board. “As to the matter of stakes”, said Young, “you can put your money in your pocket. When I play for money I play poker.” Howell said “I admire your wisdom in preferring to back your luck rather than your skill.”’

Two points stand out: the satisfying chess-poker quip and the troubling absence of any source for anything.

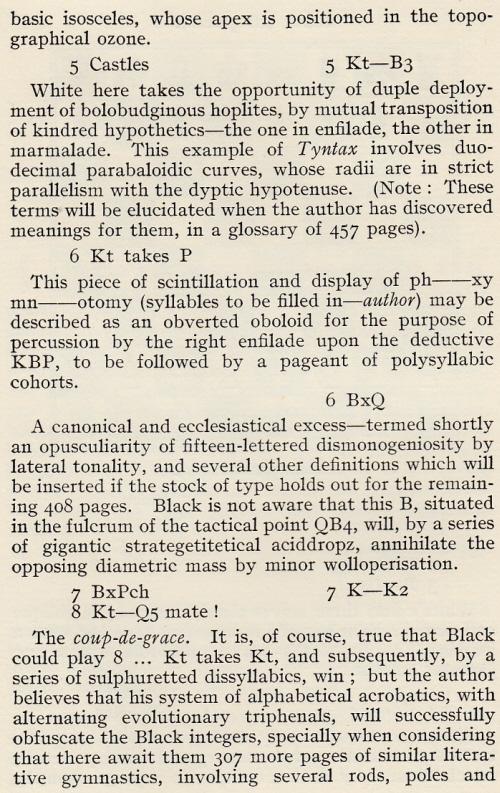

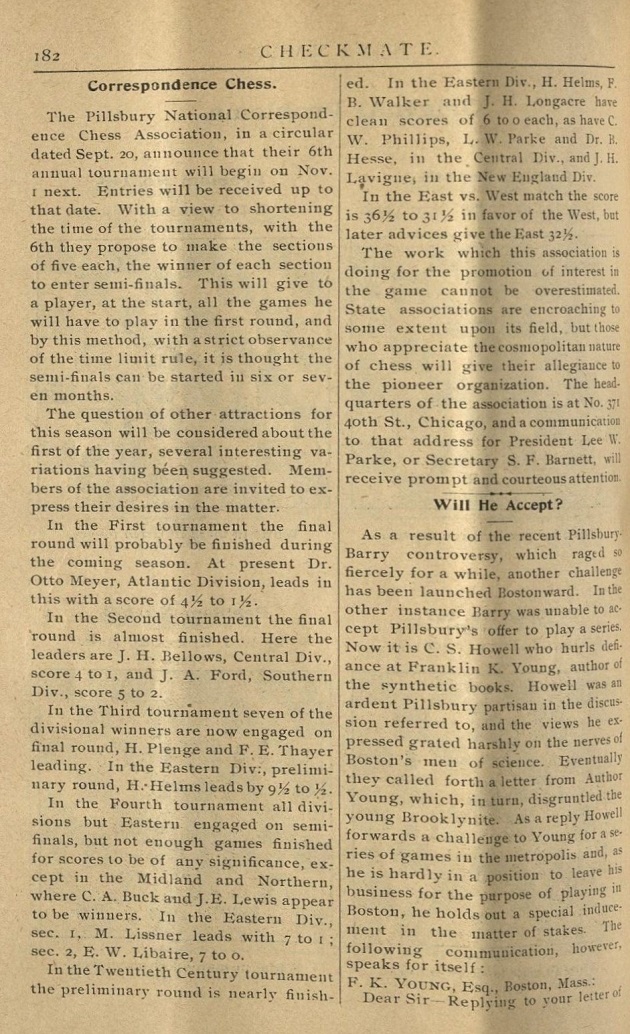

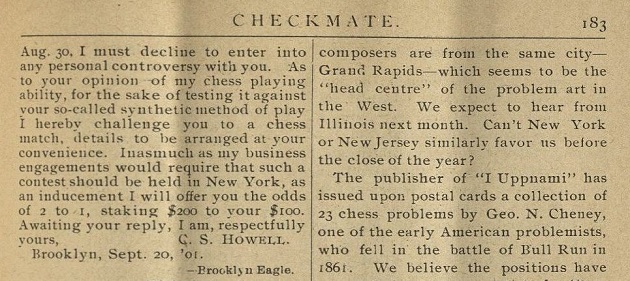

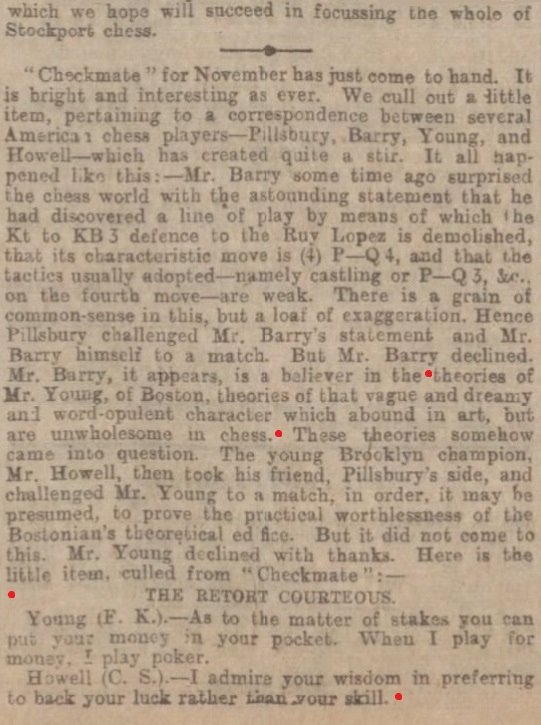

For a documented account, page 199 of the November 1901 issue of Checkmate is the first port of call:

The account of the Pillsbury-Barry controversy was the sequel to what had appeared on pages 182-183 of the October 1901 issue of the Canadian magazine:

Acknowledgement for the Checkmate scans: the Cleveland Public Library.

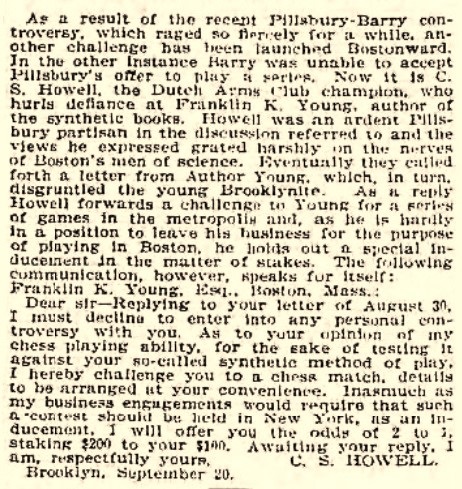

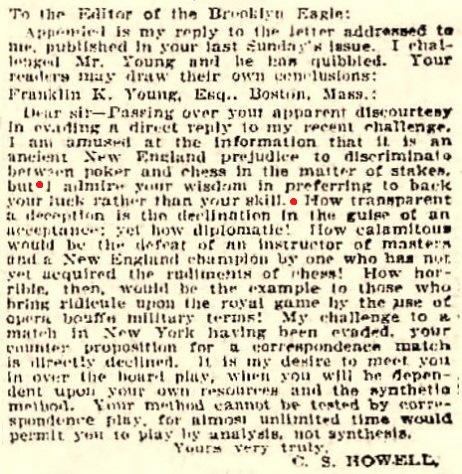

Below is the letter from Howell to Young as published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 September 1901, page 32:

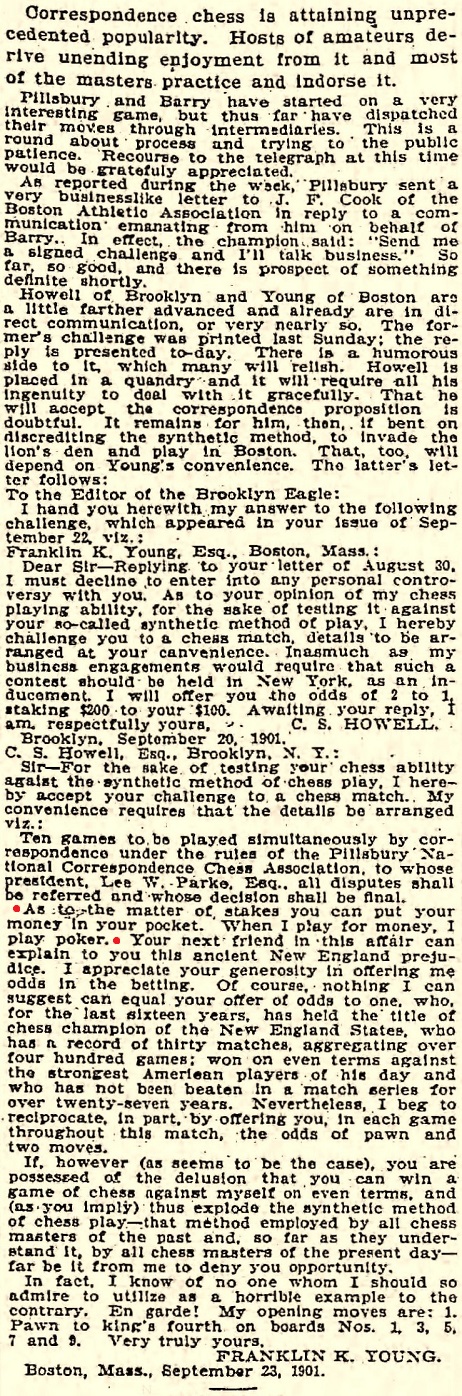

Subsequent editions of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle included these items with the chess and poker comments:

29 September 1901, page 20

20 October 1901, page 23

None of this explains why K. Whyld indicated that the words ‘theories of that vague and dreamy and word-opulent character which abound in art, but are unwholesome in chess’ were written by Howell and led to the challenge.

The BCM item contained no reference to Emanuel Lasker, yet it was the world champion who wrote the following in his column on page 6 of the Manchester Evening News, 13 November 1901:

Tailpiece: the Lasker column was mentioned by John Roycroft on page 909 of the October 1996 issue of EG:

In an uncharacteristic mistake, the final section, ‘The Retort Courteous’, in the Manchester Evening News was apparently misinterpreted by EG as being Lasker’s answers to two correspondents.

(12026)

Addition on 9 December 2024:

Annotating a game in which he was Black against E.M. Jackson in the Third Anglo-American cable match, F.K. Young wrote after 1 e4 e6:

‘This inferior defence was adopted on account of the fast time limit.’

Source: American Chess Magazine, March 1898, page 582.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.