When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [4] | next >> | Current column |

Our book A Chess Omnibus was published in June 2003.

Unbelievable but true: we have still been unable to secure from

the publisher, Mr Hanon Russell, a signed, hard-copy contract,

despite innumerable reminders sent to him over a long period and

several promises received from him.

Simon Browne (Chelsea, Australia) mentions that page 158 of the 3/1999 Quarterly for Chess History gives a table of Milan Vidmar’s chess record which states that in 1936 he defeated Reshevsky in a match +3 –2 =1. Our correspondent comments that Reshevsky was regarded at the time as a possible world championship contender but that the book Samuel Reshevsky by Stephen W. Gordon (Jefferson, 1997) does not refer to the match.

We offer a few remarks. The entry on Vidmar in the second edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess (page 441) also suggests that he won a formal match against Reshevsky in 1936, but he did not. The encounters were merely a series of six quick games, as Vidmar himself noted on page 535 of his memoirs, Pol stoletja ob šahovnici (Ljubljana, 1951): ‘Tam mi je bil pripravil presenečenje: z Reshevskym sem moral igrati 6 brzih partij. Zmagal sem s 3½:2½.’

Vidmar’s visit was reported on page 225 of the October 1936 Chess Review, which described the games against Reshevsky as ‘offhand’:

‘Soon after the Nottingham Congress Dr Milan Vidmar sailed for the United States. In the course of his short stay he quite naturally mixed a little chess with his engineering activities – a simultaneous exhibition at the Capital City Chess Club in Washington, DC; offhand games against Denker and Kashdan at the Manhattan Chess Club and Reshevsky at the Marshall Chess Club – and voiced his opinions on a variety of chess topics.

He believes that in a match between the United States and Russia the American players would be victorious; that the younger masters are not better than the older masters but that they can stand more punishment; that Fine has reached the peak but Reshevsky still has unplumbed possibilities; that Kashdan is the most talented player in America.’

Lasker and Vidmar, Nottingham, 1936

The same Capablanca photograph was published opposite page 244 of the December 1925 issue of L’Echiquier:

The Alekhine-Capablanca picture having been demonstrated to be a fake, we hope that it will no longer appear in books (such as the illustrated editions of the first volume of Kasparov’s Predecessors series) or on the Internet (such as the Capablanca gallery at Kasparov’s ‘chesschamps’ website).

With regard to the mystery concerning Lipschütz’s first name, Anders Thulin (Malmö, Sweden) has checked the website www.ancestry.com, which includes computerized lists of passengers to New York. He reports:

‘Lipschütz participated in the London, 1886 tournament, which ended on 29 July. The passenger lists should consequently feature a Lipschütz, arriving in New York in August or possibly September that year. They show that a Mr S. Lipschutz, aged 25, arrived in New York on 18 August 1886 on the ship Wisconsin from Liverpool.

This is presumably our Lipschütz, even though he seems slightly older than expected; he should be 22-23 years of age if he was born in 1863. But unfortunately there is only the initial S., and not a full name. No occupation, just “gent”.

According to the biographical feature in the Chess Monthly (December 1891, page 98), Lipschütz emigrated to the US when aged about 17½; this means around 1880, assuming that he was indeed born in 1863. Thus, another list entry should exist from that time.

There is a record stating that Salom. Lipschutz, 19 years old, born in Hungary, arrived in New York on 4 September 1880 on the ship Cimbria from Hamburg and Le Havre. Again, he is slightly older than expected, but seems to be the same age as the Lipschütz from 1886.

A check for other Lipschützes – particularly anyone named Simon or Samuel – produces nothing quite as good for these dates. (One “Samuel Lipschütz”, born around 1861, a turner, arrived on 12 August 1891, on the ship State of Nebraska, apparently via Glasgow from Russia. A “Simon Lipschütz”, a worker, from Galicia, aged 28, arrived on 8 January 1884, from Hamburg.)

On the assumption that S. Lipschütz did enter the United States of America through New York (almost certain), and was aged 19 in September 1880 (or had reasons for claiming so at the time), and that the records are complete, it seems likely that his first name was “Salomon”, possibly “Solomon” or a near equivalent.

The difference in age between S. Lipschütz in the Chess Monthly article and the Lipschutz who appears on the passenger lists is irritating, however.’

‘Ruben’ Fine is often seen in Spanish-language literature, and even in Fine’s own books. For instance, here is the front cover of the second edition (1962) of the Argentinian version of The Middle Game in Chess:

C.N. 3225 recalled that the observation ‘Chess is vanity’ is widely attributed to Alekhine and asked whether he ever used those words. We drew attention to the following passage on page 19 of the January 1929 BCM:

‘Alexander Alekhine, interviewed in Paris by the Eclaireur de Nice on 24 November, said with regard to his victory over Capablanca at Buenos Aires: “Psychology is the most important factor in chess. My success was due solely to my superiority in the sense of psychology. Capablanca played almost entirely by a marvellous gift of intuition, but he lacked the psychological sense.”

From the commencement of the game, the champion continued, a player must know his opponent. “Then the game becomes a question of nerves, personality and vanity. Vanity plays a great part in deciding the result of a game.”

We are indebted to the Central News for the above item of information.’

It has not yet proved possible to find the original text of the interview in the French source, but here we draw attention to what appeared in the quotes chapter of The Joys of Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1961), page 286:

‘“Chess is a matter of vanity.”

– Alexander Alekhine, Chess Review, 1934.’

However, this proves to be a non-source, for Reinfeld did not make it clear that the item in question was merely an article by Barnie F. Winkelman entitled ‘Vanity and Chess’ on pages 156-157 of the September 1934 Chess Review. The quotation introduced Winkelman’s article, as follows:

‘“Chess is a matter of vanity …”

Dr Alexander Alekhine

(From a reported interview.)’

|

That is all. The last two paragraphs of Winkelman’s article discussed the ‘reported’ Alekhine quote (whose authenticity has yet to be established):

|

|

Vidmar’s view, quoted in C.N. 3518, that in 1936 Kashdan was ‘the most talented player in America’ reminds us of a dramatic win by Kashdan the following year and a strange story recounted by I.A. Horowitz on page 8 of his book All About Chess (New York, 1971):

‘Carrie Marshall, widow of longtime United States chess champion, Frank Marshall, won a game for the USA in the International Team Tournament at Stockholm in 1937.

The match was USA v England, and the particular board was Kashdan, USA, against C.H.O. “Death” Alexander, the English champion.

Kashdan was hopelessly “busted”. Carrie, however, had suggested that a necklace which carried an image of Our Lady of Fatima could bring him luck if rubbed and petitioned. To oblige, Kashdan went through the motions, and Alexander instantly blundered away a piece and the game.

This win for Kashdan cost me a fat 50 dollars, a prize put up by Washington industrialist I.S. Turover for the American making the best score for the United States team.’

Below is a photograph of (left to right) Mrs Kashdan, I.I. Kashdan, F.J. Marshall, I.A. Horowitz and Mrs Marshall, with the Hamilton-Russell Cup:

It has not been possible to reconcile all the details of the above story with the game itself, which was annotated by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 567-569 of the November 1937 BCM and by the world champion, Max Euwe, on pages 21-23 of CHESS, 14 September 1937. Below is the complete score, with a digest of their notes to the concluding phase:

Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander – Isaac Irving Kashdan

Stockholm Olympiad, 12 August 1937

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 Bxc6+ bxc6 7 d4 Nd7 8 b3 Be7 9 Bb2 f6 10 Nh4 g6 11 Qe2 f5 12 dxe5 Bxh4 13 e6 Nf6 14 Qc4 c5 15 e5 Ng4 16 Qd5 Rb8 17 exd6 Bb7 18 d7+ Kf8 19 Qc4 Bf6 20 Bxf6 Nxf6 21 Qxc5+ Kg7 22 Nc3 Ng8 23 Rad1 h6 24 Rfe1 (Alexander did not comment on this, whereas Euwe called it ‘a good move but not the strongest’. He offered analysis to show that after 24 e7 Nxe7 25 Rfe1 there would be ‘a speedily decisive attack’. Annotating the game on pages 234-235 of the August 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung, Spielmann gave 24 Rfe1 a question mark and, like Euwe, indicated that 24 e7 would win.) 24...Ne7 25 Qe5+ Kh7 26 Na4 Rf8 27 f4 (Alexander: ‘To stop ...f4, but the rook gets in on the g-file. Both sides were now very short of time, each having 23 moves to make in about 15 minutes.’ 27...Rg8 28 Nc5 g5 29 Nxb7 Rxb7 30 c4 gxf4 31 Qxf4 Rg6 32 Qh4 Rb8 33 Re5 Qf8 34 Qf2 Rd8 35 Qc5 c6 36 Rf1 Qg7 37 Re2 Rg8

38 g3 (Alexander: ‘A blunder, but White has lost the grip of the position. 38 Rff2 might be good enough to draw, however (38...Qa1+ forces draw if Black wishes).’ Euwe: ‘This is the move which actually loses the game.’) 38...Rxg3+ 39 Kh1 (Alexander: ‘39 hxg3 Qxg3+ 40 Kh1 Qh3+ 41 Rh2 Qxf1+ 42 Qg1 Qxg1 mate.’) 39...Rg6 40 Qb6 (Neither Alexander nor Euwe commented on this move, but Euwe gave it a question mark.) 40...Rxe6 41 Rg1 Rxe2 (Alexander: ‘41...Qxg1+ 42 Qxg1 Rxg1+ 43 Kxg1 and wins.’ Euwe: ‘Kashdan has defended in an exceedingly difficult situation as well as he possibly could and now, as soon as he gains the advantage, thrusts it home inexorably.’) 42 Rxg7+ Rxg7 43 h4 (Alexander: ‘43 h3 would still draw as Black has nothing better than perpetual check.’) 43...Re1+ 44 Kh2 Re2+ 45 Kh3 (Alexander: ‘Seeing that 45...Ng6 could be met by 46 Qd4 winning, and completely overlooking the move played; but if 45 Kh1 Re4 46 Qf2 Rg8 and Black wins fairly easily.’ He gave 45 Kh3 two question marks, whereas Euwe, who presented the same line, appended only one.) 45...f4 46 White resigns. (Alexander: ‘A splendidly cool defence by Kashdan after his opening mistake; Black’s play when in time difficulties was extraordinarily accurate.’)

The game was also annotated by W.H. Cozens on pages 41-44 of his posthumous book The Lost Olympiad (St Leonards on Sea, 1985).

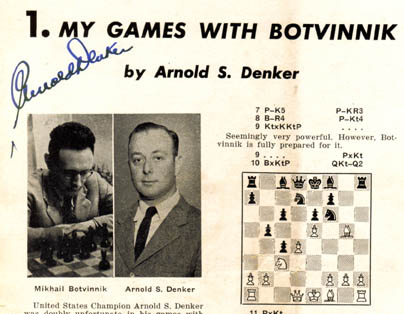

Another master mentioned in C.N. 3518 was Arnold Denker, whose death has recently been announced. Having often had occasion to be grateful for the generous encouragement he offered us, we have been spending some time browsing through his letters and e-mail messages. For now, just one brief quote is presented, from a letter to us dated 6 March 1988 in which he recalled Capablanca:

‘As a member of the Manhattan Chess Club I used to see him quite frequently. He was almost always cold and aloof, and would never deign to analyse with us young Turks. What a difference from Alekhine. He only would play ten-second pots with two of his old classmates at Columbia, giving each N odds for 25 cents a game. ... His widow, who later was married to Admiral Clark of the US Navy, comes to the club on [the anniversary of Capablanca’s death] every year and sits quietly for an hour.’

Below is an inscription by Denker in our copy of Chess Review, November 1945 (page 12):

No connection between Janowsky and the term ‘blind pigs’ has yet been found, but the following sourceless assertion is on page 65 of Chess Rules of Thumb by L. Alburt and A. Lawrence (New York, 2003):

‘Nimzowitsch called a pair of rooks on the opponent’s second rank “blind pigs” because they devour everything indiscriminately.’

An enquiry from Philipp Kaufmann (Zurich):

‘I am looking for a game commented upon by Samuel Beckett which began something like “1 e4 and now the difficulties begin for White”.’

The game in question was on pages 243-245 of Beckett’s 1938 novel Murphy, the exact wording of the note to White’s first move being: ‘The primary cause of all White’s subsequent difficulties’.

Murphy – Endon

1 e4 Nh6 2 Nh3 Rg8 3 Rg1 Nc6 4 Nc3 Ne5 5 Nd5 Rh8 6 Rh1 Nc6 7 Nc3 Ng8 8 Nb1 Nb8 9 Ng1 e6 10 g3 Ne7 11 Ne2 Ng6 12 g4 Be7 13 Ng3 d6 14 Be2 Qd7 15 d3 Kd8 16 Qd2 Qe8 17 Kd1 Nd7 18 Nc3 Rb8 19 Rb1 Nb6 20 Na4 Bd7 21 b3 Rg8 22 Rg1 Kc8 23 Bb2 Qf8 24 Kc1 Be8 25 Bc3 Nh8 26 b4 Bd8 27 Qh6 Na8 28 Qf6 Ng6 29 Be5 Be7 30 Nc5 Kd8 31 Nh1 Bd7 32 Kb2 Rh8 33 Kb3 Bc8 34 Ka4 Qe8+ 35 Ka5 Nb6 36 Bf4 Nd7 37 Qc3 Ra8 38 Na6 Bf8 39 Kb5 Ne7 40 Ka5 Nb8 41 Qc6 Ng8 42 Kb5 Ke7 43 Ka5 Qd8 44 White resigns.

A descriptive passage about the chess encounters between Murphy and Endon appeared on pages 187-188 of the book.

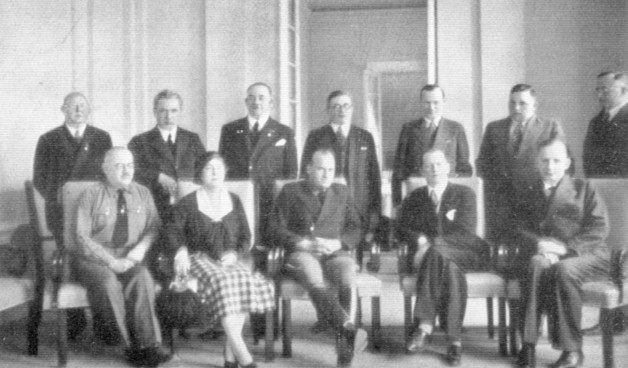

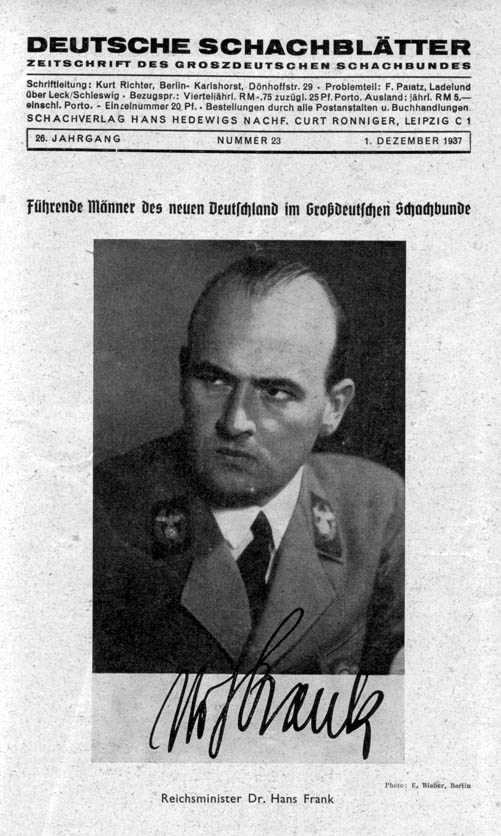

Some information about Hans Frank (1900-1946), the most prominent Nazi leader to be strongly interested in chess, is available in the books on Alekhine by P. Morán and L. Skinner/R. Verhoeven. Here, we give a series of photographs of him, i.e. a selection from those published in Deutsche Schachblätter (1936-1941).

The first one was taken in Frank’s ministerial office on 21 February 1936:

The caption identifies those sitting as (from left to right) ‘Zander, Frau Dr Aljechin, Reichsminister Dr Frank, Dr Aljechin, Richter’ and those standing as ‘Schlage, Post, Miehe, Helling, Sämisch, Oberstaatsanwalt Dr Bühler, Landgerichtsrat Dorn’.

In August 1937 Deutsche Schachblätter published the following picture of Post, Zander, Frank, Euwe, Miehe and Bogoljubow, under the heading ‘Weltmeister Dr Euwe in Berlin’:

In the 1 December 1937 issue, Frank was put on the front page:

Shortly before Christmas, 1940 Frank was presented with a chess table carved by Ukrainian mountain farmers, and the 1 February 1941 Deutsche Schachblätter deemed the event worth two-thirds of a page and the inevitable photograph (with Frank in the centre):

Finally, in November 1941 the magazine had the following picture, taken in Cracow, of Post, Frank and Alekhine seated, with Mross and Schmidt standing:

Deutsche Schachblätter ceased publication in March 1943. In Nuremberg on 16 October 1946 Hans Frank, having been convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, was hanged.

The following game, from a ten-game blindfold exhibition by Sämisch, was published on pages 87-88 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 March 1936, with annotations by White:

Friedrich Sämisch – Hans Frank

Berlin, 2 March 1936

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d3 Bc5 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be3 Bb6 7 Qd2 h6 8 Nd5 Be6 9 Nxf6+ Qxf6 10 Bxe6 Qxe6 11 Bxb6 axb6 12 a3 O-O 13 O-O f5 14 Qe2 f4 15 c3 g5 16 Ne1 g4 17 f3 h5 18 Kh1 Kf7 19 Nc2 Rg8 20 Rae1 Qf6 21 Nb4 Ne7 22 Nd5 Nxd5 23 exd5 Raf8 24 c4 Rg7 25 d4 Rg5 26 dxe5 Rxe5 27 Qd2 Rxe1 28 Rxe1 Re8 29 Rxe8 Kxe8 30 Qe2+ and Sämisch’s offer of a draw was accepted by the Reichsminister.

From the same year comes this inscription by Sämisch in our copy of Der Michel Angelo des Schachspiels by J. Hannak (Vienna, 1936):

The text appears to read, ‘Dem glücklichen Schachehepaar Hans und Annemarie [Lobbenberg?] mit herzlichsten Grüssen aus Karlsbad’, but the recipients’ surname is unclear.

A further item in our collection which was signed by F. Sämisch is a copy of Edward Lasker’s Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951). The other signatories were the ten participants in the Hastings, 1951-52 Premier Tournament, i.e. L. Schmid, D. Yanofsky, L. Barden, D. Hooper, H. Golombek, G. Abrahams, A.R.B. Thomas, S. Popel, S. Gligorić and J.H. Donner.

Over the years (see, for instance, pages 235-237 of Kings,

Commoners and Knaves and page 177 of A Chess Omnibus),

we have recorded early citations for many chessy words, as

follows:

|

Chessay: 1974 Chessdom: 1875 Chesser: 1875 Chessercize: 1991 Chessic: 1883 Chessical: 1904 Chessically: 1874 Chessie: 1909 Chessikin: 1878 Chessing: 1953 Chessist: 1881 |

Chessite: 1834 Chesslet: 1928Chessmanity: 1901 Chessner: 1624 Chessnicdote: 1978 Chessomania: 1977 Chessophobe: 1911 Chessophrenetic: 1977 Chesstapo: 1944 Chessy: 1883 Chess-ty: 1929. |

In many cases, if not all, earlier instances may come to light, but we would particularly welcome old citations for a further word, Chessiana. At present nothing better is on hand than the following, on page 162 of the June 1950 Chess Review:

‘From The Road to Music by Nicolas Slonimsky (Dodd, Mead and Company) we find a curious bit of chessiana.’

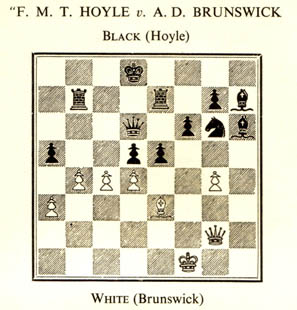

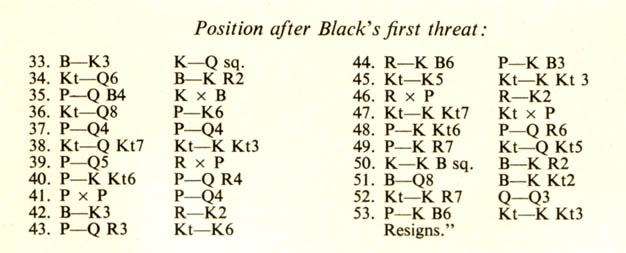

A tough old puzzle from the days of the descriptive notation:

‘Below is the “score” of a game found in A.D. Brunswick’s rooms after his death under mysterious circumstances. It was in Brunswick’s handwriting. At first it aroused no suspicions, but Inspector Snooper, a keen chessplayer, saw at once that it was some sort of cryptogram.’

|

|

‘What was Brunswick’s message?’

Needed though they may be, clues will not be provided, at least for now, to the two-pipe problem in C.N. 3530. Instead, we offer some jottings about Sherlock Holmes and chess.

His famous remark ‘Amberley excelled at chess – one mark, Watson, of a scheming mind’ appeared in ‘The Adventure of the Retired Colourman’ in The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes (London, 1927). That source is now well known to chess enthusiasts, but was not always so. On page 34 of his anthology Chess Pieces (London, 1949), Norman Knight related that, uncertain of which Holmes story had included the quotation, he had written a letter of enquiry to The Observer; no fewer than 82 replies were received (‘which shows that the field of Holmesian scholarship is better tilled than he [Knight] had imagined’).

The other prominent connection between the detective and chess is Raymond Smullyan’s book The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes (London, 1980).

Imitations and parodies of the Holmes stories are not infrequent, and three good ones with a chess connection come to mind. The most recent is ‘The Case of the Mental Detective’ by William R. Hartston, on pages 25-30 of his book Soft Pawn (London, 1980).

Chess Review, February 1962 (pages 45-47) published ‘The Moriarty Gambit’ by Fritz Leiber, which included the following game:

Sherlock Holmes – James Moriarty

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 cxd4 5 Qxd4 Nc6 6 Qa4 exd5 7 Nf3 d4 8 Nb5 Bd7 9 Nbxd4 Bb4+ 10 Kd1 Nxd4 11 Qxb4 Nxf3 12 exf3 Ba4+ 13 Ke2 Qd1+ 14 Ke3 O-O-O 15 Bd2 Qxa1 16 Ba6 Re8+ 17 Kf4 Re4+ 18 fxe4 g5+ 19 Kg3 Qxh1 20 Qxb7+ Kd8 21 Qc8+ Ke7 22 Bb4+ Kf6 23 Qf5+ Kg7 24 Qxg5 mate.

Leiber’s story was reproduced on pages 205-216 of Chess in Literature by M. Truzzi (New York, 1975).

Finally, pages 289-293 of the October 1918 BCM had ‘A Game at Chess’ by ‘E.A.G.’ (who may have been Edwin A. Greig). This yarn involved Mr Shercock Bones, Whatson and Professor Moratorium. The sleuth declared to his friend, ‘I shall play Moratorium tonight – I shall not lose the game – and I shall make more than 16 sacrifices’, and he fulfilled these undertakings as follows:

Professor Moratorium – Shercock Bones

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d6 3 d4 Ne7 4 Bd2 Bd7 5 Bb4 Nbc6 6 Ba3 Na5 7 f5 Nec6 8 c3 Qf6 9 Nd2 Be7 10 Qg4 Qh6 11 Ndf3 Qh3 12 gxh3 h5 13 Qxg7 O-O-O 14 Qxf7 Nb3 15 axb3 Rh6 16 Bg2 Be8 17 Qg7 Bh4+ 18 Kf1 Rh8 19 d5 Kb8 20 Re1 Ka8 21 Qxh8 Nb4 22 cxb4 Bb5+ 23 Re2 Rxh8 24 f6 Rh6 25 f7 Rh8 26 f8(Q)+ Rxf8 Drawn.

An appropriate conclusion to this item is the front cover of a French edition of an Arthur Conan Doyle collection, published in 1948, Un échec de Sherlock Holmes:

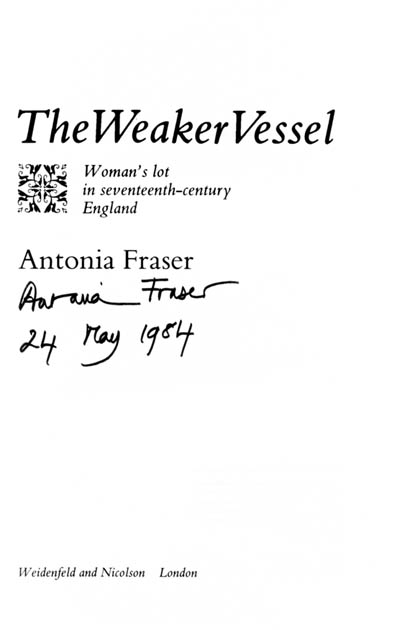

Professor Jack MacIntosh of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Calgary, Canada has drawn our attention to the following passage on page 412 of Antonia Fraser’s book The Weaker Vessel (London and New York, 1984):

‘Only one man present recognized them and that was Henry Brounckner, known as the best chessplayer in England, who combined this hobby with that of keeping a house of pleasure near London, stocked with “several working-girls”.’

Our correspondent asks what information is available about his connection with chess.

No such person is mentioned in H.J.R. Murray’s A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913), which makes it rather surprising to find a reference to him in Murray’s A Short History of Chess (Oxford, 1963), which was published posthumously but written as early as 1917. From page 63:

‘The names of three players of greater skill [than monarchs of the time] have survived: Alexander Blagrave, “the excellent chessplayer in England” in the reign of Elizabeth I, Col. Bishop, “accounted the best in England” in the reign of James I, and Mr Brounker, Gentleman of the Chamber to the Duke of York, in Charles II’s reign.’

Unable to find anything else of relevance in chess literature, we consulted a leading authority on the period, John Morrill, who is Professor of British and Irish History at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He has identified the man in question as neither Brounckner nor Brounker, but Henry Brouncker (c1627-1688), who was the third Viscount Brouncker of Lyons.

Professor Morrill has also kindly provided us with a copy of G.S. McIntyre’s article on Henry Brouncker (and his elder brother, William) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). This records that Henry Brouncker was ‘cofferer to Charles II and gentleman of the bedchamber to the Duke of York’ and the Member of Parliament for Romney from 1665 until his expulsion in 1668. The article also states:

‘He was not well liked, although admired for his skill with chess: Edward, Earl of Clarendon, described him as “a man throughout his whole life notorious for nothing but the highest degree of impudence, stooping to the most infamous offices, and playing chess very well, which preferred him more than the most virtuous qualities could have done” (Clarendon, 2.515).’

It has not yet been possible for us to establish what grounds may exist for Antonia Fraser’s remark that he was ‘known as the best chessplayer in England’.

At the website http://www alberteinstein info/database.html readers will find interesting documentary information by making a search for ‘Lasker’.

We are aware of one chess game attributed to Albert Einstein, a win against Oppenheimer (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 b5 5 Bb3 Nf6 6 O-O Nxe4 7 Re1 d5 8 a4 b4 9 d3 Nc5 10 Nxe5 Ne7 11 Qf3 f6 12 Qh5+ g6 13 Nxg6 hxg6 14 Qxh8 Nxb3 15 cxb3 Qd6 16 Bh6 Kd7 17 Bxf8 Bb7 18 Qg7 Re8 19 Nd2 c5 20 Rad1 a5 21 Nc4 dxc4 22 dxc4 Qxd1 23 Rxd1+ Kc8 24 Bxe7 Resigns). When this game was first published seems impossible to say for certain, but it gained wide currency by appearing in a brief entry on Einstein in the Dictionnaire des échecs by François Le Lionnais and Ernst Maget (Paris, 1967). The source specified was Freude am Schach by Gerhard Henschel (Gütersloh, 1959), although the French reference book used the conditional tense, to convey uncertainty about the game’s authenticity (‘la partie suivante qui aurait été gagnée par Einstein contre le grand physicien Robert Oppenheimer’).

Neither of the above-mentioned books offered a date or a venue, and the note of caution added by the Dictionnaire was subsequently neglected. Contradictory specifics appeared in other books; for example, page 415 of Şah Cartea de Aur by Constantin Ştefaniu (Bucharest, 1982) described it as a ‘game of historic value’ played in the United States in 1940. Elsewhere the date has been given as 1933, and the venue as Princeton.

The Dictionnaire also had an entry for Stalin, with the following illustrative win over ‘le chef de la Guépéou’: 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nbd7 6 Be2 a6 7 O-O e6 8 f4 b5 9 a3 Bb7 10 Bf3 Qb6 11 Be3 Qc7 12 Qe2 Be7 13 g4 Nc5 14 Qg2 O-O 15 Rad1 Rfe8 16 g5 Nfd7 17 Rd2 e5 18 Nf5 Ne6 19 Nxe7+ Rxe7 20 f5 Nd4 21 f6 Ree8 22 Bh5 g6 23 Bxg6 hxg6 24 Qh3 Ne6 25 Qh6 Qd8 26 Rf3 Nxf6 27 gxf6 Rc8 28 Rdf2 Qxf6 29 Rxf6 Rc7 30 Nd5 Bxd5 31 exd5 Nf8 32 Bg5 Nh7 33 Rxd6 e4 34 Be3 Rce7 35 Bd4 f6 36 Bxf6 Nxf6 37 Rdxf6 Resigns. Again the source mentioned was Henschel’s book Freude am Schach, and the French authors made the same use of the conditional tense to indicate their doubts: ‘la partie suivante qui aurait été gagnée par Staline’.

Le Lionnais and Maget put the heading ‘Staline-Yejov, Moscou?, 1926?’. Although the year 1926 has now stuck to the game, it seems to be based on a misreading of Henschel’s book (pages 86-90). True enough, ‘1926’ is the only date to appear on those pages, but its context had nothing to do with when the game allegedly took place. Indeed, Henschel’s own claim was that it was much older, for the first sentence of his item affirmed that Stalin had played it ‘kurz nach seiner Flucht aus der sibirischen Verbannung’ (page 86), whereas two pages later Henschel’s (1959) book stated, ‘Wenn wir bedenken, dass die Partie schon vor rund 50 Jahren gespielt wurde ...’

As regards the genesis of the game, he said (page 86) that it had been written down from memory by an unnamed associate of Lenin:

‘Die hier aufgezeichnete Partie ist uns nur durch einen Zufall bekannt geworden. Ein alter Mitarbeiter Lenins, dessen Name leider nicht bekannt ist, hat sie aus der Erinnerung aufgeschrieben.’

Was Henschel’s dire book, which is replete with errors of all kinds (Fischer is misspelt ‘Fisher’ throughout), really the first appearance in print of the Einstein and Stalin games? What credibility does either have?

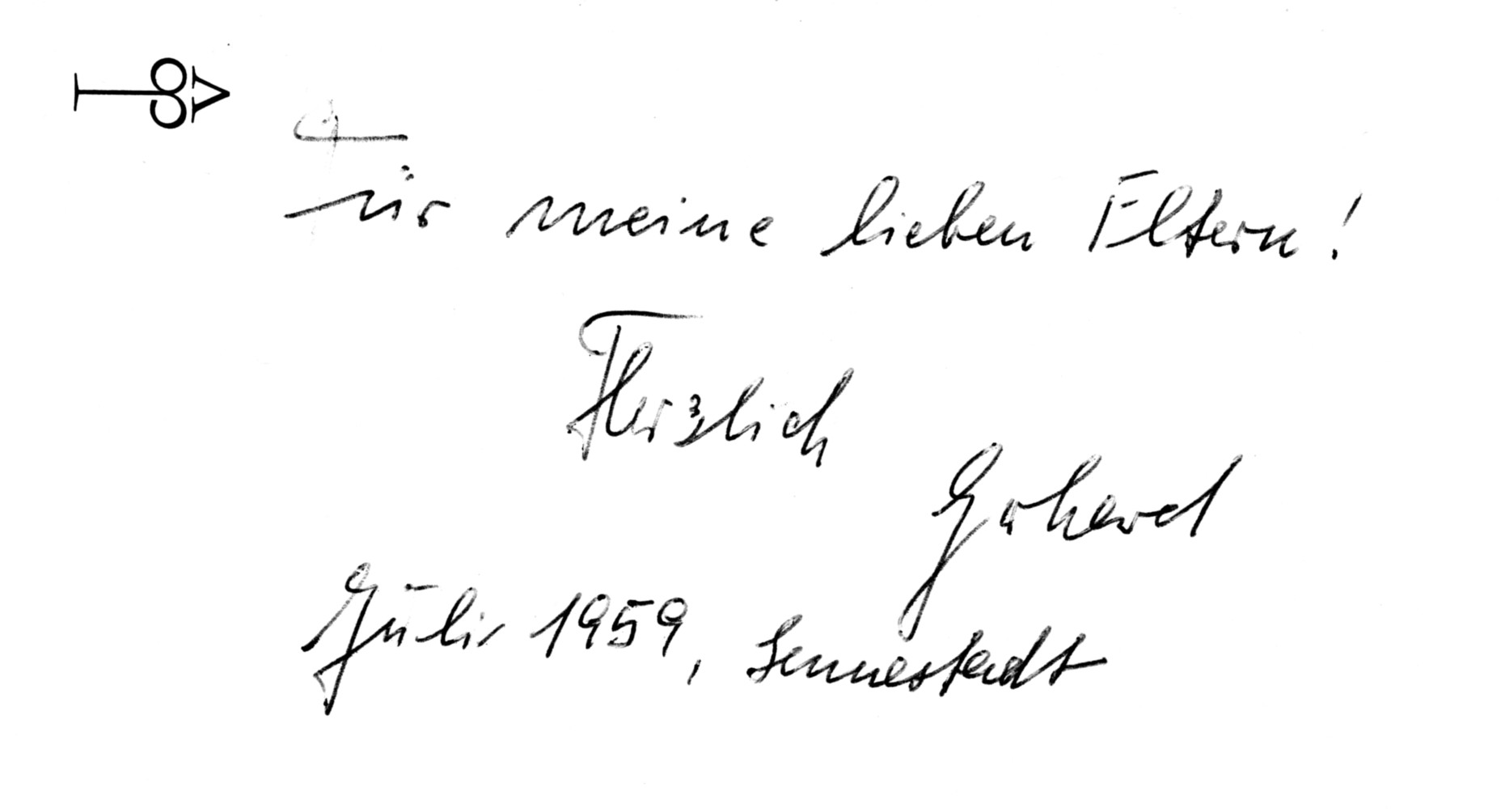

Finally for now, we mention that our copy of Freude am Schach contains an inscription by Henschel to his parents:

For readers who tire of seeing the same old group photographs (e.g. Nottingham, 1936) reproduced in chess literature we shall present from time to time some rarer shots. The one below is from Prague, 1942:

Standing: K. Junge, J. Podgorný, J. Foltys, F. Sämisch, J. Rejfíř, C. Kende (organizer), F. Prokop. Seated: A. Alekhine, O. Důras.

|

Neil Brennen (Malvern, PA, USA) writes: ‘From time to time you have included predictions about famous players. While I was at the Cleveland Public Library I copied a scrapbook of Harlow Daly’s. Among the clippings were two articles about the 1904 Cambridge Springs tournament written by John F. Barry for the Boston Herald. Barry made a number of interesting comments on Marshall and his play:

|

|

Correct answers have been submitted by Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) and John Saunders (London). For those not there yet, a clue is offered: it is necessary to study the letters in the caption, then the squares occupied by the pieces and, finally, the moves.

‘The competitors in the Rookwood Chess Congress are organized in two sections. In each section each competitor plays one game against each of the other competitors in that section.

This meant, last year, that the secretary had to arrange 165 games. This year there is one more competitor in each section.

How many games must the secretary arrange?’

A US correspondent is seeking a copy of page 173 of Magyar Sakkélet, 1960. Can a reader kindly send it to us?

A particularly dispiriting way to start a tournament:

C. Sullivan – David Vincent Hooper

Bristol, 1947

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 b3 d5 3 Bb2 dxe4 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 Qe2 Bb4 6 Nxe4 Nxe4 7 c3 Nxc3 8 dxc3 Be7 9 Rd1 Nd7 10 Nf3 Bf6 11 Qe3 Qe7 12 a4 Qc5 13 Nd4 Qe5 14 Qxe5 Bxe5 15 Ba3 a6 16 g3 Bd6 17 Bc1 Ke7 18 Bg2 Rb8 19 O-O c5 20 Nf3 Ne5 21 Ng5 f6 22 f4 Ng6 23 Nf7 Kxf7 24 Rxd6 a5 25 Rfd1 Re8 26 Rb6 Nf8 27 Bc6 Re7 28 Ba3 Rc7 29 Bb5 Bd7 30 Bc4 Ke7 31 f5 exf5 32 Re1+ Kd8 33 Bc1 Ng6 34 Rd1 Ke7

35 Re1+ Kd8 36 Rd1 Ke7 37 Re1+ (‘At this point White offered a draw, which Black declined – to his chagrin two moves later.’)

37...Kf8 38 Rxf6+ gxf6 39 Bh6 mate.

Source: page 3 of West of England Chess Championship 1947 by P.D. Bolland (Bristol, 1947).

R.D. Picken (Greasby, England) raises a series of questions about a particularly obscure phase of chess history. We throw them open to readers:

‘In his book Bogoljubow – The Fate of a Chess Player (Sofia, 2004) Sergei Soloviov provides some interesting biographical material. Pages 18-22 cover the period of the First World War, and Soloviov states that “11 Russian players” from the interrupted Mannheim tournament were interned by Germany after the declaration of war against Russia. He names them as Bogoljubow, Flamberg, Selesniev, Alekhine, I. Rabinovich, Bohatirchuk, Maliutin, Romanovsky, Weinstein, Saburov and Koppelman. Who was Koppelman? Soloviov’s book adds that other players at Mannheim representing countries now at war with Germany were also interned. Who were they? Most players at Mannheim were German/Austrian nationals. Hooper and Whyld indicate in the Janowsky entry in The Oxford Companion to Chess that Janowsky was interned (where?) but released to Switzerland after a short internment. (How short, and why was he released when the Russians were not?)

I do not know whether other “enemy” nationals who had the misfortune to be in Germany when war broke out were also interned, but the internment of the chessplayers was carried out very quickly. One would have thought it easier to pack them all off to Switzerland or home.

Gaige provides details of eight tournaments played by the Russian internees, the first in Baden-Baden and all the others in Triberg. Participation by the internees varied, but the tournaments were mostly won by Bogoljubow. I have prepared the following table of their participation:

TOURNAMENTS

1st

2nd

3rd

4th

5th

6th

7th

8th

Alekhine

Bogoljubow

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Flamberg

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Rabinovich

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Bohatirchuk

Selesniev

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Maliutin

Y

Y

Y

Y

Romanovsky

Y

Y

Y

Weinstein

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Saburov

Koppelman

Fahrni

Y

Y = player participated in tournament.

It is not clear why Fahrni suddenly competed in the seventh tournament. Was he interned after Mannheim, 1914 and, if so, why? And, if interned, why did he play in only one event?

Moreover, eight tournaments in four years seems a very leisurely regime. What else did the players have to do?

According to Soloviov’s book on Bogoljubow (page 21), Alekhine, Bohatirchuk, Koppelman and Saburov all escaped to Switzerland quite early on in the war. How? Hooper and Whyld ascribe Alekhine’s escape to family influence. Is that true, and what about the others? And if the situation was such that escape was possible, why did the others not attempt it?

Hooper and Whyld also state, in the entry on Flamberg, that he (a Polish player) was allowed to return to Warsaw in 1916. This may be because in 1916 Germany had control of the Polish part of the Russian Empire, and no need was evident to continue his internment. Even so, it would have been expected that each of the players interned for the duration of the war would participate in every event. Yet Maliutin and Weinstein did not.

The nature of the internment seems to have been fairly liberal, and it is stated that efforts were made by supporters in St Petersburg to secure their release. Soloviov says that money was collected to this end in 1914. This puzzles me. With the war in progress, how did the supporters hope to enter into “negotiations” with the German authorities?’

We are still unable to say how Kurt Lüdecke came into contact with F.J. Marshall at Mannheim in 1914, and again in the United States in 1937, or to trace any of his games. Nor have we found clues about Lüdecke in the book he edited and sent to Hitler (see C.N. 3456). It is, indeed, a remarkably detailed gazetteer and travel guide (an 848-page hardback), the Foreword to which was signed ‘K.G.W.L., New York City, 15 May 1930’.

Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) reports that he has written several Sherlock Holmes stories with a chess theme. Two of them were published in Chess Life, as follows:

- ‘The Royal Game’, August 1982, pages 26-27, with the solutions on page 10 of the October 1982 issue.

- ‘The Case of the Diogenes Club’, July 1993, page 78.

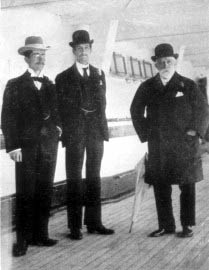

Who is the chess figure in this trio? We are feeling rather confident that no reader will be able to identify him.

C.N.s 2510 and 2594 (see pages 261-262 of A Chess Omnibus) provided some notes on members of the British royal family from the nineteenth century onwards, including Queen Victoria and George V. Our intention was to write a companion piece on earlier periods, but the ground seems to have been covered so well by H.J.R. Murray’s A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913) that any such item would in large part have to repeat what he wrote about, for instance, King John, Edward I, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I. We therefore approach the subject from another angle: what research discoveries, if any, have been made about British royalty and chess since Murray’s heyday?

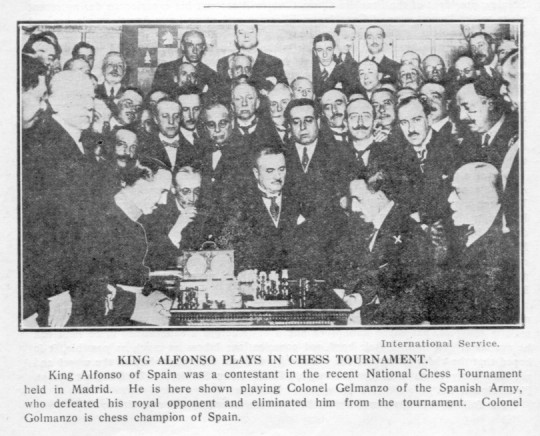

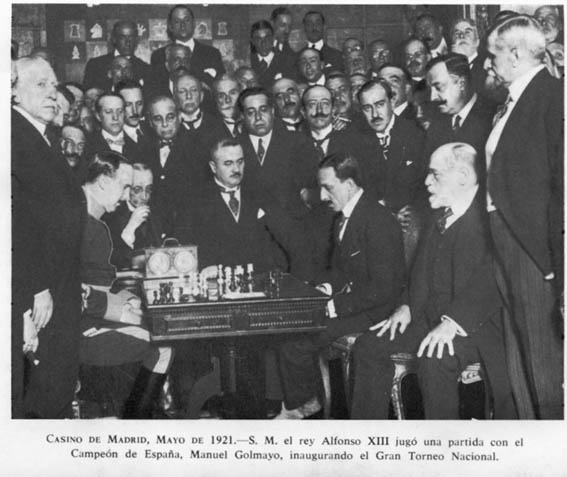

Has a monarch ever participated in a chess tournament? Yes, according to page 109 of the May-June 1921 American Chess Bulletin, which had the following photograph:

The explanatory note reads:

‘King Alfonso of Spain was a contestant in the recent National Chess Tournament held in Madrid. He is here shown playing Colonel Gelmanzo of the Spanish Army, who defeated his royal opponent and eliminated him from the tournament. Colonel Golmanzo is chess champion of Spain.’

It was not ‘Gelmanzo’ or ‘Golmanzo’ but (Manuel) Golmayo. The same shot appeared as a supplement to La Stratégie, July 1921 with the heading ‘Inauguration of the Spanish national tournament, Casino de Madrid, 15 May’ and the caption ‘His Majesty King Alfonso XIII playing the first game with the Spanish champion, Commander Manuel Golmayo’:

So did Alfonso XIII participate in the event? Spain had, we believe, no chess magazine at the time, but the following report was published on pages 172-173 of La Stratégie, July 1921:

‘Un grand Tournoi national organisé sous les auspices des Sociétés Casino de Madrid, Gran Peña, Centro del Ejército y de la Armada, Círculo de Bellas Artes et Liceo de América s’est joué du 15 mai au 5 juin dernier au Casino de Madrid. Vingt-cinq des meilleurs joueurs d’Espagne y prirent part. L’inauguration officielle en fut faite par S.M. le roi d’Espagne, Alphonse XIII, qui voulut bien honorer les Echecs de sa participation effective, en soutenant le combat dans le premier tour éliminatoire contre le commandant Manuel Golmayo, le champion espagnol.’

La Stratégie recorded that Manuel Golmayo won the first phase with 16½ points. The rankings were given for the next 18 players, with no mention of the King. The top four players then participated in a double-round tournament, which was won by Golmayo.

On pages 11-12 of Campeones y Campeonatos de España de Ajedrez (Madrid, 1974) Pablo Morán reported that in June 1968 he had a conversation with Golmayo (who, then aged 85, experienced difficulty in recalling dates and other facts):

‘Y a continuación me contaba una y otra vez aquella partida que jugó con el Rey Alfonso XIII.

“El día antes de comenzar el Campeonato de España de 1931 ...”

“No, don Manuel, de 1921.”

“Bueno, pues sí, el día antes me encontré con el Rey en Palacio y me dijo: ‘Manolo, mañana voy a inaugurar ese Campeonato y a jugar una partida contigo.’ ‘Pero ... Majestad.’ ‘¡Nada, nada, Manolo, mañana a jugar!’ Y el Rey vino a jugar conmigo; de mis piezas quitó un caballo, y mientras todo el mundo se agolpaba en nuestra mesa el Rey me decía: ‘Manolo, ¿qué pieza muevo?’ Y yo le decía ésta o aquella jugada, y me costó mucho trabajo perder.”’

Morán found that news publications of the time, such as ABC,

stated that the King had indeed won against Golmayo, the game

being played before the Championship began. There were no

reports in ABC to support the above statements of

Golmayo that he had given knight odds and advised the King which

moves to play.

Below are two photographs of Golmayo:

Alfonso XIII was King of Spain from the year of his birth, 1886, until the proclamation of a republic in 1931. He then left Spain and settled in Rome, where he died in 1941.

We have yet to find anything more about Henry Brouncker’s connection with chess, but it may be noted that a painting of him exists in the National Portrait Gallery, London and can be viewed online (http://www.npg.org.uk).

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that a slightly different shot of Alfonso XIII and Manuel Golmayo appeared between pages 8 and 9 of Golmayo’s book Temas clásicos de ajedrez (Madrid, 1966):

Mr Sánchez adds that according to page 5 of the book the winner of the 1921 National Tournament was presented with an appropriately named trophy, the ‘Copa de S. M. el Rey’.

The enigma was published on pages 28-29 of Caliban’s Problem Book by Hubert Phillips (‘Caliban’), S.T. Shovelton and G. Struan Marshall (London, 1933). Below is a summary of the solution given in the book:

‘The data are these: (1) there are 20 squares with pieces on them; (2) every move in the “game” (except captures) is a move to one of these squares; (3) there are 20 letters in the caption to the “problem”. These 20 letters are the clues that enable the squares to be identified.

If the caption is written down, and under its several letters the chess notation, as seen by White (“it was in Brunswick’s handwriting”), of the squares on which pieces are shown in the diagram, the following key will result:

F Q8; M QKt7; T K7; H KKt7, O KR7, [etc.].

Now write down the notation of the squares to which pieces are moved in the “game”, taking care to change the notation, in the case of moves by Black, to that from White’s point of view, and apply the key, when the following will result:

K3 I; Q8 F; Q6 Y; KR7 O; QB4 U; [etc.],

i.e. “If you find me dead it will be the work of Hoyle”.’

The solution is 191 games, as sent in by Alasdair Alexander (Wellington, New Zealand), Louis Blair (Carlinville, IL, USA), Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) and Tom Rogers (Westfield, NJ, USA).

This too is a puzzle by Hubert Phillips, from page 198 of Hubert

Phillips’s Heptameron (London, 1945) and page 66 of

his Problem Omnibus Volume 1 (London, 1960). The answer

can be found by considering the relevant possibilities on the

basis of a scale. For example, if there were two players in a

section, one game would be played; three players, three games;

four players, six games; five players, ten games, etc.

(continuing until 19 players, 171 games). Such a scale shows

that the number of games in last year’s tournament (165) can be

made up only of 45 and 120, which, on the scale, correspond to

ten players and 16 players respectively. This year the sections

therefore had 11 players and 17 players, and the relevant

figures on the scale are 55 games and 136 games respectively. 55

+136 =191.

An extensive note on Hubert Phillips, who co-wrote a chess book

with Golombek, is in preparation, and there will also be some

more of his puzzles with a chess theme. He was a phenomenon.

Several rather hard quiz questions have been given here of late, but readers should have no difficulty with the following one:

a) Which chess book published by McFarland in 2004 has been praised to the skies by critics and has been described by Nigel Short (in the Sunday Telegraph of 12 December 2004) as his ‘favourite tome of the year’?

b) Which chess book published by McFarland in 2004 has the Chess Café/USCF Sales refused to stock or review?

Chess Notes Archives:

| First column | << previous | Archives [4] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright 2005 Edward Winter. All rights reserved.