Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [107] | next >> | Current column |

8080. Steiner and Flohr

Bruce Monson (Colorado Springs, CO, USA) wonders what can be established regarding the photograph below, from Herman Steiner’s archives, beyond identification of Steiner on the left of the foursome and Salo Flohr on the right.

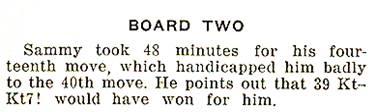

8081. Berne, 1932 (C.N. 8065)

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) has commented that the typewritten list does not fully correspond to the signatures. Rudy Bloemhard (Apeldoorn, the Netherlands), the owner of the card, has now posted it on his website, with all the signatures identified individually.

8082. St Louis, 1941

From Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s archives John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) has forwarded this photograph taken at the US Open tournament in St Louis, 1941:

Mr Donaldson has identified a number of the figures, and with readers’ assistance we hope to build up a full key.

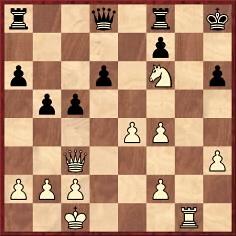

8083. What should be the result?

8084. Steiner and Flohr (C.N. 8080)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada), Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) and Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) suggest that the players between Steiner and Flohr are Vasja Pirc and Karl Gilg, and that the photograph was taken during the tournament in Štubňanské Teplice, 1930.

For photographs of Pirc and Gilg, see C.N.s 4052, 4532

and 6131.

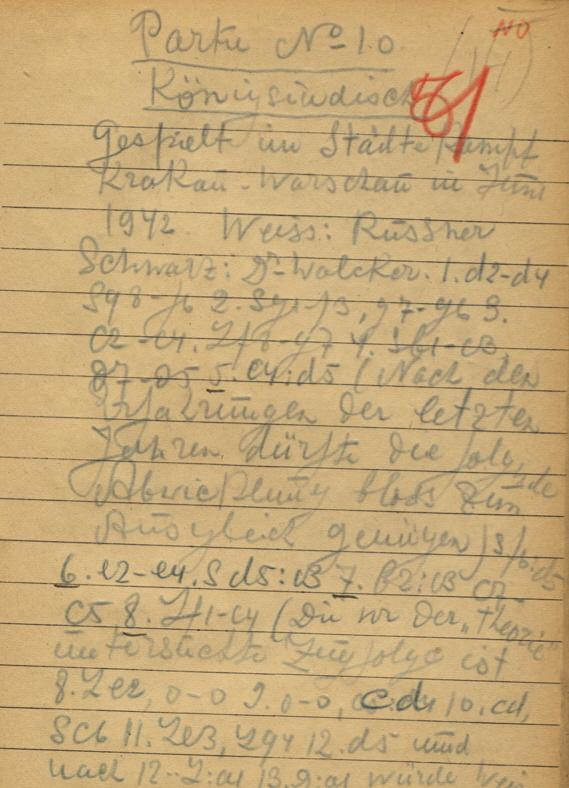

8085. Russner v Walcker (C.N.s 7926 & 7930)

Denis Teyssou (Paris) provides an extract from Alekhine’s comments on the 1942 brilliancy between Russner and Walcker:

The source is Alekhine’s notebooks (C.N. 8060).

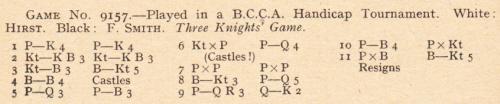

8086. Hirst v Smith

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Bc4 O-O 5 d3 c6 6 Nxe5 d5 7 exd5 cxd5 8 Bb3 d4 9 a3 Qe7 10 f4 dxc3 11 axb4

11...Bg4 12 White resigns.

‘Hirst v Smith’ and ‘England, 1943’ is the only information provided regarding this miniature on page 30 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1955). We note from page 162 of the July 1943 BCM that it was a correspondence game (BCCA being the British Correspondence Chess Association):

8087. Cotlar (C.N.s 3581, 3584, 3613, 3665 & 6085)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) quotes from the obituary of Ovsey Cotlar on page 235 of the September-October 1952 issue of Caissa (Buenos Aires), which states that he had recently died in that city at the age of 73:

‘Falleció recientemente en esta capital, el maestro ruso Ovsey Cotlar, ampliamente conocido por sus investigaciones sobre la defensa Lasker del gambito de dama y del sistema Rubinstein del Ruy López, trabajo éste que engalanó en su oportunidad las páginas de Caissa. Pese a su avanzada edad de 73 años, era dable esperar aún otros aportes a la teoría, por lo cual es más sensible su deceso.’

8088. Translating Fischer (C.N. 7907)

We have been looking further at the two editions of Parviz M. Abolgassemi’s French translation of My 60 Memorable Games (i.e. with and without the revisions of Chantal Chaudé de Silans).

Although Mr Abolgassemi could translate statements such as ‘White wins a pawn’ without incident, Fischer’s more colourful phrases were beyond him. One example, from game 45 (after 27 Be5):

‘Bisguier slumped and his chest collapsed ...’

‘Besguier se penche tout à coup ...’

The revised edition made more of an effort:

‘Bisguier s’affaissa et courba les épaules ...’

Various names are misspelled in both French editions (e.g. Bryn, Spielman, Kmotch and Anderson), and a proper French translation of Fischer’s book is more than 40 years overdue.

8089. FIDE archives

In a letter dated 9 July 1945 to the Schweizerische Schachzeitung (November 1945 issue, page 169) the FIDE President, Alexander Rueb, reported that a fire had destroyed the Federation’s archives and much else:

‘Nous avons survécu, ma femme, mes trois fils et moi. Mais un désastre, le 3 mars 1945! Chassés de la van Speykstraat, la Fédération néerlandaise et moi avions transporté nos biens ailleurs en janvier 1944, mais 15 mois plus tard le quartier fut la proie des flammes. Tout l’inventaire de la Fédération, sa précieuese bibliothèque, ses collections et ses souvenirs ont péri! En outre, les archives de la FIDE, mon étude d’avocat ... l’oeuvre de ma vie! Heureusement, ma collection privée d’études est sauvée. Je n’ai pas perdu courage et reprendrai l’oeuvre de la FIDE aussi tôt que possible. Mon adresse: 43 Riouwstraat, La Haye.’

8090. Overstepping the time-limit

Timothy J. Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) asks which leading

masters have sustained the fewest losses on time (in

tournament and match games). Documentation from readers

will be much appreciated.

To start with Capablanca, the paragraph below comes from page 55 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

‘Capablanca, who has been credited with the quickest sight of any master who ever lived (“His speed in play”, says Fine, “was incredible in the early years. What others could not discover in a month’s study he saw at a glance.”), once lost a tournament game on time limit.’

(The Fine quote comes from page 111 of his book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951); Fine wrote ‘earlier’, not ‘early’.)

Chernev’s paragraph concerned Riumin v Capablanca, Moscow, 1935. A second game which the Cuban lost by exceeding the time-limit was in Arnhem on his 50th birthday, against Alekhine in the AVRO, 1938 tournament.

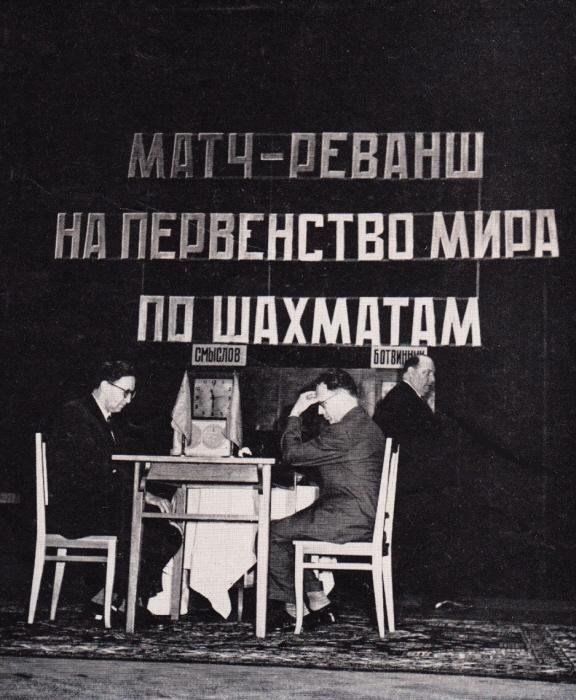

A passage by Harry Golombek about Botvinnik also comes to mind, from page 143 of the June 1958 BCM. It described the conclusion of game 15 in that year’s Smyslov v Botvinnik world championship match:

‘... absorbed in calculations as to how to obtain the win, he [Botvinnik] quite forgot about his clock and forfeited the game on time, a result that was received in stunned silence by the audience. The saddest part of it all was that even when he exceeded the time-limit he had a won ending, since he possessed two very powerful bishops and could create a remote passed pawn. He told me immediately afterwards that this was the first occasion in his life on which he had lost a game on time.’

For the loser’s own comments, see, for instance, page 244 of Botvinnik-Smyslov Three World Chess Championship Matches: 1954, 1957, 1958 by M. Botvinnik (Alkmaar, 2009):

‘As I sat there, absorbed in these thoughts, great was my astonishment when the chief arbiter Ståhlberg came over to our table and announced that Black had lost on time. Having two-three minutes for a couple of moves, I had simply forgotten all about the clock and had exceeded the time limit ...’

V. Smyslov, M. Botvinnik and G. Ståhlberg (Chess Review, July 1958, page 203)

Regarding Carl Schlechter, see page 241 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

8091. Botvinnik and Smyslov

Below is an article by G.H. Diggle from page 69 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It was originally published in the June 1981 Newsflash.

‘The nine world championship matches (Russians only) which spanned the ’50s and ’60s did not greatly excite the outside world, which accepted Soviet Chess as unapproachable in stature by the rest of mankind, and regarded all Russian grandmasters as “Dinosaurs” with unpronounceable names. Moreover, as international rivalry and politics were “out”, the Press had nothing to report but chess, which was, of course, fatal. Worse still, the combatants were good friends and good sportsmen, and so of “unfortunate incidents” and “embarrassing moments” there was complete dearth in the land. It is true that, for the first time in chess history, the matches were great public spectacles in themselves, staged in magnificent concert halls with the contestants spotlighted on platforms before audiences running into thousands. But some press reports at the time were so “overwhelming” that they ended up as masterpieces of anti-climax – the Badmaster misquotes from his “Munchausen” memory: “Hours before play commenced, the great opera hall was filled with great-grandmasters, grandmasters and international masters; outside in the snow, hundreds of masters and candidate masters, unable to obtain admission, listened to a running commentary broadcast by Grandmaster Ponderovsky. After ten moves a draw was agreed upon. ‘A true grandmaster epic’, as Ponderovsky sardonically remarked.”

But any person so unreasonable as to prefer fact to fantasy should refer to the BCM for 1954, 1957 and 1958, where full accounts of the three great Botvinnik-Smyslov matches are given by “H.G.”, who acted as judge throughout all three. Botvinnik then aged 42 (Smyslov was ten years younger) just retained his title in the first match, a magnificent struggle full of collapses and comebacks ending 12 games all, lost it in the second (9½-12½) and regained it in the third (12½-10½). The fighting quality of both masters can be gauged from the fact that of the whole aggregate of 69 games, only four “grandmaster draws” can be traced, and three of these were at the end of the second match, when Botvinnik clearly had no chance of catching up. The audience (apart from the “grandmaster element”) are described by H.G. as “keener and more knowledgeable than spectators in other countries” and varied from “much beribboned soldiers of high military rank” to the “average artisan”. They were an impartial crowd, though in the 14th game of the third match, when Botvinnik by winning after 68 moves established a 9-5 lead and almost ensured regaining the title, the crowd invaded the playing arena in their delight that “the old man had done it again”. Yet in the very next game Botvinnik, with a winning ending, completely forgot the clock and (for the only time in his whole career) lost on time-limit, thereby (as it turned out) postponing his final victory for another fortnight.

No fewer than 13 of the games lasted exactly 41 moves, owing mainly to resignations without resuming play, after the opening of sealed envelopes the “shrewd contents” of which doubtless resembled those which “stole the colour from Bassanio’s cheek”.’

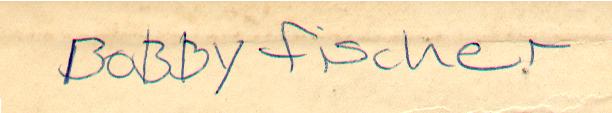

8092. Fischer inscription

From one of our copies of Izbrannyye partii by V. Smyslov (Moscow, 1952):

8093. The Winchester Whisperer

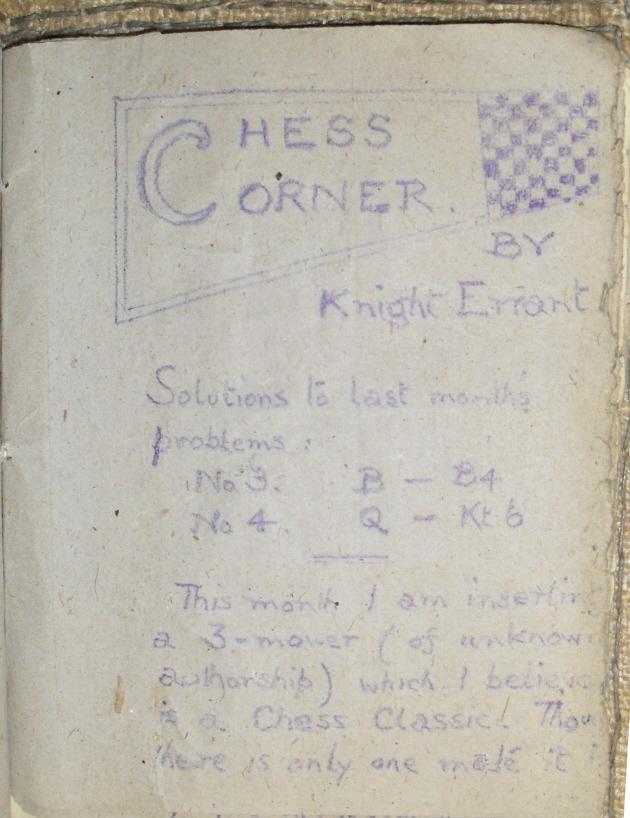

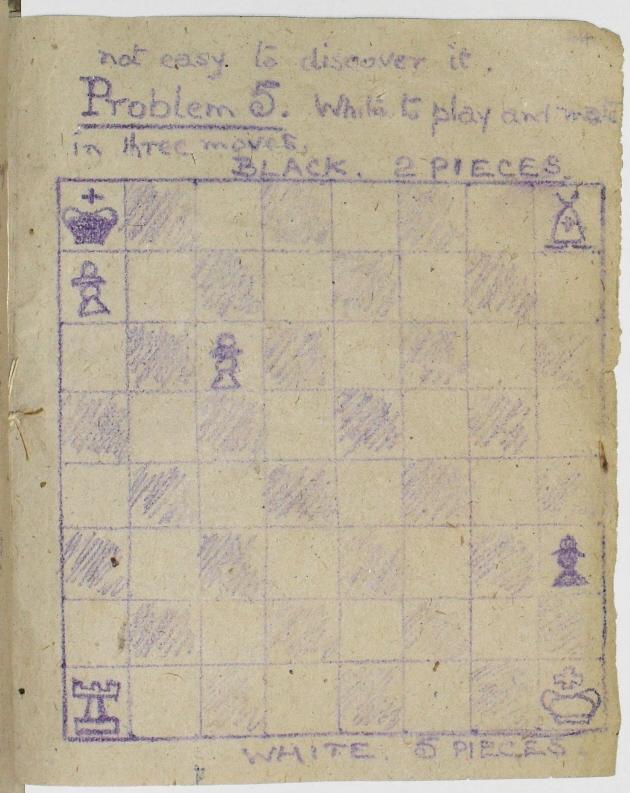

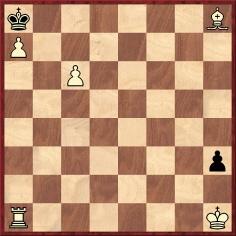

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) has forwarded a chess item from The Winchester Whisperer, a clandestine magazine produced by conscientious objectors in Winchester Prison, England during the Great War.

The scans were provided by the library at Friends House in London, and Mr McDowell comments:

‘There are no clues as to the identity of “Knight Errant”. He rather overestimates the quality of the problem. Some information about the source of the composition is given in the WinChloe database: “Eduard Petsch-Manskopf, Schachprobleme 1915”.’

Mate in three

8094. St Louis, 1941 (C.N. 8082)

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) provides a partial

key, drawn up with assistance from Walter Shipman and

David Cohen:

‘Seated from left to right: N.N., Herman Steiner, Reuben Fine, George Sturgis, L. Walter Stephens, Weaver Adams, Boris Blumin (subject to confirmation) and Hermann Helms.

Standing sixth from the left, Erich Marchand. On the far right, Joseph Rauch and Bruno Schmidt.’

8095. Early magnetic chess sets

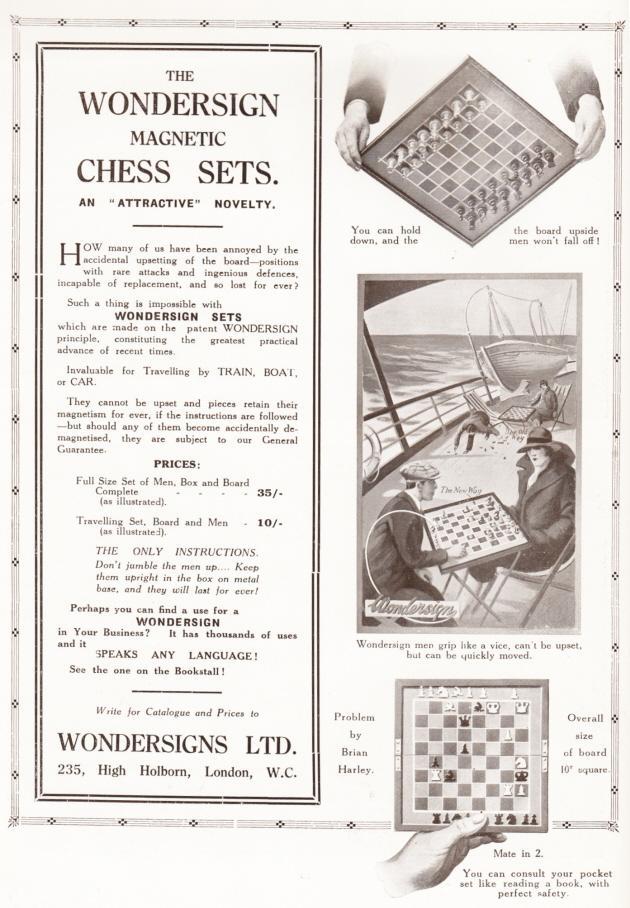

A few snippets, in reverse chronological order:

- Chess Pie, 1927, page 40 (Wondersigns Ltd. advertisement):

- American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1926, page 76:

‘An Antwerp inventor is seeking a market for a new magnetic chess board which, he suggests, will be specially useful when traveling. “The chess board, as it now exists”, he says, “is a great disadvantage when by the least knock given to the game table the figures fall or go back, especially in trains or boats, where the natural shocks unceasingly trouble the game, with the greatest inconvenience to the spectators.” He proposes to provide the “figures” (Anglice pieces) with magnetic bases, while his board has a covering of thin steel. The idea looks attractive. – The Australasian.’

- BCM, May 1920, page 134:

‘G.E. Owen wishes to know if anyone can inform him of his father’s invention, a magnetic chess board. He was a dentist, and resided at 24 Compton Terrace, Islington, from 1863 to 1883, and died at 11 Dalmeny Road, Tufnell Park, in 1886.’

On page 170 of the June 1920 issue W.O. Woodfield wrote:

‘The invention referred to is apparently No. 1,992 (1868), the abridged specification of which reads, “To hold the pieces in their places upon the board, each square is fitted with a magnet, and each piece with a disc of sheet iron, or vice versa.” Provisional protection only was granted to this application.’

- The Cincinnati Commercial, 4 March 1882:

‘A Berlin inventor has lately produced an iron chess board and chess men. In the men are concealed small magnets which cause them to adhere to the board to prevent displacement by the jar of railroad or steamboat traveling.’

8096. C.R.M. Talbot

A game played at the St George’s Chess Club and published on page 79 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1850:

Christopher Rice Mansel Talbot – H.G. Cattley

London, 1850

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Bc5 4 Bc4 d6 5 d3 h6 6 Be3 Bb6 7 Qd2 Bg4 8 h3 Bxf3 9 gxf3 Nbd7 10 O-O-O a6 11 d4 exd4 12 Bxd4 Bxd4 13 Qxd4 Ne5 14 f4 Nxc4 15 Qxc4 b5 16 Qc6+ Nd7 17 Nd5 O-O 18 Rhg1 Nf6 19 Qc3 Kh7

20 Rxg7+ Kxg7 21 Rg1+ Kh8 22 Nxf6 c5

23 Rg7 Kxg7 and White mates in three moves.

This was one of two wins by Talbot which were given on pages 73-74 of the February 1890 BCM following his death, and a note after 19...Kh7 included the remark ‘The mate now administered is a gem of the first water, and worthy of the greatest players’. The same issue (pages 46-47) reproduced Talbot’s obituary from The Times of 18 January, together with a note on his chess activity by William Wayte. In The Times the following observations had appeared:

‘Mr Talbot has gained the honour of being Father of the House of Commons after an experience which is almost unprecedented, for he has sat for the same constituency for no less than 59 years. His mother, Lady Mary, after his father’s death married Sir Christopher Coles, who was returned in 1820 for the county of Glamorgan. Sir Christopher kept the seat till 1830, when Mr Talbot himself stood as a Liberal, and was returned for the seat which he had ever since held. That Mr Talbot’s voice was never heard in the House of Commons is the more remarkable, because he was in point of fact a clever and ready speaker.’

Page 290 of the August 1882 BCM mentioned regarding Talbot’s political career that he was ‘the only member who dates from the unreformed Parliament’. The game against Cattley was also given on page 281 of the July 1898 BCM (with the artistic enhancement 22...b4).

See too Chess and the House of Commons.

8097. Chess and bridge

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘An addition to your list of authors of works on both chess and bridge is Hugh Baron Bignold (1870-1930), who edited the Australian Chess-Annual (Sydney, 1896) and conducted the chess column in the Sydney Morning Herald from 1895 to 1911. He also wrote Auction Simplified, a 26-page book published in Sydney in 1922.’

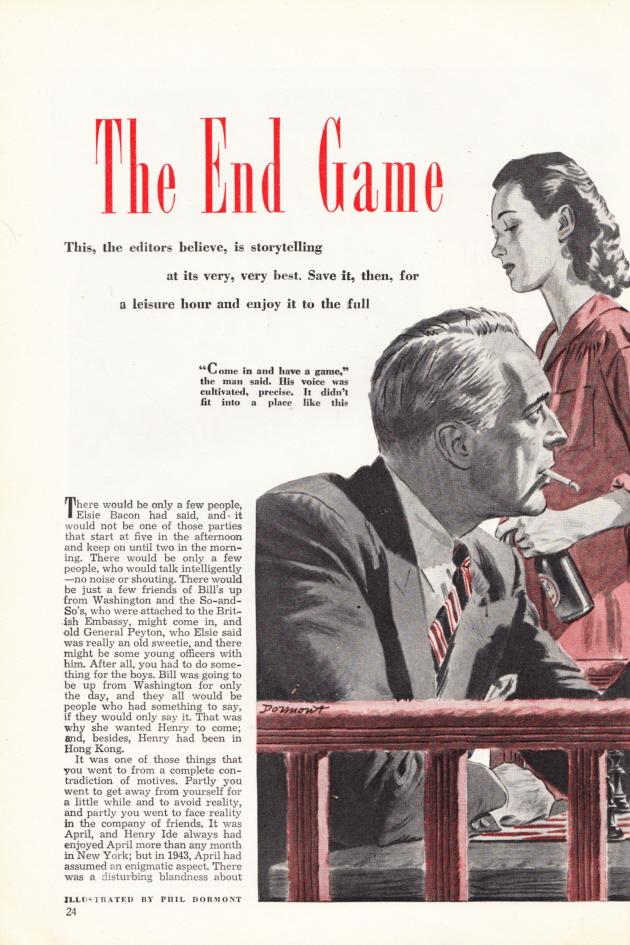

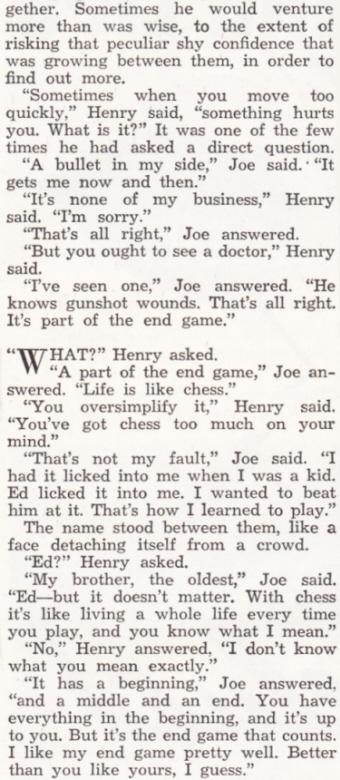

8098. The End Game

Has any reader seen the 1950 production (Pulitzer Prize Playhouse) The End Game? The short story by John P. Marquand was published on pages 24-25 and 145-179 of the March 1944 issue of Good Housekeeping, and also appeared on pages 144-194 of his anthology Thirty Years (Boston, 1954).

An illustrative excerpt from page 155 of Good Housekeeping:

8099. The plagiarism continues

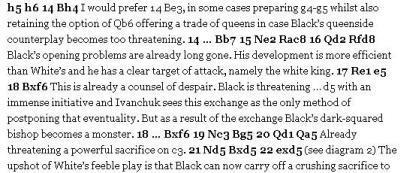

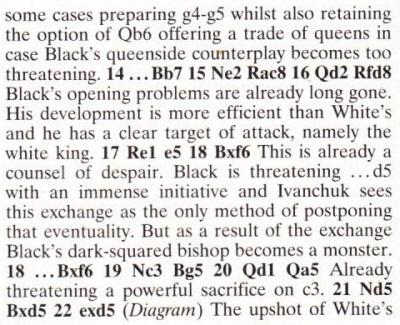

In a series of articles at the website of the Streatham & Brixton Chess Club, Justin Horton has reported on the conduct of Raymond Keene. The latest exposé of plagiarism concerns the game Alekhine v Rubinstein, Carlsbad, 1923, which Mr Keene published in The Spectator of 4 May 2013 with annotations lifted from volume one of Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors series.

8100. The Spectator again

Raymond Keene’s latest chess column in The Spectator (22 June 2013, page 66), available online, reveals another handy method of avoiding exertion. The column features the game Ivanchuk v Anand, Linares, 1998, without mentioning that the annotations merely repeat, word for word, what Mr Keene was paid for writing in his column on page 60 of The Spectator, 21 March 1998.

For example:

The Spectator (2013)

The Spectator (1998)

Addition on 28 June 2013: Pablo Byrne (London) points out a third occurrence in The Spectator of the same annotations to the Ivanchuk v Anand game, on page 58 of the 5 May 2012 issue.

8101. Journalism

As mentioned in C.N. 4218, on page 12 of his book Secrets of Grandmaster Chess (London, 1997) John Nunn reported that in a 1966 newspaper his name came out as ‘Jimmy Nunn’. (‘My opinion of the accuracy of journalists took a nose-dive and has been going down ever since.’)

It could have been worse. From page 71 of Il lessico degli scacchi by Yuri Garrett (Brescia, 2012):

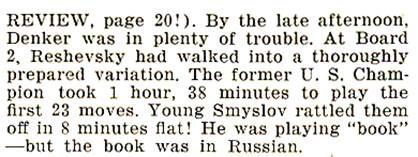

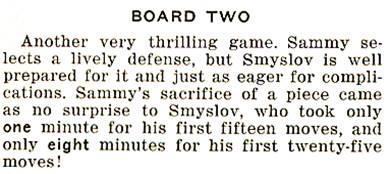

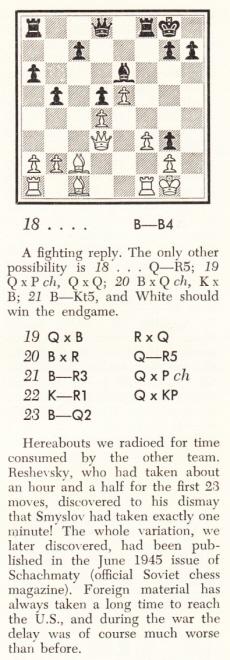

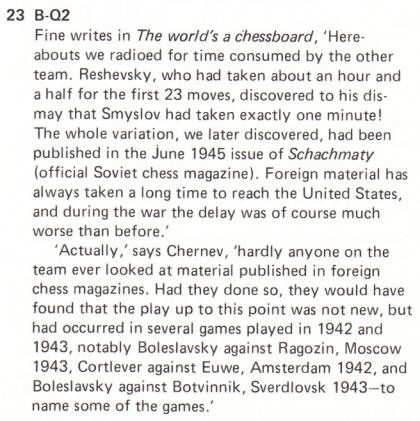

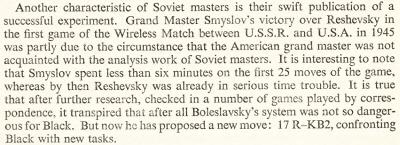

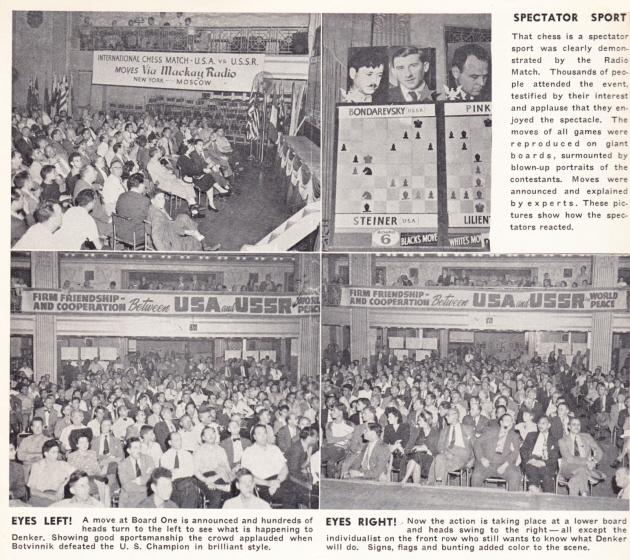

8102. Smyslov and Reshevsky in the 1945 USA v USSR radio match

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘The October 1945 Chess Review published extensive reports (including many fine photographs) on the USA v USSR radio match. The account (pages 5-11) by Kenneth Harkness, the match director, and the games section (pages 12-15) gave detailed information on the time consumed by Smyslov and Reshevsky in their two games:

Above: Smyslov v Reshevsky, round one (from pages 8 and 12).

Above: Reshevsky v Smyslov, round two (from pages 10 and 14).’

On the subject of the time consumed, we add an excerpt from page 267 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948):

Fine wrote similarly on page 246 of his book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951), but a comment by Irving Chernev on page 96 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) may be noted:

Finally, from page 24 of One Hundred Selected Games by Mikhail Botvinnik (London, 1951):

Reshevsky annotated the two games on pages 14-15 of the November 1945 Chess Review. Notes by Smyslov can be found on pages 105-110 of volume one of Smyslov’s Best Games (Olomouc, 2003).

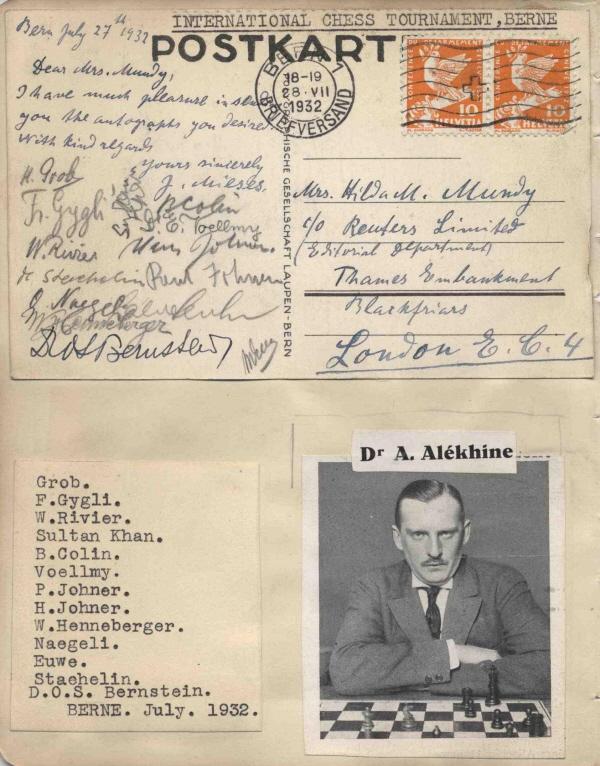

Chess Review, October 1945, page 8.

8103. Odds games

Myron Samsin (Winnipeg, Canada) writes:

‘Page 4 of Byrne J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959) states that Alekhine’s Defence “can be traced to the 1862 International Handicap Tournament of London”.

Two games between Anderssen and Pearson in that event did indeed begin 1 e4 Nf6, but White was giving the odds of his queen’s knight. Is it correct to assign an opening name from standard chess to a similar sequence played at odds? I am inclined to think not, because the tactics and themes are different.’

Our preference is not to use opening names for odds games. That, at least, avoids the inconsistency which arises in, for instance, the concluding part of Morphy’s Games of Chess by Philip W. Sergeant (London, 1916). Games played at the odds of the queen’s knight which began 1 e4 e6 are headed ‘French Defence’, but no opening heading appears when 1 e4 e6 occurred in a game in which Black offered the odds of his f-pawn. Another encounter in which Morphy gave the odds of pawn and move began 1 e4 d6, for which it might be difficult to suggest a suitable opening name.

8104. Fake chess photograph

We summarize, firstly, what has been established so far

regarding the fake

Alekhine-Capablanca photograph, supposedly taken

during the 1927 world championship match in Buenos Aires.

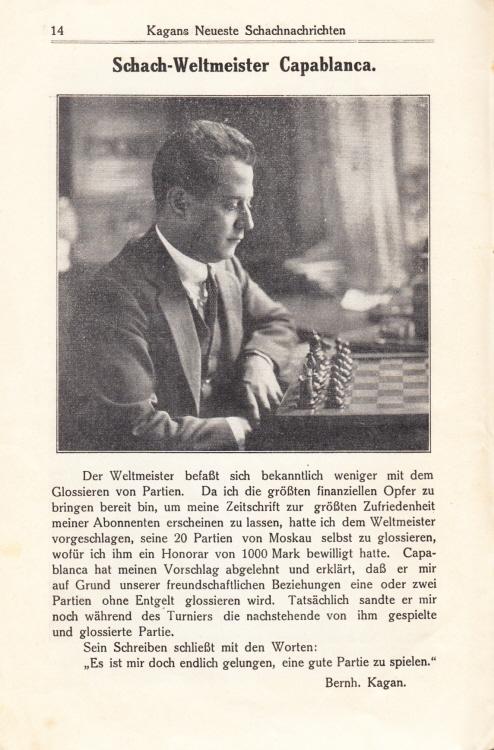

The picture of Capablanca was on page 14 of the ‘1. Extra-Ausgabe’ of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, published in late 1925 or early 1926:

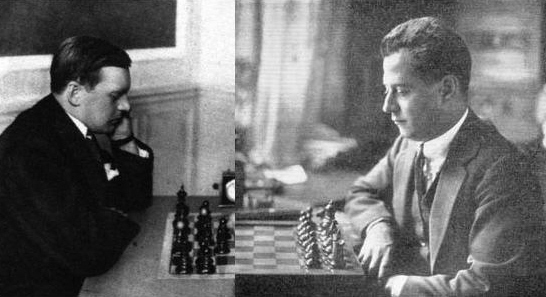

The shot of Alekhine was taken at Semmering, 1926 and was published on page 8 of Wiener Bilder, 28 March 1926 (C.N. 7971).

A crude juxtaposition of the two pictures, with reversal of the Capablanca one, gives this:

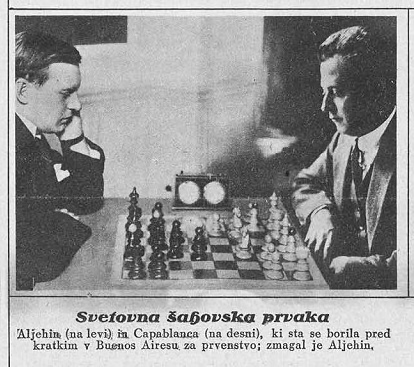

When the fake photograph appeared in the book on the 1927

world title match edited by Alekhine’s brother, Alexei,

i.e. Match na pervenstvo mira Alekhin-Capablanca

(Kharkov, 1927), it was described as taken on the first

day of the match. To date, that has been the earliest

known publication of the picture.

Now, however, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) has found that it had been printed on page 358 of Ilustrirani Slovenec, 30 October 1927:

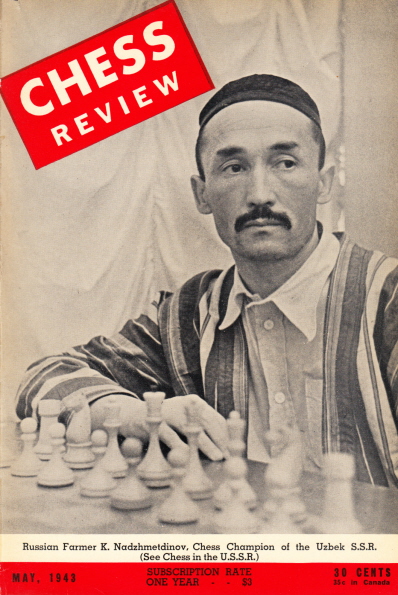

8105. Who was K. Nadzhmetdinov? (C.N. 3755)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘As noted in C.N. 3755, the May 1943 issue of Chess Review reported that K. Nadzhmetdinov was the winner of the 1939 championship of Uzbekistan. Unfortunately, there is no record of that event on the RUSBASE website, but there is a link to the crosstable of the 1939 USSR Kolkhoz (Collective Farm) Championship. In that event the Uzbek player K. Nadzhmetdinov finished in a tie for second place with Kiselev. Another website (КАРЛУША НА ЛУНЕ) has a report on the tournament; the page appears to cite archival material from the magazine Shakhmaty v SSSR, but I do not have the 1939 issues.’

Below is the tournament report, followed by our correspondent’s English translation:

‘ПЕРВЕНСТВО СССР СРЕДИ СЕЛЬСКИХ ШАХМАТИСТОВ – традиц. соревнование, проводимое с 1939.

I турнир колх. шахматистов СССР состоялся 16-30 авг. 1939. Он явился результатом большой подготовительной работы на местах. Игра происходила в Москве, на территории Всесоюзной сельскохо-зяйств. выставки. 10 республик послали своих представителей.

Звание чемпиона завоевал туркм. колхозник Ташли Тай-лиев, выигравший в финале все партии. 2-3. Киселев (РСФСР) и Наджметдинов (Уз. ССР) – по 7; 4. Хилько (УССР) – 5; 5. Богатырев (БССР) – 4½; 6-7. Акопян (Арм. ССР) и Рахимов (Тадж. ССР) – по 4; 8. Шмидт (Аз. ССР) – 2½; 9. Цулукидзе(Груз. ССР) – 2; 10. Чотыев (Кирг. ССР) – 0.’

‘USSR CHAMPIONSHIP AMONG RURAL CHESSPLAYERS – a traditional event first held in 1939.

The first USSR tournament of collective farm chessplayers was held on 16-30 August 1939. It was the culmination [literally, result – D.S.] of an enormous amount of preparatory work in the field. Play took place in Moscow, on the grounds of the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition. Ten republics sent their representatives.

The title of champion was won by the Turkmenistan collective farmer Tashli Tailiev, who won all his games in the final. Other scores: 2-3. Kiselev (RSFSR) and Nadzhmetdinov (Uzbek SSR) – 7 points; 4. Khilko (Ukraine SSR) – 5 points; 5. Bogatyrev (Belorussian SSR) – 4½ points; 6-7. Akopian (Armenian SSR) and Rakhimov (Tadzhik SSR) – 4 points; 8. Schmidt (Azerbaijan SSR) – 2½ points; 9. Tsulukidze (Georgian SSR) – 2 points; 10. Chotyev (Kirghiz SSR) – 0 points.’

8106. Znosko-Borovsky

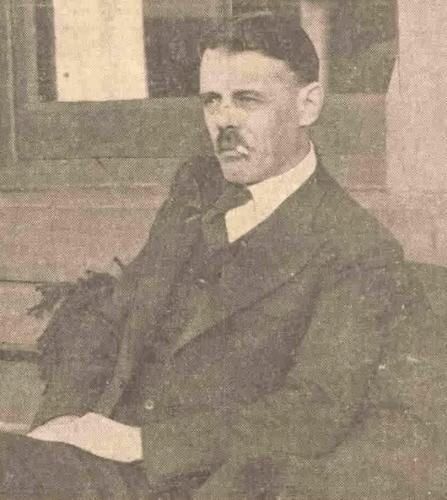

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) reports that a photograph of Eugène Znosko-Borovsky appeared on the front page of the Evening Telegraph and Post (Dundee, Scotland), 27 November 1936:

From page 93 of the February 1937 BCM:

8107. 1 e4 Nf6 (C.N. 8103)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that pages 210-211 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1862 published a game which began 1 e4 Nf6 and was not played at odds:

Berwick Chess Club – Edinburgh Chess Club

Correspondence, November 1860-15 November 1861

Alekhine’s Defence

1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Ng8 3 d4 e6 4 Bd3 c5 5 Nf3 cxd4 6 O-O Nc6 7 Re1 d6 8 Bb5 d5 9 Nxd4 Bd7 10 c3 Bc5 11 Be3 Bxd4 12 Bxd4 Nge7 13 Bxc6 Bxc6 14 Qd3 O-O 15 f4 Nf5 16 Nd2 Qh4 17 Rf1 a6 18 a4 f6 19 exf6 gxf6 20 Rf3 h6 21 Nf1 Qh5 22 Rh3 Qf7 23 Ng3 Qh7 24 Nxf5 exf5 25 Qe2 Rae8 26 Rg3+ Kh8

27 Qh5 Re4 28 Qh4 Rxd4 29 cxd4 h5 30 a5 Be8 31 Re1 Qd7 32 Rge3 Bg6 33 Qg3 Bf7 34 Re7 Qb5 35 Qc3 Bg6 36 Qc5 Qxc5 37 dxc5 Rb8 38 Rd1 Be8 39 Rxd5 Bc6 40 Rxf5 Rd8 41 Rxf6 Rd1+ 42 Kf2 Rd2+ 43 Kf1 Resigns.

8108. Dealing with plagiarists and swindlers

From T.R. Dawson’s column on pages 620-621 of the December 1936 BCM:

‘“Warned Off.” Die Schwalbe (November, page 628) reports that an Italian “composer”, E. Battaglia, is definitely guilty of seven new plagiarisms in 1935-36, and should be barred from competing in any tourneys. There have been a few admitted and persistent plagiarists in the past, but I do not recall quite such a blatant public notice as the above. Usually in this country problem-editors exchange private opinions about the occasional misguided swindlers of the kind and quietly drop them.’

8109. Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) writes:

‘There is an article about Jacqueline Piatigorsky by Robert Cantwell on pages 22-27 of Sports Illustrated, 5 September 1966. The photograph of her with Fischer and Spassky on page 27 would seem to be little known.’

Courtesy of John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) we

reproduce below a photograph of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

during her ten-move win against Willa W. Owens in the 1951

US Women’s Championship in New York. For the game-score,

see C.N. 5436.

The picture comes from Mrs Piatigorsky’s archives and was taken by a fellow participant, Nancy Roos, who was a professional photographer.

8110. The Immortal Game

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘It appears that one of the most “popular” books using chess history as an overall theme is David Shenk’s The Immortal Game (New York, 2006), subtitled “A History of Chess or How 32 Carved Pieces on a Board Illuminated Our Understanding of War, Art, Science, and the Human Brain”. I find it exceedingly disappointing in terms of sourcing, as it strikes me as very amateurish, if not downright naïve.

What to make of the dozens of references to notoriously inaccurate websites? The endnotes on pages 287-313 indicate virtually no use of primary sources (the meat of any serious book dealing with history in general) or of reliable secondary sources.

Below are just a few examples of the kind of “authorities” upon whom the text relies (the numbers in brackets refer to the pages where the corresponding endnotes appear):

- Page xvi (287-288): the alleged game between Einstein and Oppenheimer is given as a certainty despite the lack of trustworthy sources (as documented in C.N.s 3533, 3667, 3691 and 4133). An endnote offers no source for the game, merely sending the reader to “an animated version” at a highly undependable website, chessgames.com;

- Page 7 (288): a list of historical religious leaders who attempted to ban chess is sourced to a web article by Bill Wall;

- Page 23 (294): for details about Adolf Anderssen’s life the reader is referred to another online article by Bill Wall;

- Page 35 (294): for a problem by a ninth-century Arab composer we are again sent to a Bill Wall page;

- Page 92 (300): Bill Wall is once more the source for names of members of the eighteenth-century American intellectual elite who played chess;

- Pages 114-115 (303): Samuel Rosenthal’s own words on chess and war are cited, but the endnote credit is incomplete at best: “From obituary in a French newspaper, September 1902”;

- Page 115 (303): we are referred to a logicalchess.com link to prove that Rosenthal “won the first French chess championship in 1880”; the same pages state that Rosenthal “managed to beat legendary players” and that “chessgames.com database has all actual games”;

- Page 143 (305): a number of chessplayers allegedly suffering from mental illness are listed; sourcing includes links to the webpages of Bill Wall and chessgames.com;

- Page 149 (305): Charles Krauthammer is cited as a “writer, psychiatrist, and serious chessplayer”. In his chess-related writings he has often recycled clichés related to the game’s history (see, for instance, his Time essay and the discussion in your Steinitz versus God article);

- Page 164 (306): the statement “When the Germans captured France in 1940, Alekhine agreed to write about and play chess on their behalf in order to protect his family’s assets” is sourced to a Bill Wall webpage;

- Page 168 (306): details of the USA v USSR 1945 radio match are sourced to another Bill Wall webpage;

- Page 173 (307): the statement that “After a tournament in Yugoslavia in 1970, he [Fischer] was able to recall instantly every move from each of his 22 games – totaling more than a thousand” is credited to a Fischer profile on a www.poster-chess.com webpage;

- Page 174 (307): a statement by Henry Kissinger (“I told Fischer to get his butt over to Iceland”) is credited to Rene Chun. In the same paragraph, the author notes that “It is, however, still a matter of dispute whether Fischer actually took Kissinger’s call”;

- Page 175 (307): details of Spassky’s chess career are attributed to a Wikipedia entry;

- Page 226 (312): Kieseritzky’s death details are sourced to a Bill Wall page.

Other deeply unimpressive sources include websites like chessville.com, goddesschess.com and worldchessnetwork.com, as well as individuals like Larry Parr and Andrew Soltis.’

8111. J. Polgar v Angelova

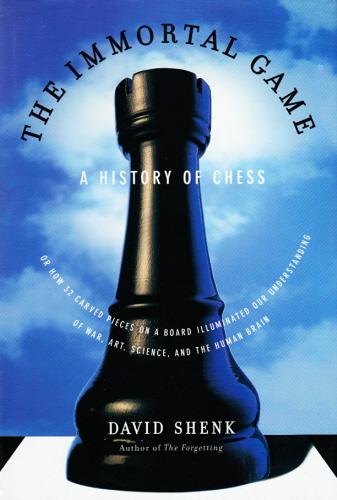

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 g6 4 O-O Bg7 5 c3 e5 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 Nxd4 8 Nxd4 cxd4 9 e5 Ne7 10 Bg5 O-O 11 Qxd4 Nc6 12 Qh4 Qb6 13 Nc3 Bxe5 14 Rae1 Bxc3 15 bxc3 Qxb5 16 Qh6 Qf5

17 Qxf8+ Resigns.

Concerning Judit Polgar’s victory over Pavlina Angelova at the 1988 Olympiad in Thessaloniki, shortly afterwards (on 14 January 1989) Richard Reich (Madison, WI, USA) wrote to inform us that the whole game had been given on page 44 of The Anti-Sicilian: 3 Bb5(+) by Y. Razuvayev and A. Matsukevitch (London, 1984), which mentioned ‘Levchenkov-Eganian, USSR, 1978’:

This was reported in the January-February 1989 issue of Chess Notes (C.N. 1806). See too page 200 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

Can readers find documentation to corroborate, and expand upon, the reference ‘Levchenkov-Eganian, USSR, 1978’?

8112. The ‘English Chess Association’

The English Chess Federation is the game’s official body in England, but there is a question long overdue for discussion and clarification within English chess circles:

| First column | << previous | Archives [107] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.