Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [83] | next >> | Current column |

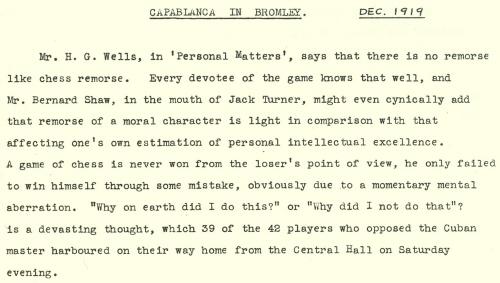

7099. Capablanca in Bromley

Daniel King (London) has sent us a copy of a typescript report by Jean Raoux on Capablanca’s simultaneous exhibition in Bromley, England on 20 December 1919:

‘Mr H.G. Wells, in “Personal Matters”, says that there is no remorse like chess remorse. Every devotee of the game knows that well, and Mr Bernard Shaw, in the mouth of Jack Turner, might even cynically add that remorse of a moral character is light in comparison with that affecting one’s own estimation of personal intellectual excellence. A game of chess is never won from the loser’s point of view, he only failed to win himself through some mistake, obviously due to a momentary mental aberration. “Why on earth did I do this?”or “Why did I not do that?” is a devasting thought, which 39 of the 42 players who opposed the Cuban master harboured on their way home from the Central Hall on Saturday evening.

The meeting was opened by the Mayor of Bromley, Alderman W.L. Crossley who, in a felicitous little speech, extended a hearty welcome to Señor Capablanca. Chess, he understood, had evolved westwards from India, possibly even from China. When it actually came to Bromley he could not say, a very long time ago, certainly. He himself had been one of the first members of the old Bromley Chess Club, and as such felt all the more pleased to receive one of the greatest of modern chess masters.

Responding to this address of welcome, Señor Capablanca expressed in a few words his great pleasure at so cordial a reception. His ambition was to foster chess wherever and whenever possible and he would like to think that his visit would have this result in Bromley.

Mr J.S. Holloway then proposed a vote of thanks to his Worship the Mayor for so kindly lending the distinction of his presence at this meeting, calling upon Alderman F. Gillett, Deputy-Mayor, to second his motion.

Alderman F. Gillett readily endorsed the motion in a witty speech, and ended by also tendering, on behalf of all present, the best thanks of the chess-playing public to Mr Holloway for his untiring and very successful efforts in promoting chess in the district.

Mr Holloway, speaking again, gave some particulars about the display and the rules to be observed. Some strong players had been pitted against Señor Capablanca. Mr Chapman (many times champion of the county), Mr Germann (also an ex-champion of Kent), and Mr Lorch; not omitting the British lady champion, Mrs Holloway.

Preliminaries being over, the Cuban master set to his task in grim earnest. Perfectly cool and collected, without any apparent effort, he passed from board to board, giving his moves almost at once, looking far less concerned, with 42 players to contend with, than any one of his opponents did. As usual, he was partial to the ultra-modern and classical Ruy López and Queen’s Pawn openings, with here and there a “Vienna” or a Centre Gambit to relieve the monotony. All of them he treated very carefully. His plan of campaign was obviously to avoid complications and intricate positions and to see first his own safety. This policy is not adopted for the sole convenience of simultaneous play, but actually constitutes his style, such as will consistently be recognized as Capablanca’s, no matter whether he meets his great rival, Lasker, or amateurs of moderate strength. He hankers not after brilliancies and spectacular combinations.

Many people in this country will remember Marshall’s performances, and will notice the contrast between the two great experts. Marshall is the fighter, as ready to receive blows as to inflict them, risking his king for a brilliant finish, ingenious, clever, and at times sublime, scoring almost fantastic victories and also tasting ignoble defeats. The strain of the struggle is clearly written on his eagle features, his inevitable cigar is a poem in itself. Capablanca does not seem to fight, but rather to demonstrate, with frigid exactitude, the error of his opponent’s conceptions and concludes a three or four hours’ contest apparently as fresh as when he started. He caters for the student of chess, yet he is remarkably popular with all grades of players. The average amateur might prefer to watch a display by a Chigorin, a Marshall or a Nimzowitsch, as being more exciting, hence more entertaining, but whereas he will feel that those masters rely on great imaginative powers – which he himself lacks – and that they are therefore outside his imitative scope, Capablanca gives him the impression that nothing is easier than chess, and that by assimilating his style he can improve his own play considerably. But can he hope to acquire this wonderful intuition into the far ahead possibilities of the game which enables Capablanca to detect a win in an apparently even position? Here lies the characteristic beauty of his style and its justification. Once the win is detected, however remote it may be, nothing else matters, other chances he does not trouble about. From a winning position Tarrasch would want to exact the utmost he thinks it mathematically capable of; Capablanca is content to get from it the narrowest necessary margin to score.

Both the two great schools, the scientific and the imaginative, can claim Capablanca, but not without reservations. The scientific school seeks truth in chess by accumulation of knowledge, the imaginative by ever higher inspiration. Both have had and have their exponents, but both have failed to convince the unprejudiced player of their exclusive excellence. One cannot imagine Capablanca fraternizing unreservedly with the uncompromising orthodoxy of a Tarrasch, and yet less still with the unconventional methods of a Marshall. That he has actually founded a new school, as some people are prone to proclaim, is exceedingly doubtful. At least, it would have but few adepts, for Nature seldom blends in the one same man a mathematician and a poet. Morphy left no school, no player could follow its teaching. He would have been a leader of supermen, but mere mortals could but admire him as we admire Capablanca today.

Capablanca’s steady way of proceeding made it unlikely that any quick results would be attained. One of the earliest was on Mr Th. Germann’s board, where the master had been in difficulties from quite early in the game through accepting a proffered pawn in the centre. Pushing his attack in a very energetic manner, Mr Germann compelled Capablanca’s resignation on the 23rd move, finishing neatly with a sacrifice of a rook. The game is given below. Mr Chapman lost the exchange, from which there was no recovery, in spite of a very gallant fight. Mr Lorch seemed to have good drawing chances all through the game, but finally succumbed. He had at least the satisfaction of being the last to hold out.

Mr H. Holliday, member of the Bromley Chess Club, was playing well, and secured for himself the distinction of a draw. It is to be regretted that he did not take down the score of the game. The only other draw the master had to concede to was to Mr J.H. Whicker, jun. of the Sydenham and Forest Hill Chess Club. Messrs Holliday and Whicker are both young and enthusiastic players, and their success in staving off defeat at the hands of so formidable an opponent will no doubt urge them on to further efforts.

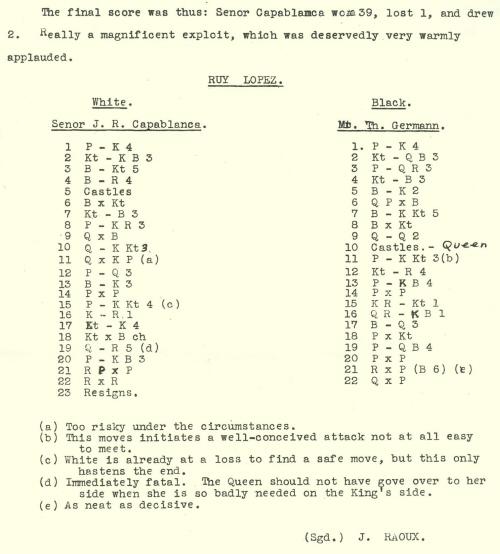

The final score was thus: Señor Capablanca won 39, lost 1, and drew 2. Really a magnificent exploit, which was deservedly very warmly applauded.’

The conclusion of the typescript:

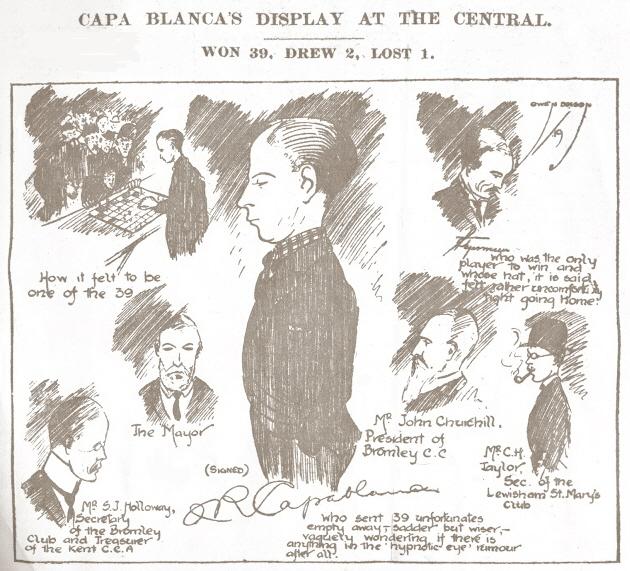

The Capablanca v Germann has been quite widely published. Our archives contain the reports on the display published in The Chronicle and the Bromley Mercury of 24 December 1919. All 42 of Capablanca’s opponents were named, and the latter newspaper had this illustration:

See also pages 346-354 of Capablanca in the United Kingdom (1911-1920) by V. Fiala (Olomouc, 2006), which gave a second game-score from the display, the quick defeat of Major Richard Whieldon Barnett MP.

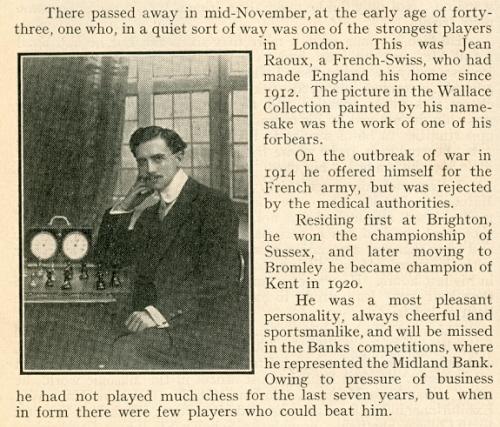

Jean Raoux was the Secretary of the Bromley Chess Club at the time of Capablanca’s display. Below is his obituary on page 14 of the January 1931 BCM (a few pages after Barnett’s death notice):

7100. 4 g4 in the Caro-Kann Defence

When was the so-called ‘Bayonet Attack’ in the Caro-Kann Defence (1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 g4) first played and/or discussed in print?

4 g4 occurred in Réti v Sterk, Debrecen, 1913, but Marshall’s name was mentioned in a note to that move in the game M. Levine v A.E. Santasiere, Metropolitan League match, 11 March 1922:

‘This is an innovation suggested by Marshall, the idea being either to drive back the bishop with loss of time, or to hinder the development of the king’s side, as in the present instance.’

Source: American Chess Bulletin, March 1922, page 48.

7101. Marshall and gold coins

Regarding the Marshall gold coins story, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes:

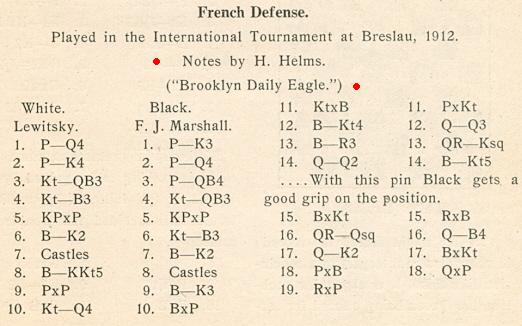

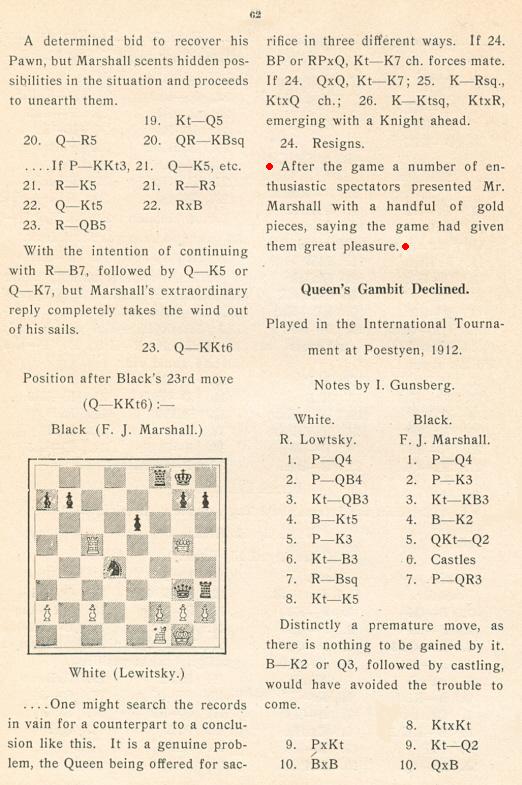

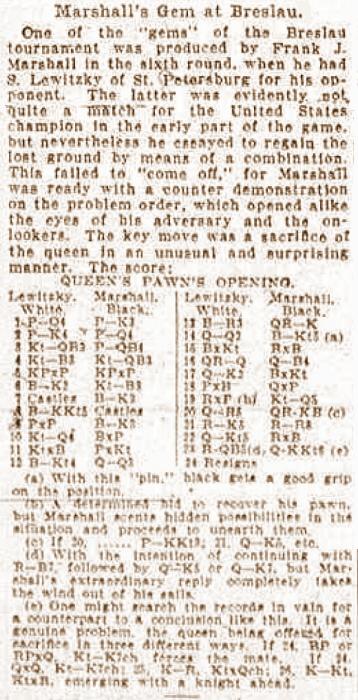

‘As Owen Hindle observed in C.N. 2148, pages 61-62 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” stated that the book’s notes to the Levitzky v Marshall game were reprinted from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (without any date being given). Marshall’s readers were left to assume that the key words at the end (“After the game a number of enthusiastic spectators presented Mr Marshall with a handful of gold pieces, saying the game had given them great pleasure”) had been written by Hermann Helms, the chess editor of the Eagle.

Pages 61 and 62 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” (New York, 1914)

In fact, the game – with the same annotations as in the Marshall book – had appeared on page 3 of the 8 August 1912 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, with the notable exception that Helms made no mention of gold pieces:

Thus, the comment about gold on page 62 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” seems to be an addition by Marshall himself.

The game was also published in the New York Sun, 18 August 1912, page 8, with annotations but no gold coins story. The score appeared too in the New York Evening Post of 21 August 1912 with Emanuel Lasker’s annotations, in a report from Berlin dated 9 August. Lasker made no mention of gold.

Page 8 of the 25 August 1912 issue of the New York Sun had the following about Levitzky:

“The Liverpool veteran Amos Burn in speaking about the Breslau international tournament gives the following information about the Russian player Levitzky:

‘One of the most interesting players of the lesser-known masters at the tournament is Levitzky, who lives on the borders of Siberia. Far from civilization, he has scarcely any opportunities for practice, or he would take a very high place among the world’s chess masters. He is undoubtedly a player of great natural talent. He has played a few games with Alekhine,who competed at Carlsbad last year, and who recently won the tournament at Stockholm. Alekhine had a majority of one in his games with Levitzky, but, of course, has much better opportunity for practice. Levitzky is 35 [sic] years old, tall, with yellow hair and beard. Knowing only a few words of German, he talks very little at Breslau, but in any case he is a silent man and of a particularly retiring disposition.’”

When the Levitzky v Marshall game was published on page 16 of the 25 May 1942 issue of the New York Post (H.R. Bigelow’s column) it was prefaced as follows:

“Here is the Levitzky-Marshall game which so pleased the spectators in the 1912 International Tourney at Breslau that they made a collection of gold (yes, we said ‘gold’) pieces for our Frank right after its conclusion.”

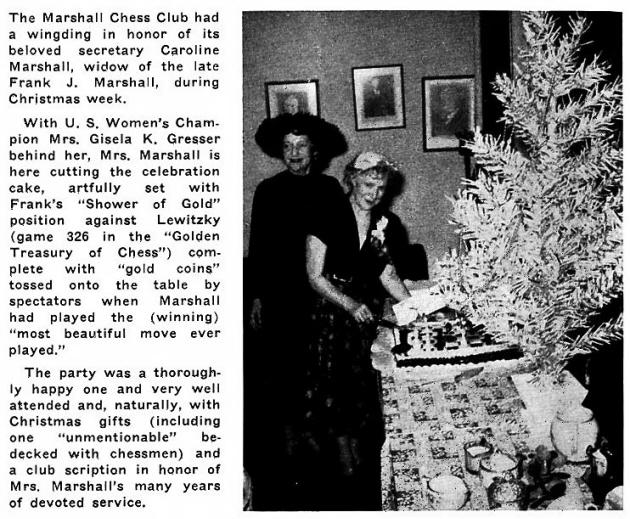

Finally, with regard to Al Horowitz’s statements in All About Chess that Caroline Marshall denied knowledge of the existence of any “gold coin shower”, the photograph and caption on page 68 of the March 1959 Chess Review may be noted:’

7102. Last round at Nottingham

This article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, comes from pages 76-77 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984), having previously appeared in the November 1981 Newsflash:

‘The BM was a spectator at the last round of the famous Nottingham, 1936 tournament. Botvinnik and Capablanca were leading with 9½ points each, and neither could possibly be equalled by any other competitor unless he lost. Both in fact were fully expected to win, “Capa” with White against Bogoljubow (whose score was 5) and still more Botvinnik against Winter (whose score was 2 consisting of 9 losses and 4 draws) though he had produced such fine chess in some of his games that his play could have almost brought an action for libel against his score. The hours of play on the final day were 9.30 to 1.30 and then 3 p.m. to the finish of the last game. As often happens, not much fur was flying for the first two hours or so, but then the “Capa-Bogol” game livened up considerably. About noon “Capa” won the exchange in a complex position; but then came a sensation which brought everyone to his board – the great Cuban had made a palpable oversight enabling Black to massacre almost all the white pawns, and exposing the white king, in his denuded state, to a raking crossfire from two powerful bishops. He seemed almost in a mating net, and though he ingeniously kept afloat until the interval, “Capa” was still in a position of extreme danger. It is unlikely that he took much lunch, for the BM espied him through the open door of a “Players Only” anteroom standing at a chessboard and analysing (by himself, of course) for all he was worth. On the resumption he got into smoother water and finally scraped a draw by returning at the right moment the exchange he had won at the outset. And so the relieved “Capa” and his jolly, friarlike opponent, shook hands.

In all this excitement, Botvinnik v Winter had been practically forgotten, but it now emerged that they had also agreed to a draw (whether during the interval or immediately after, the BM cannot remember). The resulting equal first (Capablanca 10 Botvinnik 10) pleased and satisfied everybody. For the former it was the culmination of a great career, and at the same time it turned Botvinnik (whose modesty had made an immensely favourable impression on everyone) into a national hero at home. As for Winter, he had been so much expected to lose to the “all-conquering Russian” that he was considered to have done well in “tenaciously holding him to a draw” and thus (as everyone saw it) enabling the popular Cuban veteran to share the honours with the equally popular rising star of the Soviet Union.

But later, when Botvinnik v Winter came to be annotated, both J.H. Blake (BCM) and A. Alekhine (tournament book) pointed out that Winter had done more than “tenaciously hold his own”. He had obtained, if not a clear win, such a considerable advantage that the draw really provided Botvinnik rather than Capablanca with the vital half-point. At this a few cynics (knowing Winter’s left-wing views) “shot out their lips and shook their heads, saying ...”. But at this period the Chess World was not cursed with “political awareness” to anything like the extent it is now; and all who knew Winter knew also that in his eyes chess probity would always take precedence over “leftist loyalties”. In fact, he had had an exhausting tournament dogged by ill-luck and handicapped by Press work – two rounds earlier he had thrown away a win against Capablanca – and he was probably still under the influence of this and unwilling to risk a repetition of the disaster.’

7103. Alexander v Marshall (C.N.s 3508, 5262, 6624, 6653 & 6747)

C.N. 3508 opened a discussion of an Alexander v Marshall game (‘Cambridge, 1928’), the main point of interest being this position:

After 1 Rf4 exf4 2 gxf4 dxc3 Black controls g1, and the winning line was therefore given as 1 Na4 bxa4 2 Rf4 exf4 3 gxf4, after which 4 Rg1+ leads to mate.

Not until C.N. 6747 could a source from the 1920s be presented, but now the full details of the game have been found by Alan Smith (Manchester, England):

Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander – E.T. MarshallCambridge University v Lud-Eagle match, 1 December 1928

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 Bc4 d6 4 d3 Nc6 5 f4 Nf6 6 Nf3 O-O 7 f5 Na5 8 Bg5 c6 9 a3 b5 10 Ba2 Qb6 11 Qe2 Nb7 12 Nh4 a5 13 Bxf6 gxf6 14 Rf1 Be3 15 Qh5 Bf4 16 Nd1 Nd8 17 g3 Be3 18 Ke2 Bc5 19 Qh6 d5 20 Nc3 d4 21 Rf4 exf4 22 Na4 f3+ 23 Nxf3 Qa7 24 Nxc5 Bxf5 25 g4 Bg6 26 Nxd4 Qxc5 27 Nf5 Bxf5 28 gxf5 Ne6 29 c3 Qe7 30 fxe6 fxe6 31 Rg1+ Kh8 32 Bxe6 Rae8 33 Bf5 Rg8 Drawn.

Sources: The Observer, 16 December 1928, page 25, with details concerning the match in The Times, 3 December 1928.

7104. Scheveningen, 1913

In the fourth round of Scheveningen, 1913 Yates scored a point against Breyer by forfeit, because of Breyer’s failure to appear (tournament book, page x). A more detailed account was given by L. Hoffer on page 270 of The Field, 2 August 1913:

‘An unpleasant incident occurred in Breyer appearing after his clock had run one hour, and the game was scored to Yates under the rules. Heer Weisfelt (hon. sec.) telephoned to the hotel in time, and the message came that Breyer had gone out long ago. It turned out afterwards that he mistook Alekhine for Breyer – there is such a likeness between them – so nothing could be done but to let the clock run. Breyer said afterwards that he would never stay with Alekhine in the same hotel. Not to be idle, he challenged Yates to a game for a stake of 10 florins, which Yates immediately accepted; it was not finished when time was called.’

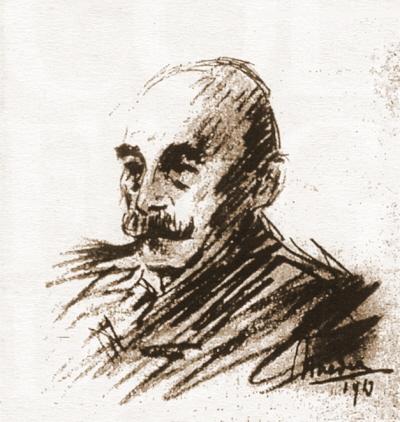

Hoffer, who died on 28 August 1913, was present in Scheveningen. In the same column he wrote:

‘Among the visitors was M. Nardus, who generously offered to supply The Field with his sketches of the players at the chessboard. Although sketching at lightning speed, and under great difficulties, the players themselves shifting their positions constantly and the spectators standing in front of the artist, so that he could only catch occasional glimpses of the subjects, he succeeded, nevertheless, in completing five pictures (see page 301), the others to follow au fur et à mesure, as he said, when they are ready.’

The five sketches by Léonardus Nardus:

Leopold Hoffer

Gyula Breyer

Jacques Mieses

Rudolf Loman

Georg Olland

7105. N.N. v Nimzowitsch (C.N.s 6962 & 6969)

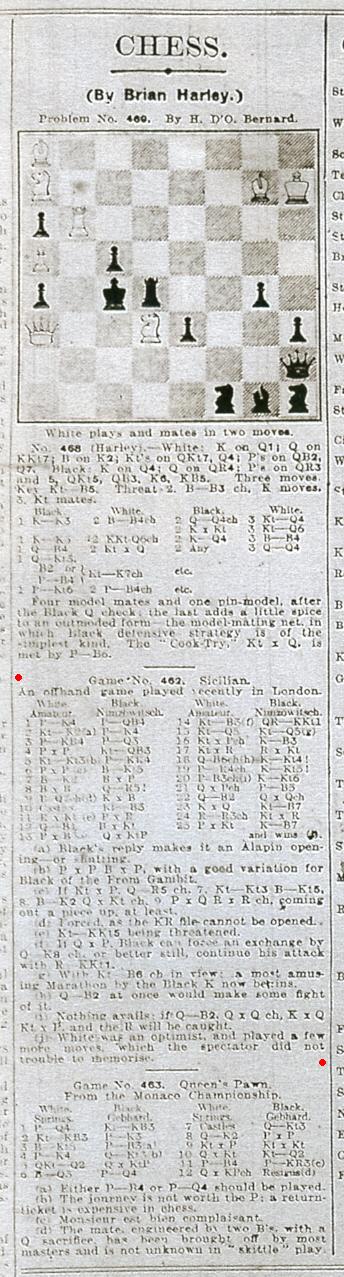

We have now obtained a copy of the column by Brian Harley (page 25 of The Observer, 25 March 1928):

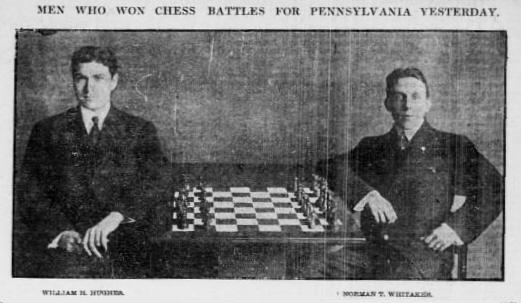

7106. William H.

Hughes and Norman T. Whitaker

From Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia) comes this photograph on page 5 of the New York Tribune, 30 December 1908:

Concerning the event in question, see pages 10 and 344 of Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 2000).

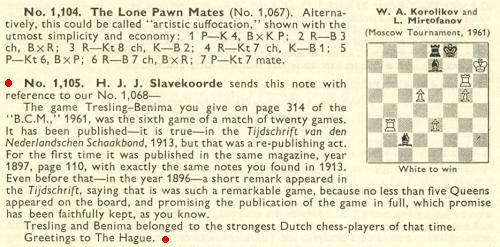

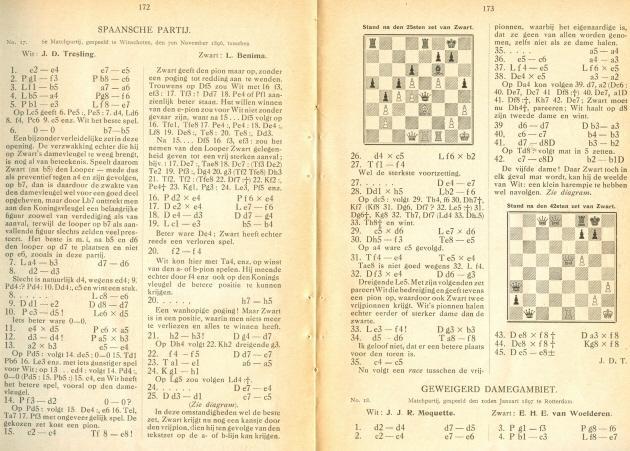

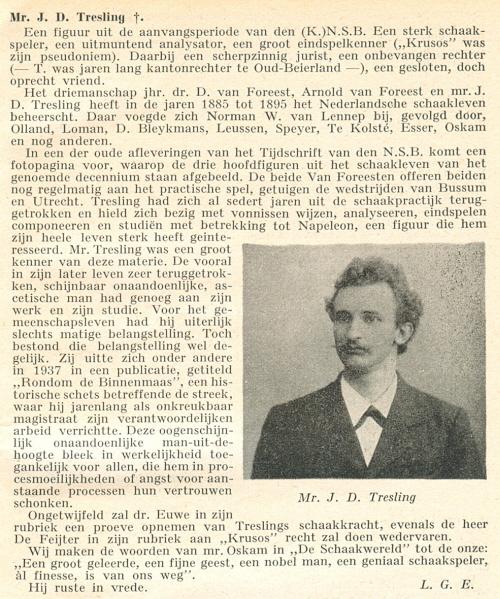

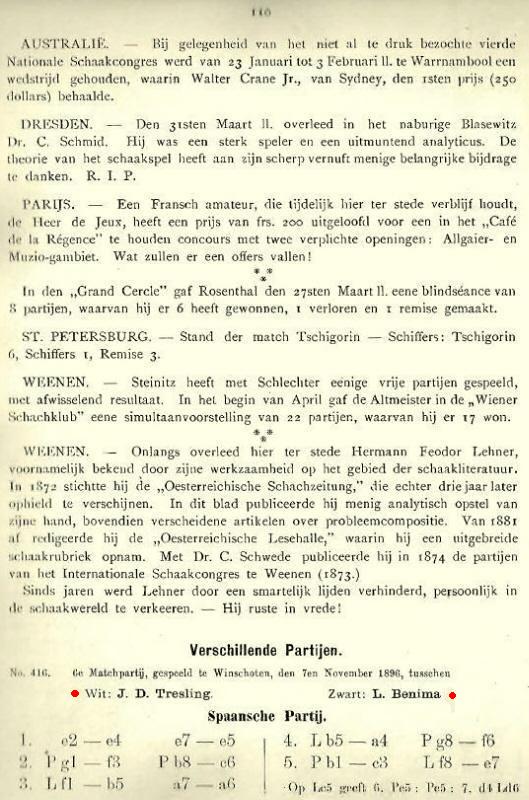

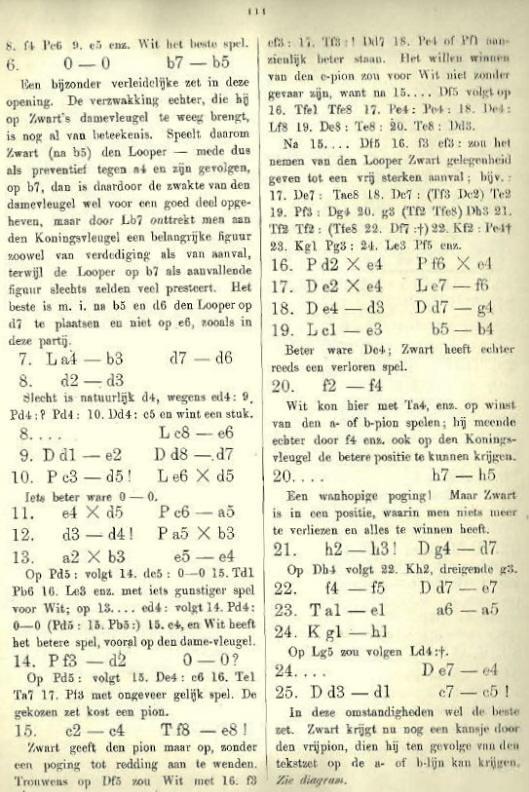

7107. Tresling v Benima

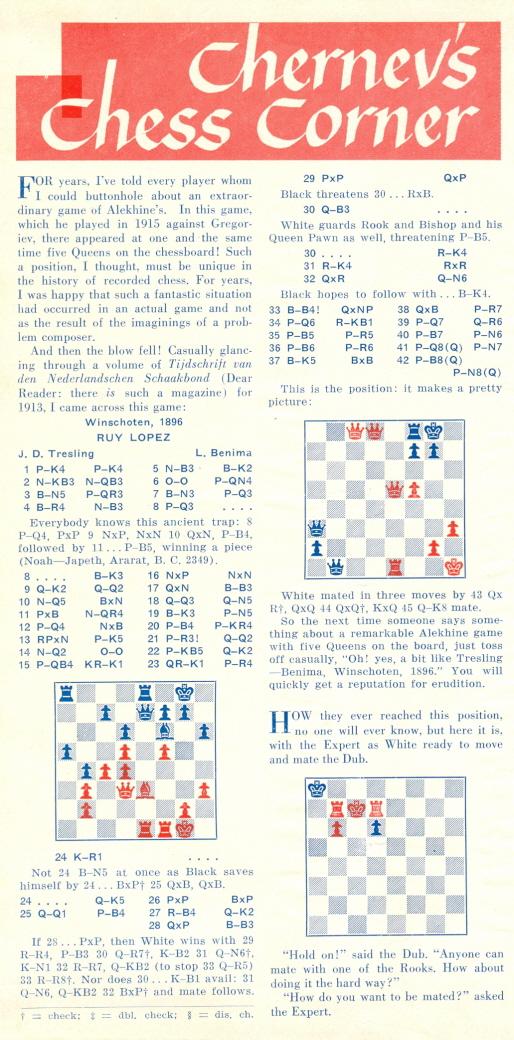

Tresling v Benima, Winschoten, 1896, a famous five-queens game, was given on pages 177-178 of The Chess Companion by Irving Chernev (New York, 1968). The item was reproduced from ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’ on the inside front cover of Chess Review, February 1950:

The game was also discussed in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 105 of the April 1962 BCM:

Can a reader send us copies of what was published in the nineteenth-century volumes of the Dutch magazine? For now, we can give only the game’s appearance on pages 172-173 of the July 1913 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

Below is Tresling’s obituary on page 115 of the April 1939 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

7108. Nimzowitsch circa 1916

We are grateful to Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) for permission to reproduce a photograph of Aron Nimzowitsch (circa 1916):

Mr Skjoldager informs us that he received the portrait from Mr Rolf Littorin. It appears on page 21 of the new chess catalogue of McFarland & Co. Inc., in connection with the forthcoming publication of Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen.

7109. The 1910 Lasker v Schlechter match

From page 29 of The Chess Scene by D. Levy and S. Reuben (London, 1974):

Corroboration provided by the co-authors for these

statements: zero. See also, for instance, page 127 of Grandmasters

of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and

New York, 1973).

The concluding paragraph of C.N. 3179 (see page 280 of

Chess Facts and Fables) may be recalled:

‘No chess event requires greater caution by historians than the Lasker v Schlechter match. As shown by magazine and newspaper reports of the time, the regulations evolved between late 1908 and early 1910, but, as far as we know, they were never published in a final, consolidated form.’

Anyone wishing to make a careful analysis of such

questions as whether Schlechter had to win the match by

two points and whether the world title was at stake

should evidently begin by studying existing accounts of

the controversy. We list below the main items that come

to mind, many of which cite material published in

1908-10.

- D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column in the BCM:

June 1974, page 206 (B. Cafferty);

October 1974, page 379 (J.M. Brown, E. Winter, R. Sinnott);

January 1975, page 26 (W. Heidenfeld);

April 1975, pages 162-163 (D. Brandreth);

August 1975, page 353 (W. Heidenfeld and E.A. Apps).

- A far more extensive discussion evolved in CHESS:

July 1975, pages 294-295 (W. Heidenfeld);

August 1975, pages 327-328 (D. Hooper, W. Heidenfeld);

September 1975, pages 357-358 (R.E. Gill, A. Penrose, W. Heidenfeld, H. Fraenkel);

November 1975, pages 48-49 (K. Whyld);

March 1976, pages 180-191 (E.A. Apps, W. Heidenfeld, C.D. Robinson, D. Hooper);

June 1976, pages 283-285 (E.A. Apps, H. Lyman);

September 1976, pages 380-381 (K. Whyld, W. Heidenfeld).

- Lasker v Schlechter: the last word by E.A. Apps (Sutton Coldfield, 1976). A four-page pamphlet whose text was similar, though not identical, to Apps’ article of the same title in the June 1976 CHESS.

- ‘Späte Nachlese zum Wettkampf Lasker gegen Schlechter’ by U. Grammel in Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1977, pages 37-41.

- Chess Notes: C.N.s 39, 81, 1308, 1762, 3179, 4144 and 5855.

- ‘The Lasker-Schlechter Match’ by L. Wright in The South African Chessplayer, November-December 1985, pages 135-140.

The South African Chessplayer, February 1986, page 26 (K. Whyld).

- ‘The Lasker-Schlechter Match: A New Look at the Published Evidence’ by L. Blair in Chess Horizons, November-December 1988, pages 52-62. A shorter version appeared on pages 48-55 of the February 1990 BCM.

- Carl Schlechter! Life and Times of the Austrian Chess Wizard by W. Goldman (Yorklyn, 1994), pages 428-452.

- New in Chess, 8/1994, page 59 (comments by H. Ree on Goldman’s book).

New in Chess, 1/1995, pages 5-6 (L. Blair);

New in Chess, 3/1995, pages 5-6 (D. Brandreth).

- ‘Lasker-Schlechter 1910 New Evidence from Viennese Sources’ by M. Ehn in New in Chess, 6/1995, pages 85-93.

New in Chess, 8/1995, pages 7-8 (L. Blair).

- ‘Lasker-Schlechter 1910 Neue Fakten aus Wiener Quellen’ by M. Ehn in Schach Report, 8/1995, pages 71-74 and 9/1995, pages 69-72.

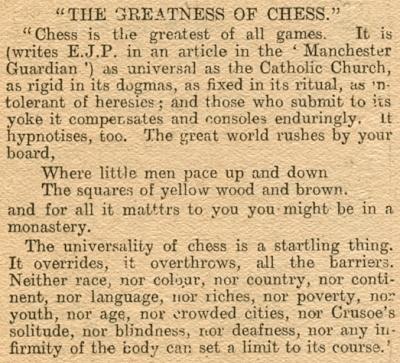

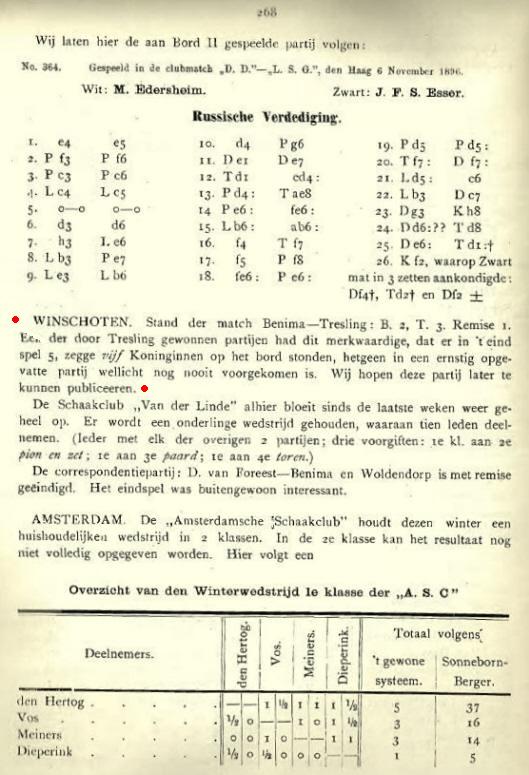

7110. The greatness of chess

What can be discovered about the author and exact original publication of the text below?

Chess Amateur, May

1920, page 222

American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1920, page 140.

7111. Tresling v Benima (C.N. 7107)

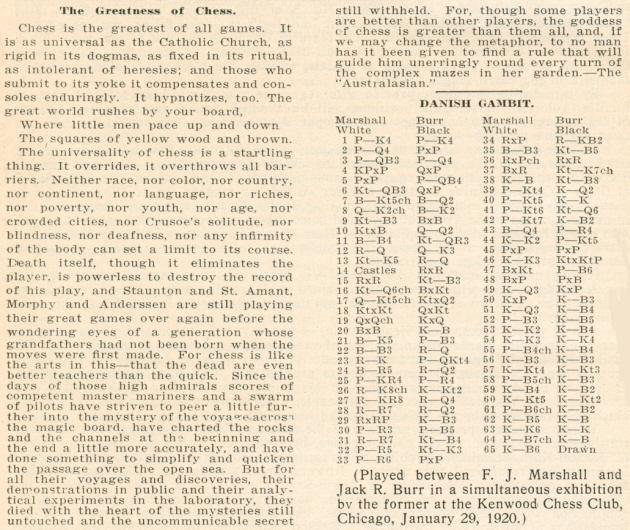

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) has supplied the items requested. Firstly, page 268 of the December 1896 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

Pages 110-112 of the May 1897 issue of the Dutch periodical:

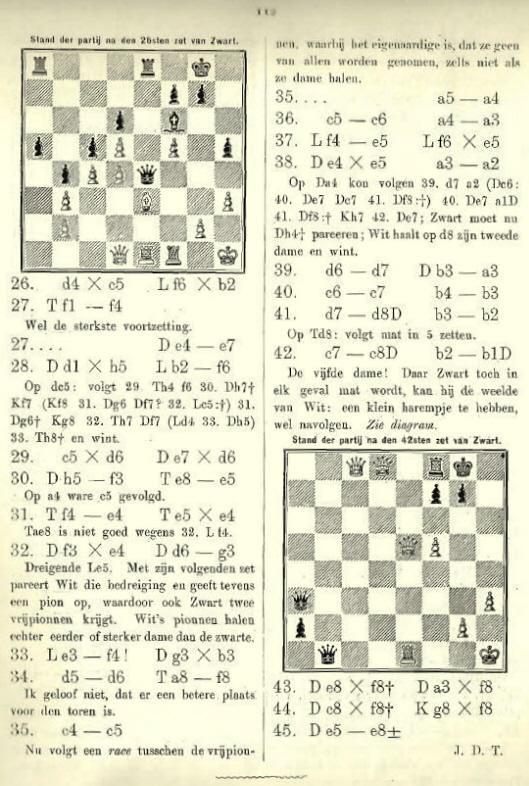

7112. Zukertort ‘world champion’

On page 16 of Comparative Chess (Philadelphia, 1932) Frank Marshall referred to Zukertort as ‘a former champion of the world’ (see page 297 of A Chess Omnibus).

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) draws attention to this passage on page 5 of the Sedalia Weekly Bazoo of 5 February 1884:

We note that the text quoted from the Southern Trade Gazette, which also referred to a 12-board blindfold exhibition by Zukertort in Louisville on 26 December 1883, ended as follows:

‘When Mr Lovenhart opened 1 P-KKt4 the doctor waited a full minute before he made his reply. A bystander suggested that Zukertort was not thinking of the game but merely trying to form a mental image of the man who would open a game in that manner.’

7113. Unidentified compositions

With the caption ‘White to play and win’ this position was on page 103 of Lasker’s Chess Primer (London, 1934):

(When the book was reissued as How To Play Chess the diagram was on page 100.) No composer was named by Lasker, and no solution was indicated. (It is mate in 11 moves.) However, thanks to Harold van der Heijden’s endgame study database the missing information is easily found: the composition was by Josef Hašek (published on page 10 of the January 1928 Deutsche Schachzeitung).

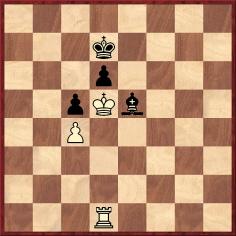

A more difficult case is ‘Task Eight’ in Lasker’s book (page 100 and page 96):

Again, there was nothing but a caption, which asked how the reader would win as White. Apart from the fact that a slightly similar position is on page 36 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932), all we can add is that the composition was discussed inconclusively in ‘Evans on Chess’ on page 25 of the January 1976 Chess Life & Review:

7114. Marshall letter to Blackburne

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) points out this letter on page 11 of the New York Evening Post, 5 October 1910:

‘My dear Blackburne,

I notice with a great deal of pleasure the movement which has been set on foot to commemorate the completion of 50 years of chess life in your career, and I want to add my personal good wishes to the many that will pour in upon you as the brilliant and much-loved representative of British chess. Your style of play, which to my mind should be cultivated much more than it is, has always appealed to me, and I believe I have profited much by a study of your famous games. Whether I have lost or won I have thoroughly enjoyed the games we have had together and both because of your standing in the chess world and my own regard for you I value as such the privilege of having met you so often face to face across the chequered board.

Regretting my inability to greet you personally on this auspicious occasion and hoping you may long survive in the interest of the cause you espoused and for the gratification of your man [sic], friends and admirers I remain yours very sincerely

(Signed) Frank J. Marshall

New York, 29 September.’

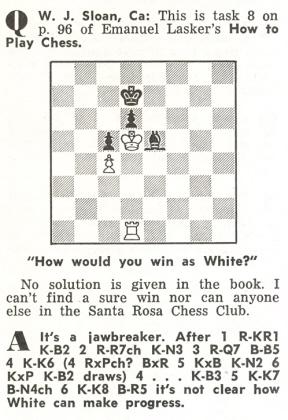

The result of the jubilee testimonial for Blackburne was announced on page 322 of the August 1912 BCM:

7115. ‘A New Morphy Game?’

At the Chess Archaeology website an intriguing article has just been posted: ‘A New Morphy Game? Found by Nick Pope, Introduced by John S. Hilbert.’

7116. Stalemate and deadlock

From page 2 of the October 1915 Chess Amateur:

‘Not Stalemate but Deadlock in describing the War

Many newspapers, magazines, journals and books have, on various occasions, alluded to the situation in the Dardanelles and in France as that of a “stalemate”, painfully illustrating the truth of the adage how dangerous a thing is a little knowledge. No-one with any real familiarity with chess would use the expression stalemate in describing the war in either of its areas, which would convey the idea that it was all over and a draw had resulted. A deadlock perhaps at one time would have been a correct definition, but a stalemate is a climax, a finality, and is absolutely misleading. The Germans in this awful contest would jump at a stalemate, but their opponents have got some good “moves” to spring upon them at the psychical moment, when the Kaiser will be effectually checkmated – a totally different matter to being stalemated.’

7117. Time and Space

William Winter

This caricature comes from page 193 of the 14 January 1939 CHESS, which reproduced it in a review of Time and Space, the ‘official organ of the Workers’ Chess League’ and ‘a bright new chess magazine with pronouncedly Left tendencies’. William Winter was named as ‘the editor and author of much of the matter’, although the entry in Betts’ Annotated Bibliography names the editor as E. Klein, also stating that the magazine ran for 23 issues, from August 1938 to June 1940.

Having no copies of Time and Space, we should be grateful to hear of any particularly interesting material it may contain.

7118. St Petersburg, 1914

What exactly is known about the rapid transit event held on the occasion of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament?

From page 158 of the July 1914 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Although the chief prize at St Petersburg eluded him by the narrowest of margins, José R. Capablanca, besides taking the second prize, did not come away empty-handed with regard to minor honors, which included the first Rothschild prize for brilliancy, first prize in a rapid transit tourney, in which Dr Lasker was also a participant, as well as a fine record in simultaneous exhibitions, of which he gave three. ...

In the rapid transit tourney Capablanca had the satisfaction of making a score of 5½ out of a possible 6 points, with Dr Lasker, Dr Tarrasch and Alekhine among the competitors. It is not the first time, however, that he has worsted the world’s champion in this style of chess.’

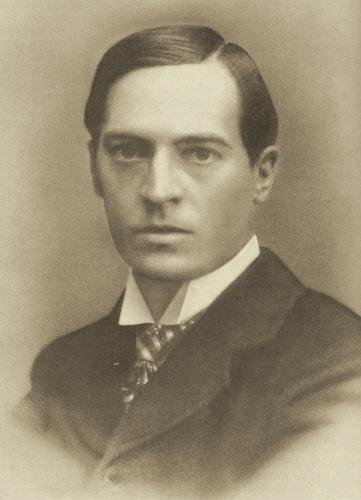

7119. Mackenzie ‘chess champion of the world’

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) sends an article from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News which was published on page 20 of the New Zealand Chess Chronicle, 25 October 1887. The first paragraph:

The writer was G.A. MacDonnell, and the article was included on pages 27-30 of his book The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894):

See also C.N. 3968. Steinitz took up the ‘chess champion of the world’ affair in the International Chess Magazine, starting on page 264 of the September 1887 issue, and there resulted a number of public exchanges with Mackenzie.

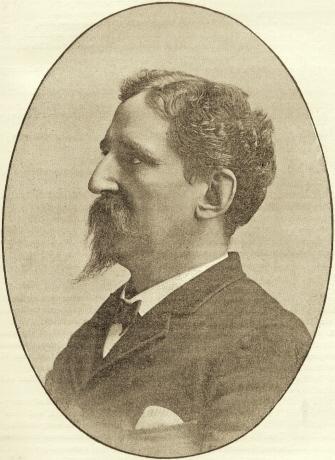

Below is a portrait of Mackenzie from page 33 of the October 1888 Chess Monthly:

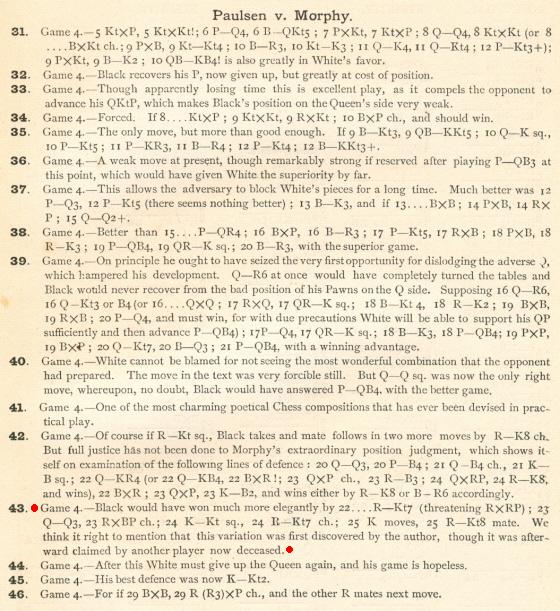

7120. Paulsen v Morphy

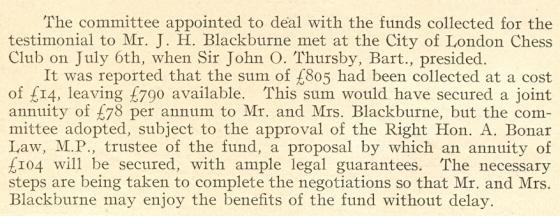

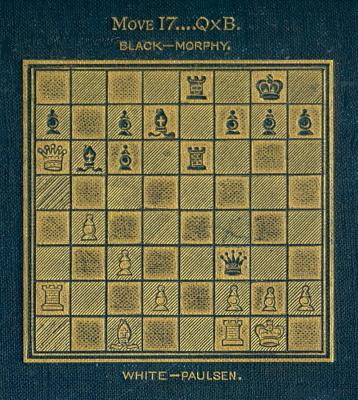

Front cover of The Modern Chess Instructor by W. Steinitz

As is well known, though not always mentioned by annotators, in his famous win against Louis Paulsen at New York, 1857 Morphy overlooked quicker mates at moves 22 (...Rg2), 23 (...Be4+) and 24 (...Bg2+). The second and third of these are, of course, the same mating line.

It is worth recalling the discussion in such popular books as Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (pages 120-122) and The Chess Companion (pages 231-233). In the latter work the discovery of 22...Rg2 was credited to Zukertort, and it was stated that 23...Be4+ was ‘pointed out by Bauer’. Many other books say the same. On the other hand, page 71 of Morphy Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld and A. Soltis (New York, 1974) referred to 22...Rg2 as ‘the beautiful four-move win discovered by Steinitz’. (The annotations were by Reinfeld, having previously appeared on page 327 of the November 1954 Chess Review.)

So, was it Zukertort or Steinitz who first pointed out 22...Rg2, and where exactly did Bauer comment on the game?

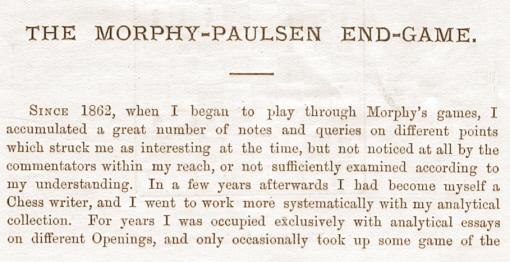

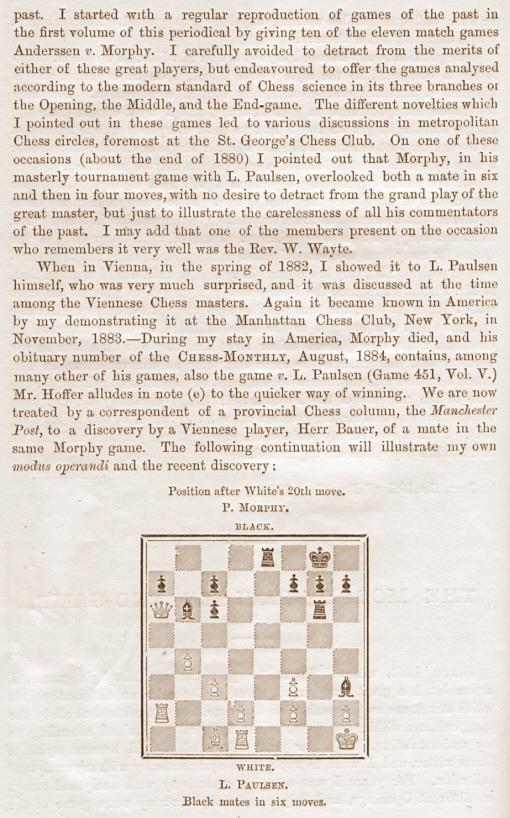

On pages 171-173 of the February 1887 Chess Monthly an article by Zukertort was published under the title ‘The Morphy-Paulsen End-Game’:

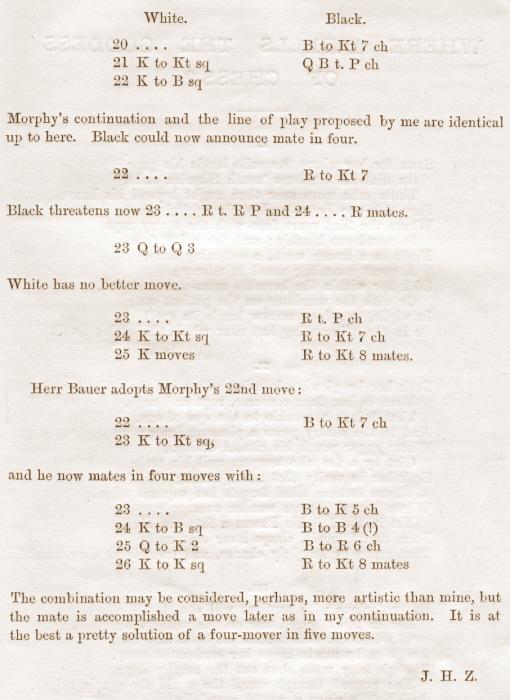

Steinitz, for his part, gave the game on pages 48 and 51 of part one of The Modern Chess Instructor (New York, 1889). Without offering details he asserted that it was he who had ‘first discovered’ 22...Rg2 (‘though it was afterward claimed by another player now deceased’). Steinitz made no mention of Bauer’s 23...Be4+:

What was the exact chronology of the analytical findings by Steinitz, Zukertort and Bauer in the Paulsen v Morphy game?

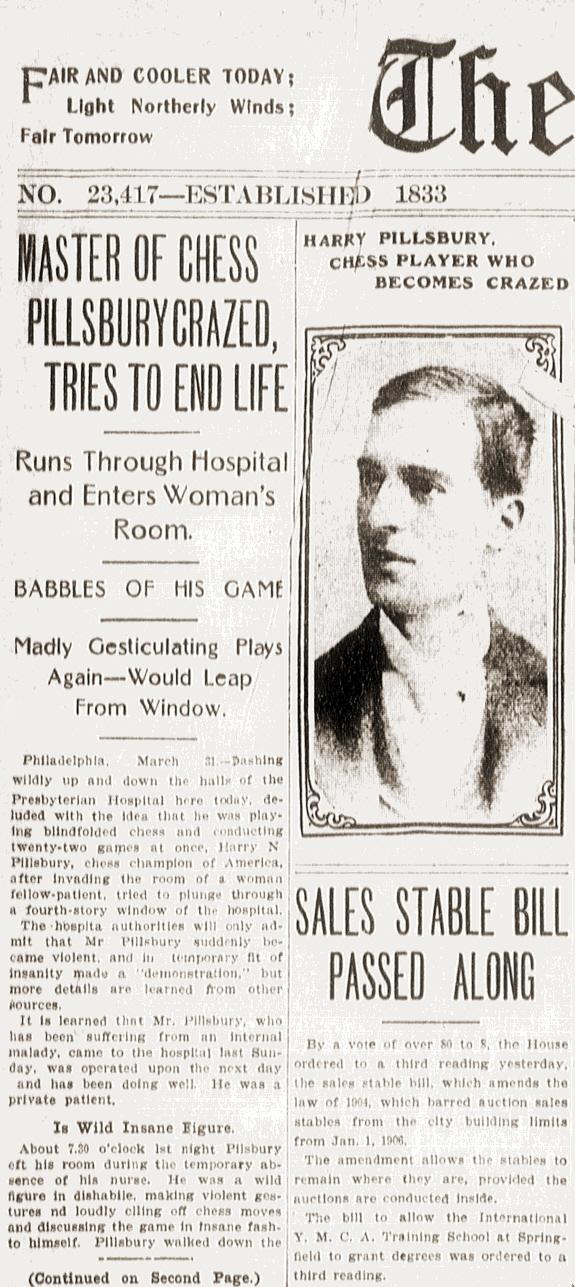

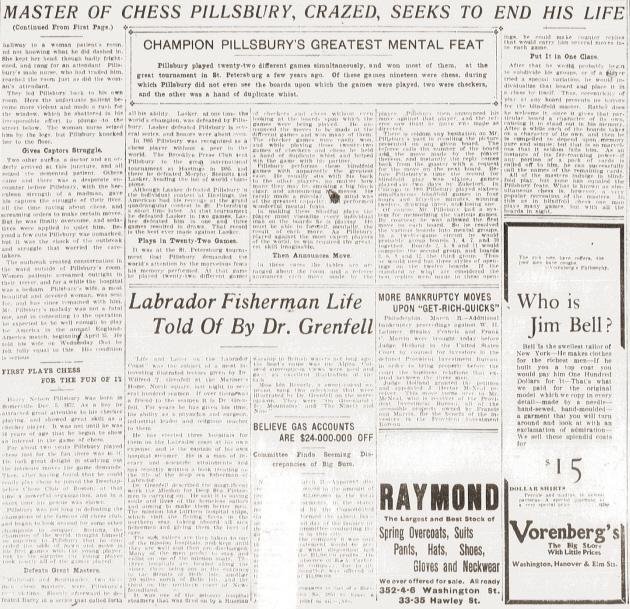

7121. Pillsbury in 1905

Further to the feature article Pillsbury’s Torment, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to a report on pages 1 and 2 of the Boston Journal of 1 April 1905:

7122. ‘Chess is what you see’

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

How far back is it possible to trace the quote attributed to Pillsbury ‘Chess is what you see’? The following comes from page 479 of the January 1898 American Chess Magazine:

7123. Englisch v Tarrasch

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) enquires whether the game-score of Englisch v Tarrasch, Frankfurt am Main, 1887 has been lost.

We have never seen the game. Played on the morning of 22 July, it is absent from the tournament book.

7124. Bruno Bassi

In C.N. 732 Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, PA, USA) wrote:

‘What became of the Bruno Bassi collection? The magazines are in a library in Sweden, but what became of archival material and indexes he cited in his letter in the July 1950 BCM, page 231, where he also mentioned his unpublished Dictionary of Chess History and Biography (what a loss that that work has apparently never surfaced)?’

Gaige was writing in 1984, and we recall no further particulars about the Bassi collection. Below is the BCM letter:

7125. Middleton Counter-Gambit (C.N.s 4792, 4860 & 4864)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nh2 g3 9 Ng4 Nf6 10 Nc3 Rh4 11 Ne3 fxe3 12 dxe3 g4 13 Qd4 Bg7 14 e5 Nc6 15 Qf4 Nxe5 16 Qxg3 Nh5 17 Qf2 Nf3+ 18 gxf3 g3 19 Qd2 Rh2 20 Qd5 Rh1+ 21 Kg2

21...Nf4+ 22 exf4 Rh2+ 23 Kg1 Bd4+ 24 Qxd4 Qh4 25 White resigns.

This game comes from page 327 of the August 1916 Chess Amateur. Concerning the occasion, the only information provided is that the players were ‘Mac R.’ and ‘Hart’. The magazine’s source was the Boletín de Ajedrez (Mexico).

7126. ‘Chess is what you see’ (C.N. 7122)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) sends this report from page 2 of the Ogden Standard Examiner, 16 December 1897:

7127. Bruno Bassi (C.N. 7124)

From Bo Sjögren (Märsta, Sweden):

‘The Bassi collection (or, rather, what is left of it) is indeed in a Swedish library, the Royal Library (“Kungliga biblioteket”, KB). A brief description is available on-line.

The description does not mention an archive or an index, but it is there; for some time it was included by mistake in the Frans G. Bengtsson collection, but I understand that this has now been corrected.

As the link above mentions, there was an article about Bassi and his collection on pages 50-52 of the 2/1957 issue of Tidskrift för Schack. The archive is mentioned in very positive terms (my translation):

“In addition to this large book collection, Dr Bassi has also compiled an opening and historical card index consisting of 40,000 written cards. This chess archive has been systematized using a simple but brilliant method, invented by him, and which, despite the enormous amount of material, makes everything easily accessible.”’

7128. Thomas on Lasker and Capablanca

C.N. 761 quoted a remark by Sir George Thomas on page 242 of the September 1951 BCM:

‘... It is my firm conviction that either Lasker or Capablanca at his best, and with no more modern equipment than he possessed at that time, could have given the odds of the latest technique to any player of today.’

7129. Skulduggery (C.N. 4386)

From page 308 of the July 1920 Chess Amateur:

After correction of a couple of obvious errors in the Forsyth notation the position, it will be noted, is the same as the one given on page 25 of the 19 December 1908 issue of the Chess Weekly (which did not mention Harrwitz).

7130. Middleton Counter-Gambit (C.N.s 4792, 4860, 4864 & 7125)

Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia) has found this game between R.A. Hart and C.C. Lee on page 3 of the Sunday Times (Perth, Western Australia), 15 February 1903: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nd4 Qf6 9 c3 Nd7 10 Qxg4 Ne5 11 Qe2 g4 12 d3 g3 13 Bxf7+ Qxf7 14 Rxf4, after which the newspaper stated that (according to its source, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle) Black now gave mate in 12.

We have traced the game on page 21 of the 30 November 1902 edition of the Eagle. The heading reported that it was ‘played by correspondence between R.A. Hart of Baton Rouge, La and C.C. Lee of Boston, Mass., in the Middleton counter gambit tournament’.

7131.

Photographs

from the Bibliothèque nationale de France

In C.N. 5875 Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provided a link to a photograph of Chigorin at the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. He now points out three further pictures from the same collection:

- Paris, 1925: Colle v Alekhine after 10...Bxc3+.

On Alekhine’s left is Tartakower, whose opponent that day (11 February) was Znosko-Borovsky. The man standing between Tartakower and Znosko-Borovsky is the tournament director, Alphonse Goetz. Mr Urcan comments that by zooming in it is even possible to read the time on Alekhine’s watch.

- Two shots of Tartakower giving a simultaneous exhibition in 1932.

7132. Quiz questions

This position was published on the front cover of a book. Which move did White play and what was the title of the book?

| First column | << previous | Archives [83] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.