Edward Winter

A paragraph from Clive James’ television column in The Observer, 11 October 1981, page 48:

‘Why have there been so few important female chessplayers? Arguments about social repression have never satisfactorily answered the question. The Freudian view, summed up in a classic paper by Ernest Jones, is that the game represents a man’s oedipal attempt to kill his father, but a simpler view would suggest that women just aren’t nuts enough. The World Chess Championships (BBC 2) are a case, or perhaps two cases, in point. Korchnoi is fairly obviously some sort of weirdo. We have not forgotten the poisoned yoghurt [sic] and the enemy thought-waves. But Karpov, if you look closely, is even weirder. With Korchnoi some of the obsessiveness remains unfocused and spills out in the form of dingbat behaviour, as it did with Bobby Fischer. But with Karpov it is all beamed straight at the chess-board. Get between him and it and you’ll fry.’

Clive James

(16 & 4117)

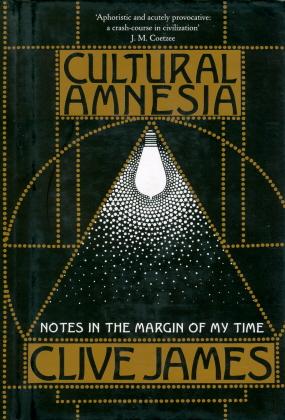

Page 264 of Cultural Amnesia by Clive James (London, 2007) discusses, with examples, the prose style of Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

‘His aim might have been compression and economy, but the compression was a contortion and the economy was false. In a single sentence, two separated adjectival constructions often served the one noun, or two separated verbs the one object, or two separated adverbs the one verb, and so on through the whole range of parts of speech: it was a kind of compulsive chess move in which a knight was always positioned to govern two pieces, except that the two pieces governed it.’

(5315)

In a feature in the Daily Telegraph of 22 June 2012 entitled ‘Clive James: 30 classic quotes’ the penultimate entry is:

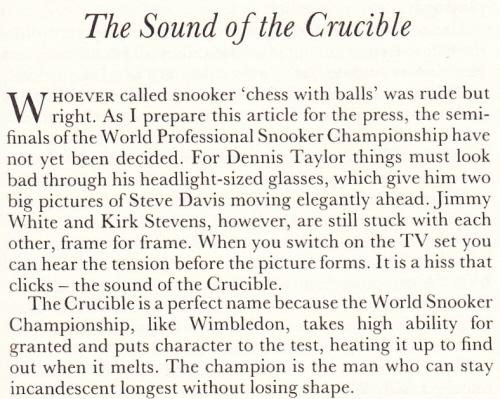

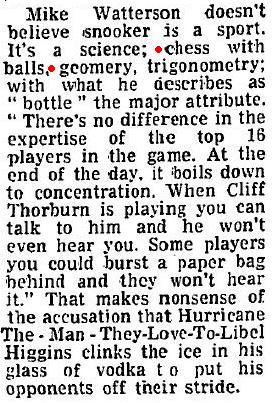

‘Whoever called snooker “chess with balls” was rude but right.’

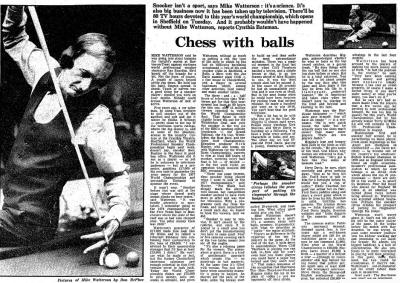

The remark is frequently cited on websites but not, from our reading, with any source specified. We therefore point out that it was the first sentence of an article about snooker, ‘The Sound of the Crucible’ on pages 285-288 of James’ book Snakecharmers in Texas (London, 1988 and 1989). The article was reproduced from page 8 of The Observer of 6 May 1984, although the newspaper did not include the first four sentences.

Clive James’ remarks on chess have been mentioned in C.N.s 16, 4117 and 5315, and here we add a further one, from his television review column on pages 26-27 of The Listener, 6 July 1972:

‘Frank Muir and Groucho Marx unforgivably clashed with Spassky and Bobby Fischer on the two BBC channels. Button-punching only resulted in Frank Muir asking Bobby Fischer questions about his film career. There was nothing for it but to go to bed with a book of end-games and dream through a long night in Capablanca. Groucho threatens White Queen, played by Margaret Dumont.’

Information about the chess programme is given in Section 4 of our feature article on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match.

Another inscribed item in our collection:

(7699)

A remark which we jotted down at the time from Clive James’ television column in The Observer, 9 July 1978, page 23:

‘The chief characteristic of people without a sense of humour is that they will laugh at anything.’

(8069)

C.N. 8274 reported that the observation about snooker and chess was attributed to Mike Watterson in an article by Cynthia Bateman entitled ‘Chess with balls’ on page 16 of the Guardian, 3 April 1981:

A paragraph about the 1972 Spassky v Fischer world championship match is on page 210 of Clive James’ book Fame in the 20th Century (London, 1993).

Some further quotes from his television column in The Observer:

Source: The Observer (Review section), 13 November 1977, page 31.

‘The complexity of the game was matched by the complexity of its television coverage. Cameras were everywhere. The commentary was deeply informed and highly statistical. “John, this reminds me of the fake punt Stanford ran in 1957 ...” Or it could have been 1857: my notes are a scrawl. Action replays and freeze frames helped demonstrate that every flurry of action was an intricate plan either working itself out or else being countered with similar intricacy. The whole affair, appealing as it did with equal force to the aggressive instincts and the intellect, rated with the Karpov-Miles chess final in Master Game (BBC 2) as an answer to the pressing demand for a moral equivalent of war.’

Source: The Observer (Review section), 15 January 1978, page 31.

Source: The Observer (Review section), 22 June 1980, page 48.

On the subject of fame (in the context of a beauty contest) Clive James wrote on page 40 of The Observer, 31 August 1980:

‘... people are not to be despised just because their dreams are cheap.’

The column was reproduced on pages 111-114 of the third anthology of his Observer television criticism, Glued to the Box (London, 1983).

President Josiah Bartlet (Martin Sheen) in an episode of The West Wing (C.N. 6129)

From pages 70-71 of Play All by Clive James (New Haven and London, 2016):

‘In The West Wing the purity of language is unreal: network rules prevail and we never hear a dirty word. Nor does anyone, not even a writer, ever really talk that well. But there is realism about the way reasoned conclusions are reached.

In that regard, the most advanced stroke of realism in the show is the way that not even the brilliant Bartlet can function without hearing other voices. Those of us who hanker for a father figure should remember that if he existed then he would need a father figure too. Though Bartlet is a mighty chess player, The West Wing is a pretty good shot at fighting off the romanticism by which the central guru can understand the whole board at a glance. In I, Claudius Augustus sometimes didn’t know what was really going on, but he didn’t know that he didn’t know. Bartlet incarnates Camus’s definition of democracy as the system built and maintained by those who know that they don’t know everything.’

Chess references in The West Wing are discussed in Chess and Television.

Below from our collection is a photograph signed by cast members of The West Wing in 2002:

Left to right: Allison Janney, Richard Schiff, John Spencer, Martin Sheen, Rob Lowe, Dulé Hill and Bradley Whitford.

(10168)

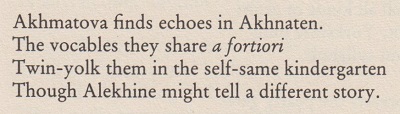

From page 55 of Other Passports by Clive James (London, 1986):

The full poem, a parody entitled ‘Richard Wilbur’s Fabergé Egg Factory’, can be read on Clive James’s website.

(10184)

From Clive James’ television column in The Observer, 28 June 1981, page 44, concerning John McEnroe at Wimbledon:

The full article is available on-line.

A remark by Clive James on page 20 of his Introduction to From the Land of Shadows (London, 1982):

‘The necessary conceit of the essayist must be that in writing down what is obvious to him he is not wasting his reader’s time. The value of what he does will depend on the quality of his perception, not on the length of his manuscript. Too many dull books about literature would have been tolerable long essays; too many dull long essays would have been reasonably interesting short ones; too many short essays should have been letters to the editor.’

Such sentiments could readily be expanded to include today’s communication means, where wasting the reader’s time is an infrequent concern.

(10246)

The recent death of two men of formidable intellect, Clive James and Jonathan Miller, prompts a few ruminations. Whether Miller had any particular interest in chess is unclear, but the prevalence of ineffectual criticism in the chess world and the dearth of rigorous interviewing (as mentioned in, for instance, Child of Change and Chess Thoughts) bring to mind a clever, documented remark of Miller’s which has been quoted in several of his obituaries:

‘Bernard Levin came down on me like an ounce of bricks.’

Concerning Clive James, all available chess references by him are in our feature article, but a general remark is worth pondering:

‘Writing is essentially a matter of saying things in the right order.’

That comes from page 159 of Unreliable Memoirs (London, 1980), in a description of his employment at the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1960s:

A regular theme in Clive James’ output is that many writers, including ‘professionals’, are unfit for the task. C.N. 1079 (see Chess and the English Language) cited this description of editing work from page 33 of his follow-up volume of autobiography, Falling Towards England (London, 1985):

‘... sorting out tenses, expunging solecisms and re-allocating misplaced clauses to the stump from which they had been torn loose by the sort of non-writing writer for whom grammar is not even a mystery, merely an irrelevance.’

As regards content, it is, of course, vital to gauge accurately what readers do, and do not, need to be told, with matters seen from their standpoint. Poor writers often include information which is self-evident (or, at least, traceable via a quick Google search) while omitting information which is essential and requires elucidation by them. There should be no spoon-feeding of readers but also no off-loading of verification work onto them, or leaving them to guess what may or may not be true. With such basics accomplished, the writer’s skill comes into play at the next stage: attempting to produce prose whose flow is not impeded by the corroborative details.

Some writers have the peculiar habit of snippet-dangling, and the reference to Sydney in the above passage from Unreliable Memoirs indirectly reminds us of a small example: on page 1 of The United States Chess Championship, 1845-1996 by A. Soltis and G.H. McCormick (Jefferson, 1997) an aromatic morsel is waggled fleetingly under the reader’s nose. In a cursory list of some American chess masters’ professions, Sidney Bernstein is described as ‘a movie censor’. Nostrils atwitch, the reader hopes for some hard facts, but the book has already moved on to calling Jackson Showalter a cattle rancher. To rewind, though, what exactly is known about the assertion that Sidney Bernstein was a film censor? Where and when? Working for whom? In peacetime or in wartime, or both? Censoring what kind of films? What reliable source do the co-authors have for their tiny, if tantalizing, nibble?

When nothing is explained, everything and anything can be imagined; even, for instance, that – and stranger things have happened in chess literature – there has been a mix-up over, say, Sydney Sharp or Jacob Bernstein. Only with the rewarding discipline of real sourcing can the writer aspire to real clarity and real precision, and that is what readers deserve.

(11583)

Two general remarks about history in Cultural Amnesia by Clive James (London, 2007):

Chess Journalism and Ethics notes that when reviewing ‘Rumpole and the Fascist Beast’ (Rumpole of the Bailey) on page 20 of The Observer (Review section), 24 June 1979 Clive James wrote:

‘In the latest episode of his adventures, Rumpole defended a home-grown racist fanatic and got him acquitted. The message was that freedom of speech is a right which means nothing if it is not extended to those who abuse it.’

The column was reproduced on pages 193-196 of Clive James’ book The Crystal Bucket (London, 1981).

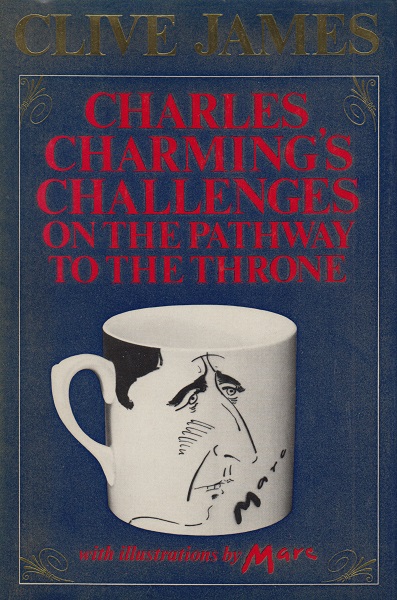

As mentioned at the end of our article on inscribed books, we are able to supply a number of volumes (essays, fiction, autobiographical works and anthologies of his poetry) signed by Clive James. They include one of his most publicized works, an epic poem in rhyming couplets which was also a stage show: Charles Charming’s Challenges on the Pathway to the Throne (London, 1981):

From the dust-jacket:

‘Charles Charming’s Challenges is a tribute to a young man who was conscripted and yet trained himself to be a volunteer – the Prisoner in the Velvet Mask.’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.