Edward Winter

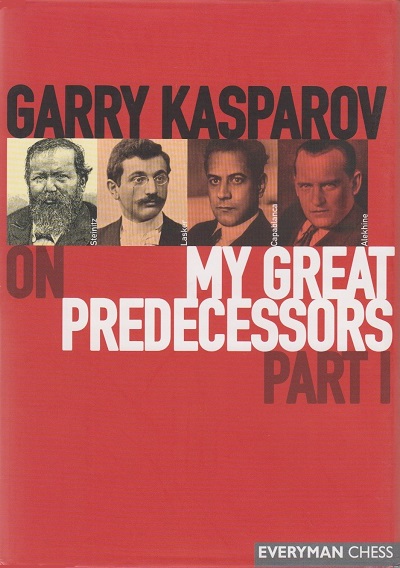

Well before Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part I was put on sale by Everyman Chess the rush had started to eulogize Kasparov’s ‘masterpiece’, to quote the term used on page 51 of the May 2003 CHESS. On page 92 of the 4/2003 New in Chess the volume was described as ‘fantastic’ by that paragon of literary criticism and historical scholarship, Matthew Sadler. Having just spent a morning dipping into the book, we offer some random jottings on, mainly, historical and editorial points.

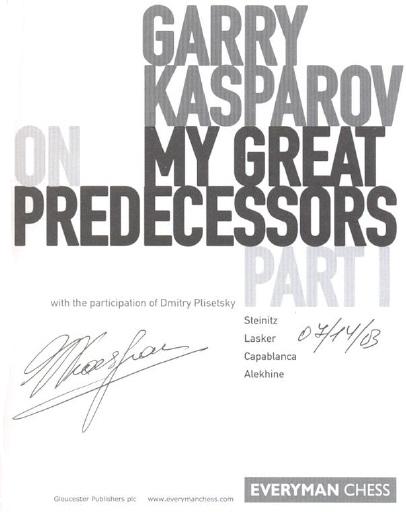

Although the book’s title page carries the words ‘with the participation of Dmitry Plisetsky’, the various textual ingredients have clearly gone through many pairs of hands on their way to the serving table. The present article falls in with the front cover’s illusion that the author/masterchef was Kasparov alone. It would, at least, seem that the Introduction (dated April 2003) was penned by him. From those egregious six pages we learn that Euwe was ‘a symbol of the age of scientific and technological revolution, the start of the era of atomic energy and the computer’, while Smyslov was ‘undoubtedly a symbol of the early thaw, the comparatively libertarian era’. Kasparov is in danger of becoming a symbol of hot air.

The absence of, even, a basic bibliography is shocking in a work which claims to be ‘Garry Kasparov’s long-awaited definitive history of the World Chess Championship’, and a lackadaisical attitude to basic academic standards and historical facts pervades the book. On page 264 Kasparov writes about the 1921 world championship match conditions: ‘for the first time to the best of 24 games (later Botvinnik liked this rule and it became a standard one during the second half of the twentieth century)’. In fact, rule one of the 1921 match conditions (see page 39 of Capablanca’s book on the event) specified that the winner would be the first who won eight games; the 24-game limit would be applied only if neither player had achieved eight wins.

On page 374 Kasparov states that in late 1923 Alekhine ‘set off on a tour of South America; it was time to announce himself on the “enemy” continent’. In reality, during that period Alekhine toured Canada and the United States.

Regarding the 1927 world championship match we read on page 391:

‘The score became 3-2 in favour of the challenger. In Buenos Aires something unbelievable was happening! At the time the story went round the city, that a dumb person, a fervent Capablanca supporter, on hearing about the result of the 12th game, exclaimed: “It’s not possible!” – and in his grief he again lost the power of speech …

It was indeed an unprecedented occurrence: Capablanca had lost two games in a row!’

Leaving aside the unworthy anecdote and mangled punctuation, we would merely point out that the Cuban had also lost two consecutive games (against Lasker and Tarrasch) at St Petersburg, 1914.

Historical matters are even asserted confidently when the principals have stated something quite different. Kasparov’s claim (on page 43) that an 1883 meeting between Steinitz and Morphy was at the latter’s home, as opposed to merely in the street, is contradicted by Steinitz’s own account in the New York Tribune of 22 March 1883 (see page 309 of David Lawson’s book on Morphy). Kasparov is also under the misapprehension that there was only one meeting between Steinitz and Morphy (if any at all – given that he uses the phrase ‘Legend has it that …’). A similar case concerns Olga Capablanca’s own statement (which we made public some years ago) that she was outside Mount Sinai Hospital when her husband died. On page 339 Kasparov invents the Nice Story that Capa died ‘in the arms of his wife Olga’. The book is also wrong (page 331) to claim that she was already his wife in 1936. The famous ‘I never won against a healthy player’ quip has been attributed to many old-timers (most notably Burn) and is documented from, at least, 1949 onwards (see pages 322-323 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves); it says little for Kasparov’s knowledge of chess lore that page 292 of his book calls it ‘a witty remark by Larsen’. [Subsequently, C.N. 4189 quoted a 1936 attribution of the comment to Bird.]

A stew-pot which has evidently involved a number of cooks (we nearly wrote scullions) results in the lack of a clear authorial voice. It is impossible to know who has cooked, or poached, what. Quotes bombard the reader out of the blue (without, in most cases, even the approximate year of origin, as a guide to the reader). We are asked to make do with being told that X said, or wrote, Y at some unspecified time simply because a self-proclaimed ‘definitive’ book tells us so. That may suffice for Matthew Sadler but is unlikely to appeal to those who care about decent standards of historical truth and accuracy.

The lack of sources has itself hampered textual precision and translation. Even famous passages have been unnecessarily translated and re-translated. Thus page 137 quotes Capablanca as stating: ‘Pillsbury staggered everyone with the strength and subtlety of his brilliant play.’ It would not have been difficult to print his actual words, i.e. from Chapter I of My Chess Career: [Pillsbury] ‘left everybody astounded at his enormous capacity and genius’. Page 456 has the well-known description by Capablanca of Alekhine in the New York Times (1927), but for some reason the original English has not been used. Thus where Capablanca wrote that Alekhine ‘possesses a degree of culture considerably above that of the average man’, Kasparov’s book renders the remark as ‘his general maturity is significantly higher than the level of the average person’.

An analogous case is the celebrated Tarrasch dictum, ‘Chess, like love, like music, has the power to make men happy’. That was the English-language translation at the end of the Preface to The Game of Chess, published in 1935, the year after his death. (The German edition of the book, Das Schachspiel, had appeared in 1931.) Pages 157-158 of Kasparov’s book offer a different English version which is, moreover, anachronistically dragged into a piece of speculation in the notes to a Tarrasch game played back in 1914: ‘Here the Doctor no doubt remembered one of his immortal aphorisms “Chess, like love and music, has the ability to make man happy”.’ Such an annotation defies logical analysis.

With this carefree approach to the public record, the book frequently creates its own confusion. Page 239, for instance, has Alekhine’s well-known tribute to Capablanca (from pages 105-106 of the April 1956 BCM, although that is naturally not specified) in which he wrote as follows regarding the Cuban’s prowess in 1914: ‘Enough to say that he gave all the St Petersburg masters the odds of 5-1 in quick games – and won!’ In Kasparov’s book the quotation comes in an alternative version: ‘In blitz games he gave all the St Petersburg players odds of five minutes [emphasis added here] to one – and he won’. Why? Since no source of any kind is given, it is impossible for the reader to know. On the subject of information contained in quotations, we also wonder about the identity of the ‘Saburov’ who is described on page 349 as ‘elderly’. (P.P. Saburov was aged 34 at the time, i.e. in 1914.) Nor is it clear to us why page 364 refers to London, 1922 as the ‘victory tournament’. That is the customary title of Hastings, 1919.

An early example of language/translation problems occurs on page 14, with the assertion that Labourdonnais wrote a manual entitled ‘New treatise on the game of chess’. In fact, that was a book by George Walker, whereas Labourdonnais wrote Nouveau traité du jeu des échecs. The bottom of page 356 says that Alekhine’s first book was ‘Shakhmatnaya zhinzn [sic] v Sovetskoi Rossii (Chess Life in Soviet Russia)’. As indicated in our bibliography of books by Alekhine (C.N. 1709), he wrote no volumes in Russian, and his first work was in German (Das Schachleben in Sowjet-Russland).

Proof-reading and fact-checking in Kasparov’s book fall far short of what may reasonably be expected, especially in a high-profile work. That same page 356 states that Alekhine ‘would never seen [sic] his native land again’. Page 428 says that he ‘set off an a’ round-the-world-trip. Page 456 refers to his burial in ‘Montparnesse’ Cemetery. The reference to ‘his’ instead of ‘this’ match of giants on page 312 is another misprint noted during our morning’s casual browsing.

The quality of the prose is erratic, with an unfortunate penchant for Reverse English in the annotations (e.g. ‘Undoubtedly more tenacious was 27…Ne5’ on page 292). The whiff of foreign cuisine is strong, and the book could certainly have done with an English grammarian. A curious case arises on page 229, with an apparent attempt to correct Capablanca’s English from My Chess Career. The Cuban’s first note to the final game of the Marshall match included the sentence ‘I liked Mieses’ ninth move, Kt-K5, and decided to play it against Marshall, who I hoped had not seen the games’. This is perfectly correct, but somebody involved in Kasparov’s book has presumed to change ‘who’ to ‘whom’. It may well be the same person who, on page 349, came up with the following: ‘The military authorities quickly sorted out who was whom.’ And, indeed, the same individual who wrote on page 413 ‘Alekhine will defeat everyone who he meets’.

Of the 148 games it is unlikely that a single one will be new to readers, so what counts is the quality of the annotations. Here the same laxity in quoting proper sources is manifest, with woefully insufficient account taken of earlier analysts’ work. Pages 37-39 discuss Bird v Morphy, London, 1858, but Kasparov and his helpers have paid no attention to the detailed notes of Karpov and his helpers on pages 1-10 of Miniatures from the World Champions (London, 1985). Page 64 (Zukertort v Blackburne, London, 1883) disregards the forced mate beginning with 31 Rg8+ (C.N. 2193 – see page 5 of A Chess Omnibus). Page 326 fails to credit any contemporary analyst with noting 40 Rb6 in a game from the 1927 world championship match. C.N. 2343 (see page 36 of A Chess Omnibus) pointed out that the move had been put forward by Roberto Grau on page 212 of the April 1928 issue of El Ajedrez Americano.

Frequently Kasparov claims to have found a new move that nobody has noticed before, and there can be little doubt that in many, or even most, cases he is correct. Unfortunately, though, such instances are mixed up with sweeping generalizations which do not withstand a few moments’ scrutiny. For instance, on page 383 the move 32 Nf6+, also from the 1927 title match, is described as ‘a check that was condemned by all the commentators’, which is demonstrably false. So is this further statement by Kasparov at move 37 of the same game: ‘Following Alekhine’s example, everyone attaches an exclamation mark to this time-trouble move.’

Anyone flicking through the book may initially be impressed by the quantity of analysis, and the extensive references to other annotators, but the devil is in the detail. The edifice begins to crumble as soon as a closer inspection is made. We would be tempted to write more, but fortunately one critic, Richard Forster, has already made a detailed study of the Kasparov approach to annotation. The result was a notable article entitled ‘The Critical Eye’ at the Chess History Center website.

Anyone who is contemplating praising Kasparov’s book would do well to note that among the conclusions of that feature, which deals extensively with one sample game allocated four and a half pages by Kasparov, is the following observation:

‘A very great part of the analysis (certainly more than 95%) has been copied from earlier sources, mostly without proper acknowledgement.’

Afterword: The above assessment appeared as C.N. 2972. Together with the follow-up items C.N.s 3027 and 3180, it was subsequently published on pages 237-241 of Chess Facts and Fables.

Robert Hübner’s unmissable (not to say devastating) review of the first volume of Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors was published in the 11/2003 and 12/2003 issues of Schach (pages 24-35 and pages 34-48 respectively). On page 40 of the latter he discussed this position after White’s 48th move in the final game of the Lasker v Schlechter match (i.e. with respect to pages 185-186 of the English edition of Kasparov’s book):

‘There followed 48…Qc1+ 49 Kb3 Bg7 50 Ne6 Qb2+, etc.

In the book under discussion, however, 48…Qf2+ is given as the move played, and after 49 Kb3 Bg7 50 Ne6 Qb2+ it is stated:

“Another mistake that was not pointed out by anyone! 50…Qb6+! was essential, driving the king back to the kingside: 51 Kc2 Qb2+ 52 Kd1 Qa1+ 53 Ke2 Qb2+ 54 Kf3 (…) Qf6+ 55 Nf4 Nf7. Of course, White will play for a win, but with such a king it is doubtful whether such a result can be achieved.”

Yet it is not so astonishing that nobody has pointed out this continuation, for a queen move from c1 to b6 was against the rules of the game at the time.

Incidentally, the entire variation [i.e. up to 55 Nf4 Nf7] was given as an annotation to 48…Qc1+ in Schach, 10/1999, page 47.’

(3180)

From pages 222-223 of ‘Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part I with the participation of Dmitry Plisetsky’ (London, 2003):

‘To the super-tournament in New York (1927), arranged to “accommodate” Capablanca, Lasker was no longer invited.’

Zenón Franco Ocampos (Ponteareas, Spain) asks whether this is true. The answer is no, because Lasker was invited to New York, 1927.

We discussed the matter on pages 195-197 of our book on Capablanca, referring to the bitter public dispute which had arisen at New York, 1924 between Lasker and Norbert Lederer (the latter being a key figure on the organizing committees of New York, 1924 and New York, 1927).

Much additional information was presented in the article ‘New York 1927 Documentary Evidence Answers Lingering Questions’ by Hanon Russell on pages 88-104 of the first issue of the American Chess Journal (1992). A section of the article (pages 99-101) was headed ‘Why Didn’t Lasker Play?’, and it showed that although the New York, 1927 organizing committee did not believe that Lasker would participate, Lederer ...

‘... made an extraordinary effort to convince Lasker to play. He enlisted the help of influential people in the United States and Europe, but Lasker was not persuaded. Finally, as the plans which were formulated had to be finalized, Lederer made one last effort. On 10 December 1926 he wrote a five-page typewritten letter in German to Lasker (Russell Collection #584). Lederer, whose first language was German (he was born in Vienna), wanted to make absolutely certain that he would not be misunderstood. Lederer’s formal invitation to Lasker specified all the terms, financial and otherwise, being offered to Lasker as well as a strong plea for Lasker to relent and play in what was recognized even then as one of the world’s great chess tournaments.’

Lasker refused the invitation.

See also pages 74 and 640 of Emanuel Lasker: Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by R. Forster, S. Hansen and M. Negele (Berlin, 2009).

(6738)

Extensive additional information is given in Lasker Speaks Out (1926) by Richard Forster.

Have any corrected editions of Kasparov’s Predecessors series been published?

This illustration comes from pages 46-47 of the work mentioned in C.N. 9839: Chamo-me ... Garry Kasparov (Lisbon, 2011), Me llamo ... Garri Kasparov (Badalona, 2013) and Em dic ... Garri Kasparov (Badalona, 2013).

(11024)

See too C.N. 11449, concerning two games (Lasker v Schlechter and Sämisch v Nimzowitsch).

A brief extract from C.N. 5373, concerning Kasparov’s How Life Imitates Chess:

On pages 184-185 of [the Heinemann edition] he accepts that he was justifiably criticized for volume one in his Predecessors series, thereby gratifyingly pulling the rug from under those unqualified commentators who pronounced it a masterpiece. (It somehow even received the British Chess Federation’s ‘book of the year award’ in 2003.)

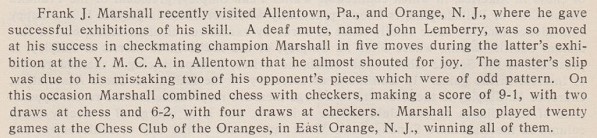

From page 72 of the April 1920 American Chess Bulletin:

Hermann Helms also related the story in the New York Evening Post, 21 February 1920, page 12. On page 11 of the 31 January 1920 edition he had announced that the display in Allentown was to take place that evening. More details are sought.

The story about ‘a dumb person’ on page 391 of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part I (London, 2003) may be recalled dolefully.

(9208)

An undated volume just acquired is Bobby Fischer World Champion for Political Reasons? by Julio Hidalgo.

Apart from the ISBN number, 9781537399676, on the (blank) back cover, the sole bibliographical information about the book, whose pages are unnumbered, is in the bottom corner of the last page:

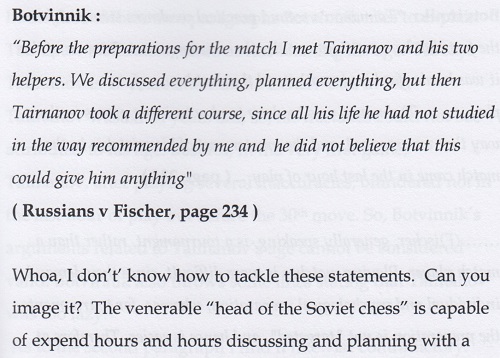

An author’s name is mentioned only on the title page, and not on the cover, but even the word ‘author’ is an exaggeration, because the book is essentially an omnium gatherum of other people’s writings. The early part lifts chunks from, among other publications, the Everyman Chess edition of Russians versus Fischer by D. Plisetsky and S. Voronkov (London, 2005), and a small example shows the literary and presentational skills of Julio Hidalgo:

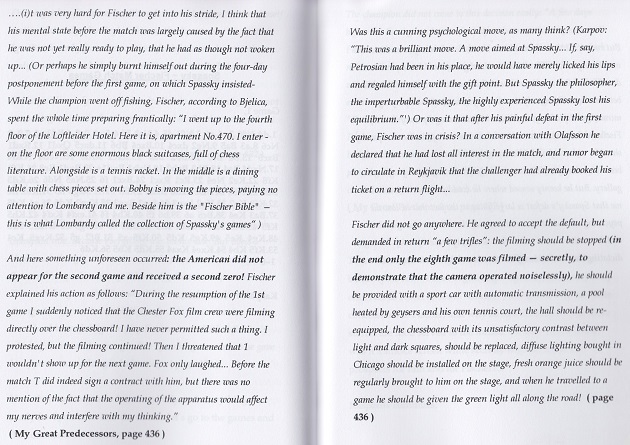

Later, it is Kasparov’s Predecessors work which dominates. Dozens of pages reproduce his text, with minimal linking material. For instance:

Another chapter, over half-a-dozen pages long, consists almost exclusively of text from Kasparov’s Child of Change. Euwe is a casualty too.

Towards the end of the book a chapter entitled ‘A Spassky Interview’ begins:

‘I have selected some paragraphs of [sic] an interview to [sic] Spassky, for Kingpin Magazine ...’

The ‘some paragraphs’ occupy six pages.

Garry Kasparov remains the chief victim of the Fischer book, but in any such case what chance of corrective action exists? How one longs for Kasparov to take a public stand, also supporting fellow victims of rapacity.

(10732)

For the benefit of those who have excessively praised (and/or copied from) the Predecessors books, below are some of Kasparov’s remarks on pages 184-185 of How Life Imitates Chess:

‘... I began work on my series of chess books in the late 1990s. A combination of editorial haste and our confidence that our analysis was better than any that had come before led to our publishing the first volume of My Great Predecessors without enough regard for the attention the book would receive in the chess community, and what that attention signified.

The first volume appeared in the summer of 2003. My in-depth look at the first four world champions and their closest rivals quickly got its own in-depth examination from tens of thousands of chess players around the globe. Nowadays this also means tens of thousands of powerful chess computers going deeply into every move, every line of my analysis. The internet allowed this distributed network of analysts and ad hoc book critics to collect and present a remarkable, and humbling, number of corrections.

... At my insistence we began to collect and do our own analysis of the corrections so that they could be incorporated into later editions of the book. In fact, many changes were ready in time for translations of the book into other languages, so, for example, the Portuguese version, which came out a year later, is far more accurate than the first Russian edition. At the same time we made our analysis and fact-checking processes much more rigorous for the subsequent volumes and each one has been better than the last in this regard. Part V, on Karpov and Korchnoi, was published in early 2006 and I’m proud to say that the vast audience of eager would-be critics has been gratifyingly quiet!

This improvement in quality would never have happened without a willingness to accept criticism and the will to do something about it. I took it as a challenge, not as an insult.’

We are not aware of any amended editions of the English-language books, and, in particular, of the most unfortunate volume one.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.