Edward Winter

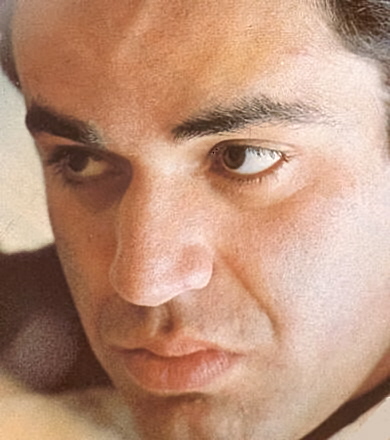

Garry Kasparov

C.N. 1143 dealt with a remark by Larry Evans in the March 1986 Chess Life that Kasparov’s generous spirit towards Fischer was alien to Karpov. We disputed this, showing that Karpov had indeed praised Fischer. But journalists, particularly in the United States, continue to lump Kasparov and Fischer together to stigmatize Karpov. They would do well to ponder some declarations by Kasparov. For example, he was interviewed by Thierry Paunin in L’Equipe magazine of 24 January 1987. Here are the relevant exchanges:

‘T.P. Do you think Fischer will play again one day and would you like to meet him?

G.K. No, I don’t think there is the slightest chance that Fischer will ever play chess again. The return of Fischer is a myth; in any case, it provides good suspense for people who know nothing about chess. Fischer is the chess past. He left because he didn’t want to play any more. Endless talk about his return is just day-dreaming.

T.P. Haven’t you ever tried to make contact with him? It is said that some grandmasters keep in touch with him ...

G.K. I don’t believe a word of it. I want proof. It is also said that he still plays. Well, let him play, let him enter a tournament and let him play! For me, Fischer is no longer anything. He has gone into history. That is very interesting from the historical point of view, but Fischer means nothing more at all today!’

Truly a generous spirit, worthy of Sir George Thomas.

(1354)

Kasparov comments on chess computers in an interview with Thierry Paunin on pages 4-5 of issue 55 of Jeux & Stratégie (published in 1989):

‘Question: ... Two top grandmasters have gone down to chess computers: Portisch against “Leonardo” and Larsen against “Deep Thought”. It is well known that you have strong views on this subject. Will a computer be world champion, one day ...?

Kasparov: Ridiculous! A machine will always remain a machine, that is to say a tool to help the player work and prepare. Never shall I be beaten by a machine! Never will a program be invented which surpasses human intelligence. And when I say intelligence, I also mean intuition and imagination. Can you see a machine writing a novel or poetry? Better still, can you imagine a machine conducting this interview instead of you? With me replying to its questions?’

From page 273 of Chess Explorations:

In an October 1989 interview published in the 1/1990 New in Chess Kasparov declared (page 49):

‘After the next world championship match I will dedicate myself to the rebuilding of the world of chess literature.’

He didn’t.

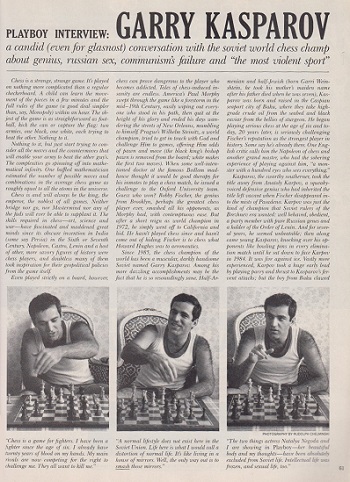

Louis Blair (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) sends us an interview with Kasparov published in the November 1989 issue of Playboy (pages 61-73), the most interesting exposition of the world champion’s views that we recall seeing. A few brief quotes:

‘Interviewer: Most people think of chess as a gentlemanly pastime. In American colleges, chess has the image of something wimps do to avoid real sports.

G.K.: Are you crazy? Let me tell you a secret: chess is the most violent of all sports. I’m a pretty good soccer player and a long-distance swimmer, and recently, I’ve taken up tennis, but I can tell you that there’s no sport as competitive – yes, I’ll say as rough – as chess. The only goal in chess is to prove your superiority over the other guy, and the most important superiority, the most total one, is the superiority of the mind. And there’s no luck involved, no picture card coming up at the right time, no roll of the dice that saves you. It all has to come out of your head. You whip him or he whips you. It’s as simple as that. Or as complicated as that.

Interviewer: Bobby Fischer used to say he enjoyed seeing his opponents squirm. He enjoyed hurting them. Is that true of you?

G.K.: I like to win the game. I love it, yes, I need it. But on the other hand, I do not like to hurt people. The game, for me, is a kind of lesson for them. I can teach them something. I don’t think I hate the opponent personally, but before the game and during the game and until the end of the game, he represents the alien will. He represents the enemy. It is not my opponent personally but what is on the board there. It is my enemy.

Interviewer: Can you explain why the level of Soviet chess is so high? Why do so many millions of people play serious chess in your country when they don’t elsewhere?

G.K.: Because most of the time, there’s nothing else to do in our country! Chess fits the Soviet Union perfectly. It’s the simplest of sports. You don’t need a special field or court for it. Just a chess set, pieces and a quiet place in the park. It’s the easiest way for people to have a little bit of enjoyment. And if you become a strong player, chess is one of the best ways for a Soviet citizen to improve his life, to get a better position and maybe raise his standard of living above the average – which is not so good, by the way.

[Interviewer: As a Russian –

G.K.: Don’t call me Russian. I’m not Russian. I am half Armenian and half Jewish. And I live in Baku, in the republic of Azerbaidzhan. You can call me a Soviet, if you like.]

Interviewer: How many moves ahead can a great chessplayer calculate?

G.K.: It depends on the nature of the position. Chess is a complicated game. But in positions where everything is forced – one move, one answer – I can calculate between ten and 15 moves ahead. But that happens very rarely. Usually, the positions are more complicated than that – one move, then five answers, each of them having five answers. You have to use your intuition in cases like that, your positional understanding. It’s very good if you can calculate five, six, maybe seven moves ahead.

Interviewer: Have you ever played blindfold chess?

G.K.: Yes. Once I played a blind simultaneous match against ten opponents in Germany. I won 9-l. Eight wins, two draws. But it was very tough for me. Very unpleasant. You have to use your capabilities one hundred percent, and it feels like even more. You don’t exactly see the whole position, but you remember its main contours. I made two mistakes in that “simul” and lost a piece. I managed to get a draw, but I didn’t enjoy it. I told you my memory is like a tape? Well, that time, it was as if the tape had been erased. It disappeared. I don’t want to do any more blind chess.

Interviewer: ... how much can the world’s chess champion earn in a year?

G.K.: Things are complicated in the Soviet Union because the authorities haven’t quite come to grips with professionalism. But let’s imagine that I live somewhere else and can do anything I want. In a normal year, if I spend all my energy on just earning money and take all the opportunities, I can earn between four hundred thousand dollars and half a million. In a world championship year, it is a lot higher. In the next match, in 1990, I expect the prize will run around three million dollars, with one point eight million going to the winner. That is to say, to me.

Interviewer: How about women chess players?

G.K.: Well, in the past, I have said that there is real chess and women’s chess. Some people don’t like to hear this, but chess does not fit women properly. It’s a fight, you know? A big fight. It’s not for women. Sorry. She’s helpless if she has men’s opposition. I think this is very simple logic. It’s the logic of a fighter, a professional fighter. Women are weaker fighters.

There is also the aspect of creativity in chess. You have to create new ideas. That’s quite difficult, too. Chess is the combination of sport, art and science. In all these fields, you can see men’s superiority. Just compare the sexes in literature, in music or in art. The result is, you know, obvious. Probably the answer is in the genes.

[Interviewer: Do you realize that you’re expressing a sexist point of view, and that Western women will be enraged by it?

G.K.: Yes, but I’m not concerned. I’m sure that women can do many things better than men in many fields. I think it’s wrong to want to be compared all the time, to want to be equal in everything. Men and women are different.]

[Interviewer: You have the sound of a politician, but you also seem to be a pretty fair businessman. Do you have ideas for future business projects?

G.K.: Sure. In our country, it’s not so difficult, because all the opportunities are just lying there, ready to be picked up. Everything needs to be done. If you have good connections with businessmen in the West, you can establish the bridge easily. But look out: this is a very special kind of place to do business. I have a friend who has a computer business in Moscow, a cooperative company. When he meets new partners from the West, his first question to them is, “Have you read Alice in Wonderland?” They will answer yes, then he says, “Imagine you are in Wonderland, and we will start our discussions from there.”

That’s how it is here. But since that is so, we can juggle all sorts of fantastic and unbelievable ideas. I just had a thought the other day: why don’t we sell the Kuril Islands to the Japanese? Frankly speaking, I’m not sure that these islands belong to us, and the Japanese, who claim them, would give us billions and billions of dollars for them! That would keep us going for maybe five or ten years. Then we could sell Mongolia to China and get a few more years that way. But the best deal would be to sell East Germany to West Germany. That would be worth a fortune – and maybe we could get even more money from England and France for not doing the deal!]

Much of the interview is given over to a discussion of international politics. The piece concludes with the following exchange:

Interviewer: So the game of chess really isn’t all there is to Garry Kasparov, is it? Chess is finally just an instrument, a weapon for you to use in your broader fight for democracy and human rights, for what you call a normal life.

G.K.: Absolutely! Now you have understood me.’

(1916)

The exchanges given above in square brackets are additions here and were not included in C.N. 1916.

Playboy, November 1989, page 61

C.N. 10433 quoted from page 268 of Deep Thinking by Garry Kasparov with Mig Greengard (New York, 2017):

‘I won’t hide from the fact that I did make regrettably sexist remarks about women in chess around this time. In that 1989 Playboy interview I said men were better at chess because “women are weaker fighters” and that “probably the answer is in the genes”. The possibility of gender brain differences aside, I find it almost hard to believe I said this considering that my mother is the toughest fighter I know.’

See also Kasparov’s Child of Change.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.