Edward Winter

‘… I have always been an erratic player, even when I was at my best. At that time, when Marshall and myself entered a tournament, the general opinion was that we could as well finish at the top as at the tail of it.’

Jacques Mieses, BCM, October 1944, page 232.

(2486)

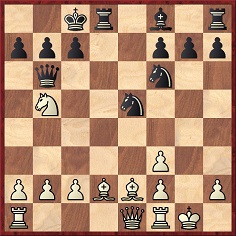

From Nine Chess Positions:

Black to move

Allies (J. Rosenthal, M. Rosenbaum and W.S. Morris)-J. Mieses, New York, 2 January 1908

12…Rxd2 13 Qxd2 Qxb5 14 f4 (‘Two pieces are now attacked simultaneously. A witty resource saves them both.’ – Emanuel Lasker.) 14…Qd7 and Black won easily.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, February 1908, page 24.

C.N. 127 gave the following win by Mieses against J.G. Heftye:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Nc3 Bc5 5 d3 d6 6 Be3 Bg4 7 Bb5 Bb6 8 Bg5 O-O 9 Nd5 Nd4 (This game provides a good illustration of the dictum that, in chess, symmetry often ends in violence.) 10 Bc4

10...Nxd5 11 Bxd8 Nf4 12 O-O Raxd8 13 c3 Nxf3+ 14 gxf3 Bh3 15 a4 d5 16 Bxd5 Rd6 17 Kh1 Bg2+ 18 Kg1 Rg6 19 White resigns.

Our source at the time (in 1982) was merely the Times Literary Supplement, 1902, page 328, but today the on-line availability of the Tidskrift för Schack, as mentioned in C.N. 9711, enables comprehensive details to be found on pages 215-217 of the October 1902 issue.

C.N. 127 had this introductory paragraph:

Mieses was a curious figure in the history of chess. He never seemed to win very much and made a minimal contribution to chess literature, yet his name will always be remembered with respect and affection. This is in large part due to the debonair attacking style of his play; he simply won a great number of beautiful games.

From John Rather (Kensington, MD, USA):

‘Jacques Mieses’ enduring reputation is founded on three circumstances: 1) incredible longevity as a player; 2) a wonderful talent for combinative play; and 3) authorship of dozens of books intelligible to fledgling players. Although he had comparatively few tournament successes (notably first at Vienna, 1907 and 3rd-4th at Ostend, 1907), he played his first tournament in 1888 at 23 and his last in 1948 at 83. During this long career (if Le Lionnais’ Les prix de beauté aux échecs is an accurate guide) he won more brilliancy prizes than anyone other than Alekhine. Even as an octogenarian he was awarded one at the Hastings, 1945-46 tournament for his game against Christoffel, certainly a record by any standard. In this same event, despite his age, Mieses was able to draw a 108-move, 7½-hour game with Prins by successfully defending with rook against rook and bishop. In Les leçons de Hastings et de Londres 1945-1946 Euwe wrote, “Mieses se defend avec une ardeur at une tenacite incroyables; ...chapeau bas pour un tel exemple d’énergie de la part de cet admirable vieillard de 81 ans (sic).” In case this enthusiastic championing of Mieses astonishes you, let me say that one of my “back-burner” projects is a collection of his games".

At Vienna, 1907 the result was: 1st Mieses, 10. 2nd Důras, 9. 3rd-5th Maróczy, Tartakower, Vidmar, 8½. 6th Schlechter, 7½. Curiously, however, the crosstable given on page 201 of The Year-Book of Chess 1911 (and in fact also in other years of the Michell book] claims that Tartakower finished with only 8 points, his game against Martinolich being drawn. This is not so, Tartakower’s win being given on pages 183-184 of the May-June 1907 Wiener Schachzeitung; luckily the mistake that the Year-Book went on repeating does not appear to have been copied in modern sources, where Tartakower is awarded his full 8½ points.

The huge Ostend, 1907 Master Tournament was a fine success indeed for Mieses, who finished equal third with Nimzowitsch, half a point behind the joint winners Bernstein and Rubinstein. Mieses nonetheless lost seven games, although even Bernstein, at the top of the list, had the rare experience for a tournament winner of being defeated five times.

Mieses, like Anderssen, Janowsky and so many other fine players, is nearly always illustrated in chess anthologies by the same old (brilliant) games, with no effort being made to offer readers a battle they are less likely to have seen before. The following unknown game, for instance, is vintage Mieses:

Jacques Mieses – Eugène Znosko-Borovsky

Ostend, 7 June 1907

Vienna Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 d3 Bb4 5 Bg5 d6 6 Nge2 Be6 7 O-O h6 8 Bxf6 Qxf6 9 Nd5 Bxd5 10 Bxd5 Bc5 11 Bxc6+ bxc6 12 Kh1 d5 13 f4 exf4 14 Rxf4 Qe7 15 d4 Bb6 16 Ng3 O-O-O 17 e5 c5 18 c3 cxd4 19 cxd4 Kb8 20 a4 a5 21 b4 Qxb4 22 Rb1 Qe7 23 Qf1 Ka7 24 Rxb6 Kxb6 25 Qb5+ Ka7 26 Qxa5+ Kb7 27 Rf1 Rb8 28 Nf5 Qe6 29 Nd6+ cxd6 30 Rb1+ Resigns.

Further to C.N.s 127 and 566, Philipp Mottet (Zuchwil, Switzerland) provided in C.N. 611 a non-exhaustive list of books and booklets by Mieses:

Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (several editions with Dufresne), San Sebastián, 1911 (with Lewitt), San Sebastián, 1912 (with Lewitt), Der Schachlotse, Das Damengambit, Das nordische Gambit, Die Französische Partie, Hundert lehrreiche Stellungen aus Schachmeisterpartien, Lehrreiche Blumenlese aus Schachmeisterpartien, Das Endspiel in der modernen Meisterpraxis, Taschenbuch des Endspiels, Moderne Endspielstudien, Kaschau, 1918, Das Buch der Schachmeisterpartien (volumes II-V), Das Blindspielen.

Slim volumes which appeared during Mieses’ later years, in England: Instructive Positions from Master Chess, Manual of the End Game, The Chess Pilot.

Further to John Rather’s ‘back-burner’ comment in C.N. 566 above, we add that C.N. 821 (September-October 1984) quoted from the last letter that we received from W.H. Cozens, in which he told that us he was making a collection of the games of Jacques Mieses but that ‘Whether I shall ever do anything with it I doubt: Time’s winged chariot ...’

C.N. 548 recorded the death of Salo Flohr and gave as an illustration his victory over Mieses in the Bournemouth tournament, August 1939, with some brief text from the October 1939 BCM.

An extract from a letter sent by Harry Woolverton to Newsflash (see July 1984 issue, page 6):

‘It is not generally known that Aitken played a match with the veteran Mieses in 1947 which he won by 5½-1½. In deference to the feelings of the old master the result was never published. I watched the second game, which was played at the Ilford Chess Club; a collection was made at the time for the veteran.’

(787)

Page 34 of the 23 October 1909 issue of the Chess Weekly reported that in Washington that month Capablanca won ‘16 straight off-hand games from Moorman, who in a similar seance with Jacques Mieses two years ago was able to divide the honors with the German master’.

We have biographical information on file about Wilbur Lyttleton Moorman (1859-1934) but no further data about his meetings with Capablanca and Mieses.

(2208)

On pages 467-468 of the November 1939 BCM Jacques Mieses wrote:

‘It is my opinion that already nowadays the standard of the art of chess is so high, that a considerable advance from the theoretical point of view seems to be hardly possible. I doubt if there will appear any modern Philidors and Steinitzes preaching new ideas in chess. Should the grandmasters of future times be better than ours, it would be probably only for their superior technique. Thus even for the leading masters of the modern generation there is little left for improvement, since they are no doubt much nearer to their culmination than my generation had been when at the same age.’

(2675)

In an article on pages 260-261 of the August 1940 BCM Mieses related that during a visit to New Orleans in 1903 he had had a conversation with Maurian.

‘His reminiscences were very fresh and reliable, and from them I gathered a vivacious and uncoloured picture of Morphy’s personality. Maurian having been a school fellow of Morphy’s, was two years younger than he and had been introduced by him into the secrets of chess.

I was, of course, chiefly interested in getting remarks by Morphy about the game of chess, about his opponents and concerning himself. In Morphy’s character a high degree of self-confidence, quite free from conceit, was combined with strict self-criticism. After his return from his first journey to Europe which, as is known, had been a very triumphal procession, he told Maurian that he was not at all satisfied with what he had done, since he was quite certain that he could play much better than he had shown. This was partly due to the fact that he had seldom met opponents even nearly equal to himself. He had a high opinion of Anderssen and of Heydebrand von der Lasa. Of the masters of the generation preceding his he most appreciated Labourdonnais; also he thought highly of Hanstein.’

Mieses also wrote:

‘I once asked [Paulsen] “Whom of all the masters you met over the board do you consider to be the strongest?” Louis Paulsen, who was generally known to be very reserved, especially concerning judgments about other masters’ qualities, replied, without hesitation: “Morphy”. In order to substantiate his opinion he added: “If you asked him after the game what he would have replied to this or that move, he at once, without considering, fully explained the continuations he had intended to play. Then one could not but realize, with admiration, how many possibilities he had taken into consideration and how far he had calculated ...”’

‘May I finally mention that, of the living great masters, Maróczy and Rubinstein have made a special study of Morphy’s games. They both told me that they believe him to be the strongest player that ever lived.’

The above quotes were given on pages 390-391 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves. A footnote on page 390 pointed out, regarding the first paragraph by Mieses, that Maurian was only 11 months younger than Morphy.

A forgotten game:

Jacques Mieses – O. Goertz

Leipzig, 30 June 1924

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 Nge2 Nc6 4 g3 Nf6 5 Bg2 Be7 6 d4 cxd4 7 Nxd4 a6 8 O-O Qc7 9 Re1 h5 10 Bf4 Qb6 11 Be3 Ng4 12 Nf5 Nxe3 13 Nxe3 Qxb2

14 Ncd5 Bd8 15 Nc4 Qd4 16 Nd6+ Kf8 17 Qe2 Qc5 18 e5 exd5 19 Rad1 d4 20 Rd3 Be7 21 Rf3 Nxe5 22 Rxf7+ Kg8 23 Rxe7 Ng6 24 Qf3 Resigns.

Our source is the two-volume Schachjahrbuch 1924 by Ludwig Bachmann (see Chess in 1924).

Page 320 of the October 1885 International Chess Magazine reported that J. Mieses took 34 minutes to solve the following composition by Franz Schrüfer of Bamberg:

Mate in four

The key move is 1 f6. Among the many possible lines is 1…Bxf6 2 Ng5 Bxe7 3 Nh7 any 4 Qe4 mate.

This composition was given on page 13 of A Chess Omnibus.

On page 7 of The Kipping Chess Club Year Book 1943-1944 Mieses referred to his draw against Steinitz at Hastings, 1895:

‘At the conclusion of the game he congratulated me upon the quality of my play and I feel bound to say flattery was by no means his weakness, and I was very proud of having impressed the world’s greatest chess connoisseur by my play.

It is no way “a game for the gallery” but rather one in which the expert will discover the “ghosts slumbering under the cover” …’

(A Chess Omnibus, page 395)

From the 2002 Bled Olympiad bulletins:

‘When 83-year old grandmaster Mizes defeated Dutch master Van Forest (85 years old) at a tournament in 1950, he told journalists, “Quite simply, youth won!”’

Not exactly. Mieses, not Mizes, was 84, not 83, van Foreest, not Van Forest, was 86, not 85, the game was played in 1949, not 1950, and the occasion was an exhibition game, not a tournament.

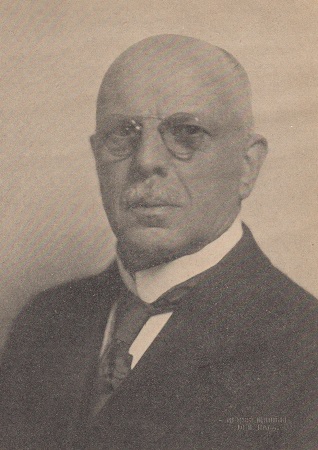

Mieses himself gave the game (which was played in The Hague on 26 March 1949) on pages 178-179 of that year’s June issue of the BCM:

‘… In spite of my age – I am 84 – I am still very active in competitive master chess. I am only stating a matter of fact by pointing out that never before in [the] history of chess an expert of my age, or even of nearly my age, has done the same. Quite recently, however, I learned that the well-known Dutch player, Dr D. van Foreest, who, with 86 years, is two years older than I am, has by no means yet retired from active chess, being still very fond of playing off-hand games. I had met him in former times – about 30 years ago – and I remember that, then, he had the reputation of being one of the strongest players in Holland. Now he lives in The Hague and he is still considered to be “quite a good amateur”.

This gave The Royal Dutch Chess Association the happy idea of arranging a remarkable and, up to now, quite unique event, namely a serious game, played in tournament style with time limit (18 moves an hour) between two players of reputation, the combined ages of them being 170 years (!).

Here is the game with some annotations. It formed the conclusion of my exhibition in Holland.

Dirk van Foreest – Jacques Mieses

The Hague, 26 March 1949

Sicilian Defence1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e6 5 c4 (In my opinion not the strongest way of treating this variation.) 5…Nf6 6 Bg5 (This loses a pawn. White should have first played 6 Nxc6.) 6…Qa5+ 7 Bd2 Qe5 8 Nxc6 Qxe4+ 9 Be2 bxc6 10 O-O (It is a very well-known matter of experience that losing a pawn in the opening by a mistake is often the involuntary equivalent of playing a quite promising “gambit”. Thus, here, White, with a pawn down, has undoubtedly got a compensating advantage in development.) 10…Bc5 11 Bc3 Qf4 12 b4 Be7 13 g3 (This is a grave positional mistake weakening the king’s side.) 13…Qc7 14 Bd3 c5 15 b5 Bb7 16 Qe2 h5 (Promptly taking advantage of his obvious attacking chances.) 17 Nd2 (Even after 17 h4 White’s position would soon become untenable.) 17…h4 18 Ne4 Nh5 19 Rad1 f5 20 White resigns. (White resigned the hopeless game. When I announced the result of the game I caused much hilarity by adding the joking remark: “Die ‘Jugend’ hat gesiegt.” (“‘Youth’ has triumphed.”)’

On page 111 of Meister Mieses (Ludwigshafen, 1993) Helmut Wieteck bizarrely stated that the game had been played in ‘Kap de la Hague’ in ‘France’.

Dirk van Foreest. Source: Een Hulde aan Jhr. Dirk van Foreest by L. Prins (Lochem, 1945)

(2814)

From the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

C.N. 2814 (see pages 69-70 of Chess Facts and Fables) gave Mieses’ annotations to his famous victory (‘“Youth” has triumphed’) over Dirk van Foreest in the Hague on 26 March 1949. Although Mieses’ article (BCM, June 1949, pages 178-179, and shown in full in our feature article) specifically stated that his opponent was D. van Foreest, an on-line search for ‘youth has triumphed’ and ‘Arnold van Foreest’ will yield dissenting (unsourced, naturally) versions.

There is even this ‘pair’:

‘By the way, Arnold van Foreest plays a part in a well-known anecdote in which Jacques Mieses stars. In 1949, in The Hague, after Mieses (84 at the time) had won an exhibition game against Arnold (86), he caused much hilarity with the classic remark: “Youth has triumphed!”’

Source: ‘A Remarkable Chess Family’ by Hans Ree.

And:

‘Much later Dirk van Foreest gained a place in international chess lore because of a game in The Hague in 1949 between him and Jacques Mieses. Dirk van Foreest was 86 at the time. Mieses was much younger, a mere 84. Mieses won and exclaimed happily, “Youth has triumphed!”’

Source: ‘A Remarkable Family’ by Hans Ree.

(10120)

The truth about the longevity of Jacques Mieses (1865-1954) is indeed remarkable. Lodewijk Prins wrote on page 87 of Master Chess (London, 1950):

‘He was the prodigy of the master tournament at Hastings, 1945-46, and his tour of Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg and Germany, where he gave simultaneous displays in 1949, at the age of 84, is unique in the history of chess.’

Page 12 of the January 1949 BCM reported, on the basis of a letter received from Mieses, that he had just given 15 simultaneous exhibitions in Sweden. In an article on pages 178-179 of the June 1949 BCM Mieses wrote:

‘From the middle of February till the end of March I was engaged in a chess tour of Holland, Belgium and Luxemburg. That Holland and Belgium are countries where chess life is highly flourishing is a very well-known fact and, thus, I was not surprised that in Amsterdam, The Hague, Brussels, Antwerp, Louvain, Verviers, Charleroi they put up against me, in simultaneous exhibitions, rather strong teams of, on average, more than 20 players. But what I had not expected was that in Luxemburg I should have to give three simultaneous displays – each of them against about 25 opponents – on three consecutive days. Apart from the simultaneous displays I played, in Holland, repeatedly four serious simultaneous games against first-class amateurs. In all these exhibitions my achievements have been quite satisfactory.’

Can readers trace any forgotten games from these tours by Mieses?

(3109)

A portrait of Arnold van Foreest published on page 191 of the June 1938 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

(11587)

The ‘Anecdotes’ chapter in Irving Chernev’s book The Bright Side of Chess provides an opportunity for assessing his factual dependability in this field, and we have selected four stories more or less randomly.

On pages 13-14 Chernev expended 16 lines on describing how Mieses, bitter over his 13th-round loss to Gunsberg in the Vienna, 1903 tournament, exclaimed, ‘It is bad enough to get run over, but to get run over by a corpse is horrible’. Apart from an error regarding Gunsberg’s score before that game (it was +0 –10 =2, not +0 –11 =1), the factual basis of Chernev’s story is correct, although it might have been mentioned that the episode had been recounted by Gunsberg against himself (Chess Pie, 1922, pages 76-77):

‘I ought to mention the Vienna Gambit Tournament even if it is only for a good epigram made by Mieses. He was one of the few against whom I scored. The poor man afterwards said: “It is bad enough to get run over, but to get run over by a corpse is horrible.” (This refers to my low score.)’

Gunsberg’s final tally at Vienna, 1903 was +1 –15 =2.

(3089)

Users of the FatBase 2000 CD will be awe-struck by some of the defeats sustained by Jacques Mieses during his long career. At the age of minus three he lost a game to Adolf Anderssen (in Breslau, 1862) and did no better against him in 1867, by which time he had matured into a two-year-old. Nor did the passing of time improve Mieses’ fortunes. In 1958 he lost a game to Mikhail Tal in the Soviet Union, and in 1964 Forgács beat him in Ostend. At the age of 128 Mieses was defeated by Carl Schlechter in the Prague, 1993 tournament. That was certainly an opportunity for him to recall a remark he had made 90 years previously: ‘It is bad enough to get run over, but to get run over by a corpse is horrible.’

(3108)

What are the origins of the famous ‘Mister Meises/Meister Mieses’ story? On page 182 of CHESS, 20 March 1960 B.H. Wood wrote, ‘This anecdote first appeared in print in CHESS many years ago’.

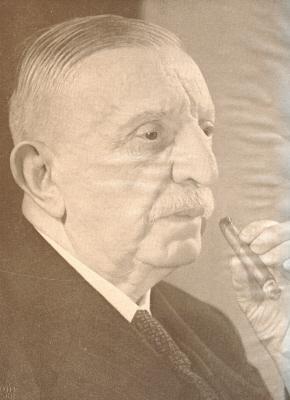

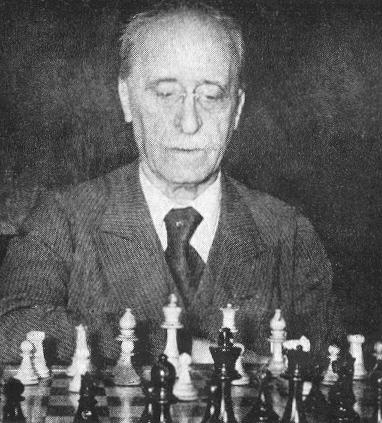

Jacques Mieses

(4729)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) points out that the story was published on pages 169-170 of Schachwart, September 1932, as follows:

‘Ein Wortspiel.

Als Mieses vor langen Jahren in England weilte, stellte ihn der damals recht bekannte englische Amateur Judd einem anderen englischen Spieler mit den Worten vor: “Mister Meises – ”. Hier unterbrach ihn Mieses lächelnd und wandte sich an den Engländer: “Entschuldigen Sie, aber ich bin nicht Mister Meises, sondern Meister Mieses.”’

Our correspondent comments that this report pre-dates B.H. Wood’s magazine CHESS, which was first published in 1935. The reference to a well-known English (sic) amateur named Judd is strange.

Assiac set the story not in England but in New York when relating it on page 186 of The Delights of Chess (London, 1960):

‘One day in New York he was asked by a German-American who mispronounced his name the English way: “Sind Sie Mister Meises?” “No, sir”, he answered like a shot, “Ich bin Meister Mieses.”

The old boy was full of such anecdotes and reminiscences when he was in a good mood.’

(4733)

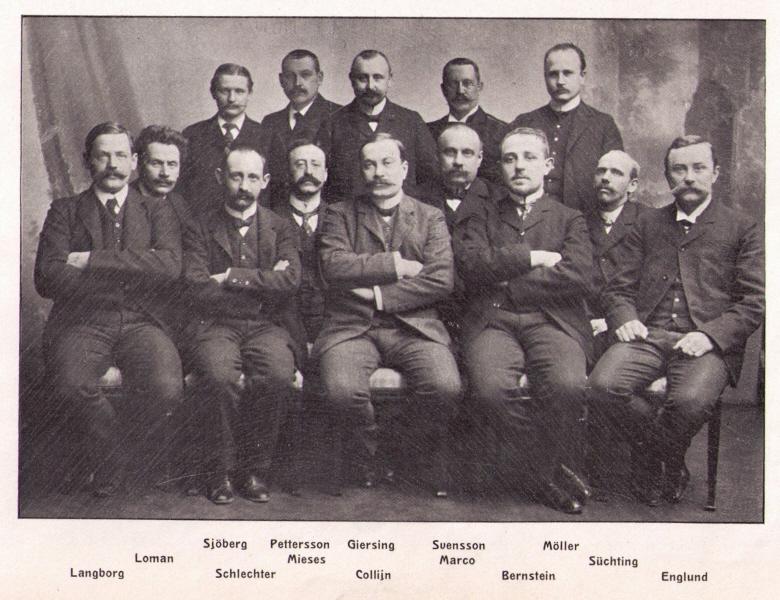

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) sends this group photograph taken during the Stockholm, 1906 tournament, from that year’s Tidskrift för Schack (between page 56 of issue 3 and page 57 of issue 4/5):

(5221)

In an article on pages 406-408 of the September 1976 BCM D.J. Morgan related that in 1938 (late June) he learned from James Gilchrist of Jacques Mieses’ arrival in England (‘he has made a hurried escape from Nazi Germany’). Morgan resumed his old acquaintance with Mieses the next day and noted that ‘in his flight he had brought little with him except his wonderful chess endowments’. Morgan added:

‘The afternoon and evening glowed with chess memories and demonstrations. In particular, he spoke with endearing words of the great Carl Schlechter, and played from memory the game which he won as Black from Carl at St Petersburg, 1909, a feature of which was the unusual activity of Black’s queen. But his favourite among his own games was the one he won from Janowsky at Paris, 1900.’

On pages 86-87 of the May-June 1935 issue of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français Mieses annotated the Janowsky game. He stated that selecting it as his favourite game had not been easy, since over a dozen of his games had won prizes and his preferences sometimes changed: ‘ayant joué dans ma carrière plus d’une douzaine de parties récompensées par un prix de beauté, je me trouve dans la situation d’un père qui a plusieurs enfants chéris et dont la prédilection pour l’un ou l’autre change de temps en temps.’

‘My Most Exciting Game’ was the title of an article by Mieses on pages 280-281 of CHESS, 14 April 1939. He selected his win over Curt von Bardeleben at Barmen, 1905 – ‘it holds as much interest and excitement as I would ever wish to experience’. Mieses added that ‘Curt von Bardeleben at his best was one of the strongest players of all time’.

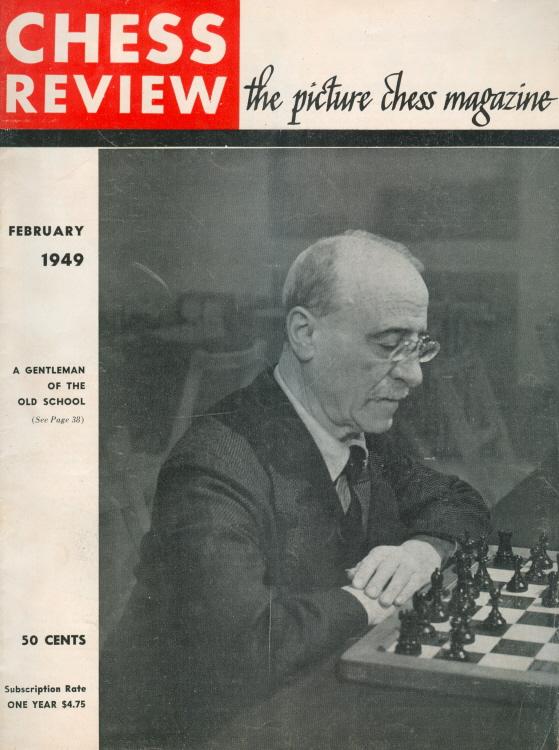

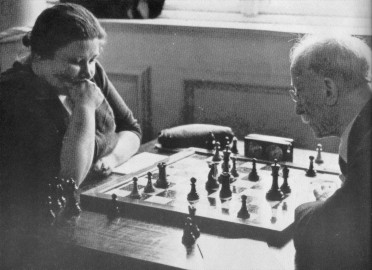

This photograph of Mieses in play against Tartakower at Hastings, 1945-46 was published on page 7 of the January 1946 Chess Review.

(6430)

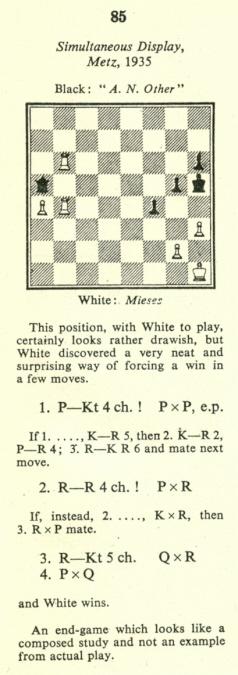

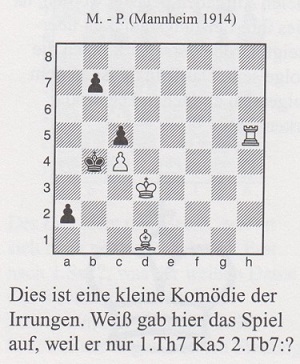

Wanted: more details about a game whose finish was published on page 51 of Instructive Positions from Master Chess by Jacques Mieses (London, 1938):

Some other sources – such as pages 44-45 of the fifth edition of Kombinationen by Kurt Richter (Berlin, 1978) – state that the game occurred around 1906.

(6431)

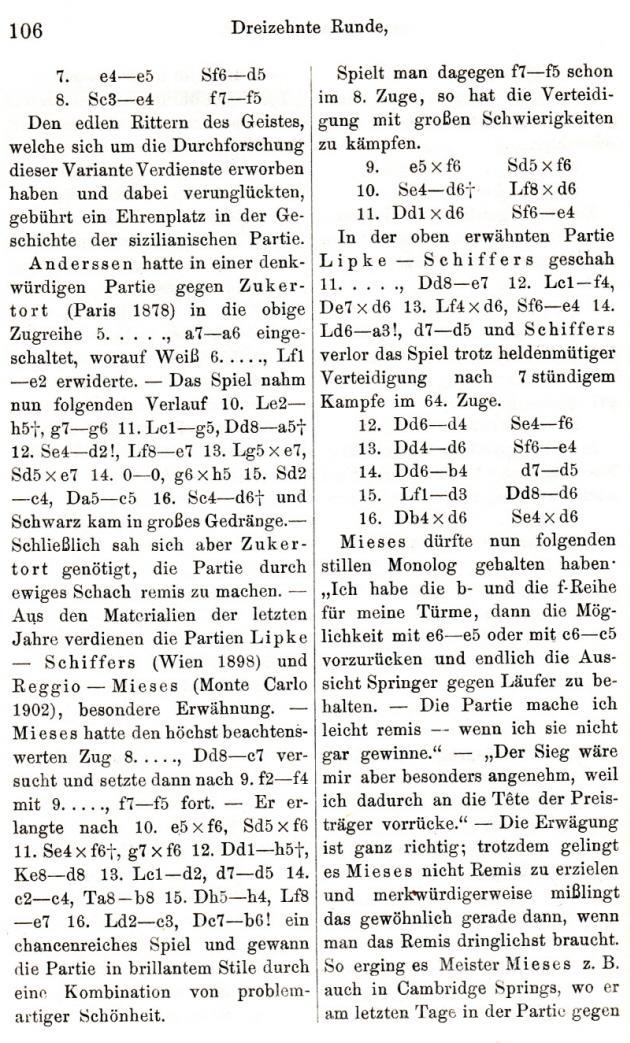

A number of websites continue to ascribe to Spielmann, rather than Mieses, the familiar ‘water and poison’ remark concerning Lasker, so it is worth recalling that C.N. 3161 (see pages 246-247 of Chess Facts and Fables) gave three quotes:

1) From an article by Mieses in the Berliner Tageblatt which was reproduced on page 16 of his San Sebastián, 1911 tournament book:

‘Laskers Stil ist klares Wasser mit einem Tropfen Gift darin, der es opalisieren lässt. Capablancas Stil ist vielleicht noch klarer, aber es fehlt der Tropfen Gift.’

2) The translation on pages xix-xx of the French edition of the book:

‘Le style de Lasker pourrait être comparé à de l’eau claire recevant une goutte de poison qui la rendrait opaline; le style de Capablanca est peut-être encore plus clair, mais il y manque la goutte de poison.’

3) An English version by J. du Mont on page 13 of H. Golombek’s book Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947):

‘Lasker’s style is clear water, but with a drop of poison which is clouding it. Capablanca’s style is perhaps still clearer, but it lacks that drop of poison.’

Chess Facts and Fables explained the misattribution to Spielmann by reproducing page 107 of Irving Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948):

(7697)

See too Muddled Chess Epigrams.

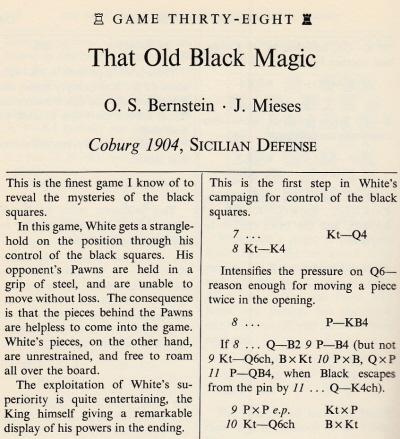

From page 160 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev (New York, 1965):

In his annotations to the game (pages 160-165) Chernev did not indicate explicitly which move or moves caused Black’s defeat. See too his notes in Logical Chess Move by Move (New York, 1957).

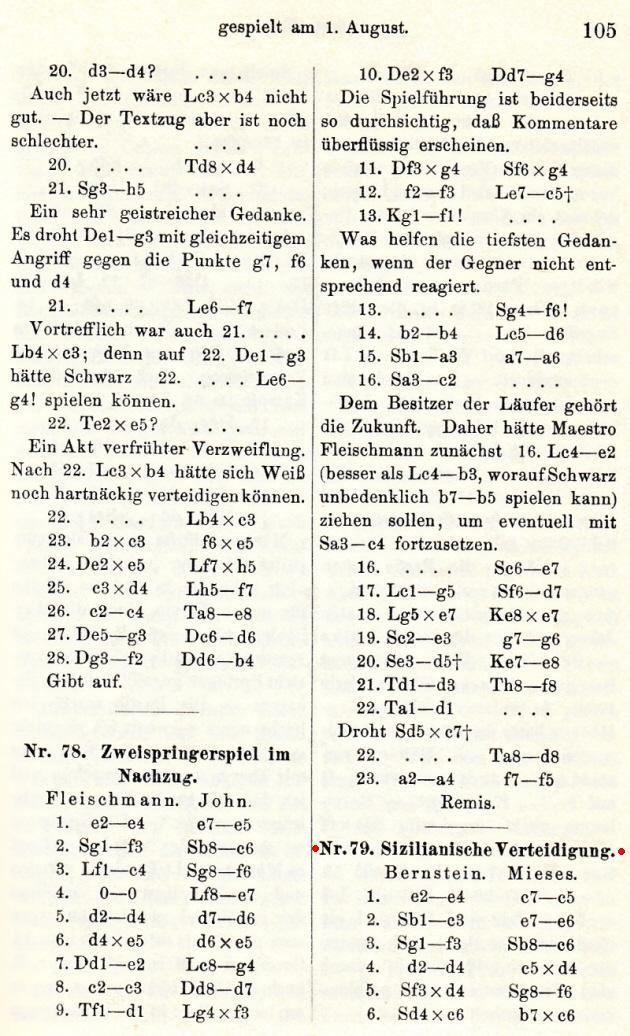

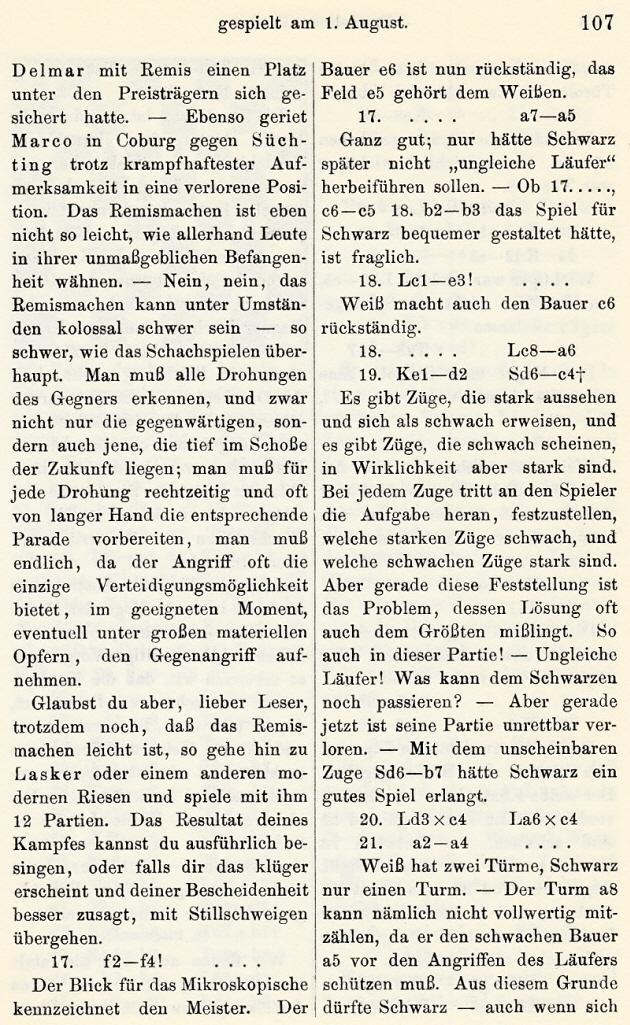

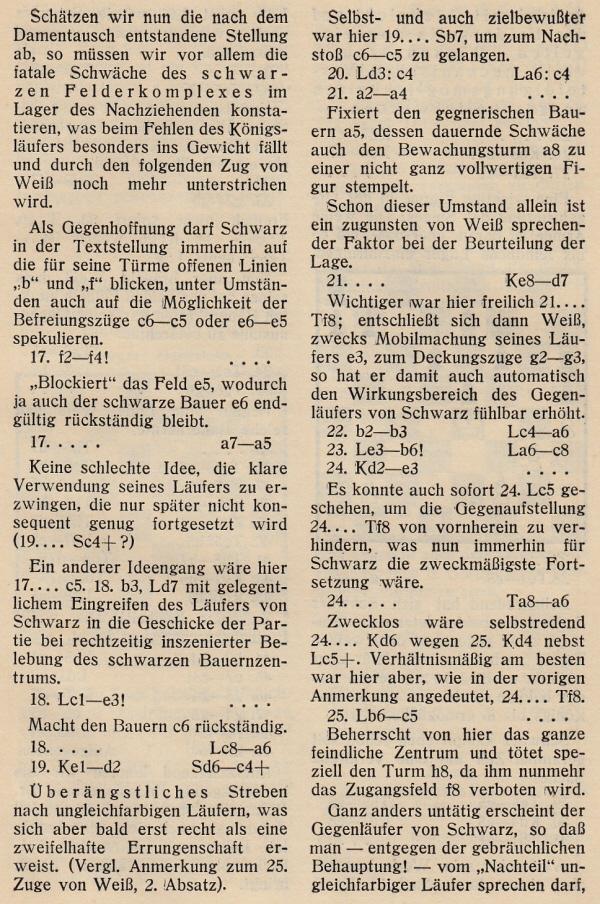

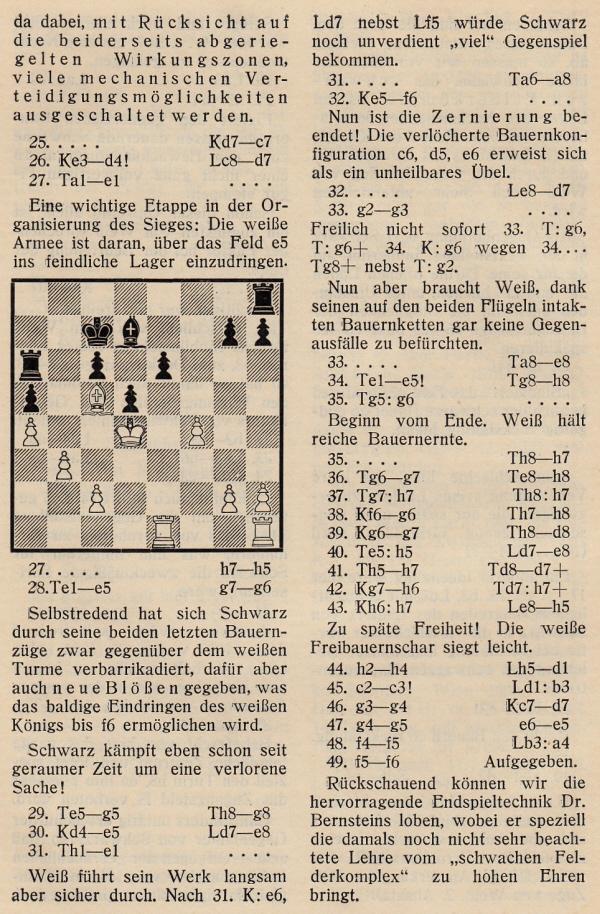

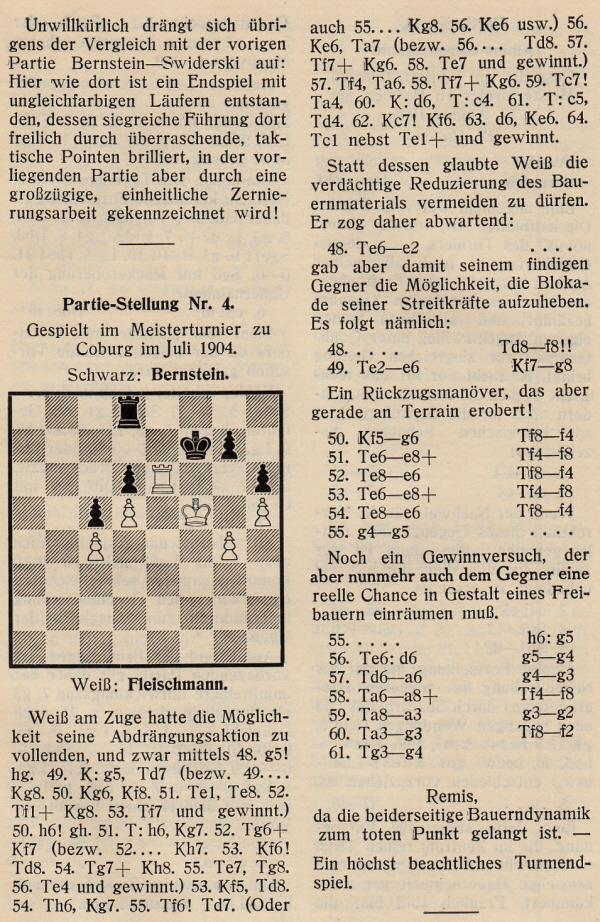

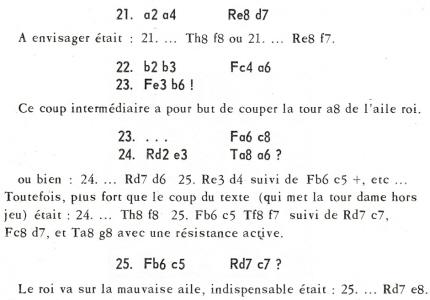

Below is the game as it appeared with Georg Marco’s annotations on pages 105-109 of the Coburg, 1904 tournament book, which Marco edited with Paul Schellenberg and Carl Schlechter. (The Vorwort on page iii specified that Marco annotated the Bernstein v Mieses game.)

The notes were reproduced on pages 361-364 of the December 1905 Wiener Schachzeitung.

Next, Tartakower’s annotations from pages 36-39 of his monograph on Bernstein, Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930):

The score according to the above German-language sources was: 1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Nxc6 bxc6 7 e5 Nd5 8 Ne4 f5 9 exf6 Nxf6 10 Nd6+ Bxd6 11 Qxd6 Ne4 12 Qd4 Nf6 13 Qd6 Ne4 14 Qb4 d5 15 Bd3 Qd6 16 Qxd6 Nxd6 17 f4 a5 18 Be3 Ba6 19 Kd2 Nc4+ 20 Bxc4 Bxc4 21 a4 Kd7 22 b3 Ba6 23 Bb6 Bc8 24 Ke3 Ra6 25 Bc5 Kc7 26 Kd4 Bd7 27 Rae1 h5 28 Re5 g6 29 Rg5 Rg8 30 Ke5 Be8 31 Re1 Ra8 32 Kf6 Bd7 33 g3 Rae8 34 Ree5 Rh8 35 Rxg6 Rh7 36 Rg7 Reh8 37 Rxh7 Rxh7 38 Kg6 Rh8 39 Kg7 Rd8 40 Rxh5 Be8 41 Rh7 Rd7+ 42 Kh6 Rxh7+ 43 Kxh7 Bh5 44 h4 Bd1 45 c3 Bxb3 46 g4 Kd7 47 g5 e5 48 f5 Bxa4 49 f6 Resigns.

The position after 26...Bd7:

The Chernev books gave White’s 27th move as Rhe1 instead of Rae1.

A slightly different ending (without 46...Kd7) can also be found in some databases. Indeed, one database that we consulted offered three versions of the game, and none of them corresponded exactly to the moves in the tournament book.

As regards possible errors by Black, his 24th and 25th moves received question marks on page 45 of O.S. Bernstein (Grand maître international d’Echecs) by J. Cena:

On the same page Cena gave 27 Rae1, and not 27 Rhe1. The privately-printed book contains no date or place of publication; it was listed for sale on page 83 of the March 1968 BCM.

Moves 19-40 of the game (with 27 Rhe1) can be found on pages 43-44 of Positional Chess Handbook by Israel Gelfer (London, 1991). The only move criticized was 19...Nc4+, which Cena had passed over in silence.

In Logical Chess Move by Move (see, for instance, page 180 of the 1998 algebraic edition published by B.T. Batsford Ltd.), Chernev pointed out that at move 11/13 (taking account of a repetition of moves) Alekhine suggested ...Qb6. We are not aware that Alekhine ever annotated, or even mentioned, the Bernstein v Mieses game, but he commented on the position when it arose in Yates v Emanuel Lasker at New York, 1924. From page 186 of the tournament book:

Finally, concerning Bernstein’s 17 f4 Chernev wrote on page 161 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played:

‘It was about moves of this sort that the great annotator Marco said, “An eye for the microscopic betokens the master”.’

The quote was also included in Logical Chess Move by Move. From the above annotations in the Coburg, 1904 tournament book it will be seen that Marco’s comment in German was, on page 107:

‘Der Blick für das Mikroskopische kennzeichnet den Meister.’

(8704)

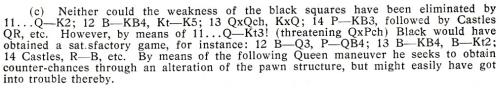

This is a further game from the score-books of A.G. Laing (C.N.s 8728 and 8762), and a late specimen of play at the odds of pawn and two moves. The only information about the occasion is ‘Eastman Cup’, but the chronological order suggests that the game was played in or around October 1941.

A.G. Laing – Jacques Mieses

Eastman Cup, London (1941?)

(Remove Black’s f-pawn.)

1 e4 … 2 d4 c5 3 Qh5+ g6 4 Qxc5 e6 5 Qb5 Nf6 6 Nc3 Nc6 7 Nf3 a6 8 Qd3 Bg7 9 Be3 d5 10 exd5 exd5 11 Qd2 Bf5 12 Bd3 Ne4 13 Bxe4 dxe4 14 Ng5 Qe7 15 f3 exf3 16 Nxf3

16...Nb4 17 Rc1 Nxc2+ 18 Rxc2 Bxc2 19 O-O O-O 20 Bg5 Qd7 21 Qxc2 Bxd4+ 22 Kh1 Qg4 23 Qb3+ Kh8 24 Qxb7 Rae8 25 Rd1 Rxf3 26 Qxf3 Qxg5 27 g3 Qe5 28 Rd2 and White resigns.

(8877)

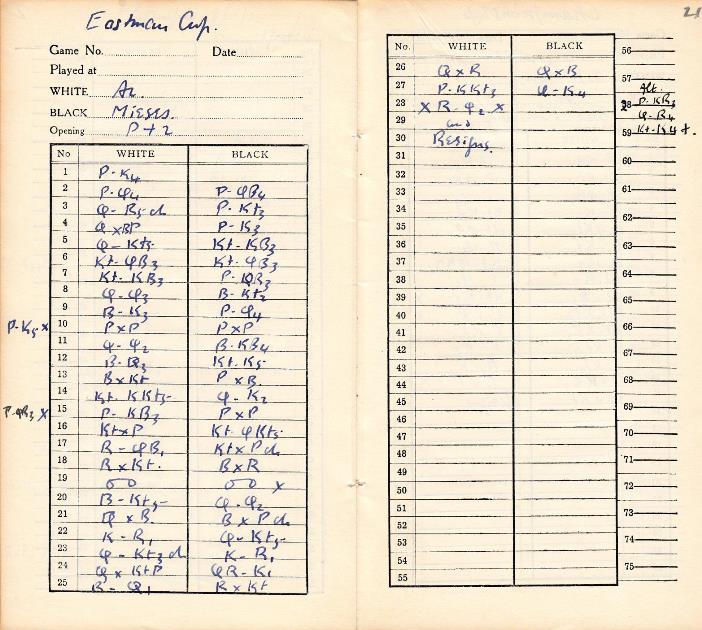

Below is another game from the score-books of A.G. Laing. It was played shortly before Mieses’s 77th birthday:

A.G. Laing – Jacques Mieses

London, 21 February 1942

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 Nc6 2 Nf3 d5 3 exd5 Qxd5 4 Nc3 Qa5 5 d4 Bg4 6 Be2 O-O-O 7 Be3 Bxf3 8 Bxf3 Nxd4 9 Bxd4 e5 10 Bxb7+ Kxb7 11 Qf3+ Kb8

12 b4 Bxb4 13 O-O Rxd4 14 Rab1 Kc8 15 Qf5+ Kd8 16 Ne2 Ne7 17 Qxf7 Rd7 18 c3 Qa6 19 Qf3 Bc5 20 Ng3 Nc8 21 Ne4 Bb6 22 Rfd1 Qxa2 23 Rxd7+ Kxd7 24 Rd1+ Nd6 25 Qg4+ Kc6 26 Qxg7 Qe2 27 White resigns.

(8967)

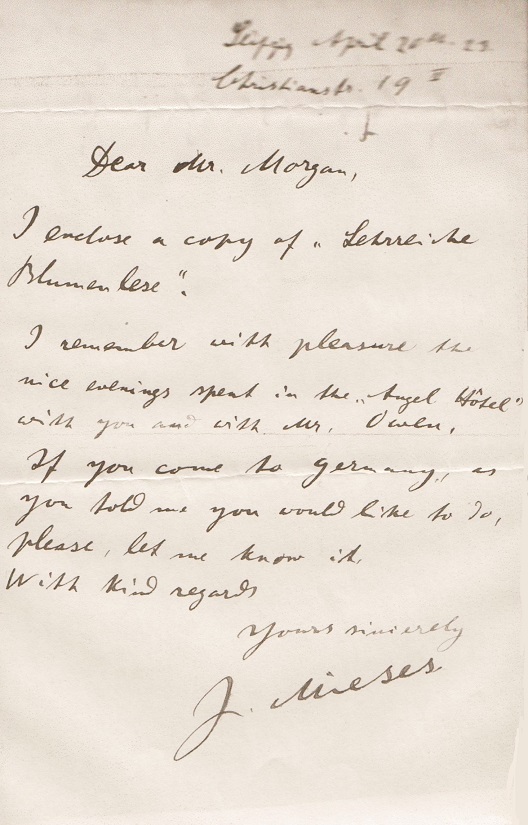

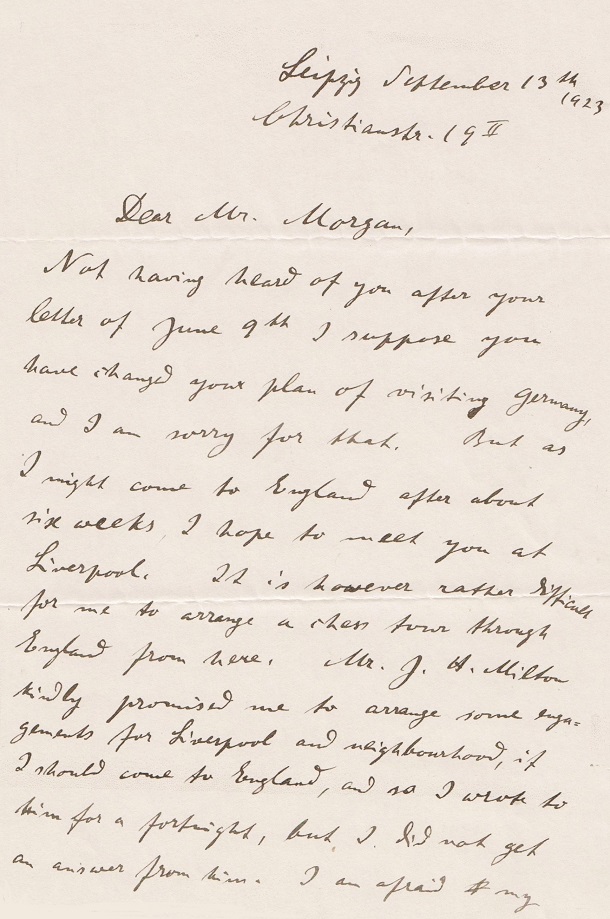

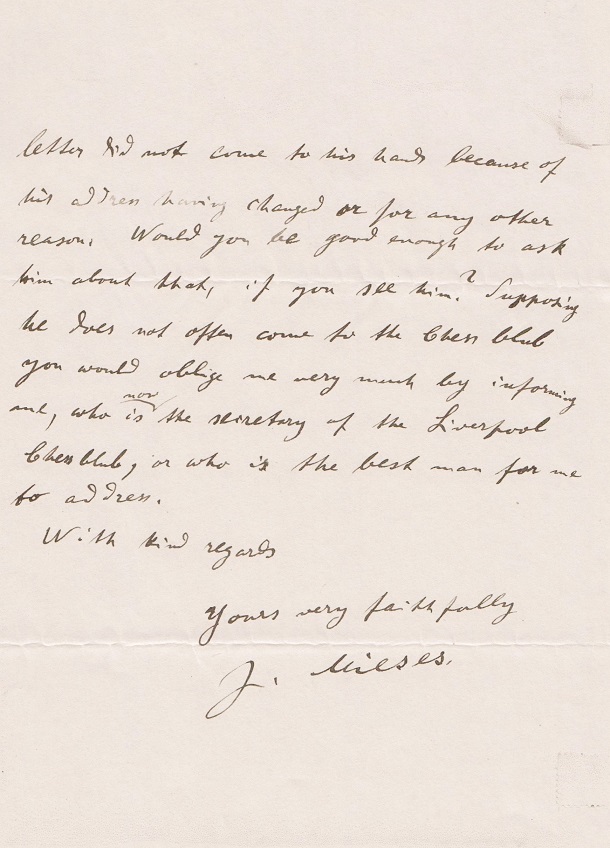

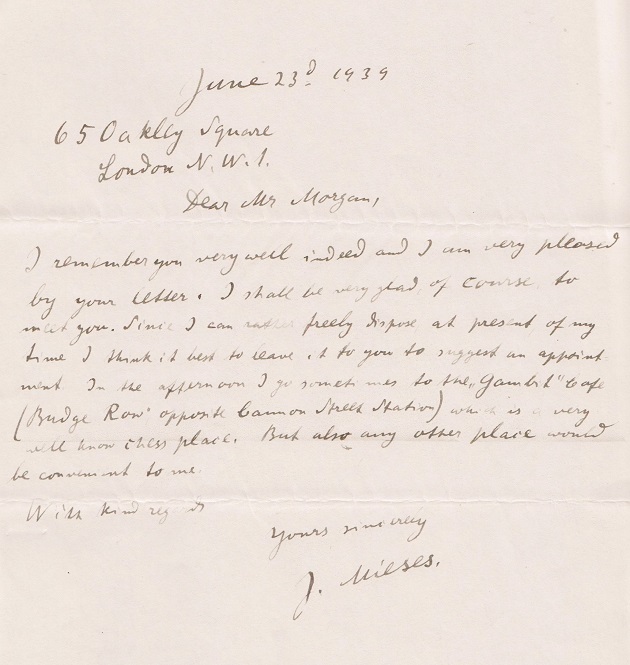

Professor Lord Morgan (Oxford, England) has forwarded us copies of three letters sent to his father, D.J. Morgan, by Jacques Mieses:

(11331)

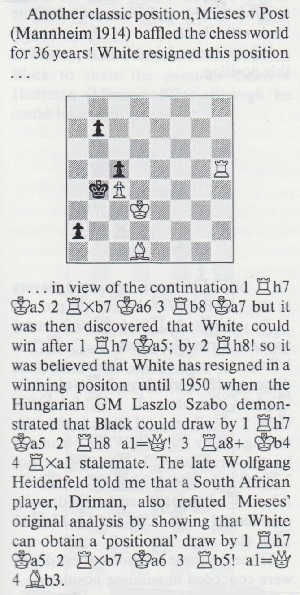

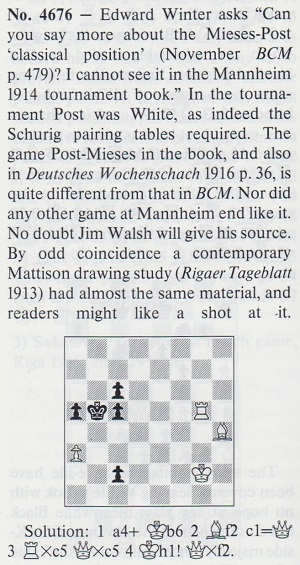

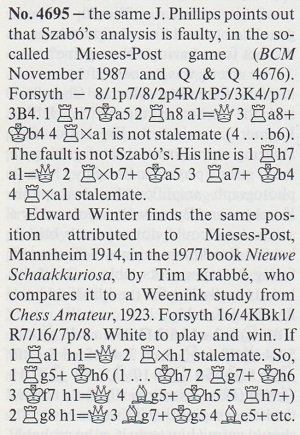

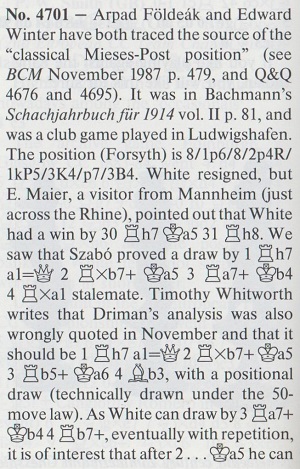

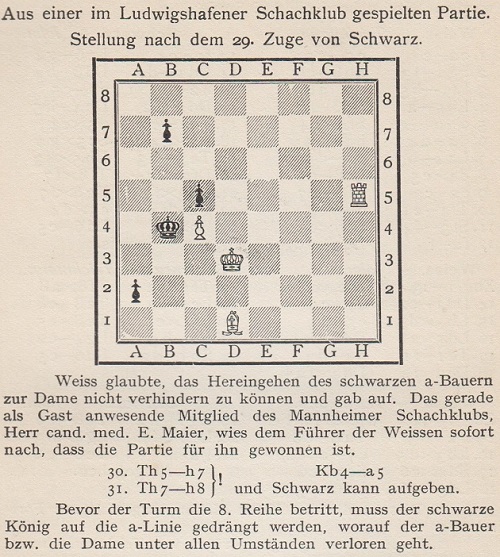

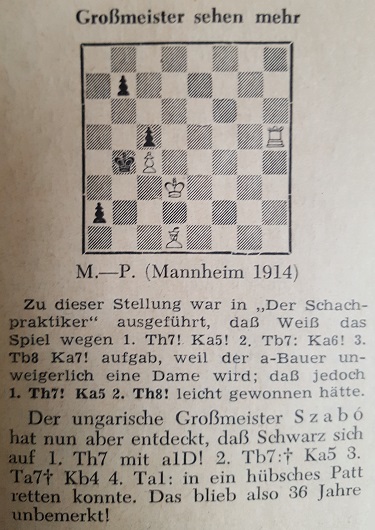

An extract from page 479 of the November 1987 BCM, in an article by Jim Walsh about resignation in a winning position:

There is strikingly similar material, including the attribution ‘Mieses-Post, Mannheim, 1914’ and the vague Szabó/1950 reference, on page 110 of Endgame Tactics by G.C. van Perlo (Alkmaar, 2006).

Walsh’s article gave rise to three items in the magazine’s Quotes & Queries column, conducted by K. Whyld:

January 1988, page 26

March 1988, page 128

April 1988, pages 170-171

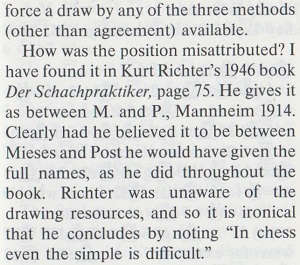

Below is the position referred to in Quotes & Queries item 4701, from page 81 of Schachjahrbuch für 1914. II. Teil by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914):

See too pages 24-25 of Practical Endgame Tips by Edmar Mednis (London, 1997), which stated that after 1 Rh7 the drawing line 1...a1(Q) ‘was recently discovered by the readers of my column in Europe Echecs’ but had also been pointed out by Szabó.

Documentary evidence about Szabó’s exact involvement is sought. Above all, when were Mieses and Post’s names first attached to the ending?

(11378)

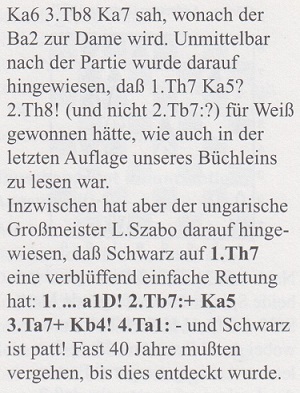

C.N. 11378 had a reference to Kurt Richter’s book Der Schachpraktiker, and below is an excerpt from pages 95-96 of the fifth edition (Hollfeld, 1998):

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) sends the following from page 11 of the 1/1951 Deutsche Schachblätter (edited by Richter and with Szabó as a contributor) in an article entitled ‘Für und wider den Glossator’:

(11389)

This photograph by Erich Auerbach from The Quiet Game by J. Montgomerie (London, 1972) was shown in C.N. 3687, with the question of when it was taken.

From Philip Jurgens (Ottawa, Canada):

‘Vera Menchik and Jacques Mieses played a ten-game match between 21 May and 13 June 1942. He was aged 77, some 41 years older than her. Menchik won by four games to one with five draws. Page 208 of Robert B. Tanner’s book on Menchik (C.N. 10191) described it as “the first ever serious match between a woman and a strong master”.

According to the West London Chess Club website, Vera Menchik joined in 1941 after the National Chess Centre was bombed in the Blitz. Jacques Mieses was also a club member during the Second World War. It is therefore quite likely that they played their match under the auspices of the West London Chess Club and that the photograph was taken during that period.

The above website also states:

“During World War II, very few clubs remained open, but thanks to the determination of the officers, West London Chess Club persevered and invited players from other clubs to play. This brought more strong players to the club, including the likes of Jacques Mieses, Vera Menchik, Sir George Thomas, and briefly, Capablanca [sic].”’

(11981)

For a caricature of Mieses by Leopold Löwy see C.N. 11511.

Addition on 1 January 2025:

From Emanuel Lasker’s column in the New York Evening Post, 3 August 1907, page 7:

‘Mieses, whose forthcoming visit to this country will be awaited with interest by many of his admirers, is one of the most brilliant players of the day. In the following game [Mieses played the Vienna Game against Znosko-Borovsky at Ostend, 1907) he is seen at his best. Like Marshall, if he is only allowed to obtain the kind of position where imagination and courage are required, he is invariably successful. But, like many other players of this kind, he is so dependent for success upon particular positions that either he has to take risks in obtaining them, and lose en route, or is very uncomfortable if the reasonable opportunity does not arise.’

Lasker wrote similarly about Mieses in his Evening Post column of 28 September 1907, page 7.

See too A Mieses-Schottländer Chess Story.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.