Edward Winter

(2003, with additions)

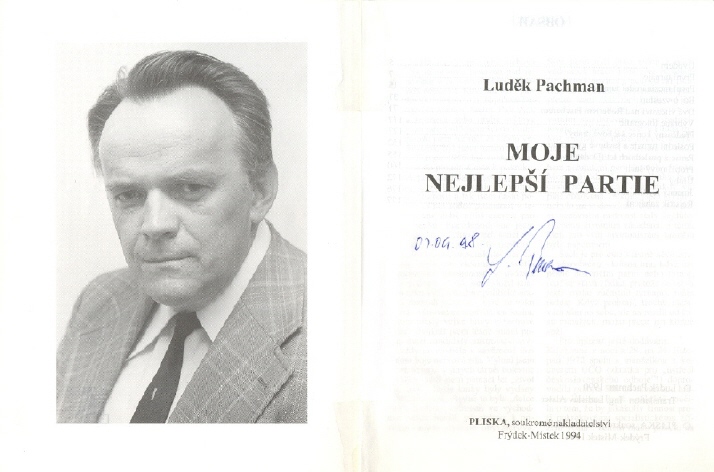

Ludĕk Pachman

The recent death of Ludĕk Pachman reminds us that in the pages of CHESS over 50 years ago he was involved in a fierce political dispute with Fedor Bohatirchuk (1892-1984). Since the two masters’ words (as well as the contributions to the debate by other prominent figures) throw considerable light on the spectrum of political thought at the time, as well as the practicalities of everyday life in the Soviet Union, we quote extensively from the controversy.

It began with a letter on pages 232-233 of the July/August/September 1949 CHESS in which Bohatirchuk, writing from Canada, commented:

‘The Soviet chess masters’ extraordinary successes in recent tournaments, and especially Michael Botvinnik’s brilliant achievement, have attracted the attention of the whole world. Red propaganda attributes all these performances to the enormous development of cultural life in Russia which has been possible only within the Soviet structure of a proletarian State. Red propaganda claims that the USSR has no professional chess players, any more than professional footballers, athletes, etc. On paper, most Soviet chessplayers are engineers, teachers, clerks, etc., etc., for whom chess appears to be only a hobby. For example, Botvinnik is described as an engineering scientist who has done valuable work and even holds a degree “candidate of engineering”. If true, this is an exceptional case. I admit that Botvinnik is a man whose ability amounts to genius but he has had opportunities quite denied to the ordinary master.

When the Soviet government in the late 1920s began to recognize that chess could be a powerful weapon of propaganda it looked around for a young chess master that it could gamble on. Such a man was soon found, in the person of M. Botvinnik. He was given a special trainer who accompanied him in stays at first-class health resorts before each serious tournament. Money matters he could simply forget.

One must admit they chose well. Botvinnik was an ambitious young man and worked hard, soon becoming the leading Soviet master. But he was and of course is a chess professional; all other occupations are only hobbies. Chess has brought him two high Soviet honours, an automobile, and luxury in accommodation and earnings quite incompatible with those of an engineer of his qualifications. His trainer (now perhaps a whole retinue of trainers) works out theoretical novelties for him and tests them in play with other masters; publication of these trial games is forbidden until Botvinnik uses that particular variation.

As soon as the authorities saw that Botvinnik was justifying their plans, they began to finance other chess schemes. Promising young players received special attention. A young chess master without any special education could earn, before the War, 2,000 roubles a month – as much as a University professor. Prominent players, supplementing this by writing, etc., could double this or better. No wonder that nearly all the Soviet masters quit their ordinary jobs to become chess professionals. The radio and the press were always extolling their efforts as of high cultural importance. One had to have great strength of mind, in such circumstances, to remain at one’s job and treat chess as a game.’

Bohatirchuk related that professionals were expected to play in a heavy schedule of matches and tournaments:

‘Thus as soon as a chess master is unfortunate enough to become a prominent one, there are only two choices, either to become a chess professional or to give up serious chess altogether. There is no middle line. Most people take the first choice. But a number of promising chess masters have been forced to give up their beloved hobby; I was one of them.

Until 1935 I managed, by hook or crook, to evade all the welter of minor competitions and play in just one tournament per year, usually the USSR Championship. I timed my annual holiday to coincide with this, so that my profession as a doctor suffered no harm. But after 1935 I was obliged to play in preparatory tournaments, trade union competitions, etc. When all these tournaments happened to be in the town I lived in, I could manage to play; but I firmly refused to go away more than once a year. In 1937, an article was printed in the official organ of the Ukrainian Government, Communist, which hinted plainly that my refusal to play in every tournament could be explained only on the grounds that I was unwilling to contribute to the progress of the young Ukrainian chess generation. Soon after, I was summoned to the Department of Propaganda of the Communist party. The head of the department read me a lecture about the significance which the party and the government attach to chess for the cultural development of the young and told me that my abstentions had produced a very bad impression. “Your victory over Botvinnik in the last tournament, which had such a great meaning for the prestige of the Soviet Union, could also be explained in a way unfavourable to you”, he added, with a hidden menace. My explanation that my career as a radiological doctor, teacher of radiology and scientist leave [sic] me very little time for chess did not impress him at all. He replied that the Soviet Union was at that time more interested in raising the cultural level of the masses and that I must contribute to this progress. When one recalls that 1937 was the year of the beginning of mass persecutions and purges, one can understand that neither the article nor the conversation left me feeling particularly happy. I saw that I had to give up chess; my infrequent appearances at chess tournaments only irritated my adversaries and furnished material for my enemies to use against me.

Early in 1938 I took part in my last tournament, at Kiev, and after that I abandoned the game. My scientific work in the field of cancer research helped me to shun all invitations. I was afraid of prosecution for some months, but fortunately the party’s organizations had much to do just then, and I was soon forgotten.

The declarations of red propagandists about the contribution of chess to the cultural development of the young generation are only a camouflage, under cover of which red propaganda pursues other aims. Soviet leaders are guided by a wise thought of a most reactionary Tsarist minister, Kasso. This minister was the first who permitted students to play chess because, he said, “Chess will divert them from politics”. Since these words were spoken, much water has flowed under the bridges – but the government, as before, is interested in controlling the thoughts of the younger generation. All means are justified by the great aim – complete subjugation of young brains to communistic ideas. Chess is used as an occupation which leaves little free time for unwanted thoughts.

Abroad, chess is used as a method of impressing intellectuals. The enormous diffusion of chess in the USSR is pictured as one indication of the high intellectual level of the masses which is, of course, “only possible in the Soviet state”. Nobody knows what immense sum of money is spent in backing up this dissemination of chess, what an army of chess professionals, organizers, secretaries, journalists, chessplayers, clerks, etc. is paid and fed to promote chess. Chess in the Soviet Union has ceased to be a game but is planned, directed, ordered by Communist super-brains. Many, no doubt, will appreciate this state support for their favourite game, but I, as a lover of chess, prefer to play when I want to, not when I am ordered by officials. To me, chess is only a beloved hobby, and I am not happy to see it become a matter of high policy.’

A response from R.G. Wade (written in Czechoslovakia on 23 September 1949, i.e. shortly after the Trenčianske Teplice tournament) was published on page 32 of the November 1949 CHESS. Some extracts follow:

‘My first reaction was of disgust that chess should have become a medium for a political attack on the country that fosters chess most today. Of course, I realize that any attempt to organize chess for the ordinary working man, who forms only a small percentage of the membership of many chess federations, is sure to be characterized as political whatever the motives of the organizers. (Not in Great Britain, but it has occurred and is a violent cause of dissention in French, Swiss and Danish chess.)

Your correspondent’s letter would have been more appropriately printed in a medical journal, as he is certainly not interested in the “introduction of chess to the masses” but looks on the game as a personal means of recreation. I have noticed in many of the countries that I have visited that if the majority of people are thrown on their own resources for entertainment, they are quite lost as to how to spend their time. … All leaders of sport and culture should feel an obligation to put back into their sport or culture some of the benefits that they have received.

… It is good to have confirmation that the best chessplayers of the Soviet Union (which has more than a million registered players) have material comfort. How often have we read, and I have been told of many more, of cases of poverty and hardship for chessplayers. Though I am not competent to judge how far Soviet efforts are succeeding, I have understood that one of the aims of the Soviet Union is not to obtain a standardized equality for all people but to give equal opportunities to all, and to provide rewards as an incentive for accomplishments, a sentiment that one who is not a Communist could readily agree to.

As for the statement that “the Soviet Government … looked around for a young chessmaster that it could gamble on … M. Botvinnik”, I wrote in the April 1949 New Zealand Chessplayer that “Many well-organized chess countries are not developing young players who are likely to become masters. ... Well-graduated competitions with each player classified have often been a hindrance to a young player who given the opportunity may advance four or five classes in one season … Organizers must be prepared to assess the coming talent. If the teenager shows ideas, is intelligent, … determination, works for success, feed him on the best chess available … It takes faith …” This seems to be what the Soviet Union did with the young Botvinnik. [The omissions in this paragraph are Wade’s.]

Kasso’s statement “Chess will divert them from politics” is too sweeping. People, if they are hungry, would think in terms of their stomach. Evidence of Western visitors to the Soviet Union is that political discussion and activity is encouraged and exists, though naturally discussion is bounded by the general framework of a communist State just as discussion in the USA is bounded by their constitution.

Quite another question is that to which profession Dr Bohatirchuk should give priority. Responsible government should be able to determine which is the more important (and I assume a radiologist to be a person of great importance in any community) and I feel that interested medical organizations should have given the doctor support. If the medical profession is not organized to the extent that it can compete with a sport’s organization for personnel, then Dr Bohatirchuk has a subject to write about.

Finally – chess is one of many means still available that may make a common fellowship between people of all races, creeds, political hues, etc. possible.’

Robert G. Wade

Immediately below Wade’s letter the magazine mentioned a correspondent’s report from Bucharest that the July/August/September CHESS had gone on sale there without Bohatirchuk’s letter.

The December 1949 CHESS (pages 57-58) had a contribution from R.N. Coles:

‘So authoritative and so complete is Mr Wade’s reply to Prof. Bohatirchuk that one feels it should put an end to all further discussion.

There is, however, one more point. Can it be that Mr Wade, whose inclination appears to be leftward, has been led astray by that wicked capitalistic propaganda which would have us believe that no Russian ever speaks the truth? Is that why he disbelieves the Professor? Perhaps Mr Wade has forgotten that the Professor has not been a Russian for some time, but has been virtually a German and is now becoming a Canadian.

It is a curious thing that the staunchest upholders of the Soviet way and purpose always seem to be people who are not domiciled there. Surely it savours a little of ungraciousness, if not even of bigotry, for Mr Wade to insist that he knows more about the matter than the Professor, who very definitely was domiciled in Russia for many years.

It is, of course, quite true that most people, when thrown on their own resources, are at a loss as to how to spend their time. This is obviously dangerous, as they may actually be led into spending that time in thinking for themselves. How much more satisfactory to condition them into exciting their mental faculties over the chessboard, and dangle before them increased material comforts as a reward for success.

The Soviet has an infinite capacity for laughing up its capacious sleeve, and I shouldn’t wonder if there wasn’t just a suspicion of a smile there when Mr Wade’s letter was read.’

Wade responded from London on page 79 of the January 1950 CHESS:

‘Having perused Mr Coles’ letter in the December CHESS, I now realize that my attempted criticism of Dr Bohatirchuk’s letter was not as complete as the laconic postcard from Bucharest. I think it wonderful in these hysterical days that a magazine like CHESS appears in East European countries at all. Please keep politics out of chess and let chess be a friendly means of contact between all countries and CHESS continue to go behind the “iron curtain”.

Also I would like to remind you of the great difficulties that tourney organizers encounter in England in obtaining visas for Szabó, Pachman and other East European masters to come to England. How much tougher Whitehall would be if it thought that these masters came, not to maintain cultural links, but for furthering political aims. Exchanges of visits can only be beneficial and British chessplayers can be glad when Golombek is persistently sought out to play in East European tourneys while Czechoslovakia is waiting for the return visit of a British team.

Despite Mr Coles’ ridicule, I refuse to believe that any State organizes recreation just to prevent political thought. Recreation is a necessary part of the lives of the citizens of any community. Perhaps every Government that makes grants towards any project is partly influenced politically.’

The same issue (pages 78-79) had two other readers’ letters. Peter Cathcart Wason of Old Aberdeen wrote inter alia:

‘Mr Coles does not refute Mr Wade’s argument, and even, it seems to me, betrays some of the bigotry which he imputes to Mr Wade. I do not know whether or not Mr Wade is a Communist, but in his letter he did neither “uphold the Soviet way and purpose” in general (and there is much good, e.g. education, and much deplorable e.g. political purges, in the Soviet system), nor attempt to defend the action of their chess organization.

... Does Mr Coles really believe that even intensive chess playing is less conducive to critical thought than the so-called amusements and leisure activities which the majority of British and American subjects appear to enjoy? The “cultural conditioning” of the individual is not, indeed, controlled in a capitalist State by the Government, but is left to men whose love of power or wealth may occasionally exceed their sense of social justice and moral responsibility …’

The second letter was from Montgomery Major of Illinois:

‘It was with some surprise and much bitter amusement that I read the remarks of Mr R.G. Wade in your November issue of CHESS anent the interesting letter of Dr Bohatirchuk, published previously. It is so apparent that Mr Wade missed the whole point of Dr Bohatirchuk’s comments and so obvious, beyond that, he was prepared to resent any criticism of “Mother Russia” without pausing to evaluate the validity of the criticism, that it leaves one wondering if Mr Wade is a “fellow traveller” as well as a noted traveller.

Apparently Mr Wade belongs, in any case, among the many uncritical spectators at the giant pageant of chess in the USSR who have been so hypnotized by this mass production of chessplayers that they fail to comprehend the mechanisms which create the show. And this thought tempts me to write you, purely in the capacity of an American chessplayer.

That professional chessplayers in the USSR are well fed and housed is not particularly a matter for complacency – as Mr Wade seems to think – so long as that comfortable condition represents a special status that is not shared by other worthy individuals whose sole misfortune (aside from residing in the USSR) is the fact that they are not chessplayers of note. That masters in the past have suffered hardship and poverty was a matter of social injustice, reflecting upon the basic structure of our society; but the creating of a special place of privilege in the USSR is only shifting the social injustice on to other shoulders – not correcting a basic evil. And as a chessplayer I see nothing commendable in a remedy that creates further injustice.

Nor is it a healthy condition for chess when its playing becomes a matter of State policy, and the attendance at a tournament becomes the subject of decision by minor bureaucrats.

But to return to Mr Wade’s letter. He objects “with disgust” to the fact that “chess should have become a medium for a political attack on the country that fosters chess most today”. Clearly Mr Wade does not realize (or refuses to admit) that chess in the USSR has become a matter of politics, and therefore is subject to attack upon political grounds. It was not the nationwide teaching of chess in the USSR which justly earned Dr Bohatirchuk’s reproof, but the prostituting of the game to political expediency.

… So long as chess in the USSR is fostered and nurtured by a Government whose proclaimed tenets include the more-than-pragmatical dogma that a lie is a truth if it serves the purposes of the Soviet Union, that art and science (chess included) are merely vehicles to implement the class struggle and ensure the ultimate world dominance of communism, that honor, morality and probity are merely outmoded and discarded concepts of a decadent bourgeois society – that long must we view the growth of chess in the USSR with suspicion, and temper our respect for the great achievements of Soviet chess with a firm determination that our own chess shall not become a channel of infiltration for communistic ideology throughout the world.

Dr Bohatirchuk’s letter should be applauded as the courageous act of a conscientious well-wisher of chess; and the less said about Mr Wade’s comments the better. We know that proficiency in one art does not necessarily guarantee proficiency and understanding in other lines of endeavour. Some years ago the late Henry Ford in the USA demonstrated conclusively that one of the world’s shrewdest organizers of big business could be a complete fool when he ventured into politics and sociology. Mr Wade’s attainments as a chessplayer are well known.’

Montgomery Major

The next contribution to the discussion was by Ludĕk Pachman, whose letter, written in Prague on 22 December 1949, was published on page 95 of CHESS, February 1950:

‘In No. 6-8 of your journal you published a letter from the former well-known Ukrainian champion, Bohatirchuk. I as well as other Czechoslovak masters met Mr Bohatirchuk in Prague in 1944 and have every reason to doubt his word and the integrity of his character. At the time he told us that he had not emigrated from the Soviet Union. He had ostensibly been ordered to stay behind to look after the wounded in Kiev hospital when the Germans occupied it, and – so he said – as an expert and chess champion he had no special difficulties from the Germans in carrying on his scientific and chess activities. Some months later we found these statements to be false. Mr Bohatirchuk was on the staff of the sadly renowned Quisling, General Vlasov. That means, he became a common traitor of his country at war, such as are punished in Britain by the severest sentences. The hatred of a traitor who staked everything on the Nazis and lost is also evident in the letter published in CHESS, containing a collection of untruths and half-truths.

Mr Bohatirchuk states that all outstanding Soviet chessplayers are professionals. He forgets that a number of top-ranking masters were decorated for outstanding feats. He closes his eyes to the fact that Botvinnik rarely takes part in tournaments because his job as a scientist does not permit it. It is of course true that some of the masters engage themselves in popularizing chess and in organizing it on a mass basis, which requires a number of full-time organizers. It is true that for such organizing work they are well paid, on a level with cultural workers. We might do well to compare this fact with the practice usual in Western countries, where chess champions are less well provided for. One well-known French master has been out of employment for considerable periods. Not because he does not want to work, but because he got the sack every time he wanted to take part in a tournament. The well-known champion Yates died in miserable circumstances, and so did others. The Soviet champions work for the good of all and are rewarded for it; chess champions in the West often have to supplement their earnings by playing for money in cafés.

Mr Bohatirchuk speaks of chess as a “red propaganda weapon”. Could he then explain why Soviet players take so little part in international tournaments, directing their main attention to chess at home? Still more ridiculous is the assertion that chess is supposed to distract people from politics. Chess is an excellent education towards logical and exact thinking, which is the best help in solving political problems. It is a generally known fact also in the West that in the Soviet Union more than in any other country in the world every citizen is educated and led towards active political work. This fact is often used for anti-Soviet propaganda, but as we can see paid agents provocateurs don’t hesitate to state the opposite if it happens to suit them.

Mr Bohatirchuk, however, climaxes all his lies by describing how Soviet chessplayers are being forced to play chess by the State and the Party and tells about being reproached for defeating Botvinnik. That means – according to other statements contained in the same letter – that in the Soviet Union people are forced against their will to lead a comfortable life with the pay of a university professor. And as to the second statement, this is proved absolutely ridiculous if we recall, e.g. the Groningen tournament, when Botvinnik was beaten by Kotov. It does not appear that the outcome of the game was “explained in a way unfavourable to Kotov”. Grandmaster Kotov was shortly after elected a member of the Moscow Soviet.

I am not particularly surprised at the slanderous lies contained in Bohatirchuk’s letter. During the war, he was paid for his treason by the Nazis, today he is the lackey of those who engage in anti-Soviet ravings in the hope of starting a new war. As we say: “Whose bread you eat, his song you sing.” Another hero of the anti-Soviet crusade – Kravtchenko – can at least flatter Westerners by declaring that he “chose freedom”. Bohatirchuk will hardly attempt to declare the same, for he chose the “freedom” of Hitler Nazism. We are, however, surprised that such a letter should appear in the organ of British chess. I convinced myself that the majority of British chess enthusiasts regard chess as a means of furthering understanding and friendship between the nations of the world. The publication of letters like this in CHESS certainly does not support that aim. The old British tradition of “giving every view a hearing” should be tempered with the words of the British Premier, Attlee: “Democracy yes, but not for the fascists!”’

The debate concluded with the following response by Bohatirchuk to Pachman on page 121 of the March 1950 CHESS:

‘I am well aware of the master mind which dictated Mr Pachman’s letter in the February CHESS; I have the experience of 25 years of life in the so-called “paradise of workers”. It was a tragedy of history that I and thousands of others who flew West during the war years were obliged to run away to one desperado to avoid another. God and our conscience remain our only guides.

Mr Pachman writes that I was on the staff of Vlasov. “That means he became a common traitor to his country at war.” Until there is an objective and truly democratic investigation of Vlasov, nobody has the right to call him a traitor, proclaim everybody who opposes their policy “traitor”, “fascist”, “warmonger”, etc.; and not only proclaim but execute or send opponents to concentration camps, alike in war or peace. Nazis used Vlasov’s name to cover many of their own dirty deeds. But one fact of his military life is known: it was in Prague, Mr Pachman, that he defeated German S.S. troops and saved your capital from destruction.

I met Vlasov for the first time in October 1944, when I came to Germany. I found in him a bitter political opponent of the Kremlin clique and in this activity I, with many other civilians – scientists, writers, doctors, public men, workers, peasants and others, supported him, and I am not ashamed of it, on the contrary I am proud of it.

Mr Pachman writes that my opposition to Soviets may be easily explained by good payment from Nazis and “warmongers”. He will not contradict that being a University professor, practising physicist and Ukrainian chess champion, I could lead a comfortable life in the USSR. How well I am now paid by “warmongers” Mr Wood knows, for he can testify that a couple of months ago I could not renew my subscription to CHESS, being financially embarrassed. I never sold my opinions and never will.

I am very sorry that such a talented man and brilliant chessplayer, as Mr Pachman is, has written such a letter. Maybe he is now blinded by the pretentious and pompous declarations of Soviet leaders. I have no doubt that after some time his hopes will vanish into smoke and he will see the ugly reality of the totalitarian state. And if, Mr Pachman, you would follow the example of many honourable Czechs and fly West, please come to me. I shall share with you my modest meals, I know how, I am now living in a country of true democracy.

Mr Pachman asks me to explain: “Why Soviet players take so little part in international tournaments directing their main attention at home”. Soon after the war there were some such voyages not only of chess masters but of other sportsmen. But after some of these (I remember e.g. two prominent Czechoslovakian tennis players) preferred not to return home these voyages were discontinued. Besides that, is it in the interests of the Kremlin to reveal to their citizen the attractiveness of life in capitalistic countries?

Mr Pachman writes that “in the Soviet Union every citizen is educated and led towards active political work” and “chess is used as an excellent education”. With these words he only confirms my assertion that in the Soviet Union, chess has become a matter of high policy.

“Being reproached for defeating Botvinnik” does not mean to be dismissed or not to be elected to Soviet. It is only unpleasant. But if in a totalitarian state you were ever accused of some “crime” against the regime, an unpleasant detail might be reminded. All these reproaches are not forgotten but are filed in some M.V.D. “dossier” of every Soviet citizen.’

(2883)

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) remarks that pages 156-157 of CHESS, April 1980 carried an article by Jurij Semenko entitled ‘Reconciliation After Thirty Years’. It included an English translation of a letter written (in German) by Pachman to Bohatirchuk on 26 January 1979, and some extracts are given below:

‘... when I was barely 17 I was first arrested by the Gestapo and interrogated for several weeks about “incitement to anti-German demonstrations”. You can surely imagine that this was not pleasant. This experience “radicalized” me so that by the spring of 1943 I became active in the underground as a Marxist and a Communist.’

‘My convictions underwent a change soon after our debate. In 1952 (following the major political trials in Czechoslovakia) I resigned from all political offices and decided to devote myself exclusively to chess. Obviously, this was only a half-way, timid decision, since up until 21 August 1968 I still believed that socialism might nevertheless change some day. That 21 August was for me a real “moment of truth”.’

‘... the 16 months of interrogation and torture to which I was subjected. From this imprisonment I was released half-dead, and though three centimetres shorter due to serious injury to my spinal chord, healed in spirit. Immediately after release from prison I returned to the Church and somewhat later (in an interview for Associated Press) publicly explained my reasons for my total break with Marxism. This led to my second imprisonment, where I was sentenced to two years in jail and, soon, to expatriation.’

‘Not long ago, the organ of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia Rudé Právo in its editorial accused me even of murder, claiming that I allegedly “staged, organized and prepared” the self-immolation of Jan Palach. In fact I never knew Jan Palach.’

‘What more can I say about our polemic of the past? He who does nothing and who does not fight for his convictions makes no mistakes. I have confessed my mistakes a hundred times. Also I have since spoken publicly and written differently about the Vlasov army than in the past, having learned its true history from Solzhenitsyn.

However, while reminiscing about those days I find some consolation in the knowledge that I conducted debates of this type only with people who lived in safety and have not harmed a single person who lived under our system. Precisely because of this I am now meeting in exile people of whom I must ask forgiveness for my past remarks. This I would also like to do in our case.

When in your reply to my article in CHESS you made me an offer to come to Canada, where you would help me, I used to consider it a mockery. Only later it became clear to me that your invitation was a serious and sincere expression of your noble character and your true love for a fellow human.’

Photographs of Bohatirchuk in chess literature are rare. A poor-quality one appeared on page 103 of VII vsesoyuznyy shakhmatnyy turnir (Leningrad and Moscow, 1933):

Fedor Bohatirchuk

Mr Negele has supplied the following shot, from page 3 of issue 20 of 64, 1927:

(4308)

See too Pachman’s open letter (Solingen, 13 July 1974) on pages 334-335 of CHESS, August 1974. Also, a ‘rebuttal’ by Paul F. Schmidt of Checkmate in Prague on page 494 of Chess Life & Review, September 1978.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.